| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

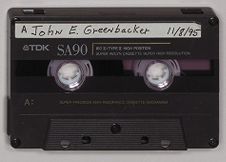

| Capt. John E. Greenbacker | |

| USNA Class of 1940 (DECO) | |

| November 8, 1995 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Captain, I'd like to begin with your background in Connecticut, what led you to want to become a Naval officer and go to the Naval Academy and something about your early background in education.

John E. Greenbacker:

You want me to go ahead and start with that?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, sir.

John E. Greenbacker:

I grew up on a diary farm in Connecticut. My father always thought that his son was going to stay there on the farm, but I was determined to go to the Naval Academy from the time I was in seventh grade and my friends in Junior High School used to refer to me as “Annapolis.” I can't remember what it was that led me to that. I've always had this yearning to sail off to high adventure. As a matter of fact, when we used to go into town at noon hour, I would go down to the train station and watch the trains come in. That was like an adventure to me also, but I did not, like people in the south, get an opportunity to get an appointment to the Academy, because they required competitive exams up there, whereas all my friends in the south, if they flunked out, they'd just go see

the Congressman and he'd appoint them. There was a sort of favoritism if you came from the right family. We didn't have that up in Connecticut. The man that became the U.S. Senator, Mallony was the mayor and he gave me a third alternate appointment when I was still in high school. That enabled me to take the entrance exam, so then after that, in order to be sure of getting in all I had to do was to get an appointment. I went a year to what is now the University of Connecticut--was then, Connecticut State--and during that year, I took competitive exams from the U.S. Senator and then from the Congressman who was from New Haven. These were all democrats. My father was a Republican, but they went along with the results and I got a first alternate appointment from the U.S. Senator and a principal appointment from the Congressman.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where you were located, in Connecticut, was not close enough to Long Island Sound for you to have grown up sailing?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. I had never had a thing and I tell people that the only Naval vessel that I saw before I entered the Naval Academy was the USS CONSTITUTION which came to New London back in the thirties when they had a tour all the way around the country. That was my association with the afloat Navy, so I really have no idea how it was that I wanted to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know a lot of DE officers that were not Academy graduates, were reserve officers, came from the Long Island Sound area there.

John E. Greenbacker:

Indeed, there were an awful lot of them that were active in yachting and as a matter of fact, we used to have our reunions up in New York, because so many of them were there on Wallstreet. When the former Secretary of the Navy, one of the skippers, after he became the executive secretary of defense, we used to make arrangements with

the Navy and get a day at sea, so we always had a big ______. He's the one that was head of Amtrak who's now dead.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh yes, I knew him. When you arrived at the Academy in 1936, tell us a little bit about that, what your first experience with the Academy was. Was it what you had anticipated it would be?

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, I had no problem with it at all. I went in there on the first day. On those days, they used to take them and give them their physical exam. They don't do this anymore. You go elsewhere and get your physical exam. So it took them all summer long to get their class in final shape, but I went in there, because I already passed the entrance exam, they signed me up to go there on the eleventh of June. In fact, it was early enough, that I didn't even take many of my final exams from my first year up at Connecticut. It was the first time I had been south of New York. There was a little local train that went from Baltimore to Annapolis and I got a taxi and it wasn't very far, but he started from 25 cents and that's what I gave him. The drilling(?) at the Naval Academy didn't bother me. As a matter of fact, life was a lot easier than it was on the farm. On a dairy farm, you have to leave whatever you're doing on Sunday afternoon and do the milking.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were accustomed to getting up early, too, for the same reason I presume.

John E. Greenbacker:

After the first year, we had a midshipmen cruise and went through the Keyhoe(?) Canal in Germany and that was very enjoyable. This was on the Battleship WYOMING which was built in 1913. Then the second summer was the destroyer summer and the third summer, was again a cruise, but we were scheduled to go into the Mediterranean, but the war was starting in 1939. So, we went to Canada instead.

Donald R. Lennon:

You lost out on that as far as a major adventure is concerned.

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, after World War II where I did all my sea duty on the East Coast and went to the sixth fleet, so I think the Mediterranean is a lot more interesting. There were far apart places out in the far east.

Donald R. Lennon:

The coursework at the Academy is quite different from how is taught at Connecticut state is it not?

John E. Greenbacker:

The system there was quite different than what it is now. Everybody took the same courses, except for foreign language. You could take Spanish, Italian, German, or French. That's one way that was different, but it was all the same thing. Most of the instructors were officers. We used to make the joke that if they failed their math course at the Naval Academy, they sent them back to learn. Looking back on it academically it was not very good. We had a few very good professors. Some of them were officers, but most of them were just ordinary types and further more, it used to take... They had a system where they had to get a daily grade every day you went to class. For example, in math, he'd send you up to the board and work all these things and I used to try to derive my formulas, so I didn't get very good daily grades, but on the exam, I did very well. On a 4.0 system, I'd be down something like a 2.7 and 3.6 on the exam, but the daily grades counted for a great deal more, so my standing was not as high as it might have been. We were always very good at exams anyhow and at law school the exam is the whole thing. I didn't have any difficulty at the Academy and I'd have to say that I enjoyed it.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you relate to the harassment that the plebes always seemed to get from the upperclassmen in that first year?

John E. Greenbacker:

We never got bothered a great deal. The class of 1939 which was ahead of us, were a very unruly class. They caught all the hell. We sort of drifted along in their shadow, so I don't recall getting very much in the way of hazing on a regular basis. Once in a while someone would come in, but somehow we were the beneficiaries of changing ideas of how they ought to handle the plebes and so we benefited from that, but the previous classes had a much tougher time. We did have to walk down the center of the passageway and square corners.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have to sit on your imagination in the meals?

John E. Greenbacker:

I never had to shove the chair around. We sat at the second class end the table and we used to have to put on little skits for them, but there was no real disciplinary action taken down there and I don't think I ever had to put my chair under the table.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about extra-curricular activities, did you do much in the way of athletics or sailing?

John E. Greenbacker:

I was on the outdoor rifle team and got my letter in rifle and was able to go to the _____ dance my last year down there in the boathouse and I did a little boxing, but I was never good enough... I finally got to the point that I could keep people from clubbing me, but I could never hit hard enough and I was on the boxing squad, but I was never really on the team.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was Uncle Beanie on the staff when you were there?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

He's one that made an impression on a lot...

John E. Greenbacker:

He was character, but I don't know that he was all that tough.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was what I hear stories about, pranks that he... Apparently he was a real softy once you got past that shell.

John E. Greenbacker:

I once got put on report. We were over firing the pistol. That forty-five was a terrible weapon. We've had a lot of people injured aboard ship and you can't tell whether there is a shell in the chamber or not and it was so hard to hold if somebody would fire it, it could go anywhere from down right in the ground ahead of you or straight up. I did get to be expert in the pistol, but only after I got out to the YORKTOWN, but this submarine officer, as a matter of fact, he's the one that had to be relieved, because he was a tough character, but responsibility in war time apparently broke him down, because he had to be relieved from command of a submarine. I was on the firing line and I was throwing clips back and I would turn to ______ the clip back and he accused me of deliberately pointing the pistol at everybody and I didn't get into any great trouble, but it annoyed me, because he was exaggerating what actually happened.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other recollections of experiences at the Academy or anecdotes about personal things that happened?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. All my friends were from the south. I don't know why that was, but Haywood Smith, here in Raleigh was one of them; one from Chattanooga and a couple from Mississippi. We were a close group and I have a picture in there showing the five of us _________ who came from here and he flunked out the second time and he said that he did not know what a poor education he had as a background. He did not know, when it came to the Naval Academy that the sum of the squares of the sides of the right triangle equals the square of the hypotenuse. I had a much better educational background than a lot of these people did and the reason that so many of them seem to flunk out is that they

didn't have to take the entrance exam if they were of satisfactory status in college. In those days, Southern colleges were not flunking many people out. They may not get a degree, but they'd keep them on there.

