| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

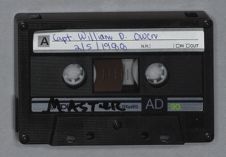

| Capt. William D. Owen | |

| February 5, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Morgan J. Barclay:

Captain Owen, you were born in Vermont I take it. Did you spend most of your youth in Vermont?

William D. Owen:

Yes. I was born in Poultney, a little town on the west side of Vermont directly on the New York state line, near the south end of Lake Champlain. It's located in an area with a lot of Revolutionary War history. It's north of Bennington and Brattleboro and near other wartime areas like Saratoga, N.Y.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It's beautiful country.

William D. Owen:

It's a good place to be from. I went through grade school there. The town had no high school but there was a Methodist institution that was the equivalent of a prep school or high school. It was a boarding school for Methodist ministers' children. We were sent there. The town paid our tuition, but we had to buy our books and pencils, which was unusual. I graduated from there, and by the time I finished, it had been converted into a junior college called Green Mountain Junior College. I graduated from there one week and then went to the Naval Academy the next week.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What prompted you to go into the Naval Academy?

William D. Owen:

It was during the Depression and I needed an education. I had written two Senators and one Representative when I was a junior in high school. One of them said, "No chance. No openings." The third one said that in two years I could compete for an appointment by

taking the civil service examination. I was a sophomore in the junior college when around Thanksgiving time I got a notice to report to the county courthouse in Rutland and take the competitive examination. I reviewed all my high school subjects, went on up there and took the exam, and got a first alternate. I think there were three appointments open--three principals and three alternates for each principal. The oddball thing about it was that all three principals were from Montpelier, which is the capital of the state. I kind of thought that smelled a bit. Anyhow, I graduated from Green Mountain Junior College, and my records were transferred to Michigan State. I had no assistance whatsoever, so I was going to have to work my way through.

Then one of the principals for the Naval Academy failed his physical examination, so that meant as first alternate, I received an appointment to the Academy. I went, and I'm glad of it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Can you tell me a little bit about life as a cadet and your reaction to the Academy?

William D. Owen:

I didn't have any trouble at all. I enjoyed it very much. It was kind of rough. You had to swallow your pride and keep your tongue in your cheek a lot to get through it. You were kept very busy and that kept you out of trouble a lot. Having had two years of college helped a lot academically, the first two years, anyway. I wasn't big enough for many sports, but I was on the boxing team.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I saw in the yearbook a picture of you with the name "Punchy" Owen as the caption.

William D. Owen:

I got tagged with that name by a friend of mine.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you like boxing?

William D. Owen:

Yes. I had done quite a bit of it in high school and junior college. One of the

students in high school and junior college was sponsored by the Methodists. He had been an ex-professional boxer. Instead of taking gym, I took boxing for about four years. I picked up a little expertise along the way.

I also was the circulation manager of the monthly magazine.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you do any writing as a result of that activity?

William D. Owen:

No. I wasn't in the editorial or feature department. I just sold subscriptions and saw that everything was delivered. My job was to see that we didn't go in the hole.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Management.

William D. Owen:

Normally, you do that in your senior year, but I did it all three because the fellow that had it had to leave the Academy. I stepped in and took over.

We had three midshipmen cruises. The first one was to Europe as a youngster to Cherbourg, Southampton, back to Guantanamo, and then into the Chesapeake Bay. While in Southampton, most of the midshipmen went on a four-day leave to London, but I took my four-day leave and went up to Northern Wales to visit my grandmother. It was a very nice experience for me. She died shortly thereafter.

The second class summer, we had destroyer cruises. We went up to West Point and Boston and Newport, Rhode Island. For the first class cruise, since the war was on the horizon, we didn't go to Europe, we went up and down the East Coast. Both of those cruises were in the old battleship NEW YORK.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were the midshipmen cruises? Were they basically a summer?

William D. Owen:

Yes. We would leave in June and come back at the end of August. Then we'd get about two weeks leave before coming back and starting academics again.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you travel together or did they split you up into different assignments?

William D. Owen:

Do you mean for the summer cruises?

Morgan J. Barclay:

Right. Would your whole class go on the same cruise?

William D. Owen:

Yes. Your whole class would go and they would split you up on whatever ships were available for the cruise. Present-day practices are much different than that. They send you out into the active fleet. They put a few here and a few there on different ships and squadrons and submarines. Later, when I was in a ship off of Vietnam, I had two or three midshipmen to come aboard for a couple of weeks during the summer.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I imagine the midshipman experience was a good learning experience and gave you some good exposure to what ship-board life was going to be like.

William D. Owen:

Our class graduated early on February 7, 1941. That's why we have our reunion at this particular time in the year. We didn't have a June week. What they did was to cut off our post-cruise vacation. There was no Christmas vacation. There were academics right up till the football games on Saturdays. A lot of the marching and drills were dispensed with. We didn't suffer from lack of credentials or academics. February the seventh came along and we were off and away. I was one of twenty-three midshipmen who had eye problems and were not commissioned. But since we were very nearly qualified, they kept us there to instruct the first group out of OCS--midshipmen that came through there. They were called the "ninety-day wonders." There were twenty-three of us.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The "23 Club."

William D. Owen:

I taught seamanship, while others taught navigation, gunnery, and whatever else they were teaching at the time.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you stay on at the Academy?

William D. Owen:

I stayed right on at the Academy and wore the same midshipman's uniform except

that we got a quarter-inch stripe around the sleeve. The upper half had the lieutenant junior grade stripe, plus the midshipman star and midshipman cap. They called us "passed" midshipmen. There hadn't been any passed midshipmen since 1905 or something like that when midshipman graduates went to sea as passed midshipmen, and after a year, they were commissioned or something like that. Out of the twenty-three, five of us were commissioned. Our eyes got good enough to be accepted. I went aboard the USS YORKTOWN, CV-5, which had just arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, from the Pacific.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was this?

