| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

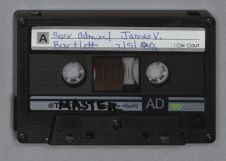

| Rear Admiral James V. Bartlett | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| February 5, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Morgan J. Barclay:

I see here from the information that I was able to gather that you were born in West Virginia.

James V. Bartlett:

I was born in Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you spend most of your childhood there?

James V. Bartlett:

I stayed in Point Pleasant while I was an infant and then I moved to another little town, Spencer, West Virginia. When I was school age, I moved to Charleston, West Virginia, and stayed there through public school.

Morgan J. Barclay:

After you finished public schools, what prompted you to apply for the Academy?

James V. Bartlett:

It's been a long time, and the things that prompted me are things that are hard to sort out right now. My interest in the Navy actually went back to a very close cousin of mine who was about a generation older than I. He had enlisted in the Navy just before World War I. He had made a career in the submarines, retiring in the thirties as a chief torpedoman.

Morgan J. Barclay:

He was in early on.

James V. Bartlett:

Yes. He was one of my boyhood idols. I think the fact that he was someone I knew--a real person in the Navy that I liked and respected--had a great deal of influence on my interest in the Navy. When I was probably four or five years old, he outfitted me with a

tailored set of blues that were just like his, complete with his World War I ribbons and everything. I wore that uniform until it was threadbare with, I guess, as much pride as I later did my own.

At the time that I went to the Naval Academy, I still wanted to pursue some kind of technical education in engineering or technical things. I had another friend (Class of 1932) who had gone to the Naval Academy. Again, he was older, but I knew him quite well and admired him and I listened intently as he told me stories, not only about the Navy, but about the Naval Academy. I became interested in it and decided that I would like to try to get in. Really, that's what triggered the whole episode.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Once you arrived at the Academy, could you describe your reaction to it and some of your experiences from those days?

James V. Bartlett:

Let's go back for a minute. I graduated from high school in 1935. I had been told that the entrance examinations to the Academy were tough. You only had one chance to get in and you'd better make good on it; so, I elected to go to a prep school for a year after high school. I enrolled in a school in Washington D.C., called Randles School. A number of my classmates went there. It started in September and ran until time for the entrance exams, which occurred in, as I recall, early April. Taking that course was the right decision; I didn't realize how dumb I was until I went to Randles and found out.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was that school geared toward people who wanted to go to the Naval Academy?

James V. Bartlett:

All it did was prepare students for the entrance examination for the Naval Academy. I had an alternate's appointment. Do you understand the concept of principals and alternates with respect to appointments to the Naval Academy?

Morgan J. Barclay:

Yes, I just got educated in my last interview.

James V. Bartlett:

Each congressman could appoint one principal and three alternates. Each of the four

was entitled to take the academic entrance exam. If all passed, the first opportunity to go for the physical exam (the last hurdle before admission) went to the principal. If he passed, that was it. The other three were out. If the principal failed, then the first alternate had the next opportunity, and so on.

I had the second alternate appointment. I took and passed the examination, but the principal appointee also passed the examination. He was admitted to the Academy that summer of 1936. All I had for my effort was having passed the entrance examination. I still had one year of eligibility, before I would be over-age. Having passed the academic exam, I didn't have to take it again. I went to work for DuPont in a factory near Charleston, West Virginia. I worked there for a year. During that year, I did everything I could to get a principal appointment, because that was what I needed to get in. Well, I finally got the appointment but it was primarily because the principal who had been admitted the year before flunked out in February. The congressman who appointed me had his new appointment plus the one made available by this first guy flunking out. I was admitted to the Academy in the summer of 1937, which was the Class of 1941. I passed the physical and embarked on, what I thought was going to be, an uninterrupted Naval career.

There was an interesting twist to our class, with respect to the physical exam. There had been a history of a lot of failures on subsequent annual physicals due to what they termed "defective vision" or bad eyes. In those days, the medical requirement was that midshipmen be able to read the 20/20 line without glasses. The Bureau of Navigation, which was running the personnel business in those days, together with the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery decided that they would institute a more rigorous entrance examination with respect to one's vision, theoretically, effecting a weeding out of all potential eye “unsats” early on. They did that the year I entered the Academy. The eye

examination was so rigorous the summer I entered that the Academy had great difficulty reaching its nominal quota for our class. The record will show, for example, that we were one of the smallest classes to enter and to graduate during that period of time. In my judgment, although I've never seen it officially recorded, it was attributable to the super-rigorous eye examination. It was so bad that some of those who were rejected early in the summer, were later recalled for a further examination and assessment, and then let in. I tell you this story because it turned out to be significant for about twenty-two or twenty-three of us later on.