Donald R. Lennon:

With the class of 1940, did very many of them go to the prep school, such as the one in Washington. I know the Class of 1941, quite a few of them went to he prep school there in Washington to prepare them for the Academy.

John E. Greenbacker:

There were a bunch of those, people that had gone to the prep school and I don't remember the exact number, but there was also these personal prep schools and the Navy had one and I did not realize that if I had enlisted, the enlisted quota for each Naval Academy class was one hundred and fifty. They never filled it and they had a prep school up in Bambridge, Maryland, I believe and that would have been a sure way of getting in. Although, maybe if I had enlisted, I would have gotten trouble and wouldn't have made it.

The other thing interesting was I didn't have a date before I went to the Naval Academy and the plebes weren't allowed to date, except they could go to the shows of students, plays, musicals. I took a couple of fourteen year old girls and that was my start at dating, but then they also had and I don't believe they have them anymore, the stagline hops(?). The stagline would take up about half the floor and it was an easy way for me to get started dancing, by just putting my dress uniform on and going over to the hop and cutting in on somebody and making them put up with me for a few minutes. Then, I had my... My first roommate had flunked out and he came back in two years later. He had enlisted and came back in that way. He was from Massachusetts. He flunked out again, but he was trying to sever his relationship with my wife and so I got a blind date, because

I could take her to the hop and he couldn't as a plebe. She said that she went home and told her best friend that, “I've met the man that I'm going to marry.” I tell everybody that had I known she'd said that, I might have run. We were finally married after the YORKTOWN was sunk in 1942, three years later. I dated her a great deal once the YORKTOWN came to the east coast to participate in Mr. Roosevelt's secret war. I can't think of any other things. If I go back and look at the Lucky Bag perhaps I could remember some of the anecdotes, but it's the only thing that comes to mind at the moment.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, when the class graduated, you were appointed directly to the YORKTOWN, were you not?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you rate a carrier for your first assignment?

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, carriers were not considered number one. Most of them went to Battleships where they were so far down they really didn't have anything. I was first ordered to a cruiser, but then because of my eyes... I was having problems with my eyes and had to take an exam to see if I could get a regular commission two years later, as a matter of fact, after the war started, I went to the hospital to get my eyes checked out. I was the assistant navigator and by this time, because I wasn't doing so much studying, the eyes had recovered and my eyes were dilated and the doctor didn't believe that... He thought I had memorized the chart. He said, “You couldn't possibly see that well.” So, I was ordered to come on back a couple days later and they had a great big chart with all these small letters on it. I went down on the left to the thirteen line and go across. There's no way to memorize that one, so he had to O.K. me and I got a regular commission. My eyes

generally ________ went down hill rather steadily. A sort of interesting thing that I learned is that if you're eyesight is not too good and you're trying to identify a ship, you look for different things that you can see readily. Most people with good eye sight would just read the hull number.

I went to the YORKTOWN and we were very fortunate in that the Navy was expanding, so generally ensigns get the job of being assistant this and assistant that and I was given the job of assistant navigator, which generally didn't go to someone who had less than two years or more services. So, I had very good jobs, first year as assistant navigator and then as the ship's secretary, but the Navy didn't believe in aircraft carriers. There were some influential people who saw that. I remember going over to Hayword Smith over in the COLORADO, telling me that, “You ought to be over here in the real Navy.” The surface Navy was obsessed with the Battle of Jutland(?) and it was always my idea that when they didn't have any battleships, when we lost all those cruisers in 1942, rather than casting loose the destroyers as they would if they had cruisers, the battleships would be the main battle line and the cruisers ______, but because they didn't have any battleships, the cruisers took their place and they lined the destroyers up. The Japanese with those long lance torpedo's just picked them off. It wasn't until ______ Burke got out there that they really started using destroyers properly, but I was impressed with the, for example, our torpedo plans. I said, “You know, if they came in on both sides, how would you escape them an attack?” When I went to the YORKTOWN, two of the four squadrons were _______ and on reflection here in recent years, I think we have to thank Roosevelt for expanding the Navy as he did, we did not get _______ fighters until May of 1941. We know that was roughly six months before the war started.

Suppose we had to go out and fight the Japanese arrows with those modified World War I type aircrafts. Furthermore, Roosevelt was always misleading people to get his way. The YORKTOWN, they called, the WPA ship. It was built down at Newport News and it was not built with a Navy appropriation. It was built under the Works Progress Administration.

Donald R. Lennon:

Really?

John E. Greenbacker:

Of course, he got three carriers built down there, the YORKTOWN, the ENTERPRISE, and the HORNET and we were fortunate that we had those ships and the new aircraft, because there was no way that we could delay getting out there and facing the Japanese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course, Roosevelt had an identity with the Navy.

John E. Greenbacker:

That's correct. As a matter of fact, they used to say when the flag selection list came over, he used to get out the Navy register and go down, remembering a great number of those people. He just saved the American people and we're fortunate that he did. Also, we were out there in the Pacific and then we were brought around to the Atlantic to conduct Mr. Roosevelt's secret war which he did by extending out the neutrality zone and supposivley we were on neutrality patrol. Actually, in the fall of 1941, we participated in an escort. The 5th Canadian Armored Division was coming up, being rotated home and so this was a troop convoy and we went out to MOP, the mid-ocean meeting point which was sort of south of Iceland and here came this pitiful looking set of escorts that the British had and half a dozen little small things and we had a battleship, two cruisers, an aircraft carrier, about a dozen destroyers and we brought them back to Halifax and we didn't have any contact with. The country as a whole... There

was so much sense of Roosevelt had to face. It was the man from Chicago who was an isolationist father, somebody. Anyhow, he had to contend with those people and as a practical politician, he couldn't just push them aside and as a result, although there was a lot of talk about our going to war along the east coast, but it didn't extend very far into the country and what we were doing there did not extend to the fleet out in Pearl Harbor. As a matter of fact, there was an assumption among the staff of the Commander Aircraft Battleforce that we'd spent all the time in the yard. He said, “Well, let's see your new bridge?” My classmate over on the ENTERPRISE was telling me that it would do us some good to work with the Battleforce and get ourselves straightened out. Actually, we were in much better shape because of our work in the Atlantic and working with the British on fighter direction. This is something that those people weren't up on and we had a very good fighter direction organization. Also we were fortunate that our gunnery officer was Ernie Davis(?) who comes from North Carolina. He would get twenty millimeters... That was another thing.

When the war started, they taxied the air group down and loaded aboard--this was the Monday following that Sunday--loaded them aboard. All the wives were out there weeping and everybody was so nervous and the _____ pulled the ship out before the brows came down and they went crashing down on the deck and we went out to the anchors. The next day, came right back in, unloaded the air group and put us in a shipyard for four days and we got, instead of the fifty caliber machine guns, we got twenty millimeters, which had an explosive bullet in it and really made the difference. Jocko Clarke was our exec. and he was so down on everybody aboard the ship and there's a professor up at Annapolis that sort of took his side and I wrote a couple letters to

the editor(?). Well, I wrote a letter to the professor saying that the ship wasn't all that bad. Dixie Keifer(?) became the executive officer after Jocko left. Jocko would sit playing cards in the board room talking about how he didn't have anything to do with all these fine department heads he had and of course, morale just soared and Jocko went stomping around the ship when we were in the shipyard and said, “What the hell are we wasting our time in here for. Let's go out and get those bastards.” If we hadn't gotten those twenty millimeters, I don't think we would have survived the Battle of the Coral Sea. Fortunately for the Navy, by the time that Jocko made Admiral, we had such a superiority of force that being aggressive paid off.

