| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #138 | |

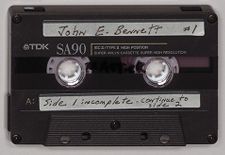

| Capt. John E. Bennett | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 5, 1994 | |

| Interview 1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, tell us a little bit about your early background, your childhood, your education before the Naval Academy, and what led you to the Naval Academy. I usually jot notes to myself as you're talking and I may interrupt you with a question about a particular aspect.

John E. Bennett:

I was born John Edward Bennett, April 9, 1918, in Montpelier, Ohio. I've been called Jack all my life. My father was a railroad man at the time and we soon moved to Riverside, Illinois. He and my mother were both from Peru, Indiana, and that was sort of the focus of my growing years--going there for vacations and so forth. My mother was one of four girls in her family, all of them beauties, and they drew a lot of friends and relatives there, so it was always a rather exciting place to go, growing up.

My dad had been an enlisted Marine. He did not reveal to me until after I graduated from the Naval Academy that his ambition was, if he had a son, for the son to go to the Naval Academy. He never mentioned it. So it was just by chance that after seeing the movie, Navy Blue and Gold, while a high school student, starring Dick Powell and Ruby

Keeler, the tap dancer, with some great songs--"Shipmates, Stand Together, Don't Give Up the Ship," and all that--that I was inspired to try and get in the Naval Academy. So, to that end, on my 17th birthday, April 9, 1935, I joined the Naval Reserves as a seaman second, actually seaman third, which rate no longer exists. It was absolutely the lowest you could get in the military services. We were living in Riverside, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, and I drilled every Tuesday night, marched around with a rifle down at the Naval Armory on the lake front at the foot of Randolph Street in Chicago.

I was then eligible to take a competitive exam for entrance into the Naval Academy. They took twenty-five out of the Naval Reserve each year and over five thousand took the exam that year. I stood twenty-eight. I should say that of the five thousand, most of them weren't prepared at all to take the exam. This was before the college boards. We had six subjects and we went down to the post office building in Chicago two days in a row to take exams in three subjects each day. I did very well; I got a 3.9 in math and in something else, physics, I guess it was. On the second day, I forgot my fountain pen and I had to use a post office pen, which had an old, old point and on almost every up-stroke, it blotted a whole series of blots on my English exam. I had to use asterisks and invent new symbols to show the word that had been blotted out; and it was the messiest paper you could imagine; but the content was there. It should have been--I knew that subject--almost a 4.0. I got a 2.6 in it; and after meeting the professors in the English Department at the Naval Academy, who graded it, I realized why they went more by neatness than by content. So, anyway, I stood twenty-eight and they only took twenty-five.

At the last minute my uncle, who was head coach of the Washington Redskins at the time, got an appointment for me from Senator Dieterich of Illinois, whose principal and all

three alternates had failed the exam, so he had a vacancy. I should have started out by saying that the reason I didn't have a chance to get a congressional appointment was that my parents were both active Republican volunteers, and everybody elected from Illinois was a Democrat. The whole population was swayed by F.D.R. and they fawned at his feet, so there wasn't a chance if you bore the Republican label. Anyway, I got the appointment through my own Senator Dieterich, and, of course, I had already passed the exams handily. More than three of those twenty-eight Naval Reservists failed the physical at the Naval Academy, so I would have made it through the Naval Reserve after all. Our class was the first to have our eyes refracted when we entered. It used to be you could just memorize the eye chart. By refracting our eyes, fewer passed than they expected and we had a very small class to enter. Strangely, some people failed the color-blind test and everybody had taken preliminary tests in the field. How in the world you could pass the color-blind test in the field and then fail it at the Naval Academy is beyond me, but some did.

When I entered June 15, 1937, as a plebe, we had our choice of four languages and I chose French, which was the international diplomatic language and that put me in the second battalion. The roommate assigned to me for plebe summer bilged out at the end of the summer--Edgar Allan Jack. Then I was able to get together with a classmate of mine from Bullis Prep, Ray Hastings. He was a great guy, all-state football player from New Hampshire, but his knee was injured plebe year and he got water on the knee and he missed classes because he was in a lot of pain. He bilged out plebe year.

Going through the Naval Academy . . . I guess I can just whisk through that. When we came back from First Class Cruise, the war in Europe had heated up. They decided to expand the Navy and so they cut our first class year in half, to four months. So all the

departments brought the professors back; and they revised the course and so forth, except the ordnance department which didn't bother with that. The duty professor, or whatever you'd call him, simply doubled the lessons. So on the first night, we had lessons one and two, the second night three and four, and so forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were covering the same material; it was just in double time.

John E. Bennett:

Exactly, so you know there wasn't a possibility of reading the entire two lessons during the study hour assigned, unless you stayed up all night and put a blanket over the lamp at the desk, and I didn't do that. Well, we quickly found that the questions were either to “sketch and describe something” or a bunch of individual questions, “the bull,” we called it. So you really had an automatic choice of either studying the sketches and drawing a slip that said “sketch and describe something,” or skipping that totally and reading the “bull.” The “sketch and describe” slips were narrow and the "bull" questions were on wider slips, all on the corner of the professor's desk. As you'd go into class, the slips would be there. I happened to be a section leader and I would report the section and he'd say, "Gentlemen, draw slips." I was up front and so I was able to take my choice. If I had studied “sketch and describe,” I'd pick a narrow slip.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you had the choice there, but only if you knew which size slip had which kinds of questions on it.

John E. Bennett:

That is right. If you were in the back row, you had to hope that one of the slips for whichever you had studied was left. Well, somebody spilled the beans. They caught onto it and they made all the slips the same size. I remember one time, I had studied “the bull” the night before and the slip I drew was a wide slip, but instead of having bull questions it was just one thing: “sketch and describe the Ford Range Keeper Mark 1, Mod. 1.” I had never

heard of a Ford Range Keeper. Does it keep ranges, why, what is it? And Ford, what's that got to do with the car? And I hadn't the vaguest idea what it was, because I had not looked at the sketches, I'd spent my allotted time on “the bull.” So, I went to the blackboard and spent half the time just writing my name, and then I drew a sketch of some Rube Goldberg thing just for fun because I had no idea what a Ford Range Keeper was, and I got a zero, naturally, for that day. We were graded everyday in every subject.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did the instructor say? Did he make any comments or was he accustomed to that?

John E. Bennett:

It was a naval officer and they barely knew the subject to begin with and they were more understanding. He probably got a kick out of it, but there was no disciplinary action taken against me.

Then we graduated early, on February 7, 1941. We had a preference of ships and you couldn't put in for submarines or aviation for two years, or get married, supposedly, for two years after graduation. So, I put in for heavy cruisers and my first choice was the HOUSTON, because she was out on China Station and I thought that would be exciting. My second choice was the SAN FRANCISCO, a heavy cruiser of a different class, with armored turrets instead of mounts for her eight-inch guns. She was of the newest heavy cruiser class. She was based at Pearl Harbor. Well, fortunately I got the SAN FRANCISCO instead of the HOUSTON, which was sunk within a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we leave the Naval Academy, what about any recollections of extra-curricular activities? What sports were you involved in?

John E. Bennett:

Well, I played football in high school and plebe year at the Naval Academy and then youngster . . . . I broke my collarbone senior year in high school, just before the

championship game. We won the Chicago West Suburban Football Conference and we were co-champs in basketball. To regress a moment, I went back for my only high school reunion, which was the fiftieth, and it was also the homecoming football game. The coach asked a couple of us to come down to the locker room before the game to inspire the football team. Well, I had found out by this time that we were the first RBHS class to win the Chicago West Suburban Conference and they had not won it since. So, we were the only ones that had ever won that thing. We got outside the locker room; the door was closed. We had watched their warm-ups and they had cheerleaders in the middle of the practice field, which used to be our game field, and they had a record player blasting some kind of acid rock. The cheerleaders were going through all sorts of gyrations, and the squad was in a big circle around them and they were lazily doing calisthenics. They weren't doing the right warm-up exercises in the first place. So then when my teammate and I got outside the locker room, we could hear music blaring forth from inside. It was the worst, the loudest music; it must have been acid rock. I'm not sure what that was, but it was even worse than what we had heard on that practice field during the warm-ups. And so I said, "Bob, what in the hell can we say to these people? They won't even know what we're talking about." So, we just turned and left. We didn't even go in there and they lost the game, of course.

