| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

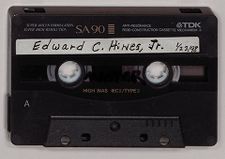

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #164 | |

| Commander Edward C. Hines, Jr. | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| January 23, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Commander Hines, begin with your early background. I think you were born on 16 July 1917 in North Carolina. If you will, provide us with a little more of your background and childhood, and what led you to the Naval Academy.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I first saw light at 1010 Market Street in Wilmington, North Carolina. Not many years after that, maybe two or three, we moved to Carolina Heights (208 North 17th Street) in Wilmington. That is where I spent the rest of my youth. I got the idea to go to the Naval Academy while I was in high school. I consulted my cousin around the corner, who had been a lieutenant in World War I--a navigator on a destroyer. He put me on to his friend, Sam Sweeny, who ran the local Naval Reserve unit. It ended up with me signing up with that Reserve unit and going to the Reserve drills. My education needed augmentation, being from a southern high school; so I went to Randles School in Washington, DC. It specialized in preparing students to pass the Naval Academy Entrance Exams.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, actually at New Hanover High School, you were probably a foot up above a lot of southern schools at that time, were you not? Was New Hanover High a pretty good school during the 1930s?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Academically, no.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No. I could go into detail, but I think that is a side issue.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right. I understand.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I spent two years at Randles, and then I went to the Naval Academy in 1937. The war was brewing in Europe at the time. The authorities saw fit to speed up the graduation of our class of 1941 from June to February of 1941. By March of 1941, I was aboard ship in the USS COLE (DD-155). This ship unexpectedly set a world record for ship speed of forty-one knots in 1917, and this record stood until World War II.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about your experiences at the Academy? Anything in particular there that stands out in your recollections, as far as good, bad, or indifferent? The social life, the academics, or the harassment from upper classmen your Plebe year or other things of that nature.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

As a Plebe, I remember three of us would go around to the second classmen, baiting them to ask us where we were from, which was a conventional question. We would reply in sequence, “Wilmington. Wilmington. Wilmington.” The upper classmen would make some comment and then they would say, “What state?” and we would say, “North Carolina, Ohio, and California.” Hazing didn't particularly bother me. I did a lot of push-ups, which was a standard exercise for Plebes in those days. May still be, I don't know.

I was pretty good in math when I went to Randles. In fact, the first time the Academy established a relative standing of us, I was in the upper twenty-five of mathematics and managed to ride that wave for about a year. Meanwhile, I was having trouble with the famous dago, which for me was Spanish. I seemed to be in a group that had many who lived in Texas or Mexico, who were familiar with Spanish, and I was not. I barely made the requisite 2.5 g.p.a. for two years. Also, I made graduation standing about 395 out of 398. This was the smallest class that had graduated in many years.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do any sailing on the Chesapeake or were you involved in any of the athletics outside the Academy?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I was into football until I injured my knee. I had to quit that. I got into wrestling when my knee got well enough to do something with it. I turned out to be the most appropriate fodder for the Academy's best lightweight wrestler. He could pin everybody but me, but I couldn't pin him. He used me as a wrestling partner a good bit of the time. I also got into gymnastics to the extent of preparing myself to perform on the side horse for battalion competition. I did try cross-country once, but I soon tired of watching people's backs.

On board the COLE, I started out with very ordinary jobs, like mess treasurer and supply officer, since we had no supply officer aboard. When the executive officer was transferred, the next senior officer was a junior grade lieutenant, who had been to the Naval Academy, but didn't graduate. He had missed out on navigation. The captain made him the executive officer and made me the navigator.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, where was the COLE operating out of at this time?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

It was the East Coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

At Key West?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I joined it in Norfolk. Then we promptly went to Rhode Island. From Rhode Island, we went to Argentia, Newfoundland. We escorted convoys back and forth across the Atlantic. We did that for many months, with occasional stops in Boston and Iceland.

Donald R. Lennon:

Pretty cold up there, wasn't it?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Very cold, but not as cold as the walk in the Navy Yard in Boston getting to the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you run into any torpedoes or have any of the merchant vessels torpedoed in the convoys you ran?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No ship that we were with was ever hit. We were of a lucky charm in that respect. At one point, we were ordered to escort the USS ELECTRA, a cargo ship. We had to join it off northwest Africa. We spotted the ELECTRA on the horizon. About the time we spotted it, we saw a plume go up from the ship, which was the unmistakable sign of a ship being hit by a torpedo. We were already headed for it at full speed. We continued. As we approached and exchanged signals with them, we found out they were frantic to get the crew off the ship.

We did take people off by boats and thereby found the reason they were panicking. The ship was loaded with ammunition in all holds except one, which had these metal panels for making landing strips for aircraft on rough terrain. That is where the torpedo hit--where the landing mats were. After they finally decided that the ship was not going to blow up, we were able to put the refugees back on board.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it wasn't hit bad enough to sink it, obviously?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No, just at that one compartment.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow!

