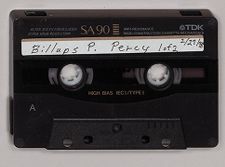

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #169 | |

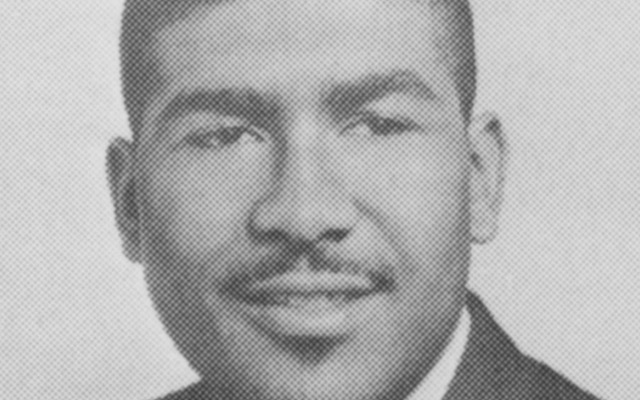

| Billups P. Percy | |

| USNA Class of 1943 | |

| February 27, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, give us something of your background. You were born early in January 1922. If you could share with us where you were born and where you grew up.

Billups P. Percy:

My early life was not exactly one that you like. I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. My father, a Harvard law graduate, was a very distinguished lawyer. He loved to hunt and play golf. He married a beautiful lady from Athens, Georgia. In 1929, when I was seven years old, he killed himself. I guess I've never quite gotten over that. I've never known why he did it. My two older brothers don't know why either. My oldest brother, Walker Percy, is a writer. He died in 1990, eight years ago. He died without knowing. The only thing Walker felt was that in the modern day with the things they have for depression, our father should not have killed himself--but he did. Immediately, my mother was left with three boys. We had this beautiful home in Birmingham. The family came together to help. We moved to Athens, Georgia, where my mother was born. We lived there a year with my grandmother. She was a wonderful lady.

After a year, this gentleman came over from Greenville, Mississippi. I can still remember seeing him when he first came there. His name was William Alexander Percy. He was my father's first cousin and they had been great friends. Uncle Will was a bachelor. He came to see my mother and to bring us over to Greenville. That is the way it worked out. We spent a year in Athens and then we moved to Greenville, Mississippi, where my Uncle Will lived. His mother and father had just recently died. His father was U.S. Senator Leroy Percy. Uncle Will was living in this big house by himself, so we moved in. It was a unique house.

I can't recall how many years I spent there before I went off to school. The house was always filled with people. I remember this writer who came to stay for a week and ended up staying a year, writing a book. It was like a big hotel. You never knew who would be at dinner, but I can remember some famous people, particularly literary people.

I guess we moved to Greenville in 1931. I was nine years old. My two older brothers were thirteen and fourteen. I went to Greenville public schools, which incidentally were about the best schools I've been to. It's unbelievable what has been happening to public schools since. But one tragedy in my life wasn't enough. In 1932, when I was ten years old, my mother took me out in the car. I never knew where we were going. She ran off the bridge into the water and drowned. I tried to save her, but I couldn't do it. The first ten years of my life were not so good.

I guess the one person that held me together was my Uncle Will. We called him Uncle Will. He took me for psychiatric help to get me through this period. He was so great and understanding. I would wake up with nightmares. Although he was a practicing lawyer and would have to get up early in the morning, he would stay with me

as long as necessary trying to comfort me. He was also a very, very literary person. He used to read me a lot of Greek mythology, which somehow seemed to work pretty well. He was a classical scholar, who finally wrote his own autobiography called Lanterns on the Levee, which is a magnificent book. I told many people that after Jesus Christ, I think he was probably the greatest person who ever lived. His mother and father had died and he was reasonably well off. His father had been a cotton planter.

Uncle Will didn't like law and could have traveled--which he loved to do--or written poetry. In fact, he had three published books of poetry. He also played the piano and was almost a concert pianist. Instead of that, Uncle Will kept at the law to support us and to bring us up. He finally died, I think at about the age of fifty-five or so, from high blood pressure, cardiac problems, brain damage.

In any event, going back to my personal life, Uncle Will would make these decisions. We never knew how he made them, but he made them. My older brother stayed in public schools in Greenville until he graduated from Greenville High School. Uncle Will sent my second oldest brother, who is still alive in Greenville, Mississippi, to the Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia. Then for reasons I've never known, he sent me to the McCallie School in Chattanooga, Tennessee, for the ninth grade. I was thirteen years old, so it was 1935. I stayed at McCallie for four years. It's a semi-military school. I think, unquestionably, it was the best school I'd ever been to. It was just absolutely magnificent.

I think it was my senior year, when maybe I was home for Christmas or something, that Uncle Will took me to one side--since the house was always full of young people--and he said, “Would you consider going to the Naval Academy?”

I said, “What's that?”

He said, “Well, it's like West Point, but it's in Annapolis.”

I said, “Uncle Will, I really planned to go to the University of North Carolina.” That is where my two brothers went. As a matter of fact, a good friend of mine at McCallie was going to be my roommate.

He said, “Why don't you do this? I got you an appointment from this congressman. You take the test. If you don't pass it, you go to North Carolina for a year, and then you can go in without the test. You know, maybe you don't want to go.”

I said, “Okay.” I took the test at the Chattanooga Post Office. It was the Naval Academy entrance exam: one in math and one in English. I barely passed both of them. Incidentally, Uncle Will had gotten in touch with the headmaster at McCallie to try to help me as much as they could to prepare for these tests through tutoring. I passed them both.

I was something of a hero at McCallie for going to Annapolis. In those days, you didn't look to the future too much. The headmaster called me in, congratulated me, and said, “As a reward for passing these tests, you are exempt from your final exams at McCallie. While everybody else is taking their exams, you go home. Then you can come back for graduation.” Well, that was all I was thinking about. I went home, where I was kind of a hero as well. The girls seemed to like the idea. I just had a wonderful time, never thinking there were other consequences. I went back to McCallie for graduation and said my tearful good-byes to my friends and everything.

Then I realized there was more to it. In thirty days, I was ordered to report to the United States Naval Academy. I did not like the Naval Academy. I wrote many

resignations, which my older brother Walker, who was at Columbia Medical School, taught me how to do properly. I didn't like the Academy because it was absurd academically. The hardest course in the Naval Academy was supposed to be physics. The way it worked in Annapolis was they took in a certain number of students--I think we took in 850--and knew how many they wanted to graduate--615. They planned to get rid of most of the excess students in the first year. People would either fail out or quit. It was my understanding that those they didn't get out the first year were going to get out when they took physics.

I remember going to the first class in physics, having gotten through the first year. Incidentally, after you get through the Plebe Year with all the hazing, it's kind of downhill after that. I gave up thoughts of resigning. It was obvious that a world war was looming. Later on, it became obvious why my Uncle Will had sent me to the Naval Academy. He knew the war was coming, even in 1939.

We used to march to our classes, so we marched to physics class and sat and waited until the instructor came in. We knew his name was Lieutenant Commander Knapp. He was known as “Bonedome” Knapp. He was bald-headed. He came in and said, “Sit down, gentleman.” We sat down. He said, “I'm Lieutenant Commander Knapp and I'm your instructor in physics. It is regarded by many as the toughest course in the Naval Academy. I can verify that, because when I was a midshipman, I failed it.” He was telling the truth. I said to myself, “What am I doing? How can this be?”

But I decided I was going to stick it out. Another friend and I found out that there was a lot of cheating going on. I won't go into the details of it. We reported it to a four-stripe captain, who was the officer in charge of our battalion and the highest ranking

officer except for the superintendent. This friend of mine went in to tell him what we thought about this cheating, where people would take exams and then tell their friends about the exam, who would then take the same exam later on.

He said, “Oh, don't worry about that. That's been going on for years.”