Ernie Davis delegated the responsibility right down to the gun of making sure that no attacking aircraft came in without being shot at and we didn't have the problem that they had over at the ENTERPRISE when we first made those island raids in the beginning of the war. One of their one point one mouths didn't not open fire at all, even though they were being attacked by a Japanese aircraft, because they didn't get the word to open fire. We used to do a lot of training, teaching these people how to lead the target and at the Battle of the Coral Sea, it really paid off, because we had so many aircraft, dive-bombers coming after us. We shot down thirteen of them. They were very unfortunate, because we had to come down and there was at least one place where the bomb hit the walkway around the flight deck and of course, it went off and we had some near misses. Half the ship was being shaken up so, I thought our stern was being torn to pieces, but it wasn't. It was just things exploding in the water. Over on the LEXINGTON, the ship that was lost, the captain in his report said that anti-aircraft fire, as usual, was ineffective. It wasn't ineffective with us and it really made the difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now the Coral Sea was the first engagement that the YORKTOWN was involved in, was it not?

John E. Greenbacker:

Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think that the experience in convoy duty and being up in the North Atlantic was a worthwhile training... What it amounted to was a training and acclamation type of thing.

John E. Greenbacker:

Our air group really became part of the ship. The airgroups really tended to be rotated on and off during the war. Those people worked with us for over a year and they felt part of the ship and I think the sense of being in combat was important and we certainly had that. We used to tease the chaplain, Chaplain Hamilton, he went around with a gray face all the time. Apparently he hadn't made peace with the lord. We would sit down at a table with them and we'd start talking. I said, “Well up there in the North Atlantic, the water is so cold that if the ship had sunk, should you take your clothes off and freeze or should you keep your clothes on and be dragged down to drown.” He would say, “Gentlemen, I don't think that is a proper subject to talk about at the dinner table.” But, that sense, and also the fact that we had developed, as I said before, the fighter direction. Now, unfortunately because there was an aviation admiral over on the LEXINGTON, Frank Jack Fletcher gave them control of fighter of direction and as a matter of fact, we could see that they just weren't doing a good job. They'd send fighters out in the wrong direction and also the station of combat air patrol at twenty thousand feet and they wanted to know at what altitude this incoming attack was and they never got an answer. The incoming attack came in at thirty thousand feet and of course, there's no

way that our fighters could get to them as they wiz by and that's why we had so many dive-bombers coming after us.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the YORKTOWN equipped with radar this early?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes. We got our radar. It looks like a bed spring and we got ours the first time they had them, about the time I joined the ship when we were out in Pearl. We learned to use ours properly and a lot of these people didn't. Based on that learning, we had a combat information center later on when I had command of the DE, we built ourselves a combat information center. This was before the Navy put them on. I did that based on my experience on the YORKTOWN of our airwing commander or airgroup commander, I think they called them in those days. We didn't give him flying job. He was in our flight control, which was a combat information center, directing the fighters just as the British did, over in the Battle of Britain.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did the YORKTOWN leave Norfolk for the South Pacific?

John E. Greenbacker:

We left Norfolk... You see the seventh was on a Sunday. I think we went out the following Saturday or Sunday. It was probably the following Sunday.

Donald R. Lennon:

So as soon as they changed those guns.

John E. Greenbacker:

Four days. Four days they took those fifty caliber off and put the twenty millimeter on. The twenty millimeter was really a great weapon.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the ship was ready to... Had December the seventh not happened when it did and we'd not gone to war at that part, was the YORKTOWN already under orders to go to the Pacific or anything or was that just a reaction?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. We would have continued in the Atlantic. It is my impression that German submarines were trying to avoid Americans and the group __________, a destroyer that

was sunk, Roosevelt said here it was carrying mail to our troops in Iceland. Actually, it got contact with a German submarine and just maintained contact, just REUBEN JAMES(?) and calling in British aircrafts. They probably would have avoided him had the REUBEN JAMES(?) stuck so closely to them, because British aircrafts were going to be coming in on them. So, they sank it. I think that Hitler wanted to keep United States out of the war and the Navy called it lend-lease(?) which is what came on one of his speeches. He says, “Just imagine that suppose your neighbor had a fire and lost some of his equipment. You would let him yours.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Nice rhetoric.

John E. Greenbacker:

We had reverse lend-lease(?). I'll get to that when I get to the sub-chaser.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were not up in the North Atlantic at the time when the REUBEN JAMES was torpedoed, were you?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes, we were. That was in the fall, September or something like that of 1941. As a matter of fact, it was earlier than that, because the captain and the exec., Jocko got very upset, because some enlisted men wrote a little poem that said, “There will be a plaque on the Thames(?) for the REUBEN JAMES.” Of course, he didn't account for the fact that we call it the Thames up in Connecticut. They were very upset about this attitude and nothing ever came of it, but you know, that was fairly early on, but we were in the Atlantic by this time. We came in February or something like that. We had an exercise off of Pearl Harbor and then we refueled and headed for the canal. I don't remember whether the people with wives out there were told that we were leaving. Of course, I didn't have one, so I didn't have anybody to notify. We headed for the canal and we went with a bunch of destroyers and the division of battleships that came later, but we went

there in the early spring and then they put us up... I guess to conceal our presence, we were sent three weeks in Bermuda and then finally we went up to anchor up in the southern coast of Labrador, I guess it was. I forget the name of the place, but that was major base and then during that fall, we had our destroyers were actually right with the British escorts. They were really escorting. We only had that one experience of being in an escort group when we brought the Canadian armored division back. I think he would have kept them there. Now, how he would have maneuvered us to get in the war in case they looked like they were going to invade, I don't know. It was never quite clear to me why when the Japanese attacked and we went to war against Japan, Germany and Italy felt that they had to declare war against the United States. Suppose they hadn't. I don't know what they would have done, but they declared war before we declared war against them.

Donald R. Lennon:

They knew it was inevitable.

John E. Greenbacker:

Then of course, since we had no convoys of our troops, we really lost the newspaper clipping I had, the recollection the German ______. There was no defense at all. At least when we got convoys organized, but that first six months was a real disaster along the east coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once the YORKTOWN departed for the Pacific, did it go into Pearl initially or did it go directly into the war zone?

John E. Greenbacker:

No, we went to Pearl and then we made one or two raids out there on those islands and then we went to South Pacific. As a matter of fact, I learned to type and was a fine secretary. I learned to type, because we went over a month without getting any mail at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of raids?

John E. Greenbacker:

These were just on their island, on their bases, go out there and... The ship itself never got involved in any kind of combat at all. It was all the air group. We were down there just patrolling and they were concerned about the fact that the Japanese invaded New Guinea and that's how the Battle of the Coral Sea got started and there was so much confusion the night before the main battle day and I was the battle day officer on deck, because everybody was on battle stations and I got the job of flag secretary, but I said I wanted to qualify as an officer of the deck. At night, three Japanese aircrafts approached. We were recovering our air group and I think that this is the day that they did sink that little tiny Japanese carrier and they kept flying around. They were lost, obviously and they kept circling around. What we should have done is called off the recovery of the aircraft and tell our fighters to go after those. Finally, it was over the YORKTOWN and it passed over the YORKTOWN and headed right for us, the three of them. Ernie Davis, the gunnery officer, says, “Tell the captain that I want to shoot if they come.”

