| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #179 | |

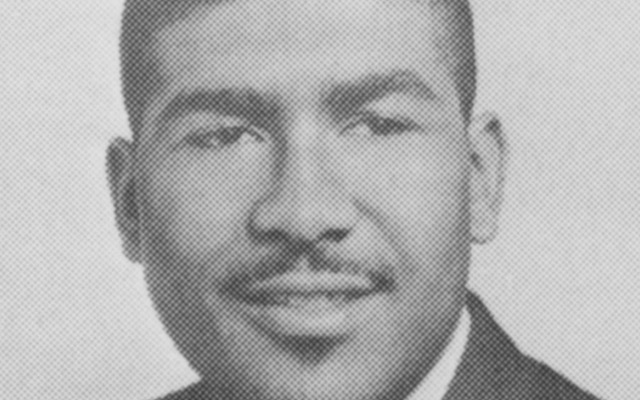

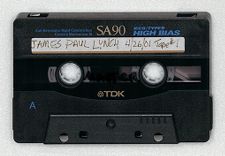

| Captain Robert G. Black | |

| May 10, 1999; December 8, 1999 | |

| Interviews #1 and 2 | |

| Interviews Conducted by H. A. I. Sugg |

H.A.I. Sugg:

To begin with, just give a brief overall of your early life and how you happened to get into the Navy.

Robert G. Black:

I was born in Gallatin, Missouri, on October 22, 1917. I went to grade school and graduated from high school. All the time that I was growing up, I had one desire in the world, and that was to get out and see the world. I remember the year 1927. I was standing in front of an old wooden cook stove in my mother's kitchen, and my mother said to me, "Son, I know when the happiest day of your life will be."

I said, "Mother when is that?"

She said, "When you can leave here and start seeing the world." I had desired in the beginning to go to the Military Academy. I am from a divided political family: Half Republicans, half Democrats. Both were strong in there viewpoints.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Typical Missouri.

Robert G. Black:

Typical of the Missourians. I was on the Democratic side of this thing. I applied to our congressman--and this of course was in the height of the Depression--for an appointment. I got word back--being very honest in it--that said, "We understand your political background, and I'm sorry we have no appointment for you."

I then definitely decided that I wanted to be in a profession that would allow me to see the world; so I chose petroleum geology as the field I would enter. I entered the university, the Missouri School of Mines, went for six months and found that was not the place for me. They did not have what I wanted. I returned home, and then in 1936 I went to the University of Tulsa. I was at the University of Tulsa when I got a job with Sinclair Oil Company, working with their office. Fortunately, my second summer, I had the job as appointment clerk for the executives of the company. There were only five executives in this building--it was a quarter-block wide and a half block-long--and they became interested in my career. They said if I wanted to work for the Sinclair Oil Company when I got out of college, I should go to LSU. And LSU had the best Gulf Coast geology course in the United States.

I ended up with a scholarship from LSU and a work scholarship from Sinclair. Because I transferred from Tulsa after two years, I lost some credits, of course; so it took me three years to graduate, but I made money going to school my last three years. I had a really outstanding boss. He had two cars--one a red convertible Packard, which he allowed me to use on my special dates. So, I really felt like I was in heaven.

My senior year I began to see . . . well, I should go back. To graduate from Louisiana State University in Petroleum Geology, you have to spend a summer in Colorado. LSU has a ten-thousand-acre spread leased down there. You have to spend a summer there and map the geological formations of the Rockies, because there are no rocks on the surface in Louisiana. Along with LSU, we had students from other schools who joined us because they wanted in on this particular kind of fieldwork we were doing.

While we were there, the war was beginning to develop. At that time Finland was in the middle of the war with Russia, and we were all coming in from the field and pulling for Finland every day, hoping that they would win. Of course, they didn't, but it was then that I began to look very seriously at my future and what I was going to do as far as the coming war. I went back to Louisiana to finish out, and I read an article in the paper about a V-7 Program. I requested information, signed up, and asked for a cruise on 12 December 1940, which I took. Fortunately, I was accepted as a midshipman to enter midshipman school on my graduation from LSU in June of 1941.

When I entered midshipman school at Northwestern, I had no idea I was going to be in the Navy. I thought I was going to get commissioned to go and be in the Reserves, go back to Baton Rouge, and go to work. Halfway through the summer, I let them know that I had planned to go back. It was at this point that they announced that there would be no more inactive duty. Everyone commissioned would go on active duty. I was commissioned on the twelfth of September 1941 as an ensign.

On the twelfth of August 1941, I put in a request for submarines. I got a letter back from the Bureau of Navigation that stated that I did not have enough engineering in my background to go to submarine school; therefore, I was being assigned to a course in diesel engineering at North Carolina State University. They sent roughly twenty-eight newly commissioned ensigns out of each graduating class to North Carolina State to take this course--North Carolina State being one of the premier schools in the country in diesel engineering.

The idea was that we would be engineering officers on LSTs, LSDs, and for landing craft. While there, the war started, and I applied for submarines again. I guess I applied

about the tenth. I got an immediate answer back saying that I had so much engineering in my background that there would be no need for me to go to submarine school; and I was to report directly to the USS FLYING FISH. Can you imagine the commanding officer of the FLYING FISH, G. R. Donahough (Class of 1927), who ran everything by the book and who was considered to be the toughest submarine commanding officer in the Fleet, getting orders that he was going to receive a ninety-day wonder who hadn't been to submarine school? You can imagine his consternation.

I arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and reported to the commanding officer of the Naval shipyard first and then to the submarine early in January. It was the first submarine I had ever seen. My arrival was not very auspicious, because, first, I had never seen a submarine, and, secondly, I had arrived with my big trunk with all my uniforms just like I was going to a battleship. I arrived at the pier, and everybody looked at me and smiled and said, "No, you don't report here, you report to the office in that building." As I reached the second deck of the building where the office of the FLYING FISH was, which by the way had been commissioned on December 10--the first U.S. Navy ship to be commissioned after Pearl--Harbor and as I reached the top step, I heard the yeoman, whose name I still remember, Will Sinsky, yell at the captain, “Here he comes."

When I walked in the office, everybody was looking at this strange object that was coming through the door. The first thing the captain said was, "Welcome, would you like to have a cup of coffee?" I learned at that point that that's the way everything starts in the Navy when you meet a new situation: "Would you like to have a cup of coffee?"

I arrived at the FLYING FISH early in January and made its first dive. Now, everyone was watching me on this first dive to see what I was going to do. They all had

told me about the various things that were going to happen--the kinds of leaks and this type of thing--and here I was not knowing anything about a submarine, so they assumed I was going to be a little nervous about all this. Well, ignorance is bliss, and I was probably the calmest person on board when we made our first test dive in the FLYING FISH.

We found that we were in pretty good shape considering we were in this commissioning situation. We went through all the various trials that you have to go through and worked our way down the coast, loading torpedoes in Newport. We went through all the training that was necessary at New London, and then we left New London and departed for Pearl Harbor. Midway via. En route to Midway, we ran into a little excitement. We sighted a periscope going down the coast. We made a quick setup, and, of course, we missed the target. The commanding officer was highly criticized, of course, because we didn't do anything in time or make a better approach. But the trip through the Panama Canal was uneventful, and we went on out to Pearl and got ourselves ready to make our first war patrol.

For our first war patrol in the FLYING FISH, we departed from Pearl Harbor on June 4 for Midway and completed the patrol on July 5, 1942. Our patrol area assigned to us was the China Sea, between the lights of Hokusho(?), Tun Yung To(?), and that general area. En route to Midway, we had a very uneventful trip.

When you arrived in Midway, you always tried to figure out some reason to spend the night so that you could enjoy one more night at the bar, top off, and be ready to go the next day. However, they told us we didn't need to come up with any story; we would be there for a short period. It turned out, unbeknownst to us, that the Battle of Midway was forming up. There was one submarine in Midway when we arrived. It was in dry dock.

