| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

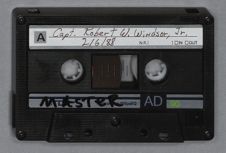

| Capt. Robert W. Windsor, Jr. | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 6, 1988 | |

| Interview # 1 |

Robert W. Windsor:

I was born in Wilmington, Delaware. We moved to Cape Charles, Virginia, but I went back to Wilmington to go to school because the educational system was better up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of business was your father in?

Robert W. Windsor:

He was a moving director for the Pennsylvania Railroad. From the time I was about eight years old, I wanted to go to the Academy; so I worked on it and my dad worked on it. Dad had grown up with Senator Townsend from Delaware. He said he could give me a West Point appointment when I got out of high school. I told him I didn't want that so he said, "Well, wait a year. I'll give you a Naval Academy appointment."

Donald R. Lennon:

What, in particular, at eight years old, caused you to decide that you wanted a Naval career?

Robert W. Windsor:

I don't know. It's really funny. It just became fixed in my mind. My mother wanted me to be a lawyer. Anyhow, I ended up going to the University of Virginia for a year on a scholarship. I was a fairly smart guy. I studied engineering and made dean's list.

I was also a good sailor. I owned my own sailboat when I was ten years old. My boat was a Cape Cod junior knockabout. I lived on the water in Virginia down at Cape Charles. I suppose it was just sort of logical to be interested in the Naval Academy to a certain

extent. When I went to the Academy, I continued to sail a lot. I joined the fencing team at the Academy, which required a lot of practice. But every weekend I did not have to practice fencing, I would sail. By the time I graduated, however, I had sort of made up my mind that I wanted to be a fighter pilot. After graduation, I served two years, first on the COLORADO and then the McLANAHAN, which was a destroyer. Then in 1943, I went to Pensacola and got my wings.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's go back and take a little more time with the period after your graduation from the Naval Academy in February 1941.

Robert W. Windsor:

We went to San Francisco to catch the HENDERSON. When you graduate from the Academy, your class standing determines your lineal rank. If you're number one in the class, you stay that way for the rest of your Naval career unless you are selected ahead of time. When they did a mass promotion like they did during the war, your lineal rank was according to how you graduated at the Naval Academy. If you graduated number one, you were the number one guy in that year group and you stayed that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

Regardless of what you were doing career-wise?

Robert W. Windsor:

That's right. It didn't make any difference until you got selected ahead of time, then you jumped over people, of course. The selection process sort of weeded out some people, but, otherwise, you stayed on that lineal list just like you got out of the Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you got on board the HENDERSON, what were you assigned?

Robert W. Windsor:

The best rooms went to the top people, then they moved right down. I think there were about two hundred and eighty of us that were going over on the HENDERSON. I stood just about a third of the way down in my class, so I was in a four-man cabin. Some of

them--the ones that were down near the bottom of the class--were in the big bunk rooms. That was interesting. That was my first real exposure to how the lineal system worked. If I had known that before I might have worked harder. I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

If they had informed you of this before.

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, we sort of got an inkling of it, but we didn't pay that much attention to it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you arrived at Pearl, you joined the COLORADO?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

From that point until December seventh, you were involved primarily in maneuvers off of Hawaii.

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes. When we first went out, the Fleet was split in half. We would go out for ten days and then we would come in for seven days. So there was a three-day overlap in which the whole Fleet was out together. About June, because of fuel and everything, they decided to switch it. We would be in ten days and out seven, so there would be an overlap of three days when everybody was in port. That's when the Japs got us at Pearl.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you on that particular morning?

Robert W. Windsor:

I was in Bremington, Washington. Our ship had gone back for an overhaul. Consequently, we were the only battleship left. We were in the drydock right next to the WARSPITE, a British battleship that had been beat up at Malta. That was how we missed it. We had gone in for a major overhaul and to get radar.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you on leave that weekend or were you onboard ship?

Robert W. Windsor:

I was over in Seattle, Washington, messing around with some girls at the University of Washington.

