| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #131 | |

| Capt. Leon Grabowsky | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| June 7, 1991 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Donald R. Lennon |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, begin by thinking back to your early background, where you were born and grew up, and we will take it from there.

Leon Grabowsky:

My name is Leon Grabowsky, Class of 1941, Captain, USN retired. I was born in Paris, France. My parents were refugees from Polish Russia. They settled in France because my father was in trouble with the tsarist police before World War I. He was freedom loving, and it was a police state; and, to complicate things, both my mother and father were Jewish. In my early youth, they told me about the pogroms and the things they had to go through in the late 1800s and early 1900s. My father married my mother in 1910 or 1911. They had two children within fifteen months and then my father was summoned for military duty. He didn't want to go, because he had a wife and two children. He escaped to Germany, he knew all the smuggling routes and made his way to Paris, France. He made enough money to send back to his family in Lodz, Poland, where they hired smugglers and got out of the country with the two children. That was pretty tricky.

My father was a baker by trade, so my parents opened a donut bakery in Paris and were doing very well in the years leading up to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. They were very happy in Paris. It was a free country, and they had never seen anything like this before.

Neither one of my parents could speak French very well. When the war began, the government clamped restrictions on supplies immediately, and my father went down to sign up for supplies: flour, butter, and other things to make donuts. That is what his bakery was doing: selling donuts on the boulevards in Paris. The authorities had him sign a bunch of papers and the next thing he knew, he was in the Foreign Legion at the Front. The Germans were eleven miles outside of Paris. He dug trenches for the next three years as a Foreign Legionnaire and wound up with shell shock.

In the meantime, my older brother was born. My mother had been starving all this time after the war began because she couldn't speak the language. It turned out she was pregnant. The baby, born in February 1915, was mildly retarded because of lack of nourishment. That was my next older brother.

My father was shell-shocked and was cashiered from the service in 1917. He came back to Paris and tried to pick up the strings. Of course, my mother immediately got pregnant again. That is what happened in those days. I was born in September 1917. That was all through the bombardment of Paris by the “Big Berthas” and things like that, so I had a rather hectic beginning.

My father was a pretty good gambler. He won enough money playing dominos and billiards to go to Le Havre. My parents always wanted to come to America. My father had a brother that deserted from the Russian Army after the Russo-Japanese War. He made it

over to America and kept in communication with my parents. There wasn't enough money in Paris, so my parents packed up and went to Le Havre, thinking it would be easier to get to America from there. They opened up another donut bakery and again my father was lucky. He gambled and made enough money to get passage to America. He immediately went to the American Consulate and got the necessary papers. Before 1920, it was easy for people to get passage to America, but after that all those laws came into effect. My family was doubly lucky.

By that time my parents had four children. They packed up the four children with their papers and took passage in steerage on a ship named, I believe, LA FRANCE. I was less than three years old. We came to Ellis Island and managed to get through that hassle and settled down with my father's brother in a place called Paterson, New Jersey. Paterson was the big silk city of America at that time. Lodz, Poland, was one of the big weaving centers of Russia. My uncle was a weaver so he became fairly prosperous in New Jersey doing weaving. A lot of the immigrants had come from Lodz.

My father got a job baking for the Jewish bakery in Paterson. For the next ten years, he saved enough money before the Depression began to buy a three-story house. We rented two parts of it and we lived on the top floor.

I went to elementary school and graduated when I was thirteen, and then I went to high school. I was the first one in my family to go to high school. My older brother, who was nine or ten when we arrived in America, never went to high school, and my older sister never wanted to. She wanted money. She, like all immigrants, had trouble with her firstborn--the first generation. She married when she was seventeen. I was still in school.

I went to high school for four years. I joined the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, and became a member of the Leaders Club.

We became very poor during the Depression. We lost the house and many of our possessions, just like everybody else that had anything of value did. I think my parents had around $700 in the bank, and when the banks closed, they lost their money. Then they couldn't pay the mortgage, so the house was taken away.

In 1935, I graduated high school. The only thing I wanted to do was to get the hell out of there. The quickest way was to join the Navy, so I joined the Navy and became a sailor on January 13, 1936. I went through boot camp in Newport, Rhode Island. It had just opened up about six months before. They were already beginning to get ready for the war. I told them at the training station I was going to try to go to Annapolis. They cut off my boot-camp leave--we had fifteen days--and put me on a transport going around to the West Coast. They wanted to put me on sea duties as soon as possible. Nine months of sea duty were required before I could go to prep school. No one thought that anyone could make it into the Naval Academy during that time without going to the Naval Academy Prep School (NAPS) in Norfolk, Virginia. It is in Bainbridge now, I think.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you enlisted and told them you wanted to go the Academy, did they test you to see if you had the aptitude?

Leon Grabowsky:

I made the highest grades in GCT in my company.

Donald R. Lennon:

Okay, so they did test you?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes, I was number one. They tested everybody. In the general certification exam, it was called GCT then; I made a 94, which was phenomenal. They said, “Okay, you want to do this. You are qualified to take any rate you want.” They recommended that I be a

pharmacist because of my grade. I said, “No, I want to try for Annapolis.” I was given a real hard time because I was a smart-ass kid trying to be better that other people. I was on this transport, the VEGA, for the next three months, stopping from port to port, going around to the West Coast. I worked in the scullery; I was in the cook shack; every sloppy job they had--mess cook, whatever--I got because I was that smart-ass kid that wanted to go to Annapolis.

I finally got to the West Coast. I was assigned to the USS CINCINNATI, a light cruiser, a four-stacker, very seaworthy, but she rolled like hell. It lasted through World War II. I was vulnerable to seasickness at the time. They put me in the deck division, the second division, which ran things from the rear end of the cruiser. There were around four hundred in the crew. I became a side cleaner. Do you know what a side cleaner is on a ship? You go over the side, up and down, just scrubbing the side of the ship.

I met another sailor aboard, who was to be a classmate of mine at the Academy, Mike Burbage. He was a sailor on the ship. They suggested I talk to Mike and see what we could do together. Mike was in charge of the side cleaners' shack, so he could study. He was a big guy and nobody would fool with Mike. I wasn't quite that big. We studied together for a while. He took the exams for the prep school. Since I would be shy one month of sea duty when it came time to go to prep school, they wouldn't let me take the exam. The skipper sighed and said, “No, you need the full nine months of sea duty.” He wouldn't request a waiver. I decided to try directly from the Fleet. That was my last opportunity. Mike was selected for the prep school. He went to NAPS. A hell of a nice guy! He told me what I had to do--study like hell.

I was a pretty wild kid until that time. I never went ashore again after that, except to rent a room and study. I was in constant trouble on the CINCINNATI, because I was this smart-ass kid who was trying to go to Annapolis. On top of that, I was Jewish. That didn't help. I was pretty tough. After fighting half the crew, I got their respect to a certain extent. I stayed on the CINCINNATI.

