[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL IITSTORY INTERVIEW WITH DRS. MALENE AND FRED IRONS May 12, 1999

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop

Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn

27 Total Pages

Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: My name is Ruth Moskop and I am at 100 Hickory Street in Greenville, North Carolina. I am here to talk to Dr. Fred Irons and Dr. Malene Irons. Do I have your permission, Dr. Fred, to record this interview?

FI: Yes, you do.

RM: Thanks and Dr. Malene?

MI: Oh, yes.

RM: You're ready?

MI: Indeed. Ready.

RM: Great. I was hoping we could pick up on a thread of conversation that we touched on last time we met, and that is the founding of the Nursing School at East Carolina University.

FI: Well, I can remember...at that time, I was a member of the Nursing Board...State Board of Nursing and ( ). We talked of the possibility of having a nursing school here. Dr. Furgurson from Plymouth was one of the people that was very much in favor of it. He had some long talks with Dr. Jenkins and they got together and decided that we'd better go up to Raleigh. We did. Dr. Jenkins and Dr. Bob Holt, who was the dean at that time...

MI: Academic.

FI: ...academic dean, and I went up there. Was there somebody else with us? (1:22, Part 1)

MI: I don't remember who went with you.

FI: Well, anyway.

RM: Did Dr. Furgurson take off and go, too?

FI: No. Dr. Furgurson wasn't with us. The driver, Dr. Jenkins, Dr. Holt, and I went. We talked to the Chief of the State Board of Nursing at that time. Do you remember what her name was, honey?

MI: I don't right now.

FI: Well, anyway. We had some long talks with her.

MI: She was a very pleasant lady.

FI: Yes, indeed she was.

MI: She had an office in Raleigh.

FI: Yeah. We came away feeling that we had made some progress.

RM: It was important to convince that office that...

FI: That's right-that we were in need for a nursing school here at East Carolina.

MI: They established it as a four-year nursing program, which made them have an extra year in understanding the management of a nursing program. Each one of them had BS's in nursing not RN's, the way it was established. (2:38, Part 1)

RM: I see.

MI: You see, RN's was a three-year program and we were mighty glad that they gave that extra academic year.

RM: Yes.

MI: And what they did, they took charge of the wards in the hospital. They were great.

RM: Now, who were they?

MI: The nursing graduates.

RM: I see.

MI: Of course, they worked in the hospital as in training processes. But, they took the jobs that were in charge and things were much better done than with the RNs who were very clever, helpful people, but they needed more training and they hadn't gotten it.

RM: In the management, that extra year made a difference.

MI: Made a difference.

RM: The extra Bachelor's year in addition to the RN.

MI: Yeah.

RM: Had there been a RN training program in the area before that? (3:32, Part 1)

MI: There had been one in the Pitt Hospital, but that had stopped existing. I don't know why it stopped, but when we moved into the new hospital, there was no training program. That was the little, new hospital.

RM: I understand. The red, brick one.

MI: Yeah.

FI: Yeah.

MI: But so much improved. They had wonderful rooms to sterilize things there. Just such a help. I don't know what they do with those now. It meant something to us to have everything, babies with sores, to have sterile sheets, things that were really necessary were done.

RM: Surely. Well, so you went to Raleigh to visit the State Board of Nursing and there must have been some procedures you had to go through with the university system to get the school established. (4:35)

FI: Yes. There was considerably conversation between the Greater University and the East Carolina University. At that time, it was felt that we needed it badly and the people in Chapel Hill weren't real sure that we needed it. So...

MI: Well, they had a very good program. They didn't have enough nurses, but they had a good program that was respected in the state. Duke lost its program a little while after that.

FI: Yeah.

RM: Is that right?

MI: They stopped it. They stopped it because they said...

FI: Terry Sanford did that. The nursing people were not very happy about it, but for some reason he thought that it was wise not to continue the School of Nursing at Duke. (5:43, Part 1)

MI: We have a lot of good graduates in this part of the state. Marion Bartlett was one in the nursing program at Duke. We knew the nurses scattered around and this part was one.

FI: Yeah.

MI: That was excellent. Nurses have to be good detail people.

RM: Yes.

MI: They have to know what's necessary.

RM: They have to pay attention.

MI: Urn-hum.

RM: Good observers.

MI: Right.

RM: What needs to be done. So, how long do you think it was between the time when you and Dr. Jenkins and Dr. Holt, was it...

FI: Yes.

RM: ...drove up to Raleigh?

MI: Bob Holt.

FI: Bob Holt, the academic dean.

RM: And the time you got your nursing school going?

FI: I don't know exactly how long that was.

MI: I don't either. I don't know exactly what year we got the nursing school.

RM: Well, we can look that up. (6:40, Part 1)

MI: It was somewhere between...that's too much space...but, between '50 and '65.

RM: Well, don't worry about that. Who else did you involve in the process? Did the ball sort of start rolling by itself or did you have to keep pushing it along?