Donald R. Lennon:

That ended your shore leave rather precipitously, didn't it?

Robert W. Windsor:

It did. Then a couple of battleships were brought around from the East Coast. We were kept around the West Coast in the San Francisco/Long Beach area. When the battle of the Coral Sea came along, we were sent out there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I guess they kept you on the West Coast for a while because they didn't want to lose one of their last remaining battleships.

Robert W. Windsor:

We went out for the battle of Midway but we didn't see any action. Then I went to destroyers.

Donald R. Lennon:

You really were not involved in any combat on board the COLORADO?

Robert W. Windsor:

Not that you could say was real combat. We didn't see any Jap planes. We didn't see any Jap ships. Of course, the only surface ships involved in Midway and Coral Sea were carriers with their screens. None of the battleships were involved.

Then I went to destroyers. That was very interesting. I had my orders to flight training by this time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you actually serve in a destroyer?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Which one?

Robert W. Windsor:

The McLANAHAN, DD 615. She was built in San Pedro, California. She went around to the East Coast and we were involved in the battle of the Atlantic. I left the ship right before the invasion of Sicily.

Donald R. Lennon:

You might want to comment a little bit on just what kind of activities you did see onboard the McLANAHAN. What specifically were you involved in there?

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, the big thing was the invasion of North Africa.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are there any details on that?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. It was just routine. We did shore bombardment. It wasn't really until after I had left the ship that it went into the Mediterranean. We stayed off the coast of Africa and covered the first landings of the American troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it was shore bombardment that you were involved in rather than any German counter-offense? Wasn't the German fleet there on the North African Coast?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. It was mostly French.

Donald R. Lennon:

Weren't the French ships controlled by the Germans?

Robert W. Windsor:

Right, with the Vichy government. There were submarines there, though not as many as we thought there would be. But we did have contacts and made depth-charge runs on a couple of them. As far as I know, we never got anything. The weather in the North Atlantic was miserable.

Donald R. Lennon:

I can imagine. I've heard quite a few comments on the convoy duty in 1941 in the North Atlantic.

Robert W. Windsor:

It was rolling. One night we were escorting the YORKTOWN when she was brand new and we rolled about 47 degrees to a vertical--threw me right out of my bunk. I hit the fiddley(?), you know, what we kept the blankets in. I was a gunnery officer and I had a box of forty-five calibre ammunition stuck underneath the safe. It had rolled out and gone onto the deck. I had just come off of the eight-to-twelve watch. We only had two qualified watch-standers because the ship was so new. I would stand the eight-to-twelve one night and the four-to-eight the next night. The other guy was qualified to stand midwatch. The next night we would switch off, and I would have the midwatch. During the day the skipper and the exec would be up there while we were trying to qualify these other people. I stayed

kind of busy, particularly for being the gunnery officer, because I was the senior watch officer, also.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your ammunition had rolled out from under your bunk?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes, and I rolled right on top of it when the ship rolled. I had about twenty-five little black and blue marks all over where I had landed on it. Then when I tried to get up, the ship was rolling back and forth, and I was slipping and sliding. No wonder I went to flight training!

The skipper of the McLANAHAN was out of the Class of 1927, the exec was out of the Class of 1933, and I was out of the Class of 1941. The other twelve officers were all jo's with no real experience. One Naval Academy graduate who came aboard was out of the Class of 1943.

Donald R. Lennon:

The rest were Reserve?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes. "Ninety-day wonders."

Donald R. Lennon:

How did they work out?

Robert W. Windsor:

They worked out fine. They were good officers, very dedicated, and fast learners. They had to be.

After North Africa, I came back to the States and was detached.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't detached until you returned to the States from North Africa, and from there you went directly to Dallas to primary flight training. Were there any particular memories of the flight training itself?

