| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW # 198 | |

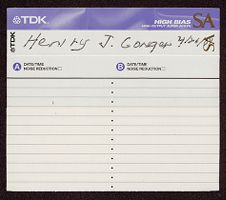

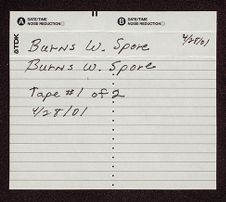

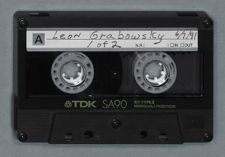

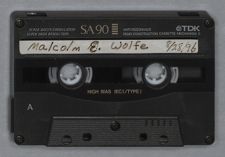

| Commander Henry J. Conger | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 26, 2001 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Don Lennon | |

| Transcribed and edited by Christine Bendle |

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell me about your background in Georgia and some of the comments you were just making about your enterprises as a teenager, and what you led you to the Naval Academy, and some experiences about your Naval Academy and we'll move from there into World War II.

Henry J. Conger:

Okay, I can start with that. I was born in Norman Park, Ga. and shortly after that we moved to Tipton, though I spent most of my childhood in, up until I was 18 years old in Tipton, Ga. My mother and father got a divorce when I was 4 years old. My mother and my brother and sister and myself moved in with my grandfather on her side and we lived there for two years. This was in, say, around 1920. I do remember the soldiers coming back from World War I. I had an uncle and he came back with all his equipment and he would point right here and "when you get that high I'll give you this equipment," so I remember that very vividly. During that time also we made a trip to Arcadia, Florida in an old touring car. Oh I don't even know whether it was a Packard or...but we had eight people in it and

we went down to see an aunt that lived in- had just moved down to Arcadia, Florida and it took us three days to go from Tipton to Arcadia. We stopped in Lake City and Ocala before we went on down there and most of the roads were unpaved at that time. In fact I think I saw my first paved road on that trip. After two years with my, living with my grandfather we moved into the house next door to where my grandmother on my father's side lived and he was living with her, so we lived right next door to him. Even though they were, my mother and father were divorced they were friendly, very friendly, always stayed friendly and we were in and out of both houses. So I got to know my father much better than normally I think with divorced parents. So I went to the grammar school there and I fell in love with my third grade teacher, of course, and when I graduated from high school- well before we graduated from high school my brother and I were, we tried to make as much money as we could. We were, I don't know what you would- the word, the exact word to use it but we started selling peanuts on the streets and we had our regular customers, five cents a bag. My mother and sister they- we put 50% of it in the bank as a savings account, and we could spend the other part. We branched out from there and bought the concessions to sell peanuts and cold drinks and things like that at the ballpark for the baseball games and the football games, and we branched out from there to the newspapers. We sold the Atlanta Journal , the Macon Telegraph, the Florida Times Union, we had all three newspapers. We were the only distributors. We had over three hundred customers in a small town and then with other things and not having any time to spare we bought the concessions to sell cold drinks and peanuts and cigarettes, even though we were young, cigarettes at the tobacco markets.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow ya'll did, really?

Henry J. Conger:

Well anyway we did that for four different seasons. They had the tobacco markets in use and when my brother graduated from high school my mother sent him on a trip to the Olympic Games in Los Angeles. When I graduated she said, "Well we've got enough money for you to go to the World's Fair in Chicago." So two friends of mine, one of them is Winston Tobacco Group-one of the sons there, and a doctor friend of mine. He's a doctor, was a doctor: Jack Bowen. Both of them was one year older than I was. We had an old Model T Ford and we drove from Tipton up through Norfolk, up through New York. We camped out up to Niagara Falls and across to Detroit, and then to the World's Fair.

Donald R. Lennon:

You took a circuitous root!

Henry J. Conger:

That's right. And then we came back. Funny thing, our first night we were doing a lot of camping. We got just above Atlanta and we saw a light way down there. I mean it was a nice, level spot and so we camped there for the night. The next morning a policeman woke us up and said better get out of the city square before the mayor gets here or he'll throw you in jail! But anyway, coming back from the World's Fair our brakes gave out on our Model T, but we made it back to Tipton even with the brakes out. Of course in those days you didn't go very fast.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right and there wasn't much traffic.

Henry J. Conger:

Right. And so when I graduated I didn't know exactly what I wanted to do so my father, as I said my father and I were very close, even though they were divorced. He said, "Well Jack, what do you want to do?" And I said, "Well I'd like to go to either West Point or the Naval Academy." He said, "I can get you in right away." He said- Judge Cox was his roommate at Mercer University and my father got a law degree, and Judge Cox came out a Congressman. We called him Judge because he was a judge down there before he went to Congress. And so he called him up and said, "Look, bring Jack over," and so we went over.

And he said "Well Jack, what are you most interested in- the Army or the Navy?" I says "Judge," I've always called him Judge, I says "I've never been on the ocean. I'd rather get the Naval Academy." He said "Okay, I'll appoint you." Just like that. I said they were roommates; my father and Judge Cox were roommates. He gave me an appointment for the Class of '39. I went to prepare myself. My mother sent me to Marion Institute over in Marion, Alabama, which had a very good record of sending students to both of the academies. So I got up there, passed everything, got up there and they turned me down because my teeth were crooked. Well I had what they call malocclusion of the teeth back here, I didn't even know it. So I was really disappointed. But we went back and Judge Cox said "Well get your teeth straightened and I'll put you in the next class." So I got my teeth straightened. They put braces on them, straightened them, so I got in the Class of '40. So I started out spending a year in the class of '40 and during the first part of my second year, youngster year I got sick and they sent me over to the Naval hospital there and I was in the hospital from, might say from Thanksgiving to Christmas. And so they figured that I would not be able to make up my work, being out that long. So they put me back into the Class of '41. As you know we graduated ahead of normal tour there. During the class of '40 we made my first trip to Europe on the ARKANSAS, and one thing I remember very vividly there. We went to England, went to Torquay, England and then went through the Kiel Canal where we ran aground and we had to wait for the tide to come up. It was only I think only two or three feet in the difference in the tide there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I reckon the officer of the deck got reprimanded for that, didn't he?

