| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

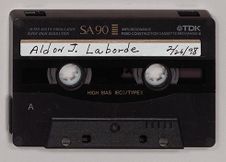

| Aldon J. Laborde | |

| USNA Class of 1938 | |

| February 26, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Aldon J. Laborde:

You want to know how and why I went to the Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes. You were born in 1915. If you will, just a word or two about your background to lead us into.

Aldon J. Laborde:

I was born in a little town of Benton, Louisiana, where my father was a schoolteacher. We were not native. That is in southwest Louisiana near the Texas border. A couple of years later, we moved to the historic home of the Laborde's, where my father was from, up in Marksville in Avoyelles parish in the central part of the state, just on the northern fringes of what I would call the Cajun or the French part of Louisiana. He was a schoolteacher, and became principal of the school there; and later, the school superintendent.

I was raised there and graduated from Marksville High School in 1932, and like everyone else, if you were going to college, you went to LSU. We didn't have access to all these fine, high-priced, elite schools in those days. You either went to LSU or to work in the cotton fields. My family, my mother and father, were both very dedicated to

education and both had been schoolteachers. So, there was little question that we should try and get an advanced education.

We were a sizable family; we were five. I had a brother ahead of me and a brother behind me. The one behind me was pushing me just a year later. My older brother was still at LSU when I went at the age of sixteen. While there, I was involved in the ROTC thing. The head of the ROTC was a colonel, later General Middleton. You might have heard of him during World War II. He was rather prominent in the European activities; head of one of the armies, the 29th.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think I probably have some photographs of him in one of our collections of another general.

Aldon J. Laborde:

General Troy Middleton. Anyway, I met him. After talking things over, he said, “Why don't you try to go to West Point?” He understood, too, that my father was a school teacher who was going to be pretty strapped when my third brother started college before my oldest brother, who was going to law school, was out. There would be three of us over there even though it only cost a couple of hundred dollars a year to go to school then. That was part of the motivation.

I thought the military life, what little I knew about it and imagined--the freshmen at LSU in ROTC didn't give me a very broad background on military life--seemed to have some appeal; the order of it, the regimentation of it. I took to it. So, he explained to me about it, and in due course, my father knew one of our senators and through him I got an appointment and talked to him.

He advised me that he didn't have anything for West Point at that time, but he said, “I think I'll have an opening at the Naval Academy next year. That's just as good.” I said, “Well, okay. I'll try that.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you spent much time in New Orleans? New Orleans, at that time, was quite a center for naval activities, was it not?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Yes, but New Orleans was a long ways from home.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right. That is why I asked if you spent much time there.

Aldon J. Laborde:

It was a trip in a Model-T Ford. It took about eight or nine hours.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't know whether you had been exposed to the naval presence.

Aldon J. Laborde:

We would follow the river. I had been there a couple of times, maybe, with my father. You know, it was a great event to get to go to New Orleans and spend the night in a hotel. But, I was not exposed to anything naval around New Orleans.

I wound up getting an alternate appointment for that year, which allowed me to sit through the examinations I was studying pre-med in the meantime. I didn't pass the examination that year, the principal got in anyway, so I didn't make it. But by then, I was hell-bent to try.

So, I stayed out of LSU the following year and did some studying. There was kind of a coach class that a couple of high school teachers, sort of a high school refresher course, ran. I enrolled in that for a couple of months. Anyway, when I took the exams again the next year, he left me on the list and I had moved up a notch. I had the principal appointment as they called it then. I passed the exams with flying colors, kind of 4.0ed all of them, because I had taken that little intensive course (using the old exams as material) from the two old ladies, schoolteachers. It was pretty easy. I had gone in

naively the first time thinking, Gee, I knew all this high school stuff pretty well, so I didn't have to worry about it!

Donald R. Lennon:

You had another year to mature.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Had another year to think about it. By then, I was almost obsessed with the idea of making it. So shortening the story, I wound up going in in 1934 to the Academy and graduated in 1938, a rather routine four years.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you react to the Plebe Year, the upperclassmen . . . don't want to call it harassment, but the normal . . . .

Aldon J. Laborde:

I know exactly what you mean. Number one, it was not as bad as it was expected to be. Number two, I think my frame of mind was just right for it because I had tried so hard to get there. With having achieved that, I wouldn't dare find much wrong, unlike a few of my classmates who had kind of been pushed there because of parents in the service, and tradition, and all that “You are going to the academy.” They had a much harder time of it: “Why the hell did they make me come to this place?” I didn't have that. I didn't find it unreasonable or bad. The system always had some safeguards in that regard. Each of us was assigned, I don't remember exactly how, but each of us wound up with what we called a first classman. He was sort of your refuge. All the formalities were dispensed with in the relationship with him. Maybe they still do it. They called that “spooning.” When an upperclassman “spooned” on you, that meant you shook hands. He was your friend then, your refuge. I was fortunate enough to have a good one. That was very helpful, but the overall system didn't bother me. The food was good. The routine was no more severe.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, having study at LSU, the instruction was quite different at the Academy.

