| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

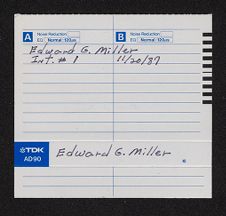

| Edward G. Miller, USN (Ret) | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| November 20, 1987 | |

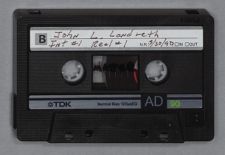

| Interview #1 |

Edward G. Miller:

I was born in Lehighton, Pennsylvania, a town with a population of about 5,500 people. It still has about 5,500 today. It hasn't grown. It is basically a Pennsylvania-German community on the edge of the anthracite coal region. My father was born in Lehighton and, I believe, his father was, too. But my mother came from the anthracite coal region. The paternal side of my family was German, and my mother had a Welsh father and a German mother. My Welsh grandfather came over here when he was twelve years old. His father had been a Welsh coal miner. My grandfather was a pattern maker in the anthracite coal mine industry. My dad was the stock clerk for the New Jersey Zinc Company in Palmerton, Pennsylvania.

I grew up in and went to school in Lehighton. It had a very fine school system, with harsh German discipline. Everything about the community was German. As a result, we came away with ethics based on hard work and frugality.

After graduating from high school, I went to Lehigh University for a year. The tuition was four-hundred dollars, which was all I had, and I worked in a restaurant part-time for my meals. At the end of that one year, frankly, I was broke; so I went back to work on the state highway as a chainman and rod man for a surveying corps. One day my postmaster came up and said, "Have you ever thought of going to the Naval Academy or

West Point?"

I said, "No I haven't."

He said, "Edward, you should think of that. Our congressman is always looking for young men to appoint and I'd be happy to talk to him on your behalf."

I said, "That would be fine, but I don't think I'd like West Point very much; I think I'd rather go to the Naval Academy."

To make a long story short, it was through the postmaster and his political influence that I had the opportunity to take a competitive exam. It was called the substantiating exam--just English and mathematics. Some people were eliminated because of physical handicaps. I finished first academically among the survivors and was appointed to the Naval Academy. I entered the Naval Academy two years after graduating from high school, a year of which was spent at Lehigh and a year of which was spent working. I just barely got in. I was nineteen years old and at that time, the age limit for entering was twenty.

I was very happy to enter the Academy, but once I got there and was exposed to the system, I was never particularly enthused about it. I can't say I enjoyed the Naval Academy. I did enjoy the United States Navy and I'm glad I stayed at the Naval Academy and graduated, because the difference between my feeling for the Navy at the Naval Academy and my feeling for the Navy during my twenty-seven years of service in the Navy was like day and night.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the Naval Academy disappointed you?

Edward G. Miller:

First of all, I was completely accustomed to discipline, but I was disappointed in the type of discipline and in the quality of some of the leaders among the officers there. We had some outstanding leaders--men with whom I enjoy friendships today and with whom I

served in the Navy later--yet there were others who I think were, how do I say, "chicken." It was either because of their own lack of security or because of some leadership inaptitude, but they just didn't come through too well to me and to many of my peers at the Naval Academy. One the other hand, there were some of my classmates such as Vic Delano and Bob Hayler who had been imbued in the Navy, and as far as their feelings for the Academy were concerned, they probably fared better at the Academy than I did. I didn't object to discipline; I just objected to some of the ways the discipline was administered.

There was a grade at the Naval Academy that was called Aptitude for the Naval Service. We called it our "grease mark." Every year at the Academy, you were given a mark in what your seniors believed your "Aptitude for the Naval Service" was--just how well you would do upon graduation. To indicate that my heart wasn't in it, a grade of 2.5 was passing, and for my senior year I had a 2.6, barely a 65 percent grade in Aptitude for the Naval Service. I don't think it had any effect on my career. As a matter of fact, it was always a big joke to me because I fared pretty well in the naval service. I had six commands at sea so I must have had some aptitude that I wasn't aware of at the Academy.

As a matter of fact, the most rewarding thing to me about the Navy was the fact that I did enjoy six commands. I think the name of the game for any naval officer is command at sea. I had two DEs, two destroyers, an amphibious ship, and an amphibious squadron. Every moment that I had those responsibilities was to me a moment of fulfillment.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we leave the Naval Academy, are there any particular incidents that you can put your finger on that would reflect on the way the Academy operated or any pleasant things that happened to you?

Edward G. Miller:

I'll go back and give one incident about my second class summer. During my

second class summer, I decided that I was going to try to get through the entire summer with no demerits. I was going to obey every regulation and so forth and really try to do a good job of measuring up. I succeeded until the night before I was to go home on leave. We had to go to a lecture at Memorial Hall in Bancroft Hall. About fifty yards from my room, I realized my wrists were perspiring through my jumper, so I turned the sleeves of my jumper up so that I wouldn't soil them. About ten yards from my room, the officer-of-the-day apprehended me and said, "Improper wearing of uniform, five demerits." Well, you know, it was that sort of thing!

Then at the beginning of my first class year, I was the midshipman in charge of the battalion office. Now the midshipman in charge of the battalion office was more or less the midshipman battalion officer for the day. The main officer for the day was up at the main office in Bancroft Hall at the entrance. You had all sorts of correspondence and materials that came through each battalion office that had to go to the main office. Well, one of the things that come through while I was in charge of the battalion office was a list of the sophomores (or youngsters) who wanted to attend a play by the Masqueraders in Mahan Hall. That was our auditorium. I gave the list of people to my messenger and had him take it to the main office. He came back and I said, "Did you deliver all those materials to the main office?"

He said, "Yes."

The next morning the company officer called me down and asked me where the Masqueraders' list was. I said, "I sent it to the main office yesterday."

He said, "Well, it's lost."

I said, "Sir, I can't help that. I sent it up and I asked my messenger if he delivered it

and he said 'yes.'"

He said, "Midshipman Miller, you have to learn to follow through on things. You didn't follow through."

I said, "What was I supposed to do, put on my coat and hat and carry it over to the superintendent myself?"

Well of course, that was the wrong thing to say. That was impertinent. That's one of the things that got me the 2.6 grease mark.

The point of the story is that I had carried out my responsibility in delivery to the main office. The midshipman in charge of the main office had delivered it to the commandant's office and the clerk in the commandant's office had misplaced it. Meanwhile, the midshipman in charge of the main office and I were put on the griddle because the thing had been lost through none of our faults.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did they expect you to follow through?

Edward G. Miller:

The whole thing didn't make sense to me. This is the sort of thing that went on--the tucked-up sleeves and the lost Masqueraders list. There were four or five incidents like that that I just didn't go for. Of course this affected your class standing a great deal because the Aptitude for Service Mark that you got in your senior year, as far as your class standing went, counted more than your entire freshman year's grades. So it affected my class standing considerably. Not that I was any brain, but I guess I graduated about 270 out of about 400, and I probably would have come out about 200 out of 400 without the bad aptitude marks.

The thing I valued the most at the Naval Academy was my peer group. I had two very fine roommates. One was John Kirk, the son of a Baptist preacher who evangelized

the Indians in Oklahoma and went out Sunday after Sunday, day after day really, and preached to the Indians. My other roommate was the son of a first generation German family, named Spritzen, from Shaker Heights up in Cleveland. John and "Dutchy" and I were very close. We were never close after we graduated, however, because "Dutchy" went into the Marine Corps and John became an aviator. The people with whom I became close were people who were in the destroyer force with me. I valued very much and still value the friends that I made at the Academy. This is one reason why I chose to remain here, much as I dislike Washington traffic and some of the things about Washington. I'm going to stay in the Norfolk, Washington, Annapolis area because of the large concentration of Navy people. Unlike people like yourself who went to a civilian college and after graduation never saw the people again, people like Victor Delano, Bob Hayler, Tommy Burley, and I not only went to college together but also served side by side for four, six, or eight years during our working careers. Now we continue to socialize together, tailgating at football games and so forth. I've never gone in too much for the old college ties, but these are people whose values, concerns, and interests are so closely parallel to mine that they make for very easygoing relationships. It's very nice.