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, it was fun. Dallas was a wonderful city and they were very kind to us. A classmate of mine, Bill Elliott, was there and he and I roomed together. We had an

apartment in Dallas. We went all the way through flight training together. When we went to Pensacola for basic and advanced, we were in the same flight class. There would be seven in a flight class with an instructor. Then we went to operational training together after we got our wings.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this in 1943 that you were in training?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes. From the time we came in until the time we went out, with a set of wings on, was five and a half months. It takes eighteen months now. But they needed pilots bad and they wanted to get the Academy graduates out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Get them back to the combat zone. What was your assignment once you left Pensacola?

Robert W. Windsor:

I went to operational training in Wildcats at Sanford(?). Then we went up to the Great Lakes and qualified on the WOLVERINE, an old Great Lakes steamer that they had put a flight deck on.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes. I heard about the WOLVERINE. There were two of them up there weren't there?

Robert W. Windsor:

The SABLE was there later, but when we went up there, there was just the WOLVERINE. We were up there in January. It was cold. There were ice floes. It made you make good landings because you didn't want to go into that cold water. After that, we stayed at Sanford(?) for a little while as assistant instructors to build up our flight time, because when we left, we went as squadron executive officers. We were pretty senior so they tried to get us some flight time. We flew a lot of flights--a lot of gunnery flights. Then in 1944, I went out to the Fleet in San Diego and was assigned to a composite squadron composed of sixteen fighters and twelve torpedo planes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you sent from San Diego?

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, we went from San Diego to Seattle and down to North Bend, Oregon. Then we came back to the San Diego area.

Donald R. Lennon:

You stayed based on the Northwest Coast? They didn't send you back out to the South Pacific?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. They worked up a squadron that had just come back. So we had some of the old guys--some of the guys who had combat experience in the air--then they fed in new people. I happened to be fed in as the executive officer. Our commanding officer was a guy out of the Class of 1937, who earned a Navy Cross and was famous in his own right, "Spike" Ewoldt. They were an interesting group of guys. We had a couple of aces in the fighter part. They came off the FANSHAW BAY and we went back on the TULAGI, which was one of the jeep carriers. The FANSHAW BAY was being repaired because she was in that battle down there in the Lingayen Gulf. She got beat up pretty bad. They sank the WHITE PLAINS and the SAINT LO. Since the FANSHAW BAY was being reworked, we went out on the TULAGI. Then we went over to the SHAMROCK BAY for awhile and we finally ended up on the FANSHAW BAY after she got back out again. It got kind of dull out there for the jeep carriers because we didn't see very much.

We did go to Iwo Jima, but there wasn't a lot of air action. We were carrying a couple of 250-pound bombs under the fighter wings. We were working up for "Olympia," which was going to be the invasion of Japan. That would have been interesting, but of course they dropped the atom bomb and that ended the plans for the invasion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had the use of Naval planes diminished by this time in the war?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. The big carriers were really doing a lot. We did, like at Iwo, a lot of ground support but very little air action. The Japs were pretty well wiped out by this time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Their capabilities in anti-aircraft were probably quite diminished by this time, weren't they?

Robert W. Windsor:

Oh yes, sure. I think we lost two pilots. That's about all we lost. So that wasn't great. Then the war ended and we came back to San Diego. We came through Pearl and stayed there about a month. We were still flying some but we were getting ready to turn in our airplanes. When we got ready to come back, we left all those pretty new airplanes, they were only about six months old. I understand, they pulled the engines and "deep-sixed" them.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to say, they probably scrapped them. What a waste!

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes, if they had had a place to stack them, but the carriers were loaded with all the people coming back from overseas. They wanted to use the carriers as "Magic Carpets." We loaded up probably three more squadrons in Pearl. We didn't even come back on our own ship because she went on back out to pick up more people.

Donald R. Lennon:

The most important thing was getting the manpower back stateside as fast as possible?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes, for discharge. We went in and some of the guys stayed regular Navy, but I would say that 70 percent of them got out right away because they had the points already. Then I was assigned to an admiral's staff. It was really interesting because it was with Marc Mitscher who had been CDF-77. So I went to Mitscher's staff, and Admiral Burke, who was then a commodore, was the chief of staff, and DonGriffin, who later became a four-star, was a captain and the operations officer. There were a lot of very interesting people on

that staff.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the admiral headquartered then?

