| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #176 | |

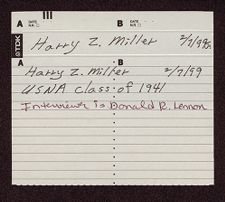

| Captain Harry Zeke Miller | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 7, 1999 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| [Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon.] |

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's start with your background.

Harry Z. Miller:

I was born in Philadelphia. I actually lived in Germantown until I went to the Naval Academy. I went to the William Penn Charter School the whole twelve years. It's a private school. I did pretty well along the way. I kind of slipped up on a couple of subjects when basketball became more important, but I still managed to get through okay. I took some of the courses luckily that were qualified for the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

At that time were you thinking in terms of the Naval Academy?

Harry Z. Miller:

Sort of. I think I had it in the back of my mind from the time my father took me down to the old battleship PENNSYLVANIA, when it was in overhaul in Philadelphia Navy Yard, when I was about eight or nine years old. Of course, through the Depression, it was going to be difficult going on to college since I was on a partial scholarship anyhow. My mother happened to be working for Congressmen Darrell at the time, so I ended up getting the first alternate to the Academy. The primary was a classmate of mine at school whose father was president of the alumni association at the time. But he failed the eye exam so I

got it. That's how I got in. I struggled with several subjects, having taken physics in school but I forgot to take chemistry. Of course, the first year in the Academy was chemistry. I was unsat, and had to take a re-exam, and got in. The second year, it was math, and I had to come back early. From then on I stayed away from those things to go the rest of the way. I played in several sports.

Donald R. Lennon:

Such as.

Harry Z. Miller:

Soccer. I was a goalie as somebody reminded me last night. I was the goalie for a while. Then basketball I loved. I never quite made the varsity, but I had a hell of a time on the B squad. We won a lot of games. As a matter of fact Johnny Wilson, the coach, got mad because the B squad beat the A squad, his varsity, in a practice game. So he had what he called our two best players and put them on the bench for the rest of the year. He didn't pick me so I got to play basketball for the rest of the year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why didn't he put them on the A squad?

Harry Z. Miller:

He did, he put them up there, but he just sat them on the bench and didn't use them. They were two classmates of mine, I won't mention names . . . oh I can. It was Charlie Nelson and Richardson. Of course, that took the heart out of the team. So we did alright the rest of the year, but we never beat the varsity again. That was that. Then, of course, we graduated early.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any thoughts concerning the level of instruction?

Harry Z. Miller:

I thought it was good for the time. I realize now that the curriculum has to be a whole lot different. But I thought they covered it and prepared you pretty well. We got off into some aviation in the second-class summer. We got to fly in the old P2Y2's. We did a little gunnery shooting from there, and so we got a taste of that. We went down in a

submarine in the Chesapeake and made an emergency surface because a merchantman was coming up the Bay. I thought it was pretty good. I thought they could have left the cutter races out that we had with those heavy whale boats they had down there at the time. Frank Cuccias and I were talking about it last night. They would always take you out and take you up to the Severn River Bridge and then they would turn you loose and say "OK, get back home." Well, the first cutter back home didn't have to secure the boat and bail it out and clean it. They got to go off, and it had to be done by the ones who lost.

Donald R. Lennon:

I hadn't heard of that before.

Harry Z. Miller:

Those things weighed a ton. I mean they were really tough to pull. I guess they were the kind they originally had on sailing ships, with four or six oars on each side. I don't mean a shell, I mean, a monster, heavy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Mahogany or something like that?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes. They were a “beaut.” I thought all in all with the sailing and everything else that it was pretty well balanced. As far as I was concerned, their navigation and seamanship courses were excellent. They were my two best subjects.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the hazing? I know it varied from individual to individual as to how much hazing they faced depending on the relationship with the upperclassmen.

Harry Z. Miller:

It was bearable. I thought it was penny ante. Even at the time, I thought it and have thought so ever since. There was too much of it. Somewhere in between, I think it went too far the other way, but a certain amount of it, I think, is necessary. Whether you call it just asking questions and making you answer silly questions and things like that. It's all part of that. As far as the double-timing up and down the outside on the ladders and so on . . . it was done.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other recollections of the days at the Academy, as far as any particular incidents that took place or stick out in your mind, individuals?

Harry Z. Miller:

Individuals. Of course, I'm sure everybody mentioned Uncle "Beanie" Jarrett.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of relationship did you have with Uncle Beanie?

Harry Z. Miller:

Jarrett was a company officer then he came back as a battalion officer. He was the kind who rates what you get away with. He caught some guy, a first class-man, taking a pie out of the mess hall and he says, "Okay, well, that does it. You're on report, but I'll let you have half the pie and I'll take the other half." He had a fantastic memory. From graduation, I didn't run into him again until 1956 when I was at the BROWNSON up in Boston for an overhaul and he was commandant of the First Naval District. I went over and they were occupying the back building because the front building had warped walls and was being repaired. There wasn't a great deal of lighting, but I paid my official call on him. He said, "Oh I remember you, your nickname was Zeke, Zeke Miller." He said, "I put you up on the report for not turning in one night on time." I thought, Yes, you sure did. He had an absolute photographic memory.

Donald R. Lennon:

I am always envious of people like that.

Harry Z. Miller:

He was much loved. He was a guy who would put you on report and yet you'd smile about it when he did.

Donald R. Lennon:

Joe Taussig is so taken with him.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, I know. Joe and I have exchanged stories about him. I'm jumping way ahead to the NORTH CAROLINA reunion in 1991 to tell you a story about Joe. We decided we'd go to the 50th Reunion down there. We were going to reenact the whole commissioning. Rex Rader out of 1940 called me from California and asked me if I would take the part of

Captain Hustvedt. First of all, I didn't tell him I couldn't get in my uniform at the time, but I said, "Rex, why don't you get his son. He's right here in Washington. And I know he'd be glad to do it." So Erling said, "Yes, he would," so naturally he did and did a great job. They gave him a wristwatch at the anniversary. Erling gave it to me because he had not been on the NORTH CAROLINA when it was commissioned, if you remember his story, although he went out with us on the shakedown. He said, "No, you were there and you were assistant officer of the deck and all that. Let me give you this." I didn't bring it with me.

We had gone to visit the widow of an old skipper of mine in North Carolina and went from there to the commissioning. Anyway, we checked into the hotel (we were in another hotel than the headquarters). After checking in, I said, "Well, let's go over to the headquarters hotel and see what's going on." So we went over there. After awhile, I heard this voice, an unmistakable voice, it had to be Joe Taussig's. Joe was going to be the guest speaker. He said, "I was supposed to be met by the president of the organization down here. Nobody showed up out there at the airfield or anything else and I had to get a cab to here. Now they tell me they don't have a room for me." I went over to the desk and said, "What happened." Well, somebody said he wasn't coming and someone else said he'd died. So I said, "Let me get on the phone." I got on the phone to my hotel, the Holiday Inn, and I said, "I've got the guest speaker for this thing tomorrow here and he has to have a room." Fortunately, I had been going to Holiday Inns quite a bit and they said, "We've got one. Don't worry, just bring him on over." So I drove him over there. We ended up with Joe the whole time, taking him down to the thing. The guy never showed up for him. The only time he ever showed up was for the banquet after the thing that night. Then he got together with Joe. What he was thinking of, I have no idea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who in the world was in charge of this?

