| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #158 | |

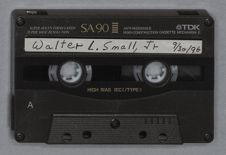

| RAdm. Walter L. Small, Jr. USN (Retired) | |

| USNA Class of 1938 | |

| September 30, 1996 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon. |

Donald R. Lennon:

Just go right ahead with your background if you will, Admiral.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

My boyhood in Elizabeth City was pretty much like many others of my era, in the late 1920s. I was born in 1916. I was a newspaper carrier for first the Norfolk Ledger Dispatch in Elizabeth City and then second the Daily Advance in Elizabeth City. At the age of about thirteen, I started working at Buxton White Sea Company on Saturdays during the summer. In the produce part of the summer, I worked in the warehouse that shipped fresh May peas and then potatoes. I really became a pretty strong, wiry young kid. I could, at age 15, pick up a hundred-pound sack of feed and put it over my head with no problem, which I can't do half that now.

After I finished the tenth grade, my family properly decided I needed a little broadening, so they sent me to prep school at Woodbury Forest, Virginia. I was very studious in those days. I worked hard and I got the idea of going to the Navy for two reasons. One, I had an uncle, my mother's sister's husband, who was a young junior grade lieutenant at that time. I thought he was a pretty good model, so that gave me the

idea. Then the Depression was on in the thirties. I thought two years of prep school was enough for my dad to finance. This gave me a financial incentive to go to the Naval Academy. My father said, “Well son, if you want to go to the Naval Academy, you may, but you may also go to the University of North Carolina and study law if you'd like.” He was a lawyer, had been a prosecuting attorney for the First Judicial District and then had become a superior court judge. His partner in lawwho I thought was a junior partner, but was actually a senior partner was J. C. B. Ehringhaus, who was the governor at that time. My father said, “If you really want to go to the Naval Academy, you're going to have to get your own appointment. I suggest that you write Senator Josiah Bailey,” which I did. I got an appointment and the year I finished Woodbury's I went to the Naval Academy. That's how my naval career came to be.

At that time, we had to have two years in the Fleet after graduation. My first ship was the USS PORTLAND.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's talk a little bit about the Naval Academy before we get to the PORTLAND. How did you react to the type of courses and class work at the Naval Academy? It's a little bit different from normal college schooling, I understand.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I would say yes and no. It's more technically oriented, but I didn't find it all that difficult. I had been very studious. I stood second in my class at Woodbury. I found the first year, especially the first half of the year, repetitious. I got out of my normal study habits a little bit. While I started off standing very high, over the course of the four years, my academic standing went down from near the top of the class to where I graduated at the middle of the class. It was just about exactly the middle, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the harassment that the plebes usually have to suffer through their first year?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

You hear a lot about it and how tough it is, especially with comparisons to West Point, VMI and the Citadel. I think at all of these schools--I know at the Naval Academy--you pretty much got what you asked for. I had a roommate who lightened my attitude towards life quite a bit. I had a pretty good hazing, but I must say I didn't get anymore than what I asked for. I had some classmates who went through there and never got their fanny frapped at all. I got mine frapped plenty, but I could have had it frapped a lot less if I behaved a little better. I knew that. I think it's a matter of the temperament of the individual and whether he wants to give them back a little sass or whether he wants to take it all. I figure the average American kid brought up in a free lifestyle--probably more so today than at my time--isn't oriented to the military training, saying “yes, sir” all the time, and learning what you think is a lot of useless drivel. There's an automatic reaction in some of the kids' minds, including mine. I think those who want to fall in line can and get along very nicely. Those who want to be a little bit renegade get what they ask for. That's how I would put that. I can go on with a few interesting little experiences if you'd like.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you have anything in particular that comes to mind, that you'd like to share with us, that would be . . . .

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Well, my roommate was more of a renegade than I was. I probably would have done better academically with a different roommate. That may not be saying much. Maybe I was too much of a follower at that time, rather than a leader. We went to the rifle range all through the first three years of the academy with rifle and pistol training. I

had made Expert rifle and just always missed Expert pistol by one or two points. My roommate couldn't hit the target for anything. He would shoot around the next target or shoot it into the ground. He would shoot in the air. He'd seldom hit the target. He finally said one day during our third year there, “God, I don't understand why I'm not doing better in this rifle.” I said, “Well, Charlie, it's very simple. All you do is line up the front sight with the rear sight and hold it steady. I bet you're jerking the trigger, instead of squeezing it.”

He said, “Oh, I squeeze the trigger, but what do you mean the front sight and the rear sight?” He had gone through three years of shooting the rifle and the pistol--because he hadn't listened to the instructions--thinking there was only one sight to line up--the rear sight--and then you just shot. As soon as he learned there was a front sight that he had to line up with the rear sight, he began to hit the target. Here we are in the third year out there on the rifle range. It was pure goofing off, so to speak. Of course, he was hazed more than I was, but he asked for it a lot more than I did. That's just an example of what crazy kids do when they don't listen. There's more to it than that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting. I know you were into some extra-curricular activities. You were big on wrestling and crew, were you not?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, I was in the lightweight crew. I was in the first team boat my freshman year, which we call plebe year. I also went out for wrestling. I was between two and three on the freshman squad. I went out youngster year, which is the sophomore year. I was doing pretty well in a match with a contestant one day. We had a heck of a good match. It was very close. After the match, I went to get up and couldn't straighten my knee. I popped the ligaments in my right knee. As a result, I ended up in a cast from the hip to the ankle

for about six weeks. During this time, I was hopping around to classes on one leg with another stick on the other side. I developed a good case of water on the left knee, so I was laid up from both knees. This ended both my wrestling and rowing career. Both of these sports are very dependent on knees working well. When I got on the PORTLAND, I was able to wrestle a little bit more. I did coach the wrestling team, but that damn knee kept going out on me for about ten or twelve years before it really got right again.

Donald R. Lennon:

That didn't affect your fitness?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It didn't after I got out of the cast and got it working again, which took a total of about two or three months. Then I got off of the so-called “sick squad,”--those who don't have to march in ranks to and from class and to meals. You just go down on your own--which has its advantage in a way--but also, it holds you back physically. After about ten years or so, my knee was really all right again. It would not go out anymore, but it did happen all through World War II.

