| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

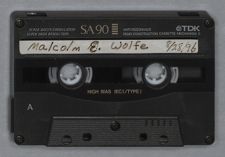

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #156 | |

| Captain Malcolm E. Wolfe | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| August 28, 1996 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Just begin with your background in Texas, where you came from, where you got your early education, and what led you to the Naval Academy.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, I was raised on a small farm down in the southwest part of Texas, in a little town called Aransas Pass. I went to a high school that had about three hundred fifty students, and we had thirty in our graduation class. I was the youngest member of the class to graduate; I was only sixteen years old. I wasn't very enamored with farm life, because I was raised right during the Depression. I was the salutatorian of my class, and I had a scholarship to Baylor University; however, I just didn't have the funds to continue it.

So immediately after graduation, I applied to enlist in the Navy. My objective at the time when I applied to join the Navy was to save up enough money, get out, and go back to college. As it turned out I was too young, and they told me to come back when I was seventeen. Three months later, I went back. I was inducted into the Navy and went to San Diego Naval Training Base. There was a quick three-month indoctrination, and I was assigned aboard a World War I destroyer. At that time, I didn't even know what the

Naval Academy was. But I continued the boning-up on my mathematics, because I still wanted to go to school right after I got out. I spent almost three years in the service. We were on a cruise out to Hawaii, and my first class signalman saw me studying. He said, “Would you be interested in trying for the Naval Academy?”

I said, “Well, what's that?”

He said, “Well, they can send a certain number out of the Fleet to the Naval Academy Preparatory School, but you have to be recommended.”

This was in June, and I think there were about five days before my eligibility expired. I was on the flag at the time. My immediate superior talked to the Commodore, and said, “I've got a young man down here who's interested in the Naval Academy. We'll have to get a dispatch in first to be able to get him on the eligibility list.”

He says, “Well, by all means.”

Next thing, I'm up there interviewing with the Commodore on the bridge. I can't even remember the questions he asked me, because it never even occurred to me that I had a chance. So they got off the dispatch. They came back and said I was approved to take the qualification exam to the Naval Academy for the prep school out in Norfolk, Virginia. Well, I had a lot of push from others. My division officer took an interest in me. I think I was the only one out of the destroyers who ever had applied to the Naval Academy. So he gave me some tutoring, but I did most of my studying on my own. To make a long story short, I took the exam. After a couple of weeks, I got the word back that I had been accepted. So, I packed my bag and headed off to Norfolk.

It was a six-month, very rigorous indoctrination. I had no problem on the entrance exam except for one subject--English. It ended up my best subject in the Naval Academy,

but initially I got by with the skin of my teeth. I was dedicated to staying in the service from the “get-go” when I went to the Naval Academy. It had never even occurred to me that I'd ever get the opportunity to go there and become a naval officer. I found my first year very difficult.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lot of them had been through that prep school for training for the Naval Academy, too.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

The Navy permitted one hundred a year to come out of the Fleet, but they had never been able to fill that quota. I think there were only about eighty the year that I came to the Academy. I had a rough time the first year and stood pretty low in the class. The second year became easier, and I gradually improved my standing. Then, the third and fourth years came pretty easy to me; but I had to take a re-exam in marine engineering my third class year. I passed it, but it wasn't by a great margin. To me, the Naval Academy was a first step. I sort of tolerated the hazing that went on during the fourth class year. I had my goals pretty well firmed-up before I got there. I felt that in a lot of cases, my two and a half years in the Fleet gave me a pretty firm foundation on which to build. When we graduated early in February 1941, I left there with not a great deal of regret that I was leaving; but, I had obtained a commission and I was eager to get on with my career.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think most of the class members were not that impressed with the actual instruction that you received while there.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, we were all under the same curriculum. Now they have a very broad curriculum, and I'm still not quite sure whether I agree with this spread out curriculum where everybody can go into any type of field that he wants.

Donald R. Lennon:

But didn't you pretty much have to teach yourself?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Oh, absolutely. The standard expression was, “Go to the book.” If you had a question, you would go to the book. It was understandable, because they had a great number of naval officers coming back teaching who had been out of teaching for a long time. I can remember that one of my math instructors was the father of the senator from Arizona, the one that spent several years as a P.O.W.

Donald R. Lennon:

McCain?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

McCain. He was my math instructor then. I tell you, he was a card. He hated to be there, and he didn't make any bones about it. About every other word was a swear word. He said he didn't want to be there, but we learned. I mean, we got through, but I'm sure we didn't get the very best of instruction.

I had made up my mind when I left the Academy that I wanted to go into aviation. That was my primary thrust. So I requested destroyers. Then I was assigned back aboard another destroyer, which was about two numbers from the one that I came from. I was on the old USS BORIE, 209, and I was assigned back to the CHANDLER, DMS-11. We had about six or seven officers on board, and we were short about two; so we had to learn quickly. We were in the same division as the person who became “ Mutiny” author.

Donald R. Lennon:

Herman Wouk?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

I think Herman Wouk was the executive officer on the USS HOVEY at the time. All of the experiences he wrote about happened to all the commanding officers in that division. He just rolled them into one. It was a high speed, fleet minesweeping division. We were told when we got aboard, that we were expected to take over as officer of the deck in a very minimal time.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your primary assignment?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, when I got there, we had not gone to sea yet, and the commanding officer said, “Well, I haven't really quite decided. Yet, I think I'll make you an assistant engineering officer, because our chief engineer is probably going to go to another ship. So, you may have to take over.” Well on our first deployment, we went out for a two-week exercise. The second night we were out, I was roused out of my bunk.