Henry J. Conger:

Well probably, I was a midshipman. I was one of the younger midshipmen then so I'm not for sure. But anyway we got to, went through the Kiel Canal and then we were at Kiel there where they had their submarine base. And of course they had already been

helping the Spanish in their insurrection down there. We sailed from there, from back through the Kiel Canal and down to Madeira Island and I remember when we went by Spain and Portugal there we had a big American flag on top of the ARKANSAS so that we wouldn't be bombarded. 'Cause you never know. And we kept lights on it all night long as we went by there and we went to Madeira Island which boy is a beautiful island. I've been back a couple of times since...very nice. And from there we came back to the United States. Our Youngster year we were in destroyers and one thing I remember there, we came down to Norfolk and Joe Taussig was a classmate of mine and we were on there and Joe says, "Let's go over and see my father." He was the Commandant at the Naval base at that time and so when we had liberty here all of us go and our commanding officer, I forget his name, said, "Where are you going?" And Joe said, "We're going over to my house." He said, "No Way!" and he kept us aboard ship. Well Joe got off and called his father and his father called the commanding officer and said, "Are you countermanding my orders?" And about ten minutes and all of us were off the ship. Little things...

Donald R. Lennon:

Joe Taussig was something else!

Henry J. Conger:

Oh he was! And Joe remained a very close friend of mine the rest of his life. One time we were at a banquet, a reunion of the Class of '41. We were all sitting in the mess hall eating. One of the young midshipmen came up and was- it was after we were finished eating, picking up the desserts, I guess, and he says, "I need a high ranking officer to, so I can get up and take this up to the room. Would one of you do it?" I says, "Hey Joe, you are the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, why don't you sign it for him?" And Joe says, "Fine let's do that!" He signed it and also gave the midshipman a card so that he would know that it was actually him that signed it. So that Joe Taussig was that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

He would bend the rules.

Henry J. Conger:

That's right and he was, how do you say... I like that fellow.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the officer that would not let you go ashore know, did he know who Joe's father was?

Henry J. Conger:

Yes. He thought we was imposing on him, you see.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh okay.

Henry J. Conger:

When Admiral Taussig called him up we didn't take long to get ashore. And you know there Taussig Blvd is named after him too. Well that's about all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any, any thing in particular about either the instruction or the- I know a lot of class members or Naval Academy graduates comment on harassment during their plebe year and things of that nature.

Henry J. Conger:

Well we were harassed some but we...

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have a bad experience?

Henry J. Conger:

Well not too bad. We were, when we played Army that year we won. And of course all- they didn't harass the plebes anymore after the Army-Navy game for quite a while, until after Christmas, you see. We had a spot there for about three months that we could walk around like upperclassman. We lived through that hazing, they called it then, just a part of life there. I can remember we'd be sitting down at a table and the first classman at the table would say, "Put your chair out!" So you had to put your chair out and sit like this the rest of the meal. That was probably worst on your legs than anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, right.

Henry J. Conger:

One harassment or hazing thing there, we had to make the sauce for the salads and everything and little things like that. You always had to walk in the middle of the hallway and cut corners square, always after a basketball game or something the youngsters, the second class group it wasn't the second class the Youngsters were the third class group, they

would come in to your room and put you in the showers and things like that. We just took that as just part of life.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well I know Captain Taussig thought very highly of Uncle Beanie.

Henry J. Conger:

Oh boy, well everybody did! Everybody liked him. He would, boy he would pull something on you and laugh and laugh and laugh. He had a habit of checking the back of your shoes and if they wasn't shined he'd give you a demerit. I was very lucky I only got, all the time I was at Naval Academy I only got fifteen demerits. Which is very low I think.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sure, yeah

Henry J. Conger:

And I only had to take one of the punishments. When you had demerits, you had to, in the afternoon you had to walk back and forth with your riffle there on the place where it was designated for the punishment. If it was real bad punishment they took you down to the brig, not the brig the ship, one of the old ships that was in the Spanish-American War. The REINA MERCEDES is the name. I never got there.

Donald R. Lennon:

You never got that far?

Henry J. Conger:

No I never. We had one classmate, I won't name him he was in there about four times. I never made that I just had to make one punishment trip one time back and forth for twenty minutes for punishment for something. I can't remember why I got that one but that was all at that time. When I graduated of course we went home for a short time and in those days I took the train. They didn't have the aircraft going across country and I took the train from Tipton to Chicago and Chicago to San Francisco.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you'd been assigned to the IDAHO?

Henry J. Conger:

I had been assigned to the IDAHO on graduation.

Donald R. Lennon:

And where was it? At Pearl?

Henry J. Conger:

At Pearl Harbor. There's five of us went there: Myself, John Duke, John Dardy, ensign by the name of Grant, and hold on the other is on the tip of my, anyway one other and we were in Pearl Harbor about a month when we were going out on weekly, we'd go out on Monday and usually come back on Friday. One incident that happened, we were in a simulated war games and those times the battleships would fire at a sled being towed by another battleship or another ship and on our ship we had a lot of observers, we had several admirals observing and we were the target ship. We were, people were firing at a target back of us about I guess it was a thousand yards back of us and they forgot to put the offset on and they straddled us. Two shells fell in front of us on the port side and one fell on the starboard side and it shot, oh one fell over and the other fell short. You should have seen everybody ducking and heading for the...

