| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #117 | |

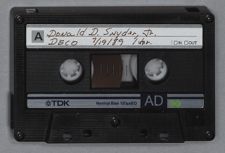

| Donald D. Snyder, Jr. | |

| Concord, New Hampshire | |

| Destroyer Escort Commanding Officers (DECO)/USNA Class of 1938 | |

| July 19, 1989 | |

| INTERVIEW #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you would, start off with something from your background prior to World War II. Explain where you grew up, where you were educated, and how you got a Navy commission.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I was born in Albany, New York, in 1916. I later lived in Vermont and then Massachusetts. I was educated in the public schools of Gardner, Massachusetts.

In 1933, I got a four-year scholarship to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, (R.P.I.). But prior to that, during my high school years, I was always interested in the Navy. I used to go to a friend's house where he had his uncle's Lucky Bag. I'd look through that and say, "I want to go to the Naval Academy."

I took many competitive examinations and never heard a thing from the Naval Academy. At Christmas time, when I came home from R.P.I. for Christmas vacation, my father said, "How would you like to take another exam for the Naval Academy?"

I said, "Oh, I've taken so many of those exams and I never hear about them. Besides, I haven't had ancient history for four years and that's one of the main exam principals."

He said, "Well, I've thought of that. I've got an ancient history book from high school. The exam is on Monday morning and you've got the weekend to study."

I said, "Well, I don't really think I want to do it again."

He said, "Well, it's the middle of the Depression and I can't help you anymore, so I think it's a good idea."

So I took the exam and I didn't hear anything until April when I got a message from my father saying I had been appointed principal to the Naval Academy by a Democratic senator. My family was full of staunch Republicans, so that was an amazing thing.

I entered the Naval Academy in June of 1934 and graduated in 1938. I was commissioned as an ensign and served on the battleship TENNESSEE for two years. At that time, you had a probationary commission for two years. If you had anything mentally, morally, or physically wrong with you, they could revoke your commission. On graduation, my vision was poor, so I was allowed two years to strengthen my sight.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any comments about the Naval Academy itself during your stay there?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I loved it. It was a great experience for me. It was a lot of work, but I enjoyed it. I enjoyed the cruises and everything else about the Academy. I was what you'd really call "Gung-ho Navy."

Donald R. Lennon:

Was Uncle Beanie (Lt. Barrett) there at the time you went there?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Uncle Beanie . . . that doesn't ring a bell with me.

Donald R. Lennon:

One of the legends around that the Class of 1941 members always talk about is Uncle Beanie. He was one of the naval officers in charge at that time.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

No, he apparently came after I left. David Foote Sellers was the Superintendent at that time.

There were about one hundred of us in my class who had defective vision. A good many of them memorized the eye chart and were able to stay in. Also, at that time, many of my classmates at the Naval Academy had two or three years of college. Looking at the outlook for getting a job or being able to get an appointment, they decided to go to the Naval Academy. They were probably three maybe even four years older than I was, because I entered in 1934 and I had turned eighteen in August.

At the end of the two years, my vision still wasn't up to par. I applied for the Civil Engineers, the Supply Corps, and the Naval Architecture (engineering duty only), which was highly endorsed by the commanding officer of the TENNESSEE. The comment of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery always was, "This officer is physically disqualified."

Donald R. Lennon:

This was 1940 by now, was it not?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

That's right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the TENNESSEE?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

She was in the Bremerton Navy Yard at the time that I was detached.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you go while you were on the TENNESSEE?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

It had been operating on the West Coast. However, it had come through the Panama Canal to the East Coast for the opening of the World's Fair in 1939. Then Germany invaded Poland right at that time. There was mobilization and the Fleet was ordered back through the Canal to get into the Pacific in case of war. The TENNESSEE

was fortunate in that it had unloaded its ammunition at Iona Island. We had no ammunition, so we had to stay anchored in the Hudson River while the rest of the Fleet sailed west. New York society lavished their best hospitality on our crew. The young officers attended parties night after night after night. The TENNESSEE eventually went back through the Canal alone to the West Coast and had her overhaul. I guess she was in for a four-year overhaul. We were there for three months.

