[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

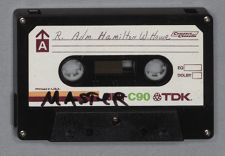

REAR ADMIRAL HAMILTON W. HOWE, USN (RET)

INTERVIEW #1

(Part 1, 00:02) The following are recommendations or notes for a prospective commanding officer of a destroyer:

(Part 1, 00:11) 1. Always, or nearly always, hold captain's inspection, and be sure that you are part of the inspecting party. Let it be known ahead of time that there is to be no wet paint wherever you may be inspecting. Of course, this is in case of a regularly scheduled inspection. Be sure that there is a list of all defects noted on the inspection and that this is published. Then as subsequent inspections occur, defects which have not yet been corrected reappear with the date on which they were first noted.

(Part 1, 01:07) 2. Get fitness reports off on all officers right on time. There is never a good time for writing them, but they must be done promptly, out of consideration for the officer reported on and also out of consideration for you.

(Part 1, 01:34) 3. Practice taking sun and star sights and working them out.

(Part 1, 01:44) 4. Remember that the buck stops with the skipper. There is no further place to move it; it stops right there.

(Part 1, 01:56) 5. It is important to visit the engineering spaces from time to time. I have seen a number of ships where the captains do not seem to manage to get below decks. That is a mistake. Leaving the inspection of engineering spaces to other officers on a regular basis is not good. The engineers want to see the skipper, and they deserve to see him.

(Part 1, 02:29) 6. See that all hands maintain a practical, smart, seagoing uniform. The practice of the crew appearing in almost any item of uniform -- any combination that happens to appeal -- is unnecessary and should be resisted, in fact not tolerated.

(Part 1, 03:06) 7. Always look over the charts for wherever you are going. You may well recall what happened to the battleship Missouri when that ship was to run the degaussing range. The ship went aground, and the career of the very brilliant and fine officer, Bill Brown, was forever ruined.

(Part 1, 03:42) 8. Call on the squadron commander at the earliest opportunity, but first ask permission to call.

(Part 1, 04:21) 9. Take an objective and frequent look at the ship's side. The ship's side and the topside are the parts of the ship that are seen most often by others. Therefore, it is important that they are representative of what you want the ship to be.

(Part 1, 04:48) 10. It was always said that there are three topics that are not to be discussed in the wardroom -- politics, religion, and women. You might ask, "What else is there to talk about?" However, it is a good idea, generally, to steer away from those subjects because they can easily become controversial and heated, and are better avoided.

(Part 1, 05:29) 11. From time to time have conferences with your heads of departments. It enables them to better know what you want, what your plans are; also, it enables them to tell you about their departments.

(Part 1, 05:59) 12. Paperwork deadlines are important. They should be set and then adhered to. The executive officer is the one, of course, who is generally responsible. If he is fortunate enough to have an excellent chief yeoman, much of his work is made easier. Mostly paperwork is what you as the skipper are judged by because more people receive communications from you than ever get aboard.

(Part 1, 06:47) 13. It is important to give consideration to personal problems of the officers and crew. If the men know that the skipper is interested in their personal problems, it can mean a great deal for morale.

(Part 1, 07:12) 14. I have a story that I like to tell involving two former skippers of mine. This has to do with the maintenance of morale and the general tone of the ship. When I was aboard the Tulsa on the China Station, we had a skipper named Paul Rice. He was a very kind man, very likable, and generally well regarded by the crew as well as by the officers. However, as we were a station ship much of the time, the shore going opportunities were rather regular. It seemed that every day after liberty expired in the morning, the captain held mast because there were always a goodly number of people who had been AOL and in some rare instances AWOL. Captain Rice would hold mast as he was supposed to, but he would be very, very lenient. As a result, the absentee list remained very long. Finally, there came a time when we learned that Commander Rice would be relieved by Commander "Red" Reinicke. There was an officer on board the Tulsa who had served with him and remembered that Commander Reinicke was really one tough officer. He opined that things would certainly change when the new captain came aboard. We officers were concerned and certainly were not looking forward to his arrival. However, the day came and he took command. Soon he started holding mast. He began with the usual long list of people who were late returning from liberty. What did he do? He "threw the book at them." What about the list of people returning late? It diminished, and as the days passed, we did not have mast some days because there were not any mast cases. The men got the word. They learned that the captain would give them the maximum, and seldom would any excuses be accepted, so they got back on time.

(Part 1, 10:58) 15. Do whatever you can to get a good barber. That can make such a difference. It means that your crew, as well as the officers, will look the way they should. Good barbers are hard to come by, but if you can possibly manage to get hold of one, by all means do so.

(Part 1, 11:27) 16. Obviously, good chow is highly important. The skipper really needs to sample meals. I have seen many a skipper who would pass up that duty, and as a result the men in the galley were not as eager to produce good food. Also, the skipper should, once in a long while, eat in the crew's mess hall. It means a lot to the men to have the skipper come down and actually see what they are getting to eat. The sample meals that are sent to the bridge or wherever the skipper might be are not always quite the same as those that the men get in the mess halls.

(Part 1, 12:33) 17. Keep your executive officer informed of almost everything unless you discover that that really does not work after all. Most of the time it will.

(Part 1, 12:52) 18. Never call an enlisted man by his first or his nickname. That is not good for discipline. When on watch all officers are Mr. "So and So." Or now do they use the rank? In my day you did not call anybody by his rank in direct address below the grade of commander.

(Part 1, 13:25) 19. Remember the old axiom, "The less you say, the less you have to take back."

(Part 1, 13:36) 20. When getting ready for sea, batten down thoroughly. The crew may grumble, but insist on it, and you will be glad that you did when you suddenly encounter some heavy seas.

(Part 1, 14:00) 21. Do not apologize. State the way things are to be, and that is that.

(Part 1, 14:11) 22. In the matter of pilots, whether to take a pilot or not is an important decision. I know that it is desirable not to take a pilot in a number of cases. But whenever there is the slightest doubt, do not hesitate to do so.

(Part 1, 14:41) 23. Sunday in port can be an opportunity for seeing some rare sights. Occasionally, go back to the ship for perhaps a concealed reason. You may be surprised what the ship will look like the first time you do; but after a visit or two, you will discover that the ship is ready for visitors on Sunday also.

(Part 1, 15:32) 24. Do not bring your family aboard ship very often. Occasionally, yes; but I have known of ships where families came aboard at every opportunity, and, eventually, were resented by the other officers, and to a certain degree by the crew.

(Part 1, 15:56) 25. When you relieve, you make the statement, "All orders of Captain Blank remain in effect until further notice."

(Part 1, 16:11) 26. It is a real good idea for planning purposes to have a leave program established. You cannot always stick to this, but it is helpful if the officers and crew realize that there is a schedule which you will carry out if you possibly can.

(Part 1, 16:47) 27. Work on your standing night orders, and be sure that they do not cover more than necessary; but be especially sure that they do cover all that is required, based on Navy regulations and on your good judgment.

(Part 1, 17:15) 28. Do not hesitate long in making a decisive course change if you have a steady bearing on another ship. Obviously, you have to be sure that your course will not take your ship into shallow water or trouble.

(Part 1, 17:42) 29. It is really a great advantage if you can read blinker; and that can be brushed up on by the use of a blinker-buzzer set. Be sure that you refresh your recollection of the international flags, and brush up on semaphore.

(Part 1, 18:16) 30. The skipper gets a great deal of respect when he reads the flashing light just about as fast as the signalman, when he can read the flag hoist, and when he can pick up semaphore.

(Part 1, 18:37) 31. Do not apologize for any lack of experience. Let your officers take the conn as soon as you feel you can turn it over to them. They will appreciate the opportunity, and it is valuable to have officers who can handle the ship.

(Part 1, 19:16) 32. Give the minority group personnel equal but not preferred treatment. They should measure up to the same standards demanded of the rest of the crew.

(Part 1, 19:43) 33. I like the philosophy of letting the officers and crew know that you intend to have the finest destroyer in the whole U. S. Navy, and then keep preaching that doctrine. In time, they will come to believe it, and, eventually, you may well have the very best ship in the fleet.

(Part 1, 20:19) 34. It is important to know and follow Navy regulations.

(Part 1, 20:26) 35. Plan to have things done the way that you want them done. Hold mast frequently and err, if you must, on the side of plenty of punishment rather than not enough. Then, as in the story that I related about Captains Rice and Reinicke, you will find that you do not have to hold mast so often.

(Part 1, 21:30) 36. There is a very fine axiom that you know, but it is well to recall it: "Take heed what you say of your seniors, be the words spoken softly or plain, lest some bird of the air tell the matter and you shall hear it again."