Aldon J. Laborde:

LSU has a large lecture system, especially for freshman. You'd go into a lecture with a couple hundred other freshmen and sit down and take notes and take an exam. At the Naval Academy, we had the small class system. The professors at the school were mostly naval officers who didn't know a lot, but everything was organized, managed, and supervised by good professionals who also prepared all the lessons. You'd walk in class and draw a slip off the professor's desk and go to the board and write, based upon the assignment. There was not all that much instruction in the class because these Navy guys were more mechanical facilitators then they were professors. We occasionally had some lectures by department heads and things that were very good. I think this system worked fine. Maybe I am not doing full justice to these instructors. There were a lot of civilian instructors who were professional and good. The naval officers were not bad; this just wasn't their main profession. They were there a couple of years for shore duty. I think this system was effective and it tied in with the overall disciplinary thing. That's, I guess, the part I liked about it, your whole life was organized around the Service and the military, and the instruction and the drills were just a part of that. Getting up in the morning, going to bed, and going to meals were all just a part of a routine that actually was pretty good. You didn't have too many decisions to make. They were all made for you. If you kept your nose clean and minded your business, it wasn't bad. Not much social life. I wasn't inclined that way and wasn't so inclined before I went there either.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of outside, extracurricular activities were you involved in?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I was no great athlete, but I tried sports. I tried football and I was on the junior varsity, but didn't make the squad. I played lacrosse. I made the freshman team, and as a sophomore, I was on the squad. I got involved with my class. They elected me as editor

of the annual, the so-called Lucky Bag. We started working on that the sophomore year. I guess you are familiar with the nomenclature; Plebe, Youngster, Second Class . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh yes.

Aldon J. Laborde:

The youngster year you are elected and started working on what would ultimately be the class annual, which was published at graduation. That was pretty full time, in the sense that you had to use your very limited amount of spare time for that and it was at the expense of athletics and some other things. I was pleased to be selected and enjoyed it. A lot of other classmates were involved.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you edit the '38 Lucky Bag?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is a very handsome volume. We have it on the shelf.

Aldon J. Laborde:

So that was probably my principal extracurricular activity the last couple of years. It may or may not have had some impact on my athletic career, which was nothing to shout home about. Other than that, we tried to get out and do some exercise and play a little tennis.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do much sailing?

Aldon J. Laborde:

No. Sailing was too time consuming to compete with the Lucky Bag responsibility. I had no background. I was born and raised in an inland environment. I had the same amount of sailing that everybody else had. Some of it was part of our assigned extracurricular stuff. For pleasure, you could sign out a boat on a Sunday afternoon and go sailing. I probably did that half a dozen times. I was not a sailor in the sense that so many of my classmates were.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular individuals that you came in contact with, other students or faculty, at the Academy? I know I worked a lot with the Class of 1941 and they had Uncle Beanie, who was very dear to them. Was there anybody comparable to that in your class?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I guess the most memorable company officer around was a fellow named Wessel. He was a German. We had a nickname for him. He is the most memorable one.

He was tough. He walked around with a riding crop and would hit you on the belly. “Belly up! Belly up! Chin in!” He had kind of a little German pipe cap. I don't know where he had gotten it. That was before World War II and he kind of envisioned himself a German Prussian soldier of some kind. A real disciplinarian, took great delight in that, so he was memorable.

There was a Commander Delaney who was the Executive Officer of the Academy. He was kind of the counterpart to Wessel. He was very kind and helpful, and I think, he was the faculty representative for the Lucky Bag so that put me in contact with him. Those would be the two most memorable ones.

Another one you can't escape completely is that President Roosevelt gave us our diplomas at graduation. Obviously, I remember that occasion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, when you graduated in 1938, you were assigned to what?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I was assigned to the battleship TENNESSEE. In those days, we served a two-year probationary commission and then you received a permanent commission after two years if they wanted you and you wanted them, I guess. We were required to have 20/20 vision all through the Academy and then for a commission. However, when I graduated, my eyes had deteriorated and I couldn't quite pass the physical for the commission. So, I got

the probationary commission conditioned upon my eyes getting back all right after two years for a permanent commission. So, I had that somewhat cloud over me.

But anyway, I went on to the TENNESSEE, a battleship on the West Coast. The battle fleet was assigned to the Pacific in those days. I was doing all right. I was the division officer. I was in the fire control division. I was in charge of the plotting room, which is down in the bowels of the ship; it kind of controlled the firing. We didn't have computers in those days. They were those mechanical computers, the computers that preceeded the electronic ones. That was interesting and fun. I think I was doing all right. I was probably the first one in my class on that ship to qualify for top watch, which meant that you stood a watch as officer of the deck and were in charge of the whole ship for a four-hour watch. First of all, you were a junior officer of the deck for awhile and then you qualified top watch and they put that in your record.

I was doing fine, but when the two years was up in 1940, I took the physical and still my eyes were not up to the 20/20 requirements. They did not allow you to wear glasses in those days. It was ironic that by then, 1940, if you think about it, the North Atlantic Patrol was on, we were getting ready for war, they were calling up Reserves, but the Bureau of Medicine was still kind of on the old peacetime page and said, “Sorry.” My commanding officer wrote some very nice letters, I thought, trying to turn that around and was not able to. I was offered a commission in the supply corps and I didn't want that. I resigned and came on out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you remember a classmate of yours, Donald Snyder? Same thing happened to him, didn't it?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Exactly. He was on the same ship. We called him “Donald Duck.”

