[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

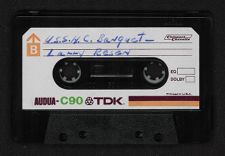

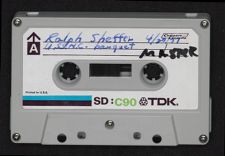

April 20, 1977

Larry Resen

U. S. S. NORTH CAROLINA

(If we can, just take it from your background, not only when you came aboard the NORTH CAROLINA but where you are from, how you came to be in the Navy, and your background before coming into the Navy and being assigned to the NORTH CAROLINA.)

My background isn't all that exciting. Actually as a youngster, I lived primarily in New Jersey. In the winter of 1941, in January, I had always been very interested in the Navy as a boy, and you could feel the trouble over in Europe that we were going to get involved sooner or later. In that January I enlisted with my parents consent. I just got in on the weight limit. It used to be one hundred and twenty pounds; and I was one hundred and twenty-two pounds. From there it was to boot camp up at Newport. The only thing about boot camp which may have had some bearing on my assignment, they had some sort of epidemic that caused my class to be held up about three or four extra weeks.

After boot leave I was immediately assigned to the NORTH CAROLINA which was at the Brooklyn Navy Yard at that time. It had been commissioned. I got aboard shortly after commissioning. The impression then when I was seventeen and not knowing much of what was going on in the world, the impression was that there were an awful lot of chipping irons. The welders were still working. Even then after commissioning there was a lot of work being done aboard the ship. The immediate assignment was selection for where you were going to be-what division. I had expressed an interest as an electricians mate because one of my uncles was an electrician. I remember Admiral Ward, who was then a

-2

lieutenant, and, I believe, Lieutenant Maxwell who was with the fire gang below--Maxwell said that if I wanted to be an electrician, be a striker below. Corky Ward said, "No, I think you'll get enough electricity if you become a fire control man. Why don't you go in F-Division."

That was a very important split in my career, if you want to call it that, because out of that I got to know Corky and John Kirkpatrick. In the early days aboard there wasn't much exciting as a second class seaman, which is just above an apprentice seaman, as you know. It was stocking provisions.

Finally the ship got under way. For the first time in your life, as a boy really, this is a very exhilarating experience. I had a unique battle station. In those days they used the visual range finder to guide the ship in and out of channels. There's something about seeing a ship like the NORTH CAROLINA going down the East River in New York City that the contrast is just staggering. Of course, it was the first of the new battleships, and literally all eyes and ships were on it as we went in and out. The shakedown period was relatively uneventful; but once again for a boy that had grown up primarily in the city to all of a sudden be steaming in the Gulf Stream and getting warmer and seeing Guantanamo; and we stopped in Jamaica once. The only recollection I have there that's not very important is that we slept out on topside. We dragged a blanket up there, it was so pleasant. Of course, they get these sudden tropical storms that you read about, and boy we learned about it the hard way.

Probably the strongest recollection which gets closer to the serious part of the story is December 7. I happened to live in Jersey City at that time. My mother was there, and I knew that I would be going out to sea sooner or later. One of the things I'm glad I did, I said to her, "Why don't we go to a movie in New York City?" Just before we left home, something came over the radio that

-3

there was a report from Pearl Harbor about the Japs. It was very garbled. It was the first announcement the nation had that there was some problem. The only thing that I recollected about Pearl Harbor then was that some fellow in boot camp said he was going to be assigned to a ship at Pearl Harbor. Literally, geographically speaking, it was a very vague place in my life. The movie ended, and we got out, and there was something electric in the air. People were walking faster, and people would look at me--I was in uniform-like they were glad I was there. Some people came up and told me that I should go back to my ship. And sure enough some Shore Patrol came up and told me that I would have to go back to my ship. I told them that I had my mother with me; and they told me to just get her to the bus, which I did; and then I took the subway over to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. I was walking down toward the ship, and all of a sudden there were two bayonets on the ends of rifles challenging me. What it amounted to was that we went on a war footing in literally a matter _of minutes.

