| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #168 | |

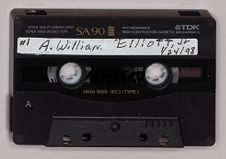

| Captain William E. Elliott, Jr. | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| January 24, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

O.k., Captain Elliott if you would begin with your years before the Naval Academy. You were born in 1918.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

About ten days before eighty, I'll be eighty the third of February.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's right.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

If I make it, but that's ten days.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will give us what you care to about your background. You said your family was from South Carolina and you were visiting in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, at the time you were born.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

That is where that happened. That was my mother's family joke, too. My mother and my father were separated when I was pretty young, probably five or six, but I asked her later on, “If I was raised in Florence, South Carolina, why was I born in Rocky Mount?” And she said, “Oh, Billy, I don't know; you were off traveling with your Aunt Nona at the time,” you know, which really puzzled me when later I discovered Aunt Nona was a maiden lady. So, that was two problems to try to figure out. Why was I off traveling with Aunt Nona when I was born?

But I was raised in a small town in South Carolina, Florence, which is a good break for anybody. I went to high school there and enjoyed a great life. I was raised primarily by my father and his mother, my grandmother. I went to the Citadel for two years. I had always wanted to go to the Naval Academy. The first thesis I wrote as a junior in high school was about going to the Naval Academy and graduating and becoming a naval aviator. I don't know why, really.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was when you were still in public schools?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. I guess part of it was because a cousin of a young lady I was keeping company with, Dan Carrison, out of the Naval Academy Class of '39. I met him and it seemed like an interesting career, particularly on Christmas leave when he would show up in a handsome blue uniform at the dances in Florence, South Carolina. It seemed like a good idea.

It looked as if I was going to be too old in my second year at the Citadel to get in, but then I got a direct appointment from Senator Allard Gasque of my district. Unfortunately, a contemporary had died of peritonitis and left a vacancy. So, I went directly from the Citadel to the Naval Academy. Previously, two years before I had taken the examination, the competitive examination, and was offered an appointment to West Point. At that time I was a year into the Citadel and I wasn't interested in any more gray uniforms. So, I just waited it out. I went in directly, easiest entrance, they took my college grades and high school grades. No tests or anything, but I had done that, the competition test anyhow. So, that was very enjoyable.

The happiest days were when I had a four-man room for the last three years: Bailey Pride, Ray Penrod, and Dick Reed, the Virginia boy. Bailey Pride was our hero,

the great big guy from Madisonville, Kentucky, a wonderful guy and good athlete. He ended up being crew captain. So, we had some happy years. Unfortunately, Bailey was killed at Pearl. He was on the Oklahoma. Ray Penrod was the chief engineer of the Meredith and the Meredith was sunk off Guadalcanal in early '42. He didn't survive. Dick Reed, who was a good Virginia boy, didn't pass the eye exam on graduation and stayed in what we call the "Twenty-Three Club"--there were twenty-three of them. Later on they were commissioned in the Reserve, went to ship construction school and did a lot of salvage work. He did all the salvage work in Italy, in Naples Harbor, and stayed in the Navy and made captain. He died shortly after his retirement of multiple sclerosis.

Donald R. Lennon:

Having a background at the Citadel probably served you very well as far as the regimentation and the discipline of the Naval Academy, as well as academically.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes, I could keep step pretty well by that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think with some people the regimentation would be something of a shock if they were not from that kind of a background.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I think it was to a lot of people. It was a piece of cake for anybody who had been to military school. I had been through Rat Year which is pretty severe. That is a side issue. I talked to an old Citadel grad not too long ago and we laughed and compared notes about all the efforts and thought we had given to trying to smuggle a girl into the barracks; and then they would turn up with one three years ago, who was twenty-five pounds overweight and not very attractive. We would not have smuggled her in. You're right, that prepared you for the Navy. The plebe summer was pretty easy, the foot drill was great. The first expression of democracy I saw was when we were drilling out in the

field on a hot day. I was in the tall squad, and we had a democratic vote whether a boy from North Carolina, not me, another boy, who had been to Clemson for part of the time or Hoke Sisk who had been to Marion Institute, should be selected by the troops to be their leader. We selected Hoke because he was the tallest.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you said you were in the tall squad. Did they divide you by size?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

We went exactly by height all the way. That's where you started. Frank Price and I were talking about it last night, and he said, “ Well, I was down at the end.” He was a "sand blower" we called them.

Donald R. Lennon:

He and Ned Hines.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

And Mickey Weisner.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's right.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

They were all down there.

Donald R. Lennon:

He was probably the shortest one of all, wasn't he?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

School was pretty interesting you know. I was a little more grown up having had two years of college. Academics were not very difficult. I was interested in playing baseball and the gym team, not very good at them but I entered them. Unfortunately, I was on a plebe baseball team and injured an ankle and ended up in the dispensary for three weeks just prior to examinations. So, Bailey Pride, my roommate, had to work on me to be sure that I could keep my record up, because when you're a plebe if you fell below a certain standard, you could not go home for Christmas leave, you know. I think for the three weeks prior to Christmas break, I made something like a three nine five in math and most subjects I was concerned about.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know Admiral Price was one of those that had to stay over Christmas and retake exams because he was unsatisfactory in his plebe year in that first semester.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

My roommates saved me. We weren't as bold as they are today, I guess; when lights were out, lights went out. I would sometimes be educated in the dark or we would end up in the head. That was a good education place, they had lights in the head.

It was mostly with Bailey Pride. If I was having trouble with my math, we just kept working all the problems until I knew what I was going to face. But, that was a pretty happy year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do any sailing on the Chesapeake?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I was in the sailing club and we did some, but not a great deal. Even as a third year man, you were still a head cleaner more than anything else. You would do a little steering but not much, but that was very pleasant. I enjoyed the sailing. That was sort of novel to me, although I was raised not far from the beach in Florence.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, I was thinking you being from where you are there in the coastal area you would have access to the water as a youngster.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

You're right. That reminds me of the first summer vacation from the Citadel with two Clemson boys and a couple of civilians. We ran an ice truck at Myrtle Beach. That was really interesting because that was where the girls were. They would come down on a house party. I think Les Brown had his band there. Les Brown was still at the University of North Carolina. The music was good and the life was great, but the beach was wonderful. We would stay and dance until two o'clock and then we would have to load the ice truck by six-thirty or seven and get the ice out. That was a great education in itself. We made a lot of money, six dollars and fifty cents a week. I almost retired then.

You know they moved our graduation up about three months, and of course, the Academic Department didn't let up on us at all. We just had Christmas day off, no leave. On Saturdays, instead of drill, we went to school. Academic Department got it all. We graduated on the seventh of February. That was the first time--you probably picked it up in the history of this--that they sent so many of us to small ships and destroyers. The old practice was to send twenty or thirty ensigns to the battleships and ten to fifteen or twenty to cruisers. So, I was very fortunate to be sent to a destroyer in Pearl, the USS CASE, 370.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, your first assignment was to the CASE at Pearl?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

We were there that morning when the war started, aboard ship. I have a writeup here too that I have given some fellow over the years. Would it be best to insert that rather than go through it?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you may touch a couple of reminiscences that you have and I would like to have that also to go with it.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Some years ago some Frenchman wrote and asked about it. So I wrote it up and checked the records and they are pretty accurate. The humorous part was Chuck Fonrielle, who was on another ship in our division, and Walt Seedlock, who was on the SHAW, and I bought a car, a 1932 Chevrolet called Esmiralda. It great to have transportation from Pearl into Waikiki. We discovered that Esmiralda took almost a full turn of the wheel to get her to answer the helm, and that meant if we passed the Aloha Tower by one o'clock we could pretty well make the two o'clock launch, which was the last boat back to the ships out in West Loch. Nonetheless, we found we were missing the two o'clock boat, and we would have had to sit on the officers' dock until five when the

milk boat would take us out. So, we put our funds together one Saturday, went to the Chevrolet place, bought a steering column and worm gear and we were going to replace that in the Esmiralda in the officer's parking lot. So, we were all aboard ship, broke.

We were nested. There were four ships nested alongside the WHITNEY which was the mother ship. We had taken about five to eight days dismantling quite a bit of the machinery and the blowers. Work was being done on the electrical systems and we were getting all of our support from the WHITNEY, that is electrical and water and all those. We laughed about some of the things that came out of it. The ship alongside, between us and the WHITNEY, was the TUCKER, and I was talking to my grandchildren not long ago and I said, “The CASE was lying alongside the TUCKER.” That turned out to be my wife's name and I have been lying alongside the Tucker for the last twenty-six years.

Donald R. Lennon:

Talk about coincidence.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

But we had a busy day. I guess I was a second senior aboard. There was a lieutenant aboard and I was just an ensign. I was a fire control officer, assistant gunnery officer, and also the assistant engineering officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

The CASE did not take a hit did it?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

But there was nothing you could do in order to get the ship up and running.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

It took us until late into the afternoon to pull the ship together which I thought was remarkable. When we got under way we didn't have any forced draft air into the throttle room. The boiler rooms were operational but that meant that the throttle room temperature ranged somewhere between 130o to 150o. We could only take about thirty minutes watch standing, it was so hot. We rigged canvas to scoop air. There were lots of

things that you look back on as routine heroics, I felt, by the troops. On the ship, everybody went to do their job, and we have laughed about my first most heroic movement . . . down in the throttle room. The two chiefs were down below the grating trying to put a feed pump together, which was absolutely essential to us getting together. They were soaked with perspiration, soaked but working diligently, and I'm standing over them. I said to the chief, “Chief Brownie, Brownie what can I do to help you?” He said, “For God's sake Mr. Elliott, go get us some cigarettes.” So, I went up through the watertight doors. The guns were firing, the fifty calibers were making a hell of a racket. We were firing five-inch and fifty calibers. That was my first heroic effort to get cigarettes for the chief who was putting the ship back together.

Donald R. Lennon:

I reckon most of the naval personnel though were working automatically by just training.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Just what we normally took care of. As a matter of fact, when I would come up from the engine room I would observe people walking to the WHITNEY bringing back food, five-inch shells, which are pretty heavy, and boxes of flashlights, that was precious. They opened the stores for us and so we were doing pretty well. We were firing the guns in local control, as we didn't have any power.

Some years ago, maybe five or six, seven, I don't know, on an anniversary date of Pearl Harbor, my congressman in Washington invited me and his other so called Pearl Harbor survivors to a ceremony in the congressional offices, very nicely done. We got a little medalion, which one of the congressman insisted on calling a Congressional Medal. We knew it really wasn't a Congressional Medal but it was a nice citation. There were I

guess three or four of us with our families that got these citations. That was interesting that he had remembered it.

Before we left the big conference room where the people were and some of the survivors of the men who had been at Pearl were, I was given a note by a local TV announcer asking if I would say a few words. He had a few questions when we came out. I grabbed two of my classmates who were also there, and we stood and he asked questions, the usual questions: "What were your reactions?" . . . and so forth. We told him. "People were doing their job. It was very noisy on the ship with guns shooting. We were busy firing fifty calibers which make a lot of noise." Then he said, "I just want to verify that if you had any Blacks on the ship, they were not allowed to be involved at all." I took issue with that. I said, “That is absolutely not true, I don't know where you got your information.” The gun captain of our number three five-inch mount was our first class steward. He was a very popular, very unusual man. When we had guests aboard ship when we were in port, he wrote the menus in French. He put his sister through college. He was the gun captain. He ran that gun powerful. I can remember distinctly walking by him and seeing a line of young men, seventeen, eighteen years old, passing ammunition up. One of them was a white boy who really seemed to be overwhelmed by the noise and the confusion and I literally saw the first class stewart give him a boot in the bottom and get him back in action. I said, “I resent the fact that history is saying that Blacks were not permitted to be involved.” They definitely were on our ship. We didn't have many Blacks, as our stewards were mostly Guamanians. All of our stewards were from Guam. The first class was the only black, and maybe one other, but most of the time in the destroyers, the Guamanians and Filipinos were the stewards. But it was true

that they only had a rate as steward's mates. I didn't know if you would be interested in that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, that is very interesting.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

History was being distorted for some reason.

Donald R. Lennon:

It happens. It certainly can get distorted, particularly if someone has an ax to grind they are going to do just that. I reckon the SHAW was the only destroyer that took a major hit.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

It really did. It was in the floating dry dock. It made a spectacular photograph. I walked the dry dock with Walt. He was the duty officer that day. He lives out in California.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've talked with him. We did an interview with a good friend from the class of '35 who was standing underneath the SHAW when it got hit. He has really given us a great account of what was happening at the SHAW.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I tell you a quick one about the SHAW. The SHAW was in our division, and we were scheduled to go in the floating dry dock or along side in that area, which was great for us. That meant we could walk to the Officer's Club from the CASE. The SHAW was on offshore patrol on about the fifth or sixth of December, I guess, and they had a little mishap with the NEOSHO--they hit the oiler, and the SHAW was damaged. We resented the fact that they steamed past us and went into the floating dry dock, which meant they would be close to the club. We thought that was bad news until Pear Harbor day when we saw them go off. I went to see Walter in the hospital. He was in pretty good shape, he wasn't banged up. He had been immersed in the oil-covered water, because he and some of the other people were helping the sailors in the water to get them to the dock. He

said to me, “Bill, I darned near drowned. I was the duty officer. I had a belt with a forty-five and seven fifty binoculars on." You signed up for all those things. "I went over the side, I thought I was going to drown. Finally, I decided, well I could get rid of these things.” He was in the hospital bed and he said, “All I have left, no clothes or anything, is my class ring.” He survived very well.

The CASE escorted some of the ships. We really made our first run out of Pearl. There is a write-up in here that is interesting because we stayed inside Pearl, sort of as the anti-aircraft ship, all of the night of December the seventh, steaming slowly around Ford Island, with plenty of light. The ships were burning. There was a lot of light from Hickam Field, which was burning. I was on the mid-watch, up on the gun Mark 37 director. We were up fairly near the net to exit. We were looking to see if the submarines were there . . . we had been told that there were two small subs in there . . . when we saw a formation of airplanes with their navigational lights on. There were F4F's from the enterprise flying in. The SHAW 's guns were free, but the batteries opened up. Of the six airplanes, I think only one airplane made it down. That was Jim Daniels, whom I have known over the years; he is still alive in Hawaii. He managed to get in. The rest of them cut off their lights. Four of them were shot down as I recall. The fifth one was damaged but only two of the pilots survived. I am proud to say that I had our guns tight. I would not let out. It was obvious to me they were our planes, because about an hour before that we had helped a PBY find his way and we lighted a path with our searchlight for him to get in. There were airplanes, however, so, whoever was on the beach, the other ships were firing at them. Because we had been through both of the attacks, I guess truly we were a little trigger happy.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is only natural. Tragic for the crew of the planes, but it's not to be unexpected. Something like that can happen.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Jim Daniels has written up quite a bit about it. He had not elaborated on it. He had to identify himself by voice radio. Luckily, his air group commander was at Ford Island in the tower, and he identified himself by giving the middle name of the air group commander. So, he said, “That is one of my boys.” So, he landed. He survived all right, brought his plane down. The rest of them, it was sad. We didn't really know.

We pulled the ship together and while we still didn't have all of our parts installed, we steamed towards the mainland to pick up the SARATOGA to escort her out. We brought her back and did some routine patrolling around there. We stripped ship of course, took everything that was wooden off, the radio you had in your cabin and all that.

The next event for us was when we loaded about a half of the First Marine Raider Battalion, toughest looking Marines I've ever seen. They were led by a first lieutenant and warrant gunner. They slept on deck. We went to Midway, and that was about two days before the battle of Midway. We were taking reinforcements up there. They would take our coffee, but they provided their own food. So, when they left the ship I said to the gunny, the guys were all suited up with heavy packs and so forth, I said, “I guess you guys will be glad to get off this ship and get in the barracks and get some rest.” He said, “No, Mr. Elliott we are going to walk around this island as soon as we get to shore and then we will rest.” They were the toughest looking guys I've ever seen. When they left, they left at a trot. All of them went around the island.

So, we went on up and joined the task force for the Aleutians Campaign. Strangely enough, it wasn't until just recently here in Jacksonville that a friend gave me a

booklet on the Battle of Midway written from the Japanese viewpoint by the same commander who led the raid on Pearl Harbor, (................) and another one which was an eye opener for me. It was a very, very interesting book. It was published in 1953 by the Naval Institute. Boy, he called a spade a spade, and the mistakes the Japanese made you probably couldn't get away with. Interestingly enough we joined up with a pretty good size group of cruisers. We had a total of about eight first-line destroyers and then we had a division of old four stackers. We went to Dutch Harbor, and just barely managed to avoid getting bombed there, because the raid came over and the clouds obscured. But, as we moved away from the dock, the shore installations got bombed. Their oil dump got hit, so it allowed a big cloud of black smoke. By that time I was a JG and didn't know it. We missed the ALNAV that told us we were JG's, but another ship came alongside and I saw one of my classmates with a silver bar on him, which made him lieutenant junior grade. "Gosh, I guess, Steve, I missed the cut." "No," he said, “We all made it if you're still alive. We all made JG.” So, my fire control guys took my regular brass single bar and coated it with lead and made it silver so I was the JG the next day.

Donald R. Lennon:

None aboard ship you could borrow?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No, we weren't stored for that. Incidentally, the SHAW had all of our pay records on it. We only had one paymaster in the Division and he was on the SHAW, so all of our pay records were destroyed. So, we didn't have any money. Of course we didn't make any liberties. When we went into Dutch Harbor, I think we used our small recreation fund and gave everybody something like three to four maybe five dollars. That's all we had, we didn't have any pay.

Donald R. Lennon:

The weather was pretty bad out there during that time wasn't it?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Well, it was kind of a shock to us, since we left warm water around Pearl to go up there. We weren't equipped for it. We only had two heavy fleece lined jackets. So the watches that stood on fire control (we spent a lot of time at general quarters), we just passed those along. We were a little cold. It was cold and foggy. We made two official runs up there to Kiska to bomb it and were turned back. We got up there the third time. The third time we did bombard, but by that time the Japanese were gone. That was an interesting deal. We had one airplane make a run on us. I was the fire control officer and we opened fired on it. Our official log shows we thought we damaged it. It was a Zero with floats, and he did drop a bomb of some sort. Not very close to us. But later on having been an aviator, I decided that the smoke we saw coming out of him was when he just advanced a throttle fully to get out of there, because we were putting some bursts right around him. He didn't hit us. We got credit for sinking a tanker. An auxiliary Japanese tanker. The big thing though, in this book that I discovered gave the details. I did not realize that the Japanese had two carriers in the Aleutians, five cruisers, twelve destroyers, and two submarines. They had a good size force. That was not just diversionary. It was a good size force. Our four or five destroyers fled. We fled Dutch Harbor and went around to a small island on the north side called Unalaska. We were sort of trying to hide there. We didn't know what to expect. We knew they were around, but on our level we didn't know any more. This book has it in black and white though. The Japanese launched twenty-nine airplanes after these five destroyers they had spotted up there. The clouds saved us. The weather was too bad. They regrouped and the next day they launched another group of about twenty bombers which would have really put us out of shape. All we had was our five inch guns. The weather turned them back again.

One thing I remember, you probably have been told already, when we graduated from the Naval Academy you had to serve two years in the Fleet. There were three things you couldn't do. You couldn't put in for aviation, submarines or get married, any one of those hazardous occupations. That was really a great thing, which was great for both the Fleet and us.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think it would give a career officer the basics that he didn't get in the Academy and give him a stronger foundation for what ever he did specialize in, even marriage.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Even in those early days on the CASE when I joined it, there were only five regular officers. I was a regular and I made the sixth regular USN officer. The rest of the thirteen officers were reserves. So, that was a great exposure to them. For us, for the Ensigns, we were qualified as watch standers within about three months. We were exercising very heavily. We were exercising on night drills, night close formation, and you remember our ships had no radar. We had to kept contact by a float with a ship ahead. So, ship handling was a profession then. You had to work at it. The skippers were great. Bob Bedilion was my skipper. He had been first lieutenant in the Chicago. He was a wonderful bear of a man with a big black mustache. He lived on the bridge in that chair. I don't know how he lived.

We spent a lot of time at sea. When we got to the Aleutians, you know, the regimé was you had to go to general quarters an hour before sunset and an hour before sunrise. After about a month of this in the wardroom we were getting an average of about four or four and a half hours of sleep a night, because the nights were very short and the days were long. You were standing your regular watches and then in addition you had to go to general quarters early. We survived very well. I got off the ship in Adak. That was

our sixtieth day at sea for a destroyer. That was rare. We were down to beans and rice. We had just about emptied the food locker. But we got along. We put the Army ashore in Adak and we stayed because we had a commodore on board who was a senior commander. We stayed as the antiaircraft ship there. We steamed in a square search day after day, night after night. One of the gentlemen was Simon Bolivar Buckner, Army Colonel at that time. They came aboard, he and his aide, and they almost shipped over to the Navy. He got a hot shower and a steak--he hadn't had anything like that. I had to admire the Army Air Corps. You know in ten days they laid Marsden Matting, and on the twelfth day, they started operating airplanes from them. I couldn't believe they got them in there. Bombers, the B-25s were in there, fighters were in there. They were living in terrible conditions. Buckner and his aide could hardly walk around the ship. They had been reconnoitering around the island and had gotten in the muskeg and pulled the hamstring on their legs trying to walk. We laughed, said they better ship over to the Navy. We had hot showers and good food.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you had any beans and rice.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

We ran out.

I left the ship, I guess, in late '42 and went to Texas, Orange, Texas and put the John Rogers, a destroyer, in commission. By this time I was full lieutenant and I put it into commission as the gunnery officer. That was an interesting thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now you had left the CASE before it was involved in the collision with the O'BRIEN, hadn't you?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No, no I was aboard when we had the collision. I had forgotten it was the O'BRIEN. We had gone back to San Francisco. We came out in the fog and we were

going to escort a convoy back to the islands. That's right. I had the watch in the fire control director. I was a witness and testified at the investigation.

Donald R. Lennon:

You may want to mention that to Admiral Price. He was on the O'BRIEN.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I sure didn't realize that Frank was on there.

Donald R. Lennon:

He was on the O'BRIEN and in his narrative that he is writing, he said he thought it was the CASE but he wasn't sure whether it was the CASE or not.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

It was the CASE. Captain Bedilion was still there on the bridge, not very far. He took a look and he thought that the O'BRIEN, actually--let me elaborate because my testimony was that he was directed by the commodore to go back through the fog and search for the ships. He resisted that. He said it was pretty dangerous. We didn't have radar, and the commodore said, "No, go back and see where they are and collect them." So, we were steaming, I think at standard speed probably going into the fog. All of a sudden almost dead ahead we saw a ship heading on the exact opposite course. My testimony was it was slightly on the port bow. I think the Captain obviously saw it from his viewpoint slightly on the starboard bow and he went hard aport for it. I knew that was wrong because you really should go right if you're head on, that was sort of the rule. He turned hard to port and the O'BRIEN tried to turn too and just took our bow.

Donald R. Lennon:

Admiral Price said that when they saw it, they cut speed and tried to stop.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

We tried to go full emergency reverse, but I think we were doing about twelve knots. We couldn't do it.

Donald R. Lennon:

He said the CASE had not sent out a message, a radio message, that they were coming back and so they . . .

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I would like to talk to Frank about that. I'll see him. So, then we just went on back to the shipyard. I think in less than ten days they replaced the bow. There was a small investigation in which I testified. That was all there was to it. It was a wartime collision. We felt that Captain Bedilion, who was a commander, was going to go on to great things. Strangely enough, when he was on duty in Washington after the war, he took a flight in a SNJ with a naval aviator down to Norfolk and they hit a mountain and lost both of them. It's sad. He was a marvelous guy as you can tell. I'll be darned, it was the O'BRIEN. Funny, I have part of the ship's history here and it didn't say anything about that.

Donald R. Lennon:

They want to forget that.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. So, I went to Orange, Texas and put the JOHN ROGERS in commission as a lieutenant. We went down to Trinidad for shake down. H. O. Parrish was the skipper. The skipper and the exec. and myself were the only officers on the ship that had ever been to sea on a combatant ship. This was really shaky. The whole group were all reserve officers or one or two fresh caught ensigns, but they hadn't been to sea. But we had a good shakedown. I only spent six or eight months on it, in that boat. Then I went to aviation. I went to Texas. I went to flight training.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, was the JOHN ROGERS involved in any action or were you just getting trained?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No, we were happy to stay out of it. That was during the period when the east coast was getting a lot of submarine activity. We did see a number of fires from the tankers or merchantmen that were knocked off. We were a little apprehensive steaming along, because the submarines were very active. We had a good ship and it was a good

time. We didn't have any problems shaking down. They built some good ships there in Orange, Texas. Texas was dry, but luckily Orange, Texas was right on the border of Louisiana and you could almost walk to the nearest pub.

I went to flight training, getting into Dallas, Texas in the summer, which was hot as the devil. The training program for the aviators was all set up as if everybody was an aviation cadet. We were all full lieutenants. They tried to treat us as aviation cadets and put us in the barracks. We resisted that. They made us pay five dollars a month to be members of the Officers' Club so we could buy liquor there, but we weren't really members of the Club. So, we couldn't use the Club, because they didn't let aviation cadets use the Officers' Clubs because they weren't officers. So, some of us objected to that and we moved into town and set up headquarters in the Melrose Hotel. This was a little bit to the consternation of the base commander I think, but that was within our rights. We were not going to live in the barracks like AuCads, although we partook of the strenuous exercises, the drills, and the calisthenics when we couldn't skip them. Playing basketball with one hand with a boxing glove on and you could just knock the first guy down and that is how you played basketball with ten on a side. We went through flight school, and then went to Pensacola and got our wings from Admiral George Dominic Murray.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looks like they would have enough veteran navy officers going into flight school at that time that they would have made some provisions for treating them differently.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Well, I guess they hadn't adjusted to it, because the flow of trainees was going pretty strongly. Basically, aviation cadets are people with two years of college who come into the reserve program, and they were just beginning to feed them into the fleet after

two years. This was in '43; the war is going pretty quickly at this time. We got our wings in November of '43, I guess, and moved us through there pretty fast with an occasional casualty and loss of a classmate. Then we were sent to so-called operational training to Sanford, Florida. We went through a training course in gunnery, navigation, and so forth. We were flying those old F4F's, and then because we were lieutenants and because they wanted to build up a little flight time for us, we stayed as instructors for a year. That was really interesting.

There was a setup that saved a lot of aviators' lives, because the BOQ was roughly 18.7 miles from Rollins College, where the girls were. All the girls were living in sorority houses. They had to be in the sorority houses by ten o'clock at night. That was life saving for us because we were back on the base early. Flight training was interesting.

One of the lads who went through with me is Duke Windsor who is at Vicars Landing here now. We got our carrier landings in midwinter off Chicago in Glenview on one of those flat top converted lake steamers, the sable I think it was, which was a real flat top. We qualified in the snow. When we got there, one fellow in our flight test had gotten there two days ahead of us for some reason. He had been the regimental commander at the Naval Academy, Budge Hawthorne. Outstanding guy but not the world's greatest aviator. It was cold as the devil in Chicago after Sanford. We said, "How did it go Budge?" You know, we got these fleece-lined leather jackets and everything to wear, because you flew with the hood open all the time, with the canopy opened.

"Oh," he said, "don't do that." I said, "Budge you know we are going to freeze to death."

He said, "No don't wear all that. I did, and went right off the bow and plunged into the water and darn near drowned because I had all this heavy flight gear on." He survived. He was killed later on back in Sanford in a midair collision. We survived by flying in a lightweight uniform, but we darn near froze. We got six landings. Luckily, the first one you were locked in the right position, you just kept going around.

Donald R. Lennon:

Back in those days they didn't have thermal clothes.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No, they didn't have any navigation system either. No navigation system. You didn't have any Nav. system at all. You had a little coffee grinder where you could get some radio stations, but that didn't work. So, when you finished your landings, you were in rain, I mean mostly snow. Crewman would jump up on your wing and hand you a little card and say, "Fly such and such a distance, you should find Glenview." You know they lost many airplanes up there. There are many airplanes in the lakes up there that got lost in the weather, but no navigation. They still used TBMs and TBFs.

They just turned you loose. We went out with four of us, I guess, and a leader, an instructor from Glenview, to do practice landings, field carrier practice landings. It was snowing so hard he couldn't find any place that we could do it. We stayed close to him and he got us back to the base. So, when you finished your sixth landing you got the card. You just took off on your own, headed for home. It wasn't very satisfactory, but we all got back. There were six of us in our group. Then we went back to Sanford and became instructors. Classes were about six young pilots, and that was great fun because I think I took six classes through of six each. That meant you really got a good look at what the young people were capable of. We did a lot of gunnery, a lot of navigation flights, and a lot of simulated combat. It was good training.

So, I left there and went to a squadron in San Diego. That was the novel part of my career. This squadron had mostly the next step above F4F's for FM2's, a little lighter weight but built by General Motors or Gruruman. It was a nice little fighter plane. This squadron was the Ryan Fireball Squadron, and we were starting to get the Ryan Fireball when I joined the squadron. It was a beautiful little fighter plane built by T. Claude Ryan in San Diego. It had a propeller, driven by an engine in the front and a fourteen hundred pound thrust jet in the rear. So, that was really a thrill.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell me more about that. Someone commented this morning that I needed to get you to elaborate on those planes.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Well, it was a fun airplane, better than the FM2s. It was a high performance airplane. I joined the squadron by this time, just making lieutenant commander, I guess. Our promotions were going very well. The skipper was a commander, Johnny Gray, Navy Cross winner from Fighting Six off the enterprise. When I joined the squadron I guess there were about twenty-four pilots. The squadron was just building up. We were still flying the FM2's and F6F's. We started getting the Ryan Fireball. All of the people in the squadron, lets see, the skipper John Gray was a USN and I was a USN, I was the only ring knocker and there was another USN. The rest of the them were all reserve officers. All of them had had at least one or two combat tours. We were loaded with talent. It was a great education for me. They just made me a wing man on Ken Hippie's wing. Ken was a double Navy Cross winner fighter pilot. I learned to fly then, flying with those guys. I don't think I ever achieved the proficiency that they had, but they had the confidence of having been in combat. We would go regularly with all twenty of our

airplanes out to Los Coronados Islands and engage in a air group battle with another air group. That was pretty interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

Exactly when was this?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

'45, late '44, '45. I was in the squadron. That was a fascinating little airplane. It had tricyclic landing gear, which was something we hadn't seen before. John selected four of his lieutenants and took the first few airplanes out and qualified. We were flying off small carriers, BADOENG STRAIGHT and BAIROKO.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they catch on? I'm not familiar with that plane at all.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

It was a great potential. I think T. Claude Ryan only built about forty of them. You see the war ended in late '45.

Donald R. Lennon:

It hadn't had any defects or anything that would have been a draw back to it becoming more wide spread.?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I don't think so. I think it would have been a very interesting little airplane. Being sort of hand built we had some difficulties with the nose gear. John Gray, the skipper, and the experienced people laid out the operational plan of how you would operate a jet on the ship. We were fearful of the jet blast and what it would do. But with a tricycle landing gear, it was a wonderful piece of cake that we'd been flying. The airplane was very stable. It had four twenty-millimeter guns. It was a good gun platform.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, jet propulsion for an airplane was just starting. It was still experimental I would think.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

That is true. As a matter of fact, we were doing carrier qualifications landings on a ship and I'm not sure if it was the Badoeng Strait or the Bairotok, all from San Diego. When Jake West, who was the skipper's normal wingman, a nice young man

from Texas, was launched the forward engine started acting up. He was alert enough to start the jet engine, which was on a separate throttle. He started it, called the ship and he went down in the naval aviation history book to make the first jet landing with a Ryan Fireball, The FR1.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you use the prop and the jet separately or did you use them together?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

That is a good question, Don, because we started out just flying on the forward engine. Because the jet engine was fueled only by kerosene, and you only had a fifty gallon tank, it didn't take us long to figure out you could exhaust that very quickly. That meant you had about ten minutes of fuel on the jet engine. After you were airborne you could feather the forward engines, literally, and fly on the jet.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you got up to cruising speed then you would go to the jet?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes, you could do that. So, we persuaded T. Claude Ryan and the Navy to just change the fuel pump on it and use regular aviation gasoline for the jet with a little less thrust but not much. We didn't know that much about it. You could use the regular tanks. That was part of our extemporaneous fun to go up to El Toro and catch Marines up with an F4U. Drive up along side and feather the forward engine leaving the blades just slowly ticking over with the jet going and watch their eyes bug out. Then you did what you should not do and roll over the top of them like that. They couldn't believe that an airplane was flying like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's wonderful. Did the jet consume a lot more fuel than the prop?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. But, we had at least a couple of occasions where the forward engine, maybe the prop control, would go off or something like that. Then we had a sad operational accident. We had a young man who seemed to be qualified. He took off on his first

flight and mismanaged his forward engine, or maybe it had difficulty. We were right at San Diego, and he spun in right there before Point Loma before he got into the Bay, and he was killed. So, from then on we took off with both engines going. We probably should have. But you just had limited fuel for the jet engine and so you only used it when you wanted to do something. You wonder how capable it was. At eighteen thousand feet one day with both engines going, I admit I was pretty light weight and didn't have anything extra on, I flew four hundred and twenty- four miles an hour.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is what I was going to ask you. What speed was he getting for it.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Four hundred and twenty-four miles an hour. That was pretty darn fast.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's revolutionary.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

With the FM2, if you were flying 250, you were pressing the engine. So, that was kind of fun. It was a very maneuverable airplane.

Then the next thing was a very sad incident. We were asked to participate in the opening of Mines Field at Los Angeles and changing it from Mines Field to Los Angeles International. So, we took twenty-four airplanes up there; we took the whole bag. They were all operational. We got them up there. We put on an air show for two days. We had two guys who were very skillful in aerial acrobatics. We formed up into two divisions of eight airplanes each. So, we had sixteen in the air. Luckily, with the dual runway, we did a full program. Take off together, did loops together then formed in column and did rolls and did quite a few things, which was outside the usual operations. It was a little hairy sometimes. We carried it off very well. Strangely enough, we reduced the pressure in the nose gear oleo so, when we taxied in, we were all on the skipper's signal. We all taxied in and we all turned on signal and came right to where the

crowd was in the bleachers and on signal we hit our brakes so the nose of the airplane would bow to the crowd. That got the biggest hand of all. Isn't that ridiculous? That was a wonderful simple thing. Just a little routine. We demonstrated the maneuverability of the airplane quite well.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it ever used in combat?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

It never got out there. When I left the squadron, incidentally, coming home back to San Diego from Los Angeles, I took my division. I had four airplanes with me and an additional two, six airplanes. We climbed up through the overcast. We didn't do much instrument flying then, and headed south. The skipper came along with his group and he had them spread out. He was doing a few aileron rolls. He called to Jake West and said watch it Jake because he rolled over like this and held it in inverted position for a minute. One of the stories said a wing came off the airplane, but something came off the airplane and thhe crashed back to back. We lost the skipper and Jake West, the wing man. It was a very sad accident. I testified to the Board. The gun covers were not just a simple flap that opened up, the gun cover was almost a structural piece of the wing held by two safety wires. So, you really had to lift that thing up. I always thought that maybe the gun cover came off, which could wipe the tail off, or part of it. I just reread part of the inquiry today. Dixie Mayes had a division maybe a mile or so away, and he thought he saw the wing come off, but he would only testify that something came off the airplane. Anyhow, we lost the skipper.

I was exec., and I became the skipper for a year. We did quite a bit of flying off the small carriers. We were all set to deploy. We were aboard the carrier when President Truman dropped the A-bomb, which we couldn't understand when we heard it on the

radio. That was sort of the end of it. I was relieved by a lad and he took over the squadron. Then they diverted it from just a fighter squadron to an ASW operation where the slower airplanes, the TBM's would search with sonic buoys for submarines and then the Ryan Fireball, which had a lot of dash to it because of the jet, would be the killers. They would be vectored in to kill. That was the aim of using them. They finally used them all up. They were hand built.

The day we got back in, I got the word, when I had gotten into the hangar that Johnny had been killed. We had some popped rivets on them before. We grounded the airplanes. I did. We inspected them all and we had some that had pretty severe structural damage, but they were all repairable. So, I was a booster for the airplane. I read an article not long ago by Bill Patterson who was in the squadron after I was. By this time they were beginning to suffer from carrier landings, which are tough and hard usages. They were having difficulties with them. My viewpoint was optimistic. When I was in the squadron, when I joined, we were people with excellent maintenance work and we had first class mechs. Everything was great. When the war was over you lost a lot of those people. So, the peacetime squadron might not have had the same material, support and expertise that we had, and the planes got old. I would say that the Navy got their money's worth out of the Ryan 5.0, because it was going to be a fun, a good airplane. It was going to be a good competitor for the zero because it was light weight.

Donald R. Lennon:

It would have run circles around it wouldn't it?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. We could manhandle the F6F and the F6F was carrying the world. They were carrying the battle to the Japanese and shooting them down.

Donald R. Lennon:

I suppose it was the precursor of regular jet planes?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

By the time I left the squadron, the first FJ's that were built by North American had been delivered to a VF51. I knew those people on the other side of our field. They got the first big bulky full jet. We were ahead of them a little. It was an interesting program. I enjoyed being up there. We went through part education about compressibility, because we didn't know. We knew that the P38's were really having trouble in diving at high speed. The controls would freeze on them. So, we were trained to watch for indications of compressibility when we were diving. We didn't have any real trouble. The airplane was slick. I have on account of one of my incidents with it so I'll give you that, too.

After that I got ordered to Washington, to the Weapon System Evaluation Group which was interesting. We were mixed in with civilian scientists. As an organization, we worked directly for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Weapon System Evaluation Group. WSEG we called it, was in the Joint Staff confined basement, really. Then you had a lieutenant general Airforce who was the boss and you had a flag officer from the Army and the Navy. That was interesting work. We just looked at various scenarios of how you would fight the war. I spent three months in the Army library mapping out all of the railroads in East Germany and Russia to see where the railroad gauges changed, where we could block them.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is '46, '47 period along there?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. Then I went to the War College, Senior Course. I was still a lieutenant commander. We figured the Bureau really got screwed up. They sent two of us. Moon Mayhow and me. We showed up at the Senior Course of the War College, and all the people were senior commanders and a few captains. So, we got freshman beanies, Don.

We wore beanies like we were freshman. That is when I first got to spend some more time in jets, because they had the Baeorsliee over at Quonset Point. You flew that for proficiency. War College was interesting. I left the War College and went to the INTREPID as the operations officer. I beg your pardon, I had a staff job in-between. I left the Ryan Fireball Squadron and I went to First Task Fleet, which was right in San Diego. You know, I'm glad you asked me because I've screwed up. I'm going to give you this so your record will be a little straighter.

When I left there VF41, I became the Aviation Officer, Fleet CIC Officer for Commander First Task Fleet. Here, there it is. That's where we were based in San Diego on various flagships. One time we were on the IOWA, the big battleship, which then only had a thousand to men it. That's when I had a couple of mishaps in flying before I did very well. As aviation officer on the staff, I was tasked to go and fly with the P2V squadron, the first squadron to have the big multi-engine ASW planes. They were participating in an exercise with a jeep carrier and a submarine. In brief I flew on a P2V. We launched about five in the afternoon, and about 2:15 in the night, we flew into the water at about a 165 knots. Only two of us survived out of the eleven. The submarine saved me. The PINTADO found me and picked me up. I was still conscious.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the cause of you being in the water?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Well, the whole story, Don, is we had three P2Vs in the search pattern and we drew the low pattern, which is about two hundred feet. We had been airborne since about five o'clock, so we had been up there quite a long time. In order to fill in the time, I was in the aft part of the airplane. Every twenty miles we would drop a flare and then ten miles another flare and then twenty miles, a rectangle where we thought the PINTADO

was. The PINTADO was the first submarine with a streamlined sail on it. A guy named O'Neil, Eddie O'Neil, was the skipper, and I had been on that submarine about twos week before for a short cruise, makee learn. I had to climb back over the wing strut into the cockpit. The signalman was just back of the pilot and co-pilot, in a little jump seat. The signalman was just coming back to rig a lamp. Ironically, the submarine had surfaced to sort of say "We surrender, we are out of electric, out of juice. Your exercise is going to be over." Now, I had participated in flying the airplane for quite a bit of the time. It was a really black, typical, fuzzy, dark, California night. We would come up to the corner--these were the days where you did positive movement on the controls--and the plane commander, a lieutenant commander said, “Don't forget, Bill, that there is a sixty foot wing you have sticking out there, so be careful, don't forget.” We were right on two hundred feet. What we surmised, I just walked in there and sat down between the two. The pilot was looking to his left. The PINTADO only had a signal lamp, a twelve inch signal lamp on small bridge. He was watching that and he looked back at his instruments, and I think he misread them. He read, you know, the wing was down like this and here is the horizon. He started rolling the airplane smartly to correct thinking it was this way. I reached for the yoke with the co-pilot and we didn't stall or anything, we just flew into the water at 165 knots. Wham! I didn't have a harness on, so I went right into the instrument panel and something in the overhead. I was reasonably conscious but I was in the water and we think that the nose broke off.

Donald R. Lennon:

The plane probably disintegrated on impact.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Just about. Just about. I got out somehow. I got to the surface. I had my leather jacket over my Mae West so I had to get rid of that; got rid of my shoes. Then I got one

side of my Mae West blown up. I don't know why the other side didn't do it. The co-pilot damn near drowned because he couldn't get himself unhooked, but he got unhooked. The skipper of the sub said he came to the bridge where he only had the officer of the deck and the lookout. He said, “Where is the airplane?” They said, “We don't know we thought it was over there somewhere.” Fortunately, Eddie was a light plane flyer. He said, “They've gone in.”

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they didn't see it hit?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Not exactly. The testimony didn't say. They just disappeared. When I surfaced, luckily we were pretty close to one of the flares, the choppy sea with fairly heavy wind. I was trying to make my way over to be near the flare for some reason. The other thing I was thinking of was what time is it? When will it be light? Eddie brought the PINTADO right along side me and put a life ring over and literally just pulled me aboard. They wanted to know how many people were in the airplane. They recognized me because I had been aboard. I said, “I think there were eleven or thirteen; I'm not sure. A full load, maybe a couple of extra people.” I don't mean to stretch this out but there were some more heroics at this point. They spotted the co-pilot. He was no more than forty yards away, they said. One of the engines of the four that the submarine had was down, and the wind and sea was such that O'Neil was fearful of getting underway for fear he would lose sight of him. While he is trying to maneuver the PINTADO to get closer, the second class torpedo man put a heaving line around himself and another guy, left it on deck, and went into the water and got the co-pilot and dragged him back to the ship. All of this exercise obviously exhausted them. As the submarine rolled they were battered against the side. They looked like hamburger, but they weren't seriously damaged. We figured later on--

he found me within thirty, thirty-five minutes and got me aboard. It took an hour and half to consummate this rescue. In the meantime, right away, two lieutenants had gotten into an unmanageable rubber life boat and paddled out trying to find some of us. They got a white hat off of the signalman just as they lost him. Isn't that amazing that those people did that? I think the torpedoman got, in my testimony I said that was really courageous. They didn't know the extent of my damage. I was pretty bloody. I had what looked like a fractured skull. The worst thing I had was Ibit my tongue. I was covered with oil, so they had to strip me. They had a corpsman and later on they kidded me and they said, “We knew you were seriously hurt.” And I said, “How did you know, I was reasonably there.” They said, “You refused brandy twice.” So, thirteen hours later we steamed in. It took that long to get back into San Diego. Oh, there is another part of this. You're right, when you get started you can't stop.

They transferred at sea in this weather a flight surgeon from the carrier, the jeep carrier, to us. He was in worse shape than I was. He was terrified. They dipped him in the water, you know, transferring him by a highline, at night. All he could say was, "I think he is going to be all right." My face was gashed up, but they didn't know. Then we got back into San Diego, and they put me in that damn wire basket and strapped me in. I said, “I got to have my hands free.” They wrestled me up through the hatch and got me to the hospital. Your memory is not too good. I thought I was in the hospital for a week or ten days. I was actually in the hospital for a month in the room with the co-pilot.

Donald R. Lennon:

Lost sense of time.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes, we were bruised and battered, but really didn't have a broken bone.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you were the only two who survived?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Only two out of the eleven. The co-pilot's wife, he was a lieutenant, she came up there with about four kids. She came after about the first week and said, “He looks in good shape to me.” She took him by the ear and took him home. I was a bachelor so I stayed in there. They really didn't do a whole lot, but just observed me I think. I think they were wondering if this head injury was, as originally written up, a fractured skull. However, it was just a severe laceration and a bump on my head. The treatment was just rest and hot tub, soak in the tub. We had a bathroom that we shared for a month. I survived and went back to duty. A year later I got married for the first time. So, we knew it was a head injury, a serious one. That was a joke, not a good one. When I left the hospital I told them, I said, “At least I'm going to buy a Cadilliac car or get married.” And they said, “Buy a Cadillac.” I didn't do that.

So, then I left there. I better follow my own script here. I beg your pardon. I think I've got it straight now. We went from first task fleet to Jacksonville, right here, in 1949, and served on Commander Fleet Air Jacksonville staff for two years. It was a wonderful time. We had five air groups, twenty-five squadrons, and we claimed the first order we had the Admiral sign was that the staff will fly with the squadron. So, we flew with all the guys and had a great time for two years. Then I got orders to test pilot school in Patuxent River, and so did Duke at the same time. The Admiral said you better flip a coin. I'm not going to let both of you go. So, we just decided Duke wanted to go. He was married and had a family. I was married by this time and had two children. He had one. He went to Patuxent River. Shortly thereafter I went to Albequerque to the Special Weapons Organization.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was around '51 or there abouts?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. '51. That was an interesting tour, also. A little unusual. I checked in and found it was a joint command, commanded by Army General Montague. I remember very vividly watching him mow his front lawn in T-shirt and puttees, shined puttees. He was old school Army, I'll tell ya. I joined the staff to teach what they called Characteristics and Effects of Atomic Weapons. The basis was the Trinity shot and Hiroshima and Nagasaki. That was the basis of our bomb physics. The staff was a mixed staff headed by an Army colonel. I had to wait and wait for three sets of clearances to get through. The colonel said to me, well commander, you are going to teach nuclear physics. I said, "I don't know either one of those subjects. I don't know anything." But, to do my lesson plans, I finally got the third clearance to go into the secret ultra secret library to get the information to teach what turned out to be bomb physics. To my dismay the handwritten text and signatures on most of the material that I gathered were signed by Claus Fucks [Fuchs], who had just gone over to the bad guys as a traitor about four months before. So, I used all of his information and stayed in the staff for almost a year. That was interesting. We set the course up and trained Army, Airforce, and Navy senior people, colonels, lieutenant colonels and captains in what the bombs did.

Then I got transferred up to the staff, which was great for me to participate in the suitability test. We would go to the ships and take the bomb. I got embroiled in the battle between the Airforce and the Navy on the large bomb. The Airforce wanted sole control over the atomic weapons. People I were working with in the development of the atomic weapon said, "You know, we could build a smaller weapon that could be carried by a Navy airplane." The Mark 6 was a great big weapon, you know, and the Navy built the F.J. to carry that. It was a clumsy thing. My boss, Admiral Ramage now, who was

then a senior commander, regularly almost got fired from his job for saying that the Navy could do this job, and then he enlisted a senior mathematician who worked in the summer at Sandia Base. He was the director of mathematics at the University of Indiana. He carried a lot more weight than we did. They fought the battle for the small weapon and keeping carrier aviation in the atomic weapons business. I attribute a lot to those two guys and a few others, Admiral Tom Walker, etc. So, that was interesting. We would go to the ship and see if the ship knew how to handle stuff and security was unbelievable. We couldn't talk about it.

I left there in '53, along with Jay Ramage, who was a commander. We both went to Air Group Nineteen when the Korean War was on. I took command of VA195. That was a happy time. We went to Korea on the ORISKANY. We did not drop any bombs on North Korea. Facetiously, we claimed that they knew we were coming, and they went into a truce that was arranged with Harry Truman. We got there and the war was just over in Korea. So, we had a good first tour. In the group, Air Group Nineteen, there was an outstanding lad named Al Sheppard, who became the first astronaut. Al was in our air group.

I finished that tour and then went to Washington in WSEG, Weapon System Evaluation Group, and then to War College, and then to Ops Officer of the INTREPID, another good job. Good people. As you suspect, you know, for the aviators in the regular Navy you ended up with some people who had become regular officers, but there were not that many naval academy graduates in the group. So, you really grew up with a fine bunch of reserve officers who are very good at their job. The reserves in aviation carried

the war to the Japanese, and mostly in Korea too. Though in Korea, we had more regular Navy people.

What happened after ORISKANY? We were sent to beautiful Pearl Harbor. I went back there again on CINCPACFLT staff which was another good job. Unfortunately, being at sea a lot of those times away from my family, we had split. My wife stayed with the three children in Coronado. The good Lord looks out for you pretty well. The CINCPACFLT in Pearl Harbor was the best place for me to go at that time. It was a very good staff job. I was fully occupied in very interesting things in a delightful climate. I played a lot of tennis. It helped me over the rough spots after a ten year marriage.

Donald R. Lennon:

A military career is really rough on marriage.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Very difficult. Even on a smaller scale, I would see people who were in the Pentagon with me who left their families in Norfolk and they commuted. You are always in trouble, because you can't be there to help when things go wrong.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you never know when you might be half way around the world.

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

That's true. So, I was separated quite a bit. That didn't help us. I had over two years there CINCPACFLT staff. It was a fascinating job. I was the director for Capabilities and Requirements of the Pacific Fleet, and I made Captain. Then I went on to the Seventh Fleet as the operations officer, because the vice admiral in charge of Seventh Fleet, Don Griffin, had been my skipper on the ORISKANY. I think that is where I got the job and I had a pretty good background. He took me on as his operations officer. We were home ported in Yokosuka, but we were in and out of there. We were on three different flag ships, ended up on OKLAHOMA CITY. I went through Admiral Don

Griffin and Admiral Bill Shea, who was a marvelous guy, and then Admiral Tom Moorer. So, I had over two years in that job. You could tell these were all good fun jobs.

I was a bachelor and so was a fellow named Bill Flanagan, who was a year behind at school, maybe two years. We rented a half Japanese half westernized house, because the admiral said, "Look you can't live on the ship. That is not feasible. Get a place ashore so you get some freedom and be sure you get a telephone line." The mamasan brought the telephone pole and the wire so I could have a telephone so I could be called. So, we would be in Yokosuka maybe two or three weeks at a time, and then we would work our way down. We had six visits to Hong Kong (I arranged the schedule of course.), Philippines, and Okinawa. It was just fascinating duty, working for first class people. I had a staff of 31 people working for me alone. I of course called them Fighting 31, we had our own pennant "FIGHTING 31" and our own parking. Except for having a squadron, and I had had two squadrons, that was probably the highlight of my career, because you were right on the front line. During that period we had the missile crisis with Cuba and Krushchev. We had to take precautions. We didn't know what was going to happen, what the Soviets were going to do, what the Chinese were going to do. I came back from there into Norfolk and became the assistant chief of staff for Readiness, Naval Air Systems Command. It also was a good job, but a paperwork and bureaucracy kind of job. We had a good hard charging chief of staff who trained us and made us work. But it was a nice waiting position. Maybe I slipped in-between.

When I left the Seventh Fleet, I went to what we call major command or "makee learn" ship. I took command of an oiler. So, when I left Seventh Fleet I went to the NANTAHALA, named for the Nantahala River in western North Carolina. We had a good

cruise. We took the NANTAHALA to the Mediterranean for about seven and a half or eight months, providing fuel for the INDEPENDENCE, where my friend Jig Dog Ramage, Jig Ramage was the skipper of the INDEPENDENCE. I was still traveling in good company. He was a bachelor by this time again. So, we had the Med cruise which is always fun, ports interesting. Beirut was a beautiful, sophisticated city. We had two weeks there, and that was before the war. It was just wonderful.

Quick story. I started to leave the NANTAHALA one day. I said, "Get the gig along side, please Exec." He called me back and he said, “Just a minute, Captain.” Well, I said, “Well, you know I have to go ashore. I have to rendezvous.” And he said, “We are having trouble with the accommodation ladder.” And I said, “Well, that's all right. I'll just go over the side where the boat is.” “No, sir, you have to wait a few minutes.” When I finally went out to see what the problem was, there was a dead horse lodged under the accommodation ladder. It had been floating around the harbor all night. I said, “We do have a little problem with the accommodations. Finally the boat captain came along and lassoed the horse and dragged him away from under the ladder so I could go ashore.

Can I revert to one sea story about Pearl Harbor? We had a seaman first, named Steven who never could make third class, never made a rate. Everybody tried to help him with exams. Seaman First, part Indian. Had been in the Navy probably ten or twelve years. He was a good mechanic. He was a typical mechanic. When I'm down in the engine room with him and he's working on a pump, he used the old hammer system. He knew exactly where to tap that pump so it worked. He couldn't explain how it worked,

but he knew exactly where to tap to free that valve up. You know the old joke about don't use force, get a larger hammer, that was Steven. He was also a Boat Coxswain.

When I was up and down between the engine room when the Pearl Harbor battle was going on, he manned the boat. I'd send the boat in. I said, “Go to the officer's landing and try to find the skipper and Exec. or any of the ship's officers.” The next time I saw him I hardly recognized him. He had his whites on. He was absolutely black from the oil. He had a boat full of survivors he had picked up, because he went by the OKLAHOMA and the ARIZONA picking people out of the water, heavily covered with NFO (Navy Fuel Oil). He must have rescued three boatloads of people and brought them back to the ship. I guess we had one corpsman and he had an assistant. They were cleaning the survivors' eyes off, wiping them. I think when we finally got on our way that afternoon, when Stevens and I got under way had over thirty people.

Donald R. Lennon:

He had single handedly rescued?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

He pulled them in the boat and got them. Some of them got to us, some of the officers came on board in pretty good shape. That is, they were in civilian clothes. It was part of the pattern that you mentioned earlier. That was his job, to go run the boat. He didn't think he was doing any heroics. I thought he was, because by the second air raid, by the time he went back, the Japanese torpedo planes were going right across his area into the battleships. But, that was part of the game. That was Steven doing his job. He was a mess when I saw him, covered with black oil.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he ever make his promotion?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No. He should have gotten one, but I don't think so. Oddly enough, the quality of the young Fire Control Man who worked for me, was such that, three of them got

commissioned within a year as ensigns. One of them made commander in the Navy. They were high quality, well trained young people. Almost none of them married.

Well, back to, where was I? Back at Norfolk. From there because of my background I got command of the carrier SHANGRILA which was a real coup to make it. Mostly, I think the chief of staff got it for me. It was sort of sad. A wonderful guy from Jacksonville named Ralph Werner was the skipper and he had an operation for cancer. He had been on the ship about six months, and the flight surgeon detected signs of deterioration. So, he was detached from the ship. I flew to Malloria and took over the ship and finished the tour in the Med. with the carrier with the same wonderful people. The fellow that was Air Group Commander was Tom Hayward, who as I said when asked about Tom Hayward, I said, “Well, he was a pretty good aviator but didn't really amount to anything. He became the Chief of Naval Operations for us.” I came back through Norfolk and went back and took another air group aboard with Ovy Oberg and worked them up. Then I was detached from that ship. I was relieved by this nice guy Hope Strong. Unfortunately he is dead. He was a year behind me at school.

I then went to Washington. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs has a small personal staff called the Chairman's Staff Group. By the time I joined it, there were six officers, two from each service. Then they made another one, so you had two Navy, two Airforce, two Army and then you had one Marine. That was another fascinating job, because you sat right outside the chairman's office. When a "big poker game" was held in the tank that held the Chief, you were privileged to sit behind the Chairman if you had an action paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this mid-sixties?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Yes. This was about '65, '65 or '66. '66 I guess, cause I retired in '69. Late '66, General Wheeler was the chairman. A wonderful guy, and George Brown Airforce lieutenant general was the assistant. George was West Point '41 and I was Naval Academy '41. He said, “That's about right Bill. I'm a lieutenant general and you're a captain. That's about right, about equal.” He was a wonderful man to work for. We had lots of laughs together. But the fun was, we would go up through all the action papers. We were dealing with those whiz kids from the Secretary of Defense's Office. Macnamera was in there. Those were some real interesting battles. We would study the papers. You didn't study in your rank just because you're Navy. For example, the desk that I inherited from Blackie Weinel had to do with all the weapon systems, Single Integrated Operational Plans, SIOP, for nuc. weapons, the just chase cap(?), all the war plans where atomic energy was involved, which was frequent. It was a damn good job, interesting job. I didn't have to do it in a daily operation.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was McNamara one of those individuals who thought he knew it all?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

I think that Mr. McNamara led to the early death of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Staff Bus Wheeler. Bus Wheeler would leave his office in the late afternoon and go up and grapple with Mr. McNamara. Occasionally, but rarely, he would go to the White House with him, because President Johnson was doing targeting with McNamara, which turned out to be a battle between the Navy and the Airforce about tunnage and body counts, and body bags. Bus Wheeler would come back down about seven o'clock at night, we were in the office there, and he would come in and shake off his jacket and say, “Well, I hope you guys had a better day than I did tonight.” You know, that sort of thing. McNamara was difficult, brilliant, egotistic, you know. Properly led it would have been

all right. Bus Wheeler was a hero. He had a massive heart attack and was out of the office as chairman for six weeks, and I don't think that word even got around. The Chief of Staff of the Army became the acting chairman and ran it very well. Then within a year after Bus Wheeler retired, he died. I think the struggle through the war of Vietnam with all of its problems weighed on him heavily. So, I retired out of the chairman's office there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the chairman in agreement with the way the war was being conducted?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

No, but he was such a low key individual. He saw the opportunities for more offensive action and he fought against it. He was representing not only his views, of course, he had to represent the three other services. Tom Moorer was Chief of Naval Operations at that time. General Green was the Marine Commandant. The Airforce was John McConnell. He had been a classmate of the Chairman at West Point. Those were some real battles in those days, for money, you know for funds. The war was part of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Money more than logistics and the actual conduct of the war?

William E. Elliott, Jr.:

Well, I think being a combatant, General Wheeler saw opportunities when we should have taken offensive action. When Tom Moorer came aboard I was still there for a brief time, but Admiral Moorer, if anyone, had been given credit for the December bombing raid on Hanoi, he forced it through. That was critical to bringing them to the peace table. In our office we only had three desks. Navy was the first then Airforce and Army. We worked the problems for the Chairman. We would look at these long papers coming from either the Service Chiefs or coming down from DOD and get what we called the Major Smith test. If Major Smith could understand it, then initial it and send it in to the Chairman. If Major Smith couldn't understand it, send it back down to the Joint

Staff and have them work on it. The Joint Staff was full of talented people, Bill House and a lot of them were good people.

Donald R. Lennon:

You hear a lot about the figures that were coming out of the Pentagon on body counts being just grossly undercounted. At what level was that coming from?

William E. Elliott, Jr.: