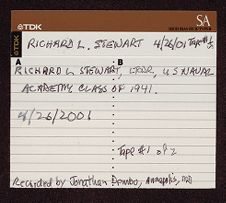

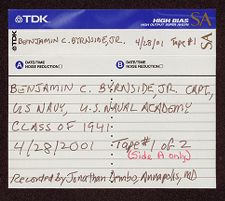

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #188 | |

| Richard L. Stewart | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 26, 2001 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Dr. Jonathan Dembo | |

| Transcribed and edited by William J. Dewan | |

| Edited and proofed by Susan R. Midgette and Martha G. Elmore |

Jonathan Dembo:

If you would tell us a little about your background, your family, your heritage, your early education.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I did have some early education. I was born in Memphis, Tennessee. My father was active in politics. And my grandfather had been Squire Stewart, he was called, which was a term for county supervisor. My father was County Register of Deeds, which was, fortunately at that time, a fee-paying job. So, he was quite lucrative for a while until he became ill. He died when I was a senior in high school. Virtually broke after having lived well for a number of years.

Growing up in Memphis was not all that difficult. We did have, I had my chores, I had to carry coal to the upstairs fireplace, the upstairs sitting room. Now, we had a black man who came around and stoked the furnace. (Laughs.) And we always had a cook in the kitchen and when my brother and I were really small we had a nurse. So we

were well provided for that way. It was a comfortable life until my father became ill and died. And then things sort of toughened up.

I went to Central High School in Memphis, graduating in thirty-six. At that time we sent 96 percent of our graduates to college, which was pretty damn unusual for a public high school. There were other public high schools in town, but if you belonged to the right family and had good grades, you went to Central High School. Which was good. We had two graduates in my class at the Naval Academy. And at least one on a full scholarship to Princeton. I had a scholarship from what is now Rhodes College, the first year. So I went there, with the aid of two part-time jobs, I managed to get through a full year.

Jonathan Dembo:

What type of jobs did you do?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I worked in the office for a while, on the telephone switchboard. And I had the strangest paper route you ever saw. It was all in one apartment hotel. I'd go to my last lab in college, go pick up the papers, ride the elevator upstairs to the eleventh floor, deliver them on the way down to each appropriate apartment, and at the end of the month go down to the desk and pick up the check from everybody. (Laughs.) Which was pretty damn nice!

Jonathan Dembo:

What kind of interest did you have around this time in sports, for example, or cultural activities?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I didn't need no culture! (Laughs.) Uh, sports, mmm, not really. Never been particularly active in sports. I was reasonably healthy. I was able to walk and ride my bicycle, and do all sorts of nefarious activities that kids do.

Jonathan Dembo:

When did you first become interested in, or thought you might want to go to Annapolis?

Richard W. Stewart:

When I was twelve years old, we drove from Memphis to Washington. I and my brother, seated in the back seat--the rumble seat--of a Ford Model A, with an awning over the top, fortunately, because it was in the summer and very hot. We went up and saw Washington, and dad had to go to a reception for our local Congressman and so on. And we went over to Annapolis one day. And I said, “Hey, that's for me!” And ultimately it was.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you have any difficulty getting in to Annapolis? How did you go about doing that?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I had been to college for a year, at a small liberal arts college now known as Rhodes College. Then it was called Southwestern at Memphis. So I can tell people I was a Rhodes Scholar. (Laughs.) Which wasn't true then, Dr. Rhodes was the head of the Philosophy Department at that time. And my grades were such that I was accepted into the Naval Academy without any exam. So I was a moderately good student.

Jonathan Dembo:

Explain your first impressions of Annapolis, when you first arrived, what was it like?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, certainly wasn't like it is now! (Laughs.) It's changed quite a bit. Now for a twelve year old, I was quite impressed with it. And now I have my thirteen-year-old grandson here today. And I will expose him to the same thing. All of his background is such that . . . my older daughter, I'm afraid, I've failed. I tried to educate her properly and she married an Air Force officer. What an awful thing to do. (Laughs.) A

wonderful young man, I love him dearly, but . . . the Air Force. Not only that but he was in an oxymoronic activity called Air Force intelligence. You know there's no such thing.

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, it won't leave this room. When you first arrived at Annapolis as a Plebe, when was that and how did you get here?

Richard W. Stewart:

I took the train up, stayed at this inn, Carvel Hall, a very nice hotel that is now gone unfortunately. And of course I had a preliminary physical at home. I took another one that first day at the Naval Academy, and failed. Which was not surprising.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was the matter?

Richard W. Stewart:

I was just too upset with the change. My blood pressure was high. And my doctor understood, he said “Go back and get a good night's sleep, and see me first thing tomorrow morning.” And I did, and it was perfectly normal. (Laughs.) And remained so for the next, roughly fifty years. But he understood.

Jonathan Dembo:

What do you remember most about Annapolis?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, it was academically not too difficult. For example, at Rhodes College I had a 98 in mathematics. I took the same course over again at the Naval Academy, and came up with the equivalent of about 75! (Laughs.) Just different competition. The competition was pretty stiff there. I don't know what the situation is now, probably still is. I had to work a little harder to get the same grade. Except in one subject only, and that was languages. I'd had a pretty good background in Spanish in high school and college before; so I ultimately graduated, I think, with a three or four in languages for the four years. That was maybe a natural talent or because I had a good background before I came here. I could not beat Ramon Perez in Spanish because he was a native of Puerto

Rico. Pierre Charbonnet did quite well in French. It was the one subject in which I was. . . .