William D. Owen:

We had just finished up our teaching job. It was the last week of May, 1941. I was the real oddball, going aboard as "passed" midshipman Owen at the quarterdeck, with the same uniform and midshipman cap. They didn't know what I was. There were two of us reporting to the YORKTOWN out of that five. "Jocko" Clark, [Joseph J., USNA 1918] who later was vice admiral in the Navy, was the executive officer. He looked at me and said, "What are you?" I had a long story to tell him.

During the summer, we made anti-submarine hold-down patrols for the British from Bermuda to the Azores, to the Canary Islands, and to Trinidad and back up. It was a rectangular patrol. There was not much wind and it was very hot. When it started to get cool, they sent us to Argentia, Newfoundland, at the end of August. We arrived in a snowstorm. It was quite a change. Our duties then were to escort the troop transports from Canada over to the island area where the British Navy took over. Then we would escort dependent women and children back to Canada.

After making one of those crossings, we came down to Portland, Maine, for

Thanksgiving, and then down to Norfolk, Virginia, in the first week of December to get some newfangled guns called twenty-millimeters on board. Four of us had gone to Annapolis for the weekend to visit girlfriends. On Sunday afternoon we were listening to a Redskins football game when we were told, "Everybody return to the ship." Pearl Harbor had been bombed.

We got together by phone, got our wheels, and got back to Norfolk. Shortly thereafter, we sailed. We loaded a large number of recruits from the Naval training station who had put in only about half of their training time. You could recognize them because the seats of their trousers were dirty. Some of them didn't know how to use soap yet.

We went around through the canal and unloaded a very large amount of wartime equipment that we had loaded on board at Norfolk. Then we went on up to San Diego, arriving there around New Year's Day, 1942. Ten days later, we took her out loaded with fighter aircraft for the defense of Samoa. They were loaded by barge and taken off by barge. They weren't flown, because there were no aviators to do it except the regular ship's [TF 17] squadrons.

After unloading the aircraft in Samoa, we joined the Pacific Fleet and conducted the first offensive of the Pacific, when we bombarded the Marshall and Gilbert islands. That was on President Roosevelt's birthday, January 31. Afterwards, we came back into Pearl Harbor. It was our first time in Pearl Harbor since the Japanese attack, and we saw the debacle. Even then, there was lots of oil still floating around under the pier. We stayed there for about a week.

Around the tenth of February, we departed for the Coral Sea. We were down there for quite a while patrolling south of New Guinea, conducting raids on ports and airfields

around Salamaua and Lae. Then we got involved in the Battle of the Coral Sea, which was the first one in Naval history where the ships themselves were never really engaged. They never saw each other. The exchange was all done by Naval aircraft. My battle station was up in the anti-aircraft director, the one aft of the stack. We were lucky to get out of that in one piece. We got one bomb down the forward elevator that raised it a foot or so and another one off the port quarter that put a big gapping hole in the fuel tanks. One went through the catwalk on the starboard side forward. This was the battle where the LEXINGTON got hit so badly that it sunk, mostly because the gasoline system caught on fire. We didn't know too much in those days about damage control, but we learned later on through incidents such as this.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You must have been subjected to pretty heavy fire at that time.

William D. Owen:

Yes, we were being attacked by dive bombers. We had our fighter squadrons out to protect us but a lot of their planes were still able to get through. I was in the gunnery department. I was up there seeing it all. It was an all-day affair. There were about three or four different attacks. After it was over, we retreated during the night to the southeast and then went on to anchorage in Tongatabu, the capital island of the Tonga Islands. It was owned by the British at the time. We refueled from A. L. number one--A.L. #1. It looked like a wooden hulled ship from the Civil War. We took off the next day for Pearl Harbor.

Morgan J. Barclay:

In spite of taking four hits, you were able to patch things up enough to move along.

William D. Owen:

We had one bomb go down on the main deck just underneath where my battle station was. It was a twelve-inch armored projectile and it was deflected down to the armored deck underneath the soda fountain area and blew up down there. When we got in to Pearl Harbor, we did the unconventional thing of re-gassing, re-fueling, re-arming, re-supplying,

and welding all at the same time while in drydock. We needed to get out to Midway. Through the great success in breaking the Japanese code, we had the intelligence that the Japanese were en route. That was a great piece of work. I think we were in there for about two days and then off we went.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Normally, that would have been probably several weeks work.

William D. Owen:

Normally, you weren't able to re-gas, re-arm, re-supply, and weld at the same time; however, we got out of there in one piece.

Another one of my duties on board the YORKTOWN was treasurer of the ship's services. In those days, the supply department had not yet taken over the administration of the laundry, the barbershop, cobbler shop, soda fountain, and that sort of thing. I had a little office in a space on the laundry deck. That was also where the battle station was for the repair party to fight fires and explosions. The bomb that went down through the superstructure exploded right underneath this repair party. The officer in charge received a medal of honor for his work of gasping through the last minute work of turning on the water and directing the fire fighting.

My little office was in one of those expanded wire cages that could be locked up, because I had a safe in there. There was about ten thousand dollars in cash in the safe, because we had been out for quite a while and I had had no chance to deposit it. During the course of the battle, a piece of bomb fragment hit the knob on the safe and I couldn't unlock it. I didn't have time to get anybody out there to do it because I had my regular job on board ship to do, too, I was responsible for getting the division ready to go: re-armed, re-supplied, and re-provisioned. When we got to Midway, the ship was sunk, and all that money went down with it. There were also a couple of vehicles that belonged to the ship's service

department. They were tied up in the overhead and they went down with the ship, too. For three or four years after that, I got letters from the Navy Department, wanting to know about the money and equipment.

When we got back to Pearl Harbor after the ship went down, it seemed like every company we had done business with sent us duplicate bills, even though we had paid them. I had only my memory to go on, but we had paid everything before we left. I guess they had been worried about whether we were going to come back.

Morgan J. Barclay:

In the Coral Sea battle, what kind of casualties did you incur?

