[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

April 20, 1977

U. S. S. NORTH CAROLINA BANQUET COMMENTS

Moderator: Capt. Ben W. Blee (comments. in parentheses)

Bob Celustka:

I liked everything in his speech except that short jazz. That is five feet eight. Before I start, I'd like to say one word. Thank you Brooke and Mrs. Brooke Jennings. Thanks to Ben. Thanks to Lou Behr and his cubs and to the other members of the commission for inviting me down. I've enjoyed it, and I wish you well in your tremendous project. It's going to be a tough one. I wish you total success in your tremendous project, and I think you all agree.

And now, "Take Six". It was in the Chesapeake Bay, 1941; the Skipper was Oscar Badger, who is a fire-eater and a flame thrower and a showman. We were down there, and I was on watch as always. I think I was permanently on watch. The Chesapeake Bay, degaussing and depurming, a routine afternoon watch. That's running through the gate, killing the engines, and all that jazz. Well, Badger was a fire-eater, as I have already said. So we're down there. However there's one hazard, about one hundred merchant ships crouched around to go through with us. We're the only battleship. Well, the idea was to kill the engines, coast through on a now northerly or southerly course, and take the readings on the ship for the degaussing and depurming. Well, no problem. However as we started our first run, killed the engines and started in, I leap out. Here was a merchant ship to starboard; and we were going to join at the gate. So I leaped onto the bridge and said to the Skipper, "I think we're being embarrassed to starboard." He leaped out and took one look and leaped in and ordered emergency full back; it screwed up the whole drive.

-2

After we get reoriented coming in south to north, going now north to south, I thought, "Boy, the afternoon watch is shot." So we started another run. No problem, except as we approached the gate and killed the engines, here I look out to port and see another ship _on constant bearing. I didn't want to tell the old man because he was an OD eater. So I went in and said, "Skipper, I think we're being embarrassed to port." He leaped out there and leaped back inside; and of course, as you all know, the whistle, four blasts, is the danger signal. Well Badger leaped into there, grabbed the whistle which had a brass shiny end; and he grabbed this thing and went boop, boop, boop; and on the third boop, down he went. He was on the deck. His hand slipped off. I reached over and pulled the fourth boop and then looked at Badger, who was down on the deck. His cap flew over to the left side, to the port. Then I went over and picked him up. Strangely enough, he had turned purple. He really had, he had turned purple; and I was so scared at this point that I wouldn't dare give him his cap. I put it on the chart board. At this point he turned around and shrieked to the signal officer who was on his port hip all the time anyway with the signal board. He said, "Take a message to the range officer." He said, "It seems to me that a seventy million dollar battleship should have precedence over these spit kits, you s.o.b."

Well, I was up there on a routine watch which was blasted. So we waited and back came a message from the range officer in about two minutes. It said, The NORTH CAROLINA has precedence. You should have no trouble in the future." You know that guy was right, for the next three years, until that damned Jap zapped us. It's true, and I thank you. I'm glad I'm here.

(I didn't really introduce Bob. Bob put her in commission. So he was there from the very beginning, and he served in her about three years, I think. The reason he's here, aside from the colorful character you've perceived already,

-3

is that he was the officer of the deck the day the ship was torpedoed. Now I'm not trying to suggest anything that reflects unfairly upon Bob. It could have happened to any of us, but that is the role he takes in our movie. Now let me go down to my left. We have nine members of the ship's company who take a part in our film and introduce various episodes. I think you all understand that the main idea there is that the first person eyewitness to something, particularly in a motion picture, can contribute authority to what we're trying to put across. That's the principle we're working with here. That's why all these fellows are here.

When we got to Iwo Jima where the ship bombarded in support of the Marine landings, not that that was the only one of that sort of thing but by far the most important, we felt that it would be desirable for a change of pace and to help put some variety in the film to ask a Marine who made the landing at Iwo Jima to give a few ideas about it from his different perspective. So I turned instantly from the very start to my good friend "States Rights" Jones, who was a Marine officer in the Fifth Division and made the assault landing on D-day there in a tank. He was in a tank battalion. He went inland from the center of the beach and then turned right and went north. We didn't support his battalion directly, but we did support the right flank of the landing and the movement to the north. So "States Rights" is in the film to talk about that, and it's my pleasure now to introduce "States Rights" Jones.)

Accustomed as I am to being so outnumbered, I'm sure happy to be here.

I'm really delighted to be with you, Ben; and I appreciate your confidence in what I might be able to do as far as your film is concerned. The remark about what we were supposed to do tonight, mine is authentic. I can quote you names and dates and places on it. So it's really not a lie.

-4

My story concerns four young Marines that were on Iwo during the invasion-a corporal and three privates. That was before we had lance corporals. They were PFC's and privates. At any rate, these four young chaps were crewmen on an amtrac ; and for the ladies, particularly, and maybe some of the other folks here, an amtrac is the Marine Corps contribution to amphibious warfare in the form of an amphibian vehicle. It's a huge chunk of heavy metal that manages to float and propel itself through the water with its tracks. It also does the same thing on land, and it goes inland. Therefore it~ an amphibian vehicle. But these four chaps were crewmen on an amtrac. Their job was to go back to an LST which was offshore, load up with ammunition and rations, take it into the beach, then on up to where ever the troops were, and then unload it.