Donald R. Lennon:

I interviewed him back some years ago. He was a DE skipper.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Well, that is where I wound up too. We had pretty parallel careers. He worked with me on the Lucky Bag. He was one of my sub-editors of the Lucky Bag. I know Don well. I have lost touch with him.

Donald R. Lennon:

I believe he lives in New Hampshire.

Aldon J. Laborde:

We left the TENNESSEE at the same time, after having him there for two years together. I remember him well.

I came home and started a little business. Fortuitously, a guy staked me with ten thousand dollars to open up a bonded warehouse business over in Lafayette. Had that going for about a year, when Pearl Harbor was approaching. I remember a guy in the Reserves came to visit me, I guess they were chasing down guys like me, and suggested that I get back into the Reserves. He said I probably would get called to active duty as soon as the war started, so I did that. I was commissioned in 1941.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you not voluntarily joined, they would still have come looking for you.

Aldon J. Laborde:

I suppose so or I would have been drafted in the Army. That didn't appeal to me too much. So, to that extent it had that leverage on me to get me to volunteer back into the Naval Reserves. Obviously, I figured that was appropriate as well.

Then right after Pearl Harbor, I got orders to go to the Sub Chaser Training Center in Miami. That was in early '42; it didn't come the day after Pearl Harbor. You know, I was standing by the next day waiting, but you know how these things went. I got to Miami and they were just organizing the Sub Chaser Training Center. The war in the Atlantic was going pretty badly from day one. The submarines were lying off the coast and just knocking these ships off. Our ships were cruising along, up and down the coast

in the early days, with their lights on and everything. The Germans were knocking them off pretty badly. They were in something of a panic. The “real” Navy guys and my “bluewater” classmates were out in the Pacific, and they were not about to get involved in this kind of stuff. That was beneath their dignity. They wanted to be in the real shooting war with the Japanese and that was what they were trained for and what have you. I was part of a pretty motley group of people that they organized mostly from civilian life. A few like Don Snyder and me perhaps and others that had some little excuse for a naval background, they immediately grabbed us and put us in charge of all kinds of things that we didn't know much about.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looked like that for sub chaser duty that they turned to a lot of yachtsmen.

Aldon J. Laborde:

They sure did. They all did a good job and I cover that in great detail in my book. They were just building the school. It was on a freight dock over there in Miami, Pier 2. Commander McDaniel was setting it up. He was a blood and guts kind of a guy, who had been out in the Atlantic on a destroyer. He was a good man, a tough old guy.

After a few weeks of that school, I was ordered to take command of a PC boat. Are you familiar with PC, patrol craft, and 173-foot steel hull? I came back to New Orleans and picked one up that had been built up in Jeffersonville, Indiana, in a boatyard up there and went off to Key West with it. It was pretty empty, no ammunition, no nothing. A green crew, none of whom had ever been to sea before to speak of. I had one quartermaster who had been in the Merchant Marine, who was pretty helpful. It all comes together pretty fast when you are in there and it is serious business and it is war and you are there twenty-four hours a day. I had a fair notion of what we were supposed to be trying to do. I didn't know anything about sonar and anti-submarine warfare, but in

Key West, we went through a training period there with attack teachers on the shore. We went out with a tame submarine, one of our own, for a few days and then off we went.

We picked up a convoy somewhere out of Key West and headed up the coast to New York with it, back down to Norfolk, and down to Trinidad. Just up and down the Atlantic. Things got pretty good after awhile. It was a motley crew of escort vessels; big yachts, Coast Guard ships, and usually one Navy ship--a four-stack destroyer--whichwas the escort commander as a rule. That went on for probably eight or nine months.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you make any contact with subs during that period?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Not really good solid ones. Every now and then, we would make attacks and probably a lot of them were the sunken wrecks that your people are talking about. We would get some oil up and some debris and everybody was happy and all. We never did kill a sub in my opinion. We didn't know much about it. Our gear wasn't very good. The advantage was always the submarine's in my opinion. I think just the fact that we had the escort vessels just pinging away with sonar was a deterrent. Submarines kind of stayed at bay a little.

Donald R. Lennon:

Made them more cautious.

Aldon J. Laborde:

We didn't have any serious attacks to speak of while we had them in convoy. I think they gave us credit for being a lot better than what we were. After some time, somebody decided that they needed skippers for DE's, and somebody decided I was qualified for that. I went back to Miami and then went to Orange, Texas, to pick up a DE, number 147, the BLAIR.

My crew came in from Norfolk from the training center there. They were mostly reserves, but they were good guys. They learned fast. Some of them have been in the

reserves, sea scouts, and one thing and another. There were no regular Navy guys in the crowd. I was still reserve, but I considered myself regular Navy more or less. I think they looked upon me that way. We outfitted the thing and headed out. We had a shakedown in Bermuda, four or five weeks. Then off we went to the first assignment and then it was pretty routine, back and forth across the Atlantic, from New York _______ Norfolk to usually we would drop off at Londonderry, and picked up some empties coming back. Occasionally, we went into Liverpool. Later on, after we invaded, we went into the channel to Plymouth and places like that, Southampton. We made a trip or two to Gibraltar.