I was sent back to Gardner, Massachusetts, after my commission was revoked. When I got home, there was a message from the Navy Department saying, "Well, if you'll accept a commission in the Reserve, we'll send you right back to the TENNESSEE. You can have the same job you had when you were on the TENNESSEE." I was so goddamned mad at them that I said, "To hell with you. I'm not gonna do it."

I got a job with Haskelite Manufacturing Corporation in Grand Rapids, Michigan. They were making three-eighths inch birch plywood for the British Air Ministry, because the British were making training planes out of plywood. We were also making about an inch-and-a-quarter or inch-and-a-half mahogany plywood for the Higgins Boat Company to build PT boats.

I had a friend that I'd met on the TENNESSEE who was in the Reserve from the California ROTC. He had been assigned to the Great Lakes as an aide to the admiral. We spent a weekend together. He said, "Don, you'd better make up your mind to come back. It's not a question of if we're going to get in the war; it's just a question of how soon. They've got a good job for you over at the Northwestern University V-7 course. They need a celestial navigation teacher."

Well, I had visions of being "Mr. Chips," which included ivy covered buildings and teaching college kids.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this early in 1941?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

No, it was in the fall of 1940. This was the summer and school was going to open up in September. I said, "Well, I'll think about it."

Well, if I accepted them, I had orders to go to Chicago Monday morning. I went to Chicago and taught celestial navigation and seamanship for about a year and a half.

We began to feel that we really didn't know what was going on in the Fleet anymore. Everything was changing. LORAN had come in, along with other things. I started agitating to get back to sea again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Actually, when you left the TENNESSEE, it probably didn't even have radar, did it?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Nope, I imagine they put it on at that time. They still had the old cage mast. I thought I was going to get to go to sea, when all of a sudden I got transferred to start up a new school at Princeton University as head of the Department of Ordnance and Gunnery.

I don't know whether you ever knew Princeton or not, but at that time they had an old gym with a great big tower on it. I had an office way up in the tower. It was the best office in the campus.

Finally, one of my friends from Chicago at Northwestern was assigned to a minesweeper. He lost his exec, so he wangled a job for me as exec on the minesweeper.

The minesweeper was built in Nashville, Tennessee, and floated down the river to New Orleans, where we picked it up. I had the worst experience on that vessel. When we went out the mouth of the river, I got seasick on Thanksgiving eve. I was sick

continuously, every minute at sea until April when, all of a sudden, it disappeared. It was the most amazing thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was April of 1942.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I would say it was April of 1942.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the name and number of the minesweeper?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

It was the AM-97, the FIERCE.

We trained in Portland, Maine, and were on our way to the North African invasion. There was a command in Portland that trained battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, DEs, and minesweepers. There were six ships on our way to the North African invasion. The admiral in North Africa became alarmed because a German submarine had laid some mines off Halifax, so two of us were told, "You'll stay here and sweep the channel early in the morning. Then you'll patrol all night off the coast of Maine." I think the rest of the ships were lost in the North African invasion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Really.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Being on the way to a major operation and being saved was my "first great experience" of the war. I've always said that the WACS and the WAVES were there before I got around to any place.

Then I was transferred.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you actually locate any mines off Nova Scotia?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

No, this was at the Gulf of Maine from Monhegan Island down to Boone Island (?) probably.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you just patrolled back and forth and found nothing.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Then I was transferred to command. One of the interesting experiences I had on the minesweeper FIERCE was, as exec, the commanding officer never let me touch the vessel. I made up my mind that when I got to be commanding officer, every officer would be qualified to handle the ship in every condition.