This is what they did, day in and day out.

This incident occurred about D plus eight or nine, somewhere in that area. Late in the afternoon, after they had dumped many loads on the beach, they came back out to their LST and tried to go aboard; but by that time, the weather had changed a bit and the waters were quite rough. The LST skipper refused to let them come aboard. He would not lower his bow ramp, and the boys were a little bit unnerved by this. So he told them to go to another LST off the starboard bow so many yards. So they went off to another LST. They got to this LST, and the skipper gave them the same story. He told them that they couldn't come aboard because the water was too rough. He said he couldn't let his bow ramp down and take them aboard. But at least he was a little bit more cooperative with them, and he told them to get to the beach and to stay there until the weather cleared up. This was about 4:30 or 5:00 o'clock in the afternoon, and they headed for the beach. Unfortunately, they didn't make it.

They gave out of fuel about half way to the beach. At that time, apparently, there was a tremendous offshore current off of Iwo; and to: make a long story

-5

short, forty-eight hours later and thirty-six miles east of Iwo Jima, they were picked up in their amtrac by a destroyer. It threw them a line, and they rode their amtrac behind the destroyer on back to Iwo. They located their LST, and he turned them loose. There they were next to their LST and they came alongside and of course there were great greetings from their fellow crewmen and from the LST skipper who had denied them coming aboard about two days before. They got off the amtrac; and as the last Marine's foot left the amtrac, it silently went to the bottom.

(We turn now to John Kirkpatrick who lives out in Oklahoma City. He was a plank owner. He put the NORTH CAROLINA in commission in 1941. He began as the Fifth Division officer and then eventually served as the air defense officer; and it's in that capacity we have him in our film. He will be way up in sky control, as high as you can get in that ship, just about. Along with Larry Resen, who we'll come to later, he introduces the episode about the first battle the NORTH CAROLINA was in. So it's my pleasure to introduce John Kirkpatrick.}

There is one gentleman that had a great deal of influence on the NORTH

CAROLINA whose name I have not heard mentioned in our conversations, and that is our first executive officer. We learned two things from him--one was objectivity and the other was democracy. First I had a sailor in my division up at the mast. I believe that he won. Anyway he had a terrible black eye. He had been in a fight over in Brooklyn. Commander Shepard told him to explain that. He said, "I was in a fight and got hit." "Did you win the fight?" He said, "No, I got the hell beat out of me." He said, "After this, if you get in a fight, you win it."

The second was that we had a meeting in the ward room. This was where we learned about democracy, the way I learned about it, somebody sent me a cartoon that said "if you would be interested in the opinion of fifty-one percent

-6

of the ownership, I would like to say a word." But there was some problem that came up, and he thought he would get all the officers together in the ward room and vote on it. There were a hundred officers in there. Corky Ward and I voted "yes!'-along with the Commander, and there were ninety-seven votes "no." And he said the "yeses" have it.

(We have two former members of our ship's company who have come all the way from the West Coast and Bob here is one and the other is Dick Walker, who came all the way from San Francisco. Dick was in the battleship in most of 1943, roughly, give or take a few months. He had the Fourth Division, which was the automatic weapons in the ship. His battle station was up in sky control. So, it is my pleasure to introduce that fellow.)

Thank you, Ben. Ladies and gentlemen, when Ben introduced this thing a minute ago, he talked about the hoi poloi. I came to the NORTH CAROLINA after a stretch of duty on DD-66, which at that time was the oldest destroyer on active duty. She was four stacker with a broken deck. She predated the flush deck of World War I, so you know where I am. I was the assistant gunnery officer; and our training or our practice usually consisted of having somebody throw an orange crate over the bow; and we shot at it until it disappeared. And that was it. Then the day came when I was ordered to the NORTH CAROLINA, and I think there were more people who felt sorry for me than those who were glad for me when I got my send-off. By the book, by the numbers, you're important. I really didn't know what I was getting into, but I was willing to take a chance. I thought I knew my specialty, but there were a lot of things about the Navy I didn't know. So we started off; and the first few days aboard we were in Pearl Harbor patching up holes and scribing cams on the 40 millimeters and getting the twenty millimeters in shape.

-7

Then after a few days, we were led off to the island of Kahoolawe where we were going to hold a little gunnery practice~-both anti-aircraft as well as a little shore bombardment. It is, I would think, roughly one hundred and twenty miles out of Pearl Harbor; and we made that in jig time. In the old days on the island boat it took close to twelve to fourteen hours, and it took us less than five. We made it there and had a couple of runs with the sixteen inch guns, and they did pretty well on the island.

Then the gunnery officer called sky control and said it was our turn to call out the first drone. So from the Naval Air Station on Maui, the first drone came out and circled around and made a run. The five inch opened up on it; and in about thirty seconds, there was a bright yellow-orange flame; and it was in the water. So this threw everybody off. They weren't expecting anything like this to happen, so we had to wait about thirty to thirty-five minutes while they sent the second one out. It went into a maneuver and came down the side of the ship; and in just about the same length of time, the second one went down. And then the third one came, and it went down. Our skipper at that time was a fellow of considerable humor; and with tongue in check, he turned to the then gunnery officer who shall remain nameless and he said, "For Christ's sake, how in the hell are we going to train our people, if you're going to shoot these things down one after-another?"

