EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION

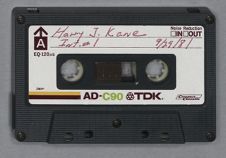

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #71

Mr. Harry J. Kane

U.S. Army Air Corps Pilot

World War II

September 29, 1981

Kinston, North Carolina

Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon

[Mr. Kane was a U.S. Army Air Corps pilot during World War II, flying patrols off the south Atlantic coast during which he attacked and sunk German submarine U-701.]

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you tell us particularly as to where you came from, how you got into the what was known as the Army Air Corps, and wound up in Sacramento.

Harry J. Kane:

All right. Well, I was advised by a man who at the time was a family lawyer, because the war was impending, I was advised by him to get into something so that I wouldn't have to go into the infantry. This '40-'41 mostly '39-'40, right in around there. So, I went to Roosevelt Field, which was out on Long Island.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were living in New York at the time?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, and started to take flying lessons, and I actually had a private pilot's license before I went into the Army Air Corps. I applied to both the Army Air Corps and the Navy, and I seemed to lean more towards the Army because I wasn't too interested in flying over the water. That's the funny part about the whole thing, that most of my flying

was over water even though I was in the Army Air Corps. So I took my training and got my private pilot's license and was accepted in early '41, went to Lakeland, Florida, for a primary flight training which lasted approximately three months, and then to what was known as basic training at Montgomery, Alabama, Gunner Field. Then we spent about three months there, and then we went to advanced flight training. This is all before the war started; this is all in 1941. I can't remember what month it was when I got too advanced, but the advanced flight training was at Barksdale Field, Shreveport, Louisiana. By this time I had been designated to go into what was known as twin-engine training. I took my twin-engine training there at Barksdale Field and graduated and got my commission as a second lieutenant, and got my wings and whatever. I'm pretty sure it was December 12, 1941. We were called the war-baby class, because we were the first class of flying cadets who graduated after the actual start of the war. From Barksdale Field, Shreveport, I went to the west coast. Since the war had just started everything was very messed up, and it seemed like I just went from one place to another, mostly in the state of Washington. Then suddenly I got transferred to Sacramento, California. Of course I was a very young pilot at the time, just out of my high school by a matter of months.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't flying any kind of missions on the west coast by that time or were you mostly patrol. Were you flying the twin-engine planes?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes. We, or I, was checked out as a copilot in an old tiny airplane known as a B-18. It was simply awful; and I believe that we were expecting an attack from the Japanese on the west coast, because at Sacramento I think we were known as the second line of defense. Every morning about three o'clock, and I'm not sure of that time, I know it was pitch black dark, we, the crew, from the copilot on back through all the enlisted

personnel, would have to be in the B-18's, have them cranked up, warmed up, ready to go. It was necessary. I think they would have sent us out to find the ships that the Japanese had come in to attack with, and we would try and bomb them or sink them.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to say, is the B-18 an earlier bomber?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, it's a bomber, or it was a bomber.

Donald R. Lennon:

To me it was the B-17's and the B-24's

Harry J. Kane:

Right, the B-18 was much older, I don't know why it had a number higher than the B-17, I don't understand that, but it was a twin-engine, and it looked to me like it was a vintage from World War I. I don't believe it went more than 120-130 miles per hour.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lumbering old crate.

Harry J. Kane:

Right. So, we had to sit in those. Of course the older pilots could all stay in the operations room, keep warm, and all that business; but we had to stay in the airplane and keep the engines going and so forth. They would keep us out there usually with the engines running until daylight, and then they'd cut them off, and that was the end of that. But anyhow, I kept doing that for a number of months right after the war started.

Donald R. Lennon:

How old were you at this time?

Harry J. Kane:

Twenty-three I think. Then we got a new line of airplanes called A-29, which was a Lockheed Hudson, quite a bit faster, more maneuverable than the old B-18's. Of course, we had to check out in those again and get all accustomed to going in them.

Donald R. Lennon:

At this time there was no action really on the west coast.

Harry J. Kane:

Not that I know of. We had heard that the Japanese had sent a submarine over here, and it shelled the West Coast, but I didn't personally see anything. We were concerned, in fact quite concerned, that they were going to attack the United States through California. But anyhow most of it was training and patrol which consisted of

flying up and down the Pacific coast, covering most of the state of California. There were mostly other squadrons further north that took over in up around Oregon and Washington and so forth. But, training was most of it. I have an interesting experience that I'd like to tell you after the training. Would you like to hear it?

Donald R. Lennon:

Certainly.

Harry J. Kane:

The big problem as I saw it then was lack of communication. At one time we got a whole batch of new navigators into the squadron and we had to take them all out and give them some real tough training. On this one occasion I had this young navigator with me and we flew out from San Francisco right over the Pacific Ocean. This was an interesting navigation problem. As I recall it, we flew due west two hundred miles and then we turned due south and the problem was for the navigator to tell me--the pilot--when to turn so that we could take up a heading of seventy-four degrees that would bring us into March Field, which was right down near Los Angeles. It was a pretty good navigation problem. Well anyhow, we got down to the point where he said “all right go ahead and turn to seventy-four degrees,” and we started back and the weather started getting bad and the sun was going down. Of course, I didn't know it at the time, but I was an unidentified aircraft.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no.