Donald R. Lennon:

I thought one of the primary duties was to train your exec officer so they'd be prepared.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

It is! This guy was a kook. I think he made admiral, but only in the Reserve. I remember he figured the secret of the "eternal vigor" was to eat six shredded wheat biscuits every morning. That was his breakfast every morning.

Donald R. Lennon:

Exactly six.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

He figured he was going to sire children when he was ninety as a result of this regimen. He was really a fitness nut.

I got command of the FIDELITY and remained there for about six months until I was transferred to the Sub Chaser Training Center in Miami.

You probably heard about "Old Blood and Guts" down there. I've forgotten his last name. I never thought of him as anybody but "Old Blood and Guts," because his favorite story was about the lifeboat rocking in the sea with nothing but blood and guts in it. The German submarine had used machine guns on the survivors in a lifeboat. That story was to get us in the frame of mind where we'd really go after the Germans.

When you graduated from the Sub Chaser Training Center, they had a review of you and your record at the "Long Table" covered with green baize felt and surrounded by captains. The captains would look at you and say, "Okay, Lieutenant, what do you want?

What kind of duty do you want?" Almost everybody was frightened of the board. People usually asked for one or two jobs lower than what they really wanted.

I said, "I want command of a five-inch turbine-geared DE."

Their mouths dropped open. They couldn't believe it. I don't believe anybody ever really told them what they wanted. I specified what was the latest ship that had turbine engines. It was faster and had two five-inch mounts against the three-inch guns the others had. Also, it had four torpedo tubes and "hedgehogs" and so, basically the whole "smear" of weapons.

Well, then I didn't hear from anybody for two weeks. I had the greatest life in Miami. I called at eight o'clock in the morning and again at five o'clock in the afternoon to find out if my orders had come in. The rest of the time was mine. I lolled on the beach. I went to Hialeah Park and to the races. I really lived it up. Then I got orders to command the TENNESSEE at Orange, Texas.

Donald R. Lennon:

Command of the TENNESSEE?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Oh, sorry! The ROBERT BRAZIER, DE-345.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we get into the BRAZIER, what was the nature of your training at the SubChaser school? What did they really train you in?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

They trained you in all sorts of things such as seamanship, signalling, use of the ASDIC, and radar. You were eventually sent to Key West for actual training with submarines. It was a thorough training in all phases such as how to make out a watch bill, etc. Of course, most of the officers there were not Naval Academy graduates, which may have accounted for why I got the command I wanted. It was a fact that I was ahead of most of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had already been CO?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

On a battleship, though.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you'd been CO on a minesweeper.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Yes, on a minesweeper.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had duty on a battleship and other things, right?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Yes, I probably had more experience at sea than most of the officers there.

I got assigned to the ROBERT BRAZIER at Orange, Texas, up the Sabine River about forty miles inland.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that where they were building them?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

They were building and side launching them. It was a relatively narrow river. They did a magnificent job, though. We went down the river and that was my first experience with a pilot. We went to Galveston and into the drydock to have our bottom checked. As we were coming out of drydock, one of the crewmembers lost his grip on the stern hawser and it wrapped around the screw. We had to go back. It didn't do any damage, but nevertheless it was bad.

We went on to Bermuda for training for six weeks. Bermuda was the hellhole of the commanding officers' training.

On the northwest side of Bermuda, there's a very long tortuous channel through the reef. The DEs would anchor in Hamilton Harbor every night and get underway in the morning in a long line. If somebody had some trouble, you were at the mercy of the other ships. It was said many DE skippers ran aground on the reefs because of the conditions, but we all got through there. Oh, and I've never been to Bermuda! I was there for six weeks and never went ashore!

Donald R. Lennon:

You never went ashore?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I never went ashore because we were training, but the crew could go ashore. The COs were getting ready for the next day's training.

