| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #93 | |

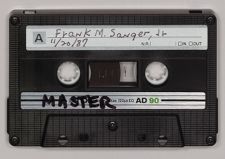

| Frank M. Sanger, Jr. | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| November 20, 1987 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon |

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I was born in Norwalk, Connecticut, about forty miles outside of New York. We were a family of three children, I was the oldest. My sister is a year and a half younger. And then my “little brother”, who stands six feet seven and something, is twelve years younger than I. We lived in Norwalk, or that is the first four of the family lived in Norwalk, until I was just about twelve years old. Dick, the younger brother was born just before we moved to Watertown, New York. Dad was in the paper machine business with a company in Greenwich, Connecticut, and went with a company in Watertown. I went to high school in Watertown and graduated in the winter of 1934-35. I graduated in January of 1935 and stayed on to do some additional work. We were, of course, in the middle of the Depression at the time and while my Dad had a reasonably good job as chief engineer of this paper machine company, sending me off to college was still kind of a rough thing to contemplate. So I, very early, got the idea of one of the service academies as something I could do to help the family along.

I was offered an appointment to West Point. The congressman who had our district, for reasons of his own, offered his Naval Academy appointments to people from

his hometown of Oswego, New York. Having, at that time, no real opportunity for a Naval Academy appointment, I took the West Point appointment and went down to New York and proceeded to fail the physical examination. I don't know if my high blood pressure was from living in the big city for a week on my own or what. But anyways, I bombed out as far as West Point was concerned.

The following year, in the fall of 1936, I went to Duke where I spent my freshman year in the engineering school. While there, I took a competitive exam for a Naval Academy appointment for the following year. It was from the same congressman, and I won the appointment and entered the Naval Academy in June of 1937. I was one of the first of the entering plebes that year.

Plebe year was sort of a basket of fruit because I had taken most of the subjects that we had, and at the end of plebe year I stood one in the class, somewhat to my surprise. But as I said, it was pretty easy because I had had just about all the work before.

Donald R. Lennon:

What had led you to go to Duke that year? You were saying that during the Depression your father couldn't really send you to college and right now I can't think of many places in the South that are more expensive than Duke.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

True. But it was still significantly less expensive than most of the schools in the northeast, and the family resources had improved somewhat. Also, I had a mother who a native Virginian and was quite interested in having her son grow up with a little bit of Southern exposure. I guess she didn't realize that Duke had more Yankees in it than most of the schools in that part of the country.

Donald R. Lennon:

It still does.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Going back to Duke for a moment, something comes to mind. I joined a fraternity there, Phi Kappa Psi. But at that time the engineering students were all housed

over in Southgate Hall on the women's campus, the East Campus, so I never did live in the fraternity house. In fact, at that time, Duke didn't have fraternity houses as such. They had little sections of the dormitories that were set aside.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think my mother-in-law was probably at Duke about the same time on the women's campus.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Is that so? Well, getting back to the Naval Academy, my plebe year I went out for crew. My dad had rowed for Cornell. As I recall, I wound up being stroke of one of the boats other than the number one boat in the plebe crew. I was a poor enough oarsman that I didn't follow through in my upper class years. I played casual sports. I didn't go out for any of the team sports other than the plebe crew. I played a fair amount of tennis but was not good enough to go out for the team. I played a fair amount of bridge and made some good friends at the Academy playing bridge. Eddie Miller was among them. Some of the more fond recollections at the Academy were the ketch cruises during my second class summer. Has anybody told you about them?

Donald R. Lennon:

There have been some references to them.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

The Academy had some fifty-foot motor launches that they had converted into sailboats with ketch rigs. They were about the poorest sailing boats that ever came down the pike, but they had adequate engine power. If you had behaved yourself, not gotten into too much trouble with the authorities and not accumulated too many demerits, and qualified for the ketch command, you could sign up for one of these ketches. Then with a half a dozen or so midshipmen as crew you could take it on a weekend trip, say overnight from the Academy, perhaps across the bay. This was a good way of getting away from the Academy and the discipline, and getting to see some of the nearby places. Cambridge, on the Eastern shore, was a favorite.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sometimes they used them to slip up to the women's college up there.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. Also, one of the first stops was usually around on the South River where you could pick up a case of beer. Well, this was a good way of augmenting the two weekend leaves that we were authorized for the whole second class summer. Maybe there were more than that, but there weren't very many. By the time I had been in the Academy a little over a year, my family moved to Wilmington, Delaware, so I was considerably closer to home. Getting home when we did have a weekend was fairly easy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you think of the situation at the Academy at that time?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

For me it was close to ideal as far as the method of instruction. I guess I always pick things up better out of a book than I do listening and taking notes. We called our instructors referees rather than instructors because their main job was to quiz us on what we had read as homework assignments. They did very little instructing in the class.

Donald R. Lennon:

They did very little lecturing.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That's right. In my situation, they did a better job than anywhere else I have been of teaching me where to go for the information I needed rather than trying to drill that information into my head. So I was quite happy with the Academy system and frankly over the years have been a little sorry to see it become more along the lines of a classic university. I'm sure there are those that don't agree with me, plenty of them.

I mentioned I had done real well my first class year. I don't remember whether I stood one any other years. My Youngster Year, I may have, but by my first class year I had definitely surrendered that number one position. I did, however, wind up for the four years in the number two spot. I think that was largely luck.

When the time came to make our choices or to state our preferences for sea duty, I opted for either a battleship or a cruiser. I thought I'd probably learn more in a big ship

for my first tour, then, in the following tours, get into smaller ships where I could have more responsibility.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before leaving the Academy, are there any particular incidents, either positive or negative, that you recall that would be worth sharing, particularly anecdotes or stories concerning your four years there that would be good for the record?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

One that comes to mind concerns one of our company officers. The company officers, as you probably have been told, took Officer-of-the-Watch duty assignments. They would have the watch for a twenty-four-hour period and would tour the corridors of Bancroft Hall, keeping an open eye for infractions. The Duty Officer always had a midshipman walking along right behind him with a pad to jot down names and serial numbers of the midshipmen that the D.O. caught breaking the regulations. One of them who had a reputation for being a very alert duty officer but generally a fair one was Ray Hunter, then a lieutenant. Ray had on various occasions given minor reprimands and, in a couple of cases, reported offenses by several of us, myself included. It was our first class year on the morning that Christmas leave was to start, and two or three of us had figured out how we were going to get away as fast as possible. I guess we had to take the train into Baltimore and we wanted to make sure that we caught it. So, against regulations, we came down to the mess hall in civilian clothes. We figured we could get away with it but who walked in but Lieutenant Hunter. There were all sorts of scowls. “What's going on here?” he said in a very strict tone of voice. After he had given us about five minutes worth of scare, telling us our Christmas leave was going to be cut short, he said, “Well you guys have a good time.” He didn't put us on report.

