| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #119 | |

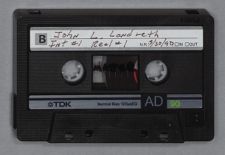

| Commander John L. Landreth | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 (DECO) | |

| March 30, 1990 | |

| PRIVATE Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, let's start with your background--where you came from, what your childhood was like, and how you became interested in the Naval Academy.

John L. Landreth:

I was born in Whittier, California. My mother was born there and my father came there when he was two years old. My grandfather, my father's father, was one of the founding members of Whittier. A company called Pickering Land and Water Company founded Whittier. It was a Quaker community. My grandfather was the only non-Quaker in the group. I guess they just had him for the money.

My father went into business for himself when he was nineteen years old. He was in the feed business. It was an agricultural community. My father only went to the ninth grade and became a court reporter at first before he went into business for himself. He was not very much interested in academic kinds of things.

In those days, not very many people graduated from high school. My mother was one of the first graduates of Whittier High School. Her mother didn't really particularly want her to go and, since she lived out in the country, she had to get a ride in with one of the

teachers. Her mother did not encourage her to do it. She was a graduate and she would have liked to have gone to college, but her mother would only send her to business college and not to a regular college. She was interested in literature and that kind of thing. When she was married, she bought all these sets of college books and had bookcases all over the house filled with this sort of thing. I had one brother nineteen months younger than I. She was very interested in our academic success.

When I went to high school, two things happened to me as a freshman that had a long-term impact on my life. One is that they offered an extra half-unit course beyond the regular four-unit course, in what they called “Oral Expression.” I took that course and ended up majoring in dramatics, because I took two years of that and then I took two years of dramatics. I ended up a “star actor,” and I got so many parts that the principal of the school finally required that I not be put in any more!

The other thing that happened was a little strange because I was a complete non-athlete. I weighed eighty-seven pounds in grammar school. If they had nine people for baseball, I played right field. If they had ten, I sat on the bench! I had a friend that lived across the street from me and we walked to school together. One day when I started to walk home with him, he said, “I'm not going home today. I'm going out for wrestling.”

The wrestling place was on the way home and I was kind of stunned, having my routine broken up. So I walked with him as far as the gym and then I started to walk away. The coach said, “Where are you going?”

I said, “Sir, I'm going home.”

Well he would absolutely not let me go. He didn't use force, but he just was persistent. I got in there and he got me all signed up. I kept coming.

An unusual circumstance occurred that made a big difference in my life in wrestling. This friend of mine, who was a heavyweight, was requested by the team captain, who had a lead in a Shakespearean play, to work out with him after the play rehearsal was over. I ended up staying with my friend from 2:30 in the afternoon until 7:30 at night. At 5:00, all the regular people had gone, but the old people who were graduates and had wrestled before, would come down and work out. I had two work-outs. As a matter of fact, I got home about eight o'clock and I couldn't even eat, I was so tired. I never went through a single night without having leg cramps.

Donald R. Lennon:

And initially you really weren't that interested in wrestling?

John L. Landreth:

Initially, not at all. I didn't want to do it. Well, of course, with all this practice, I became good at it, and then I began to be successful. I ended up as one of only three people to win the Southern California Wrestling Championship three years in a row! Then I became Southwestern AAU Champion. Years afterwards I found out why the coach wouldn't let me go: It was because I was small. Small people are hard to come by in wrestling.

So those were two strong influences on my life. Actually, the wrestling caused almost everything to happen to me, including the Naval Academy and including the . I was one of only three freshmen to get into the Varsity Club, instead of being a non-athlete and not having a varsity sweater, I became well known in high school. When the time came up for elections, in my junior year, I was elected to be the assistant editor of the yearbook and then became editor of the yearbook. When I was about ready to be graduated from high school I had no interest in the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Probably hadn't even heard of it, had you?

John L. Landreth:

At most, I maybe had heard of it. I was just about ready to graduate, probably in May, when the wrestling coach said to me, “Why don't you go to the Naval Academy?”

And I thought about it and I said, “Well, that's not a bad idea.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he have some friend or contact inside the Academy that was looking out for wrestlers?

John L. Landreth:

Well, that's a long story and I think we ought to cut it down. Yes, there was a particular reason why he said this. This is a fascinating story--one of the most interesting stories of all times.

Two years ahead of me in high school was a boy [Heber Player] who became captain of the Naval Academy wrestling team and also star football player. He took five years to get through high school. When he graduated from high school, his stepfather took him on a tour of the United States. One of the places he went was to the Naval Academy. And Heber Player looked at the Naval Academy and said, “I've never wanted to do anything else in my life, but I want to come to this place.”

So he went back to the high school and went to the guidance director, Dr. Jones. Dr. Jones said, “Why Heber, our best students can't even get into the Naval Academy. You have absolutely no chance of getting into the Naval Academy at all.”

Then he went to the principal and the principal said, “Dr. Jones has told you.”

So then he went to the wrestling coach, “Wag.” Well “Wag” had one of the most fascinating policies that I have ever known. He wouldn't do anything for anybody that they could do for themselves, but he would do anything that they couldn't do for themselves. He had almost never heard of the Naval Academy, but he said, “Heber, what Dr. Jones tells you is probably right. But if you really want me to look into it, I will.”

So he started out and the combination of those two people got him into the Naval Academy where he had no business being--from an academic standing. He had a terrible struggle. He got in on a football scholarship, you see.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he didn't have to take the competitive exam?

John L. Landreth:

He didn't have to take the competitive exam. You see football is the main thing and if the Naval Academy scouts put their finger on you, they'll find a way to get you in. [Edgar] “Rip” Miller was one of the “Seven Mules” from the Notre Dame team [1924] recruiting. They had people all over the country. There was also a 1922 Naval Academy graduate named Stacy, and he worked for Wilson Sporting Goods, and he kept his eye on him.

Heber was not appointed from California; he was appointed from Nevada. They would get somebody they wanted and then find places where they could use them. He had a third alternate or something like that. The first guy failed the physical and the next two couldn't pass the test so he got in.

He had a terrible time staying in--just pure guts. He not only got in, he stayed in. His favorite sport was lacrosse after he got to the Naval Academy. He was only eligible to play lacrosse when he was a senior because he was academically unsatisfactory all the other seasons. They'd spend that time getting him academically satisfactory so he could play football, which is what they were interested in.

Donald R. Lennon:

But he never washed out?

John L. Landreth:

He never washed out. First class year he did pretty well because everybody else kind of relaxed and he didn't know what the word relaxation meant. He made All-

American lacrosse the one year he played. He only played it one year and he made All-American.

But that was the reason the coach suggested the Academy to me, because he knew that Heber was completely not qualified at all to go but I was, he considered, highly qualified. That's why he asked me if I wanted to go. That's the reason that I went.

I had a very hard time getting an appointment and thought I was not going to get in at all. They were not interested in wrestlers. So I couldn't go in through that route. I was finished with high school and I had given up on it and was pursuing my other idea of going to the University of California at Berkeley. I had planned to go there the next year. All of a sudden at a physical examination, a boy from our congressional district failed out of the Naval Academy in February. The system is that each congressman can have so many people at the Academy. All of a sudden, my congressman had an opening.

On about a week's notice, I had to take a competitive examination, which he [my congressman] gave. For that time, he was a remarkable man. His name was Voorhis, an idealistic congressman from California. He was beaten out later by Nixon, but he spent about sixteen years in Congress. He was an idealistic kind of individual. He took the top five people out of the competitive exam and had his assistant out there examine in detail each of these people. He took these people and their records and picked out and ranked them in order on the basis of those that he thought would be most suitable to make naval officers. My family was all Republican and he was a Democrat, but he appointed me because I came out the head of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just think, if you had gone to Berkeley, you may have wound up on Broadway as a professional actor! Do you ever think of that?

