[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

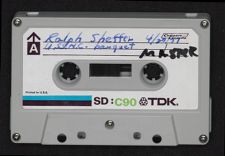

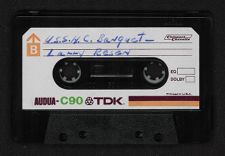

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

Ralph Sheffer

World War II Officer Aboard the U.S. S. NORTH CAROLINA

April 20, 1977

U.S.S. NORTH CAROLINA BATTLESHIP ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM

I had finished law school at Columbia University and I had been working in the field of radio an?? advertising at the time the war started. But many friends of mine had been down in Washington, and several of them had asked me to come down and join them. They were in fairly good government positions down there. These were friends from college and law school. I went down to Washington shortly after the war began and worked in Donald Nelson's office in the War Production Board. I had attempted to join any part of the armed services. I particularly wanted to be a fighter pilot if I could. I was young and single. I applied for the Army and the Navy, but they were looking for younger men than I at that time, because I was about twenty-six or twenty-seven. At the same time I was working with the War Production Board in what they considered a fairly vital area; and they asked me to stay on until I could finish the job, which I did.

Then I applied again to the Navy, and I was accepted in a special group called V-12. These were men who had been in professions. You received a commission, but it was a probationary commission. You had to then go to

Officers Training School; and if you passed the four month period in Officers Training School, then the commission became a firm commission. I did this. I took my officers training up at Cornell University. Shortly thereafter I was ordered with a group of about twenty-four other fellow officers out of this special group of professional men to report to COMSUBPAC with Admiral Halsey at that time in Noumea, New Caledonia.

-2

I was then assigned to the destroyer GWIN and immediately went into action. The very day I joined her in Noumea, we shoved off in the evening. At that time our forces were very weak down there. I think the SARATOGA was the only carrier left in the fleet; and we had very, very few battleships. The NORTH CAROLINA was there, but at that moment she was out on some mission. Our job was to go up with a cruiser group; and we spent the next thirty days and nights just traveling back and forth up what we called the "slot," because the

Japanese, the so called Tokyo express, were sending reinforcements down to Guadalcanal and through the islands there every single night. With a few destroyers and a few cruisers we had in that particular area, we would go up the "slot" and engage them several times a week sometimes. That went on for a period of about thirty days of straight action.

(What was your specific job aboard the GWIN?)

I was the communications officer. I was a boot ensign at the time, but

I was the communications officer because there weren't very many officers. It was an old-type destroyer. We didn't have the new twenty-two hundred tonners yet. In night battle at Kolombangara, we were torpedoed and sunk. We were rescued by another destroyer in that group a few hours after burning and later taken to a rest camp in Dumbea, which is north of Noumea.

(Being torpedoed and sunk is quite a frightful experience. Is there anything in particular that you remember concerning that?)

Yes. There was one feeling in particular. At that time I know that I was not a great swimmer. I had had a drowning experience when I was a youngster of about six or seven. I had been pulled in by the undertow while my mother was watching on an ocean beach. I was pulled under. Apparently my mother screamed and the lifeguard came out, and after searching around, they found me somewhere. They brought me in, and I was completely unconscious. I

-3

had swallowed a great deal of water. In those days they use to roll you over a barrel as a means of artificial respiration. I woke up, and my parents were very protective. I don't think I had a bath for a year or two. They were very protective of me when it came to water.

When I went to college, I wasn't a very big guy. The day I registered some giant came along side of me and said, "Hey freshman, what sport are you going out for?" I looked up at him and said, "What sport do you think I could go out for?" He said that I would go out for crew. I said, "Crew,

I couldn't even carry one of those oars." He said that he wasn't talking about carrying the oar, but that I looked like-good material for cockswain. He said that I was small and light, and he told me to report the next day to the swimming pool and take the swimming test. I told him that I didn't know how to swim. My brother was a professor at Columbia, and the swimming coach was a very close friend of his. The swimming coach said that he would give up his lunch hour if I would give up my lunch hour, and he would teach me how to swim. Which I did. I had to pass the test with clothes on and taking clothes off in the water. I had to pass the same test everyone else did. I was able to do it after about eight weeks of training.