Donald R. Lennon:

But there was no threat to them discharging you?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

No, there was no threat because it was gradually getting better. We were expanding and they needed people, rather than getting rid of people. You must realize as the Navy expands and contracts--it would be the same in any of the armed forces--it's a hiring and firing situation. You have RIF's (reduction in forces) in the Navy just like you do in General Motors or any other civilian industry. When you're expanding, you need people.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know a couple of years later, they were very severe on eye examinations. They would take you with a bum knee, but not with bad eyes.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

That's very true. They don't want you missing that plane coming in on your ship, when you are standing as officer of the deck keeping a sharp lookout.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other thoughts about your stay at the Academy?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Not offhand. Of course, I could go on about the regimented life and so forth, but there are plenty of stories about that. Everybody likes to write about that all the time. I would say there was nothing outstanding. Wait, there was one interesting thing. The colonial governor's mansion for Maryland is in Annapolis. The colonial governor was named Ogle. His residence became the governor's mansion of Maryland. The colonial mansion had been bought by a language professor named Cusaks, who taught Italian at the Naval Academy. He was deceased and his widow lived it in when we were there. During our second class year, my roommate, a friend across the hall, another guy and I went and rented out the whole ballroom of that old governor's mansion--one of the historical houses of Annapolis--for the whole year by pooling our resources, which were pretty meager. You didn't do that on Naval Academy pay. We had to get a little money from home and didn't tell our parents where we were spending this money. We had a very non-regulation delivery of little whiskey bottles to the side door. Also, we kept our phonograph and our stack of records, as well as fireplace wood when we needed it. We kept a fire going on the weekends and had a very good time there. Our dates frequently stayed there in the bedrooms with the chaperone upstairs and I don't mean the chaperone that traveled with them. Those days had passed. I mean, the chaperone was the one who owned the house, the widow of the professor. She had an adult daughter that lived there with her. That worked out very well.

In the second year of starting to rent this room again, the widow had a reception and invited the commandant of midshipmen and some of the Academy bigwigs. Also, she invited the Italian Ambassador, his daughter--Terry was her first name; I've forgotten her last name--and a couple of other young ladies. The widow invited us over to help entertain the young ladies. We played very innocently and got into the punch. The commandant, of course, noticed this. He was on the spot because drinking was absolutely non-regulation. However, he didn't want to create a problem with the hostess of the party and the Italian Ambassador who was there, so he didn't say anything. We went back to the Academy and nothing happened at first. In about a week, Mrs. Cusaks came around to us and said, “Young men, you know the talk is beginning to go around about what you all have been doing out here. I think we better call this thing off.” At that point, we had to give up the room and change our ways a bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was renting the room in violation of the regulations?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Not to my knowledge. The only thing we did in violation of regulations was to have a little bit of booze out there and to drink that punch. Frankly, I was smart enough not to drink that punch, but two of the four of us were not that smart and the commandant couldn't help but observe it. They had non-spiked punch there, too. Of course, all the adults knew the difference and so did we. Two of the gang were taking advantage of the situation.

Incidentally, that house--the first colonial governor's mansion--was bought by the founder of the Naval Academy Alumni Association. I was one of the very early members. I would guess I was probably one of the first dozen or two dozen of the members who contributed to the purchase of that house, which is now the headquarters

for the Naval Academy Alumni Association. That's just an interesting little side story. That's the only other thing that I remember as significant.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm surprised the state of Maryland doesn't try to take it over as a historical building.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It's a historical monument. It's registered. It's now a tax-exempt institution, although it was difficult to get it that way. It wasn't until, post World War II, late forties, maybe early fifties before it received tax-exempt status. As I recall, it was purchased in 1946, give or take a year or two.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you graduated in 1938, you were assigned to the heavy cruiser, PORTLAND, is that correct?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, that was one of the ten thousand ton treaty cruisers with the Japanese and British 5-5-3 ratio for the naval forces. This was an 8-inch cruiser with nine 8-inch guns.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the nature of your duty on the PORTLAND?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I was the anti-aircraft battery officer and had the maintenance of the eight 5-inch guns for anti-aircraft. These were, as well, I recall, 5-inch twenty-five guns. They had a heck of a concussion, because of the short barrel. We held the Fleet Gunnery School on our ship, because we had a pretty good fire control team. My job at battle stations was running one of two anti-aircraft directors. I taught as a young ensign the anti-aircraft fire control system.

Donald R. Lennon:

The PORTLAND was based in Long Beach the entire time you were on board?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

We were based there until late 1940, when we sent most of the Fleet from Long Beach to the Hawaiian Islands for a fleet exercise. They kept the Fleet in Honolulu after that. The exercise was a natural exercise. It might have been--I'm unqualified to say

this--but I assume that it was designed to get the Fleet out to the Central Pacific away from the West Coast to give the Japanese the subtle notice that we were not going to just stay on the West Coast and let them keep moving commercially and militarily through the western Pacific. It had no effect on the Japanese, until Pearl Harbor day. Of course, they knew where we had moved the Fleet. The result was when they did decide to move secretly, they did it on the great day that will live in infamy as Franklin Roosevelt called it, on December 7th.

Donald R. Lennon:

The PORTLAND from 1938 to 1940 was involved entirely in maneuvers and this type of activity?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

That's correct. We were training on the West Coast. We made one trip through the Canal to the East Coast and had a fleet exercise there because the war was coming along in the Atlantic as well. I don't recall whether this was before or after the neutrality patrol. I think it was before, because we gave England fifty destroyers and one submarine later, so it had to be before neutrality patrol. Then we went back to the Pacific. Pearl Harbor came after that exercise when we moved the Fleet to Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

Actually, your first two years were very routine.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

They were routine with peacetime training, saving fuel oil, exercising during the daytime, anchoring off of Catalina Island and Long Beach in Los Angeles at night to conserve fuel, pulling up the anchor and getting underway for exercise again in the morning. There was still a very meager budget for the Navy. That was the pre-World War II drill until I went to submarine school after two years in the Fleet.

Donald R. Lennon:

What made you decide that you wanted to be a submariner?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

That's an interesting short story. My girlfriend was back on the West Coast and I was out in Honolulu. Months were clicking by. We had some intentions of getting married, so I figured out the only way to get back to the States was to go to submarines or aviation. My roommate who was also the one I had all four years at the Academy, was on the same ship as I was. He was also in the same situation I was in. He put in for aviation and I put in for submarines. When he got back to the United States, he scrubbed his wedding. He didn't get married. I called up my girlfriend one evening from Honolulu. It was two and a half hours later than the West Coast at that time. She was out with some other guy who wasn't in Honolulu, so I proposed to her mother. Her mother accepted for her. My future wife came home that night, I guess, right at eleven thirty and found this note on her pillow that she's going to get married on June the twelfth. That's how she found about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, obviously, you had a good rapport with the mother.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, I had been over to their house many times for dinner. One time, when I was out of funds, I borrowed ten bucks from her dad to take her out for the evening to the Army/Navy Club or somewhere.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was she from California?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Her stepdad was in the Navy. Her father was lost when she was about eight years old. Her mother's second husband was a Naval officer, who was on one of the other cruisers. He was executive officer of the CHICAGO when I was on the PORTLAND. I had met my wife when she was on a date with a shipmate. I don't know whether it was a blind date or not, but I met her at a ship's dance. The other fellow was a friend of mine. I drove for the four of us. I had a car and he didn't. What it amounted to was then I started

dating her and he dropped by the wayside. She had five guys dating her at one time. Strangely enough, she happened to get proposals from all five during the same week.