I think we may have been seniors then, first classmen. We both got out of there and didn't say anything else. Anyway, I graduated from the Naval Academy and with the exception of the day of my marriage, I think that was the happiest day of my life. We threw those caps up in the air! By great, good fortune because of the war, our class got out in three years. I entered in 1939 and got out in 1942.

Donald R. Lennon:

You grew up in a background with humanities, arts, and things of that nature, and the regimentation and the type of instruction that you had at the Naval Academy was diametrically opposite.

Billups P. Percy:

I didn't object to that too much. I think, looking back on why my Uncle Will sent me to one military school and then to another military school was that he knew the war was coming. I think he sent me to McCallie, which really wasn't that military, because I had been a bad, troublesome kid. I wasn't bad because of any of the family problems, but because I liked trouble. I was in trouble a good bit, but nothing really serious. I think he thought I needed the discipline. I will give this to the Naval Academy. It taught me and made me very disciplined. I am very proud of my discipline and always have been. I got a lot out of the Naval Academy.

One of the things I didn't like was the pathetic academic climate there. Let me make a curious exception here. There was one department in the Naval Academy that was superb. That was the mathematics department. All of the professors were civilian.

They had their own case books and textbooks. But by and large, if you learned something at the Academy, you did it yourself. Lights would be out at ten o'clock, but in the heads--what civilians call the bathroom--lights were kept on and people would be studying all night. You didn't get it in class, so you got it on your own. The lights proved to be very helpful.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Academy is notorious for no instruction.

Billups P. Percy:

Right. The rule of the Naval Academy was that every instructor had to give you an exam every day. We would go to class under Lieutenant Commander Knapp and he would say, “Gentlemen, are there any questions?” There was no point asking Lieutenant Commander Knapp any questions.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because he failed.

Billups P. Percy:

He failed the course when he took it. We knew we couldn't stonewall our way without getting an exam. He was required to give an exam. We just went ahead and took the exam. Overall I did get something out of the Naval Academy--a sense of discipline. It did not develop just from the hazing but from having to do things myself. That was the only way it would get done. Plus, I made a lot of good friends. I had some very fine classmates. Again, I was thrilled to death to get out of there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you involved in any extracurricular activities?

Billups P. Percy:

The one of any note at all was largely because of my Uncle Will, who had the only tennis court in Greenville, Mississippi. I knew how to play tennis. I had played on the tennis team at McCallie School. I made the tennis team in Annapolis. The beauty of being on the tennis team, particularly during Plebe Year, was that you had a training table. A lot of the hazing went on in the dining room but the tennis team sat at a training

table. I enjoyed the tennis team very much. We made several trips. I remember going to West Point and other places to play tennis. That was my main extracurricular activity.

Right before we left, I came back to Greenville for the last Christmas leave before graduation. This was Christmas of 1941. Pearl Harbor had just happened. I had a wonderful Christmas. I was in uniform, and the young ladies seemed to like my uniform. I liked Annapolis then because I was getting out. The house was just packed with people the whole holiday. My Uncle Will lived downstairs. There were really six apartments; six suites upstairs, where we all lived with friends who stayed with us. I noticed something different--which was a little confusing to me--about Uncle Will. I noticed he was in his kimono bathrobe the entire time. I also noticed that he would forget things and joke. He called me the wrong name once. I didn't think much of it. I went back to the Naval Academy early in January of 1942. Towards the end of January, my brother Walker called me from New York and said Uncle Will had died. I just couldn't speak.

He said, “You get permission from Annapolis, and I'll meet you in Washington. I'll fly down, then we'll fly down to Greenville.”

I went to his funeral. I never really fully recovered. My brother, Walker, who was a writer and had written many novels, wrote the introduction for the Lanterns on the Levee paperback edition. He said, “We might not have killed Uncle Will, but he sure didn't write much poetry after he took us on.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Your brother was something of a legend at Chapel Hill.

Billups P. Percy:

Yes. Both my brothers went there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he practice medicine at all?

Billups P. Percy:

No. He graduated from Columbia Medical School. He contracted tuberculosis as an intern in pathology. I think he said nine of the sixteen interns got TB. As a result, he spent several years in sanatoriums. One was the Trudeau Sanatorium and another sanatorium up east. To his bitter regret, Walker was not able to participate in World War II. Lying on his back month after month, he read a great deal. Luckily, he always liked to read, but he never wrote much. He began reading some very deep stuff to my mind, such as the existentialists, like Sartre, Heidegger, and people like that. Maybe TB was the best thing that ever happened to him. Walker never really wanted to be a doctor. He probably would have been a pathologist or possibly a psychiatrist.

Once Walker recovered, he got married and turned to writing. I went up to Chapel Hill for his graduation. He was a senior when my other brother was a junior. They were both Sigma Alpha Epsilons. Walker was also Phi Beta Kappa, but nobody in the SAE house ever saw him study. He used to love to go to movies. The name of his first novel was The Moviegoer. Walker was absolutely brilliant. My other brother was even more popular at UNC-CH. He became president of the Sigma Alpha Epsilons, but Walker certainly made a name for himself in the field of writing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Lanterns on the Levee--the title's name is very familiar. I don't remember anything about it, but I remember the title of it.

Billups P. Percy:

I don't know how many times I've read it. It's just about my uncle's life and his family, from the beginning when they came over from England and right on through to present day. There have been, I think, seven generations of Percys in this country that came from Northumberland in England, near Scotland. He traces his ancestry and relates what it was like after his parents died, his inheritance, and his raising us and what he tried

to teach us. Uncle Will also related his experiences in World War I, where he fought in France and got the Croix de Guerre, the French medal. His mother was French, Camille Bourges. She was the senator's wife. Uncle Will loved France. I guess one of the things that I inherited was an undying love for France. I guess my wife and I have been there fifteen times. We used to rent a little farmhouse, and sometimes took the children. When he was gone, I was an ensign in the United States Navy after graduating, of course, and the war had started. I was just terribly excited. I won't say that I was a war lover, but I was excited. We submitted our preferences for what kind of duty we wanted--battleships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, Marine Corps, and the new one, PT boats. I said, “That sounds good," so I put in for PT boats and got it. That began my PT career. I went to PT school up in Melville, Rhode Island, and then was assigned to a squadron that was heading out. I think there were four boats on each tanker. They shipped us all the way through the Panama Canal to Pearl Harbor and finally to Noumea, New Caledonia. Then we got off the tanker at Noumea. On our own, we went up to the Solomon Islands. I spent fourteen months on the Solomon Islands, most all of it as a PT boat captain. My first patrol off Guadalcanal was on my twenty-first birthday--January 3, 1943. I stayed with PTs until February of 1944.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lot of your PT officers were Reserve officers.

Billups P. Percy:

Most of them were. There was only one other classmate of mine, an Academy graduate in our squadron, a fellow named Bart Connolly. He was a great friend of mine. All the rest were Reserves. I don't think career-oriented graduating first classmen thought that PT boats were a good thing to get into. They were brand new. They became prominent because Bulkeley rescued General MacArthur in the Philippines with them.

Bulkeley sold a bill of goods to President Roosevelt and hundreds of them were being built.

I'll never forget those fourteen months in the Solomons. I guess there are two things I remember most. One was that when I got there, I was six feet tall and weighed about a hundred-fifty. When I arrived back in the States in February 1944, I was six feet tall and weighed ninety-eight pounds. We patrolled every other night. I only missed one patrol for illness, for which I'm very proud. I had dengue fever and there was nothing to eat. I never had much of an appetite anyway, but the only food I remember was Spam and powdered eggs.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where you were headquartered, they didn't have a mess hall?

Billups P. Percy:

It was just horrible. They served you, but again, I really felt bad. I don't think I ever had any fever. I never went to the doctor, but I just felt bad pretty much the whole time. I'm very proud that I only missed one patrol. I was delighted to get back to the States. I'd completed my tour of duty. I was delighted to be awarded the Silver Star Medal for which I was chosen shortly before leaving. I was given the Silver Star when I got back to the States. I guess my main memory, aside from some of the very exciting patrols, was getting to know Jack Kennedy, whom I got to know quite well.