I remember that the one thought that hit me when we were torpedoed and we were slowly listing over and people were scrambling for the high side of the ship and at night and burning--the flames were going up about sixty-five feet in the air--I said that of all the ways to die, that I had to die in the water. Fortunately I didn't

(Were you picked up right away?

It sunk slowly, and we stayed afloat for several hours. The RALPH

TALBOT, which was the name of one of the other destroyers, came alongside and put her bow into our midships and held us up that way until we could

-4

transfer. We lost about sixty of our men and some of our officers who were killed. There were three ensigns on board, and I was the S.O.P. of the three. I and another had graduated from Cornell, but I don't remember where the other chap came from. I sort of outranked them in the date of graduation. They left me and the other two to take care of getting transportation for one hundred and sixty odd men, because usually after a torpedoing, we would get thirty days survivors' leave. All the other officers were immediately flown back by air transportation, and after that they were given new construction.

Right from the start they were assigned to new construction of one of these new twenty-two hundred ton destroyers which were just coming off the tables at that time. Our job was to get the men transferred to the first available transportation home, which we did.

We were all assigned to a rest camp in this area of Dumbea. At that time all I had on me was a set of Marine fatigues and a cap. The Marine fatigues were given to me by the Red Cross because we had to leave rather precipitously from the destroyer. We finally did get the men all assigned to transportation. In this rest camp, we lived in tents with dirt floors and just a cot. We shaved in a stream. It was in a valley between two high hills, and the sun would come up about ten o'clock and go down about four. We had no electricity or any of the modern conveniences. We simply used the oil lamps. It was probably one of the lowest points of my Navy life because, prior to going to Dumbea, we had first stopped off at some island where we were put on shore for a while. All I knew was that I wasn't home. I missed everybody. They had no idea whether I was alive or dead, because we heard a radio report announcing the torpedoing and sinking of our ship, but no next of kin reports or anything else. I remember that we were listening to that radio in a rain-storm, and I was pretty low during that time.

-5

I had a jeep up there as the officer in charge. One day one of my fellow officers, a fellow named John Schiller, who had been my roommate at

Cornell and who prior to the war was an assistant district attorney in his home town of Wilmington, North Carolina. John had a habit of fantasizing during daytime. He would dream up stories, and I used to be very amused as his roommate to listen to these fantasies. He would always think that something really happened, or he would say it in such a way that you really believed him for a while. He asked me if he could borrow the jeep one day while we were still up there--while we were just finishing up getting the men back and my feeling low as hell. He borrowed the jeep and went into Noumea which was four or five miles down. It was the capital of New Caledonia. He came back to the tent about two or three o'clock in the morning, singing, roaring drunk. I listened to him singing and he was singing "I'm going home, I'm going home, I'm going home." I listened to him while he was crawling into his cot, and I asked him what he meant about going home. He said that he had met an officer down at the officer's club who was the reassignment officer of the South Pacific, and he told him that he would send him home. I asked him what he said about me, but he fell asleep. I nudged him, but he appeared to be sound asleep. It was in the dark. I waited until he woke up the next morning, and I said, "John, you said last night that you were going home."

He said, "Yea, I am. I met the man who is going to reassign me."

I said, "Didn't you say anything about me?"

He said that he had really forgotten to say anything. I made up my mind that I wasn't going to let him out of my sight until I had found that same guy.

About a week later, he asked me if he could borrow the jeep again, and

I told him that I was going down to Noumea too and that I would drop him off wherever he wanted to go. I got into the jeep with him, and we drove down

-6

to Noumea. He told me to stop at some point, and he got out and walked away. I drove that darned jeep around the corner and got right out of it.

I pulled myself around the corner, and I saw him going into a large Quonset hut. I zipped a block or so down to that Quonset hut, and sure enough there was a little sign that said "Reassignment Officer, COMSUBPAC." I said, "My God, he's really doing it." I walked into that Quonset hut, and there were a couple of yeomen and three or four desks with sailors behind typing. Towards the rear, there was an office with a screen door. I walked up to the side of it, and I stood by the side of the door to see if I could overhear what the conversation was. There was talk going on in there for a few moments. A door opened and out came a lieutenant commander with his arm around John, and I heard him say, "All right John, we'll send you to North Carolina." As soon as he got out, he came back and he walked into his office. He sat down at his desk. I whipped off my hat and put it under my arm and walked in there and I stood there at attention. He was writing something, and he looked

up and said, "Yes."

