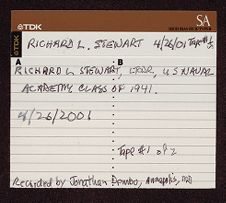

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #165 | |

| Commander Raymond V. Welch | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| January 23, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Fred D. Ragan:

I'll begin by asking you some simple questions. Number one: where were you born?

Raymond V. Welch:

I was born in Utica, New York, on February 28, 1918. I lived in several different towns in upper New York State, including Cooperstown, Old Forge, and Lowville, before my father accepted a job in the Canal Zone. We moved to Panama when I was eleven. I lived in Balboa until I finished high school and part of a year of junior college. Then I went to San Diego where I established a residence, which was required in order to get an appointment to the Naval Academy.

Fred D. Ragan:

What prompted your desire to go to the Naval Academy?

Raymond V. Welch:

My desire was prompted by living in the Canal Zone where the Navy ships were stationed or passing through. I made a lot of contacts with the Navy. Actually, by the time I was a senior in high school, I had decided that I wanted to have a career in the Navy. At that time, I joined the Naval Reserve unit in the Canal Zone. It was actually

called the Volunteer Communication Reserve. It was not a fully recognized Naval Reserve unit because it was devoted only to radio communications.

We had our own radio station and could contact the States or any other place we desired. It was manned by retired Naval personnel who taught us all they knew about radio. At the end of my senior year in high school, four of us made a cruise around the Caribbean on the USS TRENTON along with two destroyers. We actually served as seamen second class on the cruise in the radio shack.

Fred D. Ragan:

Well, you had a strong introduction to the Navy then.

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes, I was fully aware of what the Navy was all about, or so I thought. That was what motivated me. After high school, I went to San Diego because I had had no luck getting a congressional appointment to the Naval Academy. I knew that the Naval Reserve had twenty-five appointments every year into the Naval Academy. I went to San Diego for a year not only to establish a residence but also to attend a number of bonafide Naval Reserve drills, which I did. I became qualified and in the competitive exams stood #3, so I received an appointment to the Naval Academy. That's where I started.

Fred D. Ragan:

Did your family have a Naval connection?

Raymond V. Welch:

Not at all. Both my mother and father were children of dairy farmers. I have to say a word about my mother and father. They were part of the transition group of the 1920's. Young people were leaving their farms to go to town. The big farms were becoming mechanized. Both my mother and father grew up on dairy farms, but they were determined to live in town so their kids could get an education. My father went as far as the sixth grade in the country school. My mother went to eighth grade. She always said that she was the better educated. Both were honest, industrious, and devoted to their

Catholic church and their children. My father read every book I ever brought home and had a talent for mathematics.

I was the oldest of the four children in my family. I had two brothers and a sister. My sister died at a young age. I have one brother still living in Los Angeles. The other has died. One of my brothers was drafted into the Navy during World War II and served in the Pacific on minesweepers. The other was drafted into the Army and served in Korea. (You'll have to guide me as to how much you really want to know.)

Fred D. Ragan:

Well, I would like for us to go to the Naval Academy now. Tell us something about your experiences at the Naval Academy, what you liked and didn't like about it.

Raymond V. Welch:

My appointment in the Naval Academy was a competitive appointment. I had to take an examination in six subjects and qualify physically. I stood high enough on the Naval Reserve list (#3) to get an appointment. So I packed my little suitcase with my one suit and took a bus from San Diego to Annapolis. I sat up in the bus all the way.

The next day I took the physical examination and, by some miracle, passed it. That was in June of 1937. In those days, they simply brought in a number of candidates every day--about fifty--to give them a physical examination. We had to take the physical examination at the Naval Academy. All I could do in preparation for that was simply to go to a local Naval station and get their opinion. They couldn't really pass me since it had to be done at the Naval Academy.

The physical examination that year was no problem for me, but it was for a lot of others because, for the first time, they refracted our eyes. We ended up with the smallest class (400) in many years because they refracted our eyes and couldn't accept a lot of the candidates. I entered the Naval Academy on June 13, 1937. I still remember that I had to

pay a hundred dollars as a deposit to be used to pay my way home just in case I flunked out.

Fred D. Ragan:

That was big money in 1937.