Donald R. Lennon:

Goodness.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I guess I won the lottery.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your request for sub school was not for any burning desire to spend your career in submarines?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Well, I knew it was a little bit of extra pay and it was a way to get back. I also had figured out that there were three advanced fighting arms of the Fleet: aviation, submarines, and destroyers. Destroyers were considered advanced arms because they carried a lot of torpedoes and would dash out ahead of the main battle line. They would then launch their torpedoes and hope to put an attrition into the enemy battle line before the big confrontation between the two battle lines. That was the theory of the war path anyway. Of the three arms, submarines appealed to me the most. I figured being a part of one of the arms was essential to the career of a young officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you ever been in a submarine?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I had only been in one in the Chesapeake Bay for a few days--one week really. I probably went out on the sub three days out of that five and made a few dives.

Donald R. Lennon:

It didn't bother you being in such close quarters then?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It doesn't bother me at all. I dug caves as a kid in the ground, so confinement didn't bother me a bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Has there been much of a problem in the Navy with officers being assigned to submarines and finding out that they just could not take the close surroundings?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

There have been very little problems. Before World War II, you didn't get into submarines unless you volunteered as I did. During World War II, with the big expansion coming on, a few officers and enlisted men were assigned to submarines without volunteering. By that time, we had set up the psychological evaluation where the men were screened by medical officers and psychiatrists. It was a pretty effective system. We had very little problem with claustrophobic people during the war. I don't recall any on my sub and I've heard of less than a handful. I really didn't consider it a problem at all. I think the medical screening was a contributing factor, but I think we could have lived without it fairly well, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

After submarine school, you were assigned to an R-3. In your paper, you talk a bit about the R-3 and the disadvantages of that type of a submarine. Are there any other anecdotes or stories with regard to the R-3?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

In the R-3, I talked about pigboat sailors and how we really worked hard to earn that name. We all deserved that name. One other anecdote comes to mind was, after collecting twelve of these old war boats together to form a squadron, we were assigned to an old mother ship--a submarine tender--the BEAVER. The squadron commander was on the BEAVER. We got the whole squadron together and went down to Panama about early December of 1940. We relieved an S-boat squadron that went out to the Pacific to strengthen the Pacific Fleet. After we got to Panama, but before going into a routine scheduled overhaul, we took what was called an experimental depth-charging. In this drill, the submarine would submerge and keep its periscope up. The destroyer, who is going to depth-charge the sub, would get a major distance away--two hundred yards on the beam, as I recall--and our periscope depth was about thirty-eight feet then. They were

very small boats compared to subs today and even compared to World War II subs. The sub crew consisted of thirty-eight men and three officers. I was the diving officer. When the depth charges went off--they were set for a hundred feet--it made quite a rattle in the boat. The diving gear then was electrically operated, later it changed to hydraulics in the Fleet boats. The electrical circuits to the bow and stern planes shorted out and were running backwards so that when you put them where you thought they would be on dive, they were on rise and vice versa. We started going the wrong way, in other words down, rather rapidly. We blew our tanks, came to the surface, knew we had problems with the diving gear, and had to return to port, which we did. After making a list of all the casualties and with the overhaul scheduled anyway, we went on to the ____ Shipyard in Panama and went into dry-dock. I happened to be standing behind one of the seamen with a paint scraper--not a chipping hammer chipping--but scraping along the metal hull. This paint scraper got caught in a piece of bitumastic, which is a tough covering preservative used to prevent rust on the hull. For this vessel being an old World War I design, which was completed after World War I and put in the Reserve Fleet, it was a pretty rusty hull. The seaman pulled off this piece of bitumastic. We looked right through the pressure hull into the submarine. We knew we were in trouble and we also knew we had been damn lucky to come out of that depth charging, because there was nothing holding us together in these thin little spots, except a little bit of rust and some tar. We then pulled off the mufflers as well as all of the superstructure around the conning tower, including places that were very tiny and hard to get to. A human being could hardly get his arm in there to do any maintenance work anyway. We drill tested by just drilling holes in the hull to see how thick it was. We found numerous places that

were as thin as a thirty-secondth of an inch and others a sixteenth of an inch. As a result, we had to cut out sections of the hull and put in new steel plates. The areas that were easier to get to were maintained through the years and the thickness in those areas would be from three-eighths of an inch to half an inch thick.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these World War 1 subs double-hulled or triple-hulled or are you just talking about a single outer skin and that's all that was protecting you.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

They were all single-hulls and that's all that protected us. Now, even in the double-hulled boats, there's only one layer of protection and that's the inner hull. The outer hull is a very thin hull, which is comparable to a surface ship's tank. The ship carries the fuel in those tanks. Some of the tanks were convertible, to carry either salt water or fuel. We called these reserve fuel tanks, but the others had to have something in them or the sea pressure would crush them instantly. The tanks would not take depth at all. They especially would not take depth charges if they were empty. Therefore, all the stress is on the inner hull, which is a water-tight hull.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was the outer hull on these that was so thin.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

This is the outer hull, the only hull we had.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you been in a wartime situation with that or for any reason had you had to dive with it?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Any depth charges or violent shakes closer than what we went through on that experiment would have been fatal, no doubt about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you said that the equipment was reading reverse and you were diving, did you realize that you were diving and intentionally came up or did it automatically blow the tanks?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

We realized we were diving and I gave the orders to blow the tanks. I was the diving officer. There's no doubt that when you're trying to come up and you're going down, something is wrong. We figured out rather rapidly what it was. You don't have to be a great scientist to figure that one out. There are a few seconds of tenseness when you say, “Hey, what's going on here?”