I saluted and said, "Sir, I'm Ensign Sheffer."

He said, "Yes. What can I do for you?"

I said, "I'm a survivor of the GWIN."

He said, "Oh, we just had one of your shipmates in here."

I said, "Yes, I know."

He said, "Well, what can I do for you?"

I said that I would like to have the same thing Schiller had. He looked down at his papers and shuffled them around for a moment and said, "Fine, we'll send you to North Carolina."

I said, "Yes sir, but my home is New York. I don't want to go to North

Carolina."

-7

He said, "What do you mean, New York? I'm talking about the USS NORTH

CAROLINA, the battleship. Do you want it or don't you?"

It was just like lightning had struck me. I said to him, "Does it roll?"

Because when I was on the GWIN, I was terribly seasick. I had dropped over thirty pounds in those thirty days from being seasick and rolling back and forth. He said it didn't roll very much and asked why. I told him that I got very seasick. He said, "Take it or leave it. Do you want the NORTH CAROLINA?" I told him that I would take it, and that's how I came to the NORTH CAROL-INA. I spent the next thirty-two months on board.

(Did Schiller think he was coming home?)

No. He was kidding me all this time . He was fantasizing. He really loved to build up these stories. When we were roommates at Cornell, I would listen to him on the phone. He would be talking to some girl, telling her how beautiful she was and how he was going to meet her later tonight and all that sort of stuff. He had his finger on the receiver, and it took me about a week to realize that he wasn't. Ii don't know what it was about him. Now, Ensign Schiller died here about a year ago, more or less. Captain Blee knew him very well too. But that changed the whole course of my career, because I possibly would have been assigned somewhere else in the course of time. But just stumbling on this same fellow and his hearing that I had been a survivor of the GWIN, and the three of us, including the other fellow, got assigned to the NORTH CAROLINA so that the three of us spent practically the whole war together. Both Schiller and Jewel were reassigned before the finish of the war and went to other duties, whereas I was kept on as the fighter director and the combat information officer.

(So you went directly from New Caledonia to the NORTH CAROLINA.)

-8

Yes. She came in to Noumea, and I joined her there. That story I think is very amusing. It was just as if lightning struck when he told me that he was talking about the USS NORTH CAROLINA.

On the NORTH CAROLINA, I first came aboard as a communications officer, which I had been on the GWIN. As it developed, I was sent at some later time, and I believe I either volunteered or asked for this, to Camp Catlin in Hawaii, which was a Marine camp specializing in radar and fighter direction, which was then in the later development stages.

One of the reasons the GWIN was sunk was because in that particular action that night, the Japanese destroyers had shot most of their torpedoes against our task group and had retired over the horizon. We had sent two or three of our destroyers after them. About a half or three quarters of an hour later, some ships were returning over the horizon on the same bearing that our destroyers had gone out. Because our radar in the early part of the war was not so sensitive or good, we were unable to determine if these were enemy-it was dark, about two or three o'clock in the morning--or whether they were our own ships returning to join the taskforce. It wasn't until they came within firing range that a decision was made, and we turned to avoid contact with them. What we didn't know then, at least I certainly didn't know, and I think most of the officers aboard did not know, was that the Japanese had spare torpedoes which they had on dollies. When they shot out all of their torpedoes, they retired, and they reloaded. That's what happened, and they came in on practically the same bearing. Our destroyers didn't find them, and they were still looking. We thought that they would have to turn up at a certain place and that they would have to go a certain way, so they were on an intercepting course. But what they did was to come back on a course very similar to theirs, and they let go a spread of about twenty fish. One of our

-9

jobs was to protect cruisers. That is the job of a destroyer, to protect a cruiser even to the point of taking a torpedo. So we swung over and got hit.

(Did you really know that you were moving into the wake of a torpedo?)