Robert W. Windsor:

We went back to Norfolk. The admiral believed in cross training so I was sent up to a submarine school for about two weeks. Then I went down to C.I. C. school down in Glenco(?).

Donald R. Lennon:

This was the 1945-6 period?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

What rank were you by this time?

Robert W. Windsor:

I had just made lieutenant commander in August. That wasn't too bad. I made lieutenant commander in four and a half years.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is amazing. You had experience in surface ships, aviation, and then had training in submarines?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes, just for ten days. It was a special course for the "fly boys."

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't the type of submarine training that would have made you qualify for duty?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. We went out for a four-day period at sea and then went through the simulators.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was for familiarization.

Robert W. Windsor:

It was sort of the same thing at C.I.C. school although I was down there for two months. During that tour, I was Mitscher's aide for a little while and that was interesting. That's the reason I have those pictures of Admiral Burke in there when he was CNO.

Donald R. Lennon:

What exactly was the Navy command involved in at that time? You were right at the end of four years of all-out war and trying to move back into a peacetime setting. All the armed forces, not just the Navy, were having an excess of ships, planes, and all type of armaments to dispose of.

Robert W. Windsor:

They were decommissioning ships and putting some of them in mothballs and some of them they just scrapped right away.

Donald R. Lennon:

Basically, what was the admiral and his staff involved in at this time?

Robert W. Windsor:

We were pulling together what was going to be the Atlantic Fleet. Basically, it was called the Eighth Task Fleet. We had all the carriers that were on the East Coast. There were probably nine at that time, maybe more. We had a couple of new ships. We had the F.D.R. and the MIDWAY. The CORAL SEA went on around. They were the three big ones and they didn't see any action. Our flagship was the F.D.R. because Marc Mitscher was a big carrier force commander during the war and that's where he wanted to be. Arleigh Burke was a wonderful guy.

Donald R. Lennon:

With your headquarters in Norfolk, was there much sea duty involved?

Robert W. Windsor:

We went to sea quite a bit. We did a lot of exercises. We'd go down to the Caribbean. We did the first North Atlantic exercise up off Norway in 1946. All this time I was agitating to get back in a fighter squadron. I got married about that time and got orders to go back and command a fighter squadron.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was this to be stationed?

Robert W. Windsor:

I was up in Charlestown, Rhode Island. Air Group Three. It was a good air group. It had a lot of combat-experienced people. We made a couple of Mediterranean cruises and a couple of NATO cruises. Radford had relieved Marc Mitscher who became the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet. It was really good. I was still a lieutenant commander, but I'd get called up to the bridge to talk to the vice admiral mainly because I had been on his staff. He'd get me up there to ask me questions about what was going on and and how different it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

What ship was your squadron assigned to?

Robert W. Windsor:

The KEARSARGE.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there anything going on in the Mediterranean in 1947-48?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. There were a few little Cyprus things that would come up and we would have to steam down there. There were some problems down in the Dominican Republic and we had to go down there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of "show of force."

Robert W. Windsor:

Kind of "show of force." We did have orders to shoot back if we were fired upon, which was a lot different than it was up until Reagan came into office. I'll tell you: We were the big boys in those days! I had two years as commanding officer of "Fighting 32." Then I went down to Jacksonville to form a staff down there--ComFAirJax. This was when they turned Jacksonville into a Fleet base and moved the air groups down. My old air group moved down there. That was an interesting period of time. It was right before the Korean War broke out. Louis Johnson was the Secretary of Defense and he was de-commissioning air groups right and left. As a matter of fact, he de-commissioned Air Group Four the first of June. The air group came back from the Mediterranean on the first of June and they were given orders; they were to turn in their airplanes, and go on leave, and then were to be scattered to the four winds. About that time the North Koreans invaded, so we had to cancel everybody's orders and order then back in again.