Donald R. Lennon:

But had you not done that when you did, the forces probably would have caved in the hull.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, it would have. Another interesting event on that R-boat was when the French had surrendered. A few of their ships--three cruisers as I recall--escaped and did not turn themselves over with the Vichy French to the Germans. Instead, they went down to Martinique. We wanted to keep them in Martinique. I believe it was a few destroyers, at least more than two. We did not want to go back and join the French who had surrendered to Hitler, so we moved a division of submarines--six of them--out to St. Thomas. I was in that first group to go to St. Thomas. Our mission was, of course, a threat to keep the French ships in Martinique, which is quite a distance away. It was purely a paper threat. We didn't make patrols off of Martinique to keep them in there. We didn't make our presence known off of Martinique or anything like that. It was basically still training and drilling at an advanced base closer to Martinique. We also served as paper defense for the Panama Canal. We established that base at St. Thomas where some construction had already started. The Bachelor Officers' Quarters was partially completed. The enlisted barracks were partially completed, but that was about it. The pier was there and nothing else, but construction kept going while we were there. Incidentally, all thirty-eight men, who made up the crew, were old Reservists, who had

retired from the Navy and called back to man the expanding Fleet built up during pre-World War II. Roosevelt was pretty astute in seeing this and doing it subtly and quietly. Our captain was a bit of a milquetoast. Our executive officer, who had been an excellent man out of the class of 1932, was relieved to go to a new boat of his own to take command. Our new exec was a member of the United States Naval Academy class of 1933. Now, [class of] 1933 graduated in the height of the Depression. The United States was cutting down on the Navy so fiercely that it only graduated the top portion of the class. As I recall, it may have been the top half. It might have been a little bit less than that. The rest went out to civilian life. As the war came closer, about 1937, we called back in the bottom half of the class of 1933. They were called 1933-B. You had 1933-A and 1933-B with 1933-B having a lower precedence. I think the ranks were sandwiched between 1935 and 1936. I could be incorrect on that. A few did not come back in, for reasons I've forgotten. They came in later and were 1933-C. They ranked between 1937 and 1938 or maybe 1936 and 1937, somewhere along in there. Our new exec was a member of 1933-C. He had Naval Academy experience, but not as much sea experience as I had had.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had nothing between 1933 and 1940 at all.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

He had been to sub school. He had been to sub school, but he was not sure of himself. I don't mean this as criticizing him. I just mean this as a natural situation of circumstance. The crew was very upset about this. As a result, the senior torpedoman, the chief engineman, and the chief electrician formed--and these are the three leading men on the boat--a self-appointed committee and came to me one time. I never did mention this to the captain or anyone. They said, “If war comes, you're going to have to take

command of this ship.” I was a bright young ensign, with only a year's experience in submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you third in command?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

There were three officers on board. I was number three. We later got an ensign, who came aboard as number four. He took over some of the mundane duties like commissary and communications. I think that's about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you react to their appeal or their warning that you would have to take command?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I really thought the best thing to do was to say nothing and see how the situation progressed. That's just what I did. It really turned out all right because we turned that sub over to the British. In the transfer of the destroyers, we also gave a few subs away. Oddly enough, I would have agreed with the crew that we had a milquetoast captain. However, he turned out to be pretty successful in World War II, which fooled me. I think he would have also fooled those chiefs, too, and most of that crew. Out of the thirty-eight men, all but six were old fleet reservists called back in, who had been in submarines for years. They took people from thirty-eight to forty-five years old, who had a lot of service. In fact, they probably had more service than the captain.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those particular subs, with them not having air conditioning and not being able to generate their own fresh water, you hear references to a happy ship or an unhappy ship. How did you deal psychologically? Did you think you had made a mistake in going into submarines or were you? . . . .

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

No, I don't think we felt that we had made mistake in going into subs. I do think we felt that, “Hey, what's the purpose of these things in World War II? Maybe they can

be used for training out of New London, Connecticut and Long Island Sound and that's about all they're good for.” In my opinion, that was all they were good for. That's the way we ended up using them. We sent them up to New London and used them as school boats in World War II, eventually. We kept some in Key West. We lost one in Key West, the R-12.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did the British use them for when the boats were turned over to them?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

They used them as any other submarine in World War II, but they didn't take any other than that one.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, okay.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

We gave another one to the Poles. That was an S-boat, which was much better than the R-boat. There might have been one or two follow-ons, but there were very few, if anymore at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other thoughts concerning the R-3 or your duties there before we move on?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

No, I don't think so. I think that covers that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your crowning glory during the war years were your war patrols on the FLYING FISH.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, that was my first sub. I went from the R-3 to the FLYING FISH, the first ship commissioned in World War II. We all remember that we were commissioned right after December seventh. We worked eighteen hours a day, literally. We were commissioned on December 10 and I will never forget fueling the ship. The ship was very light. All the fuel tanks were empty. When we fueled up the ship, what came up alongside the pier, but ten tanker cars pushed by a locomotive. We emptied every tanker car, all ten of them. That was very impressive to me--the amount of fuel that subs hold.

That's what fleet subs carry. I forget the number of gallons, but those tanker cars were not the big tanker cars you see on the railroads today. They were considerably smaller. I would estimate half that size, but maybe not that big.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long could a sub operate on one tank of fuel?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

You mean the World War II subs?

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, such as the FLYING FISH, how long could you patrol without having to have your fuel replenished?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Of course, it's a matter of how fast you run and how far you run. The normal routine would be a cruise from Pearl Harbor, which stopped at Midway where we topped off the fuel. Essentially, we really departed from Midway. It would take us ten days to go from Midway to the patrol station. We would be on patrol for a month. Then we would take a trip back to Midway for more fuel. If we were going back to Pearl, we would go on back to Pearl for overhaul. We might be stopping at Midway for refueling.

Donald R. Lennon:

Normally, you expect to be able to be at sea for six weeks or more, probably, on a tank.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I would say closer to seven weeks or fifty to sixty days. Seven weeks is forty-nine days. Fifty to sixty days would be your normal patrol. If you used up all your torpedoes and had no ammunition, you'd come back early. I do recall one time that we carried just over one hundred thousand gallons of fuel. We came back to Pearl one time with less than four thousand gallons, which was a pretty close call. So you learn to conserve fuel by patrolling very slowly at night only covering small areas, but staying in shipping lanes where you would expect to find shipping vessels.

Donald R. Lennon:

Despite the fact that you were in the Pacific, I believe your first encounter with enemy was not with the Japanese, but with a German submarine.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Correct.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was not as satisfying an experience as you would have hoped for?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I think I covered that to a degree in this little paper. Let's stop a minute and let me see what I said.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was primarily a situation where the torpedoes were running too deep and they were going beneath the ships that you were trying to torpedo.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

At that time, we didn't know they were running too deep. We didn't know we had any torpedo problems at all. The reason we didn't get a shot at him was that he had the advantage on us. The first thing we needed to do was to get out of there and preserve ourselves. Then we hoped to get the advantage on him. That's why we dived and waited until after dark. We hoped he would surface first, so we would see him and get a shot at him. Either he had opened the range and surfaced out of sight or he stayed submerged until we were out of sight. We surfaced and off we went. There was no more contact after that initial contact. You never want to hang around when the other guy has the advantage. That's why we left.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's probably a good thing you did, based on your later experience.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I would say so, yes, based on the later experience of the FISH. The FISH, before I took command of it, sank three submarines in one patrol by having the advantage of being there first and seeing the Japanese subs first. This was a record for World War II, given to the skipper of the FISH before me.

