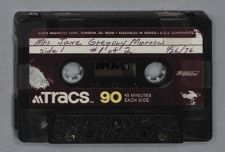

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #3 | |

| Quentin Gregory | |

| Halifax, North Carolina | |

| Tobacconist in China, 1905 to 1920 | |

| March 22, 1972 | |

| [Interview by Donald R. Lennon] |

Quentin Gregory:

. . . when the Boxer trouble was finished. The foreigners . . . these boxers were fanatics you know. They wore red belts, and they thought they were impervious to bullets. They held that for a long time. They came very near conquering the legations. They took over there. Finally, General Chaffee came up with his army and marched up from Tientsin which is about ninety miles. They stormed the city and drove the Boxers out. They completely subdued the Chinese. The German minister had been assassinated. The officials sent for him. They told him to come up and talk it over. None of the rest of the foreign diplomats would go. Von Ketler was his name, he said, “I'll go.” He got on his horse and rode up the main road. He got halfway there, and they waylaid him and shot him and killed him. They wounded his attendant and he escaped and got back home. The German Kaiser sent word to his army to destroy them, loot, pillage, rape, and kill. They did that after they took Peking. They went right down the railroad to Shihkiachwang, burning everything they saw. They really put the fear of God into the Chinese. When I

got there in 1905, which is now five years afterwards, they had completely subdued the Chinese. They were just as scared of a white man as. . . . well they were really scared of white men! Then, the legations took over. They took Peking back. They sent all their diplomats and ambassadors from each country to take over. They [the Chinese] stayed subdued there for years and years. With the Boxer trouble, they [the legations] made a big indemnity on China. Each country wanted to complete his expenses. The United States said we will forgive you. We won't indemnify you. We will give you back your indemnity. That little movement on the part of the American officials gave the Chinese people a great love for America. It wasn't many million dollars. But, while I was over there if you said I am a Meiguoren [American], by gosh, you were Number One! They really loved us. You could go anywhere you wanted in the interior of China and they wouldn't bother you.

Donald R. Lennon:

It gave the Chinese a greater respect for America.

Quentin Gregory:

And as far as could be, love. They called all the foreigners Waiguoren, foreign devils. Although they showed love for Americans at that time, they had in the back of their heads that they wished they could shove all of the white men into the ocean. That was their attitude.

Donald R. Lennon:

Could you see much subdued hostility on the part of the Chinese?

Quentin Gregory:

No. But, I could see that it was there. You see the missionaries were going pretty strong then, but they were always against the missionaries. There were very few converts that they got over there. When the time came, they got control and they kicked-out all of the missionaries. I don't know whether you want to record anything else here, but if you would like to ask me some questions, I will be happy to answer them for you.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just your comments and your impressions of the country would be as important as anything else. Just how you viewed the Chinese people, the conditions in China at the time you arrived and while you were there. You were there fifteen years, were you not?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. Fifteen years.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was what tobacco company?

Quentin Gregory:

This was the British-American Tobacco Co. Limited that is headquartered in London. I was then twenty-five years old and they employed me to come over and work with them.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were in Peking most of the time?

Quentin Gregory:

I was first sent to Tientsin which was about two million people. From there, I went to Peking and had charge of the whole northern district. Eventually, I was made the general inspector for the whole China. I traveled all over China into Manchuria and up into Harbin and Mongolia, too. But, the Chinese were hard-working people. A Chinese banker well, his word was his bond. They were really good on their word.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your impression when your boat arrived and you had your first view of China?

Quentin Gregory:

Well, I arrived in Shanghai--that's up the Hwang Po River--and even at that time, it was a very progressive city of over two million people. Each country had his concession. They all had their concessions there, the French, Germans and the English, and the Americans had their concession. They had built-up the foreign roads. In other words, we considered Shanghai the “Paris of the East, of the Orient.” One of the things I noticed while traveling on the railroad, was to look-out of the window and see people everywhere in the fields. You would not see many trees. There were very very few trees. They were just spotted with people in the fields working everywhere.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the German there? There were a large number of Germans. They had a large group of German nationals in China, did they not? Were they involved in tobacco or just what were they doing there after the Boxers?

Quentin Gregory:

They were not involved in the tobacco. They carried on general business with the Chinese. For murdering Von Ketler, the Germans went to Shantung Province, which was one of the big northern provinces, and took Tsingtao, a hundred square miles of territory, and made that German. They made a really beautiful city there--all shiny German houses and roads--out of Tsingtao. They took that because of the murdering of their ambassador. Of course, Tsingtao belonged to the Germans and they worked out of that beautiful harbor there and into Shantung Province which is one of the biggest provinces up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I read somewhere that the Germans were pretty ruthless in their treatment of the Chinese. Did you experience any of this?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. I knew that they were ruthless at that time. When the Japanese fought over there with the Chinese, the Germans had Tsingtao fortified so that no ships could come in from the sea. But the Japanese, when they sent their army in to take it and drive the Germans out, came in from Chefoo a hundred miles north and marched in from behind down the railroad. Tsingtao was protected by a German garrison. The Kaiser telephoned them to fight and fight to the last man. We said we knew a lot of people there, a lot of Germans were friends of ours and we thought that they were going to die there. Just before the Japanese got there, they surrendered. They didn't fight to die and the Japanese took it. In the meantime though, they had sunk two or three ships in the harbor to keep them from coming in.

Donald R. Lennon:

How were the relationships between the various nationalities (i.e. the Americans, the Germans and so on?

Quentin Gregory:

Well, in Shanghai they had the American Club, the German Club, and the British Club, and French Club. They would mingle together if they saw each other. There was a lot of drinking and cocktails there. They knew each other. We had German friends, British friends, and French friends. I was once invited to a bridge party given by a French man. I was the only man there that couldn't speak French. They are wizards on bridge. They were playing for five cents a point. I knew these people and could understand a little what they were saying, but I could not speak any French. So, as I say, we had friends of various nationalities.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your reaction to the Chinese people? Did you find them very cooperative in your tobacco business activities?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes, I found them to be very cooperative in our business. We built up a tremendous business there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine most of your workers were Chinese.

Quentin Gregory:

We worked with the Chinese. We appointed dealers there. For instance, we would go to Manchuria--there had never been any tobacco up there--and we introduced it by appointing dealers and shipping the goods directly to them. Then they were responsible for all of the payments.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you were introducing American tobacco rather than growing Chinese tobacco?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. I was introducing cigarettes that were made in London, Petersburg, Virginia, Louisville, Kentucky, and in Liverpool, England.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you growing the tobacco there in China?

Quentin Gregory:

We did not grow it at that time, but later on we got some men from this country to go over there and grow some tobacco in Shantung Province.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is when Mr. Doggett came and he was involved in growing.

Quentin Gregory:

What's that?

Donald R. Lennon:

Mr. Doggett that I have told you about; he was involved in growing tobacco in Shantung Province.

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. They had quite an outfit there in Shantung Province. The land and the climate were adapted to it. They had a good start there. The surprise was that all the Chinese tobacco was sun-cured and very inferior.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, it started out solely as a marketing venture of selling American-made tobacco and then later developed into the growing it there in China.

Quentin Gregory:

That's right. The growing was secondary. We had most of all of our stuff manufactured in America or Great Britain and shipped there.

Donald R. Lennon:

During the fifteen years that you were there, did you see much change in the attitude of the Chinese people?

Quentin Gregory:

No. It seemed to be stationary especially in regards to their feelings towards America. They never seemed to have any hostile feelings towards the Americans on account of that indemnity that they gave back to the Chinese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you left before all of the difficulties began to build later that led to the expulsion.

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. I left there after the Japanese got control of there. They had control. They sent their armies in there and they subdued the Chinese. That was why Mr. Roosevelt brought on that Pearl Harbor incident. He really didn't want the Japanese to take any more control of China. I was reading in Life magazine where General Hurley and General Marshall were sent over there to see if they couldn't get Chiang Kai-Shek and Mao Tse-

tung together. As a matter of fact, I think Dulles and Dean Acheson had something to do with it, too. Of course, Dulles was the Secretary of State. Wasn't he?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, sir.

Quentin Gregory:

At that time, he made a complete failure. He was a brilliant New York lawyer, but he knew nothing about politics. It was that man that got us into Vietnam, which we never should have started there at all. We never should have put a foot into Vietnam, and, of course, we all know that now. After Dulles got us in there, Eisenhower backed him up, Kennedy backed him up and Johnson got us in further. Now, Nixon is doing the best he can. He's for pulling us out of there without conquering those people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you take the first step, it is extremely difficult to back-up. Did you come into any contact or have any particular incidents with the “Chinese law” while you were there? I've heard a great deal about the Chinese courts and Chinese law.

Quentin Gregory:

No, I didn't. I didn't know anything about the Chinese law. After the Boxer trouble, the British took over the customs. That's where all the money comes from. Sir Robert Hart, was the head of the customs thing, and he had control of all the imports and all the exports. He was complete lord of the whole thing. The Chinese really had nothing much to do with it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you had to deal primarily through the British then for the trading in China

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. Our headquarters were in London. We would sell our goods and by exchange send our money into London. We go all of our instructions from London.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, this was a pretty vast market for cigarettes that you developed over there in China.

Quentin Gregory:

It's a vast market. We had a big factory in Mukdeo and a big factory in Shanghi and a big factory in Hangchow to make cigarettes. We were making a tremendous lot of

them. When the Chinese and Japanese got to fighting over there they drove the British-American tobacco out. They condemned those factories and took them over, and the company lost the whole thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Chinese take them over?

Quentin Gregory:

The Chinese took them over. It was so long ago, I am not exactly sure about all these things. . . surrounded and stayed in those compounds and came very near being conquered there. If they had, the Chinese Boxers would have killed them all there, that's what they wanted to do.

Donald R. Lennon:

After the Boxers were defeated, what became of them as a group. Were they killed?

Quentin Gregory:

They had no organization. They just disappeared, what weren't killed. They killed them right and left. They didn't take any prisoners, they didn't have to.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any . . . ?

Quentin Gregory:

Old Empress Downager did not claim to be in agreement with the Boxers but she was indirectly. When Peking fell to the foreign armies, the Empress Downager and her train went on carts and what not down into Shansi Province, over a thousand miles. She thought the foreigners would kill her. They allowed her to come back after they settled things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now the Boxers enjoyed the popular support of the people by and large, did they not?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes, but they had no particular organizations. It was just local up to the north there. Down in South China in Shanghai and Canton, they had nothing to do with the Boxers. It was just local around their headquarters in Peking.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, it was years after this that the Dalai Lama came to visit the Empress was it not?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. That was years after. It was 1911 when the Chinese army revolted and they took Hankow. I was in Hankow at the time. We would go out at night to see them shooting over the concessions to the other enemy. The general who had charge of that went over against the government troops and conquered them. That was a thousand miles up the Yangtze River.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, the foreign nationals were not involved in that at all. That was Chinese against Chinese.

Quentin Gregory:

That was Chinese against Chinese. Foreigners were not involved in that at all. We were perfectly safe there watching to see what they were going to do.

Donald R. Lennon:

I don't imagine you were too comfortable though. Were you?

Quentin Gregory:

No. We didn't mind. We would watch them shoot over into the army on the other side of Hankow concession. What you might call then “Concession of Hankow” was ruled by the foreigners. They had complete charge of that, although the Chinese there were fifty-to-one against the white people. It was about a thousand miles from Shanghai to Hankow up the Yangtze Kiang River. They had a lot of shipping up there. There was one place there where if you would leave Shanghai on board a ship, you had to wait till daylight on account of what they called the “sands.” A few miles up the river there was a place there that if you get to close to it, it will take a ship right down. I think there is only two in the world. There is one in the south of England, and then this one on the Yangtze Kiang River at the mouth(?) there. They couldn't travel through there at night, because they were afraid they would hit those sands. I think the river there is about nine miles wide. I've been up as far as Ichang which is way beyond Hankow and that is where the

rapids start. Szechwan Province, which is one of the biggest provinces, is a complete country in itself--a different language and everything. To get up there in those days, you would have to shoot those rapids. The Standard Oil Company did finally build a boat with a powerful little small boat to go up by steam. Otherwise, those boats were pulled up by ropes by the Chinese on the side. I remember Ichang--going down into the city there just below the river. The city itself, is about ten feet below the banks of the river. If that river banks ever broke there, it would completely destroy that city.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, you were saying one time that you went on up into Manchuria and you were in charge of all tobacco operation for all of China and Manchuria?

Quentin Gregory:

We would go up there with our interpreters and appoint dealers. They would put up so much cash and then we would do business with them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Some of these Chinese had excellent English penmanship didn't they?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. They did.

Donald R. Lennon:

This one looks very fluent in the English.

Quentin Gregory:

Their expressions are different.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many of you all were over there working with the British-American Tobacco Company? Was there a large group?

Quentin Gregory:

Do you mean just the white people?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes sir.

Quentin Gregory:

Well, I should say maybe three hundred. I'm not sure it was that many. Of course, we had thousands of Chinese. For every white man working there we would have maybe a hundred Chinese with him.

Donald R. Lennon:

Most of the whites acted as agents more or less, and the actual selling of the cigarettes was done by the Chinese?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. The Chinese did all the selling and retailing. We also had Norwegians, Germans, French, English, and American white men to work with us.

Donald R. Lennon:

I suppose probably the tobacco and the oil interests were the biggest foreign businesses?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes, they were the biggest foreign businesses in China, the Standard Oil Company and the British-American Tobacco Company. They were the biggest foreign trade products.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you think of the TV coverage of Mr. Nixon's trip?

Quentin Gregory:

I thought it was very excellent.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it bring back memories?

Quentin Gregory:

Oh yes. I saw lots of those places where they had taken pictures that I had been right there--especially the Great Wall, and the Ming Tombs. That were North of Peking. They had built that wall right up to a river and gone right down into the river from the mountainside. They wouldn't cross the river, but they would get on the other side and start right at the foundation. It was supposed to keep out the Mongolian armies and Genghis Khan.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's amazing.

Quentin Gregory:

The British would go down there and plant these trees and form a plantation. At one time, they got really prosperous and they had a rubber boom in Shanghai and Tientsin. Everybody was buying rubber stocks. A man would be a clerk in a store and he would telephone a broker and say, “buy me a thousand chimores(?),” but he didn't put up a cent. They'd buy it for him, and the next day it would be worth ten thousand dollars. Well, it went that way for a few months, and she busted. The rubber boom busted there.

There were horse races over there. They get these Mongolian ponies and they would go up there and pick out the best ones and they brought them down from Mongolia and trained them for racing. Shanghai, Hankow, and Tienstin all have a race course. It was mainly for white folks, but the Chinese went too. For instance, in Tientsin the race course is three miles from the city. You would go out there for the spring races and the fall races. When the spring races came, every one closed-up their shops at 11:00 in the daytime. They did nothing for three days. Everyone would go out there and race and bet--the paramutuals, you know. A man would put up ten dollars on a horse and if he picked the right horse, he would make a lot of money. That was just one of their sports. They played baseball and football and tennis and all of that. This was the white folks, you see. These little Chinese ponies weighing about eight or nine hundred pounds carried a 135 lb. jockey. The jockeys were heavy because they couldn't get any little jockeys because they were gentlemen jockeys, you see. They didn't change anything; they would just do it for the sport. There weren't many hundred pounders over there. One hundred and thirty to one hundred and thirty-five was just about as light as you could get for a gentlemen jockey. They rode the ponies, you know.

Donald R. Lennon:

They never used Chinese as jockeys?

Quentin Gregory:

No.

No, they didn't use Chinese jockeys; they always used white gentlemen jockeys. That was one of their sports. I kept two ponies. Some people would keep a dozen ponies and they would have two or three horse “hustlers” to look after them. So, it was something to do, especially for a bachelor out there; he was in demand. There were not so many of them; he was busy going all the time.

Do you know who built the railroads in China?

Donald R. Lennon:

I was starting to ask you that a few minutes ago when you mentioned that.

Quentin Gregory:

The British had their concessions, the Germans had theirs and the French had theirs. They got most their Pullman cars from America. They built these railroads with mostly Chinese labor. Well, what I was thinking about was the Chinese were superstitious, you know. They wouldn't allow this railroad at a city of say two hundred thousand people, which they called a village. They wouldn't allow that railroad to come within a mile of the gates because they thought the Feng Shui, the evil spirits, would take them. They were scared of that railroad. I was thinking of one incident in a place called Hweihsien(?) a big city. We got there about ten o'clock at night. I had my interpreter and my cook with me. I was right there in the interior you know; there were no white people around. Well, we go a mile from the city and got into these carts. We went on to the city and the gates were shut. The gates were great big, huge things that you could carry double teams through. They were locked. We pounded on the gate and finally a man stepped up on the wall. We told them who we were. The soldier came down and opened the gate just so far and wouldn't let us in. He stuck a bayonet right on my chest. I knew he wasn't going to stick me; I wasn't scared of him. I stuck my foot into the gates to keep him back. Finally, after I told him who I was, he let us in. So, that's just an instance of how the Chinese felt about the railroad. There were hundreds of these people who had to go a mile on a cart before they got there, and then they wouldn't let them in. It was the same way in Peking in those days. They wouldn't let them put the railroads in the cities; it was in the suburbs on the outside.

The Yellow River that is called the Chinese Sorrow. It starts way up north somewhere and it comes down and mixes with the Yangtze River. Well instead of doing that, just like the [Mississippi] coming up from Pennsylvania going down to the Gulf of

Mexico, this river would change the course and go right across country. It did that several times. In the summer during the dry times, this darn big river almost dries up.

Donald R. Lennon:

To just a trickle. On to railroading, did you use the tracks built by the Germans and the French as well as those built by the English?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. We used them wherever we wanted to go. For instance, if we went from Peking to Hankow, we would have to go on a British-built road. No, the British were from Nanking directly down the Yangtze River to Shanghai. I forget who built that road from the North. They ran the railroads. The head captains of the trains and all were white men.

Donald R. Lennon:

The tracks were all the same gauge and everything?

Quentin Gregory:

No. The French built a narrow gauge railroad up the Shansi Province. The rest of them were special wide gauge railroads.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, your manufacturing operations had to be built outside of the cities so that there would be easy access to the railroads, did they not?

Quentin Gregory:

Our manufacturing operations were outside the city. For instance, in Shanghai, which is right on the Hwang Po River which is a right big river there, the ships come in and they can't come into Shanghai. They would stay outside and then get on smaller ships and come up ten miles up that Hwang Po River. Well, it's a canal this way and the Hwang Po River this way going all around here. Our factory at Shanghai was across the Hwang Po River on the other side where it's about a mile wide. This was really built outside the city.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have some other thoughts?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. Hankow is a big interior city a thousand miles up the Yangtze Kiang River. Then, there is a Hangchow where President Nixon went down with Mao Tse-tung at his

summer home there. That's south of Shanghai. What a beautiful place it was. I've been to Hangchow and I went there to see the great Bore. The Bore of the river there--have you heard of that?

Donald R. Lennon:

I've heard of that.

Quentin Gregory:

It is the water that comes into the estuary from the ocean. It is a wave of water that comes in once a year on the minute. It comes in and hits this estuary maybe ten miles wide out yonder. It comes into the river just a few hundred yards, and converges there and forms a body of water at least fifteen feet high. It then goes up that river, and it stops the flow of that river. The river is bigger that your Trent River down here. It is bigger than the Roanoke River. The whole water goes upstream. That wave carries that water right back up. There were thousands of people on the bank watching that thing that happens once a year on the minute.

Donald R. Lennon:

What causes it? Do they know?

Quentin Gregory:

I don't think they know. This wave comes from Japan or somewhere on the ocean and it hits that estuary and goes up that river and forms that Bore.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you were one of many traveling down to see that.

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. I went down especially to see that.

They are great vegetable raisers, especially up in the Shansi Province. You get on this railroad which is a French Canal gauged railroad and travel all day long to get to Tian Phu, that's where they had the most beautiful water cress and all the vegetables are so much superior to the ones that they raised down below. They seemed to have a better flavor.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that because of a more moderate climate?

Quentin Gregory:

I don't know why it is. It's high. You have to cross the mountains to get there.

The opium war, you know what the opium war was?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes sir

Quentin Gregory:

In 1840 the British fought the Chinese to make them take their opium made in India. They conquered the Chinese. Prior to that time, when you did some business with the Chinese, they wouldn't let you come ashore at all. Finally they got to doing some business on boats, but they wouldn't let you come ashore. I don't know how long it took to introduce it, but when I got over there in 1905, there were opium dens everywhere. I've been in them. You would go in an opium den up the stairs that take you to a little narrow room and there is a man laying over there on a cot in a sleeping receptacle place laying all doubled up there. He is smoking this opium and this puts him to sleep you see. He just gets a thrill out of it. It is a worse than the liquor habit we have over here, which is the worst thing in the world. We have been talking about cigarettes, but liquor is ten times worse than cigarettes. They abolished these opium dens after awhile. The Chinese knew that they had to get rid of the opium habit. I don't know which emperor or empress put out an edict that anyone caught smoking opium would be beheaded. I was there during World War I with the Tientsin Volunteers and the Shanghai Volunteers. Our duty was to relieve the British. The British needed every man they could get and there were a lot of British who were policemen and ran the police force at Shanghai and Tientsin. They sent these hundreds of Britishers to France to fight and we Americans had to take over. I belonged to the volunteer corps there. We went out for practice shooting and we had our uniforms. Our main duty was to parade the streets at night to catch these opium thieves.

[Side two of the tape starts here]

There were great celebrations in Shanghai. I was out on duty on that night, and there were millions of Chinese just as thick as your fingers all around you. I was in them and everything was quiet. I remember that very well when we were parading the streets that night.

Donald R. Lennon:

As part of the Shanghai volunteers, this was the closest you all came to witnessing World War I, was it not? This was the most effect that it had on you?

Quentin Gregory:

Yes. The Germans were fighting out there too. They were trying to disrupt the shipping, you know. I knew the Captain (I can't remember his name) and he got on a German destroyer called the Embden. Every British ship that he would overtake, he would sink it on the route from Shanghai to Singapore to India to the Suez Canal. He was a terror there. He had been a captain on a ship there and he knew how to get away. For about a year there, the shipping was terrible on the account of this raider.

Donald R. Lennon:

You broke all relationships with all of the German element in China during the war then?

Quentin Gregory:

No. We did not break relationships with them. This particular incident with the German raider was on the outside, on the ocean. I noticed one thing while I was over there, the Chinese had a habit where the man would build himself up to be a brilliant soldier or leader and they would assassinate him. They did that to a lot of men during the war. All the good men they were trying to kill off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think this was part of the reason that China could not get itself together as a major power for so long?

Quentin Gregory:

I don't know why that was. There were factions there. There were viceroys here and viceroys there. They had many factions against each other. I remember that I was down a hundred miles below Peking, at a place called Shihchiachuang, and we, six of us,

were living in a great big hotel built for a railroad junction place--we had our living quarters there. General Wong (?) had charge of about fifteen thousand troops there. They sent a messenger down from Peking to promote him. The assassin handed him the scroll with the notice of promotion, and then shot him-- killed him. There was a great riot

there--all those fifteen thousand troops. We were scared to death, for we thought they would come to get us. As a matter of fact, about a hundred Frenchmen lived in that compound and ran that railroad that I was telling you about. We talked to them and they said if we wanted to come over, they would protect us. But, as far as coming over to help us, they could not do that. So, we barricaded our doors. As a matter of fact, we had gotten in some money--about ten thousand dollars in hard silver. We took that and carried it up into the attic. But, they didn't bother us. You will find pictures in there where they had cut-off some heads right in front of my house. I had my glasses on and looking right at them when they cut-off these heads. An American friend of mine standing right next to me said, “I'm about to faint.” But, it didn't affect me that way. The ones that had their heads cut-off had been doing a little looting, that's all they did. But, the whole city was in. . . . They burnt the city.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any particular reason why they cut their heads off right in front of your house?

Quentin Gregory:

No, I don't know why they picked that place. There was an open space in front of us. I remember one fellow, they made him kneel down like that, took his queue and they pulled it over like that, and then they whacked his head off with a great big sword. One of them moved his head just a little, and he missed his neck and cut through here. He cussed the dead body and took his sword and wiped it off by raking it through his hip. Those people would do the missionaries that way. Several times they would have an uprising,

and they would take the missionary compound. The missionaries would live out in the interior, and they had no protection but themselves in their compound. They would murder all of them, men, women and children.

Donald R. Lennon:

The missionaries were not too successful in their mission there were they? Did they socialize with you business men any at all?

Quentin Gregory:

No, not much. They were off to themselves in these way away places. They were trying to convert the Chinese. They didn't make a dent. They were there for years and years, but they didn't make a dent. When the Chinese got the upper hand, they disappeared. You don't find any missionaries in China now, do you?

Donald R. Lennon:

No. Not that I know of.

[End of Interview]