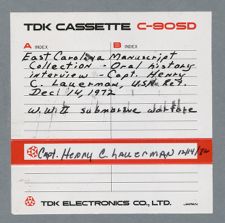

EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

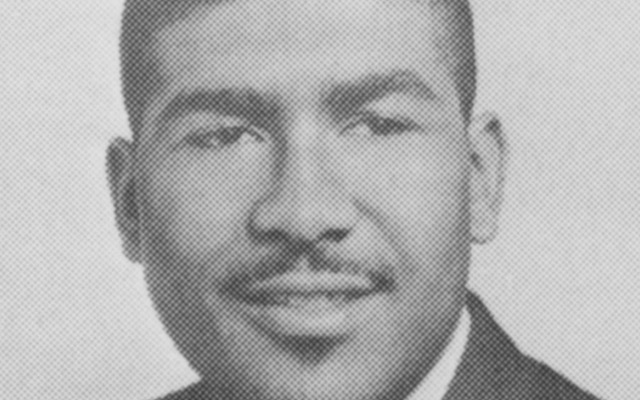

Henry C. Lauerman

December 14, 1972

Interview #1

Henry C. Lauerman:

I graduated from the Naval Academy in June of 1938. My first assignment as an ensign was on board the battleship CALIFORNIA. The battleship CALIFORNIA, as you may know, was seriously damaged at Pearl Harbor and did not really get back actively into the war again. However, by that time I had been detached from the CALIFORNIA. I was on the CALIFORNIA until 1939, and then I was assigned tot he gunboat, ERIE, which was a very interesting tour of duty down in South America as a young officer, in what was known as the “Banana Squadron.” Now, you know about the Banana Boat Squadron. Our principal function there was to show the flag and to maintain, shall we say, “American presence” in South America. I was on board the ERIE for about a year and then I had a choice of becoming a naval aviator or going to submarine school.

I decided to opt for submarine school and was assigned to the class that convened in January of 1941. I completed the three-month basic submarine officer training school at the end of March of 1941 and was assigned to the U.S.S. TAMBOR, which was then a new submarine, a so-called fleet submarine, the 198. All the latest technology of course was included on that submarine, and it was at that time commanded by a man by the name of John W. Murphy. He was a very fine officer and considered to be one of the very best in submarine force at that time. The submarine had been undergoing some

special tests concerning the hull strength; these tests had just been completed and the submarine was getting ready to proceed to Pearl Harbor to join the Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet. In due time we went out to the Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet, and I was on board the TAMBOR until after Pearl Harbor and the battle of Wake Island. We then returned to Pearl Harbor, and I was detached from the TAMBOR and proceeded to the U.S.S. HALIBUT, which was fitting out at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

I reported to the commanding officer of the HALIBUT early in 1941 and remained on board for about a year, completing the fitting-out and operating with her in the Pacific. I was then detached from the HALIBUT in Pearl Harbor about 1943. I went back to New London in connection with the fitting-out of the U.S.S. SEA LION. I was the executive officer of the SEA LION from April of 1943 until about October of 1944. When I was detached from the SEA LION, I was placed in command of the U.S.S. CABRILLA in San Francisco late in 1944. She was in the navy yard at Mare Island being overhauled. I took her out to the Pacific in 1945 and made two patrols on her. I was relieved from command just as the war ended and proceeded back to Washington, D.C. I was en route flying across the Pacific when the Japanese cease-fire was signed.

From 1945 to 1948 I was on duty in the office of the Judge Advocate General and attended Georgetown Law School. From 1948 to 1950 I took command of the U.S.S. ARGONAUT, a submarine which operated out of New London, Connecticut. I was in command of the U.S.S. ARGONAUT for two years, whereupon I returned to Washington for a tour of three years in the office of the Secretary of the Navy, largely in connection with legal and legislative duties. From 1953 to 1955 I was in San Diego, California, as the executive officer of a submarine tender and the commanding officer of a submarine

division operating out of San Diego. In 1955, we returned to Washington and I was given another tour of duty in the Secretary of the Navy's office. In 1958 I went to Norfolk and was on duty I the office of the commander in chief of Headquarters Atlantic and the Supreme Allied Command, Atlantic. Then I was given command of the U.S.S. MOUNT McKINLEY, an amphibious command ship that I commanded from June of 1960 until February of 1962, when I retired. I went to Duke University for a year of postgraduate work in law and then resumed my present duties as a professor here at Wake Forest Law School. So that is my lie. It was in itself an interesting, exciting, and varied career and I've enjoyed every minute of it.

I took some time here to do the best I could to reconstruct what had occurred, some of the incidents that had occurred during my war years and war experience, because I understand that is principally what your interest is. First, I'm not sure what you know about submarine operations, particularly war-type submarine operations. I'm not certain that very many people do. I was wondering if you wanted me to talk generally about this or whether you'd like me to refer to specific incidents. What would be your pleasure? Well, of course, you know there has been a great deal written concerning submarine operations, which is generally available, and I don't think there is much purpose in rehashing a lot of that material.

Throughout the war years, one of the chief attractions, it seems to me, was the extraordinary camaraderie that we had in submarines. Maybe we still have this kind of comaraderie in combat operations, but I'm not sure that we do. I rather feel that we have. Although the submarine itself was a highly mechanized and very complicated piece of apparatus, there was still a very great opportunity for individual management, individual

handling of the various valves and what not; so there was a great deal of activity by men on watch. For example, we had a bow planesman, a stern planesman, and a diving officer. These men were constantly trying to maintain the submarine on an even keel at a certain depth. There was a great deal of pride taken by the bow planesman and stern planesman and the diving officer, and the competition was existent among the various sections of the watch to see who could do the best job.

Now, in our new submarines much of this is handled by computers and automatic devices; and one watch is like every other watch--that is, one section of the watch--and their machine either works or it doesn't work. If it gets out of kilter, well who's responsible? There is no great amount of responsibility. So, I think that modern submarines have lost some of the individuality and charm, if you can say that a submarine has charm, which made us all a very cohesive unit.