I didn't have the money to get books. There was a course that would provide all the books that would cost $50. I was sending home $20 of the $36 I was making because of the bad conditions at home. I wrote a letter and said, “Please send me $50 so I can get these books.” They came back with a letter that said, “We have talked to our milkman, he's Jewish. He was in the Army for three years and he said, 'You don't have a chance. It will be a waste of $50.'” They didn't give me the $50.

I was really pressed about that time. My junior division officer, a guy named Thurston--a hell of a nice guy--said, “Well, why don't you try to make Seaman? You would make $54 a month and have enough money to pay for your education.”

I said, “I am not eligible, I don't have the time.” It took three months or so of sea duty and that was in September of 1936.

He said, “I will check and see if we can get a waiver or something.” He came back and said, “Hell, you will be eligible by one day, if you get your courses in right away. You will have three days to do your courses.” There were twelve courses that had to be taken. I sat down and knocked out all the courses and turned them in. He came back and said, “You are eligible. We'll put you on a list to take the Seaman's exam.”

In those years, people stayed Seamen 2nd for five or six years before they made Seaman 1st because it was a competition. They had so many rates to make Seaman for the

squadron of three cruisers. There were around twenty or thirty rates available and there were around two hundred guys going up for it. I sat down and took the exam with all the others. I stood one, of course. I didn't have the experience and I wasn't recommended for it, but because I made such a high grade, they had to give me the Seaman 1st rate. They said, “God damn it, if you are a Seaman, you are going to behave like one. From now on you are in charge of these five guys. You take care of all the compartments in the division.”

I did. I wound up every night studying down in the steering-engine room when we were in port or at sea. It was my little place to keep clean. As long I stayed out of everybody's way, they didn't see what the hell was going on. I was doing paper after paper. I was making $54 per month, so I was able to pay for the course. Belcher was the name of the organizer of the course; he was a Naval Academy grad and he had this correspondence course. I would send in all of my assignments and do all the work and write stuff for the officers to look at. They were quite impressed with how well I could write.

If I don't talk too well, it is because I just discovered recently that I have Parkinson's disease. It affects ones coordination. The tongue is one of the first places that it affects.

Donald R. Lennon:

It isn't coming across verbally.

Leon Grabowsky:

It doesn't?

Donald R. Lennon:

It sounds fine.

Leon Grabowsky:

My daughter is a doctor and she discovered it about two months ago. She said, “You better go see a neurologist. You may have Parkinson's.”

The neurologist said, “Yes, you have Parkinson's.”

I asked, “When is it really going to hit me?”

He said, “You never know.” They put me on medication and it didn't do anything so I stopped. He said, “Well, just forget it. If it's not broken, don't fix it.” So I am going on--not worrying about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Frequently with Parkinson's, you can go years and years without any signs at all.

Leon Grabowsky:

That is probably what is happening to me. I started loosing coordination. I was a pretty good handball player up until about three or four years ago. I started missing the ball. I was a good skier up until three years ago, but I had to quit skiing because I was getting uncoordinated. Now I am playing racquetball. I wonder when that is going to go. There are medications, but I am not taking them yet. Where were we?

Donald R. Lennon:

You were working on the courses, preparing for the Academy exam.

Leon Grabowsky:

I did this until April of 1937. April was when the exams for the Naval Academy throughout the Fleet were given--three days in the first week in April. Everybody took the exams at the same time. We were on our way to Dutch Harbor for maneuvers. During the three days of exams we began our second day at sea, practically in the midst of a hurricane. I was horribly seasick. I had a bucket in one hand, throwing up, and taking exams with the other. I felt I blew it because I was so damn sick when this was going on. For three days this went on with my taking these exams, two per day, in six different subjects: American History, Ancient History, Algebra, Geometry, English and Physics.

Donald R. Lennon:

I presume your captain or one of the officers administered the exams?

Leon Grabowsky:

The captain appointed his navigator to be in charge. His name was Lieutenant Commander Fisher, and I will never forget him. He was also in charge of the board that was reviewing my eligibility. The board members said, “Okay, he's qualified to take the exam.” I took the exam.

We finally came back from Dutch Harbor and went to Hawaii. One day out of Pearl Harbor, a message came in and said, “Detach Seaman Grabowsky. Send him to the USS NEW YORK for transportation to Annapolis. He is qualified to enter the Naval Academy.” That scared the hell out of the guys I had had the fights with on the ship. I got leave instead; I waived the transportation. I took leave and went home for a month, and then went down to Annapolis on the fifth or sixth of July, 1937.

On July 10, I entered the Naval Academy with the rest of the guys from the Fleet. Back in those days, a hundred people were permitted to enter from the Fleet. Around sixty or seventy usually came from the NAPS, the prep school. There were fifteen in my class that came from the Fleet directly. I was one of them. They all flunked out in the first year or so because they really weren't qualified. I don't know how they passed the exams. I survived. I had never had problems with academics. I had problems with conduct and aptitude because I was a smart ass. I had a great time at the Naval Academy. That was a different world for me.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was a completely different world. What about the situation considering your background? You were in a class with Navy juniors and people from very affluent backgrounds. Did that ever create any difficulties?

Leon Grabowsky:

There was little anti-Semitism; I don't think anybody even knew I was Jewish. I didn't go to Jewish church. My parents were completely irreligious. They didn't pay any attention to religion. They were too busy trying to survive. I was blond and blue-eyed, very well built and tough, and I was accepted immediately, especially coming in from the Fleet. I had one step up on everybody else anyway because I knew what military discipline was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Being accustomed to studying on your own and developing your own courses, I suppose the change in the type of instruction they gave at the Naval Academy was not as difficult for you as it would be for someone who had been at one of the universities where the faculty took a different approach to teaching.

Leon Grabowsky:

We were on our own at the Naval Academy. The preferred way for me was to study on my own and come in and be quizzed. That was the way they did at the Naval Academy. We drew slips and wrote our answers on the blackboard, or we wrote the answers on the paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were probably better prepared than some of those who had been to one of the universities?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes. I stood in the first fifty or so in my first year. I always was good in math. My weaknesses were English and things like that because of my background. I spoke French my first three years, then I spoke Yiddish for the next three years until I went to school. I started speaking English when I was away from home. In New Jersey, no one speaks correct English anyway. I had to relearn English after I joined the Navy. When I would come home, my family wouldn't understand me. They would say, “You have a Southern accent.”

I would say, “No, that's just correct English, because I am studying for Annapolis.” I made a point of reading a lot of books and learning how to pronounce the words right. In New Jersey, it was entirely different. It was just like Brooklyn.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular aspects to your education at Annapolis that stand out in your mind. Any individuals or any particular incidents that you were involved in?