Harry J. Kane:

And so I'm coming in towards Los Angeles from a long ways out at sea, I mean I must have been four hundred miles out over the ocean, because of the way the California coast curves in there as you get down south towards Santa Barbara, and so forth. I didn't want to rely one hundred percent on the navigator because the weather was getting bad, and so I had my radio on, and I would get a direction fix on Los Angeles, we'll say, and another direction fix on San Diego, and try to cross the two and get a pretty good idea of

where I was, as to back up what the navigator said. The weather kept getting worse and there are some islands out there. If you ever study the West Coast, you'll see some islands off the West Coast, I think they're called the Catalina Islands, but I'm not sure. There are a number of them off of Los Angeles. If you ever study them carefully, like I as a pilot had to do, you'll find that they are about twelve hundred feet high. Well, that was the situation underneath us. We were on top the clouds and all of a sudden I noticed I couldn't pick up the Los Angeles radio and in about five or ten minutes I noticed I couldn't get the San Diego radio. So then I didn't have any means of checking on the navigator and so I called to him and said “I've got to go down and see what's going on. Are we clear of the islands?'

Donald R. Lennon:

What altitude were you flying at?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh, about three or four thousand, above the clouds. I'm not sure of that, it wasn't way up high, you know. And so we started to do what they called a dead reckoning letdown. And remember the islands were twelve hundred feet high. So we came down slowly in the clouds now to say three thousand and then two thousand, fifteen hundred and we still couldn't see the water. We hoped we were still over the water. So I kept letting down and got to the twelve hundred foot point. Still couldn't see the water, and anything below that was quite risky, but I kept on going down. I asked the pilot, “Are you sure,” I mean the navigator, “Are you sure we are not going to run into the islands?” and he said “Yes.” And so we kept coming down and I got to six hundred feet, which of course, is way below level and we still couldn't see the water, and at this time my copilot just couldn't stand anymore and he started yelling or screaming or something, and so we had to go back up. Well we kept on hitting on our seventy-four degrees up above the clouds, and finally the weather started to break and we saw we were over land and the

navigator evidently did a wonderful job because we came right over March Field, and as we got over March Field the radio tower at March Field, called me. By then they even knew what my name was, usually they just refer to you as a numbered airplane. They said, “Lieutenant Kane, you are requested to land at March Field as soon as possible, General so-and-so wants to see you.” So I landed, I was just a young second lieutenant, and went up to see the General, as I was ordered. And he said “You stupid blank, blank, blank, do you realize what's happened?” and I said, “No.” And he said, “You were an unidentified aircraft and you have blacked out all of Los Angeles and all of San Diego and put the radios in both places off the air and I have sent four P-38's up looking for you with instructions to shoot you down.” But, they couldn't find me. But, anyhow that was an interesting situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you were under the instructions to fly that exercise weren't you?

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah. But evidently San Francisco didn't notify Los Angeles. That's what I was saying, the big problem was the breakdown in communications. San Francisco knew because I went right over them going out and was in contact with them. But evidently somewhere there was a breakdown in communication and San Francisco didn't let Los Angeles or San Diego know what I was doing, and when I made the turn to seventy-four degrees, which you know is about east by northeast, I estimate I must have been out four hundred miles out in the ocean, cuz I went out two hundred miles up by San Francisco and then turned due south, and so they picked me up on the radar or whatever.

Donald R. Lennon:

Radar was pretty primitive in those years.

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yeah. Somehow they picked me up and they were supposed to have what they called an IFF, which stands for, I think, Information, Identification Friend or Foe I think, and possibly mine wasn't working, I don't know, but all of a sudden they had this aircraft

unidentified four hundred miles out in the ocean heading towards Los Angeles. And so everything busted wide open. The whole city of Los Angeles blacked out by me, and I just think it's quite exciting that one person could do all that. But that was before I came over to the East Coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

If one of those planes had found you, it might have ended you career rather prematurely.

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah, unless they were sharp enough to recognize the markings on my airplane.

Donald R. Lennon:

But if you'd been in the clouds at the time they couldn't have.

Harry J. Kane:

Well, back then they would have had trouble shooting me down in the clouds you know. Later on in the war, when they had all of these refined things that they could shoot through clouds and all that, it was different. But back then they would have had to see me, and if they couldn't see me, I mostly would have been reasonably safe, but I hope that if they had seen me that they would have recognized the markings on the airplane and seen that it was not Japanese. But then you never know, some young buck you know says, “Oh boy! I'm going to shoot down an airplane, I'm going to be a hero or something,” and something like that could have happened. But that was the type of training we were doing and patrols were flying on the west coast before we came to the east coast. And we kept that up from early 1942 until June, and then we moved the whole squadron to the east coast. Now before you start again, do you want to jump from that over to when I got to Cherry Point?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you said that you moved to the east coast at this point. Is there anything else concerning the west coast experience that was worthwhile?

Harry J. Kane:

I don't think so. I mean the whole thing was training.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you fly your planes from . . .?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

And these were the A-29's?

Harry J. Kane:

29's, yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Which was a fighter plane?

Harry J. Kane:

No, it was what they call a light bomber, and the “A” stood for attack. They had some “A” designated airplanes during the war, but back then, in the early part of the war, they didn't have what they call fighters, they were pursuit. See? Like it was the P-38 for pursuit 38. Today it's the F-105, or some such thing, for fighter, “F” for fighter. “B” for bombardment, which I would think most planes came into because even fighters were sent out on bombing missions. They carried bombs and machine-guns and so forth. The “A” type airplane was a bomber, but much more maneuverable than a conventional bomber.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a crew did it carry?