John L. Landreth:

Well, yes, you know you always think about that. More likely I would have ended up as a movie director or in that field, but you know, you always think of that kind of thing when you look back.

So that's the background and that's why I went to the Naval Academy. I claim that nobody is qualified to go to the Naval Academy because they have so many requirements. If you're good academically, then they have all these physical things that you have to do--all this swimming and you name it. I claim that nobody is qualified, but I was probably the most unqualified person to go to the Naval Academy that there was. I was not qualified academically. Fortunately, I had reasonable math aptitude--not like Jim Jamison, who stood number one in that. I hadn't had much math, you see, because I hadn't planned on anything like this. That was one reason I wasn't academically . . . I hadn't taken the right subjects when I went to junior college. I ended up with an English major because I took dramatics and English and all that kind of stuff. But also I had never been a Boy Scout and I couldn't tie knots and I couldn't shoot rifles and all that kind of thing. Plebe year, people used to gather around my room when we'd come back from something and ask what had happened to me today because some catastrophe happened every single day!

But in spite of all those kinds of things, I was highly successful at the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kinds of things went wrong?

John L. Landreth:

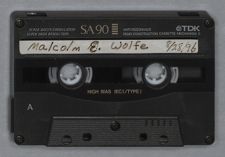

Well, I'll tell you, we had a boy in my class named Malcolm. And Malcolm had had a commission in the Army before he came to the Naval Academy, but he had the misfortune to get next to me in the rear rank of a marching squad. When they say, “Squads right,” you're supposed to turn left . . . I would turn right . . . and it was like a Laurel and Hardy

movie, I would run right into him and we would both fall down and our leggings would catch. He had a hard time in the infantry because he got next to me.

The other thing that happened to me was on the rifle range. They have four days of preparation--dummy stuff--before you shoot. Those are the worst days, supposedly, and the worst day is the fourth day. I got through all of this and I got on the rifle range. I think I was shooting at the wrong target, which was one of the problems I had. A Marine officer came up and said, “Are you squeezing the trigger?”

“Oh, yes sir, I'm squeezing the trigger.”

He had this trick. He said, “Okay, I'll load this gun and I want you to fire it again.” He opened it and you'd see that shell going in there, but in truth he didn't put a shell in there. Then when I would get ready on the trigger, I'd pull right. He'd say, “See, you pulled.”

I guess two or three times he did that and I jumped every time so he sent me back to fourth day. Then they wouldn't promote me out of fourth day anymore. I spent most of my time during plebe summer in this fourth day instruction. Once in a while they'd send me back to the range and then I'd get sent right back again. Finally, I was well-known to all of the officers on the rifle range. Anyway, they took me up and put me at the end of the whole line and they assigned one gunner's mate just to me. The gunner's mate tried to do all this stuff and he finally went and got this Marine officer. The Marine officer came up and they found out my arm was too short for the standard rifle. So the Marine officer said, “They'll either have to change the butt of the rifle or you're not going to be able to shoot this rifle. They're not going to change the butt of the rifle.”

Well, I finally made marksman, but it took me all summer and most guys just whip through this and they're up in sharpshooter's range. I got up into sharpshooter's range and this Marine officer saw me coming back one day. He said, “Where are you coming from?”

And I said, “Sharpshooter's range, sir.”

He said, “How in the devil did you ever get up there?”

It was all that kind of thing. I had big trouble with anything that had to do with any of those practical kinds of things.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you think of the type of instruction that you got at the Academy--the style of teaching they used there?

John L. Landreth:

Are you talking about the practical or the academic part?

Donald R. Lennon:

The academic part.

John L. Landreth:

Well, I was unsuited to the academic center that they have at the Naval Academy because I had an IQ of about 119, which was not too great. The reason I had always gotten As was that I put a little more time in than other people. At the Naval Academy, I couldn't put in any extra time so I was not very well suited to it. I didn't like it too well because once again, I liked to master a thing. I like to really have a feeling I know a subject. There, I didn't have the time to master too much, I just tried to survive from day to day. I didn't come away feeling I knew anything. Once I got involved in the Fleet, however, I found all that stuff came back to me--I had more knowledge than I thought I really had--it was a pretty good system. Now, I think that for 80 percent of the midshipmen, the kind of instruction that they use is probably better than any other because we would sit down and study for an hour and then go ahead and take a test. Most people would not have sat down for that hour. So they crammed a lot of

stuff into us in a short period. I think that they probably crammed more stuff into us than if they had used some other kind of system.

One of the things that I didn't like about the academic system was that probably only 1 percent of the midshipmen were able to finish an examination. For somebody like me I just didn't have enough time unless I really raced through it, so I never finished any exams. The only exam that I ever finished was one in electrical engineering and alternating current. They changed their policy for that one and gave us two hours, when we could have done the whole test in an hour. I finished in an hour and went back and worked all the problems again, so I stood about three in the exam. I would have liked a little more time for the exams. But once again, the Naval Academy system was good not only for the knowledge it gave us but also because we had to learn this stuff from the books. We didn't get a lot of help. That's what happened when we went out to the Fleet. We'd get a director book.

Donald R. Lennon:

And there's nobody there to instruct you.

John L. Landreth:

There's nobody there. We were on our own. This is the way we picked it up. I think that it probably is a pretty good way to train people to be naval officers.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about your plebe year--the harassment from the upper classmen?

John L. Landreth:

Well, that was kind of funny because in high school I once was tried for insubordination, in connection with the yearbook. I was in an elected position and I felt the advisor was supposed to be only an advisor and not a dictator. I got tried for insubordination because, as the editor, I did things that I didn't get her approval for, and she didn't like some of the things that I did. I was found not guilty, so the civics professor said, “Well, Johnny Landreth is okay, but he's a 'Red!'” I guess those kind of people were predicting that I would have a hard time at the Naval Academy.

Something that I can't understand is somebody going to the Naval Academy and then quitting because the discipline is too hard. This happened to a boy recently. When you go there, it seems to me, you know that it's going to be a disciplinary kind of place.

For me, that year was a terribly long year. I got tired of it. Plebe year one doesn't have much relief from a lot of the stuff. I was really glad when it was over from that standpoint. But I didn't get hazed much. One of the reasons was maybe because I was small.

I never really passed either the weight or height test to get into the Naval Academy. I knew that you had to weigh 125 pounds to get into the Academy and I only weighed about 115. My father had a different doctor from mine and he mentioned this to Dr. Charlton. They were close friends, and Dr. Charlton was a kind of experimental guy. He said, “Oh, I think I can get him up to 125 pounds.” They gave me insulin shots and this special diet. I couldn't eat anything that wasn't fattening. I carried a chocolate bar around in my pocket in case I started to shake.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't that dangerous?

John L. Landreth:

Maybe. I don't know. I don't think so. Anyway, he got me up to 125 pounds, but I lost three pounds when traveling to the Naval Academy. The height requirement at the Naval Academy was 5' 5”. I had this terribly interesting experience of getting through the Naval Academy physical. I could just barely make 5' 5 ”. A corpsman gave me this height test and he said, “You're too short. The requirement is 5' 6”.”

I said, “I thought it was 5' 5.”.” I had no money, no way to get home--nothing. If I had come all the way to find that the requirement was more than I thought it was, I was going to die. So I insisted.

He said, “You're underweight and you're under height.” So I talked to him enough so he was willing to go back and check with somebody on it.