Raymond V. Welch:

We spent the summer in vigorous training while waiting for the rest of the class to be assembled. I was glad I got there early. I was among the very first people to arrive. I was able to keep up with the other fellows.

Fred D. Ragan:

Are there any experiences as a plebe that stand out in your memory about that first year, which is often so tough?

Raymond V. Welch:

Looking back on it, I was a square peg that had to be driven into a round hole. I resisted everything all the way. I was really brought up to be rather independent, so it was part of my nature, I guess. I don't like to take orders from anybody. I like to do things the way I want to do them. The upperclassmen thought that I needed a lot of extra instruction. They didn't really convert me, but they made my life a lot more difficult.

At any rate, in preparation for the Naval Academy, I had studied an awful lot. In my first year at the Naval Academy, I stood very high academically. I had no academic problems the first or the second year. I was better prepared for the academics than most of the other fellows. Then my academic standing went downhill a bit.

I really can't say that I liked the plebe year, but I was sustained by the fact that I was where I wanted to be. I was willing to put up with everything, which wasn't too bad when you stop to think about it. I just was unwilling to accept it all. I had no real academic problems, but I had a lot of other problems because I was trying to be an independent person. I got myself in trouble during my last year by disobeying a company officer's command. I ended up my three-and-a half years with a low aptitude for the

service, so they said. It wasn't too bad. The curriculum was shortened from a full year to a half year in my last year.

We could see the war clouds on the horizon, although we weren't as fully informed about them as we should have been. There was a full-scale war going on in Europe, yet we read very little about it. We didn't really appreciate what was going to happen. I would say that part of it was that we didn't have time to pay much attention to the war, but also I don't think we had been kept well informed about it either.

Upon graduation, I drew a high number in the fish bowl and got my third choice, instead of my first choice, for duty. My third choice was a destroyer. It turned out to be an old World War I type destroyer, USS BERNADOU.

I have very fond memories of that ship. It was an old ship. One of the first things the captain told us was that this was a ship we were going to fight and that we had to be prepared. We trained a lot. We took the first American convoy to Iceland in June 1941 with the battleship TEXAS and a whole load of Marines who established a base there.

Fred D. Ragan:

You were in the Atlantic?

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes, it was in the Atlantic. That was in the summer of 1941. By the way, in the summer of 1941, I went to a six-week sonar school course in Key West in order to learn the business of attacking submarines. I came back to the ship and was placed in charge of the sonar.

We escorted our first convoy to Iceland and spent most of the next year taking convoys to Iceland or over to Ireland. We would pick up a convoy there and bring it back. We would always stop in Iceland in order to refuel because our destroyers could not carry enough fuel to patrol our station and follow the convoy. Most of the time, we

would pick up a convoy that was coming from Europe. We would pick it up south of Iceland and relieve the British escorts. Then we would take them on to the United States.

We had a number of encounters with U-boats. Of course you realize that it was considered an undeclared war in the fall of 1941. Yet we were fighting a war; there was no question about it. We had torpedoes fired at us. We made a number of depth charge attacks.

Fred D. Ragan:

This was in the summer of '41?

Raymond V. Welch:

It was in the summer, fall, and winter. We lost one destroyer in our squadron, the USS REUBENJAMES.

Fred D. Ragan:

Is that the one that made the history textbooks--the REUBEN JAMES?

Raymond V. Welch:

She was lost with almost all hands. One of my classmates, Craig Spower, was lost. Later, a new destroyer, the USS KEARNY, was hit by a torpedo in a fire room; however, because she was a new destroyer and a lot better built than the World War I type, she survived and got into Iceland. One of the old destroyers, the USS GREER, made contact with a U-boat and attempted to follow it. The U-boat turned on her, fired a torpedo, and fortunately missed. The GREER was carrying the mail to Iceland at that time. I wouldn't say we had a lot of contacts, but for every convoy, we knew from the radio contacts that there were U-boats following us.

The first ship we lost was a Navy tanker, the USS SALINAS. She was in the convoy and got torpedoed twice, but she didn't sink. That was in October of 1941. She fell behind and couldn't keep up. In fact, she lost her engines for about eight hours. Then, by some heroic measures, she was able to get underway again and proceed to the United States. On that particular day, the BERNADOU fired the first shot of World War

II. We made a depth charge attack just an hour or two after the SALINAS was torpedoed. We picked up a strong sonar contact and made two depth charge attacks after daylight.