So then, back to the Naval Academy. . . . At spring football practice youngster year I broke the same collarbone again and was advised by two doctors and two coaches to lay off contact sports. The doctors were the team doc and the orthopedist at the hospital; one coach was assistant football coach Keith Molesworth and the other was head basketball coach Johnny Wilson, who had his own motives. I was better in basketball then football as I was

pretty light for this level play and when football coach advises you to choose another sport, that's a message to listen to-so I quit football, my first love, and concentrated on the round ball where I quickly made the training table.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any scrapes, or particular episodes that you remember? I know that some of the class members have in the past had some stories of Uncle Beanie or things of that nature that were interesting asides.

John E. Bennett:

Uncle Beanie. You have all the stories on Uncle Beanie, I guess. We admired him. We tried to beat him and we never won. He was a good man. He wasn't like those people, somebody called the Woose, I think it was Wessell, who was gone before we got there (thank God), who was just plain mean with a five-cell flashlight and so forth. I stood next to anchor in conduct plebe year, and the reason was, I had a lot of fun, and I did things for laughs, and I'd get caught frequently.

Plebes couldn't go to the hop. It was an upper class event. White cap covers had just come back; we wore blue cap covers in the winter and white in the spring and fall. So, traditionally, when white cap covers came back, the youngsters would come back from a hop and they'd throw the plebes in the practice pool, the instruction pool. My plebe year after a hop, a guy burst into the room who was a first classman, Punchy Daunis. He was in his cups and he had his full dress on, and he was on the boxing team. I tried to explain to him that this was a youngster rate, not a first-class rate, and he wanted to put us in the shower instead of the pool, because he was too lazy to walk back to the pool with us, I guess. I don't know what possessed me, but while he was pushing me in the shower, I got him in instead. Here was Punchy Daunis, in the shower in his full dress, and he's a first classman. Ray Hastings, my roommate--he was a big guy--was yelling, "What the hell are

you doing Jack? My God!" So, here we were in this situation and I kept pushing him down when he'd try to get up. Finally, we let him up and slid him out the door and he was very slippery; that heavy full dress when it's soaking wet is just like it's covered with soap. He slid across the main corridor into the door across the hall, and almost broke the glass on that door. Then we had to hold our door shut, and there was no lock on it, just a little doorstopper. We would take turns, Ray and myself, with our foot on that door stopper and then holding the door knob while Punchy was trying to get in, and hollering threats and so forth. Then he'd be quiet for a while and then try to get in again. We took turns; we were up practically all night. Well, needless to say, I was a marked man.

Donald R. Lennon:

You aren't supposed to resist upperclassmen at all, are you?

John E. Bennett:

No. Why, he didn't go after Ray, I don't know; but I'm the guy that put him in the shower. First I'll tell you what he did to me, and then what I tried to do to him again in retribution. Every time he had the Midshipman Officer-of-the-Watch duty, he would find out where I was and he'd send his messenger over to put me on the report for “conduct unbecoming a midshipman,” “unseaman-like conduct,” “unmilitary conduct,” and the like.

Donald R. Lennon:

Whether you do anything or not, they'd just write you up.

John E. Bennett:

There was always something, like allowing section to make catcalls in ranks one time. I was a section leader marching my section along and I saw him off at a distance. And here came the messenger running and I figured "Oh-oh. Allowing section to make cat calls.” Well, he couldn't hear anything and what is a catcall anyway? “Unmilitary conduct third and fourth offense” and all this kind of stuff, and so I was marching extra duty. I think I was on a training table then for basketball. So, after that ended, then it was just extra duty with a rifle almost every night. So, Hundredth Night came up. The Hundredth Night before

graduation is when the plebes were able to turn the tables on the first class in the mess hall. Punchy was down in the fourth platoon. I went down there and went behind him and said “Brace up, Mr. Daunis,” and brought my hands down hard on his shoulders and he collapsed. He had been drinking and he was just out; he was practically out on his feet. So, we had to drag him into a nearby room and leave him in the room while everybody marched off to the mess hall, and so he escaped the whole thing. Well, I knew Punchy Daunis was going to have it in for me as long as both of us were in the Navy. When I reported to my first ship in Pearl Harbor, I knew he'd gone to a battleship out there. So when I got out there, I inquired about him and I found that he had absconded with the ship's service funds from this battleship and had been apprehended in San Francisco by Naval Intelligence. He had been given a general court martial, was convicted and was sent to Portsmouth Naval Prison, as a seaman second class.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, that got rid of him.

John E. Bennett:

Right. So, that took care of any fear I had from Punchy. That was the sum total of that incident and why I stood so low in conduct. I had a great time there and didn't really study very hard. I didn't stand very high. I was down in the fourth quarter of the class, but I really enjoyed it. Of course, I made friends in our small class that exists today.

Aboard my first ship, the SAN FRANCISCO, we were operating out of Pearl. I was in the anti-aircraft division. Two of us from '41 reported aboard. Dick Marquardt was the other, and we were roommates. He was in the fourth division, I was in the fifth. I was assistant division officer, then they divided that into 5 and 5-A; 5-A being the automatic weapons when we got 1.1 mounts, and I became the division officer of 5-A. So, we were there on December seventh of '41 when the Japs struck. We had just entered the Navy yard.

We were alongside the dock. We were supposed to go on dry dock as soon as the PENNSYLVANIA came out, so in anticipation of that, we had off-loaded our ammunition. Well, the PENNSYLVANIA was delayed getting out; so when the Japs hit, Sunday morning, the seventh, we had no ammo. I was in my bunk; I had been out on a date in Honolulu until about three o'clock in the morning actually. I woke up because of an explosion. I jumped out of my bunk and ran to the port--we had portholes then--and I looked out and here was a Jap Val dive bomber with fixed landing gear and a big meatball just strafing the dock. He picked off a sailor on the dock, so I turned to my roommate and said, "This is it," as if I'd been expecting a problem with Japan, or anybody! I didn't at all. I was just vaguely aware of the negotiations going on and all the problems because I was just having a ball. It was a total surprise.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, at your level, there was not the information that they had at the higher command levels.

John E. Bennett:

That is right. I shared not one, but two apartments on the beach, “snake ranches,” we called them. One was in Waikiki. It was a converted garage on Ohua Street and four of us JO's paid forty dollars; ten dollars each, a month for that thing. It was equipped with cots and a pull down bunk and a kitchen. Everybody had an old heap or shared an old car with somebody else, and it was just very enjoyable living. It wasn't too crowded out there at all and the double hibiscus and the climate are still that great today, but the rest of the environment, of course, is totally changed for the worse.

So, back to December seventh. Since we had no ammo, I ran across the dock to the NEW ORLEANS, a sister ship, which was also starting her yard period. Both of her anti-aircraft directors were in the shop, so her anti-aircraft 5-inch twenty-fives were in local

control. I took over number seven, which was the last one on the starboard side. I got there about the time the gun crew showed up, and it was mostly NEW ORLEAN's men. Now my own division was pouring aboard and they were milling about on the well deck. I looked at the flag and the stack gasses and so forth, to see where the wind was, and I set the deflection properly--estimated that is--on this gun and then started shooting at the Japs who were, at this point, making a horizontal run.

I was shooting at the Japs making a horizontal run over Battleship Row. It was impossible to spot my burst among all the other bursts in the sky and so really, in effect, we were just putting up a barrage fire hoping somebody would fly into it. At one point, I was aware that the gun did not fire. I had the gun captain try to fire it electrically and mechanically, by hand, from the different ways--pulling the toggle, using the finger key and the foot pedal key. For four years at the Naval Academy, we'd been taught if the gun does not fire, to consider it a hang fire, wait thirty minutes, then consider it a misfire, and open the breach.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have thirty minutes to spare.