Leon Grabowsky:

Well, I had a different philosophy about Annapolis. I knew I would have no strain passing all the subjects because that was Annapolis. I wanted to get culture at the same time. I knew I had a weak background in the classics and stuff like that. I read all the classics, all the great authors. We had instructors at the Naval Academy who were wonderful teachers such as Alan B. Cook. He introduced me to literature. Hell, I read all the romantic poets. I just ate it up, because I was so hungry to learn all this stuff. In high school in New Jersey, the teachers didn't teach any of that. I had friends that read the latest authors such as Thomas Wolfe, and they would let me borrow their books.

Donald R. Lennon:

I grew up on Thomas Wolfe myself, being a North Carolinian.

Leon Grabowsky:

It was just an eye opener to the whole world. I read all the eighteenth century writers, Thomas Hardy and many others. I read all their books. I was just so fascinated by the beautiful writing. I educated myself as much as the Academy ever educated me. I did have problems with the Executive Department because I was a dreamer and I had two left feet. I was always on report for stupid little things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Such as.

Leon Grabowsky:

Talking in the ranks, things like that. I didn't pay too much attention to regulations. I had friends who were always in trouble; so I had to be in trouble with them. Colonel Perry, who was then the anchorman in my class, was my best friend. He was at the very bottom of the class in everything. He is a very adventurous guy. We were inseparable companions. We were friends who did everything together. We usually wound up in trouble. The nature of this guy was to be adventurous. If there was an opportunity to get away from the Academy for a weekend, we did it. My roommate was part of the Boat Club. We would get on the ketches and go to Cambridge or Oxford on the Eastern Shore and wind up

swimming after midnight in the lagoon. People sometimes wondered whether we had drowned or not. We were both great athletes, tough. It was fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you graduated in February 1941, you were assigned to the USS ARIZONA.

Leon Grabowsky:

USS ARIZONA. I was an ensign in the engineering department, assistant A Division officer. A series of events started happening about that time that saved my life.

Donald R. Lennon:

The ARIZONA was at Pearl at the time you went out on the troop ship with all the other men?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes. The USS HENDERSON.

Donald R. Lennon:

You went out from Seattle?

Leon Grabowsky:

No. San Francisco. I reported aboard the ARIZONA and once again it was a new world for me. It was the first time that I had ever had any money in my pocket. We made $125 a month and I was rich. I love the water and I am a real good swimmer. I always was fascinated by surfboards, so I bought a surfboard from a kid. Everyday after work when I was not on watch, I would go to Waikiki and surf all day. I had enough money to buy a drink or two, so I would buy a couple of drinks and then I would come back on a ten o'clock train. I would be awakened about five o'clock in the morning by Admiral I. Kidd. He got all the ensigns together and made sure they worked out at six o'clock in the morning. He was very fond of the Class of 1941, because he had a son in 1942. We would run around the track like crazy and swim and never get any sleep.

Captain VanValkenburgh loved the steam whistle. That whistle was usually more than we could stand. If it wouldn't work he would say, “Get that god-damned whistle fixed.” As the A Division officer, I would take a couple of men and crawl up through the stack while the ship was steaming and wrap the steam line with asbestos, or what ever the

hell was used to keep it from leaking steam. We may have done it at sea, but I know we did it in port all of the time. As a consequence, between the short hours of sleep I had and breathing all these stack gases from way up in the smoke stack, I developed pneumonia in May of 1941. (I am telling you all this because it has significance later on.) I wound up on the hospital ship MERCY. For three weeks, I was in real bad shape. Fortunately, they had just discovered sulfa drugs and that is what saved my life. I was very weak and very sick for quite a while.

The Navy soon started these “procreation cruises.” Do you know what they were? There was a mutiny, practically, in 1941, because the sailors' wives were all leaving them in Long Beach and living with other people. Consequently, the Navy established a policy of rotating ships for two weeks on the West Coast every three or four months so the families could be together. We called them “procreation cruises” because the wives all got pregnant when this happened. In early July, it was the ARIZONA's turn to go back on a “procreation cruise.” I got sprung out of the hospital, even though I was very weak, because they figured it would do me good to get out of the tropics for a while. I got back to the West Coast for two weeks and got healthy again. Everything was fine. I got back on my job. I didn't do anymore stack work because of my health.

In early August of 1941, we went on an extended cruise for two weeks at sea with the Fleet on maneuvers. The doctors on the ship were obliged to give annual physicals to all their officers. They decided to do it during these two weeks. I had taken my annual physical in January before I left the Naval Academy. There were five of us out of '41 on the ARIZONA; the others were exempted from taking another physical, but because of my sickness I had to take another one.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were given a physical?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes. The reason I am telling you all this is because it saved my life in the long run. I took the physical and I flunked it. I had albuminuria. They thought my kidneys were not filtering albumin. They thought it was a consequence of my illness in the spring. As soon as we got in from this cruise, they sent me over to the hospital again. I spent three weeks with doctors who were all trying to find something wrong with my kidneys. They had me run in the mornings and do different things everyday and take tests. Every afternoon, I would go ashore and ride my surfboard.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you felt fine?

Leon Grabowsky:

I felt fine. There was nothing wrong with me really. After about three weeks, they said, “We can't find anything wrong with you. We have given you every test in the book and we can't find anything wrong with your kidneys.” They finally said there was one guy they hadn't checked me through--the guy who looked at the rare diseases. He was in a separate section of the hospital where all the VD patients were. I went down there. He was a little bug-eyed guy who had a bad reputation as a doctor, as an urologist, so they had stuck him down there. He took one look at me and said, “Hell, I know what is wrong with you. Your prostate is way over size. It is too active and you are feeding back into your bladder and that is what is causing your albuminuria. Those stupid bastards up there.”

Donald R. Lennon:

They never even checked your prostate?

Leon Grabowsky:

No. They never checked it. A day later, I was sent back to the ship with this report. An order was later sent to the ship to send Leon Grabowsky over to the Naval Hospital in Pearl Harbor for an examination “to see whether or not he is qualified to stay in the Navy”--a board of survey they called it back in those days. The doctor, who was a commander, said

it was the only way that I could get rid of the paperwork. He told the exec, “Get him over there for a few days and see if he can get it cleared up.” On the fourth or fifth of December, I was sent to the hospital to face a board of survey. I was in the hospital the morning the ship blew up. The doctor is dead, the skipper is dead, everybody is dead, but I am alive. That is why I am a survivor.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you survived due to an overactive prostate?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were a few survivors from the ARIZONA, weren't there?