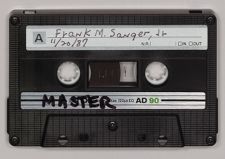

Once I graduated from the Naval Academy, from the first day that I hit the WASHINGTON, I enjoyed the Navy tremendously. I'll never understand, however, why I was sent, after I graduated, to the Ford Instrument Company and some of the other institutions that were making sophisticated electronic equipment. Immediately upon graduation, Frank Sanger, C. O. Marshall, Paul Wirth, and I all went up to New York to the Ford Instrument Company and to Sperry to learn about fire control equipment. Frank Sanger graduated number two in our class at the Academy, and I've always said that by the

time we left the Ford Instrument Company, I could operate all the equipment and Frank could have invented all the equipment. He could have built it all from scratch because he was such a very smart person. But that's where we wound up meeting after graduation. It was the time to be in New York. The war hadn't started; Times Square was in full sway; Tommy Dorsey was at the Hotel Astor every night; and Guy Lombardo played at the Hotel Roosevelt.

The four of us went looking for an apartment. Paul Wirth and I were the ones who found one and rented it. We were walking along the streets, hunting for an apartment, and we went in an apartment building and one of the telephone operators there said, "Look, there are some models going to move out from upstairs and they're looking for some people to sublet their apartment." We knocked on the door and there were these three beautiful girls and they said, " yes," they were going to move out, and that's how we got an apartment. So four young bachelors, fresh out of confinement in the Naval Academy, had a good time in New York for about four or five months. It was good we had all that fun because for months after that, months on end after that--we were at sea during the war and didn't get to see anybody.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't that a bit unusual? Most Academy graduates went directly to a ship assignment, did they not, rather than being assigned to additional training somewhere else?

Edward G. Miller:

Right. What happened was that the NORTH CAROLINA was being built in the navy yard in New York and the WASHINGTON was being built in the navy yard in Philadelphia. Captain Bob Clark (Class of '22 or '23), the executive officer of the Math Department of the Naval Academy, had been ordered to assume duty as executive officer of the WASHINGTON when she went into commission. So the captain of the

WASHINGTON, H. H. J. Benson, and the captain of the NORTH CAROLINA called him up and said, "Bob, we have a period of time here between graduation in February and commissioning in June and July, of five or six months, when we are going to have twenty ensigns on our hands. What should we do with them?" So Bob Clark called the Bureau of Naval Personnel, interviewed all twenty ensigns, and then decided what should happen to each one. Now, as a good example, there were two young ensigns assigned to the WASHINGTON who were sent to sea on a cruiser for duty in the engineering department. There was one who was sent to sea and assigned to be the assistant to the navigator. I would say of the twenty, probably fourteen were sent to sea, and the others were sent to shore installations. We were going to be assigned to the gunnery and fire control department. We were lucky to be sent to New York. During March, April, and May, we spent most of our time in New York learning and playing.

The Ford Instrument Company made hydraulic equipment, so while we were there we learned a little about the hydraulic control equipment for five-inch guns. We also studied the Mark I computer that computed the solution for firing five-inch guns. The Sperry Plant made what we called the stable element, a gyroscope. The top of the gyroscope passed through a magnetic field which created a signal that was transmitted to the gun mounts, and that is what kept the guns level when the ship rolled. They called that the stable element because no matter what happened to the ship, it kept your guns stable. We were sent to these factories to learn about this equipment, because it was some of the latest equipment and had been installed on but a few ships. They wanted some junior officers to know something about it. That's why we were there.

The officers of the Class of '41 who were sent to the WASHINGTON were Frank

Sanger, Rod Middleton, Charlie Quinn, Howard H. Montgomery, George Matton, Jr., Ramon Perez, Maynard Dixon, Bob Macklin, Johnny Burwell, and myself. Of those, Rod Middleton made flag rank--became an admiral. He was my roommate in the WASHINGTON and was one of the finest persons I ever served with in the Navy. He retired as a rear admiral about eight years ago. Shortly after a physical examination he dropped dead while jogging on a golf course out in California. In fact, of this list, Rod Middleton, Charlie Quinn, Ramon Perez, Frank Sanger, and Bob Macklin have passed away. To the best of my knowledge the other six are still alive.

This was a good gang in itself, but once we got aboard ship, we made new friends among the young officers coming from the V-7 program and R.O.T.C. One of my closest friends was Stan Turner and another one was Bob Bavier. They were fellows from Long Island. They had both gone to Williams College and were the intercollegiate star boat sailing champions. Stan was later killed in the collision between the INDIANA and the WASHINGTON. He and I were in the same division. Bob Bavier's father was the publisher of Yachting Magazine. Bob went from the WASHINGTON to command destroyer escorts. He commanded several, I believe, during the war. He came back and about four years ago he sold Yachting Magazine to a big publishing company and he and his family moved down to Charleston. I think it was a loss because Bob had been on the America's Cup Committee and was instrumental in defending the America's Cup through many races. He was also one of the governors of the New York Yacht Club and was very active in yachting circles. I think he's given all that up now in his retirement.

We had another officer in my division in the WASHINGTON and we called him "Whizeer White." Of course that wasn't his name. The real Whizeer White was a football

player and is now a Supreme Court Justice. Our "Whizeer White" came from Harvard and was the heaviest drinker on the ship. Every morning he came to morning quarters with dark glasses on. One morning he threw his glasses off and I was shocked, because evidently when he drank a lot his eyes became very bloodshot. He usually wore dark glasses on the ship to hide his bloodshot eyes.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was, of course, prohibited to legitimately have liquor on board American ships but I assume that people did have their private stock?

Edward G. Miller:

No. "Whizeer" did all of his drinking on shore. The only time I ran into drinking aboard ship was among aviators. I never heard of any drinking in the submarine Navy, and certainly in the ships that I commanded, there was no drinking. However, I do know in some service ships there was drinking, and aboard aircraft carriers there was quite a bit of drinking. I believe that in some instances that was more or less condoned. I think that the stress and the strain on those people during the war was such that they probably deserved to drink. It was very very nerve-wracking for them. In most ships, however, I think it was like my ship. I told my officers that I didn't condone liquor aboard ship. I said I would never conduct any searches but if they were ever caught drinking or in the event of any incident that was due to their drinking aboard ship that I'd be right at the head of the prosecution line, they'd swing for it, and I wouldn't defend them. I never had any trouble with drinking aboard ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

After your stay in New York you reported to the WASHINGTON. Was that in the summer in 1941?

Edward G. Miller:

Yes. I think that was about April or May of 1941. Frank Sanger and I went down to Philadelphia and rented an apartment because the ship wasn't ready yet. We reported to the

ship every morning at eight o'clock and were given the job of educating ourselves, as it were. We were put down in the plotting room or around the gun mounts to learn what we could. We were given the job of diagramming certain hydraulic and electric circuits just for our own education.

This time we spent on the WASHINGTON was also an excellent opportunity to get acquainted with the enlisted people in our divisions and with our other officers. My boss, my division officer, was Al Church, A. T. Church, of the Class of 1938. Stan Turner, "Whizeer" White, a fellow named Thornberry, and myself were the junior division officers. I was stationed as Al's division officer for about six or eight months.

After serving under Church, I was transferred to the second division, the turret two division, under Lieutenant Ray Hunter of the Class of 1931. Ray Hunter, incidentally, was one of our company officers in the Naval Academy, an outstanding naval officer and a good example for all of us at the Academy, unlike some of the others I've talked about. Ray was my division officer and he taught me a lot about leadership. He was a very good leader. He taught me a lot about gunnery and was outstanding in developing young officers. He didn't supervise them too closely. He gave them responsibilities and more or less let them carry them out in their own manner. He was firm but fair in all relations with his subordinates, and was respected by all of them.