John E. Bennett:

All of a sudden, you know here I am, a red-tailed ensign, and it's obvious to me that this rule is ridiculous; it doesn't apply to this situation. So I cleared the gun tub and had the gun captain open the breach, and the shell did in fact eject into my arms, and I threw it over the side. It was a dud. It was indeed a misfire; obviously not a hang fire, or I wouldn't be here to tell you this. Then we fired some more. Then I became aware that we'd had another misfire, and he didn't even bother to ask me. He just opened the breach and tossed another one over the side. So, alongside the dock there, in addition to whiskey bottles and sailors'

wallets and all that, down in the silt, there is some unexploded ammunition that is just sinking deeper and deeper into the Earth.

The NEW ORLEANS tried to get underway and they cut shore power and we lost power to the electric hoists. I looked down on the well deck and here was Shorty Tailor(?), gunner's mate in my division. So I said, "Shorty, take the men around you, start an ammunition party bringing the ammunition up from the forward 5-inch magazine, through the crew's mess hall, through the well deck, and up this ladder to this battery."

I am sure NEW ORLEANS officers or somebody must have been saying the same thing, because it was the obvious thing to do. Anyway, they did it. Pretty soon the ammo was coming up. The NEW ORLEANS had a chaplain named Forgy. He was a big, former football tackle. Forgy observed this and uttered the phrase, "Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition." I thought he composed the song, too, but it turns out he didn't. But it was his phrase, "Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition," that was so catching you know, that Kay Kyser made the recording of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, OK, so that was original with him.

John E. Bennett:

“Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition”--that's where it came from.

Donald R. Lennon:

Really, OK.

John E. Bennett:

It was one of the best songs that came out of the war. Thank God, I didn't hear some of the songs, because I was at sea almost the entire period. There was one called, "Slap the Jap Cause He's a Sap," and there was another, "Hitler's a Piddler and He'll Play Second Fiddler." Can you imagine people actually composing and singing things like that? Then there were some other great songs of World War II that I did hear.

I found out much later why the NEW ORLEANS never restored power to the electric hoists. When they told this electrician's mate to cut shore power, he cut it literally with an axe. He cut the cable with an axe, so they could never reconnect. The ship failed to get underway. I don't know why. I mean they were trying to light off the boilers and all that, but we remained alongside.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was the NEW ORLEANS or the SAN FRANCISCO hit?

John E. Bennett:

Well, the NEW ORLEANS got some shrapnel through a stack. In fact, I got a little thing on my thumb. I was just raising my hand to my World War I tin hat. The strap was broken and every time I'd turn my head, it would wiggle around. I was just raising my hand, and this piece of white hot metal started bouncing around in the gun tub, and at first it just nicked my thumb. It could easily have gone through the palm of my hand. It could have gone through my nose, or anything, so it was just by chance that while I was raising my hand, it did that. I watched this thing bounce around and turn from white to red and then, you know, I forgot about it. I didn't pick it up any place. I don't remember dressing this. I know I didn't use a first-aid kit and Band-Aids weren't invented yet. So, I don't know what I did--maybe a handkerchief�and, of course, I didn't even report it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You probably ignored it.

John E. Bennett:

Probably. I'd get blood on me here and there from it. I probably washed it off when I got back to my own ship; maybe put a handkerchief around it. Kleenex wasn't invented either, or sliced bread, or ballpoint pens; all those wonderful things that are so necessary that we take for granted. That night in the wardroom of the SAN FRANCISCO, I remember turning my head from right to left, when the voice of the fellow across the table to my left suddenly cut in. I had not heard him and he had been asking me to pass the sandwiches, and

I hadn't heard him. It was just like I had a blind spot in my ear, which is understandable with the eye, you know you could have a finite barrier where you cannot see. But how is it possible with an ear? I turned my head back and forth and his voice would cut in and out. I had had all these 5-inch twenty-five guns with the starboard battery of the NEW ORLEANS, the loudest guns in the Navy, and the sharpest crack, all going off to my immediate left, and I didn't have any cotton in my ears and that must have been it. I got over that, except every annual physical I had, practically my whole naval career, the doctor would say, "Do you ever have any trouble with this ear?"

I'd always say “no,” because I wanted to pass the physical. Finally on my retirement physical, I asked the doc, "What's the matter with my left ear? They're always asking this question."And he said, "Well, it's inflamed, you must have an infection or something."

Donald R. Lennon:

You mean it stayed inflamed your entire career?

John E. Bennett:

I don't know, but that is what the guy said. Now, due to advancing old age and so forth, I have lost the higher frequencies, which is normal, but I've lost more than normal, just in hearing. I find myself, when somebody's talking, turning my head so I can hear. I hear better out of the right ear than the left. That's just a little minor thing.

I had another injury off Guadalcanal, as long as we're talking about wounds. Of course, I never even reported this thing. Jumping ahead, I'll quickly say the SAN FRANCISCO got underway as soon as we could--about a week after December seventh. We joined the LEXINGTON and the tanker NEOSHO and another cruiser and about four destroyers. The LEX was carrying aircraft, fighter planes, and F-2A Brewster Buffaloes (the pilots hated them) to the Marines at Wake Island. We would cross the international date

line and then there would be a report of a Jap carrier off Wake Island and we'd turn back and we'd go back and forth across the international date line. We never knew what day it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Didn't you want to engage the Japanese carrier?

John E. Bennett:

No, I guess not. Well, all of them from the attack on Pearl Harbor were reported there! Four carriers.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the United States couldn't muster up enough of a force to . . ..

John E. Bennett:

We only had the one carrier that could get underway at that point. The ENTERPRISE had returned, but she probably was being readied up to go out on other ops and the LEXINGTON . . .. Well, now, where was the SARATOGA? I think she was back in the States, I'm not sure. But the LEX was the only carrier in our group that went out to ferry these aircraft.

I don't have a definitive answer to the situation at that point, but the fact is that we kept going back and forth across the international date line, and the supply officer, Count DeKay composed words to the tune of Jingle Bells. I wish I could recall right now, but the essence was, "We never know the date. We never know the time, crossing back and forth across the international line." We had a lot of little limericks about it

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you never made it to Wake at all and of course, as a result, the United States sacrificed Wake, instead of trying to rescue the forces that were there.

John E. Bennett:

That is right. We never launched that air group of F-2A Brewster Buffaloes to fly in. They were afraid, I guess, that they would lose the LEXINGTON and we had very few to begin with and we had lost all the battleships, so that must have been the decision. Of

course, everyone wanted to go directly to Japan, you know, instantly, for revenge. We probably all would have been sunk.

Then we joined the YORKTOWN or the LEX, down to the South Pacific for raids on the Marshalls and the Gilberts and then whatever carrier it was went back, and we switched to the other one; so we were out seventy-seven days. Well, I had always wanted to be a fighter pilot, and coming back in, we had a message that said the classes of such and such, such and such, and nineteen forty-one are eligible for flight training. You were supposed to wait two years. So, I went over to Ford Island the next day, when we got in, to take a flight physical and I scored very high on the Snyder test. I had a hangover. I had gone ashore, of course, the night we got in and went to the club. Then I took the spinning chair test; ten turns in each direction and you're supposed to sit upright. Well, the deck seemed to be coming up at me, so I would reach out to hold the deck down and I'd fail that for the corpsman. Then the chief would have me do it; another ten each direction.

Donald R. Lennon:

The alcohol didn't help, did it?

John E. Bennett:

I was doing it worse each time and then I did it for the warrant officer. Now there were thirty turns, sixty turns altogether, and he said, "How do you feel?"