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

You could see where the reason for their concern came from. That was a sidelight of the North African invasion, which they had selected COLE to participate in. In order to prepare for that, they put us in the Navy yard and took the radar antennas off the mast and cut the mast down level with the flying bridge. They also took off other material of a classified nature and sent us out to Bermuda for some further preparations for the ship to be expendable.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why would they cut down the mast and everything?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

They were doing the mast for minimum profile because, as it turned out, we were to go into the harbor at Safi in French Morocco under the cover of darkness. We were to carry two hundred Army troops. The troops' job was to capture the gun positions ashore in advance of the main landing boats coming in with the troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is in 1942?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

This was in November of 1942.

They didn't know whether or not the French were going to put up a resistance. We had to be prepared, and we were told that if we had any opposition, we were to run our bow up on the beach, and let the troops climb down a cargo net onto the beach. The unmistakable message was that the troops had to get ashore and it didn't make a lot of difference if the ship suffered damage or was lost!

Donald R. Lennon:

You had to sacrifice the ship?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No. We did get the troops successfully ashore by going alongside the dock. We stayed there for two or three days. The only damage we received from the firing that went on for a while was a fifty-caliber hole through one of the smokestacks. After Safi,

we went up to Casablanca for a brief visit. Then we went into the Mediterranean and to Mostaganem on the Arzew Gulf.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the purpose of the visits to the ports?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I think we were being located closest to the most likely need for an escort.

They were planning an invasion of Sicily next. We were to do a similar thing there. It turned out that in Sicily we were using an infrared beacon up on the short mast we had. We were to go into Sicily at Gela Bay and take a predetermined position as a temporary “lighthouse.” We were to use this infrared beacon in the pre-dawn when the attackships were entering the bay.

An interesting sidelight was that there was a searchlight on the beach, which about every half-hour would come on and sweep through the bay to check to see whether anything was out there. We were anticipating that they might pick us up in the light beam, but they never seemed to notice that one little ship out there. We must have survived seven or eight sweeps of that searchlight before the many ships of the attack force came into the harbor, using us as their “lighthouse.” The searchlight swept while the ships were coming in. It swept through a few ships; then it switched back a few ships. The light swept to the right and then swept back and forth. Finally it swung around and went out. You can only imagine what was going on ashore when they saw all those ships out there. The next operation was probably preceded by some time in the North African ports of Oran, Algiers, and Mostaganem.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the invasion of Sicily came off without a hitch at all? From your perspective on the COLE?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Right. No shots were even fired. The next one was the invasion of Italy at Salerno. We did the infrared beacon job there also. Our experience was that no shots were fired. The landing was made successfully. We faded back into an antisubmarine patrol outside of the troop ships that had carried the attack landing troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, at Sicily and Salerno both, your purpose was just to case out the harbor and to serve as the beacon for the transports to come in on.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Not exactly case out the harbor. We were to determine our position and try to put the ship into the position that had been predetermined for us to be in. When the other ships entered the bay, they could use us as a “lighthouse” and knew our position. From that, they could determine and adjust their own position relative to the land.

While we were patrolling off the troop ships, we spotted a small life raft in the water. We determined through the binoculars that it was probably an aviator's life raft. It was not as big as a ship's life raft. There was somebody in it. We decided that from what we saw (olive skin), it was probably an Italian aviator who had been shot down and was in his life raft. We knew we were not supposed to go alongside the life raft; it might be sabotage. It might be bait for us, waiting to blow us up. So we put a boat in the water and put our best Italian speakers in it. We sent them out to pick up this supposed aviator. He was brought back to the ship and climbed aboard silently without assistance. The doctor was there to meet him and promptly took him down below to sickbay. Not very long after, the doctor came up to the bridge and told the captain and myself that the aviator was in good shape, but that he wasn't really Italian. He was a black American from our 99th Fighter Squadron. He thought he was coming to an Italian destroyer, with all that Italian he heard from the Italian speakers we put in the boat.

After 3½ years in the COLE, I came back to the States and went to the Fire Control School in Washington, DC. I found out they were going to order me as executive officer of a new destroyer. I petitioned that I be sent as gunnery officer instead, because I had never been aboard a new destroyer. They agreed, and that is why they were sending me to this fire control school in Washington. The Fire Control School instructors would tell you that in some situations if you reach this certain point, you ask the gunnery officer. I would say, “I am going to be the gunnery officer. How do I resolve that problem?” They didn't know!

I made the inquiry to the personnel detailer, “What do I do?” He said, “We are going to send you to Hawaii to the Gunnery Officer's School.” I was so ordered to Camp Catlin to the Gunnery Officer's School. They also threw in the CIC school. While I was at the school, they ordered me as an executive. I walked aboard the USS ALLEN M. SUMNER (DD-692) and became the executive officer. The SUMNER was assigned to Fast Carrier Task Force operations in the Pacific.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, was this 1943 or 1944?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

This was late 1944. We did a lot of plane guard duty for carriers launching aircraft. While so operating, the tour of duty for the skipper was up. A new captain was transferred aboard by highline from the carrier.

A few days later, the new captain had relieved the former one, who was to go to duty elsewhere, I don't remember where. I told the new captain, who I found had been at a desk job for four years, that the former captain had divided up the conning of the ship in going alongside--so that one of us took the speed and the other one took the course

corrections. If he would be willing, I would like to continue that. It was good experience for me. He said, “No, no he would do it.”

