| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #157 | |

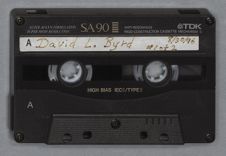

| Commander David L. Byrd, US Navy (Ret) | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| August 30, 1996 | |

| [This interview was conducted in San Diego, California, by Don Lennon.] |

David L. Byrd:

I was born in Alabama in 1918 and spent all of the first seventeen years of my life there. My father was a politician. He was the county tax assessor for several terms and subsequently became the county treasurer. When I got up into high school, I began thinking about going to college. One of the academies seemed to offer probably my best direction because my father was not wealthy. We were reasonably well off, but in those depression era days, going to college took quite a bit of cash money.

I looked into West Point first and then into the Naval Academy. I got their books containing all the information they distributed at that time. My father talked to our local congressman who happened to live in our hometown of Ozark. His name was Henry Stegall. He was in Congress for many years and became a very powerful member as chairman of the House Banking and Currency committee. He promised my father that he would have an appointment for me. When I graduated--and I graduated at the top of my classI went again to Henry Stegall. He said that yes, he had an appointment, but his

experience with his other candidates in previous years had been so poor and almost all had failed out of the Academy. He suggested that I go to Marion Military Institute first and try to upgrade my educational background. I had been to a small county high school, which had about four hundred fifty students, many of them bused in from around the county. My senior class had seventy students in it, me being the president of the senior class. I didn't have enough education in math, sciences, and English to really pass the Naval Academy examination at the time. So I took Stegall's recommendation and went to Marion for a year. There I learned trigonometry among other things and took the substantiating examination to the Naval Academy and passed.

It really didn't make a lot of difference to me whether I was appointed to the Naval Academy or to West Point. I had no particular naval background. I did have a grandfather who had fought in the Civil War. He was in Joseph E. Johnston's Army. He had entered the Army when he was sixteen years old. My grandfather lived the last few years of his life at our house.

I also had some knowledge of the Army through my brother who had been in the National Guard in our local hometown. But, when it came down to the appointment, the appointment was to the Naval Academy. I have some correspondence here, which I have included, that was between Senator John Bankhead and my father about the appointment and approval of the appointment, etc. The reason Senator Bankhead appointed me in place of Stegall is that Stegall finally determined that he didn't have an appointment. He obtained one from Senator Bankhead, because all of Bankhead's appointees that year had failed. I was able to go directly into the Naval Academy after passing the substantiating examination.

When I got there, I found in my plebe year that it was much more difficult than I had expected it to be--that I didn't have a very good high school background, even including the Marion experience. So I had to work very hard. I was in the bottom third of my class for the first year. I moved up a little in the youngster year and a little more in the second class year. Finally, by first class year, I was in the top third of the class, but I sweated blood and tears all the way through.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you attribute that entirely to your lack of preparation or was it in part due to lack of instruction or poor instruction there at the Academy?

David L. Byrd:

I think the instruction at the Academy was relatively good compared to what I had experienced. I just simply had not had the depth I needed in the various high school subjects that I had taken, although I took only the most difficult ones available in math and science. Science consisted of both physics and chemistry. Math, however, was only through algebra I. On the entrance exam, I made my best grade in English. But, I think my education problems at Annapolis were purely my lack of background. I hadn't had enough depth in the courses that I took in high school.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know I've heard some people complain that particularly when they had Navy instructors that there was really no teaching being done. You had to learn everything on your own.

David L. Byrd:

I had no problem with that. But you have to remember, in those days I had a number of classmates who had been to college prior to entering the Naval Academy. One of my best friends had finished three years in college before he entered, and he was merely repeating many courses. It was the second time around for many of them. Since a summary of your grades at the Academy represented your class standing and became your

seniority number upon graduation, previous college was a huge advantage. But as time went on, some of us who were in the bottom caught up a little bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Equalized?

David L. Byrd:

It equalized, yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

At the Academy, did you take part in any athletics or organizations?

David L. Byrd:

I was primarily a member of the "radiator squad." I had played varsity football in high school; but when I entered the Naval Academy, I weighed 131 pounds. College football was impossible for me. Instead, I did athletics on my own. I went to the gym rather regularly. I played tennis. I swam. In my first class year, I played golf because somewhere along the line during the Academy, we had five golf lessons as a part of our physical education training. I sometimes went out and tried running track, but I wasn't equal to the task of being on a regular team. So I did athletics on my own.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right. What about your plebe year? How did you react to the hazing?

David L. Byrd:

That didn't really bother me. I had no problem with hazing. I never experienced anything that was what you might call outrageous.

Donald R. Lennon:

It varied according to what first classman was assigned to you didn't it?

David L. Byrd:

I think that is true. I never really had a problem with hazing, I'd say. Military life came fairly easy to me. Since I had been to a military school, drilling and cutting square corners as we were required to do and wearing a uniform wasn't any problem at all. I can't say I enjoyed the whole experience of the four years, almost four years, in Annapolis. However, it was a great education. Later in life after the war, I went to post graduate school at the Naval Academy, Annapolis, and then on to Purdue University for an engineering Master of Science degree. There were thirteen Naval Academy students at

Purdue. We were top in our class in industrial engineering. We placed thirteen out of the top fourteen members in that class.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow, that's impressive.

David L. Byrd:

Some of the thirteen Navy students were not top students either. But we worked at it; that was the difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other thoughts about the Academy and your experience there?

David L. Byrd:

I enjoyed the summer cruises. My first one was to Europe aboard the USS NEW YORK, an old battleship. Going to the European ports was very interesting for me, because I had never traveled before I went to the Naval Academy outside of the states Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. It was a very good and rather maturing experience considering that we could go to the bars or wherever we wanted in Paris and no one cared or seemed to care as long as we did not get into trouble. My youngster cruise was in a destroyer up and down the East Coast. Then in my first class cruise, we went to South America, the Panama Canal, and to some U.S. East Coast ports. I found those all to be very enjoyable cruises. There were many new experiences. In between my plebe and youngster year, sleeping in a hammock in the air castle on the battleship NEW YORK was an experience, as well as going through the various drills we did. All of my cruises were great learning experiences for later sea duty.