Well, I waited there a period that seemed interminable to me. It might have been half an hour or forty-five minutes, I don't know. But finally this young doctor came out, and he said, “What seems to be the problem here?” Well, the first thing he said was, “Are you Landreth?”

I said, “Yes sir.”

He said, “Are you some kind of an athlete?”

I said, “Yes sir.”

Apparently during the physicals, the doctors had lists of the athletes coming in. If they were going to fail, they wanted to make sure that two or three people had agreed on failure. So he says, “Landreth, what seems to be the trouble?”

I said, “Well, all my information was I had to be 5' 5 ” and this man says I have to be 5' 6”.”

He said, “Oh, 5' 5 ” is the requirement. This chart here says 5' 6” but that's for the weight. That's just weight for height.”

Well, the corpsman had fortunately written 5' 5” on the sheet. So he looked and said, “5' 5,” you're okay. And on the weight, we allow 10 percent for travel.” I didn't have to take that insulin or that other stuff!

Then I went over and took the heart test and my pulse was high. I had to come back the next day because I was so concerned about all that. I thought I would just go through that floor when that guy said you had to be 5' 6”.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, were you actually 5' 5 ”?

John L. Landreth:

Well, I was going to tell you, I don't know. But I tell you that I never passed a height test again. The next year I was 5' 5 3/8”. And the next year I was 5' 5”.

Donald R. Lennon:

Shrank!

John L. Landreth:

Yeah! To get a commission, I think you had to be 5' 6”. So I went up and I flunked my height test and the doctor said, “Okay, I want you to come up here every morning at reveille. This corpsman will take your height. I want you to come up here every morning until you pass this test.” Well, you're a little taller in the morning when you first get up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are you really? I didn't know that.

John L. Landreth:

Yes. As a matter of fact, you can increase your height by quite a bit. They did it to a boy later on, a wrestler, who was shorter than I was. They suspended him by his legs for three or four hours and when he'd get up to the right height, they'd rush him over. You can make yourself taller by letting your weight hang down.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've never heard that before.

John L. Landreth:

So anyway, I went up there three or four days. Of course this corpsman couldn't care less; he was sleepy-eyed and it was six o'clock in the morning. Finally, I just put on some real thick socks and another pair and then “5' 6” you pass.” Later I became 5' 6” out in the Fleet, but that was my experience at the Academy with the height and weight.

The fact that I was small was a substantial advantage to me in wrestling at the Academy just as it had been in high school. I was the first person to be four times Academy champion in wrestling because it was almost impossible for them to get anybody in those lower weights. You had to weigh more than those lower weights to get into the Academy, so they had a hard time. Even then it was difficult to find somebody who had already wrestled. There was a guy who was a first classman on the wrestling team, and this guy was

really bad. I don't think he ever won a match. He was just terrible. At the end of plebe year, the old coach said, “Do you want to challenge 'Mug,' for the championship?”

I said, “Sure.” But “Mug” forfeited. He wouldn't wrestle me because he knew I could beat him and he didn't want a first classman to be beaten by a plebe. So I became the first person to be four-time champion because most people who come to the Academy haven't wrestled before.

In this hazing stuff, one of the principle things was to make someone do forty-one push-ups. Well, those guys would ask me to do forty-one push-ups and when I got to forty-one, I just kept on going because it was good exercise. I was not fun for these guys, so they stopped asking me to do that because it didn't pain me any. The hazing at the table, I don't know, I just accepted that.

Donald R. Lennon:

You never had to get under that table, I take it--”Sit on air?”

John L. Landreth:

Oh yeah, I “sat on air.” But you see, I could “sit on air” pretty well. As a matter of fact, I'm assistant coach at the Maryland Olympic Wrestling Club now, and the coach makes the young guys “sit on air” to exercise their legs. So, “sitting on air” was not too hard for me. I never collapsed. I don't think I did it a lot of times though. That didn't bother me. Anyway, the hazing part never really bothered me.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular incidents from your Academy days that stand out in your mind, either good or bad?

John L. Landreth:

Well, of course, the reason I was elected editor of the yearbook . . . and once again this all has to do with wrestling. I had been an editor of two yearbooks and assistant editor of the same two yearbooks before I came to the Academy, so I had a lot of experience, but there was a little problem--they elected the editor. Now when we were there, the Fourth

Battalion had two more people in our class than any other battalion. When any election came along, they would decide who they wanted and then require everybody in the Class of '41 in their battalion to vote for them, so they always won. They won all the class offices for all four years. We were familiar with that. So what we did on the election when it came up was to get the Third Battalion and the First Battalion together. The Third Battalion nominated the editor and the First Battalion nominated the business manager, so the Fourth Battalion didn't win anything in that particular election. So that was a little skullduggery there.

Probably the best thing I ever did in my whole life was the job I did with the 1941 . It turned out to be the number one yearbook in the country that year. They don't really pick a number one yearbook but they pick the ten best. Out of the ten best, the had more points than any of the others. I didn't have to do much work at all on that. That was the easiest job I ever had.

The first time I was editor of a yearbook I picked all my friends and all these people to work with me. The more I worked on yearbooks, the less I picked friends to help.

Donald R. Lennon:

Leave you to do the work?

John L. Landreth:

At the Naval Academy, our time was foreshortened, so we had to do everything faster. I just picked the best people that I could find. Some of them I didn't even know, I just knew they were great. I got them together and said, “We've got a short time to do this. If it's not moving along, I'm going to change people. If it's not moving along, I can't fool around, I've got to change people.”

Well I laid down the design of the . I had four associate editors--one for each section. Then I had a copy editor, Joe Materi, and all the copy went to him. Nothing

even came to me--I'm not a writer. Now most other editors at the Academy had written, like the Class of '40 member, Bill Lanier, who was a really good writer. He came from a Southern writing family and he was really fantastic. Well, he tried to write the whole thing himself! He got in all kinds of trouble and worked and slaved, and you know, I didn't do anything. I didn't even see this stuff. All these guys got it in on time. I'd set up a schedule when the stuff was due and what it was supposed to look like, and they just put it together. All the copy went to Joe Materi who checked all the copy through to see if it was right.

We're doing this fifty-year yearbook. I'm a consultant for Jim Jamison, who was an assistant editor of the Class of '41 I made Jim do it. He would only agree to edit the fifty-year yearbook if I agreed to be a consultant. So I'm a consultant for the thing. But anyway, the 1941 just came out absolutely splendidly. That was probably my peak!

The other peak that I had came a long time later in directing. You're probably not interested in that one, but it was kind of the same thing. I seemed to luck into some of these things.

Getting back to my Academy experiences, a really amazing thing happened that is sort of interesting from a Naval Academy standpoint. I found out very soon that they liked shoes that were well-shined, so I kept one pair of shoes just to go to formations in. I kept those really top-drawer. One day the company officer came through on a dinner meal formation or an inspection or something. Behind him came the midshipman battalion commander, then the midshipman company commander, and finally all these midshipmen officers. So Lieutenant Adair came by. He looked down at my shoes and said, “Good shine. What's your name?”

I said, “Landreth, sir.”

He said, “Landreth, that's a good shine you've got.” Well, each one of these guys came by and they all said, “Good shine.”

These midshipmen officers had to do aptitude marks. So when they came to my name, they always remembered there was something good about me. They didn't know one person from a howdy-do to give aptitude marks for these crazy plebes. Anyway, I started getting high aptitude marks and once you start getting high aptitude marks, unless you do something to change it, it just stays the same. I stood one in aptitude for first-class year.