They had to get her out of dry dock, button her up, and send her back to Pearl to finish out a refit. They were trying to refit her there, but with the Battle of Midway approaching, they had to get her out of there.

We walked around Midway and looked over this very peaceful island. The only thing basically there were the shops, the base, and the telegraph station that had been set up there years ago to relay the messages from Japan to the U.S. on the underwater cable to the United States. They had a nice little area of housing. Every ship that came to Midway was required to bring so many pounds of topsoil with it. This was to provide topsoil to put on the sand for those people to raise gardens.

While we were there, we were told that they still had some of the people who had worked with the telegraph there; and they were getting occasional buzzes on the other end from Tokyo on that wire, but nothing was being sent worthwhile.

After we were able to view the island and enjoy a few hours, we headed out for the Battle of Midway. We took part but saw no action. In fact, we were en route to our assigned patrol area, stopping at Midway to top off for fuel, when our orders were changed, and we were assigned to patrol on a one-hundred-mile circle from Midway. We departed Midway, June the fourth, for the circle. We had no more then settled on the hundred-mile arc on the fifth, when orders came to close to twelve miles.

We received many area changes during the Battle of Midway, but we in the FLYING FISH were never in contact with the Japanese fleet. On the ninth of June we returned to Midway to find the NAUTILUS, GROUPER, CASHALOT, PLUNGER, and DOLPHIN already in port. We were, of course, interested in surveying the damage done to the island and listening to the stories of those who were on the island or in the air during the battle.

Submarines did not play much of a part in the Battle of Midway, even though it was one of the great battles and the turning point in World War II.

While we were in Midway, we talked to the aviators who had flown the PBYs. They said the only reason that they hadn't been shot down or more hadn't been shot down was the fact that no one in the Japanese fleet could believe that anything could fly as slow as a PBY and still stay in the air. One of the pilots told us about having his microphone, throat microphone, shot off. The Japanese had not bombed the runway to the airport, nor the hangar because they were so sure that they were going to take over the island. They hit the hospital, but to be perfectly honest, it was obviously a mistake; they didn't intentionally hit the hospital; it was just part of the bombing that took place.

One of the most unusual things is that the buildings that were put up were basically frame buildings, other than the hangars and some of the other structures where the ammunition was held. They were poorly constructed by contractors who apparently were lining their pockets. But in a way, it turned out to be a great advantage; because when the bombs went off, a whole side would fall out of a building rather than it breaking up. All they had to do was put the side back in place, and it would put the building back together.

After viewing all of this, it then came time for us to get on to the patrol that we had started to make in the beginning. So we departed Midway on June 11 for our assigned patrol area--I've already indicated where we went--and on June 17, we sighted our first enemy ship, a five-hundred-ton tanker, sailing the direct route between Tokyo and Wake Island. We got two hits on this tanker but only put a list on it, which they were able to correct. We got into a new firing position, and we fired four more torpedoes. One passed ahead of the target and the other astern, the third went around it, and the fourth was a cold

run. So we did not do much damage. We did some damage, but not enough to cause the ship to sink.

On July 1, 1942, we attacked a forty-five-ton tanker. We fired three torpedoes with a perfect setup at eight hundred yards, and all of those missed. July 4 we sailed, and we attacked a thousand-ton armed trawler. We fired one torpedo. It passed under, but did not explode. This brings us to the “story of the torpedoes of World War II.”

The torpedoes of World War II were built with a magnetic exploder. We were forbidden to fire the torpedo to hit the ship; we were to fire the torpedo to run under the keel of the ship. The idea was that the magnetic exploder would be set off by the magnetic force of the ship, thus breaking the keel as the torpedo passed under and doing much more damage than would otherwise be done. This was great, but the torpedoes didn't work. It was not until well into the year 1943 that we were able to get the Bureau of Ordnance to admit that these were faulty exploders, and then we had to finally tie them down.

Then we fired torpedoes directed to hit the ship to get them to explode properly.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Those torpedoes came from the torpedo station in Newport?

Robert G. Black:

They came from the torpedo station in Newport, and they had been readied by the tender. Certain parts of the torpedo, we on the submarine could not touch. We were not supposed to touch the exploder; that was all supposed to have been set in the breech. But later on, as the torpedo and gunnery officer, I checked every one of them out, even though I wasn't supposed to.

On that patrol we had twenty-four-contacts: fourteen were sampans, ten were other vessels. We fired thirteen torpedoes. We returned to port with only twelve-hundred gallons of fuel. The engineering officer was really worried, gnashing his teeth the last few days

coming into port. We were only given credit for damaging the ship going to Wake, and we had so much trouble with the torpedoes, that we wondered if it was all worthwhile.

After the first patrol, we came back to Midway. We were to be the first submarine refitted in Midway, and that was not a pleasant thought. The only facility in Midway for us was the old hotel that had been owned by Pan Am. They used it as a refueling station and rest for their planes going to the South Pacific. However, we were able to enjoy ourselves. They provided us with a ration of booze, there were plenty of gooney birds to keep us busy, and the fishing was good. After our three weeks were up on shore, we departed on our second patrol, which was to the Caroline Islands and basically off the entrance to Truk--Truk being the Japanese Pearl Harbor. That was where their fleet was stationed--in the forward area--and it was certainly a well-guarded island.

We arrived on station on August 25. At about 14:00 on the 28, we sighted a large, high-masted ship and changed course to a normal approach course. The target proved to be a KONJO class battleship escorted by two DDs. We made ready six battle tubes: two for the closest DD and four for the battleship. We missed the DD, but two torpedoes hit the battleship shortly after our attack. The counterattack started. We counted thirty-six explosions during one hour and fifty-three minutes. We stayed below periscope depth. The two DDs and the two patrol aircraft guarding the entrance to Truk took part in the depth- charging that we received.

Shortly after returning to periscope depth and starting normal machinery, number nine torpedo tube was blown down and prepared for inspection. Very soon after, we felt the ship go ajar as if a water slug had been fired. In fact, a nervous torpedo man had fired number seven by hand rather than number nine, with a full impulse on charge. He had fired

into the outer door with the outer door closed; so you can imagine the kind of chaos that was brought on. At one point after this, we heard a loud explosion. We raised the scope and determined that a bomb had been dropped astern of us. They had seen the partial impulse from the bubble that was emitted from the number seven tube. At about 18:00 we fired three torpedoes at a destroyer, and missed. Soon, we had a pattern of seven depth charges dropped in quick succession very near us. We went deep and cleared the area.

At about 22:05, we surfaced, after sixteen hours submerged. Two main engines had been flooded. We started battery charge. At about 21:46 we picked up a destroyer at about eight thousand yards. Our engines were smoking badly. The DD sighted us and headed towards us. We could not get into an attack position, so we dove. He dropped eleven charges close astern while we were at 150 feet. Some time later, he dropped a pattern of eight, also astern. We cleared the area, put in a battery charge, and headed back to the Truk entrance.

We determined that number seven torpedo tube was inoperable and partially open. On the night of the thirty-first of August, we worked our way back eastward to check out the number seven tube. We sent Walter Small . . .Walter Small was well known to this group since he is from North Carolina and also later commanded this particular ship. We sent Walter Small and one other man into the after-trim tank. He was told that when he went in, if we picked up any contacts, that we would have to dive. He would be in the tank, and he wouldn't survive. With this in mind, he was very astute in going about his business. (Walter Small was one of the really outstanding submariners with whom I was a shipmate throughout my entire career in the Navy. He was very thorough and very good at everything he did.) He entered the torpedo tube and extracted the stop bolt. We were able to

get the torpedo back into the ship; but in doing so, we partially flooded the floor of the after torpedo room. It's a good thing that the torpedo was in the after torpedo room, because the torpedo had not armed. The impeller had not run. An impeller runs for so many turns after it's fired before the submarine arms. If it had been in the forward tube and we had gone forward, we would, of course, been running that impeller. As it was, it was in the after tube; so, we didn't turn the impeller while we were actually sailing. We got the torpedo out, and it was damaged.