So, when we were ordered alongside to transfer the former captain, the new one did the conventional twenty-five knots to start with. The carrier was doing twelve and a half or fifteen. We reached the point where we should take off some of that speed, but it is arbitrary because whether you slow it by five knots or whether you wait and slow it by ten knots; it is what you feel. So I didn't say anything. We got to the point where we should really be slowing down drastically, and he wasn't doing anything, so I pointed out that we had a lot of speed over that carrier that we had to go alongside. I told him we better drop some of ours or we would run right by it. Again, he didn't do anything.

Finally, it got to the point where our bow was even with the stern of the carrier. I pointed out again to him that we had tremendous speed advantage. We had to do something radical right now. He said, “You take the speed.” I am sure no one knows what to do at that point. Obviously, he didn't. I said, “All stop. All back full.” The ship convulsed with the sudden change of thrust. Its slowing down was not particularly perceptible yet. We got to the proper position for us to handle a transfer. I still had back full on, but we had just about matched the speed of the ship. I said, “All stop. All ahead standard. Make turns for whatever the speed was at that time, fifteen or twelve.” We ended up like we had parked there. We were very fortunate, since it was completely accidental. I am sure that we were the subject of much conversation aboard the carrier because we charged in and stopped virtually alongside.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were flying in.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

The advantage of that experience was that the captain agreed that I should do the speed or the course corrections and he should do the other from then on. We visited a number of Pacific islands and atolls in that tour of duty. I actually spent only fifteen months in the Pacific Ocean, but I crossed it six times during those months.

We were support for the landings at Leyte in the Philippines. While there, the Japanese still had the western side of Leyte Island, while the U.S. had a beachhead on the east side. There was intelligence from aircraft that the Japanese were sending a replenishment convoy to Ormoc Bay on the west side of the island. The orders for my division of four destroyers were to go south around the end of the island, west under it and north up the west side to Ormoc Bay. We were to try to intercept this convoy that was to resupply the west side and destroy it.

When that mission began, we had sailed to about due south of the island when the Japanese planes spotted us and started attacking us. This heckling continued for the next several hours. We ended up shooting down seven of the aircraft. As we approached the harbor which the convoy would have resupplied, we lost one of the destroyers, as it was torpedoed by an undetected Japanese submarine. We found out that the convoy ships had already sailed into the harbor to resupply it. So our division had a gunnery exercise, shooting at the ships in the harbor alongside the dock. We also shot and sank a Jap destroyer, which was in the harbor. We never did find the submarine that sank our destroyer, the USS COOPER.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now the Japanese aircraft, this was before the days of kamikazes, so what were they doing, trying to bomb you?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

This was not before kamikazes, but these were not kamikaze aircraft. These were likely all zeros. After this operation at Leyte, we were ordered through the islands up to Lingayen Gulf, which is north of Manila. We were in the Lingayen Gulf preparing in that area for another landing, when a kamikaze hit us. We had about seventeen killed and about twenty-seven wounded. We were temporarily detached.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you at the time the kamikaze hit?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Personally, I was on the bridge. We were doing twenty-five knots and fishtailing around this gulf. Since I was the navigator as well as the executive, I had to be sure we were in “safe waters.” I was trying to get a position to be sure where we were. I went out on the bridge to take a bearing and I caught, out of the top of my eye, something and looked up. Here is a Japanese Zero coming straight at us with little white flames coming out of each wing. He was firing at us. I figured a dead navigator wasn't worth much, so I ducked out of the line of fire. I tried to get into the pilothouse where everybody else had already retreated. I had to get in there on top of somebody to get in.

This plane came in, caught one wing on our signal halliards, and caught his other wing on the forward smokestack. This spun him around. He hit back aft of there, and it turned out that he was carrying a twelve-inch projectile inside the plane as a bomb. The Japanese at that time had evidently run out of bombs. The projectile went into the living compartment through the main deck and exploded. It pretty well took care of that living compartment. Also, it weakened the support structure for our after gun mount, which we continued to use. This mount continued to settle a bit each time we used it. The result of the settling was that they decided that we had to go somewhere and get fixed up temporarily.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, it didn't disable the ship?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No. It did not disable the ship. They sent us to Manus in the Admiralty Islands where there was a floating dry dock. They patched us up so we could sail across the Pacific back to San Francisco to get permanent repairs. Once the permanent repairs were done, we went back out to the western Pacific. We were in Tokyo Bay when the surrender was signed. We also rode out a typhoon in Tokyo Bay. Very shortly thereafter, since peace was now upon us, we were ordered to Longview, Washington, for Navy Day. This was the first visit of Navy ships to United States ports since before the war. It turned out that the Longview people were very gracious and cordial to us. I tried to but a lot there but the owner would not sell.