My battle station was down in the fire control center where I ran the main mark seven range keeper, which was used to control the firing of the sixteen-inch guns. Howard Montgomery, my classmate, was down there with me, and Frank Sanger was over in the secondary battery plotting room. The fire control officer of the WASHINGTON was an officer named Ed Hooper. Frank Sanger will tell you more about him. He was one of the

first fire-control post-graduate students--I believe he went to M.I.T.--that the Navy ever had, and one of the Navy's most brilliant officers. He was a lieutenant then. He ultimately became a vice admiral. His final job was officer in charge of the Naval archives or Naval Historian. He was a very brilliant man. As a matter of fact, we had a lot of fine officers on the USS WASHINGTON, though the captain, H. H. J. Benson, was very ineffective. Bob Clark, the exec, was outstanding. Harvey Walsh, out of the Class of 1922, was our gunnery officer. He was our boss. He was outstanding. Here again you had a mixture of outstanding officers and mediocre officers in my opinion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Isn't it true that the CO that commissions the ship usually doesn't stay with it for very long?

Edward G. Miller:

Yes. I'm not sure how long Benson stayed with it, but in this case I think he stayed with it quite a while. I stayed with the ship from May of 1941 until the summer of 1942. I was in it a little over a year. The first year we didn't do much. We were down in the Gulf of Mexico for a while, doing a lot of training. We came back and crossed the Atlantic to join the British Home Fleet. We operated a lot out of Scapa Flow. We shadowed the convoys that went into Murmansk, Russia, because we were afraid some of the German battleships, the SCHARNHORST and the GNEISENAU, and the cruiser PRINZ EUGEN, might come out of Norwegian ports. Several of those ships had run the English Channel west to east right under the nose of the British RAF and arrived safely in Norway. Even though we could keep track of the German ships by air reconnaissance, there was a lot of fog up there. During the fog, they'd slip out to sea and we'd lose them for a little while. We were always afraid that they'd come up and attack our convoys. They did try several times but always withdrew because of our presence. The only trouble was that we'd only take our

support so far before we'd pull back because of lack of air cover. There were several convoys that ran into concentrated air attacks and wolfpacks up off the North Cape. There has been plenty of history written about those. Sixty ships would start out from Iceland and only twenty would get to Murmansk. The attrition was terrible.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the wolfpacks strike after the American convoy had dropped off?

Edward G. Miller:

No, after the protection had dropped off.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I meant.

Edward G. Miller:

Yes. That's right. We'd pull our protection back, because for one thing we couldn't spare the ships. There was always an argument as to whether our emphasis should be in the Pacific or in the Atlantic. General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz et al were screaming for ships in the Pacific. The Japanese Navy was a strong adversary. Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations, was a strong supporter of Nimitz and he wanted everything out there. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Winston Churchill wanted our forces in the Atlantic, and so there was always a tug-of-war and trade-off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the British not have the protection to come out and meet the convoy when the American protection dropped off?

Edward G. Miller:

We had a combined force, and we'd go along until there was no more danger of a battleship surface ship attack. We were not there to protect them against aircraft and submarines. In those days there was no way really to protect them against aircraft except with the relative inefficient anti-aircraft fire; and only the destroyers could protect them against submarines. Out of Scapa Flow, which is off Scotland, we had the VICTORIOUS, a British aircraft carrier; the KING GEORGE V, a British battleship, part of the time; the PUNJABI, a British cruiser; two American cruisers; the WASHINGTON; the HORNET,

part of the time; and a bunch of American and British destroyers.

We had some very bad things happen out there. We were out one time in the fog, steaming along, when we felt underwater explosions. We thought that somebody had been hit by a torpedo. In fact, the PUNJABI, in the fog, had sliced right through a British destroyer. The destroyer had steamed across the path of the PUNJABI and been hit. I was on the deck of the WASHINGTON and some of us saw these sailors in the water. At first we thought that depth charges had been dropped and these were German sailors. Then we thought, maybe they were from a sunken ship that had been hit by a torpedo. Then we found out that a destroyer had been cut in half by a cruiser and these were her men in the water. Some of their depth charges had not been set on safe, had gone off, and killed some of the men in the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

Off of Scapa Flow, they couldn't survive in the water for very long, could they?

Edward G. Miller:

No. As a matter of fact, we were north of Scapa Flow. We would go up close to the Arctic Circle, near Spitsbergen, way up off the northern coast of Norway. No, they couldn't survive, but quite a few of them were rescued.

Another thing was interesting, Don, for the sake of history. A doctor aboard our ship discovered that all the candy was disappearing out of the store. He did a study and found that it was so cold topside, where we had to spend so much time, and our diet was such, that apparently people weren't getting enough calories and sugar, and they just started buying and eating everything they could find that was sweet. The men didn't know this was happening. They just had such a craving for more sugar, subconsciously. This doctor, a very fine fellow, gave the officers a presentation about this, talked to us all as we were sitting around in the wardroom. It was a fascinating phenomena. We were up there in those

northern climates and everybody wanted his blood sugar to be increased and we needed more calories.

Anyway, we came back to New York from this North Atlantic operation and that's where I got off the ship. I'd been aboard the ship for just over a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you did not follow the WASHINGTON to the Pacific at all then?

Edward G. Miller:

No. I didn't go to the Pacific. I got off and got married. When I was at the Naval Academy, I had a blind date with a girl from Grand Island, Nebraska. Her name was Peg Donald. A fellow named Jim Steidley (he became an alcoholic and passed away a long time ago) asked me to accept a blind date with her and I did. I dated Peg all during my junior year at the Naval Academy. During my senior year, Jim Steidley, the fellow who got me the blind date, went on September leave and the two of them fell in love; and I lost my girl friend to the fellow who introduced me to her. But before that happened, I went that September to see her and while I was there, I met another girl, one of Peggy's best friends named Jean Anne Vieregg. They both went to Ogontz Junior College up in Philadelphia. Peggy's friend left Ogontz Junior College and went to Traphagen School of Design in New York City. When Frank Sanger, Marshall, Wirth, and I went up to New York City, I didn't know a girl in New York.

Donald R. Lennon:

Except for the three models that you rented your apartment from!

Edward G. Miller:

Well, we got to know quite a few while we were up there. Meanwhile, I wrote Jean Anne Vieregg a letter and said, "How about a date?" She said, "All right." I had seen her twice--once in Philadelphia and once in Grand Island, Nebraska. We started dating, and by the time I got to Philadelphia to put the ship in commission, I was catching the five or six o'clock train to New York twice a week and then returning on what they called the "milk

run." It left New York at two o'clock in the morning and arrived down in Philadelphia at five o'clock. I was catching that and getting back to the ship and going to bed for half an hour and then getting up and doing my day's work. She'd come down to Philadelphia to see me and we reached the point that when I left the WASHINGTON, we got married. It was very interesting in those days, you know, because we were supposed to wait two years before we could get married.

Donald R. Lennon:

Legally.

Edward G. Miller:

Legally. I won't say how many officers on the WASHINGTON were married. I know two were--Charlie Quinn and Rod Middleton, my roommate. The Navy was sort of a hidebound, very serious outfit then. But Rod Middleton wanted the extra money that a married officer got. We were getting $140 a month and I guess a married officer got $180. One day Rod confronted the navigator and said, "I want to tell you I'm married." The navigator said, "Submit your resignation."

Donald R. Lennon:

How long had he been out of the Academy at that time?

Edward G. Miller:

About eight months.

The navigator, whose name was Ayrault, said, "Submit your resignation."

Ayrault was a stuffed shirt.So Rod went back and wrote out a resignation that said, "I hereby resign; however, if it be the pleasure of the Navy, I will accept a commission in the Naval Reserve and continue on active duty." So they went to the Captain, H. H. J. Benson.

