| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #177 | |

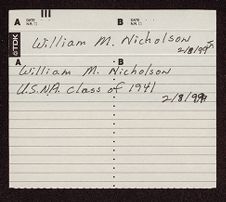

| Captain William M. Nicholson | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 8, 1999 | |

| [Read and Edited by H. A. I. Sugg, USNA 1939] |

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you grow up, what led you to the Naval Academy, and what was your education like?

William M. Nicholson:

I was born in Napa, California. My parents divorced when I was very young. My mother and I lived all over California. We went to southern California and lived in Huntington Beach, Long Beach, and Santa Ana. I spent a lot of time swimming and watching the Fleet that anchored there. I became interested in the Navy by watching the old carriers SARATOGA and LEXINGTON rolling back and forth. They used to dip their boat booms in the water just at anchor. Then we moved to northern California. I went to school in the San Francisco Bay area, graduated from high school at sixteen, and had some spare time. I took the Naval Academy exam with Congressmen Lee because I was interested in the Navy. I got a second alternate appointment, which didn't come through. The first principal got in, so I wrote it off and went to junior college in Martin County. I became very active in sea scouting and sailing around San Francisco Bay.

After a year in junior college, my mother moved south so I signed on at Cal Tech with the intent of being an aeronautical engineer. At age seventeen, that looked pretty

interesting. I spent a year at Cal Tech. They took a look at my record and said my math wasn't up to their standards, so I took math over again there. This turned out to be a pretty good thing. Then I received a telegram from the same congressman that said that I was on their list and was told that I was authorized to take the entrance exams again. I had made up my mind to be an aeronautical engineer, but I enjoyed taking exams at that point, so I thought I would test myself to see if I could do any better on the exams. I really took the exams with the spirit of a test for myself. Sure enough, it came in with another second alternate appointment. I wrote it off and said, “I will stick with this.”

About three or four months later, I got another telegram from the congressmen that said his principal and first alternate had failed and that this entitled me to an appointment if I wanted one. I took a preliminary physical exam on the West Coast. The doctor told me that I wouldn't qualify because I had an adherent scar from a childhood disease and a punctured eardrum. But, at that time, you had to go to the Naval Academy to take the official physical. My dad said, “Well, you have the appointment and you've never been there, so you ought to go see it.” So I set myself up to go to Annapolis, take the exam, and get rejected. I had arranged for a steamship trip from New York back to California just as an interesting thing to do.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you already had your passage back?

William M. Nicholson:

I was one step up on them. I was going to have a good trip out of it anyway but they took me in. That's how I got in the Navy, sort of by the back door. I enjoyed the Naval Academy; it was a lot of fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us something about your experiences at the Naval Academy. You had two years of college going in, which probably helped.

William M. Nicholson:

Well, it only really amounted to one year.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't count junior college as. . . .

William M. Nicholson:

Junior college was a growing experience and was very good for me because I was pretty young. It was helpful. It made the transition to college level work a lot easier.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you compare the instruction at the Naval Academy to the instruction at Cal Tech?

William M. Nicholson:

It was different. The Naval Academy was more formalized. It suited me. I was a member of the swimming team, not a very fast member, but a member. I did a lot of sailing and was part of the sailing team. I did those kinds of things, and I thought it was a very enjoyable experience. I had a pretty good first-class room. There's a lot of discussion about hazing and whether it is any good, but the three first classmen that I had to report to were great guys. One of them was my life-long friend; he died a couple of years ago. Hazing established some relationships with the Class of 1938 that are still very active. In fact, in some ways I'm closer to the Class of 1938 than I am to my own classmates because of the plebe experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's different from what a lot of people experienced.

William M. Nicholson:

My experience was very good. I had a very good relationship with them. I enjoyed the Naval Academy very much. I had one or two problems. I fell off the mast of the VAMARIE on a sailing race. I think it happened in 1940, the year before we graduated. I fractured my pelvis, broke some vertebrae, and spent three or four months in the hospital. That interrupted things, but I recovered from that all right.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did that affect your schoolwork?

William M. Nicholson:

Well, it didn't seem to very much. As you know, I graduated at the head of the class. Academic work was pretty easy for me. I didn't have to sweat it very much. I spent a little time helping my roommates. It was a format I enjoyed, it was easy for me, and I claim no particular credit for that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Being absent from class for that length time, did they allow you to make up work?

William M. Nicholson:

Well, fortunately, one month of my recovery was during summer vacation and I just didn't have a vacation. I didn't get a September leave, so I began school in the fall without missing a lot. I had people bring me work in the hospital and that was pretty easy. I really enjoyed the experience. It was fun. The most frustrating thing was that my eyes kept getting worse and, by first-class year, it was obvious that I was going to have trouble qualifying for a commission. Sure enough, I was rejected. I failed the physical on graduation along with twenty-two others. We called ourselves the “Twenty-Three Club,” and we became passed midshipmen. They came to us and said, “We recognize you've been studying, and we think that, given a little rest period, your eyes will improve. We will give you another exam.” Well, they didn't give us a rest period; they put us to teaching V-7.

The war was coming, the V-7 Reserves classes were coming in, and they put us to work teaching them. Marking papers and staying up all night to prepare classes--something you're very familiar with--is not really the easiest thing on the eyes. I think eleven of the guys did pass in the summer of 1941. They got commissions and the rest of us got discharged.

At that point, the war was building up, the Fleet needed officers, and the future looked a little uncertain. Acting as spokesman for the group, I went to Washington to see if there was some other avenue we could pursue. It turned out they were in need of Naval

construction people for the big build up that was going on. They had started a short course in Naval architecture at the postgraduate school.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, that went hand in hand with your engineering interest.

William M. Nicholson:

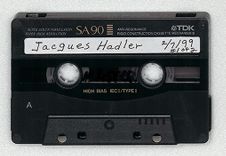

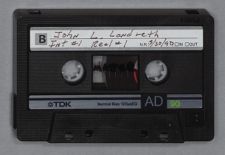

It happened to be something I was very much interested in. I talked to a lot of people in Washington and finally they agreed they needed us. They said they would put us in that class, but we would have to get a waiver because even the Reserve officers had to see 18/20. We finally got a “waiver of physical defect” from the Secretary of the Navy that allowed us to be sworn in as Reserve officers in the Construction Corps. That's what Jack Hadler and I did along with several other guys. We went through this short course in Naval architecture and finished it up just after the war started in December. We were ordered to various duty stations. Along with Jack and a couple of other guys, I was sent to Washington to the Bureau of Ships.

That was very interesting because I was an ensign and I don't think there were more then a handful of ensigns in Washington, nearly all the officers were gone. The war had started and anyone who had any qualifications was out. I remember being sent to a conference to represent the design division. I was an ensign, the next junior guy was a commander, and there was a whole pile of captains and admirals sitting around worrying about things. I picked a seat in the back and kept very quiet because, being fresh caught, I didn't know much about what was going on. It was a strange place to be as a junior officer because all the junior officers were at sea.