On the first-class cruise they have a head midshipman and if you are high in aptitude, you get picked. They had a different one every two weeks, so I got picked as one of those people. I had had a shot at the last one, so I knew I was going to get it. I noticed that the guys that had this job spent their whole time making out their watch bill. So before I got the job, we went into Necrude(?) and into San Juan, and I just stayed aboard ship and made out the watch bill for my whole two weeks. It was all done. I also had seen that each one of these guys had two “messengers”--two plebes, two youngsters--as assistants. Well, I kept my eye on the people that did that job and I picked out two guys I wanted. I got these two guys who were really top-notch top-drawer guys, so then I was able to just go around and do anything I wanted to, because the stuff was all taken care of. I did run into some kind of problem with clothes--I've forgotten what it was--but I don't think I did any good for the problem. Even so, I came out doing a better job than anybody else because I had done a lot of preparation for the work. So on the , I got number one in aptitude.

Commander Wright, a senior battalion officer, was the officer representing the They didn't have many commanders--mostly lieutenant commanders and

lieutenants. He called me up when we came back and said, “I don't know how to tell you this, but you got really high aptitude and should have a really high-ranking midshipman position. However, you don't fit in any staff.” They wanted these guys all six feet tall.

I said, “Commander, I understand that. That's no problem to me. I've got the to take care of. I've got my time fully occupied as you know. So that's no problem to me.”

If I had gotten to be a four-stripe or something like that, I would have had to have performed--all those guys were in there competing--but I didn't have to do that. I was a platoon commander, but I didn't go to the platoon most of the time because I was working on the . I wouldn't go to parades and all that kind of stuff, but they would give me these high marks. They said, “We have to give him those high marks because we've done him in!” I loved it because I was a not a very military kind of person anyway. So I ended up with high aptitude marks.

I was very regulation. I didn't do anything to break the rules. But another funny thing that happened was that the only demerits I got in my four years at the Academy--every one of them--was in association with Micky Weisner. For example, one time he was in a squad going to math and he broke out of the squad and was dancing around and cutting up. I ordered him to get back in the ranks and he wouldn't do it. This ODC didn't do anything to him, just to me, because I couldn't control my troops. Another time I came in late because he came in late. Every demerit I got was in conjunction with Micky Weisner who later became the only full admiral from the class. He was also small--my size--and he was in the fourth platoon.

When we graduated, they gave letters of commendation to six midshipmen for the first time. As a result of having these high aptitude marks, being captain of the wrestling team, and being editor of the yearbook, they gave me one. Sheldon Kinney also received one. He was from South Pasadena, near Whittier. I got this letter of commendation based on all this. Normally those would have only been given to four- and five-stripers, but they made an exception in my case. Without doing any work, I got this nice letter of commendation.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't get into any acting while you were at the Academy did you?

John L. Landreth:

Oh no. I purposely absolutely stayed away from that because I was through with that. Acting is almost a disease. It's a compulsive kind of thing, so I just cut it off. Jim Bartlett, a friend of mine, was more inclined. You probably interviewed Jim Bartlett.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

John L. Landreth:

That Jim Bartlett was something else again. Anyway, Jim was head of the make-up gang. I went over and helped him put make-up on people but I never did any acting. Absolutely stayed away from that because that was behind me. Later on it stopped being behind me.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sounds like your Academy experience was very positive all the way around.

John L. Landreth:

It was a very positive experience for me because I was in wrestling. I was undefeated in the east for two years. Anyway things just went well for me except for some of the academics.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you graduated, your assignment was to the ?

John L. Landreth:

Yes. That was an interesting assignment because we were not permitted to put in for ships. In previous classes, they all had gone to battleships. It was really another two

years of training. But they sent our class to all kinds of ships: Jim Jamison went directly to a destroyer and so did Sheldon Kinney. This was a change, I think. They did it differently in our class.

We went to all kinds of ships. They spread us out all over. We had priority numbers--we drew them out of a hat or something. We were not permitted to specify a ship that we wanted, only what type of ship. I wanted to go to the because the was a wrestling ship. I had wrestled against them when I was out on the West Coast. These guys had terrific wrestlers on that ship. I wanted to go to it. So I specified battleships and then I put in parentheses “USS .” Probably nobody else put that, so they said, “Why not? What difference does it make?” So I got the ship I wanted.

When I got out there, they hadn't been doing much wrestling for a while. They had two or three guys around who had wrestled. They had one guy, Denver Jenkins, who had something like eight or nine Fleet belts. This guy was an Olympic-caliber wrestler, a fantastic wrestler. We decided when I went out there, “Let's get a good team together.”

Well, we didn't have too many people for the team, so I decided that we'd have a big inter-ship, inter-division tournament to find some. We'd pick some guys out from that contest and get them on this team.

So we started that. The division petty officers didn't like their people to go into athletics because they'd lose them and they wouldn't get as much work out of them. They showed some reluctance so I mounted a big campaign. I got a guy who was a cartoonist and put up big signs all over. Then I'd go to one of the petty officers and say, “Guys over in the E Division say they've got a kid that can lick this kid here. Just clean him. Is this true?”

And this guy would say, “Nobody will clean my guy.”

And then I'd go to E Division's petty officer and I'd say the same thing about their guy. We had a fantastic tournament! We had over a hundred guys, I guess, in this tournament. Denver and I coached all these beginners for about two weeks before the tournament started.

On the first night we had these competitions, we were on the starboard side of the ship. On the portside, they were having a movie. There were only about three people watching the wrestling; everybody was at the movies. By the finals, there were only three people watching the movies and everybody was over watching wrestling!

After that we got a team together. We won everything. In any one match we never lost more than two weights. Very often, we'd take all of them. Sometimes we would lose one and once or twice, we lost two. Denver was a little bigger, so he took all the guys forty-five and up, and I took all the little guys. Then the dirty Japs came in and ruined our good team. Split it up.

Donald R. Lennon:

What position were you appointed to when you arrived on the for your duty?

John L. Landreth:

I was in the anti-aircraft division. Almost everybody was put into gunnery. There were five people from the Class of '41 that went onto the , and only one was not put into gunnery. Three of us were put into anti-aircraft gunnery, because that was the thing that was coming up. They took millions of people in the anti-aircraft division. I think I was in the Sixth Division. I think I was the eighth junior officer in that division or something. They really strung it out.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the doing during the summer and fall of forty-one? Maneuvers? Alone or in company?

John L. Landreth:

No, battleships don't go alone. We were in Pearl Harbor and we'd go out and maneuver a little bit and then come back. As a matter of fact, I didn't join the in Pearl Harbor. She had been in Bremerton for some work and then on our way to Pearl Harbor, she came to Long Beach. I joined her in Long Beach. Then we got out there and cruised around a little bit and did a few things.

Donald R. Lennon:

During the summer of forty-one, the work wasn't so intensive that you didn't have time for wrestling and other activities?

John L. Landreth:

I never was in better shape in my life. Denver and I went out at 2:30 every afternoon and didn't quit until 6:00. I used to wrestle Denver a lot. The ship had this funny doctor. When I took my first physical, this guy was listening to my blood pressure. He kept listening and listening, and he finally looked at me and said, “You're dead.” My blood pressure was so low, because I had gotten down so much--I was in a terrific kind of condition.

We were not that busy anyway that we couldn't take on other activities. When I was a wrestling coach, that was a duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was part of your duty?

John L. Landreth:

I got myself assigned to it. What happened was that they got a new executive officer aboard who was a “mustang.” [A “mustang” was a naval officer who did not graduate from the Naval Academy--an enlisted man--but rose up through the ranks and became an officer based on his own achievements.] He got all the officers together and said that he wanted the to be outstanding in any way that we could make it outstanding. New ensigns are junior to any third-class petty officer, they give them a bad time; so I was the lowest of the low. But when the meeting was over, I went up and said,

“Commander, I am interested in that remark that you wanted to be best in any kind of area, because the has a long-term history in wrestling. It hasn't been too active recently, but we could really work it up.”