I look back on my submarine days and think back on my experiences and on how closely knitted together we were. There was a feeling of mutual respect and a feeling that the officers could not get along without the men. I'm sure the men could have gotten along without the officers; but at any rate, there was a great feeling of oneness and unity. This was a tremendous sustaining course when you were out on patrol for long periods of time, isolated away from all, completely dependent on one another; it sustained like nothing else could. I think this is terribly important. Being a submarine officer was not like being a combat pilot. There it is sort of a one-for-one proposition. Nor was it quite like the infantry, I don't think; and it wasn't quite like, shall we say, a ship in convoy. It was something, I think, that was extraordinarily unique. Of course, you also have the fact that you are under the water a great deal of the time. I think the World War II aviators

had a comparable selection and I'm sure that they still do, but there was a very careful psychological check made of all the candidates for the submarine service.

So, with this in mind, we approach the submarine service with a feeling of tremendous loyalty to the ship. This is deep, very deep. When you were being depth-charged and those depth charges were going off all around you, you didn't dare crack, you didn't dare. You couldn't show, the officers felt, you just had to be cool; and as pressure was there, the men were holding you up. They were shaking in their boots, and you just had to sort of, well, play it cool. Of course, you weren't really very cool; you were just as scared as they were and they knew it. But we all played the game because it was very important that we all hang together. With this in mind, we might begin some of our reminiscences.

The first submarine in which I was stationed was the U.S.S. TAMBOR. I was out of submarine school in the spring of '41. The war began in December '41; so I had about six months to be shaken down. John Murphy did the best he could to shake me down. He was a tremendously fine leader. I guess that every young officer, when he first joins the service, looks upon his commanding officers, whoever they are, with a very special kind of regard. By the time the war had begun, I can recall having loaded torpedoes. The war had not yet begun; it was about November of 1941, and we knew that we were about to go out on what was called a practice patrol. But a few days before we were ready to sail on the practice patrol, Captain Murphy called all the crew together and told them in confidence that the situation was very grave so far as our relations with the Japanese were concerned. This was denominated a practice patrol, but he said we would have warheads

on our torpedoes and the torpedoes would be in all respects ready to fire. Our instructions were that this should be a combat-ready patrol.

We departed from Pearl Harbor about mid-November and proceeded to take station off Wake Island. We were on station when the Japanese attacked Wake Island and put a force ashore. But one of the things that people have difficulty with, or most non-military persons, particularly most non-submariners, is understanding the fact that a submarine in many ways at least a fleet-type submarine, which had very low battery capacity, could only stay submerged for a limited number of hours. It could only proceed at relatively slow speeds submerged without using up all of the energy that it had in its battery; so we were rather limited in the amount that we could move about. These were the days in which we had battery-powered submarines for submerged operations. We ran on our engines at night. But then at night, although we knew where we were with reference to Wake Island and where we were with reference to the earth and know what our position was, we didn't have radar and other sophisticated means of detecting targets. So if we were not in visual contact with the formation of ships at night, it was almost impossible for us to find it.

Although we were on patrol off Wake, we frankly didn't have much success in contacting the enemy. We would see them way off over the horizon at dawn, shooting, perhaps, and we'd steam over in that direction; but by the time dawn would come, the ships would be gone and we'd be there. Then we would submerge and that would be it. So, at any rate, there was not much that happened off Wake Island.

I was called, I remember, on the morning we were east of Pearl Harbor. I had had the mid-watch the night before and so I was sleeping in. It was about 11:00 on Sunday

morning that I was routed out by Ed Spruance, the son of Admiral Spruance, who was the gunnery officer. He said, “Hank, the Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor. We're at war with the Japanese.” And, of course, I didn't believe him. So that was the way the war began for me--on patrol off Wake Island on December 7, 1941.

Well, we returned to Pearl Harbor in due time without firing any torpedoes, and I was then detached from the TAMBOR and proceeded back to the HALIBUT, which was then being built in Portsmouth. Our first patrol on the HALIBUT began in August of 1942, after our fitting-out period. After getting the ship ready, we steamed from Portsmouth through the Panama Canal out to Pearl Harbor. Then we began in 1942 an assignment that probably not very many submarine commanding officers relished at the time, because we went north; we went straight north from Pearl Harbor up to Alaska and to the Aleutian Islands.

No, individually. Our submarine went north to the Aleutian Islands to Dutch Harbor. There was a contingent of submarines at Dutch Harbor, which had been there for some time, because units of the Japanese fleet were operating in the vicinity of the westernmost islands of Attu and another island. They had, as a matter of fact, occupied small detachments on these islands. There was very little shipping up there, but our main task was to interdict any sizable Japanese force that might be moving east and be tempted to take additional islands of the Aleutian chain, or to possibly invade Alaska itself, or perhaps raid the West Coast of the United States. So, our primary task, along with some of the aircraft that was in the vicinity, was to interdict this kind of advance.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't Aleutian duty rather hazardous for submarines?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Very much so, very hazardous. We had a submarine, the S-36, I believe it was, that was anchored at one time off the coast of one of the islands. A little sea came up, a little wind, and the fog settled down, and she dragged anchor and wasn't aware of it. It was foggy and she had no way of checking her position. When it came time to get underway, she weighed anchor, started her engines, and went but a few miles when she ran aground and was lots. And, of course, the storms were simply tremendous up there. That's the cradle of the storms. You get these very violent storms that make it very difficult to operate a submarine. There is a time when just as you come up to the surface the submarine basically has very little stability; it's neither submerged, nor is it yet fully afloat. At that time, there always was considerable apprehension in the minds of the crew that if a sea were to strike the submarine just at that instant, in a particular way, the submarine might capsize. However, I don't know of any instance of that occurring.

One of the principal incidences that occurred while we were up there...well, there were two. One was rather amusing. There was a contingent of Russian submarines up there. Of course, Russia was our ally, and these Russian submarines had been in the United States for some kind of training. We had agreed to train some of their submarines, and we met them up there at Dutch Harbor. Well, although there was officially a, shall we say, “friendship” between the Russians and the Americans, some of the submarine crews didn't look with a great deal of sympathy upon the Russian submarine crews. As a matter of fact, our commanding officer and one of their submarine commanding officers got into a fight in the bat at the little officer's club up there in the quonset hut at Dutch Harbor. We almost had an international incident out of that because there were some rather insulting exchanges.

At any rate, we got that squared away and went out then to patrol along the northern edge of the Aleutian Islands. As usual there was fog and the sea was like glass. No breeze was stirring, oh, about just to dawn. We had heard that there was some Japanese destroyer activity in the vicinity, but we hadn't see anything or heard anything. I came up to take over the watch. It gets light very early up there at that time of the year; this was in the summertime. There was heavy fog and I couldn't see a thing, not even the bow of the boat. The officer of the deck said, “Well, Hank, it is very quiet.” Just at that time there was a tremendous boom. We looked around, and there was a splash in the water. Evidently the Japanese destroyer had detected us in the fog. I hadn't yet relieved Eddie, and he said, “Take it down.” So of course, I jumped down the hatch, and the crew jumped down the hatch with me. We waited and waited for Eddie, but Eddie didn't come. Finally, of course, the water began to come in through the conning tower hatch and the Japanese destroyer was firing at us...so what's to be done? We continued on down and were depth-charged for about twenty or thirty minutes. When we came back up, I recall that the sun had broken through the fog. It was about two hours later, and there were Eddie's rain clothes hanging from a little radio most in the back, and that's the last we ever saw of Eddie. I often thought he was a fine guy. He was from a town out in Ohio, a reserve officer, and he had recently graduated from an elementary radar school. So that was my first, shall we say, close brush with a casualty in World War II.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was he hit?

Henry C. Lauerman:

He wasn't hit. We think rather he must have gone back. There might have been some men that were up on deck at the time; there had been some men back on deck. It was cold, and we think that he might have slipped or fallen or something. He went back

to check to see if anybody was left on deck when we were submerging. Normally, the routine on submerging was for the lookouts to come down--jump down the hatch--and the officer of the deck followed. The quartermaster then, who was already down, stood waiting for the officer of the deck to come down, and then he would putt it to as the officer of the deck came down. Then the officer of the deck usually would help the quartermaster hold the hatch to make sure it didn't come open as the quartermaster turned the wheel. But Eddie never came down. And we don't know what happened to him. Once the submarine starts down you can hold it to a certain extent, but I think by that time, once the water had gotten up to the hatch, Eddie would have been washed overboard anyway. So there really wasn't much that could be done. Of course, we trained, trained, trained, trained, to make certain that that didn't happen; but for some reason he never came down the hatch. Any delay would have jeopardized the entire crew, so there was nothing much that could have been done about it. Looking back at it, I can still we that this is one of the clearest memories that I have--seeing those rain clothes up there swinging in the breeze and that find young man Eddie Oglethorpe gone. But, anyway, other than that it was a rather quiet patrol.

The Japanese were not too concerned about the Aleutians. At one time they had had substantial plans for the Aleutian Islands, but they decided early in the war, I think , that they better work on Midway and confine their activities to more productive targets. At any rate, we returned to Pearl Harbor.

We were out-fitted in November and took off for Japan. We proceeded, stopped at Midway--topped off fuel at Midway--and went out to Japan along the coast north of Tokyo, off the main island of Honshu. We stayed on patrol there for about two months in

November and December of 1942. We contacted about five or six ships and sank two ships on that patrol: one freighter about 5,000 tons and another about 2,000 tons--about 7,000 tons of shipping on that particular patrol. We were depth-charged and that was my second real exposure to depth-charging. However, it was a little bit closer up there, because they were a little bit better. The first team, in fact, was on station off the mainland of Japan, and we really had some rather rough and tough depth charges.

Now of course at this time, the HALIBUT, like every other submarine, was faced with the problem concerning torpedoes. Our torpedoes were not running as they should and although we saw additional ships, we'd fire and just nothing would happen.

There is one other thing that I thought was most interesting, and, as an historian, you should appreciate this. Each commanding officer would make up his patrol reports as the patrol went along. Then, he would polish them up on the way back to the home base at Midway or Pearl Harbor or wherever it was. After each attack, we would have to assess the damage we had inflicted. Well, many of these attacks occurred in the heat of the battle and at night, which made it very difficult to identify the target. And although some of them occurred during the day, if the target was escorted, it was very difficult to identify. Your main concern was first to get a torpedo off and, secondly, to get the hell out of there and make certain that you didn't get it. After all, once your presence had been detected because of the torpedo wake or because of the exploding torpedoes or whatever, it was usually not too health. Of course, all these targets were convoyed by antisubmarine craft of one kind or another.

Well, now then, you have been depth-charged for a couple of hours and you've sweated that out; you've gone as deep as you could and now you're back, shall we say,

pulling yourselves together again; and maybe five or six hours have elapsed. Now comes the problem: What was it that we shot? We knew it was a ship, but a ship through a periscope or a pair of binoculars at night was not the kind of thing that could be readily identified. Yes, it was floating on top of the water, but at night it's a black blob out there. We would look through the binoculars by day and also through the periscope, which gave us a little bit better vision of it. However, if you're also the commanding officer or whoever is on the periscope, which is the commanding officer, and also trying to keep track of the escorts and just taking quick looks at the target from time to time for just a few seconds, the problem becomes one of trying to ascertain what it was that you hit. But how was this don?

We would look at a book of Japanese shipping. They had these ships arranged by mast structure. Certain ships had so many masts. Then some ships had their funnels aft, and some had their funnels amidships. And if it were a tanker, it would have certain characteristics. So the commanding officer would then leaf through the book in attempt to ascertain what particular ship it was that he had destroyed. And if there wee a choice between several ships, one of 10,000 tons, one of 20,000 tons, or one of 2,000 tons, which one do you think he would choose? The largest. And so, this is one of the things that I learned very early. Now, there were some times that I felt really that the commanding officer had perhaps exaggerated a bit. Looking back now, I felt, as a young man, that that wasn't really quite right; he should have been conservative because we'd be far better off, strategically speaking, if we underestimated our success than if we overestimated it. But now I realize I was 100 percent wrong. For purposed of morale and keeping things going, he had no choice. If he, in good faith, can say, “I sank a ship of

twenty thousand tons,” it's better that he say that from the point of view of the command than that he sunk a ship of three thousand tons. These men have gone out there, they have risked their lives, they've risked their all, and the least the commanding officer could do is to give his crew and himself in the process the benefit of the doubt. Now, I don't know whether that was good strategy or not. There was a certain degree of propaganda value back home to say we had so many million tons of shipping. But this made it difficult, of course. I wasn't in the high command, but I suppose they took account of this when they were assessing our losses.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it ever difficult to actually confirm that you had sunk a ship that you knew you hit? Or was there the possibility that it had just been damaged?

Henry C. Lauerman:

This was always a possibility. But by and large, when we hit a ship, we would hear the explosion. Quite frequently we would have a chance to remain in the vicinity sufficiently long so that we would see the ship in such a condition that we knew it was going down. There was another technique that was used, but I never knew how reliable it was and that was one of the problems. Usually, we had to go deep immediately after firing. Then the sonar man would say, “The screw have stopped.” He would almost invariably say this, though, because he too was playing the game. And then the next thing we'd know was when we would hear the torpedoes exploding, as the case might be. Then he'd say, “I hear sounds of the ship breaking up.” We'd hear these crackles, but never having really had a series of tapes run on ships' breaking up, I was never quite sure as to whether or not that really was the sound of a ship's going down or a ship's breaking up. But then if that were so, and we knew we had had a hit or two good hits, usually we would assess the ship as sunk and let somebody else tell us that we were wrong.

Donald R. Lennon:

On several occasions the Japanese reported sinking American vessels that continued to sail.

Henry C. Lauerman:

Exactly, so I am quite sure that there were many instances wherein ships were not sunk that we reported as sunk.

On the HALIBUT, we went back after we made this first patrol off Japan. Then we made another patrol west of Kwajalein and sank three or four more ships on that patrol. Then I was detached from the HALIBUT. The commanding officer of the HALIBUT received the Navy Cross for his work, and I certainly think he deserved it in every way; but the tonnage that he sank was not as large as he claimed it to be.

But then we had a problem: if we sank a small ship or a submarine, which was covered by a good escort, we had exposed ourselves to just as much danger and had exercised just as much skill as if it were a large ship. It takes no more skill to sink the QUEEN ELIZABETH than it does a two thousand-ton freighter if they are both, shall we say, equally protected or operating under the same conditions. Probably less, because it's bigger. So you see, I've often felt that the way in which medals were awarded in World War II was not really quite right. I think that they had some kind of arbitrary scale of tonnage. There was a ship factor: I think it was five ships or twenty thousand tons or some scale as that. If you sank five ships or one ship of twenty thousand tons, then you were entitled to a Navy Cross. I've often thought that really the scale was rather, well, it wasn't quite right, although I'm sure that the high command was very generous. They weren't stingy I the way in which they awarded medals and justifiably so; yet I've often thought that some men did a great deal and really didn't quite get the credit they should have, for one reason or another. They just had to work awfully hard for what they got. I

felt that there were many who were highly decorated who worked hard for what they got, too, but certainly they weren't anymore deserving than some who didn't.

Now, all the commanding officers that I worked for as a younger officer--as an executive officer--were all very successful. Of course, I shared their success and was decorated a number of times; so, I have no sour grapes about this thing. But on looking back, I just wonder whether or not they had the best system of making awards. However, I will say this: in all the time that I was in the submarine fleet, I heard very little complaint about, shall we say, inequity. So, I guess perhaps the system wasn't too unjust or we would have heard more complaints about it. And, of course, one of the principal functions of the high command in any war or any combat is to make certain that people are recognized, and perhaps they err a little bit on the side of overdoing it in order to cover everyone.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they have to make a direct hit?

Henry C. Lauerman:

No. Depth charges can go off in proximity to a submarine. One of the things I mentioned was that the TAMBOR was conducting some tests. Well, one of the tests they were conducting when I first went aboard the TAMBOR was the resistance of the hull to depth charges. The Navy was much concerned about this. During World War II the depth at which submarines could operate was a very highly-kept secret, because by and large the Japanese depth charges were set too shallow in World War II. We lost fifty-two submarines in World War II- a number for the air as a result of enemy air actin and some by just happenstance of various kinds of casualties. I would say probably about thirty were lost because of enemy antisubmarine vessels, although I haven't made a good check of this. But I think we would have lost probably a hundred as the Germans did had the

Japanese known that their depth charges were going off over the submarine. Now, if they go off over the submarine, the force of the explosion is vented upward and very little downward; so that if you're under, you're quite safe. But if you're over the depth charge or if the depth charge detonates rather close aboard one side or the other, you're in trouble.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there ever any danger of your going too deep under the ocean pressure?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Yes, this occurred on my nest-to-the-last patrol, when I was commander of the CABRILLA. We went up to the Kurile Islands during the ice season. This was in February or March of 1945, and Japanese shipping had pretty well disappeared from the seas by this time. Good hunting areas for submarines were hard to come by. There hadn't been any submarine operations up in the Kurile Islands area; so I thought there was something up there worth shooting, maybe a whale ship or something of that kind.

So we went up and we did see a few small ships, but the ice was still pretty heavy up there. We had a little trouble with the ice and one of our propellers was dented rather early in the patrol. When a propeller is dented or bent, it makes a thump every time it turns around, and of course, this is easily detectable by antisubmarine vessels. It was foggy up there in the ice and we denoted two ships on radar. In the early part of the war, or at least during 1943 and 1944, the Japanese ships were not equipped with radar. Our submarines were, so at night or in conditions of reduced visibility, we had a great advantage. We could bore in on the surface of these Japanese vessels and get in rather close without their detecting us. But we, of course, could detect the Japanese vessels through our radar. But as the war progressed, they began to get more and more radar. Well, I didn't know for sure whether or not these ships had radar. I didn't even know

what they were. I didn't know whether they were warships, merchant ships, or fishing boats. All I knew was that we had a contact on sonar--you could hear their screws--and we had it on radar about eight thousand yards away.

We began to close, and they were slowly closing on us. We were sort of on a converging course. We couldn't see a thing, nothing but fog and blocks of ice. We couldn't submerge very well because if you submerge in that ice and stick up your periscope and it hits a block of ice, then you've got your periscope bent. So it was sort of a miserable place for submarines to be operating. And that water is cold, ice cold.

What happened next was much like the incident that occurred up at Pearl Harbor three years before. All of a sudden, gunfire. Both of those ships opened up on us. Evidently, they were some kind of Japanese warships. I never did see them, because we submerged. Well, they evidently knew where we were. Now, whether they had radar r some other device, I don't know; but they must have had radar, because the shells feel very close aboard. So, we submerged, and the two antisubmarine vessels came over and really worked us over good.

One of the reasons that they were so successful in maintaining contact was because the water was what we call isothermal. It was very cold and there was no difference in the temperature from the surface on down to a depth of six hundred feet. And how did I know that there was no difference in temperature? Because our submarine was down there.We got down to about four hundred feet and we were a little bit heavy. When a submarine submerges, if it has absolutely neutral buoyancy on the way down, you can control it with very little speed. You don't need much planning action to keep it in even

keel and make it to go up or down. but if it's a little bit heavy--and it tends to get out of trim when you've been on the surface for some time and have used considerable fuel--it takes a little bit of speed to keep the submarine at whatever depth you wish to maintain it. However, when you provide that speed, you've got to turn the propeller. One propeller had a dent in it which meant that every time we turned that propeller it went bump, bump, bump. We had these Japanese antisubmarine vessels up there with their sonar equipment, sonic detection devices; therefore, we didn't dare make any more speed than just the bare minimum so that we wouldn't be setting up all this racket in the water. Of course, when you get down at those deep depths, four hundred feet, you do have pumps that you can use; however, they are not very efficient at those depths, because of the pressure against which they have to work. They also make a lot of noise. All of this was in isothermal water at six hundred feet. The water temperature was 0℉ or below, because salt water, of course, can be below freezing before fresh water, because of its mineral content.

So here we were, all eighty of us, with these depth charges dropping around us in this isothermal water, and we kept getting deeper and deeper and deeper. I said to Jim Elliot, my executive officer at the time, “Jim, we can't go much deeper. Water is drifting through the various fittings of the submarine and through the hatches, and you can watch the depth gauge going down and down and down. This looks like it.” We either had to start that engine or turn the motors over and pick up speed. We were already low on the battery, so we couldn't do too much, really.

Should we try to increase speed and run away? By this time, you see, it looked as though perhaps they weren't quite sure where we were anymore; and if we increased our speed, they could gain contact, and that would have been bad. Or should we let her sink

awhile longer and possibly get into serious trouble? If we blew a gasket in our propeller tube or something of that kind and began to ship in large amounts of water, we would have been gone. We had no margin for error at the crushing depth of the hull. As a matter of fact, we were two hundred felt below it and our margin of safety was zero. Now, what do you do, what do you do?

Well, I said, “Really, I think the best thing for us to do is to start up and come up to where we can get a look-see and see what's going on and hoe that they don't hear us on the way up.” “Well,” he said, “I don't know.” He was sweating. I was sweating and it was cold. But he said, “Well, let's wait awhile longer; let's just see.” Within ten feet, we hit what was known as a thermocloud. In other words, we were then at 625 feet. At 635 feet the water temperature got a little colder. When you get under the thermocloud, it tends to deflect the sound waves so that they no longer are audible for any appreciable distance. And so, once we got under that thermocloud, then we could increase our speed to the point where we could hold our depth and at the same time, gradually open and leave the enemy behind as it were. After we had steamed along for a couple of hours at a moderate speed and we were quite certain that we had left them behind, then we increased our speed and came up to where we could control the submarine without any difficulty. Eventually, we surfaced and all was well.

That was a rather excruciating experience. I had many of those. Of course, I suppose that some officers were depth-charged more than I was, but it just seemed that every time any submarine I was on would make an attack or make an attempt to attack, we'd catch hell, just catch hell. Whether I was in command or the executive officer or the gunnery officer, they always just seemed to just catch hell. I'd come back from patrol and

share experiences with officers on other ships and it seemed that they'd gone in, made an attack, and gotten away without one single ashcan being dropped on them in retaliation. But no matter what happened, it just seemed that every time one of the submarines I was on made an attack, all hell would break loose. Now, why that was, I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any danger of striking an iceberg or something of that nature?

Henry C. Lauerman:

It was mostly what was known as pan ice. When you're up there in the Kurile Islands at that time of the year, that ice is about two or three feet thick. For a ship that is properly equipped, an ice-breaker type or merchant ship, it doesn't offer any great hazard. But, really, it was not the kind of water in which a submarine can operate, because a submarine in the first place has a very thin hull so far as its streamline is concerned. You've got bow planes up there in the bow and if the ice hits them too hard, the bow planes are out of whack. You've got stern planes astern, of course, and if the ice \hits those too hard, they're out of whack and the submarine is a cripple. Also, the screws are not protected. As the submarine goes through the water, the ice glows down along the hull and gets back into the screws, and if they're bent, why, the submarine again is a cripple. We took great pains whenever we returned from patrol to have a sound test before we went out again. The submarine would submerge and operate various equipment, including its screws, to make certain that it was making as little noise as possible in the course of its operations, because this was one of the ways in which submarines were detected and destroyed by antisubmarine forces. Run silent, run deep.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were along rather than being in fleet and your submarine was crippled, what could you do as far as getting back?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Well, if it were crippled to the point where you couldn't operate, you scuttled it. In other words, you would stay afloat. This happened to several submarines. Of course, it didn't happen to any that I was on, fortunately. You stayed afloat until such time as something saw you, either a friendly ship or a friendly aircraft, or an enemy aircraft or an enemy ship. Then would somebody got nearby, everybody would leave the submarine and jump in the water. Of course, if you're up in a place like the Kurile Islands, your time of survival is about thirty seconds in the water. You just don't survive whether you're in a life jacket or not, because that cold water up there just kills you. So there was no hope there. But in tropical waters, there was a considerable chance of survival.

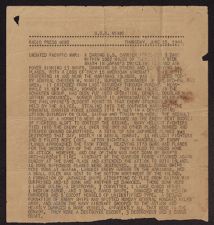

Speaking of survival, I know you've read in that book, or maybe you haven't, the incident that happened when I was on the SEA LION. This was in October, I guess, of 1944. We were patrolling in what was known as “convoy college,” an area between the coasts of China, Formosa, and the Philippines, in that area of the South China Sea. We had detected a convoy heading toward Japan at night and made an attack on the surface, I believe, and had torpedoed a ship. Fortunately, it was one of those odd things, but several torpedoes that we had fired miss the target at which we'd fired and hit another ship. And, of course, this was fine we thought. We watched and then we pulled out. It was night and we pulled out. Of course, our radar was continuing to sweep and we saw these blips disappear. Enemy escort vessels were maneuvering around, so we withdrew and continued on our patrol, having sunk several ships. I think there were four ships in the convoy, and I think, we had sunk three of them.

We continued on our patrol, and then we received a message from another submarine who happened to be crossing the very area in which we had made our attack.

It reported that there were a large number of survivors in the water. I guess this was the following day. I think that it was the PAMPANITO that reported this. At this time I was on board the SEA LION, which was commanded by Capt. Eli T. Reich. I was the executive officer at the time.

We went back to this area, because the PAMPANITO said that there were a large number of survivors in the water and that a lot of them were Australians. And sure enough, one of those ships that we had sunk had been a ship carrying a large number of Australian prisoners of war from Malaysia back to Japan for further imprisonment. There were, I guess, maybe a thousand prisoners. I'm not quite sure how many, but most of them were in the water. When we came steaming back into that area at sunset, I think it must have been about forty-eight hours later, there were still a large number of them in the area, and they were covered with fuel oil. Perhaps the fuel oil had shielded them from the heat of that awful sun down there. They were clinging to bits of debris and wreckage. I can recall their hollering, “Hey, Yank! Hey, Yank! Over here!” These men were dotted all over the expanse of the ocean, but I didn't see any sharks or anything, which was a surprise.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, could you take them on board the submarine?

Henry C. Lauerman:

We went back and picked up as many as we possibly could. We picked up about sixty. I think that the PAMPANITO picked up about the same number. We rigged out the bow planes on the surface and steamed along and threw a line to some guys that could help themselves, and other guys we brought aboard. After having been in the prison camp, it was terrible that they had to be subjected to this kind of incident; and we couldn't take them all. I guess the saddest experience of all my life was when we turned

around and headed for home. The sun was going down and there was not a could in the sky. The sea was calm off the coast of China and there were guys saying, “Hey, Yank! Over here! Hey, Yank! Over here!”

Donald R. Lennon:

There were no other American vessels in the area at all?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Two days later, another submarine got there and picked up a handful; that was all that was left out of, I bet, three or four hundred. What are you going to do? Maybe we should have stayed there, I don't know. But we were off the coast of Japan, and if we had taken too many men aboard, we couldn't have maneuvered the submarine. If an enemy plan had flown over and we'd had all the guys on deck, what would we have done, dive and leave all these guys on deck? There was no room for them down below. We wouldn't have had time to get them down below anyway before some airplane had dropped a bomb. What do you do? This is the kind of decision that you had to make. But as I say, it was a sad moment, a sad moment. Knowing that we ourselves had sunk the ship in which these men were being hauled back to Japan made it particularly sad for us.

Now, of course, I am very soft-hearted guy and I never liked to sink any ship. As I said, we had problems identifying ships. Most commanding officers would say, “Take a look at this.” They wanted somebody else to take a look at it if there was time and we weren't too pressed. I would look out there either before or after the torpedoes were fired and see this ship coming, and I would always think to myself, “This is a hell of a way to run the railroad.” Here this ship was coming, and, of course, the destroyer over there was looking for you...but it's a hell of a way to run the railroad. But there you are.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, when you are being depth-charged and there are a couple of antisubmarine destroyers above, how do you know when the coast is clear?

Henry C. Lauerman:

The standard attack tactic is to put the escort abaft your beam and make certain it stays there. As long as the escort is abaft--that is the antisubmarine vessel--the chances are you're opening on them. So you just keep it there until finally you are quite certain. The depth charges grown less and less loud, and there is less and less jarring; so, you think that they probably aren't too close and that they have probably lost contact. Of course, they're circling on some kind of pattern trying to regain contact. Your hope then is that they just don't accidentally pick up the contact again or that you don't do anything to pick up the contact.

It was always very difficult to determine exactly where the escort vessel was. The submarine sonar men kept turning up the volume on their equipment. They kept looking for a safe haven; they didn't want to take any chances. After we had been depth charged, the sonar men were very apt to tell the captain every time that the escort vessel picked up a little speed or changed a little bit in direction. They would say, “Captain, I think he's closing; I think he's closing.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you could hear when the sonar vessel at the surface picked up.

Henry C. Lauerman:

Yes, we could hear the screws. And the captain would say, “Let me hear it.” And then he might take the head phones or put it on the amplifier. Normally, he wouldn't put it on the amplifier, because he didn't want to make any noise. But he would say, “Let me hear it.” Well, then the sonar men would turn up the volume and then the captain would say, “Yeah, I think that we might be getting closer.” Well actually, it was a superabundance of caution, because when we'd finally stick up our periscope three or

four or five hours later, there'd be nothing in sight. Now, whether or not the escort vessels had gone off or what, we were never quite certain. After you've gone along for two, three, or four hours at slow speed, three knots, and you're twelve miles from the point of initial contact, by that time you were quite certain that you were avoided.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now you said that many of the Japanese vessels early in the war did not have radar. Did they depend solely on sonar?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Yes. That gave us a tremendous advantage at night and in conditions of reduced visibility. The HALIBUT was one of the first ships to have what was known as the SJ radar. We went out on a bright moonlit night and detected a ship. It was beautiful, clear, moonlit night in the South Pacific. We took position about eight or nine thousand yards ahead and then we went down. It was so bright we knew that they would see us, so there was nothing to do but submerge. You cold see this ship through the periscope, but of course, you couldn't get any ranges, and that is very important. You know the direction of the ship through the periscope, but a submerged submarine at night trying to make a periscope attack is very difficult. But we could run with our radar exposed and the rest of the submarine submerged, and this then gave us a means for taking ranges. It was like shooting a fish in a barrel. Of course, you see, the merchant ships and most of the warships didn't have any radar, so they couldn't detect us when we were on the surface.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, your radar would work only when it was above water.

Henry C. Lauerman:

Yes, radar only works when it is exposed. Later on in the war, the Japanese got some. In the letter there, Mr. Cuger mentions the fact that there was a pulse detected. Well, that was the radar pulse from the U.S.S. SEA LION. Mr. Cuger and the crew of the Japanese battleship CONGO thought it was from one of our patrolling aircrafts. Actually,

it was from the submarine SEA LION. So they got some sophisticated gear for detecting radar pulses. By this time, the CONGO and all the principal battleships had radar themselves. Well, what else would you like to know?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I do want, somewhere along the way, for you tell us a little about the South American duty of the ERIE.

Henry C. Lauerman:

Well, hat was a fascinating experience. I was an ensign and unmarried. Our principal function, as I said, was to show the flag. Now, in those days before World War II, the military were in a little different status than they are today. The military, so far as the Navy was concerned, particularly in Asia and in South America, were the principal representatives of the United States government. I can recall particularly on incident that occurred.

There was a political problem in Ecuador. The regime, which was friendly to the United States at that time, was afraid that the opposition forces in Ecuador were about to stage some kind of coup d'etat. So they asked the United State to suggest some possible ways to hold this coup off for a while until some remedial measures could be taken. Well, what was done was to devise a trip for the commander in chief of the Ecuadorian Army to visit the Galapagos Islands. The U.S.S. ERIE arrived at the port of Guayquil early one day, and the commander in chief of the Armed Forces of Ecuador had no excuses except to go out and visit the Galapagos Islands, a possession of Ecuador.

We stayed there for three or four days exploring the islands and looking at those great tortoises that they have and some of the relics that were there from by-gone days. We also made certain that the little station they had, which must have had twenty men, was on the job and properly equipped for whatever it was supposed to do. Then we

brought the commander in chief of the Armed Forces back to Quito, and, by that time, there was no question but that the inauguration of the duly-elected president was going ahead. The officers of the ship were the official United States delegation to all of the inauguration festivities up at the town of Quito. We went up there in our full-dress regalia and wined and dined and had a great time.

Well now, this was the kind of thing that went on before World War II, and it was sort of a romantic kind of thing. Of course, this sort of thing just doesn't go on anymore. We've gotten far more sophisticated in our approach to politics, and the countries of Latin America understand they are much different now than they were then. But the Banana Squadron in its day, was a very romantic and a very lovely place for a single naval officer to be.

That was one of the reasons that I mentioned at the start of our conversation the difference between submarining today and submarining as it was. I emphasized the mechanization and the automation of modern submarines. I mentioned, too, the fact that submarines today submerge and stay submerged, and that is monotonous. Whereas, when I was in submarines, we would submerge during daylight hours when we were actually on station; but most of the time, the submarine acted as a surface ship and was on the surface. It would only submerge when it was, shall we say, right in the enemy's backyard and, then, only during daylight hours. Although we would go out for a two-month patrol (sixty-day patrol), of that time, we would be thirty days on station and submerged only during the daylight hours and sometimes not eve then, depending upon where we were. If we thought that we were in an area where enemy aircraft operations were light, and if we were fairly certain that we could spot the aircraft by our radar and lookouts before it

would spot us, so that we could submerge, we'd stay up on the surface even during daylight hours. So, actually, we had a wide variety of environment from which we operated. Now, the nuclear submarines are true submersibles, whereas the fleet-type submarine was a surface ship, in a sense, that submerged. The present ones are true submersibles, which becomes very monotonous, and they are having great difficulty keeping the kind of men they want in submarines today.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, what has been the use made of submarines since the end of World War II? It seems to me that in Korea and in Vietnam, of course, surface vessels had been used, but how?

Henry C. Lauerman:

They were used very little insofar as combat was concerned, very little. They have been used in ancillary operations, I'm sure. They have been used oftentimes, shall we say, as they were used in World War II. I was in Washington during the Korean War. I had commanded the ARGONAUT in New London from 1940-1950. I was in Washington doing what might be called secretarial work in the office of the secretary. I was in legislative liaison work and things of this kind, so I don't really know to what use the commander in chief of the Pacific put the submarines in the Korean War. But they might have been used--now this is pure speculation on my part--for certain cladestine operations. We did a great deal of work while I commanded the ARGONAUT, immediately before the Korean War, putting various raiding parties ashore and this kind of thing. And I would be much surprised if you would not find that submarines were used a great deal in the Western pacific along the shores of Korea putting ashore special parties of this kind. But I don't know any of the details of those operations.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would you be willing to elaborate on your service on the ARGONAUT?

Henry C. Lauerman:

As you know, the submarine base at New London is the principal submarine base of the United States Navy; and it also is the basic training command for training submarine officers. So the principal duty of submarines at New London is training. At least the ARGONAUT's principal duty was training. So the operations there were local, for the most part. We also went out on fleet exercises and this kind of thing, but it might be called, more or less, routine submarine operations.

I really wasn't prepared to talk about this, but now that you mention it... one of the most memorable incidents was an occasion wherein we were conducting antisubmarine operations with the Atlantic Fleet. As you may have gathered from reading this book on submarine operations in World War II were rather elementary, so during the period that I had command of the ARGONAUT we tried to improve our wolfpack techniques. We had a little more sophisticated equipment, and we were trying to improve coordination between submarines in the course of the attack. We felt the Germans had done a great deal along this line, and we weren't quite satisfied with our proficiency in this regard.

At any rate, I was commander of a group of two or three submarines, and I had laid out certain plans of operation. We detected a target rather close to our submarine one afternoon. We were operating submerged, and we were making an attack on a ship that was coming our way in the course of these exercises. We thought we detected another ship in the vicinity that was very close aboard. Sure enough, when we got back to port, we found out that another one of the submarines had been precisely the same spot that we had been in and at the same particular time. We must have come within an ace of colliding under water. I often thought this was not a very comfortable kind of operating,

and that's one of the reasons why most submariners don't like to operate in a pack. With the equipment we had then, we could not maintain our position relative to one another with any degree of accuracy at all. Now, I don't really know whether or not that condition had been corrected. But that was a rather interesting incident that occurred.

Donald R. Lennon:

In reference to the ARGONAUT, you said that you did take part in putting people ashore?

Henry C. Lauerman:

Oh, yes. We used to have the Marines come aboard in these landing exercises. We would flood the escape hatch forward, and each man would swim out submerged with their aqualungs and swim ashore. Sometimes we'd put them ashore with a small boat at night. But we also practiced going in and releasing these men while submerged. Then we would go out to the shore and rendezvous with them later on and pick them up. Of course, that was done by the Germans, as you know, during World War II off our own coast. So we were doing much the same thing. We did it on the Normandy operations too, I think, and all over the world.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were doing this in '48 and '50, this was for exercise purposes.

Henry C. Lauerman:

This was for exercise purposes only. Usually off our own coast up around Maine or someplace.

This isn't apropos of anything that I've done, but I'm not convinced about anything. I would not be at all surprised if this recent submarine that was detected in the fiord was not an American submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you know they were saying that it was probably Russian.

Henry C. Lauerman:

Well, if you were the Norwegian government and had been friendly with the United States Navy and the United States government for a long time, and if the United

States Navy had been supplying you with considerable torpedo boats and whatnot through the military aid and assistance, and there was word that there was a submarine in the fiord and you knew that it would be embarrassing to the United States if it were to be found that it was a United States submarine, would you say it was a United States submarine?

Donald R. Lennon:

They just let them sail out.

Henry C. Lauerman:

I don't know whether they let them sail out or not. They might very well have. I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what they said.

Henry C. Lauerman:

It rather think that that might very well have been. Now, you say, “Why is an American submarine there?” Well, I don't know why an American submarine was there. I'm not going to speculate on that. But I think that I would not be surprised. I'm not saying it was; I don't have any knowledge of it at all, but I'm not sure it was a Russian submarine. It might have been. I don't know what use is going to be made of these tapes, but we have to be doing these things. In other words, we have to be exploring the fiords of Norway. It should have been an American submarine. We've got to know what the configuration at the bottom of these areas are, until such time as we decide for certain that our submarines will not be operating in these waters or that nuclear weapons are going to be banned. When we reach that point, then we don't have to have these clandestine operations--clandestine excursions--into waters adjacent to the various nations nor the airspace above them, or wherever we happen to be. Otherwise, we have got the probing. You aren't doing your job if you don't. So I would hope that it was an American submarine. I'm glad that Norwegians had the decency not to embarrass us.

You have these layers of water at different temperatures and it's almost impossible to detect an underwater object under those circumstances. The radar doesn't work, that is, radio propagation is nil under water; so all that you have is some kind of sonic device. You might have some magnetic detection, but that's very erratic, unless it's been improved. But the sound is refracted and reflected off these thermal layers. That's the reason some rings are very hard to detect. I guess that's about all.

One of the exciting parts of my career was my last tour of duty in command of the U.S.S. MOUNT McKINLEY, which was an amphibious command ship. That was fascinating duty. We went over to the Mediterranean and operated there with the Sixth Fleet. I found it to be extraordinarily interesting duty and very interesting crews, because of the fact it was so apparent to me that our Navy was so obsolete.

I think of our Navy as it was when World War II began; it was obsolete. Mr. Roosevelt had just begun a big naval construction program, part of the recovery from the depression of the thirties as well as a part of our rearming program. We had time to get the construction program on the way and to have a semblance of a fighting force. When the Japanese struck and our shipyards were all in operation and everything was going full blast, it just meant really shifting over to wartime production. We had time, but our fleet really didn't begin to shape up until about 1944. We had about two years. They aren't going to have that time next time; and I'm very much concerned about the fact that we are still trying to operate ships of World War II vintage that are broken down. They're decrepit and inefficient, and, yet, we expect the men to perform as if, shall we say, they are operating first-line equipment. I was terribly proud of the way in which all of the men

of the amphibious command operated when I was attached to that command, particularly my own ship, and the deprivation and the lack of comforts that those men tolerated.

[End of Interview]