The messenger said, “The commanding officer wants to see you on the bridge.”

I went up to the bridge and the commanding officer said, “Our chief engineer just got transferred; he had appendicitis, and he's not going to come back. You are now the chief engineer.”

Donald R. Lennon:

And you considered yourself weak in engineering didn't you?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

I did. I considered myself very weak in engineering. Well, the saving grace was that we had the senior chiefs who had never transferred around. Some of them had spent their whole careers on the same ships. I had four of them and when they heard the chief engineer had been transferred, they all came up and set themselves down outside of my stateroom. They said, “Look, don't worry. We'll take care of everything down below if you take care of everything above.”

And they did; they really honestly did. They knew the ship from one end to the other. So, I got through the ordeal of being chief engineer. I guess I was chief engineer for about eight months, but then the commanding officer was relieved by a Captain Dorsey, who was a communications specialist. He said, “I don't want you as chief engineer. I want to make you my communications officer.” So, I was taken out of engineering. In the meantime, I had qualified as officer of the deck and was standing sea watches, because we had to.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, what was the CHANDLER involved in at this time?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Its mission was high-speed fleet minesweeping.

Donald R. Lennon:

But where were you?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

We were stationed at Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

Okay, so you had already gone to the Pacific?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes, we were in the Pacific, and I picked up the ship at Pearl Harbor. We would go out and conduct weekly exercises, and then we would come back into port and spend the weekends in port. Of course, the Japanese knew that very well. Fortunately for us, before Pearl Harbor we were out on a weekly exercise. I was the communications officer, and I was decoding all these messages that were coming through. I knew that we were going to go to war. There was no doubt in my mind; it was just a matter of when.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were picking up Japanese messages all the time?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Right, we were decoding messages sent by the State Department to Japan.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you having any trouble deciphering them?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No. There was a Fleet channel that my CO wasn't supposed to monitor, but he did anyway. We had the code to it, and he would have me decode all these messages that were going back and forth between the Fleet commanders. So, we had a lot of information that we weren't supposed to have. Anyway, the morning of Pearl Harbor, we were between Maui and the main island, and they told us to report to . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you at anchor there?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No, we were patrolling. We had a lot of possible submarine contacts, made a lot of submarine runs, and dropped a lot of depth charges; but we never had any indication that we ever hit anything. The feeling was that we were chasing fish, but I think that we

were probably chasing a lot of those miniature Japanese submarines that they had in there. However, we went racing back to Pearl Harbor, and the first attack was already over when we got there. The Japanese had started broadcasting on the harbor patrol channel, which they had confused with plain language messages. They told us to go up north where the Japanese were making an amphibious landing on the northern part of Oahu. We raced around there at maximum speed, and when we got there, there was nothing there. So, finally the commander of Hawaiian Sea Frontier shifted over channels and got control back. We didn't go into the harbor that day.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would have been the most dangerous thing you could have done, wouldn't it? They were trying to get ships out of the harbor not bring more in.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Our big problem was we'd been at sea for about five or six days, and we didn't have enough fuel. We were getting awfully low on fuel and we needed to go in and refuel. I think it was the next morning or the day after that we got permission to go into Pearl Harbor, because their refueling capacity had not been interrupted. The Japanese never bombed the fueling facilities.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

So, we went in and refueled. It was an awful sight when we went down the harbor there to see all those battleships on their sides.

Donald R. Lennon:

Some of them were still burning, I'm sure.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Oh yes, there was still smoke coming out of some of them. I guess that was when I really solidified my desire to get into aviation. I wanted to make an impact, and I just couldn't see it on that high speed mine sweeper. I had my request in for naval aviation, and it had been turned down by the previous commanding officer; but the one that came

aboard and made me his communications officer, he readily approved it. He was an ex-aviator who had given up his wings and had gone back into ships.

In the meantime, in December, we were told to go to Alaska. It took us four or five days to get to Seattle, and then we went out and joined Task Force Eight, which was patrolling the waters off Adak and Attu. Yet before we went to Alaska, we were told to escort a ship out to Midway. It was a final supply ship that went into Midway before the Japanese attacked. From there we went to Dutch Harbor, and we sort of gave up the Fleet minesweeping operations. We had no radar; we had nothing. We were following these big ships around in the fog, and we had absolutely no idea where we were. We'd pick up these tankers out of Adak, and they'd wallow around in these high seas trying to stay within the war zone until they could qualify for war zone pay. Then, we had to let them go on outside the war zone.

Right before the Battle of Midway, there were a lot of Fleet dispatches saying that the Japanese were going to attack the Aleutian Islands. They gave us the composition of the Fleet that had left Japan. So, everything was launched, including all the patrol planes. These patrol planes operating in Alaska were under the most horrendous conditions you could imagine. The Air Force had also stationed planes on the island of Adak. They had an airfield equipped with steel matting they had installed. They launched everything in the area to look for the Japanese fleet. Well, pretty soon, one of the patrol plane commanders radioed back. I was still in communications, so I was deciphering all the messages. The patrol plane commander reported sighting the Japanese fleet, giving details of the fleet exactly like those previously reported. So, we all raced out there with our three-inch guns; we were going to intercept the Japanese fleet. We looked and we

looked, and there wasn't a sign of them. The only thing that anybody could figure out was that the patrol plane commander was convinced he saw what he had been briefed on . . . you know if you go up there flying through that soup for hours on end, you can talk yourself into seeing almost anything. However, there was nothing there.