As you go up the western side of Leyte Island, there is an island named Bohol to port. The waters from Leyte to Bohol are not as deep as other parts. They are actually mineable. We did not know whether they might be mined or not. Very close to Leyte itself was a small island. There was a channel between that island and Leyte. I recommended to the captain that we go through there, instead of going across this mineable shallowness. We did that while making thirty knots and found that there were all sorts of fishing boats there. I am sure several of them were swamped by our wash because we did not slow down.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the planes that were harassing you, were they bombing you or firing at you? Exactly what were they, the Japanese planes, doing? Obviously, the destroyer the guy hit was from the torpedo from the submarine. I was wondering, what was the nature of the attack by the planes?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

As I remember it, they were using machines guns. We were firing at the planes anytime they were in range, so discouraging any close approaches. I only remember one bomb. It hit not very far off our starboard bow. The bomb exploded on hitting the water. You could hear lots of pieces of shrapnel hitting the ship. Some shrapnel hit a storage tank of a gas that flames when it hits the atmosphere. I usually know the name of the gas, but I can't think of it right now. Anyhow, this tank's cover and neck had been hit by a piece of shrapnel. The storage tank was now sitting there like a torch--burning. This burning tank made us an easy target for these planes. We had to get rid of that tank right away. So we just threw it over the side.

When we got back to the eastern side of Leyte the next day, we discovered that we had seventy-two holes in the starboard side. The holes were all little ones. However, they were all shining lights from inside the ship out onto the water. We didn't know these holes were shining during the night. How much it was useful to the planes, we don't really know.

There were four destroyers, so the planes were trying to duck all these shells that were being fired at them. They didn't have much of an opportunity to find a good position for dropping bombs. We shot down seven of the aircraft and the other ships shot down planes as well. I don't know what the total shot down ended up being.

Donald R. Lennon:

But they did suffer considerable losses.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

We suffered the loss of one destroyer. The ship went down so fast that there were very few people that survived it. Our division commander, was faced with the decision of whether we should stop and pick up survivors or not. Because a submarine had torpedoed our destroyer and might try to torpedo us, the commodore decided that we

couldn't stop and pick up survivors, especially since our mission was to destroy the shipping in their harbor. The commodore promptly called the amphibious planes that we had doing intelligence searches for us, asked them to land on the water, and pick up survivors. We gave them the position. I don't know whether they successfully retrieved many people or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like they would have been more vulnerable than a destroyer would have been to being destroyed.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

The planes?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, sir. Coming in and landing to pick up survivors. It looks like they would have been a perfect target.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

For the planes? The attacking planes were gone by that time, and we were dealing with our attempt to destroy the shipping in the harbor. Amphibious planes, of course, are not subject to damage by torpedo.

Donald R. Lennon:

The concern was of the submarine.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

And the destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, on the kamikaze, what kind of feeling is that to see a plane coming right towards you?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Well, since he was firing guns, it told me to take cover in a hurry. It was unmistakably a Japanese Zero aircraft. We had many sessions of identifying their planes, so we knew the type of plane.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the SUMNER guns were firing back at him, weren't they? They just couldn't hit him.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

There were numerous planes up there. This just happened to be one of them. We didn't know that it was a kamikaze; but shortly after that, we were well aware that it was a kamikaze because several other ships were attacked as well. In fact, the Australian cruiser, CANBERRA, was in there and took a hit on the starboard side, just aft of the bridge. They reported on the radio the number of casualties and the damage they had suffered. About a half hour or an hour later, they reported a second kamikaze hit in the same spot. They reported, “No further damage, no further casualties.”

There was a theory in the United States Navy at that time that the Japanese kamikaze pilots had been trained to crash into the bridge. They were making the same mistake over and over again. They would always just miss it and hit aft of the bridge. Of course, there was never a survivor to correct successors.

Donald R. Lennon:

To tell them what they were doing wrong. You say, you went back for repairs for the SUMNER and then you were in Tokyo Bay at the end of the war.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

We got back to the States after the war. I welcomed the opportunity to fly from San Diego to Wilmington, N.C., to spend some leave. I got to Wilmington, bought myself a used car, and promptly got orders to return to the ship immediately to carry out orders! So I didn't get to use the car. I turned the car over to my father, went back out to San Diego, and found I was to go to command of the USS KEITH (DE-241).

“Well, where is the KEITH?” I asked. They couldn't tell me that. I was to report to the commandant for transportation. The commandant sent me to San Francisco, San Francisco sent me to Pearl Harbor, Pearl Harbor sent me to Guam, and none of them would tell me where I was going. Guam put me on a plane to go to Iwo Jima because that is where the ship was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of a roundabout way.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

So I joined the destroyer escort in Iwo Jima. They were using the DEs for station patrol. There was a term for that, which I can't recall right now. For example, when you were guarding a carrier, you were a “bird dog.” Anyway, while on this patrol, you are not anchored. You are lying to or steaming slowly around in circles to maintain an approximate position. We were supposed to be a checkpoint for military planes flying from the States toward the China coast. On one of those planes that came by while we were stationed out there, I recognized the voice of the pilot as my roommate from the Naval Academy. It turned out that he was sent to Shanghai and to be stationed there.

My ship was eventually ordered to the China coast. I was given command of a task unit consisting of a minelayer and several mine sweepers. Our orders were to resweep, magnetically, the mouth of the Yangtze River, because a Japanese ship repatriating Japanese soldiers had hit a mine out there. The Jap captain had said it was a magnetic mine. Actually, the area had already been magnetically swept, but on the strength of this Japanese captain's story, they had us resweeping it. It was necessary that my ship be the navigation authority for these minesweepers because they were pretty low on the water. The coast of China in that area is like mud flats--no prominent landmarks to navigate by. The Saddle Islands were off the shore there about fifteen miles. These islands are good for navigation, but they were a little too far away from the area we were sweeping for the minesweepers to use them for navigation. We would give the minesweepers course and speed and keep track of their sweeps, so we actually reswept the mouth of the Yangtze River that way. It took a matter of several weeks to do this. The minesweepers could only stay out about five days before they needed replenishment.