Leon Grabowsky:

All of my division--I had eighty men in the A Division--they all died. I got out to the ship later that morning while she was all in flames. A lieutenant, an F Division officer, and myself commandeered a motor launch. I helped with the survivors and with the senior Marine aboard, who had been blown over the side. He was all disheveled. He had been climbing the mast with the second lieutenant in front of him. They strafed them and he pushed the second lieutenant Marine, Simonson, onto the platform, but he wasn't sure if he had been killed or not. We went out there to see if we could get aboard through the flames and get on the main mast. We got out to the ship. The stern was still above water and the flag was all ripped to shreds by shrapnel. I took my clothes off and swam through the burning oil, trying to get to the mast, but couldn't do it. We had to abandon the effort. It took me a month to get the oil off my skin. We took down the flag. You see these pictures of the ARIZONA after the battle with the flag waving proudly from the main mast. That is a bunch of bullshit. The flag was carried at the stern during the battle. A day or two later, they put the flag--for propaganda reasons--on the main mast. We folded up the flag neatly.

The ship's carpenter--I forgot his name--was put in charge of it. Nobody knows where that flag is. It is a relic that got lost in the process.

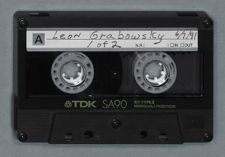

END OF TAPE 1, SIDE AWhile in convoy off the East Coast of the United States in early 1943, the GILLESPIE, being supplied during mildly rough seas, snapped her forward attachment line, a fifteen-inch thick nylon rope. The rope trailed under the ship and became ensnared around one of the rear propellers, rendering the GILLESPIE dead in the water until the line could be freed. There was a great need for the propeller to be cleared quickly, for there had been previous reports of German U-boats in the area, and with the GILLESPIE stationary, the entire convoy was stopped.

The C.O. of the GILLESPIE, C. L. Clement, ordered a diver over the side immediately to cut the line free, but with very few divers with any sort of practical experience on board, Lieutenant Grabowsky realized with his previous training at the Naval Academy and his two years at Pearl Harbor, he was the most experienced diver on board. The crew fit Grabowsky with the heavy diving helm without the rest of the diving suit (time was of the essence) and sent him overboard into the Atlantic at the stern of the ship, with only a heavy rope knife to free the line. He swam underneath the stern of Gillespie being careful to keep as vertical as possible, the air line entering at the crown of the diving helm, for if he moved the headgear far from vertical, the ocean water would proceed to flood the helm. He worked as fast as possible, but the fifteen-inch line had wrapped several times around the propeller shaft, making it necessary for Grabowsky to perform several cuts to insure the prop could turn freely . . . while in the control room, a call had gone out that a U-boat had been sighted.

This warning sent the ship into an emergency situation and the call went down to the stern to haul Grabowsky out immediately, whether he was finished or not. The crew manning the diving apparatus tried to reel Grabowsky in, but because he was under the ship without any ability to communicate, he had no idea that there was a possible U-boat in the area; and because he had nearly completed severing the last of the line away, he didn't want to go topside until he was finished. While the men pulled, Grabowsky held fast to the underside of the ship and continued to cut, even though the constant tugging had pulled him off center, causing the diving helm to fill with water, up past his mouth, nose, and eyes. He finished seconds later, almost entirely by feel, but by that time, the headgear had completely filled with ocean water and he could no longer hold his breath and he started to drown.

Lieutenant Grabowsky was hauled out of the ocean and raised to the deck, where the call went out that he was unconscious and wasn't breathing. The

surrounding crew performed life saving techniques employed at the time, and eventually was able to clear his lungs and get the lieutenant breathing again. It was only at this time that Grabowsky came back to consciousness and recalled being taken to the ship's infirmary where he was kept until being granted a clean bill of health and returning to duty.

In the end, no U-boat ever appeared, (if there ever was one, its presence was never confirmed or denied) and Lieutenant Grabowsky had freed the propeller, allowing the GILLESPIE and the rest of the convoy to continue forward. [note]

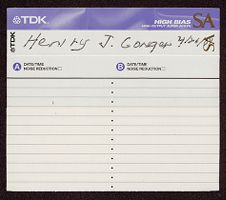

BEGINNING OF TAPE 1, SIDE BLeon Grabowsky:

I was detached from the GILLESPIE October 1943. I went to a school in Washington for three weeks. That was the only break I had during the war--gunnery school--and I should have been to that before I went to the GILLESPIE. I finally wound up in Seattle--Bremerton--taking out a new ship, the destroyer LEUTZE, DD-481. I was gunnery officer. I organized that ship and we shoved off from there around March 4, 1944. We went through training and by the summer of 1944, we were integrated into DESRON 56--Destroyer Squadron 56--the fire support squadron for all amphibious operations. It was composed of nine destroyers. We finally wound up in the war with only one left that was still able to navigate, the BENHAM, I think it was.

We went to every operation, every landing, and provided the fire support. We were the basic squadron for providing fire support. Usually, they had another squadron of destroyers temporarily assigned to the same duty. We were the regulars; the others were just periodically assigned.

The first operation we got into was at Palau. We provided all the fire support for that. I was still the gunnery officer about the time of the Palau operation. The exec was detached and I was made exec; so I was exec and gunnery officer during that operation. That couldn't go on because they needed me in CIC as the exec. Another officer temporarily was made gunnery officer in the Philippines.

We went to the Leyte Gulf operations, the Lingayen Gulf operation, and the Surigao Straits battle in the Philippines. I was awarded the Bronze Star in the Surigao Straits action for my part in it. We launched torpedoes at the Japanese fleet. We were the last wave of destroyers to go in. We were damaged by a shell burst off the bow at Palau. In the Leyte Gulf, we were damaged by an air attack. Two dive bombers came at us--they weren't suiciders, fortunately--and strafed us, causing quite a bit of machine-gun damage. We got one of them, I think. Then we went around to Lingayen Gulf and did that landing. Around twenty-five ships hit there during that operation. We were damaged again, one night in the Lingayen Gulf, just before the landings, by two suicide boats. It was the first suicide boat attack. They mounted depth charges on the bow of a small motorboat and came out and attacked. They would have a trigger on these things and blow you up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now that is a new one. You always hear of the kamikaze planes.

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes. These were kamikaze boats. Fortunately, I was up on the bridge with the skipper . . . it was around two o'clock in the morning . . . when these two “putt-putts” came out. He was sharp enough to realize what they were. Just when they were about to hit our stern, we gave orders to commence firing--to shoot these guys--but everybody was asleep on the fantail and nobody did a thing. We alerted the rest of the Fleet. Well, the rest of the

Fleet of transports got confused and thought we were the attackers and shot up our decks with twenties and forties. It was quite a spectacular affair.

The kid next to me was lookout. I was on a wing on the bridge trying to spot these guys and get somebody to shoot at them. The boats attacked at the right time. They sunk a transport that day. From then on everybody was alert to this. This was the first night it happened. We were the first ones that were attacked and, unfortunately, we didn't alert the others in time.

