| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #201 | |

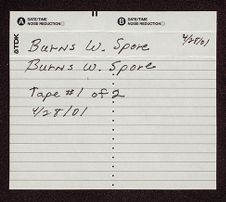

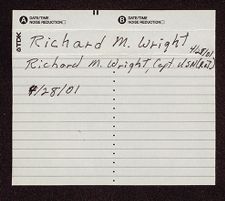

| Captain Burns W. Spore, USN (ret.) | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| 28 April 2001 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Don Lennon |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, start with your background in Maryland. Something about your ancestry there.

Burns W. Spore:

My great grandfather was Captain Robert Boyd, and he is buried right here in the Annapolis cemetery; so if you happen to walk through the cemetery and find Boyd, that's my great grandfather. His daughter married a young naval officer named Burns Tracey Walling, who was my grandfather.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was your great grandfather an Academy graduate?

Burns W. Spore:

Yes, he was the Class of 1856, and he fought through the Civil War. One interesting thing that you probably already knew is that when you graduated from the Naval Academy then, you were not commissioned as an ensign, but as a passed midshipman. He served in, of all ships, the CONSTITUTION during the Civil War. He then was promoted on up to an ensign and then to a lieutenant. They did not have lieutenant junior grade in those days. He spent the Civil War in a southern section down there through the straits and into the interior

and went up the river. He was in charge of opening rivers so they could transport stuff from up North down there without being jumped by the "Rebels" as they called them. Although I'm a Rebel now living in Virginia Beach. But so much for Captain Boyd.

His daughter married Burns Tracey Walling, and that's where I got my name Burns Tracey. They asked me. "Do you want to be named Burns or do you want to be named Tracey" and I said, “Tracy is a girl's name, I'll take Burns.” Of course I being this big . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say, you were pretty precocious to be able to name yourself.

Burns W. Spore:

No, I think it was my father that said name him Burns. So that's where my name Burns Walling Spore, named after my grandfather. He was the Class of 1872 at the Naval Academy. My father, James Sutherland Spore, who was a young officer at the time, married the daughter of my grandfather, Burns Walling. He was the Class of 1909, and he fought through World War I.

In 1918, before the war ended, he was sent to the Naval Academy as an instructor and I was born right here on King George Street in 1918. So everybody says "What do you know about Annapolis?" and I say I was born here, but I never got back until I entered the Naval Academy way back years ago. But of interest too is my Uncle, Captain Harry Hubbard (?), Class of 1925 who married my mother's sister. Then comes along my brother's son, my brother being James Southerland Spore Junior. He could not enter the Naval Academy because of his eyes. Back in those days if you did not have 20/20 vision, you could not get in. So he went to the University of California in Berkeley, joined the NROTC, graduated and went into the navy as a supply corps officer. So the Navy missed

out there. But his son, this was James Southerland Spore III, was in the class of 1970. And then his son Jonathan Spore, because his first son James Spore IV, could not get in. He had some sort of a kidney problem and the Navy kicked him out. Jonathan Spore graduated in 1997 and went into flight training. Now he's an instructor down in Pensacola. So that goes on and on and on.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow, that is incredible!

Burns W. Spore:

But that's the background before you get down to me. I entered the Naval Academy in the class of 1941 and . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Well growing up as part of a complete naval family, I suppose that's all you ever associated with as a kid.

Burns W. Spore:

Yes, of course we lived in Annapolis--I was a tiny baby then--but we went from Annapolis to Des Moines and my father was one of--what do you call those people?

Donald R. Lennon:

ROTC.

Burns W. Spore:

No, before the ROTC. They had where they would set up where you'd join the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Recruitment.

Burns W. Spore:

Recruitment. He was in Des Moines, Iowa for three years while my brother and I were growing up. From Des Moines, Iowa, my dad got orders to Guam of all places. We all went out to Guam and spent two years out there. He was the commanding officer of the station ship the GOLD STAR, which was an ancient old transport that sat right there in Aquana, Guam.

Then from Guam, we came back in a Navy transport all the way from Guam to Hawaii and back to San Francisco. Then you'd get off and go wherever you went, and dad went to destroyers. He had a division of destroyers in San Diego. We moved to Coronado, California and from there I went to High School. After his division of destroyers, he went to the PENNSYLVANIA as navigator. That was really my first ride on a ship as he would take us out to the PENNSYLVANIA to have dinner or lunch on. I always remember my first ride out on one of the gigs on the Pennsylvania because they had to anchor out-- they were based off of Long Beach. As we went out, the ship was going up and down like that and I told the coxswain, "I've got to relieve myself' and I hung over the side. We went alongside the PENNSYLVANIA, and my father's up there on the quarterdeck and here is his son Burns looking very peaked and white-faced. So that was my introduction to the Navy, getting aboard the PENNSYLVANIA.

From there my father went to Portland, Oregon of all places, as chief hydrographer, because of the Columbia River and all of the area up there that we had the Navy. We spent two years up there in Portland, Oregon. Then the interesting thing there, is because of his duty in Guam, the Bureau of Naval Personnel, I think we called it the--what was it in those days--Naval Personnel something-or-other. They gave him orders to Tutuila, Samoa. So we left Portland, Oregon and went out to Pearl Harbor, and went on down to Tutuila, Samoa on one of the Maxum liners--the SIERRA.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were at the age by then, that you were getting to appreciate the. . . sea

Burns W. Spore:

Yes, I was ten years old. That's what spoiled me in fishing. We ran into Tutuila, Samoa, and all you had to do was go out on the end of the pier and throw a line in and in two seconds you'd have a fish on it. They had all--they had tuna and all sorts of things rather unsolicited by anybody. We spent two years there, and fortunately that is when the depression started and the great stock market crash of 1929. My father, before he went out there had gotten rid of all of his stocks because he said, "I'm not going be out in Tutuila, Samoa." Back in those days they didn't have any of the dot-dot-com stuff. You had to send a letter. So he didn't lose anything in the stock market.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow.

Burns W. Spore:

We came back from Samoa to Coronado, California. That's where I went to high school. My father had a squadron of destroyers by this time--based in San Diego. And that's where I was getting up to the age I was--lets see I was fifteen at the time--and my brother couldn't go to the Naval Academy because he was near-sighted. So I studied to go to the Naval Academy. I being fifteen years old, dad said, "Well when your sixteen you can get in," but I couldn't. I took the exams like mad, but in those days, the congressman or senator in your area would give free appointments. And he always gave what he called competitive exams, and I would always stand fifth or sixth or sometimes I'd get up to fourth but never high enough to get an appointment. So my father finally said--and this went on for lets see I started out in Coronado High School, then my father had a heart condition and retired and we moved out to La Massa, California and lived on El Tihado drive. We had an avocado orchard. I went to Grossmont High School, and I kept studying to go to the Naval

Academy. I graduated from Grossmont High School and went to San Diego State College. And I said, “gee whiz, I can't goof around.” By that time I was eighteen and I spent one year in San Diego State College and I took all the courses that I thought would be given at the Naval Academy. Finally, my father, he had told me before he had his heart condition that the only way I was going to get into the academy would be to join the Navy.

So I went down and joined the Navy, was a seaman ninth class or whatever they called it. In those days, the Vice President gave twenty-five appointments from the naval service, whether you were in the reserve or in the active fleet. You could take the examination under his sponsorship. So I took the examination and I was waiting. I thought I'd done pretty well, and of all strange things, Captain Nimitz, who had just made admiral--my father had worked for him when he had the squadron of destroyers and they'd go down to the Naval base there in San Diego to go along side. This is before the war of course, and all it was rather small in those days. But he knew Captain Nimitz in those days, who was the head of that base down there. He went back and was the head of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, or what did they call it, the Department of Navigation. He sent a telegram to my mother and it said. "Burns has stood number twenty-three out of the twenty-five so he has an appointment to the Naval Academy." So I got in, and I always remember that my grandfather was living there then, Burns Tracey Wallings. He was over in Corronado, and we were living out in LaMasso. He and his wife and my mother and my brother all went down to the station and saw me off on the Southern Pacific Railroad to go to Annapolis.