All of a sudden the feverish activity on the ship stepped up. The next morning, which was December 8, there was a GQ; and they didn't know whether we were going to be bombed or not. I know that we manned our battle stations, and my battle station was a trainer on sky one which was the forward director for the five-inch battery. I didn't know much about guns then and I looked up and I said, "Gee, if we start shooting, we're going to knock off half the skyscrapers in New York. So, I'm glad no one decided to bomb the Brooklyn Navy Yard that day. We heard the Day of Infamy Speech. They put that on over the loud speaker.

Shortly thereafter, we went to sea again to accelerate our shakedown cruise. I was on mess detail; and for people who don't know about it, everybody that was new got about six or eight weeks on mess detail. Lieutenant

-4

Ward interceded and decided that we were more important to be on board and be on our battle stations at the director; so I had a short lived stint as a mess cook, which was probably the best blessing I got out of the fact that war was declared.

The next interesting experience was that we were assigned to operate out of Portland, Maine--Casco Bay. The situation was that the VON TIRPITZ was in the Norwegian fiords and the WASHINGTON was at Scapa Flow in Scotland with the British fleet, and we were kind of the backup. They felt that it would try to break out, and they wanted to have two new ships to attack it. We were up there about three months in the coldest part of the winter. My recollection there was that it was so cold in those directors where there was no insulation, only an inch and a half of steel, that one of those fellows who was on night watch there had his foot against the heater; and it was so cold he didn't realize that he had a burn. When morning came he had a very severe burn. He had to go down to sick bay. Unless you have been on a ship when it's cold, it's a hard thing to experience. That was the last time we were in cold waters.

Shortly thereafter they decided that the VON TIRPITZ wouldn't get into trouble in the North Atlantic and we were assigned to go to the Pacific. Here the tempo increased. The ship went through the Panama Canal. It almost took' the sides of the locks too. I guess it had a clearance on its beam of about one foot on either side. Unfortunately I was in sick bay half the time. I was taking sulfa drugs which make you half dizzy anyhow; and you would get up and you would be going through this jungle, and here would be all these big lizards on the banks and tropical vegetation and monkeys swinging from the branches. On some of these channels you would literally be only fifteen or twenty feet from the banks. It was an experience. It was a real change of pace from what we had been experiencing.

-5

We swung up to San Francisco for just a few days. Once again this was the first tangible evidence of a new ship coming out to help the Pacific Fleet. My recollection of San Francisco was that it was on a war footing and the embarkaderio where the ship went, they had an awful lot of soldiers on guard. You had to show passes when you went up town. I still haven't recovered from the experience of those cable cars. That was a wonderful experience. It was the first time I had ever been in California. The other thing I remember about San Francisco was that they had a structure there called Coit Tower, and the ship was docked just below it. You could get up in it, and it was the first time you could really get a good aerial view of the ship. It was most spectacular.

Then we got under way, out to Pearl Harbor. During this period we had intensive drills. You realize that the ship had never fired a shot in anger. We did have drones. I think the first drone was off the east coast. The thing that impressed me about that was that it kept on coming and never got shot down. Both the training and sophistication had improved over this period of time. As I said last night at the banquet, one of the things that moved me the most was entering Pearl Harbor. Even with all the movies and pictures you saw, you couldn't appreciate the devastation that had taken place there. When these other ships were there docking, the men there all they had really ever gotten was a very sharp kick in the teeth at Pearl Harbor, and all the ships that had been lost in between; when they cheered us, it just broke me up. We hadn't done anything. We were going to have a chance to do something.

We had a relatively short stay there and then headed down to the Pacific where the action was going to start taking place. I didn't know and I don't know how many people did know that Guadalcanal was going to be the invasion

-6

spot. We made one stop along the way there at an island called Tongatabu in the Tonga Islands. An interesting thing is that time passes on, and you don't realize what's happening. There were a whole bunch of fellows there in dungarees playing softball. We had had a shore leave, and I was over. I asked somebody what were those guys doing over there. They were the survivors from the LEXINGTON, which was sunk in the Coral Sea. I have since found that one of my neighbors was over there playing softball. He is a fellow I have since met, but it's funny how paths cross during the war or something such as that.

As I said, the stay there was very short; and all of a sudden, we were on

our way to the Guadalcanal invasion, which everyone who is acquainted with the Navy appreciates. This was the first time that the Japs were going to get their noses bloodied purposely. Before they were always the aggressor. One morning we got up to our battle stations, and here was the largest convoy I had ever seen in my life. We were part of a task group; and the NORTH CAROLINA'S job was to stay with the carriers. We were converging on the invasion force and we got very close. The two groups got together and then parted company. We got fairly close and could see the troops lining the rails. You could see that their feelings were that at least they were going to have some backup support, that it was not all going to be just the ground support or the close-in support they were going to get. Again, nobody knew really what was to come since it was the first of these invasions.

The morning of the invasion itself, we were at general quarters; and we could see the carrier group we were with and the planes taking off. A couple of planes apparently exploded on take off which, by the way, was a very sobering thought. Up until this time none of us aboard the ship had been up where people were getting hurt or killed during the war, so this was an experience. The

-7

invasion itself from our standpoint was very mild. We just steamed with the carriers; and they let off the flights, and then they landed. They were in an exhilarated mood. We were getting the reports in over our ear phones that the strike and landing was going well. In the beginning, of course, it did. Guadalcanal was a big frustration before it was all over; the immediacy of what was going on and how rough it was going to be I don't know whether it was the next day or the day after, but John Kirkpatrick told me that we had lost four cruisers. That was where we had lost three of ours and one Australian cruiser when the Japs came down the "slot." And if you stop to think that we didn't have that many cruisers in the whole Navy still afloat, and to lose four in one night was a most staggering blow. Savo Island was the name of it, and it was a turkey shoot for the Japs, because they came in very quickly and sooner than everyone expected.

The next recollection I have--you know time gets away from me now. I don't know if this was before the ENTERPRISE, the action of the Battle of the Solomons or afterwards when the SARATOGA got torpedoed. The next thing then was the battle of the Eastern Solomons; and we were at our battle stations, because they had a report about this task force sometime off and the bogeys coming. Our strike group had been sent off. At our battle station, John Kirkpatrick and myself up in sky control, was a rather confined walkway around the foremast there; so there was no place to stretch your legs or anything like that. You just stood at your battle station and hoped everything would work out. We were getting all these reports on radar about all these bogeys coming, and the radar was fairly elementary in those days. What would happen, the strike group from the Japs were coming in, and all of a sudden they would be lost. They would say, "No more bogeys on the screen.-" What was happening was that they were in one of these null areas. I remember looking at the

-8

ENTERPRISE and all of a sudden all hell broke loose. You could see the gunfire going up. I think I shouted, "ENTERPRISE under attack," or something. Meanwhile everyone else was shouting. And sure enough, you could see these dive bombers coming down on the ENTERPRISE. It was hit. I think they got a couple of bombs at the time. All of a sudden, the planes were coming our way and attacking us. I think it was just a matter of minutes. I think John said in his report that it was a total of about eight minutes of action. It's the old story about it being like an eternity. A couple of things stand out to me very clearly. One Jap plane went down the side of the ship. Again this was the first new battleship they had seen out there. He was just staring at it. I could see his eyes, and I could see his face; and he was just trying to get a fix. I think what he wanted to do was hope he would get away and report exactly what the ship looked like. He �was very close, close enough to see his face; and all of a sudden he got hit. I think one of the twenty millimeters got him. One of the older fellows, a chief, was manning one of the twenty millimeters up there.

By the way, speaking of the twenty millimeters, they had a very elementary sight early in the game. In the fire control group, one of the problems with this sight was to maintain a relatively constant temperature; and the insulation was cork. It was about an inch and a half thick. They improved it during the war. I remember a fellow by the name of Bruce Kelly, who was fire control man first class at the time; and they had to figure out how to repair this thing. It was like doing an operation. It was like getting a scalpel, an incision, and cutting a hole so you could get the insulation out to get to the little access port into the sight. I think a lot of people don't appreciate what was involved unless they appreciate the technology that went into the fire control system. I was merely a striker so I wasn't that conversant, but here

-9

were fellows who were responsible. If you had a problem at the navy yard the manufacturer would send a technician who knew everything about that particular element. Well here were these fire control men who in the Navy had to know everything about everything that was happening; and they kept this very sophisticated equipment running under very trying circumstances.

The other thing I remember about the action in the Battle of the Eastern

Solomons, my single contribution was that after it all happened, way off in the horizon there were some more planes. I looked at them in my glasses and the silhouette to me meant that they were torpedo bombers or TBS. I said over the JP-5 phone system that planes were out there on the horizon but to use caution before firing, because they looked like they might be our own returning; and they were. If in one little way I contributed to one of those not getting shot down by ourselves, I figured it was certainly worth it.

A little personal note here, not me personally, but one of the fellows from my division was manning a twenty millimeter gun on the rear deck, and a strafing bullet came along and hit the deck about six inches from his foot. We lost only one person. One fellow got strafed and killed in that action. He dug that thing out, and the ordnance people wanted to examine it. He said that he would lend it to them, but it was meant for him, and he was going to keep it. And I don't blame him.

The other thing, at that time we did not have these forty millimeter quads. We had the 1.1's, and the 1.1 was the diameter of the projectile.

The gunner's mates deserve Congressional Medals of Honor in my book, because many of them sat on the mount. It was an exposed mount much like the forty millimeters of today, with mallets hammering the breeches, because those things would jam. They would just hammer away. You didn't know if the thing would blow up in their face or not. Their job was to keep those guns working. You

-10

think of these individual acts of heroism that go unrecorded. Maybe this is what is good about this particular experience we're having now; that was their job. And I think that was the nice thing about the crew of the NORTH CAROLINA; a job was to be done, and they did it.

A very touching experience was when I saw my first shipmate buried at sea. Again it brings the war home a little closer to you. If I recall when I went aboard the NORTH CAROLINA, I was seventeen, so I had my eighteenth and nineteenth birthdays aboard there. So in a way I grew up with the ship and with some of these experiences.

The ENTERPRISE went back to Pearl Harbor to be repaired, and my next recollection of something happening was that I happened to be looking at the SARATOGA when it got hit by a torpedo. I literally saw it lift out of the water about five or six feet. If you stop to think of lifting something like that five or six feet, you can imagine the force that that torpedo must have had. It just seemed that there was a period about every week or two that something very serious was happening.

{What was your feeling when you saw a ship like the SARATOGA hit?)

Well, bag ass to your battle station. That's the instinct. You would have to go to where you belonged. You knew it was bad, but you knew that you had better get to where you belonged. I had a similar reaction, which is more detailed probably because this happened so suddenly; and then it was over. There was no fire to my recollection. At least I didn't see anything like that. It was dead in the water and then it started up again. It was damaged and had to go back to Pearl Harbor. If you stop to think, when we started out, we had four carriers total in the group, Then we lost the ENTERPRISE and then we lost the SARATOGA and the next one was going to be the WASP. That's three out of four in roughly four weeks time. It's just a staggering loss. They weren't lost, but they were out of commission.

-11

The recollection of how you react to something was this incident when we were torpedoed. I was back in the fire control shack, which was just like a little cabin. It was aft of the rear stack. I remember getting out of my bunk and looking out. A scout plane had just passed us and had been shot or damaged or something. I looked over, and I saw the WASP burning; and I knew I ought to start toward the battle station. They hadn't sounded GQ yet at this time. In the course of the standard operating procedures, you went forward on the starboard side and up and then you went aft and down on the port side. I happened to be on the port side of the ship; and as I was there, I saw this gigantic splash. What the splash was, was that a destroyer was hit. If you recall in the recollection of the Jap skipper, he got the WASP and a destroyer. He missed the HORNET, and then the next torpedo was for us. I was going forward on the port side; and again battle stations hadn't quite sounded, so I was correct you might say.

The torpedo hit, and I was all of a sudden engulfed with a lot of smoke and the smell of cordite. By the way, I wasn't on the main deck; I was on the boat deck, which was one deck higher. I paused and said, "Boy, I have to get to my battle station." I said to myself, "I'm going the wrong way; but, hell, if I go back, I'm going to have to go back too far." There was nobody else there, and then I thought that if I went forward I would be liable to fall into a hole, because obviously there was some damage being done. So finally I found a place that I could cross over and get up to my battle station. From there the only thing we could do was look at a beautiful ship being destroyed--the WASP. They were pushing the planes over, because the planes were armed and they didn't want them to blow up; and they would. Some of the most dramatic pictures of the war are of this billowing smoke from the WASP.

-12

To answer your question, the same reaction there was, "I have to get to my battle station. That's where I belong." We got up to a speed of twenty-five knots; and you could see an oil slick trailing; but we got out of there. The next day or so, we learned that the WASP had sunk. It had to sink. You knew it was. Then I found out that that was a destroyer, not a bomb, that had caused that geyser of water. I had thought that it was a bomb that went off that caused it.

One thing that disturbed me was that the four men who were trapped had to be taken out and buried. They had to be buried on an island. I didn't go over. in the burial party. The ship's company saw them over the side, and then a group went over. You know, war is impersonal. It's always someone else that's going to get it. On a ship as big as the NORTH CAROLINA there are so many people you don't know, and I didn't know these fellows. I knew the first fellow who had been strafed and was killed during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

From this point we headed back to Pearl Harbor; and the SOUTH DAKOTA, fortunately, was coming down into action. So in effect it was a replacement for us. The HORNET was there, and the SOUTH DAKOTA at that time. I said to somebody, "You know it's the hand of God, I guess, why some of us are still here." In effect, the SOUTH DAKOTA was where we should have been. It was like Clayton Price was saying last night about the fellow who came up to relieve him and was washed over the side when the torpedo hit.

(John Kirkpatrick: I'd like to make a point on that. We had very little sympathy for him, because we had raised hell with the gunners to keep the rope around their waists. We would tell him every damned time to keep a rope around him, but he got washed over because he was reluctant to do what he was told to do. We had a one-inch line passed between the men, but some of them didn't want to bother with it.}

-13

(Were you ever fearful that the NORTH CAROLINA was going to sink when she was hit?)

No. I never thought it would. If you look at it from this vantage point, you think it never would, and yet we were aware that right after the war started. . . . But right at the time it happened, it was listing; but we were moving so fast in getting out of there you felt kind of comfortable.

{John Kirkpatrick: I remember though that you saw all that steam coming up out of turret number two, and they reported that the magazines were on fire. I thought that the damned thing was going to blow sky high. We got scorches on our powder cans, and it didn't miss it by far.)

It wasn't until afterwards that I realized the implication if that sprinkler system hadn't been hit. I think the thing is that at the time any action is happening, everything is happening so fast, there were just certain things you can think about. The implication doesn't get through to you. I was at a lecture and heard about one of the valves being stopped up by a mattress that got sucked up into it, and there could have been a lot more severe flooding on the ship. The feeling or implication that it might go at the time didn't register. It was after the fact.

From then on, my career on the NORTH CAROLINA got to be a humdrum existence of going down to New Caledonia and then coming back up and then going back down. I guess the high spot then was when we carried Artie Shaw and his band down from Pearl Harbor to New Caledonia, and we got a free concert every night. Every evening when the destroyers would come alongside to refuel, they would really love it. He would get out there and play. From then on, it was just kind of a holding pattern, because the Marines were having a hell of a time on Guadalcanal. It was getting very frustrating, because you felt we weren't going anywhere; and yet there were so many more ships coming out and so much

-14

more reinforcements. Shortly thereafter, I was detached and came back to the states. My career, the action part, was terminated when we got the torpedo. I did not see any more action after that.

(When were you detached?)

I believe it was toward the end of 1943. I ended up on the MISSOURI and went back out. I saw the NORTH CAROLINA one more time when they were at the Ulithi Atoll. John Kirkpatrick had been detached, and I stopped by and saw him at Pearl Harbor. He was at Waianae Gunnery Range. I went out there, and there was no food. I remember we went out in the kitchen and tried to find something. I got an apple or something. I had taken the local bus, which wasn't much bus service. I visited with John a bit, and he gave me a bottle of scotch. I was a chief then. You're not supposed to bring bottles of whiskey aboard ship; but the Marines were very kind to chiefs, and nobody asked what was in the bag. I felt so good when I got it back aboard, I figured I would share it with the fellows in my division; which I did. They enjoyed real honest-to-goodness Scotch aboard the NORTH CAROLINA. I hope it's too-late for court martial or captains mast or something like that. John Kirkpatrick instigated it, so I was going to blame him.

Coincidentally there was Bruce Kelly who had been a fire control man, a range finder. That was his job before we had radar. We started out with optical range finding. He was given a commission, and he was on board a destroyer at the time; darned if he didn't give me a bottle. I was practically rumbling in there for a few weeks. Toward the end of 1943, I was detached; and my career with the NORTH CAROLINA ended then. I regard as the high point, if you want to call it that, in action was when we were torpedoed.

{Are there any other incidents or impressions of personnel that come to

mind?)

-15

My impression of officers--Corky Ward stood out especially strongly.

Corky, I didn't call him Corky then of course, was my division officer. If you had heard him talk in those days, he had a very strong and penetrating Southern accent; but it was very crisp. I was just a kid, and I would be doing something, and he would come up behind me and say, "Resen." And I would say, "Yes sir." It was always a very reasonable thing he had to say, but I always was put in a state of shock when he would do that. Corky was always somebody that I admired for his intelligence. He was probably one of the smartest persons I knew. He was a pleasure to have as division officer. The one thing that I appreciated was that he permitted me, in effect, to be detached from my division and serve with John Kirkpatrick in sky control.

Speaking of John Kirkpatrick, he's the other personality that stands out most strongly. John and I, our first battle station together was on sky one, a forward director. In addition to just being on a battle station, we stood many, many watches together. Of course I am indebted to him for taking me up to sky control which was an opportunity and a compliment to be up there with him. Some of the things that stand out, there were some fights aboard ship. The men were fighting among themselves, literally. One guy, a seaman first class hit a third class. That's not good. John asked me, "What do you think we ought to do'?"

I said, "Well, gee, you're going to have to throw the book at him."

He said, "No. This is something we haven't experienced. The men don't have anything to do." We were on four hours, off four hours, on four hours, and we were just steaming around. Once we steamed around in a big fat circle for over eighty days, and that's a long time. He said that what we had to do was to get them something to do so they would have something to do besides fighting. As a kid I thought that what you do with kids when they fight is to

-16

kick them in the ass, and that is supposed to straighten them out. With men you didn't want to destroy their morale, and you didn't want to have everybody up to mast. That to me was an interesting exercise in human relations.

(What did he find for them to do?)

We had drills. They also arranged for things like cribbage sets. This might not sound like much,; but the hours you sit there doing cribbage, you have someone you might have been fighting with otherwise, but here you are maintaining a communication with them. Any crew where you have over a couple of thousand men together, you have a wide diversity of interests.

(John Kirkpatrick: We started a lecture program over the battle circuits.

We would give lectures on the weather or some incident at sea or something to build up added interest. About each watch we would read some account or something of interest.)

I was going to get to that. Some of those watches were long, like from twelve to four. I remember we would have quiz� programs over the phone circuit. John would ask a question. It was like twenty questions or something like that. We had the gunner's mates in the gun mounts on there as well as the other directors that were manned. You had a little communication circuit there, and it was stimulating. It kept you awake for one thing. Another thing we would do, on the full moon, we would get out the range finders and zero in on the moon and hope you could see more of it. You could see it a little better of course with the magnification; but we had no idea somebody would be on there before too, too long.

A couple of other interesting recollection, during the battle of the

Eastern Solomons when we were being bombed, that one director officer aft-there was too much smoke for him to keep his head out. We had the daily problem of manning your battle station before sun-up. This is a preventive type of

-17

situation. What you wanted to do was to get up before they sounded general quarters. If you are trying to go up that foremast and everybody else is coming down, its kind of rough. A couple of times I had to go out the side way and climb up completely exposed because everybody else was coming down. It wasn't a pleasant experience, especially with any kind of a sea rolling. In a way that was kind of a pleasant time of the morning. You could see the sun rise. You would have a chance to visit. There was a degree of solitude up there too. We were talking about this at breakfast, and some people said that they would hate to be exposed because of the possibility of getting hit. We all agreed that that was probably the highlight of our battle station was that we could see what was going on. When the guns went off, we knew what they were shooting at. When the sun went up or came down or when we would change formation, we could see the other ships in action. A very small percentage of men in action got a chance to see what was going on. I think this was the thing about the battle station.

Of all the people aboard ship, John Kirkpatrick and I have maintained a friendship. I guess we've seen each other every year or two at least once since then; and that's a pleasant experience to have a friend or two out of the war that you still see and have a little bit in common with. The trouble is that everyone gets scattered and you lose a bond. Of course, this is true of any part of life as you move around. I guess that is about most of my recollections that are fairly pertinent to the meeting here.

(When you were selected to take control of the port anti-aircraft battery over some of the officers, was there any reaction to this from the officers?}

No. If it did, it escaped me. I wasn't aware of it. John may have been, but I think John said that no one did that.

-18

(John Kirkpatrick: He was directly under me, so it was considered that whatever he ordered was being ok'ed. What they wanted was effectiveness, and he was a very effective hand there. As long as he was doing a hell of a good job, and he did a hell of a good job, especially in action, there was never any suggestion of displeasure there. I knew him very well, and I've known very well over the years some of the officers who were the director officers; but they never even then or since indicated any dissatisfaction.)

(John Kirkpatrick; This was the first installation of this sort in the

Navy so we had the responsibility of developing all of the fire procedures, loading, stand by, and the whole sequence of orders. We were able to do that along with knowing the equipment. We had Kenneth Gould that I mentioned from Western Electric, who was really a genius in this area, who worked with us in sky control in helping to figure these things out. He could see how the wheels turned up there and the dials turned here and tell if there was something wrong in mount three or whatever it might be. I think he gave us all a wonderful opportunity to intimately know the equipment and develop the procedures which used to be rather tedious. We boiled them down to where there was practically no conversation. You would say, "Sky one, 1 4 0 20, commence firing, period." Or we wouldn't even say that. It was published and used pretty well throughout the fleet when later installations like that came into effect.

Along that same line, I guess one of our main difficulties was that so darned many people had to be doing the right thing at the right time. For example, if a loader was slow in one gun and fast on another, well that would just play hell with everything because your fuse is set when you take it out of the pot. What you call the time between when it's taken out of the pot and when it's actually fired is dead time. That's the spread between two

-19

to four or five seconds. That means that the plane will have that variation in its motion which is out of the range of your shells. So you have to drill the hell out of your loading crews; so that if your first loaders are inconsistent, that throws your whole system out of kilter. All the way from the handling rooms on through the whole system was a terrifically difficult job in training to get all those things coordinated at one time. You just can't be automatic. If a guy gets up out of a dead sleep or he's tired or if you're firing at a higher angle of elevation or if the ship is rolling a good bit, it just took an unlimited amount of training to get the whole pattern working together. That is really the difference between your modern systems and the old is that the human element has been removed from it to where you can take a plane with two hands and drop a projectile down a chimney twenty miles away. The training was one hell of a challenge.)

(Do you have any other thoughts or impressions?)

(Resen: No, I think that's about it. I can't add anything. I just wanted to confine it to the more significant happenings with the ship.)