Just about that time, I was ordered to go up to test pilot school. So I went up and did two years at the test center. I got a chance to really get deep into the jet business. As a matter of fact, I was the fourth Navy pilot to reach a thousand jet hours. We were really flying a lot. There is a funny story about how I ended up being fourth instead of third.

Wally Schirra, the astronaut, was in my fighter squadron. I was his squadron exec, VC-3. We had a big fighter squadron. We furnished all the night fighters. We also did the jet transitional training for pilots that were going to go into jet squadrons and were getting new jets. So anyhow, Wally was in the squadron and he was flying F7Us and I was flying FJs. Wally had 999 point something hours and I had 999 point something hours on the same day. So being the squadron exec, I ordered Schirra to be put on the later schedule the next day. It was a rainy miserable day. I jumped in the airplane bright and early in the morning and went off and flew around a couple of hours so I could get the time. Then I came back on in. They guy who was the number one guy in the Navy as far as jet time was concerned was Bud Sickel. Well, when I landed, there were Bud and Wally holding this great big sign up that said: One Thousand Jet Hours. Schirra had bummed an airplane the night before from another squadron and beat me out. We had a couple of laughs in those days, I'll tell you. I ended up being the fourth Navy pilot with a thousand jet hours. He ended up being three. We were all laughing like hell.

Donald R. Lennon:

Didn't you set a speed record?

Robert W. Windsor:

That was when I went back to Patuxent for a second tour of duty. When I left Patuxent, I went out and I took command of the first swept wing Navy jet squadron. It was rather interesting because I had five test pilot school graduates and every division and every section leader was a combat-experienced pilot. The "nuggets" that we got in were top guys, too. We really had an experienced squadron.

We went to Korea, but it was the tail end of the Korean War and we didn't see many airborne [enemy]. The only guys that we saw were air force 86s. By that time, when they'd come across the island, they'd turn right around as soon we'd make a pass in their direction.

That was a sanctuary. We were not allowed to go across the Yalu River. Even if the guy was a thousand yards away when he hightailed it, we couldn't chase him or shoot him down.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was pretty frustrating, wasn't it?

Robert W. Windsor:

It was very frustrating. It really was. We didn't have bomb racks or anything. All we had was our poor twenty-millimeter cannon.

Donald R. Lennon:

What ship were you operating off of?

Robert W. Windsor:

The YORKTOWN. That's the picture of us on the YORKTOWN. You can see the big "10" on the bow.

Then I came back and I went to VC-3. We had over two hundred pilots in VC-3. It was big. It had a hundred airplanes. We furnished all the night fighter guys to the air groups, and we started the jet transitional unit. We had a lot of different new jets. I would go to the test center and fly them a little bit. Then we would get six of them and train a few key people out of every squadron to fly them.

Then I got my orders back to flight test again. I spent another two and a half years flying airplanes there and that's when I took the speed record.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us about that.

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, there are lots of write-ups on it some place in all my stuff. I could get them for you.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would like for you to tell about it from a personal point of view rather than from the actual write-ups.

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, I guess I'm going to have to start at the beginning when I went back to Patuxent and was the head of the carrier branch. We did all the stability control performance on all

the new jets. I'd been back about two months when we went out to Edwards to test the newest one which was the F-8 Crusader. I was a team leader on it. I had a Marine and another Navy pilot. We did all the original flying on the F-8 Crusader. We started to get it ready to go aboard the carrier so being the boss, I made myself the project pilot for it. I did the first catapult shot and the first arrested landing in the Crusader. The Crusader was the first truly supersonic airplane that we had. When it was decided that the Navy was going to set a new speed record in the airplane, I was nominated and assigned the job. I went out to the desert and we did about eight or nine warm-up flights. We cooled the fuel through dry ice so you get more fuel in the airplane. The name of the project was Project One Grand because we wanted to hit one thousand miles an hour and be the first ones to do it. We did, without any strain. We could have gone faster if they had allowed us to. The Secretary of Defense was Wilson at that time and he said, "I don't want you to go over a thousand miles an hour."

