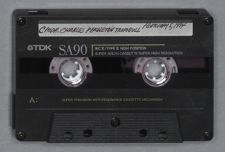

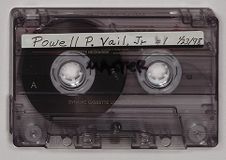

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Commander Charles P. Trumbull | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 5, 1994 | |

| Interview #1 |

Gene Williams:

Generally, what we like to do is to start off with the person being interviewed giving kind of an overview of their career. You can start that, if you would, by backtracking a little bit and talking about your place of birth, where you were educated prior to going to the Academy, and then, from that point on, you can describe your military career. You can feel free to give whatever detail you'd like. I note, for instance, that you were born in Connecticut.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, I was born in Hartford, Connecticut. But at the age of one, my parents moved to Cleveland Heights, Ohio, so I grew up there. I graduated from the Cleveland Heights High School. I had a couple of appointments to the Naval Academy, but none of them were the principal appointments, so I didn't go that year, instead I went to Union College in Schenectady for a year. Then I was successful in getting a principal appointment and entered the Naval Academy in June of 1937, Class of 1941.

Gene Williams:

I noticed that your first assignment was to the USS LOUISVILLE.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes. Upon graduation, I was assigned to the LOUISVILLE, a heavy cruiser. I joined her in Long Beach and we sailed for the ship's home port of Pearl Harbor, where we operated out of continuously until the war. However, in October, the LOUISVILLE escorted a couple of president liners to Manila--taking out the Texas National Guard--and we left Manila at the end of November, went to Borneo to refuel, and were in the Coral Sea on the way back to Pearl when the war started. So, we arrived at Pearl on the sixteenth and saw all that devastation that we had no clue about. We then escorted Marines down to Samoa, joined the Carrier Task Force in the Coral Sea, and stayed pretty much in the Coral Sea area until shortly before the battle, when the LOUISVILLE was sent to Mare Island for overhaul. They tried to rush us through overhaul to get us ready for the Battle of Midway, which, in spite of all the secrecy, we knew all about. They didn't get us out in time, so we went up to the Aleutian Islands, patrolled up there in the fog and bombarded Kiska. On the LOUISVILLE, I was in the anti-aircraft battery, fifth division officer, until the middle of 1942 when I became the third turret officer. I then got orders to submarine school. I was detached to Kodiak to await transportation to New London where I entered the submarine school class the beginning of September 1942.

I graduated in December and was sent to Brisbane, Australia, to wait assignment to a submarine. I eventually was assigned to the USS GROWLER, which had just returned from her fourth patrol, in which Captain Howard Gilmore had been killed when she rammed a Japanese gun-boat. It was several months before they got the ship ready to go to

sea again. We operated out of Brisbane for about three patrols. We went back to Hunters Point for an overhaul and then came back and operated out of Pearl Harbor for two more patrols. So the GROWLER went out for a total of five patrols, three of which were deemed successful. We torpedoed, I guess, seven Japanese ships and sank one by gunfire. We went on further patrols and at the end of the ninth, I was transferred back to New London, to put the new submarine, CABEZON, into commission as executive officer. The CABEZON only made one war patrol. That was in the Sea of Okhotsk, where we sank one ship. Then we went to Saipan for refit and while there, the war ended.

There were about a dozen submarines there at the time and eventually they all got assigned new home ports and cities to visit on the way back, except for the CABEZON. We were ordered to Subic Bay, much to the discouragement of everybody involved. It took a long time to persuade the skipper, George Lautrup, that these were not fake orders; we were really going to Subic Bay. So, we ended up there for five months. We really had a good time. We toured a lot of the Philippines by jeep and by circumnavigating the islands. At the end of January, we returned to the States to San Diego, for three months and then went to our new home port, Pearl Harbor.

Gene Williams:

That was in January of 1946?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, January 1946. Then at the end of December 1946, we made, what they called then, a simulated war patrol--something devised to keep submarines busy. We took a cruise down to Samoa, a Polynesian island called Kapingamarangi. It's in Micronesia, although

the natives are Polynesians. We also went to Truk, Guam, Okinawa, and Japan. In each of those main ports we would work with the destroyers, serving as targets.

In April 1947, I was transferred from the CABEZON to go to the Navy Intelligence School in Anacostia.. I guess that was about a year-and-a-half course. I was then assigned to the Panama Canal Zone as assistant district intelligence officer. It was a very interesting tour. I had to travel all over Panama making surveys of possible landing beach sites. Also, my wife and I made, on our own, a tour up through the Darién jungles, visiting the Darién Indians--took a dugout canoe and slept in little Indian villages--so we got a real feel for the country.

From Panama, I was transferred back to submarines as exec of the USS TUSK, operating out of New London with the Submarine Development Group 2. Then in April of 1951, I took command of the submarine CHIVO, which was in the Electric Boat Company being turned into a high speed Guppy. We were home ported in Key West. We stayed for two years, making one cruise to the Mediterranean and visiting a great many ports in the Caribbean: Guantanamo Bay; and Puerto Prince, Haiti; Port Antonio, Jamaica; Santiago, Cuba. While the CHIVO was in an overhaul in Philadelphia in 1953, I was given orders to go to Hong Kong as U.S. Naval Attaché. My official title was Assistant U.S. Naval Attaché and Assistant U.S. Naval Attaché for Air London, Resident Hong Kong. I spent almost three years in a fascinating tour of duty--Hong Kong then being the chink in the Bamboo Curtain--it was an ideal intelligence job. Plus, I was practically submerged with visiting admirals, generals, secretaries of the Navy, and so forth to take care of. Hong Kong in those

days was nothing like it is now. We only had one good hotel, no subways, and no under-harbor tunnel. Everybody had lots of servants and the social life was exhausting, but that duty was, I want to say, almost a thrilling experience.

While there, I made a couple of trips down through Southeast Asia and the Philippines. Once I went to Singapore in a conference of all the Southeast Asian, British, French and American attachés and once on a sightseeing trip to Vietnam, Saigon, and up to Cambodia to visit the old ruins of Angkor Wat. I was eventually transferred from Hong Kong to the hydrographic office in Suitland, Maryland, a job which required a submarine officer. I wasn't very happy about this, since it would mean I would have had five years of shore duty; but I was assured by the Navy at that time that after foreign shore duty, one had to accept home shore duty. I was sure that would lead to my being passed over, which it did. When I got free from the hydrographic office, the detail officer very much attempted to get me a float job, but none of the flag officers involved would accept a commander who had five years of shore duty, so they gave me a very delightful job as executive officer of the Navy station in Bermuda, which of course, was very enjoyable. I was there almost two-and-a-half years in that job when I retired.

After my retirement I was given a position with Columbia University Oceanographic Research Station operated by Columbia's Lamont Doherty Geophysical Observatory. We were known locally as the Sofar Station. I had the job of administrative manager and marine superintendent. We had an ocean-going ship and an in-shore ship, a cable-laying barge, and a utility boat. Most everybody there was traveling all the time

because although we were stationed in Bermuda, our work was all over the world. I was hired to be the one guy to stay home and keep track of everything that was going on, but it was only a matter of months before I was in the travel circuit, too. We went to the West Indies once a month for two years; an average of about ten days a month. We were engaged in low-frequency underwater sound transmission and we were mainly engaged in trying to determine the speed of sound through what is known as the Sofar Channel, a channel deep in the ocean varying between twenty-five hundred and four thousand feet, in which the sound is not attenuated; it keeps traveling and would go all around the world unless it hits something. In fact, at one time, we dropped bombs south of Australia and listened to them in Bermuda and in the SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System) stations along the East Coast. We conducted those tests mostly by dropping explosives in the hydrophone network down off Antigua, so that's the main reason we went to the Caribbean so often. We were really a captive laboratory of the Navy. All of our funding came through the Office of Naval Research. Our main project shortly became that of scoring for the Navy the missile impacts. When they'd fire the Polaris missiles and later the Poseidon missiles from Cape Canaveral or from a submarine, we would be the ones who would tell the Navy where these missiles hit by using these underwater sound techniques. That occupied the main part of our time for many years.

