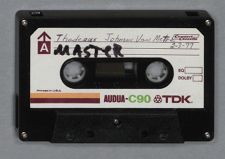

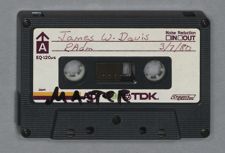

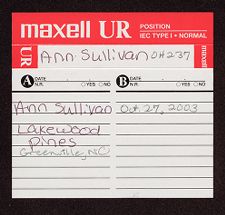

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| T. J. VAN METRE | |

| FEBRUARY 3, 1977 |

T.J. Van Metre:

Upon graduation from the Naval Academy in 1930, I and three other bridge players were ordered to the battleship UTAH. This was such a disappointment to the Navy that they decommissioned the UTAH and my orders were changed to the DETROIT, where I was assistant anti-aircraft officer for a period of six months.

In January, 1931, I was ordered to the battleship PENNSYLVANIA which was in overhaul for a remodernization in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Connected with this modernization was the installation of, I believe, the first five-inch twenty-five caliber anti-aircraft battery. I was sent cross-country to the state of Colorado to an anti-aircraft school in preparation for rejoining the PENNSYLVANIA when she came around to the West Coast. It was a fascinating experience on the PENNSYLVANIA with the new five-inch twenty-five caliber battery.

I stayed on the PENNSYLVANIA for some thirty months and was then ordered to the destroyer HERBERT. There I assumed the duties of engineering officer on that ship. The HERBERT came through the canal about a year after I reported on board and we joined the training squadron in the Atlantic spending most of our time cruising reserves and making ceremonial calls up and down the East Coast.

From the HERBERT, I went to Admiral Cluverius' staff in Philadelphia's Fourth Naval District, where I was instructor of the Naval Reserves and the Merchant Marine Naval Reserve Enrollment Officer. During the war, I met many of these Merchant Marine officers that I had given commissions to. They were not my best friends at this time, as their con-temporaries in the Merchant Marines were making about four times as much money as they were in the Navy as lieutenant commanders and lieutenants. However, it was a fascinating tour of duty.

While on Admiral Cluverius's staff, I made the mistake of walking past the detail officer's office in Washington one day. I asked him where I would go after I left the staff and he said, "How about China?" I made some flip remark which resulted in my getting orders to China about ten days later. This created a problem, as I had been courting Miss Madeline McCormick for about eight or nine months. It resulted in my marriage in a very short time in order that I could get her transportation to China with me. We had a fine honeymoon with two years in China while I was attached to the TULSA, a coastal gunboat. This was a fascinating tour of duty as the TULSA's orders kept her traveling up and down the China coast with a yearly call at Manila for overhaul. Our time was spent roughly one-quarter in Hong Kong and one-quarter in Amoy and one-quarter in Swatow with the other one-quarter going into North China.

Donald R. Lennon:

What years were involved here?

T.J. Van Metre:

This was from December 1938 until December 1940.

Donald R. Lennon:

The major purpose there--was it to show the flag, or were you defending the China coastline, or just what was ordered?

T.J. Van Metre:

Much of this duty was in connection with showing the flag. However, it is interesting to note that the Japanese had occupied northern China at that time and had partially occupied and were still attacking around Amoy. In particular, one of our sessions there in the summer or fall of 1939, we were sent to Amoy and placed ashore a forty-man landing party as the Japanese had put a forty-man landing party on the island of Ku Lang Su. The British also put a landing force over there. This was in retaliation to the Japanese trying to take over. Ku Lang Su was an International Settlement with no vested rights by any one country.

One interesting incident that occurred in Ku Lang Su at this time concerned my wife who was by this time some seven or eight months pregnant. Our hotel, which was the best and only hotel in Ku Lang Su but very poor by our standards, was directly across from a hospital where the Japanese quartered their landing force. Ku Lang Su had narrow streets and consequently all transportation was either by walking or sedan chairs. One evening we were returning to our hotel and as we became opposite the gate into the hospital, a Japanese sentry dropped his bayonet directly at my wife's midsection. Fortunately, I controlled my temper; but primarily because this was shortly after the Massey Incident which the Japanese had created at the time, which nearly resulted in an international incident.