I said, “Nobody open fire until we open fire.” ...tracers all over the place and they did get shot down by one of our fighters or at least one of them did and maybe the others got away, but when an aircraft took a wave off, they always went off to the left. This time, it was getting dark and one of them went to the right and one of our twenty millimeters on the starboard side, since he didn't expect to see one of our own planes coming by, he opened fire, but the change of angle was so fast that he really couldn't get a hit, although he got one bullet and it went right through the canopy. There was a lot of hard feeling down there in the ward room. They almost had some fist fights. However, the next day when they came back from their attack on the two Japanese aircraft carriers,

they saw that we were still operating and the LEXINGTON wasn't. That changed their attitude considerably. We downgraded in the Battle of the Coral Sea, because we didn't think they hit anything and also Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, Admiral King was down on him. You know, somebody in the Naval History wrote an article about how Frank Jack Fletcher got a bum deal and he did. It wasn't until many years later when we started learning stuff from Japanese history, that those two big aircraft carriers, one of them was so crippled that it almost capsized on the way back to Japan and they lost very heavily in their air group and so those two ships were supposed to participate in Midway and they didn't because of the fact that we put them out of action at Coral Sea. We were never given much credit for that until recent years, but had their been six carriers at Midway instead of four, the odds that we were able to sink all six of them are pretty much lower. One of them probably could have come, but didn't have an effective air wing and the other one was crippled.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, Coral Sea was your first encounter with actual hostilities. How did you react to...?

John E. Greenbacker:

I suppose I was scared, but the story I tell... We had these kids up in the loft, people controlling gunnery and these bombs would come down and they would be over there looking at the bomb coming down and run over there and look at the bomb hit the water. I don't think I would have done that. We didn't have an open bridge. The captain was out on the wing maneuvering around. Of course, we didn't have signals in those days. The destroyers were just supposed to keep out our way. I peeked out the window of the pilot house and I could see this long line of Japanese aircrafts coming down. So, I pulled back in and I said that it's really not my job to look at those damn things. My job

is to watch out for others and make sure we don't run into our own ships. The captain had the job of maneuvering and the gunnery people had the job...

END OF SIDE 1Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of actual hits did the YORKTOWN actually suffer at Coral Sea?

John E. Greenbacker:

We had a near miss back aft that had ruptured an oil tank. As a matter of fact, they reported that we could have been tracked by people going up that ____ wake. That got repaired up in Pearl, but they brought us in... We did not go out to Midway with the other two carriers, because we were in the yard getting those emergency repairs. I supplied a considerable amount of information to Walter Lord(?) in his book. I've probably got a copy of it some place in these papers, nineteen single spaced pages reporting that. That was the only damage we had. It was a near miss and it was close enough to rupture that tank. As I told you, we were really bouncing around and I was convinced that we were being hit back aft. I couldn't see back aft, but I could see forward and we weren't being hit up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you not had those heavier guns, the twenty millimeters, you probably would have had less protection.

John E. Greenbacker:

That's correct. I think that twenty millimeters was a key to our being able to shoot those people down and of course you know, that kind of fire coming at you, the pilot is likely to be a little bit fast and a little bit higher when he releases his bomb. I think that was essential to our being able to survive the Coral Sea and of course, those aircrafts coming in, those dive bombers were not intercepted by our fighter patrol, as a I pointed out earlier, because the LEXINGTON's air control didn't identify the altitude.

We did not have at that time, height-finding radar. There was a chart you used to show how your radar contact would fade in and out. We determined altitude from that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the YORKTOWN within visual proximity of the LEXINGTON when it got hit?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes, but as we maneuvered during that attack, I think we gradually got out of sight. There was a lot of argument in those days about whether you should keep them in formation. Later on they did. They'd have three carriers in a task force and a screen around it and when they maneuvered it under attack, it was by signal and they all turned together, but we didn't have that then, so all of our maneuvering was just by individual ship and we did get further separated, but before that, when we steamed, we'd steam within a few thousand yards, but during the action, of course, we drifted apart.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you were not observer to the ship sinking.

John E. Greenbacker:

No. I think we saw her in the distance dead in the water and of course, since that was a battle cruiser originally, the fuel system... There was no way that they could clear it before an action. With ours, we could clear all the pipes that carried gasoline and put CO² in them. They not only were hit, but then they had a lot of explosions later on and they couldn't recover their air group.

You know, one of the things I had to recall here recently, you know all this noise about friendly fire? Well, we started the Battle of Coral Sea shooting at our own aircraft and we ended the action shooting at our own aircraft. It wasn't really so dangerous the second time, but after the battle was over, we had a squadron and the Japanese torpedo planes came in a shallow 'v' all spread out. Approaching were all these planes coming in and you couldn't see from ahead, they had turned and showed us a silhouette and the

gunnery officer was saying he wanted to shoot at him and the air officer came out to the bridge and here he is, an aviator with some twenty years experience. He had been one of the squadron commanders before he became the air officer of the ship and he got to borrow some binoculars and he looked at the aircraft and he says, captain, those are not our aircrafts. So, the captain said, “Open fire.” They were out of range when we started open firing and so they called back to the LEXINGTON and he said so and so, “call them off.” Then they turned and we could see that they were ours.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's an inevitable part of warfare though, isn't it?

John E. Greenbacker:

That's correct, but they made such a big deal over this sort of thing now and of course, we had so few casualties. If you had the kind of casualties that the ground troops had in World War II, people being hit by friendly fire, it wouldn't have been so significant on a percentage basis.

Donald R. Lennon:

Identifying which ones were killed by friendly fire would be relatively difficult. In a situation like that, with the LEXINGTON and then with the YORKTOWN at Midway, what happens to the air group when they are not able to return to the carrier?

John E. Greenbacker:

I think at Midway... I don't know what happened to those... Well, they landed aboard... You see, the LEXINGTON didn't realize that they... Most of their air group went down with the ship, but at Midway when we were hit a bunch of our aircrafts went over to the other carriers.

Donald R. Lennon:

There is sufficient space on a carrier for additional planes?

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, you probably had so many aircrafts that were damaged and just pushed them over the side.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, after the Coral Sea, you were sent back to Pearl for repairs.

John E. Greenbacker:

We were sent back to take part in Midway. They knew the Japs were coming. As a matter of fact, I, ship secretary, I was the one that had to pick up the operation order and I was up on the bridge telling the captain that it was just amazing how much we knew about them. The captain said, “Don't even talk about it.” We knew everything they were doing, but we were sent back there to participate.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the battle already underway when you arrived?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. We were late getting out there, but maybe we were a day ahead of time or something like that, not very much. Meanwhile, the other two carriers were already there and we never saw them. Admiral Spruance(?) was controlling them and Frank Jack Fletcher came under criticism for turning everything over to him and I pointed out in one of my letters that he went to the cruiser after we were put out of action and the cruiser did not have the facilities, communication facilities to really continue controlling them, so he turned all of tactical command over the Admiral Spruance(?) and then of course, after the ship was sunk, we didn't have information on whether the Japs were still coming or not and we were told on our operation order that under no circumstances risk surface contact with their battle line. As a matter of fact, admiral Spruance did a great thing when he pursued them. Admiral Yamamoto(?) lined up his battleships with the idea that if they came close enough, he was going to get them. Fortunately, Admiral Spruance turned around in time to avoid that, but once we were out of action, the admiral left ad went over to the cruiser.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that you were not in proximity at all to the other carriers in this. Were you operating with just destroy escort, operating independently or were you just physically out of sight of them?

John E. Greenbacker:

We had a group there. We had our destroyers screened(?) and then we had a cruiser too. I think they sailed with us. They went ______ screen(?) and meanwhile, the LEXINGTON and the HORNET were operating together in one group.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us, if you will, something of what transpired with you personally when the YORKTOWN began to suffer hits during the battle.

John E. Greenbacker:

We were dead in the water. The first attack... I'm convinced that the reason anti-aircraft wasn't as obviously effective as it was at Coral Sea is that I think these Japanese pilots knew that they weren't going to go home. As a matter of fact, one of the dive bombers came down and was being hit and it lost its wings and toppled over and the bomb came loose and they had armored piercing bombs and they always went deep, but this one must have landed on its side, because it exploded right on the flight deck. Of course their planks out there, their metal planks, so we could still operate the aircraft. The thing that stopped us was one went down the smoke stack shaft and disrupted the air supply and that is why we were dead in the water and we finally got up only to twenty knots by the time that the torpedo planes came in.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said the planes attacked with a vengeance that hadn't been the case at Coral Sea. They were operating then almost as Kamikazes?

John E. Greenbacker:

Very close to it. A great determination there. We're going to get them, because they've got us. I think that's the case that they survived all the fire and when the torpedo planes came in I had to admire our fighter pilots. They hadn't refueled. They took off and turned and came in on the port side. They took off, made a sharp turn and went right down our line of fire. We were shooting and they were close to our line of fire. So, I had

to admire those pilots for having that kind of determination. We got hit by two torpedoes. Of the dozen or so that came in, there were only two of them that got hits.

Donald R. Lennon:

The destroyers and cruisers you had with you were not effective in ______ the bombers or the torpedoes.

John E. Greenbacker:

I suspect that they weren't as good as our gunners were, because they didn't... I think we were very fortunate in having Ernie Davis from Beaufort.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course, Earnest Davis. I knew of him. I knew his brother very well, James Davis. He was also Rear Admiral.

John E. Greenbacker:

Ernie Davis was a genius at getting that air defense organized and that's why we survived the Coral Sea. He said that our gunnery wasn't as effective, but I think we were fighting against pilots that came very close to having a kamikaze attitude. You know, if you expect to go home and see your family, when that fire starts getting heavy, you drop the torpedo and turn away.

Donald R. Lennon:

A little more conservative.

John E. Greenbacker:

Right. They flew right by the ship. The ones that hit us actually flew right by. The pilot was waving his fist at us.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your feeling during this time?

John E. Greenbacker:

I really didn't have time to reflect on anything. I think our experience in Coral Sea probably gave us a little more self confidence than we deserved to have. I think we were calmer about it, because we'd been through something like that before. Of course, it was just momentary. This attack came in and then we became dead in the water and the fact that we could only get up to twenty knots rather than thirty knots had a considerable thing to do with the fact that they got the hits that they did with the torpedoes. The first

lieutenant called up to the bridge and said, “Tell the captain that I can't do anything to take the list off the ship.” People have written articles criticizing that, but we did not have... There was no way that we could get power to do to the pumps and we didn't have all the portable equipment that we have and we didn't have the cables, electric cables that you plug in the bulkhead and you ________ with that cable. They had that later on in the war. There wasn't anything he could do. They hit the forward distribution board. It flooded and killed everybody there. They could not keep the circuit breakers closed in the ______ board, so.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were no emergency generators that could be operated independently, huh?

John E. Greenbacker:

That's right. So, there wasn't anything could be done and of course, the ship had capsized with everybody aboard. One of the things that they did learn from that battle is to disembark or abandon ship of people that they didn't need for damage control and that's something that they did later in the war. They had a partial abandon of ship, all the air group for example or people with the guns. The damage control people stayed on board and tried to work on the thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did that happen on the YORKTOWN?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. That was later.

Donald R. Lennon:

Everyone abandoned.

John E. Greenbacker:

Everyone abandoned. We didn't have any. As a matter of fact, we didn't even practice abandoning ship, because Captain Buckmaster thought that that was bad for morale to even think about abandoning ship. People didn't know... For example, my roommate went down there in the boat and his battleship station was in a motor launch. They went down there and sat in the boat and wondered where the crane operator was.

There was no way that under abandoned ship that we'd do anything except go down those lines. They didn't teach the people how to abandon by going down those knotted lines and some of these people that would slide down were people that got burns on their hands, but the knots would rip up the strings on their lifejackets. Ernie Davis was damaged after that week when we abandoned the second time. For some reason he got in the water. The underwater explosions gave him a lot of intestinal damage. I didn't want to get wet, so I was one of the last off and I went down to the quarter deck and up in the racks underneath the flight deck were spare aircrafts and I went up there and got one of these two-man life rafts, inflated it, put it in the water, got ready to go down and by the time I got down there, some other people had gotten it and were paddling away. I was afraid that I had too much. I had my binoculars and my pistol. I had a flight jacket that I had picked up on the flight dock. Actually, it had fifteen hundred dollars of fighting forty-two's money in it. Had I known that, I could have stuck it in my shirt. They panicked also. I got to the raft and was pushing it along and I put all my stuff in it and then the destroyer nearby started sounding its alarm and there was an air attack coming in and they wanted to recall their boat. So, I left the life raft and went over and climbed in the motor whale boat. Then, aboard that ship, somebody brought the binoculars and the pistol, but not the flight jacket. When we were on our way back, the salvage party was on its way back. The pilot said, “Look outside the _______ because I've got my flight jacket there and its got the fighting forty-two's welfare money in it.”

I said, “Sorry, I tried to get it. It didn't make it.” Everybody was very enthusiastic about going back. We had to station guards at the little thing you ride in when you go from ship to ship. One of the funnier things. The destroyers were still out there and they

were terrified of course, being left there with a carrier. They were just circling. Our ASW, particularly in the Pacific was not what it was in the Atlantic. We got a lot a better in the Atlantic against he German submarines. They sent some people over to get the coding machines and then all this excitement, because we'd never practiced at it. All those coding machines were just left. They should have been thrown overboard. The signal bridge did throw their books overboard, but down there in our communications center, they didn't and so this destroyer did that and then this destroyer picked up a lot of damage control equipment, a bunch more than they were entitled to. So, when they came along side down there, the _____ deck was almost in the water. They came along side and they stored all that stuff aboard.

Then, another destroyer sent some people over and their instructions were to see what they could do to try to take that list off the ship. So, the first thing they got to was all this damage control equipment. They threw it all in the sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Although the YORKTOWN was listing at twenty-two, four, five degrees, was it still taking on water or had the compartments sealed and stabilized?