Captain Benson called him in and said, "Ensign Middleton, there are some people whom we expect to obey Naval regulations and you are one of them. I can't tell you how dreadfully disappointed I am in you that you got married in violation of your midshipman's

oath."

Well, Rod resigned from the regular Navy, was given a commission in the Naval Reserve, and continued in active duty. In 1946, at the end of the war, he made an application to be transferred to the regular Navy. He was transferred back to the regular Navy in his regular Navy slot. He never lost a number, never lost a promotion, never lost anything and made admiral. This is the man who disappointed the Navy by breaking Navy regulations.

Incidentally, Rod's wife's name is Ethel Middleton. You'll find her name in the roster. She's a delightful person; if you ever get a chance to talk to her, you'd enjoy it very much.

Anyway, I came back to New York and I called up my fiancee, Jean Anne Vieregg. (That's as German as you get; it comes from Vier Ecke, four corners.) Anyway, I said, "Let's get married." She said, "Fine." She went home and had about four days to get her trousseau and wedding gown and everything ready before we were married on August 1, 1942, in Grand Presbyterian Church in Grand Island, Nebraska. We had to leave the next morning for Washington, D. C., where I had orders to report to the Naval Gun Factory to study the five-inch thirty-eight caliber anti-aircraft guns. I had my orders to go aboard the destroyer CHAMPLIN.

Quarters in Washington were impossible to get. But we had a relative in Washington who called us on the telephone and said, "I have found something. It's a beautiful apartment and you can have it for one month while you are in Washington but it's very expensive! It's $65." My God, I was only making $140 a month! Sixty-five dollars! It was a brick apartment house up near the Wardman Park Hotel overlooking Rock Creek

Park and it was gorgeous! It was up on the sixth or seventh floor. I paid the full $65. It killed my to pay $65 but I had to. It didn't leave us much to eat on.

After finishing school in Washington, I was sent to another school down at Dam Neck, Virginia, which is not far from the Oceana Naval Air Station in Norfolk. There I studied twenty-millimeter and forty-millimeter guns. While I was there, I got my orders changed from the CHAMPLIN to the GHERARDI (DD637), which was being built in Philadelphia. It was the second brand new ship I went to that was built in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. The GHERARDI was commissioned about September 1942.

I stayed on the GHERARDI from 1942 to 1946 and had practically every job there was to have on her. I started out as the assistant gunnery officer and ended up as the executive officer. The captain of the GHERARDI was John Schmidt, of the Class of 1927, who was my mentor for a period of probably fifteen to eighteen months aboard that ship. Practically everything I learned about command, I learned from John Schmidt. John, like myself, had many, many commands at sea. I believe that he had four destroyers. He had learned from some of the old-timers who were really good in the old four-stacker destroyers. John was an expert pistol shot, an expert chess player, and he knew Shakespeare forward and backward. He was a very unusual man. Like me, he was a little bit "non-reg" and he never let the regulations prevent him from doing things he thought he should do. As a result, he had some letters in his record.

One of the letters in his file was generated when he went aboard a destroyer and didn't think that the visibility from the bridge was good--he didn't like the way the pilothouse was arranged. He wrote a letter to the Bureau of Ships via the Chief of Naval Operations saying that this pilothouse might make a good bawdy house but it wasn't a good

ship's bridge. The Chief of Naval Operations, Ernie King, put a letter in his record that said, "You're (it's not "reprimanded") chastised for using facetious language in official correspondence." Now can you imagine that?

Donald R. Lennon:

This is in time of war!

Edward G. Miller:

Yes! John was a great fellow. We were putting like, two destroyers a week in commission--that was over a hundred a year--and the Navy just didn't have the officers for them.

John got all of his officers in the wardroom and said, "How many of you have been to sea before?" Out of fourteen officers, five had been to sea before. Nine had never been to sea.

He said, "How many of you have ever in your life stood a deck watch?" I put up my hand and another fellow put up his hand.

He said, "Where did you stand your watch?"

I said, "I stood about five junior-officer-of-the-deck watches on a battleship." The other fellow said something similar.

Then John said, "You're qualified officers of the deck!" (In peacetime--prior to the war--it took a year to qualify as officer of the deck!)

The first time we actually backed out of the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, John said to me, "Okay Ed, you have the con."

There was the Delaware River full of ships and I'd never had the con of a ship before in my life! I said, "All right, left 10 degrees rudder."

I had had the con about three minutes when he said, "All right, I'll take the con now. Right full rudder." Then he said to me, "Didn't you see that ship coming up here?" And I

hadn't!

He got us out of trouble and then he said, "Okay, you have the con." He never said, "Come left a little; come right a little." You took it until he said, "I have to take it away from you." He kept his mouth shut! But he'd take the con and correct what you were doing wrong, and then after everything was over, he'd say, "Now let me tell you why I did that." He never stood behind you and heckled you or looked over your shoulder and said, "Don't do this and don't do that." He would let you do it until you were in extremis and then he'd take over.

On my third watch, about ten o'clock at night, he came up to the bridge where I had watch. He stayed on the bridge with me for awhile. We had a submarine with us, but we could barely see it. It had dim running lights but everything else was darkened ship. He said, "Okay, goodnight Ed, I'm going to bed." I thought, My God he's leaving me out at night alone with this submarine back there. He told me what to do and, I don't know, but sometimes I'd think maybe he stood on the back of the bridge for the next hour to see how I was doing. I never looked. He did this with every officer that came aboard that ship. He put them out there and after a month or two months of getting acclimated, he'd make or break them. If an officer didn't have the ability to qualify, he was sent ashore.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm sure he was watching very carefully.

Edward G. Miller:

He was so capable. And I emulated him when I got a ship. When we fueled ship or replenished ship or made landings, I'd break in my exec first and then I'd let my other officers do it. Sometimes we'd be alongside a replenishment ship and if I had confidence in the kid, I'd go around the ship and see if all the safety practices were being enforced, and these youngsters would be shocked when I'd leave the bridge.

At the same time, in the few instances that I got in a little bit of difficulty, my seniors always were understanding. As a good example, I had command of the POWELL, DER 213, which was a C.I.C. training ship out of Boston, Massachusetts. We operated out of the South Boston Yard. The C.I.C. school was in the Fargo Building, which housed the First Naval District Headquarters. We took students out every morning and brought them back every night. We did this five days a week except in inclement weather--real real bad fog or snow. I let all my officers make the landings. One night the officer was coming in a little fast. I took it away from him and said, "All back, full." But by that time it was too late. I had a little something protruding out of the side of the ship that hit a transformer on the dock and everything started flashing and making sparks, and all the power went out on the South Boston Navy Yard. I'd shorted out the whole electrical system by hitting that transformer. It probably cost fifteen or twenty-five thousand dollars in repairs and lost work.

I went up and talked to the supervisor in the yard and he said, "Okay buddy, you have to make a report of this." I did. It was forwarded to my destroyer division commander. I stated that "I accepted the full responsibility. I believed in training officers, however, and these things were going to happen once in a while." I didn't even mention the name of the officer who had the con; it was not his fault. It was my fault. The commanding officer is always at fault when something happens. My division commander said, "I agree with you." And that was the end of that.

In other words, we had many good officers. I had good officers that I worked for. They understood those things. The whole point is that this country was putting two destroyers a week into commission, and John Schmidt was responsible for training people

who could move on to a destroyer and take a responsible position. If they had given him fourteen officers and he turned out no qualified officers of the deck, he would not have been doing his job. John did a great job, and he also had a good sense of humor.

We got assigned to the North Atlantic Convoy Route for two years, and that was the hardest part of the war for me as well as for many others. On one of those trips over and back, I lost eighteen pounds. I've been on trips where all the way over we maybe ate two or three meals sitting down. I came out of North Africa through the Straits of Gibraltar and hit a storm, and we didn't realize how bad it was outside the straits. The table was set for dinner when we took one gigantic roll and every dish in the wardroom was smashed. That was life aboard a destroyer or DE in those days.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these problems due to the weather or to the Germans?