The convoy commodore then called us back to the convoy, because he had only three escorts. The convoy had forty ships with only three escorts besides the BERNADOU and the COLE, which was guarding the SALINAS. We put on full speed and headed back to the convoy, but we had only gone a mile or two when the submarine surfaced astern of us. We disregarded orders, put the ship into a hard turn, and headed back towards the submarine. While we were making the turn, the forward gun was able to get off a couple of gunshots. Then the submarine dove. We made two more depth charge attacks, but then the convoy commodore called us back again. They gave us credit for damaging a U-boat. I think if we had been allowed to continue our attack, we probably could have sunk it. Anyway, that was the first time I ever saw a U-boat.

Fred D. Ragan:

This was in about October?

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes, it was October 30. After the war was declared in December, we got into a higher phase, because the German submarines became more daring. There were more of them. They had a great time on the East Coast, I know. They also kept after the convoys.

About June 1942, I volunteered to go to submarine school. It looked like the submarines were having more fun than the destroyers. I went to submarine school, which lasted three months. Then I went to the submarine squadron in Australia. I expected to get on a modern submarine, but I ended up on the old USS NAUTILUS. She was built in 1925 but modernized in 1939 and was a good submarine. At that time, she was the biggest submarine in the world. She had a crew of about ninety-five to a hundred. We

could do a lot of special things other submarines could not, like refuel a large seaplane, carry extra persons and supplies, lay mines, etc. Also, we had two six-inch guns.

One of the first things they put us to work at was training the Marines to make landings from a submarine, which they did using rubber boats. After that, we went to Attu, along with the NARWHAL, which was the sister ship of the NAUTILUS. We each carried about a hundred Army scouts. We went to the north side of the island of Attu and landed them on the day before the expected invasion by the big Fleet on the south side to retake the island from the Japs. The scouts mission was to climb the top of the mountain and come down behind the Japanese while the Fleet came ashore the next day. The weather conditions in April in Alaska were horrible. We did get all the scouts ashore. We found out later that they had to cross a river, which they had not anticipated, in the freezing cold. They all got frostbite. Their equipment wouldn't operate. They were really ineffective in the battle. Most of them were in the hospital afterwards. I don't think they lost any men, but it was a wasted effort by the almost two hundred men we put ashore.

I spent a year on the NAUTILUS. We had several missions, mostly in support of the Marine Corps. We did not attack any ships or act like a real submarine. The NAUTILUS was too big and too slow to do more than carry troops or things of that nature. Then I went to the STINGRAY, which was a fairly modern submarine built just before the war started. I was the torpedo and gunnery officer for five submarine patrols.

Fred D. Ragan:

Do you recall the time frame when you left the NAUTILUS and went to the STINGRAY?

Raymond V. Welch:

I left the NAUTILUS after a year. That would have been the end of 1943, maybe a little bit later. Then I became the torpedo and gunnery officer of the STINGRAY. As I recall, I made five successful patrols there. Our missions were to sink ships, plane guard at the invasion of Guam, and several short missions to land guerrillas in the Philippines. Then, after a year on the STINGRAY, I was ordered to San Francisco in late 1944 to be the executive officer of the SEAHORSE. The SEAHORSE had an excellent record after seven patrols and needed an overhaul. I joined the SEAHORSE and we were there for about two months while it was modernized and overhauled.

We went to Guam early in 1945 where we tested the first mine-hunting sonar built for the Navy. Admiral Lockwood personally supervised our training. As soon as we learned how to use that and it appeared to be successful, we were sent to the Sea of Japan to find a way through the minefields that we already knew were guarding the Sea. After a month of searching, we found a way through the minefield.

The plan was to equip other submarines with the mine-hunting sonar and send them all into the Sea of Japan at once. We were running short of targets out in the wide Pacific, but we knew that there was constant traffic between Japan and Korea. Two submarines had tried to go in there and both of them were lost due to mines. Until we had this mine-hunting sonar, the Admiral wouldn't let any other submarines go in. The Japanese even kept their running lights on in the Sea of Japan because they knew we weren't there. At any rate, our special mission was to find a path and get the information back to Pearl Harbor.