And I said, "About one more turn, I think I'm gonna lose it." I was just getting sick to my stomach, and so they didn't. They quit and sent me in to see Doctor Dickinson, who used to be at Misery Hall at the Naval Academy, where he took care of athletes in season. He said, "Well, Bennett, you know you didn't really pass this part of the test, but I'm going to go ahead and pass you.” “But,” he said, “you've got to think of the guy in the rear seat behind you."

And I said, "There isn't any seat behind me. I'm in a fighter plane."

He said, "Maybe." Then he was filling things out and he said, "Weren't you in the Class of forty-one?"

I said, "Yes, sir."

He said, as he threw his pen down, "Hell, you're not even eligible." The dispatch was garbled and it should have said 1940. It probably was '38, '39, and '40. I wasn't even eligible, so I obviously didn't go to flight training.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had spun around in that chair for nothing.

John E. Bennett:

That's right. So, I went back to the ship and on the boat going back across Pearl Harbor, I almost got seasick. So, then I stayed aboard the SAN FRANCISCO and we went on down to the South Pacific and we were with the Marines in the initial landings at Guadalcanal. This was after more raids here and there on different islands, and we were in the support group for the Marines. We lost two due to accidents; two of our four SOCs, scout observation float planes, biplanes. Rather than sending two from the QUINCY or VINCENNES, one of the two that were with the WASP, twenty miles south of Guadalcanal, they interchanged the two ships. So we were with the WASP, and either the QUINCY or the VINCENNES were in the group that was patrolling at night after the Marines had landed in Guadalcanal. So it was the QUINCY, VINCENNES, ASTORIA and CHICAGO and the Australian cruiser CANBERRA and some destroyers. The U.S. forces had radar, but most of it was very rudimentary: bed springs, early warning, airborne. The Japs didn't have any. Well, that was August ninth approximately, 1942, and the Japs came down the slot and they surprised the exhausted Americans who were not at General Quarters and they went through the destroyer screen. There was one destroyer patrolling in the area that they came through, undetected. They had terrific torpedoes, Long, Lance, oxygen-driven torpedoes. The

American torpedoes--destroyer-fired, airborne launch and submarine torpedoes--were all terrible through the first half of the war; just an absolute disgrace. They would bounce off the sides of ships or run deep under them. The Japs had great torpedoes. They got a lot of hits and sank the QUINCY, VINCENNES, and ASTORIA, and the CHICAGO was badly damaged and they sank the CANBERRA. It was a major disaster and the SAN FRANCISCO would have fared no better if we'd been there. What we learned from that incident, tragically, was first of all, stay alert all night, stay at “General Quarters” all night in the Solomons and from then on we were at “General Quarters” all night, every night.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, did you all go in to try to pick up survivors?

John E. Bennett:

No. That was impossible to do. There were some survivors, and the Marines sent Higgins boats out to pick them up and there were still transports in the loading area off Lunga Point. The Marines landed in the eastern half of Guadalcanal. I remember when we were first approaching Guadalcanal, from Auckland, New Zealand, we didn't know what was up. There was a meeting in the wardroom, and the captain, Sock McMorris, came down. A chart had been put there, and he pulled the chart down and here was a map of Guadalcanal. He said, "Gentlemen, this is Guadal-can-al," and we called it “Guadal-Can-al” until we got ashore some place and found everybody else was calling it Guadalcanal.

So, we learned the two things from losing the QUINCY, VINCENNES, ASTORIA, and CANBERRA. One was, you had to be alert, and so we were at “General Quarters” all night, every night, and the other thing was chip paint, because there were all kinds of fires ranging on those ships. During our waking hours, we were chipping paint for the rest of the war.

At “General Quarters,” you couldn't have one officer of the deck all night, so Bruce McCandless and I alternated every two hours. I was a good officer of the deck and I guess they recognized that, so I was on two hours, off two hours, as officer of the deck all night. Rather than waste time during my two hours off by going all the way down to my bunk and back up to the nav bridge, I dragged a mattress up and put it on the deck of the radio direction finder shack at the after end of the bridge. I'll get back to the significance of that in a minute.

On the matter of chipping paint, I recalled the sailors commented on how many layers of paint that they were chipping off. Ever since the ship had been commissioned, they had just painted and painted and painted. Before the war started, at Pearl Harbor, I was officer of the deck in port and a PBY-5A took off from Ford Island with wheels and didn't gain altitude and crashed in the Aiea area, some place between the water's edge and Kamehameha highway. I called away the fire and rescue party and called away number three motor launch, which was the shallowest draft motor launch. As the people were going over the side, down the accommodation ladder into the boat, I took the life ring on the quarter deck, that was hanging on the bulkhead, and I tossed that to a sailor who was just standing there ready to go over, and he missed it. It went over the side and it sank. There were so many layers of paint on it that it wouldn't even float. It was a life preserver and it sank. I thought of that, how much paint there was on that ship and its appurtenances.

Donald R. Lennon:

During peacetime the only interest is keeping them spic-and-span and looking sharp.

John E. Bennett:

That is right. And of course the peacetime procedure of considering that if the gun doesn't fire, it is a misfire or a hang fire, and wait thirty minutes. So we learned a lot, very fast.

We had a number of false actions, where people were seeing periscopes all the time that didn't exist. Later in submarines, I discovered how easy it was to make an approach on a surface ship; that we really had the advantage--the submarine did. In those days, with the crude sonar equipment and tactics being used--well, strategy, too, because our task force was going in a square, in a box, south of Guadalcanal when the WASP was sunk . . . I was looking right at her when she was hit by a torpedo--two torpedoes--and she sank.

Donald R. Lennon:

In a very quick time too, wasn't it?

John E. Bennett:

Yes, and it was after that I think--we had lost three or four carriers--that Halsey relieved Ghormley as COMSOPAC. They wanted more aggressive action taken by the commander of the South Pacific Forces. Halsey came out to relieve Ghormley, who was a fine guy. I don't know what orders Ghormley had, and maybe his orders limited him to being cautious, but having the task force going in this one little box was just an invitation, waving a red flag to Japanese submarines, “They're right here, and just get on the track and if you can't catch them the first time, they'll be around again,” and sure enough . . ..

Donald R. Lennon:

How did it feel the first time you saw a sister ship be hit and sunk like that?

John E. Bennett:

Well, having seen the battleships sink at Pearl Harbor, I already had . . ..

Donald R. Lennon:

You had already kind of hardened to it?

John E. Bennett:

The worst of that, at Pearl Harbor, was the ARIZONA blowing up when a converted projectile, being used as a bomb, went right through and hit her forward magazine. That might have been the most spectacular, but the most awe-inspiring was the OKLAHOMA

capsizing and rolling over, with sailors climbing over the rail and then down over the bilge keel and so forth, until she was almost bottoms up.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, by the time you got out to the South Pacific, you'd seen enough that it was . . . .

John E. Bennett:

Yeah, we'd seen a few ships hit, and of course the WASP sink. We were about two thousand yards; I guess, from her, twenty-five hundred. My recollection of the OKLAHOMA slowly capsizing was vivid during the Battle of Cape Esperance on October 11, 1942. The SAN FRANCISCO, BOISE, SALT LAKE CITY, and the HELENA, and four destroyers in the “van” and four destroyers astern. We had the destroyers in a battle line instead of on a screen, primarily, I believe, to more easily navigate the channels, Sealark Channel and whatever that other one was, between Guadalcanal and Tulagi. We were off Savo Island and all of the night battles in the Guadalcanal area originally were called the first, second, third, and fourth battles of Savo Island. Then they changed it, so the first battle of Savo Island was when the QUINCY, VINCENNES, and ASTORIA were sunk and the second battle of Savo Island was this October 11th, which later became the Battle of Cape Esperance. Norman Scott was the admiral on board; Sock McMorris was our skipper. Scott tried to cross the T. We had radar. The HELENA had the best radar. We picked up the Japs. I was a catapult officer also and I had launched an SOC. It was already dark. Tommy Thomas was the pilot and senior aviator out of '37. He radioed back reporting another force--another Jap force--and apparently nobody believed him. It turns out there was another force. We had this Jap column coming down this way towards the southeast, I believe. To cross the T more properly, Scott ordered a column left, almost a complete reversal of course, almost a 180 with the SAN FRANCISCO as the guide. So on execute, we made the turn to port. That meant the four destroyers up ahead of us had to pass up our

starboard side to get ahead again. Well, we commenced firing at the Japs before they had all cleared, in fact, the fourth one, the DUNCAN, had veered off to her starboard to launch a torpedo attack. We opened fire at the lead ship, the AOBA, a Jap cruiser. A Jap admiral was aboard and was killed. Admiral Scott said, "Do not, repeat, not, illuminate by search light." The word barely died out before the BOISE, astern of us, illuminated by searchlight. Not only that, she illuminated our target, the first ship. So, we are shooting at the AOBA; the BOISE is illuminating her; and I watch her turn turtle, to port with her guns trained centerline.