Harry Z. Miller:

The enlisted president of the association. Not the State of North Carolina people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not the battleship people?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh no, they were wonderful. I talked to them a lot, Captain Scheu and the whole bunch of them down there. The curator, she's a hell of a nice gal. But no, this was the battleship organization of all the ex-crew members. I just thought it was so stupid. So we ended up having a good time with Joe and got him to every place he went.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the headquarters, I'm sure was in the Hilton, wasn't it?

Harry Z. Miller:

No, it wasn't. We thought it should have been at the Hilton. The banquet was at the Hilton, but the headquarters was out north. You went straight out the main drag and just before you turned off to get to Interstate 40; there was a motel on the right. I don't know whether it was a Ramada or something else. I have a program some place at home, but that was the headquarters for it. That was for the 50th. We were over at another one in the Holiday Inn and so forth. It wasn't the Ramada. I am drawing a blank. It was one of the lesser known hotels.

Donald R. Lennon:

I heard that Captain Taussig just laughed it off after a while. I think if I were him, I would have been so highly offended.

Harry Z. Miller:

He was. He did a good job. The next morning I asked him, "Joe, I know you're not going to hear from him. Do you need a ride to the airport? We're headed north; we'll drop you off."

He said, "No, I called the Marine that flew me down and he said he'd send a car for me." Now, that was his experience there. I jumped a number of years for that.

Donald R. Lennon:

He's always in a thing. I understand that he's not doing well right now. Someone was saying that his good leg is bothering him.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes. I'm kind of out of touch with him now because we moved. We lived in Reston for twenty-seven years and, of course, I went to a lot of the luncheons and all that. But we moved to Georgia last July, out in Stockbridge, and I kind of lost track of the Washington crew.

Donald R. Lennon:

I haven't seen him in several years myself. Let's get back to you though. Anything else concerning your Academy experience?

Harry Z. Miller:

We took a midshipman cruise. Particularly the northern Europe one was great, I went to that one. Of course our first class cruise was kind of truncated because the GRAF SPEE was at sea so we never got to Rio. I got to Rio in 1957 when I was skipper of the BROWNSON. That's the next time I got there. Other than that, the cruises were good. I met some nice people and so forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

On February the seventh you were assigned directly to the NORTH CAROLINA?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, I was in gyro school first. Then went aboard on the commissioning. I've got a paper at home, a copy of a plaque that they gave me when I retired, which has all the dates of where I was and when. I will, in addition, send you one thing, though--I have copies of it--of all the ships that I was on from the beginning. It came out to thirty-six.

Donald R. Lennon:

You must have stayed out to sea your whole career.

Harry Z. Miller:

No, it was strange. The story is explainable. In December of '42, I left the NORTH CAROLINA and went to the staff of COMTRANSDIV14 in the amphibs. We spent the next year and a half there. My permanent flagship was the HUNTER LIGGETTT, a Coast Guard transport. We were only on that periodically. In between, we had flagships like the

PINKNEY, the high-speed hospital transport. We had a merchant ship as a flagship and we had all kinds of liberty ships as flagships. These were all legitimate transfers on orders from one place to the other, even though some of them were only for two days. But they were all our ships. I compiled it just for Vic [Delano] and sent it to him. He said he couldn't believe the number. It was some twenty to twenty-two ships in that group. The rest of it has been normal assignments.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's talk about the NORTH CAROLINA and your experiences there. After completing gyro school and going to the NORTH CAROLINA, was it still under construction?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, we were being commissioned. We were commissioned on April ninth and I reported aboard April ninth like everybody else did. We didn't get underway until probably the shakedown. I guess it was July or August, something like that, before we finally got underway. Of course, it was interesting to see going down under the Brooklyn Bridge. We had to drop the CXAM radar antenna and at that we only cleared the Brooklyn Bridge by a little over my height. That's how close it was. We had the problems, I'm sure you have heard all about, the vibration in the shafts and they had to change propellers and shave them and everything. We finally got to be able to reach twenty-seven knots without shaking ourselves to death. But it took about six months before we were straightened out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was that part of the shakedown cruise?

Harry Z. Miller:

The shakedown cruise was the one that was to fire the guns. When we fired the guns, it was the heaviest salvo ever fired from a U.S. ship. There is a picture of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

But I was thinking, why didn't they see the problem with the propellers at that time?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well they did, but they had to change the propellers and it wasn't much better. I've forgotten how many times they changed them, and then they had to shave them. I don't know whether they changed them from three blades to four finally along the way. I stood watches down there; but, by that time, the problem was over. Exactly what the final solution was I don't know. But we were back in dry dock about four or five times. Of course we were in dry dock when December seventh came. They sounded General Quarters and I remember the Marines saying, "Well you might as well get the potatoes up here because that's all we've got to fire out at them." Of course, we had no ammunition.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once the NORTH CAROLINA did get ready and headed for the Pacific . . . .

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, we did refresher training in Guantanamo, then we were assigned to Casco Bay. We waited there and we had that one little episode with mines, and when the WASHINGTON came up to relieve us, we then took off for the Pacific. That was in July. The Marine captain caused me no end of grief for that. The WASHINGTON came up. I was the basketball coach and played on the team. We had won twenty-six and lost two, playing all over the east coast wherever we stopped. The WASHINGTON had a hell of a good team and challenged us. So we ended up playing and Bill Maxwell was the athletic officer. He was over there and there was a lot of money bet on that game. We were behind at the end of the first half by about ten points. Bill Maxwell said, "Well, where are your two Marines at the half time?" I said, "I don't know." He got on the phone and Captain Shurgy(?) had kept them aboard. And he said, "You get them over here now!" Well, they arrived about the middle of the third quarter. We caught up to them and had about a one-point lead on the team. Their forward was an All-American. I was guarding him and they had the ball out of bounds and under the basket after we had gone to one point ahead. They flipped it into him.

Believe it or not, he's standing on their foul line and throws up a one-handed wild shot just before the buzzer and it went in. I wasn't going to let him get anywhere past mid-court, so he just threw that thing up--three quarters of the length of the court. So people were a little unhappy with Captain Shurgy(?). Anyhow we left right after that. Then we stopped at Long Beach and then we went on, I guess, to Pearl.