He turned around and picked up the phone and he called sky control. He got my friend Don, and in words not becoming an officer and a gentleman, he just chewed him out from one end to the other because he had shot down three drones right in a row, much to the amusement of all the people on the Fire J-P system. Then when it was over, I said to Don, "For God's sake, I knew I was in for it; but what kind of a yard stick do you use for perfection on this ship?"

-8

(I think you are all beginning to get some idea of what kind of a ship this was. I want to turn next to the guy here who has had a longer period of service in connection with the battleship NORTH CAROLINA than any other person.

Clayton Price didn't put her in commission, but he almost did. I think he reported aboard about the next day; and he served to the end of 1944. Then in 1961 when she was brought here to Wilmington, he came to work for the ship again, and he worked in her crew right up until about this time last year. Now he's gone into the ministry. But in his service during the war on the battleship, he was a boatswain's mate in the Second Division. He often stood watches as a boatswains mate, both on the bridge underway or on the quarter deck in port. I have taken the liberty of asking him to bring his pipe along, and if it's not full of chewing gum and stuff, maybe see if it still works. So,

Clayton Price.)

I have three worship services a week, and in my worship service I have from seventy-five to a hundred people in my congregation. I was just sitting here thinking that I feel probably more honored and probably more humble standing before you people than I do standing before my congregation, because it's been so long since I've seen so many of you. It's been longer than most of us would like to think. During this time, I have had the opportunity to look at my life and to look back at what happened on the NORTH CAROLINA. I was one of the young ones. Like Paul, I spent my nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty first birthday aboard the U. S. S. NORTH CAROLINA. To me she is home. She is a part of me. She always will be, and I feel such an honor to be able to stand before Admiral Stryker, Admiral Kirkpatrick, Admiral Ward, and so many of you that I had the opportunity to serve under.

I remember one time, Paul probably remembers it too, that Admiral Stryker had passed the word that none of the boatswains' mates would make any mistakes

-9

when they were passing the word. If they did, he would relieve them immediately. Well, it got down to where we had about two boatswains mates standing watch. So myself and the other boatswains mate in the Second Division, when it came time for us to stand watch, we said, "Well, the Commander has relieved all of us but you and I, so now is a good time for us to not have a boatswains mate on the quarter deck." So when I went up on watch, the first thing I did was to push down all the buttons and passed the word throughout the ship for a working party. Very shortly thereafter here came the first lieutenant that Admiral Stryker had sent around. "Relieve that man. Get him off the quarter deck." I went below. So Bassanette, the other boatswains mate in the Second Division, followed me up. There was no one else. It had to be him. He did the same thing. He went up, all the switches went down throughout the ship. He was relieved. And when they turned around and looked for a boatswains mate, they had none. He had to release his order. Well, from then on he would allow us a mistake once in a while.

It is a pleasure to be here, and I thank God that I am able to be here.

There are two things that stand out in my mind, mostly I think, about the

NORTH CAROLINA. Of course, the one that stands out most is when we were torpedoed. The young man that got blown over the side was standing watch on the twenty millimeters. He had just relieved me a little bit before that. This was a rip-roaring Sunday as most of you can remember. He had just relieved me so that I could go down and write some letters and do some things that I needed to do. I was in the Second Division, and that's where the torpedo hit. I was in the after compartment of the Second Division, and the torpedo hit in the forward compartment of the Second Division which flooded our washrooms and head and killed one of our men that was in the Second Division at that time. I do remember that very clearly. I don't have any problem remembering that.

10-

The second thing I remember most about the NORTH CAROLINA was when I would be standing watch on the quarter deck and pipe the Captain aboard. For those of you who don't know how you pipe the Captain or an admiral aboard, you stand at the quarter deck with your side boys at attention. The Captain or whoever is coming out of the gig or the barge, whichever it may be, you wait until you can see the top of his head coming up the gangway from the deck, and you start to blow the pipe. You are supposed to cut it at the time he steps on deck. But what always happens is that he starts up the gangway, and you start to blow the pipe; he gets about halfway there, and he stops there and talks to somebody down in the barge. You are standing there and you are turning red in the face .

(I've already introduced John Kirkpatrick, and you have met him and heard him talk and know who he is. He was up in sky control when some of those things happened. But right at his elbow and helping him was a guy named Larry Resen. What's remarkable about Larry--well, there are a number of things that are remarkable about him. Let me tell you about what, he's doing right now. He is he publisher and editor of the Chemical Engineering Progress, the principal professional magazine of the chemical industry in our country. This is a great deal to his credit--a fine achievement. Back in those days, I don't know exactly how old Larry was and it doesn't really matter terribly, but he was a pretty young guy. Bob says he was thirteen, and he probably lied about his age; but he was a very young man. He was a petty officer and fighter control man. The remarkable thing is that he was put in charge in sky control of the starboard five-inch battery over several officers who had the directors on the starboard side. This means to me what it must have certainly meant to John at the time--that Larry had a lot on the ball and was quick and had good judgement. I don't know if I put you too much on the spot. They'll probably expect something awfully clever from you. But anyway you have the floor now.)