I had exercise for a couple of months with a hunter-killer group, with the baby carrier, CARDE. These baby carriers with half a dozen escorts. We would go out in the middle of the Atlantic which was out of reach of the air cover and wear the wolfpacks were having a lot of fun out there for awhile. They would wait out there and jump these convoys in this wolfpack operation and we couldn't cover them from the air: from Iceland, and the Azores, and Bermuda, and Argentia and those places. Just draw those circles at five or six hundred miles and then in between that would be a corridor. We moved out into there. One or two of them ahead of us were extremely successful with that. They caught them by surprise and just knocked off eight or ten of them in the first sorties. Our group again didn't have much excitement. In fact, we did that a couple times, it was mostly a battle with the weather, terrible winter weather. Trying to fly those planes off those little old carriers. They put one up in the evening before sunset. He was stripped down with just a lot of fuel and radar. He would fly around, hopefully fly all night and pick him up next morning.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this the winter of 1942-43?

Aldon J. Laborde:

1943, I would say. Dating from l943 into l944.

Then, the idea was that if he got a contact, then we escort vessels would go chase it down and try to do something about it. We were not successfully in finding any. We wound up losing a lot of airplanes, though. A lot of times that guy would have trouble. You would have to land him at night, and that was serious. You had to wait till next morning and by then the weather had deteriorated. The old carrier was going up and down something awful. They had about twenty-three planes and PDFs and some torpedo bombers and some fighters, some F4Fs, I think they were. They would fly around in the daytime if we had any reason to have them out.

But, the over all scheme of success, everybody gained. My part of it was not very exciting other than living through it and fighting the weather and all that. Same with our convoy, I guess I was on eighteen, twenty months on this thing in the North Atlantic, and we never really had a serious submarine attack. We had a lot of warnings and every now and then somebody would be dropping a bunch of depth charges and stuff like that. But never lost a ship that I recall.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the weather was something else.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Weather was something else on a little ship like that at three hundred and something feet. It sounds like a big ship, but not in those thirty and forty foot waves. That was being done in early 1944. My exec was, I had reported him qualified. That was part of the scheme, to try to get more people into this thing. So, they transferred me back. I went over to Bay City in Michigan, where they were building some of these VDs. The Atlantic thing was toning down then. The invasion had taken place. The submarine thing

was pretty well in hand. We had total control the air, although it was back and forth. I am sure you have had a lot about the development one way or another, the SNORKEL and the acoustic torpedoes. It was a back and forth thing with a lot of technological developments involved.

Back to the APD, it was being converted. In hindsight, I would say we were getting ready for the invasion of Japan with those things. It was towed down to New Orleans again, down the Mississippi from Bay City, Michigan in the spring of 1944. I got my crew here and went on down to Guantanamo Bay for shakedown this time. We were talking about bringing APB and got it down at shakedown at Guantanamo. Then headed back to Norfolk to pick up my underwater demolition unit, which was our assignment. That was frogmen, and some of this I had to piece together later.

We were assigned to a group that was going to go in on the invasion of the southern island there, that is Kyushu, with a couple of Marine battalions. I was to help clear the beaches and blow up the coral reefs and stuff for the landing work in couple of weeks, ahead of that working at night mostly. Though, we were training for that with these fellows, these UBP boys. They had these little personnel boats, I guess there was seventy-five of those on board and the rest of us were there to just to take care of them.

We went through the Panama Canal and on around to San Diego. There we picked up all our plastic explosive of some kind. It came in little knapsacks. We had the whole ship filled with that damn stuff. Of course, I was very unhappy. I didn't know much about it. We had in the living compartments about two feet deep, walking on it and every thing else. I went ashore and talked to the commanding officer of the base there. He said, “Get out of here! Those are your orders. Get out of here!” I said, “I have been

around the Navy a long time, I never heard of having all this stuff anywhere but in a secure magazine.” He said, “This stuff won't blow up. Don't worry about it.” So, off we went. We were going by way on Eniwetok to report to Buckner Bay that is in Okinawa to command at a mine fort. We would get our orders from there. While we were on our way out, we learned about the atomic bomb. There was no heartbleeding about that I can assure you. That is a more recent phenomenon. We were delighted.

We learned later that the expected losses in the kind of work we were in, we didn't know in excess of fifty percent. They expected to sacrifice most of those ships and a lot of those guys. We would in our practice things as we were suppose to do it, we would come in and drop them off as close as we could to the beach in the early night and then try to pick them up next morning. While they were doing there work of planning this stuff and what have you, we never got to do any other than for training purposes. So, around the fifteenth of August, I think it was, the surrender was not signed, but it was announced and the surrender was a week or two later as I recall.

So, I thought sure I would be coming home with those guys, but they got transferred back and I was in assign with my ship as a division commander for some minesweepers, these little YMSs about six of them. So, up we went into the Inland Sea of Japan, among all the islands there, around Kure and Hiroshima and all those places. In Nagoya Bay, we swept that pretty thoroughly. They came through behind that with the invasion of Japan; somewhat like the invasion had been planned, but it was just occupation since there was no resistance it was just occupation. We went through the exercise about like it would have been. Then my group was in Nagoya Bay finally. We cleaned that all the way up to Nagoya.