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you make any particular friends while you were at the Academy?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yes, I had friends, roommates, and so on. One of them I just met down in the lobby, he's just checking in.

Jonathan Dembo:

Who was that?

Richard W. Stewart:

Jim Lynch. One of my roommates was killed in the Philippines. I happened to be in the same operation. He had an interesting position on a battleship. He was an air defense officer. And the air defense officer on a battleship at that time sat in the highest part of the ship, protected by a steel helmet. Which was not effective against kamikazes at all.

Jonathan Dembo:

So this would have been in 1944?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah.

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, during your time in Annapolis, you must have been aware of the onset of World War II in 1939 in Europe. And even earlier in China and the Pacific with the Japanese.

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, we were. We had one of our cruises changed. We could not go to Europe because the war was going on there, so we went to Central America instead.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did this have any effect on your thinking? Do you think that any of your professors or instructors were drawing lessons from the events and incorporating that into anything you were being taught?

Richard W. Stewart:

I did not recall any evidence of that. We all knew that we were graduating early because we would soon be in a war. So on graduation we went our various ways. I was sent to a destroyer, which happened to be at Pearl Harbor.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was the name of the destroyer?

Richard W. Stewart:

USS DOWNES.

Jonathan Dembo:

When was that?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I went in the spring, I guess it was about March before I got there. And it was at sea, so I stayed on another destroyer for a month until the DOWNES came back into port, then went aboard.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was your first assignment on the DOWNES?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, actually at that time the Navy was building up, and we had, I think, seven officers on the destroyer then, where before they'd only had five. I was junior man, I was assigned as an assistant engineer officer. Which was fine with me.

Jonathan Dembo:

What did an assistant engineer officer do?

Richard W. Stewart:

Anything the engineer officer tells him to do. (Laughs.)

Jonathan Dembo:

Give me a brief list please.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, when I was later on chief engineer of the destroyer I had two assistants; one of whom I put in charge of the boilers, and the other was the electrical officer. At that time, we had a limited number of officers and a fairly small number of personnel. We were just beginning the buildup. So we operated out of Pearl for a while and, fortunately, I was able to get some leave. The ship was headed back to San Francisco, and I was granted a couple of weeks leave, so I went home. I had a watch that had belonged to my father, and I gave it to my brother. I said, “Here, keep it. I don't want to lose it when the

war starts.” He said, “Oh, you're crazy, you're not gonna be in no war.” I said, “Okay, but you keep it.” That's the only thing I owned that I owned before the war. And just two days ago I gave it to my grandson.

Jonathan Dembo:

Great.

Richard W. Stewart:

We knew the war was coming. Just not when it would happen.

Jonathan Dembo:

Tell me a little bit about the equipment that you had to deal with on the destroyer. What type of engines did you have?

Richard W. Stewart:

They were steam turbine. We had a fairly new destroyer; it was built in 1937 [1936]. A MAHAN-class, and they started building newer ones at that time in forty-one. This was one of the latest ones in the fleet.

Jonathan Dembo:

And what was its particular role to play in a battle? What was it designed to do?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, they were screening carriers and things like that. And we were equipped with five-inch thirty-eight guns and torpedoes. And a few machine guns. We were actually in dry dock when the war started. Have you ever heard of shooting fish in a rain barrel?

Jonathan Dembo:

Yes, I have.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, that was it. They could have sent us a post card on Thursday, and it wouldn't have made any difference. Because our propellers were sitting on the side of the dock, the boilers were open.

Jonathan Dembo:

Was the DOWNES attacked at Pearl Harbor?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well we were in dry dock, two destroyers and the battleship PENNSYLVANIA. They did not come for us in the first wave, cause they knew we weren't going anywhere. They came over to attack the PENNSYLVANIA and bombing is so ineffective that they

missed and overshot the PENNSYLVANIA and destroyed the two destroyers. And they both burned in dry dock. Of course that was God-awful, not everyone was aboard. People were ashore for the weekend. I should have been, but I had car trouble the day before, and I decided, “Oh, the heck with it,” and stayed aboard.

Jonathan Dembo:

So how did you first know there was an attack going on?

Richard W. Stewart:

The noise, the bombs.

Jonathan Dembo:

What did you do? What was your role?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, there was obviously no point in my going to the engine room. We weren't going anywhere. I took over at the machine gun and we did get some shots off. Hopefully, shot at a plane or so, until the ship burned and I had to leave. And that's why I got the medal.

Jonathan Dembo:

What medal is that?

Richard W. Stewart:

Oh, it's the Navy Commendation Medal. In jumping off the burning platform I had broken some bones in my foot. So, I got over on the side. I did get off the gang rail before it burned, fortunately. There was no water under us, of course.

Jonathan Dembo:

How far down did you have to jump?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, just one deck.

Jonathan Dembo:

So you must have had some time to look around you.

Richard W. Stewart:

Not very damn much. When a ship burns, it burns like mad.

Jonathan Dembo:

After you got ashore, to look around the harbor and see what was happening. . . .

