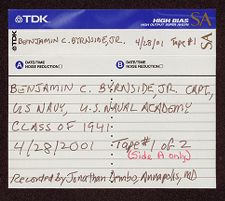

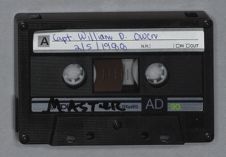

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #182 | |

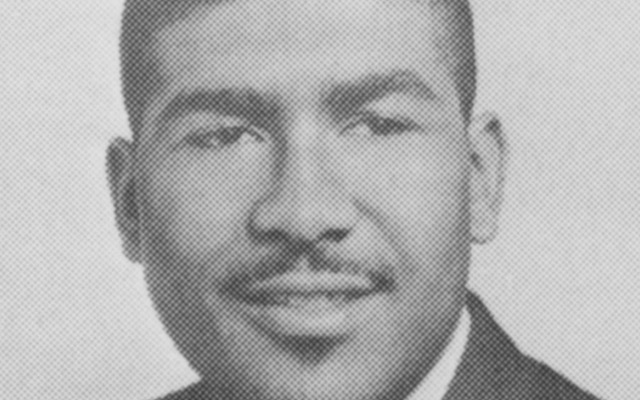

| Capt. Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr. | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 28, 2001 | |

| Interview # 1 | |

| Interview conducted by Dr. Jonathan Dembo | |

| Transcribed and edited by Christine Bendle | |

| Proofed and edited by Susan Midgette |

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, Ben, why don't we start by talking a little bit about your early life? Can you describe your family and background please?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

I was born in Oak Hill, West Virginia, on February 17, 1918. My father was a dentist. I lived in a small town. I knew everybody there, about two thousand people. I had a very pleasant, enjoyable childhood, growing into adulthood--graduating from high school there in 1935. I was quite active as far as the school went and organizations. I had no trouble making good grades because the competition wasn't too tough. I had a childhood sweetheart of course and went through all the things that you go through growing up. My mother and father were very interested in golf, which got me interested in golf. I kind of grew up with a love for the game and that influenced me later on as to where I was going to live.

After graduating from high school in 1935, I went to West Virginia University. I had an alternate appointment to the Naval Academy, but the principal was chosen so I went to West Virginia University two years. The second year I was the principal and went to the Naval Academy in 1937. I entered in the Class of 1941. I was in the group that went into the Academy the first day of plebe summer. We were the first ones to start off in the class.

I can remember Annapolis as being very hot, very humid, and very uncomfortable for somebody who had been brought up in the West Virginia mountains. But I went through plebe summer and it was all very new to me. I had not been exposed to anything that looked like Navy because West Virginia was inland. I had never had much experience with boats. I was fascinated by all of it and I really enjoyed it and made very good friends there.

My plebe year was interesting. I didn't have too much trouble with the subjects because I'd gone to West Virginia University and they used some of the same textbooks at the Academy that I already had, so chemistry and physics and math I did very well in. French was my stumbling block. I almost missed Christmas leave my plebe year because my French marks weren't very good, but I studied diligently and eventually made the grade. That was my first big hurdle in the Naval Academy.

After plebe year, we went on a Youngster Cruise, so called, which went to France, Denmark, and England. A wonderful experience. We were on a battleship and scrubbed the decks and shot the big guns and it was all new to me. We came back into New York City and back to the Academy and had September leave there. It was the first leave we had. After that I went through Youngster Year, which was not too different from what

other students do. We had a cruise to end the second-class year at the end of the Youngster Year. We had a cruise on destroyers, which went very well. We went to New York and marched on the grounds where they were going to have the New York World's Fair, but it was still under construction. And my second-class year my roommate during all this time was Frank Leighton--and his classmate--and he was a Navy junior, so I was exposed to a little more of the Navy with him.

Jonathan Dembo:

Could you explain what Navy junior means?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Navy junior is someone whose parents are in the Navy. His father was a captain and was commanding officer at Louisville.

Jonathan Dembo:

Thanks

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

But he knew all the Navy phrases, and I visited with his family some and learned quite a bit more about the Navy. It opened up an opportunity to go places that I might not have gotten to go to otherwise. I was invited to and remember going to dinner on the REINA MERCEDES, which was the station ship. It was a Spanish ship that been captured during the Spanish-American War. It was well known with the midshipmen as the REINA MERCEDES, because that was the brig in which offending midshipmen were sent if they had done something to merit a real punishment. The REINA MERCEDES is no longer there. I looked for it and it's gone. I went into first-class year. We changed battalions. I had been in the fourth battalion and went into the first battalion, which gave us different rooms in Bancroft Hall.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you explain the battalion system?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

The battalion system there at that time at the Naval Academy was divided up into four battalions and each battalion had three companies. Being in the fourth battalion, I

was in the eleventh company. Then I went to the first battalion and I was in the first company. I think they now have six battalions rather than four. But this was just a change of position and roommates. I still had Frank Leighton as a roommate, and Louis Edwards and Tom Collins were also roommates when we got back to Annapolis after our leave that first-class summer. During that first-class cruise, in which we were the first class as seniors, . . . on that cruise we could not go to our European ports because the war had started over there. They canceled that part and we just went to Guantanamo, Panama, and then New York. This time, 1940, when we marched again at the World's Fair, it was completely built. It so happened that the RKO dancers were there at the time, which made quite a few midshipmen's eyes pop out a little bit. Very pleasant, very nice.

When we got back from September leave, we found that instead of graduating in June of 1941 as we were supposed to, that we had been accelerated to graduating in February of 1941. They had to cut some of the studies and some of the classes.

Jonathan Dembo:

This was obviously because of the approach of the war. Do you recall that there were discussions amongst your classmates about the war and did you have any debates or discussions with them about the new strategies, new tactics, that were coming down the road at you?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Not to a great extent, because at that time this was a war in Europe and we weren't part of it. We were very interested of course in how the British were doing and how submarine warfare had gone. But I don't recall that there was a whole lot of instruction or discussion although everyone was extremely influenced and impressed with the German air offensive. We could see right away that the old Maginot Line, which the

French were dependent on to stop the Germans, had been bypassed by flying over the top of it. You could see that air war was going to be a major part of any future war.

Jonathan Dembo:

Well it obviously prefigures your career in the Navy as you jumped right onto the ENTERPRISE. Can you tell me about that? That must have been an amazing experience.

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

It was. Actually, I didn't select it. We didn't get to select what ships we went to, but there were four of us that went to the ENTERPRISE: Cliff Lenz, Vic Rowney, Bill Williamson, and me. I was made assistant navigator, which was a very good job. I was on the bridge a lot, plotting charts and taking star sights. I learned navigation from a very good teacher, the navigator of the ship, Cdr. Jeter. I was on the bridge and quite aware of what the maneuvers were and what was going on. Also, the flag for the carrier that we were on--the task force we were in--the admiral for that was Admiral Bill Halsey. And this, of course, was the beginning of his career so far as being an outstanding leader.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you describe some of the events that you saw with the admiral and the captain of the ship that stick in your mind?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Well, not off hand between the admiral and the captain. The captain of course ran the ship and the admiral ran the task force, so he did not get into the operation of the ship to any degree. But Captain Murray was skipper of the ENTERPRISE and he was able and very competent and treated the junior officers, not with exact friendliness, but certainly with kindness. I felt very lucky to be there and part of the operation from that viewpoint.

I can skip along to the beginning of November . . . well, we made several trips on the ENTERPRISE from San Diego to Hawaii, carrying planes and so forth. I joined the

ship in Bremerton where she was getting one of the first radars, air-search radars. Then we went to San Diego and made trips to Hawaii. One of these trips we were just carrying a whole deck load of Army Air Force fighter planes. We operated out of Hawaii for the whole summer of '41 . . . with fleet exercises, as realistic as we could make them. We found out later though that they weren't realistic enough, but more about that later. That was from February to December 7. That was my life as a bachelor, because after that it was mostly sea duty and mostly away from things. It was a very pleasant time.

On 28 November 1941, we took a Marine fighter group to Wake Island. After they flew off, we turned around and headed back to Pearl Harbor. Halsey issued Battle Order Number One, dated November 28, 1941, in which we were instructed to assume we were at war. We were loading the planes with live ammunition and the gun crews and everybody brought up the ammunition to be in a state of readiness for war. This order was signed by Captain Murray and Vice Admiral Halsey.

We steamed at high speed. The speed was tough on the destroyers because of heavy seas. We were supposed to come in and moor in Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7. But we had to slow down to speeds the destroyers could handle, so we had to change our estimated time of arrival to the afternoon or evening of December 7. As usual, we sent in some of our planes to land on Ford Island at Pearl, and, being on the bridge, I could hear some of the chatter on the radio between the pilots and ship. The pilots were screaming, “Watch out for that airplane! Don't shoot this is a U.S. plane.” We knew something was going on. Then we got the message about 8:10: "Air raid on Pearl! This is not a drill!”

We went to battle stations, I think, although we didn't know where anything was to shoot at, and there was a momentary time when people . . . just because they say it's not a drill, what does that mean? A couple of minutes of listening to this chatter and we could tell that they were actually in combat, but nothing had been said about it being Japan. I guess we figured, “Who else could it be?” We were about a hundred miles out and we sent in torpedo planes that night to search for carriers, but we were misled. Everybody thought the carriers were to the south of Oahu rather than to the north, so we just gave up on that and steamed around trying to darken ship. Our torpedo planes came back in and landed at night, carrying a torpedo, the first time any of them had ever done that, but they all got aboard safely.

We went into Pearl the next day and found, of course, all of the carnage that most people have since read about and seen: Ships being sunk to the waterline, some capsized, and some aground. Everybody gave us cheers as we went by. They were glad to see somebody that could still fight, I guess. We only stayed overnight and came back out again and searched around Hawaii for the next week or so. There were a lot of submarine contacts, but I think most of them were false.

I want to back down a little bit to the night before we went in on December eighth. On the night of the seventh, we were sending four fighter planes in to land at Ford Island. These planes had been cleared to go in, but evidently the gun crews and so forth on the ships in Pearl were so nervous by this time that they shot at our planes. I think one of them landed on Ford Island and the others were shot down. The pilot that landed said they were still shooting at him as he was landing. I think either one or two of the pilots were killed. As we started into Pearl on December eighth, the most striking

thing we saw right away as we neared the entrance was the tail section and part of the fuselage of a plane that had crashed in the water. It had the number “6” on it; it was one of our planes. It crash-landed right off the beach before you entered the harbor.

After that we came back into Pearl. I think our first operations after that were down in the Caroline Islands. This was our first offensive move of the war. We sent planes in there, which were successful. We had cruisers with us that had gone in closer and were shelling. Some high bombers came out and twin-engine bombers and we weren't very successful shooting at them. One of them crash-landed into the side of the deck and killed one man on the ship. That was the first offensive move we'd seen.

I was standing next to the executive officer of the ENTERPRISE, Cdr. Felix Stump, in the Secondary Conn, because being assistant navigator, I was also the junior officer of the deck for battle stations in Secondary Conn. This plane had dropped bombs. You could see the bomb splashes coming up about a thousand yards off the starboard side. He said to all of us standing there, "Well, as the years go by, that bomb will get closer and closer to the ship.” I think he said he was quoting Churchill or somebody who'd used that same expression during the Crimean War.

After this successful attack, we made several raids on islands in the Pacific. We raided Wake Island and Marcus Island with no counterattacks, though we did lose a couple of pilots.

We returned to Pearl in early April. We immediately refueled and were sent out on an undisclosed mission. We rendezvoused with the HORNET out past Midway somewhere. We found the HORNET had Army airplanes on deck, which we had not

expected. Of course, then the secret was out. They were trying for a launch on Japan and these were the two carriers.

We were flying air cover for the HORNET because the HORNET couldn't launch planes. Halsey was still on the ENTERPRISE. The HORNET was to launch these planes as close in as we could get, supposedly around five hundred miles, but we wanted to keep out of the range of land-based bombers if possible. Unfortunately, we ran into a . . . well there was a fishing boat that didn't look like a fishing boat--a patrol craft--and we knew they must have radioed in the fact that we'd been spotted. That little ship was sunk by a cruiser, but they made the decision that they were going to have to launch the planes. They launched the Army planes. They were Colonel Doolittle's planes--his crew--and they flew on to Japan, but of course they were a couple hundred miles farther out than they had planned to be. The raids were successful. They all got to Japan. They did beautifully on taking off in very heavy weather, a tremendous job, but many of them were lost or had to crash before they got to the place they were trying to go. This was kept secret for a long time, just where those planes had come from. Japan knew they were land-based planes but didn't know where they came from. There was even a book written a year after the war started, about the ENTERPRISE, but they didn't include anything about the Doolittle raid. They still didn't want that published.

Probably the next big operation we had was when we went down to the Coral Sea. We knew that there were Jap carriers in that area, but we had been sent from Pearl and we were going as fast as we could to get down to the Coral Sea. While we were still about twenty-four hours away, the Japanese attacked the LEXINGTON and the LEXINGTON was sunk. Most of the personnel survived. The YORKTOWN was hit by a

bomb and lost some personnel but was still operational. After that we had orders to come back to Pearl at our best speed.

We came back the end of May, 1942. Then we went out with the HORNET, and the carriers took position off Midway about 1 June.

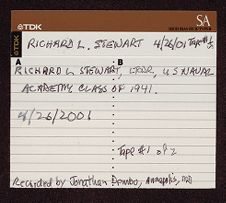

(END OF TAPE 1, SIDE A)

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, Ben, let me preface my question by saying that we left you at the end of the last tape aboard the ENTERPRISE, rendezvousing with the Fleet and approaching the battle at Midway. Can you describe your experiences during that battle?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

At this time I had been relieved as assistant navigator and was in the gunnery department. My position was the range-keeper officer on the forward director of the ENTERPRISE. We were the forward lookouts for the whole ship. Our director controlled either one or the whole group of five-inch anti-aircraft guns. We knew this was coming up. We didn't know how they had found out about the Japanese, but we were getting messages all the time. By this time we were joined by the YORKTOWN. So the HORNET, the YORKTOWN, and the ENTERPRISE were all about one hundred miles north of Midway and all searching, keeping air searches out.

We got early position reports from a patrol plane that a Japanese force was headed toward Midway. Then it became a battle to find out who was going to locate whose carriers first, because that was going to probably determine the outcome. It was June 4, 1942. The Japanese were attacking Midway Island while we were trying to find the carriers--and, of course, we eventually did. My part of the thing was manning the

director and keeping watch out over the horizon all the time to see any Japanese ships or planes. Of course, we knew we should have detected something on radar if we were within their range, but these were air-search radars and weren't very good for surface search. But I know we kept our tracker-training around because we had a high-powered optical rangefinder, part of the director that was good for searching the horizon.

I know we were surprised to see one time, far off--and the day was very clear--to see what looked like a cruiser-launched seaplane. We never could determine whether it was ours, the U.S., or whether it was Japanese. But we kept getting orders expecting attacks at anytime and of course we didn't have to wait too long. We'd launched our groups and we got planes coming in. Because the YORKTOWN was interposed between where we were and where the Japanese were, I'm afraid the YORKTOWN was the one to take the brunt of the attack. The planes, which were both torpedo planes and dive bombers, were diving into the YORKTOWN. We could see them. They were within range of, I guess, ten- to fifteen-thousand yards away. But we did not have any Japanese planes come to where we were at this time.

When our planes started coming back from their attacks . . . well, this is well recorded in history, what they did . . . they sank three of the carriers. The planes from our three ships sank three of the carriers. The planes from the YORKTOWN that were returning landed either on the ENTERPRISE or the HORNET, so we were getting them back. Of course the tragic thing was with the torpedo planes. During all of this period there was not very much wind and what wind there was, was from the northeast, so the planes and their carriers had to turn around and make very high speed to get enough wind over the deck for launching planes and landing planes. The YORKTOWN was damaged,

and we lost sight of her, because she couldn't keep up. The last we'd seen of her she was listing, not able to land planes. Of coarse the overall victory at Midway is very well recorded in history. It went on for several days. That same evening we went after the fourth carrier and sank it, our planes did, along with the remaining planes from the HORNET and the YORKTOWN.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did the men aboard the ENTERPRISE know that they'd won the battle yet or was it still unclear?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Well, as soon as reports came back from the pilots, we knew that at least two of the carriers had been either badly damaged or sunk. As time went on and they were able to see them, there was only one we knew had gotten away, and that's the one they got later that evening. We knew, I suppose, from intercepted messages and a few other things, about some of the damage. We knew that four carriers had been sunk by that night. We kept chasing the Japanese forces and they finally caught up with a MOGAMI- type cruiser and badly damaged or sank it, I've forgotten which. After that, we spent several more days searching to the westward, but their forces had retired so we went back to Pearl.

After that, the main thing was going down for the invasion of Guadalcanal. The ENTERPRISE was to provide a cover on that. We went in at Tongatapu while they were grouping and had some training for the ships that were landing troops around the Fiji islands. Then we went on over to Guadalcanal and Tulagi. This was what we would do on a usual day. We were standing watches at this time, one and three. When the war first started we stood one and two. But we found that four hours on and four hours off, when

you had to do your division duties--your sleeping and eating and so forth--left watch standers less alert than they should have been.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you explain what a standing watch one and two and a standing watch one and three mean?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Well, four hours on and four hours off is Condition Two. Then we went back to what was normal watch standing, which is one and three: In other words, four hours on and eight hours off. Except for the dog watches, and they're from four to six, and then the next watch is six to eight, and then you rotate around again. I'm just trying to say what a normal day [was like], although there was never anything normal on a carrier. Planes were landing and taking off, and crashing at different times. Planes sometimes would go out on searches and you would never hear from them again. Several planes were lost this way.

The ship's company, so far as what they were doing, was more like any other ship as far as standing watches and manning the guns. Even on the one and three watch we had the guns manned and one director. I was on the forward director for my watches. My battle station was director officer on the after director. For the watches underway, I was the computer officer on the forward director. These are the directors that operated the eight five-inch guns. It was routine, actually. People would get reports from ships and the destroyers and the task force of submarine contacts. It was hardly a day without at least one or more (either false or true) submarine or air contacts to investigate.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did the ENTERPRISE ever sink a submarine?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

No, not as a ship. Sometimes the aviators might report one, but they were kind of suspicious about whether it was a whale or something else. I'm sure they sank the one they caught on the surface.

The ships that gathered . . . we'd never seen such a flotilla of transports as well as other Navy ships that were going in for the attack on Guadalcanal. Our part of the battle at Guadalcanal was to provide air cover for the ships who were going in to transport the troops in for landings. We provided that as well as to be there to attack any Japanese ships that tried to come in and reinforce their forces there. Of course the Japanese sent in some of their big carriers along after the first week or two. This was one of our biggest battles in which the ENTERPRISE really was the target. It was, I think, August twenty-fourth in which we had an estimate of some eighty planes that came in against the ENTERPRISE. Our fighter planes took down quite a few of them but there were still a lot of planes left.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you describe what your role was when the ENTERPRISE was under attack?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Yes. I was the director officer on the after director for the five-inch guns. I was in telephone communication with the gun battery officers. We had four batteries, two forward and two aft. We could control the two after batteries on either side. When the enemy planes came in, even though we had spotted them briefly on radar at something like over one hundred miles--which was good for the fighter planes to shoot them down, of course--but we couldn't see them. Strange as it seems, they were so high we could not see those planes. They were very high and we couldn't catch them until most of them had started to dive, and there's not much time with five-inch guns to get your projectiles up fast enough to catch a plane coming down in a dive.

Now, this is when I said that some of our training had been realistic. We had had training to follow diving planes, but we'd had no practice at shooting at them. There's not any way we could have practiced at that, and we found it more difficult than we had expected. We found also that the main defense of the ship was high speed and very erratic maneuvers. The captain was a master at this. We would be going flank speed, which is the fastest you could go, and making full turns with full rudder, and the ship would be so heeled over that some of the guns couldn't come to bear on their targets. The director is high up, even with the top of the smokestack funnel from the boilers, and we would be holding on to keep from falling out of the director cockpit, still trying to control the guns and keep the director trained on planes. At this speed, smoke coming out of the boilers was coming right over top of our director, so it was very difficult to see.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was the flank speed on the ENTERPRISE?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

I never knew what they were making at that time. They were making everything they could, probably around thirty knots. But the ship was vibrating so! We'd never been at flank speed before because it used too much fuel oil. At emergency conditions with flank speed, the whole ship was shaking under us. It was like riding on a very rough road and bouncing up and down. When these planes came in, they were diving in close to the ship so that the rapid-fire guns were more successful than the five-inch guns for this type of dive bombers. Planes were crashing into the sea, and some, because of our erratic maneuvers, would get into a position where they couldn't drop their bomb on the ship so they tried to crash into the ship. They would just miss and then go over the side, hitting in the water next to the ship. I still have a certain vision of one going by that wasn't any higher than our director. I could see the pilot and he was just looking straight

ahead as he went right into the water. The noise was deafening. Everybody was doing his duty and doing what they were trained to do. It was chaotic, but orderly. The whole thing was over in less than ten minutes. We thought we'd be able to shoot our guns for fifteen or twenty minutes or something, but that wasn't the case.

We suffered severe damage, and my roommate, Bill Williamson, who was also a classmate out of Class of 1941, was killed at his gun battery. He had the starboard after gun battery. About forty-three people there were killed and he was one of them. I was on sound-powered phones with each of the battery officers, so I'd been on the phone with him. Of course, one could see what had happened, and there was no answer from his battery. It was all over so fast! We had several fires, but the ship was very good at damage control. They got things back in order. I would say that was by far the most intensive combat we had seen. An estimated thirty-six dive-bombers, nine torpedo planes, and some fighters had been in the attacking force. Out of that, we received three bomb hits.

With the damage we'd suffered, we had to go back to Pearl. We went back for repairs and to get additional small-bore ammunition. The 1.1s we had weren't good enough. We got 40-mm guns and 20-mm fast-firing guns, which were much better than the 50-caliber machine guns. They ringed the deck on both sides with these guns and they were most effective. More guns and fast firing. The Marines manned most of these guns. But we had ship's company--some of them--and some of the mess attendants had even qualified on these guns.

Anyway, we were repaired at Pearl and fixed up much better for air defense and we turned around and went back down. Again we were sort of in the middle of things,

because the battle of Guadalcanal was continuing and went on into August and September.

In October we were with the HORNET and had had reports on Japanese carriers. We finally located them. We had Japanese planes coming in, but again the ENTERPRISE was the lucky ship in some ways because the HORNET was interposed between the Japanese coming in and ourselves. They attacked the HORNET first. The HORNET was a new carrier but it was in a sinking condition [from the attacks], we knew that. The Japanese had enough planes that they made separate attacks on us. I think it was around forty to fifty planes because there were several Japanese carriers involved and this was again a coordinated attack. This time the fighters knocked down many of the torpedo planes. We had torpedo planes and torpedoes in the water, but by rapid maneuvering we had good luck and managed to miss all of them. We were never torpedoed while I was on there during the war.

This time our air defense was much better because we had experience and we had more guns and we were better fitted for finding out how to use them. The five-inch guns were effective to an extent, but again the fast-firing guns were better for the dive bombers. We were able to shoot at the torpedo planes. Also, the fast maneuvering of the ship going at flank speed, which proved effective before, was effective again. A lot of the bombs dropped just within yards of the ship but not on us. We still had, I think, three that hit the ship. One going into a repair party did a lot of damage and killed more than forty shipmates. But this time, we could keep things in conation, do a better job on defending the ship. We would keep in contact on phones with the gun batteries but, again, the ship would heel over so far that the five-inch guns couldn't stay trained on the

targets. During training, we steamed on a steady course and let planes “stream a sleeve” over us at about two thousand feet as they stayed on a straight course. We found this was quite different from when they were coming down your smokestack, practically, dropping bombs and many of them shooting at the ship's personnel.

Jonathan Dembo:

Was the HORNET within sight?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

The HORNET was within sight but by the time we were launching planes we knew she was in big trouble with clouds of black smoke. HORNET pilots were landing on the ENTERPRISE and, as I recall, we had to send DDs in to torpedo the ship ( HORNET) that evening. It was sinking, but not fast enough. They were afraid the Japanese would try and board it and there was too much classified material and so forth. That's just my dim recollection. It was sunk; we didn't see it sink just as I didn't see the YORKTOWN sink at Midway, but they were both left in a sinking condition.

During the engagement, we were able to damage the enemy carriers, but I don't recall that we actually sank one in this last engagement. The retirement done, . . . well the ship was kind of stuck back together again from the bomb damages.

Jonathan Dembo:

This was in the Santa Cruz Islands?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Well, I think it's called the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. The previous engagement was called the Battle of Stewart Islands.

After this, the damages were repaired and the ship remained in the area at the time, but we did have to have emergency repairs in Noumea, New Caledonia. We were actually in more or less a stand-by position. In so far as I know, we were the only operational carrier left in the Pacific.

There was another air battle in November in which we went after the carriers, but they didn't get any planes near us so I can't comment on that. After that, we went back in to anchor in Efate.

I had earlier put in to volunteer for submarines, and I got my orders and was detached from the “Big E” toward the end of January of 1943. I went back to New London to submarine school in March, 1943, for three months and then to the MACKEREL, a submarine that was based in New London. It was a smaller submarine but with new equipment for training prospective commanding officers. I was the engineering officer and then fleeted up to executive officer and navigator.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you explain why you wanted to leave the excitement of the ENTERPRISE for submarines?

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

I had put in for submarines quite a bit before the excitement, but hadn't been transferred. I had some good friends in Pearl Harbor that I'd known on liberties, and there were a couple of families there who'd kind of taken me under their wing and had me for dinner and so forth. These were submarine people and they'd all been real nice. I liked all of them. They all urged me to put in for submarines. I had been aboard and looked at them and so forth.

In submarines you had more responsible positions at a younger age, because you only had six to eight officers and you were a department head. I'd been promoted rapidly and was a lieutenant. I have a technology interest and I was fascinated with all of the systems of running a submarine and diving and surfacing and the electrical systems and the fact that it was so potent with torpedoes. It was attractive to me and I liked the people

so well that I knew I wanted to be a part of it. I started in submarines fairly senior. A lot of ensigns were being turned out and were coming to sub school.

While in New London, I met my wife-to-be, Barbara Pfohl, and was married. She was at Connecticut College, which is across the river at the sub base at New London. Quite a few submarine officers married Connecticut College graduates. We were married in January of forty-four.

Jonathan Dembo:

I think this is a good place to end because we are going to run to the end of this tape and we're about ready to run into my next interview.

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

Oh, I'm sorry.

Jonathan Dembo:

No, no it's not your problem. This is great. We are going to have to continue this though. Maybe I can make a trip to your place.

Benjamin C. Byrnside, Jr.:

I can send you a tape.

Jonathan Dembo:

Oh no, well, that would be nice too. You could pick it up from where you left off here.

[End of Interview]