Despite the fact that all of us who got in that summer had visual acuity that matched anything they could throw at us, a little over two years later, I was having great difficulty passing the eye exam. My third year, I even took part of my Christmas leave and went to an eye specialist in New York City to have him give me exercises to see if I could, somehow or other, pass the eye exam. As it turned out, even that failed for me and almost a couple dozen others. The result was that when our final physical came first class year (as you know we graduated early), I couldn't pass the eye exam. I could not read 20/20 without glasses. I was allowed to graduate and they kept me around four months and gave me a reexam, but I still couldn't read 20/20. So, I was honorably discharged. I became a civilian. The discharge papers read that it was because of defective vision. Presumably, that was the end of my career in the Navy. Later on, however, it picked up on another avenue. If you want to pause now and ask me anything else about the Academy, we may as well do it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I would be interested in your reaction to classes, instructors, Naval life, and the regimentation. I see that you were involved with the Lucky Bag working as a photographer. Maybe you could just describe your experiences.

James V. Bartlett:

I think this is significant as far as the philosophy of effort is concerned. In my last

couple of years in high school, I had made reasonable grades, but certainly not anything outstanding. I certainly didn't apply myself. I probably raised more hell and had more fun than I should have. Maybe I did no more than many of my contemporaries, but I didn't apply myself too well. I was really not prepared for a rigorous academic regime. Looking back on it, it was an important thing that I failed to get in the year I passed the exams. I went to work in a factory, doing menial and tough work, and I didn't like it. I didn't like that kind of life and I didn't want to keep doing that.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It gave you some motivation!

James V. Bartlett:

It gave me enormous motivation. I said to myself more than once that if I could get into the Academy, I would fight tooth and nail to stay there. I would not jeopardize in any way my opportunity to finish and do everything that was available to me to do. I'm not sure I would have done that had I not been burned by this failure. The failure was something I didn't want to repeat.

The result was that I approached my whole time at the Naval Academy as though it were one in which I was on trial. Every minute counted and I couldn't afford to let anything go by the board. I couldn't slough off, goof off, or miss it, because I would be right back where I didn't want to be. That might have been a negative kind of incentive but it was pretty real.

My first order of concern was to be able to pass academically. That was number one and I had to do everything that appeared to me to be either necessary or expected. I wanted to succeed at being a midshipman. I wanted to succeed in getting through and doing what I set out to do. The extracurricular things I took part in--and I did quite a bit of that--were definitely a secondary effort. I had drawn cartoons in high school for the newspaper. In prep school, I had done the same kind of thing. It was a hobby. I liked to do it and as a

result I did sign up for the Art Club, The Log, the monthly magazine we put out, and the Lucky Bag, which was our annual. I was also an avid photographer, having started that as a hobby at the age of twelve or thirteen. I was not an athlete. Right now I weigh probably a hundred sixty-some pounds. At that time, I weighted a hundred twenty-five. I was probably as tall then as I am now, maybe taller! I was not a physical type except for intramurals. I was not a candidate for athletic programs. In the theatricals, I was in the make-up crew. I provided the make-up for the productions. I was also in the boat club because I liked to sail. That was about the extent of the extracurricular things I did while I was here. I enjoyed all of it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You came away with a very positive experience at the Academy.

James V. Bartlett:

Very much so. That had to be the most concentrated, saturated, emotional experience that I have had in my whole life.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Your desire to succeed along with the discipline was a good combination.

James V. Bartlett:

Oh, yes. I think, like a lot of us, we had apprehensions rooted in the unknown, primarily. We knew that plebe year was supposedly tough. Looking back on it, it was nothing. Even at the time, I found it to be a very interesting experience. I liked plebe year very much.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Not everyone says that.

James V. Bartlett:

I liked plebe year because it was an opportunity to see whether or not you could do everything they demanded of you. If you could, you could say, "What's next?" For example, after dinner at night, one could go to Smoke Park in back of the mess hall. In Smoke Park there was every opportunity in the world to be hazed or "run" by the upper class. But you didn't have to go out there; you went there by choice. There were other places, too, where you could open yourself to that. I didn't seek it all the time, but I didn't

avoid it either. As a matter of fact, I rather enjoyed the fun and games that that sort of thing brought about. I tried to be careful enough not to get hurt. I liked plebe year. I thought it was a very interesting thing and I had no problem with the concept of hazing as it was practiced while we were there. It could be unpleasant or miserable but if you didn't want to be subjected to it, there were good methods for avoiding it. In effect, you had an opportunity to take about as much of it as you wanted to and avoid the rest of it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That's interesting. What courses did you enjoy the most while you were at the Academy?

James V. Bartlett:

I like math and science. As you may be aware, at the time the Class of 1941 went through, there were very few options. You could choose your language and that was it. That was the only option you had. Today there are several major electives. In those days everybody took the same thing, except for the language. I liked the language course. I had taken Spanish in high school and I wasn't about to burden myself with anything new if I could help it, so I continued to take Spanish while I was at the Academy. I enjoyed that course very much. I obviously got along better having had it two years before I got there. I liked all the engineering courses, particularly marine engineering. As a corollary to that, I least liked social studies, the humanities, English, and history, which came back later to haunt me. Nevertheless, I took less pleasure in those than in the technical studies. I liked ordnance very much. That was probably my favorite subject.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Those technical skills that you were interested in certainly paid off later on.

James V. Bartlett:

Yes, they did. Ultimately, that became my life as a working engineer.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Let's backtrack a bit. It's 1941, you thought the Navy was going to be your career but your eyes kept you out. What was the next step?

James V. Bartlett:

In June, 1941, I was discharged. I was completely severed from the Naval service

with an honorable discharge. I was offered a job as an instructor at Randles, the prep school I had attended. I mentioned that some things come back to haunt you. When I asked the man interviewing me what he wanted me to teach, he said, "American history."

I said, "You realize that was one of my worst subjects."

He said, "Nevertheless, we don't have anyone to teach it so you're going to. And, you're going to tutor math, algebra, geometry, physics, and so on."

I said, "All right. That's fine. I'll do that."

So I went to work at Randles School in Washington as an instructor. The new class coming in would be the USNA Class of 1946 graduating in 1945. In that same year, our war started. The guy who owned the school was also an instructor. He had three faculty members. One was Ed Harrison (Class of 1939) who also flunked out because of his eyes. Incidentally, he later became the president of Georgia Tech. There was also a fellow named Bob Brandriff, a civilian from Harvard, who taught English. I was the third one.

When the war started, Ed Harrison and I, the other Naval Academy graduate, got together and said, "Look, we both flunked out on our physical, but maybe they have some new rules now. Let's go down and see if we can sign up and get a commission in the Reserve."

We went down to the O.N.O.P., the Office of Naval Officer Procurement in Washington. We asked them if we could apply for a commission as ensigns in the Naval Reserve. I'll never forget what the lieutenant commander who was in charge of the office said, "What qualifications do you have?"

We said, "We're both recent graduates of the Naval Academy."

His response was, "I'd rather have a college man."

We looked at each other and said, "Well, that's about all we have to offer as far as

qualifications to be a Naval officer is concerned! Can we fill out some papers or something?"

He said, "Here, you can fill these out."

We filled out the applications and went on back to school. In due course, we were called for an interview. During the course of the interview we explained to them the reasons for our discharge as being for physical disability.

They said, "Well, we have the same kind of rules. You have to be able to read twenty-twenty to get a commission in line."

It had been just a few months since we had been discharged. The wheels of bureaucracy hadn't turned fast enough.

They said, "We have some programs in which we need instructors and we can give you a waiver for your eyes for those programs."

We said, "Fine, whatever you have. What is it?"

They said, "Well, we have these schools that we've established." They turned out to be those "ninety-day wonder" courses.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was it O.C.S.?

James V. Bartlett:

Well, not quite O.C.S. They had various names for them like V-7, V-5, etc. There were a lot of them. I can't remember the designations now.

They said, "We need instructors for those programs. We could use you for that limited duty."

We said, "Fine, whatever."

They said, "Okay, we'll process your papers."

All that took time. There were all kinds of delays. The paperwork in those days moved slower than anything else. They finally called us in June 1943 and said, "Okay, we'll

commission you."

Ed was commissioned a jg and I was commissioned an ensign. As I recall, I was ensign DVS, deck volunteer specialist, USNR. Our assignment was to the school at Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire. I had to buy new uniforms since all I had previously, I had gotten rid of the year before. I packed and moved to Hanover. The school turned out a thousand officers every couple of months. I was there for a year.

Toward the end of the year, an "ALNAV" (a Navy bulletin) came out. It announced that applications were being received for the annual input to the Civil Engineer Corps course at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. All those who wanted to become a member of the Naval Civil Engineer Corps, a three-or four-year program, should apply. If they were selected, they would be sent to RPI for a course in civil engineering, after which they would be transferred from line to the Civil Engineer Corps. This program had been going on since the turn of the century. Each year they transferred two, three, or four officers out of the line of the Navy to the Civil Engineer Corps of the Navy, where they then spent their career.

When the "ALNAV" came out, it said something to the effect that they were receiving applications that year from the Naval Academy classes of 1940 and 1941, that they would select three people from these classes of the regular Navy and that they would give preference to those officers who, because of impaired vision, found their careers in the line to be in jeopardy. Somehow or other, that expression caught my attention. I was a member of the Class of 1941 and my career not only in the line but in the entire Navy was not just in jeopardy but terminated because of my impaired vision. I thought, "This is a natural except for one thing; I'm not in the regular Navy. What the hell, I'll give it a whirl anyhow."

I wrote a letter and an application explaining all this and sent it in. I had a friend who

had a friend who was an admiral in Washington. I asked him if he would see if he could help me get my application considered; that is, to prevent my application from being thrown out on the technicality that I was not in the regular Navy. The only qualification I didn't have was being in the regular Navy. It worked. They added one more space. They didn't cut anybody out. They still took three Regulars, but they added one more from the Reserves and I got in. I took the course. When I finished the course, I was transferred from the line U.S.N.R. to the Civil Engineer Corps, U. S. Navy.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long was the course?

James V. Bartlett:

The RPI course was two calendar years. I don't know what you folks at East Carolina University regard as a work load, but we never had less than twenty-five contact hours. One semester, we had thirty-eight contact hours, not counting lab work or thesis or anything of that sort. We went six days a week, from eight in the morning until dinner time, for two calendar years. We went in as juniors. We did junior and senior work in a calendar year and got our bachelor's degree in civil engineering; then we did one year of post graduate and got a master's degree in civil engineering. Of course, we already had a bachelor of science degree, so we had the fundamentals; however, we took a whale of a lot of hours. Some of those courses that we took were with undergraduates, but most were taken by only the four of us. Everything was concentrated. I think that's the way to go to school. I was married and had two kids. It wasn't as though I didn't have any other responsibilities. It was great.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was it tough on the family?

James V. Bartlett:

It really wasn't. Looking back on it, nobody knew any different. It was pretty good.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Does Dad really live here?

James V. Bartlett:

Well, they weren't old enough to know whether I was there or not. Anyhow, I thought it was tough at the time, but looking back on it, everything went all right.

Everything proceeded rather normally. The main thing was that we were all in the same boat together. We had the same amount of homework and the same courses to take and all that sort of thing. The Navy assigned the courses. We weren't taking regular courses. We were taking all kinds of extra things that were required by the Civil Engineer Corps of the Navy for its officers. That was a real fine experience and I enjoyed it. It was great.

Once that was finished, I was launched. I was in the regular Navy from then on; albeit, rank-wise, I was considerably behind my class. I think they were full commanders when I was still a lieutenant. That was neither here nor there either, because I was established back into the regular Navy. I had just as much opportunity at that time as anybody else and I was very grateful.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Where did you end up on your first assignment out of engineering?

James V. Bartlett:

The war was just about over and we were going to go out and be part of the big invasion of Japan. We never made it, because the war was over before we could get there. We were going out with the Seabees. I ended up with an advance base construction depot at Iroquois Point, Oahu.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Just for my own information, because I'm not familiar with engineering, what type of projects would Navy engineers be getting into?