I have written a piece called “JFK--The Last Time I Saw Him," which I'm happy to say is going to be published in the next issue, the summer issue, of a fairly new magazine called DoubleTake. It's a very handsome magazine. Here is the most recent copy published in Durham, N. C. It's very well endowed because the magazine has almost no advertisement. They have accepted my article. It will appear probably around June 1, [1998]. I think it's a good piece and they apparently did, too. I've always thought

of writing as being fun, but most of my writing consisted of legal writing plus writing letters to the editor of the newspaper, which I love to do. I am excited about this article coming out in DoubleTake. DoubleTake is hardly ever seen in the newsstand because it's largely by subscription.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, who is Will Percy?

Billups P. Percy:

He's my son. By pure coincidence, he interviewed Bruce Springsteen, which also appears in DoubleTake magazine. I'm very delighted about that. He's a young lawyer here in town and is now thinking of taking up interviewing as a career. He enjoyed so much of the time he spent with Springsteen.

I won't go into my friendship and experiences with Kennedy because I don't want to give away what my article is about. I urge people to read the article if they will. It simply talks about knowing him in the Solomon Islands.

While at the Solomons, if your boat wasn't ready for any reason, such as when something was wrong with your engine or something, the boat captain could either stay in, or if he wanted to ride, he could go out with somebody else. I used to do that frequently, because I enjoyed it for some reason.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us the nature of your patrols.

Billups P. Percy:

For fourteen months, we started at Tulagi, which is near Guadalcanal, and then we went from Tulagi to the Russell Islands, from the Russell Islands to Rendova, from Rendova to Treasury, and from Treasury to Bougainville. We went pretty much in a northwesterly direction, from Tulagi up to Bougainville.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you operating out of any kind of naval facility that had been set up?

Billups P. Percy:

We set up our own base. We had a tender at Tulagi. We used to eat on the base. All I can remember is the mosquitoes. We slept in tents with mosquito netting since the mosquitoes were so horrendous. I think some of our health problems were derived from mosquitoes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Malaria?

Billups P. Percy:

The routine normally was at about five o'clock we ate early dinner, such as it was, and went in to be briefed by the intelligence officer. I liked him very much. Everybody liked him. We called him “Whizzer” White. Whizzer had been an All-American football player at the University of Colorado. He would tell us what we were likely to meet on the patrol, whether it be the Tokyo Express--that is what we called the Japanese warships--or what. It's interesting that many years later in the 1960s, Whizzer White, Byron R. White, was appointed to the United States Supreme Court by Jack Kennedy.

Whizzer would brief us, and we would go back to the boat. On a boat generally speaking, there was a boat captain (which was me in this case), the executive officer, and then usually eight or nine enlisted men. We would go back and tell them to get ready to get underway. We would leave about dusk. We would brief the crew about generally what to expect. Then we would go out and patrol all night. We generally patrolled in pairs--not always, but generally. I was usually the rear boat because I had just made ensign, so most of them were senior to me. Our job was to intercept and attack warships. In my fourteen months out there, I actually never fired a torpedo. We had four torpedo tubes. I was involved mainly in attacking armed barges that were evacuating Japanese troops.

When we got to Guadalcanal, it was being bitterly contested, but finally we began winning. We moved the Japs up to New Georgia. We took New Georgia and moved through to Vella Lavella. Next, we moved them up to Bougainville, and finally we moved them out. As they were evacuating from one island to another, the PT boats would intercept them and attack them.

Donald R. Lennon:

You concentrated on the smaller vessels. You never took on a destroyer or cruiser?

Billups P. Percy:

Right. I think the only destroyer I saw was the night Jack Kennedy's boat was run into, because I was in another boat. He had asked me to ride with him on the PT 109. I thanked him and said I had agreed to ride with this other guy. All of it is very hazy. I think I got a brief look at that collision.

I never fired a torpedo at a warship. All and all, my PT boat experience was rather disappointing although I did have some very narrow escapes with some barges. One night we were chasing some barges and ran aground with another boat right off Vella Lavella. I write about this a little bit in my article about JFK. No, actually that is not true. I've written another article about that, which I'm trying to get published, called "That Night Off Vella Lavella." Anway, we ran aground on this coral reef, and there was nobody anywhere close to us. We were about maybe a mile off of the Japanese held island, Vella Lavella. We could see the campfires over there. We knew that at dawn that was the end of it. The two boats were high and dry. I met with my crew. This was in the fall of 1943. The crew and I were pretty close by then.

I said, “Look, we got to decide what to do. We are going to keep trying to use the radio and get help, but it doesn't look good. What do we do at dawn? They're going to

come out here. As I see it, we've got two options. One is to surrender. The other is to meet them with all guns firing.” I said, “Frankly, my view is to meet them with all guns firing because I don't know about you people, but I'm pretty much acquainted with the Japanese history of torturing people. I know what they did in Manchuria and Korea. You all know what they did in the Philippines, the Death March and all." I said, “Well, it's up to you.” They kind of bowed their heads. We gathered around in the dark on the deck and took a vote. It was unanimous.

I began setting up all the gunners' mates to get ready. First, I set up the four 50-caliber machine guns, then a twenty-millimeter gun, and finally a thirty-seven-millimeter gun. We got all the ammunition ready. This was about three-thirty or four, I don't remember. On the other boat, Stu Hamilton was the boat captain. We were both on the radio all the time, and he raised another boat, just barely in range. Stu told them where we were as best he could. Maybe an hour before dawn, they showed up. I said, “This is the greatest feeling you'll ever have.” They rescued us. Before they had arrived, I didn't want the Japs to get anything worthwhile, so I did sort of a tragic thing. I had my machinist mate take a sledgehammer and destroy our three engines. They were Packard V-12 hundred octane gasoline engines. They were the most beautiful machines I've ever seen. I didn't want the Japs to have them. My machinist mate was almost crying when he did it. This is when we thought it was all over.

Donald R. Lennon:

You abandoned the boats?

Billups P. Percy:

Well, we were rescued. If we had fought the Japs and were all killed, we didn't want anything left on the boat.

One other thing if I can mention it--I'll never forget--there was something in the control room downstairs called the IFF. It was a very advanced electronic device. This was, you know, fifty-five years ago. It meant Information Friend or Foe and apparently identified a radio signal or any emission of any sort as being friend or foe. It said, "In case of capture, destroy." I had always wondered what would happen if I pushed that button. I went down and pushed it when I thought there was no hope at all. Smoke poured out of it. Later, I saw a T.V. show “Mission Impossible.” It started out with a guy pushing one of these things in.

We were rescued and got back to the base. Of course, we left the boats there, high and dry, and were debriefed by the intelligence officer. Actually, it was the base commander because two boats had been lost. The one thing I remember him asking me was not about the travail we'd been through, running aground chasing these barges, but rather, “Why did you destroy that IFF? Don't you know how expensive they are?” I thought to myself, he must be kidding, but then I realized he was not kidding.

I said, “Commander, I guess you're right. If this ever happens to me again, I'll bring it back.” That apparently satisfied him. I will never forget that remark. I won't say he was typical of the PT senior officers, but I was totally unimpressed with the top command.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like they would be more concerned about that not falling into the hands of the Japanese than the cost of one of them.

Billups P. Percy:

Considering the expense of the IFF, he thought I should have dismantled it, apparently, and brought it back. In any event, when I left the Solomons in 1944, it was an extremely happy day.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, any other experiences on your duties there in the Solomons that you want to share?

Billups P. Percy:

On most of the patrols, we would see nothing. We would just go out, patrol back and forth at dead low speed, and come in at dawn. There are two things I really should mention. Early on, right after I became boat captain, a friend of mine, Mud Richards, who was also a boat captain, came to me and said, “Look Percy,”--everybody called me Percy--“our boat won't work. Can we take your boat out?” My boat was the PT-123.

I said, “Sure.”