-11

Thank you. You are very kind, Ben. The job was just a living, you know. But I have one question I'd like to ask, and then I'll give you my anecdote. Lou, in your very excellent script, I didn't know who was officer of the deck when the fish hit; but I found out it was a fellow called Celustka. And I'd just like to ask him one question. Bob, if you had said "right rudder," maybe it wouldn't have hit.

Bob Celustka: The Captain did that. The Captain overruled me. He never knew which direction was port or starboard.

My little story has to do, not so much with combat; but Ben, I hate to tell you that I was a little younger than I am now. I was pink cheeked and had a lot of hair, believe it or not. The thing I remember most distinctly was the day we arrived at Pearl Harbor. You have to appreciate the context. All there was in Pearl Harbor was like about a foot of crude oil or a bunker of oil on top of the water, and there were all these broken battleships. We pulled in there, and we hadn't done a damned thing. We had just arrived, and here were all these sailors who had seen nothing but the desolation that the Japs had caused there. And they cheered us. I said to myself that they were cheering us for doing nothing; and I hate to admit, but I think I kind of wept a little. I hate to admit it too, but before I got to the hotel tonight, I drove over to the ship's berth. I didn't pay to go aboard. I'm on a tight budget here. But I did look at it and I have to admit I got a little misty eyed then too and I still am. I appreciate the opportunity to be here.

John Kirkpatrick: Ben, I'd like to say this little thing. When Larry was moved to sky control, he took the place of a lieutenant commander; and, there wasn't a single officer that ever complained to have this third class petty officer controlling that side of the ship. He did a splendid job of it. I believe it was just wonderful on the part, also, of our men that when we could

-12

see somebody who could really do the job, that we would put them in the spot; and whether you had one, two, three or five stripes didn't make a bit of difference

(I understand that John, and that's why we asked Larry to be here. I would like to now interject a little intermission into these proceedings and relate a thing that happened here last summer. The Battleship Association was meeting, as they do every year. About sixty or .eighty men and their wives and children come here and spend three or four days and go to the ship every day. The first day there was a caravan of cars, horns honking, signs on the side of the cars, "the Battleship NORTH CAROLINA crew" and all that, the police escort, and they go from Wilmington over to the ship. They arrived there about 1:30 in the afternoon, and there is a sort of welcoming ceremony in the stands; and then they go aboard the ship and begin their proceedings. But that particular day, there was a member of our former crew who didn't know that the Battleship Association was meeting here, and he was driving north on Highway 17 to go to something in Norfolk, some wedding or other. He's driving along and all of a sudden he sees that sign U. S. S. NORTH CAROLINA on Highway 17, and this was a surprise. He didn't even know that the NORTH CAROLINA had been preserved. How this could happen, I don't know; but he served on her in World War II. So he was going up the highway and he sees the sign, and he says, "Honey, there's my old ship. It's the Showboat'. How do you get off of this freeway? We've got to go on that ship. Oh my God, it's the old 'Showboat' over there." He finally finds a place and makes a U-turn. He gets in there and he goes in the parking lot. He arrived just as our caravan of former crew members had pulled up. He sees all of these signs and all of these sailors getting out of these cars. And he gets out of his car and starts walking toward the ship. His wife is trailing along behind him. "Oh my God honey, the crew is here. I must be going crazy."

-13

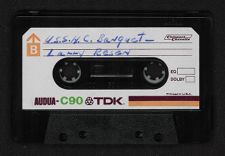

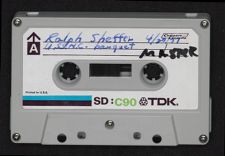

Back in 1943 there was a guy named Ralph Sheffer, who was serving in the destroyer GWIN, and she got sunk. I don't think it was Ralph's fault, but she got sunk in the Solomons in the battle of Kolombomgara. Ralph had to go swimming all of a sudden that night, but they fished him out soaking wet. In about three weeks he wound up in the crew of the battleship NORTH CAROLINA and served in her until after the end of the war. Ralph was my buddy, my best friend on the ship, and he was the fighter director officer in the Combat

Information Center. This means that he was the guy who talked on the radio to our fighter planes in the air and gave them their orders to send them out to intercept the incoming Jap planes, including the kamikazes. He was a crackerjack at that, and that is the role he plays in our film. Ralph Sheffer.)

Therein lies a tale. As a matter of fact, I had the rare honor today of taping this particular story that I am about to tell you. After we went through two tapes, I began to realize that it might be a little long, so I'm going to leave out all of the important points and just give you the facts. When the GWIN was sunk, there is an old Navy tradition that the survivors usually get thirty days survivor leave. That is exactly what happened to most of the officers above me who were given air transportation back to the states for survivor leave and then later were assigned to new construction. I didn't see them again until the end of the war. At any rate, one of the chaps on board the GWIN was Ensign Schiller, who happened to be my roommate at Officers Training School. Since our names were very close and we were assigned rooms and classes and berths, I guess, as a result of the alphabet, we were thrown into everything together. When we got sunk, I was the senior ensign. There were three of us on the GWIN at that time, and I was left with one hundred and seventy men to return to the states. My job was to get transportation for them.