They did get some good out of it though, because they were loaded up with torpedoes and had to fire them before they came back. Well, when they fired them, they all broached, and none of them worked. What had happened was that one of the army personnel on the island had gotten in and was drinking the alcohol out of the torpedo gyro guidance mechanism. The gyros were filled with pure alcohol. They drained the whole works. They found out who was doing it. In fact on my last trip ashore, I saw the one that was responsible. They had him in an outside stockade where they were holding him for court martial.

Donald R. Lennon:

They had enough troubles with those torpedoes as it was without their being sabotaged by some drunk.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Nothing really was very exciting until Task Force 8 was assigned to bombard Attu Island, occupied by the Japanese. Submarines were reported in the vicinity of Attu. We started in when the Japanese Fleet commander had decided to make a quick exit for some reason. In the matter of about thirty seconds we had a four-destroyer collision, including the one that I was on. We rammed each other in a matter of about thirty seconds. Our bow was bent back at a forty-five-degree angle, and the other two destroyers were in about the same fix. We could still make about ten knots.

We were ordered to go back to Seattle and get a new bow put on, so we turned around and went back to Seattle. It took them about two weeks to put a new bow on us, and then we were back in the Aleutians again.

In a couple of weeks, this was in February I think, we got this message to go out and see if we could be of any assistance to a destroyer that had run aground over on one of those uncharted islands. We were to go see if they needed any help. We found she was capsized right off of the island. The survivors had all gotten off of the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, what ship was this? Do you recall?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

The one that capsized? No I do not recall. It wasn't one of the older ones from World War I, but it wasn't a newer type destroyer either. I don't recall which one it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now one destroyer caught a mine up there during that period.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, this one didn't appear to have any hull damage, because when we got there the hull was completely out of the water. It was lying on its side washed up on the beach. I think they ran aground on some rocks out there that were not charted.

Donald R. Lennon:

Go ahead, I'm sorry. I was trying to remember the ship that was sunk up there in the Aleutians.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Afterwards, I received my orders to go to flight training, but I couldn't find any transportation out. But one of the other ships, the USS LONG, had some problems, and they had to go back to Kodiak. The skipper told me if I could pack my bag in ten minutes and get ready, he'd transfer me and send me back to flight training. I told him that I could be ready in five. So I went down, threw all my gear together, got in the longboat, and was on my way back to Kodiak in about fifteen minutes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this still in '42?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

This was in '42, 1942.

I went in through Dutch Harbor and was hoping to get air transportation out of there immediately; but it was raining, and it rained for five days. I finally got on an old transport plane, an R5D, taking a bunch of engines back to San Diego for overhaul. The pilot said, “Well, I've got one vacancy up here. I had to take off one engine, so that leaves room just for you up there if you want to take it.”

I said, “I'm ready.” I had a set of orders that were written so that they read to proceed in accordance with secret orders, and that was the magic word.

Donald R. Lennon:

However you could get there.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, I got on this airplane and rode it all the way back to San Diego. From there, I hitched a ride on a SNB that was going down to Corpus Christi. My orders were to go into primary training in Dallas. I was a little bit unnerved when I got on board this SNB. I didn't know the pilot's qualifications--I think he was in his fifties--but he couldn't see very well, because when he asked me to hand him a chart, he had to break out his spy glass to look for something on the chart. You know, they were bringing in anybody that could fly an airplane in those times. We got back, and he dropped me off. I spent about a week, almost ten days with my family there, which was very close to Corpus. Then, I went on up to Dallas and checked in there.

My flight training went really well. I completed the primary in Dallas without any real incidents. I then went from there, down to Pensacola and took advanced training. I received my wings in September of 1943. I put in for dive bombers and went from Pensacola down to a field near Deland, Florida. We took six months of operational training in SBDs. Because we were lieutenants at the time, they knew that we were going

to have to take over as executive officers of squadrons when we left there, so they gave us an extra six months of instruction duty, in which we took over flights of about twelve aviation cadets and took them through the operational syllabus. I think I took about three groups through in the six months. We had no casualties, and there were no problems.

Subsequently, I was given orders to go to Glenview, Illinois, to qualify aboard the old WOLVERINE, which they converted into an aircraft carrier. That was sort of a joke. We went up there in mid-winter and did our practice. They took a snowplow, plowed the snow off of a hill, sent us out, and let us make a few practice landings. Then, they launched us out to the old WOLVERINE out in the middle of Lake Michigan. The only thing we had was an RDF and our plane to find it. Until this day, I don't know how they qualified as many pilots as they did.

Donald R. Lennon:

I understand that they lost a lot of them over in the lake. They are still fishing planes out of Lake Michigan.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, it was sort of dumb. I don't know why they did that. But anyway I didn't feel like I learned an awful lot, but I did get my qualifications in. From there I was ordered to activate squadron VB-10, of Air Group Ten, which was at Wildwood, New Jersey.

I went to New Jersey. The commanding officer had been assigned, but he had not reported. He was “Bucky” Bucan who had an awful lot of carrier duty and had been in the Pacific. I ended up as the executive officer, and we spent about three months training on the East Coast.

The most harrowing experience that we had was when they told us to go out and carrier qualify on the old PRINCE WILLIAM which was one of those converted Kaiser

carriers. We also got a new complement of the SB2C aircraft, which were replacing the SBDs. We took twelve planes out to qualify. I never will forget that “Bucky” Bucan had about four hundred fifty carrier landings to his credit, and I think I had probably twenty at that time. During the “car quals” he was supposed to be the first one to take off, then I was going to be the second one, then the engineering officer the third, and so forth. Well, the LSOs had never worked SB2Cs and had no idea what their flight attitude was on a carrier approach. I was watching who I thought was my commanding officer make the first landing, and when he came around on his approach, they cut him. He didn't even touch the deck--he just went over and flopped in the water. I was thinking to myself, 'That's not very good if he has five hundred landings and I've got only twenty.'

Well, it was time for the second one to come in, and I was it. They had us circle while they picked up the pilot. I still didn't know that it wasn't the commanding officer who had gone into the water. It turned out to be the engineering officer. I then came around, and they were giving me “come-ons” all the way. I never did quite trust LSOs, so I was watching my speed indicator with one eye and watching the LSO with the other; he was giving me “come-ons” at ninety miles an hour. I knew we were supposed to slow those things down to about eighty, but he was still giving me the “come-ons.” When he gave me the cut, I knew that I was too fast. I tried to get down, but I couldn't. Finally, when I thought I was going to duplicate the first one, I caught the last barrier with my tail hook and ended up with my nose sticking over the nose of the flight deck. It was that close!

Those planes were much too heavy for that small carrier, but we did day and night qualifications on it. We never lost any pilots. We ditched about four aircraft, but we

busted up twelve airplanes. I mean, we had to send back and get twelve more to finish our qualifications. We finally got qualified both day and night and went back in the air group. From there, we were told to join the USS INTREPID, which was in San Francisco, waiting deployment. At the time we didn't know whether we were going to be the air group to go on the INTREPID, or whether we were going to be put off in Pearl Harbor and wait for another ship. However, we did training going out.

After we got to Pearl Harbor, the commanding officer liked what he saw and said, “I want to keep this air group.” So, we got to go out about a month before we expected to. We went by Wake Island, and we did mock attacks on it as a warm up of things to come.

We then joined the Third Fleet in Ulithi. This was in early March. We knew that Okinawa was going to be the next big push. The ship was given orders to join our group. We had sixteen carriers in four groups of four carriers each. Our main mission was to completely knock out all the Japanese air north of Okinawa, including Japan. It was on March 19, 1945, that we started our attacks on the mainland of Japan. The commanding officer led the first attack on Aida Air Base. He was shot down on his first mission. Fortunately, he was recovered by a submarine and taken back to Pearl Harbor. I had the squadron the rest of the time we were deployed.

Our second attack, which I led, was against Kure Harbor, and that was against the remnants of the Japanese fleet. They had a couple of carriers, a battleship, and some more fleet units in there, and our main objective was the ships in the harbor. I have never seen such fireworks. There was no air opposition, but their anti-aircraft fire was intense.

Donald R. Lennon:

They didn't have that many planes left, did they?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No, they didn't. But their anti-aircraft fire was absolutely incredible. They did all their altitude versions by different color bursts. They had red, purple, green--you name it--over Kure Harbor when we made our approach at twelve thousand feet. It was just like a colored canopy over that whole harbor. When we started into our dive, I started on one of the carriers they had there. All of the groups later said that just before I started, the whole area where I had been was just blanketed with this colored AA fire and they thought that I had had it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were talking about the hits on the . . . .

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, the AA fire was really intense. I was concentrating solely on my target, which was one of their CL carriers, not one of their big fleet carriers, but a CL carrier. I had no time to even survey the horizon.

Donald R. Lennon:

There wasn't much you could do about it anyway.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

My wingman was shot down, and we did not know what happened to him until after the war when we found out he had been picked up. He ditched in Kure Harbor, and he had a very interesting little anecdote about it. He said that after he ditched in the harbor, he and his air crewman got out of the plane and into their lifeboat, and this Japanese boat rode out there to pick them up. He said they did not say a word, but they just started beating him over the head with their oar. But, they took him back. I guess he was treated well, because they knew the war was getting down to the end. That was the only one that we lost at the time, and we got back to the carrier without further incident. The next morning we were on deck and preparing for another strike when the carrier FRANKLIN was hit by a kamikaze. We were getting ready to take off from another strike, when the FRANKLIN got hit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, she got a kamikaze hit?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes, she got a kamikaze. We had about forty planes on the deck getting ready to take off when we got the kamikaze alert. We were on deck for about fifteen minutes warming up, before they told us to cut the engines and go below. About that time they blew up a Betty about fifty yards off of our bow. They had come for a kamikaze attack. Then I think it was the next day, when we did get a kamikaze. We took a kamikaze down in the number one elevator. I guess we had gone back to Okinawa and were conducting support operations off of Okinawa. We spent about a week or ten days there, and they were sending out these kamikazes regularly. We were just lying off the coast of Okinawa. We had made about twenty strikes. I think I was on fifteen of them. I was normally rotating every other strike with the executive officer. I believe it was about fifteen strikes when we got kamakazed by a small Japanese plane. He ended up down in the number one elevator. He started a fire on the hangar deck, and it spread up to the flight deck. We had to kick over about twelve or fourteen of our aircraft and just dump them over the side. That pretty much ended our operations. They told us we could have continued under very marginal conditions, but I think they felt that the war might go on for some time. They told us to head back to the States and get repairs.

Donald R. Lennon:

How much damage did it actually do going down into the elevator?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, it knocked out all the forward part of the flight deck. It put the forward elevator completely out of commission.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have much loss of men?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No, I don't think we had any people lost. There were a couple of minor injuries but nobody lost a life.

Donald R. Lennon:

One thing you said when you were off Kure Harbor was that you were getting ready to fly off the planes, and they had you go below instead. It would seem to me that if they were anticipating a kamikaze attack it was better to have the planes in the air than on deck.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

I think there were probably two schools of thought on that. It was at the beginning of the launch operations, and I think the commanding officer didn't want to put himself into one position while he was launching those planes. He wanted to be free to do his maneuvering, to avoid the kamikazes since they were coming in. I could see his point, because once you start launching your aircraft, you are in irons on one course until you get them all off.

Donald R. Lennon:

But other than that, it would have been logical to scramble planes to try to take out the kamikaze from the air wouldn't it?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Right, but we were normally launching very early in the morning. The weather wasn't that great. The kamikazes were coming in under the overcast--very inexperienced pilots. They didn't have the slightest clue as to anything except trying to find a ship and diving into it.

Donald R. Lennon:

From what I understood, they had very little training.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No, they didn't have any training. On one of the intercept missions, when we were off of Okinawa, one of the combat air patrols went up and shot down seven of these kamikazes. On the last one, he used up all of his ammunition; so he just pulled up alongside of him, pulled out his forty-five and was shooting at him with the forty-five. They did no maneuvering; they did nothing. They just went to find a ship. Their mission was to hit a carrier, and when they found one of those radar picket destroyers, they dove

into the destroyers. We were refueling on one of our rest intervals, and the destroyers were coming alongside for the carriers to refuel them. Up on the bridge of the destroyer, there was a big sign that had a big arrow. It said: “Carriers That Way.” Everybody got a big laugh out of that.

Afterwards, we went back to San Francisco and got our flight deck repaired. We were on our way back and had just arrived at Ulithi, when we got the word that the war had been terminated. That really terminated war operations. We spent about two months covering the Marine landings in Korea and Northern China. The Marines had made landings all up and down the coast there. Then after we covered those landings, we got orders for the squadron to go back to Saipan where we had a base. We were to leave the carrier. Once we landed, we had orders to go back to the States. So we picked up a small jeep carrier, and the whole squadron personnel was loaded aboard it. We went back to San Francisco.

Donald R. Lennon:

You just left the planes up there?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes, we just left the planes and everything there. There was a new air group that came out to relieve us. So, we went back to San Francisco. On the way back, I got orders to sign on as a navigator on the USS ANZIO, which was a jeep carrier.

Donald R. Lennon:

One question before we leave World War II. You were talking about your squadron attacking the Japanese ships there in Kure Harbor. How effective was the attack? Did you do much damage?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well according to the action report, we got several credited hits on the carrier and we got some hits, on a battleship in there. We were dropping five hundred and one thousand pound bombs. I might backtrack and say our big mission that we participated in

was on our way down to Okinawa. The Japanese had the YAMATO in one of their northern harbors. They put all sorts of information out that she was going to sail with what ships she had, support ships, etc., and try to conduct some sort of suicide mission--possibly, the Third Fleet. We were given the mission to attack and try to destroy the YAMATO. So we got word that she had sortied, I don't recall out of what harbor, but it was one of the northern harbors. So, we launched the strike. I was with the leading bombers off of the INTREPID, and we had the air group commander with us. We went all the way up the coast of Japan. The whole group had roughly two hundred fifty planes. We searched up and down but didn't see hide nor hair of the Japanese fleet. So we came back and dropped all our bombs on seaplane hangars and anything we could find coming back down. Then the next day they got pretty positive information that the YAMATO had sortied, so the ship launched another strike. My acting executive officer led that one, so he got in on the action.

Donald R. Lennon:

They found it?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

They did find the YAMATO. They had over three hundred planes, and they sank the YAMATO. I was sorry to have missed it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, I bet that was disappointing.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes. But we had sort of a gentleman's agreement. Since I was acting CO, I would take one flight and my XO would take the other. We weren't going to hog the flights. So that was the most exciting flight they had from talking with the pilots that came back. They had to go through a lot of AA fire. That's pretty well covered in the VB10 chronology. But I know when I went out of Kure Harbor, we exited out through

the northern end of it. They had their AA fire going all along the shore as we were going out, and my air crewman kept hollering, “Put on more throttle, they're getting closer.”

I said, “We're going as fast as we can go.” I was very fortunate. I never found any AA fire in my planes.

Donald R. Lennon:

So after the war was over, you returned to the States?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

And where did you go from there?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

You know everybody was getting out of the service. It was just complete chaos. One day you'd have a complete complement of officers, and the next day they would all be gone, because they had their orders and there was no way you could hold them. I wanted to continue on in aviation, but I got orders to be the navigator on the USS ANZIO, a small KAISER-class carrier. It was going back and forth to pick up material and everything over in the Philippines and bringing it back to the States. On the last trip they went through a big hurricane, losing two of the plane guard destroyers. The commanding officer said he was looking back there in the waves for the destroyers, and the next time he looked--they were gone. They just capsized. So he was a pretty nervous individual, having lost his navigator, and with having me, a new person, coming aboard. I'm sure he didn't have much confidence in me.

Meanwhile in Seattle, we got orders to pick up one of these big Japanese seaplanes that they had brought back. They had it tied down, making the flight deck look like a spider web. We were to take it back to San Diego. I had three days in which to relieve the navigator, because he was a Reserve on his way. In fact when I got aboard, the navigator was in hack. He had been over to the club the night before and had gotten into

a hassle with somebody in the club and unfortunately hit the wrong person over the head with a cue stick, and that happened to be an admiral.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no! Poor choice!

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

It was a poor choice on his part. So he was quickly on his way, and I had to take over in very little time. I had one little green ensign as my assistant. So when we arrived in San Diego, we got orders to take the ship around to Norfolk, Virginia, and put it out of commission. So, we went down through the Panama Canal with no incident. The commanding officer was extremely nervous. I'd go to turn into my cabin at night, and the next morning I'd get up and I'd find we were ten or fifteen degrees off of the course we were steering the night before. I would want to know what was going on, and the officer of the deck would say, “Well the commanding officer would get up about every hour, and he would tell me to change the course one degree to the right.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of dangerous isn't it?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Very dangerous. But when we were passing within three or four miles of all of those little islands down there, he'd get shook up and kept easing off. We did get through the straits out in Guantanamo, Cuba, and were supposed to see a lighthouse about six o'clock in the morning. The commanding officer was ready to reverse course and turn back, when we finally picked it up. When we arrived at Norfolk, he received his orders immediately to some other place. I flew him up from Norfolk to Anacostia. We were making our approach to the Anacostia Air Station there over the Potomac River, and he called me up over the interphone and said, “We can't go over that Potomac River.”

I said, “Why not, Captain?”

He said, “Well, I don't have a life jacket.” I just plugged up the intercom, and I didn't listen to any further conversation. He was very, very nervous.

I ended up as the air officer, and then I became the executive officer putting this thing out of commission. It was a chore because all the crew were leaving, and they didn't want to go through any hassle about putting the ship in mothballs.

Well, when I was just getting ready to be dumped on as the commander officer, I got emergency orders to transfer over as navigator of the USS NORTON SOUND which was going on an Arctic cruise north. I jumped at that and went. The commanding officer was Captain Allen Smith who later made admiral--a very fine gentleman. We went up through the Davis Strait, and our mission was to establish a base, I think it was primarily a radar base, at Thule, Greenland. Then we were to go on up to see if we could find a passageway through the north, around through Lancaster Sound. We spent about a couple of months up there. It's a wonder we didn't run aground. We went in through one little cove one night, anchored, and the next morning there was a big iceberg lying right across the entrance to the sound. We didn't know whether we were going to make it out of there or not, but it finally drifted on out.

We arrived back at Norfolk. I was still hoping that I would get assigned back to an aircraft squadron. They were forming the Antarctic Expedition in Norfolk at the time. Everything had already been set--the ship's complement, the navigators, and so forth. I was sitting around the wardroom congratulating myself, and I said, “I won't have to make that trip.” About that time, they delivered a dispatch that said I had emergency orders to go to be the navigator of the PINE ISLAND. We went north on the NORTON SOUND and then I got orders to the PINE ISLAND. PINE ISLAND made the Antarctic cruise.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is operation High Jump '47

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes, that's what I was on. Captain Caldwell was the commanding officer, and he went on to make admiral. His executive officer was Commander Swartz, and the PINE ISLAND was the task group flagship.

Well anyway, I got my orders. What happened was the navigator that had been assigned to the PINE ISLAND had told the commanding officer the day before I got my orders that he didn't feel qualified to navigate. He said that he would be happy to volunteer as a first lieutenant of the ship, but he did not want to navigate. So the commanding officer had no alternative, except to go and request a replacement. Of course, I was very conveniently sitting about four or five ships over.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you had just returned from the opposite direction.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

So I had found myself getting into the longboat, going over, and reporting aboard the PINE ISLAND. We got under way two days after I was aboard. We went through the Panama Canal and headed south. We arrived at the first iceberg at the Antarctic on Christmas Day. The object of that operation was to make an area map of the whole Antarctic. Of course, the PINE ISLAND received quite a bit of notoriety through the plane that crashed over on the Antarctic continent.

Donald R. Lennon:

There are photographs of that plane crash in that collection.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Is that right? Well, Captain Caldwell was a passenger on that flight. He had gone along as an observer, and so we had a lot of anxiety about the flight. We didn't know for a long time whether we were going to be able to recover the CO or not. It was a pretty hairy operation. We had absolutely no navigational aids down there except what we could get from sun lines and that was about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, what time of year was this?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

This was in January and February.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you had been at the Arctic earlier that same year when it was, I presume, the warmest time in the Arctic.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

From Christmas Day until the first of March. We were in the Antarctic for about three months.

Donald R. Lennon:

How successful could you be in mapping an area that is nothing but ice?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, they apparently were able to get area photographs. In fact, they found a lot of things there that they never even thought or knew existed. They found warm water springs, and in fact, when the crash party were making their trip back out to the pick-up area, they apparently got involved in some of those areas where the ice had melted away.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, compare the navigational problems of that voyage and your Arctic voyage. Was it the same type of problems that you were facing?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

During the navigation up in the Arctic, we had a couple of direction finder stations that we were able to use. We also didn't have the ice to contend with. The Arctic was nothing. In the Antarctic, we could go in so far, and then the whole thing was just jumbled icebergs. I can remember seeing as many as eighty icebergs on the horizon at one time. We were just continually evading icebergs. We had to leave, because the water started to freeze over. After we left the Antarctic we stopped back in Rio de Janeiro and then went on to San Diego.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were you being escorted by any ice breakers or any other kind of ships?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No icebreakers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just PINE ISLAND by itself?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No, we had a destroyer with us, the USS BRONSEN. There was sort of an amusing incident that happened to Captain Dufek, who was the Task Group commander. Admiral Byrd was supposed to be in charge, but Captain Dufek was the senior captain of the whole group. He was really the operational commander. He decided to pay a social call on the commanding officer of the BRONSEN. The only way he could get to the BRONSEN was by high line. So they rigged up a high line, and he was right in the middle when they got a good wave surge. The two ships started to part. Instead of letting the line ease up, the first lieutenant who I had relieved as navigator, held the line tight, and the line just parted. Captain Dufek made about a triple gainer and came down in the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

He didn't last long in the water around there either, did he?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well as soon as the destroyer hit the water, it picked him up. He was in the water only seven minutes until they had him out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow. I believe that was an uncomfortable fall for all concerned.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

That was his second experience. He had gone out on an ice patrol with the helicopter, and when they got back and were hovering over the ship, the rotors iced up; he had to make a landing in the water right off of the ship. His comment to the pilot was: “You didn't even say 'by your leave.' You just stepped on my head and went out first.” He got dumped twice while we were down there.

