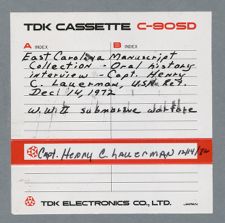

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Captain John Henderson Turner |

John Henderson Turner:

My father was a naval officer from Georgia; my mother was from Vermont; and I was born in California. I did not live there very long; actually, about six weeks. Most of my childhood was spent in Hawaii. I went to a preparatory school at Annapolis, entered the Naval Academy in 1932, and graduated in 1936. I went to the USS CHICAGO as a new ensign and served on the CHICAGO for two years in the Pacific. In May, I guess it was, of 1938, I went to submarine school in New London, Connecticut, which was a six-month course. It was the first class that my class could go to, because in those days an ensign had to serve two years in a big ship where he was trained in all of the various departments of the ship--to learn how to be an engineer, and a gunnery officer, and a catapult officer, etc.

As an interesting sidelight, there were four in my class--myself and three others--and of those four, I was the only one who survived the was. The first one went down on the SQUALUS and the other two were lost in combat. I am the last surviving man in the class or the oldest surviving man.

I was ordered from submarine school to the USS SCULPIN, which was being built in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. I reported to the ship just before Christmas of 1938, and I believe in May of that year, we were to sail on a shakedown cruise to Valparaiso, Chile, and Callao. When we were leaving the port at Portsmouth, we sighted a red smoke flare which is a signal that a submarine is in distress. It was the SQUALUS. So instead of

going on a shakedown cruise, we stayed for the salvage of the ship which took almost six months.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had the SQUALUS been hit by a torpedo or was it ... by some other...?

John Henderson Turner:

No, it was an operational accident. One of the valves in the ship, in fact the biggest one in the ship, that let the air into the ship for the engines to run on, was left open on the dive. They were practicing; the ship had just been recently completed, and they were going through builder's trials. There was a little faulty design but mostly personnel error, I think. The two engine rooms and the after torpedo room flooded immediately. They got quite a few of the people out, and I have forgotten exactly how many, but approximately twenty-five or so were lost. Then the SCULPIN stayed at the shipyard after that because they wanted to redesign the same valve on our ship; we were sister ships.

We left Portsmouth on the second of January, 1940, and we went down to Norfolk. The temperature at sea was very low. In fact, Chesapeake Bay was frozen over. We were supposed to go to Annapolis, and we couldn't get up to Annapolis because the Bay was frozen; so we went and did some experimental work with what was then considered to be quite new plastic paint for the ship's bottom, anti-fouling paint. Then we went into the shipyard at Portsmouth, Virginia, and had this applied and then went down to Key West, Florida. At this time, of course, World War II was going on in Europe, and the submarine going along the coast of the United States was not a very welcome thing. So we had to have an escort of our own; destroyers took us down the coast to Key West. We stayed in Key West for awhile and then went down through the Panama Canal to San Diego. There we did normal operations until around February of 1941, when we went off

on a fleet problem that ended up in Pearl Harbor. By this time, I was the engineer of the ship.

We didn't return to the United States. The Fleet stayed in Pearl Harbor. This was one of the decisions that subsequently had been sniped at--not bringing the fleet back and getting it away from Pearl Harbor. Anyway, we stayed there and operated out of Pearl Harbor for about a year. Then I was married in July of 1941.

In October, we received secret orders one Sunday and sailed on Monday for the Philippines. The whole squadron did, and the submarine tender with us. We arrived in the Philippines in November and operated out of Subic Bay and Manila Bay for about a month, and then the war started. Of course, in the Philippines, eight o'clock in the morning in Pearl Harbor was still the middle of the night in the Philippines, so we had warning before daylight that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Ships were all dispersed in the Bay, anyway, because of the very tense international political situation, and we could see the Japanese planes attacking Clark Field. But they did not come after the shipping in the harbor, at least not while I was there. Our ship sailed that night, which was December 8, on a war patrol. We patrolled east of Luzon and north of Luzon for about forty days without success.

In early February or late January, we headed down the east coast of the Philippines to Borneo, where we were to get fuel at Balikpappan, and then to Leyte. East of Leyte, we did run into a Japanese convoy and sank one ship. The whole attack took about five minutes because we didn't know what we were doing. We did hit a ship however, and it was subsequently proved to have been sunk, but it was pretty confusing.

We went to the Balikpappan, where the Dutch mined the port, of course, and had all of the refinery and oil tanks ready to blown up. The next day the Japanese came in and landed there. We did not see them as we were ordered further south in Makassar Strait. About a week or ten days later, we went into Surabaja in Java to get torpedoes, fuel, and food. The food was different from what we were used to. Instead of having the frozen meat come down, they brought the cow down and killed it right at the dock. They slaughtered it right there and brought the hot meat aboard. We tried to freeze it, but it didn't last very long. We lived on canned goods most of the next patrol, which was over east of Celebes, the Dutch East Indies.

We patrolled off of a small bay called Staring Bay, and we ran into the tack force and the troop convoy that was going to invade Java. We shot one destroyer and then got into the real depth charging, our first real hard tough depth charging that I'd ever been through. We patrolled in that area until mid-April, approximately, and we then went down to Exmouth Gulf on the coast of Australia. The submarine tender that had gone from Honolulu to the Philippines with us had gotten out of the Philippines all right and was down there. First it had gone to Port Darwin, but the Japanese attacked there, so it got out of there and went down to Exmouth Gulf, which was very isolated. The day before we got into Exmouth Gulf, we were running submerged and heard on the sound gear propeller noises and looked up, and here was a Japanese submarine. We took a shot at it but didn't hit it. We reported that we had been in this, but the message got a little mixed up, and they thought somebody had shot at us instead. When we got to the tender, we had to tell them that it was that had shot at the Japanese submarine.

We all moved out of Exmouth Gulf and went down to Fremantle, Western Australia. We had about four or five days there in which we got some torpedoes and fuel and food and then sailed up into the South China Sea for about two months. We got back to Fremantle and shot at one tanker near Balabac Strait, which is south of Palawan. We went over off of Saigon, what we now call Saigon, and patrolled along the coast of China, but we never found any ships. Of course, all this is before the days of radar. Everything was kind of basic.