Donald R. Lennon:

When it is a kamikaze plane, the pilot didn't have much of a chance, but the Japanese aboard the boat could jump out before the boat hit the ship. Did they, or did they stay aboard?

Leon Grabowsky:

No. They just stayed aboard and made sure to hit. We were there the first day they really started the kamikaze business on the Fleet in Leyte Gulf, where twelve destroyers were in screen of heavy ships. It was around the first of November 1944. By that evening, six destroyers had been either badly damaged or sunk. They got the ABNER REED and the guy in front of us and the guy behind us. The heavy ships didn't get hit, but they got all of the destroyers--six out of the twelve destroyers that were in that force.

It got worse from then on. In the Lingayen Gulf, twenty-five ships were hit in the period of a half-day. Admiral Chandler was going to “show” how powerful our force was before the landings, so he had a “demonstration.” We went into the inlet of the Lingayen Gulf and turned around and the kamikazes had a field day. They were excellent pilots. They came in from the ravines, on the water, just “jinking” all the way and they never missed. It was a grim day. Admiral Chandler, fortunately, was killed; so he didn't have to answer up for it.

We went all through the Leyte Gulf campaign, the Lingayen Gulf campaign, and then we went to Iwo. At Iwo we were backing up the underwater demolition teams. We were stationed three thousand yards off of Suribachi as fire support.

The UDTs went in in small boats. They were backed up by thirteen or fourteen LCIs, the gun ships. They went to within a thousand yards. We went to within three thousand yards with seven destroyers. We were shooting like crazy because everybody opened up. Someone made a mistake and sent the LCIs in before the destroyers; so the Japanese thought this was the big landing. It wasn't. It was just the back-up for the swimmers. But the Japanese opened up with everything they had.

There were all kinds of guns on Suribachi. This was before any real damage had been done to the island, three or four days before the landings. We usually would arrive around seven days before the landings and start shooting the place up and softening them up for these UDT teams. Because the LCIs went in, however, the Japanese mistook it for the real thing. There were mortar shells--everything was flying around. I was in the CIC plotting the gunfire. I really didn't know what was going on because I couldn't see. The next thing I knew we were hit. We were hit by a five-inch shell in the stack. Worse than that, I got all these reports: a magazine was on fire under the bridge, a ready room, and then that the skipper had been wounded.

I was the exec and I had to leave my battle station in the CIC and go up to the bridge and take charge. On the way, I stopped by the magazine that was reported to be on fire and, sure as hell, there was smoke pouring out of it. There was a powder fire and it was about ready to blow the whole thing sky high. (I vaguely remembered that I had inspected it a few days before and raised hell with the gunner's mate, because there was a rusty reach rod on

the flooding mechanism. He wasn't too bright. I told him to clean it up, and he disconnected it, but never hooked it up again.) The gunner's mate was there spinning this crank and nothing was happening. I told him, “Get some goddamn hoses and get in there and put out the fire. He and some others did it and saved the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow, that was quick action to put it out before anything happened.

Leon Grabowsky:

I saw the kid last fall and he said, “It wasn't the gunner's mates that did it. I did it.”

He was a sailor on a gun, a kid named Miller. I got decorations for the other two guys, but the guy who really put the fire out never got a decoration. I eventually got to the bridge and ducked in to see where the captain was. The doctor was with him. He had been hit in the neck and was paralyzed from the neck down. We were under intense fire from the beach. Mortar shells were falling all around us; five-inch shells, three-inch shells, you name it, and it was coming at us. There were six other destroyers in line catching the same hell. I said, “God, I've got to do something about this fast.” Even though it was contrary to orders, I thought the only thing that would stop those bastards was to blind them and make sure they couldn't see us. I ordered the guns to start shooting white phosphorus shells, air bursts, on Suribachi--just walk down the mountain with them. It didn't stop them, but they couldn't see us so they couldn't hit us.

Donald R. Lennon:

The accuracy wasn't there.

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes, the accuracy wasn't there. That is what saved our asses. As soon as I did it, the other destroyers did the same thing. The mountain was all covered with white phosphorus and the UDTs proceeded. All thirteen of the LCIs were destroyed. They all were shot to pieces because the Japanese thought the landing was taking place.

I got out of there--I was the skipper then--and transferred the wounded skipper over to a command ship that had medical facilities. He never regained control of his right arm but he could walk and everything.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he wasn't permanently paralyzed.

Leon Grabowsky:

He wasn't permanently paralyzed.

We went back to Iwo for three more weeks, shooting in advance of the troops. We went to Ulithi to a repair ship and had the stack patched up, and then were sent to Manus to pick up the NEW YORK and escort her to Okinawa. She had been damaged and was now repaired.

There were two other destroyers there, DEs. I was the junior skipper, only a lieutenant, but they put me in charge of the screen to take the NEW YORK back. The skipper of the NEW YORK didn't want a DE in charge--he wanted to be in charge--so they put me in charge of the screen.

We brought the NEW YORK to Okinawa about two or three days after the rest of the fire-support fleet got there. It was still about five days before the landing. Then we joined the fire-support group, softening up the beaches and waiting for the landings. This went on for three or four days. The landings were on April 1, 1945.

On the sixth of April, a three-hundred-plane suicide attack came in. It was the main attack. Many were shot down by Task Force 58 fighters, but a whole swarm of them got through. The heavy ships formed up west of Okinawa. We were ordered into the screen from the fire support station on a twelve-thousand-yard circle. Only two destroyers got there while the attack was going on--the NEWCOMB and the LEUTZE. They were in

Station One, around 30 degrees on the bow of the force. We were twelve to twenty thousand yards from the main force and there was no support from the heavy ships.

This main group of suiciders came in on the NEWCOMB and us. We shot down two of them. The NEWCOMB shot down several and then she was hit by four in a row. She was the flagship of our squadron, Commodore Stroop was in command. I went over to pick up survivors. I didn't think there would be anything but scraps of metal left--flaming metal--but the goddamn ship hadn't sunk. So, what to do next? I said, “Well, we will try to save the ship.”

It was just before sundown when I felt she was going down. So I brought the LEUTZE in, backed down full alongside the NEWCOMB, and started giving her the hoses and handy-billies they needed to fight the fires. The crew was congregated on the bow and the stern. The center of the ship was a shambles, all in flames. This went on for around ten minutes and we controlled the fires pretty much. Then one last solitary kamikaze was spotted on the other side of the NEWCOMB, coming in low on the water. I didn't have time to cut the lines or anything. It was too late to do anything, so I said, “Shit, I better just stay here and let these guys get on the LEUTZE.” That was the safest thing to do. That way we would be screened by the NEWCOMB from damage.