Harry J. Kane:

Usually it carried a crew of four, but it could have gotten by with less. It could have gotten by most likely with three. In the time of the U-701 incident we actually had a crew, counting myself, of five.

Donald R. Lennon:

Pilot, copilot, navigator?

Harry J. Kane:

No, no that was not it. Pilot, no copilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, engineer. There wasn't any . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

No gunners as such?

Harry J. Kane:

No, but they all would have fill-in, secondary jobs and so forth. Everybody on there was trained constantly to fire the machine guns.

Donald R. Lennon:

Anyone else trained to fly the plane in case of . . .?

Harry J. Kane:

Well in my case, I trained everybody to fly the airplane. I always looked at it as though I might get shot or killed some way or other, and if the people knew enough to keep the airplane flying straight and level until they could get somewhere where they could bail out, then they might be able to save their lives. So I at least taught everyone who was, ever on one of my crews to fly the airplane straight and level, to learn how to put it on automatic pilot, and things like that, and so that if I just suddenly wasn't there the chances are the plane wouldn't just go into the ground, it would be able to keep going.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they had automatic pilot on them back then?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh, yes. The A-29, yep it was a much faster airplane than the old B-18 that I mentioned earlier, but it was treacherous and had a terrific tendency to ground loop. Ground loop, now in case anybody doesn't know, is when you actually spin an airplane on the ground, it gets out of control and goes off to one side, usually to the left. Just spins around and usually destroys the airplane, sometimes it kills everybody in it. These planes had a terrific tendency to ground loop. The reason was the torque was terrific, and when you'd go to take off it had a terrific tendency to pull to the left. You had to overcome it by leading your left throttle about an inch ahead of the right throttle when you were pushing them forward to take off setting to give the left engine more power than the right engine to keep it from trying to ground loop. And, on landing they were very, very treacherous. Had a terrific tendency to bounce, and usually when they did, they would stall and, when you stall an airplane that close to the ground, it's usually the end. Because in a stall one wing usually drops; the plane doesn't stall just like so, it usually stalls then falls off on one side. There's one wing that will usually stall ahead of the other. If they stalled straight ahead all the time, the stall wouldn't be so bad, but

usually one wing will stall ahead of another wing, and therefore the wing that stalls first, that side will drop. And if you get in that position, close to the ground . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

You don't have time to compensate.

Harry J. Kane:

Right, you can always out if you've got plenty of time, there's no problem about coming out of a stall if you've got plenty of altitude. It's when you don't have the altitude that a stall becomes very treacherous.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now you left and came to Cherry Point. What did you find on your arrival at Cherry Point?

Harry J. Kane:

Well, the time of training was then apparently over, and when we went out we were on actual missions, and I don't know whether they were called combat missions or not, but we went out fully armed as far as machine guns were concerned and as far as bombs concerned.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was at Cherry Point at that time? This was a new camp, a new base wasn't it?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, it was a very new base; in fact, there were hardly any paved streets. The runways were paved, the streets, as I recall them, were all dirt, and the personnel at Cherry Point--this is very interesting, I'm glad you asked that question--the ranking Marine Corps officer at Cherry Point, was a lieutenant colonel. There were no Marine Corps pilots at Cherry Point. There were two Navy squadrons and one Army squadron manning the whole base, the whole Marine Corps station at Cherry Point. People in the Marine Corps today just won't believe that, but that's the way it actually was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any civilization around there at all, or was it still purely rural?

Harry J. Kane:

To my knowledge it was purely rural.

Donald R. Lennon:

Either New Bern or Morehead City were the closest people.

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, there was something at Havelock, but you know, it's just practically nothing. I can't remember exactly but mostly just a few houses. But it was desolate country, in fact we used to kid each other that it was the same as being overseas, being stationed at Cherry Point in early 1942. And so anyhow we got to Cherry Point, flew all the way across the country, didn't make any speed records or anything. We stopped in Tucson I think and somewhere in Texas, I can't remember, I think it was Dallas, and then Memphis, Tennessee. There were about thirteen, fourteen, fifteen airplanes in the squadron. I think we lost two of them coming over, nobody got killed, but we wrecked two of the airplanes, had to leave one in Dallas I believe, and one in Memphis.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many planes in the squadron?

Harry J. Kane:

Well, I think there were fifteen to start with, now I'm not sure of that, it was right around that, it might have been thirteen, but let's say fifteen that was close. And when we got to Cherry Point, we had two less than we started with and got to Cherry Point on the fifteenth of June 1942. That's about the time I met my wife, met her on the nineteenth of June. That was sort of an interesting story, would you like me to tell you about that?

Donald R. Lennon:

Sure.

Harry J. Kane:

A friend of mine, another second lieutenant, Ed Goray was his name, he and I had hitched a ride. Now, officers aren't supposed to do that, but back then there was no way to get from Cherry Point down to the beach. So, we stood out in front of the base with our second lieutenant bars on, and finally somebody came along and picked us up. And so we got down to the beach and went swimming, and then got a bus ride back from Atlantic Beach back into Morehead City. We were right in the middle of Morehead City walking down the street, the main street, I think it was Arendell Street. Of course we

were in uniform, and we had the wings on, we were pilots, and some lady stopped us on the street and said “I see you boys are in the Air Corps. I have a son who is in the Air Corps.” And this is an interesting story. I said to the lady, after we introduced ourselves, I said “What is your son's name?” and she said, “Wyatt Exon” and I said, “Not W.P. Exon?” And she said, “Yes, a lot of people called him W.P.” And I said, “I knew W.P. Exon in Spokane, Washington.” Well, I just thought that was so interesting because here we were three thousand miles away from Spokane approximately, and ran into a person on the street and she was the mother of a boy I used to go around with who was in the Army Air Corps.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right