On September 2 at 13:45, we picked up the Japanese patrol boat 583, very actively pursuing us. This patrol boat was one of the really most tenacious ships that we encountered during our whole experience in the war. He got himself into firing position. We fired two torpedoes at a seven-hundred-yard range. Neither exploded. The captain witnessed the wakes and knew that the wakes ran true; he witnessed them pass and knew they went under the patrol craft, but they failed to detonate.

As we passed at 150 feet, three charges were dropped. Ten minutes later, five more were dropped. All were very close, causing considerable damage. At 17:20, the DD made false contact astern and dropped seven more charges, but they were really of no concern to us.

On September 3, we were some way out from Truk. There was another patrol craft, and at 22:08 we sank this particular craft. On September 4, we headed back to the north passage of Truk Island. Again we encountered our PC583, again standing out for his daily patrol. Before we could get into an improved torpedo position, we talked the commanding officer into firing torpedoes. This time we had the same luck. We fired the torpedoes, but no hit.

In the next four and a half hours, we had fifty-four depth charges dropped on us. Twenty-nine were dropped in thirty minutes and were very close or hit. During the depth-charging, the captain, who was very astute in handling young people like me, turned and said (since I was a junior officer, who always takes the butt of everything), "Black, your life isn't worth a plugged nickel right now."

And I said, "Yes sir, Captain, but you are right with me." That broke the tension in the conning tower. He knew exactly what he was doing. He knew that I would come back with some kind of a smart aleck answer, because I didn't know any better, and so it accomplished exactly what he wanted it to.

H.A.I. Sugg:

This was during the second patrol with Donahough?

Robert G. Black:

This is our second patrol with Donahough. September 5, forty-three miles from Truk, we carefully inspected our boat and found that our material condition would not allow us to stay. We had one periscope out of commission. We had engines in bad shape and leaks all over. We also had sound gear knocked out of order. So the commanding officer determined that we had to discontinue our patrol and return to Pearl. He sent the message accordingly, so we left for Pearl and shortened our second patrol. It ended on September the eighteenth.

H.A.I. Sugg:

At that time was Admiral Lockwood COMSUBPAC?

Robert G. Black:

I believe that Admiral English was still there. I'm not sure. No, Admiral Lockwood was . . . yes, he was still there.

In our patrol report the commanding officer wrote, "Official account exclusive of charges dropped on false contacts: 131 depth charges and at least two bombs on station; four

bombs by one plane and two depth charges by another plane while returning from station." In other words, we had this happen to us as we were coming back.

The third patrol of the USS FLIYING FISH: Commanding Officer G. R. Donahough departed Pearl on October 1942 and ended in Brisbane, Australia, on December 16, 1942. Our area was the Solomon Island area, and it resulted in the sinking of two destroyers. On November 14 at about 16:00, we sighted a large task force: five destroyers starboard screen; one light cruiser ahead; four area cruisers in a column, five hundred yards apart; and masts picked up on portside, indicating five destroyers there. We fired six bow tubes, ten-degree spread, at sixteen hundred yards. All failed to detonate!

November 19 at 23:14, we sighted an abandoned Japanese landing craft 5194D, about seventy feet long. We boarded and removed one hand grenade, several packages of English cigarettes, a can of tinned meat, one bottle of beer, and a knapsack full of coarse, white sugar. They had apparently never been used. I assume it had been planned for one of the landings and apparently gotten loose somewhere or another and was floating free at sea.

On December 4, we contacted and sank a destroyer. The torpedoes ran well this particular time. On December 8, we sighted three destroyers on our starboard quarter and four on our port quarter, and commenced approach. We fired four torpedoes--one terrific explosion! On December 11 at 7:20, we cleared the area and set the course for Brisbane; eight torpedoes were left and about twenty-eight hundred gallons of fuel.

The interesting thing about the sinking of this destroyer is that we never actually saw it. Once we were in a firing position, the weather was such . . . and they passed into a strait . . . so, we never actually saw the destroyer. We heard the explosion, but we never claimed that we sank the destroyer. It was all done with SJ radar. We were the first ship in the Navy

to make an attack with SJ radar and sink an enemy. The aviators had followed the convoy into the fog bank and into the strait, and one less destroyer came out than went in. So, when we got to Australia, the squadron commander credited us with the sinking of that destroyer. We never claimed it ourselves. It was written up as a great event, because it was the first time that we were able to prove the SJ radar as a valuable instrument. Most submarines did not believe in their radar and did not use it.

We were extremely fortunate in the FLYING FISH; we had a radarman on board who had set up the two-way communication system for the police force in Los Angeles. This became his baby; and he watered the U-tube in that machine with an eyedropper, and he treated it as though it was his own personal model. He kept it in top shape, so we had great faith--particularly after this--in the SJ radar.

The fact that we left our third patrol area and got to go to Brisbane, Australia, was the greatest morale builder that any of us could possibly have had. The Australians are without a doubt, one of the greatest people I have ever known.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I agree with that. We were in Sydney.

Robert G. Black:

If I had to leave my own country to live and had a lot of money, I would go to Scotland, because I later had duty there and fell in love with Scotland. But if I didn't have any money, I would go to Australia and make it and love it, because that is really a great place to go. The people really liked Americans and treated us in a way that was unbelievable. We were put into an apartment there--the officers were put into apartments, for a two week rest period--the crew was put into a hotel. We had no cooks or any food in the apartments, so we had to go into the local market and get what we wanted to eat. The submarine was completely out because of our refit. I can remember standing in line at a

meat counter, and an Australian coming up and giving me his ration coupon for us to get something to eat while we there. We were invited into homes all the time we were there, and it was really a joyous place to be. We left Brisbane on our third patrol on November 14, for the Solomon Islands.

After our refit in Brisbane, we departed on our fourth patrol to the Philippine Sea, Guam, Formosa-- the shipping lanes. We completed that patrol and returned to Pearl on the twenty-eighth of February 1943. The results: We sank a seven-thousand-ton and a six-thousand-ton AK, and we damaged a seven-hundred-fifty-ton AK. We had fourteen torpedoes left when we arrived and four thousand gallons of fuel. Other than the sinking of the ships I've just indicated, the two AKs--about seven thousand tons and six thousand tons-- and also another type merchant ship of about seventy-five-hundred tons, we had little other action on the fourth patrol and returned to Pearl after that particular run.

While in Pearl, I was detached from the USS FLYING FISH on the sixteenth of March and ordered to report to the commander of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for duty in connection with the readying of the USS BATFISH, SS-310, for sea. She was launched on the fifth of May and commissioned on the twenty third of August 1943. The statistics of the BATFISH were somewhat different than the FLYING FISH in one respect and in one respect only. She had a hull that was one-inch thick rather than 7/8ths-inches thick and could thus go an extra hundred feet in test depth. Other than that, they were basically the same ship--the same type ship. As a matter of fact, the statistics of the ship might be interesting. The submarine's length was 311 feet 6 inches, the beam was 27 feet 3 inches, and the height was 47 feet 3 inches above keel to the top of the periscope sheers. The displacement was 1,526 tons surface, with full water load, and 2,391 tons submerged. Its

range was 10,000 miles. At economical speed, we could stay out seventy-five days if we maintained an economical speed on the surface, which was basically two engines at an eighty to ninety speed combination. The ship cost seven million dollars and was described as a hunter-killer.

The commissioning period was a very interesting period. I was one of the four qualified officers, because I had qualified at this time to go back and commission the ship. Seven officers to eight officers were normally assigned to each new commissioning ship along with the crew of seventy-two. One third of the crew would normally be qualified. That one third would have been drawn from a boat in the Pacific, because each submarine, after a war patrol, lost one third of its crew to come back to new construction; they had to take on, as their third, a new group of submarine school graduates. With new hands and a new skipper, we brought in to being the USS BATFISH.