William D. Owen:

We had a bomb to go off right on the main deck aft of the stack where there were two 1.1 quad mounts. One was stacked above the other almost. I looked down after the bomb went off and the officer in charge of the mount was the only one left standing. As for the rest of them, all I could see were rib cages or the lower half of their torsos. They were just cut in two. There were probably about twenty people in that spot, another thirty or forty up forward, and a few here and there and around. We probably had around seventy-five killed at the Coral Sea.

One interesting incident happened in the dark of the night. Two airplanes were flying around wanting to come aboard. We didn't know what carrier they were from. We noticed that their amber lights were a different color than ours. We thought they might be left over from the LEXINGTON. Of course, it was darkened ship and the airplanes were dark except for those little faint lights. Suddenly, we realized that they were Japanese planes trying to find a place to land. They were mistaken, too. We opened up fire with everything we had and they disappeared in a hurry. I don't know where they went. Night carrier landings at that time in the war were unheard of. If they had been ours, we would have gotten them on

board one way or another, we could always have lit it up.

Morgan J. Barclay:

In the darkness, it was difficult to figure out who was who.

William D. Owen:

I can still see them flying by.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I remember reading about some incidents along that line that happened on numerous occasions. They ended up getting shot down, too. You got yourself back together in a few days, then headed back for Midway. Can you tell us about what happened at Midway?

William D. Owen:

We were with the ENTERPRISE. The YORKTOWN and the ENTERPRISE were the only two carriers available at that time. We had a number of cruisers, one of which was the PENSACOLA. We were a couple of hundred miles southwest of Midway when an engagement started that was another one of those "no see 'ums." We couldn't see the surface ships at all. The attacker forces passed in midair almost, but not in sight of each other. While we were bombing and torpedoing them, we were getting the same thing.

A Japanese Val came down and let its bomb go. I could see all four veins behind the bomb and I knew it was coming right at me. Fortunately, the ship was in a hard port turn and it passed overhead about fifteen to twenty feet. In my innocence, I emptied a string of forty-five caliber pistol shots into the plane. It did crash right behind me, but I think it wasn't my pistol shooting that did it!

Shortly thereafter, we had a bomb go down the stack about fifteen feet away. It exploded on the protective grates--armored plating with slots in them--that are put in there for the fires to go through. It blew all the fires out in the boilers.

We finally got back up to eighteen knots of speed when we had a coordinated torpedo plane attack. A coordinated attack means they come in at right angles to each other so that

whichever way the ship turns, one of the group is going to get you broadside. Two torpedoes hit us midship portside. During our preparations, we had taken every thirty-caliber machine gun available and welded them to stanchions along the whole outside of the ship on the flight deck. They were manned by plane-handling crews or anybody else who was available. When those torpedoes hit, the explosion lifted some of those gunners a good twenty feet into the air. I don't know whether they landed on deck or went overboard. That was at portside midship, which was on the opposite side of the ship from where I was. That brought us to a halt! The ship started flooding. We were keeling over probably somewhere between 25 and 30 degrees. It was difficult to stand up, particularly with the gas and grease and oil running out of the planes that were still on board, both on the hanger deck and the flight deck.

Not too long thereafter, we got the word to abandon ship. I was a member of the 3rd Division, and my job was to help get everybody off. I went down to my station, which was on the starboard quarter. That was the high side, because we had keeled over to port. One destroyer came alongside and practically tied up. She was getting quite a bit of damage to her superstructure due to the rocking. We got all of the wounded off. We practically hand carried them across. All of a sudden we found that there were just three or four of us left, so we decided that we better get off. We could see destroyers circling around a mile or two away. I stripped down, leaving my skivvy shorts on. I had a life jacket. In those days they had pockets, so I put my wallet in one. I threw my forty-five overboard and went down the knotted line, dropping the last ten or so feet into the water. All the planking and other stuff that had been available to float on in the water had already been pushed over aside for other people. I had thrown one of those new tightly-wrapped aviation tires from the aviation

supply room into the water. I caught up with it and pushed it for about a couple of hundred yards before it proceeded to sink. I thought, What futility! The water was warm and I didn't see any sharks around, but I was covered in oil. I was about to get to a destroyer when it decided to get out of there because of a suspected sonar contact. Finally, I got picked up about another half a mile further down by the destroyer BALCH.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were you out there?

William D. Owen:

Oh, probably an hour or so of swimming. I had a classmate on board the BALCH named Roger Allen. He has since died. Roger had the midwatch on the after anti-aircraft 1.1 battery. He gave me his peacoat, and I slept in the ammunition handling room underneath the gun. The executive officer gave me a pair of searsucker trousers, a rope for a belt, an Hawaiian luau shirt, and a pair of sandals. (We called the sandals "go aheads" because you can't go backwards in them.)

The next morning, we got a highline ride to the cruiser PORTLAND, which was also in the task force. I had another classmate aboard that ship, and I slept on the floor in his room. That's where I cashed my sixty-dollar check that I had in my wallet. It was Uncle Sam's dried out money. I bought myself some marine work trousers, a shirt, a belt, and a pair of shoes. That's all they had available. I spent the night and then got transferred by highline to the submarine tender FULTON that next morning. On board the FULTON was one of the students I taught at the Naval OCS School. He was glad to see me and put me into a very nice stateroom.

We proceeded back to Pearl Harbor, where they divided officers into two groups: one to stay at Pearl Harbor and another to go up in the hills to where the old Marine Ranger group had vacated. (They were the equivalent of Seal teams. They were raiders who would

go on shore at night on the various islands.) There were bunks and cots and netting in fairly good buildings. I was in the group sent up there and our job for the first six weeks were to get everybody squared away--establish new records, medical records, new shots, etc. We were allowed two beers a day per person or something like that.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Basically, you had to start all over.