Harry J. Kane:

In Spokane, Washington, way back in the very early part of the war, I mean back January of '42, something like that. And so it was through her that I met my wife. She said “Well you two boys, I'd like you to meet some young girls here in town.” And she said, “I know quite well one of them is having a house party.” And she set it up, and we went over there to Mrs. W. D. LaRoake's cottage. Mrs. LaRoake turned out to be my mother-in-law later on, in other words, I met my wife right there of the nineteenth of June; we'd only been there since the fifteenth of June. But then the patrol started, we were flying on patrol pretty heavy and we would fly patrol from about an hour before sunrise until about an hour after sunset.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were these single plane patrols, or did you fly . . .?

Harry J. Kane:

Single plane, single plane patrols. They had more than one going on at a time but not two in the same area. It could have happened that two would be, but it wasn't planned that way, overlapping or some such thing. We flew from Cherry Point out to Cape Lookout and went out about twenty-five miles, of course we were definitely out of

sight of land. Then one patrol would fly south, which wasn't exactly south, it was about southwest, to cover or parallel the coast, then we'd go as far down as Charleston. The other patrol would go north, as I recall up to Cape Hatteras and maybe a little bit further north, and then back. But between the two, we about covered the whole North Carolina coast, one going south and one going north. The missions were usually about five hours long, maybe a little longer than that, five and a half hours, and as I recall there were three of them each day. And so we covered the area for about sixteen to seventeen hours out of the twenty-four hours. The rest of it was dark, and we didn't have any equipment to find submarines at night. We would go out and fly, and we could hear them talking to each other on the radio in German.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you knew they were there but you couldn't . . . ?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yeah

Donald R. Lennon:

. . . couldn't tell where.

Harry J. Kane:

Couldn't see them or pick them up. One night I went out with an older pilot; it was the first day of the month. I can't remember whether it was the first of July or the first of August, but in order to get your flying pay you had to put in at least a minimum of four hours flying time a month. On this particular time I left and took off at 1:00 a.m. and we came back in and landed at 5:00 a.m., and I already had my flying time in on the first day of the month for the whole month. We kept on just flying that patrol which got quite boring, because you never would see anything, see freighters and so forth like that and convoys and we had instructions of what to do about convoys and how to patrol over them, and so forth. I saw an awful lot of ships being sunk or right in the act of sinking. Saw one that I remember very well because I didn't have a car, and I had to leave the little car that I had on the west coast. I saw this freighter going down, I evidently had

gotten there just an hour or so just after the submarine had hit it, and it was so sad to me because there were about fifty brand new cars on the deck.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, no!

Harry J. Kane:

And there I was without a car and I could see all those cars just slowly going under the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was an American freighter?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yes, I think they were Packard automobiles.

Donald R. Lennon:

Outbound towards Europe or something?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, or South America or something like that. But I actually watched that thing go down.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any search and rescue missions going on at that time?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yes, quite a bit. See they had, of course, the Coast Guard was there and the Navy was there and they had types of airplanes that could land on water. The Coast Guard had these dirigibles or blimps or whatever, and they could stay stationary and, if somebody was lost at sea, if they had a pretty good position on where they were, they could usually find them, if they didn't drown too soon. Of course in my case with the U-701, it didn't work out that way, but usually if one of our freighters was hit by a torpedo from a German submarine, people that got out in the water in life boats or life rafts or whatever usually could be rescued. Now I'm not saying that happened all the time, but I mean I'd say most of the time they could be rescued. But there were an awful lot of ships being sunk out there, awful lot of ships being sunk. Now, I'd like you to ask me some questions.

Donald R. Lennon:

O.K. well you're leading up to of course the events that have to do with the U-701.

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah, in other words I'm getting close to it now, I'd say through the month of June or a half month of June and, of course, this the U-701 thing--was right after that, it was the seventh of July.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is early in your stay at

Harry J. Kane:

Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Cherry Point, early in your patrol duty. Up until that time I take it everything was routine with all you were seeing were ships that had already been hit without being able to do anything about it.

Harry J. Kane:

We couldn't do anything about it. The Lockheed Hudson I was flying was the only airplane, to my knowledge, that had any speed at all, and the blimp, of course, oh blimps couldn't go fast at all, and planes that the Navy had were called, to my recollection, OS2U's. They were single-engine and they could land on either water or land. They had pontoons underneath and wheels that were retractable, but they were not very fast.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there very many naval vessels out there, destroyers, or cruisers or what have you, trying to locate the subs?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think it'd be kind of frustrating from the air to have a responsibility for patrol and looking for subs when you knew that the possibilities of you locating it were rather remote.

Harry J. Kane:

There were quite a few naval vessels out there. I don't see really how the submarines stayed away from them, but you know they mostly didn't come up unless they had checked out the area around there, made sure there were no vessels in sight. But I could see numerous vessels, some quite small in fact, and of course the big things, the

things that the submarines were mostly interested in was the freighters, carrying oil or whatever. They weren't too interested in some little pleasure boat or something like that; they wouldn't waste their time with it, if it wasn't important enough for them to, they wouldn't waste a torpedo on something like that and they wouldn't come up and try to sink it because it wasn't worthwhile.