Upon graduation from the Academy, I had asked for an assignment to a battleship. (We had choices at that time.) I was assigned to the USS NEW MEXICO, which was then based in Pearl Harbor. I had a month's leave, so after going home for a short period, I traveled across country by train to San Francisco where all of my classmates who were going to Pearl gathered. We had roughly two weeks there prior to sailing on the USS

HENDERSON, naval transport, to Honolulu. Enroute, we stood watches aboard ship, some in the engine room and some on deck. We had a partly civilian, partly navy type cruise to the islands.

I reported aboard the NEW MEXICO, along with four other classmates, Tom Hennessey, Stu Jones, Fred Wyse, and Bill Fisher. The NEW MEXICO normally tied up at piers adjacent to Ford Island at Pearl Harbor. As was the custom at that time, we were assigned aboard ship to a different duty every few months for a couple of years. My first duty was in damage control. Subsequently, I moved into gunnery as a junior turret officer, and finally into fire control where I was assistant fire control division officer. Fire control in those days operated and maintained the equipment for controlling the 14-inch and 5-inch guns. Later, I was assigned to spot 2, the aft main battery control station for General Quarters.

At that time, the NEW MEXICO was a part of the battle force that operated out of Pearl. As I recall, Admiral Pye was aboard the NEW MEXICO at the time as Commander Battle Force Pacific. We alternated between ten-day training exercises off Pearl Harbor and being in port for a couple of weeks. On one of these trips out of Pearl on a training exercise in June of 1941, the ship received a dispatch to immediately head for the Panama Canal and to observe radio silence. The mission wasn't stated at the time. Just as soon as the captain read the dispatch, we were on our way. Well that caused some problems aboard ship, because there were a number of families living in Honolulu, and we couldn't contact them since the ship was required to hold radio silence until we got to the East Coast. We could not contact anyone off the ship. A friend of mine had an automobile

sitting on the dock at Pearl. He never recovered it. It was damaged and, I guess, hauled off after Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the car sat down on the dock from June until December.

David L. Byrd:

Until the Navy hauled it off to a scrap yard. In another case, there was an ensign's girlfriend en route from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, who was coming to get married. She never knew what happened for about two months thereafter.

Donald R. Lennon:

She thought she had been stood up for sure.

David L. Byrd:

Yes. Well the ship went to the Panama Canal, passed through the Canal after dark without stopping, and sailed directly, as I remember, to Portland, Maine, where we anchored in Casco Bay. By that time we had figured out what our next duty was. It was North Atlantic convoy duty to assist the British Navy. Soon we picked up our first convoy off Halifax, Nova Scotia, escorted the ships over to just off the coast of Ireland, and turned it over to a British group of escorts. The NEW MEXICO returned to Portland for a period of relaxation and waited for the next convoy to come out of Halifax. We all realized during this first convoy that things got pretty rough with the cold weather in the North Atlantic. The Navy didn't have foul weather gear at that time, so some friends and I went over to Montgomery Ward's in Portland, Maine, and bought our own heavy jackets. I bought a canvas jacket with a sheepskin lining, which carried me for the rest of that convoy duty; but without that, I would have frozen in the open top anti-aircraft director where I stood watches.

Donald R. Lennon:

They couldn't accuse you of being out of uniform? Or weren't they very particular about that?

David L. Byrd:

The senior officers weren't too particular at that time, because everyone was trying to keep warm, especially during the night watches. The days were not too bad; but when you would go up into that open anti-aircraft director, called Sky Forward, after midnight, the temperature dropped way down.

Donald R. Lennon:

Even in the summer?

David L. Byrd:

Our principle convoy work was during the fall. In the heavy seas of the North Atlantic, the ship could get spray up over the Sky Forward director.

We picked up the next convoy in Halifax, took it across the Atlantic, turned it over to the British, and then went to Iceland to wait for the next convoy coming back from England. Our anchorage was a fjord about twenty-two miles from Reykjavik. The name of the fjord as I remember was Hvalfjordur. Since we were in a very northern latitude, we could go ashore and play baseball or something after dinner at night because it was still light. There was nothing else to do. There was nothing to buy. There were a few small sheep ranches in that vicinity. They raise Shetland ponies there, too. Other than sports, there wasn't much else to do except visit the other ships. Most frequently these were British ships and they served liquor in their wardroom. They sometimes invited us over for a cocktail and dinner. This continued on through the fall. But, one time we went to Newfoundland to wait for a convoy, instead of Iceland. The NEW MEXICO made several convoys and was back in Portland, Maine, on December the seventh, 1941 waiting for the next convoy, when we got the flash that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. {North Atlantic convoy duty in 1941 is best described in Notrh Atlantic Patrol by Lt. Commander Griffith Bailey Coale, USNR, Farrar and Rinehart, Inc.}

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have any contact with submarines during any of those convoys?

David L. Byrd:

Yes, we had submarine emergencies. The NEW MEXICO was a large ship and not equipped for fighting submarines. We were there for protection from German pocket battleships should they break out from protected harbors and attack our convoys.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well the greater danger to the convoy was from. . . .

David L. Byrd:

Was from submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was from submarines.

David L. Byrd:

On one of these cruises, the first U.S. destroyer was sunk. It was the REUBENJAMES. As I recall, the NEW MEXICO was about a hundred and fifty miles south of the position where the REUBEN JAMES was sunk, and we were with another convoy at the time. The REUBEN JAMES had a classmate of mine from the class of 1941 by the name of Craig Spowers aboard, and he was lost in the sinking. He was the first member of the 1941 Naval Academy Class lost to enemy action.

When we received word of the Pearl Harbor attack, the NEW MEXICO was at anchor in Portland Maine. We were ordered to proceed immediately to Norfolk Naval Shipyard to receive our first radar in preparation for Pacific duty. We received a “bedspring” air search, a fire control, and I believe, a surface search radar at the time. I had a particularly close association with the fire control radar, because I was in gunnery. It was a very crude radar that required matching pips when we were on target. Later on, this led the NEW MEXICO to a kind of fiasco in the 1943 Aleutian campaign, which I'll mention later.

As soon as we got the radars, the NEW MEXICO headed for the West Coast. We went to San Francisco, because at that time there was fear that the Japanese Fleet would attack the West Coast. We tied up at a dock at the foot of Market Street and were there

for roughly two months in early 1942. Many nights we had air raid warnings, but I think most of these, if not all, turned out to be false alarms. However, we sounded general quarters to man the guns and were prepared.

After being in San Francisco for a period of time, we proceeded to the South Pacific by way of Hawaii because the Solomon Islands campaign was going on, and the battles were beginning to heat up down there. We went to Fiji and were based in Nandi Bay in case the Japanese brought their battleships down. Since our fleet was pretty thin at the time, Battleship Division 3, which consisted of the NEW MEXICO, IDAHO, and MISSISSIPPI, was to be a last line of defense in the South Pacific if the Japanese committed their large battleships down there. This didn't happen, however, in 1942. A little later on, we moved to a new position in the New Hebrides at Efate. We remained at anchor in Efate, I think behind nets, until the Aleutian area became active in the war. Then the NEW MEXICO was ordered to go there. We had seen no action in the South Pacific theater.

At this time, my gunnery department battle station was spot two, which was the main battery spotting position aft. There were two spotting stations: spot one forward, spot two aft from which we could control the main battery guns. The NEW MEXICO participated in the pre-invasion bombardment of Attu in the Aleutians, prior to the U.S. Army landing, and later in the occupation of Kiska Island. Also, as I mentioned earlier, the NEW MEXICO participated in a fiasco off the Aleutian Islands, which we renamed the “Battle of the Pips.” During this fiasco, all of the major ships had contacts on their fire control radar one night while we were at sea off the Aleutian Islands. We thought the contacts were Japanese ships. We received orders to open fire from the admiral. All

ships opened fire, and we expended many rounds of fourteen-inch bullets. We were never able to see anything visually. It apparently was just spurious radar signals. So it became the Battle of the Pips, which I presume was caused by some unique atmospheric conditions that resulted in the radar's perception of a ship contact.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you didn't report sinking some?

David L. Byrd:

We did not report sinking anything, nor did we see anything. But we spent a lot of ammunition. I was in spot two, as I said, and I was straining my eyes. Control was in Spot I where the radar was located. I had only a spotting range finder in Spot II, and although it was a fairly bright night, I couldn't see a thing through the range finder.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it wasn't a foggy, shrouded night that sometimes occurs up there in the Aleutians?

David L. Byrd:

No. Visibility was fairly decent as it is some days up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

More often than not though, the visibility is very poor up there.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, it is in general and especially in the summertime up there. You get a lot of fog.

Following the Aleutian campaign, the NEW MEXICO was sent to the Navy yard in Bremerton. I received orders while in the yard to report to the East Coast to put the new cruiser QUINCY (CA71) in commission at Quincy, Massachusetts.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, approximately when was this?

David L. Byrd:

This was in September of 1943. I had previously tried to go to aviation training, in 1942, and had been turned down because of my eyes. So then I applied for submarines and was accepted at New London for the next class. This happened in 1943, while I was up in the Aleutians. The ship's doctor decided that I needed to go over to the hospital in

Dutch Harbor and be examined again before going to New London, because of my previous history of having failed the eye examination for flight training. Well, I went over to Dutch Harbor. The doctor checked me out pretty thoroughly and again failed me on my eyes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you tell them that down on a submarine there is nothing to see anyway?

David L. Byrd:

At that time, the submarine navy was still holding to the old requirements that you had to have 20/20 eyesight. Although my eyes might have been corrected, glasses were not permitted on those exams.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the requirement for sub duty was as stringent as it was varied.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, it was. My orders were subsequently canceled to New London, and I received the new orders to the cruiser QUINCY (CA71) under construction at Quincy, Mass. I reported there in October of 1943. I was a lieutenant at that time and was assigned as F Division officer, which was the Fire Control Division. My battle station was in charge of the main battery plotting room. On the QUINCY, the main battery consisted of eight-inch turrets. Next door, my assistant ran the five-inch anti-aircraft battery plot, and he controlled the twin gunned five-inch anti-aircraft guns aboard. We went through a pre-commissioning and a training period. While in QUINCY I attended an advanced fire control school in Anacostia, Maryland for six weeks. I brushed up on the newest things because the new QUINCY did have the latest gunfire control equipment.

We did our first training in and out of Boston for brief periods. Afterwards, in early February 1944, the QUINCY sailed down to Trinidad for a shakedown cruise. We operated in the Gulf of Paria, a relatively safe place, free of German submarines, until

March 1944 and the new crew was proficient in its duties. Then, we returned to Boston and finally to Casco Bay, Maine, for more sea operations.

Then in about early May of 1944, the QUINCY was ordered to Europe, and we went over for some training and bombardment exercises off Scotland. Later on in late May, we were directed to go to Belfast, Ireland, and wait there. We, of course, knew that while we didn't know the date of the Normandy Invasion or the landing area, we knew that we were being prepared for that invasion and being held until it happened. Our observation plane aviators were transferred over to the British and learned to fly Spitfires. Later, they would spot for us ashore. We basically sat at anchor and waited at Belfast for roughly two weeks. During this time, General Eisenhower paid an inspection visit to the ship. We were dead certain what was going to happen at that time, because we knew what position Eisenhower held.

The night of June 4, the QUINCY got orders to head south in the Irish Sea towards the channel. By the next morning we turned east around Land's End in England, and began to see this huge armada of ships collecting. We got partway down the channel and received orders to turn around and go back to Belfast. This turn around occurred June 5, the day before the invasion actually occurred. The invasion was planned for June 5. Because of the weather, it was delayed, and Eisenhower finally made his fateful decision to go in on June 6. We never did get back all the way up to Belfast before it was necessary to reverse again to meet the June 6 schedule.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of an awesome scene, wasn't it? The English Channel.. . .