William D. Owen:

Yes. Then we got relieved by the other half and went down and got a chance to enjoy the B.O.Q. down at the base at Pearl Harbor. A couple of weeks thereafter, I got orders to go put the cruiser BIRMINGHAM CL-62 in commission at Newport News and to go via the Naval Fire-Control School in Washington, D. C., at the gun factory. I came back to San Francisco on one of the two old Navy transports they had up there. I think it was the SHAMONT. I was there for about thirty days before getting my orders to the fire control school and to the cruiser BIRMINGHAM. I put the BIRMINGHAM in commission. We were afloat in the Chesapeake Bay for forty-five days, shaking down--doing all shore battery fire and anti-aircraft fire.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was this?

William D. Owen:

May of 1942. After our shakedown, we went to the Mediterranean. This will give you a point in time for the Sicilian invasion. We went to Algiers and Oran, and then picked up the amphibious group making their landing at Gela and Porto Empedocie. After the landing was made, we stayed in the vicinity for probably a week as gunfire in support of the advancing troops. The coastline of Southern Sicily is flat, then it rises up in a mountainous range with valleys behind them. The Germans were behind the first row of mountains, and their fighter planes would come zooming up over that mountain crest and zoom down on the beaches and drop bombs on anything they could find, particularly LSTs that were stuck

on the beach. That meant you had to be real fast on the draw.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were to shoot them down?

William D. Owen:

Yes. I was fourth division officer in charge of the after group of five-inch 38 guns. There were three of them: one center line and one on each side. I was the director officer up in the thirty-three director, I guess you would call it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Were you successful?

William D. Owen:

We were mostly concerned with gunfire support of the troops ashore. We were lobbing six-inch projectiles up in front of the troops as close to them as we could, just kept working ahead of them. For the troops who had gotten to the hills, we had to shoot the projectiles up high and lob them down like a mortar. To do this we used half-charged cases of powder. We had to alter the computers down below to accommodate the different trajectory. Of course, we would get a higher angle of elevation. We'd shoot them up there so they'd come down with a sharp enough angle that they wouldn't tumble down the surface of the back slope. They would explode on contact. There were some troop concentrations back in those hills, five or six miles away, that probably accounted for quite a few casualties.

After Sicily, we came back to Norfolk, Virginia, re-armed and re-provisioned, and went through the Panama Canal and back to Pearl. After being at Pearl Harbor, for a short time, the ship was sent to the Solomon Islands. I was one of four officers who had received orders to go back to the States to put another cruiser into commission, so I was not with the BIRMINGHAM; but, she really got banged up out there.

Morgan J. Barclay:

So you weren't with the ship?

William D. Owen:

No. I was detached at Pearl Harbor. I had orders to put the cruiser ASTORIA, CL-90, in commission at Philadelphia.

Morgan J. Barclay:

They obviously took advantage of the experience you had gained.

William D. Owen:

It was a break for me. The ASTORIA was a sister ship of the BIRMINGHAM, the only difference in the two being that the main directors were antipodes. On the BIRMINGHAM, the main battery director was higher than the anti-aircraft director; on the ASTORIA, it was the other way around. I was the defense officer on the ASTORIA. The ship went into commission in May of 1944. We did shakedown in the Gulf of Trinidad, went through the canal and up to San Diego, and then on out to Pearl Harbor. We were attached to Task Force 38, which alternately would become 58, depending on the mission. Task Force 58 was a surface type and Task Force 38 was the anti-aircraft type. Both task forces were composed of the same ships. There were usually three or four groups within a task force, and towards the end of the war there were five. When you looked on the radar scope, you could see them all lined up in a row like pinwheels. We had a tremendous force out there towards the end.

I got out there in the ASTORIA just in time to get into the tail end of the battle of the Philippine Sea. On the way out, I crossed paths with the BIRMINGHAM. She came into Pearl when we were almost ready to leave. I went over to have lunch. She had been alongside an aircraft carrier fighting fires, when the carrier blew up. All of that flying steel came right across her superstructure. There were eight-hundred casualties topside, some wounded and some killed. Most of the ones I had had in the fourth division had still been there, and they suffered the most losses. It hit the aft anti-aircraft director and the two

mounts on the starboard side.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Those were people you had served with.

William D. Owen:

Yes. The boot camp people that we had on the BIRMINGHAM had all come out of the South Dakota-Nebraska area. They were a bunch of real big guys--Swedes, Norwegians, and Germans--real fine people. On the ASTORIA, the boot camp people had come from the New England area. We had a bunch of people from New York City, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Philadelphia, and New Jersey. When we were loading our five-inch mounts, we needed a pretty good-sized guy to put those fifty-pound projectiles in. We had to search pretty hard to find a real husky guy that wouldn't poop out too fast.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was the name of the carrier that exploded?

William D. Owen:

It was the USS PRINCETON.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was the explosion a result of an accident or from damage they had received?

William D. Owen:

They had been in battle and couldn't quite get the fires out before the ammunition exploded. They couldn't get the bombs overboard that were still in the hanger deck.

Morgan J. Barclay:

This was at Pearl Harbor?

William D. Owen:

No. It happened out in the war zone. The ship was on its way to the States for repairs and had stopped at Pearl when I went on board and had lunch. I saw my junior officer, who later became the director officer, and he had had his nose peeled back in part of the action. I got a firsthand description of what had gone on.

Coming back to the ASTORIA again, we got out there and did ninety steady days of steaming. We were in the area of Iwo Jima and the South Indo-China Sea, and the kamikazes were a daily occurence. I think the ASTORIA got sole credit for eighteen kills.

Plus, there were numerous other assists that could never be determined because there was more than one ship firing. Amongst my records, I have an analysis of each shootdown. It was classified as confidential then but it wouldn't be now. I'll dig it up and give it to you. It gives the course, speed, altitude, angle of attack, and how many rounds were fired, and the results.

We went back into port on the eastern side of Luzon for thirty days of relaxation. Then we went way out in the boonies, someplace like Ulithi. We went out and did some anti-aircraft exercises, some surface shooting practices, and then went back up to join Task Force 38 again. After ninety more days of steady steaming, we got back to the States.