So the SAN FRANCISCO was being straddled by the Japs. It was not the AOBA, because her turrets were center-lined, but somebody was straddling us. We had two salvos that we knew about--one short and one over--meaning they had the range. When the BOISE illuminated, they walked their point-of-aim back to the BOISE and hit her. We received only minor damage from near-misses sometime during that engagement, but the BOISE really got it. Her forward magazine blew up and she was on fire--the forward part of the ship--and she veered out to port, and the SALT LAKE CITY closed up, and the HELENA closed up. The BOISE was out of the action then. In the meantime, the DUNCAN . . . .

Oh, I am on automatic weapons aft. I am on the boat deck out in the open. I had a view of all of this, unobstructed. We had a contact nine hundred yards on our starboard beam. I was hearing this over my circuit, my headset. They thought it might be the DUNCAN, the fourth destroyer that had been ahead of us and was supposedly coming up on our starboard side to get ahead again after we'd made that reversal of course. But that ship, that contact, was showing fighting (recognition) lights. We had fighting lights--red, green, and white--in different combinations in a vertical line, probably twenty feet apart. They had

different colors (red, blue, white) and also there was somebody apparently on the port wing of the bridge flashing a white light down into the water in code--very rapid flashes, I could see. So, we trained the main battery and the secondary battery on her, and illuminated with a thirty-six-inch searchlight and there were two white stripes around the stack. It was Jap. So we opened fire. We were already trained on her. The first salvo from the main battery at nine hundred yards, unbelievably, was short; big splashes went up, and the destroyer turned and made knots. You could see the smoke pouring out. The second salvo made a flush decker out of her and the third one just blew her up completely. That was the FUBUKI, it turns out; the Japanese destroyer FUBUKI was the leader of the class of new destroyers. She probably was looking for this other Jap force that had been reported by our airplane that nobody believed, and this is why she was closing us that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

And also signaling.

John E. Bennett:

Yeah. I didn't know it at the time, but I had just gotten revenge for an Aussi that I picked up later in submarines. He was on the HMAS PERTH that was sunk along with the HOUSTON in the Java Sea, actually Sunda Strait, earlier in the war when the war just started. The FUBUKI caused much of the damage with the torpedoes to the HOUSTON and the PERTH; and now we had just sank the FUBUKI. When I rescued Arthur Bancroft later, which is a story I'll tell later when I'm in submarines, I was able to tell him that we had already gotten revenge for him. So, that was the battle of Cape Esperance and it was a brilliant tactical maneuver by Norman Scott, who successfully did cross the T. “Crossing the T” was invented by Nelson at Trafalgar, and there is no need to explain what that is. He did it; it was not exactly a ninety track. It was more like a sixty-five, I'd say, but it had the same effect. And we won that battle.

Then November 12th, the next month, we were up there again, meeting the Tokyo Express that had been coming down the slot with high speed transports landing reinforcements at the west end of Guadalcanal. The Marines just barely had a toehold, and they were getting air attacks. They were down to half a dozen drums of avgas and the situation was in extremis for them. The Japs were making a major effort to re-take Guadalcanal and if they'd done that, they would have gone on, ultimately, to Australia. So strategically, it was vital that we hang on. Therefore, when the good old Aussie coast watchers reported an air attack; that there were so many Mitsubishi type ninety-nine or later type o-one, land based bombers, Bettys, we knew their altitude and we knew what their cruising speed was. We knew when they would arrive and on the afternoon of the twelfth, half an hour before they were expected, we went to air defense stations. Mine was aft, on the boat deck with a headset on, automatic weapons aft. These twenty-two, as I remember, airplanes fanned out and went down to just above the deck. They had been converted to carry torpedoes, and they launched a torpedo attack. Well, these were Army pilots and they weren't properly trained and the torpedoes would tumble. Our force shot down all but one of them, and nobody was damaged except one of those that was already in flames; not the one that got away. Before the kamikaze corps had been invented, this pilot banked over and deliberately attacked us. First he launched his torpedo, then he went up our starboard side and crashed into our after superstructure on purpose. Well, that wiped out all my gun crews on there and on the machine gun platform. We had twenty millimeters there. It burned up the people in Battle Two and in ship control aft, including the exec. They weren't all burned up, but they were badly burned.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now this was the first time the SAN FRANCISCO had been hit, wasn't it?

John E. Bennett:

Right, except at Pearl Harbor, where we found some little holes in the stack and so forth, but there wasn't really damage. This killed about twenty or some sailors, and that evening we off-loaded them to one of the transports that had medical facilities. The exec, Mark Crouter, refused to leave the ship, and so he was in his stateroom--in his cabin--because he knew that there were battleships in the Tokyo Express coming down the slot that night. That is what I alluded to earlier, that it was suicide for us to stay there--cruisers and destroyers. But, we absolutely had to do everything we could to prevent them from bombarding Henderson Field. And we stopped them, at great sacrifice.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, you had the loss of firepower on the SAN FRANCISCO as a result . . . .

John E. Bennett:

We lost ship control aft. Turret three was in local control. The two five-inch batteries could be controlled from sky forward, but only one at a time. As it turns out, that night we were firing on both sides simultaneously.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you were still able to raise enough firepower to be effective, even with the damage.

John E. Bennett:

The officers we had lost in control stations were the most important. The wing tip came off that airplane and went through the air and hit my wing tip, hit my elbow. I had just gotten a report of dive-bombers. I was looking up with my binoculars, my elbows spread, looking for dive bombers coming out of the edge of a cloud, when a Betty came up the starboard quarter and crashed into us and a wing tip came off and it hit my elbow and spun me around. I didn't know what it was. Then, of course, all of his avgas exploded and it was just an inferno back there, just astern of me about twenty, thirty feet. Almost everybody there was in my division. We were still at air defense stations and the air battle was not over. The Marine fighters had taken off from Guadalcanal. The attacking airplanes

had split into two groups; one went directly over Henderson Field and they were intercepted by the F-4Fs . There were no F-4Us there at this point. The other group--the twenty-two carrying torpedoes--were the ones that attacked us. Also, there were some Zeros with them, and they were all engaged by the Marines. So that was all going on. There was still air action, and I think they shot down everybody.

Donald R. Lennon:

How difficult was it to get the fire out?

John E. Bennett:

Oh, not too difficult.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was going on simultaneously with everything. It just burned itself out?

John E. Bennett:

That's all that happened. The avgas just burned up. That is what gave me a little piece of metal fuselage.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was your purple heart from the wound on your elbow?