Donald R. Lennon:

Troop ship would have been different.

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yeah, now that's something large, of course, but I'm talking about . . . Okay, so I'll start trying to tell the story. We were out on one of our patrol missions one time, and I saw this great big old tank floating in the water. It looked like the type of tank you'd see in a gasoline station that was being put underground, at most only about a ten-thousand gallon tank, and I thought it was a hazard to navigation, so I made the decision to try and sink it with machine gun fire. So I made a number of dives on it and fired the fixed machine guns through the nose of the airplane, and hit it a few times, missed it most of the time but never was able to sink it. When I came back I reported it because I thought it was necessary, that it should be reported, and my squadron C.O. called me in and said “You weren't supposed to do this, you used up ninety rounds of ammunition and I'm going to charge one dollar a round for the ammunition you used.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it cost you about a month's pay just about.

Harry J. Kane:

Well, back then a second lieutenant got two hundred dollars a month, of course we got flight pay, but it wasn't . . . the two hundred was including flight pay as I recall it. I think it was something like a hundred and twenty-five or a hundred and thirty to thirty-five dollars or something like that was base pay for a second lieutenant, and then you got fifty percent more for flight time and between the two it came to about two hundred dollars. If you were unmarried, you didn't get any extras at all. If you were married,

they gave you some kind of living expenses, but at that time I was not married, and so I could more or less count on about two hundred or two hundred and twenty-five dollars tops per month, which was pretty low. So, when they took ninety bucks out of that, they took a pretty good whack of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Okay, the incident with U-701.

Harry J. Kane:

Well that happened right after the month of June, in fact that exact date was the seventh of July, and I was on the middle patrol, the one that took off about 10:15 in the morning, and I was on the south league; that is the one that went down all the way to Charleston, South Carolina, then turned around and came back parallel to the coast, heading up towards Cape Hatteras, and then we were supposed to turn back into shore from Cape Hatteras. All right. My ideas on why I got the U-701 are, first of all, and this is just my recollection I want you to remember that, that I was doing something that was not exactly what I was told to do. I've got to say something right here for my own sake and anyone else who might listen to this. This is something that happened thirty-nine years ago and this is by memory and, of course, there might be, a few errors in there--I just cannot remember exactly correctly. But the way I recall we were told to fly at about one hundred feet above the water on patrol. On this day there were broken clouds at approximately twelve hundred feet. So I decided to get in the clouds, rather than fly down low. I climbed up to about fifteen hundred feet and in this situation I was above the base of the clouds, and since they were broken, I was in them and out of them. I was mostly in them we'll say for two or three minutes and I'd break out for thirty seconds and then I'd be back in them for two or three minutes and I'd break out for ten, twenty, thirty, forty seconds something like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Could you still see the water from the clouds?

Harry J. Kane:

When I'd break out I could see the water, when I was in clouds I couldn't and, of course, likewise nobody else could see me, and that was the reasoning. So, on one of these times that we broke out we saw something on the water that was actually closer to shore than we were. It was so far away that we couldn't make sure what it was. We saw this boat or object on the water and, as I recall it, it was seven to ten miles closer to land than we were. We didn't know at the time that it was a submarine, and we stayed up the clouds and kept on straight on our course like we had been, which was a heading of about forty degrees, forty-five degrees just about northeast, paralleling the North Carolina coast. We broke out of the clouds a number of times and by this time, I'd gotten everybody in the crew to try to help me decide what it was and finally we thought, well, it might be a submarine, and, we weren't sure, so we turned to a heading of almost due west and stayed up in the clouds, and I remember that I throttled back the airplane to try to cut down on the noise. I estimated that I stayed in the clouds heading due west, approximately due west, for about five miles and then with the throttle to the airplane pulled back pretty far, so the engine was just idling, I broke out of the clouds, diving down from about fifteen hundred feet. By this time, I was only maybe four or five miles away from this object on the water. By now it began to look like it might very well be a submarine. About this time the people on the boat, which was a submarine, must have seen me, because suddenly it submerged. Course, as soon as we saw this, we knew it was a submarine, there was no doubt then, and so we pushed the throttles all the way forward on the airplane and then proceeded as fast as possible to the point where the submarine had gone down. I yelled at the bombardier to get down there underneath and get ready to go and get the bomb doors open and all this excitement and everything and we were moving pretty fast that time. I think in my report I said something like 225 miles an hour.

We were just about fifty feet above the water, and we came across the submarine and, as I recall it, I could still barely see it from up where I was sitting, but, of course, the bombardier had a much better position, but we came right across it heading in about the same direction that it was, oh I'd say about due west. In other words, both of us were heading right towards shore, which still a long ways off--we couldn't see it. Now at this stage, people have asked me, “Well, did you drop the bomb or did the bombardier drop them?” And the only answer I can give to that question is, “I really don't know.” They could be dropped from either the bombardier's position or the pilot's position. I know there was an awful lot of excitement, and I can remember yelling at the bombardier in quite strong language, is it all right to say anything of this?

Donald R. Lennon:

Sure.

Harry J. Kane:

“Drop the goddamn things!” Of course I had a little red button on the wheel, so the pilot could also drop the bombs in case it was a situation where there was no bombardier, and so I didn't know what happened to him, and I knew we wouldn't get another shot, so I was pushing the little button all the time myself. So actually in answer to that question, “Did you drop the bombs or did the bombardier drop them?” I cannot answer it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You both may have.