Near the last day of our search we got depth charged very badly, because the Japs managed to find us. We took a depth charge beating so severe that when we finally got

back to Guam, they took our mine-hunting sonar off and put it on another ship and sent us back to Pearl for major repairs. The captain was awarded a Navy Cross and I received a Silver Star for the success of our special mission. Eight submarines were then sent in to the Sea of Japan through the minefield the SEAHORSE had scouted and sank about thirty ships, completely disrupting the Korea to Japan supply line. One of the eight submarines was lost while leaving the Sea of Japan by the northern route.

Fred D. Ragan:

Were you able to sink any Japanese ships when you were in those lanes?

Raymond V. Welch:

No. That was one patrol where our mission was more important than sinking ships, unless we ran into a big ship. If we could take one, that was fine, but we were not to spend time looking for or chasing ships. We came back to Pearl Harbor for repairs, which were very extensive. We just barely survived that depth charging.

In Pearl Harbor I fell on my right knee. The doctor at the submarine hospital took an x-ray and said that I had a broken kneecap. They sent me to the big Army hospital in Hawaii. I was there for a week before I even saw another doctor, because the hospital was full of Marines that were wounded. When I finally saw another doctor, he took another x-ray. He said there was nothing wrong with my knee. He said, “Let me fix it.” My leg was completely stiff, so I couldn't use it. He put his hand underneath my knee and pushed it down like this. I nearly died. He said, “I'm going to do that every hour or two, maybe just three times a day, until you can walk again.” It wasn't very long before I could walk. In the meantime, the SEAHORSE had been sent on a photoreconnaissance mission, and I then became the executive officer of the submarine GROUPER.

Fred D. Ragan:

This would have been in what year?

Raymond V. Welch:

That was in June 1945. Actually, the war was ending for us about that time. We brought the GROUPER back to New London at the end of the war. From there, I went to one of the submarine tenders, the USS HOWARD W. GILMORE, in Key West, as the engineering officer. Then I went to postgraduate school for two years at M.I.T. and earned a master's degree in mechanical engineering. I went back to sea as a squadron engineer and, later, as a flotilla engineer. I later took command of the GUITARRO, which was recommissioned in San Francisco during the Korean War. Submarines did not have much to do during the Korean War. My duty was mostly in San Diego training with the GUITARRO. After a year and a half of that, I went to the Bureau of Ordnance Torpedo Research and Development Branch and stayed there for three years.

Because I had been to postgraduate school, I was out of step with the rest of my submarine classmates, and I didn't want to go back to a desk job or something. I loved those small ships. Therefore, I asked to go to a destroyer. I got command of the USS HANK, which was destroyer DD-702. I was her captain for two years. I then worked for three years at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory in Washington as the underwater weapons specialist. After almost a year there, I was the executive officer of that laboratory.

Fred D. Ragan:

Could you go back to the STINGRAY and discuss some of the missions that you were on? You indicated that you sank some Japanese ships. Are there any of those that stand out?

Raymond V. Welch:

The Japanese we encountered did not have huge convoys. They simply had two or three ships with maybe two or three escorts. Very seldom did you run into any convoy that was larger than that. We did come across a three-ship convoy. We chased it. Since I was the torpedo and gunnery officer, I had to run the torpedo data computer. I think I

stood at that machine for almost twenty-four hours while we were trying to catch up to the Japanese convoy. You had to make an end around and get ahead of them. We made the attack at night. I know we sank two of the ships. The next day, we saw the third one, but we weren't able to get near it. That was more or less routine.

We were never assigned to a wolf pack. The submarine force did develop wolf packs with two or three submarines. They would go out and stay connected to each other by radio. When one made a contact, they would call in the other one or two and attack the convoy if it was big enough for it. We were never part of a wolf pack.

Fred D. Ragan:

When you were in the Sea of Japan and went through those severe depth charges, do you recall the events leading up to your being detected?

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes. The entrance of the Sea of Japan is around forty miles wide. But Tsushima, an island, is in the middle. We knew from our intelligence that both sides of the island had minefields planted. As a matter of fact, when we first got there, we started up the eastern side and actually saw them planting mines. We decided to stay out of that side. The mine-hunting sonar had a range of only about a hundred or one-hundred-and-fifty yards--roughly about one ship length--that you could pick up the mine. We had to go very slowly and maneuver radically. If you picked one up, hopefully you picked it up ahead of you and not off to the side. If you picked it up ahead, you could fishtail around it, one propeller full ahead and one astern. That is how we found our way through. Without a mine-hunting sonar, it would have been fatal to go through there. It was a tough job and extremely dangerous.

We had plotted the mines. With our periscope, we could take bearings. In the daylight, we could get bearings from Tsushima. From our dead reckoning position, we

could plot where the mines really were. Of course, the Japanese always left a lane for them to go through. They had to do that. We found a lane and a way to go through. We had sent the message back to COMSUBPAC but were still making some final runs when we got caught.

This is how it happened. There was another US submarine about fifty miles from us. One night when we surfaced to charge our batteries, we picked up his radar, which was the same frequency as our radar. We got used to him being there. On this particular night, we picked up a radar that was quite similar to ours. We didn't know that the Japanese had just begun to use a radar with our same frequency. We just assumed it was the other US submarine. When it got to be light in the morning, we could see that it was a Japanese destroyer. We turned tail and ran south on the surface as fast as we could. They shot at us but never even came close. We were getting away from him and could have outrun him at our speed, but the Japanese Naval Base Sasebo was only thirty miles away, and apparently, they called the naval base to send out planes. We couldn't fight the planes that appeared, so we dove.

Well, the destroyers--now two of them--had very good sonar. Despite what we did, they found us and spent all day above us. We submerged about 6:30 in the morning. They dropped depth charges on us until almost midnight. Their first pattern of depth charges was about seven charges, which landed almost perfectly right above the length of our ship. We were put out of commission from that. We had no lights or propulsion. We didn't have anything. We simply fell to the bottom. Fortunately, the bottom was five hundred and fifty feet deep. We were really concerned, because we were supposedly a four-hundred-foot boat.

Once we got down there, we struggled to get our lights back and decided to stay right there. That was the best thing that could have happened to us because the Japanese also did not realize that the bottom was that deep. Our charts did not indicate a depth of five hundred feet. We were down there in the mud. They never came very close, thereafter; at least not close enough to do structural damage. They stayed in the area and brought in other destroyers with more depth charges. We had plenty of depth charges planted all around, but none of them actually hit us. Those first seven did everything.

Have you ever seen a torpedo tube? Did you ever see one that was egg shaped? The propeller shafts were knocked out of line. The following was the worst thing that happened. We had a radar mast that went up through the radio shack and was about this big (ten-inch diameter) around. It had a packing gland to keep the water out. A depth charge blew the packing gland in, which meant that we had a huge waterfall coming right through the radio shack. It took fifteen or twenty minutes to get that leak stopped. In the meantime, it flooded all the equipment in the radio room and the storeroom underneath it. We didn't have a radio left. We also lost all but one piece of sonar equipment. One was blown right off the bulkhead. The optics on both periscopes were ruined. We didn't find this out until later. The engines also had cracks in them. The ship was a shambles of glass and hydraulic oil.

By eleven or twelve o'clock that night we could no longer hear any of the Japanese destroyers maneuvering around. We then proceeded to try to get off the bottom and get back up to the surface. We were stuck so deeply in the mud and at such a depth that blowing the water out of the tanks was difficult. We normally use the high-pressure air in the tanks to blow the water out the bottom. The bottom was so deep in the mud that our

attempt didn't expel anything. After three hours, we got off the bottom by employing various measures, including rocking the boat from one side to the other, blowing the forward tank then blowing the after tank, and blowing the side tank. We were getting worried about not having enough air to do it with. We finally got off. We came up like a cork, all the way to the surface. Fortunately, when we got to topside, it was black and raining. There was nothing in sight.

The ship had a 15-degree list. The depth charges had ruptured the ballast tanks topside. There was a lot of damage. We had a main gyrocompass and an auxiliary gyrocompass. They were both wrecked. The only thing I had left to navigate with was the little magnetic compass that was used in tanks. That was all we had to steer by. That gave us a few fits. We had no radio, of course, no radar, and no sonar. We did have two engines, but we couldn't really determine how fast they could go. We couldn't make fast dives. All of our valves on top of the ballast tanks had to be operated manually instead of hydraulically. It would take us five minutes to dive, which was too long. We had no way to let Hawaii know that we were in bad shape. We stayed submerged all day long because we couldn't dive if a plane attacked. We surfaced at night and ran towards Guam.

In the meantime, we did everything we could to get the radio back into commission. We took out all of the equipment and dumped it into fresh water. You have to take everything out of the boxes, flush it with fresh water, dry it out, put it back in, and try it. We did that for almost a week.

We finally got the radio equipment working, but then we didn't have any antennas. All the antennas were drowned out. We had to rig a wire from the radio shack

up through the conning tower hatch topside. They finally got a message off to COMSUBPAC that we had been damaged and were coming home. They sent another submarine to escort us. The Fleet was attacking Okinawa at that time, and we had to go past Okinawa to get to Guam. All the airplanes were busy. They would attack anything that looked like a submarine and we had no way of communicating with an airplane.

We got back to Guam and made an assessment of the damage. They sent us back to Pearl because we had so many things to report, like these egg shaped torpedo tubes and the propeller shafts that made so much noise. They decided they would never send her back to the forward area again. That is when I fell and hurt my knee. They told me I had a broken kneecap, which I really didn't have. That was the end of my tour on the SEAHORSE. Then I went as exec on the GROUPER. We were preparing for a patrol but the war ended and we were ordered to New London.

Fred D. Ragan:

Where were you when you left the SEAHORSE?

Raymond V. Welch:

I left the S EAHORSE in Pearl Harbor. She went to sea. I came back from the hospital and was assigned to the GROUPER. Then we brought her back to New London after the war ended.

My last duty in the Navy was the Naval Ordnance Laboratory. I did three years there as the underwater weapons specialist. At that time, I had earned some expertise in underwater weapons, torpedoes, and underwater sound gear. Then at PG school I took what was called the torpedo course, which involves mechanical engineering, underwater acoustics, and propulsion. I got my master's degree.

Fred D. Ragan:

Let's go back to the Korean incident. Were you involved to any great extent in carrying troops?

Raymond V. Welch:

No, there were a few submarines out there observing and trying to keep track of some of the Russian submarines that were prowling around. No, we did not contribute much to the Korean War. My ship never even got west of San Diego.

Fred D. Ragan:

Not a submariner war, was it?

Raymond V. Welch:

No, not a submariner.

Fred D. Ragan:

Not as WWII had been?

Raymond V. Welch:

No. After the duty at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory, I had completed twenty years in the Navy. For a number of reasons, I retired. The number one reason was that I was not promoted to captain as some of my other classmates were. They divided the class in half--half made captains and the other half stayed commanders. I could not see staying in the Navy that way. Also, I had seven children. Money was not available for my children's college educations. At the end of my twenty years, I retired.

Fred D. Ragan:

That would have been in 1961?

Raymond V. Welch:

1961. I did get a letter from Chief Naval Operations stating that they would like me to stay, but that they could not promote me. I said, “No, thanks.” First I went to work for Martin Marietta in Baltimore in their ASW group. They built a lot of underwater acoustic systems. I helped design and test some of those in the Bahamas and Bermuda.

After two years, they had a convulsion in the upper management and my boss, who had been with the company for twenty-five years, was told to clean out his desk by noon. Martin did that sort of thing quite a few times. Also, they wanted to transfer the whole group to Santa Monica. I didn't want to go to the West Coast, so I joined Westinghouse in Baltimore. Again, I was working in the underwater weapon branch. I stayed with them for twenty-four years. I went there as a fellow engineer. At Westinghouse,

engineers can either remain in the detailed, technical divisions of the corporation or go into management. I started out in the technical division as a fellow engineer. After about eight or ten years, I became program manager at Westinghouse. I stayed there until I retired in 1984.

Fred D. Ragan:

You had two careers.

Raymond V. Welch:

If I count the Naval Academy and the two years I spent in the Reserve, I spent twenty-six years in the Navy and twenty-six years at Westinghouse.

Fred D. Ragan:

Was the work that you did with Martin Marietta and Westinghouse defense contract related?

Raymond V. Welch:

It was all defense contract related. There was a big effort to detect Russian submarines in particular. They needed super acoustic systems to be able to detect and track submarines. They also needed underwater weapons. I was engaged in that most of the time. I rather enjoyed it, but I really liked going to sea better. I liked small ships, like submarines or destroyers. I would be lost on a carrier and wouldn't really enjoy it. On a small ship, I enjoyed my naval career very much. I was sorry to leave it, but it was the best thing I could do for my children.

Fred D. Ragan:

Tell us something, if you don't mind, about your personal life, your family. You said you have seven children.

Raymond V. Welch:

I have fourteen now.

Fred D. Ragan:

Fourteen?

Raymond V. Welch:

I have seven children of my own. I met Justine while at the Naval Academy. We married as soon as we were allowed to. There was a ban against marrying for two years after graduation at that time. They finally lowered it to a year and a month. We were

married a year and five months after graduation. Some of our classmates didn't wait that long. Justine's father and brother were Army officers. She joined the Navy. We had a wonderful life for the most part. We had problems, but the problems were usually not with each other but with money.

I would have stayed in the Navy for the rest of my life if I had had no children. However, when my oldest boy was finishing high school and I could not find the money to send him to the University of Maryland, I had to face the fact that I had to leave. I'm glad I did now. All my children did very well. Of the seven, two have doctoral degrees and five have master's degrees. They earned most of their way through college themselves.

My wife died of cancer in 1979. I married again a year or so later. She had four children, fortunately all grown up. Then she also died of cancer in 1989. I married my present wife in 1991. She has three children, so now I have fourteen. Fortunately, they're all grown. Five of my children were boys. I wanted them all to go to the Naval Academy, but only two did. The oldest boy went to the Naval Academy and became a fighter pilot. The “number three” boy wanted to be an aviator, but Admiral Rickover chose him to become a submariner. Right now, he is the president of the Electric Boat Company, which builds submarines. The two boys did not stay in the Navy. They both left after ten years. I am very proud of all my children.

After the war, the Navy was a lot different than it was before the war as far as careers were concerned. When my class went to the Naval Academy, no one ever discussed retiring after twenty years or so. We just assumed that we were going to stay in the Navy for the rest of our lives. Now young kids in the Navy know they have to serve

five years. But a lot of them, particularly if their wives are objecting, will leave after ten years. It takes an unusual wife to endure her husband being away. When I was a skipper on the HANK, for example, I was captain for two years. We spent over fourteen months in the Mediterranean. Even the other ten months or so were spent down in Guantanamo or some other glorious place like that. That is a real problem. The boy that became an aviator had problems with his knees and was up for a medical discharge four times. Each time he managed to stay until after the fourth time. He decided to heck with this, I'm not going through this again. He now flies DC-40s and 747s.

Fred D. Ragan:

He's with a commercial airline?

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes. He has been in Arabia and the Emirates for the last twelve years. The second boy is a computer expert. The third boy is the president of the Electric Boat Company. The fourth boy is a geologist for Chevron, looking for oil. He commutes to Angola in Africa. He spends a month in Angola, a month at home, a month in Angola, and a month at home. He is going to do that for three years while they develop an oil field at the Congo River. The fifth boy has a Ph.D. in electronics. He is head of manufacturing for Spectro Diode Laboratory, a small laser company. Even the girls did pretty well.

Fred D. Ragan:

Your boys have all done well, haven't they? Are the girls married?

Raymond V. Welch:

Yes. One has four children and the other has none. She has emigrated to Canada and lives in Vancouver. In order to work up there, one must have a work permit. Her work is very special. I have two children in California, one in Vancouver, one in New London, one in Washington, one in Arabia, and one in Colorado. Am I leaving someone

out? They are spread out. Every year or so we manage to get together for a week at someplace like Nags Head.

Fred D. Ragan:

That is a beautiful place to be together.

Raymond V. Welch:

We find a place to let the grandchildren romp in the ocean while the rest of us sit back and talk. That's it. I don't know what else you'd like to know.

[End of Interview]

It's amazing to be able to share the history of my family's service to the country. Granddad was a good man who stood up for his family even the adopted blacksheep who didn't feel like he was ever worth it.