Then we went all the way north to the Straits of Hokkaido, between Honshu and Hokkaido, and swept up there awhile. By then, it was Christmas time, more or less, of 1945. This was from August to December 1945. It seemed like years because by then we kept getting these ALNAV dispatches releasing everybody; all the reserves, anybody with enough points to go. So, I would up with nobody. I had to wait for a relief because I was a skipper. I had plenty of points and everything I needed to get out, but as skipper, I had to wait for a release. We keep letting them go and I was down to a bunch ensign, seamen, and firemen trying to run that ship. I had to stay on the bridge the whole time. I had a copy of regular Navy chiefs down in the engine room and that was about it. We were not alone. In hindsight, I am glad they did that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Very typical of what was going on.

Aldon J. Laborde:

They had to disband this monster that had been created during the war. Everyone wanted to come home. I didn't really sea the idea of getting blown up by a mine after the war was all over, having lived all the way through it. I didn't know anything about mine warfare and minesweeping.

Donald R. Lennon:

A question occurred to me. Most of these or a lot of these minesweepers were wooden-hull vessels. We have records of some of the companies that made and constructed them. Did they utilize the wooden-hull for minesweepers because they were less likely to trigger the mine than a metal-hull vessel?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Yes. That is right. Many of these mines were magnetic. The mine makers had gotten way ahead of the minesweepers. In my judgement, these minesweepers were built out of wood and even their machinery was brass, not steel. They used three things. Number one was the regular mechanical sweeps, kites, which you trailed out and they

engaged and clipped the anchor line of a moored mine. The mines were moored under the surface with a weight on the bottom at fifteen, twenty feet below the surface. The ones with the prongs that you see in the movies that if something touched it it blew up. Those were the moored mines designed to catch deep draft vessels as they went by. They would clip those with those kites and then they would bob to the surface. Then we would blow them up with a machine gun fire.

However, they had developed other kinds of mines. They had the acoustic mines, which were set off by the propeller noise. They had magnetic mines. They also had combination of those. They had some that would not go off on the first contact; they would just click a notch. Some of them were set maybe to go off after ten ships had passed, which made it very difficult to sweep them.

Some of them needed not only the acoustic noise, but also a magnetic impulse, combination acoustic-magnetic. You could set them off with just a noisemaker, and it had to be a ship or some magnetic body. On the bows of these little minesweepers, there was an acoustic hammer, a noisemaker, a banging thing, like a power driver to simulate the frequency of a propeller noise. That went out of ahead of them. Behind them, they towed a magnetic cable that simulated the magnetic property of a ship, but was imposed on it by electric current.

They really used three different methods: the mechanical one, the acoustic one, and the magnetic one, keeping in mind that a lot of these mines had been planted by all these wild aviators. If you are going into the Air Force, you can imagine if you were one of these guys going into drop mines in Japanese harbors while the war was still on you weren't too worried about exactly where you dropped it. The idea was to get rid of them

and come home. So, you didn't know where the damn things where. They hadn't worried too much about how to sweep them up as they were developing these mines. It was quite a chore.

After we would do all these things, I am referring now mostly to Nagoya Bay because that is where I spent most of my career as brief as it was, they brought in a liberty ship filled with the equivalent of Ping-Pong balls and remote controls. They had a padded wheelhouse and just a quartermaster and a signalman up there, no manning on this ship at all. They would run back and forth, trying to blow themselves up.

Donald R. Lennon:

That sounds like delightful.

Aldon J. Laborde:

After we were all done sweeping. It was a duty very much in demand because once you did four weeks of that you got a ticket home. To my knowledge, none of them ever got blown up. The flotation of these Ping-Pong balls was in case you would knock a hole in the ship and it still wouldn't sink. It would still retain its buoyancy.

Donald R. Lennon:

In a Styrofoam...

Aldon J. Laborde:

Called those guinea pigs. They had about four of those guinea pigs out there. I guess today they use Styrofoam, but these were something like little plastic balls. That was after we had done everything we could have because you still couldn't be sure that the next guy coming along still wouldn't find one of those mines. I imagine they are still sweeping up ashore down there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you ever detonate any too close for comfort?

Aldon J. Laborde:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

How close could you detonate them without?

Aldon J. Laborde:

About a hundred yards or so. Floating on the surface, it just made a big blast. We would shot them with forty-millimeter automatic machine guns on the ship. They were pretty big guns. They would knock a pretty big hole into them and blow them up.

Finally, about Christmas time in 1945, I picked up on the dispatch that a guy had been ordered to relieve me in Okinawa. I had been watching them pretty carefully. Several months before, I had orders to come home upon being relieved. SO, when I picked this up, I went over to the division commander. We got back in Buckner Bay some kind of way. He was in the BIB, which was a Coast Guard cutter. He was a Navy captain and my immediate task force commander. I told him. He had also been on the TENNESSEE with me before and I knew him, Captain O'Connor.

I explained the situation to him and I showed him the dispatch that this guy was coming out. I said, “Why don't you let me go?” He said, “Okay.” They sent a message to wherever they had to send it, saying the ship was temporarily out of commission because lack of a qualified commander. He cut my orders to go home. So, I went ashore at Buckner Bay and lived in a tent there three or four days, shopping around trying to get a ride home.

I finally found a transport going home, the AJAX. It was a destroyer tender actually, and they were using it as a transport. I talked to the skipper and he asked, “Can you stand a watch?” I said, “Yes sir.” He said, “You're on.” He and I stood watch and watch, which means four on and four off all the way home. We were the only two guys, so that gave me a ride home. I got turned loose in San Diego and came on home.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you remained in the reserves, did you not?

Aldon J. Laborde:

For a few years. I am not sure why. I remember the irony of it. I got letter saying that I was a commander by then in the reserves. I got a letter saying that if I didn't get some sea duty or training duty that they would have to terminate me. I applied for a cruise and the answer came back that they didn't have any money for training of people of commander rank. So, they asked me to resign and so, I resigned. They wanted to know somewhere on the paper why you were resigning. I said just refer to your letter of so-and-so as my reason of resigning. And that was the end of my naval career.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you went in after Pearl Harbor, the end of 1942, what happened to your bonded warehouse business that you had opened?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I had put up a thousand dollars and he had put up ten thousand dollars, so he just gave me my thousand dollars back. He had one of his boys around and took it over.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he continued to run it.

Aldon J. Laborde:

He wished me well and I was delighted.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, when you came back, how long was it before you got involved in offshore oilrigs?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I went back to hometown in Marksville. I had an older brother who was crippled with polio and I had two other brothers. Three of us were in the service, and he kind of took that hard. I think he took it on himself to try to see that we helped out as best we could to get situated.

He got me a job with a seismic crew familiar with that in the oil fields. They go around shooting dynamite and getting the reflections from the Earth and plot the substructures in the Earth. It was a very menial job. I was a helper on what they call a jug line, dragging cables and digging holes for the so-called jugs, geophone. I played

with that for a few months and actually got to be head of that shooting party. I soon realized that wouldn't the real oil business and something else came along. I came down here and got a job with Sid Richardson, an independent operator from Fort Worth, Texas. He was a very successful one, who was just moving into the marsh play here where dredge canals and moved rigs around.

__________________ was his excuse for hiring me. I was what they call a roustabout pusher on this rig. I was kind of in charge of the maintenance and stuff like that. The working hands, the others, and the roughnecks are called roustabouts. They are the guys who load and unload, ship paint, and do other things. I was in charge of those guys.

Donald R. Lennon:

But your background at the Academy and the Navy certainly gave you engineering experience that was...

Aldon J. Laborde:

Well, it did. My breakthrough, if you will, was especially the steam rig. If there was anything that I knew a little something about, it was steam boilers. I kind of re-rigged all of that. Those were very crude boilers in the oilfields in those days. They would throw a hose in a crawfish pond for boiler feed water and you would up with a bunch of mud in the bottom of them. They would blow those down every watch and mud would come out.

So, I enclosed the system and was slowly able to convince my tool pusher, the head guy on the rig, that I knew what I was talking about. So, we enclosed the system and captured the exhaust. We would exhaust everything into the air in those days. We put a vacuum exhaust on the boilers, which increased the power on most of the engines and pumps. We saved the water and recycled it and treated carefully the makeup water.

It became obvious to them pretty soon that this was a good way to go. So, I made that little contribution.

I had a little laboratory with some test tubes and things to test the water. These were very crude things used to test salinity and pH. Slowly, I got into the drilling mud, which is the stuff you circulate a drilling hole with. I went off for a couple of weeks and took a course in that. When I came back, I was in charge of that. The roughnecks started calling me “Doc” because I had my little laboratory. Folks still call me “Doc.” That was my oilfield name.

That went on for a couple of years. I was learning a good bit. I was a nuisance, I think, but I was asking a lot of questions. I had background to try to understand what was going on in the drilling thing. I am sure I bothered them a good bit with all these questions. This was in 1946.

In 1948, I heard about a discovery offshore that a company, Ker-Magee, had made off Morgan City, Louisiana. On a hunch, I went over there and applied for a job. In this offshore operation, they had just reached the point. They had been added about a year or so and made a discovery that hit the papers. They had been added long enough to realize that the marine side of this thing was not to be ignored. They had kind of ignored it up till then. They would try to reproduce some land out there, and put a land rig on it and go about it that way. The marine part was kind of a nuisance to them. They were very glad to see me come. They turned over the marine operations to me and called me the Marine Superintendent.

Moving barges back and forth and the crew books. In those days, we were using permanent platforms to drill off of. There were movable support vessels moored near

them to reduce the size of the platform. That was kind of the first step in its evolution. So, I had to tend to anchoring those things and moving them about. I had my hands full there. In four years, I got to learn a good bit about what was going on and developed some ideas. Everybody knew how great it would be if you could get a movable rig that could go and drill a well. If it was no good as it usually was, you could just pick up and go to the next one instead of having to tear down a platform, go to the next place, drive pylons, bring derrick barges out, rig up the rig, and then move the tender along side. No one was quite willing to try.

I had an idea; thought it could make something that would work. It was worth a try. I had nothing to lose; I had no money, no reputation, no nothing. It was about 1952 by then. I tried to talk Gene Magee, who was head of company, ____ Magee Company, into building such a thing. He wouldn't do it. So, I told him, “Well, I think I will design and see if I can put it together.” So, I did. I hit the road with my briefcase and a few sketches. I tried first with the major oil companies who were operating in the area. Their mentality just wasn't right for that in a big corporate organization. Executives working their way up don't stick their necks out on new technology. After about six months of mostly turndowns, I finally went up the country. Through a chain of circumstances, I became interested in it. ___________________ I wound in El Dorado, Arkansas with the Murphy Company. I guess what I told them sounded reasonable to them because they didn't know too much about the risks and the other side of it. They agreed to put up half a million dollars of the million of seed money I was looking, but with them in hand, we were able to raise the other half a million. A group of investors in St. Louis put it up. With that and some credit from supply stores in the shipyard, I was able to build the first

one and we organized this company, Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company. We called it ODEC. We built the rig here, MR. CHARLIE; Charlie being Charles Murphy's father. Everybody called him Mr. Charlie. Charles Murphy, Jr. was running the company, Murphy Oil Corporation. So, it came out in 1953.

Then, I went to work for Shell in East Bay, down near the delta. It was designed to work in about forty feet of water. There is a barge on that, a buoy's barge on that on the bottom. Then it has these big legs to stabilize it as it goes up and down. You put stuff out to float it and than you sink it. It has a slot in the hull on this end that you drill through. Down in the lower hull. It worked fine. I say fine relatively so. There are always a lot of problems with start-ups. We kept improving on it.

The best thing that happened is the first w____ that went on it made a tremendous discovery. In spite of the little problems with it, I went into the division manager here of Shell. I was ready to take a tongue-lashing for the things that I knew had happened that wasn't supposed to be just right. He was a Dutchman, “That's a great rig you got. You need to build three or four of those. We could use them.” That kind of kicked us off.

Some years later ODECO was the biggest offshore drilling contractor in the world. We went on to build this forty-feet. We built larger versions of what I call sit-on-bottom rigs, up to about seventy-five, eighty feet of water. But by then, they were getting bigger and bulkier and taller and unwield. It became obvious that something else was necessary. You couldn't expand that technology very much further economically. Meantime, others were working on things too. Others developed the jack up thing, which was a floating hull with legs. You would lower the legs to the bottom and than jack the hull up on them. That worked pretty well till about two, three hundred feet. In each case,

we thought we were as deep as anybody ever want to go looking for oil. Before you knew it, they had reached that edge and wanted to go still further. Larger through my efforts and some of the others in our company, we designed the first floating, semi-submersible rig which was this one, the ocean driller. You notice it is a little different shape than some of the ones you have noticed.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Aldon J. Laborde:

The idea was to get as large a footprint and drill near the center of buoyancy of that thing so that the movement would not be too much vertical while you were drilling. We didn't know how it would work. It has worked fine. It was a brute to tow though because there was submerged tubes under that configuration. Towing it, you had to move a lot of water. It became obvious that making those hulls parallel would work after trying this for awhile. We built two like this, and then got a more parallel hull arrangement so it would tow better. Later, with propulsion in them so they could move around without tugs. For you knew it, we had about forty some odd of these things around the world. We kind of the biggest guy in the business.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Aldon J. Laborde:

We went public to raise money to keep up these pretty capital-intensive things. I guess the company had a market capital of a billion dollars, which to me was big numbers. Then I retired. I was sixty-one years old. I thought I had done about all I needed to do. There were some good guys coming along behind me. I was kind of committed to them and trapped myself. Later on the company, the Murphy people never did really care too much about the drilling/contracting business. They were in it of necessity as their way to get into the offshore play. Once they passed that they decided to

get out of the drilling business. They were more interested in the producing and refining and marketing and go ahead and hire contractors to do that part of the work for them. Here about three years ago, they just sold all their rigs. They still own half of ODECO right on through. By then, ODECO had become a very substantial producer of oil and gas in its own right. They wanted that part, so they merged the company, keep that, and sold the rigs. Just as an aside, they sold the rigs to an outfit headed by KESH, the Lowe's Corporation, CBS people, what have you. They got three hundred and fifty million dollars for the rigs. Today, the company that bought the rigs has a market capital of about three billion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Good gracious! Going back to your days on the TENNESSEE, you were basically on the TENNESSEE for two years.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Two years.

Donald R. Lennon:

International, things were heating up more and more. The war was going on in Europe. Is there anything specific about your period on the TENNESSEE that you recall?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Not that reached the level down to where I was down in the junior officer's mess. We visit the World's Fair on the East Coast and the World's Fair on the West Coast. It was kind of business as usually. Every now and than, you heard a little something. We said, “Oh! Those poor Japanese. If they are ever crazy enough to go to war with us, we would wipe them out in six weeks. We don't have to worry about them. Their ships run upside down. When they launch them, they capsized.” That was generally our attitude about the Japanese.

Donald R. Lennon:

We were shipping scrap metal just as hard as we could during that period.