Donald R. Lennon:

On the early patrols, are there any comments that you want to make with regard to the torpedo problems? That was primarily the first patrol because the torpedo problems were worked out, later, I take.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It was the first patrol I noticed the most because we didn't know why we weren't getting hits. We had fired several torpedoes at one ship coming out of Wake. I think I covered that in the written précis of my experiences during the war that I gave you. The thing that bothered me was after every attack, when we didn't have any success, I got chewed out. However, the fire control officer, having charge of the torpedoes, the torpedo fire control system, and the torpedo data computer was not chewed out. I would say, “Well, let's sit down and analyze this. Maybe we can see what is wrong. We ought to be getting hits.” I guess the captain had a feeling, subconsciously or consciously, that I was trying to point the finger at him, which wasn't the case.

I figured we the officers should sit down and brainstorm about this to see if we can find out what's going wrong. Anyway, the captain didn't see it that way. We had no conferences and no talking it over. I tried to analyze it myself the best way I could. Finally, during our last attack on the first patrol, a Japanese merchant ship was coming out of the northern port of what was then Formosa and now Taiwan. He was not zigzagging out of port. Instead, he was heading on a straight course roughly north. We were near his path. We crossed his path, looked straight down his mast, and measured his course right on. We couldn't miss it since we pulled off to the side about eight hundred to a thousand yards. We waited until his bearing was about seventy degrees on his beam so the torpedo would be hitting it at about ninety degrees. It was the perfect firing situation. You couldn't have it any better. We fired, I think, three torpedoes at him and

didn't get any hits. The skipper turned to me and said, “Now analyze that one you son of a bitch.” Then I really knew that he had thought that I was blaming him all the time, but I was really saying, “Hey, we need to find out what's going wrong here.” They were different reactions of different people in the same situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

After the earlier misses, he didn't try to figure out why they were missing? Would he just shrug it off and think better luck next time?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I'm sure the question “What's wrong?” had to be going through his mind, too. He didn't take my suggestions the right way, in my opinion.

Donald R. Lennon:

He didn't communicate with his officers very well.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

That's correct. He did not. I think we could have maybe solved a lot of problems with better communication but that's a problem with human beings throughout the world. That's not just on submarines, by God. That includes mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and parents and children.

I guess it took quite a while before there was enough data for us to figure out what the problem was, even though many boats experienced similar problems. We also had problems because we had two Submarine Force Pacific commanders at the time. The first was Admiral Winters, who was killed in an airplane crash. The second was Admiral Lockwood. We had to convince the people in Washington that there was really something wrong with those torpedoes. We also had to convince the design people who developed the sub as well as those who manufactured it in Newport. It was very hard to convince these guys that something was wrong with their product.

Finally, we solved some of the problems by conducting our own tests at Pearl Harbor. The running deep problem was solved at Newport by putting nets up and

shooting the torpedoes through the nets as they ran down the range. After shooting, they measured how deep they were running versus the depth set on the torpedo. Once that problem was solved, we still had the problem of no hits. We found out that the magnetic detonator wasn't working. Then we were directed to shoot to hit and make contact. Once that started, we still weren't getting the proper explosions, but COMSUBPAC, Admiral Lockwood and his staff observed that those torpedoes shot at sharper angles were doing better than those shot abeam or hitting head on. They said it had to do something with the impact being a harder impact when you hit the target head on. They took warheads without the detonator and dropped them into a concrete block from towers measured for the height to give them the same speed of the force as the torpedo hitting the side of a ship. Then they would open it up and find the torpex, the explosive element of the torpedo, was crushing in on the booster and the detonator before the mechanism had time to react. Therefore, they were all duds when they hit broadside.

Our orders at one time were to shoot at sharp angles. As I recall, the shots had to be more than forty-five degrees on the bow or stern. Also, we were not to shoot deeper than ten feet above the desired running depth. This is the most difficult attack you can make because you foreshortened the length of the ship. The second thing is that your angle of attack is sharper and the ship you are attacking has less of a turn to make to go between the wakes of the torpedo spread. You put those factors together and it's a pretty hard shot to make. We were automatically handicapped until this problem was solved. COMSUBPAC, with its own self-made experiment, discovered the problem in Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

On that first patrol, when you were shooting and getting no results, did the FLYING FISH come under attack at any point? In other words, were you depth-charged?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I don't recall it. I would really have to go back to the patrol report. I'll be eighty next month and my mind. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking that the first time that you were actually engaged and came under fire would have been one of those traumatic events that would stand out more than later attacks.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Well, we had been experimentally depth-charged in the R-boat. We also had gone through it in the FLYING FISH.

Donald R. Lennon:

Isn't that a little bit different? You know those experimental depth charges are going to be far enough from you that they aren't going to severely damage the ship. You feel like you're safe in there when they're just experimenting like that, but when the Japanese are dropping the depth charges on you, I would think that it would be a slightly different sensation.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

You are correct, but you can judge the distance by the amount of shaking you get and the noise from the bang. There is a sound intensity. I'm sure on my first patrol, we didn't have anything worse than those experimental depth charges. I cannot tell you that we didn't hear some Japanese depth charges that were aimed at us, but none were close enough to worry about them.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the paper, you mentioned the second patrol as at Truk in the mid-Pacific, but I don't recall that you had much to say about the patrols from the second through the fifth. Was there anything in particular on those war patrols that needs to be recounted?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, the second patrol was the one off Truk. A Japanese Battleship was laid up for quite a while there. Intelligence could never find it, so we assumed it was still in Truk, undergoing repairs. We took some depth charges after withdrawing from that patrol. That night is when and where we shot the torpedo into the tube. We had to come back to Pearl. I think that is covered in the paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, that is. Then you jump to the sixth patrol after that, I believe.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I covered the rest rather routinely. On the third patrol, we went to one of the islands for a short time. I forget which one. Then we moved down to Guadalcanal and were in the Slot between two of the Solomon Islands, northwest of Guadalcanal. I think their names are San Cristobal and Georgia, I believe those are the two islands. I would have to refer to a map to be sure, which I don't have here. At this time, we had one of the first radars installed on submarines. Destroyers were running down on a so-called midnight run to resupply the Japanese with some troops and supplies in Guadalcanal. We got the blips on the radar and I can't be positive of this, but I think it was raining that night. It was very dark. We came in under the destroyer as he approached. We were not totally surfaced, but our hatches closed were trimmed down and we used the radar. The top of the shears is level (?) with the radar up there. We used the radar bearings and ranges to get a good tracking solution. I was on the torpedo data computer. We shot at him and think we got one or two hits. I have forgotten which it was. He disappeared from the radar scope. He just slowly disappeared. It was certainly an apparent sinking and was credited as the first pure radar fire control sinking of World War II, which is interesting for that patrol.