We ran into some communist activity when we got back to Rio de Janeiro. The head of the vice squad had been put in charge of our reception committee, and he took the commanding officers over to one of his houses of ill repute. They didn't know they were going there, and they lined all their caps up, took pictures of them, and forwarded them

back to the States. When we got back, we were put in quarantine for three days for official investigation of our conduct in Rio de Janeiro. We couldn't even go ashore after we had been at sea for almost six months. Of course everything was cleared up. The communists were just trying to stir up trouble.

But from the PINE ISLAND, I thought I was going to have to make another trip to China. My previous commanding officer of the NORTON SOUND, Captain Smith, had told me that anytime I wanted him to help me, let him know. About three or four days before we were to sail for China, I sent him a call for help. I said, “I need some help. I also need some orders.”

He immediately sent back a message asking, “Where do you want to go?”

I said, “Patuxent River.” So I had my orders to Patuxent River the next morning.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't anxious to return to China again?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No. I wasn't anxious to go anywhere on that ship. And so, I got my orders to Patuxent River, and I was assigned to the Service Test division and was primarily involved with carrier aircraft. I spent two and a half years at the Test Center--from 1947 through 1950. I still wanted to get back into the Fleet, and I was hoping to get back to a squadron.

My director called me up in the air one day. He said, “I need an unattached bachelor who can go on a secret mission, and I need an answer right away.”

I said, “Well, I'm not so sure. Let me think about it.” So, I flew around for about thirty minutes and I said, “Okay.” He still wouldn't tell me what it was. He said he didn't know. Well, I volunteered. That was the last time I ever volunteered for anything, because it turned out to be an assignment for the United Nations in Kashmir in India. I

spent six months over there and became the most proficient jeep driver in the Navy, probably.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your assignment?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

I was assigned to the UN Military Observer Group, between the Indian and Pakistani Armies. You know, they'd gone to war over Kashmir. They are still at war. I don't think they ever solved it. I spent three months in the field with the Indian Army, and then I spent three months up at headquarters in Srinigar, Kashmir. Then when the Korean War broke out, I received orders to Attack Squadron 45, which was in Norfolk, Virginia.

Donald R. Lennon:

But when you were in the Kashmir area, there was really nothing worth reporting on?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

I was assigned to the UN headquarters and we had to go out and investigate. We were in pairs, you know. We would be signed out in pairs and were UN observers. We had about fifty observers, and they were in different stations all up and down the cease-fire line between India and Pakistan. I was down in Jammu, India, in the hills with the headquarters of the Indian general in that area. All we did was get these stupid complaints about somebody having shot somebody. We would then get in our jeep with some young Indian lieutenant who would take us on a wild goose chase, up and down mountains. I think his whole objective was to see if he could wear us out, because it was never where we could take the jeep--we had to walk about two-thirds of the way. A couple of times we had to dig up a corpse or something like that to verify that he had been shot.

Donald R. Lennon:

No treachery?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

No. I don't think they really wanted to fight, but they had a ceasefire. They still have a ceasefire, and Kashmir is still governed by India.

However, I must admit I was in the best shape of my life when I came back. I was about two hundred miles up from Jammu. We'd make a trip in the jeep over those mountain trails about once every couple of weeks to pick up our mail. I'd fly with the Air Force down to New Delhi to pick up supplies and get my flight time in. Then, I make a trip over to the Philippines. About the only interesting thing that happened was when we landed at Saigon right before the French had been kicked out of . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Indochina.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes, Indochina. We landed in Saigon and the French there invited us up to have lunch with them. The Air Force captain was in charge of the airplane. I was flying as his co-pilot, and I said, “I don't really think I want to go.”

He said, “Oh, come on.” They were making attacks, you know. The French were still sending out their planes, and we could hear them making attacks against the Vietnamese there. So finally we went, and we had lunch. As the wine was flowing, I thought to myself, “They are never going to last.” They were being served by these Vietnamese waiters, and you could just see the hate oozing out of their faces when they looked at these people. They were kicked out shortly after that. Generally, I don't have a very good opinion of the UN.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were in Korea, you said you were appointed to an attack squadron?

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Yes. I went back to VA45 as executive officer. I spent about a month and a half in VA45, and then I got orders as commanding officer of VA175, which was operating out of Jacksonville, Florida. I was commanding officer about a year, just little over a

year. We were assigned to the carriers, ROOSEVELT and MIDWAY. We made a couple of deployments to the Mediterranean. When I was relieved as CO, I received orders as training officer at Barin Field, in the Pensacola Training Command.

We had carrier qualification and gunnery training units there. It was a pretty enjoyable assignment. But then I got ordered back to sea as the air operations officer on the CARDIV 3 staff, operating on the PHILIPPINE SEA in WESTPAC. We kept transferring back and forth because it was a CARDIV staff. I made three deployments to WESTPAC in two years.