We sailed back to Fremantle. We had been at sea since December essentially. We had been into Balikpappan overnight, Surabaja for three or four days, and in Fremantle for about five or six days. The crew was exhausted. I weighed 138 pounds when we got in, and my normal weight was around 188, so we were pooped. They realized that we needed a rest, so we got two weeks. We went down to Albany, Western Australia, which is in the southwest tip of Australia, where the tender was. There were still Japanese submarines and there were rumors of Japanese carriers. However, it wasn't too long before the battle of Midway, and we knew carriers weren't down there anymore. After this refit, we went back to the South China Sea again. The time was so long ago, I can't remember, but we did shoot at some ships. I don't think we sank any, but we did hit them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Perhaps right here would be a good place for this particular question. Torpedoes, early in the war, were supposed to be notoriously faulty. Was this part of the problem?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes. Part of it was a bad exploder. The exploder was magnetic, and as the torpedo left the ship, it would dive and accelerate. It had a pendulum in it the helped keep its position--its level position--in the water, and as it accelerated, the pendulum would go back. The torpedo would dive down to forty of fifty feet and then come back up to the

depth at which it was set to run at. A lot of times, this vigorous change in depth and position of the torpedo would actuate the magnetic exploder so that as soon as the exploder armed, the torpedo would explode, which would be about four hundred yards from the ship. It really gave you quite a whack when it went off. I was not dangerously close because the built-in safety factor would not let it arm until it was far enough away where the explosion wouldn't hurt the ship, but it would rattle your back teeth a little bit, and you knew what had happened. But we, much against orders, avoided the problem by deactivating the magnetic part of the exploder, so it had to hit something to blow up. We weren't supposed to do it, but having been told what was causing the problem, we figured the easiest way to solve it was to get rid of it. We did this on our own, and nobody ever got a court-martial or anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, didn't they later do away with the magnetic concept?

John Henderson Turner:

No. What happened was that they lest the magnetic concept in and perfected it a little bit so that it would work, but many people wouldn't use it. They's set it to hit. You see, with a magnetic exploder, you are supposed to shoot it underneath the ship, and if the keel depth you figured was forty-five feet on a big ship, it was to set for fifty-five feet. Then as the magnetic field changed with the torpedo going underneath the ship, it would explode the torpedo and break the ship's back. So one torpedo could do a tremendous amount of damage. People had little faith in this after their original experiences. There was another fault in the torpedoes which was corrected later. The exploder mechanism is a ball on a plate, and when the torpedo hits an object, the ball trips off the plate, allowing a spring to push two firing pins up into a very highly explosive mixture, which explodes,and then the detonator would explode a torpedo warhead.

Well, these little firing pins were breaking off when it hit. Of course, if you're going from forty-five knots or fiftymiles per hour, it is like hitting a stone wall. And these little pins would shear and the torpedo would fail to explode. And this caused a loss of faith in the torpedoed, too. But it was solved by a real simple thing, by changing the metal the little firing pins were mad of. First of all, they took torpedo warheads and fired them at a cliff in Hawaii, until they got some thay didn't explode. Then some brave young man went down in his diver suit and recorded the explolder. This was part of the problem.

But anyway, to get back to the SCULPIN, we made another war patrol in the China Sea and came back to Albany and had two more weeks theere. Then we went around to Brisbane, Australia because the Guadalcanal campaign was getting underway pretty well then. And we went up off Rabaul and patrolled there for approximately two months. We shot all of our torpedoes,a nd we did sink some ships. We also got beat up a good deal, too, because a lot of the Japanese Navy was there protectin the convoys and ships coming into Rabaul from the north. And then we went back to Brisbane and had about a week or ten days there and then back to Rabaul again. This was the sixth patrol of the SCULPIN, and we had been told that we would be sent home, as we were a relatively old polar submarine by then and didn't have any radar, as I said.

So, we went and worked off Rabaul for about a month and then went up off of Truk, and stayed there for approximately three weeks. We saw a couple of Japanese carriers but never did get a shot at them. Then we ran back to Pearl Harbor. I left the ship. Then went to the San Francisco Bay area where it was to be overhauled. The skipper of the ship and the executive officer of the ship were ordered off the day we got back to go onto a new ship. So, I was a month late leaving the ship, but I did go to a new ship, the

Ray, which was built in Manitowoc Wisconsin on the shores of Lake Michigan. They built about twenty, I guess.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then float them out the Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway?

John Henderson Turner:

No, they came down to Lake Michigan at the foot of Lake Michigan and through the Chicago Drainage Canal to Lockport, Illinois. There it was put in a dry dock and a pusher tow down the Illinois River down to the Mississippi River to New Orleans. Half of the crew would go on the submarine, and the other half would go down to New Orleans by train and meet the ship down there and load all the supplies aboard because we had very little when we came...

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this the easiest way to...

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, in fact the St. Lawrence--I'm not sure of the facts, but it was the easiest and the most practical way. In fact, quite a few ships were built on the Great Lakes and came down the Mississippi up to and including the “A-K-A”, which is a pretty fair sized ship. They had pontoons and things that they had to raise the draft to something; I think there was a guarantee at one place on the Mississippi River that the Army engineers could guarantee ten feet of water, and this was the limiting factor to get down the River. So, we had about from April of '43 until August of '43 in Manitowoc. Then we went down the river and loaded up and went to the Panama Canal Zone and trained on the Pacific side of Panama Canal Zone for all of the things that you do on a submarine, all of the emergencies, all of the battle tactics. I was a second on this ship, and we also had radar, which mad life a great deal simpler in the fire control part of it and also in finding targets. We sailed from the Panama Canal direct of Brisbane, Australia, which is a long haul.

This took the better part of three weeks because you couldn't go fast; you had to have enough fuel to make it all the way through.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now are you on the surface?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, we stay on the surface. We used to dive once a day to get the trim so the ship would be in readiness in case we had to dive for something. But we ran at the most efficient speed we could. And there's a side light; a couple of submarines ran out of fuel trying to do this, and they had to burn some of their lubricating oil instead of fuel oil and mix it with fuel oil, and this would cause mechanical difficulties. But we made it all right. We had something like one percent of the fuel left when we got back.