He said, “Oh, I want to do it. You tell me whatever you need.”

I got medals for these guys at this ship's tournament. There was plenty of time for that kind of thing. I don't think we worked beyond about four o'clock.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then came December the seventh.

John L. Landreth:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you get into that?

John L. Landreth:

Yes. I got into it. Actually , . . and this is interesting . . . from the Class of '41, there were five of us that went aboard the NEVADA. But one of us--the one that wanted communications--went to radar school, and he was not there December seventh. He was back at Bangor, at Bowdoin, where they had a radar school. So the four of us were all aboard. There was no other class that had more then one person aboard. We were all aboard ship that morning. I presume you've interviewed Joe Taussig?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

John L. Landreth:

Joe Taussig was there. Chuck Merdinger was there. He was in fire control, main battery fire control, down in the bowels of the ship. You probably haven't talked to Chuck, because he's out on the West Coast. He was later a Rhodes Scholar and had a fascinating career. He ended up in the Civil Engineering Corps. Joe, Bob, and I were all in the anti-aircraft division. Of all the officers aboard the in the anti-aircraft division, I was the only one that didn't go to the hospital.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you doing that morning when the alarm went off?

John L. Landreth:

I was strolling leisurely into breakfast. So when the alarm went off, I began kind of cursing because it was Sunday morning, and they had been having these fire drills. I said, “You know, this is a low blow, having a fire drill Sunday morning.”

Donald R. Lennon:

So they had been having drills regularly?

John L. Landreth:

They had been having drills, but not on Sunday. They had stepped up these kinds of drills. I began half-heartedly loping, which is a good thing as it turned out. Joe was on the starboard anti-aircraft director and I was on the port one. We had the same jobs but different directors.

When I started coming out of the hatch to go up there, machine gun bullets were going right across it. If I had been two minutes earlier, I would have been machine-gunned. That's what happened to Joe. I'm pretty sure he got a machine gun bullet from that strafing. They came along and strafed first to clear the guns out, to clear the personnel, and then they came in with the torpedo planes.

So I was kind of loping along, but then somebody shouted, “It's the real thing! It's the real thing!” I stepped up my pace and got on up to my place.

Donald R. Lennon:

Between strafing?

John L. Landreth:

I think they just strafed once. And then they just started in with all the other stuff after I got up there in the director.

I was going to tell you a funny story. The Naval Academy has only had three wrestling coaches. My plebe year there, the old coach--the original coach--was still there. When I was a youngster they brought in a new coach, Ray Schwartz. I was the first Navy wrestler that wrestled for him because I was the first one out there. Ray said, (he said this to

a lot of people) “Sandy is going to be a good Naval officer because they'll have to shoot buckshot to get him!”

That turned out to be true--a five-hundred-pound bomb missed me by eleven inches! But as Joe said, I had a very good view of the whole situation. They had just put isinglass to replace the metal in the top so we could see. I hated that later on because I saw things I didn't want to see. But anyway, I could see everything. We were at the end of the line. I saw the turn over. I saw the blow up; she was right in front of us. Of course, I saw the torpedo planes come in.

The was in better shape than most of the ships because our gunnery officer was one of the toughest peacetime officers I have ever known. He was not too popular, but he was one of the best wartime commanders I have ever seen.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was that?

John L. Landreth:

Commander Robertson.

Well, there's another aspect of all of this that I'm going to interpose at this point. Just recently I've come to this conclusion. Joe Taussig knew what the Navy was about. I didn't know; Chuck Merdinger didn't know; most people didn't know. Joe's father had been crucified because he said we were going to be in a war with Japan if we didn't change Europe. So Joe was prepared. He knew there was a war coming. He was just waiting for the day. But for the rest of us, it was a shock. I never even thought about war. It's funny. I went to the Naval Academy and I didn't even think about war. It was just going to school and all that stuff; I never really thought about it.

Commander Robertson had apparently thought about war and was thinking about war, because the regulation was that we had to keep the firing locks for the guns down in

the ordnance, locked up, and we could only have just a little bit of ammunition. He had all of our ready boxes completely filled, with the firing locks already on the guns; so we started firing sooner than anybody else. As a matter of fact, the secondary battery, which was supposed to be used against surface vessels, shot a shell that landed in front of one torpedo plane, splashed water up on him, and he went down. The guy to the left of him saw what had happened so he turned off and delivered his torpedo to one of the other battleships. So we only got one torpedo. We were supposed to get three. We only got one.

Donald R. Lennon:

But Robertson was in violation of regulations.

John L. Landreth:

Complete violation. They never charged him, because we got to shooting with our five-inch twenty-five anti-aircraft guns, so we were shooting right away. Not much happened to the . We got the one torpedo plane hit. The commander of a high-altitude bomber said in an article that he didn't bomb the because it was covered by smoke. Not too much happened to us.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you take the hit from the torpedo?

John L. Landreth:

In the port bow. One torpedo is nothing in a battleship. So we didn't have any kind of problems until some smart guy decided that the should get underway.

It turned out that the Japanese dive bombers all had a primary target, but the secondary rule was, if anybody got underway, to divert the attack to the moving vessel.

So I'm sitting up there and these dive bombers started coming in at us. The first one went way over and the next one came way short. The next one was less over and the next one was less short. Pretty soon, they let one go that was right on our line of sight. It didn't veer in any direction. It came in and it had my name on it as far as I could tell. Everybody figured we were done. It was coming right at us. It didn't change direction at all. Well,

that's the one that went eleven inches away from me--right outside the director door. It was a time-delay bomb, so it went down to the protective deck and went off. It didn't cause any damage, however, when I stepped out of the director, I almost stepped into the hole it had made.

From that time on, from the time that they made the first hit on us, the ship never stopped rocking. The smoke would just begin to clear away and the ship would stop trembling a little bit, and they'd hit us again. Then it would start all over again.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you had stayed under the smoke of the , you probably would have taken very few hits, wouldn't you?

John L. Landreth:

Yes. We would have been in great shape if we had just stayed back there. But we didn't do it. We got underway, so we got a lot of hits and a lot of casualties.

Afterwards, one of the people in the director came up to me and said, “My God, but you're cool under fire. When that bomb was coming right at us you turned around and made a change in the setting in the director.” I turned around to make a change in the setting to keep from watching that thing hit me. That is what I was doing!

Donald R. Lennon:

There wasn't anything you could do about it.

John L. Landreth:

Wasn't anything I could do about it and I didn't want to watch it hit me! I was not brave. As a matter of fact, my feeling is that there are almost no heroes. Almost everybody just does whatever job they have to do. On the , they gave all officers who went to the hospital a Navy Cross, so I didn't get one.

There was a Reserve officer, Huttenburg, who was junior to us. He came aboard two or three months after we did and was in Joe Taussig's director. He was unscathed during the battle. When we started to take Joe out, I was trying to get them to take him over

the side, because it was a vertical ladder. We only had about this much clearance and getting that darn stretcher through there was a problem. Anyway, they were moving Joe, and Huttenburg had a hold of the end of the stretcher. He leaned up against the bulkhead, which was red hot from the fire in the navigation room, and burned his leg and went to the hospital. So the day they were going to give out these medals, “Hut” came up to me and said, “Somebody says I'm going to get a Navy Cross. Sandy, can that be true?”