I was assigned to the preliminary design division. That was a great place. My first job was analyzing war damage. They had set up an organization specifically aimed at looking at what happened to the ships at Pearl Harbor and elsewhere. The goal was to

analyze damage to determine what design changes should or could be made to prevent damage and speed recovery from damage. I spent a couple of years traveling around, looking at damaged ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you find a lot of design that was really defective?

William M. Nicholson:

It was not so much the design that was defective. There were things like fire fighting; they had to do something to improve fire fighting.

One of the first jobs I got was a design problem not related to damage but to the fact that the 692 class destroyers just coming out had short legs. They couldn't handle the long distances in the Pacific. We decided to add sixteen feet to the middle of the ship. We didn't really cut them in two because they were on the way to being built, but we added sixteen feet and filled that with fuel. There were a lot of other things like bridge design that were happening as a result of wartime experience. It was a fascinating job.

Donald R. Lennon:

Particularly with older ships, you hear a lot about design modification. Do these modifications compromise the quality of design or improve it?

William M. Nicholson:

Every ship design is a compromise involving many different elements. For example, do you make the ship a nice place to live in or an easy place to work in? Either choice costs you weight and space.

Another interesting project involved the LSTs [landing craft]. I got involved in the landing craft design business. If you see early pictures of the LSTs, they had about twenty-four big fans on the deck--ventilators--to keep air circulating when they loaded the tanks. When they started the tank engines, the carbon dioxide would build up in the tank decks so we had to have a lot of air going through. They ran out of production capability for fans, and they weren't delivering enough fans for the ships; so the problem we got was how to

change the ventilation on the ships so we could use fewer or different fans. I got the job of running a test on a LST in Norfolk. We loaded it with tanks and tank crews and got medical attention for them. They were taking blood samples from all the tank crews, progressively decreasing the amount of ventilation so that we could find out what the lowest level of ventilation was that would keep everybody healthy, then rearranging the fans. It was an interesting test.

They were doing other things that were fascinating. The old ash cans that you see in movies--depth charges--look like garbage cans. They developed a new, faster-dropping depth charge than the ordnance was putting out. The question came up that if the ship is going five knots and drops this new charge, is it going to drop rapidly and go off under the stern? The older doctrine was that you had so much time because of this can dropping in the water and you could get away from it. But what should we do with these new faster dropping ones?

Lieutenant Commander Garner was killed in a testing in Chesapeake Bay in the same division I was in, and I got thrown in his place to run a test on the BELL, a new destroyer. The BELL was a brand new ship out of Charleston, and I took a crew from the Model Basin. I was still an ensign at that point. I took a crew of engineers down to instrument the ship--put strain gauges on the deck and do a variety of other things. My instructions were to take the ship out of Charleston and go consecutively slower and slower, dropping depth charges, until I damaged the ship. I had to find out where the “cut line” was. They were going to renew the instructions to the Fleet on how slow you could go. I'll never forget the skipper of the BELL. He was a senior commander with his brand new command.

Then here I come, an ensign out of Washington, with instructions to damage his ship. He didn't like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why didn't they use an old ship instead of a new one?

William M. Nicholson:

They were worried about the new ships. They were trying to find out exactly where we needed to change design or what we needed to do for shock damage.

Donald R. Lennon:

There weren't that many old destroyers around at this period?

William M. Nicholson:

No, they were all World War I ships and they were about to collapse. There were a lot of interesting things like that. I also got involved in improving transfers at sea. They were replenishing the Fleet at sea, and the techniques in use were not too good. You had to bring two ships alongside and carry stuff back and forth between them. Our problem was to determine how to improve that. I did lots of studying and traveling back and forth, trying to develop a conveyer system. We got one that worked, but only marginally. Finally, the burtoning system--free rigging with lines back and forth--was the eventual solution.

We did a lot of interesting projects like that, but it was frustrating. The war was going on and as junior officers we hated being stuck in Washington and regarded ourselves as trapped there. We all wanted to go out and fight the war. I tried getting into submarines and wrote letters to the chief, Admiral Cochran. An opportunity came up to go to MIT and I applied for it and got turned down. I applied for anything to get out of Washington. Finally, Cochran called me . . . this is interesting . . . as chief of the Bureau he took a real interest in us because he had been in preliminary design. He told me, “Look, there's no point in sending you to MIT to teach you to do something that you are already doing. That doesn't make any sense. We need people too much. But you stick with it and when the war is over, if you still want to go to MIT, we'll send you.” Well, I thought that was that. Here was the

guy in charge of all the shipbuilding in the country, and he was paying me some attention. I thought that was pretty good. So I finally succumbed. In 1944, I got out of Washington. My boss was moved to Mare Island, and I got him to ask for me. I got out of Washington and went to Mare Island. There was a dry dock there. It was kind of a frontline--repairing ships--and that was a lot more fun than pushing paper in Washington.

Donald R. Lennon:

Even when you were in Washington, were you doing those tests at Norfolk and around?

William M. Nicholson:

Oh, all over, it was fun. One of the nice things about that was that, unlike today, in a wartime environment we would be putting plans on the board in Washington, the design superintendent Admiral Farin, who was a commander in Norfolk, would come up and look at our plans, take them back on the boat to Norfolk that night, and we'd be doing that new design on the ship the next day. I mean things happened fast. You could modify a design and the next day it would be in the shop in Norfolk. It takes months or even years to do that now, but then things were really fast. We had an idea, put it down and “bing” it was out in the Fleet. So the work was not uninteresting, but it was just the idea that 'Those guys were fighting the war out there and here we were doing nothing!' It was a basic psychological problem.

Anyway, I was out in Mare Island when the war ended. I was still a Reserve officer, and I was seriously contemplating getting out. By that time, I was frustrated about my eye condition. I thought, I'll become an ophthalmologist or optometrist, my dad is an optometrist down in Southern California, and I'll join him and his business.

I was about to resign when I got a telephone call from Admiral Cochran, who was running all the shipbuilding in the country. He said, “If you want to go to MIT, we'll send

you in the next class.” Well that caused me to back up and reconsider getting out of the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he remembered that conversation?

William M. Nicholson:

Yes, and, needless to say, I was impressed. He was the top shipbuilder in the country, and he remembered who I was and called me. So I said, “Sure, I'll take it.” I made up my mind to stay with the Navy as a Reserve officer. I went to MIT and attended their graduate course in naval architecture. I finished in two years. At that point, I was intent on getting back into the shipbuilding business. I wanted to get into submarines. I worked toward that end, and we shortened the course up. The normal course was three years, but we had been doing naval architecture through the war, so I got a lot of credit for work done. I got it in two years.

Donald R. Lennon:

What appealed to you about submarine design?

William M. Nicholson:

I just thought it was an interesting design problem. Also, it was close to Portsmouth, and I thought I would be sent up there, but the powers that be decided that I should go to sea. That was really a good decision. We were very close to war and I had had no sea duty.

I got orders to an aircraft carrier, the PHILIPPINE SEA. The PHILIPPINE SEA had a good tour. We went to the Mediterranean in 1948 when they were still firing at each other up in the hills in Greece. It was pretty active. I had a great tour throughout the Mediterranean in the wintertime. I managed to go skiing in Cyprus, of all places, when the ship put in there. The commissioner of the Jewish camps was staging the Jews into Cyprus before they went into Israel. The commissioner was Sir Godfrey Collins. I'll never forget him. He was seventy-two years old, and I was half his age. He wanted somebody to go skiing with him. They picked me and sent an aide down to find me because they knew I

was interested in going skiing. I went with him and, at the end of two days, he was beating me to the top of the mountain. That was a unique experience. He went back to England and got married for the first time at age seventy-three. He was quite a character. A lot of interesting things like that happened.

I spent two years on the ship as a damage control officer and was about to fleet up to engineer when I got ordered to the Boston Navy Yard. They put me to work in the dry docks. I was a dry-docking officer for repairs and a ship superintendent. We were converting destroyers to DDEs, escort ships, and that was one of the outstanding jobs there.

Then they moved me from the waterfront to take over the design division in the Boston shipyard; I became the design superintendent. That was fascinating. Electronics were just coming in and becoming a bigger and bigger part of the ship-design problem, and one of the things I was doing in the design division was building up the electronic group and separating it from the rest of the design division. Of course, the design division in a shipyard does a different thing than it does in preliminary design in Washington. The division in the shipyard does the actual planning for brackets here and there, wiring for the circuits, and things like that. Preliminary design in Washington looks at the whole ship and plans future ships, so there is a big difference. It was a good experience to run that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Being at sea aboard ship gave you a good new perspective on ship design, too.

William M. Nicholson:

While I was a student at MIT in 1947, I had been ordered to the OREGON CITY, a cruiser, where I spent three months. That's a separate story, but it's interesting because we were taking the first group of ROTC midshipmen on cruise. We had students from Notre Dame and Ohio State and several other schools on a cruiser out in the Caribbean. I was put in charge of that because I was then a lieutenant commander. I was the ship representative

in the engineering department on the ship, standing watches and also responsible for the students. That was an interesting experience.

I remember the senior academician on aboard was from Ohio State. He struck up a great relationship with Captain Macintosh. They'd go ashore, get drunk, and have a big night. We would have to help them onboard the next morning. He didn't want to go home. He was supposed to go home, but one of the duties that the captain assigned the navigator was to make sure that he missed his plane in Trinidad, because then he would miss the next plane. So he stayed on the ship and missed the next plane. We found out later from some of the other guys sitting on the boat that his wife had not allowed a drop of liquor in the house for twenty years and so he was making up for lost time. They thought he was being a terrible example for those young midshipmen.

Donald R. Lennon:

And he had been denied for twenty years.

William M. Nicholson:

But there are interesting things like that that happened. Anyway, where was I, Boston?

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

William M. Nicholson:

I got a call in 1949 from a friend on Captain Rickover's staff. He wanted me to join the nuclear program. That was just coming along. I was in Boston and had a fairly good academic record. He said, “Look, we need more officers in the nuclear program. If you will sign on, we will send you over to the one-year short course at MIT, and you can become one of the nuclear officers.” I thought this was a great opportunity and that maybe I ought to do it. I talked to my boss, Captain Cronin, who was a planning officer. I said, “Here I am in the design division, and we are reorganizing it, and I don't want to leave, but what do you think about this offer?” He spent about half an hour or so talking to me. It turned out he

had relieved Rickover on three different jobs: in the electrical desk in the Bureau, in the ship, and in the Reserve Fleet. He didn't tell me not to do it, but he described to me the conditions that he found when he relieved Rickover in each case. I decided, “No, I don't want to work for that guy.”

Donald R. Lennon:

I've always been told that he was a very difficult person to deal with.

William M. Nicholson:

Well, he did strange things with his staff. He was very unkind to his staff. Nobody did anything but Rickover, and he drove nearly every officer out of the Navy that worked for him, and he had wonderful people, some of the best people in the system. A couple of my classmates left. The press talked about how he fought his way, but he had his choice of all the best engineers in the whole system, and he drove most of them out. Anyway, I looked at this record and I said, “I'm going to stay here. He's a captain, he has an awful record, he will probably be gone in a couple of years, and I'll have other opportunities to get into the nuclear program.” This was about 1949. When I retired from the Navy, he was still on active duty, so that shows how good my judgment was.

Donald R. Lennon:

It would have been terrible working for him.

William M. Nicholson:

I worked with him not for him. Later on, when I took over the Deep Submergence Program, I was responsible for one of the ships he was responsible for. We had an interlocking problem. That worked all right, but I don't think working for him would have been much fun.

I turned it down and stayed in Boston and, in 1950, they were looking for an assistant to the head of the Mechanical Engineering Program in the Postgraduate School, which had just moved out to Monterey, California. They picked me for that. I got a set of orders that sent me out to Monterey. That was pretty choice duty, but it was not really Fleet

duty. It was academic work, but I enjoyed it. They put me in charge of a lot of curricula around the country, and I had students in colleges all over the country. I got to go see them and work on their curricula and do a little bit of teaching. It was a great job. The only problem was that I was having domestic problems at that point. My wife was having serious problems, and that complicated life tremendously. I finished that job and felt out of the mainstream. Academic work is not really at the top of the Navy list, but it was a good job.

I was then ordered back to Washington. That was fortunate, because I got some psychiatric help for my wife there and that helped a little bit. I found myself working for my first classman, the guy who I had reported to as a plebe.

Donald R. Lennon:

One of the Class of 1938.

William M. Nicholson:

He was the head of the minesweeping group, and I became his assistant. That was fun. We were solving an insoluble problem really, but it gave us a lot of innovative experimental . . . I seem somehow invariably to get involved with experimental things, new things. We were trying to find some way of sweeping pressure mines in particular because nobody had figured that out. I had a project to develop a ship, an unsinkable floating platform that, when towed through a minefield, would create the pressure signature of a ship. If you blew up the mine, you wouldn't sink the ship, but you would get rid of the mine.

The job was to see what you could do experimentally to prove this. We took an old Liberty ship and filled the hull with Styrofoam so it wouldn't sink. We got four spare engines, surplus jet engines off a Constellation airplane, mounted those engines on forty millimeter rotating platforms, and drove the ship with these. We had four of them and could

drive the ship at about eight knots. We named her DUMBO. They used up a lot of fuel. We took it down to Panama City and ran it through the minefields for pressure signatures. And it worked. It actually worked well enough that we got it into a shipbuilding program to actually build some, instead of this experimental platform. But it fell out, the pressure and juggling money back and forth, and they never built one. The last phase of that was to blow mines off under it in the Chesapeake Bay. We proved that it would work, but it was expensive in terms of fuel and the priority system dropped it out the bottom. It was fun, however.