Aldon J. Laborde:

We began to hear some stories about the North Atlantic Patrol. I had a couple of classmates on destroyer duty up there. I remember, we were doing some convoying or something up there. By 1940, that was going on. At my level, we were not getting ready for war.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was pure peacetime cruising.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Pure peacetime. Go out for training. Go to Brimmerd in Washington for dry-dock every year or two, a couple of months. Go in for the fleet exercises four to six weeks somewhere out in the Pacific and fire the guns a few times and cruise around and go in for liberty somewhere. We did it once in the Atlantic as well. In 1939, we would up at the World's Fair in New York. Had some exercises off of Norfolk. I am sure they had some implications at the highest level of planning that related to World War II. At our level, all we wanted was where we were going to next and how liberty was in that place.

Donald R. Lennon:

Good duty for a young, single man.

Aldon J. Laborde:

It really was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it ever make you wonder how your eyesight was good enough for DE duty, but not good enough for the regular Navy?

Aldon J. Laborde:

Well, I wonder but when you are in the service in that environment, you just understand those things. Regulations are regulations. I can state it even better. Here I was I couldn't see well enough to be a peacetime Naval officer even in a shore job, sitting behind a desk. But, I was good enough to be in command of a ship all through World War II. I never had a day's shore duty other than moving around and short training courses. That sounds very ironic but I just kind of knew that is how it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I have talked to individuals, Admiral Shelton Kinney among them, and claims that DE's won the war. He is very big on DE's.

Aldon J. Laborde:

He was one of the few regular Navy DE guys. They did a good job out in the Pacific. I wasn't involved in that; Leyte Gulf, the early days of the war when they knocked off a lot of submarines off. Kind of held the Japanese fleet at bay till they were able to find Holsey and get him back into the picture. These were all reserve guys who did a great job. You just can't over state how good these fellows were. My exec had come out of the Sea Scouts from Portland, Oregon, a fellow named Walter Gadsby. He got command of my ship, the BLAIR. He was as good a naval officer as I have ever been around. Most of them were. They were serious, they were sincere. We had the benefit in that war of everybody seeing it as a thing to do and a job that needed to be done and not wondering, Why am I here?. We didn't have the problems that they had in Vietnam, for example. We had a common enemy. Rightly or wrongly, the Japanese were a bunch of devils and so were the Germans.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any last thoughts any of the people you came in contact with during your naval career that come to mind or any Company C stories?

Aldon J. Laborde:

I didn't have a very exciting career as combat goes. No real hand to hand combat in any way. I can't really think of anything terrific.

Donald R. Lennon:

Infrequently, things will happen on board ship and there is a lot of interest in documenting the sub chasers and the DE's and their role in the war. Both in the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Aldon J. Laborde:

I remember one thing about the sub chasers. I was in Miami and I was kind of an instructor afloat for awhile, trying to teach some of the guys. We went out and here was

this big smoke on the horizon. We went out to see what it was all about. Here was a bunch of guys in a lifeboat. They said they were headed for the beach. We stopped to pick them up. They said, “No. That is all right. We will make the beach.” He said, “Go after those German sons-of-bitches! Don't waste time with us!” We said that was an America ship for sure. They didn't even want us to pick them. They said that they would make it to shore. They wanted us to go get a submarine. Little did he know how little we knew about getting a submarine. We pinged around there for awhile.

Donald R. Lennon:

No sign of them. Another classmate of yours was Hank Lauerman. He went into sub duty himself. Well, I believe that is about everything I have.

Aldon J. Laborde:

After the war, I was in ODECO. I was fortunate enough to hire three or four ex-Navy guys, classmates, in our business. With out exception, they did a great job. I also hired a couple of West Points. They all suffered from the same problem of not realizing their capabilities after they had served a career in the Navy or the Army. They did not know that they had a lot to offer. They were very defensive and apologetic about their backgrounds and their resumes. Their resumes had stuff like Army War College, Machine Gun School, Optical School and things that were of no interest to civilian employees. I remember one guy who was the business manager of the LUCKY BAG, retired Admiral Woodrow W. McCrory. He had just retired as Commander Naval Forces-Korea by then. He sent me this resume and wanted to know what I thought of it. Then he would know how to ask for a job. I looked at it and I called him up. I said, “Mac, anybody who can hire you hadn't got time to read all of this crap. If you are looking for a job, come on down because I know what you can do and it has nothing to do with all that stuff in your resume. He was there the next day.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think the Naval training, the academy engineering, and everything would be ideal for the business you were in.

Aldon J. Laborde:

Yes. I don't think any question or most any business. Ninety percent of what you are doing in the Navy of managing a ship and handling people fits no matter what you are doing. It would fit in what you are doing and what I am doing, but they don't know that. They are fish out of water. A lot of good men you find retiring over there in Whispering Pines and around Norfolk and down around Jacksonville mostly because they don't know how to go get a job. There they sit at fifty-five years old never hit another lick at snake for the rest of their lives. I get real aggravated. They live on a Navy retirement, just barely enough to survive on. They have developed a lot of expensive tastes along the way. I get pretty frustrated. There is a lot a talent going to waste.

Donald R. Lennon:

At East Carolina University, we used to be top heavy with retired military.

Aldon J. Laborde:

I bet because it is one of the favorite places around your part of the world.

Donald R. Lennon:

I mean on the staff at the university.

[End of Interview]