Donald R. Lennon:

We have Admiral Jules James' papers. Admiral James was a commander at Hamilton for several years. The papers include a map of the Hamilton Harbor. I'm familiar with Bermuda from that perspective.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I believe we then went to Charleston, up to Boston, and then to Portland for gunnery training. It was in Portland where we were finally assigned to an Escort Division. We had four destroyers, six DEs, and a tanker. We were assigned to escort high octane tankers for the Air Force to the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

From out of where?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I think we picked them up from along the coast from places like Norfolk and New York.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now approximately when was this? Late in 1943?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I think it was late or maybe early in 1943.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think you were assigned to the BRAZIER in May of 1943.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

It was 1944 when the BRAZIER left Galveston on the twenty-seventh of June. We finished our training in Bermuda on August second. On the nineteenth of August, we left New York for Norfolk. On the fifteenth of September, we left for Italy.

This must have been 1944. At that time, the Germans had been having a "heyday" out in the Atlantic. But they were in the habit of surfacing at five o'clock in the evening and radioing back to Berlin to get orders. The United States had just developed the high frequency radio direction finders and we were getting cross-fixes on them. The

information would be sent via NSS about the location of the German submarines and the convoys would divert around. By the time we started convoying gasoline tankers to the Mediterranean, there was really no further danger. We never heard or got close to any of the German submarines. We were able to divert around.

We went to Naples and delivered some tankers. Then we went down around the toe, through the Straits of Messina, and up into the instep to Taranto. We took the empty tankers back and never got close to anybody.

We got back to New York and received orders to go to the Pacific. Radar was installed on our ship at that time. We went down through the Panama Canal, past the Galapagos Islands, Bora Bora and Manus, and went over to Hollandia. I can't remember exactly when we were assigned to General MacArthur's fleet--the Seventh Fleet. It was a continuous source of wonder to me that we won the war with him. There was a lot of enmity between the Navy and General MacArthur. Since I had one of the most modern ships, we would go alongside a provision ship to get milk, oranges, lettuce, butter, and fresh vegetables. They'd say, "What Fleet are you attached to?" Instead of saying we were in the Second or the Third Fleet, I replied, "The Seventh Fleet." They would then say, "Oh, I'm sorry. There's been a mistake. These supplies are for the Second Fleet or the Third Fleet." We would get canned sauerkraut, canned beans, and Australian canned butter.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you ever tempted to tell them you were from a different Fleet?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

There was no way we could do that. Everybody had the numbers. But it really amazed me.

From Hollandia, we escorted merchant vessels to the next staging area. We went from Manus to Leyte Gulf. From Leyte Gulf, we went to Okinawa. At Okinawa, I could

hear on the TBF the sounds of the kamikazes trying to get through the picket line. Nobody ever got to the anchorage where we were, but we never really stayed that long. We dumped the tankers that were full, grabbed the empty ones, and brought them back.

Donald R. Lennon:

By this time, the Japanese submarines were pretty much out of the picture, were they not?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Yes. We spent a lot of time in the Philippines. From the time that we moved everything up to our new headquarters at Leyte Gulf from Hollandia, we had heard that there were midget submarines all through those channels. We visited almost every capital city in the Philippines. On one occasion, we got assigned to the invasion of northern Mindanao at a place called Macajalar Bay. We went there and bombarded. When the troops got ashore, however, they found that the Japanese had disappeared. They probably headed south. There was nothing left.

We had an interesting experience during this time at Mindanao. There was a Dole pineapple plantation up on the height of the land. We were told we could send out some men and the local engineer unit would give us a truck and some fresh pineapple for our crew. I went along to see what it was like. I had never seen a pineapple plantation before this. The pineapples were so ripe that you just twisted them off and the juice just ran out of them. They were luscious! You have never really tasted pineapple unless you've had a vine- or plant-ripened pineapple. While we were sitting in the officer's tent, we heard a big shout and we went out to see what was the story. The military unit had just received their Christmas mail. It must have been May or June. Guess what they found in their Christmas mail? A lot of people from home had sent canned pineapple!