Another project they had was a thing called XMAP. They built a three-hundred- foot long steel cylinder with steel eleven inches thick. They trained more welders in Philadelphia then they could handle. I think they ran the best welding school in the country. This thing was all welded together with steel. It was, in theory, strong enough to withstand mine explosions. You could run it over and it wouldn't break up, but the problem was that they had to tow it with something, and I got the job of taking it from Philadelphia down to Panama City and running the trials on it. Those are the kinds of jobs I had, all doing different things.

The idea was to learn how to do it. We hired a tug from New York; most Navy minesweeper captains were not towboat captains. So we hired a Moran Towboat, Marion Moran, with their most senior skipper to pick it up in Philadelphia and tow it to Panama City and then run trials over the range in Panama City. That was a fun job. We towed it down in the wintertime and I rode the ship down and stayed with the captain, Ira George, for several weeks while he was towing in and out. We had some hair-raising experiences. If you can imagine, this thing was like an arrow. It was three hundred feet long, had a fin on the back,

and weighed three thousand tons. When you got it going in the water, it was going to go straight. It was geared to, it had no rudder control, and it was towed by a towboat. If it ever got going with a five-hundred-ton towboat, it would take charge and the minesweeper skippers were scared of it. So our job was to develop towing techniques and write instructions so that it could be handled.

It was fascinating business to do that. I remember one particular conversation I had with Captain George. When we finally got to the point that we had a minesweeper come and pick it up to try what we were doing, I invited George to go with us to see what the Navy did. We were going out that little narrow entrance to Panama City with this thing in tow and, of course, they had the captain and the officer of the deck and the junior officer of the deck and the quartermaster and guys singing out bearings from all the corners. I couldn't find Ira George around anywhere. He and I had been doing this with just two of us on the bridge for weeks, and he ran the whole ship. He'd run over to the engine controls . . . and work the whole thing. I finally found him sitting back by the flag bags and said, “What's the matter Ira? What's going on?” He said, “Jesus Christ, I don't see how the Navy ever gets anywhere with all those people making all that noise.” He had been running tugboats in New York City all his life with just him on the bridge working the controls. He didn't understand how the Navy did this. Anyway, that was an interesting job.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm ignorant about how minesweeping works. If you are pulling this behind the minesweeper, it is going to be in the wake of the minesweeper, so it seems to me that the minesweeper would make contact with the mines before . . . ?

William M. Nicholson:

But the minesweeper itself is a small boat. It doesn't leave a big signature in the water. The idea was that you bring through something that's the size of a freighter, and it

generates the same physical signature in the water, the same pressure changes, and that happens of course with the tug boat up here somewhere so they would blow up behind it. It was a whole series of interesting projects. That lasted for a couple of years.

Then I was shifted over to contract design. The mine sweeping section is one section and contract design is a separate division of the bureau. I was moved over there as a project officer. I had a lot of interesting jobs there. One of the most interesting was the development of hydrofoils. I was given the job of developing the contract plans for the first Navy hydrofoils. They had built an experimental hydrofoil, a thirty-six-foot Chriscraft equipped with fully submerged foil, under Gibbs and Cox up in New York. They had been running this for a long time to see if this could be controlled electronically.

I don't know how familiar you are with hydrofoils, but they have been around since 1880, I think. An outfit in Italy had built one that had surface-piercing foils. The foils go in the water this way. As you speed up, they lift and eventually wind up just a little bit in the water. You start out there in the water and lift the hull out of the water and then you are running on these airfoils under the water. It was a rough ride, and our goal was to develop a platform that would eliminate the roughness and enable us to do some good work. So the intent, and what they had done with the SEA LEGS, the name of the little Gibbs and Cox boat, was to have an electronic sensor that measured the height above water and transferred it hydraulically into controlling flaps on the foil. The foil was totally submerged, none of this surface piercing stuff, but just down with an airplane wing under the water. We controlled this with electronic signals from a height sensor on the bow and it worked. This thirty-six-foot boat worked pretty well.

The intent was to bring that down to Washington from New York and run some trials in the Potomac and demonstrate to the chief of Naval Operations and others that this was a viable concept. Once again, I got another lucky assignment. I got the job of bringing it down from New York, which was fun. I went up and went through a lot of gyrations to get that. We had the normal problems with experimental things, we broke things and had to fix them and got down and ran the trials and got it approved. It actually got built.

Donald R. Lennon:

The plans and the development of that probably had later implications for the commercial hydrofoil they use now.

William M. Nicholson:

I will tell you what happened. I finished the plans and was ordered out to Bremerton. Boeing was interested in bidding on this craft as an airplane; this is an aircraft- related sort of thing. I was at the shipyard in Bremerton as management engineer and comptroller, and I was asked by one of the Boeing engineers to come over and brief their board of directors. One of the Boeing engineers had been looking at this boat. He had met me in Washington and knew I would be coming out there. I actually took movies that I had made on the trip from New York to Washington, eight-millimeter movies of the performance of this boat. I took them over and briefed the board of directors on what this concept would do and how it would work.

They bid the job in and set up a whole separate division in the Boeing Company. I'll never forget the time they asked me to come over and talk to them. I walked in the enormous building they build airplanes in, and the top floor had something like eleven hundred engineers on drawing tables all over the place. Way over in the corner were eleven engineers who were set aside by them to do this new technique, hydrofoil, that they were going to build for the Navy. I said, “What do you use all those guys for?” They said, “We

have a thing called the PERT system. It is a managing system that the Air Force requires us to run in order to detail the building of the airplanes.” I said, “Do you need all those guys?” They said, “No, we don't run the plant that way. We just do that because the Air Force requires it.” They had all these guys doing paperwork, shuffling paper, and they actually ran the plant with another system, but they had this reporting system required by the Air Force. I thought that was pretty interesting.

This small group of people also did another interesting thing. They got a shipyard in Takoma to build the ship under the supervision of Boeing, and they actually did a great job. Out of that came the subsurface hydrofoils that you see running from Hong Kong to Macau today. They were Boeing built. The Navy built, I think, three of them and ran them as patrol craft for a number of years. They functioned very well and they did something different than normal: they gave Boeing a contract to maintain them and I kept track of it remotely. They did quite well. I guess the force makeup didn't require ships with that capability so they sort of dropped out the bottom like the minesweeper.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that the same principle as, for example, the high-speed ferries that cross the Irish Sea?

William M. Nicholson:

I think those are hovercraft. I think they ride on a cushion of air and that's a whole different thing. They blow air down to the skirt around it and build air pressure up and lift it off and it rides on an air bubble. Those, I think, are hovercraft, but there are several different ways to go and they're all fascinating.

Donald R. Lennon:

In ship design, probably the greatest innovation or technological advancement that changed ship design more then anything else was the advent of the computer, was it not?

William M. Nicholson:

Yes, electronics generally. That's why, when I was in Boston, I was building an electronic section. Out in Bremerton, I was assigned a job as Comptroller/Management Engineer; I was given the job of introducing tape-controlled computers. The shipyard was running on card systems in 1959 when I went out there. I had the job of converting it from the card system over to the IBM-650 tape-driven system. The yards, in general, were beginning that conversion. That was another fascinating job.

I really enjoyed Bremerton. That was a great place to be with a couple of small kids. I had, by that time, divorced my wife. I had custody of the two kids and it was great. I could take them skiing. It was a real opportunity, very fortunate for me. Then after I had been in Bremerton awhile, I had a telephone call from the chief of the Bureau. He said, “Do you want to go to MIT as professor of Naval construction?” I had to think about that a little bit. I told him, “That is not really a good career pattern for me, because I'm getting to be an academic type. You know, Monterey is a post-graduate school . . . and teaching at MIT . . . I'm not in the front line.” But I said, “Sure.” It was a great job, and it was an honor to be selected for it because it had always been a real pre-selection type thing. They only picked the top people for that. I said, “Well, if that's where you want me, that's where I'll go.”

The Navy had this course up there, now called course 13A, which is a postgraduate course. It picks people after they have done their college work. Normally, after two years at sea, they select a group of well qualified officers who go up there and spend two to three years studying Naval architecture, marine engineering, and other things. It is a very broad program. They send about twenty a year. Along with that, there are officers from foreign navies, and I had officers from Brazil, Greece, Canada, and Philippine navies who came to take this postgraduate course at MIT. The Navy had an officer responsible for the sixty to

eighty officers who were up there studying. The officer is a senior engineer, and he is in charge of them, but he is also a member of the faculty. I was actually paid by MIT, not very much, but I was given a small amount because I served on selection committees and doctoral committees for the department and did other duties . . . registration officer, etc. I functioned as a professor with a full appointment from MIT, really on detached duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are civilians allowed to sign up for these courses?

William M. Nicholson:

Yes. They have a rather broad course with a lot of civilians taking it, but my responsibility was for a particular program of Naval officers who were studying military warship design and construction problems. I regulated their curriculum, decided which courses they were going to take, and worked out with them. They all take different courses. Some emphasize structure, some emphasize engineering, some emphasize electronics, and some emphasize nuclear power. All of the Naval officers report to the officer in charge. That was really a great job. I became a member of the faculty, attended all the faculty meetings, and worked on the normal college problems. I was also a member of the selection board that meets annually in Washington to pick, out of the applicants, which ones were going to go up there. I enjoyed that, but I don't think I ever worked harder in my life. I taught five courses. I had to write the courses myself and, unlike most of the professors, I didn't have any assistants. I had to do all the grading and the whole bit--paper review, etc. I burned more midnight oil in that three years then I ever did anywhere else. But it was fun.

I finished that in about 1965, and I was ordered back down to head up the ship design division in Washington in the Bureau of Ships. Actually, I was responsible for preliminary design, contract design, and all the type desk engineering. I got there in 1965 and almost the first thing that happened was that I called in all the old civilian engineers that

I had worked with before and said, “Here I am fresh caught from MIT. I've been off the circuit. What are my problems?” Ralph Lacy said, “Well, you have got a problem. We have a thing called the NR1, which Admiral Rickover has started, and if it goes the way it is designed it will sink and it won't come back up.” I said, “Well that sounds like a pretty serious problem.”

The way Rickover operated was that he had complete control of machinery, and all the hull design was done in contract design. This separated control over sections of the ship; the interface was very sharp and he insisted on keeping that interface sharp.

We had another interesting problem. We had a call from Fore River Shipyard, and there had been a disconnect on the LONG BEACH, which was the first nuclear cruiser. The main wire-ways (the main wire-ways occupy probably half this room with all the wires going back forth) on Rickover's plan were on the fourth platform deck, and the main wire-ways for the rest of the ship in the contract plans were one deck removed. They reached the bulkhead but they didn't match. That was a result of his absolute refusal to let our engineers talk to his engineers. The contract plans had actually been done with one deck discrepancy between these main wire-ways. Things like that were happening.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did one know that the other engineer was putting wiring on the other deck?

William M. Nicholson:

No. Rickover would not allow our guys to talk to his guys. You had to go through him. It was a wild situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did he remain in charge of that program?

William M. Nicholson:

He had absolute control of Congress. The nuclear committees in Congress were under his total control; he had them. Many people will tell you this: “You could get Rickover and a group of people together and talk for hours about what happened, but his key

to success was that he had absolute control over Congress.” He was smart. He set himself up as the nuclear regulator for safety, and under that “hat” he could control everybody, and Congress backed him 100 percent. Anyway, this was a problem I encountered right off. We diplomatically worked around that and finally got working with the shipyard and got that straightened out.

A year later, after being there a year, I got picked out and assigned to the Deep Submergence Program. The NR1 was in the Deep Submergence Program, which was a separate program of research and development. I suddenly found myself totally responsible for the completion of the NR1, which was then under construction. That's how I came to work with Rickover for three years.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm curious about that other problem. Did the Navy engineers have to redesign, move their wiring?

William M. Nicholson:

At that point, all the plans were up in Fore Rivers. Their engineers got together with our guys and figured out how to do it.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the project was no longer controlled by Rickover?

William M. Nicholson:

He had total control over his engineering spaces, but when it came to the bulkhead where you had to bring things through and make sure they matched, the adjustments were made at Fore River because they had the job. They were building the ship and developing the building plans at that point. That was a matter of adjusting lines and getting it done. It was kind of an emotional problem at the time, not inconsequential.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are there any details on the NR1 project that you worked on with Rickover that you want to be more specific about?

William M. Nicholson:

There were a lot of troublesome things. He made an agreement with my predecessor, John Craven, that NO information would be released except by him. This frustrated the press and this didn't come out till later. I'm going consecutively. The problem when I was in the design division was that the completion of the plans for the EISENHOWER, the carrier, and for the NR1 were coming along. I didn't pay too much attention; they got that straightened out. Our engineers adjusted the framing and got its buoyancy adjusted and things like that.

Then I was supposed to go to the model basin. I actually had gone out to the model basin to be commanding officer of the model basin and gone through the PR. They were about to announce it when the director of the model basin, Captain Ela out of 1938 and a friend of mine from Bremerton, decided to retire. He didn't get selected for flag officer and said, “I'm going to retire.” When he retired, he had been tagged for the Deep Submergence Program and a decision was made, not with my knowledge, that I would become the director of the Deep Submergence Program. I had only been in the design division for a year at that point.

Deep Submergence was a program that grew out of the THRESHER disaster. It was a totally R & D-funded program, on how do we go deeper and get divers deeper. It was a five-point program. Number one, how do you get divers below two hundred feet, the goal was six hundred feet? Number two, complete the NR1. Number three, how do we do deep ocean salvage and recovery? Number four, we had the man and the sea program, and there were two or three small things in there, like how you can improve submarine escapes, and anything to do with going deeper into the ocean. It was unrelated to Fleet funding, which became a real problem for us later. I became director of that right out of the design division.

I picked up the NR1 completion. One of the interesting things about that was that Rickover had a deal signed in blood with everybody that he would be the only one to make any public announcements on this. It was his baby, he started it, and it has an interesting history, which is covered by a doctoral thesis that one of my guys wrote later. (Robert Herold — “The Politics of Decision Making in the Defense Establishment; A Case Study.” George Washington University 1969.) He went to his buddies in Congress and told them, “Hey, I have thirty million dollars that's loose in the Polaris program.” (Polaris had a management fund philosophy. I don't know whether you've seen that. The money in Polaris was very wisely setup by Admiral Burke so that the Polaris director had total control of the money. He didn't have to consider whether it was green money, blue money, pink money, maintenance money, or whatnot. He had a pot full of money called a “management fund” and he could do anything he wanted with that money. That's one of the key reasons why Polaris moved rapidly.)

Rickover said, “There's thirty million dollars loose in there, and they don't need it.” He also told Congress, “I can build this little experimental ship for thirty million dollars, without coming back to you for more money.” Congress thought that was great. So Rickover arranged for the ship to be built and the Chief of Naval Operations heard about this by reading it in the paper. He didn't even know that this contract had been made. That was the way Rickover operated. He actually had it under construction at Electric Boat before the CNO knew about it. He said thirty million. I had to preside over the escalation in cost from thirty million to somewhere around ninety-six million. We were never able to identify Rickover's cost because he would not allow the controllers, the examiners, into his office. He'd say, “You guys wouldn't understand what you're talking about anyway. Out!” Now, I

couldn't keep them out. I spent months arguing money with them, but Rickover stalled them. He had that kind of control.

Anyway, I then had the job of going back to Congress for escalation in money. Rickover had never gone back. He had made a deal with them at thirty million, and he never owned up to the fact that he was, in large part, responsible for the growth in cost. That was my pigeon. So that program was really fun. It was the Sea Lab Program, which got lots of publicity. I enjoyed that. I got to do a lot of diving. I got to know a lot of interesting people. I got to know Cousteau, and Scott Carpenter worked for me. I got him back from the Air Force, from the NASA program, when they wouldn't fly him anymore. I called him up and said, “Do you want to come back to the Navy?” He came back and worked for me. We had real fun doing that. It was a good program.

In the Sea Lab Program, underwater living, our objective was to get to six hundred feet so that we could work at six hundred feet. We got there by a series of tests, deep-diving facilities, sea experience, and whatnot. The actual underwater living was the thing that got publicity, but that was not our goal. Unfortunately, we lost a diver on the first dive. It was a case of “for want of a nail, a shoe was lost.” You know that story. The habitat was built in a San Francisco shipyard. When they put it together, they did not do a good job with the seals. When we tested it, we tested it with air because we were running on a very tight budget. I think we had five million dollars a year for that program, and NASA was running at five billion a year then. We were small peanuts. When we tested it, we put it in the dry dock, flooded it, and pressurized it. Everything worked, but we were using air and that was a mistake. When we put it down off San Clemente Island, it had serious leakage. We pressurized it with helium, which was necessary for a six-hundred-foot operation. The

helium lost through those pressure fittings was so great that we couldn't keep up with it. The divers figured that they could get inside and seal it from the inside. We made one attempt unsuccessfully. On the second attempt, one of the divers died. It was a mistake, as near as we could find out, in that his carbon dioxide removal canister was not properly loaded.

Afterwards, we tracked it, and as near as we could figure out his breathing canister was not properly loaded and he went into the water without the ability to extract carbon dioxide and died from that. That happened and I had a whole planeload of reporters coming out from Los Angeles to see the operation on the first day. I had to explain to them that we had just lost a diver. That was a low point in my career, but we did get to six hundred feet.

Out of that came another program in the black, which has been released since. The program was to equip a submarine so that divers could exit the submarine and work outside. Eventually, that worked into project Ivy Bells, which has been released several different ways. We converted the HALIBUT, which was a submarine originally intended to launch missiles. We had a lot of space. We put a deep-search system inside, fitted it out, trained the divers, and eventually worked with the CIA. Eventually, they went up in the Sea of Okhotsk and planted listening devices on the Russian cables that ran across there to Moscow. We were able to record and tune in on Russian correspondence.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is the late sixties?

William M. Nicholson:

Yes, and when the Korean 007 was shot down, that's how they knew. They had been in there with the submarine, planted this device, and recovered the messages. They listened to the Russians talking to each other and that's how the President knew the facts of the case. My part of it was modifying the submarine, training the divers, and getting it equipped to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

How were you able to design it so that they could exit?

William M. Nicholson:

We built a high-pressure facility for decompression and everything in the SEA WOLF, cut a hole in the bottom, and built hatches so they could pressurize and go out the bottom of the submarine. There were some neat problems with that. For instance, you had to arrange the submarine so that it could be anchored. The submarine had to be steady when they went out, something submarines had never done. We put anchors in and went through a series of problems. The first few times we did it, the wires on the cable kept breaking. We had to make special cable for the anchor so it wouldn't break.

Then we got involved, of course, a little bit in the GLOMAR EXPLORER, the recovery of the Russian submarine north of Hawaii, the one that was on the bottom. That has also been written up, but we were going to get that. We were involved because part of the Deep Submergence Program was deep salvage, which that was. We had several meetings on how to do that. They finally took that away from deep submergence and set it up totally under the CIA because they could control the funding and keep it black, which they felt we couldn't do. That probably was a good decision. Some of the techniques that were developed were our business.

We worked on submarine escape but they never did fund that to be fitted into the submarines. That was the nature of the things that we were doing. Then, in 1971, I retired. When I was not selected for flag rank, I decided I would stay one more year to see the completion of the NR1 and finish up some programs. Then I bailed out.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had a fascinating career.

William M. Nicholson:

It was fun. I can't complain. It was unusual because, as I think I have outlined to you, I almost invariably got mixed up in new development, in experimental work. That did

not necessarily put me in the front line operations, but it eventually fed into a lot of very effective systems.

Donald R. Lennon:

Actually, I think it was much more interesting and exciting then if you had been a Seal.

William M. Nicholson:

I had a great time. After I decided I would retire, my wife and I took off with our skies and skied around Europe, a little blow-off period for a couple of months. We had a great time. Then we skied our way across the U.S.

At that point I had to decide what I was going to do. I was invited to join Bell Air Craft because they had an air cushion vehicle and new development going on. I thought about that. I also had written Dr. White a letter when they had formed NOAA. I had written him a letter saying, “It is obvious that the Navy is going to drop the ball on deep ocean development. It has gotten to the bottom of the list, funding is light, and the Navy is not going to carry on with this development. This would appear to fit within the goals of NOAA as an ocean atmospheric agency and something you should pick up in your new organization.” I guess, partly as a result of that letter, I got invited to become the associate director of the National Ocean Survey. That was my next move, over to National Ocean Survey. I spent ten years there. We were primarily working on improving the surveying capability for ocean surveying, using acoustic techniques that I had been working with in the Navy and equipping the NOAA fleet for more efficient work.

The most interesting thing I did there was that I became the head of a mission to Japan called the United States Japan Marine Facilities Panel. That had me going to Japan every other year and inviting the Japanese over here on an informal basis to look at what marine operations and developments were going on. That was really fun. I did that for ten

years, and then I had had enough with the bureaucracy. They were reorganizing NOAA again, and it looked like the part that I had was falling out the bottom, so I decided that it was a good time to quit. I retired in 1981 and got a boat and took my wife and went off to the Caribbean. I had a great time doing that. So that is it in a nutshell.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any last thoughts or observations concerning your work with the Deep Submergence Program? Anecdotes or particular details?

William M. Nicholson:

I have some anecdotes. Cousteau stayed at our house one time. We had signed his son; he was going to be a member of one of the teams. He's a very competent young man. Cousteau stayed in our house, and I managed to drop him out of his bed in the middle of the night. In the course of many moves, I had lost some of the fittings for the bed and had put some bolts in the bottom. We heard this loud crash in the middle of the night. We went in, and he was on the floor.

I did things like arrange for him to have lunch with the Secretary of the Navy and things like that, to help out. It was fun. I met a lot of good people. I got to know Buzz Aldren from the space program pretty well. I became a member of a group . . . I didn't mention this while talking to you . . . that did the tech-type program while I was still in deep submergence. A group of industrial people got together and formed an organization called the Sea Space Symposium. It's a non-profit group that's interested in ocean-space development. They meet once or twice a year, usually somewhere where we can go diving and have an informal environment. It's made up primarily of business executives and senior executives of the Navy and government. I've been Buzz Aldren's diving companion for several years on these expeditions. That has been a very interesting group.

After I got out of the Navy, I became an active member of the Marine Board, the Academy of Engineering, and chaired several studies for them on arctic drilling and on submersible safety. I was vice chairmen of that for one year. That is an interesting group made up of engineers from academies all over the country. They pick up problems given to them by federal agencies. For example, the submarine-safety thing was given to them by the Coast Guard. They were asked to make a study to analyze the safety of the passenger submersibles that have been going out. I chaired that. That was my committee. I traveled with them. We studied the submersibles and gave the Coast Guard a report on them.

The Marine Board is a very interesting group. They function under the Academy of Engineering and primarily pick up problems that other federal agencies have. One study was to look at the NOAA fleet and see what they should do about that. One was a study of drilling in the Arctic. Another one was to look at the possibility of deep core drilling, using the GLOMAR EXPLORER, which was then laid up. So I was involved in a lot of things along with this Japanese thing. I had a whole spectrum of interesting things happen. I really can't complain. It has been fascinating. The Deep Submergence Program had the widest variety of interest in it, in modifying submarines and things like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have a reference here and I may have taken it down wrong, but a reference to swimmer-propelled submarines?

William M. Nicholson:

Oh yes, we had that too. I did that under the mine business. I used to have to go down to St. Thomas in the wintertime. We were trying to build a small submersible. You put two swimmers inside. It's really for underwater demolition teamwork. You get inside and, at that time, you pedaled it like a bicycle.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sounds like a nineteenth century experiment.

William M. Nicholson:

You lay down inside it with an aqualung on, a breathing apparatus, and you pedal it through the water. It was a means of getting the divers into the deep underwater. The question was how to build it and what kind of machines you should build. They have built some very sophisticated ones since I was involved. When I was down there (mid-50s), we were testing the ones that were swimmer propelled. You got in and pedaled it like a bicycle and lay down under water. You could run particular tracks and see how long it would take and what the most efficient way to do it was and ask what changes could be made.

Donald R. Lennon:

And it was a successful program?

William M. Nicholson:

It was successful in that one thing led to another and now they have very effective ones that run on batteries and you don't have to use the swimmer-propelled part, which is tough. I did that and it is hard. You could do it, but it was not effective.

Donald R. Lennon:

Didn't inventors experiment with that during the nineteenth century?

William M. Nicholson:

Yes, there's a long background. In fact the first submarine ones, in the Civil War, were pedaled by guys running some sort of a bicycle system in a propeller. It's a difficult way to go. They now have competitions among college students to see who can build the best and most effective one. But they have gone well beyond that now. It was a pioneering effort when I was involved. It was fun. I got to leave Washington and go down to St. Thomas for a couple weeks on test runs with the underwater demolition teams.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was free flooding part of that?

William M. Nicholson:

Oh yes, you wore an aqua-lung. You got in the thing and submerged it, pulled the hatch down, and you were in the water, working in the water. That is one approach to it. I would come back to Washington from a couple weeks down there and everybody would be envious of me. Everybody accused me of all sorts of manipulation, but it was legitimate.

Donald R. Lennon:

So Rickover was not the only one who could manipulate.

William M. Nicholson:

I have an endless series of little stories, but they're inconsequential. It was a developing time and I guess I was fortunate to be stuck in the developmental side of it because everything was brand new and different. It seems like I never got two problems quite the same. So that's pretty much it, unless you think of something else.

One other interesting job I had was converting the DEs, which we had built during the war, to troop transports, APDs. That was back in World War II time. They had converted some of the old four-pipe destroyers to carry underwater demolition teams. Those ships were about to fall apart, so the question was what we could do to make them better. The DEs were in production. They had them coming off the line all over the country. So we picked the fastest, best-powered group. They had enough stability that we could put additional deckhouse on, put living quarters on, and put some landing craft on them, and convert them to APDs. The first one that went out on trials keeled over about thirty degrees and everybody was scared to death. They stopped them from going to sea. We found out afterward that we had four LCVPs up on davit on that upper deck. I used the weights that the small-boat people had given me, but between the time we did the plan and the time we put the boats on, the weight of the individual LCVPs had grown about three tons a piece. There were twelve tons up at the stack level. That caused a big furor. We solved the problem by shifting to lighter boats from the upper level.

We ran into all kinds of things like that. I'm sure if we sat here and talked long enough I would think of some more of them. There was a long chain of things like that I got involved in, all fun. We all look back and think about what we could have done differently, but I can't think of too many things that would have changed anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

The modern Naval vessel, through all of these experimental and developmental changes, is rather drastically different from what you were using when you entered the Naval Academy.

William M. Nicholson:

Oh yes, there's no relation to them.

Another interesting job I had was that when I was on the PHILIPPINE SEA I discovered that the foam system, which we had installed at great expense in all the aircraft carriers for foam fire fighting, wouldn't work. We had a crash and had to put the fire out on the flight deck and got no foam out at all. Nobody had tried this before. As a matter of economy, they wouldn't let you use the stuff, you had to buy it and stock it. We got no foam when we tried to put out that fire! So I ran a long series of tests to demonstrate that the system would not work. The original tests for the system--for the piping--that we had set up in Norfolk to put out fires, using a foam proportioner, had worked like a charm. However, when it went into the ship, the pumps were down in the lower level, and the pipes had a million turns in them getting up to the flight deck sixty feet or so, and the pressure loss was so great that the foam proportioner wouldn't work. So they had to redo that. I just happened to be there and be the guy who tried to put out a fire and it didn't work. Having come from the bureau, I knew all the buttons to push back there and went back and convinced them, eventually. I finally got them all up to Narragansett Bay and ran tests alongside the dock trying to make foam. It would make it on the hangar deck, but it would not make it on the flight deck. In the course of that, we pumped a lot of foam stuff over the side and it drifted down the bay and the next thing we knew we had the state environmental people on us. Some woman had seen that and had said the Navy was pumping oil in the bay and killing all

the seagulls. Actually it was not harmful; it was foam for fire fighting. We had a million interesting things like that.

I guess the one regret I have of all of them was the loss of the diver at the Sea Lab, because that was a good program and I think it would have worked. It has since grown into all the diving in the North Sea all around the world. The development of oil fields . . . the technique that we developed and proved is the basis for the diving industry all over the world.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was wondering if that Sea Lab project went beyond the experiments you ran?

William M. Nicholson:

We had hundreds of divers doing trials at different depths and under pressure; developing techniques for what air mixtures, what helium mixtures, what nitrogen percentages; and seeing how long it takes you to get back. That was all done with Navy divers, most of them under my program. The techniques were well established, the books written, and it opened the door to diving below two hundred feet. All these guys who go down in “saturation.” Almost always, rigs at sea on oil platforms have saturation divers to go down and fix things. In fact, I have a son who is on one down in Mexico now, and he became a diver. He has been all over the world.

That's been done and it's been taken on beyond, when the Navy quit doing it. The Sea Lab Program got the Navy to where it wanted to go. We finished that. We lost the diver, and we lost public relations, which was a big problem, because the press had made a big deal about it. If you remember, back then there were all kinds of articles: “Man is Going to Live Under the Sea,” “ We are Going to Build Cities Under the Sea.” It was a pile of crap and we said so at the time. The deep ocean is dangerous; it's dark, it's cold, and it's miserable. You go down there if you have to, to work. You get below two or three hundred

feet and it's absolutely black. You can't see a damn thing. People want to go to the beach and sit in the sun. Nobody's going to go down there and live voluntarily.

Donald R. Lennon:

There wouldn't be any point in it.

William M. Nicholson:

Yes, no point in it, but there was a tremendous amount of publicity. Right now there's a lot of publicity that we are going to establish colonies on Mars. That's a bunch of crap too. It gives the press or the media something to write about, but we're not going out to live in a hostile environment. It's “technically” feasible to do it. You could go down there and live. You can go and stay on the moon. But the effort of supplying somebody on the moon or doing anything up there is enormous. Yes, we can get there and you can walk around on it, but it's not a developmental thing. Nobody is going to go live on Mars. Buzz Aldren likes to talk about getting to Mars. He has a license plate that says “Mars Guy.” He wants to go to Mars. Transferring civilization to Mars is not going to work. We have enough problems here on Earth. We can't solve them here, and we sure as hell can't solve them on Mars. You can get there, yes. With great effort, you can send a man up to the moon or you could, conceivably, send him to Mars. There's probably no real technical objection to that, but the enormous effort required to do that doesn't warrant it, in my view. Moreover, it didn't warrant it for living under the sea as they were talking about. We did what we were asked to do. We were able to get the technique so that we could get there and do productive work, and that has been happening all over the world in the diving industry. They have taken it and refined it so that you can do it better, but the press loves these things.

Donald R. Lennon:

The man you lost, was that due to faulty equipment or human error?

William M. Nicholson:

Fundamentally, it was due to the “want of the nail.” The guys in the shipyard didn't pack the joints properly, causing a leakage. Our efforts to solve the problem put the diver

in. He made one trip down and got back. On the second trip, somehow, an accident happened, somehow his gear didn't get packed right, and he didn't make it back. The experiment was doomed because we had no money. We were operating on a shoestring, and we were running out of helium. We didn't have enough helium, and a whole lot of things like that. We couldn't pull the thing back and redo it, so we were pushing to try to save it. I have regrets about that. That's the one thing that bugs me occasionally. I wish I had insisted on their using helium for the original tests in the shipyard, which would have been expensive but would have solved it. I was two steps removed from that. I was back in Washington, and I had a Sea Lab manager who was running the Sea Lab Program out there. I guess I would sum up all the things I am talking about here as follows: I was running a group of very competent engineers. It's not that I individually did anything; I did very little, individually. I taught at MIT. What I did there was mine. But all the rest of these things were as head of a group or team.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is how things are accomplished though.

William M. Nicholson:

Individually, we don't get much chance to do anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Unless you're Rickover.

William M. Nicholson:

Well, he screwed up a lot of things, but he did a good job. There's no question that he got it done. But he did it at the expense of a lot of good people.

Donald R. Lennon:

But he took credit for everything.

William M. Nicholson:

Everything. There was nothing that ever happened that . . . like I started to tell you about the launching of the ship. He would not tell anybody that the ship was ready to be launched. The press found out about this, and they were marching around the Pentagon, saying, “What's this big secret launching that's taking place in New London?” They were

on the CNO and they were getting on everybody, going public with this. Well, Rickover would not allow us to do the normal preparation: notify the press, put out notices, and let the Congressmen know to get ready for a ship launching. He had absolute control until about five days before they were scheduled to launch, when I got a call from him. He said, “I have decided to let you handle it.” Up to that point, he wouldn't allow anyone to say anything. So I got the whole launch operation--publicity, and everything. I called the manager at the Electric Boat Company and said, “Hey, for God's sake, let's get the invitations out and let's get going.” We managed to make it but when it got tight, when they were being critical, I got the job. He was great at that.

The first time I went to a briefing for the CNO with the Secretary of the Navy, Rickover was there. I was not in charge; I was watching it. Rickover walked into the meeting late with a big chart of the NR1 and he said, “We are having financial problems and delay problems, but the problems are not mine. They are all in the command controls section up here. That's where the problem is.” That wasn't true at all, but he sold that, and I got the pleasure of solving it. But it was fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think that covers everything that I'm aware of.

William M. Nicholson:

I had a great deal of satisfaction that the HALIBUT and the SEAWOLF worked out well and were established under black cover. We weren't allowed to talk about that. That became public when one of our spy fraternities dumped it--triggered it--and after it had been done, sold the Russians all the information for $75,000 or something like that. I've forgotten how much it was. It was an interesting thing, different.

I remember that there was a guy from the CIA who came into my office and said, “Hey, I understand you are building a submarine that allows you to work out of the bottom.

Can you handle a box about that big through the hatch?” That's how we got involved in it, and we said, “Sure, we can do it.” They take this down and put it over the cable and pick up the signals. Originally it was done so that the submarines had to go back in, pick the box, and bring the tapes back. But it worked so well that I heard they finally hard wired it back into Japan and you could sit there and listen to them. That part I'm not familiar with, that was all done under the CIA. You could listen to the Russian conversations back and forth.[note]

[End of Interview]