After that patrol, we went on down to Brisbane for overhaul and spent Christmas of 1942 in Brisbane. We came back for the patrol by the Marianas Islands. We had the same skipper, but a new executive officer. The executive officer was Reuben Whitaker, who was a very fine officer. After this patrol with us, he got his own command and later became an admiral. This time while we were off the Marianas, we found a ship that had anchored inside Guam's harbor. The harbor has a small entrance because there is a coral reef around the rest of the harbor. The boat was anchored so that the reef was between us and the harbor. The water depth drops off very rapidly around Guam. We could get in very close to the reef. We got about eight hundred yards off the reef and fired a torpedo at the ship. It hit the reef and made a tremendous explosion. We fired the second torpedo shortly behind it on the same course with no spread. It ran right into the harbor. It must have gone right through the hole the first torpedo blew and hit the damn ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Goodness gracious.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

You might call it luck. You might call it good thinking on the skipper's part. Anyway, it worked.

Donald R. Lennon:

The torpedoes were shot one behind the other before the ship had a chance to move or do anything. Of course the ship was in anchor.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It could have been thirty seconds, apart, but in thirty seconds a ship can't get his anchor up and move anywhere.

Donald R. Lennon:

The first torpedo blew a path right through the reef.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

The first torpedo blew right through the coral barrier. The second torpedo had to go right through that hole. It was a unique situation. On that patrol, we went up to Tinian, which is the next island north. It has an open roadstead with no good harbor. We

had a big airfield there later after we took back Guam and the rest of the Marianas Islands from the Japanese. This Japanese ship was supplying the garrison on Tinian and they had the open roadstead. We just made a nice approach at this one. It was probably the easiest shot we ever had and got him with no trouble. That's really all I remember unique about that patrol.

Then we went back to Pearl. We ended up in Midway, I think, that time. I became exec. and made the fifth patrol off of northern Japan, northern Honshu and southern Hokkaido. I think that one is well written up in here in the paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had your relationship with the CO improved or is this the same CO?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

This was the same CO. One little experience with him was when we were coming back from the second patrol; we had the torpedo fire into the outer door. He was so angry. He called all of us into the wardroom after getting safely away from Japanese air cover. The only one not there was the officer of the deck. He read us the riot act. He said, “I'm going to kick every goddamn one of you off this ship as soon as I get back to Pearl Harbor.” He damn well near did. I was one of the unfortunate who survived.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why was he angry with the officers?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I still don't understand to this day. I cannot give you the answer, but that was his reaction.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it have to do with the torpedo problem?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Perhaps, I don't know. I cannot answer that question. In my mind, it was unreasonable. In my mind, I would have loved to have been kicked off at that time, but I didn't make the grade. I stayed on there longer than he did. I had two other COs on the

same ship. I made eight patrols on the FLYING FISH. My first CO was a dedicated individual, but he was extremely difficult.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's talk about when that torpedo jammed in behind the other. That was kind of some heroic effort on the part of several of you to save the ship in that situation, wasn't it?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes, in a way it was, but you had no other choice. Somebody had to do it. To be honest with you, there was another torpedo officer. I had been relieved of torpedoes, but I knew more about that ship than anybody else on board, as a whole. I knew if we were going to get the torpedo out of there, there were only two of us who could do it: the chief auxiliaryman and me. I volunteered and the Captain said, “Fine.” He wanted to get it out of there, too. He knew we had to get it out of there. We broke out the blueprints. I got the chief auxiliaryman up, along with another torpedoman. We went over exactly what we were going to do, the tools we were going to need and how we were going to go about it. There was a lot of speculation about what was holding the torpedo in there. It was not just one torpedo jammed against the other. It was that the torpedo in the tube had been fired into the outer door while the outer door was shut. As a result, the outer door sprung open and the tube flooded. As we moved through the water, the water would swish in and out of the tube. Eventually the propeller, which was a little impeller under the warhead, would arm the warhead by packing the booster detonator up into the warhead. After the torpedo was armed, if the sub was jarred or hit a big wave in a storm, the torpedo would explode and there goes our sub.

Donald R. Lennon:

The greater danger was the torpedo exploding rather than the ship taking on too much water.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

If the torpedo had been armed correctly, it would have sunk. I was on the tank with the auxiliarymen unjamming the torpedo. Meanwhile, other people on the sub had to go outside the sub and take the cover off the after tank, which is only about a foot above the water line. Then they had to get in the tank, so they could take off the housing in order to free the guide stud that goes through the guide slot to guide the torpedo out smoothly. By doing this, they would unjam the torpedo. This is where we were in the after tank, taking off the housing to get the guide stud off the torpedo, which was all bent up. The people in the after room included the present torpedo officer, who had taken over that position from me, and the executive officer, who was a nice guy. Also, the chief torpedoman was also present. In the best of experiences, they should have been capable of doing their jobs. However, to be honest with you, they just goofed off. They weren't prepared and couldn't get the torpedo back in far enough to get the door shut. Therefore, we now had both doors open on the torpedo tube with water pouring into the submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you suppose that's who the skipper was directing his remarks at; rather than all of you.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I don't know. I cannot answer that. I can just tell you the experience. Only he can answer that and he's deceased.

Donald R. Lennon:

He never said, “Good job,” huh?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Hell, no.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your sixth patrol is the one, I think, you covered very well. It was the one where you were severely depth-charged in the Taiwan area, was it not?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

No. The severe depth charge was on the FISH.

Donald R. Lennon:

Okay, you were depth-charged on the sixth patrol. Maybe it wasn't that same one.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

You are right. It was the sixth patrol. We got a good depth-charging on that one. You're right. That's when the division commander came aboard and relieved the skipper. Lieutenant Commander Glynn Donaho was relieved by Captain Frank Watkins. Frank Watkins was the division commander, who wanted to make a war patrol. He was the first division commander to take a submarine war patrol. Several others did after that. He was completely competent, sharp as could be, and a very fine skipper. He was also aggressive. We had to try to hold him back.