We also took part in the attack on Iwo Jima. We worked over the west side of the island, including Suribachi. One night I fired over five hundred star shells through my director. The Japanese infiltrated our lines at night. The marines were next to them on the west side of the beach. We ended up, the last hour, covering the area with thirty-six inch searchlights to help them out.

Morgan J. Barclay:

To try to locate the Japanese?

William D. Owen:

Yes. We did a number of shell bombardments, mostly at night on the islands off of Kyushu, south of Tokyo. We also went on up north into the straits on the northern side of the island and did some bombarding up there in the ammunition depots and oil factories and stuff. We did that at night. You could do it pretty well with the computer. You could get your area, get your fixes from radar, and pinpoint your first shell within a hundred yards of where you wanted it. Then you could walk your shots around.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Kind of do a circle?

William D. Owen:

Yes. You'd start at one point and walk it back and forth, up and down. We'd fire two or three hundred rounds and get out. Then we'd go back and join the task force.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Night activity would be safer from your point of view? Less chance of air attack and things like that?

William D. Owen:

Yes. After the bomb was dropped in Hiroshima, they started sending ships into Tokyo Harbor. We had been at sea for so long, however, that we were sent back to the States. All of us that had been out there a long time headed back to the States, carrying what were called "forty-four pointers." (If a person had forty-four points based on the number of months he had been on active duty, he could go back and get released. That was for the reservists and the draftees.) One whole day we spent as a task group, steaming, with ships coming alongside, and our taking on passengers by high line on both sides of the ship. We took eight hundred enlisted men and ninety officers back to the States.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It must have been crowded.

William D. Owen:

It was. We were "hot bunking" is what it amounted to. Every possible space was used and we ate around the clock.

We took a great circle route back. The first ships detached and went to Seattle, so we got pretty close to the Alaskan peninsula. Some peeled off at San Francisco; we peeled off at Long Beach and, the rest went to San Diego. I clearly remember the big crowd at the pier. Ella Mae Morris was there with a band singing, "Welcome Home." She was a popular singer at that time. Everybody started to get shore leave. Some of the officers on the second half of their shore leave had gotten back to Philadelphia--that's where the ship went into commission and a lot of them had married back there--when we got orders to go back out to Task Force 38 in the Pacific.

We operated with a carrier task group (two carriers, a cruiser division, and a dozen destroyers) out of Saipan mostly. We'd go out and operate aircraft during the day and come in at night and anchor on the west side which was sheltered. (The winds were from the northeast to the east.) About once a month we'd go out to Guam for reprovisions at Apra Harbor. I was the navigator and operations officer at that point. I put four years in that ship. I had been communications officer, main battery assistant, and the assistant gunnery officer.

Finally, we got back to the States via Pearl. I got orders to go to a Naval postgraduate school in flight communications for one year. After finishing that, I got orders to be the communications officer for Battleship Cruiser Force Pacific Fleet based in Long Beach. About a year and a half later, we joined with Destroyer Force Pacific Fleet to become Cruiser-Destroyer Force, because we didn't have any battleships by that time. Then I was ordered to London, England, as communications officer and advisor for communications to the Joint American Military Advisory Group Europe, which was the headquarters for MAAGS (Military advisory groups.) We were to review the needs of Western Union, the forerunner to NATO.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was this?

William D. Owen:

This was from 1950 to 1952. I went over there at Christmas of 1949.

Morgan J. Barclay:

As communications officer, what type of expertise would you be sharing with these people?

William D. Owen:

I ran a communications(?) for the staff, to begin with, and also was a speech writer plus a few other odd jobs. The MAAGS from countries like France, Belgium, Netherlands,

Norway, Denmark, England, and Italy, would send in a shopping list. Our job was to review the shopping list. We would go to the other secton of the staff--Planning: North Atlantic Treaty Organization--to see what their plans were and see if what the countries wanted fit into the plan. We looked at it from availability of equipment (what we could give them) and what was compatible, so everybody would be compatible with each other. Then we'd draw up a shopping list and take it back to the CNO for approval.

Morgan J. Barclay:

So you were doing a lot of communications, negotiations, and evaluations back and forth between the two groups.

William D. Owen:

Yes. I was there for two years. I came back to the States with orders to be commanding officer of the destroyer GATLING, DD 671, named after the guy who invented the Gatling machine gun. My shipmates called it the "Battling GATLING," and other ships called it the "Rattling GATLING."

Morgan J. Barclay:

What year was that?

William D. Owen:

1952. I took command in Newport around the Fourth of July, 1952.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How did you like the duty as commanding officer of a destroyer?

William D. Owen:

Great! Great! You're "Mister Everything," because you don't have much back-up. You have a lieutenant commander executive officer and maybe one or two senior lieutenants aboard, a gunnery officer and chief engineer. The rest of them are fresh-culled ensigns or j.g.'s. It means you're on the bridge all day and all night.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Basically, there wouldn't be too many experienced officers with you.

William D. Owen:

Usually, we had about sixteen or seventeen officers on board and close to three-hundred enlisted people. The GATLING was a 2,100-ton destroyer with five single five-

inch thirty-eight mounts and a Mark 383 director. I grew up with both of these and I knew them inside out. The ship had just returned from Guantanamo Bay on shakedown. It had been in mothballs in Charleston before being put back into commission. Unfortunately, while at Guantanamo, in an anti-aircraft exercise, mount one swung around and shot the barrel off mount two. There was an instant explosion, and the projectiles killed some people on the bridge. The ship had been taken to Philadelphia for repairs and was back in shape by the time I returned to the States to take command. We went out to do some anti-aircraft practice with the airplanes drawing a sleeve back of it about a thousand feet.

We got all lined up with everything and fire ranges clear, and the gunner officer said, "On target."

I said, "Commence firing."