(Part 1, 22:03) 37. Name dropping is not a good idea. People really do not like name dropping, and in time, if it is repeated often, they can actually come to resent it.

(Part 1, 22:30) 38. I recommend that you have a good knowledge of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

(Part 1, 22:52) 39. If you are unfortunate you may get an exec who is not very much good. Also, you may have an exec who is a talker and not close-mouthed. You will have to make the best of the bad situation.

(Part 1, 23:09) 40. The chiefs and the first class petty officers can be towers of strength, but do not allow the department heads to feel short-circuited. I have seen that happen.

(Part 1, 23:24) 41. Underway fueling--that is really quite a challenge. One of the ways to achieve success in that, in addition to reviewing all procedures carefully, is to develop a few good helmsmen. Two, or better three, experienced helmsmen are most important.

(Part 1, 23:53) 42. Plan to put nearly everything through the executive officer if you can. (Note item 39.) One philosophy that seems to work out well for a ship is that the skipper is a prince; the exec is an S.O.B. That is ideal, but if the exec simply will not be the type to really carry through firmly, it may be necessary for the skipper to be the tough one.

(Part 1, 24:36) 43. Be sure you have at least two pairs of eyeglasses; if something happens to one, you have another pair that you can use in the emergency.

(Part 1, 24:51) 44. Have at least one smart new uniform, cap, pair of shoes, and gray gloves, as well as sword, white gloves and medals for captain's, commodore's, and admiral's inspections. Do not forget the well-laundered shirt with cuffs the way they should be, collar the way it should be, and neckties that are fresh and look like new.

(Part 1, 25:30) 45. Develop a good piloting team, and be sure that piloting is done wherever regulations call for it. It may seem unnecessary, but in the event of any difficulty a court martial will want to know all about the observations that are made and the tracks that are plotted. Remember that radar, important as it is, is not the whole answer, and that radar is no better than the operator or the adjustment of the particular set. Be vigilant, ever vigilant.

(Part 1, 26:46) 46. Never hesitate to inconvenience if proper, prudent procedure is in order; and do not be rushed by an old commanding officer who is waiving relieving before you feel you are really ready to take over.

(Part 1, 27:06) 47. [uniform]

(Part 1, 27:41) The check of registered publications is highly important. You must take all possible measures to ensure that the registered publications charged to you are actually there. Explaining a lost registered publication can become one of the most difficult things that can ever happen to an officer.

(Part 1, 28:13) 48. Remember the Pueblo. Every time I think of the Pueblo, I shudder and wonder how members of the U. S. Navy could have allowed such a catastrophe to occur.

(Part 1, 28:40) 49. The next item is a letter written from Denver, Colorado to a young man who was about to enter the Naval Academy. I am placing it with my papers in the hope that it may be of use to some other young man who may be thinking of becoming a midshipman.

(Part 1, 29:15) 50. Dear [name],

(Part 1, 29:16) 51. Inasmuch as there is some chance that we will not be back before you leave for Annapolis, and because I am committed to indulging myself in some words of advice and some "how to succeed" philosophies, I am writing you this letter. I do this despite the probability that your father will have covered many of the same things that have occurred to me. I know that much of what I have to say may well be redundant because your own rearing and good judgment will lead you to many similar conclusions. Such qualifications as I possess to suggest deep water courses to steer by, and maximum avoidance of rocks and shoals, derive primarily from my own experience as a midshipman and a naval officer, and secondly from observing my son's action pattern as a midshipman and officer and my brother's career at the Naval Academy.

(Part 1, 30:20) 52. Enjoy whatever you do. In some instances your first reactions may be otherwise, but there will be much that is good in each and every activity, be it nautical, academic, athletic, or extracurricular. Emphasize the like and de-emphasize the no-like.

(Part 1, 30:49) 53. Be as regulation as you possibly can. Demerits are not cute nor smart, and furthermore, they adversely affect your class standing. A few demerits happen to nearly everyone, but neatness and promptness help keep their number down. Make every moment available for study count. The work is hard and dawdling can be costly. The academic competition will be intense. Many midshipmen will be older and with more years of education behind them. How you stand in your class will be a matter of personal satisfaction, and also may mean many dollars in pay when promotion opportunities come later. Do not try to be popular with upperclassmen. Do be responsive and pleasant to them. Do not take the running too seriously. Plebe year is not even twelve months long. Keep a stiff upper lip.

(Part 1, 32:06) 54. Make it a habit never to speak ill of anyone, be he an upperclassman, a classmate, an officer, or a girl. If honesty prevents favorable remarks, say nothing, and never criticize your school or the navy. "Take heed what you say of your seniors. Be your words spoken softly or plain, lest some bird of the air tell the matter, and you shall hear it again." When the going seems to be toughest, remember the many thousands of young men who have survived the four years at the academy and the vicissitudes of life at sea. Don't give up the ship! Be quietly enthusiastic and remain as objective as possible.

(Part 1, 33:01) 55. "To thine own self be true." Never do anything you really know to be wrong. In the unlikely chance that you are ordered to do something wrong by an upperclassman, do not do it. The academy is a great institution, and it achieves its mission of producing the finest naval officers in the world, but it certainly is not perfect. You probably will find a few classmates and upperclassmen whose moral standards and obscene language belong in an X-rated movie. Not many of these types seem to make it to graduation. Most officers strive to fit the classic definition of a naval officer, as expressed by John Paul Jones.

(Part 1, 33:52) 56. You are joining a proud officer corps, closely knit by mutuality of interests. Among your classmates you will find friends who will be close friends for the remainder of your life. You will be getting a free education costing the taxpayers many thousands of dollars -- about $40,000 I understand. Upon graduation there will be a paying job and the opportunity to commence an honorable and respected career which will be challenging and interesting and varied. Value it all.

(Part 1, 34:34) 57. We appreciated your fine letter written in thanks for our high school graduation remembrance. All good wishes for a highly successful four years at the Academy and a rewarding career in the United States Navy!

(Part 1, 34:49) 58. Affectionately,

(Part 1, 34:52) 59. [signature]

(Part 1, 00:03) EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

REAR ADMIRAL HAMILTON W. HOWE, USN (RET)

INTERVIEW #2

(Part 2, 00:12) [You were talking about the U-boat situation.]

(Part 2, 00:19) I was saying that I was sure that what I had hoped to have for you today was more in line with what you actually wanted. I was thinking in particular of a two-night situation that occurred when I commanded the Earle. Previously, I had had command of the U.S.S. Roper when we were successful in sinking the first U-boat of the war--that is, the first U-boat sunk by a surface vessel. This occurred off Bodie Island Light, which is off the coast of North Carolina. We were successful; we were fortunate.

(Part 2, 01:22) This situation arose as follows: We had been getting a great many radar contacts as we patrolled an area off North Carolina from Hatteras to the Virginia Capes in an effort to reduce the number of sinkings of merchant vessels by German U-boats. But we were bothered very greatly by the number of small craft that seemed to be out there, trying to do their very best for the country, but nevertheless representing obstacles to our searches. At this particular time, I had been turned in just a short time when I got word from the officer of the deck that a contact had been made and he wished permission to investigate. I okayed the investigation because the contact was near enough to the bow to make it possibly worthwhile. I supposed that it was one of the small vessels of the U.S. Navy, or even a fishing boat. Somewhat reluctantly, I climbed out of my bunk and went on the bridge.

(Part 2, 03:17) We discovered by our plot -- actually we had one of the first radars -- that this contact seemed to be moving very fast through the water. I decided to sound general quarters, thereby manning all stations, torpedo tubes, main battery guns, and machine guns. Gradually, we built up speed to 20 knots, which enabled us to close on our target. I continued to feel that it would turn out to be a small U.S. vessel, and I was so greatly concerned about that probability that it was my decision to first turn on our big searchlight to illuminate the target. We were ready all the while to open fire if by any chance I was mistaken. Shortly before the searchlight was to be turned on, we saw the wake of some object in the water passing down our port side. It made a very definite phosphorescence. Big fish often do leave a phosphorescent wake under certain conditions, but this streak went down our side on a line. We had stationed ourselves on the starboard quarter of the target just in case it turned out to be a submarine which could fire a stern tube. We later determined that it had actually been a torpedo.

(Part 2,05:28) The light went on, and we beheld a German U-boat, the U-85. The crew was manning the gun. We opened fire and made a number of hits on the conning tower and their gun's crew. Then the U-boat submerged, and we lost contact temporarily. We circled around and dropped depth charges. Then we made what we thought was a new contact. It definitely was a submarine, so we launched a depth charge attack. As we were in the midst of our run, we heard shouts in the water of "Hail Hitler."

(Part 2,06:41) When dawn came the next day, we knew that we had gotten a U-boat as we recovered the bodies of twenty-nine German seamen.

(Part 2,06:59) But I was really starting to tell about what happened later when I left the Roper and took command of the new destroyer Earle. This time my ship was part of the escort for a fast troop convoy. At the time we were homeward bound and about two days out of Casablanca. There had been no reports of enemy submarines in our vicinity. The Earle was stationed on the port quarter of the convoy for no particular reason known to me; but then we surprisingly got a contact. This was about (20:00) p.m. Again, I had turned in, and I came to the bridge when I heard that contact had been made. There were a number of other destroyers around, including a battleship, all of which had radars searching, but no one else had made a contact except the Earle. We thought we probably had a phantom, and we tried to shake it by changing course. Sometimes that is possible, but this one would not disappear. I reported to the escort commander. He or his staff officer -- whoever answered -- seemed quite unimpressed, and evidently figured that we did not have anything because no one else did. But we were positive by then that we did have something. So we circled around and then moved in on the target. Again, I was most anxious to be certain that I did not have a merchantman that had dropped out of the convoy or a small boat. So I decided that I would use the "Roper" technique of turning on the searchlight just before we opened fire. I was particularly concerned in this situation because the night was extraordinarily black, the visibility was just zero, and I realized that I had a number of ships loaded with American troops up ahead. I had no desire to be the first to sink one of our own ships. I tried to get a solution from the flagship which could give me angles through which I might fire without any danger of hitting a troopship, but I got no response. When I turned on the searchlight and almost instantly opened fire, we had a big Italian submarine that was on the surface just starting to submerge. We got a number of hits in the conning tower and elsewhere on the hull. I am positive that, had we had a matter of half a minute reassurance that we were in a good situation as far as attack was concerned, we would have definitely gotten this vessel. Despite our gunfire, our searchlight, and all the fuss we were raising back on the port quarter of the convoy, it remained very difficult to convince the escort commander that we really had something.

(Part 2,12:23) [He was just oblivious to all this?]

(Part 2,12:27) He did not believe it. I do not know what he thought we were firing at; we were certainly not firing at the moon because there was none... Rather reluctantly, I felt, he assigned another ship and the Earle to stay with the contact and keep it down while the convoy went on. I was the senior captain of the two, so I was in charge. We got orders to destroy the contact if possible; but, in any event, keep the contact below the surface of the sea and then rejoin by nightfall.

(Part 2,13:20) The convoy went on, and we continued our radar and sonar searching. We got a number of sonar contacts and we made several depth charge attacks, but we were never able to see anything on the surface, and, as I recall, we never actually got any debris.

(Part 2,13:50) [At times it is very difficult to determine if you have destroyed a submarine, isn't it?]

(Part 2,14:01) That is true. The British used to say that the only way you could get credit for a U-boat was to produce what they called "boots" and braces." The Germans -- and I guess all submariners -- used many devices to fool the attacking ships into thinking they had made a kill. They would do such things as releasing debris, garbage, clothing, and even oil through their tubes. I am sure they frequently were successful in causing ships to feel they had made a kill when actually that was not the case.

(Part 2,14:48) It was interesting that we stayed with this contact a little longer than we should have, in order to rejoin the convoy on time. We went back at better than full speed. We did not go at maximum power because we were concerned about our fuel supply. When we were about to reach the convoy, I estimated that the Earle would again be assigned to the port quarter because we had made a contact there when no other ship had been able to do so. We were fortunate to have a very fine radar and excellent operators.

(Part 2,15:50) [They had gotten past the bedspring stage by this time.]

(Part 2,15:56) Right. So to my amazement, because we were late and because of what I have just said about our being the only ship that apparently had made contact, we were assigned to the port bow of the convoy. It took us another hour or so to get to position, but we finally did. If we had stayed on the port quarter or in a stern position it would not have taken us nearly so long. The convoy was long, and it was making as much speed as it could to clear the submarine zone. I think it was about (11:00) p.m. when we reached our area.

(Part 2,16:54) At the moment I cannot recall if I had turned in this time or not; I think I had. Then lo and behold, contact! We reported it, of course, but nobody else had picked up anything. There was the Earle up on the port bow of the convoy and the only ship to make contact. Again, the escort commander apparently did not believe that we could have anything.

(Part 2,17:33) [Who was the commander?]