The BATFISH was commanded by a Lieutenant Commander Wayne Merrill, Naval Academy Class of 1943. He was one of the finest engineering officers I have ever known. In fact I have never known an engineering officer that knew as much about the plants as he knew. He used to bait the rest of us with questions. We would give snap answers; and when they weren't right, he would send us back to our textbook to find out what the hell the right answer was. He was particularly tough on the third officer, Commander Jim Hingson, who always had an answer for every question he was asked, right or wrong. He got sent back to the textbook more than anyone else, because he never learned to say, “I'll go look it up.” He would always give an answer. He was Class of 1939, your classmate. As a matter of fact, Hingson just died the other day.

We had a real problem on board the BATFISH, because the commanding officer of the BATFISH and the executive officer did not like each other. It made it very difficult for us the whole time we served with that group of people on board. There was no open dissension, but it was just known that they didn't like each other and that they didn't make a real effort to get along. As it turned out, I happened to be one of the favorites of the commanding officer. I being a Missourian, which he was, and having made four war patrols with Donahough, who he thought was outstanding, gave me pretty high standing with him. Also, I had been assigned as the TDC operator or assistant TDC operator--TDC means Tactical Data Control Panel. That was the panel that controlled the firing of the torpedo--you worked out the actual setup from the bearing to the depth the torpedo would go out--and that was where the problem was actually worked. Because of this, I was assigned as the primary TDC operator on the BATFISH and the only one allowed to touch it the whole time I was on board.

The commanding officer had one very deep problem; he was basically an alcoholic. He would not drink aboard ship under any circumstance. You could put any amount of whiskey in front of him, and he would never touch it; but ashore he was hell on wheels, and he drank himself beyond anything that is almost imaginable. As a matter of fact, it led to his downfall, and I'll get to that just a little bit later.

When we went through all of our training and got ourselves ready to go, we felt that we were really a top-notch crew in the BATFISH and ready for anything to come. Two days before we departed for our trip to Pearl, the USS DORADO was reported missing off the coast of the Carolinas. It turned out that she had been misidentified by our own aircraft and sunk by U.S. Navy aircraft. So it was then that we all determined once again that we in

submarines had no friends, whether in theory they were friendly, or whether they were enemy; we treated everyone accordingly until we were sure that we had been identified by our own forces.

A short distance out of Panama we sighted a periscope being run up about six hundred fifty yards from us and moving towards us at about five knots. We readied tube number nine and fired a torpedo on a wild sub. Of course we missed, but at the same time, we didn't get fired at by the U-boat. As it turned out, the U-boat probably was not intending to fire at us. She had apparently been in the channel going into Cristobal and had laid mines, because mines were picked up in the channel a couple days later. We entered Cristobal after that, had our time in Panama, and went on through the canal. We had an uneventful trip out to Pearl Harbor. We arrived at Pearl, going through all of our training that had to be done by COMSUBPAC staff before they allowed us to go off on our war patrol.

Our first patrol in the BATFISH, we departed December 11, 1943, from Midway for the coast of Japan. The results of this particular patrol: We made twelve aircraft contacts--three friendly, six unknown, three enemy--and twenty-two ship compacts. We fired eight torpedoes and sank two AK freighters--one nine-thousand tons and the other seven-thousand tons on the 18 January 1944. On the fourteenth, we sighted the battleship YAMATO. We made every effort to get into a firing position, but we failed; we were never close enough to fire a torpedo. So that was what happened to us on our first patrol.

At the end of that patrol, we spent two weeks in Midway at our rest camp. Here we had a real problem with our commanding officer. He stayed intoxicated most of the two weeks, and the only reason I'm willing to put this on record is because it is already on

record. It's in books and in other things, otherwise I would not be telling you this. Because all of us really liked and respected our commanding officer; he just happened to have a problem that he couldn't overcome. Anyway, the officers refused to drink with him, so he would go get the crew out of bed to go drink with him. One night he came back, and he had had too much to drink. The executive officer, the third officer, and myself were all in a room conversing about various things when the commanding officer kicked the door in. He didn't walk in, he kicked the door in and came in and ordered us to have a drink with him. We all refused. He sat down pretty good-natured and started mumbling, and the executive officer turned to me and said, "Let's throw him out the window." You know there was nice soft sand and little gooney birds out there. I opened the windows. We picked our commanding officer up and gently tossed him out the window. He talked to the gooney birds for a while, wandered back to his room, and went to bed. We thought no more about it.

We went on our way, finished our refit and went back on patrol. We left Midway on the twenty second of February and returned on the eleventh of April to go on directly to Pearl Harbor after we stopped at Midway. Again, we went to an area in the South Sea on the southeast coast of Japan. Unsuccessful patrol. Of the nine patrols I made, this was the only unsuccessful one. The only thing we sighted on this patrol was two bodies--Japanese sailors that had been either lost overboard or somehow happened to be in the water--but we found the two bodies floating in the water and they had been dead for some time. We fought the weather the entire time. I ran into the worst storm I have ever run into in my life, the worst typhoon. People were thrown about. As a matter of fact, the third officer was

thrown out of his top bunk even with the iron up. His Naval Academy ring was caught in the exhaust and held his hand, so he didn't come down so hard.

The commanding officer was a beautiful writer, and we received more credit and more comment about his story on the blueberry pies that, because of the storm, were upset on the deck in the galley. The write-up would have indicated that we made a highly successful patrol, but we did actually accept no credit for anything that happened during that period.

In Pearl we were assigned to the Royal Hawaiian, which was our rest camp, and, of course, that was a real wonderful place to stay. I had already been there before, of course, but I noticed that the room I was assigned to had a price of a hundred and some dollars a night. This being back in the year 1943, that was one hell of a price for a room in those days. I didn't believe a room could go for that much, but, anyway, that was the price they had posted on the door.

While we were there, the commanding officer again had far too much to drink, and this time he got completely out of control. He kicked in doors at the Royal Hawaiian and was later charged a dollar a slat for every slat he kicked down. We went through our training period and started on our next patrol (third patrol), but he was really in no shape to be taking us on patrol. In fact, he was not on board at the time we were supposed to sail. At this point we had a new executive officer; the old executive officer had left, and Jim Hingson became our executive officer. So the two of us went out to find him. We found him at the Officers' Club in Pearl Harbor, not the submarine Officers' Club, but at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard Club, where he had a whole series of drinks set up in front of him. He tried to get us to have a drink with him, because he wasn't going anywhere. We

convinced him we had to go to sea. We went back down to the submarine, got underway, and headed for Midway. We did not see the commanding officer until the day before we got into Midway, and then he was completely back to his old self.

We were to arrive in Midway the next day, and as gunnery officer, I had cooked up a story about my torpedoes needing some work done so we could spend the night there once again. Ed Spruance was the officer who met us, and he said, “Don't give any need or any story about staying here for a while. I think you'll be here for sometime." I had no idea what he was talking about. Anyway, we tied up in Midway. We holed up, enjoyed a drink at the bar, and came back. The next morning at eight o'clock a whole contingent came down, and our commanding officer was relieved on the spot by Commander Fife, Jake Fife, who took command.

We had to go through a whole new training period with a new commanding officer. On top of which, Lou Parks--Captain Lou Parks--who later became Admiral Parks, was ordered to investigate the happenings in Pearl Harbor and make a report on Merrill, and whether or not he should be permanently relieved.

We were going to sea everyday working our tails off with a new commanding officer, trying to get him ready to handle us. And at night, we were being interrogated by Parks and a board about the commanding officer and his tactics ashore. When it came my turn to be called in . . . By the way, Hingson had been called in ahead of me, and he told me what he had said about the captain's drinking. He said, "They asked me if I had ever seen my commanding officer drunk," and Hingson said, "Well, I would like to have your definition of him being drunk."

Well I said, "I don't know, you tell me yours."

He said, "Well, I consider a man drunk when he falls on his face in a gutter and is not able to get up, and I've never seen my commanding officer in that state." When they got me in there, they asked me all these questions, and I forgot all about anything having to do with throwing the commanding officer out the window. The executive officer, Maltini, who was about to go with us on this patrol but was being relieved and remaining in Midway, was called in, and he remembered the whole thing. He went through the whole thing, so I got called back in. I was asked to testify, and they said, “Tell me what your rank is."

I said, "Lieutenant junior grade."

They said, "Do you remember a party on such and such a date?"

"Yes, Sir."

"Do you remember the three of you going to the room and having a conversation?"

I said, "Yeah."

"Do you remember your commanding officer coming into the room?"

"Yes, Sir."

The commanding officer is sitting there listening to everything I'm saying. He said, "Do you remember taking part in throwing your commanding officer out the window?'' I thought, 'Oh my God, I'm on trial here.'

I said, "Yes, Sir."

The commanding officer looked up and said, "Oh, it was all done in the spirit of good fun."

Parks said, "Good fun, hell. The BATFISH has the dumbest group of officers on board that I've ever seen in my life. Get the hell out of here. I don't want to see any more of you."

It was then determined after this investigation that Wayne Merrill was not fit to continue as commanding officer of the submarine. He was permanently relieved, and Commander Jake Fife took permanent command. We departed on our third patrol on May 10, 1944, and returned on July 10.

The new commanding officer, while we were in Pearl--and the commanding officer had had too much to drink--went in to see the Commander Submarine Force. He told him, because we had seen no ships in our second run, he wanted to be sent where we saw ships. Well, I had a friend in the operations office who told me that the admiral came in, and it's the only time when he was on the staff, that the admiral ever came in and directed a particular submarine to be sent to a particular area.

We were assigned to what was known as the Rainbow Area, which stretched nearly a thousand miles along the coast of Japan and down to the southwest. The more the commanding officer thought about where he was being assigned, the more he wished he had not gone up and made this request. Before we got underway, we were all directed to make out our final will, so, you can quite imagine how that made us all feel. Anyway, with Fife on board, we started on our patrol.

The results: We sank one MFM-type ship. Now that is a peculiar type of ship. It's mast funnel mast . . . why there was nothing like it at all in the Naval Intelligence Ship Identification Book. It turned out to be a training ship filled with midshipmen. We sank that ship and two AKs, one trawler, and one yacht.

Now, back to the chronology of the trip. On June 10, we made this attack on the MFM ship. We fired number one torpedo and saw a geyser of water shoot up the side. The captain saw many midshipmen running around on the deck, watching the wake coming

toward the ship. It wasn't really maneuvering or doing anything; it was right there close to land. Then after the explosion, we saw midshipmen thrashing around in the water before the water closed over. That ship sunk, almost immediately, after it was hit.

About June 11, while patrolling, we got caught up in fishing net. We were dragging a net almost two miles long. We tried every way we could think of to disengage ourselves, but we couldn't get clear of it. We finally surfaced and sent a commando group up on the deck, and they cut everything loose they could with pocketknives, and we kind of got loose of the net.

On June 18, we attacked and fired three torpedoes and sank an AKA. The ship broke in half. Four depth charges fired away for us and a string of eight were dropped fairly close, but no other damage and no other attacks were made against us.

On June 22, we sighted a thirty-one-hundred-ton AK, newly built. Because we were close to shore and the ship was between us and the coast, we decided to fire a stern tube so we could head for the deep water as soon as we fired. We fired four torpedoes; two torpedoes hit the target, and she sank stern first. We headed for sea going down in what looked to be four hundred feet of water. We heard a groan, a shiver, and a shake; and it was apparent that we had gone aground on the top of a volcanic peak. We didn't stick; we were able to continue. We crept along for about four hours at two hundred feet, while the enemy battered us with depth charges. Finally, after eight hours of submergence, we were able to surface. We found no serious damage resulting form the depth charging, as far as the hull was concerned. We did have a bent shaft and a bent sonar dome as a result of the grounding.

On June 23, we picked up three DDs, two AKs, and two to three LSTs along with air cover. At 10:00 a.m., we spotted a pull-up scope and down came a bomb very close. It shook the submarine from stem to stern. Glass flew from the gauges, cork exploded from the bulkheads like popcorn, and light bulbs shattered. The gyro compass repeater on the bridge was smashed as men were thrown off their feet and against the bulkhead. Then the BATFISH nosed down, and we were able to level off at a hundred feet and gain control again. We came back to periscope depth as soon as it was available, for short observation. We saw DDs searching for us and also spotted two planes. While trying to get into an attack position, the operator reported torpedoes heading at us. The captain ordered, "Hard rudder, flag speed." Two torpedoes thundered past us, and a few minutes later we heard distant explosions of these torpedoes. A new experience to us, having four torpedoes fired at us, rather than being the ones firing them. We took another good depth-charging after this attack.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That bent shaft, did that cause much problem?

Robert G. Black:

The bent shaft caused some but not too much. It caused a ticking as we turned, so we had to be much more careful when we were making any kind of approach with our speed.

On the twenty-first we left the Rainbow Area for Midway, or so we thought. About 10:30, we sighted the mast of two ships: a Japanese trawler and her yacht-type escort. We dove to periscope depth and closed targets. We decided we would do a battle surface, because the draft was not such that it was worth wasting a torpedo. The trawler was about seven hundred tons, and, of course, the yacht was much smaller. I was not only the torpedo officer, but also the gunnery officer, and we had never done a battle surface. I figured it was

time that I got to exercise my skills here as the gunnery officer, and I pleaded with the commanding officer to do a battle surface. Executive Officer Jim Hingson was at the same time pleading with him not to do the battle surface, because (as you know) one hole from a fifty-caliber machine gun bullet in the hull of a submarine puts it out of operation. However, my pleading prevailed and the commanding officer decided that we would do a battle surface.

A battle surface is done in that the submarine wants to pop to the surface as fast as it possibly can once it's ready to do this battle surface. So when we got ready to surface, we held it down as long as possible, while we were blowing all the tanks. Then we popped up just like a cork; and when we popped up, we were about fifteen-hundred yards from the target. I was the first on the deck up over the bridge and down on the deck with the gun.

The gun crews were there. We had five-inch twenty-threes, five inch twenty fives. Our very first shot hit the trawler. They were very aggressive. The yacht could have gotten away but never attempted to. We kept firing, and they kept firing. We ended up sinking both of the ships. The yacht was able to get close enough--and once again it could have gotten away but decided to stay and fight it out--but, it got close enough firing its machine gun to hit one of the gun crew in the leg. It was the one man who did not want to be in the gun crew. As it turned out, however, he became very happy. As a result of being hit, the bullet was taken from his leg by the corpsmen, mounted on a plaque, verses were made up on the man, and he got assigned to new construction back in the States when the patrol was over. So he was very happy to be part of our gun crew.

But it was a real experience, and one which I will always remember. We actually had pictures of firing on the larger target--showing the helmsman being hit and taking a flip

and coming out through the window. It was a large window shield in front of the helm, and he actually came sailing out through there and into the water. No one, as far as we know, was left alive in this exercise.

The battle surface was the last battle action we had during this patrol. We received the good news that we were going to leave this patrol and head for Perth, Australia. If we thought Brisbane was great, Perth was twice as good. The crew was absolutely delighted. We arrived in Perth and had our two weeks at a hotel they had set aside for us for that particular time. We did our training there, and it was then that we started out on our fourth patrol.

H.A.I. Sugg:

My next younger brother was in a submarine based in Perth. It was the BREAM. He had much the same thing to say about Perth and liberties there.

Robert G. Black:

At the end of that, I misstated going into Perth at the end of the third patrol. The end of the third patrol and after the battle surface was the last of the contacts we had with the enemy until we entered Midway, where we refitted once again. After refitting in Midway, then we were ordered on our fourth patrol. It took us to the Caroline Islands and Palau. There, after a very eventful encounter with a destroyer which we sunk, we took on lifeguard duty at two or three different times. The planes at that time were beginning to bomb the various islands in the South Pacific, and we had lifeguard duty assigned on three different occasions. The planes were coming in and dropping their bombs on the island. Fortunately, none of the pilots was shot down, so we didn't have to rescue anyone from the water.

The one destroyer that we sank was certainly a fine target for us. We also tried to sink a PC. We made a quick setup on her at one point, but we failed to get a hit, so we were not successful. On August 30, from this patrol, we received orders from COMSUBPAC to

leave our area. Before this had happened. . . . In our area we had located, along with the destroyer we sank, one destroyer aground, one AK aground (being guarded by two PCs and planes), and an armed sampan. Teyhhethey had gone aground because that area was not charted well. We made two or three attempts, but the weather was terrible, to get in and try to sink the AK. In fact, it turned out that there was no point in doing this, because she was so high and dry our torpedoes would never have hit her, and she was never going to be back at sea again. As I indicated earlier, our haul for that particular run was not as great as we would have liked it to have been. We got the MFF-type ship, the two AKs, and the trawler. Ok, that's all for right now.

H.A.I. Sugg:

The patrol of the BATFISH?

Robert G. Black:

I indicated as I closed out the third patrol that we went into Perth, which was wrong. We actually went back to Midway and refitted in Midway. We left Midway on August 1, 1944, and arrived in Perth on 12 September, 1944 on the BATFISH.

The area that we were assigned this time included the Caroline Islands and Palau. We sank one destroyer and had lifeguard duty there. Did I go through this?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes.

Robert G. Black:

On August 3, after having left the grounded ships, we received orders from COMSUBPAC to change our operating area, and we headed south. Heading south among the islands, we were close in when we heard a rumbling down along our side. We determined that we were going through a minefield. We slowed to as slow as we could go. It seemed like we were creeping in inches and were taking weeks to get through. We were afraid that the mine chain would be caught up on the propeller guard and be pulled into the

propeller and explode. However, we were fortunate--the chain slipped by. We backed off as soon as we were clear and got the hell out of there as fast as we could.

On the eighth of September, we crossed the equator and thus went through the initiation by the “shellbacks” of the “pollywogs”--to introduce our new members into the “Royal and Ancient Order of the Deep.” And I can tell you we had a thorough initiation. We shaved the people's heads and really gave them a bad time. We really had a good time from there on, getting on into Perth. As I said, Perth was one of the highlights of our whole life. I thoroughly love Perth; it's one of my very favorite spots in the whole world.

While I was there I was adopted by a man and a family who were very close, and this man owned a main hotel in Perth. I was invited to the hotel every Saturday that we were in port and to the races first in the afternoon. The first horserace I ever attended was in Australia, and I found that they were all crooked. As a matter of a fact, I followed my host over to the fence, and each time a jockey would walk over and he would say, "Put so much money on so and so,"

I'd say, "Put some on for me, too!" I never hardly failed to lose the whole time I was able to do this. For Christmas, I was invited to a beautiful dinner with the Australians while at one of my points in Perth. Well, this was later in time, so I shouldn't get to that right now.

While I was in Perth, the commanding officer of the USS GUITTARO lost his executive officer to new construction--an officer, from the Class of 1938, being sent back to command a submarine. The commanding officer of the GUITTARO was Enrico de Almo Haskins, who had been the executive officer of the FLYING FISH when I first reported aboard. He requested from my commanding officer that I be released from the BATFISH to

become his executive officer. Then, I guess, I was the junior executive officer when released, and was made executive officer in the Pacific Fleet. It was a great honor to me to get this position, and I thoroughly enjoyed serving under (not all of the commanding officers I had) but particularly serving under Haskins. I've never known a man more loved by his crew, and I've never known a man that could handle a ship the way he could handle a ship. He never came in except at full to the pier and always backed emergency(?).

H.A.I. Sugg:

Were you a lieutenant by now?

Robert G. Black:

Yes, I was a lieutenant by now. As a matter of fact, I was made lieutenant while I was in the BATFISH. Anyway, he asked if I would be his exec. My commanding officer in the BATFISH did not really want to release me and he said, "You know, I'm going to send you home after one more run. You'll get to go back to the States to new construction."

And my new commanding officer-to-be said, "I will guarantee if he'll be my executive officer for this run, he will get to go back to the States after this run."

I said, "Then I'm going to go and be the executive officer."

So, anyway, we departed Perth on October 18 in company with the BATFISH. Here I am with my old FISH, my old submarine and my new submarine, and we go out in company and go as far as Exmouth Gulf together. At Exmouth Gulf we refueled and restocked, and then we each went our own way.

We were ordered to go to an area in the East Indies and just south of the Philippine Islands. Going between the Lombak and Bali Strait, you had to go through on the surface, because there is a current going through there never less than six knots--always flowing to the south. There is no way a submarine (that can make nine knots maximum speed for thirty minutes) can go through there submerged. So, you had to go through on the surface. So

what you did was play a cat-and-mouse game, varying speed, course, and everything, because as you approached, you knew that both islands were manned by the Japanese with guns. You did all kinds of maneuvers to try to confuse them. Well, we had done all this, but, unfortunately, we had a man who was ill on board, and he died just before we got to the Strait. So we turned around, and headed back south. We held a burial at sea. Commander Haskins did an outstanding job as chaplain in conducting the funeral. There was no way we could hold this body during that whole period. So we held a funeral at sea, turned around, and went back through the Strait. We were able to get through, going full power with no shots fired. We went on up to our patrol area.

This is the most productive patrol that I made. We sank, on this patrol just off the Philippines, four ships: one was a troop transport, one was an ammunition ship, two AKs, and we got credit for damaging a heavy cruiser. When we hit the ammunition ship, we were very close and there was a hell of an explosion. The commanding officer maintains, and I was standing next to the periscope when it happened, that the explosion was so great that it blew the water away from the periscope, and that the gas actually came down the periscope shears. I actually saw a blue flame come down that shear. They say it can't happen, but I can only tell you what I saw. He believed that there was enough blown away from us . . . and the fact that we dropped a hundred feet almost immediately. How our diving officer ever regained control, I will never know. We all feel that we were very fortunate to have lived through that, but it was the number one patrol that I made. It was on this patrol that I was awarded my second Silver Star. That was the biggest thing that we did during this patrol. We were the last submarine to contact the Japanese fleet coming from the south to the Philippines for the final big battle. What was the name of that battle?

H.A.I. Sugg:

They came through the straits there before Halsey?

Robert G. Black:

Yes, well, we gave them the last course. Nobody knew for sure whether they were going to the west or to the east. We gave them the last course that was given, so that our Fleet was ready to intercept them when they came around. For this, we were given as much credit as anything else that we did on the patrol.

I enjoyed my days on that ship. I would say that the people in the GUITTARO really loved the commanding officer to the point that they composed songs to him and wrote verses about him. The officers all tried to emulate him. He was a womanizer. Although he was married, he still had girlfriends in every port. He was a very handsome man, and one fine commanding officer. This was the last patrol I made. I am very fortunate (I'll have to say) to be alive. At least five different times during my patrol days, I felt that we were not going to come out of the situation we were in.

The only humorous one was when my commanding officer told me that my life wasn't worth a plugged nickel. Although it wasn't humorous in what was really happening, it was humorous as far as the situation was concerned at the moment. I say that war is hell; but if you have to be in it, you might as well enjoy it as much as you can, and I wouldn't take anything from the experience I had.

Oh yes, at the end of this patrol we returned to Perth. The commanding officer was detached; therefore, the new executive officer could not be detached. However, the commanding officer went up to the squadron commander and told him he had given his word that I would be detached; therefore, it had to be done. I was detached and ordered back to the States to New London, Connecticut. I did not want to stay in New London, Connecticut. Then, I got ordered to Key West, Florida, and was given command of the

USR20, a submarine commissioned in 1917, decommissioned in 1919, recommissioned in 1936 or 1937 (I believe), and was used as a training ship off Key West. I wanted to go to Key West, and that's where they sent me. You could have actually taken a hammer and knocked a hole in the hull of that submarine, it was so rusty.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I remember when I went to the PCO course down there.

Robert G. Black:

We were assigned as targets for the sonar school. We had to go to sea everyday at six o'clock. We'd get to our assigned area and release a towed buoy, go to about sixty-five feet, and, then, I would turn in and stay in my bunk all day. When it was time to surface, they had to give me a call to go surface. I'd come in and party all night, every night, and then we would rest up, commission another submarine, and go back to sea.

I think I fired ten torpedo shots from the R20 while I was commanding officer, and I never missed a target once. As a matter of fact, they were placing bets on my shooting before the end of my command. Well, it was very simple. I led every target by seventeen degrees and got so close, they couldn't miss. There wasn't any science or skill to it at all. The squadron commander gave me hell for getting too close. Well, I said, "I didn't miss any of those."

While I was there, World War II ended, and I decommissioned the R20 in December of 1945. Then I reported to the base for duty, awaiting assignment to another submarine. Now that takes care of the war, do you want to go ahead with the rest of this?

TAPE 2, SIDE ARobert G. Black:

In our first session, we covered my involvement in World War Two. We ended with my decommissioning the US R20 and subsequent transfer to the submarine base in Key West, Florida, where I was interviewed and selected for transfer from the reserve status to

the regular Navy. Making the decision to transfer to the regular Navy did not come easy. I had gone to Louisiana State University on a scholarship from the university and had an apprenticeship job as a junior geologist with the Sinclair Oil Company. The senior geologist for the oil company kept calling me and urging me to return, while the Navy kept pressure on me to become a career officer. After very careful consideration and many long conversations with my wife, the former Jane Forbes of Greenville, North Carolina, whom I married August the seventh while commissioning the BATFISH, I made the decision to stay in the Navy. I never looked back. My time at the submarine base lasted two months, from September through November 1945. During my short stay at the submarine base, I was selected for and promoted to lieutenant commander. The USS CLAMAGORE, SS-343, had passed through the Panama Canal and was in route to Pearl Harbor when . . . .

H.A.I. Sugg:

Could you spell the name of the ship or boat?

Robert G. Black:

The USS CLAMAGORE, SS-343.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Thank you.

Robert G. Black:

It passed through the canal in route to Pearl Harbor when World War II ended. Even though she was well on her way, she was ordered to turn around and return to Key West. Shortly after reaching Key West, CLAMAGORE's executive officer was detached, and I was ordered as the replacement. I served as xo and navigator from late November until June of 1946. In June of 1946, I was ordered to the Navy General Line School. This school was established to better prepare those of us who had transferred from the Reserves to pursue a career in the regular Navy. The courses covered what we missed by not attending the Naval Academy. There were over six hundred officers attending the year that I was there as a

student. Almost all of the officers were either commander or captain in rank. It was a highly informative year and most beneficial for all who attended.

Upon completion of the General Line School, I was ordered back to the USS CLAMAGORE to serve as executive officer and navigator for the second time. I served until June 1949. My orders then took me back to the General Line School, this time to serve as an instructor in International Relations. To fully prepare myself for this assignment I was sent to the United Nations headquarters, then located at Lake Success in Long Island, New York. While there I got to meet Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, the U.S. representative, as well as Jacob Mallad, the Russian representative. When ordered to the Line School, I expected my tour would last two years. However, during the summer of 1950, the Korean War started. Even though the new students had already started to arrive, it was decided to close the school for the duration of the Korean conflict. Those students who had just arrived were ordered to fill billets required by the new development. The Line School staff was dissolved and its members were ordered back to sea, with one exception. The Line School also trained WAVE officers for entry into the Navy. Twenty-eight young women, college graduates, were selected and ordered to Newport twice a year for six months, for indoctrination training. The commanding officer of the Line School was ordered to take command of the newly established Naval Recruiting Center in Newport, Rhode Island, while retaining command of the Line School. I was selected to remain with the school and was given a new title, officer in charge of WAVE officer training. All of the actual instruction for the women was carried out by WAVE officers, with the exception of me. I continued to instruct them in International Relations. I enjoyed the assignment while it lasted, but all good things must come to an end.

In January 1951, I was ordered to New London, Connecticut, to take command of the USS FLYING FISH, SS-229 . Nine years earlier, I had reported aboard the FLYING FISH and found myself as the junior officer aboard. What a thrill it was to assume command of my first ship! The FLYING FISH had been greatly reconfigured from her World War II sleek lines. Near the end of the war, the Germans had developed a much more advanced sonar system than we had. The Navy removed the sonar suite from a captured German submarine and had it installed in the FLYING FISH. A very high elliptical array completely surrounded the conning towers, and a longitudinal array ran the length of the submarine on the starboard side. I could only tie up portside in port and had to have a step built on the bridge, so the officers of the deck could see over the elliptical array. At that time our Navy was building and installing low far-listening systems; and with our German gear, we became strictly a research ship. Every time we went to sea, we had a group of Navy scientists from the Naval Underwater Sound Lab on board, who operated the gear. While operating in the New London area, my job was to take the FLYING FISH to the edge of the continental shelf and set her on the sea floor in about 170 feet of water. Then, I would secure all of the operating gear possible and let the scientists do their thing. At intervals we sailed to Bermuda, where we spent our time working as target for the personnel. Our trips to Bermuda usually lasted about six weeks, and we learned to enjoy the island.

Even though we were a research ship, we were not excused from our annual readiness inspections. This called for the division commander to ride and observe how we conducted the required exercises. The destroyer from Newport was assigned to act as target for my torpedo shoot, and I to act as sonar target for his sonar training.

My torpedo shoot went well, and I was awarded a hit with the dummy weapon. After that setup, I would be his sonar target setup. All went well until the destroyer was about two hundred yards away. All of a sudden, I had a call from the maneuvering room saying, "Captain, we are losing turns on the starboard screw." Then, I heard a scraping sound on the port side of the ship. I got on the underwater telephone and told the CO of the destroyer that I needed to surface immediately.

He came back with the message, "You can't surface now, there's a small fishing boat over the top of you." The fishing boat cleared itself as soon as possible, and I was given the "ok" to surface. The fisherman was dragging the sea floor with his net, and he had caught us. We had over five hundred feet of steel cable wrapped around our bow and conning tower.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That was some catch, wasn't it?

Robert G. Black:

The submarine wound around the conning tower and the starboard screw, along with a lot of netting. We limped into port with a damaged prop and shaft. No damage was done to the fishing boat except for the lost net. The fisherman came to see me the next day, and he said, "We were fishing away when my mate yelled, 'Captain, we're going ahead two thirds, and the boat is going backwards.' With that, I grabbed an axe and cut the net rigging free." As a result of being caught up in the net, the FLYING FISH made the local news. Lowell Thomas on his radio news said, "New London local fisherman has caught his largest fish ever, the USS FLYING FISH." The USS FLYING FISH story even made it in Time Magazine.

After a year on the FLYING FISH doing research, the Navy decided it was time for me to command a more normal attack submarine. So in February 1952, I was ordered to

take command of the USS SABLEFISH. This was a delightful tour highlighted by a three-month deployment to the Mediterranean. We sailed from New London to Malta. Liberty ports were terrible, with the exception of the French Riviera. While anchored in Cannes, I received a message ordering me to a dinner reception being given by the mayor of Nice. The mayor's invitations had failed to state who was being honored at the reception. The admirals, the captains, and the commanders decided that they had better things to do; so all three lieutenant commanders and submarine commanding officers were ordered to go to the reception.