Donald R. Lennon:

I'll bet.

Henry J. Conger:

Those days didn't have the communications you have today. I don't know exactly how they got the word to them but they stopped maneuvers right away.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow, now how old a ship was the IDAHO at that time?

Henry J. Conger:

Well it was a World War One ship and it was modernized in oh 1930's, I forget the exact dates. When it was first built it had though a big cage and a mast and all and of course all of them were taken off and just like it was when I report it. But one month, a little over a month after I reported aboard we steamed south for our regular weeks tour. We were supposed to return on Friday. We had a officer who was going to get married on Saturday but on Thursday we didn't turn around. We headed east and went to the, through the Panama Canal. Three battleships the IDAHO, MISSISSIPPI, and I forget the other one now. There was three battleships and we steamed up the coast and off of North Carolina.

We picked up several transports with marines on them and six destroyers' escorts and headed for Iceland.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was totally unexpected?

Henry J. Conger:

Yeah it was for us because we were supposed to go back onto Pearl Harbor. We were under complete silence. We blacked out all the markings on the ship as we went through the Panama Canal. There were some Japanese merchant ships right at the entrance. They sent word I'm sure back to Japan that three of the American battleships had left Pearl Harbor. We went to Reykjavik and we stayed there until December the 8th. But we were in and out. We didn't have radar but we patrolled between Iceland and Greenland. We'd go out for about ten days, ten to fourteen days at a time and patrol there. Now we were supposed to take no action. If we saw anything we were supposed to notify the British that certain German ships had passed through. Well the Germans had radar and so they could pick us up long before we could spot them. Of course we never ran into any of them and that was the same time that REUBEN JAMES sunk up there. We had a classmate on there. The day after Pearl Harbor we headed back to the United States.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you weren't involved in any kind of confrontation?

Henry J. Conger:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the North Atlantic?

Henry J. Conger:

Well we, a few times we dropped depth charges over the side of the battleship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why?

Henry J. Conger:

Because the destroyers with us said that they had picked up sonar things from submarines so I don't think anyone knew what we were dropping or why. Maybe just to scare them away in case they were close but that was the only...

Donald R. Lennon:

Probably did considerable damage to those fish, those whales or whatever.

Henry J. Conger:

Coming back from Iceland we hit the second worst storm that I'd ever been through. The battleship bridge is about a hundred feet above the water level and we were getting green water over the bridge. We lost two OS2 planes that were had used spotting, over the side because all the whale boats over the side by the heavy seas. We got to Norfolk and they took off our fifty caliber machine guns and put on 1.1's they call them. We went back through the Panama Canal and went up to Long Beach. They took off the 1.1's and of course this takes time and put the 40mm's on board. So we headed out. It was about April of '42 we headed out for the South Seas in the Pacific and we trained with those 40mm. I was the safety officer, but I was in engineering but they used us as safety officers. One of the guns malfunctioned on the one that I was safety officer on and it hit into the shield and exploded all the ammunition that was in the little turb-type and I was the only casualty.

I was, a piece of shrapnel hit me right here.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh yeah there's still a scar.

Henry J. Conger:

Knocked me out. But before it hit me as soon I saw those guns going down I turned off, but it's too late to trigger the, cut everything off on the guns and I know everybody said I had blood I don't remember it all, had blood all over. They didn't know if I was dead or what. It was only a surface scratch more than anything else.

Donald R. Lennon:

You're lucky.

Henry J. Conger:

I was very lucky because if it had been a little deeper it would have gone right in you see.

Donald R. Lennon:

Or if it had been a little bit lower it would have taken out your eye.

Henry J. Conger:

That's right. Our sailors though did a wonderful job. They were picking up these burning 40mm projectiles about this long and throwing them over the side. I think they saved us more from more, the worse damage. But we got down to South Pacific and we

were the older battleships. We were what they called the back-up group. We sat around there off of Efate, which is in the New Caledonia group. During that time we made one trip to Australia to Sydney for recreation. We were the back up group for the fast carrier group and the fast battleships, which they were bringing out at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

NORTH CAROLINA and the WASHINGTON

Henry J. Conger:

That's right, all of those. Suddenly we got orders to go to Alaska. The three battleships, the NEW MEXICO was the other battleship, NEW MEXICO, MISSISSIPPI and the IDAHO. We headed up that way. We had no heavy weather gear on board everything, we'd been living outside because the, it was too hot down in the South Pacific to sleep down below so all the sailors and everything sleeping at night up on the deck. We got up there. They sent a transport up there with the heavy weather gear for us and from then on we were, Adak was our port, we went- let's see another one along the coast, anyway we patrolled for 96 days between Attu and the Cormandorskis(?), the Russian peninsula there. We had no contact with the Japanese although one cruiser group opened fire and for thirty minutes they were shooting at pits on their radar screen. The Japanese were fifty miles south of where they were shooting at in that time. They thought the Japanese fleet was right there but actually we found out later the Japanese fleet was about fifty miles south. We were stayed there until the army and or the- I guess it was the army group that moved in there too and took, retook it.

Donald R. Lennon:

In what period are we talking about time wise, where exactly?