James V. Bartlett:

Let me help you a little bit on Navy engineers. There are all kinds of Navy engineers; however, there is only one staff corps of engineers. Those are the civil engineers. They can be identified by a different insignia on their sleeves. Instead of having a star, they have crossed live oak leaves, which is the emblem of the corps. There are EDO (engineering duty only) officers. They wear stars. They're basically originally of the line, but have been designated for engineering duty only. There are AEDOS (aeronautical engineering duty only) officers. There used to be a construction corps which had to do with shipbuilding.

When I was on active duty, there were engineering officers who had shipboard engineering duty; there were aeronautical engineering duty only officers who had duties relating to aeronautical engineering; and there were Civil Engineer Corps officers. The Civil Engineer Corps is a staff corps of the Navy like the Medical Corps, Dental Corps, and Supply Corps. These are all separate staff corps of the Navy.

The Civil Engineer Corps of the Navy originated in the late nineteenth century. For years, Navy civil engineers didn't even have the rank of officers. They did have, however, equivalent rank, but to distinguish them from regular naval officers, their uniforms displayed pale blue stripes between the gold ones designating rank. Sometime around the turn of the century, the officers of the Civil Engineer Corps were made officers of the Navy with full rank and status. It's been that way ever since. There was a time, however, when officers of the Civil Engineer Corps were never in command of anything. They might have been an officer-in-charge of something, but they were never in command. World War II led to a significant change in all that. It was primarily due to the efforts of Admiral Ben Moreell, founder of the SEABEES. He was the wartime chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, which was the mother bureau, if you will, for the Civil Engineer Corps officers and the Civil Engineer Corps organization. Now it's called the Naval Facilities Engineering Command. The Civil Engineer Corps of the Navy, historically, has been the group that has provided for the design, construction, and maintenance of the Navy's shore establishment.

Morgan J. Barclay:

They have always made sure things were done right.

James V. Bartlett:

That's right. It's as if you have a building to build and you hire an architect to design the building and then manage the construction contract: take bids, award the contract, and make sure it's built according to the plans and specs, and then maintain it.

When World War II approached for us, we had many civilian contractors working

primarily throughout WestPac, the Pacific Ocean area, building bases. When the war started, these contractors were in a very vulnerable position because they were not in the military. Therefore, under the rules of international law, they were unable to defend themselves with arms. They were subject to internment if they were overrun; and if they fought back, they were subject to summary death. As a result, an idea was formulated of taking all these guys, putting them in uniform, and making them part of the military establishment. This is not directly what was done, but it is essentially what was done. These people were given the opportunity to enlist or to be commissioned--depending on their function, their skills, and their background--into a military organization. They were called Seabees and were organized into construction battalions. There were hundreds of thousands of Seabees during World War II.

Following the war, they all began to go back to industry where the money was, leaving just a nucleus remaining in the Fleet.

A lot of my early days in the Civil Engineer Corps were devoted in Washington to the perpetuation of the Seabee organization. I worked on programs that would keep it alive.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You had a lot of competition from private enterprises?

James V. Bartlett:

The Navy didn't have a need for them anymore, so our whole effort then was to try to keep a nucleus aboard so that the next time something came around, we wouldn't have to start from square one. I guess the period of 1949 to 1952 was a low point. We almost got completely out of business. They kept only a couple of battalions in each Fleet.

I was on duty in Washington at this time, working on programs in the Bureau of Naval Personnel to, in effect, create our own supply of Seabees. Before, we had taken construction workers and enlisted them directly. They already had their skills. They were carpenters, steel workers, equipment operators, mechanics, and so on. But you can't just go

out and get those people when they're making big wages. Consequently, we developed a program in which we would take young high school graduates and say, "Look, you want to be a construction person, come join with us and we will teach you a construction trade." We set up schools, principally in Port Hueneme, California, in which we gave them basic training in all the construction trades. In effect, we "grew our own." It worked with particular effectiveness during times when the draft was operational. It took a while, but in due course, we had experienced, seasoned journeymen in those trades. Once we reached that point, it was just a question of putting them in at the bottom and retiring them at the top. That's where we are today.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Would they stay their whole career?

James V. Bartlett:

They were like anybody else. Our re-enlistment rate was competitive with any other part of the Navy. We always held our own despite the attractive, lucrative opportunities that were available outside. We had lots of incentives for people to come, not the least of which was training and useful work. Now, we had trouble with the unions, originally. They didn't want any military people working on construction jobs that would compete with them. For years, the only productive work, construction-wise, that the Seabees could do was overseas. You had to be overseas.