We got a contact going into--I think it is now called Keelung--the port on the west coast of Formosa four-fifths of the way down the island on the west side, which was the China Sea side. There is a big shipbuilding port down there. There was flat calm water, with no wind and a glassy top surface. We were using our speed to get closer and then we would back down to slow before sending up the periscope where we could shorten the range and shorten the torpedo run. These were good tactics if you have a choppy sea and some wind. The tactics aren't worth a damn in glassy water, because when you back down or slow down, it sends up a swirl to the surface. Exactly who spotted the swirl, I don't know, but we left a swirl and apparently a plane must have spotted it. The next thing we knew was bam, bam, bam. The depth charges were very close. That broke off our attack and frustrated us because we didn't get anything that time. However, we had a moderately successful run. That was the only error that I think we made during that patrol. You can be overly aggressive and make mistakes just as well as being overcautious and making mistakes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I believe you covered the seventh patrol fairly well. That is when you were at the Palau Islands and chased a convoy for seventy-two hours with great frustration, I think. I don't know whether there is anything about that. . . .

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

There was great frustration and great fatigue.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's right. You had no sleep at all during that time, did you?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Correct.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was still part of that seventh patrol when you had the problem with the battery explosion in the torpedo tube?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I think it was the seventh, if that's what my report says. When I wrote this paper, my memory was a little better than it is now. I was a little younger.

Donald R. Lennon:

That incident sounded like that had potential for having grave consequences.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It could have been disastrous, too. We had have lots of close calls. It was unique to have to pull the torpedo out of the tube and find the torpex broken up. Thank God, it didn't explode. Then I had to send for buckets of fresh water and scoop the torpex up in my hands. I had to put it in the fresh water to cool it and make sure it would be safe from there on. When we opened that tube--I think I mentioned this--the hydrogen sulfide stench through the boat was terrific.

Donald R. Lennon:

It tarnished all the. . . .

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It turned every piece of metal in the boat a dark brown within seconds.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did it do to your lungs?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It gave all of us some bad headaches. I don't know what the hell it did to our lungs. I could not see that or feel it, but I do know that I could smell it. Within minutes,

everybody had a headache. When it was safe to do so, we surfaced and changed the air in the boat.

Some of these things are interesting to look back upon. It's nice to be able to look back on them, too. I would not volunteer for some of the patrols again. I didn't volunteer that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

It seems like there are just about as many incidents where you were in imminent danger from internal situations as you were from external depth-charging or something of that nature?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I don't think that's quite right. I think the internal situations stand out in your mind. The external situations are beyond your control, but so are some of these. You take the external situations as a matter of warfare. If the internal ones are not too severe, they really fade into the background of your memory. Now the severe ones, which I've mentioned in this little précis, they stand out quite vividly. I think it's a matter of severity as much as anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then your eighth patrol was in the area between Taiwan and China, where you spent ten torpedoes trying to sink a tanker.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

We finally got it, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

Anything at all with regard to these eight patrols on the FLYING FISH that has not been covered either in your written account of today that needs to be explained a bit more or particular anecdotes with regard to it? Anything concerning the personnel aboard the ship?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Well, I told you the story about having to put a man in the brig. I don't know whether you want me to go through that or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was on the FLYING FISH?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It was the FLYING FISH. That was the sixth patrol.

Donald R. Lennon:

You might want to touch on that just a little bit.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Well, the division commander, Captain Watkinswho later became an admiral--had come on board as the skipper. We were down to one wardroom steward. We normally carried three, but we figured two would be sufficient. We picked up a volunteer off the island of Midway, who had not been to submarine school and really knew nothing about submarines. Then again, he really didn't have to. We could handle that. As a matter of fact, we were used to getting one third of a new crew after every patrol anyway, because one third went back to new constructions when they were expanding the fleet. This fellow was about six-foot-two. He wasn't heavy set, but being six-two, a 185-195 lb. man is not necessarily heavy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What is the ceiling space in one of those submarines?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It's variable. In the wardroom you, can stand up. That's where he worked. In the forward and after torpedo rooms you can stand up, but some places you cannot. You do a lot of ducking for overhead boilers and that kind of thing. The taller you are, the tougher it is to go through the hatches and the slower you get through. That's an important comment, because the taller you are, the slower you go through the hatch.

The other steward was a first class Guamanian. This great big black fellow did not take kindly to working for a little five-foot-four first class Guamanian when he was a seaman in effect with no rating. About the fourth day out of Midway, we were all in the wardroom having supper. Suddenly the Guamanian, the senior steward, dashed by the wardroom door and right behind him came this big black guy with the biggest butcher

knife you'd ever seen--the biggest one we had in the wardroom--chasing the Guamanian. The Guamanian, being little and agile, got through the hatch. Those hatches are probably three feet tall. This six-foot-two man was trying to get through after a five-four man. The five-four man got through quite easily. The other guy slowed down, which gave the Guamanian a step or two lead. By going through the control room and through the second hatch, he gained some more. One section of the crew was at dinner. We had to eat in three sections because of the large size of the crew and the small size of the dining room. He called to the shipmates that he was being chased by this new steward. As the second steward ran through the crew's quarters, the crew tackled him and got the knife away from him. This was the first incident we had had like this. We held mast on the steward. The captain said, “What am I going to do with him?”

I said, “Captain, you've got to put him the brig.”

He said, “We don't have a brig.” The Navy had rewritten Navy Regs before World War II to be more humanitarian, to make it tougher to convict people, and to make better treatment be given to people in the brigs. You had to have an authorized brig. You had to have a guard. You had to do all those things, which is impossible in a submarine. There's no space for a brig. It's not built into the ship. He said, “We don't have a brig.”

I said, “Well, we can designate one. This is wartime. You have practically unlimited powers and you've got to exercise it. We can't have the crew fighting and chasing each other around with butcher knives. It might be just this one incident; but if the crew sees one guy get away with it, the next time they get disgruntled, they will do it as well. You've got to stamp it out in a hurry.” He reluctantly held mast. He gave the

steward--the black fellow--three days on bread and water. He designated at my suggestion the pump room as the brig. The pump room is under the control room. That's where the big ship control watch was stationed. It was just overcrowded with the number of people in there: the radar detector operator, the bow planesman and the stern planesman, the man on the air manifold, pump manifold man, the chief of the boat, and the hydraulic manifold man. There were just a lot of people in a small place. The chief of the boat normally stands on the hatch to go to the pump room. He has to move off station to let you go in and out of the pump room. The heavy air compressors, the low pressure blowers, the air conditioning equipment, the refrigeration equipment, and mostly auxiliary machines were located in the pump room.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's probably pretty noisy down there too, isn't it?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It's noisy, hot and nasty. The space between machinery is probably about fourteen inches, with steel floor plates. There was no place to sleep and you couldn't put a bunk down there if you wanted to. It's a miserable place. This was late in the evening after dinner. We held mast and put him in the brig in the pump room. He slept on those cold steel floor plates that night. The next morning we were making the early morning trim dive after running on the surface all night and using up fuel. Your trim changes a little bit. You want to readjust, so you will have a good trim all day running toward Japan, getting closer to the patrol station for the wartime patrol. Under Japanese air cover, you might have to dive anytime. Therefore, we made a trim dive every morning to be sure we were in shape. On this trim dive, this steward had never been down there before. It was noisy. You also have a little water in the bilges from minor leaks and hydraulic drips. That (?) tank, which bends into those bilges, spews saltwater all around the pump room.