Nothing happened. I looked around and saw that everybody on the bridge was on the other side of the bridge. I was the only one on the gunfire side. They were all gun-shy after that accident. So were the crews in the gun mounts and in the directors.

So I said, "All right, let's try it again."

We got our target. I heard fire control put the phones out. I heard fire control say, "Solution."

Dunbar said, "On target."

I said, "Commence firing."

Nothing happened.

I said, "All right, I'm coming up to the director." I went up to the director, put my headphones on, got on target, got a solution, and said, "Mount one. Commence firing."

Nothing happened. They had frozen down in mount one in the first turret. So I went down to the turret. I took the gun captain's phones off, put the gunnery officer back into the director, and I said, "Look, as soon as you have this gun on target, I'm going to say, 'Commence firing.' I'm going to get this gun shooting."

We did. It was a big roar, but after that, it was no problem at all.

The second day underway, we went out to do a towing exercise. To do this, we had a thick, heavy wire cable. We could either flake it out on the stern, like the letter "S," or we could run it up and down on one of the sides of the ship and tie it together along the stanchions ____(?). The only thing about that, I learned, was that it could get into your propellor. It wasn't tied down tightly enough and it broke away, and I got a loop in the cable that got twisted around the port shaft. It didn't get into the propellor, but it got around the shaft through the strut bearing. I had to call in the Commander Destroyer Force Atlantic Fleet, saying that I had had an accident and I was coming back to port on one screw. I put the diver over after we got in and fortunately there was no damage. We got the wire cut and went back out to sea. The bosun mate was in charge, and it was his last day, (people were coming and going awfully fast at that time. There were two-year enlistments.) There wasn't anything much to do except say, "The buck stops here." We did, however, have a successful training period.

Then we went on Operation "Main Brace" in July. We operated with NATO ships around the British Isles and on up to Bodo, Norway. It was very rough up there. We came back and in January went down to the Caribbean for what was called "Exercise Springboard." That was our annual winter training ground. We got back in April and, lo

and behold, the whole division got ordered to Korea. We went down through the Panama Canal, up to San Diego, out to Pearl, Midway, and finally Yokosaka. We operated with a task group off the East Coast of Korea for a few months. When the truce was declared, our division was broken off and sent down to the southern part of Korea to the big island of Cheju, where there were fifty thousand North Korean prisoners. We were to help provide security. We spent thirty days of just steaming around in squares and circles and having a fishing party or swimming party occasionally.

In October we got orders to go back home, [via] around the world. We went down to Manila, back up to Subic, where we got provisions, and then went to Saigon. We went up the river and tied up at the end of the pier. We had tea for the local French people and they entertained us with liquor in their places. Then we went to Singapore and joined up with the carrier LAKE CHAMPLAIN. We continued on around the world to Colombo, Ceylon, through the Suez Canal, to Nice, and then back to the Atlantic. We broke off near Bermuda; they went to Mayport [FL], and we went to Philadelphia. Our home port was Newport, but we went to Philadelphia for our regular overhaul.

We were in Philadelphia about three or four months--from Christmas until around March--when we went back to Guantanamo for a shakedown. We got back to Newport on the Fourth of July. We had been out of home port sixteen months, which was hard on the crew. Most of the officers' families moved around from Newport down to Philadelphia or back home.

After arriving at Newport, I got detached and was sent to San Francisco as officer in charge of recruiting and office of procurement for northern California and Nevada. I spent almost three years there. That was right at the end of the Korean War when the input that

had gone in four years previously for the Korean War, went out. The month after I got there the waiting list disappeared and my quotas were so high that they were impossible to meet. So I went from twenty-six recruiting stations to fifty-two. Everytime I saw a good supermarket place, I'd put a recruiter in there, too. I was like a Safeway--if they put a store there, I'd put a recruiter there, because there was enough business. I did that for almost three years.

Then I had orders to command the JOHN S. McCAIN; destroyer leader number three. I flew out to Hong Kong and took command there. I had command for a year and a half. I finished the deployment and returned to San Diego where I found out we had orders to home port in Pearl Harbor for six months. So my family and I moved out to Pearl Harbor. We were there for a year. We were deployed six months of that time, so I actually saw Pearl Harbor for six months. We were in and out, doing daily exercises and stuff.

The JOHN S. McCAIN was one of four brand new ships built in 1953. I was its third commanding officer. On the way home from our deployment, we left Midway with three other destroyers and did a full-power engineering trial. The ship had never had one. (You have an hour of warm-up time, then you steam at the designated maximum speed [a certain number of rpms] for four hours, then that is followed by another let-down.) We started off abreast of each other early in the morning. After the hour build-up, we got up to 39.5 knots. The maximum speed for those other destroyers was 32.5. I'd been to sea on one of those for a couple of years. We could have gone faster except we were running out of air to the blower. The blowers didn't have enough capacity. We were closing down the blower bearings with fresh water to keep it cool. They were getting too hot. We did 39.4 knots for four hours, which is the fastest I've ever been in a ship. It only took about one degree of

rudder to steer the course. The weather was nice. There was a rooster-tail that came up the stern that was at least thirty feet high. The ship's bow came up about ten feet. It was a thrill. Everything aft of the bridge was spray.

We got back to San Diego and then went back out to Pearl Harbor to start on another deployment. I got relieved at Subic Bay.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were you in command of the McCAIN?

William D. Owen:

A year to the day practically. I went to the Bureau of Naval Personnel for a couple of years duty.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long was your active Naval career?

William D. Owen:

Oh, I'm still going. I did thirty years. I did two years there and went to Norfolk and took command of the AKA 88, the USS UVALDE.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was that another destroyer?