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah, right, see in other words it was like that light has two switches to turn it on; it can be turned on from either switch. If you couldn't see when the light came on but somebody told you it came on, and yet you and another person were working both switches, you might not know which one actually turned it on, see. So that would be a situation similar. There were two buttons or two switches or whatever to drop the bombs from. I didn't know whether maybe something had gone wrong with his, I didn't know

that, and I wasn't going to take a chance to that we flew over them and didn't drop them, because if they weren't dropped, by the time I could have gotten back . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

He'd be gone.

Harry J. Kane:

He'd be gone. He'd have been down so deep by then that I couldn't see him, and it would just be a lucky shot, see, and so he, if I missed him on the first shot, then he had a ninety-eight percent chance of getting away on any future.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

Harry J. Kane:

So it was either drop them right there or don't. So I didn't want . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

How many were dropped?

Harry J. Kane:

Three is all we had. I think they were classified as three hundred and twenty-five or three hundred and fifty pound depth charges, they were not bombs, they were depth charges. And they didn't go off hitting something; they went off from water pressure, and I believe they were set beforehand at twenty-five feet. When we'd dropped them they'd go into the water and when they got down to where the pressure was sufficient, they would go off. The three were dropped in train is what they'd call it. Like if this was the submarine going that way, and I'm coming in like this, then one, two, three, I mean that was the idea. I think that the first one missed, I'm not sure. I think the second one was a very good shot, and I think the third one was a very good shot.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened then?

Harry J. Kane:

Well, I pulled up slightly and made an abrupt turn and I could see this terrific explosion. Might have been the last one of the three depth charges. It was like a great big enormous bubble, and I'm just going to guess that it was fifty feet high and, of course, at this time we knew it was a submarine, but we didn't know whether we'd definitely gotten it or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't circle back over the . . .

Harry J. Kane:

Oh yeah, I circled back, but you see finally men came up. But between the time that we dropped the depth charges and turned around and actually saw the men come up, which might have been a minute, or maybe two minutes later, we didn't know that we'd gotten the submarine. We saw how rough the water was and everything; it was all bubbly and everything but when the men came up then we knew, see because as I've said before, they would send up oil slicks and they'd throw out

Donald R. Lennon:

Debris.

Harry J. Kane:

Right, rubbish, garbage, just about anything to make you think that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you couldn't have done any more anyway if you'd used all three of your charges.

Harry J. Kane:

No, unless they came up and I tried to machine-gun them. I mean that's all I had left. I had the fourth bomb; there were four, but the fourth one was the one we used to call a practice bomb. We were supposed to drop it on every mission that we went out on, and just to keep in practice. We went out with three real depth charges and one practice bomb, and we were supposed to come back with three depth charges, and this time of course I dropped my depth charges. But then we saw some men come up. At this stage of the game, I did something that most likely nobody else would have done. I estimated there were about fifteen, sixteen, seventeen men. Now the crew of a German submarine is usually about forty, possibly as high as forty-five, and I saw, I think I counted seventeen. Now this, what I am about to tell you next, is the thing that to me made the whole thing so interesting and especially in later life when I found the German captain and we started writing back and forth. I threw out all my life preservers and the life raft that we had, and, of course, we were still about, you know, twenty, twenty-five miles out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they not have a raft?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh, they had some German escape lungs I think they were called, but not all of them did. Evidently they had to get out so fast they didn't have time to get, [all of them] some of them had them, some of them didn't have them. It's a very fascinating piece of equipment that I didn't know anything about until just recently, but besides being like our Mae West, it had a mouth piece so that they could breathe. I don't know how long, but they could . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Long enough to get out of the submarine?

Harry J. Kane:

Right, yes, and also to come up. They didn't have to hold their breath the whole time coming up if they had one of these; if they didn't, they did. But anyhow, I threw the life vests that we had and the life raft. We stayed out there for awhile. We're getting low on gas now.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you call over your radio . . . ?

Harry J. Kane:

I tried to, of course. I had a radio operator, and he was supposed to take care of that, and he had a blinker light so that if we saw somebody, he could signal with the light. I saw a freighter--I'm estimating about five miles away--and I flew to it to try to get it to stop or send a small boat or something, see if they couldn't rescue some of these survivors. The freighter signaled back congratulations, but he wouldn't stop for nothing.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you hadn't gotten the sub, the sub may have gotten him

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah, and of course I think they were worried to death, and this is just my thoughts, that there were submarine packs out there, and that there would be two or more working together, that if had gotten one, there were still others and that if they came back, that they would be a perfect target for the others, so he wouldn't even consider it. Saving lives didn't mean anything, and he just wired back congratulations, and I

remember I said this is in my report, I could see the bow come out of the water as he picked up speed getting away from there. Then I went back as best I could, and this is the part that I regret, because I was such a young pilot I didn't have the training that I would have had if I'd had more time or experience. I never was able to find the men again, and I flew back a reciprocal course from the time that I left to go get the freighter. I did find . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't take a fix on the spot at the time? Your navigator didn't get a fix on the spot?

Harry J. Kane:

Well, we're supposed to have dropped something or we threw something out--some kind of a smoke device to mark the spot, but then we went to the freighter and turned around. Of course, I can remember checking the course going to the freighter and, you know, you are supposed to be able to fly 180 degrees to that and come right back. Well, we tried our best to do that, or I tried my best to do that, but I never did see the men in the water again. I may have been an eighth of a mile away from them, and they are very hard to see. You just have a little bit of, a little bit of wind or something that caused ripples so that the white little wave-like things in the water . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Caps.

Harry J. Kane:

White caps yes, and that could be caused by a man in the water, it could be caused by something else, and you see those wherever you look.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Harry J. Kane:

So you might be looking right at them, and yet you can't see them. If they had had something to attract us like a mirror or something like that that they could have shown, we might have been able to pick them back up, but we never could pick them back up. I stayed out there until it was actually becoming hazardous as far as fuel, and I

think this next thing ought to be brought in here because I think it is pertinent. The A-29 or Lockheed Hudson had four gasoline tanks, and I ran three of them dry to the point where the engines actually sputtered, and then I just I couldn't stay there any longer. Before I left I did come across this patrol craft and I found out the number was the 4-8-0, patrol craft 4-8-0, and I signaled to him about what had happened and I flew out to where I thought the men were and circled until he got right under me, and then I said “I've got to go.” In fact when I did leave I was on my last tank, and when I got back in they told me I had five minutes of gas left. The mission, instead of lasting five or five-and-a-half hours, lasted something like seven-and-a-half or seven and three quarter hours.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was it normal for a pilot and crew when they sunken enemy ship to be that concerned about the survivors?

Harry J. Kane:

No, I don't think so, I don't think so. I think this is just something I did on my own. I was never told to do it; I was never told not to do it and I'm glad that I did do it you know, since I've found the German captain [and] we have talked. In fact, he has sent me, in one of his first letters . . . he tells me the story from his point of view, which is quite something, and he has a little aside written in there where he says “Thanks Harry for the life preservers that you threw.” So, I mean it sort of means something, and

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you got back to Cherry Point, what happened then in the reporting process?

Harry J. Kane:

Well the whole thing is so cut and dry it's just, there's just nothing, you know, just very boring. All you do is go sit in front of some guy and tell him the best you can what happened and make a report of it. Then it goes out to all the bases on the east coast, and then they start the search. They start looking for the survivors, because it is more

than just saving lives. I mean, they want to get information, right? So, they were able to rescue seven of them and one was the German captain.

Donald R. Lennon:

So of the seventeen that you saw, only seven of that seventeen actually . . .

Harry J. Kane:

Well no it wasn't even, it wasn't even seven of the seventeen. I didn't know this of course, at the time, but of the seventeen I think only three or four lived, because some others got out later while the submarine was sitting on the bottom. They didn't come out the same way. Now this is something I just found out recently. They came out through a hatch up near the bow of the submarine. I don't know how they got out, but some of them did. Now they were in the Gulf Stream, and the Gulf Stream is a current moving north, northeast, about two nautical miles, two knots an hour, approximately. Now, when the second batch got out, the first batch that I saw had already drifted possibly a mile or so, see. So, when the second batch came out there was about a mile separating the two of them, and they couldn't see each other. They didn't know anybody else got out, I assume. But when the man who found them . . . and I have [since] found him, which is very interesting, he was the pilot of the blimp from the Coast Guard station in Elizabeth City. When he found them, it was forty-nine hours later, a hundred miles north of where I sunk them.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they floated for two days.

Harry J. Kane:

Forty-nine hours, two days approximately.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they using your life raft or ones that they had salvaged from the submarine, I wonder.

Harry J. Kane:

Well, they were using some of mine and some of theirs, and the story I got was that they tied them all together to make something that they could all hang onto. Most of them drowned after they got out; it was quite horrible from my stories from Horst Degen.

Out of the seventeen, I'd say about thirteen of them drowned, and his description of them drowning was very, very gruesome. Then there were some others that got out of the bow that I knew nothing about--I must have already had to leave by then. Some of them most likely drowned also, and when they were found they had drifted about a hundred miles and the position where they were found was marked very accurately so we'd know where they were found and the interesting thing is that when they were sunk, to the best of our ability, they were twenty-four to twenty-five miles offshore. When they were found, they were 110 miles offshore.

Donald R. Lennon:

Goodness, just floating around.

Harry J. Kane:

Northeast, see, the current wasn't going due north right along the shoreline.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

Harry J. Kane:

It was bringing them away from the shore, heading out towards Iceland or whatever. Possibly if they lived long enough, which, of course, they couldn't have, but if they had, they might have gone all the way across the ocean. You know, I mean if they'd had ways to sustain themselves. I don't know how the Gulf Stream goes, but it heads sort of northeast. It follows the coast down a little further south then North Carolina, but when it gets up to the state of North Carolina, it tends to turn out away from the shore.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, those seven were

Harry J. Kane:

Well, they were in two different groups.

Donald R. Lennon:

Pretty fortunate to have gotten out.

Harry J. Kane:

Yeah. See that out of the seventeen that was the group that the captain was in, all of them died except four. Out of the group that got out the bow of the submarine, say thirty minutes later, and the pressure in there would keep the water from coming up you know to drown them, only three of them. Now how many got out, I don't know, but only

three were rescued. And there were four in one group and three in another group. Now, they were never more than one or two miles apart of from each other at any time, but they couldn't see each other, but the blimp when it came out . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Spotted both.

Harry J. Kane:

Spotted both groups see, and in this fellow's report here . . . he's the guy--George Middleton-- that was the pilot of the blimp, and he did a remarkable job of navigating to locate them. When he found them, they were in two separate groups. In fact, in his report he picked the group that looked the stronger of the two and dropped a life raft to them, and instructed them some way--I don't know all the details--where the other group was and told them to try to paddle to get to the other group. They found the other group with help of the blimp, and they all got into the life raft. And then the blimp radioed and they sent a plane out to pick them up, and the sea plane landed and they got them all into the sea plane and then they flew back to the Norfolk Naval Station.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, how did you find out that they had been carried to Norfolk? How, how was this conveyed to you?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh, yes, excuse me. Well, first of all, nobody would give me credit for sinking the submarine. I hate to say this, but evidently there's an awful lot of rivalry between the different branches of the service, and I was in the Army Air Corps. Of course I was attached to the Marine Corps because I was at Cherry Point which was a Marine Corps station. They Navy was there and the Navy, to my knowledge, didn't care to say that the Army had sunk the submarine, or the Army Air Corps had sunk the submarine, and, they wouldn't say, you know, even though I told them that I'd sunk one and all that; they wouldn't believe me. And until they found the seven survivors two days later, they wouldn't.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then they did give credit after that?

Harry J. Kane:

Then they had to give me credit. It wasn't the case that they wanted to, they had to. But then see the submarine was sunk on the seventh of July and on the eighth they didn't tell me anything, and on the ninth

Donald R. Lennon:

You went back to your regular patrol?

Harry J. Kane:

Right, just as if nothing had happened, and then on the tenth or the eleventh, I can't remember exactly, but it was one day or the other, the squadron C.O. called me in and said, “We're going to Norfolk; we want you to go with us.” They took the whole crew together.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they tell you what you were going for?

Harry J. Kane:

Nope, they didn't tell us, just said we're going to Norfolk and we want you to go with us. So we went up and landed at Norfolk. The squadron C.O. flew the airplane; we just rode. They took me to a place that I know now is known as the dispensary, and they took me upstairs, and there were a whole batch of civilian men standing around with submachine guns. I figured they were FBI or G-men or whatever they call them, I don't know. They led me into a great big room, and there was this guy sitting in this chair in the middle of the room, and somebody introduced me. I don't remember exactly what they said, “This is the Captain of the German submarine; this is the pilot that was responsible for sinking you” or whatever. And this is the part I love. He was very badly sunburned.

Donald R. Lennon:

I bet.

Harry J. Kane:

That was the worst thing. See their head and shoulders were out in the sun all the time, but he stood up the best he could and came to attention and threw me a salute and said, “Congratulations, good attack.” And really, I mean it's just something that you just

can't ever forget. So that was the story and that's all there was to it back in 1942, and until I started looking in 1979, and found Horst Degen.

Donald R. Lennon:

On April the 13th, 1979 you wrote Senator Lowell Weicker and sent him a copy of a News and Observer clipping concerning German submarines that had been sunk off the North Carolina coast, and you asked for his assistance in getting more information about . . .

Harry J. Kane:

Yes and he sent me a letter, very quickly. I was impressed that it was customary in the Senate for one of the Senators to turn over to the Senator from a certain state any requests for information or help that came from somebody. Since I came from North Carolina, he turned the whole thing over Senator Jesse Helms from North Carolina. Senator Helms was a very big help to me. His office did take longer to answer then Senator Weicker's office did, but they finally worked quite hard on the thing and gave me an awful lot of information. It was through Senator Helms' office that I went from one thing to another, and finally I got in touch in the German Embassy in Washington.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, at the time until this, did you even know the number of the submarine that it was U-701?

Harry J. Kane:

I think I may have heard that it was a U-701, but I'm pretty sure that I must have known. I can't remember.

Donald R. Lennon:

At the time you were at the hospital there at Norfolk, what you quoted was the extent of your conversation with Captain Degen at the time?

Harry J. Kane:

Yes, that's all I knew at the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Ya'll just came on back to Cherry Point after that meeting?

Harry J. Kane:

Right, Cherry Point.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was nothing but the meeting.

Harry J. Kane:

Right, and I never knew any more about him until I found him in October of 1979.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you and your crew get any kind decoration or commendation?

Harry J. Kane:

Oh, yes, I'm sorry I forgot about that. Yes, we were all awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and I have a humorous thing that I'd like to add to that, speaking of decoration. I have official letters--and if you'd like to see them, I could get them for you--signed by an admiral which was the top man on the East Coast who was called the Eastern Sea Frontier, I believe. His name was Andrews, Admiral Adolphus Andrews, and I havethis is humorous I think, sad but humorous. I have an official letter from him saying that he recommends that the pilot of the aircraft involved in the U-701 incident--he didn't say the crew, he said the pilot--be decorated with the Navy Flying Cross. Now the humorous part is there ain't no such thing as a Navy Flying Cross, and therefore I never got one, but I did get the Distinguished Flying Cross. According to the Admiral, he evidently thought this was quite something and he recommended that I be designated for an additional award, which, since there wasn't any such thing, that I never could get it. I would have liked very much to have another decoration, and I was recommended for it, but I just never got it because there wasn't anything like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm surprised that they don't have one of for navy aviation.

Harry J. Kane:

No, the Distinguished Flying Cross is Navy, Marine Corps, Army, whatever. It's a quite high decoration.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

Harry J. Kane:

But, it's the same for any branch of the service. It has to do with flying, of course, you know.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

[End of Interview]

This is my grandfather I believe. My dad told me about Pa sinking the submarine. Pa didn't tell us grandkids much about the war but I do remember him telling us about running out of bombs and they rounded up all the beer bottles and dropped them because as they fall the whistle on the way down. Although I was it was a video, I am so glad this tape of his story is archived. Thank you so much!