Richard W. Stewart:

Actually, I did watch the SHAW in the neighboring floating dry dock get blown apart. And it was pretty horrendous. A Japanese plane came over strafing.

Jonathan Dembo:

How many times did they come over? I mean, about how many times?

Richard W. Stewart:

A couple of times. Actually, one interesting thing that a lot of people down home like to make a point of . . . of course, I couldn't move very fast then, but they were putting this culvert in place, and the chief petty officer that outweighed me by quite a bit--I was about 160 pounds then, wish I were now--we both made a dive for this culvert. There was only room for one of us, but damned if we both didn't get in there! That lasted about a minute until the plane had left and I went back, crawled out. And for the first time in my life, I stole a car. Saw a car that had the keys left in it. So I spent the rest of the morning taking people to the hospital. Then around noon. . . .

Jonathan Dembo:

Even with your foot broken?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, it was my left foot. And I could shift the clutch with my left heel. It wasn't much fun, but I mean, it worked, I could do it.

Jonathan Dembo:

So at the end of the attack on Pearl Harbor, you were left without a ship. What happened then?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I was in the hospital for a while, which is not a very happy place to be. In fact that night, lying in the hospital, we had some planes coming over and some of the ships in the harbor opened up on the planes. And me on the third deck in the hospital with a foot, by that time with a cast, hardly maneuverable. That was not a happy place to be. So I stayed in the hospital for a while.

Oh, I wanted to tell you, and this I did not put in my written accounts. Everybody on the ship did very well, we did lose 12 men out of a total crew of around 130 at that time, but not everyone was aboard. But we had one . . . do you know we were segregated then? The steward's department was either Filipino or black. And we had one black mess attendant, did his job fine until the ship burned. He managed to get off the ship

safely. And nobody saw him until the next day. Of course, I wasn't there, but the others tell me, they said, “Scales, where've you been?” And he said, “Well, sir, when the ship burned I got off and I took out to run and I ran until I ran out of land.” He said, “If this hadn't been an island I'd be running yet.” And that was the most sensible approach to the situation of anyone I know. He just ran until he ran out of land.

Jonathan Dembo:

You must have ultimately been reassigned to a new ship.

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, I went back, I put a new destroyer into commission.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was its name?

Richard W. Stewart:

SIGOURNEY.

Jonathan Dembo:

And where was that?

Richard W. Stewart:

It was being built in Bath, Maine. So I went to Bath. You see the engineer was the first one assigned usually.

Jonathan Dembo:

So you were now not an assistant engineer, but a chief engineer.

Richard W. Stewart:

Right. Of course, I had been promoted meanwhile. And I had two junior engineers and ninety-six men in the engineering department. They had really built up the Navy quite a bit.

Jonathan Dembo:

What kind of engines and machinery did you have to deal with there? Same sort of situation?

Richard W. Stewart:

On a larger scale. There was a 60,000-horsepower plan.

Jonathan Dembo:

So the SIGOURNEY was bigger than the DOWNES?

Richard W. Stewart:

Oh yes, it was FLETCHER-class ship. And I took it out to the Pacific.

Jonathan Dembo:

How does a FLETCHER-class ship differ from the DOWNES-class ship?

Richard W. Stewart:

It was larger. It was probably just about as fast. And it had more power. More modern armament.

Jonathan Dembo:

What kind of armament?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, it still had the five-inch thirty-eight guns, but we also had some forty-millimeter guns, which were not available at that time, rather than fifty-caliber machine guns.

Jonathan Dembo:

And was its role in a battle any different than the DOWNES? Did it have a different function, or was it bigger and faster?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, the functions changed over the years to a degree. An awful lot of their work was done in shore bombardment. As a matter of fact, the five-inch gun barrel was supposed to be replaced after about five hundred rounds. On the SIGOURNEY we had fired twenty-five hundred rounds per gun before the ship came back. And the shells were not really going out end over end like we wanted. Anyway, we did have some interesting experiences on that ship. I will never forget the first day we pulled into Tulagi in the Solomons.

Jonathan Dembo:

When would this have been?

Richard W. Stewart:

In, toward the end of forty-three, I guess. And I can't remember the dates.

Jonathan Dembo:

Was the battle at Guadalcanal still going on?

Richard W. Stewart:

Oh yes. In fact, we came in and Guadalcanal was all lighted up like a Christmas tree.

Jonathan Dembo:

Okay, so it would have been the summer of forty-two.

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah. Anyway, it was a busy time. And a Japanese plane would come over and they'd turn out all the lights, and when the plane left they'd be back on again, offloading.

We took our ship into Tulagi, which is right across Iron Bottom Bay, and there were three other FLETCHER-class destroyers, two of them with the bow shot off and one with the stern shot off. That was not reassuring at all. As you can imagine. And with other destroyers, we were running up and down the “slot” doing our bombardments and so on.

There was another young officer in that area that you may have heard of who had the fastest ship in the Navy--a PT boat. The damn fool was asleep at the switch and let it get run down by a slower ship. You may have heard the guy's name. John Kennedy.

Jonathan Dembo:

John Kennedy. Did you ever meet him?

Richard W. Stewart:

I did not meet him.

Jonathan Dembo:

You just know his reputation?

Richard W. Stewart:

I know his reputation. I know that if his father hadn't been an ambassador he would have been court-martialed for negligence. And they tried to make a hero out of the guy. And I think that's disgusting. But that's my opinion, I think a lot of people share it, but I don't know.

Jonathan Dembo:

We want you to express your strong opinions. And were you ever in action, was the SIGOURNEY ever in action on these trips up and down the “slot?”

Richard W. Stewart:

Yes, we were under air attack a number of times. In fact, one time we were escorting slower small transports up toward Bougainville, when a Japanese torpedo plane came over and one of the transports was hit. Our captain, whose name was Dyer, Walter Dyer, stopped alongside, well, at a fair distance from the burning ship. He put cargo nets over the side. One of my assistants was on deck as damage control officer. He helped some of them climb up. We did save a lot, a fair number of survivors from this ship. I think the name was McKEAN. And another torpedo plane came heading out our way. I

was in the engine room, of course, which was my battle station then. The Captain rang up flank speed ahead, about three times, and he threw everything but the wardroom furniture at the boilers. In sixty seconds we were making turns at twenty knots or more. Of course, we weren't doing it through the water, but sort of stood on end and made a big circle around, came back, and stopped in the same place, and kept looking for survivors. Meanwhile, my assistant, who was on deck, said he could have spit on the torpedo as it went past the fantail. That was a busy morning. But I had busy mornings.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you ever, did the SIGOURNEY ever have any opportunity to fire at surface ships?

Richard W. Stewart:

Ah, later. But that was out in the Philippines. We did sink a destroyer in the Battle of Surigao Strait.

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, hopefully we'll get to that. How long were you in the Solomons?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, until it was pretty well finished. We actually went up to the northern Solomons, the landing on Bougainville. We used to go down to Treasury Island--and I'm not sure how familiar you are with the geography, but you're not supposed to be--but that was a small island, just south of Bougainville, where we would go for fuel and ammunition. Between us, on the southern tip of Bougainville, there was a Japanese airbase. Not too many, but there were Japanese planes. So we would be at Treasury taking on fuel on one side and ammunition on the other, which was strictly illegal to do. Too dangerous. And every once in a while a Japanese plane would come over, which was disconcerting.

Jonathan Dembo:

I'd imagine.

Richard W. Stewart:

But one of my favorite experiences on Treasury Island was . . . the troops holding Treasury were New Zealanders. We were there one time doing the same thing, for fuel and ammunition, and this little “spitkidder” (?) of a sailboat, about fourteen-feet long, came up alongside. And a New Zealander down below says, “I say there, can anyone tell me where the yacht races are today?” Actually, we broke up, believe me.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you ever get a chance to meet or socialize with the New Zealanders?

Richard W. Stewart:

Very little. Later on we worked with the Australian ships in the Philippines. And we did. Now a big problem with the New Zealanders is that as we went along to the Philippines, we were fed a lot of so-called New Zealand lamb. And New Zealand lamb, man it took two husky sailors to carry one aboard. I think it was New Zealand mountain goat they were passing off on us.

Jonathan Dembo:

Mutton.

Richard W. Stewart:

And I couldn't eat mutton for years after that.

Jonathan Dembo:

It's real fatty.

Richard W. Stewart:

Anyway, we did eat well on the ship. In fact, on that particular ship, our captain liked his ice cream. So while the ship was being put in commission in Boston, I managed to liberate an ice cream maker from the supply system. So every time the captain made his inspections of the lower decks on Friday, I had a man standing by the ice cream machine with ice cream for him.

Jonathan Dembo:

A politician.

Richard W. Stewart:

But then, we were up in the Solomons. At that time, in Bougainville, we were doing close shore bombardment, with fire support Marines aboard. And talk about close, we were in water range of the Japanese. By this time I had been advanced to second

navigator, 'cause the former exec got his own command. No, I hadn't been, I was still chief engineer at this time. We went aground within mortar range of the Japanese, which was not a happy situation to be in. So I put on my shallow diving suit and went overboard to see what the damage was. Sure enough . . . it wasn't the navigator's fault, we were using charts made in the 1850s by a German ship. Anyway, he was not held responsible for it. But, I saw the propeller had been damaged. Fortunately there were some tugs over at the main landing that came along and pulled us off. We were not particularly hurt, but we couldn't move very fast with one propeller damaged. We had a lot of vibration. So we had to wander all the way down to Espiritu Santo in New Hebrides and go into dry dock to get a new wheel on, which we did. That was interesting. Did you ever see South Pacific?

Jonathan Dembo:

Yes.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, this was very reminiscent of that. The island of New Hebrides in the South Pacific. We had a nice Officers Club up there, and we knew we were going to be in dry dock for a while. I can remember that several of us went up to the Officers Club for entertainment one evening and it was time to head back to the ship, so we found a jeep that could run. There were a couple of nurses that happened to be at the Officers Club . . . we started down the hill. About halfway down, I was not driving, but we turned the jeep over. Fortunately, no one was hurt. Everybody got off, we righted the jeep, pushed it back up to the road, drove down to the dock and abandoned it. Went back to the ship. I always said I'd rather be lucky than smart. So we were lucky.

Jonathan Dembo:

Back in the Solomons, were you operating alone or in a group?