John E. Bennett:

Yeah, but I didn't get it then. I will go ahead and tell you how I happened to get it. I was, in fact, wounded and I wondered if my phone would stretch over to the first aid kit on the rail. With one hand, I got something out of there and put it on my elbow. It was bleeding a lot, but Mother Nature takes care of it when you have something more important going on; I don't remember the pain at all, that was minor. But I had to stop that blood, so I did that and somebody is hollering down from sky aft for me to “Go to sick bay, go to sick bay.” Joe Tucker, a reserve lieutenant, was doing that, but we were still fighting. He kept on hollerin' down. Finally I told him, "Damn it, Joe, shut up!" So, when we secured from air defense stations, then I went down to sick bay. They x-rayed it and they properly dressed it and so forth, and I went back up since it was time to stand my regular officer-of-the-deck watch. I did, two hours, first dog watch. I stood the officer-of-the-deck watch with my arm in a sling. No problem. I held my binoculars with one hand. I overheard the

captain and the admiral on the wing of the bridge--the wind had carried their voices--talking about how there were battleships in the Tokyo Express coming down the slot that night and that it was suicidal for us to be there, but of course, we had to be there. So, I was privy to this information. There were six people that knew that.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have any battleships in your group at all.

John E. Bennett:

Oh no, just the two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, two anti-aircraft light cruisers, and eight destroyers.

Bruce McCandless held gunnery school exactly one year earlier. It was November the thirteenth, nineteen forty-one. I still have his notes, the lesson plan: SAN FRANCISCO v. MOGAMI class cruiser. It touches on such questions as the best range for us, the best range for them, where their shells would least penetrate our armor and ours would best penetrate theirs. It turned out that we should seek a range of eighteen thousand five hundred yards, let's say. Regarding battleships, it says, "Not a likely encounter, but mentioned here just to show the disparity of fighting strength."

One year later, to the day, we were against Jap battleships, and Bruce McCandless who held this school and signed this lesson plan was key in getting our ship through it. He and I alternated as officer-of-the-deck and he had the deck then. It always started with him. When I stood my first dogwatch as officer of the deck, we had not gone to battle stations. Then we went to battle stations and he relieved me. Then I would have two hours off and then I would relieve him. So, I went in the chart house for a cup of coffee and a cigarette before going back to the radio direction finder shack in the after end of the bridge to lie down on that mattress for two hours.

When I went in the chart house, Admiral Dan Callaghan, who had been skipper before the war, had just come aboard as admiral. I had been player coach of the basketball team and we were tied for first place in the Hawaiian detachment of the U.S. Fleet, which became the Pacific Fleet. We were tied with the WEST VIRGINIA, which always got the Iron Man Trophy because they controlled the Bureau of Navigation, which was the Bureau of Personnel later and all the athletes got siphoned out to the battleship WEST VIRGINIA. So, anyway, we were lucky to have done so well and our number one fan was Dan Callaghan and sometimes he was the only spectator. I remember playing in Aiea High School gym against the INDIANAPOLIS, and there was one spectator there. It was Dan Callaghan, our skipper. I knew Mike Hanley, who was playing for the INDIANAPOLIS and I was giving him hell, you know, "Where's your skipper, Mike? There's mine." There was one damn spectator, plus a couple of kids that drifted in. They beat us anyway. One of our few losses.We also lost to Oahu Prison. It was a home game for them and the officials and the scorekeeper and so forth were all convicts. I had just made two baskets and there was no change in the score since before, so I took myself out to complain about that. Then I had to put a substitute right behind the official scorekeeper, who was a convict, probably for embezzlement, to see that he recorded our points. So, we lost to them and we lost to the Hickam Field all-stars.

But, back to this night. Dan Callaghan saw me come into the chart house and he recognized me. He said, "Well, hello there, Bennett. Good to see you." He put his hand out and I walked over to shake his hand. Cassin Young, our new skipper, was standing there. He had already received the medal of honor from Pearl Harbor. He had been skipper

of the VESTAL and had been blown off and swam back to his ship through burning oil and climbed back aboard and took over a three-inch gun and got the medal of honor. Cassin Young turned and saw me and my arm was in a sling and it was bleeding through the bandage and it was bleeding through the sling. I didn't know that, but there was a growing dark spot at the elbow. He said, "You're in no condition to stand a watch. Go below."

I said, "Captain, I just stood a watch. No problem at all. It doesn't hurt." And I don't think it did; or if it did, it was just very minor. Since I knew we were against battleships that night, there was no way I wanted to be down in my bunk or in sick bay. Thank God it wasn't sick bay, because they were wiped out by a fourteen-inch shell a couple hours later. He insisted that I go below and he had McCandless get a replacement for me, who was Stan Kerkering, an aviator out of thirty-nine, who had qualified as officer of the deck on a carrier. Poor old Stan got up there and he was rather severely wounded that night. And of course, McCandless was, too. I went below and I took one lap around the ward room table and went back up to the gun boss, Willy Wilbourne.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't even have them check your elbow to try to stop the bleeding or anything to see how bad it was?

John E. Bennett:

No, I think it had just dribbled through. No problem, compared to what was going on. But the captain didn't tell me to STAY below, he just told me to GO below. I mean, that was very important; I carried out his orders, and I went below. Now what do I do? Well, we're going to be shooting battleships pretty soon. So, I went back up to the gun boss and asked for a new battle station and I said I had been relieved as officer-of-the-deck and of course, I had. I didn't give him the details that the captain told me to go below. He sent me back to the fantail to take over automatic weapons aft in local control, since the AA

director had been wiped out by the plane crash. So, that is where I was that night, and we only had 30 percent casualties there. We had 98 percent on the bridge. So, the fact that Callaghan recognized me which caused the skipper to turn around, and the fact that I'd been slightly wounded that afternoon, and the fact that the sling was bloody--all that is what saved my life!

It saved my life, because if I had either been on watch instead of McCandless or if I had been lying in that mattress on the RDF shack, it would have been curtains. I looked at the RDF shack later and a six-inch shell had detonated in there, and it had blown out or puffed out all the four bulkheads. It looked like Swiss cheese; there were holes every place in the mattress, all kinds of holes, I mean, with shrapnel in them. So I would have been just decimated there. So, I was on the fantail and on my gunnery circuit, I didn't get all of the information. We also had communication problems; things that had been shot up and lost. I knew we had contact, and I didn't know what we were doing.

It turns out, we were trying to cross the T and messed it up and wound up going between Jap columns. They were coming down in four groups. We only knew three of them then: the center group and then two more. Both battleships were in this group, and there was a possibility there was a third battleship in another group, because we cannot explain how a fourteen-inch shell hit us at a certain location coming in from the starboard bow. It went through an eye beam, hit number two turret barbette, and split all four seams. It was a dud. The base plug lit at the foot of the armory, the doorway of the armory, at the feet of gunner Swede Hansen. There was all this noise and he looked down and here was the base plug of a fourteen-inch shell that had come to rest at his feet. In the meantime, part of it, as it broke up, went through the flood control panel of turret two and started flooding

the magazine and the lower handling room. The people in turret two thought the ship was sinking, and they started abandoning the turret and coming out the top through the overhang hatch and they were being killed as they came out in the open.

Donald R. Lennon:

What time of night was this?

John E. Bennett:

About one o'clock in the morning. It was Friday the thirteenth by this time. The afternoon of the twelfth was this air attack. So, then that night, we had thirteen ships in formation. It was Friday the thirteenth. One of the destroyer's hull numbers added up to thirteen and it was Task Force 67, which added to thirteen. That was all sorts of supposed bad luck.

I was facing aft; I was looking off to the port quarter, when a Jap ship coming down our port side illuminated the HELENA, which was just coming to a point to make a turn to follow us. Everybody was confused because the ATLANTA had gotten out of position and the destroyers--the CUSHING--were already running into the Japs and were trying to avoid collision with them. Our radar was this early warning bed springs, and the only other radar was on top of turret two and turret three. That was fire control and it would go out on the first salvo every time. The HELENA had good radar, comparatively speaking, and she picked the force up at twenty-eight thousand yards. The flag actually should have been aboard the HELENA, but we had better flag quarters, and also Callaghan had been skipper once on the SAN FRANCISCO. There were a lot of mistakes made, and we learned the hard way about communications: jamming the circuits, everybody talking at once, while they were trying to get the word out. We saw the ATLANTA veer off and I watched her coming down in the Jap battle line. You could see the turrets were stepped up. She had eight twin five-inch, thirty-eight gun mounts; three forward, three aft and one on each quarter.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did she realize where she was?

John E. Bennett:

Well, she had a rudder casualty. She also took a torpedo and she was coming down. The first thing I figured was, “My God they've got AA cruisers, too.” She was silhouetted. She was hit from both sides and their gunnery officer Pat MacEntee came aboard us later as a survivor. He was our anti-aircraft defense officer and I stood watches with him at night up in the Aleutians. He told about how they found green dye on their starboard side, the U.S. side, and we used green dye in our main battery. See in gunnery practice you had different color dyes, so that you could tell which were your shells, and ours was green. So, I'm sure we hit the ATLANTA.

I was looking at the HELENA when it was illuminated by a Jap ship. The HELENA had her fifteen six-inch guns trained out. She had five triple turrets, and fast-firing--accurately firing in her case--six-inch guns. She was trained on this ship. First you saw the HELENA fully illuminated and a salvo from fifteen-inch guns and the light went out and there was a big explosion. Just by chance, she sank the ship that had illuminated her. The people were firing star shells. We had three out of four that were duds during my time aboard the SAN FRANCISCO. First you would fire the star shells to illuminate the enemy a thousand feet above and a thousand yards beyond. Only one of them worked. The magnesium flare would usually go off on all of them, but the parachutes would be ripped and they would just plummet down. That tips off the enemy, and you don't have the advantage of illuminating him properly; so you are worse off than by just firing without them. Our ordnance department was just miserable before the war. When the chips were down, this is what their product did.

The Japs used searchlights. So, it was alternately day and night with their star shells, when they were burning, or a searchlight; they all seemed to be pointed between my eyes. Well, the Marines ashore called it spectacular. They stopped fighting on Guadalcanal and watched this fireworks display; and when a shell would hit a ship, it was like a giant grindstone with sparks going out.

As I said before, our ordnance was terrible. On the fantail, both of my 1.1 mounts were terrible guns, quadruple mounts. You could get a pinprick in a circulating water hose and the mount would freeze. Also, the ammunition was unstable; sometimes it would go off when you would load it, sometimes it would go off as soon as it was ejected from the barrel. A sailor was killed in a gunnery practice because they were such terrible guns.

Both of my mounts were wiped out, and not by pinpricks in the circulating water hose; but by direct hits from a Jap cruiser. This was on the starboard side, and a destroyer did unbelievable damage coming down the port side. The gun barrels were twisted and all that. I mean, they were totally out of commission, almost at once. Many sailors were in pain. I tried to pull one guy out from under a mount and his legs came out and that was it. I know somebody was blown over the side; he might have jumped over. Every officer had a six-pack of morphine syrettes on his belt and I think the chiefs also had it. Since my guns were out I was in a first aid situation then, and I was using my morphine syrettes on the people who were hollering the loudest. I had just kneeled down to give somebody a shot, when turret three fired. I had already discovered that when that turret was trained 1-8-0, if I stood up, the center barrel would be directly even with my head. I had previously gone into that turret and tried to talk Rosie Rozinski into painting a red arc there, which he did, but I had tried to get him to do something so it just wouldn't fire. Well, he wouldn't do that. So, it

was in the red arc but it fired anyway, and I had just knelt down to give this guy morphine and the blast just flattened me out. If I had been standing, it would have decapitated me. You talk about coincidences. When I ran out of morphine, I took a six-pack from a dead chief or officer and I used most of that up.

The ship was going in a lazy circle. There was a lull in the fighting. I was normally supposed to be on the bridge, so I wanted to go up and see if anybody was alive and if anybody was in charge. The hangar was ablaze and I asked for three volunteers to lead a hose around turret three--this was while she was still firing to starboard--to put the hose into the ship's hanger because we had some airplanes with their wings folded in there. There were four-hundred pound depth charges for aerial use in the hanger instead of in the magazine plus all kinds of inflammables, and that hanger was really on fire. So, after leading that hose in there, I went on up forward to the bridge. The first person I saw on the signal bridge, which was the flag bridge just below the navigation bridge, was Rodney Lair, the chief engineer. He had come up from the engine room. He had lost communications and he wanted the same thing as me. He wanted to see if anybody was alive and what was going on. The engine spaces had not been damaged. We still had full power, but they were full of smoke until they shut the flappers. He was night-blinded, so I think the two of us found McCandless in the conning tower, which is on the flag bridge level. The nav bridge was a shambles, everybody killed up there. I don't know what happened to Rodney Lair. He probably went back down, but I stayed with McCandless and we re-established ship control.

Donald R. Lennon:

At that point, the ship was completely out of control. There was no one navigating it at all.

John E. Bennett:

That is right and the primary steering control on the navigation bridge was wiped out. The secondary was ship control aft. That was wiped out. The tertiary was in the conning tower.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the captain and admiral both dead?

John E. Bennett:

The captain was supposed to be in the conning tower, but he never was. That is the purpose of the conning tower, but they never did that. They stayed up on the nav bridge where they could see. The conning tower had these little slots. The admiral was supposed to be there on the signal bridge, which was the flag bridge when we had a flag aboard. So, we had steering control by telephone, from a wheel that was back in the shaft alley, way down below. That was called steering aft, as opposed to ship control aft, which was up in the after superstructure that had been all burned out by that airplane crash. We had a quartermaster in a station adjacent to central station, the damage control station, down below the Marine compartment, which was flooded. His name was Higdon and he was on the wheel there. I have never been able to determine when that wheel had steering control of the ship and when the one back aft did. Just recently I talked to Radioman Rogers, who is a hermit up in Oregon. He won't come to any meetings or anything, he's bitter. But he was in the conning tower this whole time, and he said that it was always steering aft; but I know that Higdon had it at one point. When I was alone in the conning tower, I determined that Higdon, in central station, sounded dopey and was sleepy, because he had gotten smoke in there until they had shut the flappers. He had this “drip, drip” from the flooded compartment coming down the closed hatch, and it was vital that he remain alert because telephone communication to him was our last link to steering the ship. I told the talker to keep talking to him to keep him alert. At one point, McCandless went out to see who was

alive and then he came back. Then somebody, a JG, was sent down to help me from somewhere.

The HELENA came up our starboard quarter with her fifteen six-inch guns trained on us, thinking that they had passed us earlier, upside down, capsized in the water. How in the hell they could recognize the SAN FRANCISCO, upside down--I could never do it--but a HELENA officer told me, "We thought we'd already passed you." There was this burning hulk that they were coming up on. They thought it was a Jap and they sent us the major war ship first challenge, which was three letters. Well, we should have sent back the first reply, but we didn't know what it was. It was up in the nav bridge all burned out. So Bruce McCandless had his flashlight, because two signalman from signals aft had drifted up and brought this flashlight, and he had them send “CA38, CA38,” our number, to the HELENA and they accepted that, thank God, instead of opening fire. They had already given the “Stand by to commence firing” and like, “beep, beep” and there was one more beep and they would have blasted us, but they accepted it. Then McCandless told them, “You are senior surviving officer, please take command of the task force” and, of course, what was left? So anyway, the HELENA then, a little bit later, sent a rendezvous. I've got that piece of paper. I'll send you a copy of it. It says latitude, longitude. It's written on lined paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

So at this point the HELENA had not been damaged herself, severely.

John E. Bennett:

No, she never was. She got about as much damage from the JUNEAU blowing up the next day; a piece of the JUNEAU fell on HELENA and fell on us, too.

The HELENA sent “0425 rendezvous, latitude, longitude, HELENA speed 1-8,” I believe. I have that. So, we were just following the HELENA. All we could do was tell the helmsman right and left rudder; and the rudder angle indicator was fifteen degrees out, too,

we discovered. So, we were following her out Sealark Channel and it was dark as hell, but we saw her wake. I could see this black shape. After a while my roommate, Dick Marquardt, who was in sky forward called down. He said, "You're about to run aground on Malaita," and so I put the rudder right full. It turns out that in following the HELENA, the island had come up and it had loomed bigger and bigger and had hidden the HELENA. The HELENA had kind of slipped out and made a turn and I was following the island. I was going to run aground there and Marquardt said, "You're about to run aground Malaita." I put the rudder right full; and then the damage control people forward sent word, “You're ripping out the shoring,” from the waterline hits--they put shoring up, you know, plates and pieces of wood.