Donald R. Lennon:

Why? What was his rationale?

Robert W. Windsor:

He didn't want the Russians to know what a superb airplane it was. I had it up over eleven hundred miles an hour. That airplane could really move out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why did they do it over the desert rather than over the ocean?

Robert W. Windsor:

First of all, it was supersonic and it laid a boom down that wouldn't be believed. We would go right over China Lake, our ordnance test center out there. I've got a very interesting article that came out of "The Tester," I guess it's called. It said, "When you hear that loud boom, it's just the Duke going out for practice." That was the headline for that newspaper.

Donald R. Lennon:

Inside the cockpit, do you hear that boom at all?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. It's behind you. It's coming off the wings and tail section. That's why you hear two booms. You get the boom off the leading edge of the wing; and you get the smaller boom off the leading edge of the tail. That's how you got the double boom.

Donald R. Lennon:

You started out, during World War II, in the old prop planes.

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes. I was in the Wildcats and then got into the F-6s. Then I flew the VF-32s, which were Bearcats and was with the F-8 Bearcat Squadron. My next squadron was in a Cougar, the F9F-6 Swept Wing Squadron. Then I got into the really high-performance airplanes, the F-11s and the F-3Hs.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were able to see all the technological developments, from the props to the first jets to the more high-performance perfected versions.

Robert W. Windsor:

From where we were wearing the cloth helmets and scarves!

Donald R. Lennon:

How about commenting on the transition in technology and how you as a pilot reacted and adjusted to those changes.

Robert W. Windsor:

The Bearcat was the finest prop fighter ever built. I got the greatest thrill flying the Bearcat. It was the finest airplane to fly. Then I flew a lot of different jets. I've flown 106 different types of airplanes, probably as many as anybody in the Naval Air Force.

Donald R. Lennon:

What marked the transition from the prop to the jet?

Robert W. Windsor:

The early jets, like the Phantom One, didn't have pressurized cockpits. It wasn't any faster really than the Bearcat, but it had greater altitude performance by a long shot. The fuel system in the original jets was really complicated. Fuel management was a big thing that you really had to worry about. Then, as we went on and became more sophisticated, we

didn't have to worry about that anymore. It was done automatically by sequential operation of the fuel tanks into a big sump tank. We didn't have to keep watching them and switching tanks.

The original jets were a little bit complicated but we didn't have them too long. Some people went from props to jets and never went through the original jets, because we only had two squadrons of FHs, ever. The F9F-2 wasn't quite as complicated. It came along and it was the one we were using in the early part of the Korean conflict. Then we went to the F9F-4s and -5s, which were straight wings. They had bigger engines and were faster and more sophisticated. When we went to the F9F-2s, we went to pressurization. The FH-1 didn't have a pressurized cockpit, but the F9F-2s did, albeit they did have their problems with pressurization. When we got to the F-5s and F-6s, it was much better. The F-6s had flying tails, where the whole tail surface moved. Every time we'd get into a new jet, there would be a lot of new things in them like the fire-control systems and radar. The radar got bigger. The first F8U-1 Crusader had a very small radar. By the time we got to the F8U-2, the radar was bigger and the nose was changed a little bit. Then all of a sudden we started getting electronic warfare stuff and tail-warning radar. The last jet that I flew a lot (five- and six-hundred hours,) was the Phantom, the F-4(?). By that time we had a rear-seat guy sitting back there with the radar interceptoscer(?). He could do an awful lot for you. He was another set of eyes and he also had his head stuck in the scope. When we went from props to jets, the changes went very, very fast.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I was thinking. I was wondering how easy it was to adapt to such rapid changes.

Robert W. Windsor:

For me, it was pretty easy because I had worked into it. I started flying jets right from

the very beginning and also I had a lot of prop fighter time.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't see any drastic changes.