I said, “There's no way it can be true!” But when they passed them out, he got a Navy Cross. He was a full lieutenant with a Navy Cross before he was twenty years old. He went into flight training and got to be a terrific aviator. He got all kinds of medals, was covered with glory, and ended up as a Marshal Air airplane pilot.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did Captain Taussig get hit by more than the strafing? Did he get another hit before it was over or was it all from that initial pass?

John L. Landreth:

There was a question of what hit him. All these guys have a Association. Recently when they got together, Joe stayed with Chuck Merdinger out in Lake Tahoe. They all did. They started talking about this stuff and concluded that it was a strafer that hit him, because there wasn't anything else. I thought he got hit with a fragment from a high-altitude bomb, but he got hit too soon. I have some questions about whether he ever got to the director or not. The next time I see Joe, I'm going to ask him or Huttenburg. He was just relieving the deck. Charlie Jenkins was still officer of the deck and Joe was getting ready to relieve him when all of this stuff happened. Joe sounded the alarm and then headed for his battle station. I think he got hit on the way up to his battle station. I'm not sure he ever got there. I don't know.

They had a director here and a director here and then they had a little repair shack right in between there. When the battle was over, that was where Joe was when I went in. Just the other night, he said (he says this, I guess, every time I see him), “I'll never forget the expression on your face when you came out and looked down and saw me lying there.”

Donald R. Lennon:

So he was lying there the entire battle.

John L. Landreth:

Yes, I think so.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's a wonder that he didn't bleed to death.

John L. Landreth:

He almost passed out when I was there. He lost a lot of blood because that wound was way up high.

Anyway, I walked in there and looked around. Then I walked out the door and looked down on our gun deck and it was just completely covered with bodies. There wasn't anything but bodies down there. I hadn't seen any of this because we had been looking up all the time. I didn't know what was going on. All I was doing was trying to shoot down airplanes!

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

John L. Landreth:

I went back in and we took Joe down. I finally went down and had to go across our gun deck to get out. I had to walk over all of these dead people. I remember I had a funny reaction to it. It was just, “My gosh, am I not lucky? I'm just lucky that I'm not one of these.”

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no fire on board the , I take it?

John L. Landreth:

Yes, there was fire. As soon as the battle was over, all the officers came back to the ship. There had been very few officers on board during the battle. Commander Robertson showed up. He had been around putting out fires. All those officers had been just going

like demons doing all this stuff. I hadn't done anything. I don't remember much. I remember going back and sitting down. I was numbed. I was just kind of out of it. Recently, I thought, “Why wasn't I fighting fires?” That didn't even occur to me. Of course, they had plenty of people.

Donald R. Lennon:

People who weren't actually in the battle itself.

John L. Landreth:

Yes, who weren't in there.

Donald R. Lennon:

How far down Battleship Row did the get when it was trying to make its sortie?

John L. Landreth:

I think all the way. I think we got past Battleship Row. I'm not really a very good one to ask that question. Once again, I was on the port side. All that stuff was on the starboard side. I read Prange's third book that came out, the one on Pearl Harbor. What a deal Prange had. He was the chief historian for MacArthur, so he was in Japan for about six years. He interviewed all the Japanese naval officers while he was over there. Then he came back and interviewed all kinds of other people. I read this stuff about observations that people on the made, about what they saw and everything, but I didn't see anything. It was on the starboard side. I really didn't see any of that. I don't think I remember even being underway. None of that had any meaning to me. All I was doing was looking up at planes.

When they came at us, I shot at them. And when they didn't, I kept looking for another one to shoot at. That's why I say, for somebody there, they really didn't know the full picture. I certainly didn't. This book, he calls it , takes place in one day, although there is a little bit on Saturday night. It's about what happened in

Washington and what happened at Pearl Harbor to both the Army and the Navy. It's got a lot of interesting material in it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course, I grew up as a kid reading Walter Lord's .

John L. Landreth:

Yeah, I've seen that. That's one of his quotes. But you know the thing that he quotes-- uses more than anything else in this third book--is the Roberts Commission testimony. I didn't even know he had published this book. The head coach at the Maryland Olympic Wrestling Club is a military history buff, a young guy, about thirty-two years old. He's a bank vice-president and he does this on the side. Anyway, I was over there and he ran up to me and said, “Do you know you're in the latest Prange book?”

I said, “I didn't even know Prange had another book out.” I had missed it somehow.

He said, “You're in there three or four times.” I couldn't figure out why in the dickens I was in there. But before I got out of the library, I figured it out. It was either the reports that we turned in or it was the Roberts Commission. It turned out to be the Roberts Commission. What had happened was the Roberts Commission did all their interrogating of all the people who were important in this thing, and then, the last thing on their agenda was to talk to some peons--enlisted people and very junior people. They sent a message over to the that they wanted a junior ensign from the The navigator came up to me and said, “I don't know of any ensign that is more junior than you are. You go.”

So I got to appear before the Roberts Commission. Prange got to use a lot of my quotes. Now I've gotten interested in it and I'm going over to the University of Maryland where they have it on microfiche.

Donald R. Lennon:

You're going to get a copy and see what you said?

John L. Landreth:

Yes. Read the film and see what else I said. But they have some of my best stories in there. I got pretty good coverage. I got better coverage then anyone in the Class of '41. Joe Taussig got really good coverage in the first book, but in this book he doesn't get much coverage because he didn't go before the Roberts Commmision. That's got me all livened up about all that stuff again. I've been over there already. I've got it located and now all I have to do is read it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once the fighting was over and the fire was extinguished, what happened after the numbness began to wear off?

John L. Landreth:

Well, I don't remember eating. I was trying to think of this because I did read this Prange book. I don't remember eating, or where we slept the first night. But the wasn't sunk. It was lowered onto a coral ledge by kingpost. Everything below the main deck was flooded, so there was no place to live on the . We continued to stand gun watches--that was all operative--but we stayed over in a building where they fed people there in Pearl. They took a top floor and just put in a lot of cots. We slept over there and stood the watches on the . One watch was from midnight until eight in the morning. That's where I first learned to drink coffee. We continued to work on the ship and stand gun watches.

Now I have a rule about battle: Never get caught in your own room in a battle. My room on the NEVADA was hit by a dive bomber at Pearl Harbor. On the , we got shrapnel that went right through my room, right through one of my suits!

Donald R. Lennon:

If you're ever in a battle, get out of your room!

John L. Landreth:

Yes, get up to your battle station, you're safer up there. We continued working and we raised the ship. It was the first one that was raised. The remarkable thing was there was

only one person, apparently according to Prange's book, who thought the engines would work. He was a chief engineer on the . As soon as they began pumping the water out of the ship, he had guys go down in there and as soon as anything was exposed, he squirted oil over all the machinery. When they got the thing raised, he turned on the engines and they went! We came back on our own power.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow!

John L. Landreth:

We came back to Bremerton. We were all taken off the ship while the was being rebuilt from the second deck up. The bridge area had been burned out. Everything was removed and we lived in the BOQs. We did whatever we were supposed to do. It turned out that the was being built down in Norfolk and was pretty close to commissioning. The commanding officer of the was in the Bureau of Naval Personnel and the man who was exec was his assistant in the Bureau of Naval Personnel. They could really pick anybody they wanted--any officers they wanted--to go on that ship. What they did was to pick people from the battleships--officers that had been in action. In May, I got orders to go to the . I went aboard the and put her in commission, did the shakedown cruises, and all that kind of stuff.

Sort of a funny thing happened in all of that. On the we ended up living in what had been enlisted family living quarters in Pearl Harbor. Lynn Barry came back from his radar training and was living in this thing with me. They were starting a school. He was going to go to another course on radar. Of course, the word “radar” wasn't even known at that time. I don't know why, but he said to me, “Why don't you come on to this radar school?”

I said, “Well, that would be great except that there's no way I could get into it. I don't have all the training you have.”

He said, “Well, they have a test you have to take to get into it, but it all comes out of the amateur radio handbook. I'll go through and underline all the material you have to know and just learn that and take the test.”

I took the test and passed, which was ridiculous, because it was like getting an eight hundred on the SAT when you should have gotten a five hundred, you know, if you hadn't done one before.

Anyway, I got into this class and there were all these chief petty officers and all these people who had been to these long schools. They knew all this stuff and I didn't know beans about it. Most of the time they would lose me after about five minutes of a lecture. I was just struggling and they all knew that I was just terrible, but they didn't throw me out of it.

Harry Seymour had gone from the to the two or three weeks before the rest of us went. There were just five or six officers aboard, they had this radar equipment, and somebody said, “Anybody here know anything about radar?”

And so Harry Seymour says, “Well, Sandy Landreth does. He's been to this school.”

So I arrived and became the radar officer. That didn't last very long, thank goodness. Pretty soon they sent a couple of young guys who had been in engineering who didn't know anything about the Navy, all they knew was radar.

But then they made me gunnery radar officer. I retained that title and then they sent me to some more schools. Actually, it turned out to be a good thing because they had a target practice and nobody could understand why it went wrong, but I figured it out. It had

to do with the way the radar worked and bearing. I figured it out and and nobody else could figure it out. So I guess I earned my title.

Then, on the , we went into the North Atlantic and became part of an Allied task force headed up by a British admiral. There were British ships and American ships. Our function was to seek out and destroy all the German capital ships that were hiding in the fjords, but nothing we did could ever get them out. We would go between Scapa Flow and Reykjavik. Those were our two bases.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the submarine danger very bad at this point? This is in the summer of '42 now we're talking about.

John L. Landreth:

Well, we're talking beyond that because the summer of '42 we were just going into commission. By the time we got out there, with shakedown and everything, it was probably February of '43.

We didn't have any trouble from submarines because submarines were out to get shipping. They would stay as far away from us as they could, I would think. We didn't have any trouble; we didn't encounter any submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you convoying, troops?

John L. Landreth:

No, not anything. We were a fighting unit out there.

Donald R. Lennon:

When I think of the North Atlantic, I think of convoy duty.

John L. Landreth:

Yes, but this was a different thing. We weren't going across the Atlantic. We were just out there. The Germans were in Norway and we were just trying to get them and sink them all. So we didn't do any convoying. We didn't run into any submarines but submarines wouldn't have fooled with us because they would have a pretty good chance of being sunk.

What a contrast! I was put in an anti-aircraft director but our director in the was a hundred light years from these new ones. They had a slowing switch up on this thing and you would put one hand on this slowing switch and you just go in any direction you wanted to and the director would swing around and all the guns would swing around. The equipment was really fantastic. It was such a contrast to the old ships. Of course, they rebuilt the fter they rebuilt all the old battleships, they would look just like the new ones and they would put the same kind of equipment on them.

There was one German reconnaissance plane that followed us. One would relieve another and they always followed us wherever we went so they knew where we were.

Donald R. Lennon:

But always out of gun range.

John L. Landreth:

Just out of gun range. After a long, long time, this British admiral got sick of that. He put in for a small British carrier. They brought the carrier out there, and they sent a fighter out after this guy and they hooked up the P.A. systems . . . at least on the , and I imagine on all of them . . . and you could hear the pilot talking back and he shot him down “right behind the bugger!” We could hear little machine gun bullets go up and then go down. We got rid of that guy. Very little happened.

The crazy part was in Reykjavik, Iceland, we were anchored way up the stream. We stood four-hour gun watches continuously but we were not allowed to shoot at any German plane. German planes would fly over all the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why couldn't you shoot them?

John L. Landreth:

Well, that sounds a little funny at first but it makes a lot of sense. The same thing was going to happen to us in England when we went over there. If they let us shoot, we'd

shoot down more of our own planes than we would German planes, so they wanted to shoot down these planes with airplanes. They'd go up with fighters and shoot them down.

Donald R. Lennon:

They could see what they were shooting.

John L. Landreth:

Yeah, they knew what they were doing. They had plane identification courses and we had two experts to come aboard. I was terrible at this airplane identification. But when those guys got in battle conditions, they couldn't tell one plane from another. Even the best of them couldn't tell. So my rule was, if anybody got close enough to me, I shot at him. They couldn't be friendly if they got close to me. That's a pretty good rule. Of course, although we didn't, some people shot down some of our own planes. But, those planes shouldn't have gotten that close unless they're sure of what they were doing because you couldn't tell one plane from another in combat.

On the , we also had target practice. This target practice was a combination of speed and accuracy. They towed the target down this way and we had a director face this way and when they gave us the word, we could just move the director around and start shooting.

Well, I did an illegal thing on the ; I had the phones changed. Normally, we could either listen or talk--we couldn't do both. I had mine fixed so I could talk and listen at the same time. So when it came my time and they gave the word to commence firing, I didn't have any delay. I could get my guns and commence firing. We slued around and got on this target and I decided to go for speed, not for accuracy. Our first salvo--we were out there really fast--went over, and the next salvo went under and the next one hit it and I didn't change a single setting! I was just going for speed! I just let my three salvos go, and for some reason they just straddled, which is perfect gunnery, you see. And I hadn't

done anything. But I got the prize because they thought I had made all these wise decisions about changing the settings on my director.

Donald R. Lennon:

That quickly.

John L. Landreth:

Yeah. And I was just going for speed. I had the speed and then I got the accuracy by luck and so I got the prize.

Anyway, we took part in a dummy invasion of Norway to draw troops up away from some place while they attacked someplace else. We were part of that, but we didn't do anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

The weather was pretty rough up there, wasn't it?

John L. Landreth:

Oh yeah. I was lucky. Once again, radar helped me. I ended up in a little tiny room, a little tiny space. While we were fitting out, I went over to the Navy yard and I got them to make a wheel that turned so that I could orient data on the screen through my heading and could tell where the planes were. I was in there with this radar man third class and we'd get this data and put it in there. And these other poor devils were out on this open bridge, the wind is a hundred knots and it's blowing hail in their faces. They're just miserable and we're sitting in this nice warm place maneuvering this little wheel. Oh, it was terribly cold up there and rough. Of course, it was the same way with the officers of the deck, they had to get out in that. But if I wasn't in this radar place, I was in the director, which was protected. So I got away with it in that regard, too.

The Navy's process was all changed during the war. Normally, after getting out of the Academy, I would have spent two years in a battleship, spent time in every department, to become a qualified officer of the deck. But in the war, I was never a qualified officer of the deck in port, I was never a qualified officer of the deck at sea, all I did was stand gun

watches. And then I got on the , and I'm the exec and the navigator. I'm beyond all that; I'm supervising the deck officers! I never got qualified in that. And then later on I became a first lieutenant and I didn't know what they did. I had never worked in that position.

Finally, that thing was over and we came back to Norfolk. Because of Sheldon Kinney I went into DEs. Sheldon Kinney was a sensation in the destroyer escort program. He was a regular officer, he had come from destroyers and was just sensational in DEs. They decided that they should have some input of regular naval officers into the DE program. That was about the time we got back to Norfolk and I got my orders to go to SCTC in Miami for school for three weeks and be assigned into the destroyer escort program.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the time frame of this, summer or fall of '43?

John L. Landreth:

This is the summer of '43, I guess.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you had been on battleships for two years. That was really the only type of vessel you had any experience on, and subchasers were not much bigger than a lifeboat to a battleship.

John L. Landreth:

Well this was DEs. DEs were a pretty good-sized vessel, they were two hundred feet long. They were almost as big as a destroyer. They had two hundred men on them.

Donald R. Lennon:

But I mean they were quite a contrast with a battleship.

John L. Landreth:

Yes. There was quite a contrast between them. I finally became a division officer right toward the end of my tour on the . From a division officer, here I am an executive officer and navigator. So yeah, you're right. It was some kind of contrast, a tremendous contrast.

When we were ready to graduate from the training program in Miami, we got to tell them where we wanted to go. Well, I came from California, so I wanted to go to the West Coast. The skipper came from Los Angeles and he wanted to go to the West Coast. So they assigned him as skipper and I was the exec. But our ship was building in Orange, Texas. They had this grade system. DEs, as you know, were the most organized thing that ever happened to anybody because they had so many and they had to organize them. So what they did, the captain and some key petty officers went to Orange, where the ship was building; and as exec, I took part of the officers and a few key enlisted people and went to the Norfolk training station, to the boot camp. They assigned a crew then. One of the interesting aspects was that they had to allocate . . . they had to open the brig up and allocate every crew its percentage. We got 10 percent of our people out of jail--out of the brig and into the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh really?

John L. Landreth:

That's the proportion that we had. We had one in every ten guys at the base who had gotten in trouble and was in the brig.

This turned out to be one of the most interesting experiences of my whole Naval career. I was in charge of this whole group and they were all in the barracks together. The way the program worked was that these guys were marched off at eight in the morning and were taken to be trained in whatever they were being trained at. The base was doing all that, so I had no demands on my time. But what I soon discovered was that this 10 percent that we got had not been totally reformed in the brig.

So I started holding executive officers mast for all these guys. Illegal, I suppose, but anyway, it was an informal kind of thing. So I got these guys and I knew they'd probably all

get in trouble, but what I found, as a result of that experience, is that any personnel problem can be solved. You can solve these problems, although you may have to spend a lot of time on them and you may have to use different techniques--everyone is a tailor-made thing--but you can solve them. There's no way to do this at sea; however, you don't have the time.

So I devised this thing for the Navy. I think the Navy should permit the commanding officer to send back 1 percent of his crew every quarter or something like that, to a retraining station. These guys would all be sent back there and everybody would be spending full time on these guys and when they got them retrained, then they could go back.

But I had a guy--this is why it was so fascinating--that was a professional bum. He was only a kid, sixteen, I don't know, but he and his brother had been bums all their lives, as near as I could tell. The thing he liked most was to be dirty. The thing he wouldn't do--the worst thing to happen to him--was to take a bath. That was absolutely the worst thing. Of course, everybody began complaining about this guy. So I get him and I keep him . . . talked to this guy and doing all this stuff to him and everything, but I didn't make any progress as far as I could tell.

I finally get in this session, and this is going to be the last session that I have with Samas. He was always complaining--he had all kinds of complaints. One of the things I said, and this may have been what did it, I said, “Sam, your problem is that you just think about yourself all the time. You never think about anybody else. If you'd stop that, and only think about the other people, then you wouldn't have to worry about yourself. It would all be taken care of for you. You wouldn't have to worry.”

I'd talked to him eight times . . . I'm not going to do that again . . . but, anyway, something just changed this guy completely around so that later on when I got on the ship,

Samas was the only guy that took a shower everyday! Everyday, he took a shower! He looked great. In about three or four months, after we'd been commissioned, Samas came up to me and said, “Mr. Landreth, those guys back there have stopped doing their cleaning just because it's knock-off time, but their place isn't clean yet.” Wow!

I had a string of those and every one was different.

Donald R. Lennon:

You have to be a psychologist as well as everything else.

John L. Landreth:

Well, you have to be a psychologist anyway. You know I've often thought about that and, actually, some other people have had different experiences. Like with Vietnam, they've come back and told me about their experiences with training the natives and stuff like that.

There was one guy who would go to sickbay everyday. Every morning he wouldn't go out with the training. I had these three yeomen and I took one of these yeomen and said, “Okay, you go to sickbay with this guy, and you follow him, and come back and tell me what happens over there.”

So he came back and told me, he said, “This guy lets everybody in front of him in the line. He went to sickbay at 8:00 and didn't get out until 2:30 in the afternoon. He lets everybody go in front of him.”

I said, “Okay, you go with him tomorrow and you make him stand in line.” And I said, “When he gets up to the doctor, you say to the doctor, 'This man's executive officer thinks this man is a “gold brick” and he wants a personal report on what's wrong with this man. He comes to sickbay everyday.'”

So they agreed that he was a “gold brick” and this doctor said, “What the hell, there's no use coming to me. You ought to go to the chaplain.” He was a strong Catholic.

“You ought to go to a chaplain and get a hardship discharge.” He was an older guy and had a family or something.

So soon as I found that out, I called the Catholic priest and I said, “A man in my battalion is coming over to you, and I think he's a 'gold brick.' I don't want him to get a hardship discharge unless he really deserves it.”

Well, I don't know what that priest said to him, but that's the last time he ever tried any of that stuff. That priest, I guess, really read the riot act to him or something. That was something he could really respect.

Donald R. Lennon:

He straightened up.

John L. Landreth:

He straightened him up.

Well, anyway, if you read this thing, you're going to read a lot about the . When we went into commission, we had almost nobody that had been at sea before. An interesting thing about the was that the captain and I were both Naval Academy graduates. The captain was not regular Navy. He was in the Class of 1934. The Class of 1934 was in the depths of the Depression. They only commissioned half of the class. You could say whether you wanted to be commissioned or not. He chose not to be commissioned but he stayed in the Reserves and so, in 1940, he was ordered to active duty. He was a Naval Academy graduate.

Another funny thing about that was that he'd come out of the Fleet and gone to the Naval Academy and he'd been an electrician when he was in the Fleet. Our chief petty officer electrician, the senior electrician aboard, and he, the captain, had been electricians together.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no, and they wound back up in the same ship?

John L. Landreth:

They wound up back in the same ship and the chief took a dim view of that.

The captain and I and a few chief petty officers were the only officers that had ever been to sea before. We went out into a storm in the Gulf and everybody got seasick except the captain and me and two or three other people. Everybody was seasick. Of course, a destroyer escort was the roughest ship ever built. They were supposed to be able to go over 55 degrees and come back and come back fast, and I've been on it when it went over 55 degrees. We were near the water right then. The chief petty officers had their quarters in the fo'c's'le, and that thing banged down so much in rough weather that they couldn't stay there. It was bouncing them right out of their bunks.

But anyway, all these people were seasick, all except one who didn't get seasick. One finally, after about a year, had to be sent to the hospital because he was still getting seasick.

We joined our sister ship, DE-791, the which was commissioned at the same time and we were together all the time. We were supposed to belong to Halsey's Fleet, but we did all of our shakedown and everything on the East Coast--Bermuda and all that stuff. By the way, at Bermuda, as the final part of the DEs shakedown cruise we had to find this submarine. The submarine got through all of us. Sheldon Kinney was in the worst position. He was way at the back and he got it. That was his second ship, I think. Then he got another one. He was, you know, fantastic!

So then, we went up to Boston for post-shakedown repairs, you know, to correct whatever problems the ship had developed. And then we came down to New York in the inland waterway. By this time, we had a commander who was the commodore of six of these DEs. There were only two of them together, but he had these two and then he had

four others someplace, and he was on the ship. The captain had to give up his bunk because we weren't equipped to have commodores.