Henry J. Conger:

I would say, I think that was in '43. I t could have been because right after that we went back to Bremington where we were in overhaul for three months and oh by that time shortly before we left for the second time before we left the South Pacific we did come back to San Francisco one time. I got married in San Francisco. I was married for 14 days and

shoved off. When I came back 14 months later I had a small baby, a small boy. We went back to the South Pacific and we were a member of the bombardment group for all the islands that, Halawa, Tarawa, Eniwetok, Guam, Saipan, Okinawa, all of these. I think I have got picked out of that either ten or eleven battle stars that the ship picked up so I was able to wear them on there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now what was your capacity on the ship this time?

Henry J. Conger:

Well I was in engineering for the first part. I was on board the IDAHO probably longer than any other officer. They always had to keep a certain number of people that could coordinate. Because every three months they took off a third of your crew and put brand new people on board. I started off in engineering as the B division officer. I had eight boilers under me. I had eight chiefs, plus a ninth chief for overall coordination and a chief warrant officer who had been a lieutenant commander in World War One. He was my junior officer. But I told Mr. Shackleton, that was his name, I says, "You know more about these than I'll ever know. You handle everything there. I will handle all the paperwork." I mean here I was a brand knew ensign at that time when I took over there. Well I went from there to an electrical officer and from electrical officer I went to my last job there where I was First Lieutenant and damage control officer and when we went to Okinawa that's what I was and I got orders to BT Tax for a reassignment to go back to San Francisco. The ship had not been hit in all that time. We'd been under fire by kamikazes or they were coming close by but we- never too close to us. We had one torpedo that went under our stern and hit the COLORADO, which was about three thousand yards from us or the distance. I don't know if they were aiming at us or just had hopes of hitting something. They hit the COLORADO and damaged there the propellers but we could see it as it went by. Some of us standing back there watching saw this torpedo going by. I was detached during the Battle

of Okinawa and they were hoisted by, during their attack they were hoisting all the gear that I had accumulated four or five years and never had the chance to get rid of over the side and they dropped it in the water when the alarms were sounded. They got it back up and most of it was ruined. I got off the ship and went aboard the HENRICO, which had been hit several days before, and it had a staff with an Admiral and fourteen, fifteen officers. it had been hit about four or five days before I went aboard. The Admiral and all his staff was killed. The Captain, they were all at dinner, the Captain of the ship and everyone aboard. The senior officer aboard was a Junior Grade Lieutenant, he was the assistant navigator. He was in charge of the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were they hit by a kamikaze?

Henry J. Conger:

Yes by a kamikaze and by dropping the bombs. One bomb hit in the wardroom the time they were eating. The other penetrated and hit somewhere in the bottom of the ship. I went over there and thirty minutes after I left the IDAHO got hit by a kamikaze so I was in between you might say. Not much damage I understood later on. This JG he was commanding officer although he had more senior officers. At that time I was a lieutenant commander. We all assisted. Several more senior officers aboard but he was in charge because he was the senior officer aboard. He had to steer the ship from the fantail and it took us thirty days to get back to San Francisco. I was reassigned there. I reported in for reassignment and the detail officer said, "Well we can give you ten days leave and then you're going back to a ship in the South Pacific." I said, “No way.” I said, “I've been out there since1941 and here it is 1945, and I says no way. I've had no leave or anything, and there's no way. Who's your superior?” He took me up to some commander and he said, "Well we can give you thirty days." I said, “I need more time off than that. I says I've been married and I haven't seen my wife in fourteen months.” He upped me to a Captain who

said, "We'll send you back to gunnery school in Washington, DC." I said, “That's fine.” I had brought my wife.

Donald R. Lennon:

You hadn't had any shore duty at all, had you?

Henry J. Conger:

I was just aboard ship all that time, aboard the IDAHO. There were two officers on board and I was the senior one that had been on board for all that time that knew everything on the ship. I went back to Washington, DC at the gunners' school and at that time the war had ended. Boy there was celebrations in Washington, DC at that time. I was scheduled to go to a cruiser for gunnery officer and suddenly my orders were changed. I went to the TARAWA as the first lieutenant and damage control officer. The TARAWA was being commissioned in Newport News. I went down there and we, I had three more months there. The war had ended by that time so as soon as we were commissioned they sent us to Japan as part of the occupation forces. We were in and out of there for quite a while. I had a normal tour of duty on the TARAWA and then I went back to the battleship and cruiser staff in...

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now any particular incidence involved in the occupation force of Japan while you were in Japan?

Henry J. Conger:

Not really, we got to Tokyo where we saw everything was bombed out and one thing, we went to Hiroshima where the second atomic bomb was dropped. I picked up a couple of souvenirs, a couple of bottles and things like that. We had our recreation. We went to Singapore for recreation. We would not go on the, we went to Saint Charo where we went in there on the TARAWA but we could not get into Singapore for recreation so they sent us down on destroyers. I made two trips down there during the occupation. it was just, I would say a normal tour, nothing spectacular. When we got to Tokyo we'd take a little train from Yokosuka. We'd go by general McArthur's head quarters but we didn't dare