He and his exec, who was also a very good friend of mine and had gone to prep school with me many years ago at McCallie, Alec Wells, took my boat out. This was while we were still at Tulagi. They left about dusk, six or six thirty. On the way out, as it developed, they were bombed by a Japanese bomber. It hit them head on and killed half the crew immediately. This was on the way to the patrol site at Guadalcanal. They spent the whole night fighting sharks.

They were picked up at dawn, and the survivors were brought back. Of course, I was very sorry about losing the boat, my personal belongings, and everything. However, that was nothing compared to what had happened to these men. Alec explained to me what had happened after they had dropped the bomb. Apparently, they thought the bomb was dropped by “Washing-Machine Charlie.” That's what we called the Jap who would circle the area frequently in a very noisy, single-engine plane, apparently with only one bomb. This time it hit.

Alec was from Daytona Beach and had known what sharks were like. At that point, it was well known that at that area near Guadalcanal, which was called Iron Bottom

Bay, because more ships had been sunk there than anywhere else, that there were sharks from all over the world. The boat was sunk probably at eight or nine o'clock--I don't know exactly what time--but they were on their way out. They fought the sharks for almost twelve hours.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had life rafts on board?

Billups P. Percy:

Yes, well, life jackets. Everybody wore life jackets.

Donald R. Lennon:

They never had a life raft to get in?

Billups P. Percy:

Yes, they had them, but the boat had been destroyed.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were actually in the water?

Billups P. Percy:

They were in the water. I think there were maybe five or six survivors. Alec, from his experience with sharks, made the survivors form a circle facing out. As the sharks would approach, they would start kicking. He knew that sharks were very cowardly. The one thing sharks don't want is somebody to contest them. Somehow, through Alec's leadership, the survivors kept them off all night until they were picked up. No one was killed by sharks. That was an event I did not participate in, but obviously remember very well.

They gave me another boat and I took my crew to it. All our equipment was gone, but that didn't matter.

There are two other instances I should mention. One was when we were ordered to go to an island. We were based in Rendova at this time with several other boats. We were ordered to go to an island with the beautiful name, Kolombangara. The island was held by the Japanese. Our assignment was absolutely mad. When you're twenty-one, you never think you're going to get killed, but I did wonder, “What in the world?” In each of

the boats, we had two or three demolition experts, and our mission was to go into this Japanese-held harbor. The experts would get on the docks and blow the docks up. It didn't sound like a very wise decision to me. I remember while approaching the island, gunfire came from up above. Finally, the orders came from the headman to turn around and go back. In the melee, there was a lot of shooting going on from this island. I could tell that the boat I was paired with had been hit. It was kind of lying dead in the water there, so I pulled alongside and sent my people aboard to see what had happened. A good friend of mine, boat captain Sid Hix, was lying dead in the cockpit. He had been killed at the steering wheel in the cockpit. I put my exec on that boat. We went back to the base. That night is one I won't ever forget.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now what was a normal crew for those boats?

Billups P. Percy:

Well, there were two officers, sometimes three. Apparently, if you wanted three, you could have it. I know Jack Kennedy was reported to have three, but normally there were just two plus eight, nine, or ten enlisted men.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were ten to twelve in all?

Billups P. Percy:

Yes, ten to twelve in all. All that night did was heighten my questions concerning the ability of the people in charge. What in the world?

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like they would have sent in frogmen from offshore rather than trying to drive in.

Billups P. Percy:

This was a suicide mission, and for what? To blow up these docks. In Annapolis, you learn to take orders. One thing you definitely learned at Annapolis was you never question orders. If you didn't learn anything else, you learned that. You may question it later on, like I'm questioning now; but at the time, we did wonder about it. We didn't

know how we were going to get out of it. Anyway, we got out of it, because the senior officer commander saw that we were in trouble. We turned around and went back.

Of course, the other event I could never forget was the night Jack Kennedy had asked me to go out since my boat wasn't ready. I told him I was ready to go out with somebody else. We were in the same area off Kolombangara--the same island. This happened maybe a month before the event I just described, while we were still at Rendova. As I say, I thanked Jack. I'd ridden with Jack before because I liked him and the other people on the 109. Well, I went out on this other boat, and I had no duties at all. I just went out for something to do. If you didn't go out, what would you do? You'd stay back and read.

Donald R. Lennon:

You could also get eaten by mosquitoes!

Billups P. Percy:

Yes. We used to play a lot of cards. I played bridge a great deal with Jack Kennedy when we were not on patrol. I went out for something to do. I was awakened some time after midnight. I was rubbing my eyes and looking to see what had happened. What had happened--which it's hard to know how much I saw or how much I reconstructed from being told--was that up ahead somewhere, Kennedy's boat had been run into by a destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it a Japanese destroyer?

Billups P. Percy:

Yes. It was proceeding at a very, very high speed. I made it clear to this boat captain--and I won't go into what his name was--that we should go and look for these people. He said "No." He was going to radio back to the base and have a PBY, the patrol aircraft, search in the morning. No one ever went to look for survivors. I just didn't understand. After a couple of the boat captains had been calling this boat and that boat,

they finally figured it was the 109, because they didn't answer. Well, it was assumed that there were no survivors. I never understood.

Donald R. Lennon:

I thought it was standard procedure to go see unless you were under attack.

Billups P. Percy:

I did too. I urged with everything I possessed to try to find it and at least look for the boat. At that point, I think the executive officer on the boat agreed with me. The boat captain was having none of it. Of course, I thought about that frequently. What else could I have done? Well, the only other option I had was mutiny. I could take over command. Of course, mutiny is a pretty serious offense for a twenty-one year old. I did nothing, but I pressed my point as hard as I could. I never understood whether he thought there were no survivors or what it was. My recollection is that we almost ran into the destroyer. This may be important. We saw the destroyer after it ran into Kennedy's boat, which we found out about later. At least I did because I'm not sure I actually saw the collision. However, the boat I was on had to dodge to miss the destroyer, which obviously had been hampered somewhat by having run into this PT boat.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the destroyer intentionally trying to run PT-109 down, or was it that they just got in the way?

Billups P. Percy:

Oh no, I'm sure it wasn't. The destroyer was proceeding at a very high speed. That night, it was very dark, and the destroyer split the PT boat in two. The thing I remembered was the destroyer fired at us as we turned away in order not to avoid running into it. I can beautifully remember those tracer bullets. They were, I think, green tracer bullets. At night, maybe every tenth bullet would be a tracer. You could see it. It may be that those bullets discouraged the boat captain. I don't know. I can't speak for the boat captain. I was very upset.

I'll never forget the incident because Kennedy and the remainder of his crew survived on these little islands for about eight days through the help of natives and a coast watcher. They were picked up by PT boats that got word from the coast watcher. I went down to meet them--the survivors. I'll never forget when they came off the PT boat that came to get them. The executive officer, a guy named Lenny Thom, was about six-three or six-four, two fifty. He had been an All-American football player from Minnesota. As he got off the boat, he saw me. He came over and said “Perce”--Lenny called me Perce--“Perce, why didn't you come look for us?” I never had anything hit me quite like that in all my life.

I said, “Lenny, it wasn't my boat.” Again I rethought that night many times. I guess if I had to do it over again, maybe I would have participated in mutiny. I really just wasn't sure enough. I had just woken up from a sleep. I had been sleeping topside. As it turned out, luckily the survivors got back, thank God. Those were the events that I remember most: the PT-109 incident and running my own boat aground up in Vella Lavella.

Donald R. Lennon:

When the boats ran aground, there was no chance when the tide came in to lift them off?

Billups P. Percy:

It was absolutely high and dry. When I tried to get it off, I went full speed astern, but nothing happened. You could see the coral right on the rear of the boat. The boat ahead of us, which was Stu Hamilton's, had apparently run aground in exactly the same fashion.