My ship, the KEITH, could give them water, but it was a cumbersome process. Ships were not designed to pump water to others. We could give them food, but we didn't have the capacity to carry much for the seven minesweepers we had actively sweeping. We would go into Shanghai and resupply about every four to six days. Then we would go right back out and continue the sweep. This task went on for about two months, I believe, before we had finished the job.

Then the task force was dissolved. About that time, orders were received to return to Charleston, South Carolina, for decommissioning. This was something that had been expected for some time. The orders applied to all the ships in the division that KEITH was in. The other ships were doing mail runs along the China coast. We broke out the navigation charts and figured out what was the best way to get from the east coast of China to Charleston, South Carolina.

There are two options: to go through Panama Canal or the Suez Canal. It turns out, if we went through Panama, it is fifty miles shorter than going through the Suez Canal. So we opted for the Panama. I particularly favored that route because there would be some American repair facilities encountered en route; whereas, the other way, there would be none.

A similar division of destroyer escorts in Hong Kong received the same orders at the same time and went through the same navigation exercise that I did. They found out that the Suez was fifty miles closer for them, so they went around the world the opposite direction. Both divisions ended up in Charleston, South Carolina. There, I turned the ship over to my relief and went to the Postgraduate School at Annapolis for a course in applied communications for a year. During the course of that year, I met and married an

Annapolis schoolteacher. I was ordered from there to the aircraft carrier, LEYTE (CV-32).

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this around 1947 or 1948?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

This was 1947. The LEYTE was stationed in Quonset Point, Rhode Island. It was doing alternate duty with her sister ship, PHILIPPINE SEA, in the Mediterranean. We would go over there for three months and come back. There was always one such ship in the Mediterranean. While we were not in the Mediterranean, we were in Quonset. In Quonset, we received orders to go to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. We spent a month at the Navy Yard. I managed to move my family, which now included a daughter, to Garden City, Long Island for the time we were in the Navy Yard.

An interesting facet of going into the Navy Yard on the carrier was that you had to take off the top section of the mast to pass underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. You also had to unload ammunition and make sure that the highest point on your ship would not strike the Brooklyn Bridge. This called for careful calculations to figure out what we could safely do. We took the top sectional mast down to a platform, which we figured, would clear the bridge by about three to four feet. To check our figuring, we mounted several thin sticks up on that platform. One of them was five feet, one was four feet, one was three feet, and one was two feet. We watched with binoculars as we went under the bridge to see which one broke. We were on target; the four- and three-foot ones broke and the shorter ones didn't.

One interesting episode that occurred while attached to the LEYTE was the PHILIPPINE SEA returning to port before we left to take their place in the Mediterranean. As they usually do, the air group flies off the day before the ship reaches

port because they can't fly off once they are in port. I went to the Quonset Air Field for the arrival of the air group from the PHILIPPINE SEA. There were more planes arriving than the number that could land at the same time, so the planes were circling over the field, awaiting their turns.

Unfortunately, two of the planes touched wings up there over the field. One of them spun out and crashed. Wives and some children were there. Of course, every wife thought that was her husband. There was pandemonium for a while. As a result of this incident, they no longer announced when the air groups were going to fly in, just to avoid that sort of situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

No women and children on hand?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, maybe this question is premature, but at this point, you had been on destroyers, destroyer escorts, and a carrier. Which did you prefer? Which did you really enjoy the most being a part of?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I am what you call a “dyed in the wool” destroyer man. It is big enough and not too small.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have talked to a lot of people who were DE skippers during the war. They tell me that DEs won World War II single-handedly.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Well, the DE that I had contained Fairbanks-Morse reversible engines. They started by using compressed air. You had to keep a tank of compressed air just to start the engines. I had been warned by the chief engineer when I first took over command that you could only start your engines about seven times in an hour before the tanks

would run out of air. Thus, when you were coming into port, you had to measure yourself on how often you stopped and started those engines.

I had come into the port at Shanghai several times, so I was pretty familiar with it. This one time I figured that we were going to be able to go alongside another destroyer without even having to back down. As we were approaching the destroyer, the chief engineer called up and said, “You've got no more air.” Fortunately, we glided alongside, threw lines over, and did not have to back down, which we could not have done if we had had to.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sheldon Kinney is one who just thinks that DEs were the greatest.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I don't know whether he had the same situation or not. Some of them were steam-driven, you know.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes. I know. I didn't mean to go off aside there and interrupt the LEYTE, but I just happened to think of that--the fact that you had been on all three.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

They ordered me from the carrier after a year to assistant district communication officer in the Fifth Naval District, Norfolk, Virginia. I found the captain, who was the district communication officer, and myself were the only two senior officers there. At this time, I was a lieutenant commander. There was one lieutenant and the rest were civilians who ran the communication station--the district headquarters. There were other enlisted men stationed at the transmitter station and the radio receiving station.