go in, he ruled that place with an iron hand I understand. I left there and I say I went back to the battleship and cruiser staff where I spent eighteen months. This is getting on up there that was in 1948. Then I went back to Washington, DC as a member of the Board of Inspection and Survey and the recorder and also a board member of the Board of Inspection and Survey. They were putting a lot of new ships in commission at that time so half of our duty was inspecting old ships to make sure they were sea worthy and our other duty was to inspect the new construction. Put them through the sea trials and make sure they were accepted, would be accepted by the Navy. It was up to us to turn them down or accept them. The only ship that we turned down was one built in Charleston. We turned it down twice because it did not meet the specifications. We would check them out in their ship building places and then when they went down to Guantanamo for their under water training we had to fly down to Guantanamo and go aboard and put them through the sea trials. We went down there so much that we had regular quarters there, officers quarters there at Guantanamo. We put two or three cruisers through their commission and trials, one aircraft carrier and several destroyers. I was on there for two and a half years and I was still Lieutenant Commander then. I got orders to the USS PORTER as the executive officer. This was in 1950. I was on board there, I was on the pre-commissions. Here they were building up for the Korean War and they was putting all these older ships back in commission. I reported to the Porter in Charleston and we got a better crew and we took it out for sea trials and things like that. One instance there, we were bringing it back in the harbor and our Jaro computer failed. The magnet had not been compensated for so we didn't know that and a fog came up and we were supposed to come back in. I was the navigator and the executive officer, the navigator. It was, we were worried about running aground so we were supposed to go back in. Instead of going back in I had somebody up

dropping something over the side to make sure we had depth of water. I was steering pretty close to what I thought was the way the wind. When we got that close I just dropped the anchor and we dropped the anchor and we were about one hundred yards off the entrance. We didn't want to take a chance of running aground there you see. I was on the PORTER for quite a while. We were coming back from Guantanamo and I got orders that the commanding officer of the LAFFEY. I thought I would pick up the LAFFEY in Norfolk but I was transferred at sea. I don't know what happened to Commander Hallback but he was detached at sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's kind of unusual, isn't it?

Henry J. Conger:

It was. I was detached from the PORTER and put aboard as commanding officer at sea, no ceremony. I just took aboard and he slewed me and I had charge that was the way I became commanding officer of the LAFFEY. We pulled into Norfolk and we trained to go to Korea. About fifteen or twenty days before we go to Korea I lost over half my officers. When I say I lost them they were transferred to other...

Donald R. Lennon:

That many though...

Henry J. Conger:

Other construction that would be in the...

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this 1951 or 1952?

Henry J. Conger:

Latter part of 1951, I believe, I could be wrong. I've got the dates in my files.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well you had the Round the World Cruise in 1952.

Henry J. Conger:

Well we left Norfolk, Virginia. I didn't have a single officer on board that had ever stood an officers watch deck under me. I had a brand new CIC officer. I had a brand new executive officer, all the rest of them had been transferred to other ships. I insisted on getting a good CIC officer. I got the man I wanted who happened to have been the instructor that instructed me in CIC in my training getting ready for this trip and all. We left

there and we did nothing but training all the way through the Panama Canal and Hawaii and out to Midway and on to Japan and then on to Korea. This is where I hit the worst storm, I mentioned my second worst storm, the worst storm was after we left Midway. We had our division of destroyers and we hit, we were rolling about like this, fifty-seven degrees each way, that's a pretty good role. We lost eight depth charges over the side and whip mode available. We lost all the eating equipment, plates and things in the wardroom. Everything was just going back and forth. A battleship just roles, a destroyer goes this way and jerks. We got through the storm okay and we joined the Seventh Fleet out there and we spent a month with the, two months just patrolling with the carriers being guard for them you might say. I was ordered into Wonsan Harbor as, there was two of us the MADDOX and the LAFFEY were ordered in there. They always kept two destroyers in there. We had marines in there that had occupied an island in the Wonsan Harbor. Our job was to keep the railroads cut from North Korea, North China down to the battlefront there. We would steam around Wonsan Harbor and there were two or three days- we would get fired on by the North Koreans. They were in mountains. We could see them up there loading their guns and our orders were never to shoot at them until they opened fire on us. We broke the rules a little bit. When we saw them taking the mussel covers off the guns we opened fire on them.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's kind of a handicap though being ordered not to fire!

Henry J. Conger:

It was, we were ordered! Well we were in there for thirty days and the first few days we just opened fire a few times and then at nigh they would float mines down on us. We would pick them up with our radar and if they came within a certain distance, if they came too close and we exploded them they would damage the ship. So we had to open fire on

them when they were far enough away that we'd explode them in the water before they could do any damage to us and we exploded four or five.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had to have more extra men on watch so you could make sure you got them all.

Henry J. Conger:

That's right, absolutely. One time we had one to float, oh pretty close. I was afraid it would come in to the ship so we sort of steered away a little bit. We didn't want to attract it. We didn't fire or do that one but we had been in there about fourteen or fifteen days and they opened fire with us on everything they had. We had three batteries. We were surrounded on three sides with the North Korean batteries. They were using army pc's and they could just shoot one direction so when we passed that way that's when they would shoot. We opened fire on them and we were under attack for five hours and ten minutes. We silenced or knocked out every one of the batteries that we know of because the rest of the time we were in there, for fifteen days, we were not opened fire on again. We got a nice letter from the Chief of the Seventh Fleet saying, “Congratulations, you've been under fire longer than any other ship in the Korean War!” It's in my records there. The dispatch that we got, I kept that. They congratulated us on that and at the time we silenced everything and it got to be night and I asked to go out to re-arm. We had shot every pod and shell we had during that time. We had also shot some of the star shells just to let them know that we were still shooting at them. I was turned down because they said well stay in over night and come in the next morning. Here we were a bunch of sitting ducks. We had no ammunition that we could have fire on them, but they told us to stay in. All during that time...

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you, in a situation like that, do you replace or replenish your ammunition?

Henry J. Conger:

Well every fifth day they had a transport and an ammunition ship that came outside and we would go outside and take on ammunition, take on supplies, and other things and fuel and then go back in you see.

Donald R. Lennon:

But in the interim of that five days if you used your ammo you were out of luck?