Another thing I should mention to make it clear about the PT thing was that it was at Bougainville. I guess I was at Bougainville maybe two months before my tour of duty

was over and I was sent back to the States. I'll never forget that a lot of times we were in Condition Red. A Condition Red meant air attack imminent. We got used to that. Yet, for the first time in my career at Bougainville, we had a Condition Black. A Condition Black meant an invasion was imminent. What apparently happened was that we had run the Japs off Bougainville. It seemed that the Battle of the Coral Sea was going on at that time. The word was that the Japs were going to try to retake Bougainville. Where that idea came from, I don't know, but we had a Condition Black. We had some very heavy air attacks made by the Japs. I remember going out and being excited by these bombs. I don't want to sound brave, but all the other people got in foxholes. I remember how the bomb bay doors opened, but finally I did get underground.

Of course, they were never invaded. I left after fourteen months of ups and downs. I was very happy to get the Silver Star. I don't know what the citation said about any particular act of bravery. I think mainly it was for my endurance. My endurance got me the Silver Star because I could have pled sick and gone to the tender.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had a fairly high casualty rate among PT boat crews, didn't you?

Billups P. Percy:

It was pretty high. I don't remember exactly what it was. I'm sure there were PTs somewhere other than the Solomons. I'm sure the highest casualities were in the Solomon Islands because we were supposed to take the place of the destroyers. Recently I received a copy of an article printed by a friend of mine named Dick Keresey, who was a Reserve PT boat skipper. It was an article printed in the Naval Institute Proceedings. There was a very flattering part in it about Phin Percy. I'd forgotten that I had ridden with him a couple of times. This particular night was a very exciting night. He said he didn't like his exec. I think he told his exec not to go since he had a guy named Phin

Percy aboard, who Keresey said liked combat. Keresey said that I was from an old Southern family and that I wanted to go after the enemy with torpedoes. It was nice to read. I've got the article back here.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened on that patrol that was interesting?

Billups P. Percy:

Apparently, there was a lot of combat. I don't know whether we sank something or not. I really didn't remember it. The thing that is amusing in it is, not only was I on the boat, but there was a commander, the commanding officer, on board as well. After the ordeal of attacking this destroyer was over, the commander says to Keresey, the boat captain, “This thing has really gotten to me.”

Keresey responds, “I know what you mean, but Phin Percy says the thing to take is carbon dioxide--carbon something or other. He says it's good for your stomach.” I don't remember any of that. Apparently Keresey did, though. I haven't been able to write him because I don't know where he lives. But I remember liking him when he was out there.

I would ride occasionally on other boats, but mainly I remember riding on Kennedy's boat. To show you how it was, one of the first times I rode with Kennedy, the boat in front of us dropped depth charges. At this time, we were in pairs. Apparently they had thought they had seen a submarine or something, so they dropped depth charges in front of us. Looking back on it, it was kind of a comedy act. You could make a movie on how really inefficient it was. The PT boats cost a million dollars apiece. They use a hundred-octane gas and would carry three thousand gallons of gas. You talk about a big expense there, but they did some good--no question about it.

When my tour of duty was over, I was sent back to Pearl Harbor. There we were told--I was glad to hear--that we could spend as much time as we wanted in Honolulu.

Then we would be sent to the States on a tanker. Our thirty-day leave would start when we got to the States. Three or four of us thought that was a good deal and decided to stay in Honolulu. I think we stayed there two days. I never disliked any place in my life like I disliked Honolulu during World War II. I hope it's better now. All I remember are the prostitutes and bad food. As a result, we got on the tanker and went to San Francisco. I'll never forget seeing that Golden Gate Bridge. Then we branched out from there. Four of us came to New Orleans. I went up to Greenville, Mississippi, where my brother LeRoy was. He was a bomber pilot, but I think he was back home then.

After my thirty days leave, which I enjoyed greatly, I went to Melville, Rhode Island, to be an underway instructor. Well, we are talking now around March. It was cold and windy. All our instruction was at night, which was as it should have been because the patrols were at night. I made one overnight. The seas were so rough that when I got up the next morning, I decided that I had had enough of PT boats.

I tried to find out what my future was. The best answer that I could get was that I would probably be an underway instructor for two or three months. Then I would probably be assigned to another PT squadron as the executive officer of the squadron and sent somewhere. Well, I decided that I had had it with PT boats.

I didn't want to use the Navy's money, so I went into town to a drugstore and used my own coins to make a phone call. You can't do this in the Navy now, but in those days the Navy was sort of, well, we all knew each other. I made a phone call to Washington to the Bureau of Naval Personnel because I had a friend there named Jim Calvert. I put the money in and got Jim right away. He remembered me since we were friends. He said, “Hey, Percy.”

I said, “Jim, I'm in PT boats. I don't like it. I want to get out.” Incidentally, Jim later became an admiral and went on to be superintendent of the Naval Academy.

He said, “What do you want to do?”

I said, “Well, you know, I came back on a tanker from Honolulu. I met a couple of chief petty officers, who were in submarines. I've never been on one, but I just liked what they said. I want combat.”

There are two things that I particularly like about subs. The pay and a half for submarines as hazardous duty is not it. One is that I don't want to come back injured. I don't want to come back with one leg, one arm, or some other injury like that. I want to come back whole or not at all. I understand with submarines that's the way it works. The other thing is I don't like noise. For some reason, I've never liked noise. On my youngster cruise from the Academy we were on a battleship, and I hated it. I said, “As I understand it, there is not much noise on a submarine.” They run silent, run deep and so forth. It was like he looked at his watch.

He said, “Perce, here is what we'll do.” It was around the middle of March.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's in 1944?

Billups P. Percy:

It was 1944. He said, “Submarine school starts April first in New London, Connecticut. I'm going to cut your orders right now. You will get them tomorrow. They will say you are detached from duty. You'll be given two weeks leave. You will then be ordered to report to the Commander Submarine Base, New London, Connecticut, on April 1, 1944.”

I said, “Jim, thank you.”

He said, “No problem.” That's exactly what I did. I spent two weeks in New York City, I think. I forget who I was with, just having fun. Then, I went to New London.

I was involved with submarines from April 1, 1944, to, I think it was, February the something, 1947, when I resigned. Virtually it was three years. I can say absolutely with my hand on the Bible, I enjoyed every minute of those three years. I have said many times that the move from PT boats to submarines was like going from the outhouse to the penthouse, although a penthouse is not exactly like a submarine. I've never seen such people. I did not know anyone who was there for the money. If you compare sub school to PT school, there is no comparison. We worked hard. When I graduated from sub school, I knew a good bit about submarines: about every valve, pipe, the machinery, the batteries, and everything. Immediately upon graduation, I was assigned to a submarine being built in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long was the school? When did you graduate?

Billups P. Percy:

After sub school, I think I got a week or two leave. Then I reported to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, which is right on the Maine border near Kittery, Maine. Actually, three other officers who were also assigned to the sub and I lived in a little house there in Kittery. I probably spent a good amount of time at the house because there wasn't anything to do. They were still building the submarine. We would go over there mostly everyday to see how they were doing. I played golf during this time. I've always been an average golfer, but I played golf a great deal. I also just enjoyed eating lobsters. As I recall, they were seventy-five cents apiece. Finally, the SEA ROBIN, my sub, the SS-407, was commissioned. I liked the captain from the instant I met him. Years later

when I resigned and he drove me to the airport in Panama, he and I were the last two plank owners, as we call officers who commissioned the boat. I think “Stimmy” is gone now, but I'll never forget him. Paul Stimson was the fairest and bravest, but he just knew when to take risks and when not to. Anyway, there were so many incidents. We made three successful patrols.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you?