In 1963, I made a trip to the Canary Islands to make a feasibility study for putting up a hydrophone station there to complement the various SOSUS stations on the East Coast and through the Caribbean. We needed to have something to the east of the missile shoot so

we would get better crosscuts on the locations. We set up a station in the Canary Islands and it was actually through this station that we located the sunken SCORPION. We never got credit for it, however, because our mission on the Canary Islands was confidential. But we heard fourteen loud implosions as the SCORPION sank. By going back through records of other SOSUS stations, we found one other station that recorded very slight indications, and through that they were able to pinpoint and then locate the SCORPION.

Gene Williams:

What year did the SCORPION go down?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Somewhere in the late 1960s.

Gene Williams:

It was after the THRESHER had been lost.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Oh yes--certainly it was after the THRESHER.

We did a lot of work out on the Pacific Ocean. I had one trip with one of our technicians and my wife, who was also an employee of the station, to Samoa. We stayed for ten weeks to record the missile impacts fired from the west coast into the Kwajalein target area. Also, I was making a survey of Samoa for a possible location of another hydrophone station, but that never materialized.

I had a long trip out to the Far East to Manila, Okinawa, Japan, Philippines, and Hong Kong on one of our other projects. I think that during my fifteen years with that Sofar station in Bermuda, I traveled more than I did for the U.S. Navy.

I'm going to backtrack to the late sixties. When Columbia University had that student uprising--I think in 1966--one of their main demands was that Columbia University give up all classified research. Finally, the University caved into them. Lamont Geological

Observatory was doing just a little classified research so they were able to give that up. But all of our research was classified, so we had to disassociate ourselves from the university. We formed a private corporation called Palisades Geophysical Institute with our president as Maurice Ewing, who was the director of Lamont. Maurice Ewing was probably the most famous geophysicist of the time. He's the one who really began extensive plotting of the sea floor and came up with the theory of sea floor spreading, and although he never quite embraced the theory of plate tectonics, it was his work that led directly to that discovery. So, we set up our new headquarters in Nyack, New York, and that took over a great deal of my job as the administrator. Due to cutbacks in funding, we lost our ships, and that pretty much led to my not having a job to do there.

In 1977, I took a job with the Bermuda Biological Station for Research as the technical manager. I stayed there for a year-and-a-half and then in 1979, we decided it was time to come to back to the States. My wife and I had a daughter who was ready to enter high school, so we moved to Chapel Hill. My son by a previous marriage was at Chapel Hill working on his PhD in economics. When he was at the University of Miami, I had bought a house for him to live in and he would rent out rooms to two other men. It turned out to be a really good investment because all I had to do was pay the mortgage, and I didn't have to pay him anything to stay in college. When he moved to Chapel Hill, we tried that again. So when we decided to come back home, we had this nice house just outside of Chapel Hill, and fortunately, evicted my son and his new bride and moved in. He and his wife were able to find a house just up the street from us, so we had a good time. Jane, my

wife, went on to get her master's degree in Library Science. My daughter eventually graduated from Chapel Hill high school and in due course graduated from the University of North Carolina there.

I began taking courses at the University, primarily in Chinese subjects: Chinese history, Chinese Communist Revolution, Chinese Geopolitics, Chinese Poetry, and the language itself. The reason I did this was I had had in mind for some time writing a book on the subject, which I have done. The book, "Four Thousand Years of Chinese," covers the language: its history, its songs, its Romanization, its dialects, its written classical form, its spoken form, and its characters; then some folk cultural things such as the Chinese calendar, the Chinese festivals, and the Chinese cosmological theories; a chapter on the use of Chinese language by the Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese; and a chapter on the future reforms of the language. I worked on this book for about ten years; had a lot of good comments on it, but I never could actually get a publisher. I did publish twenty-five of the books myself because I had an offer from the Asian Foundation in San Francisco to have this book catalogued and in their library, and they would in turn give me a list of other foundations and libraries that they thought would like to have it. I'm in the process of doing that now, but in that process, I have found a couple more publishers who might be interested in it.

Also, since I've been back, I've been very active in the Republican Party. I have been on its Executive Board almost since I came to Chapel Hill until now, and I was chairman of the Orange County Republican Party for two years, 1989 to 1991.

In 1988, we bought one of the historic homes in Hillsborough, North Carolina. Hillsborough is an old pre-Revolutionary town and was at the time the most important city in North Carolina away from the Coast. It served for awhile as the capitol, and the British royal governors of North Carolina always came to Hillsborough for the summertime. So, it's a really old and a really interesting town. We spent three years restoring this old house, and it's been on the Christmas Candlelight Tour and the April Garden Tour several times because of the interest in it.

Gene Williams:

Is it on the National Register?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes.

Gene Williams:

Whose house was it? What's its name?

Charles P. Trumbull:

It's called the Berry Brick House. It was built by John Berry for his widowed mother. The plaque on the house says 1805, but John Berry was only seven years old then, so we think it was more like 1814 or 1815. It was built with him serving as apprentice to the master mason, Hancock. John Berry went on to become North Carolina's foremost architect and builder of brick buildings. He built several college buildings including the Playmakers Theater at UNC. He built many buildings in Hillsborough, several courthouses around the state, and other University buildings; so he came to be quite a famous guy. But this old house--it's a small house, only 1,600 square feet--is a very charming house and we like it.

Also, I've been active in the Navy League; it's called the North Carolina Triangle Council of the Navy League, which encompasses the cities of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. Just this last month, I was elected the president of the League for this coming year.

Gene Williams:

I wanted to ask you one question about your interest in Chinese culture. Prior to your assignment in Hong Kong, was that something that you were interested in previously from studies, or did it really get cultivated in Hong Kong?

Charles P. Trumbull:

No, it got cultivated in Hong Kong.

Gene Williams:

Did you actually do any teaching at Chapel Hill?

Charles P. Trumbull:

No.

Gene Williams:

I guess I'd like to go back and reflect on your wartime experiences a little bit. You certainly have had an interesting career and I guess at some point, it's probably a toss-up as to what was the more fascinating; trying to get through the war and operate on a submarine and survive, or trying to take this oceanographic outfit and do your job and do it well. Did you mention that you retired from the Navy in June of 1961?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes.

Gene Williams:

As you reflect back on your time in the Navy; both wartime and peacetime, post-World War II, is there anything that you can reflect on in the way of changes that you think may have had a profound effect on our Navy today, that maybe you saw coming and tried to do something about, or, do you have any commentary?

Charles P. Trumbull:

I don't think so. Of course, the great future of the submarine force lay in the nuclear submarines and I had no idea that that's where they would go; and I never was in the nuclear program.

Gene Williams:

OK. You mentioned at the end of the war you and your shipmates were ready to go back stateside. I know there was a mad scramble--as a matter of fact, there was almost a mutiny by the armed forces as to who was going to get back stateside first--and you said you had to go to Subic Bay. However, you made it sound like you and the crew took a possibly negative situation and really benefited from your time to get out and explore the islands.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, we had a lot of submarine operations, so we weren't just sitting in the harbor. In fact, we all went off as a task force down to the South China Sea to a deserted island, which had been fortified by the Japanese, and then turned around and came back, just as something to do.

Gene Williams:

How well was the United States Navy received in this area of the world after the war? How were you viewed by the people that you encountered, the cultures? Were you welcomed pretty much, with open arms?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Oh yes, because we were in the Philippines and we, of course, about a year before, had liberated the Philippines, so we were very well thought of down there.

Gene Williams:

That whole situation has since turned around in the last few years.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Oh my yes, very much so.

Gene Williams:

What the volcano didn't do, the pressure from the congressional budget-cutters finished off. When you were at the Naval Academy, for want of a better word, what was your major course of study? I noticed that you're very heavy into oceanography.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Well, we all took the same courses at the Naval Academy in those days. We didn't have any choices. It was the liberal arts sort of thing such as English and History, and then we had naval things like Naval History, Navigation, Seamanship.

Gene Williams:

You held a variety of positions utilizing your education. Was the purpose of the Naval Academy program back then, as it is today, to turn out the most well rounded seaman, sailor, officer that one could?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes. The only choice we had in subjects was a language; a choice of one of four languages. Of course now, you can major in any number of subjects, many which don't appear to have much to do with the Navy. But, that's the way things are these days.

Gene Williams:

Going back to your initial year of college in Schenectady, New York. Had it been a long-standing dream of yours to go to the Naval Academy?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes. I had wanted to go to the Naval Academy and get into submarines since, I think, I was about twelve years old.

Gene Williams:

Is there one thing you can remember that grabbed your interest and from that day forward you said, “Yes, this is something I want to do,” and can you clearly remember the link?

Charles P. Trumbull:

No, I don't know that I remember any one initiating incident. Naturally, I saw the Dick Powell movies, "Annapolis," and this sort of thing.

Gene Williams:

I have heard that mentioned before by some of the other fellows, Dick Powell, Ruby Keeler...... The Blue and Gold.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Ruby Keeler. Yes. There were several of those, but I was interested in it even before then. My father tried to talk my older brother into going to West Point; and he would have nothing to do with it. When I finally announced, "Hey, I'd like to go to the Naval Academy," my father bent over backwards to get me in.

Gene Williams:

Do you come from a large family in Connecticut?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Well, Trumbull is an old Connecticut name. Actually, there were two separate Trumbull families. My predecessor, John Trumbull, came over in 1636. He was a ship's master and he continued to sail out of Massachusetts, where they first settled, down to the West Indies. The more famous family's predecessor came over three years later in 1669 and he was a cooper. His family produced the famous Jonathan Trumbull, who was not only a British-appointed governor of the colony of Connecticut, but was also the first elected governor of Connecticut. He was the only one to serve both as a royal governor and as an elected governor. He was a personal friend of George Washington, who always referred to him as “Brother Jonathan.” One of his sons followed him as governor and one of his grandsons also became governor. His son who was the governor also served as the second Speaker of the House of Representatives in Washington. That family established itself in Lebanon, Connecticut. My family established itself in Norwich, Connecticut, where another John Trumbull published the local newspaper, The Norwich Packet. Eventually, one of the sons came down to Stonington, Connecticut, and brought his two

brothers down with him, one of whom was my great-great-grandfather. Stonington, Connecticut, became one of the major whaling and sealing ports. My great-great-grandfather owned ten whaling ships, built four beautiful homes in Stonington, as well as a big factory there, so he was sort of the big entrepreneur in Stonington. My great-grandfather, my grandfather, and my father were born in Stonington; unfortunately, I was born in Hartford.

Gene Williams:

Did any of your ancestors have naval careers?

Charles P. Trumbull:

No.

Gene Williams:

So, you were obviously the first at the Naval Academy.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes.

Gene Williams:

But I can see that you had the sea in your blood.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Oh, yes, very much so.

Gene Williams:

I guess it bubbled up and you were the one who was annointed.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes. We used to go back to Stonington when I was a boy, every summer, and stay with a great aunt who was living there. We'd do a little sailing and I really thought the ocean was a great place.

Gene Williams:

Obviously. You've spent a lot of your life in the water. I don't know if anyone has discussed with you the project to collect the papers of the Class of 1941, but several of your classmates have deposited papers from their military careers, and that may be something that you might want to consider at some point.

Charles P. Trumbull:

I don't think you want my file of orders from one place to another. I think you're talking more about diaries and notes and articles.

Gene Williams:

That would be the primary interest. Are there any other things that stand out in your mind as you reflect back on your naval experience?

Charles P. Trumbull:

I go to a great many of the reunions, and, for a while, I was going to a great many of them on the West Coast because my plebe summer roommate, Archie Kelley, lives in Coronado. He has a forty-five-foot sloop and, we used to sail down to Cabo San Lucas in Mexico, which is a trip of about eight days down and sixteen days back. I did that three times with him. A year or two after that first trip, my wife and I bought a time-share condo there in Cabo San Lucas, so we go down there every year; in fact I'll be going down there two weeks from now. It used to be a little fishing port, with a little cannery. About twenty years ago, the sports fishermen found it, because it's about the finest marlin hunting grounds in the world. About five years after that, the yachtsmen found it, and then, unfortunately, about five to ten years after that, the tourists found it; so the high-rise hotels are going up and the t-shirt stores, and the real estate offices are booming and they've even gone so far as to start paving the streets. But it's still a delightful place--you're in the desert and you're right on the water.

Gene Williams:

It's kind of the ultimate paradox to see the two things there; the two extremes.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Exactly.

Gene Williams:

Well, good. I don't know that there is anything else specifically I want to ask you.

Charles P. Trumbull:

We still do a lot of traveling. A Chinese guy in Hong Kong who worked for me is one of my agents. After I left, through some real estate deals he was in, he became a multi-millionaire. He got out of Hong Kong and took his money to Switzerland and to Toronto. I've been over a couple of times to visit him in Zurich and three or four times up in Toronto where he lives in a penthouse overlooking the lake. So, besides traveling to Mexico every year, my wife and I have made a couple of trips to Europe. A year ago we spent a week in Paris, and this past year we flew non-stop to Paris for a night to get rid of the jetlag and then onto Bologna, Italy, where I have a cousin who has lived there for thirty-five years. We spent four days in Venice and then went up to Zurich to visit my Chinese friend. We've made trips to the Caribbean a couple times; I have a friend in Antigua. Of course, we went to Hawaii for our class reunion.

Gene Williams:

It sounds like you stay busy.

Charles P. Trumbull:

While we were stationed in Bermuda, we made a trip across the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Two years before that, my wife and daughter--who was then seven--and I went to Moscow for what they call their Winter Festival. We spent eight days in Moscow with opera, ballet, the circus--all those things--and then flew to Leningrad, where we had four days, at a price you just wouldn't believe. We flew from Bermuda to London, took the train to Vienna for three days, a train up to Prague for a few hours, and then a train up to Moscow. Had a great time; eight days in Moscow, four days in Leningrad, train back to London, and then the flight home for a total cost of $1,800.

Gene Williams:

My goodness

Charles P. Trumbull:

That included all meals, all hotels, everything. Those days are gone forever. Two years later, we made the trip across the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Then I did Nachodka, which is a port right next to Vladivostok, and then took a Russian ship down to Yokohama and Hong Kong. I showed my wife and daughter where I used to live in Hong Kong. Then we flew back, stopping in Nepal for a few day and then back on to Bermuda. So, we still do a lot of traveling, even though we're not in the Navy.

Gene Williams:

I know you said when you were doing some of your work in Bermuda that you had at least some contact with submarines--the tracking of Polaris detonations and things of that sort. Have you been back on a submarine since your last tour of duty on a sub? Have you been on one of the nuclear subs?

Charles P. Trumbull:

No. I visited the NAUTILUS when she was just first starting up--the skipper was an old shipmate of mine--and I visited the SKATE, but that is the only contact I've had with them. Since I was on the CHIVO, I spent the day on a British submarine out of Hong Kong, which was quite an experience. We went out to work with three destroyers who were making runs over the HMS TIGER. We'd surface between each run. At lunch time, the skipper wanted to know what I'd like to drink. I said, "Oh, I don't want anything." He said, "Come on, come on. You've got to have something to drink." He urged me so much that I said, “All right, I'll have a gin-and-tonic.” Out comes a bottle of gin and the skipper opens and smells it. He says, "That's no good”; second bottle, "no good”; third bottle, "that's OK." So, we have gin and tonics all around--I think the rest of the officers had two or three of them. The purpose of saying “no good” for those bottles is that any bottle of booze that is

opened aboard ship in the presence of a foreigner, is on the Queen. So, they've got three bottles of gin and the Queen is paying for the gin instead of them.

Another interesting experience like that was when one of the officers on the commodore's staff in Hong Kong suddenly died, a young lieutenant, and I got a call from the chief staff officer. In the very hesitant, stuttering sort of way that a lot of British officers talk, he wanted to know if I'd like to go along for the burial at sea. I couldn't tell if he was asking me because he considered it protocol to invite the American attaché to go along or whether he really wanted me. It suddenly dawned on me that this officer was a good friend of my assistant, Lt. Livings (?) and so I suggested that George go instead of me. You could just hear this sigh of relief come over the telephone. So, it was a four-hour trip out to where they buried the body at sea and no sooner had the splash subsided than the bar opened for the wake. They had a four-hour trip back into Hong Kong and an hour alongside the dock, so everybody got a real snootful--all on the Queen because George was aboard. They really wanted US foreigners aboard.

Gene Williams:

They worked the system to its fullest. What would be nice sometime, maybe down the road--and the fact you live in Hillsborough makes you very, very convenient to Greenville--I think it would be very, very good to get you to speak to life on the submarine during wartime.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Somebody you ought to get is Art McIntyre. He lives out in San Diego. He was on a submarine that the Japanese sank. I think the crew was able to abandon ship and he was

in a Japanese prison camp and very heavily tortured for four years. His history would make an extremely interesting one.

Gene Williams:

And he was a submariner?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Oh yes. He was on his first patrol when the ship got sunk. Then after he got out of prison camp, he was back in submarines again. He's quite ill now, so you'd never get him to come here; somebody would have to go there. He would make an exceptionally good oral history because of his prisoner-of-war status.

He was a severe prisoner of war. He really, really, really suffered.

Gene Williams:

It would be nice to get some reminiscences from you about life aboard the boat and especially your experiences on the GROWLER and the CABEZON, too. Tell me where the Sea of Okhotsk is.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Well you know where the Kuril Islands are; Japan, the Kuril Islands, Russia, Korea. That's the Sea of Okhotsk.

Gene Williams:

I was not familiar with that body of water. Well, is there anything else you'd like to talk about? When you were moved into Naval Intelligence, were the plans for your future discussed with you? Did you know where you were headed with that training?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, we knew there would be more or less three options. One, you would get assigned as a naval attaché or assistant naval attaché, or you'd be on the sea-going staff, because all big sea-going staff have an intelligence division. (Intelligence would be just getting information that is going to be of use to the operation.) Or you would be in some shore establishment such as a Naval district, which would have intelligence officers. The

Panama Canal Zone was the Fifteenth Naval District and we've had an intelligence office with a captain and two or three other officers keeping the Navy informed of anything going on there, any naval interests. Panama, you know, is a big country for ships to be registered in to avoid the laws of the local country. At one point two of us got permission from the Panamanian government to look through their records of registrations of ships, and it was really amazing, because all it was was a bunch of blank page books, in which they had written down the date and the name of the ship. There was no filing, there was no alphabetical order, it was just by chronological order of which ships were registered. It was just complete chaos. We couldn't do much with that.

As I said, I had that job of going around surveying possible landing beaches. They fixed me up with a navy jeep, which they painted a different color and put on local license plates, and my wife and I took off, timing our trips with the local fiestas. We went to this town of Ocú, which was having a big festival and then we covered the beaches in the area.

Gene Williams:

So you'd get down there and there wouldn't be any extra attention paid to your presence.

Charles P. Trumbull:

That's right. I guess there were four or five different fiestas going on in those towns along the Pacific coast, which was the only place that had any good beaches. In other words, the job was to keep sending reports that would be of interest to the Navy as to what's going on politically and maritime-wise.

Gene Williams:

Is that a particular duty that you enjoyed? Was the work itself innately satisfying?

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, I asked for that duty. In fact, in intelligence school, we made a three-month cruise on different types of ships. We pulled into Panama and were briefed by the intelligence office there in the Canal Zone and I thought, “Boy, that sounds like a good job.” I applied for it when it came time to graduate from the intelligence class. Unfortunately, there was no space and I was assigned to the office in Washington, but shortly thereafter, the officer in the Canal Zone was eager to get back to Washington to take some courses at George Washington University, so they swapped us. So fortunately, I got the job I'd been looking for and I had a great time. I liked it very much. I liked the Panamanian people and I like Panama, it was a great country.

Gene Williams:

You got to see a lot of Central America.

Charles P. Trumbull:

Yes, we traveled up through all the Central American countries. I also made a cruise on a submarine rescue ship, down to Peru for a week. I went along as navigator; it was just a recreational trip, really.

Gene Williams:

O.K.

[End of Interview]