I went all they way up to Chicago, and in those days remember those old trains, they didn't go very fast. Then Chicago down to Baltimore, Baltimore to Washington, and then you took what they called the creeper, from Washington to Annapolis. When I got out there, my mother had sent ahead. We stayed in Carvel Hall in those days. Which now is the--they changed it around--its now the Pacca house I think they call it. Because even in those days when you went in through the old entrance, which was a hundred or so years old, and then back into the main hotel at Carvel Hall, and that's when I entered the Naval Academy.

And we only spent three-and-a-half years there, because our class graduated on the seventh of February 1941.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of experiences do you remember from the Academy days

Burns W. Spore:

Well, I was pretty small. I went out for football, in high school I only weighed about a hundred and thirty-five pounds, but in those days you didn't have to be a giant. And I played running guard and made my letter in High School. When I got to the Naval Academy I said, "Well gee whiz, maybe I can get into this football team." I went into the coaches' headquarters there and said, "I want to go out for football." He looked at me and he says, "Your not big enough to play football on this team." He said, "You better find something else, basketball or something." So guess what I did. I went out for fencing. I thought, well I'm gonna have swords, I better know how to use them. So I spent four years on the fencing team.

Donald R. Lennon:

Huh, that'd be interesting.

Burns W. Spore:

We graduated in the. . . no you want to go back to what we did in the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any high points or any particular incidents? Anything about the instruction or the cadre or your upperclassmen?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, one interesting thing is on youngster cruise, which was--lets see--thirty...? I forget what the actual date was. I was in the battleship NEW YORK. We were coming back from Europe and one of the shafts broke, the main shafts of the engine. The shaft started pulling out. So all the midshipmen of the NEW YORK had to go in with the crew and try to pull this shaft back in to where it belongs so all the water wouldn't come flying in and sink the ship. The rest of the squadron went on up to New York and all on around. We went in the NEW YORK to Norfolk in to the Navy yard there and they put us in dry-dock. We, the midshipmen on board, wondered how we were going to get back to the Naval Academy. And would you believe it, they pulled a barge alongside where the NEW YORK was. We all loaded our sea bags and everything we owned onto the barge, and a couple of tugs towed this barge all the way up the Chesapeake Bay up the Severen River and into Annapolis.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this an open barge?

Burns W. Spore:

No, it had a cabin on top of it, but it was square just like this with a tug here and a tug here. But we enjoyed. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of a glorious way for a navy man. . .

Burns W. Spore:

But we enjoyed it. We were able to look out and see all this stuff, because they only went--I guess--about five knots up the Chesapeake. We were quite upset because all of our

classmates were roaming around up in New York or where ever the rest of the squadron group went. There were two other battleships in that group, so we got in there and thought that'd be an interesting tale for it.

Oh, I did get my "N" star though, in the fencing team. We went up to, they called it the Pentagonal Meet, where five colleges including the Naval Academy and West Point of course were in it. It was held at West Point and at that time I was a Junior, or as we called it a second class. I was on the fencing team and I hadn't kept track of the score because I had been running around and stuff. I got out there and I was a foil man--you know what a foil is--we had foils, sabers, and epees. I was working like mad and suddenly I saw this crowd all around, and they said, "Go it Spore, Go it!" Well I said, “boy I'd better win this match.” Well I won the match and we beat Army fourteen to thirteen.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow, so it was dependent on you!

Burns W. Spore:

So I got my "N" star. And in those days, for a letter in the major sports you just got a big "N", but for the fencing team you had a little "FT," an F on one side and a T on the other with your "N" in the middle. But that was one anecdote. Trying to think of something else. . . Oh, one thing in the first class year, long after we left New York, and I went back to the NEW YORK again. This time her shafts were running ok. We couldn't go across to Europe, because the war had started by then, in 1939, and out First Class cruise was in 1940. So all we did was go down to Guantanimo and back up the coast. We went into Boston and the people in Boston wanted Midshipmen to march down Commonwealth Avenue. They thought, "Gee we got to see how this Navy is doing." So, I've forgotten how many

companies went down, but I was unfortunate enough to be in one of the platoons that had to march down Commonwealth Avenue. And we had our leggings on and our guns like that. As we were marching down Commonwealth Avenue, Jerry Ball was next to me--my classmate. We looked out and there were quite a lot of people out there watching us. And here was this little group of girls, and I said, "Gosh that's a cute little girl over there" a little blond girl--and the other was a brunette, and we kept on going.

Then the ladies of Boston gave us a special luncheon in the Boston Commons, if you know where that is. And then we were able to take off our leggings and turn in our guns. The head man said--I forgotten who we'd got some lieutenant from the ship said,--"All right boys, you have until midnight tonight, so go see Boston."

So Jerry Ball and I walked over to the public gardens. If you remember that's where they have the swan boat and the rowboats and things. Jerry and I walked across this little bridge and looked down, and here were those same three girls in a rowboat. One girl on this oar, and one girl on this oar, and the little blond girl sitting there with the rudder. And one girl would say, "You oar," and the other girl would say "you oar," and the little girl in the back would say "Both of you oar so I can steer." Jerry and I thought this was a riot. Three girls in a boat trying to get under this bridge. About twenty minutes later we were walking through the garden, and here were the same three girls. And one of them ran up to Jerry and said, "Do you know Dick Burks?" Well, Dick was on the NEW YORK with us, but he was smart enough to take a duty so he didn't have to march down Commonwealth Avenue. I said, "No, Dick has a duty, but he'll be ashore tomorrow." So this young lady whose name

was ---(?)---- something like that, brought the other two girls up and introduced them. One of them was named Helen Nelson, and that was the little blonde girl that I was looking at. And Jerry and I, we gave them our names, and wrote it down. That's where I met Helen, who I then corresponded with when I went back to the ship. And I sent her a card and all and thanked her for meeting us there. When we got our orders finally--that was in summer of 1940. And our graduation time was shifted from June back to February. I wanted to go into a destroyer, and when my orders came out, before I was able to open them, I thought "boy I want to go to a destroyer up in Boston so I can go out and see Helen Nelson," who I'd met and we had been corresponding back and forth. And what do you know, my orders had me going to a destroyer in Pearl Harbor. So when we graduated, off I went to Pearl Harbor.

I went to the FLUSSER of the DD368, which was an old destroyer. I went aboard her, and was assistant gunnery officer and first lieutenant. We steamed around and I went through the gunnery course and learned all the stuff I was supposed to do. I went out with the LEXINGTON as her screen and a couple of cruisers. And that's where we were when World War II started. Because we were just south, oh about three hundred miles southwest of Pearl Harbor when the war started. And we had instructions to head southwest and intercept and destroy the Japanese attack force.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why were they convinced that the Japanese attack force was south of Pearl instead of north.

Burns W. Spore:

Well, I only being an ensign didn't know, but looking all through there they thought that they [Japanese] had come from the Marshall Islands, and stopped there. But actually,

the Japs were pretty smart. They stayed way up North knowing that nobody was there. So when we got the word that the war had started, and went southwest and a couple of days later they said, “no, the Japanese were not southwest, they were headed home again.” And we came back in and saw all of the miserable mess there [Pearl Harbor]. The Captain--in those days too, our ships were not at full compliment--the captain said, "Burns you better go over to the receiving station and see if we can fill in all these extra billets, cause the war has started." I went over there went up to the desk and up to the chief there. I said, "chief, I need about thirty men." Well as soon as I said thirty men, I was swarmed. All these people saying, "we'll take any job, anything just get me on board ship." And I did quite well because, I was assistant gunnery officer and myself and this chief gunner's mate, and our top gunner was on the first class. He had been on the OKLAHOMA, the one that turned over, and was in charge of the five-inch battery. And they had five-inch thirty-eights, the same as our destroyers. So he came on board and gosh, he was a great help for--at time. Then our first duty when we got back in with the FLUSSER was to take the battleships that would still float and could move around, and escort them back to either San Francisco off Bremerton for repairs. Our first trip was to Bremerton with one battleship. We then went down to San Francisco and back out to Pearl with a convoy, which they said we better get stuff out there now. We spent the next two months, taking ships back to Maire Island Navy Yard of Bremerton and then bringing a convoy back out. We finally left what was left of Pearl Harbor and headed out towards the Pacific with another convoy. And we spent from--let's see, up until June of that year, escorting convoys back and forth. Really, towards the

end of that, it became known we were the MacArthur Convoy. Because we were bringing troops all the way from the States in APA's or whatever they called them back in those days, all the way out to Australia where we would unload them and then go back again. We thought this is no way to fight a war, just to spend our time doing that.