I myself, no, but I think the Captain did. He was taking a position or maneuver, and everything I've read since indicates that we were steaming into a position to protect the cruisers, which was the position we were to take and the job we were supposed to do. The cruisers got hit too, but not so bad. We had an Australian cruiser with us, and she got hit; and we had an American cruiser with us that also got hit.

(You had only been with the NORTH CAROLINA a month at the time of the famous accident, when the NORTH CAROLINA fired into the KIDD. Do you remember that?)

Yes. Now you have got to remember that the fighter director's job was not a job necessarily with the guns. His job was working with the aircraft of the carriers and any airborne combat air patrol. And also I was inboard, the Combat Information Center was inboard, so that I was very rarely at a point where I could see anything happening. I could hear them happening over our intercoms, and I certainly was present at the time when we fired into the KIDD. I was also present at the time when we fired some star shells at some destroyers. I don't think that was at the same time; but accidently one of our men out on one of the gun mounts pushed the wrong button, and three star shells were on their way towards one of our destroyers. I can't tell you anything further about that. Is the��re anything particularly you want to know?

(Proceeding with your reminiscences of your early duty aboard the NORTH

CAROLINA, what were your responsibilities, and are there any incidents that you recall? )

-10

I went to Camp Catlin which was this Marine camp where they taught fighter direction and radar. I particularly wanted to do that because of what had happened to me in the case of the GWIN, where a knowledge of radar in a more sophisticated form would be valuable. When I returned to the ship some six weeks later, I was put into the Combat Information Center as a fighter director officer, and Admiral Celustka who is here, was my superior; and he and I worked together for the whole time he was on board ship. Now, I guess I was in every engagement that the ship was in from 1943 on. I believe that even at the time I was at Catlin, the ship was either in Pearl or not engaged in combat. I know you've got a lot of things chronologically there. My role in almost every case was in handling the raids coming in, assigning raids to our men so that we could follow the raids and know exactly where they were, and piping that information up to the Captain over one set of phones that I would have.

On the other set of phones I would be in touch with the other fighter directors of the force that we were with--they may be carrier fighter directors or battleship fighter directors or cruiser fighter directors--for a complete exchange of information as to where or why.

In particular I remember one incident that took place with the bombing of the FRANKLIN, which was our biggest and newest carrier, during an air raid. If you recall, she had a tremendous loss of personnel and officers. We were the only ship that had this bogey coming in. All the other ships had nothing but friendlies returning to the carriers. We were in a carrier group at that time. I called the FRANKLIN and told them that I had a bogey on a raid returning in about seventy miles away. I showed a bogey-and I heard no other reports of a bogey and could they confirm that. The fighter director there questioned a lot of the other ships, and nobody had a bogey. It was a freak of the radar, because it was a well-known trick of the Japanese-. They would slip

-11

a plane in somewhere with a returning group, that doesn't mean right in the middle of them where they could be visually seen but close enough so that the returning group appearing on the radar scope showed nothing but IFF, friendly. When you have a plane that doesn't have his IFF on, he would show he was a bogey until identified; and once identified he was a bandit, which meant that we knew that he was definitely Japanese. Being a bogey, we were supposed to take necessary steps to consider him a bandit until he was identified as a friendly, because sometimes the IFF's didn't work. They were the little things that sent out signals to the radar showing that they were friendly planes. I had incoming coming in at seventy miles, I had them coming in at sixty miles, I had them coming in at fifty miles; and at that time we were in Condition Yellow, which is not necessarily at full General Quarters. We had been having raid after raid for hours, and we would go to General Quarters as soon as a raid developed so we knew that enemy planes were coming in. All of us had been at General Quarters for hours. As soon as there is a little action that the enemy doesn't seem to be moving towards us in any way, we let one part of the ship go for food or rest while the guns are manned by a limited crew. That is what was happening on the FRANKLIN, and I kept insisting to them that I had a bogey and that it was a freak because nobody else had it in the whole darned group. I never could understand why they didn't go to GQ. I couldn't tell them to go to GQ. You need the Captain to tell them to go to GQ; but at any rate that bogey came in, and we lost him at about twenty miles. I was increasing my urgency, my tempo and my voice and everything else at that point, and the next second the thing went up in a tremendous explosion. I'm positive that the fighter director was killed. It was a direct hit, and she caught on fire from one end to the other. She lost hundreds of men. It was absolutely terrible.