Richard W. Stewart:

Almost always in a group. You've heard of Arleigh Burke, who had the destroyer squadron there?

Jonathan Dembo:

Mmm-hmm.

Richard W. Stewart:

They called him “31-Knot” Burke. You know why? His ships had been out of dry dock too long and “barnacled,” and 31 knots was all he could do! But anyway, wherever Arleigh Burke and his destroyer squadron went, we went. Next, like through a bowl. Uh, we went up, this was after I became navigator.

Jonathan Dembo:

When did you become navigator?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, not too long after we got out of New Hebrides and came back to the Solomons. The captain called me up to the bridge one night and said, “Dick, we're getting in in the morning. As of tomorrow, Mr. Ruder is leaving, he had his own command, you're the executive navigator. I'd been chief engineer. Damned if I wasn't! But fortunately, because at that time there were only three regular Navy officers aboard, the rest of them had been made up of Reserves. And they did a wonderful job. But I was the only one who had some engineering background and qualified officer of the deck. So I stood watch as the top watch on deck. So changing over to the executive navigator wasn't that traumatic for me. I was supposedly educated in both areas.

Jonathan Dembo:

Besides, obviously, navigating, what other main responsibilities were there for a second navigator on a destroyer?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, actually they've changed over the years, but at that time the executive, of course, was the second in command.

Jonathan Dembo:

So you were the executive officer of the destroyer as well as being the navigator?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah. I think that has probably been reassigned. I was second in command, and I was the official bad guy. The captain can be a great fellow if the exec has to do all the dirty work and discipline everybody. That's all right, that's part of the job. And years later after the war, the ship had a reunion and I was a little curious about what the feeling would be about “the official S.O.B. on the ship” coming back to the reunion. I got a wonderful reception. And we're having another reunion this fall in Myrtle Beach.

Jonathan Dembo:

Do you go to, or have you been to reunions of all of the ships that you've served on?

Richard W. Stewart:

No.

Jonathan Dembo:

Just a few.

Richard W. Stewart:

We've never had a reunion with the DOWNES. Of course, it was pretty well destroyed. Except politically. The ship was a wreck. They towed it--they patched up the hull and they towed it back to Mare Island. And in order to avoid saying another ship was lost at Pearl Harbor they took the engines out and put them in a new hull and called it the same name. But it wasn't the same ship by any means. But publicity-wise it was worthwhile, I guess. But that's the way things go.

Jonathan Dembo:

So where was the ship when you were appointed to be navigator?

Richard W. Stewart:

On the way back to Tulagi.

Jonathan Dembo:

So just after getting out of dry dock and on the way back to Tulagi.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, actually I think we may have been on another operation since then. But I was navigator when we went to Rabaul, and that's quite a way up into New Guinea. We were pretty much flank speed all the way up with the enemy held territory on both sides. Stopped off at Rabaul, did our shore bombardment for a while, and then turned around

and got the hell out of there. Which was a smart thing to do. And we had no problems. It was an exciting evening, lasted all night in fact.

Jonathan Dembo:

So after the Solomons were secured, where did you go?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, we went to the Marshalls and the Gilberts.

Jonathan Dembo:

Basically doing shore bombardment?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, with a task force. Once in a while we would work with a carrier group but mostly for shore bombardments.

Jonathan Dembo:

So eventually you ended up in the Philippines.

Richard W. Stewart:

Oh yes, not only that, I was navigator of the ship that led the bombardment group into the Philippines the day before the landing.

Jonathan Dembo:

This was at Leyte?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, Leyte.

Jonathan Dembo:

What happened then?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I had three battleships leaning over my shoulder while I led them in, and all I had to do was lead them aground and my name would have been mud from then on. Well, they shot up the beach most of the rest of the day. That night they left and my destroyer and one other were the only American ships in the Philippines overnight. And that was lonesome.

One thing I forgot to say about Pearl Harbor. On Saturday, you know officers' uniforms were tailor-made. And I had a tailor back in Norfolk, Virginia, who made my uniforms. The Navy had just authorized khakis for officers. There were none off the shelf, so I wrote back to my tailor in Norfolk and he made me four suits of khakis, which

were delivered by the mail clerk on Saturday. And I looked in the box and saw that all my khakis had come, and that's where they burned up the next morning. (Laughs.)

Jonathan Dembo:

You had to reorder everything.

Richard W. Stewart:

It was an expensive operation. At that time an officer never left the ship in uniform except on official business. So we had to have a pretty complete outfit of civilian clothing aboard. We had other things like the radio and a typewriter and what have you that was not required. So we were never paid for losing all that. It was an expensive operation for us. We were allowed to collect for the uniforms we were required to have, and what we were required to have we couldn't live on aboard the ship, particularly a small ship like that which didn't have a laundry room. And we wore whites. So I had fourteen white uniforms. I think the allowance called for about four, which I got paid for. So it was an expensive operation. But there was magnificent pay--you know I think I got $125 a month plus the $17 ration allowance. Times have changed.

Jonathan Dembo:

So let's jump back to Leyte, when the excitement begins.

Richard W. Stewart:

That was a busy morning, too. I said the three battleships did their shore bombardment. They left, very sensibly, and my destroyer and one other were the only American ships in the Philippines overnight. We did various bombardment groups around the end of Leyte once and sank a small Japanese freighter. About that time the first kamikazes started up.

The Battle of Surigao Strait was a major event for the Navy. You probably read about that. My ship was screening the Battle Line and I got to watch everything on the radar. And as you know, the torpedo boats missed down at the southern end. Some of the destroyers did make a torpedo run; one of them was hurt, and lost, I think, but not

much. Then our group of destroyers--and by that time most of the damage to the Japanese had been done--was released to go down and do our cleanups. Though we did sink a Japanese destroyer with gunfire. And that was the only major surface encounter we were in. There was hardly another major [bigger] surface encounter in the world, and that had been the first “crossing of the t” at the Battle of Jutland [WWI]. So, it was, again, a very busy evening. Again, I did the important thing for me, I survived.

Jonathan Dembo:

Were there any injuries onboard?

Richard W. Stewart:

Actually, the whole war, we had only one man slightly injured on the SIGOURNEY. And that was after thirteen invasions.

Jonathan Dembo:

So where did you go after Leyte?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, we still had a lot to do in the Philippines, in the northern Philippines. We went up through several islands that we landed on there. We went into Subic Bay, and for a while we worked with a couple of Australian cruisers and some American destroyers. They were good people to work with. I can remember, Manila was pretty well taken by land and we were chosen to take a liberty party from this little group of Australian and American ships into Manila, for sightseeing. We were steaming past Corregidor, and that was on the day that the decision had been made to take Corregidor back. So I was on deck and we had all these people in whites ready for liberty, and I got on the announcing system and said, “Now on our left we have an amphibious operation in progress, paratroops landing, the boats landing.” A full-scale occupation on Corregidor, and here we had a liberty party on board. We pulled into Manila, and there was no place to tie up. I had to get out in the harbor, because the harbor was pretty much a mess.

There was an American hospital ship in there to take American released prisoners of war back.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you get to meet any of them?

Richard W. Stewart:

I didn't meet them; I had an hour or so ashore to walk around a bit. But you didn't want to bother them in a situation like that, cause they were taking a full load of pretty bad-off people--taking them home. So that was my first visit to the Philippines. I've been back several times since then. That was my first visit to Manila.

Jonathan Dembo:

So this must have been early 1945.

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, and then we went up into the Northern Philippines. We took part in the landing up in Lingayen Gulf. I was still on the destroyer; we were escorting troops.

[End of Tape 1]Jonathan Dembo:

Last on board the SIGOURNEY, escorting a convoy of troop ships from Manila to the Lingayen Gulf, what happened then?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, we did have a fighter director team on board. In fact, for a while we had an officer who'd learned--he was a Marine--learned the art in England. And, we did have air cover, supposedly. If they were Navy or Marine air cover, they were very good and well ordered and would do what they were told, and were successful. If they had Army Air Corps cover, the pilots were just as competent, I'm sure, as the Navy and Marines were, cause they had pretty much the same training; however, they seemed almost totally lacking in discipline. They seemed to think they were there to shoot down Japanese planes, which was not their primary mission. They were there to protect the convoy. If a

Japanese plane came over, they would follow him a hundred miles away trying to shoot him down, which was not what they were getting paid to do. Meanwhile, they would be perfectly happy to leave the convoy unprotected for anybody else. So I was thoroughly disgusted with the lack of discipline of the Army Air Corps pilots. And I still recommend that the Air Force be disestablished; I think we have no need for it. But that really turned me off on the Army Air Corps.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did the lack of discipline ever lead to an attack on the ship?

Richard W. Stewart:

I think one time we were left uncovered. So I'm very much against a separate air corps. The Army Air Force is great on public relations and damn poor at fighting a war. They will not support ground troops. It's a mistake to have a separate Air Force, in my opinion, and I think a lot of people would agree with that.

Anyway, we got to Lingayen Gulf and again it was a fairly hectic operation. We did our shore bombardment. One of my roommates from the Naval Academy was an air defense officer on a battleship. He was killed by a kamikaze.

Jonathan Dembo:

Was that frequent at this time?

Richard W. Stewart:

Kamikazes were getting bad. When we were back at Leyte Gulf, for example, there were times we would have destroyers at the entrance to the gulf with the other ships inside fueling and what have you. One time we were on patrol at the entrance. Kamikazes came in and hit the battleship that one of my roommates was on. He was turret officer of number one turret, but fortunately he was officer of the deck at the time, and he wasn't hurt. The ship had to be sent back for repair.

Anyway, once while that was going on our time came to go in and fuel. We were relieved on station by another destroyer. It was fairly quiet when we were in the gulf

getting fuel, but the destroyer that relieved us was hit. So again, I say it's better to be lucky than anything else--being at the right place at the right time. Incidentally, I seem to have skipped over some fairly important landings.

Jonathan Dembo:

We've got plenty of tape.

Richard W. Stewart:

The Marshalls and the Gilberts. They were important operations in which we participated, but nothing too dramatic to report. We participated at the landing at Palau, which again was horrendous ashore but not so bad at sea. Saipan was a little different story. We spent sixty days going around and around Saipan doing shore bombardment. At one time we had close fire support, not too close. We were doing our shore-fire support and a Japanese torpedo plane came in and launched this torpedo at us. Fortunately, he dropped it too close. And I say fortunate because when a torpedo plane drops the torpedo, it goes down into the water and then has to level off to its proper level. I was on the bridge at the time, by the sonar gear. This particular torpedo went right under the ship. I could hear the sound of its propellers. And before it leveled off, it went over and hit the beach. It just went right under the ship. Have you ever tried to dig a foxhole in a steel deck? (Laughs.) It doesn't work. But you feel like it anyway.

Jonathan Dembo:

Still lucky.

Richard W. Stewart:

We spent two full months going around and around Saipan and Tinian. Sixty-two days I think without touching land.

Jonathan Dembo:

Refueling at sea?

Richard W. Stewart:

Oh, yes. And doing an awful lot of shell bombardment work. And it was very important that we take those islands back, because Tinian was where the atomic bomb was left from. Other than that, as far as being hazardous to us, there was only the

occasional enemy plane. I was navigator, and we left the Philippines coming back to Palau, roughly nine hundred miles, a thousand miles. And I was navigator, and I had to give them my expected time of arrival. I missed it by four minutes, which I thought was pretty good. But we would anchor in what was called Kossol Passage, which was a string of islands north of the main islands in Palau, all of which were held by the Japanese. Many ships would stop and anchor there. We'd show movies on deck, maybe surrounded by Japanese, but they were harmless by then. They had no way of getting at us, and we just left them alone. Why not?

Jonathan Dembo:

Who was the captain? Do you remember?

Richard W. Stewart:

Of our ship? By that time, Captain Dyer had left. One thing I wanted to do when we made that trip to Ormoc--we went through a pretty narrow strait--and I recommended that that strait be named “Dyer Straits.” But I couldn't get the political. . . . Captain Dyer got his division command--made four stripes and got his division command. Commander Fletcher Hale relieved him. And he was with the ship for the rest of the war.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was his first name?

Richard W. Stewart:

Fletcher Hale. And it was a FLETCHER-class destroyer. Some people used to say KIDD-class destroyer, but there was no KIDD-class destroyer. Admiral Kidd was a fine man, he was killed in Pearl Harbor, but there was no destroyer class called the KIDD class. The FLETCHER class was an important class during most of World War II. On the one I had command of later on, it was the BRISTOL-BENHAM class.

Jonathan Dembo:

Speaking of, when did you get command of the destroyer?

Richard W. Stewart:

After we came back from the war. I was assigned as executive officer of the new twenty-two-hundred-class destroyer. I was there, and the war in Europe was over. The

war in Japan was winding down. I was sent off to a couple of schools, I even spent a couple weeks in heaven. Have you been to “Heaven by the Sea”? This little island in New Jersey, where Father Divine had a hotel . . . and the Navy had taken it over as a radar station. It was right on the beach and about twelve stories high. So I spent two weeks there with some refreshing radar training. So I spent my two weeks in heaven, and then I went down to the command class at anti-submarine warfare school in Key West, where I by then was lieutenant commander. I was junior man in the class. I stayed in a nice hotel, enjoyed the officers' club. We were there on V-J Day.

Jonathan Dembo:

Where was this again?

Richard W. Stewart:

At Key West. And I stayed with that ship.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was the name of that ship?

Richard W. Stewart:

BROWNSON. It was a larger ship. I stayed with it through the shakedown, and then I got my orders as commanding officer of a smaller ship, which had been built as a destroyer and then converted to a high-speed mine sweeper. So I had a destroyer command at the ripe old age of twenty-six, which was not unusual for my classmates. Nowadays, unheard of.

Jonathan Dembo:

What type of destroyer was it?

Richard W. Stewart:

I think it was called a BRISTOL-BENHAM . . . I'd have to look that up. It was a lighter and faster ship. It had been converted for minesweeping. And it was never used, it never swept a mine. We did tow targets, because it had the tremendous reel cable on the back, two thousand yards of one-inch plied steel cable. We could tow a target at a pretty high speed, let the battleships and cruisers shoot at it. At it, we hoped they shot at it. And usually they did. (Laughs.) But that operated out of San Diego.

Jonathan Dembo:

How long were you captain of the destroyer?

Richard W. Stewart:

About a year and a half.

Jonathan Dembo:

So that would have been from forty-five to forty-seven.

Richard W. Stewart:

At which time I retired from active duty in the Navy. And with the mistaken impression that I could make a fortune on the outside.

Jonathan Dembo:

So it wasn't that you were particularly dissatisfied with the Navy, but you thought you saw greener pastures outside.

Richard W. Stewart:

I was dissatisfied because we were required to operate the ships with reduced crew, with the same responsibility, and found it awfully difficult to handle. Our ship was ordered to Pearl Harbor for an overhaul, and it's a five-day trip. So I sent a message off and it really got me in trouble with the admiral, but I didn't feel it was safe to go unless I had eight machinists mates and water tenders. So I sent that while I was at sea pulling targets. When I came back, the chief of staff and eight men with their seabags were lined up at the dock. The eight men to make up what I had demanded; the chief of staff to chew me out, which was his job. But we got there safely. And without those extra eight men, we were down to minimal officer compliment and crew, and it was just the “bring Johnny home” idea. Everybody was getting out of the Navy, but the ships were still supposed to do the same thing. This wasn't working. I decided I didn't want any more of that.

Jonathan Dembo:

So what did you do after you left the Navy?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I started looking for a job, which was not too unusual. I did go to work for General Electric.

Jonathan Dembo:

What did you do at General Electric?

Richard W. Stewart:

Engineering in the air conditioning department in Bloomfield, New Jersey.

Jonathan Dembo:

And what were your responsibilities there?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I was in system design. I had at least one nice patent to my credit, an automated steam turbine design air-conditioned system for a veteran's hospital. But unfortunately, about that time, not too long after we'd bought a house in New Jersey, my wife, it turned out, had inoperable cancer. Nothing much we could . . . we did everything that could be done. And she had wanted a house on the beach in New Hampshire out at Lake Winnepasaki. And I decided, “Well, by God, she's gonna have it.” And she did, for thirty days. She got about a month.

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you have any children?

Richard W. Stewart:

No, we had no children. I quit the job to take care of her. And . . . started over again.

Jonathan Dembo:

This was in. . . .

Richard W. Stewart:

She died in 1949. Or 1950, I'm sorry, she died in 1950. That left me broke, in more ways than one.

Jonathan Dembo:

What did you do then?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I got another job in the air conditioning business. In 1953 I married again, with my present wife. Started picking up the pieces.

Jonathan Dembo:

Were you still in New Jersey?

Richard W. Stewart:

No. I came back to the Baltimore area, where she went to school. And the Baltimore area had been home to us for a long time.

Jonathan Dembo:

So you're still located in Baltimore?

Richard W. Stewart:

No, no. After a few years of mediocre success I found a job with the Naval Oceanographic Office. So I spent the next twenty-odd years with the Naval Oceanographic Office.

Jonathan Dembo:

When was this?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I started there somewhere around fifty-seven. And I worked there for the next twenty-two years. So altogether I was on the Navy payroll for thirty-two years. As an officer and civilian. Now, while at the Naval Oceanographic Office I was largely in ship management division although some of the time I was in engineering development.

Jonathan Dembo:

What does the ship management division do?

Richard W. Stewart:

Ship management division had a dozen ships working around the world, and I was responsible for planning and supervising the overhauls and so on.

Jonathan Dembo:

What were they looking for? What were they doing?

Richard W. Stewart:

Three of them were research ships, the rest of them were survey ships.

Jonathan Dembo:

Is there a difference?

Richard W. Stewart:

There is. The research ship can be assigned almost any project. The survey ship is deep-water surveys or coastal surveys. During that time, I was assigned for three years on the staff of the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet as a civilian, from 1967 to 1970. They moved us out there lock, stock, and barrel.

Jonathan Dembo:

To where?

Richard W. Stewart:

Hawaii. It was a hard ship assignment, but I was a dedicated public servant for only fifteen percent extra pay. (Laughs.) Three years in Hawaii--that was my Vietnam War experience. I was a consultant in oceanography. There were more admirals on the staff than there were civilians. Three of us on the staff had been at Pearl Harbor during

the war: one Vice Admiral Bob Burger, the other was a fleet dental officer, and I, as I said, the civilian on the staff. And we would sometimes stand up there on the Fleet headquarters and watch the mocked-up Japanese planes come in and talk about it. My office was down closer to the harbor, and they would come over there--the Japanese planes--and the yeoman would have to pull me out from under the desk.

Jonathan Dembo:

Tell me, what was the typical mission of the oceanographic surveys?

Richard W. Stewart:

Basically, we were concerned about the surveys in Vietnam.

Jonathan Dembo:

So most of these were done in the South China Sea, that area?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah, but actually we also had ships working in the Sea of Okhotsk, north of Japan. That was pretty touchy. In fact, one of our ships was captured there.

Jonathan Dembo:

The PUEBLO?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah. Which included at least. . . .

Jonathan Dembo:

Was that one of your ships that was. . . ?

Richard W. Stewart:

Yeah.

Jonathan Dembo:

Were they really oceanographic survey ships, or is that what their mission really was?

Richard W. Stewart:

Well. . . .

Jonathan Dembo:

Is that a secret? Are you not supposed to say?

Richard W. Stewart:

They were there for a purpose.

Jonathan Dembo:

At least they weren't flying over China today.

Richard W. Stewart:

Anyway, they were not welcome there. But it was a nice three years. My younger daughter started kindergarten; she was three when we went out there. She's with me here today as my designated driver. Apparently they seem to think I need a

designated driver. A couple of years ago I flew to Atlanta from Pass Christian and had dinner--it's only three hundred miles. But a friend of mine has a nice little airplane. The next day I came home and I couldn't see out of one eye. Well, this carotid artery splits--part of it goes to the brain, part to the eye. My brain I don't use anymore, it spared that. But a little clot went to the eye, which has impaired the vision in one eye. It's getting better gradually. But my family doesn't want me to do a whole lot of driving. Why did it have to go the wrong way? I have no need for a brain whatsoever.

Jonathan Dembo:

I thank you very much.

Richard W. Stewart:

Well, I have enjoyed talking to you.

[End of Interview]

Richard L. Stewart was my father-in-law and passed away before he could review his oral history. Is it possible to obtain a transcript of his interview for our family history? Thanks!