It's quite an experience if you haven't been down there, especially if you have not been on a sub but only three days in your life. He had had no subschool training. This frightened this steward so much, that he headed up out of the pumproom and the chief was standing on the hatch cover. He hit his head on the hatch and knocked himself out. He crumpled down in a heap at the foot of the ladder. After we leveled, we went down and he was coming to. We brought him up out of the pump room. Literally, I have never seen such an ashen-colored Negro in my life. He was so pathetic and the captain felt so sorry for him. He said, “We've got to do something. We can't put him back down there again.”

“Well, captain, let's hold a special mast. He hasn't requested a mast. You can't call it a request mast. Just call it a special mast and do what you think is right.” The captain held special mast the next day. The steward had a bandage on his head from where we had to shave the hair off to stitch up the gash. He looked in the mirror and that frightened him some more, I think. The captain commuted his sentence, but put him on probation for the rest of the patrol. He was a good sailor from there on for the rest of the patrol. He had learned his lesson and learned it well. He didn't create any more trouble. I don't mean he was the best sharpest sailor you could imagine, but he did the best he could for his ability. We put him off back on Midway, which is where he belonged in my opinionthinking that he's not really going to be a submarine sailor, but he loved that sub. He was a war hero. He was the first one down to meet us every time we came into Midway. He would catch the first line over and put it on the pier. He was the last one down to see us off every time. He would throw the last line off and wave good-bye to his

old buddies going back out to war again. It was quite an instant change in a guy's character. I've never seen such a unique change in my life.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting. Was there some particular incident that had set him off that had caused him to go after the other man with the butcher knife?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

What it was, I have no idea.

Donald R. Lennon:

He never apologized or tried to explain why he did it?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

No, I would assume this chief steward told him to do something he damn well didn't want to do and he wasn't going to take it anymore. He took out after him.

Donald R. Lennon:

After your eighth patrol, you were sent to new construction on the FISH, which I believe you cover in your paper. You talk about joining in the wolfpack operations off of the Philippines. It was at this point that you suffered the severe depth charges that sounded rather extraordinary. Are there any other details of that attack that would be worth recording or is that pretty much covered?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

I think it is fairly well covered. I must say, you cannot come closer to losing a submarine than we did without losing it. It was touch and go. We were very, very fortunate to recover from that. The skipper was good under that circumstance. In my opinion, he was great in port and a good administrator. He was a fine, handsome, big guy, who had been a football player, and married a Hollywood beauty. When he went to sea, though, he got very nervous and became over-cautious. He was not aggressive at all.

I will never forget one experience where we had some contacts around and some pinging. It wasn't immediately after this depth charge attack, but it was soon thereafter. He didn't want to surface at night. We have to get our batteries charged for the next day or we're going to be dead. There were a few rain squalls going around and they'd get

something on radar and sonar. They'd say, “Well, it sounds like a rainstorm, but I'm not sure.” He didn't want to surface as a result. Time was ticking away and I was getting concerned about the next day with the battery. I finally got the lookouts in the conning tower dressed in their rain gear. He would look around some more and hesitate. Fifteen minutes later, he'd say, “Lookouts below.” Another fifteen or twenty-five minutes would go by and I'd get the lookouts back to the conning tower. He'd look around and hesitate some more. After another twenty minutes, he'd say, “Lookouts below.” This went on for about three or four hours until probably around one-thirty or two o'clock in the morning. We still hadn't charged any batteries and we were only four hours from sunrise. Finally, I got the lookouts up. This was a bit irritating to him, but he damn well knew that he had to surface to charge that battery, too. We finally got on the surface, I would say, around one thirty to two o'clock. We charged as rapidly as we could. We got in a pretty good charge before dawn started to break and we went down again. In the morning, he felt comfortable on the surface and he'd be slow to dive. As long as things were peaceful, he was happy; but when things started to happen, he got concerned. It really created a problem. I don't think that caused the severe depth-charging, because we were in position. We had a good shot. There's no doubt that we got that ship. There's no doubt that we sank a loaded transport with a lot of troops on it that were going down to reinforce the Japs against MacArthur's troops. We were coming back into the Philippines and he did an okay job there. That was fine, but he was just overcautious. I was not the only exec that thought this, too. I talked to others who were on the SUNFISH with him and there were similar circumstances on there. I shall leave him unnamed.

Donald R. Lennon:

You only had that one patrol on the ICEFISH, right?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then you took command of the BATFISH and it was there on the BATFISH that you were bombed by friendly fire.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

Yes. We had picked up three aviators, I think, as I mentioned. They were rattled more than the rest of us because the rest of us had made war patrols and had been friendly bombed before.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was the second time that you had been under fire from aircraft.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

If there is any such thing as a friendly bombing, yes. I don't consider any bombing friendly, personally. In this case, we were bombed by the United States forces because they were not paying attention. A lot of mistakes were involved. I was lucky the sub survived, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

Nowadays, with the Gulf War and even before that in Vietnam, so much was made of friendly fire as if it were something brand new and unusual. It's just a part of war that's just there.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

It happened in the Revolutionary War. It happened in the Civil War. It always happens and always will. However, it's great newspaper fodder, and it's great to sit back and be a Monday morning quarterback. You find it in the athletic pages. You find it in kibitzing military operations. It is nice as hell to point out the other guy's mistakes. I guess I'm guilty of some of that right here, sitting here now.

Donald R. Lennon:

This brings the World War II experiences pretty much to a close, I believe. You only had one patrol on the BATFISH before the war ended, did you not?

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

That's correct, the last patrol. By happenstance, our patrol was due to end the same day the Japanese surrendered. We left the entrance to Tokyo Bay that day and

headed for home. I think I covered in there about my first and only drink on a United States Navy ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, you drank to celebrate the victory.

Walter L. Small, Jr.:

We were celebrating the victory and we were headed for home. The war's over. We broke out a bit of whiskey. He issued the allotment to everybody on board. We gave it to the offcoming watch section. That gave them four hours before going back on watch. No, I'm sorry. That gave them eight hours before going back on watch. Each offcoming section got theirs. That's how we worked it, purely non-regulation, against Navy Regs. I put it in the log, and said we did it. I didn't say we gave them a drink of whiskey. I said we spliced the main brace. I used good British terminology for issuing the ration of rum every night.

Donald R. Lennon:

That pretty much brings this session to a close.

[End of Interview]

I grauated from Williston Sr.High School in 1962.I am looking for information on the school.