-12

I saw it all developing on my air plot. You see what happens is that if my radar man tells me that eighty or ninety miles out, which was about the furthest we could see anything on the radar to tell us that the enemy was coming, there was an enemy plane, I would assign to the plotters that that is Raid One maybe coming in from directly 000. Another radar man would say that he had enemy blips or bandits or that he had strange blips at 270, that's Raid Two. Every time the sweep comes around, it's at a certain angle and maybe 000 there. The next time it goes around, it may be 010, and the next time it comes around it may be 050. So you know he's moving in a certain direction. Then he was ninety miles away and by the time it comes around three times, it may be eighty-five miles away. You can determine his speed, and you can also try to determine his height. But that is Raid One; and as a fighter director, I've got to control each raid all at the same time. You get your information, and it's put on air plot. You've got one plotter who is just taking this one, and he's got ear phones on and is in contact with the radar man who is working on the radar scope. As he swings around he says, "Raid One at such and such a distance, such and such an angle." He marks it down, and then within three to five minutes I can tell exactly where he is going, how fast he is going, and when he is going to be expected if he doesn't change course. The idea is when you have a combat air patrol protecting you up above, you have to give a vector and a direction to the pilots. Somebody coming in from here like this; and we're over here, you've got to try to intercept him at the furtherest point from the ships. So you give him a cut off place where you think he will probably hit them, maybe at forty or fifty miles he'll be able to see him. He's got to sight him visually because he didn't have the radar. All he has is the vector and the direction. It's like a football field. You've got a safety man, and you're at the goal line.

-13

These people are coming down at you like that, and you want to always keep your safety man between the fellow who's going through the line to intercept him before he gets to the goal. That's exactly the way you work your combat air patrol. As soon as he sights him visually, he yells "Tally ho" and that means he sees them. Then he's that fighter's baby. We can't do anything because it's all mixed up then. It's all one blob. The little blips all become one thing where they are running all around.

(What did you experience when the FRANKLIN was hit?)

I ran out to look.

(Could you actually hear it?)

I don't remember. I doubt very much that I could have heard it, because they were probably one or two thousand yards off from us. But she did pass very close to us because our men were throwing life jackets, life rings, anything that floated over in the water, because there were so many men going in.

(Were any of the anti-aircraft guns shooting at this bandit?)

Not really. We got him but not at that moment. Everybody was at General

Quarters or going to General Quarters immediately after that. You could see that smoke billowing. You couldn't see the ship, but we went past very close to her. I saw that visually because at that point I stepped out on the bridge. I was out of Combat Information to see it go past. I later learned that I had friends on that ship.

(In your position, didn't you have to deal with kamikazes?)

Not personally deal with them. I'll tell you an interesting story about that too. Remember that I told you that the officers of the GWIN were more or less kept as a group and assigned to new construction. Well, the new construction they got was a new destroyer called the TWIGGS. They had been

-14

stateside while we had been in the South Pacific all this time, except for a brief stay at Bremerton to be repaired. They rejoined us just in time for Okinawa. That was the first time I saw them again. When I say they rejoined us, they were in the same task group we were in. At Okinawa they were hit by five kamikazes with terrific loses. I don't know how many. The amazing thing was that if we had not been the youngest officers on that ship, we probably would have been there and wiped out by kamikazes at Okinawa. That happened very near where we were. Once again, at that point I was inside, and I didn't know that it was the TWIGGS. There were so damned many kamikazes, hundreds of them coming down. It seemed like every five minutes there were more and more and more. At Okinawa was the time the kamikazes really came out. That is a funny thread that ran all through that whole experience of being on the GWIN and what happened since then and how it crossed my path.