William D. Owen:

It was one of those big old lumbering amphibious cargo ships. If we saw a ship on the horizon, we'd start backing down. It had only one prop and six thousand horsepower. The JOHN S. McCAIN had eighty thousand horses with four props and two rudders. It was a big old lumbering thing that carried those big LCMs (thirty-ton boats), with big cranes to let them down into the water. We made a deployment to the Mediterranean as part of the Sixth Fleet Amphibious Force. We did three or four practice landings there. Then we went down to the Caribbean and were relieved a year later. I came back as commanding officer of the Naval Communications Station in Washington, D.C. It's located south of Andrews Air Force Base at the intersection of 301 and route 5, called Cheltenham.

Morgan J. Barclay:

At the Naval Communications Station, were you primarily involved in training?

William D. Owen:

No. My job was to provide communications for the Navy Department and all the

bureaus such as BuPers, BuMed, BuSupplies and Accounts, CNO, OpNav, and communications to the fleet. The main station was at Cheltenham where the receivers were located. The transmitters were across the Severn River from Annapolis at Greenburry Point. They were the big old six-hundred-foot towers, very low frequency. The transmitters were like ones you see in a radio, but they were big enough to walk in. The tubes were higher than I was. There were five hundred thousand kilowatts. You could take a fluorescent light and touch it to the floor, and the metal rod at the other end would light up. You were standing in that much conductivity in an electromagnetic field. There was a substation at Lewes, Delaware, which communicated off shore with the cruiser that was the command ship for the President. After two years of that, I went to the joint staff in the Pentagon for two years as J6 communications and electronics director. The director was sort of chief of the troubleshooting division, which was methods and procedures. If anything went wrong, everything would come my way. My job was to solve them.

Morgan J. Barclay:

If there was a communication's problem along the way . . . .

William D. Owen:

Yes. A lot of modern communications is like water flowing in a pipe. You get valves here and valves there and the heading you put on the communications determines which route it takes. There can be some pitfalls along the way either if you put the wrong routing on it or some of the switches were bad.

I was a member of the six-officer-group that went out to the Mediterranean to investigate the torpedoing of the USS LIBERTY, the ship that the Israelis torpdoed, fired at, and strafed in 1966. Being a troubleshooter, I had to track down every message that had to do with that incident. Of course, it sounded like Pearl Harbor. Nobody cooperated here;

nobody cooperated there. In the Pentagon there is the operations room, and right next to it, is the security "gumshoe" super-intelligence communication and information division. There is a door betweem them, but it remains locked. Those guys were communicating with the LIBERTY, but when the joint chief of staff's operations tried to communicate with the LIBERTY, their messages went "splitter splatter" all over the world, never getting delivered. It was just like Pearl Harbor, nobody knew what the other one was doing. We came up with about fourteen good solid recommendations.

I went to San Diego as Commander Amphibious Squadron I and deployed shortly thereafter to Vietnam.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was this?

William D. Owen:

It was in 1967, I guess. I was actually in Vietnam in 1968. I arrived at the same time as the TET Offensive. I was up in Hue and north of Hue. I had two thousand Marines, a Marine helicopter squadron, and about six or eight thousand sailors aboard ship. My orders were to do whatever the Commander of the Seventh Fleet told the commander of Marines. South Vietnam was divided into four corps. The first corps was under the command of the lieutenant general of the Marine Corps. It was all Marine corps up there. Our job was to keep Que Son, the mountain overlooking the demilitarized zone. There's a river that goes up halfway to Que Son, right in the DMZ, that separated the two. There was a little outfit in there that would sweep the river daily. We'd send supplies to Dong Hoi(?), which was at the end of the river supply. Then we had to keep the route open from there up to the mountains with our Marines. They were ashore when I got out there and took over in January. We got them back about May, about sixty percent of them. The rest of them were decimated for various reasons. We replaced, of course, the strength. We went down and

did a landing in Danang Harbor. General Cushman was the general in charge down there. If the fighting was getting too close to Danang, they'd send a rocket in there every now and then. We'd clean that out for them. We went back up north of Hue, where we made a landing in the dead of the night. You never knew who was the enemy. We just swept the place clean, got them back again, and did another landing by air. This time, forty miles (can you imagine an amphibious landing forty miles inland) south of Danang. We got them back.

I went back to the Philippines, got relieved there and flew back to the States. I got orders to the National Communications System in Arlington, Virginia, which is composed of all the federal agencies that have communications systems: the State Department, the CIA, DOD, and the GSA. Each of us had a representative that was up on the top floor. The idea was to coordinate so that we could send messages through any of the other people's systems. This was brought on by the stinking deal down at Santo Domingo. The Air Force was trying to land troops down there, and the Navy was offshore, but we couldn't talk to the Air Force, the Ambassador, the Army, or anybody else. Kennedy, after that, put out a list of ten things to do right away and that's when the NCS was formed. I stayed there the two years before I retired. It was very interesting. Thirty years went by too fast.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You've certainly been involved in a lot of different things in the course of your career. Your last assignment must have been a real challenge.

William D. Owen:

Yes. I ended up as the assistant deputy director for the last couple of months. But I was glad to get out of it. The director was a three-headed guy. He was the head of the Defense Communication Agency, DCA; the Communications Electronics director; and the NCS. He couldn't do them all. They had a civilian as head of the NCS. The O-7 of the

brigadier general slot was never filled. I finally talked my way out of the job I had, because there wasn't anything to do. I told them I was going to retire. I had had about twenty-nine years and six months in the military. Actually, it was the same as thirty as far as paper work was concerned. They said, "Well, how about filling in the director's job. The civilian's got some trips to do. Why don't you come on out here and do this job for the next two or three months?" I did.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Which assignments did you like best when you look back over the thirty years? Which did you find the most challenging and interesting?

William D. Owen:

I thought the seagoing jobs as commander were the most interesting. Being the captain of the destroyer was a lot more difficult than being captain of the cruiser.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Why is that?

William D. Owen:

When you're captain of a cruiser, you have a commander and lieutenant commander and heads of departments on board your ship--your gunnery officer, operations officer, chief engineer and supply officer, medical officer. . . . You have more depth of experience. When you're on a destroyer, it's like riding by the seat of your pants. You do the same things and more of them. There's a lot more maneuvering.