I had to visit communication activities within the area of southern Virginia and northern North Carolina to check on the problems with those facilities. I was only in this job for a matter of months before I received orders to Ankara, Turkey.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was this, about 1949?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Yes. So I put the wife and two kids in the four-door Oldsmobile and we drove to New York to the dock. We got aboard the SS MOHAMMED ALI EL-KEBIR, an Egyptian mail line ship, which carried cargo and about a dozen passengers at the most. My car was put on the same ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were able to carry your family with you.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Right. There was a Navy captain and his wife aboard that ship, along with several Turkish Army officers, who had been to school in the States and were returning to Turkey. This was a good chance for us, the captain, our wives, and myself to pick up some Turkish. So we got to Turkey with some knowledge of Turkish. At that time, there was no bridge across Bosphorus. We went into Istanbul and anchored. We were sent ashore by boat, then by ferry across the Bosphorus, and finally, up by train to Ankara.

We lived in the capital city in a house that had been occupied by the Dutch Legation. It was an unusually nicely built house. Most importantly, we enjoyed the perks that the Legation received in terms of water supply. It was habitual for most people in Ankara to be without water during the daytime in the summer because of the scarcity of water. Legations did not have that restriction; they had water all the time. The chief of staff lived a block away. He found out that I had water when he didn't, so he complained to the Turks about this lieutenant commander having water when he didn't. They saw to it that I didn't after that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, no!

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Before that happened, he was sending his kids and his wife up to my house to take showers. He even brought the dog up once.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, he actually cut off his nose to spite his face in a situation like that.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Navy attempt to give you any language training when they sent you over? Or was it just what you could pick up on your own?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

None whatsoever. No language training.

Donald R. Lennon:

It seems like that would be the natural thing to do.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

We were told we didn't need to know it, that we would always have a translator. There was a translator assigned to our organization over there, but you were dealing with Turks. Most of whom spoke English, but not all of them. To have one translator to be the liaison for everybody who wanted to talk with a Turk was pretty impossible.

Donald R. Lennon:

Exactly, what was your duty?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I was to be the communications advisor to the Turkish Navy. They had asked for one. The Joint American Military Mission for Aid to Turkey had been there for over a year when I got there. I was like a second echelon and my billet had not been filled before.

Also, I was a tennis player at the time and found out the Admiral was looking for tennis partners. I ended up doing a lot more tennis playing than I anticipated while I was there.

While there, I had the opportunity to fly with my wife to Rome. We were to land in Rome at 2:00 a.m. and leave at 2:00 a.m. the next day. I told my wife that there was no way we could take a standard tour and get her to see what she would like to see. So I would be her guide for that period. I did take her around. I had only one mission of my own to accomplish. I had been impressed that there were so many churches in Rome and I wanted to get a picture of a typical Roman church.

Every now and then in our tour of the city, I would back off to an alley and try to get a picture of a church, but it wouldn't fit. It was too big. I finally found a church that fitted my lens while I was in an alley across the street. So I snapped the picture and happily went on with the tour of Rome for my wife. I guess it was two weeks later when I got the pictures. I found out that I had taken a picture of the only Greek Orthodox church in Rome!

We returned from Turkey.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we leave Turkey, you were there for what, three and a half years, something like that?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Until 1953 probably.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

We went over there with two kids and came back with three.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were over there earlier than Fred Wyse was, weren't you?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I think so. I am not sure when Fred was there.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was sometime during the 1950's. It may have been 1957, 1958, somewhere in that period.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I left in 1952.

Donald R. Lennon:

It has been a long time ago since I had thought about that. I know when he was there, he indicated that part of his duties was intelligence.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I was not assigned to any intelligence duties.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have any intelligence duties?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I did entertain a complaint from the Turks. They had been given some minesweepers as well as a couple of destroyers. They were complaining that the radio

equipment wouldn't function on the minesweepers. I asked them what the complaint was. Well, they didn't have anything to control the frequency. There seemed to be a place for frequency control, but there was nothing there. I said, “Well, we always send the equipment with the frequency. You must have had somebody take them out.”

They investigated and found one Turkish warrant officer had been assigned to have custody of this equipment. He recognized the stealability of these crystals, so he took them all out and put them in a safe. He hid them safely away and kept the equipment from being used. Once this was discovered and the crystals were dispensed, they had no problems.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he wasn't trying to steal it. He was just trying to safeguard it?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

That's right. He was responsible for it and was going to keep it safe.

Donald R. Lennon:

And he didn't tell anyone. That's interesting.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I came back from Turkey by air. I planned the trip so that I could land in Athens and Rome and Lisbon and the capital of Spain.

Donald R. Lennon:

Madrid.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Madrid. So we had these four stops on the way home, which was going to give us a sampling of what the four countries looked like. But what we hadn't completely thought out was that each place you stop, you have to change money, go through customs, and in our case, we had to find a baby-sitter. Unfortunately in our case, we also had to find a native doctor who spoke English for the kids, a pediatrician. This happened coming and going to each of these capitals. It was a pretty good hassle just making those visits.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just getting in and out.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I was assigned to the staff of Commander Second Fleet after that. We were stationed in Norfolk, Virginia, sometimes ashore and sometimes aboard a flagship. The flagships varied and we would go out on exercises where we were controlling the exercise normally.

After a couple of years with Commander Second Fleet staff, I was ordered to operations officer of the USS ROANOKE, a light cruiser. I did that for a year before they ordered me to take command of the USS FURSE, destroyer 882. It was occupied with the exercises in the Atlantic east coast area, including Guantanamo Bay. I had found that the FURSE was named after a Marine from Savannah, Georgia. I promptly dismissed this from my mind because ships never go into Savannah. Lo and behold, one of the exercises off the East Coast we were participating in was curtailed for some reason, I forget what, but the ships were sent to various ports. Our ship was sent to Savannah.

As we were approaching the dock in Savannah, I noticed that our dock had a big, black limousine on it. It looked like some dignitaries were going to be involved. I tried to figure out what this might be, and it suddenly dawned on me. This is where the fellow lived that the ship was named after. That probably had something to do with it. It turned out that two elderly ladies, who were aunts of the person the ship was named after, had come down to go aboard. One of them was handicapped and had to go in a wheelchair. It was a mad scramble coming alongside and setting up for the important visitors.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, you said that you were in and out of Guantanamo at this time. Was this 1954 or 1955 period?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Actually, it was 1956, 1957.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's right as Castro was beginning to get things heated up down there, wasn't it? Before he came to power. Were things quiet in Cuba to the best of your knowledge when you were going in and out?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

No. They were having trouble in that Castro was cutting off the water to Guantanamo Naval Base. Then somehow the base would get it turned back on. The Navy grew tired of this. They installed a distillation plant on the docks in Guantanamo Bay so that they could make their own fresh water. They had been through the process of having it brought down by tanker and decided this was too cumbersome.

I left the FURSE in 1957. I was ordered to the Naval Academy. My first wind of this came about while I was at sea. I received a message saying that this new skipper was coming aboard, but where I was going was not disclosed. So, as soon as we got into port, I called Washington and found out what they were going to do with me. I was told I was going to the Naval Academy. I said, “That's great! How did you happen to light upon that?” They said, “Well, you asked for it.” I said, “No. I didn't ask for it, but that's great. I am glad to be going.” They said, “Oh, yeah! We got it here. Back in 1941, you said you would like to go back there and teach navigation. That is what we are ordering you back for.” It is quite true. I remember when I was an ensign, I got the navigation duty early and held it for a couple of years. I wanted to go back and teach the midshipmen how realistic this subject was. I put it in for my shore duty preference--I had to put down something--and I put down to teach navigation at the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, see the Navy and military actually do examine those preferences you put down and go by them, even if it's sixteen years later.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

By this time, we had the computer available so they had stuck all this data in the computer and it coughed that up. I spent five years at the Naval Academy being executive of the Seamanship and Navigation Department, most of the time. One year, I was head of the department; but, at that time, they decided to revamp part of the Naval Academy. They had taken the teaching of leadership out of the executive department and put it over in Luce Hall, where Seamanship and Navigation was the department. The Aviation Department was also in Luce Hall. They decided to abolish that and have all this seamanship, navigation, operations, aviation, leadership all taught by the former Seamanship and Navigation Department. They decided the name was no longer appropriate and, for a substitute, they came up with calling it the Command Department. Nobody outside the Naval Academy knew quite what to make of the Command Department.

I got to be the first head of it because the new captain, who came in to take over that department, died on the tennis court within a couple of weeks after he arrived. The admiral told me that he wasn't going to push for a relief; he would like me to run it for the first year. So I did run it for a year. Then when the new one came in, I reverted back to being his executive.

While there, we had occasion to make a group visit to the Air Force Academy, which was quite new at that time, being about 1960, I guess. The first thing we did at the Air Force Academy was go in for a briefing by the superintendent. There evidently had been comments within the services about the extravagance of the Air Force building and equipping their academy.

The superintendent was telling us, as a group when we arrived, that it was not true that they spent all this money. They only spent a smaller amount, which he quoted, but I don't remember what it was. Then we had a tour of the Air Force Academy. I remember coming away with the distinct impression from that tour that the superintendent was “stacking the deck”; they really had spent all that money. Their defense was that they acquired in-house equipment in the Air Force for free. So a lot of the equipment we were seeing cost them nothing at that time; but it cost somebody something at one point.

I left the Naval Academy to become communications advisor or communications officer for the Commander Amphibious Group II and moved back down to Norfolk. In that job, we made several amphibious landings as part of Atlantic Fleet exercises. One of them I remember had the code name “Steel Pike.” That job, as with Commander Amphibious Group II, also involved the title of Alternate Commander of the Atlantic Fleet, (ALTCOMLANT). At this time, they were concerned that if Norfolk should be bombed and the command of the Atlantic Fleet headquarters should be bombed out, who would take command of the Atlantic Fleet? So they created this ALTCOMLANT, which was a rotating billet for some Fleet command--some admiral, who had to be either at sea or in some non-prime target port. For instance, we did spend some time in Bermuda as ALTCOMLANT. We spent some time just cruising around out in the ocean as ALTCOMLANT. You had a more than usual communication requirement for this duty, which was my cognizance. After a couple years with that, I was transferred to Commander Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet as the assistant chief of staff for communications.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that around 1963?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

1965.