Another one that comes to mind was Gerald Wright. I guess he wound up as a vice admiral or maybe he made four stars, I'm not sure. But Gerald Wright was a

commander at the time and a battalion officer. He had one of the other battalions, not the one that I was in. But Gerald Wright was a very observant person. One day I was called down to the main office, at the entrance to Bancroft Hall to pick up something, and I grabbed a whiteworks jacket, a slip-over jacket, to be in proper uniform. But I just happened to grab my roommate's jacket. So I was walking down the hall with “Brewster Phillips” or “B. Phillips” instead of “F. Sanger” across my chest when Gerald Wright came down the hall followed by a midshipman with his notepad. I saluted him as I approached him and kept walking. He said, “Minster, hold it.” I stopped and he said, “That's not your name is it?” Now how he knew me out of probably...

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you even conscious that you had the wrong jacket?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I think I was by then.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did he do? Did he put you on report?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No, which surprised me. Of course, there were all sorts of memorable hops and drags and good fun of that sort, and, of course, the midshipman cruises. On my first one, our youngster cruise, I was on the TEXAS. There were, as I recall, the old TEXAS, the NEW YORK, and one of the other old battlewagons. We went to Le Havre. I remember the tide there. It had something like a twenty-foot range of tide. At one time of the day you would look up at the dock you were tied to and six hours later you would be looking down. It was quite unusual. From Le Havre we midshipmen went into Paris for a quick trip. Then we steamed up to Denmark and stopped at Copenhagen. I remember the Tivoli Gardens, the amusement park there in Copenhagen. I was impressed by the fact that in a foreign country of that sort it was practically impossible to find anybody that didn't speak English.

Donald R. Lennon:

You know now days you accept that, but in the late thirties, 1937, 1938, it was quite amazing!

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Our second class cruises was in destroyers along the East Coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was due to the war in Europe. It was dangerous to go very far.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Right. I remember stopping at New York. The World's Fair was going on at that time.

September leave was always a big occasion and so was Christmas leave, what there was of it. As I mentioned, with the family having moved to Wilmington it was a more accessible home base.

Donald R. Lennon:

Upon graduation, you had requested a big ship?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes and I was assigned to the WASHINGTON, which was to be commissioned later that spring. From the Academy, four of us who were going to be in the fire-control divisions on the WASHINGTON and the NORTH CAROLINA were sent to Ford Instrument Company on Long Island, New York, for schooling in the fire-control equipment. So Ed Miller, Howard Montgomery, Paul Wirth, and myself found ourselves an apartment on the East Side and commuted every day over to Brooklyn to the Ford Instrument Company. I guess we were there for five or six weeks. Then in March we went to Philadelphia.

Donald R. Lennon:

Spending five or six weeks in Manhattan wasn't bad?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No, it wasn't bad. Although they pay in those days was...well I guess it wasn't any worse relatively than it is today. It was a little better than the old saying: “Forty-one dollars a day, once a month.” But not much.With the WASHINGTON being finished in Philadelphia, which was right next door practically to Wilmington where my family was, I got home quite a bit in that month

or so that we were there. As I recall, it was sometime in May that we were commissioned. My recollection of dates is not that good, but we were shortly behind the NORTH CAROLINA as far as a commissioning date was concerned. We spent the rest of that spring on shakedown trials of one kind or another.

Donald R. Lennon:

The NORTH CAROLINA got all the publicity didn't it?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yep, the “Showboat”. We got down to Guantanamo during the course of the shakedown trials, but we pretty much went up and down the East Coast during that summer. Here my recollection of dates is letting me down. You probably have it from Eddie Miller, I know Ed's much better in remembering when various things happened. He's reminded me of a great many. We went to Scapa Flow and joined the British home fleet.

Donald R. Lennon:

He didn't put a date on that at all.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

He did not? I'm pretty sure it was in the late summer or early fall of 1941. (Note: It was early in '42)

Donald R. Lennon:

I think the WASHINGTON was up there late that summer.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I remember the King of England coming aboard and paying an official visit to America's newest battleship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that during one of the convoys?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

His visit?

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

His visit was at Scapa Flow and I frankly don't remember whether it was before or after. I think you are right, probably between convoys. We played a somewhat odd role. They had us along on those convoys primarily to cover the situation if the Germans

sent out the TIRPITZ, which was their big ship. She was a battleship with about the same firepower and the same characteristics of our WASHINGTON.

Donald R. Lennon:

She was a sister ship of the BISMARCK wasn't she?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Right. I think once, they did start her out from the fjord where they had her in hiding, but something scared them back. Most of the time we never saw the convoys we were protecting. We were off sort of held in reserve.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of just a screening action?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

We were most of the time over the horizon.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were you looking for submarines or just surface ships?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Our sole role, at least the picture I got, was to be available in case a fight with one of big surface ships came along.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they had probably destroyers as part of the convoy looking for submarines.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. We would have been worthless for submarine protection. We had no sonar. We would have been just one other ship to be protected. But we got pretty well up into the North Sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Running primarily in advance of the convoys?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

My recollection is that we were a little further out from the mainland then the rest of the convoy. And there were all sorts of training exercises. In fact I recently read a book that Eddie Miller alerted me to called Battleship at War, which recounted the WASHINGTON's activities.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, the chap that wrote that came to East Carolina to use some of the collections.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

He did a good job. It sure reminded me of how boring a war can get. You spend day after day and week after week just steaming around in training exercises and every

now and then there would be some excitement--submarine contact or an air attack or something of that nature.

We were on the East Coast on Pearl Harbor Day, in port. I remember I was sitting in the wardroom playing cards with some of the officers when we heard about Pearl Harbor being attacked. We were fairly quickly put through the rest of the preparations that had been going on and we went through the Panama Canal, as I recall, in mid-1942. We headed out to the Pacific and I think it was on that first run out to the Pacific that we were put in company with the old LURLINE. She was a luxury cruise ship, one of the U.S. President lines, I believe. She was being used as a troopship and we were put in company with her the run from San Francisco to Honolulu.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was Ed Miller still with you? Or had he been signed to another ship?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I'm not sure just when Ed left but I'm pretty sure he was...I could be wrong on this being the time we were in company with the LURLINE.

Donald R. Lennon:

In talking with him, he talked entirely about Atlantic duty. He didn't say anything at all about being in the Pacific.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Maybe I'm wrong.

Donald R. Lennon:

He didn't give any dates as to when he left the WASHINGTON?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No, I would have had him on board for several months after we got into the Pacific. I remember one night having the officer-of-the-deck watch and the LURLINE was supposed to be keeping station on us. We were steaming, oh, perhaps, a thousand yards abeam of her, in fairly close for those big ships. She kept coming in closer and closer. We were supposed to hold our course, but I kept easing off a little bit to keep a reasonable separation. I called the captain to tell him we were having trouble with our cruise ship that was in company. We broke radio silence and called her and couldn't get

her. They had apparently set her on automatic pilot. Our impression was that there was nobody on the bridge awake. By that time we were streaming along not more than five hundred yards apart. If either one of us had had a steering casualty, we would have had considerable trouble. I forget how we woke them up. I'm guessing, because I don't remember how, but it was something like lighting off a searchlight, or firing a rocket.

Donald R. Lennon:

And that wasn't too safe to do out in the Pacific.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No. But I remember that quite vividly. Then I remember getting out to the first of many of the atoll anchorages that we were in. We arrived there fresh from the States with only a real quick stop in Honolulu.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had been to Pearl?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes, we had been to Pearl but not for any extended period and we then went out to this atoll. This was not too long after the Battle of Santa Cruz. The SOUTH DAKOTA was also in there, along with the carrier ENTERPRISE; I believe it was, with a big hole in her bow. The ENTERPRISE was obviously shot up enough so that she was going to have to go back for repairs. So there were durn few ships. I remember that. We were the only battleships.

I guess the big event of the war for me was November the fourteenth or fifteenth--the night action off Guadalcanal--when the WASHINGTON and the SOUTH DAKOTA and four destroyers were sent in. This was after night after night of action involving forces of whatever we could pull together and whatever the Japanese could pull together.

Well, maybe I ought to backtrack and describe my battle station. I was in the main battery plotting room. Ed Hooper was the F-Division officer. We had gotten very much interested in the capabilities of the radar that they had recently put on our main

battery directors. We had done a fair amount of studying of our pattern of shot at various ranges--what spread in range and deflection we could expect. We had worked up a system of working back and forth over a target, increasing the range until our spotters and our radar told us that we were definitely over the target, and then walking back until we were sure that we had covered it. We had found that without doing that, it was fairly easy to think that you were on the target and actually be short. This practice stood us in good stead that night because when we tangled with the KIRISHIMA, we used that technique of walking back and forth, and pretty well clobbered her. We came through it without a scratch. No, I take it back, I was reminded by that book that we had a hole in our search radar screen on top of the mainmast. It was a hole where a shell had gone through. It was the only damage to the WASHINGTON.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's pretty lucky.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

The action itself was fairly brief, and almost as vivid a recollection as the action was the chasing around avoiding torpedoes after the principal action.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were the torpedoes being launched by Japanese submarines or by destroyers?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

In fact, I would guess that a significant percentage of them were imaginary. A fair percentage of them were launched from destroyers and possibly some from submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you picking them up on sonar or what, because I know that some people didn't have sonar at that time?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

We had no sonar, so it was from visual observation, and I know for a fact that the skipper maneuvered violently several times. The navigator's battle station was in the conning tower where he was close to blind as far as being able to see what was going on

at night. The conning tower had slits for limited observing but little if anything in the way of equipment to work with. He did have a dead-reckoning tracer. And the dead-reckoning tracer showed us crossing the end of Savo Island--this in a battleship that drew something like thirty-five feet! That's understandable because the dead-reckoning tracer had not been updated since the action began. At the start of the action there had been considerable maneuvering and the accuracy of that particular piece of equipment just began to go to hell in a hand basket after a couple of hours of maneuvering without any resets. I wasn't in on the voice circuits, but I'm sure the navigator was yelling at the bridge telling them what his information was telling him and the captain was working by eye.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was the captain at this time?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I'll be darned if I remember. Captain Howard Benson was the commissioning skipper in the spring of 1941, and we're talking about the fall of 1942, so he was possibly still the skipper. But I'm not sure. It may have been Glenn Davis, who relieved Benson. I'm sure that book will tell us.

Donald R. Lennon:

The author used Davis's papers. We have Glenn Davis's papers and an oral history interview.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

He also must have had access to every deck log that was ever written on the WASHINGTON.

Donald R. Lennon:

They're in the National Archives for everybody to see.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I see. His book is full of little vignettes that you could only get from the deck log.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now you said you were there with two battleships, the ENTERPRISE, and some destroyers.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

At Guadalcanal, there were in our group just the two battleships and four destroyers.

Donald R. Lennon:

What I was wondering was if the four destroyers were primarily trying to counter the torpedo danger.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. We had gone in there with the report that the Japs had a major reinforcement on the way with three or four transports escorted by a sizeable force involving some big ships. The SOUTH DAKOTA, when she was damaged, lost the capability of staying in formation with us and there came a point where some in the WASHINGTON were not sure that we weren't shooting at the SOUTH DAKOTA. Our plotting room track made us certain we were not.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any hard feelings between the WASHINGTON crew and the SOUTH DAKOTA crew or any differences?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes--some.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then or later?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I find myself wondering whether what I'm thinking is my actual recollection or whether it is what I've recently read in that book! I think the book over exaggerates. I do know that there were some fights involving some of our personnel and theirs. I guess among the wardroom people, the officers in the WASHINGTON--the junior officers in particular--it was sort of a good-natured grudge. “So you can't believe that she shot down thirty-seven planes.” Nobody could do that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I had heard that the WASHINGTON people considered the SOUTH DAKOTA people to be something of glory-hounds.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

It certainly didn't go to the extreme of actual grudges. Hell, I remember going aboard the SOUTH DAKOTA after the battle and looking over the damage that they had

had and being on very friendly terms with the people. There was one officer on the SOUTH DAKOTA I particularly remember, Bud Slack. He was quite a bit senior to me. In fact he was more a contemporary of Ed Hooper, my boss. But Bud was a hell of a nice guy. He came down with Parkinson's disease not too long after the war.

Well, Guadalcanal was my biggest experience in the war. I guess the second biggest was the collision with the INDIANA. The only real damage that our ship got through the whole war was in that collision. I was standing watch in the plotting room, on the mid-watch. It wasn't too long after our bunch had relieve the watch and the other people had gone back to their quarters. From where we were in the plotting room it was all very sudden. We heard the siren, “stand by for collision,” and then there was a tremendous sense of impact. It was hard to believe that you could stop that big a hunk of metal as quickly as we did. The guy I had relieved in the plotting room had gone to his cabin, which was one of the forward-most cabins in the ship, and he was killed.

Donald R. Lennon:

What caused the collision?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

The INDIANA had orders to commence fueling a destroyer. We had been refueling destroyers the preceding day and had topped off all but one of them in company, and she had been given orders to fuel that one during the mid-watch. At the time to do this, she put out word that she was proceeding on a certain course. The rest of the formation was zigzagging and the zigzag leg that we went on shortly before the collision put us fairly close to a ninety degree heading with the INDIANA. As I recall, the final explanation of what had happened was that she was not on her stated course.

The first our ship knew of the situation was when she was in fact crossing our bow. The guy who was the officer of the deck on our ship, Hank Seely, did everything anybody could do to avoid and then minimize the damage of the impact. As I recall, and

I'm again not sure if I'm citing my own recollections or remembering the book that I just read, Seely, our officer of the deck, wound up with a commendation and the skipper in the INDIANA wound up with a court-martial. But we lost about thirty-five feet of our bow.

We limped into Majuro. It was the closest allied anchorage with any ship-repair capability, although it was very limited. We had some very temporary repairs made there and steamed back to Pearl Harbor at not much more than ten knots because of the big blunt damaged front end. About all they did at Majuro was burn off the things that were hanging out over the sides and shore up the bulkheads, but it was still very much a crushed-in front end that we had.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did they put on at Pearl?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

At Pearl they put on a blunt bow. It was pointed but not very much. Then we went back to Bremerton. I remember coming into Puget Sound, and after making the last bend before the shipyard came in sight, seeing right at the head of the dry-dock that we were assigned to a brand new bow sitting there waiting for us. But it still took them quite a period to get it on and get all of the electrical, hydraulic, water, and whatnot connections made. So everybody got a little unexpected leave. I got off as I recall for a couple of weeks. I flew East.