(How did you react to being inside during combat? Did you feel more secure or would you have rather been out where you could have observed what was going on? Or, did you give that any thought?}

No. I tell you, by the time I was through with combat in the short time

I was with the GWIN, I had four battle stars, a couple of ribbons, and certainly a hell of a lot of combat experience. I really became quite immune. I knew I had overcome any possibility of fear because there were times on the destroyer when we had torpedo bombs coming at us, we had machine guns going at us, and all that sort of stuff; and we just simply forgot about that. Was it more comfortable in the C.I.C.? I'd say probably yes, except that it got awful hot there. The fact that you had a half-inch or quarter-inch of steel between you and the open air didn't make much difference to you, because you knew dern well that if you had a direct or even a near hit, you would probably get hurt. Being inside required an absolute amount of concentration.

-15

You had to be alert constantly and you had to be all over the place. There is a little cartoon of me in The Showboat Book there with one phone up here, one phone down there, my earphones over here, and I'm shouting. It's a cartoon one of the men did. That's what fighter direction is like, because you are talking occasionally to the leader of this particular defensive array over here; you' re talking to all the other people on the other ships; and you've got to feed constant information up to the bridge. The Captain wants to know what's going on. We're his Combat Information Center. We have to tell him what's developing. He gets it from a lot of sources, from different angles on different parts of the ship, and he hears a lot of things because he's got speakers going on the bridge too. The fact is that you are concentrating, and the adrenalin is running like mad when you are running in combat at that moment. It's exciting, and you just have to be so damned alert. If you make a big, whopping error you are going to have trouble. It was a great ship to be on.

(What about the NORTH CAROLINA and its officers and crew?)

It really was a great ship to be on. There's no doubt about that in my mind. The officers were very friendly. I had five different Captains on that ship. I lasted through five Captains. They went on to different assignments. Certainly for physical comfort, it was a fine thing to be on too because, as I told you, I did suffer from seasickness. It's pretty tough to go into battle while being seasick, as I was on a destroyer. I never overcame that on a destroyer. I had green bile. I used to go to my battle position with a pail under my arm, because I couldn't keep anything down on my stomach.

(This was not a problem aboard a battleship?)

No. I had a headache very often when we went to sea on a battleship and I'd also get sleepy from time to time; but over the course of many months

-16

on a battleship, I overcame that completely to a point now when I neither get airsick or seasick as an older person; and I do a lot of sailing and a tremendous amount of flying. I've flown over two million miles in my business career. I can go through any kind of weather and it doesn't bother me much.

(Are there any particular incidents that you recall that relate to any of the crew that are either humorous or personal in nature.)

Well, I remember one incident. I remember one time we had a chief who had been in the Navy at least twenty years. I think he was the Chief Steward on board. We were in Pearl, and he was to go stateside the next day. Somehow or other he was on a bus in Pearl, and some drunken civilian got into a race problem with him. He told him to stand up and get to the back of the bus; and the chief, from the information I had at that time, told him not to bother him. He was a well-behaved chief and had been in the Navy a long time, and he had done nothing to have anybody called out for. Somehow they had a fight, right in the bus there. This guy leaned over and grabbed him and tried to pull him out of his seat. In the course of the fight this fellow was stabbed. I was involved in the court case because I had been assigned many times as a court recorder on the battleship. It was marvelous to see how everybody rallied around this chief and got enough witnesses and enough information together to get him off the island and off to the states. He had been charged; and a fair, quick trial was held.

Just an amusing little incident, another time one of my men was Nicky

Hilton who was seventeen years old at that time. He tried very hard to be accepted by the men. He was stationed aboard the NORTH CAROLINA, and I was his superior officer. I didn't know who Nicky Hilton was. I hadn't the slightest idea. All I knew was that he was Conrad Hilton, Jr. But he seemed like a fairly educated boy. There were a lot of fellows in the group who were

-17

not educated. His way to try to be accepted by everybody was to use four letter words, every other word in every sentence was a four letter word. I called him down to my cabin once after listening to him all the time because I just felt it was out of place for him. I had a long talk with him and explained to him that you didn't become salty just by using four letter words. You would be better accepted by everybody if you just remained just absolutely normal in your speech. He tried it for a week or so, and it worked. Years later I was amused to see that he married Elizabeth Taylor. He was her first husband. I guess several other girls after. Nevertheless I said to myself after reading that, "I wonder if I had anything to do with developing his pattern of speech for the rest of the war."

I can't associate myself with a lot of incidents that were amusing, because all of these other fellows will tell you their amusing incidents in which they were participants, which I witnessed; but I rather they try to tell you that part of the incidents.

I can tell you a thread that goes through everything too, a really funny thing. I am the chairman of the Corporate Participation Division of the

United States Olympic Committee. There was a time that Ben Blee and I went ashore as two young bachelors in Hawaii, and we met a couple of WAVE officers and spent a fun day with them. We actually picked them up at a club or on the street. They were attractive enough; and we knew no girls in particular there; so we met them. We spent a fun day with them, doing a lot of things, going out to pineapple plantations. One of the things I recall is that we slid down the sides of the hill on tea leaves. That was a popular Hawaiian past time. The tea leaves were huge, shiny leaves, even larger than an elephant's ear; and they had a long stem. You sat on it and held the long stem and went down a hill at forty or fifty miles an hour. It was a pretty

-18

fast thing. Well, we did that and we did several other joyful things. It was a time when they had curfew at Pearl. We sort of overstayed our time. It was no problem for us, but the girls had to get off the street. We had a jeep, and we put them up at the Naniloa Hotel there, and we returned to the ship.

About four years ago, the man who is the Director of Communications of the United States Olympic Committee called me on the telephone. It was a man I had known for twenty-five years. I had been all over the country and many places in the world with him. I'd say he was a pretty close friend. He lived in Philadelphia and commuted to New York. I live in Connecticut and commute to New York. He called me and said, "Ralph, how rich are you?" I said, "Not very. Why?" He told me he was about to blackmail me; and I asked him what he meant. He replied that he had a picture of a young naval officer with his arm around a young female naval officer in what looked like Hawaii. It had a lot of palms and pineapple plants and other things around, plus another couple. I was thunderstruck. I didn't know what he was talking about. I asked him who the naval officer was, and he said it was me. I couldn't understand how he would_ have a picture of me in the Navy. I hadn't been in touch with the Navy or anything for years. I don't think I have more than three or four old Navy pictures of me. At that particular time, I had just become the chairman of that division; and he being Director of Communications, sends out publicity. I thought perhaps that he called my wife, and she pulled out some old Navy picture. Why, I couldn't figure out; but I couldn't understand any reason why he would have a Navy picture of me. I asked him who the young female naval officer was, and he said it was his wife. I knew this fellow for twenty-five years, and I had never met his wife. I had been with him as a friend; but we never knew each other socially because he lived one hundred and ten miles away from me; and our paths never crossed that way. When Ben

-19

got in touch with me to come down here, he wrote in his letter, "Wonder what ever happened to those cute bimboes we met?" Well, I told him what happened to one of them.

(Is there anything else you can think of?)

You know, it's very difficult to just pinpoint because I haven't been telling naval stories for years. Those things stay with you when they are repeated. The thing that always impressed me was this thread that seemed to run through--these coincidences. But it was an active, active time. You, of course, remember all the nice things that happened. I think human beings are built that way, and you more or less forget the painful periods or the disheartening periods. There weren't too many of those actually, because there were enough friendships on the ship, and enough things to keep you busy. Not that you didn't miss home. You missed home all the time, but you had something to occupy yourself and make it less intense.

I had a steward, and we were on some atoll, a completely uninhabited island. You know the atolls are a series of land spots like a necklace chain. For excitement we would look for sea shells more than anything else. This steward was in this shore party that I was with at that moment. I was looking for seashells. He was perhaps ten yards from me, near the edge of the water, where if you took a running jump you would hit the next part of the island. Probably six feet of race went through there. I was picking up shells, and I was talking out loud to him; and I suddenly became aware that he wasn't replying. I turned around and he had disappeared, just absolutely vanished from the earth. For a while I thought that he had stepped into the water sucked under and just disappeared. He never reappeared. We lost him

-20

completely. We searched for him and we went all over the place. He just drowned, we think. You know I would have stepped into that water myself probably in another five minutes or so unless I was impulsive enough to jump; but I probably would have waded. That's probably what he did. He stepped into it and went right down. It was a complete race right through there, a tremendous tide; and you couldn't tell. It was a rip tide right through the thing. I never heard him go; I never heard him disappear. I just became aware of the fact that he was no longer there when I was talking to him.