| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #OH0031 | |

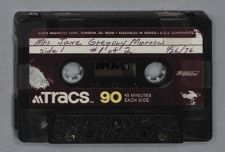

| Mrs. Jane Gregory Marrow | |

| Jan 26, 1976 |

Jane Gregory Marrow:

My father was Richard Henry Gregory, a farm boy born in 1876 in Granville County. He was the fourth or fifth child of eight surviving children out of ten, the fourth surviving and the fifth child. His parents lived in Granville County; they were farmers. I suppose this is where he got his knowledge of leaf tobacco that was to take him to China. His mother died early, when he was about thirteen. His formal schooling had been very casual and up to what I suppose our organized 6th grade would be. After the mother's death the family was pretty well split up, and he was sent first to one brother-in-law who operated a saw mill. As was customary the saw mill moved about and young men started often in that area working in lumber. The saw mill burned down while he was at a dance, and he was passed on to another brother in Warrenton, North Carolina. He had a general store and he and his younger brother George Gregory worked in the store and lived with the sister and Mr. Jackson, his old brother-in-law.

While in Warrenton he got to know Mr. George Allen, connected with American Tobacco Company. George Allen from Warrenton, North Carolina was later to be a director of American Tobacco Company and trustee of Duke University. Through him he had an opportunity to get out of selling seed and piece goods and to go to work for the tobacco company. The first few weeks was at a factory in Durham. Later he was in Rocky Mount where he married first Virginia Thorpe. After they had been moved to the export factory in Kinston, North Carolina, she who always was frail and from a consumptive family died. By that time he was in Kinston and without family except for scattered married brothers and sisters living everywhere from Virginia to South Carolina.

It was after the loss of his wife and the child she was carrying that he was offered a job by Mr. Allen his old Warrenton friend to go to China. His laughingly said later many times that he was either stupid enough or eager enough for a change, put it anyway you like, that he didn't inquire why the job became available. It was only months later after he had gotten to the Orient that he found out that his predecessor had died of smallpox. In 1904 he went to China, going first to the New York office, hitting New York City on Easter weekend and finding it for a country boy about the loneliest place he'd ever been. Downtown New York on Easter weekend was a pretty lonesome situation. He met Mr. Allen on Tuesday. The office was closed on Monday, Easter Monday. He was given his instructions and Mr. Thomas who was with the company, he and Mr. Thomas started out for Hankow, China. He travelled with Mr. Thomas. The small diary of that trip written in pencil, incomplete sentences, poor spelling, never intended for anybody's perusal except his own. That little notebook in pencil is in the collection at Duke. They made the trip to San Francisco, caught the boat and went to China. This was in 1904. The only unusual part of the trip was the delay in Japanese waters because at that time the Russo-Japanese war was on, and they couldn't get through on schedule, and so that's how I recall the date being 1904. The first marriage I think must have been around 1901. Anyway, that is how he got to China.

After Mr. Thomas left, he and one Chinese local individual, I do not know whether he was like a whole seller or office help, I don't know what the one Chinese's title and capacity was, but the two of them were the British-American Company in China. I don't know what instructions were given him, I've never heard him say what his purpose was in going. It worked out as the years went by that his job involved surveying the available farming areas to find out where the soil suitable for the growth for tobacco was most easily available on the basis of things like transportation to the coast and to the cities of distribution. We have a diary of a three months

wheelbarrow boat trip that he made quote "Up Country" surveying land to see what was suitable for growing tobacco such as could be satisfactorily made into cigarettes in North Carolina and Virginia. The purpose after the survey was to set up -- we called them compounds, but anyway -- the areas where men from tobacco growing areas of North Carolina and Virginia who went out later with the company under him could establish themselves, teach the farmers how to grow and cure and guarantee them purchase of the crop. In other words, they provided the seed, provided the instruction, and guaranteed purchase of the product. After that, with help from other people who were knowledgeable about those things, factories were set up and tobacco was processed and cigarettes were manufactured in the Orient.

I don't know if at any time the cigarettes were made out of 100% Oriental grown tobacco. This I doubt because in my later high school years it was necessary for him to make an annual trip to the tobacco markets of our United States Southland to look at the grades of tobacco and estimate how much American tobacco he would want sent out to China, exported. So my surmise is that never at any time was the tobacco made into cigarettes out there, out of entirely local grown tobacco. What the differences was, I wouldn't know. What it was what type I don't know enough about types and grades of tobacco to know what they grew out there and what they supplemented with from here, but it required on his part an annual journey from there to here. That was no mean feat when it took you three and a half weeks to make it, in order for him to cruise the Southern markets and instruct the buyers as to how much of each kind and grade that he would want for shipment to the Orient.

The first few years he evidently was based out of Hankow which is H-A-N-K-O-W, the city up the coast. I couldn't tell you how soon he started bringing out other men with him. But gradually other people knowledgeable in the actual leaf tobacco were brought from North

Carolina and some occasionally from Virginia were taken out there and were sent to these stations up country where they stayed for several months at a time then they would get a rest. We'd call it a rest and recreation now but anyway vacation down to the big city which was Shanghai was the one that was in the area that was suitable for tobacco. I suppose if the tobacco required a more tropical climate we would have been nearer Hong Kong. But the land up country from Shanghai was not too far different from some of our North Carolina farm land. What he was looking for on this first trip was where they had land that was suitable for growing tobacco. They were already growing tobacco there. He had pictures of some of it in his photographs of some of the native fashion of stringing tobacco for curing it in the sun, which is not our normal habit with barn curing; but he did not introduce tobacco. It was already there. It was already being used in some fashion for a smoking thing, but as far as cigarettes as we know them rolled up in a paper that was what was being introduced in his day.

I do not know when the other companies started coming out there. He was with what was known out there as British-American, and this as part originally of the American Tobacco Company here before the anti-trust split and I don't have my dates and my history in my head for that, but by the time we left there in 1930 there were several other tobacco companies functioning. Some of them were manufacturing and some of them just retailing. They were as a whole highly competitive I'm sure among themselves for the market and when at the office. But in their social lives most of the people out there involved with the leaf part of the tobacco industry, whether they were working with Imperial, China America, or British America, were largely from the same type of background over here from North Carolina and Virginia principally and from other Southern states. The families and their social lives naturally gravitated to each other and found that they had more in common with each other than they did with

Americans from other parts of the country or from Europeans. I wouldn't suggest that they were eventually clinging to each other, but there was no question of the fact that the rural Southern background of the tobacconist out there made them feel at home with each other. I would stress this rural background because most of the men that were asked to go out there to work were people who had known tobacco because they had grown it and worked with it as children on the farm and knew it in a way that you don't acquire as an adult. As the operations got bigger there were factory men and office force, sales force and people from a good many places, Britishers, for instance, in the whole operation people who didn't need to know how to grow tobacco. But when you were dealing with the product that the cigarette was involved in, most of the men that were out there were Southern rural background people. Some took to the life well and stayed out there. The usual pattern for the business people were four years with three months every four years to go "home" which meant the United States and shorter vacations in the summers. They were incomparable to the usual two to three week vacations that people have. You had those vacations plus every four years you had a trip back to the states.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were most of these businessmen married with families out there or were large numbers of them unmarried?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

At the same time there were both. In our household my father went out as a bachelor. I'd say most of them did go out their first tours as bachelors. This was probably encouraged by the "powers that be" because the first tours of duty for most of the agricultural agents you might call them was up country by themselves three months. It was not a place that they could satisfactorily take their wives. There was no place even for the men. The only recreation they had was what they did among themselves unless they liked to go horseback riding. There were no other Europeans for them to mix with except say the four or six of them that would be in an isolated

station. It's comparable to the isolated duty the military sometimes had. The wives when they came out were usually based in one of the cities, either Hankow or in Shanghai; and when their husbands had to go up country or go inland, they stayed put. I know that when they came out the bachelors many of them made our home headquarters you might say. I think mother was the aunt and mother surrogate and everything for a good many of them. I know my father's younger brother came out and was there for some years before he came back with a bride. They were encouraged to take at least one tour before they got married and brought a wife. Later when the community was larger and the company was bigger, there were more people needed in the city center. Some of them may have come out already married, but it was not an easy life in those early days for the women in terms of being away from home. Their husbands were often busy and away where they couldn't take them. There were very few other Americans for them to even relate to and not too many western Europeans that stayed. The coming and going changed a whole lot.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were not many British or Germans over there?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Right many British, yes, and there was a sizable German community until World War I. After World War I when China finally came in late I think it was and on the side of the Allies, the Germans faired very poorly in the international community. Mother had some German friends, and I wouldn't even be aware of that except that my mother herself lost a child that was buried out there and during the anti-German frenzy of World War I, a family of a friend of hers who had lost a child and was buried very close by about the same time. That family was a victim of the mass hysteria and anti everything and had to leave. They were forced to leave when the Germans lost their special privilege, and she always looked after that particular plot in the cemetery. I wouldn't even have known about that except for the Christmas and Easter care of the

plot of the cemetery of the child, a name which I didn't know who it was. And when I inquired, that's when I found out this was a friend who had had to leave and give up their home because of the mass frenzy that went along with anything German during World War I. As I always felt and the way she talked about it though, that particular German family was just about as uninvolved on the international level as any everyday family is. But they happened to be German nationals with a very German name, and they had to leave.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, outside of the war time the Germans really were not at any time very popular with the Chinese people, were they?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, that would be a hard thing for us to say because we weren't either. We were never a loved group. We were never welcome. The general term that was used the "Yang Kwei-Tze" that they talk about the foreign devil. It was amazing acceptance of the fact that you are living as an unwanted alien in a large group. We accepted that it was just a fact of life. It was supposed to prove by the way of observation that when you are sufficiently economically secure and self-sufficient and there are enough of you to support each other, you can have a right good life being unwelcome.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the Chinese never made any distinctions among the foreign devils as far as…

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I don't know whether they did or not. I couldn't tell you. We lived in a confused situation later after we came to Shanghai. After I could remember our final resting place, our final home was in the French concession which was a large residential area. This is because it was a residential area. The international settlement which was established after World War I with everybody participating except the Germans. Then the smartest move that the Americans made that they traded on very heavily is in not accepting any territory. They talk about that at great length but they failed to remember that while we didn't accept any actual territory we retained all

our extraterritorial rights of citizenship and court. We had the privileges without the responsibility of maintaining the settlement. We had as much status and special privilege as to courts and all and protection of our rights as any of the foreign nations without having an actual part in the settlement. We lived in the French concession. The French held theirs independently. The international settlement was everybody except the Germans after World War I and it included – I don't know when it ceased having the smaller groups.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, when did your father come back and meet your mother, after his first tour?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

No. He was out there and he came back after his first one in 1908. Then he came back in 1912 and my mother was the first cousin and best friend of his first wife. He had known the family. He married her in 1912 and took her on a brief honeymoon to Morehead City then off to Hankow.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was her name?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Her name was Harriet Burke Arrington.

Donald R. Lennon:

One of the Arrington's from Nash County?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Yes, her father was John Peter the sheriff in Nash County but they had moved to Raleigh. He had died and circumstances had not been favorable financially in the family, and she was living in Raleigh. Her mother and unmarried sisters, two of them. So they were in Raleigh at the same time. She had been born in Hilliardston and raised in Nashville and moved to Raleigh after her father's death. So she's not a native of Raleigh. Raleigh was some kind of small at the time she lived there. If I remember right there were about twenty-five hundred people. She was the – she wouldn't let me say secretary. At the same time she was married she was the stenographer for J. Y. Joyner, a Superintendent of Public Instruction during Aycock's time. She said it was a fascinating office to be sitting in because Aycock and Joyner and public education were just

moving and she was there when it was happening. But he married her in 1912 and they went to China. He had been out there eight years. She went out and didn't come back until 1916 when she came back with two children four years later. I get amazed at these people with their lack of adventures. Not many would have quite as much of the pioneer spirit you might say as my parents showed but they enjoyed living out there. She came back in 1916 with two children. Each time she came by father's business entitled them to a three months furlough, they called it. That's when your business people had more privileges than the missionaries who got one every seven years. I don't know how long, they may have gotten to stay a year every seventh year. Perhaps that would be worth it. But he would make one of the trips with us either coming or going and mother would stay a year of visiting which was never very satisfactory as near as I can tell for either her family or for her and certainly not for the children. A year is too long to visit anybody. But when you made your trip half way around the world you just didn't stay for overnight.

At the time my father first went out there to go back in 1904, going to the Orient was almost and I'm not being facetious almost as drastic as people going to the moon. The good-byes for the family were pretty drastic, and he had one nephew living in Rocky Mount that was named for him. He was born just after he was gone. His brother felt like he had the equivalent to a death in the family. I guess that's not too unusual but it was a big deal. A real big deal. Anyway, he went out and she went out in 1912 to Hankow and lived several years in Hankow. How long I'm not sure. I would have to depend on those letters that I haven't gone through. The first child was born in 1914 and then I was born in 1916 and then the first child died out there in 1918. One of the letters that I have read is interesting, not so much the letter, it's an account by her mother of the child's illness and death, but the fact that she wrote two copies and sent one across the

Pacific and one by way of England because of the German U-Boats. She was trying to be sure that the letter got through. In this day of telephone and rapid communication it is hard to think in terms of death messages taking three to four weeks. But at best if you caught the boat out there and mailed it on the night just before the boat left it would take three and a half weeks for a letter to get over to eastern North Carolina. This was true in 1930. Now how long it took in 1916, leaving out the War, I don't know. I do know that the boat trips were longer than they were in 1930. In the middle 1930's when I was in college and my father was still out there, I would have to count seven weeks for answers to questions. Even though at that time there were cables, we didn't cable anything unless it was very drastic.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now the time that you were born, were you living- you were not living in the French concession at that time?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Yes we were. By the time I came along in 1916 things had changed a great deal. We were living then in the French concession though not in the house that I can remember. I can only remember one home but we were at the French concession. The Hankow days were over. There was a big office in Shanghai. I couldn't tell you my father's position. I know that at the time he ended he was a local director. That is the director of the China branch of the British-American Tobacco Company. He was never a director of the whole British-American like his friend, William Morris, who was a director and sat on the big board in London. But he was director and in charge of the leaf department. He was always filled with this touch with the concrete material that the product was made of. His whole thing, as I tried to tell my children, all came from his knowledge of the land and the plant; not because of any great schooling or that but because he himself was a farm boy and he capitalized on what he knew. Anyway we were living in Shanghai in the French concession. In the first house the pictures of it are a duplex, a two story duplex and

on one half were the William Morrises. He was the man in charge of the entire Far East and the one that sat on the board of directors of British-American in London. On the other side was my father and his wife. The two of them and their wives shared a garden behind a high wall in a row of very comfortable looking city houses. We got a house all of our own with a yard that we lived in as long as we were there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Most of these yards did have rather high walls around them did they not?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

That's true. There are two things that were made for that. The Chinese culture called for walled enclosures. They were all aware of the myriad devils that were around, devils that couldn't turn corners and all streets had walls. Homes or groups of homes were in compounds walled in. The culture when you are afraid of evil spirits that travel in straight lines the solution is walls. When I say walls I'm talking about things that can't be seen through not just fences. Now later, when we lived in our own home a wire fence was all that separated us from the sidewalks. But, the point there was keeping people out rather than keeping evil spirits out.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the servants, the Chinese house servants that you had? Did they not fear this lack of wall?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, I don't know whether they did nor not. Each household usually had several servants and most of the servants were male. The cook, the butler, what they called the coolie who did the dirty work. Most of the time there was no central heat and the fireplaces were to change. Often there was no central plumbing in the early days and especially up country, and that meant plumbing needs to be tended to, water to be brought in. In the city by the time I can remember electricity and running water were taken for granted, but central heat was not always available. So hand labor was cheap and mechanical labor was the extract that cost, but anything whether it

was household service or your clothes had to be made by a tailor. You paid extra if it was machine made. Hand labor was unbelievably cheap.

Donald R. Lennon:

You speak of the electricity and the water being taken for granted. Were these foreign innovations or had they been developed by the Chinese as far as power plants?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I couldn't tell you. I know that you didn't have them up in the interior. It was not the kind of thing. Their degree of sophistication I refuse to use the word civilization on purpose, but the degree of sophistication in the large commercial community on the coast and the complete lack of it as you got in the interior was a study in contrast. It didn't even seem unusual to me until after I got older and got over here. The city of Shanghai at the time we left in the 30's was listed in the almanac as the tenth largest city in the world. We had skyscrapers. We had city water. We had city plumbing. We had electricity. We had radio. Radio didn't come until very late and we only had one or two stations. If you didn't like Chinese music you didn't bother about having a radio because there was nothing to pick up, but radio was much later than here. But we had all the conveniences available at any large metropolitan commercial city, but who put them in I don't know. I couldn't tell you. There was the municipal function, Shanghai Municipal this, that and the other including a racetrack, sports events and all kinds of things. Then if you wanted to leave Shanghai to go anywhere you could go on the railroad but there were only two railroads. There was one that went directly west for a short distance and then one that went up towards Peking and north, but in between those places you just didn't go. There was no way to get there. If you wanted to go west to Europe you could go through the Trans-Siberian Railroad with several options to get up to Harbin mostly by water. You could go by train to Peking or you could go all the way around either Africa or all the way across to America and then across by

boat. Flying of course was unknown and the railroads were very few and the automobile road was nonexistent.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you had no travel during that period by horseback or anything of that nature?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

No. This requires a road. Now the way they did travel in the interior was by waterway on a series of canals. There were paths along the waterway where you went by wheelbarrow. People as well as belongings went by wheelbarrow or sedan chair which required only a path wide enough for one man, and it was the kind of thing where you took all of your goods with you when you went. You took all your food if you were afraid of local food and the sanitation was not what we were used to. I know my father never would eat a canned cherry because by some error on his long trips instead of having a variety of canned fruit it was all one kind. And after that he couldn't look at a can of cherries. We never served them, never. You carry also your cash money, which was the money with a hole in it. I say cash because that's what they called it, the Chinese money with a hole in it. I don't know whether that is a corruption of the Chinese word; I doubt it. I imagine it is an English word applied to it, but it was in strings and you carried it in terrific number. It used to be ten of those to a Chinese penny and three Chinese pennies to an American penny and then you multiply that by a hundred anyway you had chains and chains of this stuff for currency. Hard metal was the only thing anybody wanted to take. There was no central government, therefore no paper money that anybody wanted in the early teens of this century. So you carried a wheelbarrow with several wheelbarrow loads of this money and then you would have to have barrows for your things, your luggage and stuff of this kind, and coolies that either pushed the wheelbarrow or carried the sedan chair. But the usual and the pleasantest way to travel in interior was by houseboat. All of the belongings would be put together on a houseboat and would go by canal, the grand canal you've heard of, and other small waterways.

You would pull up at night on the side of the ditch bank sort of like the Wind in the Willows. Then you would move on and if you got to a bad place where they have rapids or hard going they even had coolies who would put out ropes and would haul you up stream if you had to go against a current. It was like a towpath, and you would crawl up. I think this was probably a lot more comfortable and a lot more pleasurable than the chair trips but some areas you had to get across. Now there were riverboats that you could go up the river to Hankow. They went up there without going by rail; they went up by boat. You would catch a boat in Shanghai and it would go up river, very much like what you read about in that book the Sand Pebbles. That type of thing. I never got to go up the Yangtze. I was in school during the spring and fall when you could have gone; and in the summer when I was not in grade school or high school, the river pirates were too active for it to be time for it to be a safe trip. So it was not like playing Peter Pan for the pirates to really have been factors. I would like to have seen the Yangtze Gorges but the times that I could have gone it was not safe because the pirates were on the river.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, this is a question I was going to save until later but since you brought it up. What about the degree of piracy and highway robbery or what have you? You mentioned having to carry two coolies along for a barge when you traveled by chair.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

This was long before… This is just hearsay but in the early times when my father was traveling, people of any means, Orientals as well as Westerners, would not think of traveling with all their possessions without somebody of a body guard nature when they were going. This I say is only hearsay. The bearers and somebody to defend them in your employ were pretty much a usual thing. If you went very far you would have to make changes because none of them would care to go a whole trip with you. They would go only so far from their own native village and you would hire somebody else. And this would be done by your quote "boy" who was your

major domo, who would argue for you in the market when you'd try to buy fresh fruits, who would arrange your travel matters, and who would manage your affairs and grease the palms as they were needed. Greasing the palms of people who provided your health and got you what you needed was considered no more immoral than tipping a waitress in our culture, and this again is something that is very hard to get across. They speak of so much payola and so much undercover things, almost like it's a Watergate sin. But it is part of the culture and is no more thought one way than another than tipping a waitress is in our culture.

Donald R. Lennon:

This included court officials?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I couldn't tell you about that. I assume it did. I assume that is what is talked about. I was thinking in terms of just business of your local grocer who gets a cut from your cook for being sure you get fresh fowl instead of something that is old. Your household is headed up by a "boy" who is like a butler who is responsible for the behavior for all the rest of the staff. If they get along with him they get to stay. If they don't, something will come up and it will be necessary where you have to choose either between your "boy" who is your man in charge and you don't deal directly with the lesser help. He will supervise.

Donald R. Lennon:

You do nothing to make him lose face.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

That is right. And you do well to support him. If you don't like the way he does it, change your top man but otherwise he won't accept responsibility for the whole crew. I know, as an aside to that, in just living, I was an only child after my brother died. Here you had the problem of the big city, all male servants, and a little girl growing up in the household. The way my mother solved that was we had this old nurse that had nursed us as her last children and instead of letting her go which you normally do when a child reaches a certain age, she was kept on. We called all women servants amah's. A-M-A-H was just a word for nurse. It came I guess from the

Indian Culture. It is an Indian word. It isn't Chinese, but anyway it covers the situation. She stayed on as a resident, these were all resident servants, as a resident in the household in order for the chaperonage for me. Otherwise my mother could not have gone out on her own free will and left the household with five and six resident men and a young girl growing up. It just wasn't done. Some of the families solved it with white Russian governesses. Usually it was by hiring somebody female to either do the laundry or be a maid to the mother or to be a governess. In this instance, I had a personal maid until I went to college. Talk about luxury, that is it. But it was absolutely necessary unless you were going to leave a young growing girl in a household with six or seven men working which just was not done. Other than that, we never really knew.

We had the same servants for years. I can remember three or four of them that go back so far that I couldn't remember when they came to the household. We were blessed. We didn't have a lot of turnover. Probably because we were pretty stable ourselves and lived out there just steady. We were not coming or going. We never kidded ourselves that we really knew them or knew what was happening. There were rooms at our place that they could use and a kitchen of their own which was the old kitchen when we put in the modern one. Actually, it amounted to giving them a social room, and they did their own cooking as much as they wanted. Several of them were married and had families elsewhere and stayed there sometimes and sometimes not. But old Amah we called her lived with us until her Parkinson's which she had got so bad that she went with some of her nephews in town. She lived on the place, and one other had no other home as far as I can recall. But most of them came and went and usually on Chinese New Year they would bring their families to pay respects to the boss. It was not at all unusual that when they came one year by the scars on their face you could see that several of the children had had smallpox. And you asked when that happened, and they said, "Oh, such and such a time."

Sometimes in the previous year, and mother said that we'd know that he didn't miss a day of work with smallpox.

Whatever went on in their household they did not share with us in the intimate way that many people feel that they got to know the Chinese help that they lived with so much. I am quite sure that they knew a great deal more about us. One of the big things, many of them have a real facility with language. My father used to be real upset frequently with some of the younger people that would come out there, because at dinner parties after a cocktail hour it was not unusual for the Americans to get to talking quite freely not realizing that the servants who were in the background could understand a great deal of what was said. In those days if big business and dog-eat-dog and business secrets and international intrigue, too much of that went on. It did not behoove a person to talk too freely in public because these men that were the waiters, we called them "boys" all of them. The servants were taken for granted and they served so beautifully and so unobtrusively that it was just unbelievable the naivete that some people had, that they were as indifferent to what they were hearing; and much gossip of various kinds got out that way. I know in this vein during one of the anti-foreign uprisings of which there was several in the 1920's, after one tense time things had been very anti-foreign. I remember my mother speaking to this "boy" that had been with us further back than I can remember, and she was saying to him, "now surely you wouldn't kill us, would you?" And his answer and I was there when he said that, said, "Oh no, Missy I no kill you. I kill next door Missy for next door boy." I mean this took care of the matter of friendship and loyalties. So I don't think we were even under any illusions of a great loyalty that would have taken over above loyalties that they might have had.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you feel at ease growing up in China?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Why not? I mean I'm sure I felt more at ease than my mother would knowing life over here. The time or two that I came over here, and I spent a year when I was in the fourth grade and one when I was in the sixth grade, I thought this was dullsville if I'd ever lived in it in North Carolina. The things that interested children and adults were so trivial and monotonously secure, and yet whenever we went back out there the exciting stories that I got from my parents was what it was like when they were growing up in the United States, what the States was like. The exciting times in high school were when somebody would come back with new records from the United States or when a boat an American boat like one of the Dollar Line Steamers would put into port and you could go down there and get a Coca Cola, beautiful fountain drinks. You could go to the soda pop bar on the top deck and visit on board and get a Coca Cola which was not available of course in Shanghai. Coca Cola was the invention of the day, so were new records phonograph records which were usually about six months getting out there. It was behind. But we I think were no more alarmed and no more wise than other children in large metropolitan cities. We lived a city child's routine. I didn't expect to know my next door neighbors. On one side there happened to be a Belgium, a big residence that had been converted into a Belgium school. Behind the other side was a series of little houses inhabited mostly by Scandinavians and beyond them was the Russian Orthodox Church. Then down beyond the Belgium school was a whole area that had been converted into barracks for the French troops. Across the street a wealthy Chinese lived behind a high great wall, and just down from him was a home that used to be I didn't know what but it had been converted into a movie production house. Now I lived just like many a city child in an area where I didn't expect to be friends and never associated with people living right around us. While in contrast, about a quarter of a mile away was a large compound with a street with about eight houses on it. It belonged to the American YMCA outfit.

They were all American families about six or eight of them as I would recall it living in one walled-in enclosure. But once you got inside it wasn't too different from a street over here, lawns without fences and people in and out, and people whose parents worked with each other and who knew each other all living in one group.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you socialized in the compound more than you did out in your neighborhood?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, I did at times but I did not always, because those people came and went and we stayed. Now the school I went to was a large American school. It was at that time the largest American school outside of the Continental United States. We had around six hundred children. We had a big plant with a goodly number of buildings and dormitory facilities for high school students. I'd say we had about six hundred students there when I graduated in 1934. I know our graduating class was fifty. Now of those fifty in the graduating class there was one child who had been there the whole twelve years. There were two who had been there with one or two years back on leave who had started in the first grade and graduated. The rest of them were children who had been there for one or more years. Some more than others. The boarding students usually finished the four years.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, were these schools quite similar to our American schools?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

This one was exactly similar. The course work and the accreditation and everything. It was private. Of course naturally you wouldn't have a school that was state supported. There was no government out there. There was no public facility. It had a board of directors that was pretty evenly divided between business-men, missionaries, and some representation of the diplomatic corps. That was a big deal. And very little on the military. It was almost half and half. Missionary and business with the diplomatic corps and the military providing some representations locally, but they had a charter and corporation and people over here soliciting

money for them and all that, it was a private school. It had twelve grades. The teachers were the same type that you'd expect. The course material was the same and we were accepted without examinations in the American colleges. It was different in that the children that went there, the American children particularly but all of the them generally, were from families whose parents for some reason had something exceptional that made it worthwhile for either a mission board or the military or a business corporation to send them out there. We didn't have a typical America school because there was a whole element of our population what was not represented. They set the school up I don't know when about 1920 or so, and by the time I came along and entered school they were in their new plant and me and the plant grew up pretty much together. But there was to be space for any American child that applied. Then if any other room was available other children with European parentage were accepted.

Donald R. Lennon:

They never allowed Chinese children there?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Yes, they did eventually. But this is the way it started. Then before it gave out and it gave out with the Japanese occupation is when it was taken over and of course there are no American schools there now. But we have a little organization that keeps in touch some and I get some things back and forth. There is a man in California who is trying to get names and addresses of everybody that he can hang on to that ever went out there. But anyway, they started taking a few Chinese children in the 30's. The first breakthrough came with the Chinese teacher. The best Algebra teacher I ever had was Chinese. Evidently, they had difficulty getting teachers and they found a qualified Oriental. I don't know where he went to college but he spoke English as well as I do. He taught math. Then gradually a few Chinese students were taken in, but it was not designed except for the people wanting to prepare in the American system. There were some good British schools older than ours, and children of British parents who expected to send them

to the British university had them schooled in the British schools. There were several of them and they were very good. So we had people of different nationalities but mighty few Britains and the same way we didn't have many French. There was a very active successful French school with everything taught in French, and the scale for entrance was a test that they give for French university level and a prep school and fixed for their own educational pattern. So what we had were a great many highly educated White Russians that came after the Bolsheviks stuff and all. They sifted right across Siberia and came down a lot of them landed in Shanghai and stayed. Their children many of them went to our school and added a great deal. Some of the most able - I was thinking about my own class. The top honors when she graduated from high school was Tonya Pechelky who came in originally into the school at third grade level not being able to speak a word of English. She got going well in one year and was coping with fourth grade work and from about the middle of the fifth grade on led the class. Her brothers later came in one at a time under the quota and live somewhere in California. I think her brother did equally well and ended up a dentist. Then there was Carlo Bosk whose father was out there in shipping.

There was Bruce whose sir name escapes me but he used to come to school in kilts. He was Scotch. We had a variety; but the variety was modified by the groups that were in sufficient numbers to have their own schools, which meant the British who were very strongly for separated education. They had boy schools and girl schools. They had several. They were the largest I guess of the western community out there and the French and then the Germans had their own schools.

My first knowledge of anything happening in modern Germany that was unacceptable to our culture was as a very active girl scout. We were girl guides out there. The intercity rally excluded the German troop because they could not accept the mixing of international scouting

with the Hitler youth. The Hitler youth business had taken over so strongly in this Girl Scout troop that the local committee that made the intertroop activities which in our instances turned out to be international activities. The American school, the various British schools, the French schools, the German schools, Japanese schools, they each had their troops; and when we had intercity activity it amounted to a little international activity. But the powers that were our adult leaders probably on directive from international headquarters, I don't know, ceased to allow the German troop to participate because of their political takeover of the scout movement and using it for a Hitler youth organization.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had not seen any actual difference in the German scouting unit that you could observe?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well now, no. As I could see it as a participating active child, we went to rallies which were held for the girls just as active as the boy type things you have here. When we had events and participating in them, there was never any reason for the cultural background or the indoctrination to come into it. I mean you could tie a knot just as well without it being whether you were a Christian or British or German. You know it didn't matter. And frankly, the religion never came into it. Jewish, Christian, Catholic, whatever, Buddhist it didn't matter. But the political line had raised its head enough for the powers that be either in London or Geneva where the Girl Scout headquarters are, or perhaps it was local with them. I don't know, but it was decided that that particular club from the German school was not in the spirit of scouting; and we ceased to include them in the club. This was the first time that I as a teenager was aware that things were happening in Germany that were unacceptable to our culture. It was amazing.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, that was just a little thing but that little thing, they were dropped.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned the missionary children being in the school. I have heard numerous times that the missionaries would have no social contact with the business community by and large as far as the tobacconist and other businessmen out there. They seem to hold themselves apart from the business community. Being with the missionary children, did you socialize with the missionary families at all or was this taboo outside of the school themselves?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

No, your problem in the school and the problem in the town were two different things. In the business community in town there was friction between them and the missionaries, not with the missionaries that were out there with a purpose like the medical missionaries who were running their hospitals or the professors who were teaching at the various universities. There were several missionary-oriented top grade universities in Shanghai. St. John's Episcopal University was one and then there was a Baptist one whose name escapes me offhand.

But there was a breed of missionaries and I guess you would call them exalters. I am afraid we often felt that they were people who could not get churches satisfactorily over here and reacted to the glamour of the foreign field. They were characterized largely by negativism and denying their own quietness and Westerness. This type of people made it so that many Oriental equated Christianity with Western culture. These people came into constant conflict particularly with the tobacconist because many of them felt that we were introducing a sinful substance as sinful as opium. The living habits of the business community in the 1920's were something less that puritanical. Shanghai is the 20's I suppose roared as good as any city, but the people taken as individuals were a different thing from just the mass attitude towards each other. My mother who was very circumspect in her habits and never felt quite at ease with many of the city ways though she lived there by preference for years. A good many of her friends were women from the missionary community. I don't think she ever got along too well with some of the men, the

preachers and this kind of thing. We were not a real strong church-going family but not being a smoker or drinker or playing-cards-for-money person herself she got along very pleasantly with a number of the university wives and missionary wives that were local.

Now when you get to the school situation, the living thing made a great deal of difference. The students who were day students were mixed from all types of European exposure. There were ones who were military top level people who were allowed to have their children. There were children of diplomats. There were children of businessmen. There were a very few children of missionaries stationed in Shanghai. Most of your difficulty with missionaries came with those who were out in the field for the Lord, trying not to be sacrilegious here, but ones, who lived up country. Some of them you knew just a terrific difference in the backgrounds of many of them. Their children came down to school in the Shanghai American school. The children were no problem. The missionaries who dominated the school governing boards were extremely narrow and when I say extremely narrow I mean extremely narrow even for that time, stupid narrowness like allowing the boarding students to dance with the record player but pinning a sheet of typewriter paper on the boy's chest so that it wouldn't get crumpled by his date when they danced. This is the type of narrowness; they gave to the point of allowing dancing but… not touch. The children from these missionary families coming up were usually extremely academically able and very very out of it as far as knowing how to move about. Well all of us living out there were completely unequipped to cope with normal teenage and college age social relationship functions we have in schools over here. They way most of them got their preparation when they were away from the city and couldn't go to day school was through the Calvert Schools which takes you through our usual eight grades in six. They send the entire materials out even to crayons and erasers to the mother or the father with instructions for daily

teaching, grading, tests and final grades that are sent into Baltimore. It has been used for years by people who were away from systematic schools or children who were bedridden. It is a very very effective teaching system. Everything comes in a package. You don't need to have anything except a table and a chair, and it equips an intelligent mother to do home teaching. So these children would land up there in schools at the end of six year ready to start in as a freshman in high school among the ninth graders. The textbooks that they used were the ones that had been- well I know the general science book that we had in the eighth grade, these children had worked through at home in the sixth, that type of thing. They did very well but they lived alternately a very dependant life in this rigid social regime, dormitory existence, and all of that. At the same time were extremely confident and independent. If they came by boat, if they came from the Canton area, one of the older ones from that particular mission would go down and make the arrangements for transportation home at Christmas and for transportation home in the fall. They took care of themselves, getting themselves back and forth. Whether they came two and a half hours by train or whether they came two and a half days or three days by boat, they were all perfectly able to look after themselves and expected to.

There was one Christmas in about 1931 I guess it was when there was a great deal of trouble with the Reds in the lower part of southeastern China and I had a classmate spend Christmas with me. Listen to this and you think the Communist in China was something new. This was in 31. She came up to school in September and she had no letters, no communication of any kind with her family until she went back in June. The political situation was so bad in the southern part of China near the coast where her family was stationed it was not considered wise for her to come home for Christmas. She didn't hear from her family until late spring.

Donald R. Lennon:

And this was due to the Communist rather than Japanese?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

This was due to what we call quote "the Reds". Now this was in 31. It was not the Japanese. The Japanese are something else again. But there was difficulty with the local war lords all of the time. It was just accepted as a matter of fact. It is difficult to explain to people here how just because you have a large country on the map all painted the same color that it isn't a nation at all in the sense that we consider a political entity where you can have a government where somebody is in charge. The other thing that is hard to get across to people is there are places and there have been times like we lived in out there when there is nobody in charge, literally nobody. We lived under a very strange political arrangement called extraterritoriality which meant that we were foreign citizens each subject to our own foreign regulations, laws and court. And you say how horrible. Then when you realize that there are no local courts belonging to the so-called country of the ground that are in any control and that the other alternative is to live without any quote "law and order". There is no responsible group that you can turn to and question. Then it gets to be where sometimes your choice is, are you going to have too much government or none at all? I can put that into real concrete terms when I say that shortly after they built some paved roads going out of the international settlement in the French concession. The paved roads were allowed by I don't know whom but they were considered part of the settlement. Friends out for a Sunday drive decided to turn around, backed off the road onto the shoulder at some spot that seemed wide enough, and started to go back and were immediately arrested by some local constabulary for being off the road and in an unlicensed spot. They were out of the territory where they weren't supposed to be. I don't know whether they were supposed to be or not but they were apprehended by a group bigger than they and taken to the local Chinese jail in what we called the Chinese city. There was a group that controlled that, who they were and what or whether they were part of a national government this is I doubt; but we'll just

say they were arrested by the Chinese. A friend coming along behind them in a car also an old China hand someone aware of the situation was smart enough not to stop and get involved or he too would have been apprehended. We take so many things for granted. He sized up the situation and passed his ailing brother by. I was saying that this friend whose name I cannot remember and it doesn't matter but he was more pragmatic and philosophical and we were never judgmental. We accepted things as they were without liking them or disliking them. It didn't make any difference. He went in and got help. This was fortunate because when the man was apprehended there is nothing that says you may notify somebody. There's nothing that says that they will notify anybody. As far as anybody would know, they went out to ride and disappeared. They might or may not get released. The problem might have come up and they might have taken it through channels to the local consulate. They probably would have in time but it might have been a couple of days of where is so and so. As it was, the action was taken immediately and I've forgotten what the situation was and what explanation was offered; but they and the car got back. This was fine. But the thing that is so noticeable when you start mixing cultures is that things we take so for granted like right to a lawyer or right to make a phone call, the right to a speedy trial, or the right to a trial at all is not a part of the culture.

Donald R. Lennon:

So even with extraterritoriality there was always a danger of an American being arrested.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

That is correct. There were places where the Americans were not supposed to be; and if he went there out of order or if the arresting person who had a gun decided you were out of order, you didn't argue the point. So we learned very early that there were things you did do and there were things you didn't do. There were places you went; and yet surprisingly when we were on the train or somewhere, you just avoided the military and tended to your own business and let

somebody know where you were going. So if you didn't come back, someone would be aware of it. But it was all taken very matter-of-factly and by those of us who were children whether they were military or missionary very non-judgmentally.

Now, we had Jewish friends in school. There was no anti-Semitism that I ever encountered as such until I came to the United States and ran into it in college social life to my astonishment, and what is amazing there is the person who brought this to a head was a friend of mine who was hurt somewhat, Kate Saultsburger. The last I've found out from her, she is now the wife of our present Attorney General, Edward Levi. She came from Chicago to a Virginia school and that's where I found out about Jews. I didn't know about it. We had lots of Jews. We had lots of Russians. We had lots of all kinds of people but it didn't make any difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were kind of in a protected society.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

We were in a very protected society, but it was also a very non-provincial society. The thing that was the most narrow in it, and it becomes increasingly evident as I get older, is that we were in a highly select group. Everybody there were people who were there because of some special reason or talent. The average person or the non-adventurous either of those traits stayed at home. Now I have several friends who were second generation in China. Their parents before them were born out there. So it was really not as foreign a country as it might seem. Life was good. It was exciting. There were things happening in the local newspaper by people you knew. You felt like that you were making the world go around whether you were or not. When those various incidents happened that are in the history books now; we were there. We read about them in the morning paper. It was my privilege to have a very good Chinese history teacher. We were required to take Chinese history before graduation because the school fathers felt that it would be bad to have a diploma and not know anything about the country. The year I took Chinese history

was the 32-33 school year. If you will recall, that was the year of the Japanese-Manchukuo. I had a very wise Chinese history teacher who skimmed us very very quickly through all the generations of Chinese history up to the present between September and about March and from March on we used to daily paper and the local people in the various capacities and dealt with what was happening right here. I am sure it was not with the same perspective that time would give a teacher now. There were several places you could go mostly by boat to get away from the humid delta type coastal hear. Tsingtao, which is a city up on that peninsula had been held alternatively at one time or another by Russians, Japanese, Germans, and Chinese. Each of them had left their gun emplacements and their fortifications and their underground connecting passages with their quick turns and pitfall drops; and it was like playing in an old castle moat kind of thing. This was something we lived with. We went by coastal steamer up and watched it for their purposes up in that area in our day. The military advantages of certain spots were known to us and the whole Manchuria business came very close with invasion of Shanghai itself.

Donald R. Lennon:

You actually observed that?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I did. I was there. We didn't see a whole lot but from a child's view and I must say at that time I was much more concerned if whether we would evacuate before I had to take my French exam which I counted on us doing. We didn't evacuate and I flunked. This was you can see mixture there in the view point. The view point being just about as childish as any high school student where the big thing was the mid-term French exam. The fact that they were shelling the adjacent area of the city and if you wanted to sleep at night you'd better get to sleep before the shelling started because it was just about seven miles away. The fact that we had evacuation drills, the fact that duds sometimes fell in our area and one across the street and one at the street corner. It wasn't anything as important as to whether it was necessary to really sweat out that

French exam or would the evacuation that seemed inevitable come in time to save me from the exam. So you can see how valid some of the remarks and observation are. I was very much oriented in my own little world while the rest of it was happening.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you eventually evacuated?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

At that time it turned out no. The Japanese weren't quite like the local Chinese Wars which quit when it got to planting time. That Manchuria thing did resolve itself and we did not come home. This is in contrast to 1927 and about 1924 or 25, I'd have to figure the date. About 1926 and 1928 was two times that the Civil War was sort of bad when it was very anti-foreign. See, the Japanese were anti-Chinese; we were just in the middle. But this when it was anti-foreign, it would always happen. Now here again, it is like my French exam. My father would come over here usually in late June and stay until Thanksgiving cruising the tobacco market. At the time he'd start with Georgia and would have his base up with in Richmond and cruise. Home was out there and visiting was so unsatisfactory that we, mother and I, would stay. Well the Civil War type fussing was going on and the anti-foreign sentiment didn't bother itself much in real cold weather and spring when they were busy; but come summer and fall, that is when they'd take to the fighting. So invariably mother and I would be over there alone with my father over here. Well, that gives you some idea of how matter-of-fact we took the confusion.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you remember any particular incident or stories from this period of War Lords or Civil War activities?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well yes, I remember the time. I remember mostly my mother's tension. Little things are strange but one of them, the tension, mounted so much that she who had been rather set in her ways and puritanical took up her knitting on Sunday which was out of character; and I must have remarked on it. She said, "Well, she decided that the Lord would rather her knit on Sunday than

to lose her mind." Times were tense. And I either didn't have sense enough or took it for granted that it was just exciting. We had for instance kept a three months supply of canned and packaged food in the house. There were periods that the cars were never driven head first into the garage. They were always backed in so they could be driven out at a moment's notice. And a suitcase of things which you needed for minimum stood at the front door packed.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you had to flee, where would you flee to?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

We had various centers. I can remember the family discussions. One of the centers was the school and mother objected and said she wouldn't go there because it would be three or four times further away from the ship. The ship would be the only way to get out. Shanghai was up the water front, and after we left when they did have to evacuate people by ship it was under gunfire as you'd have about seven miles or twelve miles, I can't remember which one, up to the open ocean. This was a right hazardous kind of trip, but they had places and they had warnings, and you were supposed to get out according to this way and that. But we never missed a day of school. We never missed an exam including that French exam. Life went on as usual.

Donald R. Lennon:

By being in Shanghai in the city you probably saw a bit less of the actual conflict than you would have had you been out in the country.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I am sure so. I can remember when we had an influx of children in the lower grades after the Nanking incident. These children who were involved in that whose parents were up there during the rape of Nanking and all of that came down and were in school with us. After the first excitement of a couple of new children in class, it didn't amount to anything more for us. I know it did amount to more for our parents because there were all kinds of refugee needs, and one of the biggest problems which you wouldn't possibly have thought of was refugees pouring in unable to communicate with their Shanghai relatives because of language difficulties. The

Mandarin language, the universal one, is the written language unknown to the masses of that day. I don't know what it is like now. The nearly three hundred, two hundred and seventy-five or sixty that we've talked about dialects were so many that fifty miles geographically and you are in another country where you couldn't make yourself understood. So we had these masses of people coming down without food, clothing or shelter, just escaping in the Civil War in which they had no particular part. Some of them had connections in Shanghai but were unable to communicate. Then there were the many many children. What sticks in your mind were these little odd phrases of what happened. I remember a woman telling my mother that they had improvised by using deep bookshelves and just putting the wrapped up babies on the shelves. You know just a place to cope with many many people. I imagine that was probably an exaggeration in the telling. It doesn't sound as plausible as it did at the time, but they were using anything and everything. The housing and the handling of the refugees was something.

Now later, when the Japanese were coming in and I was at that time in high school and the government of the international settlement was falling apart, the French Concession people sold out to the Chinese and things were tense. The men in the community had what they called the Shanghai volunteer corps, SVC. The able bodied them belonged to it. My father was too old a man for that. But they had just like the National Guard here really. When things got bad enough in the 30's and there was enough restlessness in the town, they couldn't use the boarding students because of parental problems and concerns; but the day student boys who were well developed grown juniors and seniors in high school, they did their turn of duty with the volunteer corps just like their fathers. The only concession that they made was they didn't ride the riot squad at night. Oh it was considered quite glamorous. Put yourself in the teenage frame of mind when the school heroes of the great day hulking athletes came to school in uniform and put their

rifle and ammunition in their school locker, it sort of makes it different from the local high school attitudes. They could do. It was a matter of riot control and looking for I suppose bomb threats and this type of thing. But they were excused from school and did their tour of duty and came to school in between times. Simply because the police force was completely demoralized, our local government of the international community somewhat demoralized and men there anxious about property and lives took over.

Donald R. Lennon:

After the Japanese actually came in you had left to come back to the states by then.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I left to come to college after I graduated in 1934. My father stayed one more year and because of his health he left then. Some of my friends, some of the family friends were out there longer; and it did become necessary to evacuate the company personnel and the women and children from town. There were several boats that were commandeered and there were stories about people I knew who had been on them. These tenders were kind of like barges that carry people out to the deep water boats with only two men per tender or four men at most with these tender loads of children and women, taking them down. The sea was so rough that when they got past the gunfire across the river from the Japanese and whoever they were shooting at them and got out to the boats it was so rough this is why it sticks in my head, that they literally had to take these people and wait till each wave crested and throw them from the tender up into the arms of some of the crew men on the boat and this kind of thing. Well now, that's more a matter of nautical interest except for the fact that there were few men left to escort these women and children and some of them were later interned in Honqui Prison which was one of the ones that was the least cheerful of the internships. That was in Shanghai. I have not talked directly to anybody personally who was involved in that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well did the Japanese leave the missionaries alone more than they did the business people or did they make any differentiation?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, I never saw anything where anybody left alone or had any dealings whatsoever with any people one to one. At the time I was out there it was Japanese going into northern China, into Manchuria. What they wanted I feel sure were those iron deposits. It is extremely wealthy area up there and I don't know what or whether it had anything to do with the railroads that go through up there. I don't know quite what but the Japanese incident is all what I ever heard on that. My feeling was just that they were after territory.]

Donald R. Lennon:

Why I asked, I know quite a few of the missionaries did not evacuate at the time that the Japanese did take over there.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, I couldn't answer that because it was not the Japanese that…. I guess it was though the Japanese that interned the people in Shanghai. They were intended in Honqui Prison. That would be the Japanese doing that to the business people that were there. Now what was very noticeable earlier, and this was back in the War Lord days and all, that was the difficulty that anybody had who was connected with the press. It is I guess not unreasonable but they felt like everybody who was newspaper oriented all was a spy. I know the Russian feel strongly on that score and there was one person, only one, that I know anything of personally. A man by the name of J.D. Howell, who was way before the Japanese problem, was captured in some of the anti-foreign business. I don't know exactly where he was interned or kept in prison but he eventually lost his feet from frostbite. He must have been up around the Peking area. It had to be happening in about the 1920's, it was not the Boxer Rebellion. But he was a newspaperman. He had two sisters who were married, one to a dentist and one I don't know what the other one did but they were not newspaper people. The sister that was married to the dentist had been a

newspaper photographer. They lived in Shanghai and it was their brother that had such a hard time and was held up because they felt he was ever interned or arrested or imprisoned but we knew that wrote a great deal, was a newspaperman called Carl Crow. His daughter was in school with us. He wrote pseudo-fiction. I would say on the order sort of like Pearl Buck's stuff but not up to Pearl Buck. I've got some of his books and he knew Chinese life and he wrote well about it, but he did not write as well as Mr. Buck.

Donald R. Lennon:

Speaking of writing, did you feel that Richard McKenna captured any part of the …

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I thought he was great. You've talking about Sand Pebbles. I thought that said it as well as anything I've seen. Now I can't tell you about the details of his engineering, the engine room and all that.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the attitudes of the Chinese…

Jane Gregory Marrow:

The attitude of the Chinese, the attitude of the various foreign elements was well put, and it was not overemphasized, and his descriptions of the torture were not exaggerated. I have heard just that type of thing. I don't like to think on it, but that type thing was done. It was common place enough that I remarked some years ago to my son who was in college and ROTC that if he went to Vietnam I'd rather he'd be dead than captured from what little I know of the Oriental mind. The deeper thing you have to hang on to all along in all you say, do or think about it is to somehow set aside our own cultural values and not try to judge right or wrong for Asia. For instance warfare for them has not emerged out of a culture of chivalry where it is alright for men to fight and there is a nice way to do it and that you protect the ladies. To them war or fighting, call it what you will, they won't speak of mass war but they do things in little groups generally more than in national groups. But the whole concept behind many of our peace treaties really require an understanding of the western age of chivalry if you see what people are trying to

achieve. If you are not willing to throw that out, you can't meet on anything like the same grounds because what is right for them is just as far wrong as we can't go along with the cannibals who in good conscience can eat his enemy. There is one of your big stumbling blocks. But you cannot decide on torture and stuff like that if you are going to have certain means alright and certain wrong.

Donald R. Lennon:

Isn't this probably one of our greatest problems in not only the Orient but in some other areas is trying to use American standards, American values, American culture to live in someone else's world?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Well, it is true and our thing is not singularly American. Our roots are stronger than that. You have to go back to the Roman and the Greek especially when you get Western. When you get into your pattern of legalism and this kind of thing, a group like the Chinese have no legal basis behind them in that sense of courts and stuff to build on. They are not concerned at all with that. They have never thought in those terms. Now my father out of his experience used to say that he felt that the Russians, that time when he said Russian he meant what you'd think of as a Central Russian not the fringe ones out towards Poland and not the extreme ones that are really Mongolian, but that the Russian generally understood the Chinese mind. The Chinese mind is a product of many many centuries and it will be longer than I can live to tell whether one or two generations of brainwashing that is happening now that is satisfying the physical needs of the people so well whether that will undermine the thinking of a people that are far more individualistic in their culture than anything. We are community oriented compared to them. Much more so. The idea of sacrificing everything towards the group has been developed so well apparently under Chairman Mao. I just wonder if this is just another one of the bends that the

Chinese civilization has been able to make and that two or three hundred years from now it will just be another and they will bend back. They give with the wind if it's necessary.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you see the results of Chiang Kai-Shek's rise to power or attempt to rise to power at all before you left?

Jane Gregory Marrow:

Only indirectly. In this first place he was not particularly admired in the western community out there. He had a house behind a fence that we passed going back and forth to school. I never saw any activity going in and out. I never saw anybody, any guards or anything; but he was there. I never felt, I can't speak for my missionary friends but I think if they had been for him I would have heard it. I never felt any great confidence that anybody thought that he was anything more than a rice Christian. The people I talked to since then who were out there with me, their families and all, I speak particularly of Oliver Caldwell who is quite distinguished that I saw some years ago. The folks out there didn't admire him. The general feeling was that he took the United States public pretty good on the basis of on-the-cuff Christianity. His wife's brothers were both rather distinguished men T.V. Soong and H. H. Kung were just outstanding. But Chiang Kai-Shek was a War Lord before he was married; he was a War Lord after he was married; and he is still a War Lord, and that is all. Now in Chinese culture the lowest person on the totem pole in society in the caste system is a person who makes his living fighting. So a general is no impressive. The highest person is somebody who makes his living thinking not doing and there are all kinds of doings in between, but the professional soldier is the bottom man. The national party had succeeded and Sun Yat-Sen provided a very convenient martyrdom that they used, and they built there Manking Complex up there. I have been up there and seen their things and it was interesting. He brought some semblance of law and order for a while which was comfortable, but it was rather highly overrated in the press as far as people outside of

the Orient are so accustomed in thinking of national entities. Very few of them realize that the concept of national entity is rather recent. I think it's only in the 1800's or something after 1815 that the modern era that we get away from feudal states in Europe and the guilds and all that stuff and get into the nation as a modern concept. It is really rather young.

They expect as soon as anybody takes over and takes charge in any sense that he can speak for the entire geographical area shown on the map. He cannot. He can control only so far in a country of that kind as force will allow him. He never ever had the unity of a single nation that I think the average mind over here expects when he says I speak from mainland China. Now he couldn't have even if he wanted to. I don't think. When you have a high grade of illiteracy, a very difficult written language, all those. Just the communication problem if you threw everything else out, all of those different dialects. Granted the people there have just as much native intelligence as anybody and a lot of them more. I mean just by strict survival. You just don't have as many deadheads lying around. They are apt to be underrated. But railroads were few. Modern roads were just coming in the 30's. I know the first one from Shanghai west, you could ride on it in 1932 for the first time, 31 or 32 that you could go anywhere except just in the city limits in an automobile. If you had an automobile that was fine, but there was no where to go in it except in a huge city which was well. It wasn't bad. It was better than walking, but you didn't have to have it. Then your water transportation is what kept everything going, but it was never ever a unified nation that got mixed up.

Have you read Snow's book on Red Star Over China?

Donald R. Lennon:

No, I have not read that. I am familiar with it.

Jane Gregory Marrow:

I mentioned his name to somebody else who was out longer than I and he was considered a red sympathizer at the time, that was very much out favorite because the western