It was starting to get daylight and HELENA told all ships “Stand by to commence zigzagging, plan eight.” Would you believe that I had memorized a zig plan, zigzag plan eight. We used eight all the time. It probably had the fastest speed of advance. In a zig plan, where you've got a base course, then in eight minutes you turn right twenty degrees at twelve minutes, left at 15; that kind of stuff. I didn't realize that I had memorized it. The officer that was sent to assist me, Lieutenant J. G. Tazewell Shephard--God knows where he had been--arrived in a state of shock. I wanted to find McCandless and also I was exhausted. I wrote down the zig plan in chalk on the bulkhead; and, where did I find a piece of chalk? I don't know. I asked Rogers later, "Did we have chalk in the conning tower?" It came from somewhere and there it was written in chalk. My watch was smashed and Taz wasn't wearing a watch. The admiral and his staff were lying there dead, without any signs of any violent wounds. In fact, there was water sloshing all around. That was because the midship's repair party led a fire hose up the superstructure and they were wiped out to a man

but there wasn't a pinprick in the fire hose, so the water was cascading down. I picked this pocket watch off Jack Wintle, who was the aide to Admiral Dan Callaghan, who was lying right beside him, and I gave that to Shephard. Shephard was qualified as officer of the deck, so he could handle it. I went to find McCandless.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was McCandless senior officer at that time?

John E. Bennett:

No, the senior was LCDR Herbert Schonland, who had been passed over twice for commander. He was assistant first lieutenant. He was down in damage control and he was the senior surviving officer. When McCandless had determined that, Rocky Schonland told him, "You keep the conn, you're the guy that knows what's going on up there." He said, "I'll stay down here in damage control," which he did. McCandless was a sharp guy. A good man. He got the medal of honor. Anyway, I found him in the captain's sea cabin sitting on the edge of the bunk and he had blood coming down from little shrapnel wounds in his forehead. Also, I didn't realize at the time his ear was practically shot off. With my grubby fingers, I picked little pieces of shrapnel out of his forehead.

A fire hose that was left unattended was significant to the ship's navigator, Rae Arison, who was also task group navigator. When the firing commenced, we got our first hits in the pilothouse. He was in the chart house, just astern of the pilothouse. He went through the light lock into the pilothouse and was night-blinded, so he went back into the chart house. While he had stepped out, they took a direct hit, a six-inch hit, in the chart house. So, his charts were gone. There was no reason to stay in there, so he went back into the pilothouse. They were getting hit some more. He went over to the port wing of the bridge. We got another hit from the starboard bow. At one point, we had a battleship on our starboard bow coming down. We opened fire at twenty-eight hundred yards, which

passed at point blank range, and there was another one astern of her almost dead ahead, sharp on the starboard bow. We had this destroyer coming down, close aboard the port bow; just absolutely every bullet he fired hit a vital place and then we had cruisers over here. They had no heavy cruisers. They were light cruisers, it turns out, in this group, but Arison was blown off the bridge. He landed on number two five-inch gun on the deck below draped over the barrel. The gun fired at a destroyer coming down our port side. He was blown off the barrel. He wound up face down in a scooped out portion of the teakwood deck that was full of water from this hose. He was unconscious and he was about to lose his life by drowning after all of that. A black mess attendant named Leonard Harmon--they are called stewards now--was a loader on the gun and the gun was shot up, so he was taking care of the wounded. He spotted Arison when a star shell or searchlight illuminated him, it was alternately bright day and black night, and he pulled him around to safety. He saved his life. Let me divert to Harmon. He was killed. He saved another fellow's life later, giving up his own. He got a Navy Cross posthumously. His grandson, Leonard Roy Harmon II, was an apprentice aviation mechanic striker, in a helicopter squadron on North Island, San Diego. He was on a cleaning detail in a building and he looked up and here was a bronze plaque to his grandfather. It was in the enlisted quarters, BEQ--Bachelor Enlisted Quarters--called Harmon Hall. I tracked him down in Texas and also his father. It took forever, too; he was out of the Navy. I wrote a long letter about Leonard Roy Harmon, a very fine man. He was the first black to have a Navy ship named after him, too. It was the destroyer escort, the HARMON.

So, back to the SAN FRANCISCO.

Donald R. Lennon:

At this point in time, you all were just trying to get out of there, weren't you?

John E. Bennett:

Yeah, at this point, we were trying to get out and we were following . . ..

Donald R. Lennon:

What was left; the HELENA and the SAN FRANCISCO, and what other ships were left?

John E. Bennett:

OK, the HELENA was in charge at this point and the SAN FRANCISCO was on her port quarter, after we cleared Indispensable Strait. The ATLANTA was left dead in the water and had to be scuttled at Guadalcanal. The PORTLAND was left off Guadalcanal. Her rudder jammed due to a torpedo hit and she was going in a circle. When it got light enough, the PORTLAND spotted a Jap destroyer dead in the water and sank her.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would have thought that the PORTLAND and the ATLANTA both would have been perfect targets for the Japanese.

John E. Bennett:

Well, they were running away, and we left the battleship HIYEI dead in the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

You fought them to a standstill then.

John E. Bennett:

Yeah, we left her dead in the water and she was so low in the water, that the next day, the air group from the ENTERPRISE and Henderson Field had a difficult time finishing her off. They got the ENTERPRISE underway from Noumea. One of her elevators, number three elevator, was still out of commission from bomb damage. They had yardbirds trying to fix that. They got underway and they launched their air group or a squadron, at least, as soon as they were within range of Henderson Field. They landed there and refueled and they had torpedoes, but the torpedoes were set for ships at the normal condition. The battleship HIYEI was very low in the water, and all these torpedoes were hitting her armor belt, which had been lowered, and they weren't sinking her. God, I can't tell you how many torpedoes it took to sink her and she's just sitting there dead in the water. But, she finally

sank. We had left her that way and the KIRISHIMA came back the next night. Those people must have been ready to desert, but it was so important to the Japs that the next night they came back. In the meantime, we had our battleships WASHINGTON and SOUTH DAKOTA that had just gotten out to the area. When they came up for the second phase of this, the SOUTH DAKOTA was damaged. It was battleship to battleship, at night, surface to surface, the first engagement of that type and the last in the history of anybody's Navy, and the U.S. won.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't participate in that second night, did you?

John E. Bennett:

No. I didn't think they would be coming back, and of course, we were out of it anyway.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what about the JUNEAU. You said that she got hit.

John E. Bennett:

OK. The JUNEAU was over here. We had three destroyers. All but one had jettisoned their depth charges the night before, which was tactics standard policy, I guess. The one that still had depth charges either had a jammed rack or for some reason didn't do it, but her sonar was out. So, two had sonar, but no depth charges and one had depth charges, but no sonar, so we did not have a single effective ASW ship. Captain Hooper, the skipper of the HELENA, had asked COM SOPAC for air support. By the way, there had been a Jap carrier two hundred miles north of us the day before. So, when we were burying people at sea, coming out of there, we were putting one five-inch shell in each canvas; one body, one shell in canvas sewed up, and we just rolled them over the side. We didn't have a chaplain. There was no military burial at sea. I don't want that to get out until all the survivors of all the people are dead. I had to tell some that their sons were buried at sea with full military honors.

Donald R. Lennon:

In a situation like that, you really don't have the time nor the wherewithal to accomplish . . . .

John E. Bennett:

One guy was blown through a ladder and later I went to his house near Chicago where they kept his room just as it was, and they had a flagpole with a gold star base. I had to tell that family what the military burial at sea was like with the chaplain, the flag, and all that. Of course, the poor guy was just in pieces.