During the rest of the war we saw lots of action--shore bombardment and Lord knows how many air attacks--some real and some of them expected but not materializing.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were on the WASHINGTON the entire war then?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I was on the WASHINGTON until June of 1945. At that time I came back to go to graduate school.

In connection with the shore bombardment, we devised a system of controlling the gunfire in what you call indirect fire--where you can't see the target that you are shooting at. This was a technique that was well known but we refined it down to a very accurate system. We used the main battery directors with their radar to track a fixed point on the shore. If we had a lighthouse or something that we could get an exact bearing and range on, that was ideal. We would use one of the range keepers in the plotting room solely as a means of tracking that stationary point. We'd get a solution on the range keeper.

Of course, if there were no current, the range keeper had automatic entry of our own ship's speed and course; and if there were no errors in the range keeper, the solution on that stationary target would be zero speed. But there always was a little current or a little bit of error so we would work on the solution in the range keeper just as though we were working on a moving target. Using a protractor, we made a sort of jury-rigged plotting device. We would plot our ship's position continuously on a chart, using the information from the range keeper, and then measure with that protractor on the plot our bearing and range to the target that we'd been assigned. We'd get a new reading of the bearing and range to the point we were tracking every thirty seconds. Then ten seconds later, we'd have a new bearing and range to the target that we had been assigned. So we were keeping a very accurate track of this target that we couldn't see. We found that it really paid off. Many a time we'd open fire on a target that we'd been assigned but couldn't see and be right on the first salvo.

On one occasion, I think it was at Okinawa, we were sent in to support a Marine division that called for supporting fire very close to their front lines. I'm thinking it was something like two-hundred yards from their front lines.

Donald R. Lennon:

It had to be pretty precise from there. Would you use your big guns for that?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That particular one was not for the big guns. That was for five-inch guns. But we did use big guns for a good many instances when we were assigned a fortified installation. We'd have our OS-2U Kingfisher up spotting for us. I can remember on a number of occasions when we fired the first shot before the Kingfisher pilot, Bill Lemos (a classmate), was sure of the target's location. He'd see our shot land, making the target obvious to him, and then he'd tell us “up a hundred” or “right fifty” or something like that. But that was a capability you only had in something like a battleship where you had the main battery directors with very precise radar and with a PPI scope down in the plotting room in addition to the one in the director. In the plotting room, we could see what we were tracking. On our own we installed changes in the shipboard wiring so that our main battery range keepers could control the five-inch battery, which nobody had ever contemplated needing until we started using the indirect fire system.

As far as shore bombardment was concerned, we were involved at Iwo Jima. In fact, at Iwo Jima we were involved in “call fire.” The Marines had called for our support in firing on a target, and it went on for hours on end. It went on for so long that we finally went to Condition II from General Quarters and I managed to get up topside to see what was going on. That was the first time that had happened.

Donald R. Lennon:

After a while not being able to see the action would get kind of frustrating.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That's right. And it's not only frustrating, it's a little bit of an eerie feeling. In the Guadalcanal action, you knew there was somebody out there shooting at you, but you were not going to get much advanced notification if they homed in on you.

Oh, one other anecdote of an incident which took place pretty late in the war. It was after Roscoe Good had taken command. I had officer-of-the-deck watch one night

on mid-watch, I believe it was, and Bill Fargo, a good friend out of the Class of 1939, had the sky-control watch for the anti-aircraft battery. We were in a carrier task group and had just completed air operations. The group had a small combat air patrol and the carriers had just relieved that patrol. They had first launched the relief aircraft and then brought in the ones being relieved. We were on station with the carriers and the last of the carrier aircraft had come in when a bogey (unidentified aircraft) showed up on the screen, coming straight in. The first report of it was not at too great a range, so I buzzed the captain. Roscoe Good, bless his soul, was a pretty heavy sleeper and he hadn't had much sleep in the preceding several days, so a sleep voice answered. I said, “Bogey coming straight in at twenty-five thousand.” (I have forgotten what the exact range was.) “Very well,” I heard the sleepy voice say. Well, then it got in to twenty thousand. Our five-inch guns could shoot about fifteen thousand yards but they weren't very accurate till you go to ten or maybe even less. They were probably best from around five or six thousand yards in. From about fifteen thousand yards in, Bill Fargo in sky-control was asking for permission to “open fire when ready.” I was sending back word, “Wait, I'm buzzing the captain!” This went on and on, and God knows how many times I tried to get the skipper up. The range finally got to about seven thousand.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he respond when you buzzed most of the times, or just that first time?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

He was just asleep. Well, half the time there was no response and half the time he answered practically in his sleep.

Donald R. Lennon:

He was not even conscious of what you were saying to him and what he was saying to you.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That's right. I knew the situation. I'd been in the same boat myself. Well, anyway, this bogey got in to about seven thousand yards and Bill Fargo was still asking

for permission to open fire, so finally I said, “Permission granted.” And of course the first shot from those five-inch guns woke the skipper up and he was out in a hurry. Over the din of the guns, I told him what was going on. He looked around real happy, “Well done.” About that time I could hear my junior officer yelling at me, trying to get my attention to tell me that we were in Condition Red. Condition Red was the condition they set during flight operations that said, “You will not shoot at aircraft.” This was to make sure that you didn't shoot any of your own aircraft.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why didn't you know that they were already?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Don't ask me. It had been so long since the last of our aircraft had come aboard that there was no question whatsoever in my mind or in Fargo's mind that it had been cancelled. We had counted the aircraft as they came in. We had changed course back from the recovery course. Well, let me finish the story. The real happy look on Roscoe Good's face just changed to absolute chagrin. And Roscoe had a temper. So I figured my goose was about cooked. I told the junior officer of the watch to ask the OTC “Interrogatory Condition Red?” He went on the air, “Interrogatory Condition Red?” The word came back, “Negative, negative, Condition Red.” A smile came back on the skipper's face, a smile came back on my face, and the aircraft either turned off or was shot down. It was a pretty overcast night. We never did see anything. We didn't see him flying off. Our best guess was that we had shot him down.

Donald R. Lennon:

But it was an enemy aircraft definitely.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Well, it definitely wasn't one of ours. The OTC, or whoever had the watch for the OTC, had just forgotten to cancel Condition Red when the last of their aircraft came in. But that was rather an exciting experience.

I got two wounds during World War II, but I didn't get a purple heart for either one of them. The first was when the task force went into one of the atolls, I think it was Eniwetok. We had an organization of gunnery officers of the battleships, and we called ourselves the Acme Gun Club. It was called the Acme Gun Club because Acme ale was the beer that somebody had the nerve to send out to the Navy in the forward area, and it was the lousiest beer you ever put in your mouth. The Acme Gun Club was going to have a “meeting” on the beach. I was sent in that morning with ten or a dozen other guys as a working party to get the place organized and to set up the bar for our meeting. Well, I was out there from about nine o'clock in the morning to about four in the afternoon in nothing but a pair of shorts. I was out there in that South Pacific sun after not being in the sun for God knows how long. I had the niftiest case of sunburn you ever saw. I guess that was not really a wound but it laid me out for a while.

Donald R. Lennon:

Physical disability.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

The other injury happened one morning when we had an air alert before dawn. I had, just as of that evening, swapped bunks with my roommate. I had been in the lower bunk and he in the upper, but he had a cold or something and was expecting to be up and down quite a bit so we had swapped bunks. I heard the alarm and I jumped out of the bunk just as I had been used to jumping out of the lower bunk. Well. I was about four feet higher off the deck then I thought I was and I lit on my heel and split it wide open. I limped down to the plotting room with what must have been about a two-inch or an inch-and-a-half flap of skin off the heel. So that was the wound.

Donald R. Lennon:

The WASHINGTON never had any kamikaze attacks against it, did it?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

We never had any hits. We were in many formations with kamikaze attacks being fought off, and we had a couple of them that were near misses. But we never had a hit.

Donald R. Lennon:

I suppose down in the plotting room you were not as conscious of this type of thing as if you had been out on the deck somewhere.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. I was in the main battery plotting room, and we had sort of the feeling that there was not a damned thing we could do about it. I just hoped the guys that could do something, did it right.

On one occasion one of the carriers, the FRANKLIN, was hit by a kamikaze that had slipped in pretty much undetected. I guess we were steaming with the normal Condition 3 watch set. We weren't at battle stations, I know, because I either had the deck or had just been relieved. This carrier, fifteen hundred yards or so away from us, was hit and badly damaged. She made it back to the States, however. They brought her through the Canal and around to New York where she went in for repairs. It was all topside and hangar deck damage but more than what the shipboard forces could repair. She was pretty much beaten up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, this brings us up to June of 1945. Would that be a good stopping point for today, when you're leaving the WASHINGTON?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I guess it would. It's certainly a good transition.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any other thoughts on the WASHINGTON?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Well, it certainly was a rather moving moment when I left her. I got orders to go to graduate school and was going to leave the ship in the Philippines. In fact, I was scheduled to leave the next day, when she was ordered back to the States. So I came on back with her.

Donald R. Lennon:

You left her stateside.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I left her at Bremerton. It was very, very sad. I did see her when I was at post-graduate school in Annapolis. She and the NORTH CAROLINA came in to the Academy.

They were being used as transports, getting the troops back from Europe. They came in for a brief overnight at the Academy. Not too long after, she was moth-balled at Bayonne. Not too long after that, or it seems like it was a short time, they sold her for scrap. I hated to see that. Every time I drive south and drive past Wilmington and see the signs for the NORTH CAROLINA, I grouse a little bit about the fate of the old WASHINGTON.

We had a junior officer who had reported back to the ship a few months earlier. He was a lawyer from Boston. He had had a very minimum amount of training before he was sent out, but in due time he was qualified to stand officer-of-the-deck watches in port. This was at the time when “Silent Jim” Maher was skipper of the WASHINGTON. “Silent Jim” was known for his very adequate voice and a certain amount of temper. Well, this guy came into the wardroom after he had finished his watch and said, “I guess I've blown it.” He had been standing watch on the quarterdeck in port and the phone had rung from the captain's cabin. The captain said, “Where the hell is my water?” This guy says, “I'll see to it right away, Captain.” So, as he put it, “I had the messenger fill a pitcher with ice water and take it up to the captain's cabin.” When the messenger got there he found the captain in the shower, completely soaped down--the water in the shower had stopped. Of course this junior officer caught a certain amount of hell because of this, but it wore off quickly.

[End of Part 1]

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

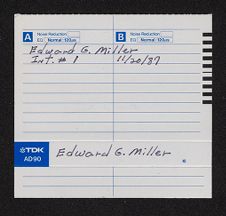

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Captain Frank M. Sanger, Jr | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| May 11, 1988 | |

| Interview #2 |

Donald R. Lennon:

When we were last together, we had pretty much gotten to the point of your leaving the WASHINGTON at the end of the war. Did you remember some additional incidents that we need to cover before we part company with the WASHINGTON?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. There was one rather memorable incident that I somehow left out. When the WASHINGTON returned to the forward area after an overhaul in Honolulu, we joined the rest of the fleet at Kwajalein at one of the atoll anchorages. Captain "Silent Jim" Maher was our fairly newly arrived skipper, as I recall. He relieved while we were in the Navy yard. When we steamed into the atoll, where the rest of the fleet was at anchor, we were sort of the center of attraction. There were not too many battleships in the force at the time so a battleship joining the fleet was an occasion. We were at quarters for entering port, with our division in formation on the starboard side, just abreast the number one turret (the farthest turret forward). There were two other divisions standing in ranks forward of where we were, one of them pretty well up in the bow of the ship. As we approached the anchorage, the order came from the bridge to let go the anchor. The anchor chain started playing out from the windlass in normal fashion, but after a few seconds, we could tell that things

weren't quite right. The chain seemed to be going faster and faster. All at once, a lot of people realized what was happening and some of them started yelling, "Clear the Fo'c's'le." Our division was aft of the windlass so we were in no particular danger. But the divisions that were up forward of the windlass were, because when the end of that chain came out it was going to go slashing across the deck. It could very easily kill people. As I recall, the individual links of that chain weighed something like sixty pounds. They were tremendous things. But there we were, the newly arrived battleship with crew all in whites, and then all of a sudden, everybody was diving over the side. It must have been quite a sight to the surrounding ships. It took two or three days to recover that anchor.

Donald R. Lennon:

It went all the way out to the bottom.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes, to the bitter end. It went out through the hawse pipe. The whole thing, anchor and total span of chain, went to the bottom. We went off on a mission, came back, and finally recovered the anchor some weeks later.

Donald R. Lennon:

No one was hurt?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No one was hurt.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did some of the crew actually go overboard?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Oh, yes. If they had not, it is very likely that we would have had some casualties. The first and second divisions were on the most forward part of the ship, in ranks. All of them went overboard. That was definitely one of my more memorable experiences.

When I left the WASHINGTON, I came back to graduate school. My first year of graduate school was at the Naval Academy. Our classes were held in a building over near the Naval hospital. It was dedicated to the graduate school and pretty well separate from the

main buildings at the Academy.

While I was there that first year, I met my wife-to-be. We were married in Erie, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1946. My brother-in-law, my wife's good friend that she had been staying with in Annapolis when I met her, and I left for Erie the Friday afternoon before the wedding. We ran into a dense fog in central Pennsylvania and had to put up for the night. We were almost late for the wedding. We were married that Saturday afternoon and went to Pittsburgh that evening. Sunday afternoon we drove from Pittsburgh back to Annapolis so I could get back to classes.

The graduate class separated when we finished the year at the Naval Academy, and everybody went to one or another of the half dozen schools that were taking Navy graduate students at the time. I ended up in Cambridge, at M.I.T. I was there for two years. My wife and I were very fortunate while we were there as far as living accommodations were concerned. June, my wife, went up to Boston the spring before we left Annapolis to find a place to live. She signed a contract on an apartment that some Navy friends had been occupying. They were leaving. June came back to Annapolis very happy about having succeeded in her mission. She hadn't been back for a week when we got word from the landlord that he "was sorry" but he "was going to have to cancel the contract. A relative needed the apartment." So just about the time we were supposed to be leaving for Cambridge, we found ourselves with no place to stay. We went up and spent three or four days frantically looking for a place to live. We found absolutely nothing that was even halfway acceptable. We happened to be driving out in the suburbs between Lincoln and Waltham, just outside of Cambridge, when I saw a "For Rent" sign in front of a beautiful little cottage. The owners had been living in it but had moved out and decided to rent it out

for awhile. We lucked up with about as nice a place as could have been found.

While we were there in Cambridge, our son was born. In fact, there's a slight little anecdote concerning this. After our first year at M.I.T., our particular group was sent to Washington for a field trip. We were to spend time at the Bureau of Ordnance, which was sponsoring our educations. Our baby was expected that August. Another couple, Lou and Janet Tuttle, were also expecting. They were very good friends. In fact, Janet was the girl my wife was visiting when we met. Lou and I were having a running bet as to who was going to have the first offspring. After a number of false alarms, I called June one Saturday morning and asked her if she was planning to have a baby that weekend. If she wasn't, I thought I had better stay in Washington because coming up for those false alarms was getting a little expensive. "No," she didn't think she would be having the baby. Well, sure enough, six hours later, I got word that she was in the hospital and that the baby was on the way.

Donald R. Lennon:

They have a way of doing that.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That's right. I took the midnight train from Washington to Boston. I went in to see my wife and actually saw our baby before my wife did.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you got there in time.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Not in time for the birth, but in those days, birthing was not the social occasion that it is these days.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about your course of study at M.I.T.?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

It was ordnance--physics/electronics.

Donald R. Lennon:

M.I.T. was offering physics and electronics courses that had an ordnance slant to them?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Well, the primary reason for the ordnance slant was that the Bureau of Ordnance was sponsoring our education. There were two courses at M.I.T. that the Bureau of Ordnance sponsored: ours and the fire control course. The fire control course had a number of subjects that were the same as ours. About fifty percent of the courses that we took were the same. Part of our group was switched into a nuclear-oriented course after our first year. In fact, we all had the opportunity to volunteer for it. I elected not to. Why, I can't remember. Maybe some of Rickover's reputation had gotten around.

We were at M.I.T. for two years so that made it the spring of 1948 when we completed the course. I was ordered to the LITTLE ROCK as gunnery officer. I relieved Rod Middleton, a good friend and classmate, at Newport and headed for the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the LITTLE ROCK a heavy cruiser?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

She was a light cruiser. She had six-inch guns. We had a cruise in the Mediterranean. We spent most of the time at sea; however, we did get into Marseilles and some of the Greek islands. It was an interesting cruise.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this primarily maneuvers or visiting ports?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I think our main purpose was just to show the flag in the Mediterranean. We had, as I recall, two of our light cruisers, a carrier, and perhaps half a dozen destroyers comprising the Mediterranean force at that time. The thing I remember most on that tour of duty was trying to get hold of June by phone at Christmastime. You had to make arrangements ahead of time to make sure that the lines were going to be available. It was quite a bit different from the direct dial to Europe that we have now. Finally, after having worked for a week or so to plan this call, when it went through, the transmission was so poor, we could barely make out what one another was saying. We could catch about every third word.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was quite a drastic change from what we have now.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

It was quite a bit of difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

In this 1948-49 period, were very many of the officers' wives there in the Mediterranean, following the fleet, or were most of them stateside?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Most of them were stateside.

Donald R. Lennon:

Later, you had a change in that, didn't you?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That triggers my memory. I definitely joined the ship in the Mediterranean. June went to Erie to stay with her family. I don't believe any of the wives, in our ship anyway, were in the Mediterranean area. When we completed the tour in the Mediterranean, we came back to Newport fairly briefly. My wife brought the youngster down and we stayed with friends for a few days. Then I proceeded to the Brooklyn Navy Yard with the LITTLE ROCK for decommissioning. June and I rented an apartment in Manhattan.

From there, I was ordered to the Pacific Fleet Training Command in San Diego as the officer in charge of the Fleet camera party. The Fleet camera party was a small command whose job was to photo-triangulate gunnery exercises and to establish how well the ships had done in those gunnery exercises. I was stationed at the training command headquarters in San Diego. The camera party had three groups, as I recall. There was one there in San Diego, one at Pearl Harbor, and one up the coast somewhere. I can't remember just where.

While there, I gave quite a bit of thought about how we might improve the accuracy of our measurements. I came up with a system that involved using manned accompanying ships so that you had a longer base line to measure your shot-error with. It provided a lot greater accuracy. But the fact that it involved additional ships and coordinating what was

going on between them, made it a little cumbersome; so it never really got off the ground.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was most of the duty off the California coast or did the Fleet take part in these exercises in triangulation firing maneuvers all over the Pacific?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

It was primarily off the coast. Actually, my job was strictly administrative. I was on shore. There are a couple of amusing vignettes about that tour. We had a small budget for the camera party's operation that was administered by the Naval Supply Depot in San Diego. It was something on the order of twenty thousand dollars a year. The Supply Depot would send me a monthly report showing me where we stood on expenditures. During that period, the Supply Depot converted over to their first computerized system.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is early! This was in 1949?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes, in 1949. The first monthly report that was generated by that computerized system told me that my little rinky-dink command was two-plus million dollars in the red. Tremendous. It was the saying, "Garbage in, garbage out."

One of the other things I remember about that tour was that I used to stand duty watches with the staff officers on the training command staff. I would have my turn as duty officer right along with the rest of them. A duty officer was the point of contact for anybody who needed to get hold of the command. The Korean War was going on so there were reports coming in on what was going on in the war. Every night a lengthy coded message would come in from the commander in the Korean zone, bringing other commands up to date about what was going on in the war. The standard routine was that when the message came in, the signal people would waken the duty officer, and the duty officer (at four in the morning or whenever it was) would roll up his sleeves and start decoding the message. The objective was to have the message available on the Admiral's table at

breakfast time. What got to be quite amusing was comparing the information that was in that top secret coded message with the information that was in the San Diego Union (newspaper) that morning. Ninety percent of the contents of that top secret message, which you had worked to decode for two hours or so in the middle of the night, was in the morning paper!

About the time that I had settled down in the job in the training command, I began to get sort of a frustrated feeling that the education that I had spent three years accumulating in graduate school was not being used. I had given some thought before then of going into engineering duty, and I finally convinced myself that that was the thing to do. There was considerable opposition to the concept of engineering-duty-only (edo) officers in the Bureau of Ordnance. The Bureau of Ordnance had for many years put as much in the way of money into technical education for its officers as any of the other bureaus. The top command in the bureau were convinced that the first-hand experience at sea with the ordnance equipment was essential, so they very strongly opposed the whole concept of ordnance engineering duty officers. Something happened about that time that persuaded them to open the door just a crack, and I got in through that crack. At the time I went into it, you could count on your fingers the number of ordnance engineering duty officers. But from that time on, it was a very gradual period of growth. There had never been an officially closed door to flag rank for ordnance engineering but there was everything but. I remember a letter signed by the Chief of the Bureau to ordnance engineering officers, pointing out to them that they didn't stand much of a chance for flag rank, but that they did have compensating benefits.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he specify what the compensating benefits were?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. He said that we were in a situation where we were working very closely with industry and that undoubtedly, at the time of our retirement, we would be in a very good position for finding a job in industry. (That is what I did and a good many others did so as well.)

I was sent back to the Bureau in Washington for my first tour as an ordnance engineering duty officer, in the Guided Missile Development Section. I worked on the Terrier and the Talos, surface-to-air missiles. We also worked with several other missiles that were less well known like the Kingfisher family, which were anti-ship missiles. One of them was the Petrel, which was a flying torpedo. Another was Greed(?), which was one of the early guided bombs.

I've thought of a story that has to do with the Sidewinder, one of the better conceived air-to-air missiles. It was conceived at the NavalOrdnance Test Station, Inyokern, by the director out there, Jerry McLean(?). It had sort of been an orphan child as far as fiscal support from the Bureau was concerned. I guess there was a certain element of "not invented here" involved. The Bureau had never had anything to do with it, so it took a while for the Bureau to really start giving it its full support. After the Sidewinder had made a couple of spectacular intercepts and had gotten quite a bit of publicity, I remember Captain Bill Bryson, who was the head of the RE-9 Guided Missile Development Branch, good-naturedly grousing about how he was supposed to be the physician in charge of the birth of all guided missiles for the Bureau, and here the best one to come along had been hatched by a damned midwife.

We lived in Falls Church [Va.] at the time. We had bought our first home there in Broadmont(?). When my duty tour wound up, I was ordered to Mishawaka, which is

adjacent to South Bend, Indiana, as the Naval inspector of ordnance at a missile plant operated by Bendex. We were building the Talos, a surface-to-air missile. June stayed on behind to sell the house and to let Randy, our son, finish that year at school. They came out that summer. We knew that we were not going to be in South Bend for very long, so we tried our darnedest to find a place to rent that would meet our minimum standards. South Bend was something like eighty-five percent owner-occupied, even in those days. There was practically nothing available. We wound up buying. When we left we were forced to sell under fairly bad times because the Studebaker plant was closing and things weren't all that good.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long were you there as Naval inspector?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

A little over two years. I came back to Washington to a job in the Chief of Naval Materiel office. This lasted for about a year. I had an opportunity to move over to the Special Projects office, to the Polaris Program, which I was very happy to do.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was Captain Rush involved in the Polaris program at one point?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. Charlie Rush was in the Naval Inspector's office in the Lockheed Plant at Sunnyvale, California. I relieved Rod Middleton (for the second time) in the Special Projects job as missile projects officer, head of the Missile Branch. That was a very interesting tour of duty. I spent many a week down at Cape Canaveral in connection with the shakedown firings there.

My first major assignment for the Polaris program was to represent Admiral Raborn and the office at the outloading of the GEORGE WASHINGTON in Charleston. She had been fitted out with nuclear missiles and was going on her first patrol. I must admit that it was quite a sensation realizing that I was involved in and had a responsible assignment in

what was really a pretty historic operation. We, as I'm sure you can imagine, found ourselves handling those missiles with very tender hands and kid gloves.

Donald R. Lennon:

How much were you involved in the testing of them?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Quite a bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was most of the testing done?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

At Cape Canaveral. We had a launching facility on the shore. Of course, every submarine that entered the force had sort of a graduation exercise at the Cape of firing a missile with a dummy warhead. Levering Smith, my boss, and I probably were aboard for at least the first half dozen or so of those exercises. Probably more than that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they use land or sea targets?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Sea targets--just a target point--in the open sea. There was no actual physical target there. It was a point in the open sea that was well monitored with listening devices so it could be established precisely where the missile landed. You could score a hit or a miss. In addition to these, they had what they called SDAP, shakedown and ______. I can't remember what the "P" stood for. In addition to those, there were development tests going on for the more advanced missiles that were coming along. Most of those would be from a land-firing installation. Occasionally, however, there would be a reason to fire a development shot from a submarine.

A couple of things from that period sort of stand out in my mind. We began to have a significant number--more than were acceptable--of flight failures early in the flight. In the process of brainstorming what could be going wrong, I raised the question of whether the styrofoam plugs that were in the nozzles of the first stage could be impacting the control jetavators, fracturing them, and causing the failure. That tied in with the timing and the

nature of the failure from what could be observed. We went into a crash program of testing at the facility on San Clemente Island. This facility had been built in the early days of the program to check out the launching system. We very quickly developed a "cut-grain," we called it, a dummy missile with a partial, live, grain propellant that burned with the full force of the regular propellant, but for less than a second. I think it was a half a second. So we had the forces that were involved at the launch time occurring at the launch testing facility, but we were able to catch the hardware and reuse it. We could turn it around fairly quickly and reuse it. Over the course of a couple of months, we established very definitely that one out of four times there would be impact with one of those styrofoam plugs on the jetavator control mechanism and that it would cause the flight to abort. We corrected that one.

Another similar situation developed when we had a pattern of failures occurring toward the end of the first-stage rocket burning. Again, there were more failures than were acceptable. We postulated that we were getting separation between the rocket propellant and the case of the rocket, creating a surface for the flame to burn on up against the case, and rupturing it. It was somewhat reminiscent of what happened to CHALLENGER, although there was no tie-in with the temperature in our situation. Temperature was the one environment that we had a fairly good handle on, because all of these missiles were in launch tubes within a submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have to worry about it icing.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

After two years as missile projects officer, I moved into the deputy technical director's job. I was deputy to Levering Smith, with interest and responsibility across the total weapons system, not just the missiles. In 1964, I rather reluctantly left the Special

Projects office for duty with the Anti-Submarine Warfare Project office that was just being established. I went in there as technical director and later as deputy director of the office. It was quite a different situation from the Polaris job. I guess the big difference--at least the thing that I remember the most--was the fact that in the Polaris program, there was no question in anybody's mind but what your office needed to be there. The country needed the program. But the Anti-Submarine Warfare Project office was sort of laid in on top of all the existing organizations--the Bureau of Ordnance, the Bureau of Aeronautics, the Bureau of Ships--that were involved in ASW. We spent as much time justifying to our compatriots the need for our office as we did in doing things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you developing new missile systems?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

We were involved across the board in the development, production, test, and use of anti-submarine systems.

Donald R. Lennon:

Specifically, what kind of systems were they?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

They were torpedo systems.

Donald R. Lennon:

Generating new torpedo systems.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. We also had responsibility for the existing torpedo systems in the fleet, and the maintenance and repair operations. We had our fingers in everything.

Donald R. Lennon:

By the mid-sixties, was the torpedo still needed?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes, no question about that. I guess there was certainly a less compelling sense of urgency than there was with the Polaris. Anti-submarine warfare is something that has been around for many, many years and it's going to be around for many, many more. In my opinion, if it's not adequately taken care of, it could cause the country real problems. So far, we've managed to stay comfortably ahead of the Soviets in ASW.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm going to play the devil's advocate: In modern warfare, not just American, in any modern Navy, is the submarine vital primarily as a missile-launching vessel? How is it most important to the defense of a modern power? What is its role in the modern Navy?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

You have, of course, in both our fleet and the Russian fleet, ballistic missile submarines that play a very significant part. In our case, I think it's a significant part of the nuclear deterrent. You also have in both navies, and in all the major navies of the world, attack submarines that exist for the more traditional role of that navy controlling the seas. Now, I don't think I can rank the importance of those two functions. As long as the nuclear deterrent works, the actions that the Navy is going to be involved in are going to be the more traditional ones.

Donald R. Lennon:

How drastic was the change in the role of the submarine between 1944 and 1964?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

There were two tremendous factors involved there. There was the advent of nuclear propulsion that made the attack submarine a true submersible, not a surface craft that went down for a brief sojourn underwater. Almost concurrently, there was the advent of nuclear weapons and the sea-based ballistic missile programs. I guess comparing the submarine forces of today with the submarine forces of World War II is like comparing apples and oranges or watermelons and pickles.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the sixties, when you were working with the submarines, was the anti-submarine effort keyed primarily to torpedoes and other traditional depth-charging? Were you using the same kind of weaponry that you had been using twenty years earlier?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

There were what you would call evolutionary improvements in torpedoes, depth charges, mines, and, of course, in sonar. There were revolutionary improvements in missile-born weapons like Subroc, for example. In the sensor field, there was the advent of

far more capable sonar than what used to be. It's a very interesting field. I can remember being told when I first got involved that it was certainly something that one could spend the rest of his life on and still have plenty left for the next guy to do.

I retired from the service in 1968, having convinced myself that the likelihood of making flag rank was not too good and realizing that my alternate career potential was not getting any better as time went on. I retired and had quite a strong feeling that I wanted to stay in the sort of work that I had come to know in the Navy. I wanted to get involved in weaponry in industry. So I went to work with Westinghouse in a new plant they had built at the foot of the Bay Bridge in Annapolis. I was the assistant to the general manager for the underseas division. He had a double hat. He was also the general manager for the astro-nuclear division in Pittsburgh. That involved underseas sensing equipment; however, it did not include the torpedo that Westinghouse had under development. The Mark 48 torpedo was over in the Baltimore plant in a different division. But all the rest of Westinghouse's ASW activities were in the division I went to.

I became very interested in some of the work that was going on in the astro-nuclear division in Pittsburgh. Westinghouse had been the prime contractor in the Nurva nuclear rocket program. This program was being phased out and Westinghouse was looking for a useful direction in which to point the considerable talent they had had on the program. With the idea of a closed-cycle system using the gas-cooled-reactor technology that had come in with the Nurva program, a gas turbine engine in a closed-cycle propulsion system came to mind. We put many, many dollars of Westinghouse's research funds and many, many hours of work into this concept. It was a pretty big "bone" for the Navy to swallow. Admiral Rickover, rightly, was very reluctant to get away from the technology that he had

fathered and that he had seen develop into a useful, reliable, and safe system. The system we had conceived was very attractive because of its significant weight savings over the systems that the Navy then had and still has. There were, however, many major technical hurdles to be passed before anyone could even seriously think of putting something of that nature to sea. I have always felt that it was a good idea, but that maybe it was just a little too much of an undertaking. I've lost touch with what's currently going on in that area, so I don't know whether there is any significant activity still going on or not. I guess it's one of a number of things that you can think of that if you put enough resources into, could be made to work, but whether the country could afford to do it or not is a good question.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned Admiral Rickover. Did you work directly with him?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

No. It is hard to believe in thinking back on it that I spent the number of years that I did in the Polaris program and never had an occasion to even meet with Admiral Rickover.

Donald R. Lennon:

From what I've heard, you were probably better off.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

He was, of course, responsible for the platforms, the submarines, that the Polaris systems went into. One of the smart things that was done in the early days of the Polaris program was to make the decision to put the first systems not on new boats, but on boats that had completed their development. The GEORGE WASHINGTON was literally built by cutting paper--the cuts were done first on paper instead of on steel. Then the center section was cut and a new section was put in to house the missiles. In this way, there was not the problem of developing a new propulsion system and all the other things that go along with creating a new class of submarines. I'm sure that it prevented many, many a fight between Admiral Raborn and Admiral Rickover.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you remained with Westinghouse until you retired.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. More or less accidently, I did the smartest thing I could have done. Rather than work full steam up to the retirement point and then cut off, I slowed down gradually. I went into a part-time situation with them then the last year or so consulted with them. Rather than working my tail off and then all of a sudden retiring and finding myself frustrated, I eased into the retirement situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

A rather sizeable portion of your career--from the time you left the Pacific Fleet Training Command until the time you retired in 1968--you were involved in Special Projects.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I was involved in the missile programs.

Donald R. Lennon:

Several different aspects of it. Do you feel that going solely into ordnance engineering (as you were advised) was a detriment to promotion? In other words, if you had remained in the more traditional career scenario, would you have made flag rank?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

I don't really know. I think my inclinations were more toward the technical and administrative sort of work that the EDO was involved in than in the typical line officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was more rewarding personally?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes. As far as flag rank, I sort of doubt if it made that much difference. I'm sure my capability paralleled my liking for the work. I think I was a more capable technical person and administrative person than I was a line officer, and it very well could have caught up with me if I had stayed on as a line officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are there any other thoughts concerning any other aspects of your career from the Naval Academy on till now?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

There is one thing that might be worth commenting on. After leaving the Navy, I found the conflict-of-interest laws quite frustrating. They were, and I'm sure still are, pretty

constraining on retired regular military personnel. All of my work was done with the question in the back of my mind, "Am I going to get myself in trouble in the conflict-of-interest area?" They definitely put constraints on the sort of work that you can do and, I think, to some degree, a lid on the amount of good you can do.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would you give me an example of that?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

For example, in the work with the ASW Systems Project office, I had been quite directly involved in the MARK 48 torpedo program. Westinghouse was the prime contractor for the MARK 48 torpedo. When I worked for Westinghouse, the MARK 48 torpedo was not a "no-no," but any involvement on my part had to meet the criteria that it not only be right but look right. It put definite constraints on my work.

Donald R. Lennon:

Since you had worked on it for the Navy?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

That's right. Any involvement on my part would definitely need to stay away from the immediate contact with the Navy officers.

Donald R. Lennon:

In other words, lobbying for that particular torpedo system would put you in a very delicate situation.

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Absolutely. The comment that I made about the system being unfair to a retired regular was in comparison with the fairly complete lack of restraints on the . . . well, the big example that comes to mind is the Congress and the congressional staff. Also, there are plenty of jobs in the Civil Service that are not constrained in the same way.

Donald R. Lennon:

White House staff?

Frank M. Sanger, Jr.:

Yes!

[End of Part 2]