Donald R. Lennon:

They did that rather than sending a fueler out from Australia?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, submarines are not the easiest things to fuel at sea, although the Germans did it with some success in the South Atlantic. Submarines are a very tender ship; propellers stick out and there are no guards or anything much to protect them, and the tanks are not very protected. There is a pressure hull, but outside of the pressure hull is all fuel tanks and ballast tanks. So you had several choices along the way where you could stop and get fuel if you really had to. You could stop in New Zealand. You could stop in the Galapagos Islands, but that was too early for most people. But we made it with no difficulty and then went up to Rabaul again, and this was November of '43. Things had changed a good deal around Rabaul because the United States had gotten control of the air, and a lot of Japanese Navy had been either sunk or driven away from the general area. There was still a lot of small craft around. We sank one ship in a convoy. By this time, we were using what the Germans call wolfpack tactics, and we worked with two other submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

Earlier you had been alone, had you not?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, it was strictly alone. You see, with better communication and radar, you can do a lot of things, and the wolfpack tactic was a good thing because once you shot at some convoy or in those days, once you shot into a convoy, the destroyers would come over and would depth charge you, and you lost contact with the convoy. But with the wolfpack, one fellow's job is to maintain contact with the convoy, and the other two take turns attacking, and if one gets held down then the next fellow doesn't attack until the other one checks back in again. So there's always somebody attacking and somebody trailing the convoy so that the convoy doesn't get away.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine without radar it would have been extremely dangerous to have operated in the wolfpack fashion because of the dangers of the submarines getting too close to each other.

John Henderson Turner:

Not down as much as communications being able to talk to each other. Early in the war, we had bred into us all the time that silence on the radio was the best thing, and the German experience was proving it. The way the British and Europeans were finding the German submarines was because they would check with Admiral Doenitz every day. They'd get a fix on them and send somebody to at least harass them. So we had bred into us that you didn't talk much on the radio. The wolfpack tactics required talking on the radio, of course, once you attacked a convoy, they knew something was there and breaking radio silence. The benefits are greater than the things you lose. We worked up off of Truk on this patrol also, and we didn't see anything but a big hospital ship which went on and we took pictures of and that was all. Then we came back down to the eastern tip of New Guinea to a place called Milne Bay where our submarine tender was,

and we went in there and got some torpedoes and fuel and food and stayed about three days, I guess, and then sailed through Torres Strait, which is the strait between New Guinea and Australia and where Captain Blythe went through on his way back to Timor after he sailed with his loyal members of his crew. So we come to Monday Island, Tuesday Island, Wednesday Island, Thursday Island, Friday Island, and Saturday Island and then you're through the strait. It's all coral, and it's pretty tricky getting through. We went up along the south side of Timor and through a small strait and up into the eastern part of the Celebes where we did find a ship through intelligence being sent to us and sank it. We then went down to Fremantle, Australia and replenished at Fremantle and got some rest. Then we went up to the South China Sea up east of Java and through Makassar Strait and through the southern Philippines and through Balabac Strait and into the South China Sea where we shot at some ships in a convoy and tried to form up an informal wolfpack with another submarine. We started up in the northern part of the dangerous grounds which is the eastern part of the South China Sea. And we chased the convoy all the way down almost to Singapore. It took about four days and four nights. The other submarine got three ships, but we didn't get anything but depth charged. We kept getting detected every time we tried to get into, but most of these attacks were at night on the surface. You operated the submarine like a PT boat almost--ran in at high speed and fired torpedoes and turned around and came out. You could do this with radar at the surface. With radar you could get a good solution, of course, and speed and if they were zig-zagging, you could tell when they were zig-zagging and get in. At this time, too, submarines were painted a haze gray, and all of the spots on the hull above the water where a shadow would show were painted lighter than the haze gray so that at night it all

blanked out, and the submarine was very difficult to see on the surface at night. So you could just point the bow at ships, and they wouldn't see you. If they had radar, of course, you were in trouble, but we had radar and the Japs didn't for this period of the time in the war, and it gave us a great advantage. So we came out of the South China Sea through the Straits west of Borneo, which were known to be mined, and that wasn't a very comfortable feeling to go through there, but we got through there with no problems. We went across the Java Sea, and we ran into some small native sailing type ships carrying supplies, so we shot them up with a gun and then came down east of Surabaja to go through Lombok Strait. East of Surabaja there were some islands whose name I have forgotten, but I never thought I would because we ran into four destroyers coming out of Surabaja in a column' and we shot at the last one in the column and hit him, but the other three worked us over for twenty-four hours. We got beat up pretty bad. And we thought we were heading east, but the currents had taken us south through Lombok Strait. By the time we found out where we were the next night--we surfaced, we couldn't see any land, and we knew that was wrong because there was supposed to be land around, and we had to turn off all of the machinery on the ship to keep from making noise to get rid of the depth charging destroyers. The periscopes had been broken, and the compass had been broken, and so I was the navigator at the time, and we had to find out where we were from the stars. To make a long story short, we were about a hundred and twenty miles from where we thought we were, and we were in the Indian Ocean, and we weren't in the Java Sea. We had gone through the island chain without knowing it; the currents had carried us through. Then we went down to Fremantle, and I was detached from the ship and sent back to the States to be skipper of the U.S.S. Seal which was an older submarine.

She was being practically rebuilt at Mare Island, and I got there about a month before she was ready to sail. We went from Mare Island to Hawaii and trained in Lahaina Roads close to Kaiwi, one of the outlying islands, then close to Lahaina, excuse me, the Island of Lahaina. Then we sailed and went up the Island of Honshu off Japan and patrolled up there and sank a ship and then were ordered to the Kurile Islands which we patrolled. This was in August of '44, and we ran into a convoy coming off of La Perouse Strait headed for Paramushir and then about two nights we stayed primarily, shot all of our torpedoes, and came home to Midway Island where we had our rest period. Then we went back to the Kurile Islands again where we sank two ships and then back to Pearl Harbor. Then I was ordered from the ship and became the operations officer for a submarine squadron that was forming up in Guam. This was about Christmas time of 1944. I had this job, I was getting pretty tired by then. I stayed in Guam until about March, early March, the first of March, I guess it was, of '45 and was sent back to Manitowoc again to be a skipper of a new submarine that was just being completed there. We got there in the middle of March, and we were to sail, I think, in August; the reason I remember that is because it was my birthday. Of course, on the fifteenth of August, the war came to an end, so our plans were changed. Instead of leaving the Great Lakes, we stayed on the Great Lakes until after Thanksgiving and sailed all over the Great Lakes from as far east as Cleveland and as far west as Duluth and Superior and many other towns in between.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that was a strange sight seeing a submarine sailing around on the lakes.

John Henderson Turner:

It was, but part of it was a publicity thing. The war was over and to let people see what a submarine looked like. Having been built there in the middle-west, too, this was an added factor to showing the people what some of their laborers had been doing. Then we went down the Mississippi again and to Panama where we were for the Christmas holidays. I had left Mrs. Turner in Manitowoc. I had told her to stay there because theoretically, the ship was to go Guam and stay a year, and she couldn't come, and we then had a small son, I guess he was about a year old then. He was born on Christmas Eve of 1943, but I didn't find out that he had been born until March. We sailed from Panama for Honolulu, and then we were to go to Guam. Just before we got to Honolulu, we found out the ship was to be decommissioned, so we took the ship back to San Francisco. I called Mrs. Turner from Honolulu and said, “Get to San Francisco, baby and everything else.” This is typical Navy life, though. And she did. We stayed in San Francisco for about then I was ordered to command another submarine, the Boarfish, which was stationed in San Diego. This was a very hurry-up set of orders; I only had forty-eight hours from the time I received orders until I had to report to the submarine.

I was on the Boarfish until 1948; operations on there that were of interest were a cruise to China, to Chingtau, and to Okinawa, and a cruise up to the Aleutian Islands and up under the ice in the Arctic. We were the first ship to do this on the Pacific side. We stopped in Alaska for awhile, and then in late '47, the ship went to the Navy yard. We found out the ship was to be turned over to the Turkish Navy in Turkey, so we took off a lot of the more sophisticated equipment and replaced it with some that wasn't quite so sophisticated. We sailed about April, I think of 1948, through the Panama Canal to New

London and picked up Turkish officers, petty officers that had been there training in a submarine school. After several delays we sailed for Turkey by way of Malta and Argostolion, Greece to Izmir, Turkey. We couldn't go into the Sea of Marmara because, I forgot the name of the city in Switzerland, but anyway it's the Montreux Convention which doesn't allow the U.S. or Russia to keep ships of war in the Sea of Marmara. It was going to take a while to get it turned over, so we stayed at Izmir for a couple of weeks and then part of the crew remained with the Turks. Everyone was a volunteer that remained, but I wasn't a volunteer because I had had twelve years at sea, and I was ready to go ashore.

So I came back, and I went to duty at Dartmouth College where I was Associate Professor of Naval Science for two and a half years. A very delightful tour of duty and very educational for me. Then I became the operations officer and later division commander of the Division of Submarines in Key West, Florida. After that, I went to the Naval War College and then to the Pentagon where I was in the Political Military Affairs division of the Office of Chief of Naval Operations. This was an extremely interesting tour of duty because it was the liaison office of the Navy with the State Department and all sorts of fascinating things came up, and of course, a lot of politics mixed in it, trying to solve political problems. Fortunately, the war college teaches you a little bit about this, but this was fascinating. From there, in 1956, I went to San Diego and became the commanding officer of the U.S.S. Sparrow, a submarine tender, for a year and then another year as a squadron commander of a squadron submarine. From there I went to Commander and Chief of Atlantic Fleets Staff as operational plans officer, which is where I knew Hank Lauerman. Then from there I went back to the office of Chief of

Naval Operations and was the deputy for foreign military assistance for a year. Then I became a squadron commander in the service force in the Atlantic Fleet and then chief of staff of the service force in the Atlantic Fleet. Then I went to the Joint Staff of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon and then retired.

Donald R. Lennon:

You retired in what year?

John Henderson Turner:

1966.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had a pretty balance between sea duty and land duty.

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, I had about twenty years at sea out of the thirty years in the service that I served after I got out of the academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

In mentioning your patrols and commenting on them, what was the nature of the patrol orders? Were they specific or did they just order you to cover a rather broad area?

John Henderson Turner:

No. You were assigned an area.

Donald R. Lennon:

But that would be hundreds of miles of ocean, would it not?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, it was hundreds of square miles of ocean. For instance, the two patrols I made on the Seal around Kuriles, I had all the area from Jukooko, which is the northern island, I think it is, I'm not sure that's the right name, but Atnephutoe is a small island at the southwest end of the Kuriles, and another thousand miles you come to Paramushir. Everything along those islands was my area and south of them a good deal, too, and everything in the Sea of Okhotsk, which is the sea between the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin in Russia. There were literally millions of square miles of ocean. But you were given the very best intelligence.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many submarines would be assigned to a given area?

John Henderson Turner:

One. Because if you ran into another submarine, you didn't want to have to go through any drill trying to find out if it was friend or foe.

Donald R. Lennon:

Unless you were in a wolfpack?

John Henderson Turner:

That's right. And this was always a very ticklish thing, meeting another submarine that you expected to meet, but you still weren't sure. And you still weren't sure that maybe somebody had broken the code and had sent a third submarine in there.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no way to identify other than radio contact?

John Henderson Turner:

No, if you were going to identify, you usually tried to meet at dawn and identify with a flashing light; both submarines point at each other with your torpedo tubes open and then send your code signal for the day, which was three letters. If you got the right answer back, then everything was all right.

Donald R. Lennon:

You hope, unless somebody had gotten your code.

John Henderson Turner:

No, there were so many ways that you could try to protect the code you got before you went to sea, and they were secure, the identification codes. But things that went on the air, you were never sure, you see. Because actually we were getting pretty good intelligence on Japanese ship movements by breaking the codes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, how frequently were you in contact with headquarters?

John Henderson Turner:

You don't send any messages, you receive messages every night. And usually, as time went on, you learned that if you had shot and disclosed your position, then you sent a message right then because you weren't fooling anybody. And then, you beat it! You went somewhere else in the area.

Donald R. Lennon:

Otherwise, the only time you sent messages was if it was requested of you at headquarters?

John Henderson Turner:

That's right.

Donald R. Lennon:

This lack of proper radar equipment early in the war, this created quite a problem when you were being depth charged, did it not, in knowing how long the enemy was still circling around above you?

John Henderson Turner:

No, radar doesn't work under water, sonar does, and we had pretty good sonar equipment. We could listen and we could ping, too, but you don't want to ping, a submarine doesn't because that discloses his position. But you could listen and hear propeller noises, and with experience you could tell by the loudness of the noise, by the rate of change in bearing, and so on, whether or not these propeller noises were close or far. You weren't always right and sometimes you would come up and be surprised that the ship was so far away. But usually a good sonar operator could tell you at least if he's four thousand yards away or if he's two thousand yards away.

Donald R. Lennon:

I wondered if they wouldn't kill their prop.

John Henderson Turner:

They did this, and it got to be quite a cat and mouse game then, but the Japanese would at times stop everything, and stop and listen. Everybody is very quiet then, and what we tried to do was say that he was there somewhere and point your stern at him and try to creep away.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then he could pick up the sound of your prop...

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, you see, you have a bathothermograph on the submarine which are quite sophisticated now. In those days we just used to watch a therometer and plot it, but the ocean water temperature has layers in it and the sound will, if for instance, the temperature at the surface in the western Pacific someplace is 70 degrees and you go down a hundred feet and it's still 70 degrees, and then in about twenty-five feet it changes

to 65 degrees and it stays, it gradually gets cooler down there. If you can get down below where the break in the temperature is, the sound will tend to stay down below that break in the ocean, the temperature gradient it's called. And so you run deep and get underneath the gradient if you could find one. Grand Truk was notorious that as deep as you could go, you could never find a break, so you got beat up some there occasionally.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, on these occasions where you were being severely depth charged and maybe beat up pretty badly, were you ever in danger of losing control of your movement?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes. I mentioned the occasion of meeting the Japanese coming out of Celebes on the way to the Java Sea. We developed a leak plug in a pipeline in the officer's toilet, and the plug was outside of the sea valve so that there was no way of turning it off. The toilet was in the foreword battery so salt water in the battery produces chlorine. This is one of the fundamentals, that you never let salt water get into the battery. It would force you to surface.

Donald R. Lennon:

Chlorine gas coming out of there?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes. so this was very early in the war, and we didn't have all of the--we learned a great deal through experience. But we took a paint brush handle and sawed it off and drove it into this hole.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was that large a hole?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, it was as big as your thumb, and we were down about three hundred feet depth, and the pressure down there is about one hundred fifty pounds per square inch, so it's really coming in. We bailed the water out of the deck over the battery down into a compartment that had canned goods in it because that was the only place we had to get rid

of it. Of course, the ship was getting heavier all of the time, and we had to speed up and run with a very high up angle to keep from sinking any further. We finally got this plug to hold and got the water flow to stop, but by this tie we were about five tons heavy, and we were running around.

Donald R. Lennon:

And there is no way to discharge that water while you were...

John Henderson Turner:

We didn't want to turn any pumps. You could discharge it, but the pumps made so much noise that you would attract the ships again. So they finally left us, but that was the first real depth charging we had had and that was the first time really that we got water inside the ship that I was on. We'd had damage from shock, but not from broken pipes or something like this. I forgot what the thickness is, but a very high tensile steel was developed just before the war, and then welding techniques were developed early in the war that permitted quite deep depths. I have forgotten how thick the Sculpin's hull was, but it was about three quarters of an inch, something like that, the pressure hull. Most of the submarine that you see is not pressure hull. All modern submarines, anyway, are double hull ships. The pressure hull is the one that has the strength in it, the outer hull is...

Donald R. Lennon:

Can be punctured and do very little damage?

John Henderson Turner:

You leak oil or leak air from the ballast tanks, but nothing at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

For curiosity, you were talking about taking pictures of hospital ships. Is it possible to do that submerged, or do you surface?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, through the periscope. In fact, the technique was developed quite well and used on many of the invasions of islands of the Pacific. The submarine would go and take pictures of the island shoreline, staying on a set course and taking pictures at set

intervals along this course at a set speed, too. So the intelligence people could compute the distance between snaps of the picture and get a stereo-scopic view by overlaying two pictures, one matching the other, and then you could get a depth perception on our monocular periscope.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were speaking one time of the exhaustion from being at sea for a long period of time. Just how did you exercise and relax in the confinement of a compact submarine?

John Henderson Turner:

You didn't. On the Sculpin when we started the war, we had six officers, one of whom was brand new, had never been to submarine school. We stood watches on the bridge two hours on and four hours off, so that you never really had any sleep of long duration, and you still had to keep the ship running, too. The reason for the two hours was that you had to concentrate so hard without radar because the motto of the ship was “To see them first”. If you got sighted first, that was trouble, so you had to see the enemy first and to do this, that means you had to look through binoculars all of the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you remained surfaced except when you were preparing to attack?

John Henderson Turner:

At night. In the daytime early in the war, we submerged. Yes, we stayed in close to the coast and looked for ships coming along the coast. Submerged, you felt more comfortable.

Donald R. Lennon:

Really, being able to use something other than the periscope, it seems to me, would have been a relief?

John Henderson Turner:

The periscope actually is small, and if you take a look, say every ten minutes or so, carefully around the horizon and up in the sky, you don't miss very much. Nothing can get close to you except an airplane, and he won't see you most of the time. In a very

flat calm he might, but if there are any ripples at all, he won't see you. So your main concern was being surprised by a ship, and the sonar gear would tell you this. So you felt more comfortable submerged. Fresh air was great; when you came up at sunset, that first puff of fresh air felt pretty good.

Donald R. Lennon:

What of your Pentagon duty that you were speaking of that you enjoyed so. Any particular aspects of that that would be of interest?

John Henderson Turner:

I happened to have at that time the desk that had concern with Africa and the Middle East. The Middle East, the Israeli-Arab thing that had been going on for years and years and years and will, I'm sure, continue, but that had some rather fascinating things about the politics of how our domestic politics get mixed up in our foreign policy. We used to have pressures being applied by embassies, our own politicians for their own reasons. Some politician from the Bronx is going to apply pressure for pro-Israeli and some politician with a big oil interest in his district is going to apply pressure for the Arab side. And how these things get accepted...

Donald R. Lennon:

Southern Congressmen from North Carolina, say, would have tobacco interests in the Middle East that they needed to have looked after.

John Henderson Turner:

That's right. Actually, we went through quite an exercise, I'll put it, when a colored Congressman and the NAACP put the heat on the Navy to keep carriers from going into the Union of South Africa, into Capetown because the colored sailors wouldn't be treated the same as the white sailors. This type of thing, which I had never been exposed to at that level of government, anyway. And I thought it was fascinating.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, did you stop sending the ships into Capetown?

John Henderson Turner:

Eventually we had to, but we didn't at that time, later on in another administration.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine the pressure from the top is more powerful than that in Congress, is it not?

John Henderson Turner:

Ah, well yes. What the President says is what happens, period.

You train for years for war as a professional naval officer, and yet when the time comes in combat, I think you run more on instinct than anything else, plus all of the training that you've had. I mentioned to you about the first time that the Sculpin shot another ship; the approach was on the surface about one o'clock or one-thirty in the morning because in those days, we stayed submerged during the daytime and on the surface at night. And you slept all day, and you stayed awake all night. While later on in the war, we learned about red-lighting, we did know that if you wore red goggles, it would keep your eyes from becoming too much adapted to the night, so that when you went on the bridge, you should be able to see. One trouble with these red goggles was that they made your food look terrible. Green beans looked like grey slate.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you wore them the entire time that you were on duty?

John Henderson Turner:

When you were inside of the ship at night, and the Captain would wear them all of the time. If he was not on the bridge, he would be down inside of the ship somewhere with these red goggles on. Well, on this particular night, we had had no action for some thirty-five to forty days, and it's hard to maintain a degree of alertness; so he was down in the ward room having a cup of coffee, and he and the second used to rotate between the bridge, and the officer of the deck would be up there plus three lookouts and the quartermaster. The first inkling that we had that there was anything going on, I happened

to be in the ward room at the time, was that we heard the engine enunciators in the control room ring. That meant a change of speed. Then we could hear over our speaker system between the bridge and the conning tower the officer of the deck yelling for the Captain to come. So he ran out of the ward room, fell down the hatch, down into the battery because the man that had gone down to take--we were charging the battery--had gone down to take the readings on the specific recovery of the battery and had left the hatch open. He got up, and he split his shins wide open, but he got up and ran to the bridge. He couldn't see well enough, and the officer of the deck was saying, “There's a ship right ahead of us and he's crossing our bow.” So he said, “How far is he?” Well, he said, “He's about a thousand yards, and he came out of a rain squall. And so the Captain said, “Well all right, shoot!” Our fire control system was very bow and arrowish. We left the jack-staff on the bow, which was right on the tip of the bow, up, and we trained, and trained, and trained at this before the war, of shooting at night. We put that jack-staff in the middle of the target and moved the gyroscope on the torpedo the amount that we wanted to lead the target based upon a guess of its speed, of the target's speed. I think it was the target's speed, plus three degrees. If the target was making ten knots, you led it by thirteen degrees. And you had to find out, first of all, which direction it was going and then put the jack-staff on the bow of the target and fire three torpedoes. One at the bow and then stay on a steady course and when the middle of the target got to the jack-staff, fired another torpedo. And when the stern of the target got to the jack-staff, fire a third torpedo. One of those theoretically should hit him, because you had a spread in time. The second torpedo that fired was a premature torpedo, and it exploded when it armed, but on of the others hit. It turned out that actually this was a convoy, but we were so

confused that we didn't realize it. We just saw the one ship due to the rain squally everywhere. So we dove because the destroyer turned a search light on us or in our direction. We dove, and they dropped a couple of depth charges, but that was all. Nobody really knew what had happened except we knew we had hit the ship. And it all took about five minutes.

Donald R. Lennon:

They just dropped a couple and went on their way?

John Henderson Turner:

No. They didn't know where we were; we didn't know where we were, either.

Donald R. Lennon:

Their equipment was no better than yours.

John Henderson Turner:

That's right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was there absolutely no danger of allied vessels, surface vessels, being in the area?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, the submarine areas--early in the war there was some danger because it was confused; after all the United States Far East forces were in retreat, particularly the Naval forces. They stayed in Manila Bay or had Manila Bay available to them until about Christmas, or not quite until Christmas, and from then on, they were falling South all of the time. If you notice, we went from Manila to Borneo, to Java, to Australia, and we finally ended up on the southern southwest tip of Australia. That's a long retreat, and there was confusion. But once things go settled down, then the submarine areas were well defined. They changed the course as the war progressed, and the Allied Service forces regained control of more of the the Pacific. But the areas that were assigned to submarines as patrol areas were theirs. There was no other allied ship in it. And toward the end of the war, this restricted area for submarine operation became quite relatively small, the coastline of Japan, even the Sea of Japan, and the Sea of Okhotsk. The

submarine when it left port, left on a moving zone from which it was protected. Nobody was to attack a submarine in this zone. The zone moved at a constant speed and was a few miles wide and quite ling, and long, and it moved until it got to the area that the submarine had been assigned to. As long as he could stay in that zone, he didn't talk to anybody. If he couldn't because of weather or mechanical failure or something like this, then he would have to open up and re-establish a new zone.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I was getting ready to ask. When you said a moving zone. Then what happened if you didn't keep up with your moving zone?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, you would have to check in and say why you couldn't stay in the zone and re-establish a new zone, but during the period of re-establishment, you were in peril of being bombed by your own forces, and this happened occasionally. Early in the war it happened. I don't think any of our submarines later on were bombed; we had one submarine sink one of our own ships because it wasn't in its zone northwest of Guam. It was a real tragedy.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is what I was wondering when I asked my original question. If you were pulling the trigger on a torpedo and could not identify whether the ship was allied or enemy, what did you do?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, I had the problem up in around the Kurile Islands. Many Russian ships were going to Vladivostok from the northwest United States, and they would come in by Paramushitu and then go on up north by Sakhalin and come down through the straight between Sakhalin and Siberia and into the Sea of Japan that way. They were supposed to be lighted at night, and they were supposed to have a flag, a Russian flag painted on their side.

Donald R. Lennon:

But wasn't that an open invitation for the Japanese?

John Henderson Turner:

They were not at war with each other. They were not at war with each other. There was an invitation for them to have their ships follow along, but I don't think they ever did.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did Australia have a Navy to speak of?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, the Royal Australian Navy, very fine.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking that there was always they danger of picking off an Australian ship.

John Henderson Turner:

Well, no because they operated, there was an Allied command, and they all operated under U. s. and Allied and Dutch and Indian and British, and the French. The French didn't have too many bases down there, but they did have an interest and they did have some ships there. So this was pretty well--I hate to use the word, but it was not well-coordinated. Running a big operation, mistakes can happen; they did occasionally.

Donald R. Lennon:

When the vessel was spotted, I imagine you had to be very deliberate in your movements from that point because if you got in too much of a rush, that's when you would be more inclined to miss your target and make mistakes in your diving and everything else.

John Henderson Turner:

This is true. Missing the target was the main concern. If you were on the surface at night and made contact with the target, particularly after radar came into being, you'd pick it up on the radar before you ever saw it. The first thing that you did was to head exactly down the bearing that the radar contact was on and run at high speed as fast as you could and try to find out which way the bearing was tending, whether it was going to the right or to the left. Then you would turn 90 degrees and run at high speed to see

whether or not you could keep it from continuing in that direction. If your speed could overcome the bearing change and in fact make it go the other way, then you knew that you could reach the target at your convenience. So if that proved to be true, then you would close in to the target and track it. If it was a convoy, you would try to track the screenk, too, to see if there were any holes in the screen or how many ships were in the screen. sometimes it would take a couple of hours. You would work up in front of the convoy and then turn and head right. You'd get up ahead of the convoy, this is on a night, and having determined what general course it's making good, try to arrive at a point about two miles off of that course. Then you head in directly, pointing directly at the closest escort to present as small a picture as you could, a small visual target. You turn off the engines, get on the battery, and seal the ship up so that you're all ready to dive. And when you get about three miles from the escort, you opened all of the torpedo doors and you were ready to pull the trigger any time. You kept just coasting in very slowly and you tried to stay a mile or so away from the escort. After you got on his beam, if he wasn't worth shooting, you'd let him go by and scoot in under his stern because his attention is more up ahead than it is a stern. It's human nature. Scoot in under his stern and get inside of the screen to the ships they were protecting. And fire the torpedoes out of the bow into those ships, turn rapidly and fire the torpedoes out of the stern, and hope that you got them all off before the first one started to hit. When the first ones hit, that's when everybody started charging around with search lights going, and depth charges were dropped. You wanted to be ready to dive, but you wanted then to get outside of the screen again and run. If you could do that, then you wouldn't have to take a depth charge.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you ran on the surface as long as you thought it was safe to do so?

John Henderson Turner:

If the guys started shooting at you or the search lights came on to you, you knew it was time to go down. But if we could stay on the surface--it was a point of judgment, really, because if you could avoid the depth charges, if you dove, your chances of getting depth charged were really good. They were better if you stayed on the surface.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, were you ever spotted before you had an opportunity to fulfill this?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

In that case, did you go ahead and try to torpedo, or did you just try to flee?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, by the time I got to be a skipper, my idea was it was better to shoot the escorts and get them all confused, and then come back again and take apart the convoy. Every skipper had his own system. He believed in what worked best. For awhile we'd sit off with the torpedoes. These were speed torpedoes. They had two speeds; one was a slow speed, and one was a high speed. At high speed they had a range of about forty-five hundred yards or two nautical miles, and low speed would go almost six thousand yards or three miles. It was a very deliberate solution by radar of the tactical problem, fire control problem, to sit off at this great distance and fire in through the screen into the ships in the convoy and not try to penetrate the screen. Of course, a small error in the target course or target speed might cause you to miss.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, if you missed, and it didn't explode, of course they would be none the wiser.

John Henderson Turner:

At the end of the torpedo's run, they exploded.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now when it exploded, how would they know what direction it came from if they had not spotted it prior to its exploding?

John Henderson Turner:

The steam torpedo and the electric torpedo, too, at night, in most waters of the world, really, there was a lot of phosphorescent, and the torpedo looks like a head light when it takes off out of the bow of the ship going through, particularly in the tropics, there's lots of phosphorescent. The phosphorescence lasts for awhile; they don't just streak through the water, and the escort would spot that wake and turn and come right down to it away from where the ship had been hit, you see. Your objective was to get away from this firing point as rapidly as possible. And when you were submerged in the daytime, if you sighted a target, of course your speed is considerably limited submerged. In a World War II type submarine, you rarely ran during an attack at speeds higher than six knots because you drain the battery so rapidly. The battery has only so much electricity in it, and when you run out you have to surface to charge it again. So you would take the initial bearing on the target when you first sighted it, which usually in clear weather would be just the tip of the stack or the tip of the mast, you head right for it and see which way it was drawing, and take 90 degree to that bearing and run at high speed, as high as the state of your battery permitted you to. You run for, say half an hour, and come up and look and see if you could see the target, if it was getting closer or if it was coming your way. If you couldn't hold the bearing, that meant you might have to really get down deep and run as hard as you could to try to get as close to the target as you could before you shot. If you were up pretty close to the track of the targets coming along, then you could try to seek a point about seven or eight hundred yards from the target and just forward of its beam when you shot so that you would reduce the number of errors from the torpedo's course. The simplest torpedo shot is called the “straight bow shot,” and it's just like shooting a bow and arrow. You just shoot the torpedo exactly

straight and lead the target by the amount of degrees you figured the speed is. You can take ranges with a periscope optically. You could then, and toward the end of the war, there was a periscope that had a bigger head than the attack periscope, and it had a little radar addition, too. You could take a radar range at maybe three miles or something like that, because optical ranges were not that accurate. Bearings were always very accurate, but the range in essence in the fire control solution had a great amount of influence on what speed you thought the target was making. So if you could get a couple of radar ranges, then you could get the target speed pretty closely. And the target speed determines what angle you lead the target by to hit it. You learned all of this at submarine school.

Donald R. Lennon:

One thing that I was curious about, on the occasion when you were depth charged and lost your periscope and compass. You still could have made radio contact if necessary?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, our radio was all right although we had to rig a jury antenna because the antennas had been knocked down. When we surfaced that night, the only thing we had to tell us if there was anything around was the sonar gear; we couldn't see anything. It was a little hairy coming up.

Donald R. Lennon:

And how long did you remain down without a periscope?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, from dawn, through the day, through the night, and through the next day.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you think that the enemy was after you? Had the depth charging ceased?

John Henderson Turner:

It didn't cease.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, it just continued?

John Henderson Turner:

They continued for about twenty-four hours.

Donald R. Lennon:

They knew that they had you down?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had they been able to hear your prop?

John Henderson Turner:

They were pinging. They were following us along, depth charging.

Donald R. Lennon:

And so you really took a chance coming up even when you did?

John Henderson Turner:

Well no, we hadn't heard them for a long time. But it was still daylight, and we didn't know where we were, and we were afraid of airplanes. We weren't too far from an air field.

Donald R. Lennon:

And there wasn't too much you could do in getting a bearing during the daytime.

John Henderson Turner:

That's right. That's right.

Pearl Harbor came along, and we were staying at the Halakallani Hotel, which was down on Waikiki Beach, and there's a lovely little place, with just little cottages. In fact, we were there just two years ago, to go to where we had our honeymoon, and it's the last of the little hotels that were there when we were. Of course, Pearl Harbor Day was a very confusing Sunday there, and the next morning she went from her cottage over to breakfast, and there were all sorts of rumors going about the Japanese were landing on Oahu and they were landing here and were landing there. They were going to attack again, and this type of thing. After breakfast, she went back to her room, and the Japanese houseboy was in there cleaning the room. At about this time, a couple of airplanes came by right down the beach, and he ran over and looked out the window, and he said, “It's all right, Missie, they are ours.” And she didn't know what he meant.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did he consider his?

John Henderson Turner:

He considered himself American, as all of them that I ever met did. And they were very strong Americans.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that the families of Naval officers were under considerable strain throughout the war, were they not?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, this is true. They were. For instance, my wife did not have any communications from me from early December of '41 until May of '42. And I had none from her until late May, I guess it was, or June. But we would, when we got into port, we would see somebody who had seen somebody and pick up some information like this. As boats went back to the States for repairs, then those families would find out, “Oh, so-and-so was all right in January because I saw him in Sarabia,” or something like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, even when you were in port, you were unable to write or call?

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, that was all right, the mail service wasn't very good. I don't know whether you remember it or not, but they had things called V Mail, and that came through pretty fast. But letters took quite a while. Donna wrote to me every day. So when I would come in from two months at sea, I would have a stack of mail to read. But I would write usually about once a week or so, maybe a page and send the whole bundle in when I got into port and write a couple of times while I was in port.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, that type of correspondence would be censored, too, would it not, because it was coming from the war zone?

John Henderson Turner:

The only thing that you could say was that “I've seen so-and-so”, and this would say they're all right, and they would be friends so she would write to the wife. Occasionally, you could say, “Well, I've seen so-and-so who just came from the States,” and she might know partially what area they were going to, so this would help. But you

tried to obey the censorship, and one of the reasons I think that we didn't lose more submarines than we did was because they were pretty good about not talking too much. Oh, the Japanese did not set their depth charges deep enough, and we found this out early and could stay underneath them.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like they would have realized that rather quickly?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, they didn't; this was a well kept secret. Everybody in the submarine, of course, kept it, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

As a means of survival.

John Henderson Turner:

That's right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those officers you served with, both your superior officers in the command and your colleagues, are there any of them that made an impression on you as particularly competent or unusually colorful?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, yes, the skipper of the first submarine I was on during the war, the Sculpin, had come to the ship within a few months before we went to the Philippines. His predecessor had gotten sick, and the skipper that originally commissioned the ship had had two years, and this was a normal tour for him. But this first combat skipper was a man by the name of Lucius Chappell, and he was from Georgia, and he talked with a very soft voice, never got mad, never got excited. And I admired him a great deal. He taught me a great deal. And I still correspond with him. He was a professor at Monterey, in California, and he retired about three years ago. He's lost the sight of one eye now, in fact he had to have the eye removed. He, I thought, was probably one of the finer officers I've ever met. A real steady citizen in a tight spot. Oh, you meet lots of petty officers. For instance, when I went to the Sculpin as a new ensign, there was a second class

gunners' mate on there by the name of Cussetteo, and actually the last two submarines that I commanded, he was the chief of the boat. Chief of the boat on a submarine is the top petty officer, the chief petty officer, and he is the strong right arm of the executive officer. And he makes the boat run. Cusseteo and I were together off and on, on four submarines. He was excellent. I admired him a great deal. Many of the men that were on the Sculpin as enlisted men were later commissioned, and they became officers. When I went to the Seal, there were two or three men there that were commissioned while I was on the Seal. In fact, I still correspond with some of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that submarine services was small enough that it was kind of like a private club, was it not?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, when I graduated from the Naval Academy, the Navy had sixty-one hundred line officers, approximately. After World War II had been going for a year or so, this number had grown twenty-or thirty-fold. The Navy, when I graduated from the Academy, you knew about at least half of the officers in the Navy, by their reputation, by their name, and if they were in submarines, everybody in submarines knew everybody on the submarines. There weren't that many of us. Then a tremendous influx of very fine reserve officers and enlisted men that had come up had been commissioned. This was a tremendous expansion, and during the war, you were at sea so much you didn't get to see very many other people. So when the war was over, you knew actually the people you had known before the war and started, plus those you had been in port with in various places in the world. Then in this tremendous demobilization many of these people that you had known went back to civilian life. And many who were commissioned during the war either went on in civilian life in their rank or went back to the rank they had had,

some lesser rank. It was quite a turmoil. I think now probably those people that are active in submarines know most of the other people in the submarine. It's not that big anymore. Now I think that those who are nuclear qualified tend to run together, and those who are not tend to run together, and those who are in the Polaris program tend to run together against those that are more in the attack submarines. And this business ins the same with aviators. Those in the history department in college tend to run together.

Donald R. Lennon:

The submarines, as they were at the beginning of the war with all their inadequacies, had they changed basically much, say, since the World War I period?

John Henderson Turner:

Well, some of the submarines that fought in the early part of World War II were World War I submarines. In fact, Admiral Davis was skipper of a World War I submarine in the early part of World War II and fought with that submarine at Rabaul. You should talk to him.

My father, in World War I, was commissioned and after the war was over had to take examinations to see if they retained their commission or went back to their previous rank, and he passed the examinations. He worked like a dog for a year in labor. He was very strong, technically, as a machinery and an electrical expert. I believe he became the repair officer of the . Then he came back from there to Washington and was in the bureau of something or other, I don't know what it was, but as the submarine desk man had all of the planning and the technical overlook planning of overhauls, new submarines, and new equipment.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were virtually born in the submarines.

John Henderson Turner:

Yes, I was. When I went to the Naval Academy, I got into it. I have had a good life.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was he still active when World War II broke out, or had he retired?

John Henderson Turner:

No, he died when I was in the end of my junior year in the Naval Academy. He had a heart attack. He had been in the Navy for twenty-seven years. He had joined the Navy to go around the world with the great fleet in Teddy Roosevelt's day.

[End of Interview]