-14

They put us up in a rest camp north of Noumea called Dumbea. It was a pretty rough type of rest camp, because it consisted of tents with dirt floors, wooden cots, and no electricity. The sun came up over one hill at about ten in the morning and it was blazing hot at noon and it went down at four o'clock in the afternoon. Then you groped around to see where you were most of the time. We finally got the men off, back to the states and arranged surface transportation for them. We had nothing to do for a moment. Fortunately, I had a jeep. Ensign Schiller asked me one day if he could borrow the jeep to go down to Noumea. And I said, "Sure, take it." At one o'clock in the morning he arrived back, and I heard him groping his way into our tent, and he was singing. The song he was singing was "I'm going home, I'm going home." This was the lowest point of my Naval career. I was lonesome; I was tired; I had been sunk. All I had on me at that point was a set of Marine fatigues that the Red Cross had given me with one cap. That song almost made me weep. I said to him, "What do you mean you're going home?" He said, "Well when I was down in Noumea, I met the reassignment officer of the South Pacific; and he told me that he had got orders for me to send me home." And I said, "What about me?" At that point he fell asleep. I shook him and I couldn't wake him up. So I waited until the next morning and I reminded Johnny when we woke up that I was still in the tent there and that he should let me know what had happened to me. He said, "Gee I'm awfully sorry, I simply forgot to talk to them about you." I made up my mind that I wasn't going to let him out of my sight until I found this reassignment officer.

About a week later, he asked me if he could borrow the jeep again.

I told him at that time that I had something to do down in Noumea and that I would be glad to drop him off. He said that was fine. We drove down to Noumea; and when we got there, he suddenly told me to stop, that he was getting off.

-15

So I let him off. I whizzed around the corner, parked the car, got back, and I saw him disappearing into a Quonset hut about a block away from me. I walked all the way up to that Quonset hut and there was a sign up there that said something like "Reassignment Officer, COMSUBPAC." And I said, "Boy he really did it." I walked into that Quonset hut, and there were about six or eight desks with yeomen working away at the typewriters. There was a screen door and an office in the rear part of the Quonset hut, and I siddled up to the side of that screen door and tried to listen to any conversation coming through it. I could hear some audible noise, but I couldn't tell what they were saying. Then the door swung open, and I ducked back to the side of it; and out came a lieutenant commander with his arm around John. Ah, I forgot one thing. John Schiller was a native of Wilmington, North Carolina. He was the Assistant District Attorney here before the war and had spent all this time with me. I heard him say to John, "Well John, we'll send you back to North Carolina." That's what I heard him say. So the lieutenant commander went back into the office there. John didn't see me, because I had ducked over to the side of the door. I waited until John got out of the office, whipped my cap off, put it under my arm, knocked on the door, walked in, and there was this lieutenant commander shuffling some papers. I stood at attention there, and he finally looked up and said, "Yes."

I said, "Ensign Sheffer, sir. I'm a survivor of the GWIN."

He said, "Oh, we just had one of your shipmates here."

I said, "Yes, I know."

He said, "What can I do for you?"

I said, "I'd like the same thing as Ensign Schiller."

So he looked down at his papers again and shuffled them around. He said, "Fine, we'll send you to North Carolina."

-16

I said, "But sir, my home is New York."

He said, "What do you mean home. I'm talking about the battleship U. S. S. NORTH CAROLINA. Do you want it or don't you?"

(I'm going to go back to Clayton Price now and ask him to get that pipe out and sound Sweepers or something.)

I'd like to say something about this pipe. Most of you remember Chief

Boatswains Mate Dillingham. Dillingham gave me this when I made coxswain.

Coxswain used to be what they now call boatswains mate third class. I have treasured it all these years. Paul maybe you can do better with this than I can. This is something you have to keep in practice with.

(I want to tell you a little bit about this fellow over there. Paul Wieser was also a member of the ship's company. He almost put her in commission, and he almost put her out of commission. He reported very soon after the ship was commissioned and served in her until 1946 for a period of about five years, which took him through the entire war. Today Paul lives in Linden, New Jersey, where he is in the fire department. I don't think anybody loves this old battleship of ours more than that guy. Two or three times a year, he gets in his car and with a couple of pit stops and burning up a lot of gas, he comes down here and drives about five hundred and sixty-three miles each way. That's just to spend a few hours walking around the decks of our ship. That is how much Paul thinks about it. Paul is down here for the remainder of the week until Sunday, voluntarily, because he wants to help us to do this job. Paul it's great to have you here.)

It was a real pleasure and an honor to serve on this ship, to serve all the officers. It was really a topnotch ship. I didn't know too many ships, but this one--it just gets you. I was recalled for Korea, and I was on an aircraft carrier, and my training on the NORTH CAROLINA proved it very well.

-17

I was first class, and the boatswain called me and told me to relieve the chief of the gangway. He wasn't doing a good job. My training on NORTH CAROLINA carried me through.

There are many stories about topside. We could go on for days and days talking about them, combat, fueling, but there is one I want to tell Admiral Stryker. He was with me. He probably doesn't remember it. Our chief boatswain went over into the jungle. He was going to do some hunting. Do you start to recall it now? He was dragging his gun or something behind him, and somehow he blew his three fingers off. I was called away. I was the coxswain of the gig and the number one motor whale boat. I was called away and made a gangway. Commander Stryker came out on the gangway and said, "Take me to the fleet landing." I think it was about the time you were going to be relieved and made Captain. All the crew always thought very well of you. I thought that this was my time to make an impression on him. I was going into that landing at four bells, at full speed. He didn't sit down. He was standing in the stern and was looking around at all the ships; and I'm closing in on the dock.

I'm really going in there. I said, "He's going to really get a landing." He turned around and looked at me, looked at the dock, and I was still at four bells. So the second time he turned around and looked at me and looked at the dock, and still I didn't do anything. So I think he was about to say something the third time. So I said, "Here they come, rip quick." I couldn't see my engineer. He was down inside behind a canopy. I went from four bells to one bell. He gave me one bell; he gave me a nine hundred revolution. As soon as he gave me that, I stopped the engine and coasted. I said, "Now give me back-down." At the dock was a fifty foot motor launch, sitting there bigger than day. So I give him three bells, and he's backing me down; and I said, "I know I ain't going to make it. What'll I do?" So I ring four bells and I feel the

-18

boat come out of gear. The engineer sticks his head up and says "What the hell do you want'?" Boom! I hit that fifty foot motor launch; and then it dawned on me. Admiral Stryker said to me, "Man, you know you couldn't have made that landing at that speed." But when the engineer stuck his head up out of the engine room, I knew what was wrong. I didn't have my regular engineer with me. I'd made that dock many times faster than that, without bells.

(Among the officers and men who served in our ship, a lot of them went a long way in many, many different fields; but in the Naval profession, none of them went quite as far as Admiral Ward. Back in 1941 when the battleship NORTH CAROLINA was commissioned and she was the pride of the fleet, because she was the finest and newest and most powerful warship in the world, they picked a guy to be the F-Division officer who knew something about fire control and gunnery. And you would imagine that they would pick the best man they could find; and they picked Corky Ward. He later became the gun boss of the ship. In our motion picture, he will have that role. Later in his career, he had the responsibility of being in command of the Second Fleet in the Atlantic at the time of the Cuban missile crisis and the blockade, which was a tremendous responsibility which he carried out absolutely first class. So that's Admiral

Ward. But before you get up sir, I want to give Brooke Jennings a chance to say something that he said to me he wanted to say.)

When I wrote you that little note, Ben, two or three things occurred in between. One of the things was Bob Celustka in talking about his height. It makes me think of Senator Tower of Texas who introduces himself--he's five feet four--he says, "My name is Tower. It's a misnomer." I get down to Clayton Price, and he talks about blowing his face red on these things. Many of you may not know it; but these funny old ideas of piping the side, goes back to the weight of officers. Up to lieutenant commander, you're not supposed to be

-19

a heavy weight, and you get two people to hoist you aboard the boatswains chair. Commanders and captains get a little bit better, it takes four sideboys to get you on board. After you get to flag rank, it takes at least six. And the boatswains call, as you know Clayton, goes right up. It's an ascending thing of hoist away. When the officer's head appears at the line of the ship, it's "avast heaving." That's the way the calls go.

But I'm thinking of Admiral Ward right now, and that's why I asked you this thing. Admiral Ward had a great distinction in the Navy in many ways. He was an officer of distinction in many areas and of a very considerable rank, but never in all his life did he have the rank with all his stars as he did with my class. When I was a plebe midshipman, Corky Ward was a first class midshipman, probably the highest rank he ever had

Admiral Ward: I have many thoughts this evening; and among them probably the most important is our fight against the Japanese during the war. Everyone that I know of .has contributed to the defeat of the Japanese. The program that you've given us today, that we've taken a look at, is terrific. I think it will add prestige to the "Showboat," the NORTH CAROLINA; and I am real pleased and proud to be a part of the program which you are giving. I have some other thoughts on this subject, and they come from the first time I was on the NORTH CAROLINA. We were in the New York shipyard, getting the ship ready to go to war. The people in the shipyard had the same feeling that I have and that I still have about the wonderful ship the NORTH CAROLINA. Every man on that crew in Brooklyn worked just as hard as they could to make it a going concern; and it had to be, because it was known that the Japanese were building up their fleet and that we were not quite as superior to the fleet of the Japanese at that time. It was only until we got some real power in our naval shipyard and their results and the big ships, and the NORTH

-20

CAROLINA was in the vanguard of this fight. I have a few remarks on some of the things that went on. My wife and I were invited to join in the commissioning ceremonies in New York City. It was a really electric and satisfying result. Nona had--I don't know whether its a privilege or prejudice--of having as a man to accompany her in Slapsy Maxy Rosenbloum. I had a real pretty little girl with me, Merle Oberon. I think that the ovation that ended the celebration in New York when the ship was commissioned was a tribute to a bunch of hard working people that our shipyards were. Our sailors and men were ready to go out and do whatever had to be done to win this war. And they did it. They really did it.

When we left the shipyard in New York, we had no radar. We had just everything that made a big battleship go that was not often all the way there. At any rate when we actually sailed from New York and went up to Casco Bay and we got radar on the ship, everything just fell into place. From then on, we had no major problems until we got out into the Pacific. We had a grand crew. We had the best crew that any ship has ever had. They had the finest young men in the high schools and the colleges. The college graduates were coming in and being recruited, and they were smart boys, and just brilliant guys. I was proud to be part of them and I'm sure you were. We in the NORTH CAROLINA had the greatest numbers of people who were brilliant, who were capable, who wanted to do their job for their nation, who were loyal Americans. I have never seen the spirit that has exceeded this period in our life as a nation, that happened during these dark days when it was evident that the

Japanese were going to come out and fight us. It was also evident, in my opinion, that with the great traditions of our country and with the abilities of our people, that there was only one solution that would be acceptable and that was to get victory against the Japanese.

-21

(Our next speaker was navigator of the NORTH CAROLINA during her final year of the war, from late 1944 to V-J day. I won't dwell long on his career, but it was a very successful one in the Navy. During that time and afterward, he's become quite a noted author of books about naval experiences, including one on the China station duty in the Navy in the Far East in the pre-war years. Then he wrote a book about his cruise and command of the Lanibai, a schooner that he took out of the Philippines after the Japanese invasion and had some hairy adventures getting out of there and away to, I think, Australia. But Kemp Tolley can tell you some great stories of his own, and I want to give him that chance now.)

First of all, let me say that if we had had Ben Blee as Secretary of State, we wouldn't have even needed the NORTH CAROLINA. You would have charmed the Japanese right out of the trees.

I don't suppose most of you knew that there was an isolation ward on the

NORTH CAROLINA; but there was, and it was the bridge. The two inmates of that isolation ward were Tolley and the Skipper, because we never went anywhere. We lived there. That was our home. I probably had fewer friends than anybody else on the ship because I never got any place else. Of course, the Skipper is known as the morale officer. That's the duty that comes after his name. I had my own private morale officer; and he was the mess attendent, a black boy by the name of Starling. He was so black, he was purple. You couldn't even see him when there was a blackout other than the two eyeballs and teeth when he was happy. He was happy most of the time, because he had been down in the magazines sniffing the stuff that comes out of the powder can. It was sort of an early version of glue sniffing. We were down there in general quarters, and he was up there on the ball of his feet. When he brought the chow up, he would have this huge pile of chow to eat. I'd say, "My God, Starling, I can't eat all that stuff."

-22

He would say, "Fat mans float better."

When we were about to bombard the Japanese coast for the first time, he came up with an extra big plate of ice cream. I said, "My God Starling, I can't eat all that."

He said, "Sir, after tonight, maybe you ain't going to get no more."

We had to make our own fun up there, and we had a big leather couch, which I am disappointed to say has disappeared. I got in league with the electrician's mate, and we wove a copper wire to the seat of it and put a spark coil underneath. I had a little switch under the desk I sat at; and people would come in and louse up the atmosphere. These smokers, you know, would be out on the bridge for four hours, and they just couldn't stand it. They couldn't wait to get down to their staterooms, so they would come in there and smoke. I don't smoke, and the place was all battened down with no fresh air. So I devised this scheme to get them on their way quickly. I didn't know it would work so well, because I would hit this switch, and they would get about four thousand volts through the seat of their pants. You know its strange, but you can fool lots of people, like Dr. Ziegler who said, "You know I've had some strange customers down here who said that they were getting sciatica."

I'm so sorry it wasn't there when I went back.

I wasn't married until I was thirty-five so I had a lot of girl friends around the world at one place or another; and I've gone back to some of these ports, and they are still there. They don't look quite the same; they are a little older. But when I went back aboard the NORTH CAROLINA, she was just as young and beautiful as she ever was. I spent yesterday walking around all by myself.

(It's hard for me to say the words that I want to say to introduce any of you guys, and especially in the case now before me. The crew refers to him

-23

as "Our Exec." When they say it, they say it with great respect and admiration; and all of them do. Every man that I have ever known that served in the battleship NORTH CAROLINA had nothing but respect and admiration for Joe Stryker. I don't think anybody contributed more to the character and spirit of the battleship NORTH CAROLINA than Joe Stryker, who I now give the floor to.)

I'm a little bit like Corky Ward. Since I've been sitting here this evening, I've had so many thoughts that I had to finally write down a few just to limit myself to this long. First of all I want to thank three men at this dinner. First Ben for the work he's done on this movie and the work that he's done to keep us going and the work that he's done to get us here is fantastic.

He told me the other day that he's been sleeping about six hours a night, and he hopes he's going to get back to a normal routine. I only have one bit of advice to you. It's what President Carter told to his staff. Get home and see your family once in a while. Go home and see Liz.

To the Battleship Commission which started this thing a long time ago, they've kept this thing going for us. Now every one of us here that served aboard this ship have part of the ship right in our body and spirit. I had an operation at Bethesda a short time ago, and they gave me a spinal. They said, "From your hips down, you're going to be dead. You are going to be living from here up." Every once in a while I think that from here up is the battleship NORTH CAROLINA. The rest of it, I don't give a damn about. It was so close to our hearts, and the Commission kept it going.

This man has been helping so much to keep the association going. I feel like so many of us are doing nothing but sending you a couple of bucks once in a while. I congratulate you and thank you for what you've done to keep us going.

-24

The only man that I don't know whether to thank or not is Lou, sitting over there. I had a fantastic experience going through this filming that we did, and I learned a lot. But he did something to me that I don't think I'll ever outgrow. I have not enjoyed television since I did this, because those buggers don't know their lines.

One little incident that I want to recall is that when we would come into port during the war in Honolulu or even on the west coast of the United States, we would try to put long distance calls in to our loved ones and our friends and our families. Sometimes it would take as long as five or six hours to get across the continent; and we would usually put these calls in at the officers' club where we could have a drink. We would put the call in and wait and wait and wait. Sometimes it would be hours before it went through. One night one of the young officers went up there to call the east coast, to ask a girl whether she would marry him. About midnight several of us left, and we had had enough to drink; and he was still sitting there, waiting for the call and having a drink. Next morning he came down to breakfast, and we asked him if he had got the call through. He said, "Yes." We said, "What did she say?" He said,

"I can't remember." Bobby, I've never had a chance to ask you. Did you ever marry that girl?

Bob Celustka: I'll tell you, no. She wouldn't marry me.

This guy offered me a tent and ten days leave in Noumea, Caledonia.

I was going with an army nurse. He said, "Take ten days leave, take the tent and go in the hills. Marry this girl." I said, "No, not until they all turn white."

Admiral Stryker: Let me tell you the insidious type that this man is.

You've seen and heard him all evening. We came down on the plane from Washington; and he saw this tottering old soul get on board that plane. He took my bag off

-25

the plane. He took it to the car. He drove me over here, and he's done nothing but take care of me. Well, I found out that he was sneaking up on me to try to pull something; and I've been watching him ever since I've been here. We left the ship the other day, and he knows that I'm a little bit blind and that like chocolate candy. So as we went over the gangway, he handed me this chocolate candy. He said, "Would you like a piece of candy'?" -So I put one in my mouth and bit it. I don't know how he knew that I had an extra pair of

dentures, but these things that he gave me for chocolate candy, are the plugs off the deck. So I'm watching him.

Celustka: I think he's a dirty liar. If I didn't love this guy~-.I'd kill him.

Stryker: I have one other subject that I have to go into, because this is the first time. I've ever been able to talk to officers of the NORTH CAROLINA before I joined the ship. This is a little prehistoric, but I have something that I want to straighten out with all of you people. I had command of a little mine sweeper called the RAVEN; and I was escorting the NORTH CAROLINA for several months before I was finally ordered to her. Escorting was not really the word, because I could make seventeen knots, and she could make twenty-seven~ So when we were going from Norfolk to New York, the Captain would give me a course, and then he would run circles around me so I could escort him. I did have a sonar so I could pick up enemy submarines and I had a five hundred pound depth charge on board, a couple of them. I hated to think of ever dropping the~, because they would have blown me out of the water as well as the submarine. One night we were coming south to Norfolk, and I got a submarine contact. I reported to the NORTH CAROLINA, and they said act independently. I turned on my running lights, and I headed to sea. Then on the next morning, I forgot all about it. About ten years later I was

-26

invited to a party given by the Class of 1942 at the Naval Academy that I had gotten to know very well. They were having a party at the Bethesda Officers Club, and they invited me and my wife to be guests. Ed Gallagher, who a lot of you remember, got up and made a talk, telling his class about the night that the NORTH CAROLINA was being escorted by the RAVEN, got a submarine contact, and the RAVEN very heroically turned on her running lights and headed to sea to draw the submarine away from the NORTH CAROLINA. I damn near fainted. I knew that the NORTH CAROLINA -had a big radar that wasn't worth a damn, a

CXAM. They couldn't pick up a ship to save their life. I thought that ship was going to be charging around there and wouldn't know where I was, so I turned on my lights so he wouldn't hit me. I just want to let you know that if you were on board then, people thought that I was ordered to that ship later on because I was such a hero--that I took the submarine away from them.

The only other thing that I would like to mention is that I came down here the first night that they put on the Sound and Light Show because I helped do the work on the thing in New York. They mentioned the ghosts of the ships named NORTH CAROLINA that they had seen steaming by at sea. I didn't think too much of it at the time, but as an afterthought I thought why the devil didn't they ever mention the ghosts of the men who served on board the ship-that made her such a fantastic ship that she was. As I go through that ship now I see old Dillingham down there once in a while, and I see Byron Phillips who are no longer with us; but I think of the ghosts, and I've always heard that a seagull is a spirit of a seaman that is no longer with us. The first time I came down here I went back in the stern, and I saw a lot of seagulls flying around the stern. I thought, "I wonder if those are some of the ghosts that we should have mentioned in the Sound and Light Show." So Brooke, I want to give some word to you as a request. For the ship keepers who are going

-27

to take care of that ship in the future, if I ever get to the point that I can't walk to that ship, and you see a big seagull upon battle two upon the splinter screen:;, tell them not to chase him away. Te11 them to throw him a fish and call him Joe.

(On behalf of our Battleship Commission, all of us here that are with the ship all the time, I want to thank our old shipmates for coming here and helping us with the film and being here tonight. It's a great pleasure to have you with us.)