Robert W. Windsor:

The jets were easier to fly in many ways. We didn't have to worry about torque, and they had tricycle gear. It was like driving a Cadillac instead of a Model-T. That's really what jets were like.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you got to the speeds that are involved with the supersonic jets--eight- or nine-hundred miles an hour or more--was there any difference in your reaction time that you had to be alert to?

Robert W. Windsor:

I had to be more anticipatory. Things happen a little faster. It's surprising how much time you really do have. I had a flameout in a Cougar off of San Diego and went into the drink. I was below the ejection level so I had to go into the drink right off the Del Coronado Hotel. I broke my back and spent three months in the hospital in a body cast. It was right after I got back from Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have to eject?

Robert W. Windsor:

I couldn't. I was too low. That's called being outside the envelope. I was outside the ejection envelope so I ditched it and broke my back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they have to rescue you from inside the plane?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. I was able to get out. I just stood on the wing of the airplane and it sank out from under me. That's really the reason I ended up getting out of the Navy. I spent three months in the hospital in a body cast, but they didn't realize at the time that I had injured my left kidney and my pancreas. It came back to haunt me fourteen years later. While I was in the hospital and going to be retired physically, I was selected for admiral. They retired me

with an admiral's pay but without the rank. I had filled in all their so-called slots you know. I had commanded all those squadrons; I had gone to the National War College, which is a career war college; I had command of my own ship and of the big carrier; and then I became chief of staff of the Second Fleet. That's where I was when I ended up in the hospital and retired.

Donald R. Lennon:

You received the Thompson Trophy.

Robert W. Windsor:

That was for speed.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would you like to comment on your duty in the SARATOGA in the Mediterranean during the Lebanon crisis?

Robert W. Windsor:

It was really interesting. Being the OPs officer, I used to get to fly the TF every now and then, so I went in and landed in Lebanon a couple of times just to see what the Marines were doing. When we got word on the crisis, we were in Cannes. The ESSEX, I think, was the other carrier down in that neighborhood. When they recalled us, we had to look all over town for our crew, because they were on leave and observing the Fourth of July and Bastille Day period. We were supposed to be in there through the whole thing, but they pulled us out when the crisis started.

Donald R. Lennon:

The crisis erupted that quickly?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yes. George Anderson was the CarTF(?) commander and later became the C. and O. I remember going into the lobby of the Martinez Hotel, where six of us commanders had a suite while we were ashore. It was a place to change clothes and everything. When I got there, everybody was running wildly around. During the crisis, I got a chance to fly Admiral Anderson (he liked to fly with me) over to Rhodes and places like that for meetings

with "Cat" Brown of the Sixth Fleet. Everything was pretty well calmed down when I got orders to London to be with Admiral Haughey(?). He was the head of the major force.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course the SARATOGA pulled out of Cannes and headed for the eastern Mediterranean. What was your function in the crisis?

Robert W. Windsor:

We started launching airplanes to give them air cover. They didn't really need it, however, because the ESSEX was closer and got there about eight hours before we did. We steamed down there at about twenty-eight knots. We were really making knots.

Donald R. Lennon:

You just stood off the coast.

Robert W. Windsor:

We were very close into the coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no action involved other than you flew in just to see what was going on. Did you just fly over or did you land?

Robert W. Windsor:

I landed. I went right in and landed at the airfield. I took some mail in to the Marines, stuff like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

The other thing we haven't talked about is your duty in the INDEPENDENCE. That's very important. I would like for you to take some time with that.

Robert W. Windsor:

It was a wonderful period of time. I really enjoyed it. I found out that I liked ship-handling. Everything is in such slow motion in comparison to flying airplanes. I guess I'm patting my own back, but everyone thought I was a wonderful ship-handler. The commanding officer of the SARATOGA, when I was OPs officer, gave me a chance to put the ship alongside to oil and refuel and everything. I would always make high-speed approaches to the replenishment ships. Everybody thought that was great. I would pull up there and back down two thirds and slap it alongside. In Vietnam we were doing it three or four times a week.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you take command of the INDEPENDENCE?

Robert W. Windsor:

I took command of her in 1964.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was she already in Vietnam?