Edward G. Miller:

No, no, the weather. As a matter of fact, when you were in convoy duty, there were two things that made you happy; one, a big, big storm with high waves, and two, a dark moonless night. When we were in a big storm, we couldn't eat, we couldn't sleep, but the enemy submarines couldn't come to the surface or they'd broach. Then on dark, dark nights, with no moon, the submarines could hear us all right, but they couldn't see us. Some nights--clear, clear nights with a full moon--were like being out there in the daylight. You could see the whole convoy. You could see everybody. We always hated clear nights; but we always loved dark nights and heavy seas. Fog was very bad in the North Atlantic, especially from Boston to Iceland and Greenland.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is what I was getting ready to ask. Were most of your convoys on the Northern Route?

Edward G. Miller:

I only made one Southern Route convoy and that was in to Casablanca when the

invasion of North Africa took place. That's the only one. Every other one of mine went into Londonderry, Belfast, and Swansea, Wales. We went down the Irish Sea to Swansea and that's the only place I took convoys.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these troop convoys or equipment convoys?

Edward G. Miller:

Most of these were equipment convoys. I made one fast convoy with troops. But as we got more and more good ships out there like QUEEN MARY--QUEEN ELIZABETH-type ships--they went singly because they could steam at twenty-five knots and zigzag. At twenty-five knots, our sonar gear wasn't effective. In fact, our sonar gear in those days wasn't effective over fifteen knots.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were just trying to keep up with them.

Edward G. Miller:

They'd send them independently and they never lost one of those ships. There were a lot of innovations during those days. First, was the searchlight sonar where you actually could train the sonar by 10-degree increments through a large arc (initially I believe it was 240 degrees) and send the signal out and get a returning echo. That searchlight sonar came in pretty close to the beginning of World War II. The British invented the Asdic and we had what we called the searchlight sonar. That was all brand new.

The second new thing that we hadn't done before was replenishment at sea. Before the war, replenishment at sea was a rarity. But during WWII, replenishment at sea was necessary: first, to effectively carry out convoy work, i.e. fuel the escorts, and second, to operate over broad reaches of ocean, such as the Pacific. We'd done a lot of operating in the Pacific but it had always been out of a base at Manila, a base at Pearl Harbor, a base at Guam, or a base at Wake. In WWII, at least in the early days, when we left Pearl Harbor, we had no bases between Pearl Harbor and Australia; we had to replenish at sea. We set up

replenishment depots on islands or in atolls as we advanced. Some of them were pretty rudimentary to begin with. We'd take an old LST, for example, and use it to store five-inch shells. Lord, during normal peacetime operations you would never think of storing ammunition under conditions other than those where you could control the humidity and the temperature and where you would have all sorts of safety precautions concerning accessibility. Out there, we stored ammunition under relatively unsafe, unstable conditions. As a result, the projectiles or shells would get rusty. I've never seen so much rust on a five-inch shell.

The other thing that we had to get used to was signaling by various methods. We had gone to blinker signaling prior to World War II. But during World War II, we couldn't use blinkers at night until infrared was introduced. This changed our communications more than ever before. Voice communications took a step forward during World War II. We had to cut down the use of radio. We had to limit the use of any equipment that would produce a signal that could be intercepted by the enemy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Radar made tremendous strides.

Edward G. Miller:

Radar, oh my God, was tremendous. Yes! Well there were several effects of all this. First, let's take radar. The tops of masts on ships that were built during peacetime weren't meant to support a radar platform. The designers, in providing for the stability of the ships, didn't figure on forty-millimeter gun mounts, twenty-millimeter gun mounts, and other WW II additions. Hence, as you put more and more equipment on the upper deck of the destroyer, you raised the center of gravity and the ship became very, very unstable. I don't think we have any history of ships capsizing--maybe one or two during typhoons--but you went without sleep and you were sometimes concerned because of the terrible roll of

the ship with all that topside weight.

The other thing that amused me was that during peacetime it used to take officers so long to qualify for certain things--for command, for the job of gunnery officer, for engineering officer. But during wartime, we got promoted very quickly. We would be put into these jobs and the older officers would shake their heads and say, "How can these young fellows do this?" I hope the younger generation is more understanding than the generation before us. We learned that youth can do far more than it is ever permitted to do if it's given the challenge of doing it. We had one young officer aboard our ship by the name of Fitz. He was a Princeton engineering graduate and the most useless character in the world. He must have come from a "spoiled-brat" home. The old engineering officer couldn't stand the kid. Well, one day the engineering officer got transferred away, the assistant engineering officer got transferred away, and Mr. Fitz was suddenly our engineering officer. You know, in the next year, I watched that man grow twenty years in maturity. Once he was given the responsibility and had to do the job, he just matured overnight. He became an outstanding Naval officer.

My daughter-in-law said, "You know, a young man said to me that World War II represented the best years of his life. How could he say that? I hate war! How could he say they were the best years of his life?" Well, let me tell you another sea story concerning this observation. When I left the Navy, I became a consultant and was conducting a fund-raising campaign for Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. I couldn't get anyone to accept the chairmanship of this campaign until, finally, Bob Upton accepted it. Bob Upton was the group vice president of Whirlpool Corporation, responsible for dealing with Sears Roebuck on all the Coldspot refrigerators and washers. (They make all those

appliances for Sears Roebuck.) His father built the first Whirlpool washing machine in his garage, and with Bob's Uncle Fred, made Whirlpool Corporation what it is today.

Well, Bob Upton called me up and said, "Mr. Miller, I've decided to take the chairmanship. The president of the college, President Hamill, told me that you are the director of the campaign. When can you and I get together?"

I said, "Let's get together at breakfast tomorrow morning."

He said, "Fine. Meet me at (such and such a place) in Benton Harbor at 7:30."

I said, "I'll be there."

So the next morning I met him at Benton Harbor. I went in and sat down and he asked, "How long have you been at this?"

I said, "Oh, just about two years."

He said, "What did you do before this?"

I said, "I was in the Navy."

He said, "What were you?"

I said, "A captain."

He said, "Oh, let me tell you something. During World War II, you know what I was?"

I said, "What were you?"

He said, "I was a supply officer on a LST for two-and-a-half years, and those were the best years of my life."

Here was a kid, born with a silver spoon in his mouth, worth millions! He and his mother owned more stock between them than anyone else in the Whirlpool Corporation. He had been sent to the University of Chicago where he earned a business degree. But the

whole point was that everything he did was as his father's son. And suddenly he was thrown aboard an LST and was told, "You're the disbursing officer. You're the supply officer. You're the mess officer. You've got to feed everybody. You have to do all these things and nobody is sponsoring you. This is your job." And he said, "Those were the best years of my life."

I think this is what they Navy does for each of us. This is why we aspire to command. This is why we aspire to take the ship out in the middle of the ocean away from everybody where they can't get hold of us and do it on our own. I think it's a maturing process.

Going back to John Schmidt and the GHERARDI. . . . We ran about seven or eight convoys to Ireland and Swansea, Wales, primarily. The sad thing about that is that my grandfather on my mother's side came from Swansea, Wales, and I didn't know it when I was over there. When I told my mother, two or three years later, that I'd been to Swansea, she said, "That's where your grandfather came from." I've always wanted to go back there but I never have. At the end of John Schmidt's tour, an officer named Neale Curtin, Class of 1928, took over. (He's still alive in Philadelphia.) Then he was relieved by Bill Gentry, Class of 1939.

By the time Schmidt left the ship, we'd finished all the convoy duty and had become involved in the invasions. The first one I was involved in was the invasion of Sicily, in June of 1943. We were off Gela as a gunfire-support ship. Since then I've met a number of Army officers who were on the beach at Gela. We put our first troops on the beach with no heavy artillery or armor. About sixteen Tiger Tanks came out of the woods, down toward the beaches, with guns blazing. The radio started screaming for fire support. We had two

cruisers and about four destroyers, and when we looked out and saw those tanks coming down across the field towards our troops, we opened fire. The cruisers actually damaged the tanks. All I had was fragmenting ammunition, so I think we were shooting frags. If there had been any troops exposed, they would have been killed, but I don't think we could have damaged the armor of a tank. The gunfire plus the cruiser's armor-piercing six-inch projectiles stopped those Tiger tanks and turned them back into the woods.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had not softened the area before the landing?

Edward G. Miller:

In those days we didn't soften up the way we did later. First, we didn't have the air power to do it. We did have the fire support but we had missed the tanks. The next thing that happened that night was that several JU-88 Junkers and a Stuka came over and the MADDOX, which was in our division and was behind us, was hit and went down in thirty seconds. A good friend named Ray Laird, Class of 1939, was a gunnery officer on the MADDOX. He was saved. About an hour later, a Stuka came down right at our ship. One of our twenty-millimeter gunners was one of the first persons to see him. (Our air-search radar in the presence of land in those days was very ineffective). He opened up with his twenty-millimeter gun and hit him! He was a mess hall cook named McCauly. I'll never forget him. He served food in the mess hall and was a gunner on one of the twenty-millimeter guns. This plane came right down in his path and McCauly fired and shot him down within fifty yards of the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yours was not one of the destroyers that could not elevate their guns was it?

Edward G. Miller:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

Some of them had a problem. They didn't have any weapons against aircraft.

Edward G. Miller:

No. We didn't have any problems. We had good five-inch .38s.

Donald R. Lennon:

In these invasions, you had no air support, no carriers, or battleships, or anything--just destroyers and cruisers?

Edward G. Miller:

That is correct. The next thing that happened--this was a terrible thing--was that a group of planes came over in formation and we all fired on them before we discovered that they were our returning parachute-drop aircraft. I think they were B-25s. The navigation of the B-25 paratroop planes was horrible. They dropped their troops in the wrong places and then they came back over the invading Fleet formation. I'm afraid to say how many B-25s we shot down--Morrison has some figures on this--but we shot down a bunch. We had to cease fire because the ships were actually hitting each other.

The beach was stabilized within a day or two and then all of the destroyers were sent on anti-submarine work, because the Germans had some submarines there. We went back, I think, to Oran and had just replenished--gotten some supplies from the Army--and turned around to come back when we were sent up to Palermo. The BUCK, the SHUBRICK, the GHERARDI, and later the MAYRANT were sent up to Palermo to support Patton. The BUCK and GHERARDI were sent up the coast every night from Palermo to Messina--a distance of about sixty miles--and about every three or four miles we'd fire. This was harassing fire.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just fire at random?

Edward G. Miller:

Fire at random at the road or at the villages along the road, because they were all heavily populated by Germans. That was where the opposition to Patton came from. On the third night, before we left on our patrol, we were told that the Germans were ferrying land mines in small LST-type ships--lighters--into the villages along the coast, between Palermo and Messina. They were not, however, getting any closer to Palermo than fifteen

or twenty miles. They were bringing in these land mines at night and mining the roads. We went out that night, the GHERARDI and the BUCK (by that time we had a very very good surface-search radar [SG radar]), and shortly before midnight, we picked up three targets on the radar. The captain said, "Illuminate." So I fired some starshells and there was a lighter accompanied by two E-boats. The E-boats were like PT Boats. He said, "Commence firing." I opened fire at the lighter, and about the second salvo, we hit her. It must have been full of mines because it made the biggest explosion I've ever seen in my life. With that, one of the E-boats came toward us, (the radar told us this) and the bridge lookout and the captain saw a torpedo pass just ahead of our ship. Meanwhile the BUCK had opened fire on the other E-boat and hit her. The one that came out at us just disappeared in the smoke and debris and got away. But we sank one lighter and one E-boat that night.

We went back and I was so darn tired. I had been up two nights in a row and all day long (about 32 hours in all), so the captain said, "You go down and get some sleep." I went down to get some sleep, but no sooner had I gotten to sleep than General Quarters sounded. I went up and discovered that two German planes had come in over the hill and dropped some bombs at us and the SHUBRICK, hitting the stern of the SHUBRICK. Lou Bryan, who later became an admiral, was commander of the SHUBRICK, and my good friend and classmate, Frank Price, who later became vice admiral, was the gunnery officer. They got the ship alongside the dock in Palermo and patched her up. (She was able to get underway under her own power and get down to Malta. They had a tug go along with her. At Malta, the British fixed her up.)

With all this shooting, I'd run out of flashless powder. Flashless powder was to us the greatest invention since the wheel, because it enabled us to fire at night with so little

flash. I had no flashless powder left and I didn't want to make those night raids using powder whose flash would reveal our location. So I said to Frank, "How about giving me some of your flashless powder?"

Frank said, "Well, let's talk to the captain."

Lou said, "I know what you're up against Lieutenant Miller. I'll tell you what I'll do. I'll give you all you can put in that boat there but the rest I'd like to keep until I see what kind of duty we get."

I said, "Okay."

So here we were--here again this is in violation of regulation--putting powder in a motor whaleboat in cans with no covering and the sun beating down on it. I took my motor whaleboat full of powder back to my ship.

The next day, the MAYRANT got hit. I don't think she got hit badly. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr., was aboard her and he got a Navy Cross or some kind of medal. He was subjected to a lot of criticism because he was the President's son and was given a medal. But from what I understand, he was a very, very fine officer and had done a good job on the MAYRANT and deserved the medal.

From there, we went back to running a couple more convoys, and then of course, Normandy came.

Donald R. Lennon:

One question at this point: How was the coordination between the Navy and the Army in the Italian campaign? Were things pretty well coordinated between the branches of service?

Edward G. Miller:

Pretty good, yes. I think, actually, the Navy and the Army in amphibious operations have always worked pretty well together.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was the Navy taking orders from? Was it Patton or was there an admiral there that was coordinating this?

Edward G. Miller:

In those days it was still done on a cooperative basis.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sometimes when you are dealing with, say, prima donnas like Patton, they can be very difficult to cooperate with.

Edward G. Miller:

The Navy has never been willing to give up its sovereignty over its forces to the extent that the Army has. The Air Force, of course, took a chapter out of the Navy's book, and, as a result, they can't get along with the Army. If you want to know the truth, I think the Navy has been the worst offender in refusing to meld forces--combine forces. As long as the Navy and the Marines are working together, it's very clear cut and very nice. A Naval commander is in charge until a Marine commander has established his headquarters ashore--has taken command, is all set up, and ready to control all his troops. The Naval officer has to be in command of the landing itself because he just knows more about the condition of the tides, the winds, the capability of the fire-support ships, and the capability of the landing craft. The Army knows something about it, but not like the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was wondering about the decision-making process.

Edward G. Miller:

From my viewpoint and historical perspective, the effectiveness of the "softening-up" process has been exaggerated. If you ever go to Omaha Beach, you are going to see the encasements where the Germans had their big guns. Two weeks before the softening-up process, the Germans moved some of those big guns from one place to another, so we didn't know where they were on D-Day. You are also going to see places that went relatively unscathed.

The Japanese found after the first or second invasion that palmetto logs would

defeat most of the stuff the ships could throw at them. They would just bury themselves in. At Okinawa they did it. We shot everything around Naha, Okinawa, but they were in the caves to the south of Naha, so we didn't have any effect on them at all. At Palermo, at Gela, and to some extent, at Normandy, I think all the bombardment by aircraft and ships did some good, but we were inclined to exaggerate just how much good. That's my opinion. When I left the GHERARDI in Okinawa, I got a briefing by an officer who had been on the island and I just don't think it accomplished that much physically. However, it probably had a psychological effect--positive on the attackers--negative on the defenders.

I think the best thing we could do when we go into a place is to hit the oil dumps; that has an effect. Also, if you can hit the ammunition dumps, that has an effect. If you can rip the railroad yards to pieces, that has an effect. It's the destruction of logistical support that hurts--not hitting the guns and the men. As you know, in Germany, we finally got wise and started hitting the ball-bearing plants. We hit the Ploesti oil field installations. That's where wars are won or lost. The Japanese still had plenty of men in the islands, but when we cut off their oil supplies, they were stuck. We were getting pretty good interdiction from our submarines by the end of the war.

In answer to your question, I think our gunfire support at Gela helped make it successful, because I don't think the Germans knew exactly where we were coming in. I would suspect that if I had been defending the island, I would have gone around Montgomery's side near Syracuse and Mt. Vesuvius, south of Messina, near the Strait of Messina. I would have suspected that maybe that would have been where you would have come in, rather than on the western side.

Donald R. Lennon:

Maybe that's why they didn't come in there.

Edward G. Miller:

Well, you know Montgomery had pretty stiff resistance over there. Montgomery landed on the east side and Patton landed on the west side. Then they had a race for Messina. Montgomery only had half as far to go as Patton, but that was when Patton was ruthless. Did you ever see that movie called, Patton? I think that was all true, his slapping the soldier and going along saying, "By God, if you don't get these tanks through here, I'll get somebody who can."

From there, my ship went back to convoy duty. Two convoys later, I went to the invasion of Normandy where we were in gunfire support. One of the ships of our group, the USS CORRY, was sunk and we went and took her place early. I was the exec and was in the combat information center, directing supporting fire by sending the data up to the gunnery officer. Two weeks before the invasion, we went to Slapton Sands, an extended beach area where the British practiced amphibious landings and gunfire support. We had an Army officer who was our gunfire support liaison officer and we worked out together. First he came and had breakfast with us. We later shot with him all morning. Then he came and had lunch with us, and said, "We'll see you on D-Day." We went in on D-Day, and he called us; we fired two missions and he went off the line. And that's the last we heard of him. We found out later that he had been killed. So we were put with another group on the line and stayed in there for, I guess, four days. Then we were sent back to England to refuel and pick up mail.

Two funny things happened to us during the four days we were off the Normandy beaches. The first one happened on the second day. A Spitfire was circling and was in trouble. The pilot abandoned the Spitfire and parachuted in the water. He landed just fifty feet away from our ship and we picked him up. For the next two days, that man was so

nervous that we could hardly control him. He couldn't eat.

I asked him, "What are you so nervous about?"

He said, "It is dangerous being on this ship."

I said, "What do mean it's dangerous?"

He said, "There are a lot of submarines out there. They'll sink us."

I said, "Man, you've just been up in that Spitfire and somebody shot you out of the air!"

He said, "Yeah, but you're safe up there."

You talk about why some people are aviators and some people submariners and some people surface sailors. This man could not wait to get off our ship. He was so frightened. He was so afraid a submarine was going to sink us.

The second humourous thing involved our chief engineer. His name was McKenzie and he had a burr so thick you could cut it. He guarded his water supply very jealously. Of course, we had to, because water aboard ship was a tight commodity. Anyway, a PT boat came alongside and her skipper said, "Can I have some water?"

I said, "Sure."

Mac McKenzie was standing there and he said, "Listen, Commander, we can't give that man water. I don't have enough for myself."

I said, "Mac, you have plenty of water."

He said, "I'm going to see the captain."

He went up to the captain and I went with him.

He said, "Commander Miller here wants to give this ship that just came alongside some water."

I said, "Well, here's a skipper and he needs water. He's out there in this little boat."

I said to the PT skipper, "How much water do you hold?"

He said, "Forty gallons."

Mac said, "Oh well, I guess I can give him some water."

McKenzie thought the guy was going to take five thousand gallons. And the captain and I roared at him. He became very magnanimous all of a sudden because the skipper wanted only forty gallons of water for his little boat. I think he only had four men aboard that little PT boat. He had brought us our mail, and, of course, we always gave them ice cream. That was a big treat for them.

On June twenty-fifth, after we had done ASW duty, we were sent up to Cherbourg, [France], for fire support. There were two cruisers and four destroyers and we were sent up there because the Army was closing in on Cherbourg and they needed us to give them some fire support, especially on some truck parks and rail terminals. So we went up there and went in to about eight miles--about sixteen thousand yards. Our skipper was Neal Curtin, and I said to him "Captain, our effective range is about twelve or fourteen thousand at the most." (The maximum range was nineteen thousand.)

So the captain said, "Yeah, I think we had better move in."

So we moved in to about six miles (twelve thousand yards). We started opening fire. All of a sudden, the sea around us just exploded with twelve- and fourteen-inch shells; those Germans had us zeroed in. That's the closest I came to getting killed during the war. Out there, say in a space of the next three minutes, thirty or forty shells landed within twenty yards of that ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Cherbourg was very heavily defended.

Edward G. Miller:

None of them hit us. The admiral screamed over voice radio, "Get the hell out of there! Get the hell out of there!" And we did. We burned it. The cruisers had a longer effective range and I guess they were just out of the range of the shore batteries. A week later the U.S. Army took Cherbourg and we furnished fire support for the PT boats that surveyed the harbor. About the thirtieth of June, we secured from our Normandy duties and went back to convoying.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were able to stand off Cherbourg and fire.

Edward G. Miller:

No. The cruisers did. We got out of the shore batteries' range and didn't do anymore firing. The destroyers didn't do anymore firing after our experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now on the Normandy Invasion, how much before D-Day did you move in as part of the invasion force?

Edward G. Miller:

I'd say two weeks.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know they were doing a lot of practicing and everything weeks ahead of time. Were you involved in that or did you just move in in time to participate?

Edward G. Miller:

No. We didn't have much time. Here's what happened as I remember it. We brought a convoy to Londonderry. I remember, because the pilot who came aboard to take us up to Londonderry was drunk. He came aboard the ship and said, "All engines ahead full."

I said to the captain, "I think this guy's drunk."

The captain started talking to him and then said, "I want you to go down below and go to bed." He said to me, "You get him down below and I'm going to anchor."

So I took the pilot below and put him to bed. He slept about two hours and when he got up I started pumping hot coffee into him. He came on the bridge and the captain read him the Riot Act.

After we got to Londonderry, we refueled and took off again. We went down the Irish Sea in a big rain storm. Then we went down to Plymouth, England, and that's where we did our practice shore bombardment. Then we went back to Belfast for about a week.

(While I was in Belfast on an earlier convoy, I had a very funny experience. The captain and some of the officers found out where the WRENS were. The WRENS (Women's Royal Naval Service) were like our WAVES. They were in an old castle right there in Belfast. About six officers went up to the castle one night to see them. They then decided to bring the girls to the ship. Well, the rule was that no British personnel were allowed to enter the shipyard after ten o'clock. The captain and another officer had two jeeps--I think they had one British vehicle--and they "ran" the gate. They drove right by the guards and down to the ship. I had the duty and was on deck when they arrived.

The captain said, "We're taking these girls in and we're going to get them some scrambled eggs. Get a cook. We're going to give them breakfast."

This was about two o'clock in the morning. Well, I'd no sooner returned to the deck, when along came some very irate bobbies.

They said, "Have you got some British personnel aboard this ship?"

I said, "Well, the Captain brought some guests aboard." They said they had seen some young ladies, some WRENS, and they, the bobbies, were coming aboard to get them.

I said, "Wait a minute. This is United States territory. You can't come aboard this ship without permission."

These men were ranting and raving about what they were going to do and I said to my messenger, "Get these gentlemen a cup of coffee." When the coffee arrived, I said, "You can come aboard the ship. Come on. Have a cup of coffee."

Meanwhile, I said to the messenger, "Go up to my cabin and get three cartons of cigarettes." (They loved American cigarettes. They couldn't get cigarettes, you know.)

So I said, "Now listen, I'm not going to bribe you but you understand we've been at sea a long time. These ladies are not being harmed. There's nothing wrong going on here; we're just giving them some breakfast and so forth. I know you're not going to report this. After all, we're in this war together."

They said, "All right, governor, all right." They took their cartons of cigarettes and left.)

I guess about three days later we got the word to start down toward the Channel. There was a long string of ships--mixed military and merchant. We weren't with any particular group at that point. We were all moving along at the same speed. We had a designation but we weren't convoying. We had gotten all the way down to Land's End when we got the word to turn around because it was postponed for twenty-four hours because of the weather. We steamed all the way back up the Irish Sea, for about twelve hours, then we turned around and steamed down the Irish Sea, went over to the PORTLAND BILL, and started across the English Channel. Previously, we had done one rehearsal, but we didn't know who we were going to go with. I don't think really you could say we were with a group. We were on the western flank--anti-submarine protection. We didn't do much of the pre H-hour bombardment. Some of the heavier ships did that. We got in at just about H-hour and started our bombardment.

Donald R. Lennon:

In a massive invasion like that, I am amazed at the logistics of the chain of command in ordering what ship to do what.

Edward G. Miller:

Not only that! You know in those days, before the days of modern communications, we were not capable of decoding classified information very fast. We have secure and rapid methods now compared to what we had then. In those days we had to either use a strip cipher, which changed daily, or we had to use our decoding machine, which was still very new. Considering that we had to get those messages out, get them decoded, and get them obeyed, it went pretty fast. The Navy had a communications system known as the "Fox System." This was a general fleet broadcast that put on all the unclassified fleet messages and you just had to pick off your message.

After Normandy, we came back and went around to the invasion of Southern France. Our total role there was anti-submarine warfare; we didn't do any bombardment. In fact, there wasn't much bombardment down there, just a little bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there submarines in the area?

Edward G. Miller:

There were submarines in the Mediterranean, but not many.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just precautionary. . . .

Edward G. Miller:

The Germans were starting to lose submarines and most of the ones they had left were in the North Atlantic. It was just precautionary. There were some in there probably. Also, the air threat was going down. What air capability they had they were using to try to slow Russia down (by this time the Russian advance had really started full scale) and to try to hold Patton and Montgomery from advancing to the east.

Donald R. Lennon:

At this time they were beginning to feel the fuel crunch just a little bit.

Edward G. Miller:

Oh you bet they were. That's right!

[End of Part 1]

| Edward G. Miller, USN (Ret.) | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| May 11, 1988 | |

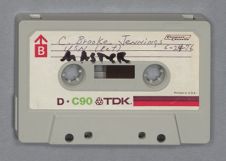

| Interview #2 |

Edward G. Miller:

After the Invasion of Normandy, the GHERARDI went back to New York Naval Shipyard. We hadn't been in a shipyard for some time and we had a two-week period of overhaul for the ship and recreation for the crew. After our overhaul we took off with our final convoy in the war in the Atlantic. We went to the Mediterranean to Oran, where we dropped our original convoy and picked up another one consisting mostly of British ships, and took that on to Alexandria, Egypt. This followed the isolation of Crete and Greece by the Allies and was almost at the end of Rommel's campaign. When Montgomery defeated him, he drew out from Cape Bon across the Straits of Sicily and back to Italy. We bypassed Cape Bon and went on out with no German air anywhere in evidence until we got to Alexandria, Egypt. We dropped our convoy in Alexandria and stayed there five days, during which time the Germans came over every night from Greece. It was a last ditch effort to delay the British from taking control of the entire eastern end of the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were they flying, heavy bombers?

Edward G. Miller:

They were flying Fokkers. They may have had some Stukas, although I don't know whether they had the range to make that. But, yes, theywere flying heavy bombers. We would hear the raid and darken ship, and then everybody would start shooting. When I say air raids, I'm talking about maybe a half a dozen planes. They were very small raids.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were just about out of fuel by this time, were they not?

Edward G. Miller:

Yes. These were nuisance raids. They would shoot and they would drop a few bombs, then turn around and go back. The damage was minimal. I think they were just trying to harrass the British, hoping to delay them from annihilating all the Germans that were in Africa. I guess they succeeded in part because many of the Germans escaped across the straits.

We had not yet taken control of the air. The British never lost control of Malta or the airfield at Malta, but at the same time, they were never able to have a sufficient force on there to give real support to the Allies in the central Mediterranean. Their forces were mostly defensive. They never supported or provided CAP for the invasion of Sicily or southern France.

After five days, we left Alexandria and brought a bunch of empties back to Gilbraltar and then returned to Oran. There was a funny incident that took place during this period that I should inject here.

Just prior to our going to Alexandria, Egypt, while we were still in Oran, we located some wine and went to the beach on a picnic. Half the crew went first, and they got drunk and came back. Then about two hours later, all the sober ones went and got drunk. The next day, the crew and officers were in pretty bad shape. We left to pick up the British convoy and take it to Alexandria. While we were on our way to meet the convoy, a message came in, but apparently it was mislaid in the communications center. (It wasn't because of the drinking that it was misplaced.) The message provided that we should go to Gibraltar and pick up some ships and convoy them to England, in which case, we would have gone back to New York. But it was about thirty-six hours before we got this message decoded and acknowledged it. By that time, we were well on our way to Alexandria. We

were one day out. The captain sent the commodore of the convoy a message advising him of the mislaid message. The commodore sent a message to the commander in chief, or whoever was in charge of the convoy routing at that time, and he said, "As long as you started out with a convoy at Alexandria, you should stay with that convoy." It didn't make much difference except that we might have had another trip back to the United States, so everybody was very disappointed.

We then participated in the invasion of southern France. This took place in the area of Cannes and St. Tropez, just west of the French Riviera. The GHERARDI was an anti-submarine warfare ship and all we did was patrol off the landing area to prevent any submarines from entering. There was no submarine activity at all during this period. Resistance was minimal. We were never called on for shore-fire support. It was a picnic.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was wondering how many subs the Germans still had at this point in the war?

Edward G. Miller:

That's a good question. I don't know how many subs they had but at this point they had a new weapon. It was called the lut torpedo. This was a pattern-runner. Maybe you have heard about it. It went out and ran a closed "X" pattern. It would go out one leg of the "X," then it would go across the top of the "X" and then down and make the other leg of the "X," and then down across the bottom leg of the "X." It would keep running like this until it ran out of gas or until it found a target. These were called lut torpedoes and they were the first German pattern-runners. Fortunately, they didn't come along until about the time of the southern France invasion. We knew about them at the time and we were always frightened that they would get loose in our convoy, but none of them ever did. They did get loose in the convoys in the Atlantic.

Many of the torpedoes had an acoustic warhead (even the pattern-runners) and when

they received a signal from a propeller they would head for it. To defend ourselves, we started pulling what we called "foxer" (FXR) gear. This FXR gear was made up of two links of one-inch pipe welded perhaps an inch apart, put on a bridle, and pulled behind the ship. When the water went between the two pieces of pipe, it caused increasing and decreasing pressure patterns that caused the pipe to "chatter." The two pipes would hit and this made a noise louder than the ship's propellers. It was pretty successful in that a number of torpedoes actually exploded in the wakes of ships on the FXR gear and not on the ship itself. We had to tow these things all the time we were at sea during the last two convoys.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a frame are you talking about?

Edward G. Miller:

I'm talking about a very small frame. Maybe eight feet long.

Donald R. Lennon:

If a torpedo exploded eight feet away from the ship, then it would do only minimal damage to the ship?

Edward G. Miller:

No. These were towed maybe fifty yards behind the ship on a large cable. At the end of the cable was a big yoke.

Donald R. Lennon: