[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DRS. MALENE AND FRED IRONS January 6,1999

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop

Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn

22 Total Pages

Copyright 1999 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: Okay, it's January 6, 1999.

DM: I know.

RM: We are here on Hickory Street to record the third of our oral history interviews with Dr. Fred and Dr. Malene Irons. May I have your permission to record this interview?

DM: Oh, yes.

DF: Yes, indeed.

RM: I'm so glad. Dr. Fred and Dr. Malene, as I reviewed our previous conversations, there were several subjects that suggested themselves as candidates for expanded discussion of your medical practice in Greenville; I'd like to clarify some of the topics you mentioned that pertained to your youth and medical school days. Will that be all right?

DF: Oh, yes.

RM: Dr. Malene, you mentioned that when you were in eighth grade, in Hertford, you and your sister would sometimes do things that didn't suit your grandmother and your aunt and your uncle.

DM: Right.

RM: I know that these adults who were responsible for you must have had very high standards.

DM: They did and we had too many bosses, too.

RM: Could you tell us a little bit about their attitudes and how that affected the way you were raised and disciplined?

DM: Well, they did their best to help us listen to what they said, and they would lecture us, which was a custom. But they didn't really punish us, but would lecture us and then we were supposed to change our ways. And so we just didn't tell them everything that we did. And we developed a system where we decided, before we got home, what we'd tell them, instead of making it an honest thing of what happened. We didn't get over that for many years. Getting together on it and not telling them the things that we did.

RM: Sure.

DM: That was the ninth grade that we were in Hertford. I don't know why I put it eighth.

RM: The ninth grade, okay. Well, what kinds of things would you do? It couldn't have been so terrible that you didn't want to tell them about it.

DM: Well, we'd walk to school. School was a mile away and then we would visit different people along the way. And we, were always at each other about things. Not really fighting ever, but fussing, but they developed a way in which we were not allowed to go downtown together. One girl would go and then the other one and we took turns when we were allowed to go downtown. We went to the grocery store, we went to the fish market for our aunt, but we we didn't go together. They'd send one of us and we'd never talked back to them. We didn't know how to talk back to people, we just avoided them.

DM: We should have found some way to handle them. But they loved us and they were trying to help us, you know.

RM: Well, you and Isa got over that stage, I guess. You got through that sort of bantering back and forth is probably what you did.

DM: Right, right.

RM: That upset them, I suppose. They felt like you weren't getting along.

DM: And they said that we fussed too much and what we would do was to correct each other.

RM: Ah.

DM: But we got along very well when we went to Wilson. We had another, we went to father and stepmother's residence and they had a dear little sister. We got along better in a way, because we were more together about things. But we kept our business of just not telling them things for a long time and we just didn't report what we did.

RM: Kept your own counsel.

DM: Right.

RM: But I suppose as long as you had somebody to confide in that kept you pretty healthy emotionally.

DM: Sure, we would tell each other things, even in class period or between classes, we'd tell each other things, but the school, in Wilson, was organized beautifully and we had very good teachers. And we worked much harder and we learned a great deal. In fact, that grammar teacher used that in college, it was so good, you know it was just definite good teaching. I don't know which school was the best in the state then, but the teachers that we had in high school there were very good. I was the head of the class and in the first year in college, she, Isa, was the head of class, and went that way on down, and she was head of the class when we finished medical school. I was behind her, in fact, I was considerably behind. I was four or five behind.

RM: Were you also. You also had a companion who demanded some of your time by that point.

DM: Oh, yes.

RM: A mighty fine one. The next of the questions I have goes even further back into your childhood. You had mentioned that there were two physicians, who practiced near Sunbury, while you lived there.

DM: Yeah. And when we were born.

RM: Oh, first there was Dr. Brooks, whose father drove out the carpetbaggers...

DM: That's right.

RM: And then came Dr. Carvell.

DM: That's right.

RM: What do you remember about these two physicians?

DM: Oh, my. I hardly remember Dr. Brooks, cause he died when I was three or four years old, but he was talked about all of the time, and Dr. Carvell was an overweight man and was perspiring heavily. But he diagnosed diseases by the odor in the room. When I had malaria, he came and said "I can smell malaria," and he diagnosed diphtheria that way. And he, of course, had to use antitoxin, and my father was in Hertford at that time, and called up and said give the other girl antitoxin, and Dr. Carvell said well he didn'. think she needed it, and my father said "You give it to Isa.. Well, he gave it.

RM: Did Dr. Carvell have an office?

DM: Yeah, he had an office out in the yard. You know, he had a very interesting companion, he was a black slave from Alabama, who, was going to be shot for something on the farm in Alabama. He got on the train and got as far as Sunbury, and came and talked to Dr. Carvell. They were friends of the people in Alabama. In fact, they were cousins and he asked if he could stay there and Dr. Carvell said, "If you behave yourself.. He did a lot of things, really helpful things, in Dr. Carvell's office, not just cleaning up, but keeping the medicine straight and looking out for people. He was living until we went up there about ten years ago, and he gave us some books that were left in Dr. Carvell's office, that he didn't want to just throw away.

RM: I'm going to look when I go back to the library. I bet some of those came to the library.

DM: I don't think so, I hope they didn't.

RM: You meant to keep those.

DM: Yeah.

RM: Ok. Good. I'll check and see.

DM: But the one that came back that I haven't found and I don't know what I did with it, was Seventy by Seven, which was the a green book, which listed the activities of the Woman's Missionary Society. I just wanted to keep it because it had family names all in it. But, I don't think it was in that group that went there.

RM: I don't remember that.

DM: I think it must have gone to the church, ... but anyway I couldn't find it.

RM: You said Dr. Carvell had an office in the yard, now was it one room?

DM: Two rooms.

RM: How did he have that set up?

DM: Well, people really waited in the yard. He used the two rooms, one was a pharmacy, though, and the other one was plain. Dr. Carvell was married to my grandmother's first cousin, and they had the first bathroom in Sunbury. That created a great deal of interest, and every time we went to their house, as little children, we had to go.

RM: Had to check out the facility.

DM: Checked to see what it looked like.

RM: Yes, oh certainly. Well, he had one room that was a pharmacy in his office, and the other one was a treatment room?

DM: A treatment room, yeah, and it had books and studies in it. I told you that, every time we went for immunizations, like we went for typhoid, my grandmother had lost a little girl with typhoid and she gave us typhoid fever immunization every three years and other things. He would fix the medication and give it to us, and I always shrank back and got on my grandmother's lap and carried on, and my grandmother said she is so nervous, she's like her mother, and I thought that was such a compliment, you know. That's so crazy.

RM: Well, I know she was proud of you, whatever comparison she made.

DM: She was mighty, you know I was thinking she had right much on her, she was fifty-six years old, and she had two babies. She converted the parlor into the baby room, and used it for two to three years, before we moved out of that, and put us in a room.

RM: Did Dr. Carvell come to see you at her house?

DM: Oh, yes. He made house calls and brought the buggy, and Ben was the name of the black man, he always brought things in, and he just waited on Dr. Carvell, but everybody in town thought a lot of Ben.

RM: I'm sure they did.

DM: And he always gave advice, too. He'd tell them what he thought they had. You know.

RM: Oh, that's fun. Well, what kind of a buggy was it, that the doctor came in?

DM: It was just a two-seated buggy.

RM: With a horse?

DM: Oh, yeah, the horse and tied him there in the yard.

RM: So, while you were a child you don't remember the physicians having had an automobile?

DM: They did not when I was a child there. My father had the first automobile that we used much and he was the parson you know, visiting people.

RM: He had a need to move around.

DM: Umhum.

RM: Well, you mentioned that you had malaria and diphtheria. Which did you have first?

DM: Well, I had diphtheria when I was seven, and I had malaria when I was eight or nine, and that worried me because I had a chill in the afternoon and then feel real good the next day and be playing and then I'd have another chill, and...

RM: Was that the diphtheria or...

DM: No, that's, yeah, malaria. The diphtheria, he gave me antitoxin, and he gave me three doses, three different days. The malaria was so miserable though. I remember we'd sit by the fire when I'd get too chilly, things like that. My grandfather, who was Grandfather Costen, lived there did write the Methodist Conference that Sunbury was an unhealthy place and he knew no preacher would want to come. They had so much malaria there.

RM: Oh goodness!

DM: And you see, the Dismal Swamp, wasn't but three miles away, and that was one of the trips we'd like to take because it was so wild and glaring, you know. They had all this jasmine. They had the most jasmine I ever saw together at one place and it's such a sweet perfume, and...

RM: Is that the yellow flower?

DM: Yeah that's a yellow flower with that very sweet perfume that it has.

RM: And did the hummingbirds come to it there as well?

DM: Oh yeah. The hummingbirds love it, and we always got a piece and started it and some of them lived and some didn't, but we had lots of little starts all over the yard. The lady that lived at the house we lived in was my grandmother's brother's wife. She loved the jonquils and daffodils and hyacinths, because you didn't have to do anything to them, and she had the house and yard full of flowers. Of course, what we did was pick'um the first start and put'em on

the graves; never cut a flower for in the house. Except we had the uncle in New York that we sent the daffodils to. You know, we wet them with towels, and put them in boxes and were ripe when they got there.

RM: They made it to New York.

DM: Urn, hum, made it to New York.

RM: That's wonderful.

DM: We had an uncle there. At that time, he was teaching at New York University. He had gotten his Ph.D. at Pennsylvania.

RM: Well, let me ask you, whose graves did you put flowers on?

DM: Our mother's first, but then you see, it was a Costen cemetery and there were all of Grandfather Costen's children, and Costen joined his children, so we always put a few on everybody's grave. Oh, it was a job. We kept them on there, too.

RM: Let me clarify for my own sake here, now the grandmother who brought you up, her married name was...

DM: Isa Costen.

RM: And the Harold's were...?

DM: No, she was married to Harold.

RM: Okay, so her married name was Harold.

DM: Yeah.

RM: And her maiden name was Costen?

DM: Yeah. She was Isa Costen and my twin's name was Isa Costen. When the twins were born, our mother named us and I was Elizabeth McMillian, that was my father's mother, and Isa Costen was her mother.

RM: I see.

DM: Then when she died, they all got together and said one of them had to be named for her, so they chose me. Isa said she was left out.

RM: Oh, I don't think so. I don't think anybody got left out of that.

DM: Not really, they crowded us with love and kindness, they really did.

RM: Well now, nobody these days get diphtheria anymore. Could you tell us about that. What is it like to have diphtheria?

DM: Oh, diphtheria was a dreadful thing. A membrane forms on the back of the throat, and you can hardly breathe. They had antitoxin at that time, and that was 1922. I don't know when they got it in America, but I was really better the next day and, it was a miserable thing. It also had many, very miserable complications. One being heart trouble, following diphtheria. It wasn't the kind of heart trouble that you had with Scarlet Fever, but it was a very serious heart trouble.

RM: And Dr. Fred, you didn't have diphtheria until you were a teacher, as an adult?

DF: That's right.

RM: Was it different as an adult?

DF: I had the same problems, I couldn't swallow, horrible sore throat. .. I was getting antitoxins and had a violent reaction to it, and it swelled up and itching and...

DM: Third carrier, Fred.

DF: Yeah.

RM: So, what happened, did...?

DF: Well, it worked.

RM: The antitoxins worked, but you had the reaction to it as well, I see.

DM: But then later, he was allergic to horse serum. A rat bite in the lab, when we were doing experiments made him have to take horse serum, and that was miserable, but they gave it in very small doses, so that he could take it.

RM: Would it have been for rabies. Why did you have to be treated? Why did they treat you after the rat bite?

DM: That was for tetanus.

RM: For tetanus.

DF: Um,hum.

DM: He was holding my rat.

RM: Oh, gracious. Well, back to malaria then. How did you recover from malaria. You mentioned that you had a reaction to the quinine, didn't you?

DM: Yeah, I broke out. I don't know whether it was due to the quinine, but it was forty-eight hours later, and it wasn't urticaria. It was another rash, but I have never taken any quinine since then, and I don't take it. Why should I take it if it's gonna break me out. It might not have been it.

RM: So how did you get over the malaria?

DM: Oh, it... the quinine did it. I was over it in a week. I was back in school in a week.

RM: You were lucky.

DM: Oh, yes...we had something. We had quinine, which was good, but it wasn't very pleasant.

RM: Did you... you said malaria was epidemic in that area.

DM: It was, you see, it's a swampy area.

RM: What happened to the people. I'm sure many people didn't recover in a week.

DM: Oh, I know it, and they had kept getting quinine, and then they began to use other drugs, which are helpful with malaria, but the quinine... I don't want it used on me.

RM: Sometimes it lingers, doesn't it. It just...

DM: Yeah. Sometimes it doesn't respond to treatment, sometimes it gets to be a malignant malaria, which is a more difficult malaria.

RM: That seems to be under control right now, but might pop up again at any time. Let's see now, Dr. Malene, you finished high school in 1931.

DM: That's right.

RM: And you had planned to attend Trinity College, but do I understand correctly. Was there a change in the university policy?

DM: That wasn't really it, but they did change it the next year. They sent ministers' children free for tuition, but the reason we didn't go was because it cost so much.

RM: Just to live there?

DM: Yeah, and my father checked the schools, and he found East Carolina. I remember it was ninety dollars a semester, I mean a quarter, ninety dollars a quarter, and we paid it. We paid it with our typewriter.

RM: So, you attended East Carolina, and then applied to medical school at Duke, where you were told that your credit for comparative anatomy, physics, and organic chemistry were not accepted.

DM: That's right. They wouldn't accept them from East Carolina. They said they didn't have proper training in those courses.

RM: Did you ever wonder whether your gender had anything to do with that?

DM: You know, we never thought about it. We didn't think so, but I'm sure they were thinking that. Because in our class, at Richmond, there were eight girls and eighty people. Now, they're forty-nine percent girls.

RM: Out of the eighty students in your freshman class, there were only eight women?

DM: That's right.

RM: And you were two of them.

DM: That's right.

RM: Well, when you enrolled at Duke, then, to retake those science courses, you helped support yourselves by typing again.

DM: Yes.

RM: like you'd done through college.

DM: And we did theses. We got into those in the School of Religion. I don't know how we happened to start with them, but we always had one of those MA's going. You know.

RM: Oh, the thesis. The students' theses.

DM: Yeah.

RM: Alright, that's probably what you meant, you had mentioned you'd typed ministerial things.

DM: Well this, no, these were the theses for the School of Religion.

RM: And then, when you reapplied to Duke for medical school, and were denied admission, I guess it didn't occur to you then to wonder about whether it had to do with your being a woman.

DM: No, we didn't worry about that at all, and we were always treated like we were queens at MCV. The men were so nice to us, they called us sister and called us up you know, and studied with us. We never thought about it. I did see, as I told you, some resistance here among the doctors. One never referred a case for three years, but when he did finally refer one, he sent a lot.

RM: You had inspired respect, at that point.

DM: Yeah.

RM: Well, Dr. Fred, you and Dr. Malene served at the Home for Incurables in Richmond while you were in medical school.

DM: Yeah.

RM: What kind of chronic diseases landed folks there?

DM: Everything.

DF: That's about right.

DM: Multiple Sclerosis is one.

DF: Chronic heart...

DM: Lou Gehrig disease was one, arthritis, crippling arthritis, not the old folks' kind.

DF: They were supposedly incurable, but they lived quite a long time.

RM: Were there contagious diseases there as well?

DM: Oh, no.

DF: No.

RM: No contagious diseases. These were people, I guess who were just debilitated and needed special care.

DF: That's right. That's right.

RM: Do you know what has become of that institution since you left?

DF: I don't know, do you?

DM: We don't know, as of the last few years. As of fifteen years ago, they were going strong, and had the one hundred patients that they had before.

DF: Not the same patients.

DM: It was right interesting. Fred was accepted immediately and I wondered why. I found out that the superintendent there was in school with his mother, and knew his name, and was real pleased to accept him.

RM: As a med student?

DM: No, at the Home for the Incurables, for us to live.

RM: To live there, right.

DM: You see, we made rounds every night and gave the medicines for any need, like...

DF: Pain medicine and sometimes they'd have to have laxatives.

DM: Yeah.

DF: And such things as that.

RM: Whatever they needed.

DF: That's right.

DM: Yeah, anything that we figured would help them.

DF: That's right.

RM: You were their special attendants.

DM: And they were very loving people. They were glad to see us, and kind, and nice people. And you know, they were in pairs. I was so surprised. Ms. Warren, the one that was head of the institution said that they sat on the lawn in pairs and the men courted the women, and that it was very interesting.

RM: Do I understand that, in 1941, you were both involved in rotating internship programs? Tape stops here, then starts again. If I remember correctly, you were both involved in rotating internships in Richmond in 1941.

DM: That's right.

DF: That's correct.

RM: December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor Day, is the day about which many Americans have vivid memories. What do you remember about that day?

DM: Well, I tell you, I drew blood and gave it to a boy all day long. He shot himself under his arm and I gave him six transfusions before they got the bleeding to stop, because they had so many things to patch. You know you had to, in those days, you had to type your blood and then type it with his blood, and it took you an hour to get a patient ready for a transfusion, so that was a long day.

RM: Now, which blood did you take...

DM: I was taking the blood from anybody who came in that gave his type.

RM: On that day?

DM: On that day, yes I was. And we gave him six transfusions. I thought surely he was going to die, and I never ate that day, except, you know what I found. The diabetic orange juice was on the

floor. That made me survive. Fred, we kept getting reports, and I'm sure you did too. All day long from what was happening, and they had the radio in the operating room, where they were trying to fix this auxilla. That was a day.

DF: Right that's exactly right.

RM: Where were you, that day, Dr. Fred. Were you in the hospital, too?

DF: Oh, yes.

DM: You were caring for your surgery patients, weren't you?

DF: I think so.

RM: Making rounds?

DF: Um,hum.

RM: Giving a transfusion then, that would have been in the early forties, was so much different.

DM: Oh, yes. Nobody realized what tedium we went through to get that blood right.

RM: Every transfusion, you had to type a different patient, a different donor.

DM: Yeah, you had a different donor and you had to take his blood and then you typed it with the patient's blood.

RM: I guess you drew the blood from one and put it straight into the other one.

DM: Right, you did.

RM: We'd never do it that way now, would we?

DF: No, indeed.

RM: But, I suppose it saved that young man's life.

DM: Well, we probably did. In fact, I know we did. But, they kept saying we were going to lose him. I hated for them to say that in the room where he was.

RM: Do you think he was conscious through the whole procedure?

DM: I don't think he was, but he would go into consciousness and come through. But how in the world that boy got shot in the auxilla.

RM: You think it was an accident.

DM: I think it was.

RM: Guns are frightening.

DM: But, you see there are a lot, there is a plexus of veins in the auxilla, and in the inguinal region, too, and that made it difficult.

RM: Yes, I'm sure. Dr. Malene, you've told me that because you didn't particularly enjoy surgery, Dr. Fred would take your call.

DM: Oh, and he would in the emergency room.

DF: I did, sure did.

RM: You didn't mind the surgery, I guess?

DF: Well, I thought, I didn't mind it as much as I minded trying to take care of babies and things like, because I didn't do that.

RM: You didn't do babies. I wonder if that was related to your skills in the anatomy lab, if you could, you know, manage those kinds of dissection cuts and maneuvers. I suppose the surgery came pretty...

DF: Well, it wasn't a particular problem. I remember one patient . had, that had a cut all the way around the scalp, like that.

RM: Right across the forehead.

DF: Yeah. Well I told the, one of the...

DM: Residents.

DF: ...residents that I didn't think I'd try. "Oh, yes you can, you go ahead and do that.. So, I sewed her all up and she came back, and had a check. She got completely straight. Thank the Lord.

RM: You got the skin put back where it needed to be.

DF: Yeah.

RM: Well that's good! Dr. Malene, what was it about the surgery that you didn't enjoy. Can you say?

DM: Oh, it was just that I had so much to do, and that I liked to do the babies better.

RM: I see.

DM: Let me tell you, an intern in those days, and these days too, didn't work eight hours a day, they went on into twenty-eight.

RM: So, you'd just as soon not to have to be spending time suturing?

DM: That's right. If he was there and did it, and he learned where everything was in the emergency room.

RM: You were a good team. You could trade off that way. Already specializing there, what you liked to do best. Well, when Dr. Fred went to Fort Jackson, in South Carolina...

DM: Yes.

RM: Dr. Malene, you worked with a specialist in OBGYN at that time.

DM: That's right. Her name was Genyard.

RM: Dr. Genyard, and as you know I'm sure, during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, many women physicians found acceptance as medical professionals, by specializing and caring for women.

DM: Yes.

RM: Did you ever think of going that route?

DM: Yes, we talked about it a lot, Isa and I did. We know some women that specially preferred other women. But, the truth was, we loved the babies. So we decided on that, the both of us. We said, our father said one of you ought to be the woman doctor, and the other one a baby doctor, but both of us wanted to be the baby doctor.

RM: Sounds like your dad had it figured out. Didn't he?

DM: Yeah.

RM: I can imagine it, a huge, a great practice in Richmond there. He was going to have you taking care of the mothers and the babies. Well, how did you decide to return to Richmond then, after Dr. Fred went to the service... went overseas?

DM: Well, you see, when he went overseas, I was already asked to be on the staff in Richmond, and Isa was in Pennsylvania interning, and she agreed to come down. They asked her and we were the two women they had on children's diseases, and we had a very interesting number of patients.

RM: I'll bet you did. According to my notes, there were three hospitals in Richmond that served children. Is that right?

DM: I'm sure there were.

DF: Duley, and Saint Phillips.

RM: Medical College Hospital, Duley, and Saint Phillips.

DM: That's right.

RM: What do you remember about those three?

DM: Well, they were, all had the worst diseases in town, because they were the ones that they treated, and Duley didn't have a lot of patients. I think forty, thirty or forty, I don't remember exactly how many.

RM: Is that a private hospital?

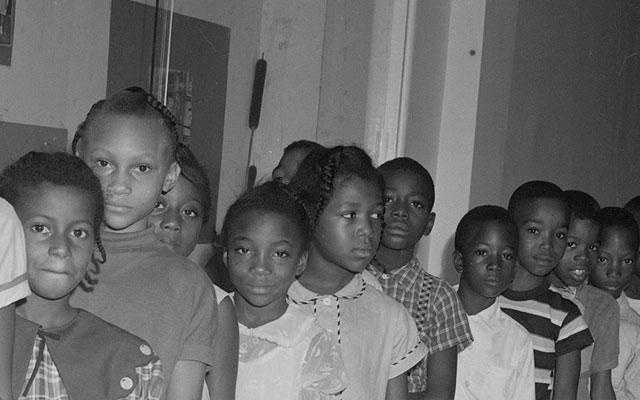

DM: It started as a private children's hospital, and then it became public and was attached to Medical College. Saint Phillips was the black hospital. They didn't let the black babies in with the white babies, going to contaminate them thought, and so we had to make rounds in all three hospitals, everyday and we made...

RM: Was the Medical College the largest of the three?

DM: The Medical College had five hundred beds, but, or more, but the children's beds were on two floors. It had, I think ten or eleven floors. I'm not sure how many floors, but it was a very tall, fine hospital.

RM: You were saying you made rounds everyday. I interrupted you, I'm sorry.

DM: That's right, we made rounds morning and evening everyday. We ended up, though, that she made rounds one time and I made rounds the other, and we kept up with what was going on, you see, and wrote notes to each other so we could follow together, because we had to know what was happening.

RM: That's wonderful that you could work it that way. Can you remember, can you compare the facilities at the three different hospitals at all. Do you remember?

DM: Well, Saint Phillips, they didn't have even basic cleanliness, sometimes. They had a rat in the crib of a baby. They had trouble. We just about hit the ceiling on that, and, but Medical College was beautifully clean and shining, and had all the chrome and stainless steel needed.

RM: Did you have any difficulty finding the medications that you needed?

DM: We never had any trouble with medication, even when penicillin came in. We asked for it and got it. Of course, that was not widely given at right at first. Everybody had to know what it was.

RM: Sure.

DM: But they had the priorities on the medicines, the big hospital in Richmond did.

RM: What about at Duley and Saint Phillips. Did they have any trouble getting medicines?

DM: No, we didn't have any trouble with getting it. You know, we made so many transfers in treatment though. For instance, a child came in with pneumonia. We had to type the type of pneumonia, because certain drugs were specific and it took a long time to type, sometimes all night long, and then give the specific medicine.

RM: How, you did the typing yourself, is that what you're telling me?

DM: Oh, yes, we did the typing and we had sulfanilamide, which was very helpful with pneumonia. There was a big change. We had to use the typing, too. Isa had a very sad story of Daniel Webster... something Samuel Webster Jones that came in and his mother asked to come in the room while Isa was working on him and she said no, you have to stay outside and she worked all night long. She did, get the type though and was able to give it to him, and she opened the door to tell the mother, and the mother was still on her knees at the door praying.

RM: Praying, yeah.

DM: Of course, she thought the prayers did it. I reckon I would, too.

RM: Well now, what does that involve, typing pneumonia?

DM: Well, you see, there are bacteria that cause pneumonia and there are different types that cause it. They are all of those double cocci, and we had to use specific sera, and find out which one would ring.

RM: Nobody does that anymore, Dr. Malene.

DM: Why, heavens no.

RM: You take a sample and send it to the lab, and it comes back from the... So what did you do, you took a sample of sputum?

DM: No, the blood. Oh, we did take sputum, too. We used both cultures.

RM: You took the blood and you cultured it. Right there?

DM: Yes. We took it from the sputum to culture it, too, but that was quite an involved process, but they got well, sometimes.

RM: I want to hear about the involved process, because they don't do it, because you don't do that anymore.

DM: I know it.

RM: So, what did you do, you took the blood serum, and what did you do with it. You drew it out...

DM: We drew it out, we cultured it. If we could get good bacteria; that was great form the culture.

RM: That means, you had to let it grow.

DM: Yeah, you had to let it grow, and then you had to type it specifically, that is, whatever type it was would ring the bacteria when you put it under the microscope.

RM: What would you apply to the growing bacteria?

DM: Specific known types, and then you would get a ring, and then that would tell you what to do.

RM: If it matches. What do you mean by if it rings. There was no sound involved, was there?

DM: No, no sound, but it would ring the bacteria.

RM: Circle around it?

DM: Uh, huh.

RM: A circle would appear.

DM: A circle, uh huh.

RM: Oh, all right. A circle would appear around it then, and then you would know what kind of medication to administer. I think that is very special treatment that is hard to come by these days.

DM: You know, that was all we had then. There were so many people that died of pneumonia, and that doesn't happen anymore. Praise the Lord.

RM: In my experience, one goes in and the physician says you have pneumonia and here's the medicine and take it.

DM: Yeah.

RM: It takes a long time to get over it sometimes, and sometimes you have to try a different kind of antibiotic.

DM: Oh, yes, because the bugs are getting antibiotic resistant.

RM: Resistant, but to have, to actually. I suppose then, if you are sick enough or long enough, they will take the cultures and type them.

DM: I don't know. We stopped typing them about the time we came to Greenville. Fred was getting back from the service and cause we had sulfanilamide then. We had penicillin, shortly thereafter.

RM: So, that was about '45 or '46, when you stopped typing. Was that because the antibiotics were broad enough spectrum that you could just...?

DM: Yes, yes.

RM: Okay that makes sense. That makes sense. Isa came down with tuberculosis, if I'm not mistaken, while Dr. Fred was away.

DM: Yes, she did and she went to the sanitarium in Catawba, which is close to Roanoke, Virginia.

RM: What do you remember about that sanatorium?

DM: Well, they had porches. They thought everyone should sleep on the porch to get well, and she slept on the porch and often there was snow around the bed. She stayed there two years and then she worked there for a little while. Then she went into the Health Department of Richmond and she worked in Richmond a few years, two or three, and then she went to Raleigh, and was head of the Health Department in Raleigh.

RM: Well, tell me back about the tuberculosis treatment, did you visit her very frequently then?

DM: Oh, I had her car. Yes, I went as often as I could. I went every month.

RM: She must have picked it up there at the children's hospital.

DM: No, she had a short practice in Franklin, Virginia. They had no child's doctor in Franklin, and she was very busy and she stayed with a child that had tuberculosis meningitis all one night and that was when she was real tired and knew she was sick, and we proved it from that, and so she came to Richmond to get diagnosed, and stayed in Richmond about two weeks and then I took her to Catawba.

RM: What kind of symptoms was she having?

DM: She had a cough and she was tired, you know, tuberculosis, is an exhausting disease. They feel so tired.

RM: Well, she's lucky that you recognized it right away.

DM: Well, really I think, she was. In fact, we were very thankful that she did.

RM: Was there a medication that went along with the fresh air treatment?

DM: They had no medication then. Now they have streptomycin, which is specific and is good. She had a breakdown of tuberculosis, when she was in Richmond and they gave her streptomycin, and she got well in a few weeks.

RM: Oh, a recurrence.

DM: Um,hum.

RM: That came back again, yeah. I think we're going to have to stop right there today and I'll take up again next time.

DM: Well, we'11 be right here.

RM: Thank you.