Finally in the, it was October. . . let's see. . . yes October of 1942. I got my orders to go back to Bath, Maine and take command, not command, but to join a destroyer as gunnery officer. In the meantime, I had fleeted up to gunnery officer on the FLUSSER and head on out. So I went back, went to fire control school in Anacostia. Not far from here, right in Washington. And then on up and here I took another train trip from Washington on up to Portland, Maine and then a bus trip on up to Bath, Maine. I got out and the funniest thing there, was it was then, gosh, early December of 1942. We got in to Bath and I asked the station officer--he was in a little cabin there--"Where is the BOQ." I was going to a ship there. And he said, "Oh its up here about six blocks, you can see it up there on top of the hill." He said "You want a cab?" and I said, "No, no, I'll walk." He said "You better not walk, the temperature out there is minus twelve degrees." So he got on his phone and called a cab and they took me up to the top and I went in to the BOQ there and that started my effort on SPENCE 512. The funniest thing there was that we were there over Christmas and New Years and New Years day. I said, "Now why don't we celebrate this New Years." And they said, "Sure." And somebody had a bottle of brandy or something like that. So we passed around a little thing and we all had our little thing like that. When we got on-board ship and started to go down the Kennebeck River, if you remember where that is up in

Maine. And the Captain said, "Burns, you've got to have the guns ready to fire because when we go out in the ocean"--the, what was the name of that German Battleship, the SHEARNHORST or whatever it was--"Its out there and there looking for single ships that they can blow out of the water." And I said "Captain, I don't know its awful cold." Because the temperature was still below freezing. And when we went down the Kennebeck river, we had to have an ice-breaker ahead of up to crack through the ice so we could get out into Cascoe Bay. I said, "Captain, I've got to fuel the recoil cylinders" and he said "Well get on there and get those guns able to fire!"

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he think that the German battleship would be right off the coast of the United States?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, they didn't know see. That's how unprepared we were. So, would you believe it, here I am down in the forecastle cause I was getting gun one and gun two first with a blow torch heating up a tank of hydraulic fluid to put in the recoil cylinders. It was so cold when I got the things filled. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Wouldn't they freeze again--the recoil cylinders?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, no. One it was in the recoil cylinders and that's inside the gun mount, and the gun mounts were warm. But we hadn't been told that the guns would not be able to fire until we got down to the Boston Navy Yard, because the ship hadn't even been commissioned yet. But old Captain Armstrong, he wanted to be able to shoot those guns if he had to. So we got them all set and ready to go. And I jiggled back and forth to make sure the guns would go back and forth. We got down to Boston Navy Yard and went

alongside the pier. And would you believe that right across the pier is what--the CONSTITUTION. Here's our pier here, and we went along side portside, too. There we are and over here is the CONSTITUTION sitting right there. I said "My gosh, that's a long time ago. My great grandfather was on that ship."

We outfitted, and the steps, would you believe it, we had our shake-down, down in Guantanimo, came back into New York, and our first chore was to take a convoy over to Casablanca, because the invasion there in North Africa had started and we were bringing up re-enforcements. So we went to Casablanca and unloaded all this stuff, came back to Norfolk, refueled and then headed South through the canal and on out West.

Donald R. Lennon:

But in your shakedown or in your convoy, you saw no sign of the enemy did you?

Burns W. Spore:

No, we didn't see a solitary thing. Even the trip across to Casablanca, we never saw anything, nothing. Although, one thing I did and I was senior officer of the deck by that time--Oh, I do have a little anecdote. I went through advanced fire control in Anacostia and they gave me all the information on gunnery and everything else, which I already knew from the FLUSSER, but I absorbed it all thinking that this new destroyer would be highly superior--well it really was, it had better director, better gunfire sup-- but it was a good trip.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you get to see Helen while you were in Boston?

Burns W. Spore:

No, I never--well I haven't gotten quite to that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I mean when you came down to. . .

Burns W. Spore:

If I could go back a little. When we got into Boston, I got all my new people on board, because there was only a small crew up there in Bath, Maine where they built it. I

said, "Gosh, I've got to have some good people to run all these guns and I know the engineer needs them," and I heard from the people on the beach, they said, "Oh, we've got a wonderful crew for you." So I lined them all up and if you remember, the little people you put in as a hot shell man or something, and the big people were the first loaders and ones like that. And the little ones you could put them on the pointer and ?trainer?, If you had to use your gun in local control. I said, "Well line up here." And I lined them all up and took the crew. And I said, "what I need is a good chief, please send me a good chief gunner's mate." And he said, "Oh, he's on his way, he's been waiting to get to you." So on board came this gunner's mate and a couple of so called gunner's mates second class. And I said, "chief, have you ever fired a five-inch thirty eight, they told me that you were an expert." And he said, "Sir, the only thing I've ever fired is a forty-five." [laughs] It was a forty-five pistol. So, with due respect, I had a couple of first class gunner's mates who had come from destroyers and they took over. And I went up and told the captain, and the captain sent this gunner's mate with the forty-five automatic experience back on the beach and said, "We don't need you."

But you talk about going to meet Helen. I had kept in touch with her. And while we were out in Pearl before the war, and this is an anecdote. This was in, gosh, about June of 1941. I sent her a grass skirt and in those days in Hawaii they were real grass skirts not these things made out of what do you call it . . . plastic, a lei. When you could get these artificial leis', and I sent it off to Helen's mother and Helen in writing me said that her mother was absolutely astounded, and said, "Helen you're not wearing that," because you

can imagine back in those days too. Long before your time, the hula gals, they only wore a grass skirt, and I guess they had underpants, but they didn't wear a bra, they just wore a lei. Helen's mother said, "Your not wearing that contraption." And Helen wrote back and said, "I've got your grass skirt, but my mother won't let me wear it, won't even let me try on." [laughs]. Quite a riot I thought.

Anyway, in the SPENCE, we did go back through the Canal and then on out to Pearl. Then from there we joined a couple of other destroyers, and went on down to Efate. Then from Efate we went up to Espiritu Santo. That's where we joined the rest of Captain [subsequently admiral and CNO] Burke's squadron. We were in DESDIV 46 and the other division was DESDIV 45. The two divisions formed up DESRON 23, which was the “Little Beaver Squadron.” And that was in Espiritu Santo, which was just south/southwest of Guadalcanal about a couple of hundred miles. From then on, we fought all the way up and down the slot, as they called it between Guadalcanal and Bougainville.

I don't know how many different battles we fought in. It wasn't until the second of November, that we got into a really serious battle and that was the battle of Empress Augusta Bay. The SPENCE was second in line, and we were DESDIV 45 with Captain Burke on board. The squadron commander was up here, DESDIV 46 with Commander Berny Austin [Bernard L. Austin ultimately vice admiral] was back here astern and we were with three cruisers. The MONTPELER, I've forgotten the name of the other two but you know which they were, and he picked up the enemy coming down. Two cruisers and four destroyers--or six destroyers--coming right on down. So the admiral in charge of the

cruisers and the whole DESDIV, task force 39 told Arleigh Burke to get out there and get those ships. So Arleigh took off and we were still to stern until we picked up the enemy too, another group of two cruisers coming down. And the cruiser admiral said, "Go after them!" So we turned and headed out. . . .

[tape ends]. . . . Burke fired his torpedoes at the two cruisers up North and hit one of them and you could see the flames go out, and we were headed out to the others and Berny Austin--who was on board the SPENCE at the time--gave the signal to come left. One destroyer instead of turning left kept going, and when we all turned left, she bumped into us. She didn't do much damage, but knocked out stuff for a few minutes. In the meantime we were headed straight in towards the Japs. The commodore came running down and he looked at me and said "Burns where are the Japs." Here I am in the pitch black, and I said, "Commodore, I can't see where the Japs are. Why don't you ask the ship ahead of us where they are." So he did, he got on his TBS and said, "We don't have any lights right now, but where are the Japs?" The guy said, "Right ahead of us." So we fired torpedoes and by gosh we hit the SENDAI.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you shot the torpedoes blindly without having any . . .

Burns W. Spore:

Well, the only thing is we lost our lights and we lost our radar down in our CIC. But just about the time they fired the torpedoes, the lights came on. And the guy on the torpedo director up above, he said, "I see MOGAMI right out there.” But our torpedoes did not hit the MOGAMI cruisers because they fortunately when they turned on the lights--our fighting lights as you call them--the Japs could see it and they turned and the torpedo went that way.

In the mean time the ship that Arleigh Burke had hit was off to the right. They were blasting away at us even though they were burning. So we turned and fired at them and sunk them. We still had torpedoes, so we sent two torpedoes into them and it blew the whole thing up. And that was the battle of Empress Augusta Bay.

From that point we went up and down the slot again firing at the beach along Buca Passage and on up to Vella la Vella. If you recall from other historical reports from other destroyer people, they fought all the way up through the slot there and taking Rendova and Vella la Vella and all those places. These had already been taken over by our Marines and Army. We had a place where we could pick up fuel oil and one of the places was at Rendova. As I recall when we went in there and refueled, and Arleigh Burke said, "Ok, we'll start up north and see what we can do." And we all headed up North and got all the way up to what they called the--lets see what was that . . . Rabaul was over here, and Kavieng was over here and we were going up this way. We knew that the Japs were trying to get aviation personnel out of Kavieng where they had an airport and were coming down and trying to hit us in the slot. To blow up that place we went up and we saw that our fighter aircraft were trying to nock out the Japs and the Japs said we better get our people out of there. So they loaded them in four destroyers and headed on up to the northwest. We came up this way, and Arleigh Burke was over here and we picked up the Japs and said, "Here they are, they're coming.” So Arleigh Burke said, "All right, we'll go get them." He fired his torpedoes and blasted one ship. Commodore Austin said, "Well let me get in there and fire two," and Arleigh Burke says "Don't worry about that commodore, you just get the

wounded one and we'll go get the other." And that's what we did. Arleigh Burke and his division went on up to the north and we went over and as fast as he would hit the Jap ships, we would go in and finish them off. We kept on going and I think it was one of the ships, he said, "commodore, if we keep going, we're going to be in the middle of Rabaul, and that's pretty close to the Jap airport." So the commodore said, "All right we'll turn around and head on out." So we turned around and headed south. And that was the battle of Cape St. George.

Donald R. Lennon:

What ship was Burke on?

Burns W. Spore:

Burke was in the OSBORNE, that was the flagship of the squadron. And I don't know why Commodore Austin rode the SPENCE, because the CONVERSE should have been his flagship, but he rode us for quite a while. Then he did transfer over to the CONVERSE-- THATCHER, that was the ship that banged into us.

One interesting thing on this whole episode was why Captain Burke got the term “Thirty-one Knot Burke” was because when the THATCHER had bumped into us, it wrecked something down in the engine room or the boiler rooms, and we only had three boilers. It got saltwater in it or something and we didn't have time to clean it out or fix whatever was wrong. So we started up and Arleigh Burke said, "What's your maximum speed," which should have been thirty-six/thirty-seven knots. Captain Armstrong called him and said, "I'm sorry Commodore, but my maximum speed on three boilers is thirty-one knots." So that's where he [Captain Burke] got the “Thirty-one Knot Burke” thing. The squadron could only go as fast as the slowest ship in the squadron. But we spent the rest of

that month and the following month just going up and down the slot and knocking out all these different things as we moved further north. Although we did go over and join MacArthur's Navy for a little while--we always called it “MacArthur's Navy” because he was fighting his way up New Guinea. We went in to Hollandia and then to Marcus Island up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just shore bombardment?

Burns W. Spore:

Shore bombardment and putting the Army ashore. And he wanted--then MacArthur--I'm no MacArthur favorite. He wanted the Marines to land on Cape Gloucester and I remember the Marines said, "We don't want to go with old MacArthur, we want to stay here with Admiral Nimitz and his group." But they did. They went in and landed on the Cape of Gloucester and took over that area before they moved on up to Leyte and those islands. Fortunately for us, we got out of MacArthur's Navy and went on--in the meantime the battle of the Coral Sea had taken place up there--we headed on back and went on to what we called the Turkey Shoot. And then we went to our invasion of Guam and Saipan and Tinian.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell me about the Turkey Shoot because you all were involved in that.

Burns W. Spore:

Well, the turkey shoot, the Japs were making a one last effort to blast us out of Saipan and Tinian, which were north of Guam. They sent out their carriers and whatever else they had available because in the meantime Midway had taken place. They had lost that effort to get over there but they were still trying to hold onto what was south of it. Admiral Nimitz was able to foresee that the Japs were trying to get back and at least hold

something. So he sent carriers down with us, and that's when the carriers got into what they called the “Turkey Shoot.” Because the Japs started in, they launched all their planes and our planes went out and just blasted them. I forget how many ships were sunk there, carriers and cruisers and destroyers. And I recall when we were screening around the carriers-- watching a few Jap planes come in where the area was just filled with bursts over there as they knocked the Japanese planes down, and they [Japanese] never hit anything. Of course they tried to attack us, who were attacking the Japs' before they got over towards Saipan and Tenia.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were y'all primarily doing screening duty around the carriers

Burns W. Spore:

Yes, we were the carrier screens. And also one job that we had, which wasn't much fun was plane guard duty. We were--here's the carrier and we were right here in case somebody didn't land right we would be able to pick them up. And we did pick up several pilots and we'd go back alongside the carrier whenever its flight operations were over and they would pass a line over and we'd send their pilots across. And one good little anecdote on this is every time we did that the carrier would always send ice cream over to us. Of course we didn't have any ice cream making ability.

Donald R. Lennon:

So y'all were hoping that more pilots would land in the drink. [laughs] The SPENCE was not attacked by Japanese planes during this?

Burns W. Spore:

During the slot, we were attacked a number of times and one interesting thing when we still had Commodore Austin on board. He was a commander at the time. Captain Burke was on the OSBORNE. I was down in CIC and the sonar up on the bridge. We were

coming back down the slot. This was during the last phase of Guadalcanal and the Japs were still on one end of it. The sonar man picked up a contact, it'd go "Ping" and you could hear them and you could see the little thing. He hollered down and he said, "Combat, we've got a submarine." The commodore went racing on up to the bridge because that's where our sonar room was in those days and they'd watch the thing. Sure enough, there was a Jap sub there. So, we went over and dropped a bunch of depth charges and was just coming up daylight at the time when we dropped the depth charges. Then the THATCHER came in and dropped a bunch of depth charges and came on out. An all of a sudden the bow of this submarine came flying up out of the water. And one of--I don't know whose depth-charge it was whether it was the THATCHER or ours--had blown the whole conning tower off. This was just the last gasp by the guy steering the submarine I guess. Cause the bow came flying out of the water and it just flopped over like that and sunk.

Donald R. Lennon:

No survivors from it that you could pick up?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, we didn't see anyone in the water. I think this was just the last throes of the submarine coming up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you take, or did the SPENCE take credit for it, or did the THATCHER?

Burns W. Spore:

I think both of us did. [laughs] In those days everybody took credit for everything. Every time a plane was shot down, a guy would say, "I shot them down." Even though he was fifteen miles away.

We did pick up one Jap though, on one trip down. Apparently, one of the planes that had been shot down, probably by one of our own fighters coming from Guadalcanal.

Somebody on the bridge hollered that there was a man in the water and he was floating on some wreckage. We went alongside and picked him up and it was just a Jap and all he had on was just a g-string and a little packet. We put him back in the carpenters shop. Right next to the carpenters shop is sort of a little . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Brig. . .

Burns W. Spore:

. . . thing back by the steering engine. We put him in there and locked the door and gave him water and everything else. And a couple hours--they had a man standing by there and then when it was dark--the man standing by, he hollered up to the bridge and said that the prisoner was hanging. What he'd [prisoner] done was taken his g-string off and built himself a noose and hung it up over a rafter in the room and hung himself. Those were the Japs.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he was dead by the time they got to him.

Burns W. Spore:

Yeah, by the time our doctor got to him he was gone.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were saying he was in the water, I have heard that many times that they try to keep from being picked up. That they would swim away from the ship.

Burns W. Spore:

Oh, I had another little story too. We went by a raft from one of the planes that our fighters had shot down. And there was a Japanese officer and four men in the raft. We were going to go pick them up and the Japanese officer had a rifle. I was up on the forecastle and I had a tommy sub-machine gun and I asked the captain, "What do we do, shoot them or bring them alongside?" And the Captain said, "No, that guy is killing his people!" And sure enough, I looked over and here was this Jap officer taking his rifle and shooting each guy.

Shot them in the head. And then he took the last--I don't know if it was the last bullet, but he took the rifle and turned it around stuck it in his mouth and reached down and pulled the trigger. Blew his head off. That was the Japs for you.

A little more comical thing was the raft came alongside. One guy said, "Hey I want to get that watch off that dead Jap down there." And he went over the side on a ladder down there, they were going to haul these Japs up thinking we could save them, not knowing they were going to kill each other. He took off the watch off this dead Jap and crawled back up the ladder. Guess what kind of watch it was? [laughs]

Donald R. Lennon:

Elgin?

Burns W. Spore:

[laughing] No it was one of those cheap little Mickey Mouse things. One of those little things you'd get for a dollar. But he kept it. But that was the SPENCE. Anyway, the SPENCE came back into Hunters Point in San Francisco, went into dry-dock, and I got off the SPENCE and I had orders back to the DUNCAN, DDR 874. It was being built in Orange, Texas of all places. And I went home--they gave me three weeks leave--because I hadn't had any leave since the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

About when was this?

Burns W. Spore:

This was early October 1944, when I left the SPENCE. We got back in September, but I stayed with the SPENCE while she was in dry-dock and they were ready to go. In fact, I took her out and went out with her on engineering tests after the overhaul. Came back in and I got off. I was relieved by incoming exec. Because in the meantime I had become executive officer, because the original exec. had gone off to his own ship.

I think I mentioned this. As gunnery officer I loved to fire the guns. When I became exec., I was down in the stupid CIC just watching the radar scope while everyone else was sitting up in the gun director, doing all the firing. But I got off and that was early October, the SPENCE went on out. And as fortune would have it that was October, and the SPENCE went down in the great typhoon on 17 December out there with Admiral Halsey's group. And what was most unpleasant to me, I having been exec of the SPENCE, a lot of these people knew that I was still alive. They wrote me letters thinking that I had been with the SPENCE when she went down. And it was very difficult because...

Donald R. Lennon:

Was all the crew lost?

Burns W. Spore:

We had twenty-four survivors, that's all. They were picked up by two or three destroyers that were sent out to pick them up after the typhoon went by. And the poor old SPENCE went along side the NEW JERSEY to try to refuel, but it was so rough. I'm sure you've read that book Typhoon, by a naval officer that was on one of those ships. They go alongside to try and get fuel. The waves were so big, that they couldn't get a fuel hose over or if they did get a fuel hose over they the next big wave would come along and just sweep it off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that why they went down, because they ran out of fuel?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, the SPENCE went down because in order to take on fuel, you got to pump out what's left of your ballast water when you fill that tank with fuel. And they were pumping out so they could take fuel on board. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

So that made them so light?

Burns W. Spore:

Yeah. And when they, when admiral Halsey finally said "Well, you better give up fueling and take care of yourselves" and the SPENCE went off and the hurricane hit them full speed. The SPENCE just flipped over, and down she went. The supply officer Al Kurchunes was one of the survivors, he wrote quite a story on the loss of the SPENCE. I don't know whether you have that or not, he sent me a copy.

Donald R. Lennon:

I just don't remember right now.

Burns W. Spore:

I could send you a copy of that. It's a story of the whole loss of the SPENCE and what happened afterwards.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, once you moved on to the DUNCAN in October 44 what uh. . .?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, that's, you mention my girlfriend Helen. When I got orders to the DUNCAN and left the SPENCE, I went home. And of course we were living out in La Mesa, California at the time. And I had this picture of Helen and I showed it to my mother and I told her that if the war ever ended, I was going to marry this girl. And my mother...[laughs]

Donald R. Lennon:

But you'd only seen her really--face to face--what one time? [laughs]

Burns W. Spore:

My mother said, "War or no war, you better marry her now or you might never!" [both laugh]. So I called up Helen, and of course we had been writing back and forth since. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

But had you had any real time together other than that brief interlude?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, this is another little story I have. When I was on the SPENCE, and we went in to Boston Navy yard, and went alongside the CONSTITUTION, I went out to see Helen. She lived in Arlington, Massachusetts, which was right near Cambridge. She told me how

to get out there. The war was going on so you couldn't rent a car the way you can do these days. You'd take the subway out to Harvard Square and a bus up to Highland Avenue. Then I'd walk about a block to her house. Well I got off the ship, walked up. By the time I got to the subway, snow was coming down. And I said, "Where do I get the bus to go up to Highland Springs?" and they said, "We're very sorry, but there are no busses running." So I said "What am I going to do?" and just about that time--Oh, and then they said "Oh you can catch the street car, that'll take you up Highland Avenue." So I went over and caught the streetcar and they were still running out in the middle there, and got almost to Highland Avenue. I saw a police station on the corner, and I said, "Well those guys will know how I get from Highland Avenue up to Armont Street.” So I went over to the police station, and I was wearing a uniform, because you had to wear it then. I walked in and I said, "Can you tell me how I get to Highland Avenue, because I have to go meet a girl who lives on Armont Street?" One cop was standing there and he says, "Oh, I'll take you up there, I'm going that direction anyway." I climbed in the cop car, we go on up Highland Avenue, and then on up this way and go down to Armont Street, and stop in front of Helen's house. And he had his light going on so people would know there was a cop car there and not something--her father [laughs] looks out the door and sees this police car and I get out. And he thought my gosh, why are the cops bringing this guy up to see my daughter. And of course, the Nelsons only had one girl, they didn't have any other kids. [both laughing]. I thought it was a riot. So, I went up there and finally got in to talk to Helen, her father and mother and all. but I

didn't marry Helen until I was on the DUNCAN, but this was an anecdote way back on the SPENCE.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, right, I understand.

Burns W. Spore:

So anyway I got off the SPENCE finally and showed that picture of Helen to my mother and she said, "You'd better marry her now or you'll never marry her." So I took a plane all the way to Logan airport, outside of Boston, and her father met me down there and took me up to the house. And we were married on the 29th of October. And then, of all things, we bought a Chevrolet--an old 1939 Chevrolet--to drive all the way to Key West, because I was going to go through sonar school. Because the DUNCAN was being constructed down in Orange, Texas, if you know where that is. It's not far from Galveston. So we drove all the way down, from Boston all the way down Route 1. Cause in those days the war was going on and Helen had a ration book. Remember the ration books in those days?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes indeed.

Burns W. Spore:

And I had about four coupons. You had to have a coupon to get gasoline. Well Helen's uncle, Carl Nelson, he headed up the--what do you call the outfit--Public Works Department, of Worcester, Massachusetts, which isn't far from Boston. And he said, "Don't worry about that, I'll take care of it." The next day he came back with a whole sheet of q-coupons. The only thing is they were truck coupons and each one of them was fifteen gallons of gas. So all the way down from Boston to Key West, we had to make sure the tank was almost empty because . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Because fifteen gallons was all it would hold.

Burns W. Spore:

Fifteen gallons was all we could do. And the oddest thing of all--which is rather hilarious now--is that there were very few gas stations open, and even fewer motels. So, we'd always have to say, "We got to find a motel and a gas station near by, so we can spend the night and then get some gas and then head further south." And we got down to Miami, and I said, "We better stop here, and I can call down and see what we have down there." In the meantime my mother had made reservations for us at the Casa Marina Hotel in Key West for us, and sent off a trunk of junk for me to wear. Because I had to catch a plane when I went on to meet Helen. And we got there and I called down and they said, "Oh, don't bring your wife down here, the war's going on and there is no place to stay." Well, I didn't believe them. I said well all right, I'll go down and I'll let Helen come down later. So here she was in a hotel in Miami Beach, and I drove the car on down to Key West. I got down there, and found there were a lot of places to stay. Went out to the Casa Marina and said "Sure, your stuff has arrived and we've got a room for ya and everything." So I called Helen and she says, "How am I going to get there, [laughs] walk?" and I said "No fly down." So she called and sure enough she could fly from Miami to Key West. And she said the only problem is when they got on the plane they made them pull down the curtains. You couldn't look out the window because the war was going on and remember Key West was down. So she flew down and I met her and we went out to the Casa Marina.

Every day, I'd have to go down and go out on the ship because they took us out to--the purpose of the Key West trip was anti-submarine warfare. They'd show you all the new

things that they had and they had all this stuff. We then drove back all the way from Key West to Norfolk. And what I had to do and also my brother's wife's family lived in Norfolk we were able to check around with them and they got us an apartment in Norfolk. And I went off to the DUNCAN down in Orange, Texas.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the DUNCAN going to be stationed in Norfolk--or why did you select Norfolk?

Burns W. Spore:

We didn't know. The war was going on at the time and they didn't know what was going to happen. So I went down to the DUNCAN and what I did was I put Helen on the train--no I took her home, that's right. I was the one who caught the train--and I still had my car. So we took the ferry and if you remember that down there, they didn't have a bridge tunnel in those days you had to take a ferry from Norfolk over to East Port on the Eastern Shore. And then take a train all the way up to Wilmington and on North if you want to go there. So I had what they called the balance crew in Norfolk for the DUNCAN. The captain and the gunnery officer, I was the exec of the DUNCAN. I was in Norfolk with the balance crew and the captain and the gunnery officer and the engineer were down in Orange, Texas aboard ship with what they called the nucleus crew which were the gunners and the enginemen and people like that. So, I took Helen and we got on the ferry and rode the ferry across. Drove all the way up the Eastern Shore. The only thing is our Chevrolet had no heater, and here it was early January by that time freezing cold, and here I'm trying to drive this stupid car. And by the time we got up on the Meritt Parkway, the weather had improved a little and we were able to get on to Boston. I dropped Helen off and I turned

around and took the train back. If you recall, the train goes straight down from Wilmington all the way down the Eastern Shore. I don't know if they still run that or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

No.

Burns W. Spore:

Then I took the ferry back to Norfolk. And then my brother's wife's family picked me up there and took me over--back to the Naval Station with the balance crew. I was only gone two days so they didn't mind it.

But the strangest thing there, and this is another little anecdote, was when we were ready to move, we had to assemble the balance crew and make sure we had all the people. We got on the train, all of us, and took off from Norfolk and headed to Orange, Texas. The most hopeful thing was that we'd stop every now and then at one of these little stations and there must have been--oh a hundred people--would come out with food. Anything we wanted, they'd give us. And we'd all jump out of the train and everybody would get sandwiches and all and stuff. Oh, they did feed us on that train. And it took us two and a half days to get from Norfolk to Orange, Texas in that troop train.

We finally commissioned the DUNCAN and we went down the river to Galveston. And you know where Galveston is.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right

Burns W. Spore:

We outfitted some more there, and then we got orders to proceed to Norfolk. The captain said, "Why in the world are we going back to Norfolk?" We found that they were going to put a new radar on the ship. The people of Galveston had just put up all this radar and everything else. And the Captain says, "Well take it all down." and they said, "No

we're not going to take it down, we're getting paid to put it up." [laughs] So they put up this radar and we got underway and went all the way back to Norfolk, and then as soon as we get into the Norfolk Navy yard they tore down all this stuff and put up the other thing. Because they were making us a DDR with a height finding radar, which was up there on the mainmast. And we spent, I guess it was about six weeks while they did all that. In the meantime Helen and I lived out there in a little apartment project in Norfolk. And I would catch a ride down to the boat slip which would take us across the river and over to the Navy Yard.

And the DUNCAN--finally we got underway--went out tested everything and then headed south through the Canal. In the meantime Helen had gone home. The war was still going on. We went down through the Canal. On out to Okinawa. We got our battle assignment. And we being a DDR, we were called a radar picket destroyer. The captain opened his orders and here we were assigned a picket station. Here's Honshu up here and here's Okinawa down here, and here's Iwojima. And Iwojima, the battle of Iwojima had long since finished, so we were down here on Okinawa. Our job was to take station up about here. The bombers were going in and blasting the Japanese ports then. Yokohama and also Tokyo, they'd dropped I don't know how many thousands of incendiaries burning up all sorts of stuff. Our job being a DDR--when the bombers were returning--was to check each flight going back for the proper IFF (Identification Friend or Foe.) and if we'd pick up an echo up there--or a plane really, we called them echoes--with nothing or an incorrect IFF, we'd alert the combat air patrol that would fly out of Iwojima. That was the main reason for

taking Iwojima, was to give protection to the bombers going in. And they'd fly up and down and spot the plane and if it was a Jap plane they knock them down.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the Japs did try to conceal themselves in the. . .

Burns W. Spore:

Yeah, they tried to. In darkness, you really couldn't tell if you had a plane right near you unless you shined a light on it or something. And the captain--Captain Williams it was--wanted to...

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these Japanese bombers or fighters?

Burns W. Spore:

These were fighters. What they were going to do was wait until the planes dropped down near the landing spots so, they would ruin the runways. And Captain Williams took a look at that and said, "Boy we're going be up there about a week, but I'll give us about three days before the Japs' figure out what were doing down there and they're going blast us out. So you better get off something going home and tell them your going to be in a pretty sad situation." Just then, I got my orders. I was sent to the RALPH TALBOT DD390. Captain Williams said, "Burns you better get off the ship, because you may never get back to go to the 390." [laughs] So that's when I joined the Army.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well did y'all--when you were still on the DUNCAN--did you actually spot the Japanese planes hiding among the American bombers?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, that's why I said I had joined the Army. We had gotten our orders and we were going to leave, I think it was two days later. That's when Captain Williams said, “Burns, you better get off or you may never get off again.” And the RALPH TALBOT was still off in the Iwojima area. And we got word that she'd be back in a couple of days. So

Captain Williams said, “You'd better get off and get over there on the beach.” And that was in Buckner Bay. So I got in the whaleboat and they took me over to the landing right up there in Buckner Bay. I got off and reported in to the Army and they were in squad tents. I showed them my orders and said, “I'm going to be here for a couple of days. Where do you want me to stay?” And they said “Oh, go on over to that tent right over there and you can check in.” I went over to that tent and checked in and they gave me a gun belt with a 45 and I said, “What do I need this for?” and the guy said, “Well, those hills up there not too far away are full of Japs, so be careful at night. Don't go lightin' any cigarettes.” And I said, “Well I don't smoke anyway so it won't bother me.” So I walk over with my 45 and said “Well, where do I eat?”--oh and I did have an ammunition belt too. I had my duffel bag and wearing my cap.

In the meantime, I had made lieutenant commander, you see I was lieutenant the whole time I was on the Duncan until underway for Okinawa. And the captain, fortunately, Captain Williams had a couple of brass lieutenant commander things because he had made commander in the meantime. We'd call him captain, but he was a commander. So he gave me the Stars or the brass things for there and said, “You're not a Brass hat anyway.” [laughs] says, “That'll do for now.” And so I went on over and said, “Where do I eat?” The guy who had issued me the 45 said, “Over here in this tent, it's about a hundred yards down the road.” I went down the road, checked in with the place to eat and they gave me a little pan [laughs] what do you call those little pans? A fiel...

Donald R. Lennon:

A field kit.

Burns W. Spore:

...d kit. Where the thing folds down like that, and a canteen.

Donald R. Lennon:

Standard issue.

Burns W. Spore:

Yeah. So I had my combination pan and canteen of water and inside it was a little fork and spoon down there, made out of aluminum. And I said, “My God, I'm in the Army now with a 45, [laughs] this kit over here, and a canteen.” I said, “Where do I get the water to fill this canteen,” because it was empty. The guy said “Oh, see that pipe over there with the spigot on it?” he said “Go fill it over there.” He said, “Don't drink the water if it comes out of a faucet, because we don't know what's in the water around here.” So I went over and filled my canteen with the Army water.

Then I looked down on the beach and here was a Navy signal tower. So I said “Yeah, when that ship comes in”—I knew what the RALPH TALBOT looked like. It was a one stack destroyer and I looked out and there in the bay just coming in was a one stack destroyer. So I walked down to the signal tower and went up and talked to the chief signalman up there and said, “Please send a message out to that ship.” And I looked through his binoculars and it wasn't the RALPH TALBOT but it was a ship in the squadron. And I said please send the a message and said, “Please send boat for officer.” He blinked it out there and back came an answer, “Boat on the way.” Of course you couldn't use the radio or anything there for fear that the Japs would hear it and know what was going on while the war was going on. Sure enough in came the whaleboat and I hopped on the whaleboat. Went out to the HELM, that was the name of the destroyer in the same squadron. I walked up and the captain came down and he says, “I have a problem captain because there's a

typhoon coming up the coast and we've got to get on our way and get out of here.” I said, “well I'm supposed to get to the RALPH TALBOT.” He said, “ RALPH TALBOT will not be able to get in either, your just going to have to ride along with me for a couple of days.” So out we went and got hit by this typhoon and boy it was not really bad, but it was bad enough. But after two days the typhoon--if you recall a typhoon, how those things move along it doesn't take long for them to get through. We went back in and the RALPH TALBOT arrived. So I climbed in the whaleboat again and head out towards the RALPH TALBOT. I got on board and went up told them who I was I still had my 45 and my mess kit I brought that home with me. And Captain Brown, who I relieved, you wouldn't believe it, but he was in the Class of 1936 from the Naval Academy, but he had gotten out before the war started. He was recalled at the beginning of the war and he was only a lieutenant commander. So he got off and I was Skipper of the RALPH TALBOT. We were the first ship to go into Sasebo. Our first orders were to proceed with a cruiser--I forgot the name of the admiral on the cruiser--to enter Sasebo Bay--and you know where Sasebo is.

Donald R. Lennon:

Honshu.

Burns W. Spore:

Well it's on Honshu, but its up to the north. They dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, Nagasaki that's what I'm trying to think of.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can I ask you a question before we get too far away? Did you find out whatever happened to the DUNCAN? Did it get blasted?

Burns W. Spore:

No, in fact I was just about to say, when I got onboard the RALPH TALBOT and took command, I'd no sooner taken command when we got underway and went out for a

couple of exercises I guess. But there were Japs, we never got out onto a picket station so we were never able to fire at any Jap planes coming in and I was just as happy or I wouldn't be here today. Then the war ended and that's why I said when the war ended, the DUNCAN was still in port. They hadn't--at that time Harry Truman was toying with the idea of dropping the bomb on Hiroshima. And by the time he said, “Yes, drop the bomb.” They said there's no sense sending people up there to get blasted by what's left of the Japanese air force. So they pulled back all those people that were just around there. And the DUNCAN never was touched. Although, even while I was there, the PENNSYLVANIA got hit by a kamikaze right in Buckner Bay. But anyway, we got underway with a cruiser and went up to occupy Sasebo. The war had ended. The RALPH TALBOT was ahead of the cruiser. There was the cruiser, the admiral and his captain said, “ RALPH TALBOT, you better go in first there may be some mines.” [laughs]. Nobody believed the Japs anyway. So we went on in and I had a whaleboat out ahead of us, one of our whaleboats. And they were watching to make sure there was nothing floating around.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you had no mine sweeping potential there at all.

Burns W. Spore:

No, we didn't. Nor did a cruiser and a destroyer. But really the Japs had nothing in Sasebo harbor at all. So we went on into Sasebo harbor and took possession, and that's where I thought that a lot of these people were senseless. We went over to the beach and each commanding officer was assigned a Japanese escort and my guy was a Japanese commander. He spoke fluent English. He was a graduate of the University of California. But he never spoke about the war or anything, he, said “Well, I'm just here to help you.”

But our job, I don't know if anyone has told you this, was to go around and make sure that the Japanese fleet, whatever was left of it, that their guns had been dismantled to the point where they couldn't fire. And the darned admiral on that cruiser he said, “Be sure to pick up all their sextants, I want to get a good Japanese sextant.” And I said, “Well heck, these people might need those things. We don't need sextants.” So I refused to get--Oh, and he also wanted chronometers too.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he want those for souvenirs or something?

Burns W. Spore:

I guess so. I said, “I don't want any Japanese sextant or chronometer.” I went around and made sure that breech blocks of the guns were pulled. Usually what we did was just pull out the breech block and throw it off the side and then you couldn't fire the gun. And they had guns similar to ours, five-inch thirty-eights or the forty millimeters. They had the same thing, all we'd do was take the things and throw them away. And that was our job and we worked for--then we turned into a mail boat. We'd go down from Sasebo and around down--the cruiser in the meantime had gotten underway and headed out. We'd go from Sasebo to Nagasaki, and that's where I saw what damage had been done there. That's where the second bomb was dropped. They really hadn't damaged Nagasaki nearly as badly as Hiroshima was damaged.

Donald R. Lennon:

Didn't you feel, being concerned, being in that area shortly after the dropping of the atomic bomb?

Burns W. Spore:

Yeah, we were, we were. But we had to do what we were supposed to do. When they said go ashore and check on it, we had to go ashore and check on it. I had to fill out a

form for possible radiation damage to me, but I never suffered any damage. And I've always believed that it was a little bit elevated all this nonsense about radiation. Once the bomb dropped, there was very little radiation left that was all in the air. And that leads me on to another story if you still have time. But . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Bikini?

Burns W. Spore:

Bikini. Where we did have radiation. In fact that's where I lost all my hair [laughs].

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what happened to me? I wasn't there. [laughs]

Burns W. Spore:

You were on Bikini too.

But we were on this mail run from Nagasaki to Yokohama and back up to Sasebo and on around for about two weeks. I remember coming into Yokohama, we spotted these floating mines this time. Two of them. And what we would do was to come out from about here to about that telephone post and open fire on them with out forties and blow them up. And we were steaming along an in came this great big freighter charging in here and we sent a message over and said, "Proceed carefully, there are mines ahead." And the guy, he just flashed back and said, "Message received," but kept right on going. Just about that time, the gunners up on the forecastle, blew up a mine, which couldn't have been more than half a mile from that big freighter. All of a sudden smoke poured out of the stack on that freighter and he was backing full [laughs].

Donald R. Lennon:

He put on the brakes. [laughs]

Burns W. Spore:

And he turned around on a dime whatever a freighter does and went back out. And he flashes over to us and says "There ARE mines here aren't there!"

I took the RALPH TALBOT back to San Diego, via Pearl Harbor. And one interesting thing as we pulled into--what the heck is that. Not Wake Island, but up north. . . where the airplanes used to come in [Midway ?]. Anyway, we pulled in there and I went ashore and here was a supply officer and he says, "Hey, do you people need any frozen foods?" And I said, "Yes we can always use some frozen foods." He says, "We've got a whole warehouse full, which was going the other way and the war ended and we still have it here. So please bring your boat in and take anything you want." By gosh, we were able to get steaks and anything. Loaded the ship up and brought it back with us. What the heck is the name of those islands up there? The Navy finally gave it up--on the way back from Japan and all those things.

Donald R. Lennon:

I should of brought my map of the Pacific.

Burns W. Spore:

No, what was the famous battle up there that took place. Where Nimitz sent the carriers up and met the Japanese forces and really turned the war around. It's the name of an island.

Donald R. Lennon:

You've got the Solomons. . .

Burns W. Spore:

No, this is way over near Pearl. Don't know why I can't think of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because Midway was the one that turned the war. . .

Burns W. Spore:

Midway. Midway Island. We pulled into Midway and that's where they had all this food, because ships would come through and load up and go on out. And we got steaks and lamb chops and everything else.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then you came back to the states and. . .

Burns W. Spore:

We came back to the states, came into San Diego. Meantime, my wife had come out to San Diego and was staying with my family, who lived in Coronado at the time. And our orders were to refurbish. We went down to the Naval Station there in San Diego. And then we went around through the Canal and back to Boston where the ship was commissioned way back in 1937 I think it was, and decommissioned. Then Harry Truman came out with a big statement that they wanted to conduct these atomic bomb tests and for the Navy to pick suitable ships to participate. I got orders to participate [laughs]. Immediately, and if you remember the point system in those days. If you had enough points, you could get out of the Navy, especially enlisted people and the reserve officers too. So here, all these people were tickled to death, cause a lot of them had commissioned the RALPH TALBOT way back in 1937 and were still riding it. They were tickled to death to go around through the Canal and up to Boston and decommission there and then go home. As soon as they found out that we were going to stay there and go to Bikini, Bang! Off they went. And it ended up with me and three officers and a hundred men, and that's all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well at Bikini, what was your chief responsibility. Were ya'll just observers or were you. . . what was your involvement in the. . .

Burns W. Spore:

We were assigned as one of the target ships. And we went out to Bikini, we stopped at Pearl Harbor and spent one month at Pearl Harbor for a complete overhaul in the Pearl Harbor Naval Yard. Once we had completed our overhaul, well there is a little bit of an anecdote here. We were told that the atom bomb test wouldn't be for a year, and to go ahead and decommission the ship and we could all go home. So here we were wrapping up,

putting seals on all this stuff. Then Harry Truman sends out another report saying, "The atom bomb test will be conducted in July." And here originally, they weren't to be conducted until September or October. And we were supposed to get off the ship and they could haul it out there. So we were told to--we hadn't decommissioned the ship--we were told to undo all of the buttoning up we'd done and put the ship back into commission and get ready to get on the way. So that's what we had to do. So more of my people left. We went out, finally to Bikini, with two boilers on the line and a maximum speed of fifteen knots.

Donald R. Lennon:

Goodness gracious.

Burns W. Spore:

We no sooner get to Bikini, and out station--I can draw you a picture--the PENNSYLVANIA, we escorted the PENNSYLVANIA out there. She was the target and they painted her bright red. Ugly.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now the crews weren't left on these target ships.

Burns W. Spore:

Oh, no. Here was the PENNSYLVANIA, and the RALPH TALBOT was here five hundred yards south of the PENSYLVANIA. And then they had other ships around here like this. All different kinds, they had destroyers. The MUGFORD, which is interesting, the MUGFORD was up here. The MUGFORD was Admiral Burke's original ship. He left the MUGFORD and went back someplace. But he was in the MUGFORD during Pearl Harbor. And they had all sorts of things around here, but the PENNSYLVANIA--we were five hundred yards from the PENNSYLVANIA and the Army Air Force, and back in those days we didn't have an Air Corps if you remember. They were going to drop the bomb on top of the PENNSYLVANIA. Well, we got everything set up here and all of these experts came out

with all these sensors and all these things to measure pressure and put them all over the ship and everything else to see what the effects of the atom bomb would be. And put all over the ship. And we got out, got outside. Got on board the HENDERSON, which was an APA, and stayed off the coast for the test. And the first test, was supposed to be dropped by the Army Air Corps. They came in and dropped the bomb. The bomb, instead of landing on the PENNSYLVANIA, landed up here about a mile north of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no! I didn't know that.

Burns W. Spore:

We on the RALPH TALBOT, only five hundred yards from ground zero, we figured well if they ever hit the PENNSYLVANIA, there won't be anything left of the RALPH TALBOT. But even so, where the bomb dropped up here, there was enough blast from it, that this is say the galley deck here and that's the galley there and this is the wardroom up here, the force of that explosion coming through just shattered everything in here. And knocked everything. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Well what did it do to these destroyers--these ships up here?

Burns W. Spore:

Well, the MUGFORD was completely dissolved, it just went down flat. And so did a lot of the other things here. but the PENNSYLVANIA was still in good shape. She was highly radioactive. They came on board us and where we were pretty far away, we had slight radioactivity. We were told to go ahead and help the people because they were now going to get ready for a surface blast, which came three weeks later. And they rescheduled, because a lot of these ships had sunk in the meantime.

We put up more instruments and all. And we watched the blast, and that's where I lost my hair. What they do is they gave you dark glasses to watch when the bomb went off. And when the bomb went off you saw this great flash of light and a column went up like this. We were far enough away, the HENDERSON was way out here must have been at least ten miles out and you could just barely se where Bikini was. We were close enough where you could see the great flash and the column, I'm sure you've seen that on many things. So the second blast was actually on a tower on top of a float, which was located here. When it went off, it was quite something to see. We couldn't see it, but maybe you've seen the films of it. When the blast went off, it sent up this great column of water as if you were blowing it up out of a bathtub. It was completely radioactive. This washed over the RALPH TALBOT. Once it was over, we came back to check it. And we all were little photo badges on us to make sure we didn't get excess radiation. And we were told to try and clean up the ship so the target people could go around and check all their instruments and things, which they did. And we tried to clean up the ship as best we could. And I remember our chief boatswain's mate. Went over and in it--Oh, I should mention that if your radiation exceeded a certain amount when you went back to the APA at the end of the day, they would check the radiation on your little badge and if it exceeded a certain amount, you couldn't go back. But the botswain's mate sat down on a cleat up in the forecastle while he was watching these guys. When he got up and went back, his radiation badge had completely gone off the scale [laughs]. And they said what did you do? He said, "Well I was just sitting on a brass cleat." They said, "Oh, you should never sit on brass cleat. That

thing was highly radioactive." [laughs]. So everybody said, next time we go over there, we'll all sit on brass cleats. [laughs]

About that time they decided it was hopeless. All of the experts had gotten their readings and everything they had needed. So we were told to decommission the ship and go back on the HENDERSON and head home. So that's what we did. We took the flag down, and I still have that flag even though it wasn't radioactive. We decommissioned the ship and all of us went back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting. Now you had some classmates out there too didn't you?

Burns W. Spore:

Never saw them at the time, because I just went to the HENDERSON, and they went back to their ships wherever they were at the same time.

Donald R. Lennon:

My mind has just gone blank.

Burns W. Spore:

But there were several.

Donald R. Lennon:

One was from Florida who died a couple of years ago. I saw his widow just a couple of days ago, was at Bikini. And his name won't come to me right at the moment.

Burns W. Spore:

But that was my RALPH TALBOT experience. And I better hurry up it's already twelve o'clock.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yeah, it's twelve. I hope that there will. . .

[End of Interview]