I married back in 1951, so most of my first two years of marriage was spent overseas. I was supposed to go back to an air group command, but Admiral Hobbs, who was my boss on the CARDIV 3 staff, wanted me to make another deployment. The personnel officer on AIRPAC told me that if I made another deployment, I would miss out on my air group, so I tried to get released from it. Admiral Hobbs wouldn't let me go, so I had to make a third deployment. We were only supposed to make two, and I made three. When I came back, they said I had to go to shore duty; so I was assigned back to the Naval Academy as head of the Leadership Division. I had a little trepidation when I first got orders to the Academy. I didn't feel when I went through the Naval Academy that there was much leadership instructions given, and I felt pretty deficient in it.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you would think that that would have been one of their key areas of concentration.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

It should have been. When I got there, the Leadership Division was down in the basement of Bancroft Hall under the direct supervision of the Commandant of Midshipmen. The only leadership training really was through the company officers, and

there was no formal training as such. They had a military law course and an administrative lecture course. I felt leadership was really being neglected at the Academy, so I spent my whole two years trying to get some sort of recognition for leadership training.

In my Naval Academy days, we had a Captain Boaz who was head of leadership training at the time. He would give us periodic lectures, and I was impressed by the type of information that he passed out. Even that had gone by the board. Captain Shin, who was the Commandant of Midshipmen at the time, was very receptive in trying to improve the leadership course. We revised the naval leadership book that had been there strictly for the midshipmen; but I felt they ought to have a firmer basis of what their leadership responsibilities would be. So I started out by getting two psychologists, two more Marine captains, and a Navy lieutenant assigned as full time billets in the Leadership Division. We started a push to get a firm course based on a definite naval leadership textbook. We knew it would be much more conducive to recognition if we could get some of the civilian instructors involved in it. So we got a volunteer from the math department, Gray Mann, who was very much interested in leadership, and he was assigned to the Leadership Division. We revised the course, and we had the naval leadership book revised, reviewed, and approved.

When I left there after two years, they had upgraded the Leadership Division to a recognized part of the curriculum, which was one step forward. I think it's gone pretty much steadily upward over the years. I belong to the Naval Institute, and I read those reports. The present superintendent of the Naval Academy was the five-striper when I was at the Academy. He has his problems, and with the integration of the women into the

Academy, he's had more problems. I was reading the board-of-visitors write-up, and it seems like over half of the comments were directed at improving the leadership at the Academy. I was glad to see that. But, I spent a very rewarding two years there.

When I left I received orders to Rota, Spain, to open up the naval base, as operations officer. I enjoyed the tour, but I didn't particularly care for the duty. That's where I was selected for captain. I came back and spent two years as the Head of Naval Aviation Training in the Pentagon. Then from there I went as commanding officer of the Naval Air Station in Johnsville, Pennsylvania, with the Naval Air Development Center. It is north of Philadelphia. I realized that I was going to be retiring, so I requested to come back to San Diego. I was on the Bureau of Inspection Survey Board for a year before I retired in 1965. That accomplished about thirty-one years of naval service that I had when I retired.

We had owned a home here in San Diego and held onto it for many years. My children were becoming teenagers at the time, so I decided that I would like to go into teaching. I went back and got my teaching credentials at San Diego State, and then I got a position at Coronado High School and taught in the math and science departments for twelve years. In the meantime, I got my Master's Degree at San Diego State in Physical Science. In 1977, I completely retired after twelve years from teaching and have been RVing ever since.

Donald R. Lennon:

Been camping ever since.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

That's right.

One of the things that has hit me recently was the suicide of Admiral Boorda. I had a hard time coping with that as a reality. I couldn't quite visualize a person who had

reached a pinnacle of success, but felt it necessary to commit suicide because of some apparent discrepancy in his wearing of a Combat V. It just didn't make any sense. It never, ever made any sense to me when he shot himself in the heart. If I were going to commit suicide, I wouldn't shoot myself in the heart--I would shoot myself in the head. It just didn't make any sense until I read an article in American Spectator that said it really wasn't the thing about the wearing of the Combat Vs that was a problem, it was a matter of honor to Admiral Boorda.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think it was honor, entirely. His honor had been besmirched.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

Well, it brought out that the Naval Academy commencement exercise speech had been given by the former Secretary of the Navy--I didn't hear the speech, and I never saw it published in any proceedings--and that in this speech, he made the remark to the midshipmen that there had been a complete lack of support for the officers involved during the “tail hook” operations. Many fine officers' careers had been ruined and besmirched by the allegations made and not proven, and over thirty percent of the leaders of the naval aviation corps had resigned. There had been no support from the higher echelon on this matter. He closed his remarks by saying that there is an admiral who failed to put his stars on the line when it was necessary to protect his officers. It went on to point out an instance where he had forced the retirement of his assistant chief who apparently was one of the finest officers in the Navy, heading up the Gulf War Navy. He had been forced to resign because he would not go along with overriding a decision by one of the congressmen to drop a female pilot from the flight program. In fact it was over this that the admiral, the Assistant Chief of Naval Operations, resigned from the Navy. It was just shortly after that speech that Admiral Boorda committed suicide. The thrust of

this article was that his honor was at stake. That was really what his problem was--that his honor had been brought into question.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't the V at all.

Malcolm E. Wolfe:

It wasn't the V. No, it wasn't. It was the fact that he was brought to task because he wouldn't place his stars on the line to stand up for the Navy, which he was required to do.

If you remember back in 1947, I was at the Navy Air Test Center when the big fight took place between the carrier operations and the big bomber operations. There were two outstanding naval officers who were selected for admiral. They laid their stars on the line standing up for the carriers over the other one, and they both failed in promotion. In fact, they were both outstanding naval officers, but they laid their careers on the line by going up and refusing to let the process be politicized. They won their case, but they lost their careers in the process. I think this was really Admiral Boorda's problem; he had become politicized. I guess he just couldn't take the heat. I guess that was it.

[End of Interview]

Capt. Wolfe is my father. I have confirmed the details of his oral history with him, much of which can also be found in his autobiography, "Splicing the Mainbrace." July 2011