(Part 2,17:38) I think I know, but I had better not give his name. Anyhow, I decided to follow the same procedure. We learned we were tracking a target on the surface. It could have been a small ship; but surely such would not be coming into a convoy. My gunnery officer told me he had completed the solution as far as the directors were concerned; the torpedo officer reported ready to fire torpedoes; and we had everything all set. We illuminated, and by golly, there was a German U-boat fully surfaced, coming in for a surface attack on the convoy. Almost immediately I opened fire with the guns and launched a torpedo. The radar people had seen the target; they had known that the torpedo and guns had fired; and they had seen the target disintegrate on the scope. We were positive we had gotten a kill. But the records after the war did not substantiate that we had done so. We were awarded a probable kill, but not a certain kill because we could not produce the physical evidence.

(Part 2,19:59) [You made a believer out of the commander though, didn't you?]

(Part 2,20:01) I think at least he finally concluded that the Earle's radar was the finest in the U. S. Navy.

(Part 2,20:10) [Talking about the Roper, when you were here off the coast, did you have much trouble with fishing boats and this type of thing?]

(Part 2,20:30) Yes. We did.

(20:31) [Was it because they just did not want to cooperate?]

(Part 2,20:35) No. It was very early in the war. People generally were relatively inexperienced, and everybody was gung-ho to do everything possible. So I think it was just one of those things we just had to submit to. It was a situation where there was some confusion, but we were most concerned about the ships that were being sunk every night. We had already rescued survivors from torpedoed merchant ships.

(Part 2,21:22) [So it was just not the case of people on the North Carolina coast taking the danger seriously?]

(Part 2,21:31) No, it was not. I have no criticism of the other vessels out there. They were doing the very best they knew how, and they were very patriotic in risking their lives. It was a situation one had to adjust to.

(Part 2,21:52) Another problem we faced when we came in close to the coast was the fact that there were many wrecks on the ocean floor. There were wrecks caused by U-boat sinkings, and wrecks that were there for other reasons, that had been there a long time, perhaps. Also, there were shoals which often would appear the same as submarine targets. So there were many difficulties.

(Part 2,22:32) [I am sure the danger of hitting one of your own ships or a civilian ship was real, was it not?]

(Part 2,22:40) Oh, it was? There is no question about it. In fact, speaking of that, one time when we were on this same coastal patrol assignment, and as we were coming out of the naval shipyard at Norfolk standing down the Elizabeth River to go out and relieve one of the ships of our division, to our amazement we passed the destroyer Dickerson making a lot of speed coming up the river. This was the ship we were due to relieve. We eventually found out that she was bringing in her badly wounded skipper. We learned that what had happened was that in conducting searches or inspections the night before, this destroyer had been mistaken for a submarine by the captain of an armed guard crew of a merchantman who opened fire. The first shot entered the bridge of the destroyer and went into the chart house -- emergency cabin. The skipper was in his bunk, and a shell severed his feet. Then the shell dropped down to the radio room, which was just below the emergency cabin, and wounded a couple of radiomen. The skipper, J. K. Reybold, was a Naval Academy classmate of mine. It was a very freaky thing. They fired two shots; the first, unfortunately, was very effective, and the second missed.

(Part 2,25:00) [Frequently your armed guard personnel or officers were in the reserve with less experience, were they not?]

(Part 2,25:09) Well, that is true, but I would not want to be critical of the armed guard captain of the gun crew. He had a very difficult decision. He simply made an honest error. The angle at which the destroyer approached with everything darkened made this apparition appear to be a submarine.

(Part 2,25:53) [You were operating out of Norfolk?]

(Part 2,25:56) Yes, at this particular time we were operating out of Norfolk. We were attached to the inshore patrol, and we would go out and operate for a week or part of a week and then come back and be relieved by someone else. It was interesting duty.

(Part 2,26:18) At one time while my ship, the Roper, was attached to the inshore patrol under the command of Captain Treadwell, following routine procedure, I went to make a report after having been on patrol. I walked into Captain Treadwell's office and saw a lieutenant sitting there whom I thought I recognized and who seemed to recognize me. I was a lieutenant commander, but I figured he was a Naval Academy classmate of mine who had left the service and then come back in. That explained his being one rank junior. Eventually, it came my chance to see Captain Treadwell. While I was in there talking to him, in came this other officer, and I was introduced to Lieutenant Richard Barthelmess whom I had never known of course. I had seen him in the movies, on the silent screen. He looked quite young. He had a ruddy complexion and coal black hair. I did not expect to see him in a naval uniform, and I did not expect him to look so young. He turned out to be about ten years my senior. He seemed to know me, and we discovered that during the encounter with the U-85 his ship was one of those that was out there that night. So I was delighted to meet a famous matinee idol of earlier days.

(Part 2,28:46) The Roper was involved in the rescue of the so-called lifeboat baby. The MS City of New York had been torpedoed off the Virginia Capes, and we were instructed to look for survivors. In fact, we spent the whole night searching for survivors, and we took many on board. About 4:00 a.m. I got word that a lifeboat had been sighted. I recall going aft to the torpedo tubes, and I got there about the time this boat came alongside. The lifeboat was crowded with people. Our ship's doctor joined me. To our great surprise, first out of the lifeboat came a naked baby who was handed up by a man whom we later determined to be the City of New York's doctor. Our doctor opened up his Navy windbreaker as protection against the cold night air and put the baby in it.

(Part 2,30:36) [How old was the baby?]

(Part 2,30:39) Less than two days old. Of course, we were very excited about this unusual rescue. We had put cargo nets over the side to aid in recovering survivors, and later we discovered that the mother had climbed up a cargo net on to the deck and had been escorted forward to the wardroom area. When I finally got down into that area, the wardroom, I saw that she had turned in and was asleep in a bunk. She had taken a shower. There was evidence of blood on her clothing as there would be with the birth of a child. I was delighted that we had rescued this baby. We learned that he had been born about three hours after the ship was torpedoed, and in the lifeboat. According to the story, which we have reason to believe to be true, the doctor, after he delivered the baby, reached over the side, and learned the boat was in the Gulf Stream because the water was so much warmer than the air. He washed the baby in the Gulf Stream. Thus it was that this little boy's first bath was in the Gulf Stream of the Atlantic.

(Part 2,33:00) I had the thought that it would be real great if, under the unique circumstances, the baby was named for the ship. Later on I learned that Mrs. Desanka Mohorovicic had decided to carry out my idea. So the child became Jesse Roper Mohorovicic.

(Part 2,34:16) [Were there many casualties from the sinking of the MS City of New York?]

(Part 2,34:21) Yes. About thirty were lost. A total of 89 survived.

(Part 2,34:34) [The baby's father was not on board?]

(Part 2,34:36) No. The mother and her two-year-old child were on their way from Lourenco Marques, Mozambique, Africa, to join the father who was an attache of the Yugoslav consulate in New York City. I guess she eventually got to New York. I can still see this woman in that stateroom. She was quite a heroic and remarkable woman to manage to climb up the side of the ship. She never complained or asked for help.

(Part 2,35:30) One rescue came close to my heart. There was a father with his little daughter that we had taken aboard, and the little girl was just the age of my own child, so it was especially meaningful to me. We learned that the mother, father, and child were in the water together, but the mother went down and only the father and little girl were rescued.

(Part 2,36:21) a rescue, although they were so very rusty that at first they couldn't understand us and we couldn't understand them, but I would say, inside of a month's time, they were doing pretty well in English. But it was a different matter for the for the enlisted personnel. So I had a very brilliant young officer on my staff who came up with the idea that we ought to contact Harvard and bring down Dr Richards and his staff. And this was done, and we we rewrote all of the textbooks in what was called Basic English. Then we we taught or we did at the same time. We taught the the officers. We taught our own officers basic English, and then we proceeded with naval instruction in basic English. So, teaching basic English, well,

(Part 2,37:30) had the naval training center there at Miami been in existence prior to the war?

(Part 2,37:37) No.

(Part 2,37:37) Was it? No, no.

(37:40) We took over commercial facilities.

We took over hotels for barracks and those pier facilities for offices and training classrooms and so on. That's Dr Richard in there, and someone conceived the idea, and as they wanted a picture of a woman and that

(Part 2,38:06) well, did the Chinese have much of a navy? No, no, they did not to train for

(Part 2,38:12) No, they didn't. But as as in, in every case, the people were trained for ships and in ships. Then they were given these ships by the US.

(Part 2,38:27) So under Lynn lease, we were providing the ships trade. It would seem kind of waste to train them and say destroyers or cruises or what have you, and then they have to go back and serve aboard sand pants, absolutely

(Part 2,38:43) well, they weren't quite that rudimentary, but, but anyhow, that's that is.