Billups P. Percy:

A patrol is about seventy-five days. The patrol ends in one of three ways: you run out of fuel, you run out of torpedoes, or the seventy-five days are up. I never knew exactly how it would end. After strenuous training in Panama and in Pearl Harbor, we left on our first patrol. I don't remember the exact date, but the first patrol was in the Philippine Sea, in the general area of the Philippine Islands. It was a very good patrol. We got the award for what they call a successful combat patrol. You have to sink so many ships or get so much tonnage. We relied on the captain for that. After each patrol, we went for what they call R & R. We'd go somewhere for R & R--rest and recreation. We went to Perth, Australia, where there was a submarine base. We spent two weeks of R & R there and had a glorious time. Every Australian male of age was in the Armed Services. We had parties and the ladies were very nice to us. We just had a good time. Then we got our orders for the second patrol.

The second patrol was in the China Sea. That was close to the mainland of China. It was a very successful patrol. I don't recall the details. I remember we did have a clean sweep. A clean sweep means you sighted or contacted so many enemy vessels and sank them all. Then you were allowed to return with a broom tied around your periscope. We got a message from Chungking--we had broken the Japanese code early on--that said

these three Japanese cargo vessels were going to be at a certain place. Sure enough, they were there. We sank all three of them. We went back with a clean sweep since we sank some other vessels too. That was the second consecutive successful patrol.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you take many depth charges?

Billups P. Percy:

We had a few. Of those three patrols, I only remember one time where we thought we were in trouble from depth charges. Fortunately, the depth charge went off above us. You don't worry about depth charges because most of the pressure goes upward. It's when they go down next to you or under you that is the problem.

We were threatened once by a Japanese plane, I think, but we got away from that threat. After one sinking, true to the nature of our captain, we picked up survivors. We picked up quite a few Jap survivors and took them back to Pearl Harbor. Since we would go back to Pearl Harbor for R & R, that is where we took them. I think the Japs thought they were going to be killed, but we put them to work. We chained them in the forward torpedo room and put them to work shining brass. We had to give them something to do. We fed them and gave them a place to sleep. I think they were astonished at the treatment. When we got to Pearl, I don't know why the rules required this, but they left the ship with masks on. I'm sure they thought they were going to be executed like their people executed us as soon as Americans got off the boat. This was not the case. Instead they were put in a prisoner of war camp and probably were later released.

We had a good R & R at Pearl and then left on our third patrol, which was in the Yellow Sea. We knew that was going to be interesting. We had our third successful patrol. A lot of submarines made seven or eight patrols and had no success.

Let me, if I could, go back a little bit after the first patrol. During the first patrol, I was the communications officer. On a submarine, the captain can kick off any officer he wants and no reason has to be given. We had eight officers, including the captain and the exec. He kicked off three of them after the first patrol. Also, any officer could kick off any enlisted man in his department. I never kicked anybody off. Anyway, the captain kicked off, among others, the engineering officer. Then he came to me and said, “Perce, on the second patrol, I want you to be engineering and diving officer.”

I said, “Captain, I want to admit something to you. In the Naval Academy, I never did understand those courses in engineering. I just didn't get it.”

He said, “You ought to know enough about the Navy not to worry about that. You are going to be in charge of the engines and the batteries. If something goes wrong, the chief machinist mate will tell you. You come tell me. Then I'll tell you what to tell him.”

This system worked out fine. Although I don't think I did any great job as the engineering officer, for some reason or other--I never quite understood why--I developed a very strong talent as diving officer. The diving officer's job was to keep the submarine in trim at all times. If you had to make a quick submerged attack, you didn't want to go down and rock back and forth or up or down. You had to be in perfect trim. I devised a formula of my own by figuring out how much fuel we used, how much salt water took the place of the fuel, and the status of the sanitation tank, as well as this and that and the other. I would make changes every four hours, either pumping from forward trim to aft trim or blowing water out. It seemed to work.

Now, let's go back to the third patrol in the Yellow Sea. The Yellow Sea was the last place in the world you wanted to patrol. It was much calmer than Lake Pontchartrain. The last thing you want is calm water when you're in a submarine. The second thing, the water was only ninety feet deep. Our subs could go four hundred feet. We knew it was a tough deal.

Sure enough, one bright day we were submerged. Actually, we spent pretty much the whole time submerged. The Yellow Sea is between Korea and China, and is an inland sea. We spotted a vessel. The captain saw it on the periscope. My memory is gone, but I think he called it a Q-boat. Whatever it was, it was a vessel that the Japanese had that was most feared by the submarines. It's only duty and task was to kill a submarine. It had the best electronic equipment the Japanese had developed. It had depth charges and everything. There it was in the same vicinity as us.

Fortunately, I had our boat in excellent trim. The main part of my job was on a submerged attack when I was in control of the dive. I had a man to handle the bow plane, the stern plane, the auxiliary man to pump out, and the chief to blow water out. We were in perfect trim. We started in on this guy, dead slow. For the first time in the two patrols when I'd been diving officer, the captain gave his orders, not sixty-two feet, but sixty-two feet six inches. We got on sixty. Our submarines had two periscopes. One was the attack periscope, which is much smaller; so of course we had the little attack periscope up. The captain wanted as little of that periscope showing as possible. We headed in fine. We held right on that sixty-two feet six inches, dead slow. Of course, that is what we called silent running. No one could talk. The air conditioning was off. Everything was quiet. I'm guessing that we came as close as about three thousand yards. As I recall,

the captain was going to fire at maybe fifteen hundred yards. This Q-boat was dead in the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

It hadn't spotted you?

Billups P. Percy:

It wasn't anchored, but it was there just sounding. It was a perfect target, because the angle on the bow was ninety degrees. We were heading into it, so we couldn't miss it. We got closer to about--I may be dramatizing it--let's say two thousand yards. Let's say the captain was going to fire. We couldn't have possibly missed. Instead, the captain said, “Down scope. The Q-boat is under way.” I felt worse then than I did in the PT boats where we ran aground. We knew that was it.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like he would have tried to get a torpedo off before. . . .

Billups P. Percy:

Well, I may have gotten the sequences a little wrong, because he was just getting ready to fire. But for reasons that don't come back immediately to me, he couldn't. The Q-boat was underway. What we did then was we went as deep as we could--I think about ninety or a hundred feet dead slow. At some point here--and again this was a long time ago--I'm not clear whether he saw this through the periscope . . . I think maybe not, maybe it was through our sonar equipment, but this guy was underway and he was heading in the other direction. It appeared that his tour of duty was up. He had not spotted us at all. Then the captain sent us up. By then, the guy had gone out of sight.

We completed our patrol. We had already sunk several ships on this patrol and just couldn't believe that we had gotten out of there alive. You didn't want to meet a Q-boat if that's what they call them. The other interesting thing was that we were to go to Midway. Our third patrol was over. We left the Yellow Sea and came around the southern toe of Japan early in August. We were not very far from Hiroshima or

Nagasaki. It's very possible the bombs were dropped while we were in the vicinity, because either the day we had passed Japan headed to Midway or the next day, we got word of the atomic bombs being dropped. We knew we had been awfully close to those sites. We came actually at one point within a mile of Japan.

I never saw such jubilation in my life as I did in the case of the news of the atomic bombs. Some people today don't quite understand. It's true a lot of Japanese civilians were killed, but the critics didn't spend World War II in the Solomon Islands or out on a submarine. There was no way to describe our feelings.

We headed back to Midway. It was all over. I think the war was over before we got to Midway. I must confess there was a tiny twinge of discontent because I was looking forward to the fourth patrol. We had already been told that, on the fourth patrol, we would patrol the Sea of Japan between Japan and China. We knew it was very tough to get in there and to get out. However, once you get in, they were sitting ducks.

We got back to Pearl and then came back to the States. The war was over. Very briefly, we went to Key West for awhile and then we left Key West. We took a short pleasure trip around South America. Then we went to Jamaica. It was just a fun trip before we finally went to where we were stationed in Panama. I spent about a year on the sub in Panama. We were stationed at Balboa, near Panama City. All I can remember from there is that from Monday morning to Thursday afternoon, we worked. We went out to practice day and night. On Thursday, we would come in. On Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, I played golf at the Panama Country Club, which I had joined. I got to know some ladies and was just having a good time.

I said to myself, “The game is over.” I talked to the captain about it. I said, “Captain, I don't want to be an admiral. I loved every minute on this boat. But it's my understanding that I will not be allowed to stay on a submarine much longer.” That was a rumor then that they were going to send me to surface ships. Frankly, to me, it was like a football game. You win it, and then you go out and practice some more. He said some very flattering things to me, which I'll never forget. I remember when I resigned, he drove me to Colon where I got on the plane. He walked me out to the plane and shook my hand. I was flown to Jacksonville where my resignation took place in February of 1947.

I went into the Reserves briefly. In the Reserves, you could have a summer cruise. I wanted to get on a submarine one more time. I took a summer cruise off Key West. The submarine almost blew up from a battery fire. That was enough of that, so I got out of the Reserves. Apparently, I am now a commander in the U.S. Naval Reserves, retired. I don't get a pension or anything. I didn't think that was right.

I had a mixed career in the Navy. I got a Bronze Star in submarines. I remember one time that the captain took me aside during a patrol. I don't remember which patrol. It was either the second or the third. The way it worked with a submarine was that there was a quota system, depending on what you did on that patrol. First, if you sank enough vessels of a certain type, everybody got a Combat Insignia. We had the Submarine Combat Insignia with two stars representing the three patrols. Also, depending on what you sank, the captain would get something. Then he would be allowed to recommend so many others. For this particular patrol, he got the Navy Cross. He was allowed to recommend so many Silver Stars and so many Bronze Stars. He said, “Perce, I'd be

delighted to recommend you for a Silver Star, but I know you already have one. Although the Bronze Star ranks beneath the Silver Star, you can have it for your uniform. You should have a Bronze Star.” I was very flattered. I knew what he was, in fact, saying--in a way only he could say it--was that if he gave me a Bronze Star, he could give somebody else a Silver Star.

I said, “Sure, that's fine.” I got the Bronze Star. As I said, I talked to Stimmy's wife about a year ago. I'm afraid Stimmy, the captain, is no longer with us.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you go into after you left the Navy?

Billups P. Percy:

After leaving the Navy, I went back to Greenville, Mississippi, and stayed with my brother, LeRoy, his wife, Sarah, and their children. During that time, I had saved up a good bit of money. I hadn't spent a dime. The money had just been put in the bank. The first thing I did was buy a Cadillac convertible from the Greenville dealer. I was free. I wasn't worried then about what I was going to do. I just wanted to have some fun and to see the Grand Canyon. I hopped into that beautiful Cadillac and drove out to the Grand Canyon. It was one of the biggest thrills I've ever had. I went all by myself, usually with the top down. I left the Grand Canyon and said, “I might as well go home and figure out what the hell to do. But while I'm here, I think I'll go by this place called Las Vegas."

I had done some light gambling before, mainly racehorses. I wanted to see what Las Vegas was like. I went to Vegas and stayed at this crummy hotel in town. I gambled a little bit that night. Then I said, "I'm going home." I had won a little. I went to the clerk to check out. I said, “Look, is this it?”

He said, “Well, there is a place they call the Strip. It's on the way from Vegas to L.A.” He showed me how to get there and said, “They got some hotels out there that they say are pretty nice.”

I said, “O.K. I'll give it a try.”

I found my way out there. As I recall, it was a two-lane, potholed, asphalt road in this dreary desert. On the right, there were two hotels I remember. I think they were called the Flamingo and the Last Frontier. Then on the left, there was one hotel called the Desert Inn. That looked nicer. I stayed at the Desert Inn for three days. I gambled day and night and won a considerable amount of money. I won't say how much because I don't remember how much, but I remember I won, mainly playing blackjack. In the Desert Inn, you would sit at the table and they would bring you food, drinks, or whatever you wanted. After three days, I was tired. I said, "It's time to go home." I went out to get into the car to drive back.

Next to the Desert Inn, I noticed there was a Quonset hut, you know, the temporary army type. It was divided into two sections. One half of it was a souvenir shop. I went in there. There wasn't anything but T-shirts. On the other side--it was hard to tell from the outside--it was a real estate office. I went in, and there was one lady in there. She had a lot of maps out. I looked at these maps. She said, “Can I be of any help?”

I said, “Just let me look around.” After studying these maps, I saw exactly where L.A. was and everything. I said, “Miss?” She gave me her name. Since I was feeling pretty flush with my money I had saved during the war, I asked, “What do you think it

would cost for me to buy a lot, let's say, next to the Desert Inn towards L.A., that is a thousand feet by five hundred feet deep?”

Then she said, “Oh my God, you're talking about fifty thousand square feet.” She said, “That would probably run you close to fifty thousand dollars.” Well, my brother was the chairman of the bank in Greenville, and I knew that I could raise fifty thousand dollars.

I said, “Let me go outside.” I went outside and looked around it. All I remember was the tumbleweed and a pockmarked road. I don't like deserts much anyway and this was the ugliest desert I'd ever seen. I said, “Oh, forget it.” I thanked her and went home.

Well, I've asked people, “What do you think that lot would be worth today?” I've heard figures from twenty million to a hundred million. If you've ever seen photos of the Strip, you know that the Desert Inn is right there. The bright spot is, if I had bought a lot, my compatriots would have been Wilber Clarke, who owned the Desert Inn and was Mafioso; Bugsy Segal, who owned the Flamingo and was also Mafioso; and, I think, Meyer Lansky, who owned the other one. That was the only way I could console myself. I do think about that occasionally. My wife and I have been out there a couple of times and had a good time at the Desert Inn. We haven't been out there in a long time. I think the area has gone to pot out there, but it was interesting. Anyway, I came back home and had to make a decision.

At that time, my brother, Walker, had finished his TB treatment and had gotten married in New Orleans in late 1946. He had moved up to Sewanee, Tennessee, where my Uncle Will had a summer place called Brinkwood near the University of the South. It was a lovely place right on the brink of a mountain. Walker and his wife, Bunt, were

staying there. I went up to visit them and ended up staying the entire summer. I went to summer school to supplement the education I had received at the Naval Academy. I liked Sewanee so much that I decided to stay for a year.

When Walker and Bunt left, I moved into town with a good friend of mine and went for the whole year taking the courses I had not had at Annapolis: Philosophy, English Literature, History, and those things. They had been cut out of my three-year course. I had a wonderful time and made some good friends. I didn't get a degree because I wasn't after a degree. Three friends and I then went to Europe. We stayed in Europe from June to December and came back around Christmas. This would be December of 1948. Having had a wonderful time all over Europe, Africa, and England, in 1949 I figured it was time to figure out what to do. I had spent a good deal of money in Europe.

After a lot of thinking back and forth, especially about the fact that my Uncle Will had been a lawyer, my father had been a lawyer, his father and grandfather had been lawyers, and the fact I had always heard that law school was a no-lose game, I decided to go to law school. If I didn't like law school, I could get out. If I did like it, it would equip me to do anything. I didn't know which one to go to. I wrote a great friend of Uncle Will's named Huger Jervey, who had been the acting dean, I think, at Columbia Law School in New York. I wrote him to ask for some advice. I wish I had saved his letter because he said, “Of course Columbia is the best law school, but Harvard and Yale are adequate.” I knew him quite well. I visited him in New York where he lived. He said, “Knowing your disposition, I think the competition in Columbia you'll find displeasing, not that you couldn't cope with it. But these people would largely deal with

commercial law. With these people, you are going to have to study day and night. At your age and experience, I'm not sure that's the place for you to go. I would recommend you go to Charlottesville, Virginia, to the University of Virginia. It's a very fine law school and I think you'll enjoy it."

I applied to the University of Virginia and was accepted. I went up there not knowing a soul. I had three glorious years there, both educationally and socially. I made Law Review and Order of the Coif, which is like Phi Beta Kappa. I had a very successful career in Virginia. My friends, who had done well in law school and some were Law Review as well, I noticed were all going to New York and Washington for these big jobs. Well, there was only one thing I wanted to do. They were all stunned by it. I handled it very poorly. I wanted to get into the CIA. I was a cold warrior and wanted to go back to war, against Russia.

I applied to the CIA. Unfortunately, a lot of people knew I had applied to the CIA. It took the CIA four months to check me out. What you give them is twenty references. What I found out later is that they check out the twenty references really more than they check you out. After four months, I was accepted. That was almost the end of 1952. I guess about November, I went to Washington and got a place to stay. I signed up with the CIA at that point. I was with the CIA for maybe some six months. There are two things I'll point out. One, I was with the best part of the CIA, the top part, in Washington. It was called OCI, the Office of Current Intelligence. Our job was to analyze reports from overseas agents and to prepare reports for the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower. OCI was to place by his bedside every morning at

seven thirty a two-page, double-spaced, typed report of everything he should know as President of the United States.

I loved the work, and we worked very hard. I was at the North African desk. I was the only member of the North African desk who didn't have a Ph.D. The lady who ran it was one of the smartest people I've ever seen. We didn't have a clock. We came in early and left late. Meanwhile, the most important event in my life had occurred. While waiting to hear from the CIA, I'd gone to the World Series in New York City. I love baseball. This was in November of 1952. There I met the young lady I was to marry. A friend had told me about her and called her up. She lived in New York City. He told her I was coming. We met. I dated her some while I was in Washington.

I went to the head of the OCI and said, “I've never been with people like this, but I really want to be an overseas agent. I want to be a spy.” I resigned after his response: "In short it will take at least ten years to build up a cover.” Interestingly, he thought of sending me to Saigon--because I knew some French--to Beirut--these are names that became very familiar--or even to Taiwan to help train them in PT boats. This sounds overdramatic, but I spent most of the night--it was a pretty night--by the Lincoln Memorial. The CIA then was not in Langley, but was a bunch of Quonset huts by the lagoon at the Lincoln Memorial. So, I went and sat at the Lincoln Memorial, which is one of my favorite structures in the world, along with the Jefferson Memorial. I think what turned my thinking was having met the lady I wanted to marry. I resigned from the CIA, the Company as we call it, in the middle of 1953. Then I married Jaye, my wife, on August 13, 1953.

We went on our honeymoon. It lasted for four months until December. We went all over Europe. We had a glorious, glorious time. We came back, and she found out she was pregnant. We didn't know where we were going to live. We made a compromise. She was born and bred in New York City. Therefore, we would live in a city. My half of it was make it a southern city. Once you think of a southern city, it doesn't take you very long to decide on New Orleans as a possibility.

After we got back to New York from Europe, we spent a week in Greenville, as I recall, with LeRoy and Sarah. Then we headed down to Covington, Louisiana, where my brother Walker and his wife Bunt lived. Covington is a little town north of Lake Pontchartrain. New Orleans is south of Lake Pontchartrain. This was, I think, in December of 1953. We planned to stay a week. Walker and Bunt lived about three miles out of town on a country road. They had a little guest house. Instead of staying a week, we stayed a month, during which time we made several trips to New Orleans. At the end of that month, we decided we would go to New Orleans. I think it was January 1, 1954, that we moved to New Orleans. We rented an apartment we found out about on Audubon Park. Oddly enough, it was right across the street from Tulane University.

All I can remember for the next few years was having a glorious time. We had our first child in May of 1954. We had our next child during the next year. We just had a good time. We spent a lot of time in the French Quarter, when the French Quarter was great.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you open an independent practice or join a law firm?

Billups P. Percy:

No, I still had some money. I had decided that I wanted us to enjoy ourselves. They had this wonderful music down in the French Quarter. It wasn't gaudy or dirty like

it is today. It was marvelous. We'd eat at Gallatoire's or Antoine's. Finally, I had to get down to work. I was thirty-two years old. I checked into what I had to do to practice law in Louisiana. I found out that to become a member of the bar I either had to take the bar exam or go to an accredited Louisiana law school and take a year in what is called Code courses. These were courses in the Napoleonic Code. I didn't want to take the bar exam. There I was right there at Tulane, so I signed up at Tulane for a year. I took the Code courses and enjoyed it. I didn't do that well, but I didn't care. All I had to do was pass. I wasn't going after a degree. They gave me another JD degree, I guess, or LLB, whatever they called it then. I got out of Tulane after a year and was admitted to the bar.

After law school, I was delighted to be invited by a Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court to be a law clerk, which is the best year you could spend after being in law school. I went with Justice E. Howard McCaleb of the Supreme Court of Louisiana, which was in New Orleans. I clerked with Justice McCaleb for a year and enjoyed it very, very much. I learned a great deal.

After that, I had a job in what was considered one of the best law firms in town: Chaffe, McCall, Phillips, Toler & Sarpy. It was known to everybody as Chaffe, McCall. They had about twenty-five or thirty lawyers. I practiced for two years doing mostly maritime law. They figured it was best since I had been in Annapolis and they had a pretty good admiralty practice since New Orleans is a port. After two years, I had had enough. The senior partner then was Mr. Nat Phillips. I thought about it a good bit and I went in with my mind made up. I said, “Mr. Phillips, can I talk to you?”

He said, “Yes, sit down.”

I said, “I've decided to resign.” He said some very flattering things, which led me to believe that I was in line for a partnership not too far off.

He said, “Would you mind telling me why?”

I said, “No, sir. First thing I want to say is that this is the finest group of people I've ever worked with. I would like to do anything with them except practice law.”

He said, “What's wrong with practicing law?” I must say I had prepared this line before I went in.

I said, “Mr. Phillips, I thought when I entered the legal area that I was entering a profession. I have found out after two years that it's just a business.”

He leaned back, took off his glasses and said, “You're exactly right.” Of course, what I had meant by that is that for two years I don't ever remember opening up a law book. I was on the phone negotiating settlements with people who represented injured seamen, since we represented maritime insurance companies. We were defense lawyers. I love the law and that's what I grew to love in Virginia. I left Chaffe, McCall.

The next two or three years are kind of hazy for me because I don't remember what I did. I got in some venture involving seafood or something. I wasn't earning any money. It became obvious that I needed to get a job. I wasn't quite sure what I wanted to do, but I had to do something. By great good fortune, you know life is full of incidents that just happen and things would be so different if a particular incident hadn't happened. During the year I spent at Tulane Law School, I became friends with the dean, Ray Forrester. We, my wife and I, were down in Jamaica. I forget whether our children were with us or not. I got a phone call from Dean Ray Forrester asking if I would be interested

in being on the faculty at Tulane. I thought that was very flattering. We came back from Jamaica, and I went up to talk to Ray. I said, “Yes.”

He said, “Look, I can't get you in myself. You have to be approved.” He was always straight to the point. “You've got to be approved by a committee.” I met with the committee and had lunch with them. I was approved. Ray called me up, congratulated me, and asked me to come by the law school. I guess this was 1962, maybe early 1963. I don't remember exactly when. He congratulated me. Just like normal, he got to the point. He said, “Now I don't know what you'll be teaching. That will be developed. Here is how much you'll make. I want to make sure you understand this because I've found a lot of professors know more about law than they know about mathematics.”

I said, “I think you're right.” He showed me and it seemed decent to me, although I don't think it was as much as I was making as a lawyer.

Anyway, I signed on and began teaching in September 1963. I taught at Tulane Law School for twenty-three years. In terms of what I taught, the thing I wanted to teach most was Constitutional Law, but Ray Forrester taught that. What happened was, right after I got signed on, he left and became the dean of Cornell. I've kidded him about this. Therefore, I got to teach the Constitutional Law class. I succeeded him. I taught maritime law, admirality law, insurance law, and other things. I taught Constitutional Law for twenty-three years. I enjoyed every minute of it. I even had seminars in Constitutional Law.

In 1986, I was sixty-four. I could have taught until I was seventy, but I felt the time had come to retire. I think the main reason was that the dean, Paul Verkuil, was leaving. I had been chairman of the search committee that landed him. We got Verkuil,