| EAST CAROLINA UNIVERSITY MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #128 | |

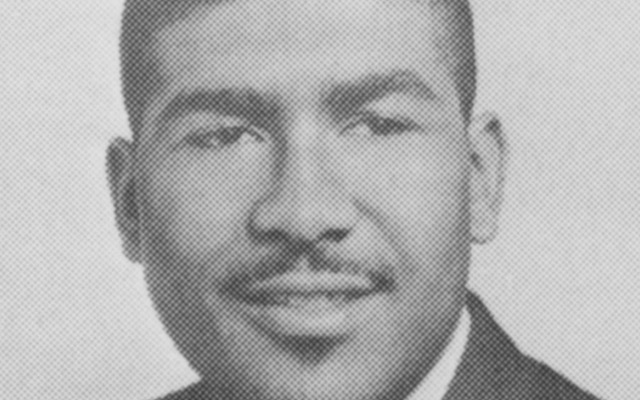

| Rear Admiral David H. Jackson | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| June 6, 1991 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Admiral Jackson, can you give me a little background about your family, your history, where you were brought up, and what started you thinking about the Navy as a young man?

David H. Jackson:

I was born in south central Arkansas, outside of a little village called Smackover. It was made famous by “Smackover” Scott of the Philadelphia Eagles, who played on one of the championship teams. He was also a Naval Academy graduate. I lived there for a short time and then in 1917, my dad and mother went to live with her mother and father, outside of a town called Norphlet, also in Arkansas. My dad and his father-in-law thought they should raise some cotton. At that time, cotton was a very lucrative form of business, because it was used in making explosives. Of course, this occurred at the end of World War I, so whatever shirt he had, he lost, but he had very little shirt to begin with.

My father was born of a poor family in southern Arkansas. He only reached the third grade in school. My mother reached the eighth grade. Interestingly enough, my mother and dad married when she was fourteen years old and he was about twenty-two.

After the disastrous business of trying to raise cotton, my dad then began to work in lumber mills in southern Arkansas. During the early days, he worked primarily as a laborer or handler of the lumber out at the lumberyards. He was not making much money at all. So then he moved up to a place called Arkadelphia, Arkansas. My brother and sister were born when he was working in little lumber mills around that area. When I was about eight or nine years old, we moved down to a place in Louisiana called Plain Dealing, which was about eighty miles outside of Freeport, and he worked in the lumber mills down there. Later on he moved back up to southern Arkansas, still working in lumber mills.

When the Depression came along in 1929, the lumber mill went belly up, and my father was out of work for two years. We existed on what he could make in little odd jobs around the place. What is interesting about that was that I had started working there when I was about ten years old. I was a water boy, carrying water from one group of workmen to another. When the mill went broke my father and I had to sue for the money that was actually owed to us. We got the money, but being a minor, I got my money first.

When I received my money, my mother took me aside and asked me, "Would you be willing to give your money up so your brother and sister could have some Christmas presents? I don't know if they know whether there is a Santa Claus or not. I can't tell. But would you give up your money so I could buy toys and things for them?" So I gave up my money.

As I said, Dad remained out of work for about two years. My mother's family had, back in years past, owned what they called an “interest” in the hogs that ran around through the bottom lands of the Ouachita River in Arkansas. People who owned rights to the hogs would go down there about ten times a year and catch every animal they could find that

didn't have its ears cropped. They would crop its ears, which meant that the hog then belonged to them. My dad and one of his brothers would go down there and any hog they could catch that didn't have its ears cropped, they would kill and bring it back home. We would salt it down and live off it. We usually had a cow and some chickens, so we had milk and eggs for eating.

At the end of two years, Dad got a job in a place called Junction City, Arkansas, right on the border of Arkansas and Louisiana. We lived there until after I went to the Naval Academy. I attended the Junction City High School. During that time, my dad was making a total of $2.25 a day. He had a big family; there were five of us. The house we lived in was furnished by the mill company. This was the time when Roosevelt killed all the hogs that couldn't be fed or taken care of by the farmers in the Midwest and shipped them around for the people to have to eat. I was about fourteen at the time. My mother sent me down to the place where they were distributing the meat and I was the one who had to go in and ask for a piece of the hogs that they were giving away.

During high school, in the summer time, I worked in the lumber mill with my dad. I made $.75 a day. The pay was seven and a half cents per hour for ten hours, working with the other men in the lumber yard, handling and trucking the lumber around, and stacking it, and so forth. One of the foreman took an interest in me and taught me how to operate one of the planing machines. I became what they called the motor operator when I was about fifteen years old.

I graduated from high school when I was sixteen years old. During high school, I took business courses--typing, shorthand, and bookkeeping. I was large, almost the same size that I am now, when I was fourteen. I weighed 160 pounds at that time. I played on the

football team while I was there. When I graduated from high school, I was number two in my class, the salutatorian, I guess they were called in those days. There was a girl who was the valedictorian, the number one student in the class. It was a class of thirty-five people, all from a small town in the countryside. They were trucked in by buses to the small school. I wanted to go to college but I didn't have any money. Mr. Murphy, who was the president of the bank, decided to take me in after checking on my typing and shorthand and things like that (He might have been some distant relation, because on my mother's side there were Murphys and Billuses. The first Billuse came down from French Canada and Nova Scotia and married one of the Murphy women in Arkansas who now own a lot of property. My mother is one of the distant ones, but we don't have any of the money.) I worked as a teller in that bank for a year and a half. During the time I was there, along came a bank examiner, someone who checked the banks to see if they were being soundly managed. He was a member of the Naval Academy Class of 1935 or '36. At this time, he was working as an assistant to his father who was the bank examiner. We talked about the Naval Academy and I decided that I wanted to go, but I had no hope of getting in, because I had no political influence to get an appointment.

Since I had been a football player in high school, I was able to get a scholarship with a little money and a job at a little school called Magnolia A & M, which was located in Magnolia, Arkansas, in the southwestern part of the state. It is now a fairly sizeable southern state college. I went there for two years and played on their football team. It was only a two-year school. At the end of two years, I had to hunt for something else. I was offered transportation to go down to LSU to see if I could make their team. I got down there and started looking around at the boys they had that weighed 175 pounds. I was only

5' 8” tall. They had these great big bruisers like Ganell Tensey(?), who later became a star football player in the pro league, and a couple of other big guys. After I had been hit a couple of times, I decided that this was not exactly for me, so I came back home.

At this time Congressman Wade Pitchens(?), who was the congressman from my district in Arkansas, had five men who were trying to get an appointment to the Naval Academy. This put him in a bind--he could only make one appointment. He had to announce that he was giving a competitive exam for his appointment to the Naval Academy. Sixty-five of us took it. I won and became the candidate from my district.

To attend the Academy you were required to have a $250 deposit. I didn't have any money to make the deposit, so I went to the man who I had worked for at the lumber mill and he loaned me the $250 to start my career in the Naval Academy. He gave me the money for the bus ticket and for the entrance deposit.

I didn't receive a notice to report to the Naval Academy. I knew it was going to be some time in July, so one day I just went out and got on the bus. I made my way to Washington and picked up my orders to the Naval Academy. I took the exams and entered the Academy. I guess it was June or July 26 or 27 of 1937.

While I was in high school, I attended church at the Baptist church, but my mother and dad didn't go. They said that they didn't have clothes sufficient to go to church in--which they didn't. Dad didn't have anything except overalls and canvas shirts. I went to church rather regularly during the time when I was growing up. I was the president of my class in high school, the vice president of my class at Magnolia A & M, and was selected as a member of “Who's Who.” I think there were six of us in class that were selected. They

knew that I had played football and basketball and was president of the Baptist Student Union, which was composed of all the Baptist students.

Donald R. Lennon:

Arriving at the Academy, you were in tough financial straits. How did that affect you? I imagine a lot of the guys there were not in that boat. How did you resolve those issues and work through some of those things? I imagine that was tough.

David H. Jackson:

It wasn't easy, but we had everything that we really needed right there in the Academy. We got the princely sum of $2.00 per month. I had started smoking cigarettes at the time, so I spent most of my money on buying cigarettes. I would have an occasional Coca Cola out in town, when we were allowed to go. We weren't allowed to go out very often. I managed very well. I never look back on this period with any great degree of unhappiness.

My attitudes about money now are governed by my attitudes toward money back in those days. For example, when I am using paper towels, I always take only one paper towel, and when I am using Kleenex, I only use one piece of Kleenex at a time. These are things that I do and I do them unconsciously. I find myself spending money and wondering if I should have spent that much. I guess that is the greatest effect it had on me.

It didn't have much effect back in those days. Even the guys who had the money couldn't spend it very much because we didn't have the freedom that the midshipmen have these days. We couldn't run around and do the things that they do. During my plebe summer, I think we were allowed one weekend off. We were allowed one Saturday to go into town during the entire time. At that time they had an arrangement at the store that there was a certain amount of money that we were given for our necessities. I could buy

cigarettes as long as I signed for them in the midshipmen's store. We got all our other things there, so the $2.00 I had was really to buy candy and a Coca-Cola now and then.

It became a little more difficult as time went by and I started trying to date girls. It was difficult for me to have a girl come up and want to go to a hop and not have money enough to buy her a corsage--a corsage at that time only cost about a $1.25 or $2.00--or to take a girl out in town to a dinner or something before a hop. Of course our pay went up to $4.00 as a youngster, $7.00 as a second classman, and $10.00 as a first classman.

The other problem I had was the business of getting money to go home during my first Christmas. There was a person in Arkansas who knew where I was and that person sent me the bus fair to come home that Christmas.

Interestingly enough, although I graduated something like thirtieth in the class, I almost flunked out my first year on the thing they called Descriptive Geometry. I just couldn't understand it. In fact, before I went home on Christmas vacation, my prof came up to me and said, "Mr. Jackson, you have a 2.55 grade average." Passing was 2.5. He said, "You are on the border line. What you ought to do is stay here during Christmas and take extra instruction."

Well, at the time I thought I might flunk out, and then I would never have the opportunity to go home to my little home town where I was the only person who had ever done anything like this. I wouldn't have the privilege of wearing my full-dress uniform and things like that, so I decided that I was going home. I thanked him very much for my 2.55 and said, “I think, Sir, I am going to go home,” which I did. I came back and, fortunately enough, I got a 2.495. That with my 2.55 gave me a 2.50 in Descriptive Geometry.

The rest of the subjects were reasonably easy. I made good grades in Math, English, Chemistry, and Physics, but that Descriptive Geometry, which is an introduction to the theories of drawing and drafting, I just couldn`t get. I would be given a figure and told to intersect two lines at this angle and draw the intersection. I simply couldn't understand it. I did very well when it came to the business of the actual mechanical drawing where I would take down a piece of machinery and draw and measure the parts of it live. I think I made a 3.7 or 3.8 or something like that.

The money was one of those things with which I think I got along better then than I do now. My mother and dad never had a bank account. My mother used to carry the money around in a handkerchief tied up in a little knot. They were good people, they gave their children the one thing all children need more than anything else, which is love. There was never any question about my own self worth. I had a sister and brother. My brother is dead now, but my sister is still alive. It was the same thing with them. We were a very close-knit family and did very well.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can't buy that love.

David H. Jackson:

That's right. You can't buy that. That was the main thing that we had. I guess some of the things I do and my values now come from back when I was younger.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any favorite stories and events, experiences that you can share with me from your midshipman days? Anything stand out that you remember?

David H. Jackson:

When I came to the Academy I was put in the room with a young man by the name of Moss. He became an aviator and died in a plane crash. Before he came to the Naval Academy, he had someone that he knew in the prep school he had gone to and he wanted him to be his roommate. He and I roomed together during plebe summer. At the end of

plebe summer, I started rooming with a man by the name of Strong. Strong was a nice young man but his heart really wasn't in the Naval Academy, so he bailed out at the end of the first term. Then I roomed with a man named Willie H. Fisher. Bill and I, of course, became very fast and wonderful friends and have remained so all these years.

I suppose my favorite things were the cruises. I got a lot of fun out of going on the cruises, even though I didn't have the money to spend like some of the other midshipmen probably did. I didn't pay much attention to that. One of my favorite stories is when Bill and I were in Copenhagen, Denmark. We got one of these two-seater bicycles and rode down the Riviera of Denmark, looking out and watching all the girls who were out. Interestingly enough, the girls at that time in Denmark would go out on the rocks and actually change their clothes, which was quite a show.

I met my wife when I was at the Academy. There were four new yawls for us to sail. I was given one of the first command cards for the yawls. I was tried out and got the BB, and one of the yawls was mine to ride around in. At the end of my second class summer I was sailing this boat in the Cedar Point race, which is an overnight race. We had to have what they called safety officers aboard and I had one by the name of Benjamin Fields. My wife's dad was in the Department of Seamanship at the time. He had been sailing as a safety officer for one of the other crews, but his crew didn't go on this race. Some other crew took over the boat that he had, so he asked me if I would take him along as another safety officer. I said, “Of course!” He came and we got the boat all set and ready in about four or five days. I was taking my September leave to do this. So were the four other guys in the crew who were my classmates.

One evening Commander Thornton asked us if we would come to his house to have dinner. He had a young daughter, I think she was in her first year going to Vassar College at the time. The five of us had a good time at dinner. The next day, for some reason or another, I decided that I would call her up and ask her for a date. So I did. She consented and her dad gave us the car to drive around in. She swears to this day that we five midshipmen went back to Bancroft Hall and decided that someone had to take Commander Thornton's daughter out, so we drew straws and I got the short straw. That is her story about the whole episode. We dated that year and the next year when I was there. In June 1940, when I was getting ready to go into first class, we had our ring dance. Before we got our rings, we were allowed to give our sweethearts a miniature as an engagement ring. All that year I had religiously save up my money to buy her a ring. When we went into the ring dance, there was a big replica of the class ring. We would go through it and kiss the girl that we were with. I got permission from my class to give her an engagement ring. That night, as we went through the replica, I gave her the miniature of our class ring as an engagement ring.

I had lots of fun sailing. I spent much of my time on the yawl, sailing it.

When I first came to the Naval Academy, I tried out for football, but I broke my ankle. They took me off and said that I would not be allowed to play football. I wasn't that good, I wasn't big enough. I had been a blocking back in college, and they tried to make a running back out of me. On my first trip of taking the ball and running into that big Navy varsity line, two guys grabbed me. One guy pulled one way and the other pulled the other way and they really wrecked my left ankle. I spent a lot of my time going back and forth to

the hospital, getting my ankle fixed up. It has had no residual effect on me. In fact, I think it is the best ankle I have at my age.

I did play baseball for a while. I couldn't make up my mind to choose between baseball and sailing--sailing was a spring-time sport, too. Max Bishop, the famous athletics guy, was the coach at the time. Max would have no part in my not attending every practice. I thought I was good enough to attend one practice a week and then play, but he would have none of that. He said I had to make a choice, so I chose sailing, which is what I did with my time.

One of my most memorable experiences was when we were in Le Havre, France, on our youngster cruise--our first cruise. When I would go ashore, I would just walk around and do things. Because of the fact that I didn't have much money, two of us went up Le Havre Hill, which is behind Le Havre, around ten o'clock in the morning. We sat up on top of the hill, looked around, and walked around on the hill. We bought a bottle of red wine and some cheese and bread, and that is what we had for lunch up there on top of the mountain. I've forgotten who it was that I went up there with, but it was a wonderful experience.

During my time at the Naval Academy, I went to chapel at the Academy. I didn't go into town to church parties. I didn't have any particular interest in religious things at the time. I was interested, but it wasn't one of those things that I felt any great pressure for. I was primarily interested in my studies. There was the Christian Fellowship they used to have on Sunday evenings. I would go to that quite frequently. However, I didn't have anything that you could really say was the conviction that had me going, unlike what I do now and what I did after I retired from the Navy.

I had a good time on my two cruises. Our first class cruise, in 1940, was down to South America and Panama. Of course, World War II had been going on since September 1939 at that time. We went down the East Coast, down to South America, and had a good cruise down to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It also took us over to Santiago--we had a good time with that. Our second class cruise was a real fine cruise on destroyers. I grew to love destroyers at that time. That is what I went to when I left the Naval Academy. Nothing really spectacular happened to me. I had a pretty routine life.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were out on your cruises approaching graduation, did you have any sense that we were going to get involved in the war? Of course, no decisions had been made at that time.

David H. Jackson:

I was pretty sure in my own mind that we were going to get involved. One of the things that happened was that in the fall of my first class year the KING GEORGE V, one of their big battleships, and a couple of their cruisers came into Chesapeake Bay and anchored out there. We went out to visit the English midshipmen on their ship in their wardroom. We were allowed to drink with them. When you were at the Naval Academy, you couldn't drink within five miles of the Capitol Dome, so we couldn't drink while we were at the Naval Academy. But they passed the word that we could drink so we went to the British ships and then brought them back to Bancroft Hall for dinner that night. While we were having our dinner, our consciences got the best of us a little bit. We decided what we should really do is to take up a collection and buy enough liquor to replenish what we had drunk out of their mess outfit. We did that. I think I put in a dollar. We went to the Officers' Club here inside the Academy grounds, bought some booze, and gave it to them to go back and refill their mess.

I thought we were going to get into the war--it was a foregone conclusion that we would, especially watching as things were developing over there. Watching Roosevelt do the business with lend-lease and the destroyers for bases, I was pretty sure that we were going to get into it. I felt it was a foregone conclusion that we would be in it sooner or later.

Donald R. Lennon:

They pushed up your graduation class. That was enough to get some people thinking.

David H. Jackson:

It sure did. That was quite an experience of being forced to get out in February rather than getting out in June. The professors and the people doing the teaching at the Naval Academy didn't take into consideration that we were only going to be there for four months; so what they tried to do was to cover the same ground in four months that we would have covered in eight months. We really had our noses to the grindstone in that particular period, trying to get the stuff in that we should have gotten in. It really was a tough bind.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your first assignment once you got your commission?

David H. Jackson:

The way that they assigned you to your ships was that you drew numbers. I drew number 390 something. It was like a lottery. You got your choice based on the number that you drew. It had been standard practice for many years to send all the graduates to cruisers, battleships, and aircraft carriers--the big ships. They all went to big ships with junior officers as mentors and learned the trade that way.

When we got out, we were given the choice allowing us to go to destroyers because they needed people in destroyers. I drew my number in the 390s . . . I think it was a class of 402 and 399 graduated . . . so I said, “Well, it is just fate. I am not going to reach the

standard to go on to a Navy career.” I put in for a destroyer in the Pacific Fleet. What I got was a four-stack destroyer, which had been converted to a high-speed minelayer. It was an old destroyer that had been built back during World War I. It was one of the last of the four-stackers. In my division there was the PREBLE, PRUITT, SICARD, and TRACY. The PREBLE, SICARD, and PRUITT were the last three of the four-stack destroyers built in World War I. They were DD-345, 346, and 347. They changed them to DM-20, 21, and 22. The one that I had was the PREBLE, DM-20. I was assigned to that particular ship on the basis of my lottery number. It had nothing to do with class standing or anything else. It was strictly to do with that number that you drew out of that hat.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you remember the time frame? When did you get out to the PREBLE?

David H. Jackson:

I left here on February seventh. I took a bus home and arrived two days later. I spent a good bit of time just running around and seeing high school friends and that sort of thing. Bill Fisher and I had decided that we would meet and spend at least one night in the Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco. So I took a train from down in Arkansas across the country to get to San Francisco. I got there and went to the Mark Hopkins Hotel. Fisher arrived and found out that the Mark Hopkins Hotel was the most expensive in the city, so he went and took a room at the old Palace Hotel in San Francisco and tried to get in touch with me. Somehow, whenever he called up they would tell him I wasn't there. I decided that I couldn't afford the hotel any longer, so I went down and found some of my classmates running around town. I started asking around, “Where is Bill Fisher?” I found out that Bill was in the Palace, so I called and finally got him. I went down and we joined up there.

We left San Francisco on the HENDERSON, which was a transport. We rode that across the Pacific. I was happy enough just to get out of the Academy, be a big boy, and to

be a Naval officer. I arrived on board the PREBLE one evening about, I guess, eight o'clock. The fellow who was the officer of the day was a man by the name of Lieutenant William Kaufman. We became very fast friends later on. I knew by looking at the roster that there was one man aboard who was from Arkansas. I thought, 'This is great to have a fellow Arkansan on board, to have some one to talk about it with.' When I got on board, the first question I asked was about this guy from Arkansas. He just looked at me in a peculiar sort of way and said, "He's not here anymore." I was smart enough even then to catch on that when a question was answered like that, then it was time to shut up. I didn't wait to find out what had happened. What had happened was that this guy had absconded with the funds from the ship's service and welfare funds, and he was being hunted back here in the U.S. Later on he was caught and tried and spent a lot of time up in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in the Navy prison up there.

So that is how I came on board, asking about the guy to see if I had known him. He was in the Class of '38, I think, back in the Academy, so I had known him a little bit. They called him “Punchy” because he had been on the boxing team back in the Naval Academy. But he had absconded with the funds. It took me a little bit of time to get over the fact that I had come on board asking about the wrong guy and asking the wrong questions.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were your first duties on the PREBLE?

David H. Jackson:

They had only two or three officers who could stand officer-of-the-deck watches at that time. They had a couple of officers who were Reserves--had come in from the Reserve program--who only had ninety days of training as Naval officers. My first assignment was as the mining officer, which was the “main battery” of the ship. I was told that within a week or so I was going to go to a place called the Mine School and learn how to become a

mining officer. I was assigned on the first day I was there to stand a watch with Lieutenant Roxie Holmes. He, at that time, was the chief engineer and Kaufman was the gunnery officer. I actually was working for Kaufman as mining officer in his department. I took this one shift from 12 to 4 in the afternoon after we got out to sea with Roxie Holmes. He made me do all of the things that we as midshipmen on the destroyer cruise had learned about watch-standing. I stood watch with him and he went down and told the executive officer, who was Lt. Andy Young, and the skipper, who was Cdr. Charles Edmunds, that, "Jackson is fully qualified to be an officer of the deck on this ship steaming in formation and doing the other things. He is smart enough that he knows if he gets in trouble to call you or the captain who is out on the bridge there. I therefore recommend that he be put on the watch list.”

The skipper said, “Well, what watch would he have?”

Holmes said, “Well, he will have the mid-watch tonight, the twelve to four." Twelve a.m. until four a.m.

Donald R. Lennon:

The one no one wanted.

David H. Jackson:

“That will be his watch.” The captain kind of demured a little bit and said, "Well, we don't know about this." He started to ask a few questions, then he said, "Okay, you can have the mid-watch tonight." I went on the watch list after that. I took my regular turn being on watch. Every time we came back into port, I wouldn't stand the day watches. I was over at the Mine School, learning how to be a mining officer.

We went through all the Fleet maneuvers. We acted just like a normal destroyer. We did like a normal destroyer did during all of the Fleet problems and the steaming and things like that. Every once in a while, maybe every two months or three months, we would

go somewhere and lay some mines and pick up some mines. For the extra pay, we were normally considered just to be a normal destroyer, screening aircraft carriers and doing convoy duty, things like that. I got lots of training of steaming in formation with the battle force. We steamed in the screen for a couple of battleships and we were frequently involved in Fleet problems.

One thing that happened to me was that I had such a good crew in my mining business and so forth that we got to “E,” which meant we were the best minelayers as far as laying mines was concerned in the Fleet at that time. I got the “E” and that was one of those things that started me out on the right foot. We were very happy that we got that award.

At that time I had become engaged to my wife. We guys on the ship used to go over and date the nurses at Fort Shafter. We had lots of time to go out with the girls who were there. The beaches around there were a lot of fun at that particular time. A young man from Texas, a Reserve officer on the PREBLE, . . . the first thing he did when he came aboard was to go out and buy himself a Plymouth convertible so he would have transportation.

Later on, the executive officer left to go back and pick up a new destroyer. The guy who was the chief engineer at that time, Roxie Holmes, became the executive officer. I became the chief engineer of the ship and continued in that duty for quite a while after the war began. All the time this was going on, we were exercising with the Fleet. We all knew that something was going to happen. We could read the newspapers and knew that things were getting pretty tense out there. We had several scares and we always steamed with the ships darkened. We actually stood one in three watches, and the guns had ammunition up by them--they weren't loaded but they could have been very easily. When we came back

into port we returned all the ammunition back to the magazine except a little bit up in a ready locker which was stowed under lock and key so no one could possibly get into it.

During all these times, I was learning how to body surf in the ocean, having fun. I also became the coach of the mine division baseball team. Mine Division One had a team that was entered into a little semi-pro league they had there in Hawaii, and the team was actually a member. They arranged the schedule so that we played the others in the Honolulu stadium whenever we were in port. We had night games and afternoon games and all kinds of things like that. We did pretty well. In fact, the team had done so well back in the past that one time they were in the playoffs for the championship of the league. I also played and coached the baseball team at that time. I had lots of fun with that.

We had a wonderful set of officers in the division. The commanding officer was a man by the name of Chillingworth, who was three-quarters Hawaiian. He had married a wealthy New England girl, and his family was connected with some of the wealthy people on the island. I have forgotten which one of the fine families he was connected with out there. He owned a house over on the Kailuah side, which is kind of on the bay over there. He used to take the officers over there once in a while in the evening for swimming at his beach and for dinner with him and his wife. They had no children. He took me over there one time and showed me one room he had in which he had stored liquor. He must have had three or four cases of Scotch and three or four cases of Bourbon. He had this thing completely and totally filled up. He wasn't an alcoholic. No way would you call him an alcoholic. He had his cocktail before dinner and maybe a drink or two after dinner. He just did not do any other drinking. He didn't drink, even when he was at home during the day.

I told him, "This is a fine storage you have here."

He said, "Dave, the Japanese are going to attack us." He didn't say attack Pearl Harbor. This was in July or August 1941. He said, "The government is going to put an embargo on and they are not going to have any liquor come to this island. I like to have my friends over and I like to have the stuff here. I intend to keep living here on the island with my wife."

His name was Charles Chillingworth. He became a vice admiral in the Navy. He was a very fine and wonderful guy. He had a great sense of humor. He was hard-nosed as all get out. He played on the Navy football team in 1925 when they went to the Rose Bowl. He was one of the first of the so-called barefoot kickers. I think he played tackle and also punted for the team, barefooted. I had a real good time with him.

On one occasion I almost got into trouble. We had these mine tracks back on the stern of the ship. When we didn't have mines on board, we loaded those tracks with depth charges, so we were the most formidable depth-charged-carrying thing around. We must have carried thirty-five or forty depth charges on those tracks back there, all tied down. When we dropped them, they'd roll on the mine tracks.

Part of my job also was the depth charges. I was the ASW officer--anti-submarine warfare officer, too. One night they had done some cleaning up and painting back there, and the chief who was in charge of the mines and things like that had left the depth charges unsecured. We had the boosters, the canisters, which were the firing mechanisms, back there in the locker so you could insert them and set them quickly; but we didn't have any of them loaded and ready to fire like that. Each one was just three hundred pounds of TNT in a steel case back there without an igniter or whatever, so I didn't inspect them that night, I trusted the chief to take care of things.

In the middle of the night we went from being in pretty calm weather to a pretty nasty little sea, which was tossing us around. Those doggone depth chargers got loose and started rolling around back there on the fantail. So, of course, I was the first guy called, and I was told to get back there. There is nothing more formidable and nasty-looking than to go back and face about fifteen depth charges rolling around on the back of a deck. They couldn't fall off the side of the ship, but they were rolling around on the back. I remembered the story--I forgot who wrote it (I think he also wrote Les Miserables)--about the gun being loose on the deck and flying back and forth and I recalled the guy had taken a mattress and thrown it beneath the gun carriage. What I did was I grabbed a bunch of life jackets and threw them down under there and stopped those depth charges from rolling around so we could go back there and do the business of tying them down.

Well, when we got them all secured, I had to go up and report to the captain on the bridge that we had gotten those things tied down. I have never seen a man who could kill with looks. He didn't say a thing. He just looked at me. I thought he looked at me for thirty minutes. I am sure he looked at me for only a short time, two or three minutes, but I could swear that he looked at me for thirty minutes. When it was over with, he said to me, "David, chiefs are good people but officers are responsible." I saluted and went to bed.

I didn't sleep at all. I guess that was the most horrible experience I had during that time. I guess the only thing that seemed like making up for it was not too long after that, we won the “Mighty E.” All the same, I never went to bed again without going through and looking at all the places and spaces that I was responsible for. It was the greatest lesson, I guess, that a man can ever have. Those things weren't really dangerous. There was no real way they were going to go off even if they had hit something or there had been a little spark,

because there wasn't any TNT they could get close to and the shock wasn't big enough to set them off. However, that mess being back on the stern of that ship rolling around was really something!

There is another good tale that I could tell about during that time before World War II started, before the Pearl Harbor attack. We guys around the ships didn't have much money, while the aviators, young flyers and the young jg's flying those planes, had all the money. We used to go back and forth to Fort Shafter and we would get dates with the nurses when the aviators weren't around.

One particular night, several weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor happened, we had a party down at Fort Shafter. Pretty much all the mine force's young ensigns were down there dating the nurses. Evidently some of them had made dates with the nurses and had said, “We will come back and see you and we want dates at this time.” They had made some dates with the nurses to coincide with the times they were going to be back in port. Well, of course, this was one of those “no no's”; you weren't suppose to talk about ship movements.

About five or six days later, the captain called me and my buddy up into his cabin and sat us down. There was a guy present who was in civilian clothes, and the captain started asking us questions about our dates and things like that. He asked the sixty-four-dollar question: “Had we made dates for when we were to come back into port?” Both of us said, “Absolutely not. We don't make any dates with the nurses, because the thing that is wrong with the Navy right now is the fact that they don't let us make dates with the girls for when we come back, so all those aviators get the dates.” We were both just choked up and said that.

He said, “Well, you have been accused of being at this party at which ship movements were discussed.” We said, “Captain, we don't discuss ship movements. We didn't make any dates, you can ask those gals. We have never made any dates for the time we were to come back in. In fact, you must have seen us dash off the ship as soon as we get into port, to the nearest telephone, so we can call up and try to make dates for the time we are in.” We said they could make up their own mind. The fact that we hadn't made a date beyond a certain time, I guess, they could say that the ship didn't go out at that time, but we hadn't told them anything. They believed us, so that was the end of that little escapade.

Another thing that happened was that one day when I had duty a week or so before Pearl happened, alongside the ship came this boat and handed me as the officer of the deck a letter. Of course, I opened it and it said, "Get up steam and be prepared to sortie immediately." I went in and called the captain and said, "Captain, I can't tell you why, but I need you on the ship right now." I called him and I called the executive officer. We got all the crew on board. We knew that something was happening. We knew that the world was in a terrible situation; they were having talks in Washington about trying to settle something between us and Japan. We knew something was happening, but we didn't exactly know what. We weren't privy to the message traffic; we didn't have the codes to break the message traffic flying back and forth.

The skipper and the exec came down and we got up steam and reported that we were ready to sortie. About two or three hours later they aborted, they cancelled the move. Admiral Pye, who put the alert out, is dead now. I never have gone back to look to see what the cause was for that particular alert that we got then.

Things were very tense the weekend of November thirtieth, which was the Army/Navy game. Dick Foster (the captain of the Navy football team our first class year, and who got his leg hurt in an airplane crash when a Connie and a jet collided over New York City many years ago) and I were at the Officers' Club that weekend. We had the radio on and the big board up there and we were drawing the diagram on the action going back and forth for the people who were there drinking and watching the board. We spent the next week sitting on pins and needles wondering what in the heck was going to happen.

On Saturday night, December sixth, I had had a little money left over, so I went into town to the movies with some guys and then had come back early to the ship. The guy who was the officer of the day, who had the day duty, was William Compter(?). I told Bill, “Bill, Cissy is pregnant and has been having sickness and things like that. Why don't you go home, I will take your duty. You go on back and be with Cissy. I will be relieved tomorrow about noontime. I have a date to go body surfing in the afternoon. I'll go do that and everything will be all right." We were undergoing some overhaul in the shipyard at Pearl Harbor at that time. So Bill left and I went around and looked at things, making sure everything was all nice and secure. I went to bed between twelve and one o'clock.

The next morning, I had two junior officers--two Reserves--who I had sent around to do the morning patrol. I was getting up around 7:00 or something like that to go have breakfast and look around myself. The ship had already been inspected for the morning watch. All of a sudden, a guy stuck his head in there and said, "Mr. Jackson, there is something happening." I dashed up topside and I saw the smoke coming over from Ford Island. Ford Island was here like this, the ARIZONA was here, and we were just across the channel like this, about five hundred yards away. We were in one of the slips over there

where we were tied up in a nest of destroyers. Over there was the cruiser HONOLULU directly behind us. I dashed up topside. I looked up and saw a plane going across our stern right there with a red ball, so I hit the alarm switch, which called us to General Quarters.

We didn't have any ammunition. Our ammunition was gone because we had been in the shipyard undergoing some overhaul work. I sent a guy back to the HONOLULU, the ship astern, to get some fifty-caliber ammunition from them so that we could start shooting these machine guns that we had. Within five minutes he was back and we had our guns loaded and we started shooting. We had a very narrow angle of fire going like that, but those torpedo planes were passing at the end of the slip. We were able to shoot at them, a very quick thing. I am sure we never touched any of them. It was the dive bombers that came over and hit the HONOLULU behind us. We did open up on them as they came down and my ship, as I recall, got credit for one assist and a kill. One guy, as he came down, dropped his bomb and leveled out like this to go across the top of the buildings in the shipyard. As he left, our gun fired up there, he trailed smoke and crashed over to the side of the road. We were given an assist on that particular plane.

My favorite story was that I didn't call my skipper. He lived in town, and when he got the word he came down to the ship and went up on the bridge. He got to the ship somewhere around 9:15 or 9:30. There was quite a time from when he got the word and the time he reached the ship because the traffic was all messed up at that particular time. By this time most of the action was all over. I was up on the upper flying bridge, controlling the anti-aircraft battery, pointing out targets. He called me down to the lower bridge and he chewed me out. He said, “Why in the hell didn't you call me?” Without thinking, I said in a rather calm voice, "Captain, what in the hell would you have done?"

Donald R. Lennon:

You got away with that?

David H. Jackson:

That was the end of that conversation. He said, "Get back to those guns." So I went back up to the flying bridge.

The day's end was rather hectic. We sent our people over to help cut into the bottom of the OKLAHOMA to get a few people out of there. We sent some people over to help with the fires on Battleship Row. We let our chief radioman go on the destroyer that was tied up alongside. We couldn't go out because we had one engine that was dismantled. The ship alongside of us was getting ready to go out so we gave our chief radioman to it and it did in fact leave the harbor.

It took me two days to account for all of our people and get sorted out as to where we had sent them and what had happened to them. I tried to keep lists of where I was sending these different people. I wasn't too successful, but finally, at the end of two days, I was able to account for all the people who were on our ship. We had no casualties--no wounded and no killed.

They did hit the HONOLULU, as I said, which was directly behind us. They hit her with a dive bomber. We were in a bunch of destroyers moored to a long pier and there was the RIGEL on the other side, which was a bigger repair ship. They dropped a bomb, which landed within the strip between us. It did not hit the RIGEL and it did not hit us. What happened on the RIGEL was that the splinters from the bomb actually penetrated the side of the ship and killed a guy who was lying in his bunk. Some of the splinters banged around us, too.

We also sent a party up to Lulu Lane to bring back ammunition to our ship and the other ships that were at the pier. There were all kinds of wild rumors floating around the

place about troops landing on beaches on the northwestern side of the island. One woman reported that there was a blimp overhead. A few things like that. That night the carriers that had been out to deliver planes to Midway and Wake came back in. They flew their planes in early and, as the planes came in to land on Ford Island, the whole damned harbor opened up on those poor guys who were coming in. We shot down three of them. I was able to keep our guns from firing that night; we didn't fire a single shot, but the sky was just lit up with traces and shell bursts, and three of our own planes were shot down.

We slept rather fitfully. I slept alongside a machine gun that night up on the flying bridge. We managed to get the ship kind of operational that next day. We got most things back to normal. It takes a very long time to get things back to a normal routine. All of the officers were required to wear a forty-five. I went out in town a few times to take care of a few things, wearing a forty-five around my waist and wearing two clips of ammunition in the little pocket beside the holster. It was not very comfortable to walk around with that doggone pistol at my side.

We went ahead with the overhaul of the ship. On Christmas Eve evening the skipper ordered me off the ship and down to the Moana Hotel. I was down at the Moana with a bunch of other guys. The submariners were being given the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, which was “THE” hotel, as the place where they would stay. The Moana Hotel is in that same compound. I had a rather nice, restful time. I just didn't do anything, didn't even go down to see a movie. I had a couple of drinks and dinner, came right up, and turned in. I slept for about twenty-four hours.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tired! How soon after Pearl Harbor did they order you out to sea?

David H. Jackson:

We went out as soon as we could get fixed up. Our duty was to patrol in a circle with other destroyers from Diamond Head around to Barbers Point. We did that until the early part of May. Then we escorted some tankers to Midway to be part of the support for the Midway fiasco. Then we and three other minelayers were given the task of laying a minefield around a place called French Frigate Shoals. It wasn't too far away from Midway. We were given the task of patrolling the minefield in that area to see what was going on around there. We weren't actually part of the action with the carriers at Midway itself.

Part of the Japanese plan was to have two seaplanes come to French Frigate Shoals, refuel, and go on and observe Pearl Harbor and the islands where the operating areas were to see if any of our ships were there so that their carriers could send planes up to get them. We are pretty sure that a submarine was supposed to surface at the shoals and refuel these two big four-engine seaplanes. We are pretty sure that the submarine sank in the minefield--we know that something went into the minefield and was sunk there. We also know that the Japanese didn't do the reconnaissance that they were supposed to. Recently they had a conference in Austin, TX, because this is the fiftieth anniversary year of Pearl Harbor. From May 8-11, they had all the Pearl Harbor survivors and Pearl Harbor historians in Austin to review what had happened in the build-up to Pearl Harbor--how Pearl Harbor happened and things like that. One of the Japanese who was there talked about how part of the Midway plan had been to do this seaplane reconnaissance and it didn't happen because they lost the submarine. So we got credit for being in the Battle of Midway.

When the Battle of Midway was over we were sent back into Pearl Harbor. We were there when the SARATOGA came through and we escorted her out, to get her on her way. I had gotten word that we were supposed to go back by way of Seattle up to the

Aleutians, where we would be operating for a while. I had gotten word to my wife that she was to be in Seattle over a certain week, that I would be there, and maybe we could get married at that time. So she went to Seattle, but I was five days late getting in because we had to stop to help escort the SARATOGA. She had been there five days and was getting ready to leave the next day. I couldn't get any word to her--she couldn't find out anything about me anyway--and she was up in the hotel room thinking, “I am going to leave, I can't keep on staying here.” All of a sudden, at three o'clock in the afternoon, she got a ring from me saying that I was there and I would meet her down in the lobby of the Olympic Hotel.

Donald R. Lennon:

When was this? What was the date?

David H. Jackson:

This was June 26, 1942. She had a Vassar school-mate in Seattle, the two of them had been talking, and they had been making arrangements for us to get married if I came in. We went up to the eleventh floor and met with some people there so that I could get the three-day law waived. We went and talked to some judges and congressmen and got the waiver. By this time, it was five o'clock in the afternoon, and the license place was closing up. Well, the judge who waived the three-day law called them up and said, "Would you have the side door open and let Lieutenant Jackson and his wife get a license to get married?" So between 5:30 and 6:00, we got down there and got the license. She had to pay for the license because the only thing I had was a $20 bill and he didn't have any change. She has never let me forget it.

Before we left to go get the license, there was a woman in the hotel who said, "Well, where would you like to get married?" My wife said that she would like to get married in an Episcopal church. She was an Episcopalian and I was a Baptist. This woman said, "It so happens that I am Episcopalian and I am connected with the Church of the Epiphany, which

is down here. We would like very much to have you get married there. There is going to be a wedding at 8:00 there and you can have your wedding before they do and use their decorations and all that stuff." We said, “Fine.” By the time we got everything set and reached the church, it was 7:00 and the guests had already started arriving for the wedding in the main church, so we got married in the chapel, which was down in the basement. She was given away by Bill Kaufman, who was the guy that I had relieved on December sixth. My best man was Sid Adams, my assistant on the ship. This woman had arranged for us to have a reception after the wedding at the house of a friend over on Lake Washington. It was a great big house. There were seventy-five people at this reception and we didn't know a single one of them. They had come there to be with us.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was nice of her.

David H. Jackson:

After we got through with the reception, we went back to the hotel. I had my smartest ensign's uniform on although I hadn't had time to get it striped. I walked up to the guy on the desk and said, “I would like to check Miss Annie Thornton out and I would like to check in Lieutenant and Mrs. Jackson." He looked at me as if to say, “You have got to be kidding.” I reached into my pocket, pulled out the license and the marriage certificate, threw it down, and said, "There by God, we are married!"

He said, "Well, we will give you the bridal suite." They did. They gave us the bridal suite, the top room of the hotel.

The next morning, there appeared at the door a young man with breakfast.

He said, "I am a reporter from the Seattle Times and I heard about your wedding and I want to get the story on you."

I said, "I am a Naval officer and I don't talk."

He said, "Mr. Jackson, I know that you came over here on the USS PREBLE. I know that when you leave here you are going to go to the Aleutians. I can go write a story and include things like that, but if I am going to write a story about you, I would like to have ' your' story."

I said, "Yes sir, come in." He came in and we had a nice hour's chat. He took some pictures, went back, and produced a very nice beautiful story with a picture of us.

We were together for five days. We hadn't seen one another for a year and a half when we got married. We got married and I was there for five days, then I left and went to the Aleutians and didn't see her again for another year and a half. Long time between dates!

Donald R. Lennon:

When you went back, were you still on the PREBLE?

David H. Jackson:

Yes, still on the PREBLE.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then you went to the Aleutians?

David H. Jackson:

Yes, we went to the Aleutians.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you get involved in any fracas there?

David H. Jackson:

The Japanese sent some planes over and dropped some bombs near us when we were in Kodiak. We also laid some mines and did some patrolling up there. I had some very interesting liberty on Kodiak Island, which was, of course, an old mining town. It was very interesting to walk around and see the old miners. I went fishing in the rivers for salmon and for Dolly Varden trout. I had a wonderful time fishing up there. I caught enough salmon one day to have a salmon-feed on the ship. There were 180 people on the ship and I caught enough fish for all of us to have good fresh salmon on this particular day.

We left there in August, went back to Pearl Harbor for a few days, then escorted the battleships down to Nouméa, New Caledonia, and out into the South Pacific. After that we became part of the invasion operation around Guadalcanal.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the time frame, do you remember?

David H. Jackson:

The time frame was from August 1942 through June 1943. In the time we were down there, we were never a part of the major action. We were on the fringes of all those battles off Savo Island. One night we ran from what we thought was a Japanese force, because we couldn't stop and fight them. We thought somebody was chasing us so we left at full speed. After we had been running for a while we heard some transmissions on the radio, which our skipper thought was a classmate of his. He grabbed his radio for talking between ships--the TBS, they called itand said, "This is Fred Stickney. I hear Jim so-and-so talking. I think you so-and-so's are chasing us."

The guy came back and said, "Yes, Fred, but we have been following you, not chasing you. We had to get out from up there, too.”

There were regular night battles around Savo Island. The Tokyo Express was a group of Japanese destroyers that would come down at night from the New Georgia Islands, which were north of the Solomons. They would come down and shell the beaches and sometimes would also offload some additional Japanese to fight the Marines in Guadalcanal. We had lost enough cruisers and destroyers in those battles for Guadalcanal that they decided they wouldn't send any more cruisers or battleships up there. They couldn't take a chance on getting beat up by Japanese torpedoes and things like that. So it was decided on this particular night that we were going to be sent in to lay a minefield of floating mines in front of the Tokyo Express. We had finished laying the minefield just as

they were coming around Savo Island. We didn't wait around. There were twenty of them--twenty Japanese destroyers. They went into the mines. We know that we got one Japanese destroyer and we think that we got two others in that group. Of course, when this started happening, they thought they were being attacked by submarines or PT boats, so they left without doing any shelling or anything like that. They turned around and high-tailed it back to where they were supposed to be.

We stayed in the Solomons and did a lot of escorting back and forth between New Caledonia and there. They decided that they would invade Russell Island, which was a little island north of the Solomon Islands. Guadalcanal is here and then Florida and Tulagi over here. About twenty or twenty-five miles north of them is a little place called Russell Island. The Japanese had been on the island and we knew that they were still there. We were to escort the landing force up there. We would leave in the afternoon about 3:00 and get up there that night around 8:00 or 9:00 at night. We had six or eight LCTs loaded with Marines and we were going to escort them to Russell and put them ashore that night.

By this time, I was the gunnery officer on the ship. There was a little inlet that went into the island. My job was to take a motor whaleboat and be the navigator. I was to lead these LCTs up this little river that came out of the mountains and get them to the place where they were supposed to be unloaded. I was the lead. Nothing but me and three sailors in this motor whaleboat. All we had were Thompson sub-machine guns; that was all we were armed with.

I was able to lead them in there successfully and get them unloaded. There was no opposition or anything like that. The thing that actually happened was that the Japanese were taking their guys off in submarines at the other end. The same time we were landing

on this side here like this, they were going off the other side; so we had no opposition to the landing operation. It didn't make it any less scary.

Donald R. Lennon:

I bet you were glad that you didn't run into anyone?

David H. Jackson:

We got the Marines in position and we repeated the operation for the next several nights. We were escorting about six or eight LCTs up there, putting soldiers and their equipment ashore, and then we would come back to Guadalcanal the next morning and take another group back up to Russell that night. It was like a shuttle operation. We got along fine, no problems. I was the guy who had to lead them up in there each time and keep them from running aground. It was no fun!

I've got to go back and tell you a story about Midway that I forgot earlier--one of the other things we did when we were preparing for the Battle of Midway. Kure Island, Laysan Reef, and a couple of other islands are east and west of the island of Midway. About a week before Midway happened, they decided they wanted these islands reconnoitered to see if there were any Japanese coast watchers there. What would happen was a Japanese submarine would come along and unload a guy with a radio so he could observe ship movements, aircraft movements, and things like that, back and forth and around this island where he was. He couldn't see very far but he was a forward listening post for them. There was some concern that the Japanese still had some people in these islands, so they asked us to go and reconnoiter. I was given the task of being the landing force officer since I was the only Naval Academy officer at that time who had had much extensive training in infantry tactics and doctrine. Also, I was unmarried at the time.

We loaded up the boat and they put me ashore on the first island. It was east of Midway. This island was one where the guano traders had operated. Guano was the dung from birds and was used as fertilizer back in the days before regular fertilizer.

There were several shacks on this island. We shelled the island from the destroyer and had some Marines from Midway come over and bomb the shacks. Didn't hit a damned one of them! We had brought some gasoline in five-gallon cans ashore with us when we landed. We set out like skirmishers in the infantry business and swept across the island. We started combing the island, seeing if we could find traces of any Japanese. I, being the brave young ensign in charge of the guys, wanted to show them I knew what I was doing. When we came to one of those buildings I would say, "Okay, you guys cover me now. I will go in and search the building and see what is in there.” Damn fool, I should have had one of them go in and I should have stayed outside the door. If there had been anyone there the others would have been left without their leader.

I think there were about three of these shacks on the island. I would go through and search the place, then I would come out and tell the other guys to pour kerosene on it and tell them, “Burn it." The last one I went into had some closets in it. I had a Thompson .45, a Thompson submarine gun, with me. As I was going in to open the closet--I was standing, getting ready to open the door--and it started to move. I just let it rip, “Bd-bd-bd-bd-bd!” like John Wayne. I really let that door have it. Then, as I looked down, there were two gooney birds, two albatross, walking out of the closet.

Donald R. Lennon:

Someone had a real good laugh outside, didn't he?

David H. Jackson:

They had a real good laugh out of that. We finished up that one and got. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you find any sign of anyone being on the island?

David H. Jackson:

We didn't find anything on that one.

I had not had the greatest of ease in recruiting people to go with me the first day. After we got back from the first day's run, the pharmacist's mate on board was ordered by the captain to give us some medicinal stores. We each got one of these miniature bottles of whiskey. The next day, when I got ready to go, I got all kinds of volunteers--they were standing in line! We went to the next island, to Kure Island, which is west of Midway. On this one we found evidence of some fires, some rope, and things like that, which was evidence that someone had been there. We didn't know what or who it was, so we gathered up this stuff and when we got back to Pearl Harbor after the battle, we turned it over to the Intelligence people. I never knew what happened to it or if anything ever became of the material that we had turned over. Anyhow, we had done our duty. We had gotten back and had no problem with anyone getting hurt or anything like that on this particular operation. This was all written up in a letter by William Kaufman and sent to a shipmate.

As you can see, the first landings were not made on Guadalcanal, they were made on these islands. We did learn something about handling landing craft in the surf, which we wrote up to tell them about. It was an interesting and fine experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting, the Japanese reconnaissance. Were they able to intercept radio messages and figure out which islands these guys were on?

David H. Jackson:

I don't think so. It would be of interest to know that. I don't know whether they did or not. I know most of their work, of course, was in this thing called MAGIC, which was the diplomatic traffic going back and forth. MAGIC and PURPLE were two things they were mostly working on.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's move forward again to when you were doing escort work on the PREBLE and helping the Marines land.

David H. Jackson:

That business only ran for a couple of weeks in 1943. We got all the Marines on board. We were only twenty miles or so north of Guadalcanal. There was air cover and things like that, so there was no need for us to do any patrolling. They supplied the place with these LCTs. They knew there were no Japanese on the island so they would just send the LCTs up by themselves.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your next assignment then?

David H. Jackson:

I was on the PREBLE up until June 1943. I had put in for a couple of things. Not long after Pearl Harbor happened, a dispatch came out that said, "All of the officers of the Class of '41 and '42 are to take this exam for submarines, and those who are qualified will report to the Bureau of Personnel." There were two of us. I was one of the ensigns on board. There was an Ensign Ward, from the Class of '42, who had just reported on board. We were the two who were ordered over to take our physical exams at the subbase there in Pearl Harbor. I had a terrible cold, quite terrible. I thought, “If we have to go into the tank and take the pressure test down to 150 ft., I don't think I will pass.” Because I didn't want to serve in a submarine, I didn't want to pass the test. I went over to take the exam and, lo and behold, both Ward and I passed with flying colors. I think my cold got better after I had done this. We went back to the ship and sent the dispatch out. It said, "Ensign Jackson and Ensign Ward took the exam and both are physically qualified for duty in submarines. Ensign Ward is a volunteer and Ensign Jackson is not, repeat not, a volunteer." So, of course, I didn't get ordered to submarines. Ensign Ward, very shortly after, got ordered away to submarines.

The other thing I did was put in for flight training. I took the flight physical. They sent the word, “Ensign Jackson is fully qualified for flight training and is so recommended.” In a couple of weeks back came a dispatch, “Lieutenant (j.g.) Jackson will be ordered to be the executive officer and navigator of the PREBLE in a very short time. We need executive officers and navigators on destroyers as much as we need aviators. Therefore, he will be retained on the PREBLE." This must have been in late 1942, I guess. Incidentally, I got promoted to j.g. around the first of June. It was before I was married on June 26. Then, in December 1942, I was promoted to full lieutenant, so I was going rather rapidly.

After they had retained me on the PREBLE, I put in for the post-graduate course in ordnance and gunnery. You had to put in a second choice. My second choice was engineering. In due time, before June fourth, I got my orders to report back to Annapolis to Post Graduate School in engineering. When I got to Pearl Harbor, I met a man out of the Class of 1935, a guy named “Smokey” Manning(?). Smokey had put in for engineering with his second choice as gunnery. He was off of submarines. He and I sat there and cooked up this scheme: “Why don't we go back to BuPers in Washington, DC, and tell them that we want to swap? Here is a guy in engineering who wants to go to gunnery, and here is a guy who is in gunnery who wants to go to engineering.” We flew all the way back from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco, got on a plane to Washington, went into the Bureau of Naval Personnel, and told them we wanted to swap. The captain behind the desk said, "Now look, young men, you know that you two guys were selected by the selection board. We can't unilaterally change the selection board. You will have to go to the PG School the way that you have been assigned unless you would not like to have post-graduate education." We both decided that this was no time to turn down a PG education. We went.

I went to engineering school and he went to gunnery school. It was a three-year education normally, but they put me through in a year and a quarter or something like that, so I was able to go back to the Fleet in 1944.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let me just finish up with one more question here. After you got through engineering school, where did they send you?

David H. Jackson:

They ordered me to be the assistant engineer of the USS VINCENNES, the light cruiser CL-64.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was that stationed?

David H. Jackson:

It was in the Pacific Fleet, with Halsey in the Third Fleet.

[End of Interview]