I was fortunate enough in 1953 to get a job as commanding officer of a Seabee battalion, Mobile Construction Battalion #4. It was an interesting thing. It was a commander's billet, but I was a lieutenant commander. It turns out that nobody wanted that job. The reason nobody wanted it was because of the occasions following World War II in which commanders assigned those jobs were frequently passed over late for captain. The presumption was that if you became a Seabee skipper, you would never make captain. Consequently, a lot of people didn't want it. There is another body of evidence that

indicates that maybe the people they assigned to those jobs wouldn't have made captain anyway. Who knows?

Morgan J. Barclay:

You took that risk?

James V. Bartlett:

I took the risk because I wanted the job. I thought it was the equivalent of being skipper of a destroyer or a squadron of airplanes. I had a thousand men. My first deployment, two weeks after I took command, put us on a LST and took us to French Morocco. That's where we had to do our work, some place like that. We had to go to Port Lyautey; or Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; or Subic Bay; or Guam; or Adak; or Argentia--places outside the continental U. S. I was delighted to have that opportunity to be in command of a Navy unit. The fact that I was a lieutenant commander simply meant that I had an opportunity that nobody else wanted. I got it in sort of a vacuum, but it was a wonderful experience. I took the battalion twice to Port Lyautey, and once to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. I got really fired up on the Seabee business with that assignment. I had other CEC duties, but I think in the thirty-some years that I spent on active duty, I would regard the duty I had with the troops in the field as by far the most enjoyable. It was glorious. It was great.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You would take them to a specific site and work on a specific construction project?

James V. Bartlett:

Projects. We would have a program of things to do. It might be an airfield, a hospital, houses--we were building a lot of family houses in those days. These were all unaccompanied tours. We just took the troops out in the field, fixed ourselves a camp, lived and worked there, and then came back.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were some of these stays?

James V. Bartlett:

Each stay was no more than eight months. We would be gone eight months and then we would go back to home port. My home port was in Davisville, Rhode Island. I would bring the battalion back to home port and we would have two months at home base in

which we could take leave and then we would train. For example, we came back from Port Lyautey and found that our next assignment was going to be in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. We were going to be building a lot of houses down there out of concrete block, with tile bathrooms and plastered ceilings. We didn't have many people in the battalion that could lay-up ceramic tile. They could lay-up blocks, but they didn't know how to lay ceramic tile. They also had to learn how to plaster ceilings. We set up mock rooms, just like the ones we were going to build. We would go down there all day long and put ceramic tile on the walls of the bathroom. Then, before it hardened, we would wash it all off and start over again the next day.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were training for what you were going to be doing.

James V. Bartlett:

Exactly. We trained when we were in port. While we were in port, the men got to see their families or go on liberty. Then we would be put back on a ship and sent someplace else. These days they fly, but in those days we went on LSTs or a transport. To this day, to my knowledge, all Seabee construction is still outside the continental U.S. Seabees are like ships; they are always deployed overseas someplace.

In between Seabee assignments, I was involved in the usual contract work and so-called public works, which was building, maintaining, and operating the physical plants that the Navy has onshore. One job, for example, was to build a new air station to serve a category of aircraft and associated operations that could not be accommodated at any existing air station. The naval aviation community provided the requirements and criteria to be met. The site selected was Lemoore, California. BuDocks (now NavFac) engaged engineers and architects to prepare plans and specs; took bids for construction; awarded and then managed the contracts through completion of the project. When completed, the station complement included CEC officers whose public works department provided for the

maintenance of the station and the operation of its utilities and transportation.

My duties were always in the area of engineering and construction, not of ships, but of physical plants--a shipyard, an airfield, a hospital, a training station, a supply depot, an ammunition depot, a housing development--anything that the Navy or the Marine Corps wanted built. I was stationed several times with the Marines. Once I was in Beaufort, South Carolina, at the Naval hospital, which serves the Marines at Parris Island. I was the resident officer-in-charge of construction and, later, the public works officer there. I was also the public works officer and officer-in-charge of construction at the Marine Corps schools in Quantico, Virginia. I was there for three years. We built all kinds of things, from a reservoir to a medical clinic to roads and bridges.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Are there any special frustrations having to deal with civilian contractors?

James V. Bartlett:

No. That's always been a pleasure. There was always a scare tactic used by some: "Oh, you're going to have a terrible time dealing with the contractor." I never had any problems at all dealing with the contractors. We always got along fine because, if they did what they were supposed to, they made money. If they didn't do what they were supposed to do, they lost money . . . or didn't make as much as they could have. If they did what the contract called for, we got what we paid for, it worked, and everything was good. If they didn't, we struggled with it all the time. I never had any trouble with that at all. If I had problems, it was the more senior I got, the more I had to work in Washington. That was an absolute, utter frustration.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Dealing with the large bureaucracy?

James V. Bartlett:

Just the whole Washington scene to me. There were some fascinating aspects to it, but when you got right down to the nitty-gritty, it was the most wheel-spinning, useless, frustrating, head-banging experience I ever had. I retired as Deputy Commander of the

Naval Facilities Engineering Command in Washington. I was frankly relieved when my total time was up. I was ready to go. Incidentally, I went out into industry and worked for ten years with an engineering construction company, selling what I used to be buying. I enjoyed every bit of that, too. In those days, I couldn't deal with the Navy because they had rules against that, which I understand, they are about to change. I could not have any active dealings with the military in terms of selling, which was all right, I guess.

The best experience I had altogether was my last field tour, in Vietnam. I had been commanding officer of the Chesapeake Division of the Naval Facilities Engineering Command. The division is in Washington but it's really a field office headquarters. I was in charge of construction in the Washington, D.C., area, which includes Quantico, Patuxent River, Annapolis, and all the Washington area stations. I was in that job when I was selected to flag rank. One of the things that went with the selection to flag rank in those days was a tour of duty in Vietnam. As a matter of fact, in the Civil Engineer Corps, we only had two kinds of officers, those who had been to Vietnam and those who were going. Sooner or later, everybody had to go. I regard that as probably my best experience.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What kind of projects did you work on over there?

James V. Bartlett:

We had many things. I was the commander of the Third Seabee Brigade. We were headquartered in Danang. I reported to the Commander of Naval Forces in Saigon, but I was under the operational control of the commander of the Third Marine Amphibious Force, General Cushman. He had command of all units in the I Corps. He had operational command of the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, . . .everybody. I was there from August of 1967 to March of 1969, which was the height of the operation. We had a total of a little over ten thousand Seabees. At one time we had twelve battalions there. We built everything you could think of: barracks, roads, ammunition supply points, airfields,

hospitals, piers, wharves, and bunkers. We even built a milk and ice cream plant.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Because of the nature of the conflict, you could come under fire, couldn't you?

James V. Bartlett:

Yes. Also, Vietnam was the most "social" war in history. We had more visitors than you can shake a stick at. There were congressmen, writers, photographers, and entertainers coming at you all the time.

We built many, many bridges. There was a particular bridge on Highway One, just north of Hai Van pass and Danang, which I guess we built a dozen times. The VC (Viet Cong) would blow it up at night and we would build it back the next day. Someone asked me, "Don't the guys get discouraged? You no more than get this bridge built than the VC blow it up again."

I said, "No, as a matter of fact we enjoy it the second time as much as the first time. We like to build bridges. The fact that it's the same river, that it's going across the same stream, is no detraction at all. It's fun. We like to build bridges." We did. We built a lot of them. As a matter of fact, a lot of our bridges were small bridges, no wider than this room. The water was deep so you had to have a bridge, but you could span it with concrete beams. We would pre-cast all these parts in the safety of our camp. We would have them all ready to go, big stacks of them. When one of the bridges was out, we would find out what size it was and load these parts on a low-boy. We had a whole convoy with everything we needed to build that whole bridge. We would take off, go down there, and put the bridge in--like "Lincoln logs." We would put it in and turn around and come back. Of course, we knew it wouldn't last; it might get blown the next night or in a week or month. But it served the purpose and we could do it quickly. Really, that was a fascinating time. It was grim, as it is anytime you're engaged in the kind of thing where people get killed; but as far as assignments are concerned, I regarded that as the highlight of my thirty years of being in the

Navy.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You've seen a lot of changes in your career in engineering. What were some of them? There have been a lot of technical innovations, I would think.

James V. Bartlett:

You would be surprised. Progress in the field of civil engineering, in terms of innovative new things, looks like a tortoise in terms of the race now being led by, say, electronics. It's like the jet plane. Civil engineering by comparison is more like the tortoise. I'm not too sure why. Maybe it's because there's some rigor mortis or that it's so fundamental.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Maybe some of the principles just don't change.

James V. Bartlett:

I'll tell you what has changed: those things involving the electronic aspects of it--computer-aided design and manufacturing, all of the technical aspects. I worked with Raymond International, which owned Kaiser Engineers out of San Francisco, and we designed a lot of process plants, steel mills, cement plants, and things like that. Kaiser used computer-aided techniques regularly. I would say that the biggest innovations have come through the use of the computer for computations.

In terms of concepts, the Germans introduced thin-walled sections of concrete, for example. In any place where raw materials like concrete and steel are in short supply and very expensive, there tends to be an incentive for creating designs that work those materials to their absolute limit while still being safe. We always have had plenty of such raw materials.

Our solution was always just to make it bigger. It's cheap. Make it big and it won't fail. Instead of taking a sophisticated design and putting it in a wind tunnel or some other nondestructive method of testing, we simply made it bigger. We did that with barracks. We used to design barracks to be people-proof. By the mid-sixties, we were making

barracks like prisons. The doors had to be steel clad and big because the guys would break them down. They were rough. They were kids, eighteen, nineteen, twenty-year-old kids.

I made a contribution to the system when I was commanding officer in the Chesapeake division. I noted that it was costing us considerable more per square foot to house a bachelor enlisted man than it was a married man. It didn't make sense. I'm not talking about what kind of house he had. I'm just saying, per square foot allocated to him, it costs considerably more to buy that one square foot for the bachelor enlisted man than it did the married enlisted man. I asked, "Why?" After a long hard look, it became obvious that it was because the bachelor enlisted man in a barracks tended to tear them up. So we built them stronger. This increased strengthening was cumulative. We finally convinced people, however, that it was cheaper to write an order that said, "Don't tear it up!" than it was to build it bigger.

What we did was to go back to using, basically, the same construction standards to build the barracks that we would use to build a house. My first suggestion was, "Why not build a house like the one we would build for a family? We can put two guys to a room. It would be less expensive than anything we're doing now."

Morgan J. Barclay:

They'd probably be happier with houses.

James V. Bartlett:

The end result is that now we have barracks that are built in modules with a living room with four bedrooms around it. It's a unit. They're far cheaper and it's far better. That's really no big innovation, however, and we're still using the same materials. To answer your basic question, there have been no revolutionary changes in civil engineering as there have been in even mechanical engineering.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was the Engineer Corps also responsible for repairs? They did some pretty miraculous things from the photographs I've seen, particularly from World War II, where

they would take the front end of one ship and the back end of another and build a ship that could go out again. The Navy was so decimated after Pearl Harbor.

James V. Bartlett:

Don't confuse shipbuilding with the shore facilities, but your comment is still pertinent and valid. The Naval Facilities Engineering Command is responsible for designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating the physical plants (such as power plants); the utilities; the streets, roads, and walks; buildings; and so on. That's still done largely in the U.S. by civilian workers but supervised and directed by officers of the Civil Engineer Corps. Seabees still do the kind of thing you're talking about--the innovative, creative things. When you are out in the field, you don't have a local Ace Hardware to go to and buy something. You have to make it. This has been the hallmark of the Seabees since they were created. They can do damn near anything if given half a chance. They're still doing that kind of thing. That's what made it fun. I really enjoyed my thirty years, every bit of it! I wouldn't have swapped it for anything.

In the Class of 1941, there were only five of us in the Civil Engineer Corps. There were four of us who went through RPI at the same time and one who came later. The four who went through when I did were, Mac McLellon, Bob Thomas, and Tommy Cocke. In the next RPI class, but still in the Class of 1941, was Chuck Merdinger. There were five of us altogether who ended up with careers in the Civil Engineer Corps. Five out of a class of 399 went into the Civil Engineer Corps.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It was kind of a speciality.

James V. Bartlett:

Yes. We probably have more in the Supply Corps. We have some EDOs and some AEDOs. There may have been some other specialities, but essentially, I think, those are the ones you've encountered. The rest of them, I guess, were all line, some black shoe and some aviators. Essentially, that's it. We had a good class.

[End of Interview]