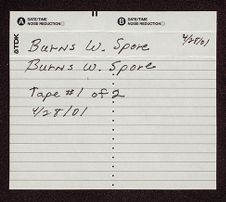

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #197 | |

| Archie P. Kelley | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 26, 2001 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Don Lennon | |

| Transcribed and edited by William J. Dewan | |

| Edited and proofed by Susan R. Midgette, and Martha G. Elmore |

Archie P. Kelley:

I was born in Washington, D.C., on July 31, 1918. My father, at the time, was Inspector of Naval Gunnery at the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, Lieutenant Commander Frank H. Kelley, Class of 1910. Later on, when I reported to the battleship WEST VIRGINIA, I was quite excited to see my father's initials on the big sixteen-inch guns, the turrets of the WEST VIRGINIA. He had inspected those guns. We moved as Navy families did, and we moved to the West Coast, where most of my young life was. Starting in Coronado, when dad was then skipper of the destroyer STODDARD, he had various duties up and down the West Coast, so I had schooling from San Diego up through Long Beach, Seattle, San Francisco, as a Navy junior. And I think that I can say as a Navy junior that it gives a young person a very broad outlook on life. Perhaps it may be one of the reasons that I was politically more liberal than some of my classmates, having moved around so many seacoast towns.

Then I was appointed to the Naval Academy by Senator Homer Bone of the state of Washington while I was at the University of Washington. I pledged Deke, the Deke fraternity. I was very much into the Naval Academy because of my two older brothers. One couldn't pass the entrance examination academically, and the other, who became a doctor, was almost legally blind. I sensed that my dad counted on me to follow in his footsteps. One of my fraternity pledge brothers had an appointment to the Naval Academy, from Senator Homer Bone. I discovered that he was fourteen days too old, because I had studied the entrance requirements very carefully. I had already passed the entrance examination the year before, a competitive examination in which a certain number of appointments were handed out to the sons of Naval personnel. I didn't receive an appointment but had passed the examination. When I found out my pledge mate was not qualified, I pointed out to him it would be very embarrassing to Senator Bone, and that we should get on the phone and tell him that I would be glad to substitute for him. And the Senator was delighted, because it would have been embarrassing for him to appoint someone who was not qualified. And that's how I got into the Naval Academy.

When I arrived in Baltimore, by train from Seattle, I had never been to the South before, and in riding the bus to Annapolis, I got on the bus at age nineteen, and walked to the extreme rear of the bus and sat down. Well every white person on that bus and every black person on that bus was furious that I was sitting in the back seat of the bus. In those days, the back seat of the bus was reserved for blacks. And I didn't know that at the time, but it was my first exposure to the racial division, which in those days occurred in the South.

Another funny thing happened when I had my entrance physical examination. The Navy, being a Navy Junior, a Navy doctor had removed my tonsils at age thirteen in Bremerton. In those days they removed your tonsils with a stainless steel wire snag, very much like the things you pick up a rattlesnake with. They hook it around the tonsils and then snap it shut, and then they jerk your tonsils out. He snagged my uvula. The uvula, we think, was put there by evolution to keep you from swallowing things that were too big for your esophagus. But anyway, they noted at my entrance physical examination that I had no uvula. The doctor examining me said, “This one is disqualified because he has no uvula.” And thinking very rapidly, I said, “But a Navy doctor in Bremerton, Washington, did that when he removed my tonsils.” Well, the doctors had a huddle, all the Navy doctors, and decided that I was qualified after all.

My first roommate was Charlie Trumbull, he liked to be called. And interestingly enough, he had met my future wife--neither of us knew it at the time--on a cruise previously with an uncle of his. But anyway, we broke up after our Plebe year because of our selection of language. I selected Spanish as a language, and he selected, I believe, French. As you may know, the Midshipmen are assigned battalions after Plebe year depending on the language they select. So, we broke up at that time[note]. I did quite well at the Naval Academy, and stood at graduation at number 15, which is within the star rank. And that helped out later, on being selected for MIT.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine being a Navy Junior, a lot of what went on came natural to you, didn't it?

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes it did. The Navy discipline and customs, the procedures were no problem for me. And I think I was prepared for the discipline part. So I had no problem with that. I had done quite well in high school, so I didn't have too much trouble with the academics.

We had an interesting point in history, we had one of the first blacks in our class in the history of the Naval Academy. His name was Midshipman Trevers. And coming from the North, years later, I tried to get the class to recognize him. He was, unfortunately, hazed so severely by the upper class that he resigned. But I know that our class, when as Plebes, when he would march in the mess hall, we felt a good deal of empathy for what he was going through.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the class has never agreed to include him as a former member?

Archie P. Kelley:

No, we could never get agreement, particularly between the southern officers and northern officers. In fact, I wanted to invite him to this very reunion if he's still alive.

Donald R. Lennon:

He's still alive. A historian, and I can't remember the man's name, sent me a copy of an oral interview he did with him.

Archie P. Kelley:

You think he is alive?

Donald R. Lennon:

He was three or four years ago.

Archie P. Kelley:

That's interesting, yeah. At graduation we were allowed to select our assignments. Our class standing had a good deal to do with the duty that we selected, and I picked battleships in the Pacific Theater. And that's how I wound up being assigned there. However, an interesting thing happened before. We were given, I believe, one month's leave before reporting to Pearl Harbor. This was in the middle of winter. We graduated on February seventh, as you know. My father had been skipper of the cruiser MILWAUKEE and the city of MILWAUKEE during their winter festival in 1941 decided

they would build a giant replica of the cruiser MILWAUKEE out of snow. They built this full-scale replica of the cruiser MILWAUKEE out of snow, and asked the Navy Department to send a representative to their winter festival. They selected dad, having been recently skipper of the MILWAUKEE, and then dad asked them if, since I had just graduated, if his son could be designated as his aide for this event. So, dad and I attended it, and I had the privilege of escorting Miss Wisconsin (laughs) . . . during the festivities.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a model was it?

Archie P. Kelley:

It was a full-scale model, enormous. They used bulldozers and shoveled snow for weeks and patted it in place, it was a beautiful replica of the cruiser MILWAUKEE. So I don't think the Navy Department realized what a big event this was for them, but anyway it turned out very nicely.

I had been dating a girl in Minneapolis during my various leaves. Dad had had various duties as professor of Naval Science and Tactics; he was the Navy's number one “starter” of Naval Reserve Officers Training Units. He started one at the University of Washington, and he started one at Stanford, and he started one at the University of Minnesota, and he started one at Marquette University in Milwaukee. And having a name like Kelley and five kids, they used to call him Father “Kelly,” although my family is not Catholic. We spell our name K-E-L-L-E-Y.

So shortly after reporting to Pearl Harbor . . . well, I spent the summer there. My future bride was the daughter of Admiral Ziegemeier [Henry Joseph], who was in the Class of 1890 and had won the Navy Cross in the Spanish-American War. He had died when Rosemary was six years old. But, he had been the first commanding officer of the battleship CALIFORNIA and my father was the gunnery officer under him. Later on, he

transferred to the battleship NEW MEXICO and Rickover, Lt. Rickover then, was a junior engineering officer under my father-in-law. Rickover, when he realized my relationship . . . the only comment he made to me about that was that he thought my father-in-law was a good Naval officer and that was about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, that's about as big a compliment as Rickover ever gave anyone, isn't it?

Archie P. Kelley:

That's right. The other officers on the NEW MEXICO--just last night we were talking about this--said that Rickover, in order to win the Navy E, Excellence in Engineering, had to shut off all of the coolers to the scuttlebutts, put disks in all the showers, and drilled eighth-of-an-inch-diameter holes in the shower to save hot water. He won the “E” for the NEW MEXICO, which made my father-in-law very happy, but he did it at the risk of almost a rebellion of the crew. (Laughs.) But that's the way he was. As I say, I'm probably one of the few Naval officers alive who admired Admiral Rickover as a Naval officer. He was hated almost as much as the Republicans hate Bill Clinton.

On the West VIRGINIA, there were four classmates: myself, Vic Delano, Pete Vail, and J. T. Hine. Neither Pete Vail nor J. T. Hine is here. Vic Delano's father was the Class of 1906; my father was the Class of 1910. Right after we arrived on the WEST VIRGINIA the commanding officer, who died from a wound on the [December] seventh, was Mervyn Bennion, Class of 1910, a classmate of my father's. So Captain Bennion called Vic and me among the four ensigns up to his cabin and said, “I know your fathers. I want to welcome you on board, but this is the last time I'm going to talk to you this way.” He made it very clear that there was going to be no favoritism on that ship, because of his relationship with our fathers, which I think was a fine thing to do.

We started out rooming in what they call the “J.O. Bunkroom,” which was called the “hell hole” by the sailors. (I think the crew probably feared going in there more than any place else, it was such a mess.) There were four of us Naval Academy ensigns in there and there were about five or six Reserve ensigns in the “J.O. Bunkroom.” We all hated the executive officer[note]. His name was Boyd Rufus Alexander, and at that time there was a popular song called “Alexander is a Swoose, Half Swan, Half Goose.” A popular song. And we played that song repeatedly in the junior officer wardroom to bug the executive officer. He had to come by and hear us playing this song. And we'd usually be singing it, “Alexander is a swoose, half swan, half goose!”

Well, when a sailor would come in and say, “Ensign Kelley, the executive officer would like to see you,” you could say something derogatory like, “Well, tell him to take a flying jump!” You know? The sailor would laugh, and walk away, knowing that you were going to carry out the order. But, if a Marine came in . . . and this is the difference between a sailor and a Marine . . . and the Marine said, “Ensign Kelley, the executive officer wants to see you,” and you said something derogatory like that, the Marine would say, “Yes, sir,” and go back and tell the executive officer exactly what you'd said. So we soon learned to treat the Marines differently than the sailors, as far as receiving orders from above.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's interesting. Is that because the Marine training is more rigid?

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes, the Marine training is extremely rigid. We were talking to a young Marine today who took us down to the mess hall; he was out of the Fleet, he had been a Marine in the Fleet and had been appointed to the Naval Academy. He was a plebe, outstanding

young man. But he told us, he said that looking at the other midshipmen, he said, “We were taught as Marines to show military bearing.” I was complimenting the way they were marching to lunch, and he said, “Well, we Marines think that's sort of sloppy.” (Laughs.) So yes, I think that the Marines do have a different standard, and they have the standard in combat. A classical thing, in the trenches, where troops were told to go over the top, the Marines would, without thinking, go over the top; but the rest of us might think twice about whether that was a smart idea. That was true of my Marine classmates. They all were really outstanding people.

That summer was really our last, what Shakespeare would have called a “salad summer.” Though not engaged at the time, my future wife was at the University of Hawaii. She had graduated from Punahou, an outstanding private school in Honolulu, and had half a dozen attractive friends--all eligible for dating. There were very few girls available out there. The Fleet was building up for an obvious war coming up, and the ratio of young officers to young women was just a very big number. Rosemary was very popular with my classmates because she could get us dates with many of her friends. Rosemary died two days after our fiftieth wedding anniversary. At least a half a dozen of my classmates here dated Rosemary and remember her very well. Because of the situation at Pearl Harbor, we had a very pleasant summer. The battleships would go out one week, and the aircraft carriers would go out the next. So we would swap liberties ashore with the aircraft carriers. Some of the light cruisers would operate with the battleships, and the heavy cruisers would go out with the aircraft carriers. Our girlfriends were dating both groups.

The night before Pearl Harbor, my uncle, Bruce Kelley, who was gunnery officer of the ARIZONA, Class of 1925, invited me over to his house on the far side of the island to play poker, along with several officers from the ARIZONA. His wife was also on the island. Both Bruce and I knew we had duty the following day, December seventh. I quit at midnight and went back to the WEST VIRGINIA and Bruce told me that he would follow shortly. I expected that he would be heading back to the ARIZONA. He called the first lieutenant of the ARIZONA, however, who was a bachelor, and got him to swap duties with him. And of course, that person was killed on December seventh. Bruce felt guilty about that for the rest of his life.[note]

At 7:45, Ensign Roman Brooks, who was a senior ensign, Class of 1939 or 1940, and was the junior officer of the deck that I was to relieve, announced, “Away, fire and rescue party!” He had seen some bursts of fire and flame on Ford Island, but didn't know what they were. They were actually bombs dropping on the aircraft at Ford Island. That was the first thing we knew about the war starting. “Away fire and rescue party!” was the correct thing when a ship alongside you had a fire or fire on dock, and your fire and rescue party would leave the ship and then help out. Then immediately, he said, “General Quarters. Man your battle stations. No shit!” Later, all of us agreed that that was absolutely necessary, because all summer we'd been having people say, “General quarters. Man your battle stations.” Sometimes they would say, “This is a drill.” And sometimes they wouldn't bother, but we always knew it was a drill. So if he hadn't said, “No shit!” we would have thought it was another drill.

I started running. I pulled on my trousers . . . no shoes, barefooted . . . and my jacket, strapped on my .45 . . . and no cap. I started running to my battle station, which was on the lowest deck on the ship. I was the first one there. As Assistant Damage Control Officer, I turned on what's called the 1MC, the loudspeaker system, and announced, “Close all watertight doors. Set condition ZED.” That word is now ZEBRA, it used to be ZED in the phonetic alphabet. Each one of the battleships had apparently--according to the Japanese, I found out later--received the same number of torpedoes. We received seven torpedoes--one of which failed to explode--and three converted eighteen-inch shells as bombs, the major ordnance that hit each ship. It apparently sunk the OKLAHOMA, but the OKLAHOMA hadn't had a chance to set condition ZED, and flooded asymmetrically and rolled over. We flooded rather heavily on the port side and the inclinometer, which only went to seventeen degrees on the scale, went off scale several inches.

Just last week, I received a call from an editor in the Chicago area who wanted to know if it was true that the WEST VIRGINIA heeled over to twenty-five degrees. I said I don't know. I don't think so, because the inclinometer stopped at seventeen degrees, and it was off scale. I pointed out to him that I used to have a forty-five-foot sailboat. The standard sailing angle in a stiff wind was around nineteen degrees. Even on a forty-five- foot sailboat, that feels to your passengers like a very severe list. On a big battleship, seventeen degrees seems enormous because they seldom get in that kind of a list. I don't know what the angle of heel was, and I don't know where he would get his information, because only those of us in central station knew what the actual list was. We started to

counter-flood, and successfully righted the ship, almost righted it, but we also sank it by counter-flooding the starboard compartments.

Vic Delano, I don't think realized in his report . . . it was true all the telephones on the ship [were out], except one circuit, which was our circuit--the damage control circuit, the experimental circuit with sound power. You didn't need a battery system. You can imagine how that would work, the vibration of the disk with your voice created the current that transmitted the signal so you didn't need batteries. The batteries for all the other phone circuits on the ship were flooded with saltwater and so there were no communications anyplace except for the damage control circuit, which was the experimental circuit. I pointed this out in my report to the Navy Department, which we all made, and that was used, I found years later, in a lecture to midshipmen about the value of sound-powered telephones. This experimental phone circuit on the WEST VIRGINIA permitted us to avoid capsizing like the OKLAHOMA. I don't know to this day whether the other ships had that or not.[note]

Okay, so meanwhile, the compartment was flooding. As the Assistant Damage Control Officer, I had been the first to arrive, and after the Damage Control Officer had arrived and two or three other people, the door I had arrived through, I dogged down.

Shortly thereafter, I realized that the trunk, the space on the other side of the door, was flooding indicating the deck above us was flooded.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were trapping yourself inside the ship?

Archie P. Kelley:

Right. I thought we were trapped since I knew the deck above was flooded. Meanwhile, there were apparently three or four men who had come down after I'd dogged down the door, and they were frantically trying to undog it. You're familiar with the dogs on a watertight door? They move on a ramp, wedge-like, and there were about maybe six or eight dogs all the way around every oval-shaped door. One of those dogs was inverted, which means that it was actually holding the door partway open, and there was quite a flood coming through that. The men on the other side, we could hear them screaming, and they were frantically trying to undog the door.

Donald R. Lennon:

You can dog or undog a door from either side, I take it.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes. But I had sailors helping me dog it down. I looked at my boss, Commander Harper. Most of the men in the compartment were with Vic Delano, who had come from the main battery control, another compartment that had started to flood. They had all escaped into central station, our compartment, and then dogged down their door to the flooding Main Battery Control. So the door I was dogging down was then the only watertight door available to central station. I looked at Commander Harper, who was a few feet away from me, and he looked at me, and I could tell by the expression on his face . . . my unspoken question was, “Shall I open the door?” His face indicated he didn't want me to open the door. But all my life I've worried about that, because when we unflooded--unwatered--the ship later, we found their dead bodies there. And I realized that I was the one who had killed them. However, there were forty men on our side, so

the question is, “Could we have undogged the door rapidly and let the men in, then closed it against all that water pressure?” Well, almost everybody I've talked to said, “No, no way!”

The same thing happened on the submarine SQUALUS. And after all these years I read that a few months ago--that story. Only there, there were twenty-one men on the other side. When the SQUALUS sank, an officer, thinking he was the last one to leave the flooding engine room and get into the control area of the submarine, dogged the door down, and then realized a little later that there were other men that hadn't escaped from the engine room that were trying to get in. And again, there were about twenty officers and men on his side of the door and twenty-one on the other. All twenty-one of them were lost. They made the same agonizing decision, which, after all of these years, made me feel considerably better about that kind of a decision.

So the compartment started flooding. After about an hour, Vic asked, “My people aren't doing anything here, can we go on up the escape tube?” There was a cable tube about thirty inches in diameter that went from central station to the conning tower, which was still above the surface of the water, even though the battleship was sunk to the bottom in about sixty feet of water. Finally Harper said, “Yes.” By that time the water and oil was up maybe almost to our shoulders. And so, one by one, nearly forty men had to get out of there. Harper and I were the last two out. When I started up the ladder, Vic Delano was at the top, and he hollered down and said, “Tell Commander Harper he's the commanding officer.” And I thought, “My God, how can that be?” Because Harper was the third in command: the skipper, then the executive officer, and then the first lieutenant

is the order of command. I found out later that the executive officer had abandoned ship at 8:30 in his pajamas.

Donald R. Lennon:

He had just run?

Archie P. Kelley:

I guess he announced, “Abandon Ship.” I don't know the reason, except he may have thought Captain Bennion was already dead. Captain Bennion was dying on the bridge at that time, having been hit by a piece of shrapnel. So the executive officer, then a Commander Hillenkoetter, who later became an admiral, apparently declared, “Abandon Ship.”[note] And almost everybody within earshot of him abandoned ship and went to Ford Island.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't think the individual in command could leave until he was sure everyone else was off.

Archie P. Kelley:

Well, he may have thought that . . . everyone else within sight of him . . . not realizing there were a bunch of us trapped down below. No, as I was telling my wife, a big battleship is a world in itself. You can be up in the bow and write down one history of what was happening, and I can be in the stern and write down an entirely different history of what was going on. I think this is true in all combat situations.

But anyway, so that was the first “Abandon Ship.” Very early, maybe thirty, maybe thirty-five, forty minutes after the first attack. So most of the people on the ship had abandoned ship and gone to Ford Island. When I got to the conning tower, I looked

through the slits in the armor plating and could see the OKLAHOMA upside down. Forward and aft, I could see the remains of the ARIZONA, burning furiously. Good-bye Uncle Bruce, I thought to myself.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now how much of the ship was under water?

Archie P. Kelley:

Well, the main deck was flooded. I used to have a picture of that. Okay, here it is. (Showing picture.) As you can see, quite a bit of it is under water. The main deck is flooded.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's sitting on the bottom.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes, it's sitting on the bottom at this time. The whole main deck is flooded. There's turret three. Here's the conning tower, way up in here. So most of it was that way. The ship would normally draw almost forty feet of water, and Pearl Harbor was only about sixty, sixty-five feet deep. So it was down only twenty, twenty-five feet.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was it premature for him to abandon ship when he knew it wasn't going to be completely underwater?

Archie P. Kelley:

Well, my guess is that he had seen the ARIZONA blow up. Let me explain, munition-wise, the ARIZONA received probably the same identical ordnance that we did, according to Japanese reports on this. They [the Japanese] practiced this extensively in a harbor in Japan, with simulated battleships and aircraft carriers, with their torpedo bombers and their horizontal bombers. Our biggest battleships, the biggest guns were sixteen-inch. The Japanese were building the YAMATO, a giant battleship with eighteen-inch guns, which was still a year or so from completion. They took the eighteen-inch shells, armor-piercing shells, and converted those to bombs for horizontal bombers, knowing that they would easily penetrate the nine-inch turret tops we had. The sixteen-

inch gun battleships had, as a coincidence, sixteen-inch side-belt armor and nine-inch armor on top of the turrets, but sixteen-inch armor along the front of the turrets. The idea was that if this is a turret, that the enemy shells, which would also be sixteen-inch, would come in at an angle here and hit the base of the turrets. The base of the turret, or the armor belt on the side, which is what you really wanted to hit to sink a battleship, had to be heavy. But the turret top would be hit at a relatively shallow angle and therefore didn't need sixteen inches of armor. Nine inches was enough. So these eighteen-inch shells went through the turret tops of the ARIZONA and WEST VIRGINIA.

Donald R. Lennon:

And they had practiced all that so they knew exactly where to hit.

Archie P. Kelley:

They had allotted a certain number. I think the number was either six or seven, torpedoes for each ship. Each torpedo and bomber pilot knew that he was going to hit such and such a ship. The ARIZONA got an unlucky hit on a turret top that went all the way down to the powder magazines and then exploded and blew the ship up. We received almost an identical hit on turret three on the WEST VIRGINIA, but fortunately, it didn't explode in the magazine below. It did set a fire. There was a plane on top of the turret, and the aviation gasoline set fire to the turret and burned everyone in the turret. Perhaps sixty, sixty-five men were in the turret.

After we came topside, Commander Harper ordered me to fight fires back aft. There were no other officers visible at that time. Although we had several officers in the damage control party who were still working the lower decks and flooding the spaces on the starboard side as ordered on the sound-powered telephone circuit. He ordered Vic Delano, who was the only other officer in sight, to go forward and fight fires forward. So I went aft and stayed there fighting fires. Meanwhile, I was joined by Jonathan Hine,

another classmate. I don't know where Jonathan had been at the time, but he showed up on deck, and he and I fought fires until about 1:30 in the afternoon. At that time Harper declared a final “Abandon Ship.” We went over the side and were picked up by the SOLACE, by a motor launch from the hospital ship SOLACE. Both of us covered from head to foot with black fuel oil. Very thick, viscous stuff.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where would you be pumping water from to fight the fires on the ship?

Archie P. Kelley:

Good point. The battleships were . . . well, you can see here (shows pictures). There's the TENNESSEE. There's the WEST VIRGINIA, and alongside is the TENNESSEE. The WEST VIRGINIA had shielded the TENNESSEE from any of the torpedoes. The TENNESSEE was intact. No damage whatsoever. In fact, they even missed her with their horizontal bomb. So the TENNESSEE was fully in shape, so we strung hoses across from the TENNESSEE to the WEST VIRGINIA, and the TENNESSEE provided all the water for fire-fighting.

Donald R. Lennon:

Using water from the Harbor, it would be covered in oil and in fuel.

Archie P. Kelley:

The water inboard the TENNESSEE was still quite clear. Much of the oil in the harbor was coming from the ARIZONA. What I was saying was you couldn't have used the water in the harbor to fight the fires because of the fuel in it, because the surface would be on fire. Not unless you were taking the suction from well below the surface of the water. The engine room on the TENNESSEE was taking its suction well below the surface of the water, so there was no problem there with getting water to the hoses. The TENNESSEE also provided us, later on in the day, with coffee and sandwiches and stuff like that to help support the small number of people that were left onboard. I spotted my

Uncle Bruce over there in civilian clothes, and that was the first time I realized that he was alive, since I thought he would have been on the ARIZONA.

They took me over to the fleet landing and an officer there, who apparently was Admiral Kimmel's supply officer, his dispersing officer who was responsible for the Officers Club, was concerned about my condition, since I looked pretty bad with fuel oil from head to foot, no cap, and no shoes. The officers standing around in civilian clothes who had come to Pearl Harbor in an attempt to get back to their ships also stared at me in disbelief. Before that moment, I hadn't realized how horrible I looked. In any event, Kimmel's supply officer took pity on me and ordered me to go to the Officer's Club. He said, “You go to the club, close it, and lock it. Don't let anyone in until I return. You can stay there and clean up.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Why did he want it closed?

Archie P. Kelley:

Um, I really don't know. I guess he, or probably Kimmel thought, well, here we are at war. No one knew whether the Japs were going to follow up their success with a landing on the island and, in fact, that was one of the rumors going around. He may have been anticipating the kind of negative response that occurred later on the mainland; that our defeat was caused by too much drinking and hell raising by the officers.

Well, it turned out that my future wife's cousin, Bill Stermer, was the manager of the club and he was staying there with several Filipino servants. Bill welcomed me, got me some underwear, shoes, pants, and a shirt. After several showers, and much scrubbing, I finally got most of the oil out of my hair and skin. I was very lucky to have such great emergency quarters, since the club was well stocked with good food and beverages. The supply officer returned after several days, laid off Bill Stermer, and told

me that I would have to find other quarters, since the club was to be closed for an indefinite period.

Fortunately, Bill and I had anticipated this event and had already arranged to rent a small cottage at Waikiki for use until I received new orders from the Bureau of Naval Personnel.

Life was considerably different on Oahu under this wartime setting. The normal flow of civilian supplies on cargo ships and transports stopped and no one could get tires, spare parts, appliances, or even food not grown on the islands. All cargo space was used for military supplies. The island was under martial law. Everyone was issued a gas mask and required to have it showing at all times, though most of the younger set soon removed the mask and used the carrying bag for swimming trunks and towels. Gasoline was rationed and headlights were painted black with a dollar-sized blue spot in the middle of the lens. Civilians were not allowed to use cars at night, so Rosemary had to hide in the rumble seat when we went out at night to one of the blacked out night clubs. Because of the fear that the Japanese would attempt an amphibious landing, all beaches on the island had barbed wire fences and landing craft obstacles. We still went surfing at Waikiki, however, in spite of these changes.

Do you want to get into this kind of detail?

Donald R. Lennon:

Sure, sure.

Archie P. Kelley:

Okay, word got around, by word of mouth, mostly, that the WEST VIRGINIA survivors should meet in a little park they had near Pearl Harbor the following Tuesday. We were given a day or so notice. We met there with the executive officer and were given various assignments, immediate assignments. My assignment with two of the

senior ensigns on the WEST VIRGINIA was to go to the War Plans and Operations Office in Pearl Harbor and man a top-secret telephone circuit with the decoding people, the code breakers. We were to transmit information, sift all the information that was coming in, both on teletype and by telephone, that we thought would be of value and of interest to the duty officers. They would then act on it. There were several ensigns from other ships so there were finally five ensigns on this one telephone circuit. We stood watches, initially, four hours on, and sixteen hours off. There were five of us. Then we decided, well, let's stand eight-hour watches, and then get thirty-two hours off. Then we decided. . . . Well, by that time, the senior duty officer, who was a good friend of my father's executive officer, said, “No, you guys are not going to get away with this. You go back to four-hour watches.” So that ruined it. Our appetite was too big there; we ruined our own thing there. Sixteen hours off would have been very nice. But anyway, that lasted just a month or so, and then I was ordered back to the WEST VIRGINIA to help unwater it. By that time, the Pacific Bridge Company, the same company that built the San Francisco Bay Bridge, was contracted by the Navy to right the OKLAHOMA and raise the WEST VIRGINIA.

[End of Tape 1, Side A]I was ordered to the ship as--I don't know whether this was in humor or what-- the navigation officer of a sunken battleship. One of my responsibilities was to continue the logbook. The logbook on a naval vessel is a very sacred thing and it must be exactly right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of like morning report for the Army.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes, exactly.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was morning report clerk once.

Archie P. Kelley:

So every day I would write in the log, “Sunk as before.” Usually at sea, you'd say “Steaming as before at 14 knots in company with BatDiv 1, course 3-5-0. . . .” Well, I'd say, “Sunk as before, at Key Fox 5 at Pearl Harbor.”

Shortly after I went back on board, while walking through the wreckage, I noticed that there was a torpedo that hadn't exploded. What had happened was that after the ship heeled over, this torpedo had come on in above the armor belt. If it had hit the armor belt, it definitely would have exploded, but it came in above the armor belt and apparently was set back so gently among the twisted wreckage, that the deceleration wasn't enough to set of the detonator. I took a piece of scrap paper, the way you do as a kid, and with a flat piece of pencil I put it on the nameplate of the torpedo and gently rubbed it on out. I took it out to Rosemary's Japanese maid. You know, the Japanese on the island were never interned. Many of them disappeared for several days. They were scared to death that the Americans were going to intern them, but we couldn't because there were more Japanese on the island than any other race.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to say . . . there were so many.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yeah, no way. And they were loyal. If there were a few spies, they were associated with the Japanese Consulate. So she translated this information on the warhead and I gave it to a brother-in-law of mine, who was a Reserve Naval intelligence officer in Honolulu. That's how we got the first information on the size of these torpedoes. They were enormous. Made by Mitsubishi. In kilograms converted to pounds, I remember they were something like 1,850 pounds. At that time, our torpedo warheads were about 400 pounds. So those were enormous torpedoes and they were very

successful torpedoes. Whereas at that time, ours, as you have read, in the submarines and aircraft were not detonating. The submarine skippers would report to the Bureau of Ordnance, the Bureau of Ordnance wouldn't believe them--and this went on for months--that our torpedoes just weren't hacking it. At the Battle of Midway, our aerial torpedoes were not detonating when they went in against the Japanese carriers.

Then the Pacific Bridge Company came out and built a temporary caisson over the damaged side, because they were going to put the ship in dry dock and start pumping it out, unwatering the ship. Our job during unwatering was to take any valuable electrical equipment--didn't have solid state electronics in those days--and immediately, as the salt water was removed from it, flush it with fresh water and then dip it into a bucket of a special substance called Tectol, which was an oily-like fluid that got underneath the water and coated the object with a protective film. And that's the way the ordnance and the gunnery and the electrical equipment were preserved. One of the questions this guy from Chicago asked was, “How did you unwater and preserve the main propulsion motor?” And I said, “Well, I assume it was the same way we did the ordnance equipment, by flushing it with fresh water and coating it with Tectol.”

Then the ship was put in the dry dock. Before she went to the dry dock, I was onboard and was there when someone went down and found the four skeletons or bodies in the trunk right next to central station. I didn't want to look. Then I was ordered to a new construction destroyer in San Francisco and left the islands.

In San Francisco . . . now I had graduated from the Naval Academy the previous February seventh, just a little over one year, and here I was, a raw ensign and I was ordered to a new. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

But you probably felt ten years older.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes, and the Navy department thought so, too. But I was ordered as gunnery officer of a new destroyer. And the gunnery officer of a destroyer is the most important position next to the captain or the exec. The captain was the Class of 1925. So here he gets a gunnery officer, Class of 1941. Within a few years there'd be maybe four years difference between the captain and the gunnery officer, and here we had the difference between 1925 and 1941.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was the captain?

Archie P. Kelley:

His name was E. A. [Edward Alspaugh] McFall. We called him “Preacher” McFall, Class of 1925, same class as my Uncle Bruce. He wired the Navy Department, saying, “When will you send me my gunnery officer?” I'd already reported. They sent back saying, “You've already got him, his name is Kelley.” But anyway, he finally accepted that. (Ironically, when I left the Navy, when I resigned from Rickover's operation in 1956, then Captain McFall was the administrative officer at the Bremerton Naval Shipyard. Knowing my whole background, he wrote me a very nice final letter.)

Meanwhile, I'd called Rosemary. Rosemary by that time had a secret war job in the islands. They had allowed civilians in the islands to evacuate if they wanted to on Navy transports, because no one knew what the Japanese were going to do next. But the Navy had realized that if the Japanese had not bombed and sunk the battleships that the Fleet would have been stopped anyway in seven days because they would have run out of oil. It's funny that the Japanese never realized this. The oil was stored in above-ground tanks near Pearl Harbor. If the Japanese, instead of wasting their ammunition on the battleships, which were by that time obsolete, had simply bombed these oil tanks they

would have put the whole Fleet, including the aircraft carriers, out of commission for the length of time it took to get new tankers out from the coast. They could have sent their submarines over to the coast and knocked off our tankers. So they made a major strategic mistake in hitting the wrong target.

The Navy decided to start a crash program of boring an enormous cave in a mountain near Pearl Harbor. It was called the Red Hill Project. They hired a bunch of coal miners from the various states that have coal--Virginia, West Virginia, etc.--and these coal miners were digging this enormous hole.

Rosemary got a job as secretary to the manager of this project. She did not evacuate from the islands at that time. When I got to San Francisco, I called her (meaning to propose on the telephone) and told her to come on over to San Francisco. She then applied for evacuation and came across on the same ship that was carrying the survivors of the carrier YORKTOWN, shortly after the Battle of Midway had occurred. The survivors of the YORKTOWN came over on the same transport that brought Rosemary back to San Francisco. In fact, she had a date with one of the young officers in the Class of 1942 from the YORKTOWN the very night they arrived. So I had to go up to him in the Saint Francis Hotel and ask him to break the date, because I was going to marry the lady the following day. So we went to Reno and were married. You couldn't get married in California because it took two weeks. California had a venereal disease law that required testing and it took two weeks to get the answer. But Nevada would marry anybody immediately.

Meanwhile, the GANSEVOORT, the destroyer I had reported to, was finishing up, and we went to San Diego. Rosemary drove down, and we stayed at the Hotel Del

Coronado for nine dollars a night, including her meals, and the chit said Ensign Kelley's meals, when he was ashore. So then we practiced gunnery exercises off of Coronado for several days, and then shoved off for Hawaii.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this the GANSEVOORT?

Archie P. Kelley:

GANSEVOORT. Named after a famous naval hero named Guert Gansevoort. I never knew much about him.

An interesting thing, technically . . . we were ordered to Honolulu at maximum practical speed. Now the destroyer during trials had been able to do thirty-five knots. Of course, that consumes an enormous amount of fuel very rapidly. The engineering officer, who was the Class of 1937 . . . I was really the most junior head of department on that ship, which was a source of much concern to the captain . . . he had calculated that we could do no more than fourteen knots without running out of fuel. So we went to Pearl Harbor at fourteen knots.

Now, I say this interested me later on when I got into the nuclear power business, because the first nuclear powered destroyer, the BAINBRIDGE, could have run at thirty-five knots from San Diego to Pearl Harbor and consumed an amount of enriched uranium the size of a cocktail cherry. That is showing you the enormous difference. This is the real secret of nuclear propulsion for ships, their complete detachment from the need for refueling. Their ability to go around the world is one reason why we're less interested in the Panama Canal. Our carriers can go around the cape and drive on at thirty to thirty-five knots, night and day, almost indefinitely. The first nuclear aircraft carrier, the ENTERPRISE, was initially fueled for a fifteen-year service, and her second core was twenty years. The very latest submarines are never refueled. So, it's just incredible what

nuclear propulsion has done for combat ships. We were very dependent on oil. As I said, if the Japanese had only bombed those tanks, they wouldn't have had to bomb the battleships.

Of my seven combat actions, Pearl Harbor included, there were six more, some in the Aleutians. The very first Marine landing was at Tarawa. We staged from New Zealand, and I ran into my Uncle Bruce. My Uncle Bruce at that time was the gunnery officer of the NEW MEXICO. I ran into him at a bar in Auckland, New Zealand, and we were talking about the landing at Tarawa, and the bombardment. He said, “It's a stupid move.” The idea was that the destroyers were all going into the lagoon, at very close range, while the Marine landing craft would come in outside the lagoon, come in through the lagoon entrance. The destroyers would be in there firing at the beach, and then the Marine landing craft would go on in there, and we'd lift our fire, and they'd land. Bruce said, “Aw, it's stupid for the destroyers to go into the lagoon. We battleships” (there were four of them I think) “will sit out on the horizon and we will kill every fly, every mosquito, every ant on that island.” You know, bragging about the battleship gunnery.

Well as it turned out it was absolutely useless. The battlewagons, their shells-- most of them were fourteen-inch battleships--would land on the atoll, and bounce off the atoll and skitter off. You'd hear them like a freight train, skittering off on the ocean on the other side of the atoll. The Japanese were buried about twenty to twenty-five feet under masses of coconut palm logs and sand.

After we lifted fire, as I say . . . as I say, I was so close to the beach sitting on the gunfire director, that I'd see the Marines coming in, the landing craft, the gate would come down, and the Marines would come out. Then it seemed almost comical. They

would jump up in the air and fall back in the water. It took me several seconds to realize that they were all being killed by Japanese fire, that our gunfire was absolutely useless. Our horizontal bombers were also useless. That was before the Air Force, these were the Army Air Corps. They came in at about 10,000 feet, horizontally, and attempted to drop bombs on the atoll. And that was also useless. Most of their bombs went into the water on either side. I think we lost something like 1,700 Marines. It was a tragedy. But it was also a very good lesson for all subsequent landings. We had no spotters ashore at that time. No one was there spotting the guns for us. The next landings, Kwajalein, were very successful. We had Marine spotters, and they could really get our gunfire placed very accurately. Those landings were very successful, with minimal losses.

Donald R. Lennon:

At Tarawa, they were just shooting at random, were they not? They had no specific targets.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yeah. We'd picked out what we thought were targets and fired at them. Of course, we only had five-inch guns on the destroyer and the battleships didn't have much of a target other than the atoll. The problem with the battleships was they weren't far enough out and they were using armor-piercing ammunition--their trajectories were flat. And again, battleships are designed to fight other battleships, which is a bit obsolete.

Later on in the war, they developed what we call a radar fuse. We weren't allowed to use that. We had it on our five-inch shells, on our destroyers, but we were only supposed to use it against aircraft. It would approach an aircraft and as soon as it detected a proximity, it would burst and send shrapnel all over the place. But we found out later . . . in fact, I used them as gunnery officer of the GANSEVOORT and we found that it was a marvelous weapon against troops ashore that were hiding among palm trees,

where you really didn't know where they were. And we did successfully bombard a little atoll called Abemama. During the landing on Kwajalein, we used these influence shells and they would burst right above the palm trees, and put out a lethal amount of shrapnel.

When we bombarded Abemama, it was in the dark, and we had picked up a Marine officer. I didn't know who he was, but later on it turned out it was a classmate, Willie Hunt. We put him over the side, in a little rubber boat . . . we were off the island, in the dark, maybe two or three miles. Naval Intelligence had said there was one platoon of Japanese troops over on this little atoll. So we put the Marine over in a rubber boat and as soon as he reported to us the captain gave permission to open fire. He [the Marine] spotted [for] us with just a few spots--things like, “Right, five mils, and up, two hundred yards,” stuff like that. Very soon he said, “Right on,” so we went to rapid fire. Very shortly thereafter he said, “The job's done.” He came back on the ship and I still didn't know it was Willie Hunt, didn't find out until years later. So it was one of my own classmates spotting gunfire out there.

Then, just after Kwajalein, (and by this time, I had been to a total of six amphibious assaults) at Guadalcanal, we briefly struck a propeller against a reef while coming by Guadalcanal and firing. The captain got a letter of reprimand for that. A destroyer at high speed in shallow water squats, the stern comes down because you're creating an enormous stream there, and underneath the ship you're literally scrubbing water from under the ship. He received a letter of reprimand for not realizing that his destroyer would squat even though the fathometer was showing enough water for us to pass over. And so we damaged our propeller.

We went back to Kwajalein in 1944. And I had applied for the MIT course and received orders to go to MIT. There was a codeword in the orders; one said FAGTRANS, which means “first available government transportation,” the other was FAIRTRANS, which means “first available air transportation.” So if you were going to a very important job, you'd get FAIRTRANS, but if you were going back to school, the way I was, it would be FAGTRANS, which means any old slow tanker or whatever was going back to the States. So the yeoman, who was a good friend, made a typographical error and turned FAGTRANS into FAIRTRANS. I went ashore, and within fifteen or twenty minutes, I was on a DC-3, island-hopping on the way back to Honolulu. Then I took a Pan American clipper. In those days we were flying the clippers, which took, I think, thirteen hours from Honolulu to San Francisco. And that was the end of the war for me.

Later on, when Rickover interviewed me, he said, “Why did you apply for MIT?” And I said, “It seemed like the best way to get out of that war in the South Pacific.” He thought that was a marvelous answer. He half-expected me to say, “Well, ever since I was a little boy I used to take apart clocks and I always wanted to be an engineer, and therefore I wanted to go to MIT.” And I said, “No, that looked like my ticket out of the war.” And he liked that. The other question he asked me was, “How smart are you?” This was a common question he asked everybody; he asked that of Jimmy Carter. He had three of his officers with him. One of them was the number one man in the Class of 1940, brilliant guy, Lou Roddis. Another one was an officer I didn't think too much of. So I said, “Well, I'm dumber than Roddis, but smarter than so-and-so.” Rickover

really . . . this other officer was on his list, and he thought very highly of Roddis, so again, I had a perfect answer to his question.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now before, as we started recording, you mentioned the fact that you had requested a course in nuclear physics.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes. While at MIT, we were allowed one elective and I chose nuclear physics. Now at that time, in 1944 the status of our knowledge of the nucleus of the atom was still pretty crude. Remember, this all came out in this century. And Professor Robley Evans, who headed the physics department, was writing a textbook called The Atomic Nucleus. For years, it was and still may be one of the prime textbooks in western countries for physics of the nucleus of the atom. This was before color television, and Evans' book was still in draft form. Evans liked to say to his class that, with respect to general relativity, that its effects were only those at velocities that are close to that of light. Then he would say--back in the days when men would say it--that the normal housewife wouldn't see any evidence of relativity in her house. Well, I was thinking about that years later, and in fact, we were consulting Evans on one of the civilian jobs I had. And I thought, “Hey, he's wrong.” A twenty-five-inch color television set has an acceleration voltage of 25,000 volts, 1,000 volts per inch. And it turns out that at 25,000 volts an electron is 5 percent heavier than it is at low voltage due to Einstein's relativity. So it means that the deflection coils on a twenty-five-inch television set will not deflect the electron far enough to the right and left. In those days they talked about the pin-cushion effect on the edge of the tube. The early tubes . . . you remember they had magnets around them; you had to keep fussing with these damn magnets around the neck of the tube. Well, all of that could have been calculated if people had used general relativity in

designing these picture tubes. So Evans says, “You're exactly right.” He included that in the finished textbook as one of the questions in the back for the students: “Okay, give an example in the average house where general relativity is brought into play.” And of course the answer was in a high voltage color television set.

Donald R. Lennon:

They did not want you taking that course in nuclear physics at the time you applied for it.

Archie P. Kelley:

What?

Donald R. Lennon:

Weren't you ridiculed for wanting to sign up for that course?

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes. We came under the commanding officer of the post-graduate school, across the river here in Annapolis at MIT, and we had to request permission. So when I requested permission to study nuclear physics they came back and they said, “Well, we'd rather have you study something like business administration or psychology.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Something more useful.

Archie P. Kelley:

Something more useful. (Laughs.) Several of my MIT professors, it turns out later, including Evans, were involved in the Manhattan District [code name for the atomic bomb project]. One of them was our heat transfer professor. He asked the students in his class for their names, and when I said my name was Kelley, he misunderstood me. There was a codename that they were using for their consulting work in the Manhattan District that was something like Kellex or something like that. He said, “What did you say?” Later on I found that he had thought that I was giving him this codeword. But it was just a few months after that letter that they detonated the Trinity explosion, which was the first atomic bomb.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's talk about your experience with . . . our time's ticking away so quickly here . . . let's talk about your experiences with Admiral Rickover.

Archie P. Kelley:

All right. As I say, I joined him in early 1949. And at that time he had just politically been made--after a considerable struggle since 1938--the Bureau of Ships “honcho” for the development of nuclear power for submarines. One other classmate who is deceased, Jack Laspada, and I both were ordered to him at the same time. He sent us both to Oak Ridge where we were to study intensively nuclear reactors--and there was no such thing as reactor engineering in those days--but to study nuclear reactors under one of their people at Oak Ridge. I did and got a very high mark. All of his people had to take this course at Oak Ridge. I got a very high mark for which he was very happy. In fact, he used to have me do some of the calculations for some of the letters he wanted to write.

He had a rival at the Argonne National Laboratory named Walter Zinn. And initially, the Argonne National Laboratory had the ambition to do the first development of a nuclear power plant for submarines. And that's where Sherman Naymark in our class was sent, to be Rickover's representative at Argonne. But as it turned out Argonne had very little to do with it because Rickover soon engaged Westinghouse and the General Electric Company, realizing that the two top technical industrial companies in the United States would have to be brought in sooner or later to do some of this stuff, to develop all sorts of exotic electrical equipment and stuff like that. As it turned out Argonne didn't have much of a contribution to the program, even though at first it seemed as if they were going to get it.

My assignments consisted of the reactor control drives, the heat exchangers, boilers, and the pumps on both cycles. We selected two approaches: the liquid-metal approach and the pressurized-water approach. At that time, no one knew whether either one of them would do the job. The NAUTILUS was to be the pressurized-water submarine and the SEAWOLF, the second submarine, was to be liquid metal. And the NAUTILUS prototype was to be built at Arco, Idaho. And the SEAWOLF prototype was to be built at West Milton near Schenectady, New York, in a giant sphere.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you say the first one was going to be built?

Archie P. Kelley:

Arco, Idaho.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is this just a prototype?

Archie P. Kelley:

A prototype, a land-based prototype. The Navy owned 980,000 acres--that's a lot of land--above the Bear and Snake River in Idaho. Completely desolate piece of real estate. They had used this area to develop the influence fuse that I talked about earlier. It was a very secret fuse. They were in a remote place, and they would fire ammunition of all sizes up to the sky and test these fuses against towed targets and things like that.

So, one day Rickover called me in and then said, “We are looking for a place that we're going to call the National Reactor Test Station.” It had to be remote, preferably not too far from the Canadian border. And he said, “Kelley, I want you to get this property transferred to the Atomic Energy Commission.” The Atomic Energy Commission was to head up this reactor test station. Very good politics on Rickover's part because that would mean they had to finance it, too, whereas if the Navy took it over the Navy would have to finance it. The Atomic Energy Commission had much more money than we did. Plus the fact that it was to be used for testing all sorts of experimental reactors for

everybody: the Air Force had a reactor, the Army had a little reactor, and there were civilian prototypes coming up.

He said “Kelley, I don't care how you do it, but I want you to get this 985,000 acres transferred to the Atomic Energy Commission and you gotta do it by such and such a date,” which was two weeks away! I went in, I just raised hell, and finally got this damn thing done, and it was just incredible to get the Navy or anybody in the government to transfer that much property in two weeks' time. It was incredible. There were all sorts of objections, but we had a lot of power behind us, both in the AEC and the Congress; and it was transferred. And that became the National Reactor Test Station.

Westinghouse went along with the idea of building a prototype of the reactor, which they would design for the NAUTILUS in Idaho. But the General Electric Company refused. It was true that throughout our program Westinghouse from the top down was extremely cooperative with Rickover. They decided, someone at the very top of Westinghouse decided in the very beginning, and said, “We're going to cooperate with this man, and as a result we're going to get a lot of business.” This was true; they got the lion's share of the nuclear business.

The General Electric Company, however, seemed to have the attitude that the government program officers were customers and that they were the landlord, that G.E. was the landlord. It was as if we were the tenants and they would provide the facilities and we were supposed to tell them what we wanted and then they would go back and give it to us. But Rickover wouldn't work that way, he wanted to be in charge 100 percent. G.E. fought him all the way. G.E. finally got permission from the Reactor Safeguards Committee--it was headed at that time by Dr. Teller--to build a reactor north

of Schenectady “provided you build it inside an enclosure that will take the maximum conceivable accident.” And that turned out to be a 225-foot diameter sphere, the biggest sphere ever built in history. The West Milton sphere was so big that if you floated it on San Francisco Bay it wouldn't go under the Golden Gate Bridge, which is 185 feet above the water. This was 225 feet; it would have floated about 30 feet deep in the bay. The sphere had one side left open. The Electric Boat Company had the contract for the simulated submarine hull, and assembling the prototype machinery, which would be rolled into the sphere on rails.

There was a complete steam engine room and a load absorber to simulate what a propeller would have absorbed from the reactor. And GE had the responsibility for the reactor. The prospective crew for the SEAWOLF was ordered to the site for training. Jimmy Carter came as a prospective executive officer. The skipper, Dick Laning (Class of '40), was not yet ordered to the site. They arrived and were given a one-year education at Union College in Schenectady. Sailors and officers were given the same thing: a little advanced mathematics; and an introduction to nuclear physics; and a small amount of reactor engineering. So Carter's claim that he was a reactor engineer wasn't quite true. He had received the same course that these sailors and officers of all the submarines received. I was ordered to Schenectady by Rickover to head up the operation at the remote test site. Sherman Naymark, another classmate, was ordered to Schenectady in the office of the AEC manager there to coordinate the administrative work that the contractor would receive.

So I was a site manager responsible for the finishing up of the assembly of the SEAWOLF prototype, and the training of the crew, and the startup of the reactor, which I

did. And we finally went critical and it operated beautifully. In fact, it looked at first as if it was something that was vastly superior to the NAUTILUS prototype. The NAUTILUS prototype had already run. It had had troubles. Rickover wanted a one-hundred-hour full-power run, which was amazing. Most Naval ships are only given a four-hour full-power run on trials; Rickover said that's not enough for a nuclear sub. He wanted a one-hundred-hour run, full power. So we had a very successful, one-hundred-hour run with no hitches. Then, Rickover wanted a simulated trip to Australia submerged. We started that, which would have been something like, as I recall, eight hundred hours. But anyway, the steam generators started to leak. The Navy really has never gone into this much detail in saying why they scrapped the SEAWOLF. We had mercury in between the sodium and the boiler water as a detection fluid. We had double-walled tubes, and the gap between the water side of the boiler and the radioactive liquid sodium side had mercury as the indicator fluid. We discovered mercury was leaking. The big advantage with sodium is very low pressure, thin pipes. Mercury was leaking into the reactor coolant, small amounts, but it was bad news for the submarine. But they decided to go ahead. It was too late, so the submarine was built. But instead of mercury, which of course is very poisonous, they used an alloy of sodium and potassium.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they didn't try to find out where the leak was?

Archie P. Kelley:

Well, we were able to successfully stop the leak, temporarily, with an old-fashioned apartment-house scheme. It was very similar to what you put into a leaky radiator in a car. There's stuff they sell for apartment houses for the old steam heaters, when you have a leak in that system. It worked, it seemed to plug up the leaks. G.E. actually did some tests with gamma radiation and found the gamma radiation even made

the plugs harder. So that stopped the leaks long enough for the submarine to last for two whole years. It set quite a record during that time.

By that time, Rickover had decided the NAUTILUS was extremely successful, that pressurized water was his choice. So they took the liquid-metal plant out of the SEAWOLF and replaced it with a Westinghouse water plant, very similar to the NAUTILUS. That was the end of liquid sodium. The Russians, however, did keep sodium in their submarine programs, but had a number of very bad accidents with it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any comments about Rickover's idiosyncrasies that infuriated so many people? You said you liked him and worked well with him.

Archie P. Kelley:

Yes. Rickover's biggest problem with the Navy command was that he didn't work the way they liked to work. They liked to work gentleman to gentleman, manager to manager. Rickover liked to get down to detailed nitty-gritty and this was the source of much of his power. He and his staff had the most detailed knowledge of what a nuclear power plant should be like of almost anybody in the United States including the G.E. and Westinghouse people. But Rickover used this “weapon” of detailed knowledge of his own programs as a very successful weapon on the chain of command higher up.

In the Navy Department there were twenty different levels of authority between us and the Secretary of the Navy. Twenty levels! So theoretically, when Rickover wanted approval from the SecNav's Office, for, say, a big new budget item or something, he had to go up twenty levels. But the knowledge we had of the program, and the lack of knowledge that these other officers in the chain of command had . . . because even engineering duty officers, most of them spend most of their time in contract administration. Very few are sliding slide rules and getting into the detailed nitty-gritty

or talking to scientists the way we were about the details of the program. They really couldn't challenge him, and every time they attempted to do so, they usually wound up the losers, so finally they just had to go along with him.

As you know they tried to get him passed over. He was a captain when we started out, and when you're passed over twice for a higher rank you have to retire from the Navy. He had been passed over once for rear admiral and the Navy tried to pass him over a second time. But Congress loved Rickover, because when Rickover had a program to present to Congress, he would come in with four or five of us and with stacks of books, justifying what we wanted to do. Even a five-million-dollar line item was peanuts in the military. We would tell these senators and congressmen, “We'll justify this program down to a ten-thousand-dollar item if you want to. It's all right here.” And they'd believe us. The Air Force would come in with a twenty-million-dollar line item and some Air Force general would speak about it very vaguely and obviously not have much of a detailed knowledge about what it was, and it wasn't very impressive. So they loved Rickover, they loved the way he presented things, and he usually kept his promises.

Rickover insisted on each one of us keeping a budget. I was given a very small program--a small test plant, simulating the SEAWOLF system--and given five million dollars. It was to be 1/20th scale. Well, when it started to overrun, as often research would do, Rickover said, “No, goddammit, you've got five million dollars and that's it! You'd better get it right.” So what we did was just cut the scale down more and that did it. We came in at five million dollars and everyone was happy.

I think his support in Congress was very important. Also, the fact that the Navy had very little control over his programs, primarily because of the lack of technical

knowledge of the various officers in the levels of command up higher, helped. Rickover used the best consultants in the United States. He would get people like Edward Teller or Eugene Wigner, who designed the Hanford reactors, get them back in Washington for $150 a day. Peanuts as consultants! And Rickover would pick their brains and they would go over our programs and make incredible suggestions. They were very helpful. So there just was nobody that could match him as the program manager of a major program.

Oppenheimer thought it would take sixty years to go from the bomb to the nuclear submarine. Oppenheimer, with a thorough knowledge of the weapon, thought that the submarine problem--and he was right--would be much different from the weapon problem. A weapon, you don't care what happens to materials that are going to last for a millionth of a second. So he said sixty years. Teller, who'd known Rickover a little bit better than Oppenheimer and was impressed with him, said, “You can probably do it in ten.” Well, he did it in six! From 1949 to 1955. The NAUTILUS went to sea in 1955.

The other reason that the Navy didn't like him was that he was very critical of the Naval shipyards. For example, piping was procured by the Navy in various classes. Now a high-pressure steam pipe has to be a much higher quality pipe than a stanchion, which would be what we call furnace welding. The shipyards actually were mixing up their piping, so you could actually have a workman select a piece of stanchion piping the same size as a piece of steam pipe and try to weld it into a high pressure steam system.

High pressure piping, for integrity, is drawn seamlessly through a die. Furnace- welded piping is simply steel plate, which is wrapped in a circle and then the joint is heated in a furnace to produce a weakly bonded pipe. We had an accident on the

NAUTILUS during the early tests due to a piece of furnace-welded pipe in the steam system. It burst and scalded a number of workmen. Rickover made the Electric Boat Company replace all the steam piping on the submarine because there was (even today) no way to be absolutely sure a piece of pipe is not furnace welded. Rickover found that this sloppiness about the pedigree of piping was true in all of the naval shipyards. There are numerous other examples of shipyard practices and ship design that Rickover thrust upon an unwilling Navy and yet each of these made today's ships safer and more reliable.

The hatred of Rickover by Navy brass is exemplified in a statement by Chief of Naval Operations Elmo Zumwalt. He said, “The U.S. Navy has three enemies: the Soviets, the Air Force, and Admiral Rickover.” However, each time the Navy attempted to force Rickover into retirement, his friends in Congress would see to it that he was, instead, promoted. Finally, however, Rickover's enemies in the Navy and in civilian companies he had criticized were able to persuade President Regan to retire him.

After my job in starting up and testing the prototype for the SEAWOLF, Rickover wanted to send me to Arco, Idaho, to start up the aircraft carrier reactor prototype. At about this time I had a bull session with the other engineering officers in the Naval Reactors Branch. We all agreed that the future for us looked bleak as far as ultimately making flag rank since we predicted Rickover would live forever and the Navy's hatred for him reflected on down to each of us. Consequently, one by one, all of his original officer staff resigned.

At age 86, Rickover's health began failing. One of his top civilian assistants, Ted Rockwell, visited him at his bedside. Rickover said, “They tell me I'm dying.” Then after a minute or two he said, “I guess you are supposed to be embarrassed and I am

supposed to be scared. Hell, it's no big deal. I've already done it once. There's nothing to it.” Ted knew Rickover was referring to a stroke he had had at the office when an emergency doctor declared he was clinically dead. “Yeah, I died. There was nothing to it. No hellfire, no angels. Just nothing. I don't know why everybody's so scared of it. It's no big deal.”

Today, 40 percent of the U.S. Navy is propelled by nuclear power and as of last August over 1.2 million nautical miles had been steamed. The Navy has had over 5,200 reactor years without a single reactor accident. Rickover's career as unwanted czar of the nuclear Navy spanned seven presidents, twelve SecNavs, nine CNOs, ten chief BuShips, and ten chairmen of the AEC, ERDA, and DOE.

I would like to summarize my feelings about Admiral Rickover by saying that neither the U.S. Navy nor any other traditional organization can stand many men like Rickover in a single generation, and I couldn't work for more than one. But once in a great while, in a situation of critical importance, such a person is needed. The Navy's mistake was in failing to recognize this fact.

[End of Interview]