Transportation was waiting for us at the pier. As scheduled, the driver awaited us when we reached the pier, but he did not know the route to Nice. After a few small detours, we reached the gated mayor's palace, a little late. We jumped out of the car at the curb and rushed up to the palace. I was leading the group, and just as we were about to reach the entrance, a small British car pulled up and stopped. The window was down and in an instant, I heard a voice, and a head appeared, "Good evening, young gentlemen," the voice said, "How are you?" It was Sir Winston Churchill. I was so excited that I didn't answer.

I just turned to the other two officers and shouted, "Churchill." He just laughed, got out of the car, entered the palace, and prepared to receive the invited guests. Since the mayor was giving the party in his honor, we delayed our entry for a few minutes. When we entered, first in the receiving line were Lord and Lady Mountbatten. They were without a doubt the most regal couple I have ever met. Then, we were introduced to Sir Winston properly and passed on through the line. As soon as Sir Winston had greeted all the guests in the receiving line and it had broken up, he walked over and started talking to the three of us about his military life and the day he escorted the king on a submarine. What a thrill for

all of us. He also took time to talk to the junior U.S. aviators who had been ordered to attend. When the word got back to the Fleet that the reception had been given for Churchill, those who refused the invitation couldn't believe that the three of us had been so lucky.

In January 1953 I was relieved.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Excuse me, that was late 1952?

Robert G. Black:

Yes. That was 1952. In January 1953 I was relieved of command of the SABLEFISH and ordered to the Bureau of Naval Personnel, where I served as the head of the Enlisted School of Instructors. I held this position until June 1955. My section selected all the enlisted instructors and issued orders for them to report to the appropriate schools. This was a highly desirable duty because instructorships were three-year shore duty tours. We also distributed the graduates of each school to the Fleet. In the case of the submarine school, I personally divided each class between the Atlantic and Pacific Fleet to meet their needs.

This period of time was especially difficult for the Navy. Louis Johnson, the Secretary of the Navy, did not seem to have a very good understanding of our problems. We were very short of technical personnel, and recruiting was going so poorly that for once the Navy had to resort to the draft to meet it's requirements. Looking at the Navy's overall personnel strength, we were over-staffed on the higher enlisted ratings. For example, we had twenty-five hundred excess chief aviation machinist mates yet were a hundred short in the highly technical ratings. Something had to be done, so I called for a sampling of the records of our senior excess ratings. Many of these people's records showed that they possessed the qualifications to enter more technical fields. For example, one chief cook had scored the top test scores that could be made when he had been tested for entry into the

Navy. Many of the senior ratings were being assigned to duties completely outside of their specialty because all required billets were filled. Thus, they became bored and were simply marking time as they marched toward a twenty-year retirement.

I came up with the idea that we should establish a special training program in our electronic and fire control schools for highly qualified excess personnel to be retrained in these special technical ratings. Upon completion, they would be transferred to the new rated at the same rate that they held when they entered the school. For example, a chief transferred from the old to the new rated as a chief. The proposal was approved by my immediate superior. I then prepared all the necessary paperwork announcing the program, and an ALLNAV to the Fleet was released requesting qualified volunteers to apply directly to NAVPERS. Within a month after the ALLNAV went out, my desk had over five thousand volunteers. The EC, ET, and FT schools had to institute night school to handle the influx. The program was known as the Horizontal Transfer Program. This program did not solve all of our problems in those ratings, but it certainly helped the Navy overall by reducing some of our excesses--by putting the newly trained personnel where they were really most needed.

It was during this period that Captain Rickover and I crossed paths for the first time. He had stated he was going to select all the personnel for his nuclear program, both officers and enlisted. He did, in fact, select all the officers that entered the program until he retired; but after selecting the first enlisted men for the new program, he turned the job over to NAVPERS, which in fact went to me. I selected the crews for the NAUTILUS , SEAWOLF, and the SKATE except for the first ten men, and I dealt directly with Rickover in BuShips. I had very few problems with him at this point. My big problem came from the fact that I had

more qualified submariners volunteering for assignment to nuclear submarines than I had those to offer. I also had to be prepared to explain why I had selected one individual over the other. It is not always easy, but I set up a system and kept notes to help. I think I was only overruled twice with individuals who had a special past connection with Rickover or someone on his staff.

During this tour, I was selected for commander. In July 1955, I reported to Commander Submarine Force Atlantic Fleet in New London, Connecticut, for duty as force personnel officer. My tour in BUPERS had focused my views on the personnel field, so I was delighted to be assigned to this building. During this two-year tour I faced the normal problems confronting the Navy with one exception: I had Rickover's demands to deal with again.

H.A.I. Sugg:

"Thank God," the rest of the Navy said, "Thank God it's you, not us!"

Robert G. Black:

Rickover had been allowed to select any officer he desired, and all of his enlisted requirements had been met according to the criteria he had set down. However, as his program was growing, he placed too many demands on us, for our Fleet-experienced enlisted personnel. He would not accept newly trained submarine school graduates. All personnel for his program had to have some Fleet experience. The problem finally came to a head when he called for more IC electricians than the force could reasonably provide without damaging the readiness of our diesel fleet.

I reported this fact to our force commander, Admiral Frank Watkins. He asked if I had any solution in mind. I said, "I recommend that BUPERS require Rickover to accept a certain number of newly trained junior ratings coming out of the IC electrician school and other technical schools, and their initial submarine training take place on the nuclear

submarine." That appeared to be a reasonable solution, and he directed me to prepare a dispatch to BUPERS outlining the proposal.

About three days after the message was sent, the admiral was ordered to Washington to explain our position to BUPERS. His men and I were to accompany the admiral, and I would be expected to explain and defend the submarine force position. This is where my training in BUPERS stood me in good stead. I understood the technicalities involved in making such a presentation to best present the case.

Upon entering, I noted that the chief of BUPERS office, then Vice Admiral Holloway, Sr., was surrounded by about twenty-five captains and admirals, including Admiral Rickover. I was greeted in a most cordial manner, and my boss stated that I would make the necessary presentation. I rolled out my charts, set them up for all to view, and started my presentation. I had talked for about five minutes, when I was stopped by Admiral Holloway. He looked all around at his staff and said, "I have said before and I say again, all force personnel officers should have had a tour of duty before being assigned to such a position. I understand everything he is saying and he understands everything I will have to say. Now continue, Commander."

I was about two-thirds way through my presentation, where at this point I had started to make my recommendations, when Admiral Rickover interrupted by saying, "Admiral Holloway, am I going to be able to say anything? If not, why in hell did you ask me over here?"

Admiral Holloway answered, "Rick, you can say any damn thing you want to say, but when you are through, we are going to do exactly what Black has recommended." The battle was won, but the war was not over.

A few days later, Admiral Rickover called a meeting of the three nuclear submarine commanding officers to come to Washington to try to determine what was to be done to this upstart Commander Black. I was told later that he said that I was an interloper in his program and that something had to be done to get rid of me. All three of the skippers answered by saying that he was wrong. They said that I had predicted a problem would arise long before it developed, and that the solution offered was the best that could be provided. He then wondered if I had been alienated to the point where I would not do my best for his program. They assured him I would not operate in that manner. Thus, I finished my tour with no more interference from the nuclear group.

In July 1957, I assumed command of Submarine Division 102, located in New London, Connecticut. Two incidents stand out as highly unusual. On the day I assumed command, one of the submarines assigned to my division was conducting a special exercise under the operational command of the force commander who had assumed full responsibility for all aspects of the exercise. On the very first night of my command, the submarine assigned to my command and another submarine with which it was exercising collided, submerged. A considerable amount of damage was done to both submarines, but luckily there were no personnel injuries. I learned about this on my first full day as a division commander.

H.A.I. Sugg: