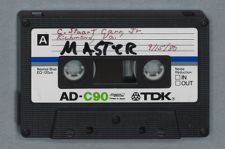

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Mr. Merlin R. Doggett | |

| May 12, 1971 | |

| Interview #1 |

Merlin R. Doggett:

I was in Yokohama, Japan, when the United States declared war on the Central Powers. That was in 1917, I believe.

Robert W. Gowen:

What took you to China? What were you going to do there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I went out with the British American Tobacco Company. British American offered me a job out there, primarily in the sales department. Then I was transferred into the leaf department. I did a lot of traveling and at one time was showing the Chinese farmers how to grow tobacco.

Robert W. Gowen:

When they first decided to send you to China, how did you feel? The idea of your going to China, did it seem like a million miles away to you at the time, or what?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I believe back in those days; that was 1917, I believe the young people were a little tougher than they are now. It meant nothing to me to start off with. . . . That brings to mind that I almost ended the trip in mid-Pacific on the way out. Well, we were on the old Japanese steamer, the S.S. KOREA MAROO. The war was going on then. There were one or two French, a Russian or two, and four of us boys going there, Americans. Also, there were some Chinese and Japanese, and some missionaries. We had left

Honolulu going into our next stop, Yokohama, when we ran into this typhoon or hurricane. It was rough. Our wireless went overboard, and some of the lifeboats were lost. The water was coming on deck and going down the aisle of the ship there, and it was about knee-deep. My cabin was down on D deck, so there got to be a little too much water down there for me. I decided I'd get a little higher up. I went up to the top deck, and it seemed that all the passengers had gathered. It looked like the fear and the roughness of that storm was drawing them close together. The first thing I saw was the missionaries over there on the side. They were singing and praying and I looked straight at them and thought to myself, if they wanted to pray and sing so much, they ought to have done that before the storm started, because it didn't look quite right getting that religious all of a sudden. I sort of avoided them. I looked over there at the bar and there were some Americans there. They were bending their elbows fast. I thought those fellows ought not to be drinking in such weather. So, I just sat down at a table by myself. There was a French countess on that boat and she had two men with her. Of course, they were close together in that corner over there, and she said, “Young man, what's wrong with you?” I said, “I'm scared, Countess.” She said, “What are you scared of” or “What are you afraid of?” and I said, “I'm scared this boat's going to sink.” She said, “So what? If it does sink, we'll probably all go to hell; and if it doesn't, we'll meet smiling on deck in the morning.” I thought if she had that much nerve, there was no use for me to be scared. So, I went over and I had a brandy with her. They had some private stock there on the boat, some Napoleon Brandy. It's the first I ever had--almost the last.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you then go into Yokohama?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, yes, we struggled into Yokohama, and the storm had been so rough on the S.S. KOREA MAROO that we were all transferred to the MONTEGO, which was a British ship, British boat.

Robert W. Gowen:

What did you think when you first saw Japan? There you are, coming down on an oriental country for the first time. What were your impressions of it as you looked around?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, the rickshaws, people, thousands, just so many, so many yellow people, speaking a language you couldn't understand. They would almost put you in a rickshaw They called it there in Japan, jinrikisha instead of a rickshaw, most of the time. On just a little short ride, man, they wanted to charge you. I remember a jinrikisha coolie wanted to charge me fifty cents for just a short ride, not much farther than where you came in. I refused to pay it; and they got rough, you know; and there are so many of them. But there was a Japanese policeman who came to the rescue and even though he was trying to be nice to me, I thought he was trying to be rough also. So, he gave me some back change in Chinese money. I think he charged me about a quarter.

Robert W. Gowen:

So, you had kind of a bad first impression of Japan?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, I didn't expect too much. The boat we were on, of course being in the storm, didn't smell very good. Those oriental steamers don't smell as good as the Canadian and American steamers.

Robert W. Gowen:

You said you were there the day we declared war on the Central Powers, in Yokohama?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I picked up the paper there, yes, and it was May 6, 1917, I believe, that the United States declared war. You see, they have foreign presses. They have just a little

newspaper right there in Tokyo and Yokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and the Philippines, all the places like that with cities of any size--they'll have their little presses. It was from that newspaper that was the first time I knew about it, when I picked up a paper.

Robert W. Gowen:

You talked about it with the other Americans there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, we talked it all over, and I got a letter saying that my brother had volunteered. I went on to Shanghai. At Shanghai after a while, I was transferred to Tientsin. I left Shanghai after about three or four days and went up to Tientsin, that's up in the north close to Peking.

Robert W. Gowen:

This was still 1917 when you went up there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, oh yes, and I offered to volunteer. The Consul General there told me, “Well, if you volunteer, we'll put you in with the Marines right here.” Well, I didn't want to do that. You know how all the kids were back in those days; it's not like it is now--they didn't want to fight there, they wanted to go. If I volunteered, I wanted to go to France. I mean, it's foolish, I admit it, but anyway, that's the way all of them were.

Robert W. Gowen:

It must have been a funny feeling for you; there you were, halfway around the world, you know, and suddenly the United States is going to war, and you're way off there. When you left Yokohama then and went to Shanghai, what did you think China was going to be like before you got there? What did you expect to find before you really saw it?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, I saw it, all at once. We came in there at the mouth of the Yangtze, and we went up the river to Shanghai. We got off the boat, and we had customs duties and things to figure out, and we didn't know where to go or what to do. We just went in there on

this launch and there was custom duty there. So, we were going to just let the customs go through our baggage and pass us on. There was a big man--I think he was a Turk--that worked for the old Astor House Hotel, and he asked us who we were with, and we told him the British American Tobacco Company. He said, “Oh, stay with us.” I was over there at the customs. He said, “Keep your hands off that baggage. They're going to my hotel.” He just worked for the hotel, you see, and they didn't fool around. He had something like a policeman's billy. It was terrible, really, but that's the way it was. So, he reached in there and took his stick and bashed it two or three times and customs officers, coolies, and everybody else just got right in there and started doing what he said to do. In just a little while, we were in the hotel and had our rooms. It was very uncalled for, what the white people out there did, and the English too; Germans were the worst ones, though. The Germans were the worst ones of all.

Robert W. Gowen:

Why?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, they'd just take a stick and walk along the street, and if a Chinaman didn't get out of the way, they'd knock him out of the way. It was very uncalled for. The English were very much the same way. They wanted to keep the Chinese down, down, down; there were so many millions of them. And that's the impression I got. There were millions and millions and millions and if they ever woke up, no other country in the world could possibly defeat them or live in their country without obeying their laws. You see, at that time, we were under our own laws in China. By treaty stipulations, we were allowed to do exactly as we pleased unless it violated the laws of our own country. If we did do something wrong, we couldn't be tried in the Chinese courts. They'd have to try us in the American consulate, which we had scattered all over China.

Robert W. Gowen:

Since you weren't under Chinese law, did you see a lot of people, being westerners, really taking advantage of this in a lot of ways? The Chinese couldn't do anything to them.

Merlin R. Doggett:

I can't say that I did, not much more than their just telling the Chinese if you don't get out of my way, I'll knock you out of the way, this kind of thing. The laws sort of in the Americans over there. . . . I think it was more or less instilled into people when they are children just coming up. For instance, you were driving a car over there and ran into a rickshaw and maybe broke the rickshaw wheels, now this is what happened. If you are driving a car over there like I have done on No. 1 Nabunda Avenue in Shanghai, and a coolie with a rickshaw just runs out like this and gets pinned up in there and he just wants to avoid running into another car so he turns around and hits my car. Well see, you can't tell exactly who hits who in a case like that because everybody is trying to avoid hitting the other one. Well, turned around, wheels may be backing up, and if you hit those wheels on the rickshaw, they'll bend just like a bicycle's, you know, same as spokes. So, the old Hindu--they come from India--without any provocation at all intended, would hit the coolie. It wasn't the coolie's fault any more than it was mine or anybody else's. They just got a little excited.

Robert W. Gowen:

Are the Indian policemen working for the British?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, the British had more influence in the charter, but that was in the national settlement there, and we had members in there, too. But as a rule, the Americans--it wasn't in their blood to act like that. That is the reason that the Chinese really liked the Americans more than they did any other country.

Robert W. Gowen:

You got this from the Chinese, that they liked the Americans more, you could feel this?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, that is right. But you were what they call Yangwese or a Dwabese, it didn't make any difference where you came from. Now a Yangwese is a foreign devil, and a Dwabese is a big nose. That big nose is what they called the Russians up there; they never have liked the Russians at all.

Robert W. Gowen:

When you first got to the country, when you took your first walks down the streets of Shanghai, what did you see? What was it like--old Shanghai?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, you'd come out of the hotel, walk across the bridge there at Suchaw Creek, go up to _________ or turn down to the right, and go down there to the British American Tobacco Company's office. It was very close to the, well, I guess you'd call it the red-light district. Now in that red-light district there, there were no Chinese, Japanese, or Oriental girls in it. At one time, the majority of the girls in there were American and British girls. Some of them from both countries were college graduates. Somebody maybe would like to dispute that, but what I'm telling you is fact. Then there were the French and later on, the White Russians came in. Some of those White Russian Girls started coming down there and the men, too, were in there. And I saw them lay it on some of those White Russians I saw leading old generals' horses down the river, or the streets at least. That was up in Pang-pu in Anhwei Province.

Robert W. Gowen:

When you first came into the country, were you struck by the poverty of people? Could you see it in the International Settlement, or did you have to go. . . ?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Poverty, poverty, poverty; and laughing--sense of humor--were all blended up together. I think people out there were about as happy as they are in most places. There

is a money proposition (?) in giving money to people, that's all; it is for the feeble-minded people. That is, if you want to make somebody happy, you don't give them money to make them happy. Instead, you give them something like a real jolly conversation or you help them talk, try to help them mentally, and get them to enjoy a real good book or something like that. You don't give people money. We're off on the wrong foot there. They call it the gap; isn't that what they call it now?

Robert W. Gowen:

Generation gap?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, generation gap, yes.

Robert W. Gowen:

You went from Shanghai up to Tientsin then, and . . . .

Merlin R. Doggett:

Tientsin and then all the way up to Peking, too, not far up there; we went up there just for, you know. . . .

Robert W. Gowen:

Up river it is about fifty some miles, I think, isn't it?

Merlin R. Doggett:

What's that, Tientsin?

Robert W. Gowen:

Tientsin to Peking.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, no, you don't go up the river there, you go by train; at least I did. Now, there is the White River, I believe it's--what's the name of that river?

Robert W. Gowen:

Tientsin River?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Tientsin, yes, I was there; and they had that big flood. Then it froze over, the whole country all around there. Of course, we had the American Concession there, called San Beguan--that means three countries--nobody controlled it at all. Well, that was all covered with water there about ten feet deep. The Chinese came together quickly and made some little ice boats. You could get out there and buy your ice boat and just take off like you were here on this river, just like you were in a little sailboat.

Robert W. Gowen:

When you got up to Peking, 1917, 1918, that whole period, you know you've got warlord fights and all the rest that's going on. What did Peking look like, the capital, when you hit that forbidden city and all this. . . ?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, it was beautiful. The things they had in there were beautiful. The lay-out of the town itself looked like it was done with precision instruments, perfect. The Chinese are not only good carpenters, but they can engineer the precision of the places and the structures they want to build. In other words, you go there and you crack in the door and look as far from here as across the river. Then look across and these gates and things where they enclose them from the far side of the river over there, they're just like one straight line. They're very intelligent people, the Chinese.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did the westerners in China at the time think that the Chinese were intelligent--you know, a German walking down the street hitting him with a stick and the Englishmen, did they realize the Chinese were intelligent or were they just coolies?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, some of the Chinese coolies, they just called them coolies. They were intelligent, too, and some of the so-called upper-class, they were kind of foolish. In other words, you get hatred in there. You get the class hatred among the Chinese as you will elsewhere in the world. It was all foolish. That is the thing. A lot of the English and the Germans were treating them like they were crazy. But they were in a favored position like we were out there and we're going to hire them. We found that by hiring them, they'll know the job or work to do; they were extremely good. In other words, it takes people over here years to train to run a redrying machine, but the Chinese pick it up just like that. This includes firing the boilers and greasing the machines, keeping the ventilation fans going and the heating coils working. They just picked it up like that.

And building a house. . . . Make a little drawing of the house--I know nothing at all about drawing except using a ruler to draw a line and take them the drawing. Tell them that you don't want the roof too steep or you don't want it level or you want it sort of like this, you know, give it to them and forget about it. They'll fix it.

Robert W. Gowen:

Was there any fighting going on in Peking at this time?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh yes, I was in. . . . That was later on, not at the very first; no, it was later on.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you stay in the Peking area?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh no, I was there for a little while, but I wanted to get out into the interior. It was too much like America there; I could go to the cinemas. It was just like a civilized country. It was a treaty port. I toldd an Englishman there, Tinken, who was the manager of the sales department in that territory, that I wanted to get out somewhere into the interior and see some of the towns. So, of course, he had to talk it over with Quentin Gregory. Quentin Gregory lives over here at Halifax. He used to be president of a bank over there. Well, Quentin Gregory was above Tinken, but Tinken talked it over with him, and a Norwegian there who was assistant division manager. So, they let me go. Well, I hadn't been up there very long before the leaf department found out that I was raised on a farm and I knew something about farming and called me. I went up into that section of Southern Manchuria, into the interior there, almost over at the edge of the Gobi Desert.

Robert W. Gowen:

You covered a lot of ground then.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, yes, that's just when I first went out there.

Robert W. Gowen:

What did they send you out there for, to teach the Chinese how to grow tobacco?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, that's why they transferred me to the leaf department. I came down to Nanchaotsi, that's in Anhwei Province. I was there for a little while, and then we went up to Shantung Province. Up there was a little place where they had a plant.

Robert W. Gowen:

Why did your company want the Chinese to grow tobacco? Could they save by buying it here, or. . . ?

Merlin R. Doggett:

That was 1919 and I'd been out there for a year or two, you see. That was between 1918 and 1919, and if you'll check on your tobacco sales over here in this country in 1919, a whole lot of that tobacco brought a dollar a pound, you know. It was high. Of course, some of it didn't bring so much, but tobacco prices were very high in 1918. In 1919, it was really up there.

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: What type of tobacco were they growing over there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, we got the seeds from over here.

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: Was it bright leaf type?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Bright leaf flue-cured tobacco. The place where they tried it was in the Anhwei Province. I don't know why we ever started to grow it in that province, because the land itself was so entirely unsuitable for growing tobacco that it couldn't be anything except a loss to begin with. Now, say west of Weishan on the Gowsee [sp.] Railway, the Honan Province and the Shantung Province have very desirable land for growing tobacco. Suchow in Honan Province, that's the best.

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: The soil and climate were comparable to what we have here?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, it was about the same thing. I think that the latitude was just about the same as it is here.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you have any success at all up in Southern Manchuria? The climate wouldn't match there.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, as a matter of fact, there's a place in Antung and that's in. . . .

Robert W. Gowen:

That's on the border?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, Antung, I think that's down in Korea just a little bit. That's not too far from Haeju or Seoul. They raised some good tobacco there. Before I went out there, we had put up some kind of plant out there. The Japanese came along and taxed us so high on it, there was nothing for us to do but get out. I know we had some people from Richmond, Virginia, who were out there with our company and were later with Universal Leaf. The J. P. Taylor Company hired a Japanese lawyer there who had run up a bill, good gracious alive, I think about twenty-four hundred yen or something like that and we had taxes on it way up sky high. They asked me to go over there and settle this thing once and for all. Well, I went over there and looked around a little bit and located this lawyer. I told him, “I came over here to settle this thing. It looks like you're our lawyer, and you haven't settled it.” He said, “Ah so.” Well, anyway, I gave him a hundred yen note, a deed to the property, all of it, and I wrote up a little contract whereby he agreed to pay all future taxes that might be claimed against this property or to pay any debts that we owed in that section that were derived on account of this property. I got back and told them about it. I didn't think I had done anything at all; they thought I had. Well, they complimented me very highly on it. You give this money away for a fellow to take our property. I never did understand it, but our company thought I had made a good deal.

Robert W. Gowen:

When you went up to Southern Manchuria, you were going into the territory where Japanese were all around. Did you get the feeling at that time with that

property and later on that they were really trying to drive you out, drive westerners out of Southern Manchuria? Were they trying to interfere with you?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, there weren't enough of us white people up there. I think probably our press back here and people in their travels out there talking to people that go to the clubs and so forth, you know, were given the impression that the Japanese wanted to run us out. I think it was no more people over there and no more of the business than we were getting in South Manchuria. I think the Japanese were just, you know, just sort of waiting to--as long as they were doing all right, I don't think they were trying to be too hard on us. It depends a great deal upon the individual and what you know and how you know about getting along with those Orientals. If a man has a rather important job with the Japanese government, then he has some rules that he has to live up to. You, being an American or British, can't go out there and start to raise some cane with him because you make him lose face, you see. To an Oriental, even death itself is no worse than losing face. They can lose so much face and then they just give up and die.

Robert W. Gowen:

How did the Americans and British look at the Japanese? We know how they looked at the Chinese. When you got to Manchuria, there were a lot of Japanese officials around. How did they look at the Japanese?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, let's put it this way, I think they really, truly liked the Chinese better, but they respected the Japanese a whole lot more than they did the Chinese, because the Chinese didn't respect themselves, you know, and so they couldn't expect other people to.

Robert W. Gowen:

The Japanese really didn't bother you. Now we're talking about what, the 1920's, I suppose, late teens, early 1920's.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh well, some few instances in there where we were. . . . More especially if you didn't show him the respect he thought he was entitled to. In other words, if he said he was going to arrest you, you would go ahead and make the thing easy. This way, you would get off all right, you see. Suppose he calls some friends, you see; you get a few Japanese friends to come smooth it over real good, and you might get out of it. But if you start acting big like you owned as much of the country or more than he did, saying the United States government wasn't going to stand for it, or something like that, then the Japanese would say, “Well, let's see what your Uncle Sam will do.” I got mighty mad at the Japanese, myself, but after cooling off a little bit and thinking it over a little bit, I could see where I would probably cause him to lose face instead of trying to help him.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you see a lot of Japanese? Were Japanese troops in Manchuria then? Were the Japanese troops conspicuous; could you see them easily, or were there very many Japanese troops around?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well yes, they were around there and most of them were in Darien.

Robert W. Gowen:

They had a base down there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, that's right, Darien. You'd see a few Japanese troops but not too many.

Robert W. Gowen:

You came back in 1931?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh no, I came back in 1921. I went in 1917 and came back in 1921. I stayed over here about three or four years, and then I went back in 1925, but I went back with the Universal Leaf Tobacco Company of China, Inc. They wanted some old China hands. Philip Morris wanted some, too.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you stay there another ten years then?

Merlin R. Doggett:

That's right.

Robert W. Gowen:

Then came back for good in 1935.

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, no, I came back every three or four years.

Robert W. Gowen:

When did you finally leave China for good?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, it was 1935.

Robert W. Gowen:

1935?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes.

Robert W. Gowen:

Long time.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, the Communists were getting started out there. At one time there we had a little old redrying plant I had put up with just one machine in it. I had it over across the river, and they got to breaking in over there and stealing stuff. So I just rented a piece of ground there from a tobacco products corporation, and there was enough ground there. I built, of course, little offices and then a hanging room and a redrying room. We had been pressing it and making our cooperage down there--making the hogsheads and so forth--and pressing the tobacco into the hogsheads and heading them out. And we had storage, too, there; a good big building. It was a redrying plant with storage. It was small, you see, because instead of having two machines, we had only one. Well, the Chinese we had down there got to acting up a little bit. I noticed this one that kept watching me, kept causing trouble all the time. He wanted more money, more money, and so forth. He was a little old fellow, little bitty old Chinese--head as high as that door there--and I went down there and grabbed him and brought him up. I told Mr. ________, a Chinese down there at the time, I said, “Pay this fellow and get him out of here.” Well, I knew I was going to have trouble. I threw him out and told him not to come back and then I went right back in there and raised the salary from small money to big money. Now, big

money means you got one hundred cents to a dollar as opposed to small money where you got probably one hundred and forty or fifty cents to a dollar. So, I gave about a thirty percent increase there. I got in my company car and was going back up to the office. There was a picture of a man running just like that and this little Chinese, the one I fired, I reckon, was out there with a gun like this, bang, bang. It was also getting different up in the interior. You could feel the thing coming on; Communism was going to take over. Some of my Chinese were not trained and they used to tell me, “That don't sound so bad.”

Robert W. Gowen:

When they heard about Communism, you mean?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes.

Robert W. Gowen:

Where were you at this time?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I was in Southern Manchuria at this time, I mean, Shantung.

Robert W. Gowen:

When this happened?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, the shooting was in Shanghai.

Robert W. Gowen:

Oh, in Shanghai.

Merlin R. Doggett:

I was in Shanghai then, and we had built a redrying building. Then I worked over across the Woosung River from Shanghai. Now, you've got the international settlement there, and then you've got the Woosung River coming down like this, and over on the other side of that is Chinese territory. We could rent land and stay in there for a little while, but we couldn't own any land over there. So, they had some robberies over there. I know they robbed, threatened, and everything else. The Americans lived closer together and they'd stick out and help one another. Now, there I was, and I didn't have a big position with the company. I didn't have high standards of living or any education to

speak of except high school and a term of college. I figured that something had to be done or they were going to run us out of there. So, I went to see Cunningham, our Consul General in Shanghai. He was above all the other consuls in China and he said, “What do you want to do?” I said, “We've got the Navy here with three or four destroyers, and the Admiral's ship. We'd best get some protection; that's all I want.” He said, “You go see the Admiral.” I hadn't ever been to see an Admiral in my life. I didn't want to go quite that strong. He said, “You go see him.”

Well, I went out and got a little sampan to get up there. I went over there, got off, and went up on deck, and they asked me who I wanted to see. I said, “I want to see the Admiral.” Well, you know, it's a good thing they didn't ask me who the Admiral was; I couldn't have told them. I got in there, and I still don't know his name. He had a Southern accent, and I found out a little later on he came from Kentucky. He said, “Yes, they robbed you, huh?” I said, “Yes, they broke into British American.” Of course, that wasn't exactly his way of doing business with the English, but he didn't mind helping the English out, either, you know. I said, “They threatened us and broke in. A couple of nights ago, they broke into our place and then last night, they broke into British American and stole a lot of tobacco.” I said, “They threatened us again.” He said, “Have you got any place over there?” I said, “I've got a little bungalow over there.” He said, “Can you take care of thirty Marines?” I said, “Yes, but I don't think we need that many--about fifteen would be plenty.” He said, “All right, in case you need a little more, have you got any place there like a jetty where you can tie up a destroyer?” Good gracious alive, things were going fast for me and I told him, yes, we had. And you know, it wasn't any time before he put those Marines over there. I had a redrying man by the name of Chalbert?

and he and his wife lived in the little bungalow. So, I pulled them out and sent them over to a hotel there in Shanghai and put those Marines in that place and they brought up that destroyer; it was just like parking an automobile. All of that was done just like this.

Robert W. Gowen:

No more robberies after that, huh?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, and you talk about somebody having face. If I could go to the United States government and get that much help just like this, . . . . I had more face, good gracious alive.

Robert W. Gowen:

I don't know exactly how to word this, but you were talking about growing tobacco up there in the interior. The big savings factor here would be in labor, would it not? I'm sure there was an abundant supply. How were the wages of the Chinese you used?

Merlin R. Doggett:

The labor at the time would run--well, this is after it started getting better with higher wages--around eighty cents to a dollar. That would be a day, and that would be Chinese money. Now, at that time, the Chinese money would run about, . . . . oh well, let's say, four to five of their dollars. And you see, you would pay them as much. Of course, at that time labor wouldn't be but about fifty cents an hour wouldn't it? That is terrible, you see. The tobacco would sell for around. . . . We'd buy it for an average of, say, forty-five cents in the Chinese money. Now, you'd have to pay some tax on it in shipping it out from the provinces into Shanghai, but those taxes wouldn't run over three cents a pound.

Robert W. Gowen:

Transit taxes, license taxes?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, license taxes. You can call it license taxes, if you like. I haven't heard of that word, or thought of it in a long time. Yes, call it license taxes. Then, it got so they

were charging you to ship in by bus or by Jordin and Matheson. They were sort of putting the pressure on them, taxing them kind of heavy so that their customers would rather ship by China merchants.

Robert W. Gowen:

Was this in the 1930's?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, that was happening, just coming on a little bit.

See, you go out there to buy tobacco, and you've got to build a warehouse to have a place to pack it up. You've got to build a bank out there, and then you've got to hire you a banker, and you have to pay off this money. To hear it, it sounds like it's complicated, but when you've got good labor to deal with, it's not complicated at all. It works very easy, very smooth.

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: Were they growing any tobacco out there before the Americans and the British companies came in and started developing the tobacco industry?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I guess China has, for the last hundred or so years, been the big producer of tobacco in the world. A lot of tobacco is gown in China, but it's known as Chinese tobacco, down in Canton they call it that's tobacco. And they have about twenty-five different species of tobacco. It's not suitable for this country. We did bring in a little bit at one time during World War I. We brought a little bit in to take care of tobacco we couldn't get from Greece and Turkey.

Robert W. Gowen:

Purely for the Chinese market?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, we'd sell a little in Germany, Hong Kong, and Holland--they do sell a little of this tobacco.

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: Is this primarily the cigarette tobacco, or is it cigar, pipe, chewing tobacco. . . ?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Pipe, I think it was mostly. They had these little pipes there, and they'd put it in their little bags. . . .

Robert W. Gowen:

Lennon: But what you were experimenting with growing; was that also pipe tobacco or was that cigarette?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, it was cigarette, all cigarette.

Robert W. Gowen:

No money in pipe tobacco.

Merlin R. Doggett:

It was practically all cigarette. In those three places they got it, from up there in Korea is about the best cigarette tobacco they grow out there. Then tobacco from Honan Province, halfway between Peking and Hangchou, right along in there, is the next best. Shantung Province is also good. Nanchaotsi in Anhwei Province, just forget that; that is no good.

He was my number one Chinese, and he was paying off, but he had some family trouble or something. I don't know what it was. The Chung family were robbers, really. What I tried to do was make him use his own money, you see, and then pay him after he'd used up his own money. But, he got to buying along right heavy there at one time, and he wanted some more money. I let him have a little more money, and the old fellow stole six thousand dollars from me. I asked him why he stole it and he said he just needed it. His relatives there just wanted some money. He just had to have it. Well, that was an experience I had with him. They don't want to listen to you, I'll tell you that.

I remember the execution of six bandits in Pungpo. That was in the fall of 1925. They brought them up there in rickshaws, feet tied together, hands behind their backs. They were all placed kneeling with their heads bent over. And that old executioner came along and cut their heads off. Now that--there was no point--that's just something they

did. They had them doped up. I saw several more that had just had their heads cut off. That is just a favorite pastime over there to cut heads off. But I'll tell you, they have to do something.

Robert W. Gowen:

They can't put them all in prisons, huh?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, no, the idea is, of course, that they don't particularly like to cut a head off, but if they do kill people like that, they will leave an impression with people of what will happen to them if they do wrong. So, they take the head and put it up, hang it on the gate post, and let everybody come by and see it. They keep it up there for a couple of days.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you see anybody run out with rolls and dip the rolls in blood after the execution?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, I've seen the crowd start applauding, clapping their hands, when they cut their heads off. I guess it's like Babe Ruth knocking a home run. Yes, I've seen that several times. I have been right up there close to them. They cut their heads off like that and the heads drop off down on the ground, you know, like a chicken with his head cut off, and he will jump around. I've see this muscular reaction when the head is grinding up, chewing up the dirt and little gravel and things like that. Of course, he didn't know what he'd done, but that's what happened.

[End of Part 1]

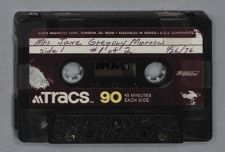

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Mr. Merlin R. Doggett | |

| May 12, 1971 | |

| Interview #2 |

Merlin R. Doggett:

It just spread and spread, and the Chinese say there is such a thing as losing face. Our government has lost face, no question about that. People that we have been helping for years and years have just said, “You have helped us about as much as you can. We will get somebody else to help us now.”

Robert W. Gowen:

Well, I thought we might start off things with what you really want to talk about more than anything else, and that's the law, courts, and the legal situation.

Merlin R. Doggett:

I would. Have you ever heard the story or read the story over here about the four lawyers that had sons, and they graduated the same year? Well, these lawyers had gone to school themselves for years together. They were top lawyers, and they had four sons to come along, and they all graduated the same year at Harvard. Have you heard the story?

Robert W. Gowen:

No.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, they graduated there at Harvard, and their fathers decided the best thing for them to do before they started to practice law was to take a trip around the world. Three of them were from the east coast and one was from the west coast. So they met over there on the west coast and got on a steamer and went into Shanghai. When they got to Shanghai, they became so interested in China that they decided they'd go up into the

Interior and see what it was really like in the Interior. So, they went up to a city within the Interior and rented a temple up there just to live in--all of these cities have temples--and went out strolling, walking around, and found a cat. Well, they had a few mice in this temple, so they picked up this cat and brought him back. Being of legal minds, one brought up the subject, well, what part of the cat do you own? They wound up with one saying he'd take the right front foot and the other one, the left front foot, one, the right hind foot, and the other one, the left hind foot, or leg rather. Well, the cat got after a mouse and was chasing the mouse around the temple and knocked over a lantern they had in there for light and spread kerosene oil all over the floor and broke his right foreleg. So, they took a little kerosene that was spilled there on the floor and a little more from the lantern and wrapped it up, well, taped it up good with splints. Then the cat, being a very good mouser, got after this rat and ran around some more and knocked over another lantern there. It caught on fire, and it spread all over the temple there. It caught on fire, and it spread all over the temple there. The wind came up high, and the fire spread from the temple to the village and burned up several houses. Well, this little village had a head man there who went to the Hsien Court and asked if he could make them pay for it. He said, “Oh yes, bring them around; we'll have a trial.” So, he brought these four young men around there, and the trial proceeded. The magistrate there of this Hsien Court asked this boy, “Do you admit owning this right hind leg?” He said, “Yes.” “And that was the one that was broke and taped up with kerosene?” And he said, “Yes, sir, I own it.” And he said, “Well, the damage done to the temple and the city is very conservative at $100,000, so you'll have to pay $100,000.” Now, all of these four young lawyers were bright, so they asked this magistrate there at the Hsien Court if he could appeal it. He

said, “Oh yes; go to the Fu Court.” So, they appealed it to the Fu Court. This judge listened to all the evidence. He asked each one which leg of the cat he owned. When he got through, he looked at them all, and he said, “I'll tell you, that magistrate down at the Hsien Court, he was right about one thing--the damage was $100,000, but this boy here that said he owned the broken leg, he's innocent. If it hadn't have been for the three good legs, the cat couldn't have run all around the temple; and if he hadn't have run around the temple, he wouldn't have set fire to it, and there wouldn't have been any damage done at all. But to you other three here, you can pay your $100,000.” Now, that's what Mr. Nixon's kind of thinking he's going to run into when he gets over there talking to Chou-En-lai.

Robert W. Gowen:

What were the courts like and the legal problems for foreigners who were over there? What did you run into there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, I have another true story to tell you about the courts out there in China. It was at a time when our two countries had agreed that Americans could not be tried in Chinese courts. Those in the Interior, to be tried, would be tried if the Chinese wanted to, at the American consulates scattered all over the country. One time I was accused in a court; and I asked them if they were accusing me in that court, and they said, yes. So, I got up immediately and told them that they did not have the authority to try me in that court, that our countries had agreed that I could be tried at the American consulate only. I left. I hadn't gotten very far out of the court before they brought a Chinese man in a rickshaw all shackled up, outside to the road there as I was passing by, and they shot and killed him. I guess they were doing it for my benefit, I don't know.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did you ever go into a consulate court? Were you ever involved in anything. . . ?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I'll tell you a story and I'm just going to tell you as my own experience. I was out there with the tobacco company, up in Shantung Province, where we had rented a place. We had a ninety-nine year lease on it, which I didn't think anything of; it was too long. We had as a banker up there, a Chinese man by the name of Chung-Foo-Tong. Now, Chung had lived too close to the Gobi Desert for years, and he had sucked so much Gobi Desert dust into his body, and lungs and it spread to his brain. Chung was just on the dumb side, but he was loyal and did what he could. I kept him on as our banker. We had to have a little bank to pay off the farmers when we brought tobacco. So, Chung did a very good job for awhile, but he had relatives that were... Well, if they weren't exactly bandits themselves, they were mixed up with the bandits. So, Chung kept getting a little short, and I'd give him a few days to make it up and tell my comprador to be on the lookout for another banker because it looked like Chung was not going to hold out very much longer. So, I walked out one morning and I saw a lot of farmers standing around with their little slips to take to the bank to get paid for the tobacco that we had bought. I sent for Chung immediately and asked him why it hadn't been paid. He said that he was a little short; the money hadn't come in. He had sent to Tsingtao for it; I'd given him a check in advance. Well, the money didn't come in, so I sent for the magistrate over there at the Hsien Court and told him that it looked like Chung had stolen some money from us. He said, “Well, he can fix that, I guess.” He said, “Give him another day to get it up.” I said, “I'll give him two more days.” He said, “All right, fine.” I gave him two more days and he couldn't get the money. So, I told the magistrate he had stolen $6,000,

and we couldn't get it back. We wanted the Chinese court to handle it and get as much of it back as he could. So, the magistrate said he'd see what he could do. In the meantime, he sent some soldiers over there to guard the place so Chung couldn't run away and I was stopped from buying tobacco. The magistrate sent over and got Chung and carried him over to his little jail, this little Hsien. It was at a place Changtien, but we didn't have a court there; it was at Tsingcheng, a little west of there. They took him over there and the weather was getting cold up there in Shantung. We were back up in the Interior, not too far from Tsinan-fu on the Gowsee [sp.] Railway. So, the magistrate talked to him a little rough and said, “I'll get your money for you.” They locked him up in jail and the jailers there, as is their custom, demand money from their prisoners. So, they demanded some money, and Chung wouldn't pay them anything. So, they wouldn't give him any bedclothes. I knew nothing about this. The old fellow froze to death in jail. He wasn't really such a bad fellow; his family brought this on him, but I felt very sorry for him. The magistrate sent for me to come over there, so I rushed over there. He said, “Well, the old man died.” I said, “What was the trouble with him when he died?” He said, “He froze to death.” He said, “He wouldn't give the jailer any money. They wouldn't give him any warm clothes or a bed to sleep on and he just froze.” And I said, “Well, I'm mighty sorry to hear that.” He said, “Well, what are we going to do? What can we do about this--what can you do about this?” he asked me. I said, “Well, I don't know.” I said, “In our country, when a person dies, we bury him.” He said, “Well, his family doesn't seem to have any money. None of them seem to have any money and being as he's been with your company for eight or ten years, would you bury him?” I asked, “How much does it cost?” He said, “Well, it costs $100 to $200.” Now that's Chinese money, so, I said,

“All right.” I told my comprador there, Chou-Han-Ching, “Give them a couple hundred dollars to bury him.” So, I gave them $200 to bury the old fellow. I thought it was all over, but about two weeks later, the magistrate came to see me. And he said, “That old fellow's got a lot of relatives, a lot of influence over there around Weihsien, and that was just about enough to hire the mourners.” And I said, “Well, it looks like to me if our company has lost $6,000 and paid a couple hundred dollars to bury this old fellow, that ought to be enough for us to lose.” The magistrate said, “Oh, he's been with you a long time.” He said, “He's made money [for you] up here, and this is the only time he's really ever stole from you.” I said, “I just want to get out of the thing anyway.” The old fellow froze to death over there, and I put him in the jail, so I said, “How much more will it take?” He said, “Well, I think $300 this time would be plenty.” Well, I paid the $300; low and behold in a week's time, he came back and wanted $400. So, I got the comprador in there and some witnesses, and they got the old magistrate to say that would be the last of it; I'd never hear about it any more. So, I paid him another $400. Well, our company was very reasonable about something like that, I mean, anything I wanted to spend, I could spend. Chung's wife and son and son's wife moved in and took possession of our place we had rented there at Weihsien. We had rather a nice place there for buying tobacco. I didn't use it because I didn't like the quality of the tobacco grown around there. I liked it in the west, farther up in the hills there towards Tsinan. Well, they started to raise the dickens. The old woman found out that there was nothing she could do, so she went out there and jumped in the well and committed suicide. Then her son and son's wife, they by that time had found out it was kind of easy to get money out of our company, didn't attack us directly; not me directly, but they accused my comprador,

Chou-Han-Ching, of throwing this old woman into the well. Well, there was no truth in it. I was in Shanghai, when my comprador was arrested. He was at Changtien, along the Gowsee Railway there, and he was taken into Tsinan-fu[?]. He bribed the men there, so the jailer there sent me a telegram which said he was arrested and please come immediately, his life depended on it. I jumped on the train and went up there, and I went in to this yaman. I found he had his trial and had been sentenced to death by the Fu Court. In executing those orders, they had several of these prisoners to execute in a truck. They would take anywhere from three to five of them out to the execution grounds, shoot them all except one, and bring that one back and put him in there. Chou had been out there twice, and he didn't know whether he was going to be shot or not. When he saw me, he ran up to the prison fence. Well, it was cold; the ground was frozen. He dropped down on his knees real quick, kowtowed, and slammed his head against the hard earth. It sounded about like you'd take the flat edge of a hatchet and strike a board. Well, they took him on back. I hollered and told him I'd do what I could. So, I went to see the old--what would you call him--he was the head magistrate there, the judge of the Fu Court. I told him I was up there on behalf of Chou-Han-Ching, who had been accused of murdering this old woman and he said to me, “Have you come up here to interfere with our courts?” I said, “No, how can you talk like that?” I said, “What kind of talk is this?” You know how you'd say that in Chinese. So, I told him I wanted an interpreter. I said, “I have come to see if I could help Chow-Han-Ching. If I can help him, I'll help him; if I can't, I must go back to Shanghai. But, I've come only...;” and I couldn't remember the word “witness.” I didn't know what the word “witness” was in Chinese; I just didn't know. Anyway, I told him, “I've got to have an interpreter.” So, he brought me a lyoung

kid. I asked him what “witness” was in Chinese, and I talked to him in Chinese just the same thing as I told the judge. “I am up to help him.” Oh, he grabbed that word “witness,” and he told the court about it. It seems that he just then recognized this young kid, who was probably a very close relative of one of the high courts there, that I had shown him some face, and he turned to my help immediately. So, they asked me about this property down there at Weisien and I told him that the Chung family had no right to be in there at all. We had it leased. He wanted to know what Chinese name we had it leased under, and I told him, Lo-Ming-Chung. He asked me to describe him. He said, “The Chung family claims there's no such person as Lo-Ming-Chung and never has been.” Well, I knew Lo personally and I described him as a very short, small Chinese who wore very thick eye glasses. He told me to go back to Shanghai and get Lo-Ming-Chung and bring him up there. Lo was a wealthy Chinese. He wouldn't go, but he sent his younger brother. So, I took his brother back up there with me. According to Chinese courts, you're more or less allowed to do something like that, but you're talking about those officials up there in the court. They gave him a fit and told Lo's younger brother to go with me back to Shanghai and get Lo and bring him up there. They told me I wouldn't have to come unless I wanted to. Well, Lo's younger brother got him and took him up there. I think Lo gave them the property up there; we didn't want to use it anymore. None the less, I really don't know what actually happened to our property we had there in Wehsien, but I do know that they turned Chou-Han-Ching loose.

Robert W. Gowen:

Was it after they got the property?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, that was before they got the property. They turned him loose after I got through testifying up there. And I used this little young fellow here as the interpreter.

Well, he knew a whole lot more about the court than I did. It seems that the whole court turned in my favor when I told them about Chou-Han-Ching. This was his brother. Everything just turned my way. They turned my comprador loose, gave him a clear bill. So, that left us out of it, and we never heard anymore about the case. Needless to say, we lost our $6,000. The court held, I think, that a ninety-nine year lease was like ownership and that we were not allowed to have a ninety-nine year lease on property up in the Interior. I think that was confiscated. It was no good to us, anyway. But the other places I had rented up there--I had three other places I had rented myself for the company--were rented on a thirty-year lease.

Robert W. Gowen:

Would you get a Chinese to rent it--well, you could rent the land, couldn't you?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, I rented it myself. I don't know whether it was legal or not, but I never ever fretted over it.

Robert W. Gowen:

When did all this happen, late 20's?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, now the first year I was there was the fall of 1926 when I first went up there. 1926 and 1927, I didn't have any trouble. Chung's relatives, that is the gangsters, were his relatives or bandits, started closing in on him in about 1928. I think, yes, I think it was about 1928 or 1929.

Robert W. Gowen:

Shantung Province is known for bandits, anyhow, up in the hills there. They have a lot of them up there. At that time, in the late 20's, the U.S. and the other governments were thinking of giving up consular jurisdiction, huh? What did you people in China feel about it at the time if you had to go into those courts as you've been telling us about?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I figured I wanted plenty of money to spend if I had to. That's the way I felt.

Robert W. Gowen:

Were they really corrupt, the courts?

Merlin R. Doggett:

I think some of the courts were corrupt, and I think some of them were very good. Now, you've heard, of course, of Fung-yoo-Shan, a Christian general in Shantung Province. He would go around over his province, which is Shantung, and appear in person at the trials with many of the magistrates not even knowing he was there. He would go to the Fu courts the same way, dressed up like a coolie, more or less, and just go in. He ran into one court down close to the Anwhei line, I believe it was, or the Kiangsu line, I don't remember which one or which place it was. But anyway, it was not over about a hundred lei--which would be thirty miles--from the boarder of another province. I remember this story because my comprador told me. He said he ran into a situation down there that was so common. They were having trials for families there that were all mixed up in adultery with the various wives and kinfolk. They say Fung-yoo-Shan listened to that thing for just a little bit, then he got up and told the magistrate to get out of the way, he'd take over the court. So, he looked at them, all of them, and he said, “It's one hundred lei from here to the boarder of the next province. If you haven't crossed to the province by tomorrow at sun-up, I am going to cut the heads off of every one of you. I don't want people like that in my province.” I never heard any more what happened to them.

Robert W. Gowen:

Did they still order public executions when you were there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, yes, the public executions were the thing when I was there. The deed itself was considered, more or less, a minor event; you're just cutting off a single head. They wanted to accelerate the impression that it would give the general public. That's why

they used to, back there, even years ago, take an old head of a person that had been executed and stick it up on the gate post that comes into the city so everybody could see, coming in and going out, what had actually happened to people that violated the law. Six heads were cut off the whole time I was out there. I saw several more that were cut off, but I didn't see the actual knife go through the neck.

Robert W. Gowen:

What was it like? Tell us what the public executions were like. Did they bring them in the cart and all this kind of thing?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, they went to bring them out of the jail. They usually pick out a large open space within the city if they could find it in the city; if not, around the edges of the city. Most of the places, if there was any size to the city, had what they called the execution grounds. They would let the word out that there would be an execution and the people would come in from all around the city and countryside to see it. They would gather around there. The old executioner was a highly respected man that prized his job and, incidentally, got paid very well for it. He'd come out with his knife. He had an execution knife about that long with a handle on it about that long. It was a blade, more or less, rather than a knife, really. He'd come out there right after they brought in the people, the thieves or bandits to be executed. They'd bring them in rickshaws. Now, they would have their feet shackled and their hands would be tied behind their backs. They would bring them in--two men to the rickshaw, one pulling--and then put the rickshaw down. The rickshaw coolie would come and help this man running along with him. They'd pull him out and put him erect on his knees and then space them on up--the six that I saw were spaced at a distance, at a space as far apart as from here to that tree out there, say, forty or fifty feet. As soon as that was completed this old executioner would come out in front of

them. They could turn their heads and see. He'd take that sharp knife and run his thumb up on it just like that, just as if he had his job to do and he wanted to be sure that his knife was very keen. All of these bandits knew that if you jerk your head or try to get out of the way of the nick, that he'd just chop you up bit by bit until he killed you. It was much more painful than to take your medicine. So, he would run up behind the first one and run up behind him, then he'll--whack!--come back out just like that, and that head comes off. Now, that body is so tense or something that it stands up there for just a second or so and the blood comes out of the jugular veins sprays up just like a fountain. Then he's right behind that one and up to the next one. He cut five of these heads off, and then that sixth one, he couldn't quite stand it. He cut down like that, and the knife turned up into the jawbone and didn't cut his head quite off. But he rolled him over and kicked him and cut it off, anyway. Now, that is a terrible sight to see. The Chinese, and I would say that there was a couple of thousand people standing around watching it, everyone had to see the heads cut off from the first to the last. They'd start clapping just like that, terrible sound. I think that I told you before that they'd clap just like Babe Ruth had just knocked a home run.

Robert W. Gowen:

At that time, they didn't try to do this to foreigners, did they? They wouldn't threaten you with execution, would they?

Merlin R. Doggett:

They wouldn't what?

Robert W. Gowen:

They wouldn't threaten you with execution. I mean, they can't by law; but somebody might say, you know...

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, no, it wouldn't be public executions. That would be too much. I mean, the Chinese would kill you, but it would be sort of as bandits. They wouldn't kill you with that much notoriety.

Robert W. Gowen:

How about torture in the courts? You hear a lot about torture in the old Chinese courts and all.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, yes, that's true. They have a lot of torture. Of course, we all know that one of the most painful they tell me--I've never see it--was when they took a victim and greased his backside and put him over a growing bamboo shoot, insert that a little ways up his anus, and fertilize it. It grows very fast. They say that is the most painful, but I've never seen that.

Robert W. Gowen:

But they were doing that when you were there?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, yes, yes, the Chinese referred to it. They had another one, and I've never seen this one. It was what they called a thousand cuts. You could cut a person a thousand times before he dies, cut him in a thousand different places. I've never seen that. I remember in Pengpu, Anwhei Province, a province where the Chinese were really cruel, I was coming along the street there one day, coming from my work to my office. There was a Chinese bandit that had been executed right in the center of four blocks there, in the center of the street. I looked at it and it was such a gruesome looking thing, I decided I'd take my Kodak down there and take a picture. So, I told my rickshaw coolie to hurry along. As soon as I got home, I grabbed my Kodak and went back to the place. He was still there. I got out, and they had a soldier guarding him, or staying there with him till they got ready to move him or something. So, I asked him in the best Chinese I could if I could take a picture of him. I had my Kodak, but the soldier had other ideas. He thought

that Kodak was a little case where I carried my surgical instruments. He was firmly convinced that what I wanted to do was to cut out this bandit's heart and eat it to make me brave. I tried my best to explain to him, but there was such a little distinction between heart and picture that I thought it was best for me to make a hasty retreat. I went back and got my interpreter down in Penpu and he went down there and told him. By that time, I didn't even want a picture of the place anymore, so I let it go.

Robert W. Gowen:

Were they still using the cages when you were there, you know, they put the prisoner's neck up to here and take the rocks away from beneath his foot inside the cage, that kind of stuff.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, they used it in some places, but I never saw it. Now, at the jail there in Shanghai, the Ward Street jail in Shanghai, where they put so many prisoners, they caught so many of the prisoners there in Shanghai, and in the British concession, the French concession, and the Japanese concession, that they just loaded up their jails down there. They kept them in cages, but I never went inside to see them.

Robert W. Gowen:

You put all that together, though, the torture, the bribery, it must have made you very nervous. You know, people from America, the West, it must have made you very nervous as foreigners to be in China in the late 20's and talking about getting rid of extra territoriality and the like.

Merlin R. Doggett:

Yes, that is true. On the other hand, so many of us had friends among the Chinese. We had lived and set ourselves as examples of good citizenship, not only for ourselves, but for the Chinese that worked for us and with us. We were not anxious for any bad reports whatsoever to even find its way to even our very smallest consular offices in the Orient. Most of the foreigners out there wanted to set examples, I think, more or

less than anybody else. Unfortunately, I guess at that time I was out there, it was the business people and the missionaries. The missionaries and the business people did not associate but very little together. The missionaries, I think, felt like that if they would associate with the business people that they would be accused of drinking, gambling and racing. We business people out there, we gambled on races; we gambled at our clubs, bridge and poker; and we even used our clubs as racetracks where people could gamble on the races right there through our club, that is, members of the club. So, the missionaries didn't think much, I know, they told me so. The missionaries told me. I went to spend the night with a missionary, Lutheran missionary, up there in Honan Province. There was no place to stay out there. The British American Tobacco Company had a beautiful plant there; it was all destroyed by fire, and the soldiers had taken over in Nanyang. So, I asked them if I could stay there. I had an interpreter with me who was educated at one of our colleges over here in America, really a highly respected Chinese. But do you know those missionaries wouldn't take us in? I said, “Well, I've always given a little money to churches and missionaries and so forth.” This older fellow said, “We don't approve of tobacco. They're growing a lot of tobacco around here--they should be growing other things like soy beans.” He said, “I'll ask my wife and see what she says.” He came back over that thing three times, said he didn't approve of tobacco, but he'd ask his wife and see what she said. He came back over it again and then the third time he came over it, I said, “I'll tell you,” I said, “You tell your wife to not say anything, because I couldn't accept your hospitality here if you offered it.” So, I left. Yes, it's funny how people think.

Robert W. Gowen:

There weren't very close relations then between you business people and the missionaries. It was just, you know, two different worlds. The missionaries were in the Interior, weren't they?

Merlin R. Doggett:

No, well, they were Interior and in the big cities there. I met some very fine, nice missionaries up in Tsinan-Fu [?]. Now, the doctors' side of it, the missionaries, now that side of it was they were very fine people, and we like them very much. We did everything we could to get along, but you had narrow-minded missionaries, well, you know, religious fanatics.

Robert W. Gowen:

What did the Chinese think about that type of missionary?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Oh, the Chinese knew. They just said he is talking to his god. What can we get out of it? You know, there was a preacher, a Presbyterian preacher out yonder in Fayetteville, Tennessee, who asked me that same question. He asked me what the Chinese thought of the missionaries out there, and I told him, “I'll tell you what, I'll give you the same answer that some of the missionaries had given, that is, they hope to have better success with their second generation of Christians.” Well, this preacher fellow, Clark, he went to the First Church in Nashville from down there at Fayetteville. He got up in the pulpit, and when I was at church, he lambasted me. I mean he put it on. He said, “Who is this layman who would answer such a question? I say unto you that if all of our missionaries out there, save even just one soul, it's well worth our undertaking.” I don't believe any such foolishness as that. But, he lambasted me. They had a real nice church there. It had wide steps, all marble steps all the way across the front. When I started out of the church, there was the Presbyterian preacher shaking hands on the steps and going from one side to the other and trying to catch everybody coming out. When he

saw me coming, he got over on the other side. I waited and I waited and I waited; he wouldn't come back. So, I went over to the other side, and he started back. I came and I got him and I told him, I said, “I answered your question just as truthful as I knew how.” I said, “For you to get up there and lambast me before my friends,” I said, “I think very little. I won't be back to see you anymore.” Next time I heard from that fellow, he had been promoted or called to the First Church in Nashville. Oh, the phraseology.

There were a lot of Germans left up there in Tientsin. They had the old German concession up there, and there were several Germans up there. These Germans, they would go around with sticks like that and walking canes, and they didn't fool with a Chinese at all. They'd take that stick like that and haul off and hit him, way out there in the country. I don't see why the Chinese didn't kill them, didn't gang up on them.

Robert W. Gowen:

Well, they beat the French, and they beat everybody else. I guess it was just in their blood to beat the Chinese, too, you know. That's the way they are.

[At the beginning of World War II, Mr. Doggett was contacted by the Federal government. They questioned him about his knowledge of the terrain of mainland China.]

Merlin R. Doggett:

They asked me a lot of questions. I was so busy and had so much on my mind, I didn't give it the thought that I should have. In other words, they gave me that section in there at Pengpu and up North across the River south, and they asked me what was wrong with the picture, and I said, “Most perfect picture I ever saw except I think there's some tunnels in this area.” I just wasn't thinking. The south of the river between Nanking and Shanghai, there were a few little tunnels in there. Then north of Tsinan-Fu, between Tsinan and Tientsin, there were some tunnels in there.

Robert W. Gowen:

Anwei is pretty flat, though, isn't it, the whole northern part of Anwei Province?

Merlin R. Doggett:

Well, yes, it's kind of flat, but it's hilly there around different places. I don't know Anwei very well except the railroad goes through it. Now, I have hunted pheasants down there around Mingkwang and Sanho. Mingkwang is flat; Sanho is hilly. And then up in the northern part and the western part of Anwei Province, it's hilly.

[End of Part 2]

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Mr. Merlin R. Doggett | |

| December 9, 1971 | |

| Interview #3 |

No transcript available. The audio recording of this interview can be accessed in the Special Collections reading room.

[End of Interview]