Henry J. Conger:

Yeah that's right so anyway they let us go out the next morning. Well the reason they didn't let us out, the ammunition ship probably was not there at the time. We stayed in and went out the next morning, re-armed and went right back in. We were not fired on the rest of the time I said. We think that between the MADDOX and the LAFFEY we knocked out all their batteries. The thing about it is we had a regular routine there. When you was opened fired, normally we just steamed in slow circles but when you're opened fired you put on full power and make figure eights or straight runs, sudden turns-everything to keep. We were not hit but the shrapnel- they came so close shrapnel knocked the- here I am on the bridge- it knocked the windshield out of the bridge right in front of us. We picked up two big basket fulls of shrapnel that exploded in the water and bounced on the ship, but we were never hit, never no direct hits you see. It was pretty close. It was a little scary but not too bad. My officers and crew did very well. I had one battle there. I got a Bronze Star. Four of my officers got Bronze Stars and the ship got other recognitions and all. They say we got decorated for that. We went back and stayed with the Seventh Fleet for another couple of months and then they said that we had done a very good job so they sent our squadron back through our division, back through by Singapore and the Suez Canal instead of us having to go back through the Panama Canal, which made it an around the world trip you see. One thing of interest there, we went into Bahrain and as we were leaving Bahrain I had a sailor that had appendicitis there and he had to be evacuated. There was no way of evacuating him. We had, the seas were so rough that the air force could not come in and pick him up so they kept monitoring us. They said go to Aden, make a run for Aden and that was quite a distance away and so we put on full speed. I think we could make about thirty knots. We kept it up all the way to Ayden. We pulled into Ayden and I bet we didn't have a bucket full

of fuel left. We got the sailor there in time and the ships, all the merchant ships were monitoring us on our travel. The air force kept wanting to pick him up but it was too rough of a seas. We got him there okay and later he rejoined the ship. We got to Port Said and went through the Red Sea there and through the Suez Canal and we docked in Egypt the day that King Faroke got kicked out. We thought we'd go ashore for recreation and all but based that we had soldiers, the Egyptian soldiers lined up, they would not let us ashore. We didn't know the reason so the embassy people came aboard and said well they've just kicked King Faroke out so they thought we were maybe there to help put him back on the throne you see. There we were during it. We stayed there three days and under tension all the time because those soldiers wouldn't let anybody ashore. We went from there to Istanbul and from there to Naples and from Naples to Cannes and then to Gibraltar and then back to the United States. That was a very nice trip, very nice trip.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of a reward for your actions.

Henry J. Conger:

Right that's what they said. They just said you did a good job so we are sending you back around the world. Well we got back to Norfolk and then our next most important thing I think we were selected, LAFFEY was selected to go down to the Bahamas during Queen Elizabeth's coronation. We represented our government in the Bahamas for her coronation. That was nice because we went to so many parties and the crew got so much recognition and all. It was very nice. I never will forget. One of the dinner parties there I sat next door to the Countess, I forget now, Countess de Sofia, it'll pass by, she was the girlfriend of Gary Cooper. Here she was a countess and she wore I remember a diamond necklace, diamonds that big. I made a comment on it and all and she said, “Well I only break this out for very special occasions and the Queen's coronation is one of them.” She was English, Defosso, Countess Defosso that was the name. She was a very nice dinner partner. Getting up in age,

of course Gary Cooper at that time was getting up in age too. I came back there I had the commodore was on board my ship. He was the only one that spoke Portuguese and Spanish so we made tours down in South America for Goodwill Tours, because he could converse with the people there. We made trips to Jamaica and Carousal and Caracas and places like that for Goodwill Tours. Then when I transferred from the LAFFEY I went to the Naval Academy for as the officer- well the engineering department. I was not the, I was head of the physics committee. I didn't know anything about physics. When I reported there well they said, “You got three choices. What are your three choices?” I said “Well I'd rather be in the executive department or in gunnery or in navigation.” They looked over my record and I had quite a bit of engineering experience on the IDAHO and the TARAWA so they said, and the Board of Inspection Survey, so they said well you'll make a good physics teacher. I said oh boy, physics was my worst subject. I had “Slip Stick” Willie Thompson, he was a senior, we called him Slip Stick Willie even when I was- he was there when I was a midshipman. He was the senior civilian in the department and under his tutoring and some of the physics civilian teachers there I learned physics in three months. I was a good physics teacher. They have a way of teaching you there that you don't teach to the youngsters the way they taught me. I ended up during that time, well at that time that was when they discovered that my son, I had two sons at that time in fact I had a daughter too, born two days after I got there. The son developed Hodgkin's disease and we were on a vacation down in Dallas, Texas, where my first wife lived. The doctor's gave him five years to live and he lived exactly five years from the time they discovered that he had it. I stayed at the Naval Academy for two and a half years and then I went to the Atlantic Fleet as the West Land Assistant Operational Officer. West Land which was the NATO group. It operated

under Sun Clan Fleet. It was in the operation department of Sun Clan Fleet. My job there was coordinating all the exercises with the foreign, with England and the Dutch and others.

Donald R. Lennon:

This would be around 1956?

Henry J. Conger:

Yes, right. So I spent three years in that, let's see I was detached from the LAFFEY in 1952. I went to the Naval Academy for three years or so. It was 1956 when I went to the Sun Clan Fleet at West Land. So I stayed there and I coordinated one exercise, Strike Back, and I had a file that thick. The admiral would say what about such and such and I could just flip. You didn't have a computer so I could just flip my papers and find exactly what he wanted at that time, Admiral Wright, little things like this. We had to stand duty watch in his office at night and Ollie Burt was the Chief of Naval Operations at that time and Admiral Wright would say if Ollie calls tell him I just left no matter what time of day or night! Admiral Burt, boy he stayed up all hours of the night. He would call at one o'clock in the morning or late at night, “Where's Jerry?” “Admiral he just left!”

Donald R. Lennon:

I would get kind of suspect after a while.

Henry J. Conger:

Yeah, I guess so. Well we might have varied the words a little bit but you know what, he called one time and I was on duty then and I said- Admiral Burt laughed. I was on Admiral Burt's staff when I was in the Naval Academy on a midshipman cruise, so I got to know him pretty well. In fact on that cruise he found out he was going to be Naval Operation's, Chief of Naval Operations so we made the midshipman cruise to Spain, Portugal, and England and places like that. He knew that he was going to be Chief of Naval Operations at that time. He would call me. Every time you hit a port it had all these ceremonies and everything. He said “Jack you go and visit all the ships. Me and my staff we're not going to have time.” I was part of the staff but I was in charge of midshipman. He said “You take care of them.” Boy in Spain I never will forget they had about six or eight

ships and every ship you went aboard they offered you brandy. I got where after the first ship I would just sip it, but then I had to invite them back aboard the MACON at that time for coffee. So I made the tour of the six ships and I guess I could still stand up. Then I invited all of them, the commanding officers and so forth, aboard ship for coffee. It was the only thing we served you see.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say you were probably after a while thankful that you weren't allowed to have legal alcohol at your age.

Henry J. Conger:

You said it. I got to know quite a few people that way. We went to Holland where I had more friends in Holland than anybody else on the ship because I don't know I just got to know quite a few Dutch officers when I was down in Carousal and all, and Aruba. That was when I was on the LAFFEY. I got to know them all. When I went to Holland I had a, it was a big attachment there that came aboard to see me.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well was language ever a problem?

Henry J. Conger:

No, I always spoke English and always found that most in Europe, most of the educated people speak English.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know they do now. I didn't know whether back in the Fifties they did.

Henry J. Conger:

Oh yeah they did even then. Like my wife she says in Germany they were required to take three languages, the educated people were required in Germany to take three languages.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's a shame we aren't.

Henry J. Conger:

That's right. I can remember back as a midshipman when we went to Berlin in Kiel, they put on a show for us and they put it on in English. Here's six hundred midshipman. They put on the show for them in English. We went back stage and met all of them. We asked, “Well here we are in Germany but yet you put on your program in English?” He said

“Well if we were confined to one language we would be restricted to that country and we would not be able to perform in other countries. So we can speak English, we can speak French, we can speak Italian, we can speak German and so forth, all these actors and so forth.” So in other words a lot of people would be able to speak at least three languages.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've always been impressed you could even go into a department store in Germany and always find English-speaking clerks.

Henry J. Conger:

That's right. I had one yesterday that I got embarrassed. My wife and I were in Berlin, no in Hong Kong, not Hong Kong, Hamburg and we were assigned a place to stay. There you came in on the airport and you had not made the hotel arrangements. They would look it up and say okay you can go to this one. Well my wife knew that hotel. We got there but she- we had rented a car. As we drove by she said oh there it is stop! I stopped and she got out and forgot to take her purse or anything to check in. I said well I'll drive around the block and come back. I drove around the block and every street we hit was a one-way street going the other direction. Oh boy, I had the hardest time. It took me an hour and a half. I didn't know the name of the hotel.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no.

Henry J. Conger:

I didn't even know the name of the street it was on, but I kept, we had just passed over Kennedy Bridge, Kennedy Bridge there. I couldn't find a taxi cab driver or anybody that knew English. I was having trouble, but it took me an hour and a half to get back. I finally got back and I kept saying, Kennedy Bridge, Kennedy Bridge. Finally one person, I stopped in all these cab places and finally one says oh. He pointed how, told me how to get there. He spoke a little bit of English. I got there and I came back. At the hotel they wondered what happened to me. They had checked the hospitals, everything, because here I was gone an hour and a half and here's my wife sitting out there. She was cold. She was

sitting out there. The bellboy let here have his coat. Well anyway, that's one time I couldn't find anybody that spoke English. Anyway from there, from the West Land, from there I went to the Chief Staff All Server on two where I stayed until I retired. Unfortunately I didn't make captain but I had a good life, a very good life.

Donald R. Lennon:

It sounds like it. And you retired...

Henry J. Conger:

I retired in 1961. I was looking for a job and I said well the best thing I know right now is physics so I applied for the, I heard that the Norfolk system had a recruiting. I called them up and they said fine we'll send you out papers for you to make up and then we will notify you whether you've been accepted. We'll I'd made out the papers and mailed them. I hadn't even, I had just put them in there and I got a call saying you've got the job!

Donald R. Lennon:

Before they even got the papers.

Henry J. Conger:

They had heard that I had taught at the Naval Academy and knew physics you might say. I ended up at Norview High School. I went back to- I went to Rutgers University one summer for to pick up some credits.

Donald R. Lennon:

Accreditation, yeah.

Henry J. Conger:

Then I went to William and Mary and got my masters degree in physics and mathematics. Then I ended up in William and Mary teaching the same coarse for three summers after I - because I- maybe they thought I did a good job or whatever. Anyway I taught three summers there. My primary job was Norview High School for twenty years and I ended up, after being there three years, I ended up as head of the science department in Norview for seventeen years. I retired, my salary with a master's degree, head of department, and a teacher was seventeen thousand dollars, in 1981. Can you imagine? That's what Norfolk was paying.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were paying low. That's lower than- I thought Virginia's salaries were higher than North Carolina's.