John E. Greenbacker:

I think it was stabilized at that point. With that stabilization, if they had known they could depend on, they could have hooked a cruiser to it and towed it out of there. As it was, by the time we got back, there was a fleet towed that had a line. It was only making one or two knots, something like that. My job was to go around to all the ready rooms and pick up the flight pads with the flight codes and lock them up in the safe and I also picked up some of those leather flight jackets and put them in the safe also. Then, we had an alarm system going to alert everybody in case it was an attack. We had the destroyer along side. There were fires going on and destroyers put their hoses over and

that's the _________. Somebody said, “torpedoes.” A twenty millimeter alarm gun is sounding off and the HAMMON(?), which is the ship along side, sank and then when she went underneath, I thought she took more casualties then they did. This is one of things that I said saved me. I should have sold my story to Coca-Cola, because I was supposed to take all the flag files and I had them in big mail bags and I got down to the quarter deck and they had some snacks there and all these Coca-Colas and I was standing there when the alarm went off. I was supposed to cross over to that destroyer and then get in their boat to go to a destroyer that was scheduled to go inland.

Donald R. Lennon:

Instead, you took a Coke break.

John E. Greenbacker:

That's right. Now, if I hadn't, I would have been over there aboard the HAMMOND(?), but she went down and all the depth charges exploded and before they exploded, you could look out there and see all these people in the water and after that explosion, you just see a ring of people around the edge. I thought they must have lost almost all of them, but that wasn't the case. They did have pretty heavy casualties about a third It would seem to be to be so long before those torpedoes hit and they sit on our starboard side, which is a high side. Then, I went all the way down to the port side which was right on the boarder of the hanger deck. I said, “Suppose there's a submarine over there,” so I worked my way back up _______. I didn't think about the fact that the aircraft might fall on me and I took the bags and wrapped them with cable, so that they wouldn't go floating around and just waited for the thing to strike. The captain... Everybody was so stunned at this point that nobody knew what to do, but finally the first lieutenant sort of gathered everybody together and said, “Let's get up on the ______. We don't have anymore life rafts. Let's get up on the _____ and be up there to follow the

ship in case she were to roll over,” and then we got up there and they said, “Let's go back into the officer's quarters, since it's right aft of the _____ and get mattresses out of the officer's quarters.” So, we went back and the farther you went back inside the ship, you're in a narrow passageway and the number of the people going back got smaller and smaller and finally all the way down, almost to the end before you get to the hanger, there was only one sailor with me. So, I got him the silver star.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was kind of an erie feeling, was it not, to go back deep inside a dead ship?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes, it was. It was very scary, but I did go all the way back. I didn't have anybody to recommend me for a metal, but I got him one. After all, it my responsibility and sense of duty was supposed to be better than the enlisted man, and he was remarkable. Then the tug came along side. A couple of our officers had gone down below earlier that morning and packed up their bags and they were throwing suitcases over to the tug. The tug's crew which was very nervous, because that's exactly where that destroyer was, they didn't appreciate this. Then, the exec. Dixie Kiefer(?) had broken his ankle going over the first time and so the navigator was the acting exec. and the captain says, “Is everybody off?”

He said, “Yes.” Then, the captain got off and onto the... Then chief engineer and two of his people showed up. The captain was there with tears in his eyes and he said, “You told me everybody was off the ship,” and then he tried to take a line and swing back and touch the ship and again, the skipper of the tug didn't care for this bit of protocol, so he never succeeded and he never forgave the navigator and gave him a bum fitness report. I don't know how he would have told that everybody... I don't think we had a close count.

The attitude was changed. The captain was going to go back the next day. Remember I said that there was great enthusiasm of going back and saving our ship, but after those torpedoes hit and the destroyer went down, we always had the feeling aboard ship that enemy will attack the ship and they may get us, but the destroyers will always be there. When the HAMMOND sank in five minutes...

Donald R. Lennon:

That gave you a really futile feeling.

John E. Greenbacker:

Yeah. They looked very vulnerable. There were five or six destroyers out there, but they didn't look like they could save us. Then, all the junior officers are saying, “well, of course if the captain wants us to go, I'll go, but I don't see that I can do any good over there.” Then, we got transferred to a destroyer and the next morning, the ship rolled over.

Donald R. Lennon:

Initially, before that second hit by the torpedoes the next day when the HAMMOND sunk, they could not have intentionally flooded compartments on the opposite side from the sides ______ on to try to ______ it?

John E. Greenbacker:

They didn't have the equipment to do it. There was a diesel pump, but they only pumped the main drain, which was the main engine spaces. If they got flooded, they could use those to pump that out, but they couldn't pump a flood in on the other side at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

That could have balanced it, could it not?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yes. That could have. They had a little fire to put out, but I think they were doing some flooding from the destroyer HAMMOND, but we had to use their hoses, because we didn't have any power. A lot of the criticism of the YORKTOWN... We never got the Navy citation. Actually, I learned from Ernie Davis that the _____ when they were

reviewing everything after the war that they wanted to give the YORKTOWN a unit citation, but the skipper of the LEXINGTON was then commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet and they knew that they couldn't get away politically with giving the YORKTOWN one and not giving one to the LEXINGTON and they didn't want to give one the LEXINGTON, because they'd performed so poorly, so we didn't get one either. That was that story and a lot of people felt that the YORKTOWN didn't deserve to get one, but that wasn't the reason they didn't.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, after it sunk, you were transported back to Pearl on one of the other destroyers?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yeah. Then we sat there and because they did not have the organization going for survivors of ships that got sunk, later on in the war, you got a new pay record, a new health record, a new service jacket given thirty days leave, and you're on your way. We didn't get that stuff. They finally sent us to San Francisco and we sat there for about a month. We got there on the fourth of July and it was early August... In fact, everybody was getting married and I finally called my wife and told her to come on out and my mother in law got on the phone and said, “What are you going to do when she gets out there?”

I said, “Well, I sort of thought we'd get married.” We got married on the twenty-fifth of July in a cathedral up there and then we sat for a couple of weeks more.

Donald R. Lennon:

One question that I meant ask you before we got entirely away from Midway, was the battle of Midway still going on at the time you were trying to salvage the YORKTOWN or had the battle itself...

John E. Greenbacker:

The battle had ended. I think they were still attacking. I remember there is a picture of a cruiser, a heavy cruiser that they attacked and it looks like the guns were _____. They lost ______, so they were still running after... Admiral Spruance was pursuing them. They had turned around and lost all their carriers. They knew they weren't going to be able to take capture of Midway, so they were retreating, but he did form a defensive line of his heavy ships and I think under Admiral Spruance those two other carriers, of course, didn't suffer any attack at all. They were continuing to go after them, but after a couple of days, I think, Admiral Spruance saw fit to turn around and that was the end of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course, you still had the danger of Japanese submarines in the area, even though the battle itself was over. Those torpedoes that sunk the HAMMOND, were they submarine torpedoes or torpedo planes?

John E. Greenbacker:

No, those were submarine torpedoes. They had a longer range than our torpedoes. This is why when we lost those cruisers they couldn't understand where those torpedoes were coming from, because they didn't believe that they could fire those torpedoes at such a long range, so they had a longer than we did and they probably packed a bigger wallop anyhow. In the submarine force in the beginning of the war, we didn't even have good control of the depth at which the torpedoes were going.

Donald R. Lennon:

The HAMMOND's depth charges that exploded, that was due to the fact that the ship had sunk to the depths that ignites them?

John E. Greenbacker:

The skipper of the HAMMOND was not sure why those things got set. They were supposed to be set on safe when you were in that situation, but they saw one of the gunner's _____ back aft among those depth charges as the Japanese torpedoes were

approaching and he was probably working automatically. There was a submarine out there and he got set to drop depth charges, so he was probably acting automatically, but they had been set on safe when they were alongside. I think they took one hit directly and one went underneath them, because when the ship rolled over the next morning, you could see this big hole in the side toward the bottom of the ship. Of course, getting hit on the starboard side, it sort of took some of the list off, but undoubtedly the next morning, the bulkhead broke or something of that sort, that had been weakened and took on more water and sank.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's an awesome sight, I would think, seeing something that large slip under the water.

John E. Greenbacker:

Yeah.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the YORKTOWN still being towed at the time that it sunk?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. After they got that torpedo hit, the tug had cast off and the tug came around and got along side to take the... We had about one hundred and twenty five people in that salvage party.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they did not reconnect?

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, with those torpedo hits, you never know what's going to happen. The ship

was probably stable enough to have been towed by a cruiser and gotten out of there, but one of the reasons was that the instructions were to not risk any contact with the Japanese surface force and so all of our force, including the ENTERPRISE and the HORNET retreated eastward that night. Then they turned around later, of course, there were signals picking up their radio messages, so we knew that they were retreating. They called off the invasion.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't mean to jump back, but I realized that there was a point that I had been interested in knowing more about. So, after your wedding, you said you stayed for two weeks waiting on assignment?

John E. Greenbacker:

Right. Then, I came back. My wife was living in Washington. We came back to Washington and I went up and visited my family in Connecticut and I never had to tell them a lie. They did not announce that the ship had sunk until September and my family would say, “Well how long is she going to be out of action?”

I'd say, “A pretty long time.” My mother in law knew exactly what had happened. She was so perceptive. As a matter of fact, my wife was going out on a date when I called to call her to come to San Francisco and she says, “What shall I tell John when he calls tonight?” She _____ to something and then she got nervous about it, because my mother in law was able to call those things and I did call, but she knew the ship had been sunk. She never asked me any questions, but I knew she knew that we were down.

My next assignment then was I was ordered to submarine training center. I went there in September. I had tonsillitis, chronic and on my honeymoon I had to call it off and go down to sick bay and I had a fever of one hundred and four, so they put me in the hospital and I was furious about that, but then I went from the hospital down to Miami and went through their school down there and I wasn't too impressed with it, because as a ship's secretary, I thought we had a very good filing system, but they said it was too complicated, can't learn it. I went from there to the sub-chaser 1472, which was a British fair mile(?).

Donald R. Lennon:

This is quite a drastic change from an aircraft carrier to a sub-chaser. Did you request sub-chasers or did it come up in the normal routine of business that they need officers for the sub-chasers?

John E. Greenbacker:

I think that the people were trying, up in Washington, to put a few regular officers in there, for example Sheldon Kinney(?). He was the exec. when I was exec. of the STUART and he went through there and I think they were a little bit concerned about the amateurism of the people that were running the sub-chasers.

Donald R. Lennon:

As we said, they were primarily yachtsmen.

John E. Greenbacker:

They used to call it the Harvard of the south. I remember later on, some of them graduated up into Destroyer escorts and Admiral Holloway, then Captain Holloway, running the shakedown group at Bermuda. At a conference one morning, he said that he didn't want to see any boy scout manuals like the sub-chaser manual. He said, “you've got standard publications. You're a major ship of war and you'll use these standard publications.” I think that they wanted a certain number of regular officers. People in Washington were a little bit leery of that crowd down there anyhow. I think that's probably the reason that I got assigned to down there.

I got up to Boston and found out that the sub-chasers were not going to be ready for some time, so I went over and got my tonsils out. It was reverse lend-lease. The 1472 was a fair mile, a beautiful thing. I didn't look like a war ship. Our sub-chasers had _____ in them and cables out there. This thing looked more like a real yacht. Down in our little ward room it was Mahogany, tape decks. It was built up in ______, Nova Scotia and it was a reverse lend-lease thing. ______ on gasoline. It was faster than our sub-chasers. We had a better sonar. The people that proceeded me didn't want get in action

and in every place they went, including Boston, they took all the British equipment off and then we got down to New York and found that the four ships that proceeded us had said--there was a nice power steering system--that would break down and so put in hand steering, so they had to have a bigger wheel, because the cables went down to the edge of the deck and I got down to New York and I took the beautiful spoked wheel, I put it in ______ and shipped it to Washington. It sits in my office now. I now tell everybody the way I got the thing was there I was with nothing, but the wheel. My associate _____ Dixon, there was somebody that wanted that wheel and he kept bugging us for it and he also wanted some towels. A lot of that stuff was hard to get for personal use and my friend ____ Dixon was a big operator from South Carolina and as a matter of fact, it's his son that is the Director of Athletics at the University of South Carolina. They got fired. He gave him this big bundle of towels and said, “Here, take these towels and let's not hear another damn word about that wheel.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the ship run better being stripped of its power steering and things of that nature?

John E. Greenbacker:

No. They were terrified of the fact that it was gasoline driven. In fact, when we got down to Miami, they isolated us all in one place, so that if we had a fire, it wouldn't eat up everything. They first four stopped at Norfolk and we didn't. We went all the way from New York down to Savannah.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the length of the ship?

John E. Greenbacker:

A hundred and twelve feet. It was almost the same length as our sub-chasers. They had a peculiar sonar system on them. The sonar system didn't retract all the way and one of them lost it by running aground, but we went on, stopped in Savannah to

refuel and then went on to Miami. I went to Houston to be the executive officer of the STUART.

[End of Part 1]

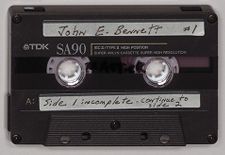

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Capt. John E. Greenbacker | |

| USNA Class of 1940 (DECO) | |

| May 2, 1996 | |

| Interview #2 |

John E. Greenbacker:

I don't know whether I told you about it. I had the job of taking the flags message file. When they left in such a hurry, they left a lot of things behind. I had it in a mail bag and the destroyer HAMMOND was along side and I got the bag ready and I was going to go over to the HAMMOND and then get their boat because one of the destroyers was going back to Pearl Harbor that night. Somebody had brought a whole bunch of Coca-Cola up on the quarter deck and I stopped and had a Coke. While I was drinking my Coke, the twenty millimeter alarm gun went off and people are on the destroyer yelling, “Torpedoes!” Had I not had the Coca-Cola, I would have been over on the HAMMOND. It caught two of the torpedoes, sank it almost immediately and then our depth charges exploded. So, I always thought that maybe I should have gotten a hold of the Coca-Cola Company and...

Donald R. Lennon:

They should have paid you royalties.

John E. Greenbacker:

You asked me last time whether I was scared. It told you that I wasn't particularly scared on the YORKTOWN, but when I got to sub-chaser, twelve people aboard and we

went from Nova Scotia to Boston and that's when I got nervous. I felt that if I ran across a German submarine, it'd be just the submarine skipper and me. That kept me on edge.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those sub-chasers were not quite as formidable than an aircraft carrier.

John E. Greenbacker:

Also, speaking of the HAMMOND going down, we always thought that they may get the carrier, but there will always be all these destroyers out there and then we saw the HAMMOND sink in about two minutes, so we no longer had that confidence. This was a British Fairmile(?) with all sorts of Mahogany and Teek. It was built like a yacht. Our sub-chasers had all sorts of ventilation ducts and heavy cables, but not the British. Their sonar was peculiar. It didn't rotate. When you were searching, it went out port to starboard, ninety degrees, so if she got a contact, you didn't know which side it was on and you'd turn forty-five degrees and if you picked it up again, it was on say, portside and if you didn't pick it up within two minutes or three minutes then you'd turn and go down and try to find it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Isn't every minute pretty important when you're dealing with a sub?

