| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #102 | |

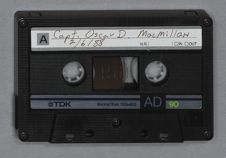

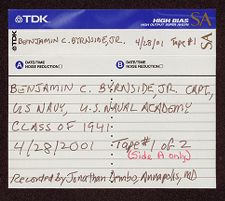

| Captain Oscar D. MacMillan | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| February 6, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

You were born in New York?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Niagara Falls, New York.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's start out by giving some of your background--your early education, what led you to the Naval Academy, and any observations you have from your Naval Academy years.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The reason I was born in Niagara Falls was not because my mother and father were there on their honeymoon. It was because my mother was a native of Niagara Falls. She had an English father and a Canadian mother. My dad was a chemical engineer graduate of Gettysburg College and worked in a chemical plant in Niagara Falls. They met and married and had three children. I have two older sisters. I was the baby. I was born May 13, 1919.

I lived in Niagara Falls until 1926--I was about seven years old--when my father's company, the Niagara Alkali Company, went broke. It was an early sign of the Depression, it just failed. He had been the chief chemist and suddenly was out on the street without a

job. This was happening all over the country at that time. He finally got a job with Union Carbide but had to start out at the bottom. They were building a new plant in South Charleston, West Virginia. We moved there when I was seven or eight years of age and I was there up through high school. It was a nice place to grow up. It was a small town of five-thousand people. The plant was the whole life of the place. During World War I, there also had been a Naval ordnance plant there that made armor plate and big guns for battleships. That was closed down but all the government housing they had built for the workers was kept in a state of readiness. They rented them to civilians just to pay for the maintenance.

So I grew up on a government reservation with Marines patrolling the streets. The military atmosphere had an influence on my desire to enter the service. Also, I had a grandfather on both sides, one Army and one Navy, so I had a little background of service. My mother's father was in the Royal Navy as a boy from twelve to twenty-four. That's how he got to the United States. He came over and was discharged in Boston, but that's another story. When I was about in the fifth grade, Admiral, then Commander Richard E. Byrd came on a recruiting drive for the Naval Academy. Believe it or not, they used to do that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Came to West Virginia!

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes. He came to this little government school and he was the most wonderful thing you ever saw in your life! He was in his white service uniform. He was a very tall, handsome, distinguished-looking fellow. He talked to us about his exploration of the Poles and also about the Naval Academy. That's when I decided that I wanted to go there. Really. It was a very effective recruiting tool. I told that story to some of my friends in the recruiting division in the Bureau of Personnel. They said, “We're still doing that today, but

we don't have any heroes of his calibre walking around.” I've done a little bit of that myself just recently around the Florida Keys in some of the schools.

I graduated from high school, but my father was unable to contact anybody that would give me a political appointment. West Virginia had very few representatives, maybe four or five, and none of them were available. My dad and I decided that we would pool our resources of all the money I had saved while working and all the money he could scrape up and I would go to a prep school in Washington to get smart enough to pass the exam. At the same time, I would join a Naval Reserve unit and get eligibility to participate in the exam, which I did.

Seven months of this school was just rote. We took an exam every week. We learned to take exams. We learned to absorb printed matter. We learned how to study. It was more useful to me later on in training and studying than it was as a device to get into the Naval Academy. As it went, I got in. I entered in June of 1937 and graduated in February 1941, four months early because of the war situation.

In 1940, we in the Navy knew we were going to be involved. We already were involved in escorting lend-lease ships across the ocean. That knowledge had an effect on our lives, particularly on our last year, because instead of modifying our curriculum and eliminating non-essentials, they just took everything and doubled it up. We had the full curriculum in half the time. They took our September leave away from us, so we started the first of September instead of the first of October. We went solid. We had one day off at Christmas. We worked New Year's Day and graduated February 7, 1941. That's why we're here this weekend.

Donald R. Lennon:

I had not heard that you lost all your holidays in compressing that final year.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

They gave us Christmas day off. We were raring to go. We wanted to get out to the Fleet because we thought maybe we wouldn't get there in time.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't want to miss the war!

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

At the Academy, you were active in a variety of sports: football, crew, . . .

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I was kind of a lightweight for varsity sports. I was tall but I was kind of skinny. I weighed 150 pounds and I was 6 feet, 1 inch. I didn't get any varsity letters. I played mostly intramural sports: basketball, crew, tennis, and so forth. I made the plebe team in basketball, but I was third string or something like that. I preferred to play on the intramural team where I got to play all the time instead of sitting on the bench. I loved the intramural sports. I wasn't big enough for football. I wasn't big enough for the heavy-duty track things. I just had a good time. I got to know my classmates a lot better out on the field. We played plebes against the first classmen instead of plebes against plebes, so I got to know a better cross section of people really well by getting down and rubbing my nose in the dirt with them a little bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your impression of the Academy faculty and the academic program?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I had kind of a double impression. As for the instructors, we used to say that they were the referees between the blackboard and the book. The standard procedure, for example, in a math class would be to draw slips, man the boards, and work the problems. Then they would grade the problems. There was very little instruction done. It was the application of what you had studied the night before to the blackboard, to their satisfaction. They were really just referees.

In the arts, we had some good instructors. We had a good English literature instructor. His name was Allen Blow(?) Cook. We also had a very fine Italian professor. Our instructors were a cross section or mixture of very good civilian instructors and not properly prepared officer referees. That was my impression. I don't know how my classmates felt, but I think they felt pretty much the same. There were a few exceptions in both cases. There were a few bad civilian professors and a few good officer professors. As a rule, however, most Naval officers don't make good instructors.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, they haven't been trained in education.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

They haven't been trained and they don't have the patience. They don't have the skills to see what the student needs and then give it to him. I think that's the crux of it.

I wasn't a particularly good student. I stood in the first quarter, but I wasn't what we called a “star man.” A “star man” had a 3.4 average out of a 4.0, and he wore stars on his collar. I made that my last year, but I didn't get to wear the stars because when the year was over, I went out to the Fleet.

I didn't realize the importance of applying myself until about half way through the Naval Academy. A friend of my father's knew an officer on duty in the executive department, and he called me over to his quarters one day. He said he had been looking over my records and asked me why wasn't I doing better and why wasn't I working. I said, “Well, I'm playing football and basketball and it is awful hard.”