FI: I think the main pusher was Dr. Leo Jenkins. He pushed it.

MI: He pushed sure enough.

FI: And Dr. Furgurson from Plymouth pushed it, too.

MI: I remember him making a statement to us, "I go to every commencement that I'm asked." He gave us a long number of commencements that he went to. He said, ..I preached the fact that we need doctors and nurses." I think that he was laying some good basic thinking that we did.

RM: This was Dr. Jenkins.

FI: Yes. That's exactly right.

MI: Dr. Jenkins. He made the speeches and they were good speeches and had a little humor in them. He was delightful. I don't mind saying that it would have been good to have him anywhere. He was a waver of banners, too. He was waving the banner of East Carolina to serve this section of the state. Without doctors and nurses, they weren't going to have it. (8:07, Part 1)

RM: So, he was very instrumental in the founding of the nursing school as well as...

MI: Yes.

RM: ...the medical school.

FI: Oh, yes. Absolutely.

MI: And every other new program we had. There's no telling what he did in business. I never kept up with that, but he changed it completely and those fellas are some great CPA's now. They're just as good as those from Chapel Hill.

RM: Surely. You mentioned a lady named, Louis?

FI: Yes.

RM: Mrs. Louis?

MI: Yes.

RM: Miss Louis.

MI: She never married. She was a very interesting person.

RM: What was her role in all of this?

MI: Eloise Louis.

PI: Well, are you sure she never married?

MI: I don't know.

RM: Let's just leave it at Eloise Louis.

PI: I think we better leave off the...

RM: We'll leave off the title.

PI: She was a very influential person and very much interested in nursing. She carried the banner for nursing as a profession and did a wonderful job. I haven't heard from her or talked with her in any recent years. I know she went down to UNC-Greensboro and was in charge of that nursing school down there. (9:34, Part 1)

RM: When you first had contact with her, where was she, Chapel Hill, I guess?

PI: Yes, she was at Chapel Hill.

MI: I think that the whole time that we were on the board, she was at Chapel Hill.

PI: I think she was. Yes.

MI: She had a vision of what was expected of nurses and she was putting that in.

RM: Was she the head of the program in Chapel Hill?

MI: She went there as the head. I feel sure she...She may be in Heaven by now. Fred knew her well when he was on the board. You were on the board what years, Fred?

PI: Well, let's see. Terry Sanford appointed me on the board, honey, and I came off when Governor Moore came in.

RM: That's close enough. You mentioned that Chapel Hill as an institution was not real enthusiastic about ECU having a nursing school. (10:34, Part 1)

PI: Well...

MI: They weren't. They weren't letting us have a med school. They said we got one that can serve Eastern Carolina. You know, they were about to convince me. I talked to Leo Jenkins and he began to show me how many less people we would get if they used the doctors and other professionals from UNC to tend to people here. They didn't have a four-year medical school when we came to Greenville. They got it in the 50's and their medical school had not been much understood, but it...

RM: This was Chapel Hill.

FI: Yeah.

MI: This was Chapel Hill, but they got the four-year medical school before '60. I think it was.

FI: Yeah.

MI: '55 or '56 in there. I had friends at Duke, who were personal friends, as well as, delightful, people and good doctors, who if I had something that was real puzzling...For instance, you don't know measles. Praise the Lord you don't. It existed a great deal and was a great curse while we were practicing. I would go to a house and there would be three or four children with measles and they'd all be praying the children were so sick. (11:58, Part 1)

RM: Oh, dear.

MI: Everything was terrible, but we watched them so because if they were going to get encephalitis, that cough would stop. That was very frightening to us. I had a little girl in the hospital. I put her in there because she was so sick, I had to give her fluids. We were watching her to see what was going to happen and she stopped coughing and I was very frightened. I called Dr. Demario at Duke and he said, "Give her cortisone. We just found out that helps prevent it." The next day she was running down the hall. She had been isolated. She thought she felt so good that she could run down the hall. I just could hardly believe it, but it was because of the cortisone, which is used to prevent encephalitis in measles. There were so many little things like that that came about because I had to have an authority to talk with and I could talk with them at Duke. They put me on with another doctor that knew something about something else. I had sickle cell anemias. Oh, they were pitiful. Sickle cell anemias have so much suffering in the crisis. (13:12, Part 1)

RM: Yes.

MI: They would be a terrific problem. You would transfuse them until you just feel like you couldn't stand it and should you give them any more transfusions. Now, they have a specific thing that will take care of sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia means that the blood cells become sickled instead of other. It's the way they resist infection, but they're not. ..they are weak and in trouble. I would give them the transfusions, but it was very hopeless. We had one or two that would get a stroke. The cells would actually line up at the wrong carcass inside the brain and be a lot of trouble. I could call them about something like that. So far, I don't remember calling them about sickle cell, but I would learn about it when I went up there.

RM: What were the names of the people you would consult with? (14:10, Part 1)

MI: Oh, I talked to Angus McBride and Bill Demaria. They were the chief ones. Bill was a resident the first time I called and we got to be friends because he was just as puzzled as I was. He was a delightful man. We would find out what to do. Doris...what was her last name?

FI: Susan Dees?

MI: Susan Dees, I talked to about allergies a lot. That was a different type...that wasn't a desperate call, but that was what other choices do I have.

FI: I can't remember Doris' last name.

MI: I know.

RM: Well, you had a good relationship going with the physicians at Duke University.

MI: Yeah. I knew them all on the pediatric service.

RM: Chapel Hill had a two-year program.

MI: Yeah. They didn't have a pediatrician that I could count on. So, I didn't really start with them until after our son went there and that was in '68, he was in Chapel Hill. I began to know them well and they were very fine physicians, too, and very helpful. (15:23, Part 1)

RM: Then you felt that...you sort of sided with Chapel Hill, it sounds like for a little bit, that we didn't need a medical school in Eastern North Carolina.

MI: Yeah. I sort of was agreeing with them, but that didn't work out as we proved, because we needed the people. They didn't have the people that could take care of everybody in Eastern North Carolina. I could see that we didn't have the people in a little while, so I began, also, to be mighty thankful for one in Eastern North Carolina.

RM: Do you mean ...when you say we didn't have the people, we didn't have enough physicians or we didn't...

MI: Enough.

RM: Not enough.

MI: Physicians and nurses and other professionals. You see, the physical therapist and the occupational therapist did especially good things that nobody else can do. I have a friend over at the hospital now, she's fifteen. She was in a head-on collision, thrown from the car, and of course, on a breathing machine now for 21 days. She's the longest child I have ever seen that was on a breathing machine for 21 days and she eventually woke up. She didn't know anybody and she couldn't speak. That went on for two weeks and then, she begun to whisper and smile. She begun to hold her mother's hand. (16:55, Part 1)

RM: That's wonderful.

MI: Now, she's talking out loud and I just can't get over it what they have done. It's people like that. See, she used, at the hospital, she used four whole people everyday to take the exercises for the physical therapy and the occupational therapy.

RM: Yes.

MI: And used them three hours in the mornings and three in the afternoon. I didn't have enough faith in those things, becauseI didn't use them.

RM: Well, the people weren't available to you.

MI: That's right.

RM: The support...

MI: I didn't have the people.

RM: ...experts.

MI: Now, I would love to see one in each school. There are children in the schools that need those things.

RM: The physical therapists and the occupational therapists?

MI: Yes.

RM: True. They need special attention. So, you decided that we would need a medical school, but you were always certain that we did need a nursing school, it sounds like. (18:00, Part 1)

FI: Yes.

MI: Yes. We were mighty thankful when it came. He said to me soon after he had been to war, "I think we're going to get a nursing school. It won't be long after that before Leo Jenkins will be asking for a medical school"

FI: That's right.

RM: You did some prophesizing there.

MI: Indeed, Leo Jenkins talked a lot to Fred and enjoyed it. They enjoyed an interesting friendship.

FI: I was a physician, a family doctor as well as...

RM: A university physician.

FI: That's right.

MI: We would talk about those things.

FI: I remember when his celebration when he was made the--not Chancellor, but the President, wasn't it?

MI: Yeah. It was the celebration when he was made President.

FI: President. He named some people. He named me and he said, "I am personally and professionally indebted." (19:11, Part 1)

RM: That's wonderful. He relied on your knowledge and your friendship in many ways. Well, did you have with your experience with the community around you, did you have recommendations with regard to who should run that new nursing school?

FI: I don't know of any...

RM: Who was the first Dean of that nursing school? Was it even a dean? How did they do that, a Chair or a Dean?

MI: It was a dean and her name was Pearl. I can't think of her last name. We got her by calling the nursing office and she gave me several names to interview.

RM: Was this the State Nursing Office?

MI: The nursing office in Raleigh. We went up there and talked with her and we talked with the people. We went recommended her. Jenkins wasn't so crazy about her, but she did a good job, being that she was a trustworthy person. (20:19, Part 1)

RM: Where did she come from?

FI: I don't know.

RM: But, she had been a nurse educator.

MI: Yeah. She had a Ph.D. in Nursing Education.

RM: I see.

MI: I thought that she was a very good person. I don't know what it was that Leo didn't like about her, but he told me when he was getting another one and that he was glad.

FI: Yeah.

RM: What kinds of things was she responsible for? Did she then recruit. ..

MI: Oh, she was Head of the Nursing School. She was responsible for hiring and firing all of the teachers and professors and she was helping to place them. She did some lectures in relation to nursing ethics. But, she didn't do much teaching of her own. Of course, she had an office in the nursing building. (21:24, Part 1)

RM: So, how long would you say it was...the new hospital opened up and pretty soon...well...? How long would it have been before you had staff from ECU? You had nurse interns coming along fairly soon.

MI: I don't know what year they first accepted nurses, but she worked with them on the application blanks. They really had a very good class. They had a set of twins. That was right interesting to me.

RM: Surely.

MI: I didn't have any contact with the Nursing School, hardly. I gave a lecture once or twice like I did in the medical school when they asked me to.

RM: Dr. Fred, you probably saw those nursing students in the infirmary. (22:28, Part 1)

FI: Yes, I did. Quite a few of them.

RM: Were they particularly curious about what the trouble was when they came to see you?

FI: They were more inclined to be curious about the diseases than the other students that came in. They did not come unless they really thought there was something wrong. They were not malingering. They didn't come to get an excuse to get out of class.

RM: So, you had some serious medicine to practice when they would come, the nursing students?

FI: That's right. When they came, we had to be sure that we gave them the right advice and recommendation and so forth.

RM: Surely. Did they ever rotate through as part of their training through the infirmary? (23:26, Part 1)

FI: I'm trying to remember. I believe...

MI: I don't believe you had any to rotate through there.

FI: I don't believe we did either to te11 you the truth.

MI: I never knew any to rotate in there.

RM: Well, you had a clinic off campus and then at some point while you were supervising health care over there, you developed a clinic on campus.

FI: That's right. Yes, that's true.

RM: Did that make it more convenient?

FI: Well, I was in private practice and associated with the Medical Arts Clinic and then when I got out of private practice, I was entirely the medical at the infirmary at East Carolina. Isn't that correct, honey?

MI: The first part.

FI: I didn't do any more private practice after I went over there full-time. (24:43, Part 1)

RM: Did the infirmary...

MI: You went full-time in the end of '60, wasn't it?

FI: Let's see. It was about, I believe somewhere along about that time.

MI: See '64, I went into the Developmental Clinic and before that.... '60, we were riding together at the other place. We had the new clinic building in about five years. We dedicated it in '72.

RM: Did the infirmary need a new building on campus or was there an existing building?

FI: Well, we had one that had been there for some years and while I was there, it was enlarged to take care of the need. I understand that since I left, I believe it has been enlarged since then.

MI: Yes, but they don't have a difference in beds, do they? They've changed... not "put this bed, the bed over there or what." (26:04, Part 1)

FI: Well that's true. When I first went we had more people in the infirmary.

RM: To keep them overnight when they were...

MI: Yeah, to see what developed.

FI: That's correct and sometimes we'd keep them until they got over whatever ailments they had. If it was serious, we would transfer them to their doctor at home or some other area.

RM: Can you think of what was the sickest case you had in the infirmary? Was there epidemics on campus?

FI: Well of course, one of the problems we were always concerned about was sexually transmitted diseases and...

RM: Let's pause just for a moment.

[Phone rings]

RM: Alright, Dr. Irons, you were telling us about the problems you had with sexually transmitted diseases...

FI: Yes.

RM: ...in the students.

FI: That was one of things that concerned us all and of course, anything contagious, we had to be very careful about that. I do remember one of our staff had a patient that had been exposed to rabies. (27:31, Part 1)

RM: Oh dear.

FI: The student had picked up a wild animal and twirled it and it scratched his hand.

So, we could not prove that he was not affected with rabies. So, we called the State Department of Health and they said, "Well, the only safe thing to do is to go ahead and begin the rabies treatment." So, we did and...

MI: How about that man that had the ruptured spleen?

FI: We had another interesting case. One of the athletes had mononucleosis and that's a disease in which the spleen is frequently enlarged. I examined him before he went home for a holiday and told him that he should not engage in any strenuous sports because his spleen was still tender. The poor fellow did not pay any attention to that. I shouldn't say that. When he went home, he did get into some difficulty and his spleen ruptured, but he knew what it was, so he told the doctor. (28:56, Part 1)

MI: He told the doctor that his spleen was ruptured.

FI: They operated on him and he came through alright, but that was a close call.

RM: Yes. A ruptured spleen is nothing to monkey with.

FI: No. It certainly isn't.

MI: He had right much mononucleosis. That's the age group that it gets, so we began to keep reading on mononucleosis.

RM: What did you learn about it at the time? What was the treatment for it?

MI: Well, the treatment was in six weeks you'll be well.

RM: Bed rest?

MI: Yes and bed rest, but it was not a happy thing to treat because they felt so bad.

RM: Did students have to take a semester over frequently because of that or...?

MI: Fred. (29:43, Part 1)

FI: Well, no. Occasionally, they did because they were so sick for so long, but most of the time, they bravely carried on with their class work and could not carry on with their physical activity like they wanted to.

RM: They had to slow down a bit.

FI: That's right.

RM: When you had a serious case of mononucleosis or complications from that, did you keep them in the infirmary or send them home?

FI: Well, some of those we did send to their family doctor.

RM: Did you deal with athletic injuries?

FI: Oh, yes.

MI: He had to go to the football games.

RM: Did you?

FI: Oh, yes.

MI: He went to the football game every time and went to the basketball games when he could.

FI: Yeah, I sat on the bench with ( ) and...

MI: Bless his heart, he was a dear person.

FI: He and I were the same age. We lived right across the street from him. Another interesting case, when they first started having other doctors come in and help us, we had some routine things and maybe we won't have anything in particular, but you always have to be careful. One of the first things this fellow had when a student came in was a spider bite. (31:17, Part 1)

MI: Oh, my gracious.

RM: A black widow.

FI: Yeah. The student then gave a history of exposure. His abdomen was very tender and very painful. Of course, there is a specific treatment for a spider bite that you can use and help them to relax. We always had to be aware of anything that could possibly happen there. Another thing that concerned me a little was one time, one of the ladies in the class came in and had kept it from her family that she was going to have a baby. I examined her and I said, "Now, it looks to me like this baby is about to arrive." So, she happened to live not too far away, not in Greenville, though. We got somebody to take her to the hospital I think it was in Belhaven, probably. (32:45, Part 1)

RM: You wanted to get her home, it sounds like.

FI: I sure did. She had been seeing a doctor there, apparently. But I told her, "I think you can get home." Praise the Lord she did.

RM: She made it.

FI: Everything came out alright, including the baby.

RM: Gracious.

MI: That was unusual.

FI: That didn't happen very often. All sorts of things happened. I was over there for 33 years.

RM: Do you remember counseling young people about sexual activity?

FI: Oh, yes, indeed I do. I think somebody is knocking on the door, but just let them knock.

RM: Well, Dr. Fred, we were talking about the counseling on sexual behavior that you gave to the students at ECU...

FI: We had a very excellent area of assistance in that. One that was so very, very helpful was the lady from Hawaii. (33:51, Part 1)

RM: Dr. ( ) Ryan.

MI: Yeah.

FI: Dr. ( ) Ryan.

MI: And she seemed to say it without embarrassing them, you know, to get the information. She's a delightful person.

RM: She's one of my neighbors.

MI: Oh, good.

FI: You've got some good neighbors, haven't you?

RM: I sure do. I surely do.

FI: Did you say you were ( )?

MI: Wonderful.

RM: You were saying that you missed having a neonatologist when you were practicing, Dr. Irons.

MI: That's right. I would send. I never used the incubator to send away because I kept them and watched them. Some of them lived and some didn't, but they did need a neonatologist because there were times when I could have sent them off and they would have lived. You always hate to see that.

RM: Yeah. It's hard to know what to do with those little babies. (34:50, Part 1)

MI: I had one born with staphyorious infection. It was terrible. I had to get it out of the hospital because it was going to reach everybody, but the mother was one of these people who had never been careful about anything. The baby lived for about eight weeks, but I gave it all of the antibiotics he could have. I felt like that it wasn't going to be a normal baby and in a way, you feel like, well, the Lord knows best. But, I surely did hate to lose that little fellow.

RM: Well, there are times when you have to tum it over to the Lord.

MI: You just do. If you practice medicine, you have to tum a lot over.

RM: That's right. Did you have to end up keeping the baby the whole eight weeks there?

MI: No, no. We explained...that was CB Ward...that we could not keep him there because it could infect the whole nursery and so, we let the mother take him home. The baby was seven or eight pound baby. It was a big baby, but it was born with these sores. (36:05, Part 1)

RM: It was so ill. What was the infection that it had?

MI: Staphyorious. That's the one that causes boils, mostly. It was just awful and it was a resistant one, too. It was resistant to penicillin and erythromycin. One would heal, but another one would break out.

RM: Goodness.

MI: It was terrible.

RM: Yeah. When you had that patient, were you still culturing own?

MI: No, but I was mighty careful even handling it...have the sterile gloves and the sterile covering and the nurses did, too.

RM: And you had a lab to send it to. Was that here in town or did it go somewhere else?

MI: Oh, I had a lab that could do staphylococcus, the commonest bacteria there is. I reckon, because it's found everywhere and is found on our hands at times.

RM: It's just not normal to have a newborn so infected with it. (37:10, Part 1)

MI: That's right to have one born with it.

RM: Where was the lab? Was it there at the hospital?

MI: Oh, yes. We had a good lab. Well, it wasn't anything like the labs I had in Richmond, in which they would try the antibiotic on the growing bacteria, which is what tells you something. But, they were where they could culture it and if you had to, you could do it yourself...try other drugs and you did. I used Coly-Mycin and several that wouldn't respond it anything else, but Coly-Mycin was the one that affected how ( ) making ( ) with blood and the blood would lose it's ability to regenerate itself.

RM: Goodness. That was a last resort.

MI: Yeah. You had to use that when you knew it could give that change.

RM: Did the laboratory facilities change when you started in the red brick hospital? (38:16, Part 1)

MI: Oh, yes. Everything began to improve, stepped up and stepped up.

RM: Where did you send your lab specimens?

FI: To the same place.

RM: To the hospital lab?

FI: Urn-hum. Occasionally, we would send some to the state lab in Raleigh.

RM: That would take a while to get back.

FI: Oh, yeah.

RM: It would take a while to get there and then another while to get it back. Well, that's all fascinating. You've seen the medicine...well, healthcare develop over your years of being here in Greenville.

FI: Indeed we have. It has been a great experience. Most interesting.

RM: Dr. Fred, what are some of the most significant things you've seen happen while you have been here?

FI: Well, I think the most significant was early in the practice was the response to penicillin. That was really...

MI: That was when we came in the early forties. (39:22, Part 1)

FI: Yeah. That was a very significant change and of course, the most helpful, but it had one draw back that we found out later, that some people were allergic to penicillin. It even could be fatal if it is not handled right. So, penicillin is just like other drugs, you have to extremely careful to know what it can do and what it doesn't do and the complications that might arise.

RM: Did you have to take care of people who had reactions to penicillin?

FI: Yes.

MI: Oh, yes. They weren't comfortable reactions. I tell you that.

RM: What happened? Did the...

MI: They could go into an asthma attack or one that I had went into urticaria and we were very concerned. We, in fact, we began always to test about using penicillin with people. When we used it...if I used it in the office, I would have them wait at least an hour, so I would be sure they would have no reaction. (40:36, Part 1)

RM: How would you administer the penicillin?

MI: Most of the time by hypo and that's faster. You can make good by mouth and that just doesn't give as fast results. The thing that I have noticed in neonatologist work, that those babies not only live, they're taken good care of, but they have normal brains. Premature babies that were coming to us, they had the blindness from the oxygen, which was one thing, but that's that little one working at the hospital in the medical records. She's learned to type medical records, but she's totally blind and that was from oxygen. She was the smallest baby that I had to watch live. She was under two pounds and she's blind because we put that oxygen ( ) and I just hate that so bad, but...

RM: You kept here alive. (41:43, Part 1)

MI: She's married to a preacher. She's very happy and comes over here working everyday. So, I'm real proud of her, but so many changes in the babies have been prevented because they knew what to do. So that is a great thing. Of course, now it costs 7, 8, 9000 sometimes for them to get well, but they get completely well and they are normal children.

RM: That's wonderful to see, isn't it?

MI: It's wonderful.

RM: What are some of the most significant advances you have seen in healthcare in your lifetime of dedication to the field?

MI: Of course, we got our polio immunization. Polio was terrible. I was in three epidemics in Richmond. I had 96 in one and a 100 and some in the other. Every one of them paralyzed and some of them had to stay in a rocking bed in order to breathe, but we don't have them now. We bought three incubators for them, used them with them in there...

RM: For the little babies. (43:20, Part 1)

MI: We had nine in all. We had 10 percent of our children nearly always in incubators. Most of them did very well. We watched and watched. Sometimes we had to feed them, too. Polio has vanished and polio and smallpox and I have seen small pox and I hope I hope I never see again. It is a miserable, miserable thing. It leaves scars.

RM: Tell us about that Dr. Malene. As you said, we don't see smallpox.

MI: We got the immunizations and that's here. There are very few places in the world not immunized. Every now and again, I'll see a publication that smallpox hasn't disappeared from that place, but it is very unusual.

RM: How did it happen that you saw a case of smallpox?

MI: I got an immunization, you know.

FI: How did it happen that you saw a case of smallpox, honey? (44:24, Part 1))

MI: Oh. They brought him in, in Richmond and he was exposed to something they said was breaking out, but it wasn't hard to tell that it was smallpox. Smallpox lesions are very similar to the vaccination. They're just blisters and they're terrible and they are all red around them. He was exposed and the man didn't have many lesions. They say that's the way smallpox did and in some families, it would go through the whole family. I remember they had five lesions and one would be all over, but there is no need for it. People just need to take'the immunization.

RM: This man had somehow missed it, I guess.

MI: That's right.

RM: Did he recover?

MI: Oh, yes. He recovered, but he had a lot of scars. I don't know how bad they were really. One on his face, I thought was going to be mighty bad.

RM: What were his other symptoms?

MI: Oh, he had a high fever. With smallpox, they do like they do with measles. With measles, they run a high fever for four days and then, they break out. With small pox, they had that high fever... (45:42, Part 1)

[Side A Ends]

RM: You said with smallpox, you run the high fever for longer than with the measles.

MI: Yeah. When you treat the disease, they don't respond as well as before the antibiotics, but you treat it with antibiotics now and they do respond.

RM: I see and before the antibiotics....did you see this in Richmond before you had the antibiotics?

MI: No. I didn't have it. I didn't see that there, but I just know that's expected. The antibiotics developed resistance to the ( ) and that's one of the frightful things we have about ...

RM: Surely. Well, the man with smallpox got better, but he didn't have antibiotics or he did.

MI: Oh, he did. He had them.

RM: He did have antibiotics.

MI: Right now, I really don't remember which one. It could have been penicillin because that worked well. Then streptomycin, we used. Chloromycetin, we used for typhoid. Typhoid has almost disappeared. Typhoid was terrible.

RM: It sounds like you really appreciate the advances in disease control that have affected health care. (1:16, Part 2)

MI: Oh, yes. My twin took prevention and got her MA in health prevention, as well as, finishing in medicine. She was always bringing up something real good that had happened with the prevention. She said and I see it ( ) in the papers and everywhere, "Why can't we prevent disease and then go in from the prevention side." Of course, prevention is right.

RM: Yes.

MI: We just need to do some more.

RM: Well, in line with that, Dr. Malene, you mentioned that you taught in the schools. You did some teaching of health education in public schools.

MI: To medical schools and to the nurses in Richmond, I taught a regular course of disease and prevention and care. In the medical school here, I taught in the disabled area of children and what we do for disabled problems. (2:20, part 2)

RM: I see.

MI: See, that's...

RM: And that gave you some respect and they founded the Developmental Evaluation Clinic. Of course, that was before.

MI: Right.

RM: You were already heading that up when you came to teach then at the medical school. I was thinking more in terms of you teaching in the public schools.

MI: Oh, I taught biology and general science.

RM: That was before you got into medical school.

MI: That was before I went to medical school.

RM: But when you were in Greenville, didn't you teach in the public schools special classes?

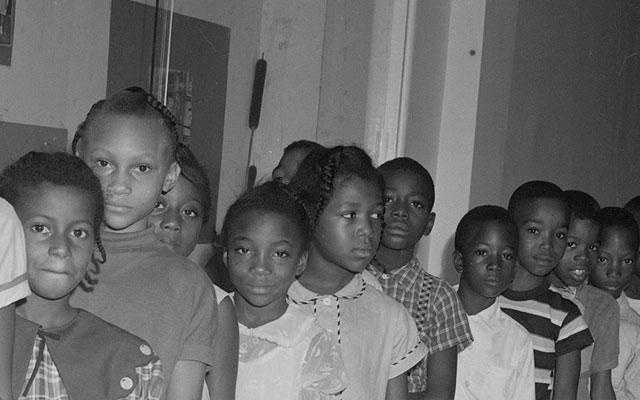

MI: Oh, we taught sexuality.

RM: There you go.

MI: We did that regularly. It was a six or eight-week course. I talked to the girls and Dr. Trevathan or Dr. Best talked to the boys. That just had to be said. I don't know how much it sank it, but we talked. (3:11, Part 2)

RM: Six to eight week courses.

MI: Urn-hum.

RM: Was this integrated into the regular school day?

MI: Oh, yes, in the regular school day. It was in the health education course that they took. The sexuality was part of it.

RM: What grades of students were you working with?

MI: We started with the fifth, sixth, and seventh grades, but we thought we were doing right in the seventh and we decided that was too late. We started going back. Yeah, we did. We started in the fifth several years. I don't remember which years.

RM: Which schools did you go to?

MI: Oh, I went to Wahl-Coates and I went to the middle schools here. Dr. Best went to Grimesland and Epps. They were still separated then. We didn't put them together, but we had them asked questions between in order to see how much it sunk in. They learned the words. His crowd learned the words better than mine did because I didn't use them as much. It would have been better if I had. (4:23, Part 2)

RM: You were trying to be discrete, but get the information across.

MI: That's right.

RM: That's a very tricky thing to do.

Ml: And that's not easy, but we did allow time for questions always and we got some whoopy-dos.

RM: You were surprised, huh?

MI: Yes, indeed. Apparently, in middle school...I went back again to the middle school several times when I was in the Developmental Clinic and they were more sexually active. I could tell by the way they talked, you know. "What can I do to keep from getting pregnant?" "What can I do?" That hadn't been in the idea at all.

RM: What did you tell them?

MI: I told them there were definitely things they could do and they should talk to their doctor and that would be the best, but that there was such things as protection. The boy and the girl could get these. So, I didn't go into details anymore than that. (5:36, Part 2)

RM: Was your aim just to make them aware of where babies come from? When you taught sexuality, how did you ...?

Ml: Oh, we refer...the way I started out always was, "Boys and girls your age, and some fifth graders are, are different. You have hair in the pubic region. You have changes in the shape of your face." I showed them that and showed the changes

in the body. "And the most important thing is this is produced by hormones in your body and your hormones are into them and how they make people feel." You see, they don't know they can't. ..why they feel like they do and we would talk about that quite a bit.

RM: You were preparing them...

MI: Yes.

RM: ...on what was going to come.

MI: That's what we were trying to do. Let's put it that way.

RM: Did you counsel them as to how they should deal with the feelings. (6:37, Part 2)

MI: Oh, yes. I would tell them, for instance, "You handle it the way that will make you feel better. Some people would run around the block and some would take a hot bath and some would do other things. It's a matter of you finding what helps you the most, because everybody is so different." We would always use the uniqueness of a person.

RM: Sure. How did they come to connect that with the sexuality issues though?

MI: Oh, we went right into what the penis and the vagina were and how they were used and that they caused certain thrills in either and both and certain experiences that, I hope they wouldn't know for a long time, but that they are there. That is what people have this longing for and it's great, but you go slowly and discover your way. (7:42, Part 2)

RM: Did you go so far as to counsel them to abstain from sexual activity until they were adults?

MI: Oh, one of them asked me if she should and I said, "It's a real good idea, because it will mean that you will be ready for that man, but there are other things that will affect your behavior and you can't decide on that yet." I believe in abstinence, but I don't think you can tell them that they should be abstinent, but they think you can.

RM: Who thinks they can?

MI: The boys and girls think that. ..some of them, I know one said that she was certainly going to be abstinent, but she was unusual. They didn't say that. They really didn't. They don't intend to. I don't think.

RM: And this was sort of across the board.

MI: Urn-hum. Well, I was with the girls and the boys are even more eager to start something right now. (8:50, Part 2)

RM: I wonder if any of that attitude has changed with the new, heightened awareness of sexually transmitted diseases.

MI: To me, the fact that AIDS is there would make them stop, but that doesn't. They are not afraid of that. They don't think they are going to get it.

RM: Well that's interesting. What was it that motivated you to teach sexuality in the public schools?

MI: The same reason that you would. To see you could help them pick it up right, you know.

RM: Were you concerned about trying to, how should I say, avoid adolescent pregnancies or any of that?

MI: That would be in it. That would be one of the bad things that would happen if they did not use protection, but it was better even to be abstinent than to use protection.

RM: So, you did carry it to its consequences that the end of the sex is reproduction. (9:54, Part 2)

MI: Right. That's what we were trying to do, let them know how dangerous certain behaviors would be.

RM: As far as communicable diseases, but also with regard to reproduction.

MI: Yeah. Oh, yes. We went right into that. Usually, there's one in the room pregnant.

RM: How did you deal with that? Was that person an expert then?

MI: They usually don't know what they were doing.

RM: Is that right?

MI: I don't think they do. I really don't. I think that it is very sad that there are so many.

RM: It is sad, but I'm sure that you made a difference...

MI: I hope so.

RM: ...talking to them and telling them about things that they probably didn't have anybody else to talk to about it. (10:51, Part 2)

MI: One or two have called me and asked questions and that was nice.

RM: Sure.

MI: Then, I had a little group of girls that wanted to know the truth, what really happened. You remember when I went around to Ms. Hendricks?

FI: Urn-hum.

MI: They were truthful, nice girls. They were just trying to find out and I told them the best I could.

RM: Well, I'm sure that helped them a great deal. Well Dr. Fred and Dr. Malene, you carried out long and productive careers in medicine and now you are still very active in the community, I think. Volunteering and helping, I know your church is very important to you.

FI: Yeah. We go down every Thursday afternoon to stuff envelopes.

RM: Stuff envelopes.

FI: What we do is they have....

MI: It's just busy work, but we just want to help them.

RM: Sure. I understand. Throughout your lives, though, you've been involved in different volunteer organizations. (11:57, Part 2)

MI: Yes. We've done...

RM: Do you want to get that microphone off? Can you tell me just a little bit about your involvement in your favorite volunteer organizations and causes?

FI: I think there is opportunity now in Cypress Glen. There is plenty of opportunity to help if we would just do it. As time goes by, it gets a little bit more difficult to deal with those things, but we do have opportunity everyday to help somebody.

RM: To lend a helping hand?

FI: That's right.

RM: Well that's wonderful.

MI: We hope that will get more and more, something that we can do, you know, as we get to know people better. (13:00, Part 2)

RM: And as you get used to being here.

MI: Sure.

FI: That's right.

MI: I do the tutoring at the school and I'm not going but to one student now, because others have dropped out. That's just fine. He's a delightful little boy.

RM: What kind of tutoring do you do?

MI: He had not learned to read, except he learned in two months. As soon as we bought the mothers, and he's doing real well.

RM: Oh, how wonderful.

MI: He's reading now.

RM: You've taught a boy to read.

MI: He was a boy that could, you know, and some couldn't.

RM: How old is he?

MI: He's seven. He did the first grade once, but he's now in the second and he's doing well.

RM: Well you've given him a new life. Thank-you both so much.

FI: You are most welcome. We thank you.

RM: It has been a privilege to talk with you.

FI: You are very kind. We enjoy this relationship very much.

RM: Thanks. (13:59, Part 2)