Donald R. Lennon:

1965.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I did about a year as assistant chief of staff there, where my classmate was the chief of staff. Then I retired--put in for retirement. I was told that I could not put in for retirement because they were about to order me to the Pentagon. I said, “No. I can't afford the Pentagon. I need my Navy salary and to work for another salary as well to raise these kids.” So I did retire.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you do in retirement?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I was going to live in Norfolk, where we were living at the time--we had a seven- bedroom house--or we were going to go back to my hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina, which my wife had fallen in love with. She was perfectly willing to go there, but the job that popped up was in Bethesda, Maryland, with Boozy-Allen Applied Research. So we moved to Rockville, Maryland, about ten miles from Bethesda and I have been in that house for thirty-four years now.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was it you were doing with Boozy-Allen?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

We were dealing with contracts--some with Naval ships, some with Naval electronics, some with Naval ordnance. The company did other contracts besides Navy, but since I was retired Navy, I was mostly involved with Navy contracts.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, very interesting. Any last thoughts? Any last anecdotes that you can think of?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

French Morocco. After we had successfully put the troops ashore and we were just tied up to the dock there, our ship was asked to provide soundings of the harbor to see whether the troop ships could come into the harbor. They put me out in a rubber boat

and one enlisted man with me. We were taking soundings when we realized--now this was only hours after we had gone alongside dock--that there were bullets going overhead and bullets landing in the water not too far from us. Some of them weren't just landing; they were hitting the water and ricocheting, splatting. I decided that those bullets were coming from the jetty that sticks out there and protects the harbor. Somebody over there was shooting at us. All I had was a 45-caliber pistol and I am sure the jetty was out of its range or close to out of its range. Still I felt I had to do something, so I fired a test shot to see where the bullet was going to land. It hit the water not too far from the jetty. I changed the aim a little, fired again, and fired a few more shots. I didn't see any splashes and we got no more splashes in the water beside us. So I claim maybe I got one!

Donald R. Lennon:

Either that or you frightened him away, one of the two.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Maybe I just frightened him away. We had no more dangerous situations like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

You never did see whoever it was?

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

Never did see anybody.

While I was a midshipman at the Naval Academy, my first cousin down in Quantico, Virginia, was getting married. My father's brother was the postmaster in Quantico and he had four daughters, so he had involvement with Marines. The number three daughter was marrying a Marine. She was the one closest to my age, so I was invited down from the Naval Academy. I was surprised to find they would let me go. When I got there, I found I was the only unattached male, so they promptly made me the bartender--something I had never done before. But I remembered watching my father make old fashioneds and mint juleps, which of course are mostly whiskey. So that is the

way I mixed drinks. It wasn't long before they were carrying Marines away from this party. They were a bit too strong.

It was normal for people stationed in Turkey to go out to the airport to see people off that were going back to the States; also to go out there to meet somebody who was coming in for duty. We went out there one day for that purpose to see somebody in or out. I can't remember which. It was along about 1950 and the first jets visited the Ankara Airport. We saw them fly in and land. I couldn't help but notice that although they were not connected, there were camels carrying cargo off the airport. I don't know where they were going, but we had jets coming in and camels walking away.

Donald R. Lennon:

From one extreme to the other. I understand that it is a very interesting country around there.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

On board the ship going over there, these Turkish Army officers were enthusiastic about speaking English with us because they had supposedly learned some in the States and they wanted to practice it. So we pumped them for some of their Turkish as well, but on first meeting, we introduced this Turkish captain to Captain Agnew from the U.S. Navy. This was a Turkish Army captain. So what does the Turkish Army captain say but, “Oh, glad to meet you, Captain. I am a captain, too.” There is a considerable difference in rank really, but the same name.

I also remember riding in the car from Ankara to Istanbul, which was an all dirt road--no paved road yet in 1950. We passed by a small settlement, hardly big enough to be called a village or a town; but somebody had very ingeniously devised a Ferris wheel made of wood, probably only about twelve feet tall. It had four seats, but the kids were enjoying it just like we would enjoy our full sized one over here.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I believe our tape is just about to go down.

Edward C. Hines, Jr.:

I lived in a number of places, including across the street from State House, 23 State Circle in Annapolis. When I married the schoolteacher, we displaced her roommate and took over the apartment. I had once been engaged to a girl from Annapolis. It turned out when I went back there to PG school, she was doing things for the Naval Academy Alumni Association and she would hire Annapolis schoolteachers to help out with projects in the summertime. So, when I met my bride to be, she was working for my former fiancée. When I finally decided to reveal this and did so, my wife said, “Oh. I knew that.” My former fiancée sent the ring back to me about a month after I had left town and gone to sea the first time. She sent the ring back with no comment. From then until I saw her again in 1946 and even then, she made no comment as to why she decided to do that. I could only speculate. I saw her again at my wife's funeral. She waited in line to talk to me and finally came up to me with her arms extended. She said, “You don't recognize me, do you?” “No,” I said. She said her name and I realized, “Yes. That is the gal I was engaged to.”

[End of Interview]