Robert W. Windsor:

No. I took command of her and we went up for NATO maneuvers. Then we went into the Mediterranean and came back. We were supposed to go back to the Med. I had the very first all-jet air wing embarkment for the ship--the new AGs, the Intruders--they decided they wanted to have them out in Vietnam. We went up through the Indian Ocean. We went at twenty knots all the way.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you go up through the Canal or around South America?

Robert W. Windsor:

No, we went around the other way, around Capetown and up through the Indian Ocean. Then we went down through the Straits of Malacca. It was very successful because we had an experienced air group. They froze everybody in the air group, so we had all those experienced pilots in there. Like I said, we had just come back from a Mediterranean deployment, so we got a lot of commendations because of our boarding rate.

Donald R. Lennon:

[Where did the INDEPENDENCE patrol?

Robert W. Windsor:

Yankee Station. I don't know whether anybody has talked to you about Yankee Station or not. Yankee Station was a big spot in the ocean just a little bit north of Da Nang. As a matter of fact, some nights you could see fire fights in Da Nang from the ship. That's how close in we were. At Yankee Station, we would operate within a radius of maybe fifty miles or so north or south.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of raids did your planes fly in?

Robert W. Windsor:

We did everything. We did "road reccies"(?) (reconnaissance). We did some work up around Thailand and Cambodia. We ran the first raids into Cambodia when they weren't

talking about them. They said if we ever knocked the Tamois(?) Bridge down, the earth was going to split in two, that the two spirits--apertures--were held together by the Tamois(?) Bridge. We finally knocked the bridge down after we lost Jerry Denton(?). It was busy, real busy.

Donald R. Lennon:

As CO, you didn't have the privilege of flying at all while you were there did you?

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, I tell you, I was the one commanding officer that had a waiver to fly, mainly because I had quite a bit of experience. Paul Ramsey, Commander Naval Air Force Flying Fleet, gave me permission to fly until he found out I had flown a couple of "recce"(?) flights in an F-4. I got a message that I was being paid to command the ship and not to fly and have fun. He worried about my getting back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you see combat?

Robert W. Windsor:

It wasn't real combat. I've got a great big beautiful picture of me being launched off a wastecat(?) off my own ship. The guys painted up an airplane for me. "Tag"(?) always had a double zero on the nose of his airplane so they put a triple zero on an F-4, with my name on the cockpit. That was my airplane. I got to fly it pretty often. I usually didn't fly off of my own ship. I did a couple times, but I flew with an air group all the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you suffer many losses?

Robert W. Windsor:

Well, we lost one HVJ(?) which is a photo-reconnaissance airplane. We lost a couple of A-6s and several A-4s were hit while I was there. The F-4s didn't have any problems, however.

Then they brought me back. I went to be chief of staff of the Second Fleet. I almost got ordered out to take command of the INDEPENDENCE again, because they brought

"Blackie" Kennedy, the man who relieved me, back to the States when his wife and one of his daughters were seriously injured in an automobile accident. They prepped me to go back out again but then they changed their minds.

Donald R. Lennon:

You probably would have preferred to have been out there, wouldn't you?

Robert W. Windsor:

Sure, I would have enjoyed it! Hell, they were going to go to Hong Kong. But I stayed and I enjoyed the Second Fleet. That was fun. Then I had to get out. I was relieved right out of that job.

Donald R. Lennon:

Due to your injury in the plane crash?

Robert W. Windsor:

I have an odd ball retirement date because when you get retired physically, they can do it any day in the week. But when you get retired just because you are being retired, it's always on the last day of the month. My date of retirement is the twenty-seventh day of April. I remember it well.

[End of Interview]

Is there an actual voice recording of Capt. Windsor available to the public. I would be very interested in obtaining a copy if there is. Please advise. I can be reached by email (above), phone (530) 400-5056, or surface mail: Gene Crumley, 5735 SW Arbor Drive, South Beach, OR 97366. I will happily defray any and all costs associated with getting access to a voice recording of this interview. Thank you.