He said, “Well, you knock off all that foolishness and start working. You're going to realize that it's dollars and cents in your pocket, because your class standing is very important.”

That kind of straightened me up a little bit and I did start to work a little harder. I'm glad he did it, because I was able to pull myself up quite a bit in my standing. Before that, it just hadn't seemed important to me. You know how kids are.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh yes! Unfortunately. Are there any incidents while you were at the Academy that are particularly vivid?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Oh, yes. The highlights of your career at the Naval Academy, I think, are your summer cruises. That's the practical application. I was a kid from West Virginia, who had never even seen the ocean until I saw the Chesapeake Bay, which really isn't the ocean, but it's salt water, so that youngster cruise was a real thrill to me. I had just turned nineteen when they turned us loose for four days in Paris! You can't imagine the feeling, the freedom, and the exaltation of just being in Europe. It was something I had read about all my life, and then I was there! It was just wonderful. That's why I saved those collections of pictures. They mean so much to me because it was a real thrilling time.

I also remember when Carvel Hall burned. Carvel Hall was the big hotel in Annapolis and was used by visiting families and girlfriends who were there for the weekend. I think it's still in business. One day, I think on a weekend, Carvel Hall caught fire. It was a tremendous blaze. The fire department was overwhelmed, so they called on the Naval Academy for help. My battalion of midshipmen was sent en masse. We put on our raincoats and went over to fight the fire. I don't think that had ever happened before or since. I think it happened my first year at the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What is the relationship between the Naval Academy and the town?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

They say, “Annapolis is a small village located on the shores of the Naval Academy.” It's really not that at all. I think the relationship is kidded about a lot, but I

think it is very good. I went to church in Annapolis rather than the Academy Chapel. I was reared a Presbyterian and the chapel service was pretty high Episcopal and I just didn't feel comfortable in it. So every Sunday about thirty or forty of us formed up a party and went to the Sunday school and church of our choice. We had people who went to the Baptist church and the Lutheran church. I went to the Presbyterian church and got to know that group of people. The church family took us in. They invited us out to meals and we dated their daughters. It was a very good relationship.

One thing that didn't get along very well with the Academy was St. John's College. Did you ever hear about their “thousand-book program?” If they read a thousand books, they would have their education.

Donald R. Lennon:

No. I'm familiar with St. John's, but I've never heard of that.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

At that time, they had a system, whereby their entire program was based upon the reading of a thousand books. I believe I'm correct about this. You can check with some of the other fellows.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the school select them, or the students?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The school selected them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they take exams on those thousand books?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I don't know what the program was, but that was what they called it. Maybe the thousand just meant a lot of books. The whole basis was not instruction or lectures or anything else; it was just reading. I'm pretty sure that that was what was going on.

Also, they used to say that the St. “Johnnies” late-dated all the midshipmen's girlfriends. When you had a girl down for the weekend, she stayed either at Carvel Hall or at one of the nice rooming houses that had housemothers that were like old mother hens. A

midshipman didn't get higher than the front porch! They said that the St. “Johnnies” would always catch the girls--after we had to go back inside the wall at midnight--that from then on, the St. “Johnnies” took over. That was a bunch of hokum. Maybe once or twice that happened, but that was the story.

The relationship with the people in Annapolis, I think, was good on the whole, but I think that with St. John's, it was not so good. There were some stand-offs, but I was never personally involved. Before my time, I think, there was a big riot between the midshipmen and the St. “Johnnies.” It is not worth recording though.

The program at the Academy was: academic first year, the youngster cruise, then academic second year, and then what's called second class summer. During the second class summer we inducted the incoming plebe class. By that time, we were pretty well fixed in our routine and were kind of the supervisors, and each one of us would take a new in-coming plebe and kind of nurse him along to get him started down the right track. During that period, we also had an aviation training program, which was a lot of fun. They had a bunch of flying boats that they brought in. We did bombing and radio and machine-gunning. I have some gun camera pictures that were taken when we fired at a target on that particular occasion.

At the end of the third academic year, we had our first class cruise. On the youngster cruise, we were swabbies, “white hats.” On our first class cruise, we wore our caps and were “make-you-learn” officers. That was fun.

We were supposed to go to Europe for our first class cruise, but it was 1940 and the situation was so tense because of the war, that it was decided that we should go to South America to Rio de Janeiro. We had our cruise books all made up and our liberty ports and

tours set up when the Navy Department decided that that was too far to send a training squadron of three battleships; so, we went to Panama instead. I have some pictures of that trip. From Panama, we went to La Guaira, Venezuela, then to Guantanamo Bay, and from there on up to Boston. We happened to hit New York when the 1940 World's Fair was going on. That was fun, too. While we were there, they put on a special performance of the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes for us.

Donald R. Lennon:

How much hazing went on while you were at the Academy?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Quite a bit! Some of it was pretty bad, really. At that time they hadn't broken the color line. There was a black boy in our class who was hazed out, I'm sure. He was literally driven out of the Naval Academy. I didn't see any of it directly, but I'm pretty sure that's what happened. I had a very mean and ugly first classman. You see, each plebe is assigned to an upper classman as his “plebe.” I was the plebe for a guy named “Willie” Schlacks [William J.] who was a B-squad football player. He was a great big, husky guy and not, in my humble opinion, very intelligent. He was bestial, he really was! He used the broom on the old rear end.

There also was a lot of mental indignity that they subjected you to, which is worse than the physical to some people. It bothered me at the time, I was very unhappy, but it didn't have any lasting effect or any psychological effect on me.

I think one of the reasons that they allowed hazing, and it may not be good, is that we learned blind obedience to orders, and a certain amount of that is not bad. It's not good if that's all you do, but automatic response to an order provides pretty good reduction in reaction time. That's what stood us in very good stead, for example, on December 7, at Pearl. My training came to the surface. I did things without even realizing I was doing

them. They were automatic functions. There is a certain amount of value, I think, in that. I think, however, that some of it was excessive. My roommate was physically injured by the application of a broom to his rear end. He had to go to sick bay. There are certain people who like to inflict injury on other people, and there were some guys like that at the Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Even in a case like that where he was injured, there was nothing that could be done to the first classman?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

To my knowledge, there were no incidents of any retribution on the part of the authorities against that sort of activity. Of course, hazing took different forms. The plebe midshipman is lower than a worm, really. Quarters at the Naval Academy are ten to twelve feet wide and we had to march, not walk, exactly down the middle. We had to do double-time up and down all the stairways, or “ladders,” as they called them. We had to give tremendous obeisance to the upper classmen. They could stop any plebe at any time. They'd say, “What's your name, Mr.?” We had a routine that we had to spew out. They had some dumb questions that we had to memorize the answers to.

As I said, it has a purpose. I think it's better now. They don't do so much of that foolishness. I think, each year, over the years, it got a little less and less. I think, although I don't know, there's very little of that sort of thing now. I think they are more interested in academics than they are in trying to instill that kind of mental attitude, which may or may not be good. We'll find out someday.

Of course, what we were looking forward to all those four years was that glorious day when we would get our one narrow stripe and go off and join the Fleet. My class was very lucky in that we were the first graduates that ever went directly into smaller ships.

Normally, an Academy graduate went to a cruiser, battleship, or carrier, and he was sort of a “gentleman of the watch” for two years while learning how to move around on a ship. But in 1939 or 1940, they started the accelerated building program, and they had a bunch of destroyers that they needed officers for. They pushed nearly half of my class directly into a destroyer. That was great for me, because I liked the idea of a small ship where you can become a factor early on.

When I reported aboard my first ship in Pearl Harbor in March of 1941, there were seven officers on the ship: the captain, the exec, three department heads, and two “make-you-learn” ensigns who had had two years aboard a battleship. I was the eighth officer and they looked at me like I was some sort of strange creature. In three weeks, I was standing top watches, underway, by myself, on the bridge at night, which was rather remarkable. The other guys thought I was some kind of lucky dog, because I didn't have to go through the two years of gentlemanly watch on a big ship, where you stand and hold the stopwatch for the officer-of-the-deck to make his turns. The Class of 1941 was always very lucky, I think. We hit the peak on a lot of things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your first assignment was to what ship?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The USS HULL, a FARRAGUT-class destroyer. The first ships built after World War I were the FARRAGUT series. The FARRAGUT was the prototype. There were eight ships in the class. There was the HULL, the MACDONOUGH, the DEWEY, the WORDEN, the FARRAGUT, and three others. They were an odd breed of ship. They were designed for peacetime, if you can believe that. They had two boilers, which were put on there for in-port use. A destroyer usually had four boilers--two engines with two

boilers for each engine. But these monsters had two big boilers for use at sea and two little boilers for use in-port. It was not a very practical arrangement.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the rational for it?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Economy. That's like the story about a Secretary of Defense who redesigned the golf bag. He said, “Well, we made a study of the use of the clubs and we decided that this business of one putter and nine irons is foolishness. You use a putter at every hole, so we're going to put in three putters and take away three of the irons.”

Those boilers were for in-port use and they didn't even look down the hall and see how they would use them to give more power at sea in wartime situations. It was obvious to us after we had been on the HULL awhile that it was a bad design. In those days, the fellows who designed the ships didn't go to sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were primarily involved in maneuvers out of Hawaii during the summer of 1941?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I spent the summer on normal Fleet operations. We would probably be at sea for three weeks out of a month and then in for one week, or maybe two out and two in. The Fleet was called the Hawaiian Detachment. Most of the ships, however, had their home ports in either Bremerton (the big ships) or in San Diego (the little ships), so the families were still back on the coast. They would have R and R cruises to give the crews a chance to be with their families, and in September, our turn came up. We took the big carrier LEXINGTON and four destroyers back to San Diego for a month. I was at that time, a bachelor. In those days, when you graduated from the Naval Academy, you had to wait two years before you could get married.

Donald R. Lennon:

Legally?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Right, but some didn't wait. But most of us did. We used to call it “Protection by the Fish and Game Laws.” We were protected from all those women by the law that we couldn't get married. Some of our classmates, however, were married and had kids while they were still midshipmen. That was strictly a no-no, but what you don't know will not hurt you, I guess.

After that sortee back to the coast, we returned to the Hawaiian Detachment. We went out for the last three weeks in November, with my division of destroyers coming back into port on Friday, December the fifth. We were assigned to a tender, the old DOBBIN--a repair ship--for two weeks availability for repairs to minor machinery and other items. On Saturday, we started taking all the defective parts to the tender so they could start in on them on Monday, Sunday being a holiday. Consequently, the ship was not in very good shape on Sunday morning at eight o'clock when the whole thing blew up in our faces.

I was on board with the two other ensigns. All the other officers were ashore with their families. (I said the home ports were back on the coast, but if the officers could afford it, they'd bring their wives out on their own and they had apartments in Honolulu.) All four of the destroyers alongside the tender were in a terrible state of readiness. All the ammunition had been stuck down into the lower magazines. Even the machine gun ammunition had been unbelted and put in boxes down in the magazines. We didn't have a gun that would fire. The remarkable thing is . . . I said these things were automatic when you do them often enough . . . that we had guns shooting within minutes of the realization that we were under attack. My ship was credited with one definite kill and one possible on a Jap plane, which is rather unusual. When you tie up alongside a repair ship, you secure all your generators, all your power, your pumps, and everything else. You rely on the

tender to supply you with electricity and water and air. Of course, when the tender went to general quarters for the attack, they pulled all the supplies to the ships alongside because they needed all that internally for their own protection. So we not only didn't have guns or ammunition, we didn't have power! Nothing worked!

Donald R. Lennon:

What was involved in getting some power back?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

We had the boilers open for inspection; so we had to reassemble our boilers, light them off and get steam up in order to start our generators. That was accomplished in less than an hour and a half.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had your major contingent of enlisted men aboard?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

We had one-third of the crew and one-third of the officers. Of course, the one-third happened to be the junior section of the officers because, by agreement, we took the weekends and let the senior officers go with their families, which was right. I was the gunnery department representative; I went up on the gun director. Ensign Hooper was the engineering department representative; he went down to put the engines and the boilers back together. A guy named Murray Strauss(?) was the communications department representative and the officer of the deck.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that kind of a sinking feeling when you saw those planes coming?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

It was more like a nightmare, actually. I kept thinking I was going to wake up and it was just going to have been a dream. You can't imagine going from absolute peacetime to total war, with planes pulling out of their dives and flying by so close you could see the expression on the pilots' faces. They pulled out just at bridge level, and I was up on the gun director at the top of the bridge. I was mad at myself, because I was in such a hurry to get up to my battle station, that I didn't go to the safe and get my forty-five pistol. We kept

them in the safe because they were accountable and a high value item that disappeared if not kept locked up. I got up to the top of the director and I could have been shooting ducks in a gallery with my pistol if I had had it, but I didn't.

That was some morning. The officers straggled back in along with the rest of the crew. A lot of them had been hurt and injured by the strafing over on the liberty piers.

There was another tragic thing that happened as a consequence of the war, although it sounds ridiculous now. I had bought a little 1931 Model-A Ford Roadster. It was a classic. I had bought it second hand that summer with my hard-earned pay. I think I paid about $250 for that car, which, if new, would have cost about $500, in those days. I really loved it. I kept it on the Officers' Club parking lot. Three months after the war started, I was finally able to go look for my car. I had been ashore on business trips a couple of times, but I hadn't had time to look for it. The parking lot had been converted into a huge warehouse and they had moved all the cars over in back of the old Marine barracks. I went over to find my car and there it was, sitting on the hubs. They had completely stripped it down to the axle; the upholstery, the top, and the engine were completely gone; only the block was left. They had pulled all the parts out of it. The yard workmen had done this to the cars because spare parts were so hard to get. They were running a spare-parts business in Honolulu and they took all the old officers' cars and just disassembled them. I never got a nickel out of that. They said, later on, if you applied to the proper authorities, you could perhaps get restitution for some of your loss due to wartime. I never got around to asking for that. It was one of the little sad things that happened.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you put out to sea that morning?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes, as soon as the ship was capable of steaming. As I said, it was about an hour and a half to two hours. Time was kind of compressed, you understand. We had all our officers except the captain. The captain got caught in a traffic jam coming in from Honolulu and he was late. We also had men and officers from ships that had already left, so we had a super abundance of people. We were constantly repairing and putting things back together that we had not needed in order to move out; so it was nice to have the extra manpower.

We joined up with a group and a carrier that night and stayed on patrol off the harbor for the next three or four days. At that time, nobody was quite sure where the main body of the Jap fleet was and we were standing by for an invasion. They would have been well advised to have invaded, because they might very well have gotten a foothold on the shore. Things were not good; they were very disorganized. At the ensign level, of course, we weren't privy to any of the strategic considerations that went on in the minds of the people that were directing the operations. It was just an absolute, complete surprise to us. We had no inkling. We had been on alert, as I said, for three weeks at sea. The alert was a theoretical attack by the Japanese, believe it or not, but we weren't even told during the exercise that that was what it was. I later found out this was the truth.

The Japanese were so devilishly lucky, or ingenious, or both, to have hit us at that particular time. They caught our division completely unprepared. The battleships were particularly vulnerable because they had opened up their watertight compartments for inspection on Saturday and hadn't gotten them closed back up. Over and over again you hear these stories of “Why?” That was perhaps the worst time for us and the best time for the Japs to attack. They certainly had plenty of people on the lookout there. Pearl Harbor

was an open book. With a pair of binoculars and a location in the cane fields up above the harbor, you could see anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no security.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

There really wasn't. The Japanese nationals, who were second or third generation, were working in the shipyard and in the offices. Although most of those were good loyal citizens, I'm sure there were some spies in there. There had to be.

Well, that was the way the thing started--with a BANG.

I stayed with the HULL. During the early part of the war, we were with the first task group. It included a carrier and a group of cruisers and destroyers, and we went clear down to New Guinea in February of 1942. That was our first attack of the war. We attacked the Japanese bases at Lae and Salamaua. That was exciting because we proved that a task group could stay at sea for two months and be sustained entirely by sea-borne provisioning and refueling. We were out of sight of land for sixty days. That was a record in those days. Heretofore, it had been for three weeks, four weeks at the most, and here we steamed ten thousand miles down to New Guinea and returned. The only time we saw land was when we got within a few miles of the New Guinea coast during the attack.

We came in from the south, and the planes flew over the top to the north and hit Lae and Salamaua. The Japs had captured them from the Australians. That was where they were going to launch their attack against Australia. I think that really surprised the Japanese more than their attack surprised our top people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think that prevented the invasion of Australia?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

It was very helpful. I think it proved to them that they had better slow down and rethink this thing before they got too far extended. There have been a lot of books written about that. This was what we were thinking at the time: Let's get out there and get them!

We were on the defensive. I would say, we were on the defensive completely until August of 1942 when we hit Guadalcanal. My ship was part of the initial landing force against the Japanese there. We achieved total tactical surprise that morning. They were still at their mess benches having breakfast when our first salvos went off for the landing. We were lucky that we had a day like this; solid overcast, low ceiling, drizzling rain, and the temperature was about eighty-five degrees. We came around north of the island and steamed up to the landing beaches. My ship was one of the initial bombarding groups.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was still the HULL?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes. I was up in the gun director, as usual. We fired five-gun salvos and the first ones hit and the guys were still at their mess benches at their tents. The Marines that went in there initially were very successful and then the Japs counter attacked and that's when it got bad. We used to retire at night to the south because a Jap cruiser force was coming in and they had a lot more firepower than we did. It was very discreet to get out of their way. They came in and bombarded out troops on the beach at night in. In the daytime, we'd come back up and support them with our gunfire against the people on shore. It was a very defensive operation for months.

Donald R. Lennon:

If the Japanese cruisers came down at night, they wouldn't remain there during the day too?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

We had carrier support and carrier aircraft. They were afraid of our aircraft and we were afraid of their night shooting capability. The Japs, at the stage in the game, were much better trained, and had much better ability. Our Naval experts might contest this, but as a matter of actual fact, they were better at night fighting than we were. Witness the first battle of Savo Island, where we lost the AUSTRALIA, the QUINCY, and the VINCENNES against their cruisers. We didn't even touch them! I don't think we got a shot into any one of those ships and they just decimated those three cruisers. I was within just a few miles of that action and our skipper was so intent in getting up there and firing torpedoes at those guys and of course, our superior officer said, “No, our job is to protect these transports.” We were screen for the transports. We didn't get into that action, or else I probably wouldn't be here today. We lost almost everything they could reach with their guns.

Then we got back from Guadalcanal and we went into the shipyard for some repairs. Just as we were leaving, I got back out to Pearl Harbor on the way west and I was ordered to a new construction destroyer being built in San Francisco. That was great as far as I was concerned. I was sent back to Washington to go to a special school to learn about the new hydraulic gun control systems, then to the shipyard where I was the commissioning gunnery officer on the AMMEN 527. I stayed with the AMMEN for two years. I was the gunnery officer for a year, and then I moved up to executive.

Wartime promotion was a funny thing. I was an ensign with nine months aboard when the war started. In six months, I made jg. Normally, it took three to four years. Six months later, I was full lieutenant. I went from ensign to lieutenant in twelve months and I stayed lieutenant for the rest of the war until right at the very end when I made

lieutenant commander. I was the lieutenant gunnery officer of the AMMEN for a year and then I was the executive for a year. I left the AMMEN in 1945, and was the commissioning executive for a new construction ship down in Orange, Texas. It was one of the big new long hulled twenty-two ships, the F. B. PARKS 884. We just got into commission and we were on our way to the West Coast when the war ended, in August of 1945. I had three ships, but the third one never quite got into the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us about the duty on the AMMEN.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The AMMEN was a beautiful ship. She was a twenty-one-hundred toner. She was of the FLETCHER class. She was born in World War II and was the backbone of the destroyer fleet during the war. She was the second of eight ships built by the Bethlehem Steel Corp. in San Francisco. The ABNER READ was 526. The AMMEN was 527. Then they ran BUSH, MULLANY and on up. Normally, they tried to put those ships as they came off the line in the same division. Therefore, we had the 526, 527, 528, and 529 in our division. They were commissioned about a month apart. We were commissioned in the early April 1943. We started down from San Francisco on our shakedown to do our basic training.

As for the crew, we had a nucleus of very well trained, experienced petty officers that were sent back from active ships. We also had a whole bunch of new seamen and they were pretty raw. They were right out of boot camp. What we had to do was to go down to San Diego and run them through the schools down there and train them to be a fighting unit. We had a week in San Diego. We had just barely gotten started on our five or six training programs when two of the ships that were in our task group that were going up to make a landing at Attu had a collision, the MACDONOUGH and the

SICARD. They took the ABNER READ and the AMMEN to put us in the breech to take the place of these two ships that collided. We went up there, never having completed any of our basic gunnery training. We were there for the initial landings at Attu. My first full salvo that I fired from that ship as the gunnery officer was fired in anger at the Japanese rather than a target in training. It was rather scary. I had confidence in the crew, in the ability of the petty officers, and the gunners to match pointers, and the fire controlman to get the battery where it was supposed to be, but until I saw the results of that first salvo, there was always a little doubt in the back of my mind. I was thinking, “Here I am firing over friendly troops with a totally inexperienced and untrained group of people.” They were not totally up to where you would like to see them. It was a good break in for the ship in that we were there for about seven days of continuous support. I don't remember exactly the date, it seems to me it was in May or June of 1943. We went up there as a bunch of “boots” and we came back as veterans. That's the way the crew felt. Of course, I had been down south with the HULL, but we had officers who had never heard a gun go off. It was good training.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's breaking them in!

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes, the hard way. We stayed up there in the Aleutians for the Kiska fiasco. Kiska was where the Japs had evacuated by submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that where the ABNER READ got hit?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Yes, she apparently hit a mine and got her stern blown off. The story went on in the beer halls, I guess you might say, that she actually backed down over on one of her own depth charges.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've heard that story.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I don't know if there's any substance to that or not. I don't think so. We used to say that the ABNER READ was fouled up, but she was not that fouled up. She was a good ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think J. C. Atkinson was commanding the ship at that time.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I don't know. That Aleutian duty was very unpleasant. The weather up there is awful. It's like this most of the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Except quite a bit colder.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

You have these willywogs that come booming down out of the hills. When you're anchored at Adak or Dutch Harbor, you never take steam from the throttle. You have one engine ready to go all the time because you can go from zero to fifty-five knots, just like that. There's no holding ground for your anchor. Your anchor is just sitting there. The weight of the anchor is keeping you ship in position. As soon as you get a little wind, she starts to drag because it's smooth rock bottom.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine just the effect on the crew out on the deck when the wind picks up.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

There was a funny little thing that used to happen. When somebody would fall over the side in that water, somebody would go in and rescue them. Both of the people who had been immersed in the water would get to go to sickbay and they would get a little bottle of old Overholt rye. We used to call it “old overcoat.” It used to be a racket I think. One guy would jump in and the other one would jump in after him. Then they'd come back up and get two shots of whiskey.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was a problem of men overboard?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

No, this happened a couple of times. They used to kid them about it. One fell in and the other one went after him by design just to get a little shot of whiskey. The doctor

was pretty careful about that sort of thing. There was very little to do up there. We had a club for the officers and a club for the enlisted men. But what can you do in a club there? There's nothing to do except go ashore, have a drink, and come back to the ship. It was terrible.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was commanding the AMMEN at this time?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The AMMEN was commissioned by a guy named Joe Daniels. He was sort of a figurehead because he went on to greater things. A fellow named Henry Williams, Jr., was the first skipper. He was out of the Class of 1931. Here again, we had a very good executive named Konsalvo(?). He was a Jacksonville boy. Konsalvo(?) ran the ship because Henry Williams was a staff communicator and didn't know one end of a destroyer from the other when he came aboard. It was a case of a very poor selection of command, I think. I held his hand when I took over as executive. He kept the ship all through the Aleutians. When we went back down to the South Pacific, he was still in command. Then he was relieved by a guy named James Harvey Brown, out of the Class of 1936.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know Captain Brown very well. He lives up in Louisburg, North Carolina now.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Well, I can tell you a story about James Harvey and his wedding. Anne, was that his wife's name? Ah, you don't want to put this on tape!

Donald R. Lennon:

Go ahead.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

She was an airline hostess, a nice gal.

Donald R. Lennon:

His daughter is now an airline hostess.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The AMMEN got cracked, as you saw in the pictures, in Leyte Gulf. We came back to the shipyard and James Harvey said to me, “You take the first half of duty. I'm going to get married. Then I'll come back and take the second half of the yard period, and you can then go on leave. We were going to be there for six weeks. Well, in the first place, they had prefabricated the two new watch caps for the stacks. In fact, they prefabricated two whole new stacks. They just lifted the old ones off the flanges and put the new ones on. Instead of being there six weeks, we were only there for three weeks. James Harvey took the first two weeks, went off on his honeymoon, and we worked like dogs. I arranged a reception for him after he came from his wedding. I think I got two days out of the whole mess.

Donald R. Lennon:

He owes you one.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Furthermore, I financed the reception for him and he never paid me a nickel. I think it was just an oversight on his part. How do you go up to your captain and say, “Oh sir, you owe me $150.00 for this reception. The officers heard about it in the wardroom and they all chipped in so we spread it out among the whole group. That was really something. James was nine miles high. Whether he's still happily married or not, I have not idea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

We were kind of glad. In fact, he barely got back in time to catch the ship. We had orders to move. I was scared that I was going to have to take the ship out and he was going to have to follow us. He was really in love. They used to raise dogs, too. Didn't she have a couple of pedigree hounds?

Donald R. Lennon:

That I don't know.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

When we finished the Aleutians in that eight months, we made a high speed run down to Milne Bay, which was the big base in southern New Guinea. We were part of MacArthur's Navy and Admiral Barbour's Navy all the way up the New Guinea coast to the Philippines. We hopped from Fingchhafen to Wewak, Halmahera, Biak, and Sansapor.

MacArthur was a very, very good commander in many respects. He had a good staff because they figured a way to really keep the Japanese off balance. They were doing this hedgehopping bit and they would always jump to where they could trap a whole bunch of Japanese and force them into a coastal barge evacuation. Then they had the PTs come in and hit the barges. We used to support the PTs. We had these night PT operations where we would use our surface radar to vector them, just like aircraft. We'd stand off the coast about six or eight miles and they'd be on our quarter. We'd see some movement and we'd just give them a course to intercept. They would go booming in to illuminate. We would tell them when they were practically on top of them, because they were going in blind. We were just like fire directors. They'd hit the barges with their machine guns, then the shore battery would open up on the PTs, and then we would open up on the shore batteries. It was a move, counter-move, counter-counter-move. It was very effective. The problem was that we were up all night and we didn't get to sleep all day. After about three weeks of that, they'd just have to take us off the line, put us out to sea, and give us a little rest. The crew just got exhausted--officers, men and everybody. We were living off of coffee, cigarettes, and Benzedrine. The doctor used to pass these Benzedrine inhalers out just to sniff, to keep us awake.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's dangerous.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

It's bad stuff, I know. But we did it and survived somehow. There are a lot of stories about Leyte Gulf. We happened to be the division that was selected to escort MacArthur's flagship, the NASHVILLE, so we missed a lot of the fun. We missed the big battle off Sumar at Leyte Gulf, where the battleships came around from the south you know. We were in a great big curve and we just decimated their force when they came up through. Our division had the highest anti-aircraft gunnery record and he wanted our division as his escort for ASW and anti-aircraft. Here we were, we were sitting there, and four ships with no expenditure of ammunition, all our torpedoes and everything else. All these other guys had been down to these big battles and fired all their torpedoes and used up all their ammunition. They called us the “untried virgins of the fleet.” Then, of course, came the big air battle when we got cracked by a kamikaze.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you when the kamikaze came in?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I was in combat. I was the executive in the evaluator, CIC. It was not where I wanted to be. I wanted to be on the bridge, but we had just gone over to complete use of the radar. Now the captain goes in there, but in those days, the executive went in there and the captain manned the bridge. In effect, he was conning the ship, and I was fighting the ship. I directed the battery to incoming flights. They would pick them up visually on their fire-control radar. We were firing at this guy all the way in. He was a twin-engine Frances torpedo plane. He dropped his load at the main body and was coming off over the fleet and we were out here on the circle about five miles out, or five thousand yards out from the center. He came to our disengaged side, our Fleet side. We were shooting at another airplane out that way and our light machine guns and forties came working on this guy coming in. They had shells bouncing off his engine cowlings, but he still bore

right through. One engine went through each stack and the fuselage was in the middle. The impact sheared the wings off the engines. You saw what they did to the stacks. The rest of the airplane fortunately went on over the side and exploded. We had a lot of flash burns from the exploding gas. We didn't have any fire on the ship because the momentum carried it all off.

Donald R. Lennon:

It had it blocked there.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

We would have been a disaster if it had not. He was aiming for the bridge. They always try to get the bridge. The CIC was right under the bridge. If he hadn't veered off and hit between the stacks, the ship would have been a total disaster.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had they just started using kamikazes at this stage of the war? You think of that as happening later on in the war.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

This was not a true kamikaze. At the battle of Guadalcanal, I was in the HULL. There the planes would come in and attack. If they got hit, instead of ditching at sea, they were trained to try to crash, thereby making a bomb out of themselves. That was the first of the kamikazes. This was a kamikaze of the same kind. Later, they had kamikazes, which were very cheap airplanes. They were mass-produced, just flying bombs. It was just a one-way trip for them. Those were the guys that they call the “divine wind,” the kamikaze. They were designed as kamikazes. Those guys hit in Okinawa. When I say kamikaze that was just a guy who knew he was going to crash. He had been hit, his engines were gone, and so he just picked out the nearest ship and whammed him.

We got back to Manus and I was in on the initial landing there, the Admiralties. When we got back to Manus, that ammunition ship had just blown up in there. That was

the one that tossed the four-thousand-pound anchor about two miles inland. The ship alongside just disappeared. The WHITNEY was a full-sized large ammunition ship that just completely detonated. Boom!

Donald R. Lennon:

With both of your stacks so severally damaged, was the AMMEN able to move under its own power?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Just barely. Those stacks are designed to take air in to great big registers on the side and there's an inner and outer casing. The air comes in between those two casings and is pre-heated, which gives you a little better boiler efficiency. The intakes on the side of the stacks were damaged, so we had to just cut all that stuff away. We were taking air right into the blowers without getting any preheating. Then, of course, your stack draft gives you a little better combustion because of the rising gases and the acceleration just going up the stack. We lost that effect so the efficiency of our boilers was way down. We had an awful lot of back draft. The watches in the fire room could only stay in for about an hour at a time and then they had to be rotated because the air was so fowl down there. Then we had a terrible time at night screening the lights, because we had to keep everything open. We were taking air in right through the hatches. We had to rig screens over the hatches to darken the ship at night.

We were not an effective fighting unit. We were just capable of self-mobility enough to get us back home. They took a lot of our crew off and put them on ships that were short handed. That left us with just enough people to get us back for repairs. Just at the end of that repair period, which is when James Harvey got married, we had orders for Okinawa. I had read the OP Order and it was all ready to go.

Then my relief showed up, but James Harvey didn't want to let me go. He didn't want a fresh caught executive on board going out on a big operation like that. He fired off a message that said, “Unless otherwise directed, MacMillian can stay with me until we finish this operation and break in his new relief.” The orders came back, “Detach immediately.” I left the ship at Pearl. They put me in “irons” for a while because I had this top secret OP Order in my head and they were afraid that if I went back on a civilian ship, which is what we were using-- those “C” class cargo ships for transport back to the coast--that I might talk in my sleep or something like that. They put me on the Fourteenth Navy District staff for two weeks until after it was over.

I had a funny job there. They didn't know what else to do with me so they gave me the job of designing a smoke defense plan for Pearl Harbor. We still thought, in those days, that the Japs might, in desperation, rig another attack. This was crazy because I had no knowledge, no background, no nothing in this field and I had to go down and start reading about smoke generators, smoke boats, smoke pots, and effective wind--how much wind you can have and still have a plan be effective. In those two weeks, and it's still probably on file there somewhere, I wrote a complete smoke defense plan for Pearl Harbor that included information about locations to plant the pots depending on where the wind is and where to run the smoke boats if you couldn't run shore based you had to run generators on boats. It was a funny thing. I got a commendation for something that was never tried, so I don't know if it would have worked or not. It was just a funny little interlude there.

Then I went back to the coast on a cargo ship. That's where I learned “How they Paint a Deck on a Civilian Ship.” I was standing on the bridge one day, and a seaman

came up with a five-gallon bucket of paint in one hand and a new swab mop in the other. He kicked the paint over, took the swab and pushed it around and that's the way he painted. There was paint running out the scuppers and I told the captain, “That's very wasteful isn't it?” He said, “Well, paint's cheaper than labor.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, but he had command of labor there. They weren't going anywhere.”

Oscar D. MacMillan:

One of the stories, I don't know if it was ever told or not, concerned the pay and the privileges that merchant seamen in the war zones got--what they call an anchor bonus. Everyday that they were anchored in a war zone in a port, they got a hundred-dollar bonus, over and above their pay. When they were under way in a war situation they got bonuses. That ship didn't have enough seamen on it to do anything. That's why, when they wanted to paint, they painted rough and ready. That was an exaggerated circumstance, but it was a true story, it really did happen. The captain said, “We don't have the manpower and we couldn't pay them if we did. Paint's cheap, so that's a quick way to paint the boat.” Instead of having ten sailors with paint brushes and spending the morning, this one guy kicks over a can of paint, pushes it around with a swab, and that's it.

I put CLYDE B. PARKS in commission as an executive. Morgan Slayton was my skipper. He was out of the Class of 1933. My job on that ship was to take the balance crew and put them through the shore-based training in Norfolk, the location of all the schools for various skills. The balance, or nucleus, crew went to the ship, the department heads and all the petty officers, and oversaw the outfitting of the ship. So we joined together at the commissioning and then went into the shakedown. We commissioned in

May 1945. Then we went down to Guantanamo Bay for our training. We just didn't make it through the Panama Canal by VJ Day.

When we came back up the coast to San Diego, after going through the canal, I had dispatch orders to take command of a destroyer escort, which was out in Guam. There again, Slayton didn't want me to go, because the next senior officer who would become the executive was the chief engineer. He was a limited duty officer and had no executive experience or administrative experience. He was just an engineer, although he was a darn good engineer. It dropped down to a fairly junior communications officer to Fleet-up to be the executive. I was very happy to stay on as the executive. Well, I wanted my own command actually, but he fired off a message to Washington there and got another, “Detach immediately without delay.”

They flew me all the way out to Guam. When I got out there, it was ridiculous because the ship was in drydock. It was the CROSS 448. She was a steam-geared turban DE. Her captain had been moving from one berth to another in Buckner Bay and Okinawa and neglected to go around a little reef that stood in the way, so he made a three point landing on the reef--sonar dome and both propellers. They had towed the ship down to Guam and put it in drydock and there it sat. The captain was allowed to resign without court-martial because it was an obvious inattention to duty. The navigator was fired. The terrible thing about it was, in the demobilization process, it had moved to a point, when I got there in December, that they were no yard workmen available. They had all gone home. There were very few sailors available, skilled yard-type sailors or drydock workers. Here was this ship with two bent propellers, two bent propeller shafts, and a damaged sonar dome, and nobody to fix it. It was a terrible problem.

The solution turned out to be that there were a lot of people ashore, senior petty officers, chiefs that were first class in all ratings, who had been there on duty and who wanted to get on but had no transportation. There were masses of people but no way to move them. They had the “flying carpets” going you know. They took carriers and put cots in the hanger decks. They were carrying people back on anything that would float. We went ashore, my exec and I, and we recruited enough machinist mates and other skilled mechanics and got them to agree to sign on with us. I would take them on as crew and give them transportation.

Donald R. Lennon:

You could do that--pull your own crew together?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

You could do almost anything in those days. It was mass confusion. It really was. We went up in the yard. We found two shafts the right size. We found two propellers the right size. You just can't imagine what Guam was like. Guam had been built up for the final invasion of Japan. We managed to scrounge enough material to put in the two shafts.

Donald R. Lennon:

You repaired it yourself!

Oscar D. MacMillan:

The ship's company did. We cut off the sonar dome, put a flange up there, and welded it up so it was watertight. Then, this is one of those unbelievable stories: We were coming down the homestretch with the CROSS when I got called up to the headquarters by Combat Marianas Operations. “We've got a destroyer escort, the HEYLIGER 510, that's up in Iwo Jima. Her captain has points to go home and the executive's not qualified for command, so we want you to go up there and bring that ship back down to Guam. I said, “But my ship's in drydock and I'm almost ready.” They said,

“Well, just leave your ship at drydock and go up and assume command of the HEYLIGER I didn't get relieved of the CROSS either. I was still in command of the CROSS.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were commanding two ships at the same time!

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I was flown up to Iwo Jima and here was this poor little old ship, same class of ship as the CROSS, in perfect operating condition. (I had to get a ride out in a barge, in a LSM--a big heavy-duty landing craft. I got the CB to run me out.) As I went out the captain was leaving with his luggage and he just waved to me, “Bye-bye!” He didn't even come back out. When I went aboard the ship, I found out that she was out of fuel and on a lee shore, dragging anchor toward the beach. The poor executive was beside himself. The first thing I said was, “I'm going up the focsle. This ship feels like it's dragging anchor.” You could put your hand on the anchor cable and you could feel the anchor rumbling on the rock bottom. I said, “Let's get steam up and get this thing out of here.” He said, “Sir, we're out of gas. We have no fuel.” It was a curious sequence of events. It wasn't really anyone's fault that they had run low on fuel. It was just that there was none available. The tankers just weren't available to refuel her.

I said, “Do you have any diesel on board?”

They said, “ Well, we have the diesel generator tank.” They had five thousand gallons of diesel in that, so we pumped that over into one of the service tanks, lit off with diesel, which you can do if you put the right size burners in, and got underway and off that beach. I'd rather be drifting around at sea than drifting up on a lee shore.

We put off a message saying, “Urgent, requiring fuel!” They sent a little YOG down from Haha Jima or one of those little places. We fueled and got down to Guam. Then I put the ship alongside one of those concrete oil barges that they had there as an oil

dock. They were fueling the HEYLIGER while I took the CROSS once around the island to see if the shafts would work and the sonar flange was tight. I then brought the CROSS in alongside the other side of this fuel barge. While they were fueling the one, I went up to Combat Marianas and asked, “Which one of these ships do you want me to take?” They said, “Take both of them!” The CROSS was fueled, so I took her out and pointed her toward Pearl Harbor and turned her over to the executive. Then I came back to the HEYLIGER and got her underway, formed Column and we went back together. They met us off Pearl Harbor with a new captain for the CROSS. I made a transit from Guam to Pearl in command of two ships at the same time. I don't know whether that has ever happened before or since. Then the ship joined the other two of the division and we had a four-ship division.

We went through Panama. That was an interesting experience too because the pilots in Panama were in short supply. The rule is that you have to take a pilot through the canal, no matter what size ship. We were four ships and they locked us through, moored side by side and two at a time. We had a pilot on one and not on the other. Then when we got out of the dock, we went through the lake in a column and I had no pilot. I went through the canal, literally, without a pilot on board which, also, is an unusual situation. It was fun, too.

To get ready to go into the dock, we had to moor underway. We had to come alongside of each other and put the lines over while we were still doing five knots. That's a strange feeling. Five knots is like a stop. To get in you have to increase speed, but instead of stopping to go alongside, you have to slow to five knots. It's a tricky little maneuver. I had never done that before.

They sent us to Boston and we did pre-decommissioning overhaul in Boston. I got married to the girl I had met down in Australia, the USA Army nurse. Then, we came down to Green Cove Springs, right over here across the way and went out of commission.

That was another story. It was March and April of 1946 and there was just mass confusion. All these ships were coming down. Some were pretty well ready to go out of commission and some of them were not at all ready to go out of commission. There were very few people to work with. In the midst of all that confusion, I got orders to go to shore duty to PG school. That was the end of the war as far as I was concerned. For me, the end wasn't VJ Day, it was the day I left my poor ship there in Green Cove Springs. Have you ever been up the St. John's River?

Donald R. Lennon:

A little bit, not a great deal.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Well, you know, it's very shallow. We were pushing through mud. I'm sure we were a ground most of the time all the way up. We had off loaded everything to get as light as we could; all our fuel and all our water.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were using it for a lay-up basin?

Oscar D. MacMillan:

They moored six ships in a nest. They were arranged bow to stern. There were three upstream and three downstream. Then we put six anchors out from each end of the nest. Those anchors had to be hauled out. They would take a tug and a chain. They had a little tug with a special billboard, or anchor board, on the back. You would lower the anchor on to that board. Then they would take a piece of cable and they'd haul the anchor out, slip the cable, drop the hook, and then fan out from about forty-five degrees to dead ahead. There were six anchors upstream and six anchors downstream. To show you what

kind of bottom it was, any one of those anchors could wench in right through the mud. They didn't have much holding power.

Donald R. Lennon:

I remember . . . we had a lay-up bow from Wilmington, North Carolina, and we had a lay-up base for the Liberty ships there in the Brunswick River. Every so often, one of them would break loose and come down the river.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

You know how we cocooned the ships? That was the final step. The guns were cocooned with plastic and then they evacuated the area and put nitrogen or some inert gas in. Actually, that system worked pretty well because they reactivated some of those ships. They were quite successful. I don't think they have any more of those ships over there. There's no more reserve fleet over there in Green Cove Springs, is there?

Donald R. Lennon:

I don't think so.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

Then I went off to intelligence school and became a PG in intelligence and a Russian language student and got my ticket as a translator and interpreter. They sent me off to be the intelligence officer down at the amphibious base at Little Creek. I reported down there in the fall of 1947. I was there for about three years. I was about to be ordered back up to the Officer of Naval Intelligence as a Russian background officer when I went to Washington to see if I couldn't get back to sea. I figured that after all this time . . . I was at the intelligence school for a year and a half as a student, and then they kept me on the staff for two years as an administrator, and I was the guy in charge of the language school.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had land duty for three and a half years.

Oscar D. MacMillan:

I was afraid that if I didn't get back to sea, I would wind up being just another shore stiff. I wanted command of a real destroyer. I went up to Washington to appeal these orders.

[End of Interview]

This is my grandfather. Thank you for this history.He died about a year after this from lung cancer, when I was 8, so I don't remember his what his voice sounds like.