When the war ended, we were in the harbor at Leyte Gulf, which is about twenty miles by twenty miles, so it is about four hundred square miles. Of course, we were getting ready to invade Japan. I don't believe there was an empty anchorage at all. Every anchorage was about two hundred yards. If you can imagine a mile is two thousand yards and you multiply that by four hundred square miles, knowing every anchorage of two hundred yards is filled, you can imagine how many ships there were. If you saw that, you would know the industrial might of this country. There was an engine, a diesel or gasoline motor, in every one of those vessels. I really felt that it was the industrial might of this country that overall won the war. For example, during the time when everybody in this country was rationing gas and couldn't drive a car, the Army Air Force couldn't get ice for cold beer. So to cool their beer, many times they put a couple of cases of beer in the cockpit of a Mustang. They would go up and cruise around for a while to cool the beer. They did! Did you ever know that?

Donald R. Lennon:

No, I've never heard that.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Oh boy! They really did. We were right next to an airstrip and that's how they got their beer cold.

Donald R. Lennon:

By putting it in the plane and flying around until it was cooled?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Yes, until the beer was cooled. It's amazing.

At night we were showing movies. Things were quiet in the Philippines. There were no air raids or anything. By that time, the action was all up at Okinawa. I remember a small boat--I've forgotten whether it was a small mine sweeper or PT boat--pulled up alongside us. Somebody came up on deck and said, "It's over." Immediately, every damn running light and recognition light was blinking. Every searchlight was on. People were

firing various pistols. The ship's supply officer broke out the beer--bottles and cans. Early the next morning, we had to go to Manila from Leyte. It was the worst nightmare trying to navigate through the four hundred square miles of blinking lights and not knowing who was really underway. You could hardly see the water for all the floating beer bottles.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you all been aware of the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima at that point?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I cannot remember. You know there are a lot of details that I don't remember. I would assume we probably had some inkling of that. I might have been aware of it because I would see confidential intelligence reports, but whether we were told not to say anything about that, I am not sure.

From Okinawa, we were to escort some merchant vessels up to Japan. I think this was even prior to the signing of the peace treaty. When we went in, it was foggy. We couldn't see anything. We anchored by radar. The boat's crew and I went ashore to get orders. We were told to get underway immediately and go someplace else, I guess, back to Manila. The boat's crew and I were the only people that ever saw Japan. All I did was climb up on the dock, go into the building, get my orders, get back in the boat, and go back to the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

And that was in the middle of the fog?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

That was in the middle of the fog. There was absolutely no visibility at all. If we hadn't had radar, it would have been an almost impossible task.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why hadn't they put radar on the ship at the time it was built? I thought that by that late in the war, they would have been put radar on everything.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I think it was a matter of supply and demand. All vessels that were in a combat mode, I'm sure, had it.

Donald R. Lennon:

But a DE was constructed for combat use and although it was used for convoy, they didn't know at what point they might have to be combat-ready.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Well, that's the reason why, when we came back from Taranto, they sent us into New York. They put radar on board and then sent us into the Pacific.

Back in Manila, I got a message one night, which said, "Commanding Officer, your wife in state of mental collapse at Hartford Retreat, Hartford, Connecticut. Doctor advises you come at once." It was signed by Byron "Whizzer" White. My first wife, who died, was a graduate of the University of Colorado in the same class as Byron White when he was a football player there. He was in the Navy Department, and apparently became aware of my wife's condition and sent me the message. The message came in the middle of the night and I was still tired. We were in a harbor. I kept looking at the message and said, "Gee, some poor sucker has got a horrible situation. I wonder who it is?" So I kept reading it and rereading it. All of a sudden it dawned on me, "Commanding Officer--YOUR wife--that was me!"

We were just about to leave for the States for decommissioning by that time. So we left and went to Eniwetok. At Eniwetok, my exec took over and they flew me from Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands to Pearl Harbor. I got into Pearl in the evening, had enough time for supper, and got on the mail plane. It was just two days from Pearl to Oakland. They had given me priority air. It took five days for me to get from Oakland to Long Island because I ran up against a chief who said, "I control the air priorities around here. I don't give a damn what they say in Washington. You take the plane that I tell you to take." They put me on a hospital plane that went one place, then would go down to the next hospital, and backtrack a little bit. It took five days of almost constant flying.

Donald R. Lennon:

You would have been much better off taking a commercial flight.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

That's right. It would have been.

So, at the end of the war, I had an opportunity to have a choice of two duties: either to go on to the Naval War College staff course or to go on an Antarctic expedition. However, my wife was sick in the Hartford Retreat for mental collapse. I had two children to take care of and was just unable to go anywhere. I've never regretted my decision.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you on a Reserve commission at this point or were you in the regular Navy?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I was on regular Navy until June of 1940. I think I had a three month gap from June to August or September. Then I was Reserve, which means I have no pension. I'm just a retired Reserve Commander.

Donald R. Lennon:

At that point in time, you left the Navy entirely. What have you done career-wise since returning to civilian life?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I've been in the construction business. My father operated a construction business that built commercial/institutional buildings, but not houses, unless people were millionaires. It was a relatively large construction business.

After a few years, I had a little battle with my father and left the business.

Have you ever been on the coast of Maine?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Have you ever been at sea and looked back?

Donald R. Lennon:

No.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

You drive along but you really don't see the coast. As a result, not being able to see the coast while driving was one of the reasons why these schooners thrived. People could charter a boat, sail during the day and anchor in a different harbor. There are thousands of

little harbors and places to anchor--islands and so forth--along the coast of Maine. People really get to see what it is like. For instance, you can drive on a road and see a gate which has a sign saying, "Private. No access." But if you look back from the water, you can see beautiful houses, such as the Rockefeller's Estate on Mount Desert Island and so forth. I operated one of these boats. I met my second wife, who was a passenger, and eventually married her. One day, I finally sold the vessel. Even though I really enjoyed sailing, I did come back to the construction business. I retired almost five years ago.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other reflections or particular incidents from your naval years that come to mind? Are there any anecdotes out of the DE period, such as your experience on mine sweepers, the TENNESSEE, or particular people or events?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Right offhand, I don't know of any.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had served on a battleship and on two minesweepers. What kind of observations do you have about the destroyer escort as a vessel?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I thought the BRAZIER class was an outstanding vessel. It was powerful and had great speed, but I never really had an opportunity to use it the way it was designed to work. I read books, talked to Captain Williamson and those men who really got into the fighting of the anti-submarine war. I just can't compare with that kind of thing. I do remember some things about the mine sweeper. When we were patrolling, we had two nine-hundred horse alco locomotive engines. You couldn't slow those things down enough to creep along as you had to when you were patrolling a coast and listening for submarines. If you went faster, you destroyed your ability to hear. We had to alternate--first on one screw and then on the other screw. It was on that ship, the AM97 FIERCE, when I had a bout with seasickness. I was the navigator and the communications officer. I had to locate star sights

with a bucket hanging on one arm. I sometimes had to hand the sectant to the quartermaster, lean over, and let it rip into the bucket.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was kind of humiliating.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Yes. It was. I've met my commanding officer who said, "You know, even though you were seasick as a dog and wanted to get ashore, you never failed in your duties as a navigator."

I don't know if you have ever seen pictures of an electric coding machine. It has a bunch of discs and you had to change the discs in accordance with a prearranged pattern. There is nothing worse than being down below in a ship with a diesel smell all around the room when you are sick. I would practically crawl on my hands and knees. I was just so sick that I couldn't stand up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the sea really wasn't that rough, was it?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Oh, the North Atlantic is rough out there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I thought that you indicated you were sick from the time you hit the Gulf of Mexico right on.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