One night when we were in the Philippine Sea during the Korean Conflict, the squadron commander called me up. He said that one of our carriers was leaving for the States and they wanted to take a lot of airplane parts off of that carrier and put on the other carrier so that all that stuff would not go back to the States. (As it turned out, there were a lot of other things besides airplane parts that stayed.) Alongside the carrier was an ammunition ship. It was in the pitch black of the night, and I'm to go up there and put the

nose of my destroyer in between these two ships and run a highline from the hanger deck at the very end of the ship down to my number two mount and then get all that stuff aboard. We spent two hours alongside, in the pitch black of the night, with this ammunition ship so close you could throw a head line over to it. There was one advantage of unloading in the dark of the night; we had none of the things that would distract our attention. We could really concentrate on keeping our distance and our position. All we had to do was tell the helmsman to steer one degree to the right or one degree to the left, add a turn or take off a turn, while we just stood there like glue.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was it real scary not being able to see?

William D. Owen:

It was a little tense but we didn't have all those distractions that we normally would have had in the daytime. That was just one of those little instances.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You said this was during the Korean conflict?

William D. Owen:

Yes, just before the war was over. Another interesting incident happened when we went through the Panama Canal in the destroyer GATLING on our way to Korea. We had to give the command of the ship to the pilot. That was one of the Panama Canal rules. So this pilot told my helmsman, "Left, twenty degrees rudder," when he meant, "Right, twenty degrees rudder." I was right out there next to him and I looked at the helmsman and said, "No." The pilot never knew that he had said the wrong word.

When we went up to Saigon, we had to go up the Saigon River, which is winding like a snake. We would go up above the city, turn around, come back on down and tie up the starboard side to the end of the pier.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was this with a destroyer?

William D. Owen:

Yes. When we had to turn the ship around, the trick was to run the bow into the bank and let the current swing it around and then back off and come on down. We had to take a pilot with us and he was a Frenchman. I'd found a Frenchman from Providence, Rhode Island, that could speak a little French, and he was supposed to be my interpreter. He did a very good job. But this pilot wanted to turn the ship around by running it up into the bank, but we had a sonar dome underneath the number one mount, and I didn't want my sonar to get damaged. It was a big dome hanging down there. So while he was giving all the orders, I turned the ship around myself. Then I let him bring it in to the pier.

I was taking the same ship into the Boston Naval shipyard after the "Main Brace" expedition. We had gotten soaked so thoroughly from the high seas that one of the forty-millimeter wirings was soaked down and had to be replaced. Shipyard law says that you have to take a pilot when you get in near the pier, so I had taken on a pilot. Well, apparently, he hadn't been around destroyers very much, because when we were a ship's length from the pier he said, "All ahead, two thirds."

He was trying to go up almost to the end of the pier and get in a slot in front of another ship, but we were going by this ship and nothing was going on.

I said, "All back, full!" Then I said, "Pilot, I've got it."

I had to tell him that I had command. We came to a shuddering halt, otherwise that bow would have run right up onto the road. He didn't realize what sixty-thousand horsepower would do to you so fast.

There was another incident the last time I went out on the cruiser ASTORIA to Task Force 38. One night, the cruisers had been detached to do sort of a simulated surface attack

exercise. We were coming back and rejoining the carrier. We were coming in on the port quarter and our idea was to turn left and steam up in position. I'm in the ASTORIA, and the cruiser PASADENA was on our starboard bow about forty-five degrees. We were both wanting to turn to get in position when the carrier does an about-face, a 180-degree turn.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How did you get out of the way?

William D. Owen:

The PASADENA was going around and we were on a collision course. I saw it coming. I was on the bridge with the captain; he had the deck and we were at General Quarters.

I said, "Captain, the PASADENA is coming over!" Before he could say anything I said, "All back, emergency full," yelling into the port holes to the helmsman and the annunciator. Then I got on the phone and said, "Chief, give it all you've got because we're getting kind of close."

This is nine o'clock at night. The PASADENA was so close that she went left full rudder to get her stern out of the way. They came down our port side. The quartermaster rang the bell for nine o'clock as we passed each other at about fifty yards apart. Boy, that was a hairaiser. Those things happen so fast.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How much time was involved in that?

William D. Owen:

About a minute or two.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You have to react fast to avoid a catastrophe.

William D. Owen:

We had another incident in the GATLING enroute back from Singapore. We were in the Strait of Malacca off of Sumatra heading for Colombo, Ceylon. We were on the starboard bow of the carrier on a bent-line screen. He was going to change course so we

had to get the destroyer around to be the screen on the new course so that he could change his course. I was in the sea cabin right up behind the bridge. I heard all this commotion going on but nobody called me. (I had written up night orders, so I had the officer of the deck by the throat in case he did anything wrong. He was supposed to call me if there was a problem.) I got up out of curiosity and that's when I saw we were on a converging course with a carrier doing twenty knots. Just a year before in the Atlantic, one destroyer had been chopped in two by a carrier. This looked like a similar situation.

I said, "Right full rudder, all ahead, emergency full." That means give it all you've got.

The flight deck stands way out on a carrier, and I was so close to that carrier, that I was in the shadow of its flight deck. I could have chosen to go left or right, but I knew I would have more time if I went right. We scooted out of there.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What would cause that? An inexperienced officer?

William D. Owen:

Yes. It was in the LAKE CHAMPLAIN. I had just gotten the officer from the LAKE CHAMPLAIN. He was one of their officers of the deck. He had forgotten that all the ships were doing twenty knots. He thought that the carrier was doing fifteen and he had enough room to get over it. It was one of those things that makes your back scar.

Morgan J. Barclay:

There's always a chance of human error, isn't there?

William D. Owen:

Yes. That's why a captain always has to be on the bridge or sleeping up close to the action. You can't be back at the movies or sleeping in your in-port cabin.

[End of Interview]