Henry J. Conger:

That was 1981 when I retired my ending salary was eighteen thousand dollars a year, eighteen thousand five hundred I think. Can you imagine that with a master's degree and also head of department. It's unbelievable that this day and time they start hiring them at thirty four thousand, thirty five thousand.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was quite a departure from teaching from being aboard ship as a naval officer wasn't it?

Henry J. Conger:

Yes but I had remembered my teaching there at the Naval Academy and I had no chart. I ran the physics section there at Norview High School just as if I was teaching it at the Naval Academy. Every person that I taught there, no I wouldn't say every person, but we put practically every one of them went to college. Over fifty percent of them got good scholarships. While I was there in that twenty years I helped get in about eight or ten to the Naval Academy and about the same number in West Point and the same number in the Air Force Academy. We had good students. In the ones taking the higher language courses and the higher mathematics courses and the science courses all went to college. All of them got good scholarships.

Donald R. Lennon:

There in Norfolk too, you probably had a lot of military children.

Henry J. Conger:

Yes right. I remember one time we had a transfer student from Norway and he couldn't speak English, but here he was taking physics. I said well do you, he could speak a little English, he said yes he. I said well, you've got the same pictures, same formulas, we will work with you with yours and we'll teach you. He stayed in Norview for three years and at the end of the time he was a top student. He took one English course after another so he could speak English. Also during that time I had a very good friend in Holland, Dutch

naval officer there, and he asked if his daughter could come over and stay with us. She stayed with us for six months. She came over as a student, but she says I'm not going to study too much. She spoke very good English. She didn't play around. Instead of going to classes during the day time she took night classes and she stayed with us for quite a while, there for six months and then she went back to Holland. We still correspond and I keep in touch with him. I made friends with him down in Carousal in 1952 that was when I met him. In fact he just lost his wife a couple of years ago and he's going to a retirement home now, but I still hear from his daughter too. She's married, she married a Dutch marine and they were on duty in Washington, DC and she came down a few times and things like that. We kept that friendship up since you might say for fifty years now.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any last mirrors of your naval career that we haven't covered?

Henry J. Conger:

Oh let's see about my naval career.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular instance or anecdote or sea stories?

Henry J. Conger:

Well one. When we were in, back in 1941 when we were in Iceland. We had just pulled in and, of coarse at that time our Admiral was supposed to go and call the British. They had some British ships in there and he would call on them. We had one young ensign who was in communications and I don't know how he got a boat, but he got in this boat and I don't know whether it was the Admiral's gig or what. He got over to this British ship and here was the whole ship lined up to greet the Admiral and here's this brand new ensign.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no.

Henry J. Conger:

Walks up the gangway. See in those days and times you didn't have rapid communications that you could, and here was our Admiral over there getting ready to go over and this ensign. Boy did he get called down you might say. A little bit of protocol, in those days protocol meant a lot.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looks like he would have known better.

Henry J. Conger:

Well he was brand new. He wasn't a Naval Academy graduate. He was a communications. He was just what we call one of the Ninety Day wonders that had been brought in. One other instance as it was, when we were in Adak we had just come back from ninety-six days of patrolling there. We were in Adack for a few days and I went ashore with a group of officers and we started playing cards, nothing else to do just had a little shack there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Try to keep warm.

Henry J. Conger:

Yeah, and you couldn't get a drink or you couldn't get anything unless you had a coupon. They only had ten-dollar booklets of coupons so each one us bought one and playing cards, poker and everything. I won all the coupons. O f coarse I got a little high. I didn't know what to do with all these coupons so I bought candy and I'd given out candy and everything to everybody. We go back down to the ship and all the officers knew that I'd had maybe a drink or too many and they said well here we'll go in and I said no the captain is there. The Captain called me and said, “Jack come on and go with me.” He had just picked up the new squadron commander, the Admiral, and here I am telling the Captain oh boy, woops again. The Admiral, he had a few little drinks too. The Admiral came up and we got to talking and sort of left the captain alone there. We get back to the ship, we were anchored out, and the Admiral insisted I walk up the gangway with him, instead of the captain.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know the captain was walking fast.

Henry J. Conger:

Oh by. I got to the head of the stairs. The officer of the deck saw what was happening. Here the Admiral had his arm around me and I had my arm around the Admiral. Here's the Captain, you could tell I didn't know all this, coming up behind us mad as the

devil I bet. The officer of the deck separated me from the Admiral and sent me to my quarters, had me escorted down to quarters. For about five or six days I didn't dare go by the Captains quarters.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he ever say anything to you about it?

Henry J. Conger:

Nope, never a word. He never made a comment at all, because I got to be very good friends with the Admiral. I think that didn't have anything to do with it he just took it as and instant, just something like that happens. We had another instant still on the TARAWA. Our gunnery officer was, there again we didn't have drinks on our ship but we anchored in Saint Charo there with a British cruiser. We went over there and we had lots of drinks and everything. This gunnery officer, Captain, and Commander Zink, he slid on the quarterdeck on the British ship and we had this latter going down to the water and everything. He stood there and just bang, just slid all the way down. That wasn't tragic or anything but he didn't get hurt. If he had been sober he might have been.

Donald R. Lennon:

Been embarrassed.

Henry J. Conger:

Little embarrassing is all. But there was one thing that all the foreign ships that we went aboard, most all of them was French ships that I went aboard, the Dutch ships, the English ships all of them served drinks. You never saw any of them drunk, never. I don't think I saw aboard ship a drunk officer on a foreign ship. They always served wine. If they wanted it they had other whiskeys in their rooms and all but we never had any. It is a contrast between our ships and theirs, quite a big one. Well I think I've talked about it up.

[End of Interview]