I did. It was even worse in Maine than it was down in the Gulf of Mexico. From that time, I was never seasick again until I went with a friend of mine to deliver a boat from the southern coast of Massachusetts through the Cape Cod Canal. I had the second watch. We were down below and my friend lit his cabin with kerosene lamps. I got up from my watch and went outside because I was feeling sick. I laid down on the deck near the rail and felt like I just couldn't function. I could not understand. I had gone through typhoons in the Pacific, where the ocean was so rough, we had to take our mattresses out of the bunks and lay them on the floor of our room with our feet and hands spread out on top. We

did this because the mattresses would move all around since they were on springs. I'm at a loss to understand why, after riding a roller coaster in Copenhagen, I began to have stomach trouble. I suppose most people get adjusted. If you have a continuous acquaintance with a particular motion, you get over it. Your body acclimates itself to it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned the mine sweeper had locomotive engines. Were they locomotive engines that had been adapted for Navy use or were they the same engines?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

They were just alcos. They were the standard alco engine. These mine sweepers were PC hulls. These mine sweepers had to be put out fast, because the Germans had developed all sorts of mines. We had paravanes, acoustic knockers, and the electric magnetic cables. We did have an awful lot of trouble degaussing ourselves. We had to run a degaussing range every time we went in and make sure we didn't blow the hell out of ourselves. The people on mine sweepers are real seamen. When you get in the North Atlantic, you are often rigging those heavy paravanes out over the side with explosive cutters on them and so forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

As I was getting ready to say, that is probably not the kind of duty that many people would want, is it?

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

Of course, no one really had a choice. Certainly the men didn't have a choice. I liked it. I think there is a real thrill in being a competent seaman.

I was going to tell you about training my officers. When we came into Leyte Harbor, I used to get out of my cabin, go over the side in a boat, and visit the officers club. The officers in rotation would handle the ship. The first officer would take the ship to the tanker, the second one would take her to the supply ship, and the third one would take her to the anchorage and then anchor her. I really had the guys trained. I had no qualms.

We only had one accident. If you are coming in with a boat that has too much way on, your natural inclination is to back down and stop, but there is no way. You can't stop it that way. The only thing you can do is to go ahead full on that inboard engine. I tried to get that across to my officers. I would sit there in my chair, bite my lips, and let them find out for themselves. On this one occasion, the officer got frightened. He was scared to death the ship was coming in too fast, just didn't have guts enough to go ahead in full on that inboard engine, and hadn't dropped his anchor. The fluke was his anchor punched a hole in the upper level of the tanker. I went to the commanding officer of the tanker and told him what I had been trying to do. He said, "Don't make any report. I have welders here that will fix it up. It will be alright." I think that was a good lesson for everyone who was watching to see that backing down didn't slow it enough to punch it right in there.

I just finished reading a book called 73 North. It's about a British convoy that went up to the north to deliver a convoy to Murmansk. They were attacked in full force by the German Fleet, including the GHEISENOV. They only had about four or five escorts. They weren't major vessels. At a London reunion we had, the British skippers who took over the 141 old four-stack destroyers plus those who had taken over frigates and other ships that we gave them, were invited. I sat beside this skipper, who had had three escorts torpedoed from underneath him. His fourth one was torpedoed when he was coming out of Murmansk. He was torpedoed right outside the harbor, but he was able to get back in. They patched him up, but the convoy went on, leaving him to go alone. He was probably safer going alone, because the Germans wouldn't waste aircraft on just a lone escort. Can you imagine having four ships shot out from underneath you? I never knew how those guys ever lived in that kind of water.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not for long, they wouldn't.

Donald D. Snyder, Jr.:

They wouldn't. They usually had some little trawler that tagged along to pick up survivors in order to salvage their trained personnel.

[End of Interview]

My father served on the USS Brazier during WWII. I have been doing someresearch on the ship and its duties during the war. My father died in 2005 and I have his picture of the Brazier hanging in my home. He told me that while on the Brazier he traveled the equivalent of the circumfrance of the earth. The USS Brazier received one battle star but I don't know what for. Thanks for this interview. It was very interesting.