The kamikaze guy came in and hit where the flames were and skidded across the deck, plunging overboard between the two ships under our stern. A five-hundred-pound bomb was aboard the plane and it blew up. Then we were in trouble! Everything aft of the engine room was flooded. The chief engineer was a real smart guy and through real ingenious damage control he and his men shored everything up and saved the steering-

engine room. There was enough floatation left that the ship didn't sink from lack of floatation, but it was very close. The deck was awash back aft.

Finally, I had to break away and call the task force commander and tell him I had to leave and to send someone to help the NEWCOMB because she still was in trouble. Both ships were saved; we were towed into Kerama Retto by a minesweeper and spent three months there waiting for repairs. One shaft was completely out of commission. The repairman sealed that shaft up and got the other shaft operating. We left on one engine for San Francisco and arrived around the first of August, just as the war was ending. That was the story of the LEUTZE. I got the Navy Cross and a lot of others got medals for the operation. There were thirteen Navy crosses in my class.

Donald R. Lennon:

You also got a Bronze Star.

Leon Grabowsky:

A Bronze Star for Surigao Straits. And I have three Commendation Ribbons for later on.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the Meritorious Service Medal.

Leon Grabowsky:

The Meritorious Service Medal was when I was skipper of the weapons station, I think.

I don't mind telling you that I think the LEUTZE had one of the grimmer experiences of the war, being in fire support.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was curious about that kamikaze coming in on a burning ship. It seemed that he would have selected one that wasn't already burning.

Leon Grabowsky:

The kamikazes were lousy pilots.

Donald R. Lennon:

They just went for anything that was floating?

Leon Grabowsky:

For anything that was floating. They probably had had three to four weeks training, enough to handle the plane and get the bomb to the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

It almost carried off both of you.

Leon Grabowsky:

They weren't like the kamikazes in the Philippines. In the Philippines, they were good, expert pilots. If they were told to get a ship, they got a ship. It was grim in the Philippines.

Donald R. Lennon:

You brought the LEUTZE back for repair in August of 1945?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes. We were scheduled to be repaired in San Francisco at the Hunter's Point Shipyard. On the fourteenth of August, the war ended. We got orders to decommission the ship rather than spend millions of dollars to repair it. We had been scheduled to go into the invasion of Japan on the fifteenth of September. We never made it. The war ended instead.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you go from there?

Leon Grabowsky:

I spent three months decommissioning the LEUTZE, dispersing the crew and everything. There were formulas for letting everybody go based on time in service. Finally, about early December, I decommissioned the ship with about fifty people left. I got orders to report to the USS GALVESTON as navigator. I went and reported to the shipyard in Philadelphia and found out they had stopped building her. I was given orders to command another destroyer, the USS PORTER (DD-800). I was only to decommission her in the Charleston Navy Shipyard. I spent three months on that. By that time, I had orders to go to PG School in Annapolis. I was scheduled for a three-year course in ordnance and engineering. I decommissioned the ship at the end of July in 1946 and headed for Annapolis. I spent the next three years going to school for Electrical Engineering. I spent the first year at Annapolis and the next two years at the University of Pennsylvania. I finally

got a master's in June of 1949 and went to the USS FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT as gunnery officer. I spent one year on her.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was she stationed?

Leon Grabowsky:

She was stationed in Norfolk.

One day I had the flu and the exec came down to see me in sickbay. He accused me of chicanery of some sort, because he thought I had done something to instigate my new orders to report to Brooklyn Navy Yard in forty-eight hours and take over the gunnery department on the ORISKANY. It was the first of the revised ESSEX-class carriers. She was brand new with a double hull and wasn't commissioned yet. What had happened was that Admiral Forrestal had visited the ship two months before the scheduled commissioning in September 1950. Nothing was happening. All of the operators who lived around New York had gotten themselves cushy jobs as heads of the department on the ORISKANY and hadn't done any goddamn work. The ship was a mess, it was not organized. He wanted the best gunnery officer and the best chief engineer off operating ships to go up there and straighten that out. He asked ComAirLant who was the best guy to send. They said, “By all means, send Grabowsky. He is an experienced gunnery officer.”

So I went there and organized that ship. A good part of the crew was under the gunnery or weapons officer. I organized that for the next three months and got her commissioned. We went to Guantanamo and broke all the gunnery records. It was a fantastic ship for gunnery. I was the first guy to get the MK-49 gun control system to work. They had this system all over the Fleet. It was a new electronic system by GE and nobody knew what the hell it was about. I was an electronics ordnance PG, so I knew what had to be done. I had a good fire-control gunner and he organized things the way I told him to.

Donald R. Lennon:

It would have been a great ship in battle.

Leon Grabowsky:

That is right. She eventually went to Korea and proved she was a great ship. In the meantime, the Korean War had just begun. From Guantanamo, we went to the Med. I was in the Med in the spring of 1951. I made commander in April of 1951, so I was too senior for the job as weapons officer on the ORISKANY. They said that they could catch me in Crete in the Mediterranean, and sent me to CinCNELM as a staff officer--joint section of CinCNELM. CinCNELM had a requirement for all officers to be sent to Psychological Warfare School in Fort Riley, Kansas. Before I ever showed up, they gave me orders for Fort Riley. I spent two months in Fort Riley being trained as a Psychological Warfare officer.

I came back to Naples in the summer of 1951 and joined the staff there. The admiral had been CinCNELM in London and he moved his staff to Naples to be CinCSOUTH, but he had CinCNELM at the same time. I wound up in Naples for a year on the staff of CinCNELM. We were on a ship there part-time and then moved into a hotel that we took over. Then I went back to London because he wanted his CinCNELM staff there.

I was in London, having a great time being on a joint warfare section of CinCNELM, and helped establish US EUCOM in Frankfurt. I was a bachelor, so they detached me--it was the easiest thing to do--and sent me to Frankfurt to be part of US EUCOM. They had to break up the staffs to do this. I spent a year in Germany as part of US EUCOM and then came back to the States in 1953 and took up ordnance duties again.

As an ordnance PG, whenever I went to shore duty, I had to go to an ordnance job. I went to NOL White Oak as an ordnance applications officer and spent over three years

there. Eventually, I was made exec there. The skipper there wanted me as his exec, so I took the job. I was junior to other officers on staff, but he was a very famous admiral, and he said, “I want to grab all these execs.” So he made me exec over the top of all these other officers. I spent a year as exec there at the end of my tour.

About the time my tour was up, they needed a gunnery officer for the RANGER, which was going into commission in September 1957. The admiral promised me a command as soon as I had put the ship in commission. It took a year to put the ship in commission and get organized. I also took the RANGER through shakedown. We went around the Horn and carried her to the West Coast. My classmate Quigley was chief engineer of the RANGER. We both put her in commission together.