During this time up and down the China coast, my wife traveled on twenty-five merchant ships following the TULSA. In the meantime, she delivered our one son at the Top of the Peak in Hong Kong. In the fall of 1940, the ship was in Manila and made a cruise to the southern Philippines at the time most of all of the Army and Navy dependents were evacuated.

About this time, I failed my annual physical exam due to poor eye-sight and a vindictive doctor. I ended up in a hospital before a physical evaluation board at Cavite. I was then ordered back to the nearest Naval hospital in the United States. This became unknowingly a rather good break, as I came back with my wife and child and fifty-two hundred plus Navy dependents on the S.S. WASHINGTON.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we get away from the China Station, I would like to ask a couple of questions concerning this incident. Were the Japanese attempting with their landing parties to take control of the island?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. They did not expect us to put forces ashore. With none of our forces ashore, they would have, of course, the island, I believe. However, I am fuzzy on that.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, with the British and American forces there, this prevented a takeover?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. We put just exactly an equal number of men there to balance the forces.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, with the incident with the Japanese sentry and his bayonet, how was that resolved?

T.J. Van Metre:

Nothing. That was the end of it. We went on into our hotel. I simply reported this to my commanding officer, but there was nothing that we could do about incidents like that. You may remember that I referred to the Massey Incident. I've forgotten which port it was in; but Massey, who was a lieutenant junior grade or possibly a lieutenant at this time, had had this unfortunate experience of having his wife supposedly attacked in Hawaii sometime before this. He and some of his sailors castrated the Hawaiian who had violated his wife. He

was, in turn, in the Asiatic Fleet and in one of the ports. His new wife was slapped by a Japanese sentry on the dock. Massey, with his temper, struck the Japanese sentry which did result in an international incident between the United States and Japan.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you home-ported during this time?

T.J. Van Metre:

Hong Kong was our home port.

Donald R. Lennon:

Mrs. Van Metre did not remain in Hong Kong? She followed you?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. She followed the fleet.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you put into a port, you would usually stay there a week or two before you moved on down the coast?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. We'd stay normally two to three weeks in Amoy and two or three weeks in Swatow, and two or three weeks in Hong Kong. Once a year we would make a trip up north. One of our ports, for instance, being Chinwangtao and Tientsin. Then once a year we would go to Manila for a ship overhaul in the Cavite Navy Yard.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other particular experiences that you recall while there in China?

T.J. Van Metre:

Life was beautiful at this time for the Navy in the China area. When we arrived in 1938 the exchange was six to one. When we left, as I remember, it was 21 to 1. In the meantime, although the currency was inflated, the price of the goods was of pre-war quality and a tremendous bargain. A civilian suit, for instance, could be tailored out of good British materials for around three dollars. Of course, Britain was in the war in 1940. In Hong Kong, all the British wives had been evacuated. This left beautiful quarters at very much of a bargain price, although we lived in two rooms of the Peninsula Hotel most of the time we were there. I returned to Hong Kong one time to

have my wife meet me on the dock and tell me she had sublet an apartment. The apartment was unbelievable! It was a corner apartment in a very fine apartment house with a veranda around two sides. It was equipped with two bedrooms and two baths, and a living room in which we gave a party for some sixty people and were not crowded. It had a dining room and a pantry. It was so fancy, there was no kitchen in the apartment house itself. The kitchen was in an adjacent building which required a walkway to the apartment. Consequently, there were no kitchen odors. The apartment was beautifully furnished with Wedgwood china, and our total rental was fifty dollars a month including utilities. At this time, also, we had four servants. We had a number one boy, a mascularly, a baby amah, and a washy amah. It was truly "living it up." But, as the Navy goes, it was so frequently from feast to famine and vice versa. My wife came back from that type of living to a room in a private home in Philadelphia where she had just one room and small kitchen on the second floor of the home, and a bedroom on the third floor.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the attitude of the Chinese people towards the Navy at that time?

T.J. Van Metre:

They were marvelous. We and all the Navy people became very, very fond of all the Chinese people and the Chinese liked the American people. The relations of the Chinese with the Navy were superb at this time. The amahs who took care of the babies were super. Of course, they preferred to take care of a man-child rather than a girl-child. As a matter of fact, there were two incidents while we were there where an amah was so fond of her baby charge that when the mother was returning to the U.S., the amah jumped overboard with the baby and drowned just for fear of losing her child.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the baby drown too?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. It was a sad thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there much turmoil in China at this time as there was with the Japanese?

T.J. Van Metre:

Oh yes. Interestingly, while at anchor at Amoy, in Amoy Harbor, we would frequently sit on the deck after dinner at sunset and watch the Japanese planes come in and bomb the mainland just a mile or two away from where we were anchored. On one of the trips south that my wife made on a merchant ship, they put into Swatow and secured to a dock there. The Japanese attacked and a bomb actually hit the dock to which the ship was attached at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the merchant ship flying the American flag or was it a Chinese vessel?

T.J. Van Metre:

I don't know whether this was an American vessel or what. She was on all kinds of nationalities.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there much harassment of the Americans or the other foreigners by the Japanese or did they try to give you a clear berth?

T.J. Van Metre:

We had very little interference. Of course, by this time in Hong Kong the British were at war. Also, the Germans, of which there were several in Hong Kong, had evacuated. Some had a rather rough trip from Hong Kong trying to get back to Germany. One in particular, I remember seeing in Amoy who had successfully gotten out of Hong Kong. Any Germans who were caught there had, of course, been interned by the British. Then later, after the Japanese had occupied Hong Kong, all of our British friends who were left there were interned by the Japanese. Although the military families had been evacuated, the

civilians were still there in great numbers. I made a trip back to Hong Kong in 1949 and ran into several of our friends who had been interned the entire war there.

The Chinese are uncanny in their grapevine. As I've said before, our child was born there in December of 1939. We left in the latter part of 1940. When I got back into Hong Kong in 1949 with a tanker, so help me, my orders did not designate Hong Kong as a port until after we had left Japan. By dispatch orders, I was given my choice of ports for two days leave and recreation for the crew on the way to the Persian Gulf. We moored in Hong Kong Harbor to a buoy. While I was still on the bridge, a messenger came up to me and said that a China-man was down at the gangway who said he had been my bootmaker when I was in China before the war. His name was Jameson. Sure enough, Jameson had been my bootmaker. He came on board. I went down to see him, and the first thing he handed me was. a pair of boots for my manchild who had left before he was a year old. So help me, they fit him.

The Chinese were just uncanny.. I used to question this to a degree and try out my Chinese messboy on the TULSA. I would come aboard and think, "What would I like for breakfast this morning?" Invariably it seemed that whatever I had decided I wanted for breakfast would be on the table after I had changed clothes and gone into the wardroom. It was just uncanny. They were just beautiful. Well, that about finishes China.

Donald R. Lennon:

You can start back about being evacuated on the WASHINGTON.

T.J. Van Metre:

Coming back was a harrowing experience. With the fifty-two hundred women and children on the ship, Lt. Price and I were given sealed orders

with thirty Marines and twenty sailors or vice versa because of the dock strikes that were occurring at this time in San Francisco. The captain of the ship S. S. WASHINGTON owned by the U.S. Lines had become a hero in the Atlantic by effecting a daring rescue at sea. The publicity had evidently gone to his head, and he decided on this trip from Manila to San Francisco that he would break the transit record for the Pacific. We left the harbor at Manila and immediately went to full-speed. Up around the Aleutians we hit some very, very rough weather. Lieutenant Price and I protested the speed to the captain and asked him to slow down or change course because it was dangerous for the women and children who were being evacuated. The captain told us in no uncertain terms that he needed no advice from a couple of Navy lieutenants. In the. morning, while the women and children were in the dining room having breakfast, without slowing down, he decided to make a course change which resulted in all the women and children in the dining room ending up on one side of the dining room on the floor, There were several broken bones, screams and general bedlam. We received no apology from the captain, but he did, I believe, slow down a bit after that. We were at that time not on speaking terms. It resulted, how-ever, in Lieutenant Price and his wife, my wife and me going from room to room that prior night trying to quiet down the frightened women and children who were on the ship. When we arrived in San Francisco, we immediately marched our troops out on the dock with fixed bayonets, We had absolutely no trouble with the dock strikers and managed to successfully get all the women and children off the ship. It took some time to get them through customs and started on their way home. The captain of the S. S. WASHINGTON was Captain Manning.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you able to make any kind of a report on him?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. But I never knew what became of it.

Arriving in San Francisco with my orders to the hospital in San Francisco, I had requested that the orders be modified to the Naval hospital in Philadelphia as that was my wife's home. The bureau cooperated in changing the orders, providing it was at no additional cost to the government. So, I paid our way across country. Fortunately, I was able to beat the rap on the physical disqualification with the physical evaluation board in Philadelphia and was returned to full duty and ordered to the NORTH CAROLINA which was being built in the New York Navy Yard.

I had quite a career on the U.S.S. NORTH CAROLINA, reporting aboard as assistant damage control officer and assistant first lieutenant. The ship was put into commission on 9 April, 1941. At that time, I was the electrical officer, Next, I became main propulsion assistant, then assistant engineer. Next, I went to the gunnery department where I was main battery officer and assistant gunnery officer, Then, I relieved as communication officer of the ship and finally navigator. As there was very little for a navigator to do while in port, I volunteered to take over the ship's service and the ship's service officer during the time I served as navigator. I believe all of the NORTH CAROLINA's history is a matter of record with you.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about particular incidents that you remember concerning your service there.--those things that stand out in your mind, either people, particular battles, incidents, or anecdotes that are probably not part of the history?

T.J. Van Metre:

There were several anecdotes. The NORTH CAROLINA, of course, had a wonderful war record. We were really busy out there most of the war. As navigator, I generally conned the ship in battle while the captain was in overall command. One of my funny incidents and the only wound that I ever received was with testing out a pair of binoculars with big rubber eye pieces. While up at the slit in the conning tower at night, I decided to try out my binoculars with the heavy rubber eye-pieces while number two turret was firing a salvo. It so happened that just before the salvo went off, I remarked to the captain, "I may get knocked on my ass with this." Sure enough, when the turret fired, the concussion knocked me clear across the conning tower with a slight cut over one of my eyes. I immediately screamed that I was eligible for a purple heart, but the captain wouldn't cooperate.

The most harrowing incident I had and for most of us on the NORTH CAROLINA was the result of the torpedo which tore our whole port side forward out. At the time, most of the crew were sunbathing all over the topside. I was taking my sun bath on the top of the conning tower when the torpedo hit. The junior aviator was one of those individuals with a, very hairy body. In his bathing trunks he went past me going up the foremast. I said, "Where did it hit?"

His reply was, "R-r-r-r-right where I was 1-1-laying." I said, "Well, where were you laying?"

His reply was, "R-r-r-right where it hit!!!!!!"

At this time, I was the main battery officer. Smoke poured out of the forward turret and I went down there. The turret had been evacuated. Some smoke was still apparent. I decided that we should go down and see

what the damage was at the time, and also see if we could turn the sprinklers and flooding off which, of course, had been turned on with the hit onto the magazines. The chief turret captain refused to go back in the turret for which I could not blame him. He had been in there and seen the fire and smoke inside the turret when the torpedo hit. I did, however, get a first class turret captain and turret striker to go down into the turret with me. Down at the magazine level, it was water covered by oil up about waist high. We felt the bulkheads and found no heat; and after about thirty to forty minutes down there, we reported this fact and had the sprinklers and flooding stopped. We were then able to proceed at some twenty-five knots towards Pearl Harbor. I confess that when I was halfway down that turret with no lights and nothing but a hand lantern in my hands, I wondered what the hell I was doing going down there.

The day of the turkey shoot was another highlight, of course, for all of us on the ship. It so happened that that day, I had a touch of ptomaine poisoning and conned the ship through the entire turkey shoot with a temperature of about 103 degrees. It might have been up there without the ptomaine poisoning, however. It was of short duration, and the elation over the success of our mission made me forget it. Our R and R was back in Pearl when we went in with the torpedo damage which then resulted in R and R. We also had another R and R when we had some propeller and shaft problem and had to go back to Pearl.

In the middle of the war our executive officer, Commander Red Thackrey was detached from the ship and the captain requested that he not be furnished a relief. He fleeted Commander Stryker up from navigator to executive officer, He fleeted me up to navigator. This

resulted, I believe, in Joe being the youngest executive of a capital ship at that time. However, things went fast in those days.

On the ship we had some most outstanding commanding officers, starting with Captain Hustvedt, who was truly one of the finest gentle-men I have ever known. He was relieved by Captain Badger, then Captain Fort, then Captain Baker, then Captain Thomas. My tour ended with Captain Thomas; and, with my bags packed, I met Captain Fahrion, who was Captain Thomas's relief, on the gangway. While I was leaving, he was reporting on board. Captain Fahrion was relieved by Captain Col-clough and he in turn by Captain Hanlon. I think it is interesting to note that with the exception of Captain Thomas, all these commanding officers attained flag rank.

One incident I can think of was when we were bombarding Kwajalein Island. It was a routine bombardment to simply lob shells onto the runways to prevent the Japanese planes from landing and refueling. Somebody in the foremast saw a tanker back at the far end of the lagoon which the Japanese had tried to camouflage. We shifted our fire for a few minutes and scratched one tanker. This was simply a bonus for the evening.

Another amusing incident I can think of, was coming out of Majuro one afternoon while Captain Thomas was commanding. This was quite a narrow entrance or exit from the harbor with a strong current. Consequently, we needed speed to maintain our course. An LST was patrolling outside the entrance and was on a collision course with us as we were coming out. The captain had to stop engines, much to his distress, to let the LST clear. He indignantly sent a message to the LST saying,

"Are you familiar with the rules of the road?" The answer came back, "NEGATIVE." That was rough duty on those LST's and LCT's and those little ships that were just out there and just up and down and stuff like that! Most of them had young reserve officers who had never been to sea; and boy I'll tell you, they did a job, Those reserve officers were something! It was something how they having never seen the sea, could come out and do such. Believe me, I had much, much admiration for our reservists.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about in combat conditions such as the turkey shoot or any of the other combat patrols that you were on, any other points that could be highlighted concerning these?

T.J. Van Metre:

Oh, I don't know, you've probably got all of those down.

Donald R. Lennon:

The NORTH CAROLINA was considered not necessarily superior to the other battleships, but there seemed to be a certain matter of mystique about it. At least the men who served aboard it seemed to think there was.

T.J. Van Metre:

Well, we were reported sunk and missing so often. Of course, there was an intense rivalry among the newer battleships throughout the entire war. I don't think any of it was detrimental to our war effort. For instance, before we went into commission, the WASHINGTON in the Philadelphia Navy Yard and we in the New York Navy Yard were both determined to be ready for sea first, It did create quite a rivalry, although it was friendly. Some of the WASHINGTON planners did work for the NORTH CAROLINA, and we in turn did work for the WASHINGTON. For instance, when I first reported aboard as assistant damage control officer, my job was to mark all the hatches and doors X, Y and Z for

damage control. I did this for both the WASHINGTON and the NORTH CAROLINA, and it was a hell of a job! After pouring for days and days over blueprints, I finally decided the only real way to do it was simply go down into the bilges into the double bottoms and start out with a piece of chalk and mark the doors as I came out. Consequently, I think I touched every inch of that ship while I was on board.

To my recollection, one of the stories that is told about the nickname "Showboat" is a fallacy. I remember the NORTH CAROLINA obtained her name "Showboat" in Norfolk. Of course, being in New York with the attended publicity gave the NORTH CAROLINA more publicity than the WASHINGTON got in Philadelphia, Our trips on training exercises taking people like Walter Winchell and all the top New York correspondents, was magnified. The time we fired the huge broadside salvo resulted in much publicity. The first time I remember our being referred to as the "Showboat" was later when we entered Hampton Roads. The WASHINGTON was at anchor there and the WASHINGTON band immediately struck up the tune, "Here comes that Showboat." From then on, everyone called us the "Showboat," and we called ourselves the "Showboat." I believe, however, that was the origination of the name.

Of course, another intense rivalry and probably the most intense rivalry among the new battleships was between the WASHINGTON and the SOUTH DAKOTA who were together in the night engagement at Guadalcanal. With our friendly rivalry with the WASHINGTON, I believe the WASHINGTON's story that the SOUTH DAKOTA did not help tremendously in this battle. As the story went, the WASHINGTON requested the SOUTH DAKOTA to quit firing because they were silhouetting the WASHINGTON for the Japanese

to fire at. Nevertheless, the SOUTH DAKOTA came back to the United States and received much, much publicity as "Battleship X." This was much to the disgust of those of us who were still fighting the war out in the Pacific. The WASHINGTON and NORTH CAROLINA rivalries were very friendly and kept around the officers' club when we would get together. It was mostly kidding. The rivalry, however, was very intense between the SOUTH DAKOTA and the WASHINGTON. Some hard feelings developed. We, of course, were on the WASHINGTON's side.

One incident which furnished me great amusement and satisfaction was at the dock in Ulithi one night with practically the whole fleet in the harbor. We were over at the little officers' club and our captain, who was the senior commanding officer of any ship in the harbor, had gone back to the ship early. He told me he would send a gig back for me and the other officers who were there. When we were ready to go down, we went down to the dock, and the SOUTH DAKOTA gig was approaching the dock. I told the patrol officer to call the NORTH CAROLINA gig. He immediately waved the SOUTH DAKOTA gig off and waved the NORTH CAROLINA gig in, of course, thinking that our captain was following me down to the dock. When two other officers and I started to get in the NORTH CAROLINA gig, the executive officer of the SOUTH DAKOTA, with some profanity, asked me what I was doing getting that gig along ahead of his because he was senior. My reply to him, which did not enhance our friendship was, "If you stayed out here in the Pacific and fought instead of playing Battleship X for publicity purposes, you would know how to do these things too." We were never very friendly after that.

Joe Stryker and I were always very close friends. We always took our noon sunbaths together on the top of the conning tower. We are still friends. His son and my son were classmates at the Naval Academy. Both went into nuclear submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

I reckon the greatest future in the Navy now is in nuclear submarines.

T.J. Van Metre:

Oh yes, by far.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your feeling at leaving the U.S.S. NORTH CAROLINA when you were relieved there in 1944?

T.J. Van Metre:

Actually, I had been navigator for the NORTH CAROLINA for two years. I felt that was long enough for any one job during wartime. It was a gentleman's job and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Frankly, I was afraid I would get careless with the knowledge of the job. I actually asked to be relieved, which brings up another story. We were in Bremerton at the time with the NORTH CAROLINA undergoing overhaul. My wife had succeeded in coming with our child from Philadelphia to Bremerton. She had always wanted me to get duty at Annapolis. One afternoon, I was over in our apartment and a messenger from the ship brought a telegram from Joe Daniel, the detail officer in the Bureau of Naval Personnel. I opened the telegram with my wife reading over my shoulder. It said, "You have the choice of your two first preferences: Shore duty Annapolis, or command of a destroyer. Please advise." My wife was gleeful until I told her that a regular officer could not ask for shore duty during wartime. My wife has never completely forgiven me for going across country to Iran to pick up a destroyer. However, I felt then and still feel strongly that regular officers should have

been at sea and the shore billets taken care of by reservists and civilians in so far as possible.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, it probably would have hurt your career to have turned down the opportunity to be commander of a destroyer?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes. I relieved in command of the HILLERY P. JONES in December of 1944, and made a convoy trip back to the states and one other convoy trip across the Atlantic with the HILLERY P. JONES.

Donald R. Lennon:

You picked it up in Iran?

T.J. Van Metre:

Yes, I flew across and got it there. Unfortunately, the convoy that I took over was an eight-knot convoy with several nationalities involved. I was in command of the screen. The seas were rough and it was not a pleasant voyage. Also, about a day out of Gibraltar, one of my officers contracted acute appendicitis. The seas were so rough that our young doctor on board feared operating. I turned the screen over to the next senior officer, and rushed into Gibraltar, being met by a boat in the harbor to transfer the young officer whose appendix had burst by this time. However, he recovered and rejoined the ship at a later date.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any problem in adjusting from battleship to destroyer after being on board a battleship for so long?

T.J. Van Metre:

Oh, in a way; but there is nothing like command. I enjoyed that destroyer. I really enjoyed that destroyer! After this convoy trip, we had a short overhaul period and some modernization in the New York Navy Yard which brings up one of my other amusing incidents in the Navy. As I had put the NORTH CAROLINA into commission as electrical officer, I knew the civilian electrical work force quite well in the navy yard.

During the war, one of the items which was in extremely short supply throughout the fleet were the sound-powered telephones. With the ship in the navy yard, I contacted some of my civilian friends which resulted in my getting a full allowance of sound-powered phones for the HILLERY P. JONES. It was reported to me that my chief machinist's mate made the remark, "Here we have the only old man in the Navy who can be heard from the bridge down to the engine room with all the hatches battened down with no phones and we are the only ship in the Navy with a full allowance of sound-powered telephones." I do have a voice that carries tremendously.

After our overhaul, we went back to the Pacific. The HILLERY P. JONES had received a unit citation prior to my reporting on board in the Mediterranean and it was a fine bombardment ship with a good crew. However, she had had no experience with the type of war we were conducting in the Pacific with the kamikazes and so forth. I was distressed with the amount of time it took to man the battery at general quarters. In spite of loud protests, I could never get the crew to realize the importance of getting on those guns quickly. A friend of mine was on duty at North Island; and when we put in there, I went over to see him. I asked him if when we got some fifty to a hundred miles off the coast on our way to the west Pacific, would he give us a combined attack with fighter planes, dive bombers, and torpedo planes. This was right up his alley because they liked to have this kind of training anyway. I didn't even tell my executive officer about this. I was the only person on the ship that knew we were going to get an attack. A radar contact was made on the attacking planes coming in; and, at the

report, I sounded the general alarm and ordered the crew to general quarters. I think it was the most fortunate thing I did during the war. Shortly, after the fighter planes had attacked, the dive bombers had attacked, and the torpedo planes had attacked, the word came, "Manned and ready." This, with a long speech from me, I think, impressed the crew with how important it was to man that battery fast. We would never have fired a gun had it been a Japanese attack. Needless-to-say, we worked on this and our efficiency with getting to general quarters improved greatly. As a matter of fact, I could become very proud of the crew, but it took something dramatic to make it sink in.

Most of our work in the Pacific was convoy duty with the HILLERY P. JONES. I happened to have gotten my command of a destroyer late and consequently was probably the senior commanding officer of a destroyer in the Pacific at that time. It resulted in my having command of the screen in most of our convoys which made a rather interesting tour. We were in on the southern occupation of Japan and also the northern occupation of Japan.

While picking up a convoy at the southern end of Tokyo Harbor, I allowed my crew, under escort, to go ashore in military formation. We found there a dump of Japanese firearms which resulted in my crew and the crews of the three other destroyers in my group obtaining sufficient rifles and Samurai swords and the like for all of us. Unfortunately, Admiral Halsey sent a message, after finding out about our landing force, prohibiting any further landings by way of the crews of the ships. I caught hell for that! We hit a bad typhoon with this

convoy going down the Leyte Gulf but successfully circled the perimeter of it with no damage to any ships.

I succeeded to the command of Destroyer Division Thirteen and then to Destroyer Squadron Seven. I then brought the Squadron back to Charleston for decommissioning at the end of the war.

[End of Interview]