Donald R. Lennon:

The reception you received at Pearl was rather, I won't say grand, but you were well received.

Harry Z. Miller:

Well received, yes. Well.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any particular remembrances of that?

Harry Z. Miller:

Not too many. No, I don't really. I remember one instance were Bill Maxwell asked Joe Wade and I if we had a date for the evening.

We said, "No."

He said, "Well, I'll take care of that." He picked up the phone and--he had a “black book.”--called them. They said, "Well, we have dates," and he said, "No, you don't. You're going out with friends of mine." Anyhow, I don't know whether it was that visit or after the torpedoing. I can't remember. But it was; they welcomed us. Yes, it was almost a 'where have you been?'

Donald R. Lennon:

There was still a lot of visible damage at that time?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh yes, lots of it. You could still smell the carbon and all that. Well it was that way, too, a couple months later when we got back with the torpedo hole.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you want to recount the episode, when you were torpedoed?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, actually I was down in my room at the time. I don't remember what I was doing, but I was going on watch shortly. We weren't at General Quarters. We were just in

standard Condition Three. All of a sudden, you could tell we'd been hit by something because it was a big jolt and the ship rolled a little and pitched. People started running for battle stations and all that. We ended up in battle stations for a while. Then, of course, the rest of it is all hearsay to me because the damage control people did such a great job of shoring up the hull, which we still demonstrated later when I had the Damage Control School up at Newport. We showed that as a great example of shoring our bulkheads.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no warning at all in this particular case. You all did not realize that the enemy was even close by?

Harry Z. Miller:

I don't think the WASP did either. From what I gathered, they were Condition Three also, or whatever condition they were in. Well, you know the story that the Japanese never knew that they hit us until years after. One of the reasons was because we made twenty-five knots afterward and went out. They told us to get out. We were going by help by way of the New Hebrides Islands. The WASHINGTON came in the same night and had the same camouflage. Of course, they are the sister ship. So, the Japanese never knew we'd been hit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because you switched ships?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, we had been reported as sunk all over the world.

Donald R. Lennon:

I knew that. That is why I was taken aback when you said the Japanese didn't even know that they had hit you.

Harry Z. Miller:

Not in this case, they didn't. In that interview they did with that Japanese captain, he said, No, he had no idea that he had hit us. He knew he had hit a carrier and a destroyer, but, beyond that, he didn't know about it. Apparently, the way I pieced it together from reading a lot of stuff about it, we were well over here and were not actually in the formation with the

WASP at all. We were well over here and they were using that long range torpedo called the Long Lance. It was near the end of its run that it hit us.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he wasn't even firing at you?

Harry Z. Miller:

No, he wasn't even firing at us. He was just firing a spread at the WASP. Anyhow, it was a pretty good hole. We only lost three people in that. As you probably know, we were very lucky.

Donald R. Lennon:

But it was still able to do twenty-five knots with the compartments flooded and everything?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, we did twenty-five until we got past the Espiritu Santo and then we slowed, because they didn't want to tear any more of the side off of it. Then we stopped at Tonga Tabu and buried the three people. The big queen out there--six foot something or another--she said we could use the burial ground and we buried the three people there.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they did not get sucked out or lost overboard during the torpedoing?

Harry Z. Miller:

As near as I can remember, they were in the head and washroom that wrapped around turret two, up in the forward part. Why they were in there at that particular time or why there weren't more people in there since we weren't at General Quarters. . . . That was even more amazing that there weren't more in there. There were apparently only three. They never got out. There wasn't anybody in the magazine that did get flooded. We were very lucky. It could have been a lot worse.

Donald R. Lennon:

Proceeding from there for repairs . . .

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, one of the things I recall from that incident was that the admiral in charge said that he wanted to withdraw the carriers and so forth to the shelter of Espiritu Santo for fueling. The answer came from Admiral Ghormley who was COMSOPAC at the time. He

said, “No, and use economical speeds of 16 knots,” which makes you duck soup for a submarine. It was shortly after that that Admiral Halsey took over.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a number of destroyers did they have out there trying to search for subs?

Harry Z. Miller:

I think--I really have to think back--at the time, I don't think we had more than maybe five or six for each group. I think. I should know because I had to check the plot when I had a watch, but I can't remember, exactly.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you risking your carriers, battleships, and cruisers not to have destroyers or at least DE's out there?

Harry Z. Miller:

We didn't have a lot of them. That was one of the big problems. We didn't have a lot. This story fits nicely. When I was on the HUNTER LIGGETT coming back in April 1943, coming back from Guadalcanal, we had one destroyer escort and a merchant ship that had offloaded. We had the MENOMINEE and that tender or seagoing tug, the BUTTERNUT, and that tender, none of which were escorts. This was the convoy. This was the most they could spare. We had one destroyer protecting us. I had the flag watch and the bridge. All of a sudden, there was a "cruuump crrump crrump" about two hundred yards off the bow. The funny part was that the skipper of the Coast Guard ship said "Harry, I'm putting on a new young ensign who's OD, since we are away from Guadalcanal now. If he doesn't do the zigzag right or turns early or something, I want you to chew him out on the voice tube." So I said, “I would.” So, with this “crrump” I was just heading over to say something to him, because he had swung early. If he hadn't swung early, we'd have been hit. I'm sure we would have been hit. I told the captain later, I said, “I sure as hell didn't say anything to him." The funny part was that I called the commodore saying, “Well, call the

escort. Ask him what he's doing.” So I called him, and his voice from the radio came back, “I'm dropping an embarrassing barrage." There were depth charges going off. So I said, “I think if you look up, you will see that's a 'Betty' up there that just dropped.”

Donald R. Lennon:

So they weren't subs, it was aircraft?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, it was just one lone aircraft, but it gives an idea of how scarce escorts were. Even when we went the other way, we were lucky if we had two taking troops up, just for backup at Guadalcanal. I don't mean for the landing. We had more for the Bougainville landing, but by the time we got to the Bougainville landing in November of 1943, we had quite a few more ships. It was touch and go obviously.

Donald R. Lennon:

Despite the fact that the country was turning out destroyers and destroyer escorts at just a phenomenal rate . . . .

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, yes, but the phenomenal rate wasn't, I don't think, really until the beginning of 1943. I think in 1942 they were just gearing up for it, because I know most of the ships that I was around later had all been commissioned in late 1943, 1944, and 1945. Lots of them. The BROWNSON was commissioned in 1945 and the HUGHES, a DD, that I was skipper of, was commissioned in 1944. Very seldom . . . I went back over the list sometime ago just to see if--I don't remember what I was doing it for. Oh, I know. I was given a gift of Janes's Fighting Ships 1942. My boss in real estate gave it to me. I went back to 1942 and a lot of this stuff was under construction, but it was not in the fleet.

Donald R. Lennon:

After the torpedoing of the NORTH CAROLINA, how much longer were you aboard?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, the torpedoing was September fifteenth. I guess we got back to Pearl about October first and we left about November. We missed the November twenty-third action.

So we must have gotten back down there around the twentieth, late November. Then, I left at the end of December.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you reassigned?

Harry Z. Miller:

They call it Commander Transport Division 14 staff. I was flag lieutenant and operations officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you were still there in the same area?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh, yes. I was still there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you tell us something about what you all were involved in?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, we were taking Marines up to Guadalcanal and sometimes bringing convoys back to New Zealand. We did that twice. We did amphibious operations with them off Paekakariki Beach off the west coast in preparation for the Bougainville landing. That was in 1943. That generally was the pattern of our movements. We went back and forth with each different convoy. We went over to Fiji and picked up some troops over there at Mande [Mandeville, New Zealand?] and brought them back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Japanese zero in on these transports very much or were they more interested in trying to pick off the other warships in the fleet?

Harry Z. Miller:

I'd say they were more interested in trying to pick off warships in the fleet, and the airfield, Henderson field. I know I did the foxholes dash at Henderson field one time. We landed. Right after we landed in our plane, we were going to pick up a ship. We had a Condition Red and the guys said, "I'll show you where the foxhole is." And I said, "Well, I will break the world record getting there, I guess." I don't really recall offhand any transports actually being hit up there. I could be wrong. I know that all the warships, or most of them, were hit. I would have thought that since we were in that business at the time

that we would have been aware of whether they were transferring their effort to the transports. But we usually tried to get in there, just coming in overnight at dark, because they used to just fly one plane back and forth. I have forgotten what we used to call it--the Japanese plane that came in. But they used to fly that in and out. We used to try to arrive first thing in the morning and offload everybody as quickly as we could. If we could turn around and be out of there by afternoon, so by that evening when the time they had time to launch their planes and stuff from up there, we would be about at the limit of their range steering eastward and then south.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these high-speed transports or how fast were they?

Harry Z. Miller:

Twelve to thirteen knots. No, we didn't have any high speed transports at all. We had the PRESIDENT POLK and the PRESIDENT JACKSON.

Donald R. Lennon:

Most of these were merchant ships that had been transformed for troop carries?

Harry Z. Miller:

Some of the Liberty Ships were just converted as Liberty Ships and carried troops. Some were built that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were using a lot of Liberty Ships as part of that?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, they used quite a few of them. There were a number of U.S. flagships that were converted. Of course, we had a lot more later that we built. But again, they didn't arrive until late 1943 and 1944.

Donald R. Lennon:

They built a lot of the Liberty Ships in Wilmington.

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh, I know they did. They built them down in Brunswick, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

One of my recollections as a kid was the layup basin in Wilmington. When they just filled it after the war, they had several hundred at the layup basin there outside of Wilmington. It was rather ghostly looking.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, I know. I know I went to look for the one up here in Jacksonville and told my wife I was going to show her. I was too late. It was gone. One of the sad sights that's always been mine is at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, because I was very familiar with some of their ships. I was at New York Shipbuilding in Camden when they took the ALASKA out and didn't finish it. My cruiser inactivated there at the end of WWII. There were three or four ships there that I was quite familiar with. As the years went by, they looked tireder and tireder sitting there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Until they got the torch. Any other thoughts about transporting troops while you were on this assignment?

Harry Z. Miller:

It was interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular instances you can think of, or anecdotes from that period?

Harry Z. Miller:

I remember going on liberty in Wellington with a couple gals. We were told to go out and pick them up at one of these anti-aircraft stations. Cab driver dropped us at the foot of the hill in the middle of the night and said, "I'm not going any farther." We started walking up the hill and there was this "Halt, who goes there? 'Snick, Snick.'" It seems they didn't want us to pick the gals up. But, as far as the other, we had problems at Paekakariki in repeating. In a way, it was because of the tremendous cross currents while we lost a few people--training and LCDP's. But, in a way, it was good we did because it turned out that the beach at Bougainville could be the same way. So we ended up--the second time up at Bougainville--we timed it better and we didn't lose anybody. By that time the Seabees already had an airstrip and an ice cream plant built--Seabees' first priority.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were a remarkable group.

Harry Z. Miller:

They were. We took a battalion up to Guadalcanal and they were very interesting to talk to. The commodore with them was a father of a guy that was in the class of 1943 at the Academy, whom I knew. I saw a lot about this business and how he got into the Seabees. They were a tough bunch. They could drop their tools, grab their rifles and hold their own with the best of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long were you involved in transports before you were reassigned?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, let's see. How long? I guess from December until the next December. Then we were back in San Francisco for an overhaul. We went back with the HUNTER LIGGETT, our regular flagship. She was kind of top heavy and they were very low on fuel. We went through the Golden Gate Bridge and as they started to turn to go into--Moore Shipbuilding Company had a dry dock up there. We heeled over twenty degrees and we stayed that way all the way until we were alongside the pier.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was that top heavy?

Harry Z. Miller:

We didn't turn over. Then, we staff left them and we went back out on the MARTIN MARS and flew to Pearl Harbor. Then we flew down to the Noumea and picked up another flagship for the Raboul invasion, which never came off. That was when I was finally detached. It was COMTRANSDIV 14; then it became COMTRANSDIV 10, but it was the same personnel. I was detached in around April 1944.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many flagships had you had during that time?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, I would say about twenty-two. I will give you the list. There were a couple times when we were just passengers, so it was not a flagship. But we had official orders. We had about fourteen different flagships. If I am wrong, I'll correct it.

Donald R. Lennon:

That should be some kind of record. In just over a year's time you had been on over fourteen different ships. In April 1944 you went to the SAVANNAH.

Harry Z. Miller:

It was in the Navy Yard in Philadelphia. It had been hit by one of the German buzz bombs. She was in there under overhaul. About half the ship's company and officers had come from the South Pacific and about half were ones that were left from Europe. Their argument was that there was no war in the South Pacific; it was only a war in Europe. A few hard feelings went back and forth. Anyhow, it turned out the ship got settled down and I went to Fire Control School with my associate, who had come from the South Pacific. We were in DC and then came back and then the ship went out.

Well, I guess, the first thing we did of real interest was we went on the Yalta trip. We were the decoy cruiser. We were on the one that was about three hundred miles ahead of the AUGUSTA. My roommate and I laughingly said we were going to have a pennant hung between the stacks saying, "He's not here. He's over there." In any event, we went through Gibraltar at about thirty-one knots. We never saw so many planes and everything else and anti-sub things. There were thousands of them it seemed like. We stopped at Algiers. We stopped there overnight and then we went to Malta. In Malta, they got together and Admiral King was over there. Oh, they had a big get together over there. Mark Hasley, who was bossun entertained his crews out there, all in pitch black, of course. The only interesting thing I remember is the night that Admiral King had everybody over to the AUGUSTA with Roosevelt. I was duty commander and the officer said, "I just got a message from the flagship that said, 'We want Ensign King over on the AUGUSTA. Ernie King's son.'"

SIDE ONE ENDS.

I said, "Wait, hold everything. Let me talk to the exec." So I went down and told the exec and he said, "Oh, for God's sake, get him on the boat and get him over there." So he got over there. But I have no idea what he had done.

Young Ernie didn't like the Navy because he had four sisters. He was the only boy and I think his father made life rather rough for him.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, to be the son of an admiral, I would think, would be rough anyway.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, to be the son of the Commander-in-Chief. An admiral alone, but the son of the Commander-in-Chief. I liked him. He was a nice guy. But I think he got out of the Navy as soon as he could. So that's when we split up. The AUGUSTA went on to Yalta and we went to Alexandria. Then we joined up coming back. We went out about thirty-one knots again. So that was the end of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, as decoy, out of ignorance, was the SAVANNAH sailing alone?

Harry Z. Miller:

No, I think we had two destroyers with us as I recall. I should know. I had OD watch or air defense watch. We were rotating. But I know we had at least two.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wouldn't be much of a decoy--if it were sailing along by itself--is what I was thinking.

Harry Z. Miller:

We had at least two. The AUGUSTA had a lot. I am sure they did. I know we had at least two. We may have had four or five. I am not sure. Then I guess the next thing we did was train people out of Newport. Going up to Newport, we would take out pre-commissioning details. We would take out for training the ones that were going to other ships--new ships. We did the training for them. We'd go out, just come back in, and then try to beat the fog back in at night. Sometimes we would stay out three or four days. Again it was still wartime, so I mean we were not going that far out when we trained them. Then I

eventually got detached temporarily because they were taking midshipmen out. Now we're talking after the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you stayed with the SAVANNAH until the end of the war.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes. We were taking midshipmen out on the cruise. I don't know where or why. It wasn't very far, but they took a whole bunch of people off and sent us up to Newport. We were sort of a precommissioning detail, except that all we were doing was training the new people that were going to the SAVANNAH. We finished that and went back and the war was over.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is a TDY type of thing?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah. Then we got on “magic carpet” duty. That was interesting. Six cruisers made two trips. I would guess we brought back a total of eighteen thousand troops, taking all the planes off in the hangar space out. One trip on the QUEEN MARY would have taken all eighteen thousand.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was how many trips?

Harry Z. Miller:

Eighteen thousand is all we brought back.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know but how many trips?

Harry Z. Miller:

Two trips. Six cruisers, two trips each. A lot of money was spent for that. Some of it was pretty rough, too, because it was December and December in the North Atlantic . . . . There were a couple of mornings that I can recall being up on the bridge and I was looking up. Well, the height of eye was forty-four feet and I was looking at fifty to fifty-four foot waves on the sides--twenty-seven foot waves measuring from trough to crest. And we were not rolling so much as we were bottlers sliding down the side of one and then turning like this and going up the side of the other. The captain tried every course I think from south to

north to try and ease the thing and make headway towards New York. Six straight Northeasters came across the Atlantic during those trips. Some of the cruisers got damaged pretty badly during those trips, but we all survived. Then we went to Pensacola and trained catapult aviators. I feel sorry for the ones who died because they never did catapult something from U.S. cruisers and battleships. Of course they did catapult some of the others, but it was an entirely different type of catapult and I catapulted off the SAVANNAH several times and that was the short rail catapult. It was a five-inch charge and I'm telling you there is no jolt like it. When I got on the WASP they said, "Oh you're going to be green at this." I thought it was easy. Nothing to it compared to it. . . . Then the steam catapults on the big carriers, but even less.

Donald R. Lennon:

Apparently there were quite a few fatalities in the catapult training?

Harry Z. Miller:

Two of them. It was too bad.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that due to human error or just one of those things?

Harry Z. Miller:

I don't know. I was communication officer by that time and I didn't have a clue. Before that at one time I had been catapult officer and when I was main battery assistant I had to do catapults and everything else and I flew off of them and all that. But by this time I was communication officer. I just wasn't familiar with what the exact causes were. They had an investigation actually. Then we spent Navy Day in 1945 in Savannah, Georgia, which is the first time it had been back since the commissioning back in 1937. So that was quite a big deal. That was about it. After that is when we did the “magic carpet” duty, that's right. Then we ended up inactive in Philadelphia around Christmastime. So that was the end of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would have been Christmas of 1945.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once the SAVANNAH had been decommissioned, where did you go from there?

Harry Z. Miller:

I went from there to the MISSISSIPPI, which had become EAG-128 by that time. She was no longer battleship 41; she was experimental. We were working for Operational Development course. We tested out all the new fire control radars and search radars. We got first crack at it before they put them in the fleet, which was interesting. I was navigator and operations officer. I was navigator first and they created the billet(?) of operations officer. That was the in and out trip. We used to go out Monday mornings and come back in Friday afternoons and sometimes we would stay out over a weekend. The only side trip we got was to New York City one time. The rest of it was all in and out of Norfolk. I got to know that channel like the back of my hand--288, 270, 241. It was an interesting tour experimenting with all the stuff. We had a captain at one point who had his own mind about what he wanted to do about changing courses. We were steaming up towards ??? and I said, “Captain, come left 270.” No, I said, "Come to 241.” They had been on 270 on the exec's orders.

He said, "Oh, there is lots of room over there, Harry, I 'm just going to continue on for a way.”

The exec said, “Can he?” and I said, “Hell no.”

He said, “Captain you're going to run aground."

He changed course after that. My CIC officer, the Captain, said, “How good are we at this so-called fog navigation?” We were going in and out of the sound and sometimes it was foggy out. And, of course, we could pick up the buoys on the fire control radar. So we

knew where we were. Charlie Taylor would call up on the voice tube, "Passing Buoy six abeam to starboard."

And the captain said, "How the hell can he see that. I can't see it."

He had an overboard port down there and he took the cover off of it and stood down there and waited until it went by. He convinced the captain that they were pretty damn accurate. Yeah, we had to have a little fun once and a while--harmless. The exec finally figured out what he was doing. “Okay I'll never tell, but let's quit it.”

Donald R. Lennon:

How long were you all involved in these experiments?

Harry Z. Miller:

Until I left. When I left they were still involved. I left at the end of 1948.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this primarily new technology that they were experimenting with?

Harry Z. Miller:

New radars and new fire control radars, new directors sometimes. We tracked

P-80s--the first jets--to try to see how far out you could get them and track them and to see what the gap spaces were.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any failures?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh yes. Well this particular skipper, the same one were talking about. . . . OPDEV-4 used to send their own observers out. They would take notes on the test as well as we would. Then we would take them and have to show ours to the captain. Well, I didn't, but whoever was the gunnery officer had to take our results in to the captain. The captain had to sign off on it. Of course OPDEV-4 had the same figures from their own people. The gun boss, he and I went in to see him one time. And we looked at him and he said, "These are totally unsatisfactory."

And Harry Helms said, "Well, yes Captain, they are. The equipment is not performing the way it's supposed to perform. And that's our job."

The captain said, "Well I won't have that go off the ship that way. I won't have that go off that ship that way--it doesn't look good on my record."

Anyhow the upside of it was we had to send in some phony figures and I called OPDEV-4 and Harry and I said, "Just ignore the goddamn figures we're sending over there and accept yours."

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this guy an absolute moron?

Harry Z. Miller:

At times. He was an admiral striker. He just thought he had to have everything perfect or you weren't going to make admiral. He made it.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the purpose of you being there was to get accurate readings.

Harry Z. Miller:

Absolutely. So he didn't. We got so that we actually kept two sets of papers. He signed one set and that didn't leave the ship. Then he got transferred and from then on it was no problem. When they wanted to run the degaussing(?) at Old Point Comfort, they asked the MISSISSIPPI to run it. The exec and I had figured that there was no way we could run it, because we could not turn fast enough at the end of it without going aground. The captain was madder then hell at us. Well, the exec said, "Look I'm not going to let Harry be responsible. If you're going to run it, I'm going to have tell them you ran it on your own hope. That's the only way I can do it. We cannot make that turn." So the captain finally agreed with it. The MISSOURI ran it and guess what--it ran aground. And it took them a hell of a job to get her off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Actually you saved the captain's hide in that case because he would have been responsible.

Harry Z. Miller:

He could have gotten the rest of us, too. But the MISSOURI, I had to testify on that one as to why we had said no. I got called as a witness. “Why had we said no to running

it?” So I took the graphs and charts over and showed them why we'd said no--to help defend the MISSOURI guy because apparently the MISSOURI navigator had tried to tell him not to run it either.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it was the captain there who ordered it to be done?

Harry Z. Miller:

I don't know what happened to him. I don't think he made admiral. You get to a point of sometimes we used to say that “there but for the grace of God.”

Donald R. Lennon:

You were glad you stuck to your guns, huh?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah, I didn't want to go to that table. I also got told one time not to testify for a case. A submarine ran aground coming up to the Philadelphia Navy yard and the officer of the deck at the time happened to be a reserve officer, but he had not been given the right information by the eight to twelve watch and he had a collision. He didn't run aground; he had a collision. The powers that be decided they were going to fry this officer of the deck--the reserve officer of the deck. And they called around and since I had been in and out of there, they said no. I was stationed in Philadelphia at the time in Camden. “We would like you to be a witness for the defense.” And I mentioned it to my boss at the time, who was a shipbuilding expert, and he said, "Harry, hell no. You testify on that and you're never going to make commander in a million years, because the powers that be are USN against the USNR." So he had to say I could absolutely not be spared. We were getting ready to deliver the ROANOKE and I was the naval inspector aboard. Of course, I could have been spared, but it sounded good, so I didn't testify.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the poor reserve officer got fried?

Harry Z. Miller:

Probably. The guy who was the skipper of the ship at the time was Francis Lederer. He was the one who wrote The Ugly American. He claimed he was asleep and wasn't

notified or something, I don't know all the details. I just know I was out of that one. Life's little aberrations.

Donald R. Lennon:

From the MISSISSIPPI--how long did you remain on it? Any other incidents pertaining to the MISSISSIPPI?

Harry Z. Miller:

No we rescued a civilian aviator off the coast. On the ROANOKE we had a guy shot onboard and we had to grope our way in in the fog and dark.

Donald R. Lennon:

A guy got shot on board?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yes, a Marine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it just a dispute between two Marines or something?

Harry Z. Miller:

It was never known whether it was an accident or not. We had to race in the fog and everything and finally got somebody to come out with a barge to pick him up and take him in. Then we went back out in the middle of the night with the merchant ships, it was just a little hairy. We had good radar; it wasn't a case of that. You're just never sure that the other ships had it. But other then that I guess we never had any real accidents as far as accidents with firing shells. We were always firing the five-inch [shells] with new directors--evaluating with new proximity fuses. Some of the newer proximity fuses. It was an eventful two years.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then you left there and went to . . . ?

Harry Z. Miller:

I went to Systems Naval Inspector Ordnance, in the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden, New Jersey.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any outstanding event pertaining to that assignment?

Harry Z. Miller:

We just delivered the ROANOKE, and the incomplete ALASKA.

Donald R. Lennon:

What do you mean an incomplete ALASKA?

Harry Z. Miller:

Incomplete. Well, they decided not to finish the battle cruiser ALASKA. So it was towed over to Philadelphia Navy Yard and left there.

Donald R. Lennon:

When was this? 1948 or 1949?

Harry Z. Miller:

It was 1948. I was there until September of 1950. Then I went to commander of United Nations Blockading and Escort Force, otherwise known as CTF 95 in Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us something about that duty?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, that was an interesting one. Basically I arrived out there and I was supposed to be staff gunnery officer. The first thing the admiral asked was, “How much do you know about mines?”

I said, "Well to be honest, Admiral, I have seen the floating ones with horns on them and we shot at them on 'magic carpet' duty from the cruiser SAVANNAH.”

He said, "Well you're going to be the mine expert until our experts get here in about a month."

So I had to get together with the two quartermasters that I had working for me, and we started plotting all these reports on floating mines and everything. It was a hairy thing; we lost quite a few ships out there from those floating mines--the PIRATE, the PLEDGE, the MERGANSER. Of course, gradually they built up a mine force out there.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Harbor at Inchon where the tide went out so far--there were a lot of mines in there?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah. It was the mines on the east coast that got our ships. The west coast mines actually . . . because I think the tide was in and out so much and so fast that it was very difficult to plant mines. They did have the Chinampo estuary with mines. We mine swept that and cleaned it out. The British were in on that deal. We managed to keep that up and

bombard from there. Then we went up to Wansan harbor. MANCHESTER was our flagship and flag destroyers and threw a whole batch of ammunition into a reported division of North Korean troops that were in the hills. I say “reported” because it was reported by the South Koreans--the Roks. If they where there, we blanketed them. If they weren't there, we wasted a lot of ammunition. I have some pictures we took of that area--not where we were firing, though, but of the islands up there and some of the captured weapons. The only picture that is amusing and it's very difficult to tell is we had one picture that was taken over Wansan and there were three figures in there. And the photo expert said, "Oh that's nothing." And one of the guys who was sitting there talking to me, he says, “I'm an old country boy. I think I know what that looks like.” He said, "That's a three man privy." And I think that's what it is. It's just blurred enough that you can't be absolutely sure, but I think that's exactly what it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

How much ammunition did you spend on it?

Harry Z. Miller:

We did not spend any on that at all. The helicopter pilot was the guy who got the picture of that. Then we got two Siamese Thai frigates-- the PRASAE and the MONT (?) KAPAL(?). The skipper of the PRASAE was Prince Budichai, one of the royal family. I got elected to go along with him so they could go up the coast and do some bombardment up there. And the skipper of the MONT (?) KAPAL(?)--I can't remember his name--he was a graduate of the British school, too. He was a pretty capable guy; Prince Budichai was not. At any event we got through with that trip all right with my making some rather nasty comments to his boss Captain Nai Nopakun about Prince Budichai's capabilities in command and so forth. So sure enough, the next time they went up there on their own and

everything--I have a picture of him beached high and dry. He lost his ship. Then the inevitable came up.

Captain Nai said, “Well he's going to be court-martialed.” So the Admiral said, “Well, since you're under our command, can we have Commander Miller sit in on the proceedings?”

He said, “Oh certainly.”

So just before they started, Captain Nai said to me, “Harry, I want you to understand the Prince means absolutely nothing. As you people say, 'He will very likely make little ones out of big ones for the rest of his life.'"

They translated it all and they did convict him bad. The other one was great; he knew what he was doing. He was good at gunnery and so on, but Prince Budichai was just bad.

Donald R. Lennon:

How do you spell that?

Harry Z. Miller:

B-u-d-i-c-h-a-i. It's probably something entirely different in Thai. Captain Nai Nopakun was N-a-i N-o-p-a-k-u-n--two words. He was the senior Thai officer in Korea--a very nice guy. Captain Nai was the one who taught me that Thai was probably the most liquid language in the world. For instance if I say, “Ma ma ma, what am I saying?”

I said, "Well you're just saying ma ma ma."

He said, “Well each one of them has a different meaning.”

I said, “How?”

He said, "If I say 'ma' it's cow, if I say 'ma' it's woman, if I say 'ma' it's four."

Donald R. Lennon:

You were talking about the damage from the mines . . . . Any of the American ships get hit by mines that you were with?

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah, the ones that were under us? Actually the three that were sunk, were sunk before I got out there. Our staff was just being formed when we got out there. They had a commander of mine forces out there who had just four ships and they hadn't put him under anybody. They formed a United Nations Blockade and Escort Force and put him under our umbrella, which gave the Admiral a lot more say when trying to get help from Captain Spofford.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you using minesweepers?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh yeah. Two metal minesweepers got hit by magnetic bombs. The other one had a regular surface forward--the MERGANSER. I think we probably along the way may have lost another ship or two, but I can't recall.

Donald R. Lennon:

You don't remember the names of any of the minesweepers do you?

Harry Z. Miller:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why I ask is we have the records of a shipbuilding company in West Virginia that turned out a lot of minesweepers during World War II. We have all the engineering drawings and photographs of those. Beautiful minesweepers.

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh yeah. I had a good friend who ended up as a reserve captain and a civil engineer. During World War II he was a skipper of a flagship. And I had good classmate who went to school back at Penn Charter who ended up flown out to the Pacific in World War II and was a skipper of a minesweeper. On his first trip he had to go from Uneah(?) down to Australia. Well, the first thing that happened when they got up there, the chief on the bridge said, "I'll tell you what, Captain, I'll paint green on this side and red on this side, so you'll know which is starboard and which is port." Then he got down to Australia and he didn't realize that he had to make a call to the captain of the port. And the next morning he was awakened by this

lieutenant with gold dripping down from here to here. “Captain, aren't you going to report (said in a British voice) to the commander of the port?” He said, "Huh?" That was his beginning. The friend of mine was a lot better than that. He could do a lot more.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other reflections on the time in Korea?

Harry Z. Miller:

The only thing we ended up doing for days and days and days--which was to me an absolute waste of time--we had to evaluate. . . . Before I was relieved by the two intelligence officers--I was also the intelligence officer--my two quartermasters and I and other officers sat down at the flag plot one night. We figured out that the Chinese communists were going to come in and they were going to take the obvious route. They were going to go between the Eighth Army, the Roks, and the Tenth Corps. There was a channel down between them--for lack of communication between the two. That was the lines that they would come down to Korea. I briefed it to the staff the next morning and the chief of staff said, "Oh bullshit," and the Admiral said, "No, no, no, I think that's right. I think that's what's going to happen. I think I'm going to fly out to Tokyo and talk to them about it." He did, he went up there and Admiral Burke believed him, but General MacArthur didn't. That's where they came.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did MacArthur believe anything except what he devised himself?

Harry Z. Miller:

I don't know whether Commandant Joy(?) believed it or not, but Burke was assistant to commandant at the time and he believed it. That's my one claim to fame which didn't get me anything at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't get any credit for it.

Harry Z. Miller:

No. We just sort of looked at it and it was pretty obvious. Which way are you goingto go if you have good intelligence? You are going to go where you know where the two

sides can't talk to each other, at least not fluently enough to get by. I think other then that and the fact that we went up and bombarded the coast and the tunnels and we went up on the MANCHESTER and we had the MISSOURI with us. Of course the MISSOURI would get lots of damage. MANCHESTER's shells just bounced off those concrete beaches--six-inch shells. They didn't do anything but make a black mark on them. Then the Chinese rebuilt the damn things or the Koreans rebuilt them. If you knocked down a bridge, they built tracks over the riverbed that night and would be running trains the next day. The only way we could get them was the MISSOURI would come in and they would knock down one end of the tunnel and then knock down the other end of the tunnel. If the train was in there he was in there for quite awhile. Then we didn't have the MISSOURI all the time.

Then the experts decided they wanted to evaluate how much gunfire support was doing. Well, I spent many midnight hours taking these reports that these ships would send in and say they fired so many rounds and they estimated that it was effective to so and so and so on. We were writing all this stuff up and you knew from experience in World War II that half of it was bull. They didn't know. They were making an estimated guess. Of course, each ship that sent it in wanted to look good. So I'm taking this stuff and we're saying, “Come on, let's wipe this stuff out of here.” So we ended up with a report which I thought that probably proved that under some conditions that gunfire support was excellent and in others it was a waste of time. It was a waste of time for the MANCHESTER to throw six-inch shells into concrete buildings and concrete bridges, except it scared the workers and made the MANCHESTER feel good that they were doing something. Oh I'm sure they did some damage, don't misunderstand me, but five-inch shells from destroyers? Probably even less likely. Although they were used more for fire support in the front of the advancing

troops, that was effective, no question, that was definitely effective. So that was really it. I got there in September 1950 and left in April 1951. I went as exec on the LEWIS HANCOCK DD-675. We did take the DIXIE up the coast--a destroyer tender. We took them up and let them do shore bombardment, so they felt they were at least part of a war. The captain couldn't get them to cease-fire. They started shooting and they didn't want to stop. He finally got them to.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine when you know there's a war going on and you're sitting out there with a shipload of ammunition, you want to express yourself.

Harry Z. Miller:

Yeah, of course. She was being a destroyer tender; she was taking care of all the destroyers and stuff. The Admiral thought we'll just let them go up just once, so they can see what it's like. They had fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't getting any shore response from the North Koreans or the Chinese at all, were you?

Harry Z. Miller:

The British did on the west coast. They were under us, but they were semi-autonomous. They were a task group, CTF 95. They had their own admiral and they were sort of . . . we got reports from them and everything. I gathered they did get some. I don't remember them really saying much about damage. I know that only one ship got damaged. Well, we did have a destroyer hit a mine-- COLLETT. But as far as damage from gunfire, I think maybe there were one or two that got hit by shrapnel--while I was out there.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were reassigned here in April of 1951 where did you go?

Harry Z. Miller:

As exec to the LEWIS HANCOCK.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where?

Harry Z. Miller:

San Diego. Reactivated. It had been mothballed after World War II. She was in

Long Beach. I went to San Diego for the pre-commissioning detail.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the mission?

Harry Z. Miller:

Well, eventually we went to the east coast and then we went to Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you went back to Korea then?

Harry Z. Miller:

Oh yeah. We went to the east coast and old Captain Hancock (George Wright Hancock[?]) re-commissioned the ship and returned his sword to the ship. We went to the east coast and then to Guantanamo Bay for training, then crossed back to the Canal and ended up out in Korea. Then we escorted the carriers and we did carrier escorts and some shore bombardment. Nothing absolutely sensational. I have had to answer a couple of queries about a sub contact that we supposedly had. We evaluated it as a “non-sub.” This guy saying that some people had said that some other agents said that there was a possible sub in that area. Well he didn't hit us and we thought it was “non-sub.” So what else could you say? The ASW officer said, "It's non-sub." We spent an hour fooling with it. It never fired at us or done anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well did the Koreans--North Koreans--have much of a navy?

Harry Z. Miller:

No, this would have been Chinese. Definitely Chinese. But I don't know what they were trying to prove, but this was years later. I guess this just happened just last year that I got this letter from this guy. He wanted to know what I remembered of the incident. Well, I remembered very little of it, because once you evaluate as “non-sub,” you forget it. I even know I was navigator and exec and I had to go over the logs and remember the logs and I just remember that we said “non-sub.” But then we had lots of contacts we evaluated as “non-sub.” I would of remembered the ones we had evaluated “sub.”

Then we ended up in a squadron--DESRON 20--and we ended up going around the world. The largest group of ships to go around the world since the Great White fleet in 1908, even though we went to different ports on the way around. But we crossed the Atlantic together coming home--we crossed the Pacific originally. We all went to Hong Kong, then we all went to Singapore, then we went to Rangoon--four of us--which was very interesting. I got told to hit the mouth of the Irrawaddy River at midnight. We picked up the pilot and the pilot said, “Okay, we're going to have to bring her up to twenty knots."

I said, “Twenty knots? Why? Is the river shallow?" I was sitting there thinking, I can't see a thing. I can't take a bearing on anything or anything.

I said to the skipper, “Bob, I can't get any bearings or anything.”

So he said to the pilot, "Why the hell are we doing this?”

He said, “Well we have only six hours to get up to the harbor before the tide goes out. It wouldn't do you any good if you could see a buoy. The channel changes every day. You just have to rely on the fact that I know what I'm doing.”

And I thought to myself, oh, isn't that great. And he did. He went up there. And when I saw when we came out in daylight where we'd been I thought, oh God, I'm glad I didn't see it.

Then we stopped in Colombo. Then we went to the garden spot of the world at Ras Tanura, Arabia. It was after King Ibn Sa'ud had put prohibition in. So Aramco oil hit over there and invited the execs over and the commandant over to have some punch. He had two bottles left and had made a punch. The Arab stewards that he had there had figured, well jeez just two gallons of punch--that isn't going to make it. They had dumped in ten gallons of fruit juice on top of his last two bottles of whiskey. He was as sick as a dog. That was

our experience--we didn't go anyplace else. Then we stopped in Aden and then went up the Suez Canal. We stopped in Naples and, I guess, Caan as I was single patrol officer. Then I had to go over and defend somebody at Villa France. So the ships had to get underway and the operations officer was doing the navigating and they had to slow down and pick me up and get back to Caan. Then we stopped at Gibraltar and then that was it. The only interesting thing on that which is not for publication. Walter Dringle(?) was senior customs officer in Newport and he knew my late wife's mother very well and he knew me.

And so we came in there and he came aboard and said, “Well, we shouldn't have any trouble clearing you. But Harry, I guess you fueled outside port here.”

I said, “No Walter, you know I didn't do that.”

He said, “I guess you fueled in Gibraltar.”

And I said, “Yes,” and he said, "Well you sure got a deep draft.” We were eligible to bring back anything we wanted because we had been gone nine months and that ship was loaded with stuff that people had brought back. He said we were a foot lower in the water than we should have been. Not that it made any difference. So he cleared us. That same time he got a carrier coming back from the Italians. I think that a Marine had bought nine or ten Scandallion accordions, which can only be imported apparently through one person in New York City and he had them onboard the carrier. They would not let the ship go ashore until they finally got him. It had nothing to do with us.

We had a Kangaroo court on the HANCOCK [during the trip around the world]. We had a guy who was playing poker and turned out after awhile he was crooked. He was making a lot of money and apparently sending it home. Finally the chief master-in-arms

came up and told me, “You know this guy is cheating and we know he's got money stashed someplace. I can catch him cheating, but what do we do then?”

So I talked to the skipper and the skipper said, “Well, what would they like to do.”

“They said they would like to hold a Kangaroo court on him in the wardroom."

He said, “Well fine. Ragweed(?) can have one officer as a witness.”

So they got him, finally. He was a welder. He had taken a locker way back in anchor steering and taken it off the wall and had put a compartment in the back of it. He was stashing the money in there and then welding it back and painting it, so you never knew he had it there. Then when he got a chance to go into port he'd wait until some night and get the money out and wire it home to his mother. We were talking 250,000 bucks! So they held a Kangaroo court and decided the punishment was he not be allowed ashore for the rest of the way around the world and that when payday came, three people would be down there when the paymaster paid him. He would put his hand on the money and the money would be taken away and put back in the pot that he shared with the other people. In the meantime, he had to get it back from his mother. That is the only time I have ever been around-- I had heard of Kangaroo courts in my life. That was it. They solved the problem. Well, I left the day after he got back. Apparently, he had gotten most of it back. It was as good a way to solve it as any.

[End of Interview]