I wound up as skipper of the CATAMOUNT in the summer of 1958 on the West Coast. She was deployed to the West Coast and the Far East. I took command in Tokyo. I went down to Kaohsiung and places like that in Taiwan. The Quemoy resupply operation was going on. There were three LSDs out there in our squadron who did the main support of the Quemoy resupply. It was a pretty hairy operation. You had to pick up all these Chinese and load the boats with ammunition and all that stuff and send them into Quemoy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any specific incidents that you can think of in connection with that operation?

Leon Grabowsky:

Only one. There was no shooting involved, but I had orders one day to get underway and pick up a load from Pescadores and head out to Quemoy that night. A destroyer was going to screen us. We always had a destroyer protecting us. We got there and couldn't find the destroyer. I said, “Well, I am going anyway. I have my orders. They will show up at anytime.”

They never got the word, so I went in alone and unloaded all the Chinese and supplies and came out again. When I got back all hell broke loose because I had gone in without a destroyer. I thought it was there all the time. The destroyer never got the word. I got the word, but he didn't. That was a pretty hairy operation all the way.

We headed for Quemoy and the next thing we knew, we had “Axis Sally,” a Chinese Communist propaganda gal, on the radio saying, “We know you are coming.” The Chinese on Taiwan, the free Chinese, would tell them. We were all wondering when we were going to get it. It never happened. The Chinese were too smart for it. They didn't want America involved, so we got away with it. They were a dirty bunch of bastards.

We were based three or four months in Kaohsiung, which is the asshole of creation. Running supplies in every week or so to the Pescadores, a wind-blown group of islands. We came back in December and our squadron was detached and replaced by another amphibious squadron. We operated out of San Diego from then on.

I fell in love with my wife that spring. She was a schoolteacher. We got married in August. I made Captain in September, was detached, and then sent to ARPA, Advanced Research Projects Agency, because they needed another ordnance officer on the staff there. It was just beginning. For the next two-and-a-half years, I did scientific work with some of the most advanced scientists in the country. It was staffed by civilians from universities and big corporations.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of research were you doing?

Leon Grabowsky:

Advanced research on ballistic missile defense. That was the first effort to do something about the ballistic missiles. I was in charge of the project that developed the phased array radar. I had $200 million worth of projects under me. I had about ten PhDs

helping me and we developed the phased array radar, which is the basis for the Patriot system. I had all these crazy projects and I spent money like water. I didn't really have the staff to spend that much money, but that is not the way the way the government does it. They just give you the money and hope it works out.

I spent two-and-a-half years there and I wanted to go to sea again. I got orders to report to the HECTOR, a repair ship out of Long Beach. I arrived in the summer of 1962. I spent a year-and-a-half on the HECTOR, most of it deployed to WestPac, based in Sasebo and places like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you were fairly senior for commanding a repair ship, weren't you?

Leon Grabowsky:

No. A repair ship is a big command. I commanded an LSD in 1958-59, but it was not a major command, it was just preparatory for a major command. As I said, we deployed the HECTOR to WestPac and were based in Sasebo most of the time. I had the flag for the service squadron there on board. I was finally detached from that job and went back to China Lake, California, as exec there, the second in command of the biggest Naval laboratory in the world. It has five thousand engineers and scientists working there. I spent three years there as exec. I was skipper for a month, which was quite an important job, too.

I was finally detached from China Lake in the summer of 1967. I got orders to take command of ComServRon 5 out of Pearl. I had thirty-five ships. I got there in October of 1967 and was ordered two weeks later to take command of Task Force 73.5 off Vietnam in the Tonkin Gulf. I had around twenty or thirty replenishment ships underway--oilers, supply ships, and ammunition ships. That whole winter, I fought the Vietnam War. In the course of this, I determined that we were doing it all wrong.

The way the Seventh Fleet staff had set it up we were bringing half the loads back to Subic instead of keeping them in the Tonkin Gulf; so I organized a system to change this to where we would have main storage ships in the Tonkin Gulf. These storage ships would keep all the assets from the ships that were going back--transfer the materials and keep them there. We needed special kinds of ships to do this.

The SACRAMENTO, fortunately, just showed up and other general supply ships were coming that would have control of all kinds of assets. The next guy that showed up was a guy named Betzel, out of the Class of 1942. The command of the task force was rotated between commanders of service squadrons on the West Coast and Pearl and one of the staff officers from the staff of the Seventh Fleet. Well, this guy from the Seventh Fleet didn't know what the hell was going on. Betzel stopped by to see me before he went out. I told him what I had told the command out there, that they were doing it all wrong and I had this new system that would correct it. He said, “Great.” So he did it. He changed it.

By the time they came out there in the fall, we had the new system for resupplying the Fleet. The assets that were sent out there were kept in the Tonkin Gulf on storage ships, readily available to the carriers. When the ships went out there they started at the south and came up north where they were relieved of their assets in the Gulf. The assets were then transferred to these storage ships. It involved a hell of a lot of handling and the skippers didn't like it, but it was the most efficient way to do it. We saved billions of dollars, I think, because as soon as they were through with their circuit of the coast and unloaded once in Tonkin Gulf, they could head back to Subic to reload and be ready for the next run. They would have left half their assets on the storage ships. They gave me a commendation medal for that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not only would it be more efficient, but also it would seem that it would give a ready supply of goods all of the time. . . .

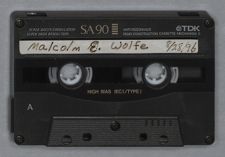

TAPE 2, SIDE ADonald R. Lennon:

While you were on the coast of Vietnam, was there any tension or pressure? . . . I know the North Vietnamese were not taking action against the American Navy. They were so pre-occupied with the ground war and air war that they weren't coming out into the Tonkin Gulf after the Navy at all, were they?

Leon Grabowsky:

I spent months in the Tonkin Gulf and I never saw an enemy.

Donald R. Lennon:

That experience was kind of different from World War II.

Leon Grabowsky:

It was boring. We did anything to stir up some excitement. I would go back to Subic Bay every month or so and make sure everything was running smoothly. I spent two three-month tours of Tonkin Gulf in TF (Task Force) 73.5. Task Force 73.5 was the organization under the Seventh Fleet that was part of Task Force 73, which was the supply mission for the Seventh Fleet. There were around twenty to twenty-five ships usually involved in this. It was just a scheduling operation really. I rode the flagship, the SACRAMENTO, most of the time, and the PONCHATOULA once for a month, to make sure everything worked smoothly, which it did. I got one of my green medals for that operation. It should have been for reorganizing it. I also got a medal from the Vietnamese government. I was recommended by the Seventh Fleet Supply Service Force to be one of the recipients of a medal from Vietnam. It was the second highest medal from Vietnam and it was in recognition of my resupply organization.

Donald R. Lennon:

This lasted from 1967 until...?

Leon Grabowsky:

I went there for the first time in November 1967 to March 1, 1968. Then I went back again six months later in the summer of 1968. By that time, it had been reorganized by Betzel, who went there in the spring. I took charge again for three months. It worked beautifully except for the discontent of the skippers because they had long periods of transferring ammunition and stuff.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any real dangers or complications in having to transfer to the storage ships?

Leon Grabowsky:

It is always dangerous. What is so incredible about the US Fleet is that it can stay somewhere forever and resupply by ships and never see land and never have to go to land, except for the supply ships resupplying. They have to have a base like Subic to get their supplies or else have other ships come out and resupply them. It is a dangerous operation but we do it. We learned the tricks. It is very hazardous. Fortunately, no one has ever been blown up or anything. We don't fight big wars, we only fight limited wars and that is why it works. If we were fighting a big war with submarines, I don't think it would work unless we could isolate places, like at Iwo Jima. You would have to have a permanent screen around the whole island. During the Iwo Jima operation the whole island was protected and we stayed within our perimeter to resupply our operations.

Donald R. Lennon:

It would take a pretty good-sized screen to protect that.

Leon Grabowsky:

It did.

Donald R. Lennon:

There in Tonkin Gulf, you didn't even bother with a screen because you felt perfectly safe?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes, there was no enemy to reckon with. The only ones that could possibly affect us were the Russians and they wouldn't have dared.

Donald R. Lennon:

The North Vietnamese Air Force was not capable of coming out?

Leon Grabowsky:

No. We had enough radar coverage; if they showed up, we shot them down. Just like in Iraq.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you left Vietnam in 1968, where did you go?

Leon Grabowsky:

I went back to Pearl and took charge of my squadron. In 1968, they were looking for an experienced logistics expert to go to the staff of SecDef I&L--Installations and Logistics. I got orders to go back there and serve at DOD, SecDef staff in the I&L section. I spent a year there until the election came along. I was assistant to the special assistant for I&L.

Donald R. Lennon:

Until the election came along?

Leon Grabowsky:

Yes, the Republicans won. These guys were Democrats, so they kicked out the assistant secretary for I&L, Bennowitz.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't know that would affect a career naval officer.

Leon Grabowsky:

I was the assistant to the special assistant, Bennowitz, who found a new job with other politicians. He became a comptroller of the Army. I was left hanging out to dry. I had been writing papers for Bennowitz, so that his boss could get things done that the regular staff couldn't do. The guy who came in after the election wanted to know what the hell I had been doing. I said that I had written this paper, and that paper, and that paper.

He said, “Well, you are the son of a bitch that screwed things up.”

I knew I was out then, so I started looking for a new job. I went over to BuPer and they said, “Well, we just happen to have three weapons stations on the West Coast that need new skippers starting in the summer.”

I said, “Great, send me to Concord.” They sent me to Concord. I knew that was my last tour of duty because they hadn't made me admiral. I spent two years at the weapons station from 1969 through 1971. Then I retired. I had thirty years in.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had an exciting, eventful, and varied career!

Leon Grabowsky:

I have been on a hell of a lot of things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you not been senior and left the ORISKANY in the Mediterranean, you might have been in the Korean War, too.

Leon Grabowsky:

I never got to Korea. The ORISKANY got to Korea. It was one of the main carriers over there. I was detached before they got there. That was not a naval war anyway; that was a naval air war.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other thoughts that you have with regard to any aspects of your career?

Leon Grabowsky:

Well, if anybody wants a life of adventure, do what I did.

Donald R. Lennon:

After you retired in 1971, what did you do as a civilian?

Leon Grabowsky:

I married when I was forty-one. I was relatively old. I had five children. They were all very young when I got the weapons station. When I retired the oldest was eleven--she was born in 1960--and the youngest was three years old, I think, and was born in 1967. I had to make a lot of money. I had been playing the stock market for years and I had built up maybe a hundred thousand or so of assets. When I retired I knew this wouldn't support me. I was making $1,800 a month in retirement money. I borrowed on my stock market holdings and developed real estate partnerships. I went to school at a local college, Diablo Valley College, and studied real estate and learned what it was about. I eventually got a brokers license. Then I studied contracting and got a contractors license. I formed around seven or eight small partnerships in real estate developing. We built several houses at

Tahoe with one of the partnerships. With another partnership, I bought land in Concord, near the BART station. In another partnership, I bought twenty lots in a prestigious development in Danville. I went to work organizing things. I usually was a manager of these operations.

Donald R. Lennon:

I am surprised that you didn't go into engineering with your background as an engineer.

Leon Grabowsky:

Well, I have a master's in business as well. When I was at NOL White Oak, you got an hour off every day to study scientific or business subjects. I did that and got a master's in business while I was there. That is why I did well in the stock market. I knew a lot more about business, but I would have preferred to teach engineering; however, I really was more adept at business things. I organized these companies and did quite well financially; eventually, we built fourteen houses.

The last partnership I had was a big development. We had a financial man who had been mayor of Richmond who got us the money. I was the financial manager and did the accounting since I had two business qualifications. There was another guy who was a real estate broker, an Air Force colonel, who was supposed to handle the sale of the properties that we built. Another guy was a contractor who worked for the Port of Oakland. We thought we had it made, but that was far from the case. They all decided they wanted their money off the top. The agreement was that we all do our work and collect dividends when things paid off. Well, the oil recession occurred in 1973 and we got caught in this inflation bind and everything turned out to be higher priced. We wound up in lawyers' offices and spent all our money on lawyers. That experience taught me a lesson: to never trust a partner. Of course, you are married to a partner.

I still had three or four of these partnerships floating around, and in the meantime, some of them really paid off. I bought a shopping center in Tahoe with one partnership. I owned ninety-five percent of it. There was a lot next to the BART System in San Francisco and we sold a lease on that to some developers. That brings in a good income. I doubled my retirement income from these operations. They also became hairy--I could have been wiped out with that last big one. Fortunately, I was smart enough to stop these guys. It took lawyers to do it and I realized then that that is not the way to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, you have to really be careful.

Leon Grabowsky:

I taught business courses for five years at DVC. That made supplemental income until my ships came in. After the ships came in, I was in clover. I am pretty well off.

I built a house in Tahoe on a lot I inherited, and I started these partnerships in Hawaii when I was on the staff at ServRon 5. One of my assistants had a wife who was a broker out there. She formed a HUEY(?), a partnership, and I was one of the partners. She had written into the contract, and I was naive in those days, that she would make commissions on everything she bought and sold. She wound up buying and selling more that she did investing.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have heard of that before.

Leon Grabowsky:

I made out okay there, but not like I should have. That was the first one I got involved in. It gave me a model to use later on.

Donald R. Lennon:

Thank you so much. This has been a pleasure and very informative.

[End of Interview]