John E. Greenbacker:

That's right and I don't know why they had that kind of a sonar. Then you'd switch it. Once you knew were it was, you'd switch it and it went dead ahead. Generally if a submarine is making any kind of speed, you take a lead. If you take a lead with that equipment, you lose contact.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said in the last session that most of the Americans were afraid of the 1472, because of the gasoline engines. Do you know whether the British had had any major problems using that type of a vessel?

John E. Greenbacker:

I don't think they got much use out of it as an ASW vessel. They used it when there was a raid that was made on breast, special forces. They'd use one of those

fairmiles or two or three of those fairmiles to take them in. They were speedy. They were faster than ours, but when we got down to Miami where I was detached, they had us in a special ______ place and there were guards around, because they were so scared of gasoline driven vessels. They weren't as effective as our sub-chasers as anti-submarine... One of the biggest things you can do in anti-submarine warfare is just be there to keep that submarine down. So, if you have enough of these small vessels, they do serve a purpose even though they're not very effective the way a destroyer escort would be.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your stay on it was rather brief, I believe, was it not, just a few months?

John E. Greenbacker:

Just a few months. The people that preceded us, I think we got a total of six of those. We got down to Boston and found out they were going to take off the two-pounder which was a much better gun than our three-inch twenty three, which had so slow a speed that if you wanted to fire a star shell, it took something like forty-five seconds for it to get out where the star shell would light up. They got down to New York and they were going to take our sterns. We had this nice electric steering system. They took that off and put cables on, going down the side _______. That's when I took the beautiful steering wheel that we had and put in a cruise box and shipped it off home. Then they came around and wanted it. Somebody wanted to have it, but I still have that in the office. I didn't stop at Norfolk. One of the first ones that went into Norfolk had cut off their sonar gear running it aground. I went straight to Charleston, South Carolina and then from there to Miami. When I got to Miami, I was detached and sent to the STEWART, which was the first destroyer escort built by the Brown Bros., who had not been in the ship building business at all. The Brown Brothers that put concrete capping on the locks of the Panama Canal.

That's the sort of work they did. They opened up... twice as many man hours...at least in their initial as it did over in the one over on the border of Louisiana.

Donald R. Lennon:

Lack of experience, huh?

John E. Greenbacker:

Yeah. Well, they'd never done anything like this before.

Donald R. Lennon:

With the 1472, I presume that they stripped it of its power steering and everything as a precaution against the power steering going out or the ship being damaged or something.

John E. Greenbacker:

That was the argument these people made. My reaction was these skippers really didn't want to go to sea. As a matter of fact, when they were in New York, one of the tricks they pulled was to say they needed people and they couldn't go to sea safely with the crew that they had. They didn't succeed with that. Somebody told them to get the hell out of here. They were always finding reasons for not operating.

I went to Houston and got there in February of 1943 and that ship didn't go into commission until something like the first of June. It took it that long to build it. We didn't have anything operational. I was the executive officer. We went through refresher training, shake down training in Bermuda and I guess I left there sometime in August or the first in September and went to the ship building over there... I can't think of it. They were professional ship builders. They built ships on the west coast. I was only there for four weeks before we went in commission. My executive officer was Virgil J. _____ who is one of our skippers. He and I and I think the chief engineer were the only ones that had ever been to sea at all. I know that in some of those cases, the captain and the exec. would stand off and on watches. I didn't do that. I said, “You get on out there, you be officer of the deck. Call me if there are any questions. Call me if you sight anything.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Is this the STEWART or had you left the STEWART?

John E. Greenbacker:

I left the STEWART. This was the _______.

Donald R. Lennon:

With the STEWART, you were just there while it was being constructed.

John E. Greenbacker:

And went through shakedown training at Bermuda. At that point... There was a little bit more to that, why I didn't stay with the STEWART. Ordinarily, when the skipper went off to put a new ship in commission, the exec. fleeted up. We were down in Miami and the skipper of the sub-chasing training center decided he didn't want to have a lieutenant as commanding officer of a school ship. We thought I was going to be down there with the school ship and she was so pregnant with our first child that the doctor wasn't too enthusiastic about her having a long train ride. As it turned out, she was down there by herself. He wanted the skipper to stay on and wanted me to go off to another ship. Some of the students were fairly senior, up to the grade of commander. My skipper was a lieutenant commander so he went along with that. I got sent off to Texas again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why would they be sending men with that rank to DE school?

John E. Greenbacker:

When do they somebody more senior?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

John E. Greenbacker:

I guess its because with these senior people aboard, if something came up, he felt that there would be an awkwardness in whether or not a senior student could...

Donald R. Lennon:

I mean, why were these senior students in school.... This was a training school for DE's?

John E. Greenbacker:

Well, it was a training school for sub-chasers and they continued to send then through, and DE's.

Donald R. Lennon:

Normal rank for a sub-chaser commander was what?

John E. Greenbacker:

The normal rank for a sub-chaser would be lieutenant, but a lieutenant commander for the destroyer escorts. Captain Holloway, later Admiral Holloway, ran an outfit in Bermuda and he said, “You people are now in major war vessels and I don't want to see anyone with a sub-chaser manual out here.” He didn't care for a lot of the things they were teaching. For one thing, most of the people that were instructors down there also didn't have any experience. They went through a lot of basic stuff, trying to teach them how to go to sea.

After I left the STEWART, I went off to Texas and picked up the NUNSER(?) DE-150. I made these people go up to stand their watches even though they hadn't been at sea before and told them to just call me and I think that's the best way to train people rather to have the skipper and exec. The exec., as I said, was Virgil J.(?) and he relieved me... It was about May.

Then I went back to sub-chaser school again and went down to the sonar school or anti-submarine school in Key West.

Donald R. Lennon:

On the NUNSER, primarily what was it's function? What was the NUNSER doing?

John E. Greenbacker:

The NUNSER, during this time I was there, we were assigned to... First thing we did after shakedown, they sent us up to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, crossed over at the air station. The problem that they were having was that the Germans had developed a honing torpedo that would hone on the sound of the propellers. They were trying to develop something to trail behind the ship. The problem was that they didn't know what frequency the German's honing torpedoes would do. We were up there experimenting with all sorts of things. As a matter of fact, Dick Snow wrote a sketch showing trailing

this organ(?) behind and somebody sitting back in the fan tail ______ and all these torpedoes were dancing up and down back on the... That got published as a matter of fact in the anti-submarine newsletter, whatever they called it. Then we were assigned to escort a regular convoy, about seventy-five ships. We went as far as Gilbraltar and then broke off and went down to Casablanca. I thought I had a submarine contact at one point, but apparently there was nothing there, so it was uneventful.

One of the most amusing things that happened was, the night before we got to Gilbraltar, the sea was just absolutely flat and I don't know if you've ever seen the porpoises at night, because they're fluorescent and here were these two porpoises heading for us and we looked out.... They could have very easily have been a couple of torpedoes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I wonder how many porpoises were torpedoed during World War II.

John E. Greenbacker:

There was a lot of activity with whales. You'd get a contact on a whale. The porpoises were a little bit on the small side, but the whales took a lot of beating, I'm sure.

Then, I got assigned... I didn't come back with that convoy. The convoys were very well run, unlike the Pacific, which I'll get to. They were very well organized, kept closed up and if anybody straggled, which we didn't have anybody straggle, they were told to get away, so German submarines couldn't detect them and find out how to get up to the convoy.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many ships usually made up your convoys as far as DE's and Destroyers...?

John E. Greenbacker: