| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #196 | |

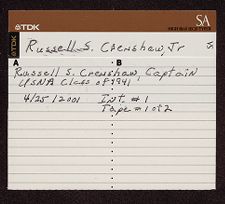

| Russell S. Crenshaw, Jr. | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 25, 2001 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Donald R. Lennon |

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Do you want to do this on a question and answer basis?

Donald R. Lennon:

I will be making notes as we go along. If something comes up that I'd like for you to expand on or elaborate on, then I'll ask you a question at the end or save it until you catch a breath and then ask you again. The least I say, the more depth we get out of it because it gives you more time for talking about your career.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, are you more interested in human-interest kinds of things, or are you more interested in historical things?

Donald R. Lennon:

A combination. I always encourage sea stories as part of it, but we also like to hear the variety of experiences you've had and everything that goes with that.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Alrighty. As you know, I wrote my memoirs for my Naval career and I've written a couple other books, which I'll mention later. But the reason I have this piece of paper is that I've been asked by certain organizations to give them biographical notes from which to write a resume and things like that. And so I prepared this for an old ship that I

was in, so I'm going to use it just because I had to go back, and I verified all the dates to make sure they're right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Always good.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

So where should I . . . ?

Donald R. Lennon:

Begin with your childhood, where you were born and reared.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, that's very simple. My father was a naval officer. He was born in Richmond, Virginia. My mother was born in Richmond, Virginia. I was born in Richmond, Virginia. Most of my brothers and sisters were born in Richmond, Virginia. But I never lived in Richmond. My father was a naval officer and generally speaking, as a boy, when he was on sea duty he was with the battle fleet based in Long Beach, California. He had various jobs, he was gunnery officer of the TENNESSEE, he was fleet gunnery officer and then he was on various staffs. When he was not at sea he would come back to Washington and he was aide to the CNO for awhile, back in the very early days. He spent World War I in the Navy Department as the director and organizer of the convoy system. And for that he was decorated by the U.S. Army and by the British government. He was made a Knight of the order of Bath, I think, except he couldn't accept the title. He has the decoration.

So we essentially cycled from Chevy Chase--where our home was on Northampton Street, Chevy Chase, D.C.--out to California for two years, three years, two years, three years. And that's what we did in most of my time, except for one particularly interesting time when dad was commanding officer of the Naval Mine Depot, YORKTOWN. During my years, from twelve to fifteen-- and this is the most magnificent place in the world--eighteen square miles of fenced in area with very few people and the

captain's quarters was a colonial mansion on a bluff overlooking the river. The other officers--of which, they were rather interesting-- Turner Joy was one of the junior officers and Felix Johnson, who was another one of the junior officers, both became famous admirals later. As far I was concerned, I was a twelve-year-old boy enjoying life. I loved the river. I was always trying to build boats, and built a couple. I sailed on the river and all summer I was either in my sailboat or out crabbing or fishing. In the fall we had excellent duck hunting out on the river, and so forth.

I went to school at Matthew Whaley High School in Williamsburg. They didn't have, at that time, a high school in Yorktown. So I went to Williamsburg and benefited from a circumstance that was interesting. While I started school in Long Beach, California--at the age of five, I guess it was--I went through the first grade or the second grade, or something like that. When I got back to Washington, they stuck me in--I ended up halfway through one of the years. So they stuck me in school in Chevy Chase, and apparently I wasn't doing too well because there was a conference between my mother and the teacher. They decided that I was bored, and that they would put me into summer school for a session and that would bring me even with the years, and they'd move me ahead. So they moved me up in the fourth grade. I got along fine, and everything went fine, and then when we moved down to Williamsburg, I was going into the eighth grade. But in those days, the schools in Virginia had cut from twelve years back to eleven, and so the eighth grade made me a sophomore in high school. And so I went ahead, and when I came up to senior year, when I'd gone into the eleventh grade, we moved to California, so I reported in as a senior in high school and the result was that I graduated a couple months after I was sixteen years old.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I was too young to get into the Naval Academy, so I did various things. Just to practice, I took the entrance exams to Cal Tech just to see what it was like, and I was accepted by Cal Tech. But the Naval Academy was very highly competitive, and we didn't have any political connections--Dad being in the Navy and so forth. So I had to win a presidential [appointment] to get into the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there ever any doubt that you would get into the Navy?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

The question never arose. There was never a single moment when my mother and father ever said, “Oh, you're going to be a Naval officer, aren't you?” or something like that. It never came up. However, I might mention right now why I'm named Rusty. I was named Rusty before I was born. I was the second son in this family, and my older brother--who should have been Russell Jr.--was born just after my two grandfathers had died. Grandfather Robbins was a colonel in the Confederate cavalry under Jeb Stuart, and he was a very famous Confederate cavalry officer. Then my grandfather on the other side had just died, so they named my older brother William Robbins Crenshaw, for the two family names. When I came along, my grandmother asked my mother, “Well, what are you going to name the baby if it's a boy?” And my mother said, “Oh, I don't know, I think we'll name it after Russell,” my father. My grandmother, who was a very famous writer--she supported her family after her husband was an invalid by writing--and she wrote bestsellers in the early 1900s. She was the secretary of the Virginia Historical Society, quite a well-known literary figure. Granny said, “Well Polly, I want you to know we're not going to have a Big Russell and a Little Russell in this family, so you're

going to have to figure out something else.” So they decided on Rusty. So I came along, and I was Rusty.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm sure that having a father who was off at sea for long periods of time and gone from home on tours to various places comes normal to a Navy family, but to an outsider it would sound like . . . .

Russell S. Crenshaw:

It never came up as a problem as a child, you know? You just take what you get. At first I had two mothers in a particular way. My Aunt Marion, who was fifteen years older than my mother, her husband died and she came to live with the family. So in our family, we had Aunt Marion and my mother--equal authority and either one could tell us what to do. Furthermore, in those days, there were no deployments. No overseas deployment. My father--they graduated him early, as a passed Midshipman, and he made the round-the-world cruise in the battleship VIRGINIA, the Teddy Roosevelt White Fleet around-the-world back in 1906, 1907, or 1907, 1908, I guess. At one time, on the shakedown--he was the executive officer of the AUGUSTA, and he put the new AUGUSTA into commission. They made a shakedown cruise to Australia and came back. Except for that they'd never be at sea more than . . . they had what they called battle practice. They'd go out for a week or two weeks, but we were never separated for long periods from the family. So the family went along just fine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you ever go out to sea with your father?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

No. I understand that Admiral Joe Taussig took young Joe out.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was another Navy junior in his class that went out.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I'm trying to think of who it would be. But you see, Admiral Joe Taussig was more than the Arleigh Burke of his time. The reason being that Admiral Joe took to the

shores over at Queenstown. He was the only naval hero we had in World War I, because you see, except for destroyers--the four-pipers--not much got in the war. Admiral Joe would have certainly been the commander-in-chief of the fleet and the CNO, except that he irritated young Franklin Roosevelt, who was an assistant secretary of the Navy. I think that the problem had to do with . . . you remember Josephus Daniels was the Secretary of the Navy, and he was a very stiff, difficult man. Admiral Joe was involved and he found that the treatment of prisoners at the naval prison of Portsmouth--I think it was, Portsmouth, New Hampshire--was improper and he spoke out about it. He said, “You have to straighten it out!” Well, this reflected badly on the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, who was Franklin Roosevelt, and Roosevelt never forgave him. So when Roosevelt became President, and Admiral Joe was coming up to be Commander of Battle Force and Commander-in-Chief of the fleet, he got moved aside and other people were put up in place. But Admiral Joe Taussig was quite a guy.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he could get away with things.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, Admiral Joe was also non-conformist, just like his son was. And I'm sure that he took young Joe out. Now I used to go out on Saturdays. You see, Saturday was not a working day, and if my dad had the duty . . . well, then later on he was captain of the ship, he was captain of the PENSACOLA later on. He would invite me, take me out to the ship. I could spend Saturday morning on the ship, and have lunch on board and come back in the afternoon. I loved that. Usually I'd go back on the fantail with the Filipino boys and fish for mackerel.

[Laughs.]

Well, that's what a boy was interested in! More than all that other stuff. I remember dad used to take me through the turrets and show me the stuff. And I'll never forget--he gave me a piece of smokeless powder. And oh boy, I said, “Well dad, is it dangerous?” And he said, “Well, watch out, it'll burn, but it won't explode or anything. It's like a piece of wood, but it burns very rapidly.” We never tried to do anything like that. But Roger Payne--the Paynes and Crenshaws were very good friends--Roger Payne got ahold of some from his dad and he tried to make a bomb one time, and luckily he wasn't successful in setting it off. They found him a couple of pounds of smokeless powder, but he couldn't make it burn. Anyway, that's the kind of thing that could happen. But it was no problem.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't mean to take you away from the presidential appointment.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Anyway, getting back to the presidential appointment . . . so I went back to prep school with Mr. Swavely. Eli Swavely was the greatest educator that I ever had anything to do with. Eli Swavely was a Pennsylvania Dutchman and a brilliant man. He had been successful, I think mostly at Lafayette College. And then he got interested in boys and training them for the academies, and he started Swavely Prep School at Manassas, Virginia. This was quite a fine school. It had nice dormitories, nice classrooms, and I remember a big football field. It even had a golf course. My older brother Bill went--he was the Class of '37--Bill went to Swavely for two years, because my brother Bill wasn't as lucky in school as I was. He didn't pass the exams the first year, and he just barely passed them the second. They had a terrible time getting Bill into the Naval Academy, but he got in.

The year after Bill was there came the Depression, and Swavely lost his school. He had to go bankrupt, and I had had a scholarship. I don't know, it was one of the Navy scholarships given by Mr. Swavely. I remember it was worth $700, which was big money. And of course, our family never had any money so it was a big amount of money. Mr. Swavely gave up the school but he decided to move to Washington and start teaching a prep class. He had a contract with the Woodward School in Washington, and it had classes down at the YMCA on G Street, down right next to the State War Navy Building, which is now called the Executive Office of the President. Swavely was down there starting it. In the meantime, he was teaching at Woodward School. When I first reported in, Swavely said he was going to honor the scholarship. So whatever arrangement was set with my parents, I don't know. But I took the train and went to Washington, and reported in at the YMCA. I lived in the YMCA in the fall of '36 through the spring of '37 prepping for the Naval Academy exams. When we first started we had three students. We eventually built up to a grand total of eight, and then a couple of day students.

My roommate was a nice guy by the name of Jim Leonard, who was from the hills of Pennsylvania and hard as nails. He was about nineteen years old. He didn't want to go to the Naval Academy or anywhere else, but his father was in politics and had gotten him an appointment. But Jim didn't understand it and wasn't interested in it, so Jim never did much. I was the only one who got into the Naval Academy that year. But we went ahead. Swavely, the first thing he did, he taught us to say, “I don't know.” That's the most important thing a man can learn, I don't know, and then listen to what the right answer is. The second thing was that every day, the first thing we did was to sit

down and write a five-hundred word theme. And for a sixteen-year-old kid that isn't easy. But we got to where I'd write a five-hundred word theme with no problem. [Swavely] was an excellent instructor in mathematics. Excellent English teacher. Excellent on physics and so forth. They put history back on the backburner and we just had an intensive course in history for about three weeks before the exam, so we could remember all the dates and so forth. We went in and I took the exam in Alexandria, at the courthouse in Alexandria, the first I ever recalled being in Alexandria. As time went on, I've lived in Alexandria very much since that time. I went to the courthouse and had no problems with the exam. It seemed to me they took three days.

I ended up . . . in those days the number I remember I'm not sure is true, but there were fifteen presidential appointments for sons of service officers. There were twenty-five Naval Reserve and twenty-five from the Fleet--I think that's right--of appointments. The only one I could qualify for was the straight presidential. My understanding is that something in the neighborhood of five thousand boys took those exams to compete, and I came in fifteenth. I got the fifteenth out of the fifteen. Now, they also had rules that if you got an appointment from somewhere else, you had to give up your presidential. So, by the time I got into the Naval Academy, I think I was about seventh on the list or something like that . . . But an interesting aspect to this was that I wasn't at all sure I was going to get a Presidential, so every time I had a chance in Washington, I'd go to Capitol Hill and walk up and down the corridors of Congress. I'd walk in, introduce myself to a guy and ask him if he had any appointments. And without an exception, I was always treated with great courtesy, and in many cases they would simply say, “Well look, I'm sorry, but you don't live in our state and I can't give you the appointment.” Or they'd

say, “Okay, we're always looking for good competition. We will let you compete for a second alternate, or something like this.” To make a long story short, nothing came of it, but it gave me a feeling about Congress and about the Capitol, and the way Washington works. It served me well.

Donald R. Lennon:

How about the Virginia Congressman, since you were living in Virginia?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

We had no viable connections with Virginia. You see, my father had never lived there. My mother's family . . . well, there were no Robbins living anymore in my mother's family. My grandfather Crenshaw had died, and so there were no connections. Senator or Representative Carter Glass was the one who appointed my brother Bill. But then again nobody was worried about me because I was still young and this was going to be my first crack, so they weren't worried about trying to take care of me, now if it had been two years later, a lot of people would have really tried but they didn't. So I got in, and it was the first year I could do it because you had to be seventeen on the first of April, and I wasn't seventeen until the fifth of April.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to ask you if you had turned seventeen by this time.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

No. So I was seventeen when I entered. I entered on the sixth of June, 1937. My brother Bill had graduated on something like the first of June. The whole family, except my father [was there] . . . now this was a time we were separated. My father was on a cruise somewhere. Oh, I know. They were having a battle problem out in the Pacific and he was chief of staff of the scouting force. But we were there, and my brother graduated, and then I went in, and between those two times I became a movie star. They were making a movie. I forget the name . . . Midshipman Jack, I think was the name of the movie, and they needed extras. You could make five bucks a day by being an extra. You

report in, and then they would send you to the tailor shop and they'd give you a Midshipman uniform, and then adjust the trousers and sleeves for you. And all you had to do was to go out when they told you walk around with pretty girls, back and forth, and you were background for all this drama going on in the foreground. So I made fifteen or twenty dollars doing this movie.

Donald R. Lennon:

In 1937 that's not bad.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh man, that was big money! A plebe only got four bucks a month, so that five dollars a day was big money. But we reported in, and I reported in along with forty-five, a total of forty-five candidates came in on the same day. They took us in, and they took us up to the sick bay for our physical exams. And this was fine. We all took all our clothes off and we'd run all around with a piece of paper and this and that. I remember they were testing my eyes to see where I could focus, and being a competitive guy I would say, “Yeah, I can see that,” and so forth. Then they dilated our eyes and it was the first time they had ever done this. They put solid cocaine--I think it was--in our eyes. I say that, it might have been . . . the word “aderbern” (?) comes up, I'm not sure what aderbern (?) is. But I think it was actually granular cocaine they put in to paralyze the muscles of your eyes. Then they refracted this. Then we went to see the examining doctor and he said, “Well sorry young man, better pack your gear and go back home.” I said, “What?” He said, “You've got myopia.” I said, “I can see fine.” And he said, “Sorry, we can't accept you.” End of the world. They gave me some black glasses.

At that time, mother had rented a house on Maryland Avenue, about four blocks out. You know, right across, the beginning of the first commercial block. Big old house. It was painted yellow then. And I had to go there and tell mother that I had failed. It was

just unbelievable. So I started to go out, and some other guys were going in, and I moped around. We started out, and down at the bottom of the apartment house just outside of the gate, I guess it's gate two now, but the main gate--on Maryland Avenue--there was a place where you could get Coca-Cola and sandwiches. I went down in there and there was Joe Taussig, Telly Sheldon, Doug Hine, and I forget who else, all with black glasses like that, all . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you know them at that time?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

What?

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you know . . .?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I knew a couple of them, and somehow or another I was sitting with friends that day. We never knew each other well as boys, but this day I knew them. We sat down and said, “Oh my God, what are we going to do now, we've got to tell our folks that we failed,” and so forth. So I went home, and I told my mother. I said, “Mother, they kicked me out of the Naval Academy because I've got myopia.” And she said, “What do you mean?! Who says you've got myopia?” I said, “Well, the doctor at sick bay.” “I'll see about this!” And so she got on the phone and she called Oscar Smith, who was Head of Ordnance Gunnery, and said, “Oscar? Some damn young doctor over at the Naval Academy said there's something wrong with my boy Rusty! There's nothing wrong with my boy Rusty! I want you to get this thing straightened out, Oscar.” So I'm going, “Mother, mother, mother!” And she said, “There's nothing wrong with you! I know there's nothing wrong with you. I had you examined before, there's nothing wrong with you.”

So Oscar called up Dougie Woods--Captain Douglas Woods was the commanding officer of the hospital. He called up Dr. Woods and said, “What can we do about this?” And he said, “Well, I don't know, there must be something wrong. Send him over tomorrow and I'll examine him.” So I reported over to the hospital at eight o'clock the next morning. Dr. Woods examined me and said, “There's nothing wrong with your eyes. You're fine. You've got a little bit of myopia, but it's nothing. We won't worry about that.” So he signed me 'accepted.' And you see, he was Captain and the Lieutenant Commander turned me down.

So I went back to the Naval Academy that day, and they gave me the haircut and so forth. Larry Geis was the guy out of thirty-nine that took me through to fill my bags and all that, to go through Midshipmen store and take some of this. You get your shoes measured and all that. Larry was an upperclassman, and my bag's getting heavier and heavier. I've got two of these laundry bags like this, and old Larry up there, saying “Yeah, come on, let's get moving,” and so forth. As soon as we got around the corner when nobody else could see him, Larry said, “Give me one of those bags.” Larry put it over his shoulder and he and I went up. The upperclassman helped me even getting in that bag. And I ended up there.

That day that I went in they rejected forty-three out of forty-five applicants. All forty-three of them got back in, but a lot of them went all the way home back to Montana or Arkansas or you name it, and then they had to come back.

Donald R. Lennon:

I never could understand why they wanted to do what they did in dilating your eyes.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

The world is very interesting, but the Navy had these requirements that they wanted perfect specimens, and we were as perfect as you could get. There's a tragedy involved with this. Erling Hustvedt. Erling just died about two or three weeks ago. Erling was a fine, fine Naval officer. Erling and I were going to room together, but I didn't know about it. His father and my father were good friends in the Fleet and they were chatting and decided, “Wouldn't it be great if those two boys roomed together?” So Erling was told about it, but I never even heard about it. Erling went to have an exam and he had the same kind of problem I had, except that in the aftermath, he didn't have Captain Woods to look out for him, and Captain Hustvedt somehow crossed swords with the Chief of Medicine and Surgery, who was a rear admiral. The result was that although Erling had been re-examined many times--they said his eyes were perfectly okay--they never could get the Chief of Medicine and Surgery to back off, and Erling didn't get in. So Erling went to MIT and he graduated, and he ended up being commissioned, I think, senior to us. Erling got into the Navy before we did. Eventually he had a good naval career. But there was an example. And of course now I don't know what they accept, but even when I was still on active duty they used to have a lot of officers who had to wear glasses, and it didn't interfere . . . you didn't let them be officer of the deck if they couldn't see well. And I can tell you this, I don't wear glasses today. With any of the ships I ever commanded, I was always the person who saw everything first, I could see further than they could see. I'm sure it's because I was interested. That's the main thing, that I was interested. And they weren't as interested as I was. The Navy's physical exams were just extreme and it wasn't constructive.

Donald R. Lennon:

It probably cost the Navy some good officers.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh my God, I'm sure it did. It resulted in a big distortion of the naval officer pool. Anyhow, I got in and after I got in, everything went fine. I enjoyed it thoroughly from the day I got there to the day I left. I loved it. I was running and jumping and so forth, and of course about two weeks later I sprained my ankle and ended up in the hospital. But I got over that pretty fast, and then I went out for football and fancied myself as a very skillful tailback. I was gonna be a great runner and passer and all that. I got out there. The Naval Academy had hired or brought in selected athletes for the first time. We went out there to go out for football, and there were 165 plebes going out for football out of a class of, at that time, 600. So one quarter, one out of four Midshipmen, were out there and we got all these old uniforms, shoulder pads, shoes and helmets. We were running around there. Then they said, “Okay, all you guys come in here.” So they called out eleven names. And eleven plebes jumped up in brand new uniforms, right out of the bandbox, and they tossed them a ball and said, “Okay, so these guys start calling signals and right off.” They called out eleven more names. Eleven more guys jumped out there, and they ran them out. They called out eleven more names, and all of them in brand new shoes, brand new everything, and off they went. And then the coach, who was named Hank Hardwick--I didn't like him very much--said, “Okay, all the rest of you guys . . . you see those signs? Stand in line there at the sign.” They had a sign for tailbacks, for quarterbacks, for halfbacks, and so forth. There were thirty or forty guys behind 'tailback' and fifteen behind the other ones and so forth, and I said, “Wait a minute.” I said, “This doesn't look . . .” So I looked around and over here there's 'running guard.' And there's only two guys. So I go over and stand in line for 'running guard.' And so I said, “Okay, you're going to be a running guard.” I started competing,

and I made the team. I made the squad, and eventually worked my way up, so much so that I made my NA, which is next to making a letter, in football.

Donald R. Lennon:

These guys that came in in new uniforms, knowing all the plays in advance . . . had they gone through the same procedures that the rest of you had to get into the Academy?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Not exactly.

Donald R. Lennon:

Or were they mainstreamed in just to play football?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Yes. The answer is that they came in later. It was much, much tougher than it is for an athlete today, where they hire them and bring them in. I'll tell you a couple of interesting stories. They had to pass the entrance exam, but they didn't have to pass the full exam if they had had one year of college. So all these people had had one year of college. This is where they demonstrated their ability. They were also all a lot older. I mean, all these were right up, eighteen, nineteen, or twenty. Right up to the limit, but they only had to pass a substantiating exam. I forget what they were, but I think they had to take a substantiating exam in math, physics, and English, I'd guess. But I don't know. It was three subjects, and they had to pass that. Anyway, they made it easy for them. However, the most interesting thing is that once we were in the Navy, they didn't make any allowance for them. They had to compete. And to make a long story short, they brought, I think, thirty-five in, or certainly thirty-three. At the end of plebe year, I think, only about ten of them were still there. The rest of them had been bilged out. And one of the most interesting ones was there was a big guy, and he was a standing guard from Georgia Tech. I remember he was a big guy. He weighed about 210 lbs, which was big in those days, and he was old and he was a tough country boy. I remember trying to

block him one time, and I went boom-boom! It was like running into a tree! But he didn't like being in the Navy. We were inspected for every formation, and we all had to wear high block shoes, but his toes hurt him. So he slit his shoe with a razor, so his toe could ease out. The officer inspector said, “What's wrong with your shoe?” And he said, “Well, sir, I had to cut that open. My little toe hurts, you know? And I can't have that.” “You're on the report for improper dress. Don't you do that again.” Three days later, he was on report again. Officer put him on report. And he says, “Hey, listen! That's a bunch of crap! I came here to play football.” He said, “I'm not going to put up with this foolishness! Back down at Georgia Tech they gave me a house, I got a car, they gave me allowance, and my gal can live with me. All this foolishness here, I'm not going to stick around!” Hal says, “Well, up and resign.” And he did. So all these other people who managed to stay in did just as well as anybody else.

Anyway, at the Naval Academy I didn't have any trouble plebe year with hazing and so forth, because I considered it mostly a joke, and the upperclassmen considered it as a joke. It was a game of wits with them. You'd play the game, and they would play the game. I really only got my tail beat once or twice, and I'd ask for it, so I didn't complain. Another thing . . . I was on the training table. I was first on the football training table, then the wrestling training table, and then the lacrosse training table. So I really didn't spend as much time on the tables. And that's where every day the old grind, where you get to dislike people. I never disliked anybody. They all got along fine.

Donald R. Lennon:

A few times underneath the table, I reckon.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Yeah, they put you under the table, so what do you do? You get some matches. Stick them in the edge, then go down to the other end, stick them in the edge, and light

the match. Then get them on the other end and all of a sudden, 'waaa!' Did you ever have that happen?

Donald R. Lennon:

No.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh man, it hurts. It's like it hits you with a hammer. Anyway, we did things like that. And then when they beat you with a bread pan after that you were laughing because-

Donald R. Lennon:

You got yours first.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I got mine first! [Laughs.] But the Naval Academy was a lot of fun. I never had any trouble with academics. My worst marks were in Spanish. And then I didn't do too well in English, until first class year. They had a course in poetry, and I liked that. And I did very well. Then another thing happened, which was very interesting. This happened first class year. Going into first class year the Trident Society, which was the literary society of the Naval Academy, had some people that had been working on the magazine. This particular fellow that was going to be the president of the Trident Society was a fellow that irritated a lot of people, so the upperclassmen came to me. I was the art editor. I used to draw pictures for the art, the Trident, for the Log, and so forth. So they asked me if I would be president. I said, “Gee, you know, I've never written anything. I don't think it's right for me to be president.” And they said, “Look, please Rusty. Be the president. Because if you don't, they we've gotta have this guy, and we don't want him.” So I said okay. So I became president of the Trident Society. Next time March came out, English, I had been standing--by this time we had about five-hundred in the class--I had been standing one-hundred and fifty, one-hundred and eighty, two-hundred, something like that. I stood eight.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

So I learned about politics.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Anyway, so then we came along and athletics were a big deal. I did well in lacrosse. Oh, I didn't play football because I got hit in the head. I tackled a guy without being careful enough and knocked myself out, and then I did it again about six months later. I had two concussions where I lost my memory. It was very interesting. My memory came back backwards. In other words, I couldn't remember anything for six to eight months before I'd been hit. Then little by little I could remember seven months, then four months, and three months, and then one week. And finally, about a year later, I could remember right up until the accident. That happened to me twice. So they said uh-uh, no more football for you. But lacrosse was okay. Of course, I wasn't a very good football player, but I was about as good a lacrosse player as they had. And the reason I was a good lacrosse player is not because I...you see, people like Telley Shelly could handle a lacrosse stick like it was magic, and I never was very good at that. But I just had the aggressive spirit to go in and make the goal, and I weighed about 175, 180. I was big enough and strong enough so that the defensemen couldn't stop me. I could throw a shoulder into a defenseman and knock him on his can and go on in and shoot. So that's what I did.

So then I graduated . . . oh, let me tell you a couple other things, because they had something to do with where I was going. First, I loved the battleship crew, just to be at sea, be part of it. But I didn't want to be in such a big organization, because I watched the junior officers doing nothing, just standing around. You had to be a lieutenant or

lieutenant commander to get to do anything on a battleship. Then we went on a second-class cruise with the 'four-pipers,' four-pipe destroyers. I started off in the engineers . . . we had twenty-four Midshipmen, so eight of us were in engineering, eight of us on deck, and eight of us in navigation, or something like that. I reported down to the engine room of that four-piper. It was the USS ROPER 147. And I reported down there, and there was a third-class machinist's mate standing the engineering officer of the watch. We came aboard with twenty-four Midshipmen and the ship had fifty-four people, officers and men. The ship had three officers, and I think we brought one Naval Academy officer with us. That made four officers and seventy-five people, I guess. That was what the crew was. So we went down there and this third class was saying, “Well now, this here is the turbine. These are the turbines and that's the reduction gear and . . . excuse me.” He grabbed a wrench, went over there, and there was this vertical reciprocating pump, and he hit it with the wrench. It went crunch-crunch and he came on back and continued with explaining what the pumps were. All of a sudden he grabbed the wrench again and hit this thing again. And that was the way it was. That was a main feed pump, and it would jam, and that was perfectly typical of these linear reciprocating pumps. But his ears were just tuned to it. Whenever that pump stopped, he knew it without anybody saying anything, and he knew that he was going to hit it and it would start again.

Donald R. Lennon:

[Laughs.]

Russell S. Crenshaw:

So then he said, “Okay, now you guys gotta stand and watch.” He said, “You two go on up to the steaming fireroom, the number one fireroom.” The next guy to me was Willie Demater (?). Willie Demater (?) was a particularly interesting classmate who died last year. And Willie and I were thrown together all through our careers, because 'Cr'

and 'De', everything is alphabetical. So 'Cr' and 'De' came together. So Willie and I go up and we go over to the welder-gear and we climb down the hot air hole into the number one fireroom. And in the dim light of the fireroom there's one emaciated fireman down there jerking the burners, and so forth. And he says, “Oh, good to see you guys! You ever jerk burners before?” We said, “Yeah, we used to jerk burners on the battleship.” “Okay, well, here they are. This is how it works.” “Yeah, you take the burners.” “How about the checks?” “What are they?” “Oh, well, you know, you gotta see where the water is in the boiler.” “Okay, well, here's the valve and there's the glass.” “Yeah, I've done that before.” “Boy, how about the blowers?” “Oh, I don't know anything about that, but there's the valve.” “And see that periscope? You better watch out. The skipper gets mad as hell if you get any smoke. So you keep your eye on the periscope. If you see any smoke, then you jiggle the valve. Sometimes up, sometimes down, but you do it until you don't get any smoke.”

So Willie gets on the checks and the blower, and I'm on the burners. And we're going fine, and the guy says, “Hey, that's fine! I'm going to go to the main engine room and I'll see you later.” He disappeared, and we never saw him again. Jerking burners-- running the fireroom. Of course, these are 150 pound appliances, so this wasn't a big deal. But there we go, and after three hours . . . and they had an open galley. Any time you wanted something to eat . . . Midshipmen are always hungry. That's the main thing, is to get enough to eat. And with an open galley, you go to the galley night or day and get a jelly sandwich, for example. Or if they had anything left over from lunch, it would be there in a pan, and you could have a little bit of it.

I just fell in love with destroyers. I just thought it was great. They let you do anything. You could stand officer of the deck watch and actually steer the ship, keep station. So I decided a destroyer was where I wanted to go, and then I got a ride in one of the brand new destroyers. It actually was Admiral Carney's destroyer; he was lieutenant commander then. I knew him because he lived at the . . . When we were kids on Northampton Street, we lived there. We had, on Northampton Street, at the foot of the street was . . . .

. . . This was on Chevy Chase Parkway, was C.A. Cooke (?), who was the four star admiral Commander of the Asiatic Fleet at the end of World War II. And we had Ted Sherman, who was one of the famous carrier admirals in World War II. He was right over here. That whole area there, we must have had half a dozen or more Navy families, all of whom were important players in World War II.

But anyhow, I knew Mick since Betty and Gay and I all played, and lieutenant commander Carney used to come up and play with us. We'd play after dinner time. And so he was coming . . . they'd bring in the football team. This was, must've been youngster cruise. This was before I got hit in the head. He was commanding officer of the DRAYTON. And we went roaring up from Norfolk up to Annapolis at 27 knots. Boy, I tell you, I looked at that and said, “Boy!” They were like beautiful yachts. And I said, “I'll do anything to go to sea in this _? .”

So then, as we got towards graduation, we went . . . the way you decided where you were going to go is you do precedence numbers. The night they were drawing precedence numbers down in Mem Hall, my roommate had the duty, so he asked me to draw for him. I went down and I told them . . . it became my turn and I said, “Well, now

I'm going to draw for Joe Reedy.” And they said, “Fine.” So I reach in and stir around, pull out--and I guess there were 450 numbers in there--and I pull out number five. “Oh my God!” Joe, you know, this Joe is an awful nice guy, but this is my career! So I said, “Okay, okay. Now I'm going to draw for myself.” And I reach down and pull out number one.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I got number one! So I signed up for the newest destroyer in the Pacific fleet, and Joe signed up for the newest destroyer in the Atlantic fleet. I got the USS MAURY, the 401, and he got the USS MAYRANT, the 402. That was just wonderful. So then we graduated, and I did respectably, but not spectacularly. But I enjoyed it, and I never worked very hard in the Naval Academy. So I went to sea and reported to MAURY in division eleven, squadron six. And Admiral Conolly, er, Commodore Conolly was our squadron commander at the time, and Ed Snare was my skipper. And we had a division commander. E.P. Sauer was the division commander. I never really knew him very well. And we were operating with a battle force. We were Destroyer Battle Force, and we'd go out with the battleships and we'd practice the squadron maneuvers and the division maneuvers. Mostly we were mainly torpedo boats. These ships carried sixteen torpedoes. We would go and make these squadron and division attacks at echelon and so forth.

One time in the fall of 1941, we went out and if I recall correctly, the second flotilla . . . we had 126 torpedoes in the water at one time. And that was the way it was. You know, battle fleets, the battle line, and the cruisers and echelon and then the flotillas and the destroyers. And then you'd attack the enemy, and the idea was to bring all the

firepower to head. You'd put the enemy battle line into a crisscross of all these torpedoes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, were these live torpedoes?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

They were the regular torpedoes that we would use in the war, but they had an exercise head on them. This was a warhead of the same weight as a regular warhead, but filled with water, and had some compressed air added. What would happen is, you'd fire this and you would set it to pass twenty feet or so under the keel of the ship you were shooting at. And then at the end of the run, the compressed air would blow the water out, and the warhead then would become buoyant and bring the whole torpedo up after it had run out of gas. Then you'd go out and recover it, then go overhaul the torpedo, and get ready to go again.

Donald R. Lennon:

During those maneuvers like that, there was no way of telling whether the torpedo was defective or not.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Uh, well, no. That of course, is the key point of my whole career. Or should we say, certainly the key point of my writing since I retired. There was beginning to be some suspicions, but not by people of my intelligence, or my experience. We had a rule of how fast the bubbles from a torpedo would rise. And they said that they would rise at three feet a second, or something like that. While I was out there, between . . . I reported in March of 1941, and then, of course, Pearl Harbor was in December of 1941. But sometime, say about May or June of 1941, they came out with some instructions saying, “Well, there's obviously some problems here. We've got the wrong number, so we better set the numbers at . . . the rate of rise is less than what we thought it was.” I think it went something like from three feet per second to two feet per second.

Now there was a hint that the torpedoes were running deeper than they figured, because if you stop and think about it, it's nonsense that they can't measure and calibrate the rate of rise of bubbles through salt water. And therefore, if they're getting a different rate of rise, it must be that the depth is different from what they think it is. But that was beyond my competence to worry about. It never occurred to me at that time that there was anything wrong. Everything else was fine, and we fired . . . the new thing in the fleet was automatic control on the guns. In our case, we had hydraulics but some ships had all electrics. They had vacuum tubes, and the vacuum tubes would go bad, and some other things would happen--night battle practice and things like that were quite exciting. But they were working hard on adding air gunnery, all of which would have been moderately effective against horizontal bombers, but there was no provision for dive bombers.

I was assistant gunnery officer on the ship, and Ed Miller, who later became an admiral, was my boss. I was studying how the computer worked. They actually called it a range-keeper in those days, the Mark X. [I] discovered that it only computed for horizontal motion and very limited vertical motion. And when you threw it to dive bombing--it had a knob on it that said 'dive'--all that did was put it on automatic range rate correction, but didn't do anything about elevation and/or deflection. So I decided, “Well, what do we do about it?” And I said, “Well, here's what we can do. The plane will be coming in right at us, so we're not much worried about deflection. We can take care of the elevation by just setting a little bit of superelevation to take care of the drop. And then, set up a barrage fire to have the burst occur at three thousand yards in, two thousand yards in, one thousand yards in, that kind of thing.” I went to Lieutenant Miller with this, and I said, “Mr. Miller, I have been studying the range-keeper and it won't

solve the problem, and here is a proposal on how to do it.” He got really upset, and got mad at me and said that I shouldn't do that, that that was not a proper thing for an officer to do, to get into details like that. That was for enlisted men, and I shouldn't question what the Bureau of Ordnance had put out, because obviously they were the brilliant people who know these things. He said, “Well, we're not going to pay any attention to this.” Well, now this was dangerous. Incidentally, I'd gotten interested in anti-air gunnery much earlier, because even as a Midshipman, I had calculated the problem of lead angle, from duck hunting and so forth, and so I invented a way of computing the lead angle from the rate of motion of the gun, to make a lead computing sight. I proposed this when I was a second classman, and sent it to my ordnance professor. He was a fellow named Freddy Wolsiefer (?). Freddy was an old China hand, and he wore half-Wellington boots and had embroidered things inside his uniforms and all that. “Well,” Freddie said, “I'll send it to the Bureau of Ordnance.” Well, what happened is that it goes on up a bunch of people that have no imagination and no intellectual curiosity, and they don't have any expertise, either. So it goes up, and they write a letter saying, “It's nice for that young Midshipman to be interested in these things,” and that's all that happened.

In the meantime, Stark Draper, a professor at MIT who I later studied under at postgraduate school, invented the Mark 14 sight, which is exactly the same system, but he had a much better system than I had. I did it by electrical generation, basically fixed, but he used gyros, which measured the motion in inertial space. His was more correct; mine really wasn't a perfect solution. But I was on to the right way, and had I been put in contact with people like Draper. Draper said, “Wow! This is just what we want to do

now. We'll base this on a gyroscope and we'll do it.” But there's no system in the Navy to take care of this, and I ran into it frequently during the war. When you come up with a proposal, with an improvement, the system doesn't have a way, and you get back to what happened on torpedoes. You have one commander sitting in Washington on what they call the torpedo desk. Then you've got a group of people up in Newport, at this time, who know all the secrets. No one else is allowed in the fraternity, and these people can make stupid errors, as they did, on the Mark VI Explorer, stupid errors, as they did, on the depth mechanism in the Mark XIII, XIV, and XV fish. And nobody knows about it. I can assure you that the same thing goes on in the nuclear program.

Donald R. Lennon:

Mmm-hmm.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

When I was in the Bureau of Ordnance much later, in charge of Taylor's (?) Program, they finally broke down the doors and got in behind things a little bit at Los Alamos. These people were using obsolete technology. They had their minds closed. They didn't let anybody in. There was no criticism. There was no competition. And that's what leads to these horrible things.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you had been an admiral instead of a lieutenant, they would have probably paid some attention to you, wouldn't they?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

You'd had to have really rattled the cage.

Donald R. Lennon:

Admiral Jules James is a vice admiral, and he was always, in his papers, there were all kinds of drawings and everything for inventions to improve ordnance and improve various things he was working with.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Yeah.

Donald R. Lennon:

He was doing the same type of thing you were doing.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

That's right. Look, if I'd been an admiral or captain in the Bureau of Ordnance, fine. But just like what happened to me, in a way . . . I did this all my life, you see. The truth of the matter is real simple. When you get up to the top, and you have somebody rattling the cage, trying to change the Navy, or to change things, the old hands, the people in charge, say, “Look, we don't want to have a change. We like it the way it is, and we don't want people making waves and 'upsetting the apple cart.' Our problem is getting along with Congress. Let's get along with Congress! Let's not rattle the boat.” And as soon as a Naval Officer starts designing something, all of the sudden he's got the scientific community, the huge academic machine that's out there, all the laboratories. “Who the hell is he to be doing this? That's our job! We're the brains, let us do the thing!”

I always said, “Give the Russians all of our plans. Everything. The most complicated stuff we've got. Give it to them! They're all engineers, they're all scientists. They'll never listen to anybody else!” I mean, they live in a world where they're trying to outdo the other guy, and the only thing that counts is what their papers say, and what their academic reputation is--where they stand in the engineering hierarchy. It's a very complicated, difficult problem to cause people to open their minds; to have people learn that there is value out there. Listen to those people, they might know things you don't know!

Donald R. Lennon:

It hasn't changed any.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Hasn't changed at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Or the Osprey scandal wouldn't be what it is.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

You're right, and so many things like that just go on and on. Anyway, we still haven't gotten to the war yet. But that's all right.

I had a wonderful time when I reported out to the Fleet. The MAURY was great. I was the eighth officer in the ship. She was an absolutely magnificent yacht. You didn't put your feet on the deck--you had raised walkways. You had stainless steel wire all around. You had paneling; the inside was beautiful. I was the eighth officer, and I had to double up. That was the first case where two ensigns had to room in the same room. You had a crew of 156, and in your mess compartments you could have the whole group sitting down for a meal that was served by mess cooks, bringing the food out from the galley. Great. We had four boats. We had two whale boats, captain's gig and a thirty-foot motor launch. We had sixteen torpedoes. We had the newest thing in fire--the five-inch gun. We had a wonderful new Mark XXXIII director, and that's what I got so interested in, in fire control. They were magnificent ships.

The first time I went on the bridge to take the con of that ship, I walked up on the bridge a junior officer. The captain sitting there, the head snare, he was a very interesting guy. He said, “Mr. Crenshaw, you know anything about ships?” I said, “I studied them, sir.” He said, “You ever handled a destroyer?” I said, “Yes sir, I handled a four-piper when I was on a second-class cruise.” He said, “Okay. Take the con. Formation speed is thirty-six knots. We're number four column, standard distance is 300 yards. I don't want you further out than 325, and not closer than 250. And don't use more than 39 knots to keep station.” “Aye-aye, sir.” So I relieved the officer of the deck, took over, and I watched the statimeter and so forth. And of course, everybody was watching. They knew exactly. You see, I was riding right on the crest of the stern wave of the CRAVEN,

the ship ahead. And no matter what you did, it's like trying to balance on top of a basketball. Then if you go just a little long you go scooting down. So I started to scoot down, and boy, the distances went 290, 280. I cranked off three turns, which is nothing. Cranked off five turns. Took off ten turns. Then when she hit 250 I took off thirty turns, which is three knots. She went into about 230 yards, and then she started going back. And I started cranking more. By this time, you see, I'm on the back side of this wave. I got up to my thirty-nine knots and she was just barely creeping back up. She opened out to almost 500 yards.

The captain shook his head. “That wasn't so good.” “No sir. I'm sorry captain.” And the whole bridge dissolved laughing. They knew it, and they went ahead. And because they wanted me to stand watch and floor, particularly in port, they qualified me in two weeks. And so I was a qualified officer of the deck in a fleet destroyer in Pearl Harbor and had my twenty-first birthday party in the wardroom of the USS MAURY.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

I really had an awful lot of luck. Then we spent three months in overhaul in Pearl. We had a very nice summer in Honolulu. All the j.o.'s got together and we rented a little house in Waikiki and had a grand time. It was just wonderful. Then the war clouds started coming in.

As we went out, about the 25th of November, 1941, we were going out for routine operations training. As we stood out at Pearl Harbor, they sent out signals from the ENTERPRISE for Cruiser Division Five and Desron Six to join Admiral Halsey and form Task Force Eight. We steamed south until we were out of sight of land, and then we turned west. We formed up into a circular formation with a squadron of nine destroyers

around the three cruisers, with the ENTERPRISE in the middle. Then Admiral Halsey put us on war basis, and we brought up ready service ammunition. We started standing condition watches, and we steamed west and then, about a day later, they told us that we were taking a squadron of Marine fighters out to Wake Island to beef up the defenses because they were afraid that the Japanese might attack.

So we went on out. It must have been about the first or second of December. We crossed the international dateline, and we crossed it twice back and forth so I didn't know which day it was. And we went in close enough and we flew off the fighters. If I remember, I don't know if they were Brewster Buffaloes or what. I think they were Brewster Buffaloes, not FOFs. Anyway, then we turned around and came on back. Every day, we'd have a dawn general quarters, we'd fly out the morning search, and we'd fly out an afternoon search. So we were flying out an eighteen plane search twice a day.

We were steaming back to Pearl, and we were going to get there on Saturday morning, the sixth of December. Then the tradewinds picked up. It got rough, until it got really hard. We'd been running at twenty-two or twenty-three knots, something like that, so we slowed down to fifteen, and they were still too rough. The destroyers were taking a beating. So they slowed down to maybe ten or twelve knots, because of the wind. And so our arrival time moved from the morning of the sixth to the evening of the sixth, and then to the morning of the seventh, and then it was finally going to be sometime later in the day of the seventh.

Donald R. Lennon:

Weren't you lucky?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

We didn't know it, of course.

Donald R. Lennon:

One question. You didn't meet or get to know, or remember a Marine officer in that air wing by the name of Paul Putnam, did you? He was a major.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

No. No, I didn't. The only Marine that I ever knew much was Archie Vandegrift. Archie Vandegrift was a friend of my dad's, and a classmate. We used to see the Vandegrifts frequently, but not during the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

Putnam was in that group that was forced to surrender at Wake Island.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh really?

Donald R. Lennon:

The movie Wake Island was-

Russell S. Crenshaw:

We never met any of the fliers, you see. Unless you met them ashore. You never had any exchange like that. Anyway, on the night of the sixth of December, I had the Mid-watch. And I also recall that I stood the Mid-watch in white service. You know the high collar?

Donald R. Lennon:

Mmm-hmm.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Up in the director. White cap. The squadron commander had permitted us to shift to a new uniform, which was blue trousers and a white tunic, because you just get the trousers wet. In condition watches and so forth you get your trousers all mixed up. So I had stood Mid-watch, and I turned in to get sleep. It was going to be Sunday morning, and we weren't going to get in until after lunch or so. So I expected to sleep in. All of a sudden, my roommate, Harry Hughson, came charging in and said, “Hey Rusty, get up! The Japs have bombed Pearl Harbor!” I jumped out of my lower bunk and I stood up and I said, “Oh my God. That Harry, trying to pull a practical joke like that and get me out of my bunk on Sunday morning!” So, in my pajamas, I walked on into the wardroom, which was just around the corner. And there, in front of the radio, was Ed

Miller, Harry Hughson, and somebody else. Three officers. They were just listening, and a voice was coming in from Radio Honolulu saying that bombs were landing in Aiea Heights, one of them up near the Pali. Parachutes were coming in and so forth. It was something. Then I said, “Well, if you're gonna go to war, they say you better make sure you're clean because you could get an infection in your war wounds.” So I went and took a shower, and got all dressed up in a clean uniform. Then I went into the wardroom and Wyatt, the big mess attendant, was there and said, “Mr. Crenshaw, what can I get you this morning? It looks like we're going to have a busy day!” I said, “Wyatt, give me my regular.” So he gave me a great big stack of hotcakes with two fried eggs on top, and that was my standard super breakfast. I ate my super breakfast and had my fruit juice.

I was just finishing my coffee when telecorders (?) went--it must have been about 8:45--a message came in saying Pearl Harbor had been attacked. We went to general quarters. We were up there--a beautiful day. We were charging around, airplanes were flying. All the airplanes . . . from the time we left the airplanes had been carrying bombs, and they had been testing their machine guns and things like that, but the bombs were still painted yellow, and the torpedoes were still painted yellow. You could see them, a bright yellow. We attacked a couple of destroyers. We had sonar contacts--we called them “sound contacts.” Sonar wasn't invented--the word wasn't invented until somewhat later. But I think they were mostly whales--nothing happened.

It was either morning or afternoon--I suppose it was the morning--but we didn't really find out about it until later. One of the planes didn't come back, but everything else happened normally. And then about sunset, some ships came out from Pearl--it seems to me it was a light cruiser, the RICHMOND, maybe--one of the light cruisers

came out, and a couple of destroyers. They joined up, and then they deployed us for a night search and attack. You put the destroyers in sections--two destroyers--and we were on five-mile centers. We spread across about twenty-five, thirty miles of sea. We went screaming down at high speed, twenty-seven knots or something like that, and the cruisers would be one cruiser behind each division of destroyers. So we had the three cruisers like that, and I guess there were two destroyers that came out from Pearl that had been told to look out for the ENTERPRISE. We went down, and we were running out of gas. We didn't have much fuel left. We didn't find anything. We were going to the south, and the Japs were up north. So then we turned around and went on back and reformed, and then we went in and went through a very complicated approach procedure. We got up to the entrance of Pearl and they said, “We're not ready for you.” So we had to turn around and go back, and then we came back and did the exact same thing again. We arrived just about noon.

We were one of the last ships to go in. I say that, but I'm not sure. There were ships ahead of us. As we went through the gate at Pearl, on the Pearl Harbor channel, we could see smoke up ahead, but we didn't know what it was. They opened the gate, and they had a barge--an admiral's barge--that was coming around. It was all messed up with fuel oil, and it had a Marine in his dress jacket all open, and a couple of sailors there, all messy. They had a Lewis gun up on top and they had submachine guns and rifles. Ed Miller must have had the deck. So I was taking care of the fantail. As the barge passed close astern, and I yelled over and said, “Hey! What happened? We heard on the radio that the Japs sank three battleships! That isn't true, is it?” And the coxswain said, “Nah, that isn't true! They sank five.”

Then we went on up, and we shot up the channel, and as we looked over there at Hickam Field all of the quarters and all of the lawns had been dug out, and they had machine gun nests there, machine guns pointing all over. And you looked over at Hickam Field and things are still burning and smoking, and you'd see the wrecks of the hangars and the wrecks of a few B-17s that were burned out. There was nothing flying around. Then we went up, and the first thing we did was to make a turn at Hospital Point, and here was the NEVADA. She was up on the beach and still smoking, and I looked at her and said, “Oh my God.” Joe Taussig was one of the anti-aircraft officers, and the aftermast was all burned out. I said, “Gee, I don't know what happened to Joe.” And then everyone said, “Oh, my God!” We looked up there, and there was battleship row. And at the end, this big fire was still going, just enormous amounts of black smoke. The OKLAHOMA was upside-down, and her hull was up out of the water like that. It looked unreal. The ARIZONA was at the end and still burning, but her masts were up. All the rest of them, the WEST VIRGINIA, the TENNESSEE, and so forth, they were heeled over, they were down low in the water, and it was a mess.

About that time we got next to the floating dry dock, and there was the SHAW sitting there. Unbelievable! The floating dry dock was down at one end, and it looked like someone had taken a little ship model and just smashed it. It was just terrible. And over at the head of 10-10 dock were the big dry docks, and the PENNSYLVANIA was in there, and the CASSIN and DOWNES were in there, and still smoke coming out. We went in, and there was the OGLALA and she's over on her side. I guess it was hell on the inside, but there was a cruiser--I think it was a cruiser--inside. I don't know what

happened to our cruisers or the ENTERPRISE. Maybe we went in first, because I don't remember seeing them at all.

We went over to the sub base, and we tied up to the pier. I guess we were all alongside, one place or another, or we might have been two in nests. They brought a train alongside, and he just opened the doors and said, “Come and get it!” You know, before you always had to have a requisition for everything? Well, we went in there and we got great big sides of beef, everything you could think of. My job was ammunition, and I went to Mr. Miller and said, “What should I get?” Ed said, “Gee, I don't know. Ask the captain.” So I went up to the captain, and the captain said, “You take all the ammunition you can.” “Fine.” So we loaded on about double the amount of ammunition. If I recall correctly, we were supposed to have fifteen hundred rounds of five-inch, and I think I had twenty-eight hundred rounds of five-inch.

Donald R. Lennon:

Good thing they didn't hit the ammo-dumps.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, that's right. Or the fuel dock. That would have been terrible. Then I brought aboard a depth charge. We had a depth charge locker down below that would hold about sixteen depth charges. We filled that, and then we filled the racks, and then we put some on deck. So we had about fifty depth charges on board. Then a bunch of guys came down and they said--I was on the quarterdeck, maybe I had the deck, I'm not sure--they said they wanted to see the captain. So I took them up to the captain. There was something secret. And the captain comes down and said, “These men are going to do something to the torpedoes. Let them do whatever they want, and don't ask any questions.” So they came down, took out all of our exploders and put in new exploders. They didn't tell us what it was, and off they went. And those were the Mark VI

exploders. They were all so super-secret nobody could know about it. After we got to sea, the captain told us that these were new exploders that would blow up under the ship, and that they were just the thing to have.

Then we had men start trying to straggle on board. They asked if they could come aboard. They said, “Our ship is lost.” So we took on about twenty to twenty-five. We took some people from the SHAW, from the battleships--the OKLAHOMA and so forth, I guess the ARIZONA, I don't remember. But we took them aboard, and they didn't have any clothes or anything, so we scrambled around and got them stuff. Of course, one of the main problems was the psychological problem of what happened up in Honolulu. A lot of these people had families, so they would get on the telephone to find out, but it turned out that nobody got hurt and apparently the news reports were not accurate.

After we loaded up with everything we could carry, we went out to the buoys north of Ford Island. We still had condition watches, with the gunsmen ready to go. Every once in a while, a machine gun would open up somewhere. Then about sunset, some airplanes started to come in and some people on Ford Island started shooting, so the airplanes pulled off and they went on around. I understand that somebody got shot down, but I didn't see it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, someone was.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

The next morning we were out at the crack of dawn, and we went out, formed up, and moved up north of the island and operated up there. Rough as hell up there, and cold. We were trying to shake down all these new people and get everything organized, and we stayed up there for about a week. Then we came on back in, and this time when we came in, we got about another thirty or forty men who had orders, but they didn't

have any uniforms. They had volunteered on the seventh or the eighth of December, mostly in Los Angeles, and they just packed them up and sent them out, and we had them come aboard in civilian clothes. So we just had to integrate them into the crew, and that's what we did. We went from a crew of 150 to a crew of about 200.

Donald R. Lennon:

Could you use that many men?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh yes, condition watches. You see, you can use a lot of people on condition watches because you need ammunition handlers as well as pointers, trainers, and loaders. And you need extra lookouts. So we needed the men, we could use them. Of course, these people didn't have any training, and they also didn't have any uniforms. We had one guy who came aboard that was seasick, and he couldn't get over it. The chief boatswain mate said, “Oh, I can solve it.” He gave him a broom and said, “You sweep the deck. Just sweep the deck all day long.” This guy is sweeping all the time, and would just stop and puke over the side. And he just couldn't get over it, so the next time we got into port, which was about three weeks later, we just had to land him because there wasn't any way that he could make it. But that was the way the war started.

The feeling of everybody was one of shock and anger. We wanted to avenge those people and we weren't smart enough to realize that we had observed very skillful naval operations. They had come in, hit hard and effectively, and gotten out. And everybody said, “Boy, too bad that they caught those ships at port. If they caught them at sea, they'd have sunk them all.” I mean, the Japs had torpedoes that worked. They had first class pilots, first class airplanes, first class carriers, very good battleships, and very good destroyers. And if we tangled with them with our torpedoes not working, man oh man, it would have been a much greater defeat than Pearl Harbor was. But we didn't

know that, and our attitude was, “Let us at those Japs! We'll fix their clocks!” and all of that. Well, of course, we didn't know what we were talking about.

After steaming around north, towards the end of January, we went south and went down towards Samoa. We got down, I remember, on the equator steaming along, and I saw a whale shark. We came right by a whale shark. A whale shark is an amazing thing. A whale shark is thirty feet long and five or six feet in diameter. It was just lying on the water there, and we steamed right past him. Didn't seem to bother him. I remember that. And that night, we were right on the equator. That night, they told us we were about to make a raid on the Marshall Islands, and they would distribute the operation order the next day. And they did, and an SBD came by and dropped our operation order on a line, and it went across the fo'c's'le and we hauled it up--man it was in a bag. We found out that we were assigned to bombard Maloelap Island on Jaluit Atoll. I think that's right . . . yes. Maloelap. I think that's right.

We were to go in with the CHESTER and the BALCH. The BALCH was squadron leader. She was an 1850, and she had only surface guns. She had six five-inch and three double mounts, twin mounts. We had four five-inch in singles and the CHESTER had eight five-inch twenty-fives. The CHESTER had a 1.1, and so did the BALCH, 1.1 four-barrel machine gun. We had the rest of it. We had fifty-caliber; we didn't have any twenty-millimeters in those days.

So we went in to do our bombardment. We got in there just about at daylight, and I think we were about 10,000 yards out. And we were told that Maloelap was going to be built as a seaplane base. It had a couple of ships in there, and they were working on an airfield, but it wasn't operational. They wanted us to knock out the fuel tanks and things

like that. We had a bombardment plan and so we opened and we fired our rounds, and the CHESTER was firing her's. As soon as we opened fire, or very shortly thereafter, all of a sudden fighters started coming off of one end of this thing, and bombers started coming off the other end. Hey, this was not a seaplane base, this was an airbase! So we finished our rounds and we started our retirement.

Donald R. Lennon:

They didn't attack you though, huh?

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Oh yes they did, this is when they started. And they came out, and they would come out, and these were Nakajima 97 fighters; they had fixed landing gear. Each of them carried a pair of 100 kilogram bombs. And there were 200 pound bombs. They would come in pairs, and when we would start shooting at one of them, then the other one would attack. Then we would shift back and forth. So, we were being attacked constantly by these fighters, and we were shooting at them with fifty-caliber, trying to get on them with five-inch, but it was almost impossible. You see, you didn't have a slew sight in that director up there, and you had to be trying to coach your trainer to get on. Ed Miller turned out not to be a very good combat officer. He got frightened and didn't act well and couldn't make up his mind. So we didn't do much, except we got off only a couple of shots with the five-inch--the rest of it was fifty-caliber. But the captain kept going at a high speed and maneuvering, and the bombs would hit close aboard, and we got splashed. I actually got wet. My job was on range keeper, and we kept the door of the director open because it was so hot in there. So I'd be hanging in there and my back got wet with saltwater a couple of times by these near-miss bombs. But nobody got hurt. They didn't hit us. The same with the BALCH and the CHESTER.

We were steaming on out. The big event was when, all of a sudden, a formation of about ten or twelve twin-engine bombers, in a V-formation, were flying towards us. And we spotted them, and they were at 10,000 feet. We got a perfect solution on them, and we opened fire. We had the new mechanical time fuse. These are supposed to be much better than the powder time fuse on the five-inch. Moore, who was on the range finder, he could see everything. He had binocular vision--stereo vision. We fired, but we didn't get any bursts! And we were firing. We would run away (?), and we were firing only the F-2 mounts because the two forward mounts couldn't bear. They were firing only the after mounts. We were getting no bursts, and he said, “No bursts! No bursts!” And here they were coming in on us, and then all of a sudden, he yelled, “Oh, it's falling like snow! The bombs are just coming down!” And they let go, and we hadn't hit a damn thing. So I looked out there, and here was the CHESTER steaming along. These bombs hit, and I said, “Oh man, there goes the CHESTER.” The ocean was just completely covered with spray from the bombs, and here comes the CHESTER charging through, and it hadn't hit her!

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm sure they were about as shocked as you all were.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, no, that was the beauty. They weren't any better than we were. And then, another little Nakajima came out, and he went for the CHESTER. I watched him, and he went down, and he let his bomb go, and he missed. He turned around, still on his tail, went right back out, and he came around, and came down the second time and hit her right in the middle.

There was a big flash, and some fire. And they got the fire out pretty quickly. I don't think anybody was killed, but they had a couple people wounded. The ship was

damaged because of fire. The fire got one of the airplanes. The gasoline from one of the CHESTER's airplanes--it caught on fire and burned.

So then we went rushing back in and went back to Pearl. That was the first act in the war. I think it was something like the 28th of January or the 31st of January, 1942.

Well, after that, then we went back to Pearl. I don't recall many details of it, but we went out on our next operation at the end of February. The operation was to attack Wake. By this time, I think the Japs had taken over, and the Marines had surrendered. I'm sure the Japs were in command. So we went out, and the ENTERPRISE sent in air attacks, and in this case, we were in the . . . I guess we had at least two cruisers shooting, and we were the first ship in the bombardment group. I'm not sure where the BALCH was, the squadron leader, but she was there. I guess maybe the BALCH was on one bow and we were on the other bow. We were on an inside, engaged bow towards the island, and we were on an easterly course. We were firing to starboard. We went in, and we opened fire at the normal time, and this time we hit a few things--fuel tanks, and things like that. There was quite a lot of stuff going on. The ENTERPRISE planes were in there, but all of a sudden, we started getting attacked by Zero ? planes. These were very maneuverable planes, and they were even more skillful than the ones that attacked us before. We were in the most engaged position up on the starboard bow, and we were maneuvering to keep from getting hit. Again, bombs were hitting all around, but they didn't hit us, and we didn't hit them. But we did some damage ashore, and after awhile their attacks stopped.

On the way out . . . during this, it must have looked pretty bad because the squadron commander, Commodore Connolly--who later was known as “Close-in

Connolly,” you might have heard of him--Admiral Connolly called up the captain and said, “Please report your casualties,” because he thought we had really been beat up. And the captain said, “No casualties,” and he said, “Please repeat.” He didn't believe it, but we hadn't been hit. As we went on out, we ran into a couple of fishing boats, little Japanese fishing boats. And we were sent to sink one of them. We went over, and the sea was a long achy swell, and so this fishing boat was going up and down. We expected to shoot one shot, hit the thing, and that would be it. So we started to open fire at about three thousand yards, and we didn't hit it! We'd shoot over and the boat would drop down, or a wave would come up in between us and trigger our projectile. So we didn't hit it. And the captain started getting mad. He had a terrible temper. He started cussing Ed Miller out, “What the hell is the matter here?” So we finally had to shift the guns into local control, and went in at about five hundred to six hundred yards. But that fishing boat was chugging along at about five knots on a course, and I guess the crew had abandoned ship before we got there. When we got in there, we finally started hitting the thing, and we'd hit it and it would be a big explosion of paper coming out of the thing. Finally, the captain said, “Cease fire.” And I guess they called us back. Big sneer in his voice, “You can't even sink a fishing boat!” That boat, when we last saw it, was still making five knots going along. It was wooden, and we hadn't sunk it. We had knocked a lot of chunks out of it, but that was the story. Some of us began to realize that our weapons weren't nearly as deadly as we thought they were. So that was the raid on Wake.

Donald R. Lennon:

That had to be demeaning to be firing away at a wooden fishing vessel and not being able to sink it.

Russell S. Crenshaw:

Well, it was absolutely devastating, and of course, everyone was totally embarrassed by it. But it was the way it was.