David L. Byrd:

There were ships in all directions everywhere, absolutely. See, we started crossing the channel the night before at a very slow speed. We knew what was

happening. We had been told that the invasion was occurring and had a full load of ammunition, which we had previously taken on. We had mine sweepers ahead of us. We saw all the LSTs that we were passing packed with men and material. There were just hundreds of ships as far as the eye could see in both directions.

Donald R. Lennon:

Every size and shape possible.

David L. Byrd:

Every size and shape, that's right. Just before we had left Belfast, a U.S. Army lieutenant came aboard. He was from the 101st Airborne Division and was jumping the night of June 5. He got together with several of us in the gunnery department and with the ship's navigators. We received from him an Army grid chart of the Normandy coast. We knew then exactly which beach we were going to (Utah) and which radio frequencies to use to contact him directly once the landing occurred. We were to provide bombardment support to the 101st Airborne, which, as you know, went in by parachute and gliders. That night as we approached the Normandy coast, we could hear the mines up ahead being set off by the minesweepers. Down in the bottom of the ship, where the gunnery plotting rooms were, we could hear the bang against the hull of the ship as they exploded.

Sometime very early in the morning, about 3 a.m. or so, we had a meal of sandwiches and went to General Quarters. Very soon after we got into the bombardment area, but before we started firing, we had radio contact with this forward observer from the 101st Airborne. Now I don't know, but I think he was dropped in by parachute. I'm not sure of that. I had a radioman in direct contact with him in the main battery plotting room, so we were able to communicate back and forth. Other radio outlets were on the ship, but main battery plot was the key contact. The first firing was our 5-inch anti-

aircraft battery firing at targets right along the shore. Very soon after firing started, our Army lieutenant contact communicated with us and described a concentration of German troops at such and such a crossroads. He requested fire and we let loose a three-gun, six-gun, or nine-gun salvo, depending on what he needed.

I remember one time, he told us there were five tanks coming down this road and gunfire support was needed. We gave him a six-gun salvo and destroyed one or more tanks. Others retreated or were knocked out with additional salvos. Primarily, we were supporting positions at crossroads, and bridges, and places where the airborne division was trying to keep the German heavy weapon forces from approaching the beach where the landing was occurring.

Well, this went on day and night for two days. We fired up almost all of our main battery ammunition by the end of the second day. The ship carried nine eight-inch guns and our ammunition was of two kinds. We had both armor piercing and bombardment type ammunition. There really wasn't much need for the armor piercing; so we had quite a bit of that left. We fired all the bombardment type, which were 330-pound high-capacity shells. So at the end of the second day, the QUINCY left station and made a high speed run over to Plymouth, England. We loaded ammunition for the rest of that night. The ammunition was in small vessels that came alongside. We hoisted the ammunition up and loaded it in the turrets. Then early the next morning, we were on the way back to the Utah beach. We were there roughly for two weeks doing this fire-support work, until the U.S. troops got out of our range and we were no longer needed.

Donald R. Lennon:

The armor-piercing bullets or shells. . . .what would you use those for? Tanks and pill boxes or something?

David L. Byrd:

No, you would use those against large size turreted weapons in heavy concrete fortifications.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I meant by pill boxes.

David L. Byrd:

Most of the pill boxes were right along the coast, and they were within reach of the five-inch guns. The QUINCY eight-inch guns had a range, as I remember, of thirty thousand yards, which is fifteen nautical miles, and we were roughly six nautical miles off the coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you could fire well inland, really.

David L. Byrd:

We could fire well inland, supporting the troops as they moved. After about two weeks on station at Utah Beach, we got underway and went around to Cherbourg, which was still being held by German troops. There was a group of U.S. and British heavy vessels, cruisers and battleships supported by numerous destroyers, that spent one whole day bombarding the fortifications of Cherbourg and keeping them engaged, while U.S. troops came up from the rear by land to take the city. It was a somewhat hairy engagement that we were in, cruising around at twenty-seven knots zigzagging and firing, because the big guns in the fortifications there were firing back at us. At one time, we had a very close call when a salvo of large caliber ammunition actually straddled us.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, they had a heavy fortification along that line.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, they had large guns and heavy fortifications. But they soon fell to the U.S. Army that came up in the rear.

Donald R. Lennon:

Seventy-ninth Infantry Division was one of them.

David L. Byrd:

Was it? I'm not sure. I don't remember that.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was one of them that took Cherbourg.

David L. Byrd:

That was a one day affair. We went back to the Utah beachhead at Normandy, which wasn't many miles away from where we were. We stayed at Normandy for some time. We assisted as necessary, but things had already quieted down. Basically, we were just providing protection for the supply forces bringing stuff in, to push inland at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Supplies were probably coming from small ships shuttling back and forth across the channel?

David L. Byrd:

Yes, they were and that included Liberty ships.

The next action was in southern France in August 1944, where we participated in the bombardments and then the landings in southern France. Now there was a very capable German emplacement at Toulon, where they had taken a turret off of a German battleship and mounted it in the fortifications there. We were again, like Cherbourg, involved in dashing in at high speed, zigzagging all the way, delivering as many salvos as we could get off, and then dashing out to a safe location. At the same time, the troops were landing and that invasion didn't last very long. The Germans finally gave up, including surrendering the fort at Toulon. I don't recall exactly how many weeks we were engaged in this, but probably less than two weeks, I would think. We then were ordered back to the United States.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you say that you went in at high speed and fired as many salvos and then rushed back out, can you give me little more specifics on that, a little more detail?

David L. Byrd:

We had detailed charts of the Toulon area. The ships navigated based on specific points on the shoreline from which we measured our range and bearing continuously to fix the position of the ship. This input went automatically into the main battery and anti-

aircraft battery computers so they generated a range and bearing to whatever targets we choose to shoot at. If the target was visible, we inputted that information directly in our plotting room computers. The ship would go in at twenty-seven knots, zigzagging to avoid the shore fire, and delivering salvos accurately on target as we approached and as we retreated.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you acting independently or were you part of a battle group?

David L. Byrd:

We were part of a group, but there were not nearly as many ships there as there were in Normandy. It was a much smaller force. The QUINCY really was never damaged at either Normandy or southern France. At Cherbourg, we were never significantly damaged. I think we had some minor splashes and minor hits. It was said one time that the cigarette supply was flooded below deck because of a small hit, a fragment that went into a storeroom. But there was nothing of any significance; no one lost his life aboard ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Luckier ship than the previous QUINCY.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, much luckier. Following the invasion of southern France, we were ordered back to the East Coast of the U.S., to Boston, for minor repairs. Among other things the shipyard installed an elevator aboard ship to take people or freight from the main deck up to the captain's cabin in the superstructure.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you know what that cargo was going to be?

David L. Byrd:

There was no hint at that time as to what it was for, but we had all heard that President Roosevelt used an elevator when he was aboard a ship to get to his cabin. It had been done previously on other ships that carried the President. So we figured that the President was going to take a ride aboard the QUINCY. But things just sat for quite a

while after we got the elevator aboard. The yard also refurbished the captain's cabin. We basically sat around, did minor gunnery exercises down in Chesapeake Bay, and went to a dock in Norfolk.

The Christmas holidays came, and we were still sitting there. The ship was ordered unexpectedly up to New York City for a great vacation period alongside a pier in the Hudson River. If any one of us had any money, it would have been much greater, but the young officers were all broke. This was mostly because there were so many new wives who had been following the ship when it was on the East Coast, up and down the coast. They were in the Norfolk area at the time. We scraped up enough money for the wives to come up to New York when we were up there, so we did have a nice Christmas. But I remember my wife and I got down to our last two and a half dollars on Christmas Day, and we couldn't eat Christmas dinner, not even in a cafeteria. Things were pretty tight. Pay for people in the Navy was very slim in those days. It was difficult supporting a wife, especially if she was traveling around following the ship.

After Christmas, it was back to Norfolk. Our ship sat around for a while, and then it was disclosed that the President and his party were coming aboard.

Sometime late in January, the President came aboard with his party. We did not know exactly where the ship was going. I had to give up my cabin, which was very near the officers' wardroom. It was a two-man cabin; the communications officer and I bunked together. The communications officer was Dr. John Lattimore from George Washington University, and he had been a professor of Latin and Greek there for some years. He came into the Navy as a commander--full commander. Since he outranked me, he got the top bunk, and I got the bottom one. Both of us had to get out for the

President's party. Harry Hopkins, advisor to the President, was assigned to our cabin. I had to move everything out to the bunkroom, the junior officers' bunkroom. I was in there along with most of the other officers, including some senior officers. I was a lieutenant at that time. Promotions were pretty fast in those days. We had to move out, because the President's staff got priority. I do remember one time while we were out at sea on the way to the island of Malta, which was to be our first stop, I had to go down to my room to retrieve something that had been left there. Harry Hopkins was in bed in his pajamas in the middle of the day with a bottle of scotch alongside the lower bunk.

Donald R. Lennon:

You couldn't tell him that alcohol wasn't permitted on a U.S. Navy vessel?

David L. Byrd:

No, I couldn't tell him anything. I was awed by his presence, actually. We found out during the cruise that we were taking President Roosevelt to the Yalta conference. But our destination was the island of Malta. We made a high speed run across the Atlantic with a few destroyers as a screen, but they absolutely did no good; because we were cruising so fast that their underwater gear would not have picked up a submarine anyway.

We passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and went on to the island of Malta, which at that time had been almost obliterated by the Nazi stukas. They had bombed the island some months prior to our arrival and practically destroyed the shipyard and the whole town. Winston Churchill, came aboard the QUINCY the very first night we were in port and had dinner with the President. I still remember Churchill as he came up the gangway to the main deck from the dockside in the yard there. It was late in the afternoon, and the yard workers were standing around cheering, just really yelling. As Churchill started up the gangway, he got about halfway up, stopped, turned around, took

the cigar out of his mouth, handed it to his aide, and made the “V” sign. The dockworkers just went wild after this. He then took his cigar from the aide, put it in his mouth, and walked up a few paces. After a few steps, he did the same thing again until he got aboard. It was a very, very impressive entrance he made there.

The President had brought along his daughter, Anna Roosevelt Boettiger, on the cruise. She was from Seattle. She had been listed on the guest list as a mister. In fact, she was quite a mystery until everyone saw and realized it was the President's only daughter who was aboard. Winston Churchill also brought one of his daughters, Sarah Churchill, down to Malta, so the daughters visited during the dinner. Of course, the ship's company, except for the cooks and stewards, had nothing to do with this dinner except to pipe Churchill and his party aboard. The next morning the sailors had to cart off all the liquor bottles onto the dock. Apparently there was staff with both Churchill and Roosevelt that liked their liquor. The next day the two of them, Roosevelt and Churchill, flew to Yalta.

The QUINCY had a couple of days of recreation in Malta where we could go ashore and around the town. There wasn't anything to buy there. I remember I bought a lady's black scarf, such as women wear as a head covering to a Catholic Church. It was made from fabric lining from a German stuka bomber cockpit. There was little else to buy.

Donald R. Lennon:

How was the security?

David L. Byrd:

At Malta?

Donald R. Lennon:

At Malta, during and aboard the QUINCY, and everything during this.

David L. Byrd:

Normally, the QUINCY carried a detachment of Marines, maybe thirty or something like that, and these Marines performed duties as aides and security for the President on board. But once ashore the President had just his own party of secret service in so far as I know.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, there was no real precautions taken to protect. . . .

David L. Byrd:

None, that I could see. I imagine that the British had a very secure, navy yard at that time, but I don't know of any special precautions other than that.

After a couple of days at Malta, the QUINCY was ordered down to the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal. This lake, I think, is a natural lake somewhere south of midway the Canal, a rather isolated place. A small village was near there plus an airstrip. We waited at anchor in the lake for the President to return from Yalta.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that to hide it?

David L. Byrd:

No, there was nothing to hide the ship there. It was simply out of reach of German planes. As I do recall, there was a captured Italian battleship there. The battleship was in great condition and we were invited to tour it. It was anchored in the lake. The battleship had been surrendered, not defeated in battle, but surrendered sometime earlier in the war.

The President was very thoughtful as far as the officers of the QUINCY were concerned. He made available a twin-engine McDonald Douglas Military transport, to take the officers over to Cairo on one-day excursions, and I participated in one of those trips. I bought some knickknacks in Cairo and some African headsmahogany heads, ebony headsthat were very attractive; I still have them. But it was very thoughtful of the President to have done this.

After the Yalta conference, the President flew back to the airstrip near the Suez Canal. The ship was at an anchorage, and he had to come aboard in a boat. I was designated by Captain Elliott Senn, the commanding officer of the QUINCY, to be the boat officer for the president. We used the captain's gig, which had been dolled up relatively well. The gig carried a bow hook, a stern hook, a coxswain, and an engineer. I was the boat officer in charge of the crew. Fleet Admiral Leahy, who had returned aboard earlier from Yalta, went over with me to greet the President.

We met the returning party at the dock. As you might expect, two of the secret service men, who were a part of the security detail, made a seat with their arms locked together, and the President sat in that seat. They would simply pick the President up, walk over, and put him into his seat on the boat. He was not able because of his wheelchair, to make that transfer himself. I had no particular conversation with him at the time of his getting aboard, other than just a salute.

The QUINCY had a high freeboard. I don't recall how many feet the freeboard was above the water, but it was something like twenty feet. The secret service men had decided they could not actually carry him up the gangway at the ship. It would be too narrow and too difficult for two of them to try to walk him up that way. So the gig was placed under the airplane crane, which was aft. The QUINCY had airplane cranes on each side that we used to recover our seaplanes when at sea. The airplane crane hooked onto President's the boat and brought it up exactly to deck level. Then the two secret service men took the President out of the boat, lifted him aboard, and placed him in his wheelchair on deck. So having the crane made getting the President aboard relatively easy, except that I was standing in the stern of the boat and had one foot on the rail of the

boat and one foot in the waterway of the ship. As soon as the President was aboard, the boatswain's mate started to swing the captain's gig out, which had me doing splits. The boatswain's mate stopped the boat from swinging out just in time, before I dropped into the water. The President saw what happened. He got a great big laugh out of it and gave a wave. He laughed and waved.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine it felt kind of touchy being pulled up through the air on the boat with everyone aboard, didn't it?

David L. Byrd:

No. Boats are lowered over the side all the time, so that wasn't really a problem. It was an easy way to get him aboard and into his wheelchair. In subsequent days, I made the boat trip over again with Admiral Leahy and the boat crew to pick up King Farouk, King of Egypt at the time. He came aboard to see the President, but of course he could walk up the gangway, so there was no problem there. Then we picked up Haile Selassie from Ethiopia on another day to call on the President.

During this time at Great Bitter Lake, the Navy Department sent a destroyer, the USS MURPHY, from our group down to pick up Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia and his party. I'm not exactly sure why he didn't fly. I had heard that he didn't fly anywhere; that he didn't want to fly. I have read subsequently that he had never been out of Saudi Arabia. Anyway, the destroyer went around and picked him up with his whole party. I have a copy of the party, or the list of passengers, which I am putting into the record here. This list includes astrologers and food tasters. The most unique part of this party was that they brought their own food aboard. The Saudis made a sheep pen on the fantail of the destroyer, and they had mutton every day for the whole trip. Imagine live sheep running around on the deck of a destroyer!

Donald R. Lennon:

They slaughtered them right there?

David L. Byrd:

They slaughtered them aboard, as needed. They were fresh. None of the Saudis would go into the inside of the ship to sleep. They pitched their tents on the forward and aft decks. The destroyer couldn't sail at a very high speed coming back, because the Saudis had tents up on the forecastle with people sleeping all around.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did that include King Sa'ud too?

David L. Byrd:

I'm not sure whether the king was included there or not. The MURPHY arrived and tied up alongside the QUINCY. We could see them slaughtering the sheep there as they went about their business aboard ship. King Sa'ud came aboard the QUINCY and spent a day more or less with the President. I remember there was a Marine colonel who had had a great deal of duty in the Middle East and spoke Arabic; he acted as the U.S. interpreter. His picture is in one of those folders that I gave you here. King Ibn Sa'ud had his own interpreters, too. They had a relatively long day as I remember. He had wanted Roosevelt to go over and have coffee on the destroyer, but it was too difficult for the President to do this. This was a very interesting part of the entire trip.

When the President came back from the Yalta conference, we--those of us on the QUINCY--received a bulletin. I have that QUINCY bulletin. It was authored by Steven Early, the secretary to the President. This bulletin described what went on at the conference, what agreements were made, and who the participants were from the Soviet Union, Britain, and the U.S.

As we left the Great Bitter Lake, we made a stop at Alexandria and picked up the Secretary of State who had proceeded back separately. At that time Edward R. Stettinius,

Jr., was the Secretary of State. The QUINCY came back directly to the U.S. and dropped the President off.

It was then our turn in the barrel in the Pacific again. We were ordered out to the Western Pacific in early March 1945. We first went to Ulithi Atoll and joined up with the major components of the fleet.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just a matter of curiosity before we leave it. . . .once the President was off the QUINCY, did they dismantle and remove the elevator or did they just leave it on?

David L. Byrd:

They dismantled it in the shipyard at Norfolk as soon as we returned.

One other incident I forgot to mention was that on the way back the President's military aide, Major General Watson of the U.S. Army, died aboard ship. I believe he had a heart attack. His body was taken care of and refrigerated aboard ship for the balance of the cruise. It was an unusual event. He was the only person in my naval career that died aboard ship. I did lose a man overboard one time when I was a destroyer commander, but the major general was the only person I remember that died a natural death aboard ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Unusual for one to die of natural causes at least.

David L. Byrd:

When we were at Normandy, we picked up an aircraft that had been shot down near the ship. It was a British aircraft. We picked up the pilot of that aircraft and were directed to bury him at sea, which we did.

Following the President's trip, we went to the South Pacific, to Ulithi Atoll. We joined up with, I believe, the Fifth Fleet at the time--Halsey's fleet. At the next sortie of that Fleet, we went to Okinawa where we supported the carriers with anti-aircraft protection. We were involved with numerous kamikaze attacks.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say this was about the time. . . .

David L. Byrd:

Yes. We shot at a number of the kamikazes as they usually were going for the carriers. We were never actually hit by a kamikaze, nor were we directly a target of a kamikaze that I remember. But in May of 1945 the QUINCY was credited with destroying its first kamikaze. By this time, I was the assistant gunnery officer. John Blackburn, Class of 1939, had been made gunnery officer.

Sometime in June 1945 while operating with the carrier task forces, I received orders to go to the Postgraduate School in Annapolis. I had applied for the ordnance postgraduate course many months before, so I was detached at sea off Okinawa, got on a tanker that was fueling the QUINCY, and made my way back to Ulithi Atoll. Subsequently, after much waiting around, I got a flight to Guam, then to Johnston Island, to Hawaii, and finally back to the West Coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was the summer of '45?

David L. Byrd:

This was the summer of 1945. I had to report to Annapolis, where the PG School was located at that time, for the ordnance engineering course, roughly in August 1945. I spent two years at ordnance PG. My wife and I lived in a converted Homoja hut in a village, along with a number of other classmates. The village was near the Naval Academy PG School. We “enjoyed” half of an Homoja hut as quarters.

Donald R. Lennon:

Describe the Homoja hut.

David L. Byrd:

A Homoja hut is one of those sheet metal rounded. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

What we called a Quonset hut?

David L. Byrd:

The Quonset hut and Homoja hut were the same. The Navy cut the hut in halves. One family lived in one half, and another family lived in the other half. The half hut was

divided up into a combination living/dining room with a kitchen in the back and then two bedrooms and one bath with shower. All of these were tiny rooms.

I had a very satisfactory postgraduate school education, consisting primarily of graduate level courses in electrical and chemical engineering, electronics, and mathematics. Of course, they worked ballistics into the mathematics course. I also had some classes in plastics and chemistry. After two years there, I had a choice of spending a third year at a civilian university--either studying jet propulsion at Cal-Tech or industrial engineering at Purdue University. I selected Purdue University, although it turned out later that my subsequent career was more involved with jet propulsion than it was industrial engineering.

I spent a year at Purdue University and received a master's degree in industrial engineering. There were thirteen of us from the Naval Academy Postgraduate School at Purdue for this course. We all did very, very well. I think, as I mentioned earlier, out of the first of thirteen students in the industrial engineering class, we were twelve of the first thirteen. Purdue then had a rule that you didn't have to do a thesis in the master's course if you averaged eighty-five or above, so every single one of us averaged eighty-five or above. We weren't about to do a thesis if we could help it.

Purdue University furnished quarters for us. In fact they gave us low level faculty quarters, which were on a converted chicken farm. All of the quarters were made out of tarpaper and battens, but it was a place to live. There weren't too many places at that time. Purdue was flooded with GIs going to school in 1947-1948.

When I graduated in June 1948 it was back to sea duty. I received orders as gunnery officer of the DAYTON, a light cruiser CL105, which was then in the shipyard at

Philadelphia. We took the DAYTON out of mothballs and took her to sea for trials. She passed the trials. But before we left the yard, the Navy Department decided to put her back into mothballs. So all of this work was for naught.

I received new orders in early 1949 to San Diego to Commander Carrier Division 5 staff. It was pleasant living in Coronado for a few months. The staff was small, about seven officers. The carrier division commander at that time was Rear Admiral Eddie Ketchum, who had been a jeep carrier commander in World War II. He was relieved by Rear Admiral Fred Boone, who later became the superintendent of the Naval Academy and a future four star Admiral at CINCNELM. The admiral helped contribute to the closeness of the staff by inviting the entire staff to eat in the flag mess with him. When Admiral Boone relieved the previous commander, we sailed out to the western Pacific where he assumed duties as commander of Task Force 77. The admiral visited and called on heads of state in the Far East as directed by the Navy Department. He also called on MacArthur in Tokyo.

Donald R. Lennon:

MacArthur thought he was a head of state at least.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, at least. It happened that another officer and I were trying to thumb a ride into Tokyo from Yokosuka at the time Admiral Boone was going to call on MacArthur, so he invited us to drive in with him. He had a car and a chauffeur. The other officer and I thought that maybe we would get to meet MacArthur; but about halfway into Tokyo, we had a flat tire. The admiral hailed another military vehicle because he had to make this appointment. The other officer and I were told to wait for him over at Admiral Joy's house after the tire was changed. Admiral Joy was a commander of naval forces in Japan at the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were left with the flat tire to repair.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, we were to get the tire changed, beat it over to Admiral Joy's house, and wait for him. Finally, Admiral Boone returned and we had a nice chat and refreshments with Admiral Joy and his other guests.

Among other places we visited was Bangkok, while Admiral Boone was Commander Task Force 77. We also traveled to Saigon, Phnompen, Seam Reap, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Seoul, Korea. Some of us played golf with Admiral Boone in Singapore and later in the Philippines two or three times. Boone was quite a dedicated golfer, so every time he came into port, he was looking for people on the staff who played golf. Both the air officer and I played, so we'd get to go on these trips with him. Finally, we returned to Coronado for a few weeks and went on vacation. Lo and behold, we got called back from vacation. The Korean War had started.

The staff left immediately aboard one of our carriers. We went up to Alameda, picked up aircraft from the air station there, and took off for Japan. In Hawaii, Admiral Boone was relieved and Admiral Eddie Ewing took over the staff. We continued to Japan first, I think to Sasebo. We were there a while. Then, our flag ship went over to South Korean waters, and our planes began supporting the U.S. Army and Marines in South Korea. At that time, they had been driven way back and were down in the southern end of South Korea.

One interesting event occurred later when we were in the Yellow Sea, way up in the northern part. A twin-engine bomber came off the mainland directly toward us. We were a hundred miles, I think, from land up there. It was picked up by our combat air patrol (CAP), and identified as a Russian twin-engine bomber. Our flagship started

tracking him. Everybody went to general quarters; and finally as the bomber approached the task force, Admiral Ewing ordered the CAP to shoot it down. It was shot down, and the destroyers in our force recovered the two Russians that were in it. I think they were really on a reconnaissance flight, not a bombing flight. The destroyers recovered the two pilots and brought them aboard.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they survived?

David L. Byrd:

No, they did not. They were both dead. The bodies were returned to Russia by the U.S. diplomatic corp. This incident never came out in the press to my knowledge, although there was no reason why not.

Donald R. Lennon:

In a situation like that, was there any way for the carriers to warn planes that they were getting in a. . . .

David L. Byrd:

Not a good way. If it had been our own aircraft we could have, but we didn't know which frequency they were on, and so forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, there was no way to warn them away?

David L. Byrd:

I doubt we even had a Russian interpreter aboard.

As the war went along, we supported the troops and our planes were involved in the invasion at Inch'on. We operated up and down the coast on the west side of Korea, supporting the invasion. It so happened that when I was on Admiral Boone's staff, the predecessor of Admiral Eddie Ewing, we had been to Seoul and to Inch'on. Therefore, we knew all about the lay of the land at Inch'on and the huge tidal currents experienced there. Inch'on had about a forty-foot rise and fall. When the tide went out, everything--unless you were in the inner harbor behind the gates or way out--ended up sitting on the

bottom. So as we were supporting the invasion at Inch'on, the staff knew all about Inch'on's tides and currents.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any danger of shore bombardments against the Fleet?

David L. Byrd:

No, none at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the North Koreans didn't have enough of an airforce to pose a threat either?

David L. Byrd:

No, we never had an air engagement to my knowledge. We had complete control of the air.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were much more secure where you were than the ground forces were on the land.

David L. Byrd:

The carriers were there as a platform for the planes. We sent in planes to support ground troops and to bomb various designated targets.

Donald R. Lennon:

At one time, correct me if I'm wrong, but didn't the North Koreans try to move gun emplacements up and down along the coast to fire at the American ships?

David L. Byrd:

I'm not aware of that. Since we were on a carrier, we were way out. We were operating at least sixty miles off the coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

I think I'm thinking in terms of a destroyer.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, probably. Well, I stayed out in the Korean War until roughly February or March of 1951, I don't recall exactly now. Then I was relieved to go back to Washington to the Navy Bureau of Ordnance. As was the custom at that time, if the Bureau of Ordnance had sponsored your graduate education, as they did mine, you were supposed to serve two tours of duty in their assignments. So I went back to the Bureau of Ordnance and served in the Shore Establishments Division. My industrial engineering degree from Purdue was the reason I was assigned to the Shore Establishment Division. At that time,

there were at least sixty shore establishments throughout the world that were under command of the Bureau of Ordnance: ammunition depots, ordnance manufacturing plants, test stations like Dahlgren, Virginia, and storage stations and loading docks of various different kinds of ordnance. So shore establishments were a widespread deal that was beginning to be consolidated at that time.

It was at that time also that the Bureau of Ordnance was getting into nuclear energy. The Bureau had people going to school. I went to New Mexico for a week of training in nuclear weapons. At that time everybody, including many senior officers in the Bureau, had to go spend a week out there. We had to learn what nuclear weapons were all about; because just subsequent to this, we opened the first Navy nuclear storage area at a depot in Virginia, under the Bureau of Ordnance.

After a full tour of duty with the Bureau--approximately three years--I was detached and ordered as commanding officer of what had been a destroyer, the CONWAY. It had been DD507, but by the time I was in command it was DDE-507. It had been modified to become one of the first destroyers especially fitted out for conducting underwater submarine activities. We had an underwater plotting room, which was new. The destroyers didn't normally have that. We had special weapons including submarine seeking torpedoes that searched for and homed in on submarines when they were launched over the side. I commanded the CONWAY for twenty-seven months, a longer than average tour for a C.O.

I relieved the former commanding officer in the Mediterranean in Piraeus, Greece, and we operated over there for part of a six-month period. It was normal for East Coast ships at that time to serve six months and then return to Norfolk for a six month period.

Then the ships would go back again to the Mediterranean for another full six-month period. We operated with a carrier task force most of the time as a screen; but on one occasion, the CONWAY was selected to carry a special electronic search party, which was really working for an intelligence organization. There were about twenty-four or twenty-five people who came aboard with all their equipment. The CONWAY was ordered on detached duty in Greece. We cruised from one Greek isle and one Greek port to another to get a different radio bearing on the Balkan states. The search party was listening in on radio conversations.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that during the period when things were pretty unstable in the Balkans?

David L. Byrd:

This was about 1954 or early 1955. We don't know exactly how they did. The CONWAY was just their transportation.

Donald R. Lennon:

And they really didn't share any information with you all?

David L. Byrd:

No, no, none at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these Greek islands you were stopping at?

David L. Byrd:

Yes, and Greek ports, too, in mainland Greece.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they aware that you were carrying an intelligence contingent aboard?

David L. Byrd:

Probably not. It wasn't even called an intelligence contingent. In fact, as far as we knew, they were Navy Department, but I assumed the information they were gathering was for the CIA or some other intelligence gathering organization.

Following this, and back to the East coast, I had a cruise down in the Caribbean, a training cruise. We had been into the Navy Yard in Charleston for overhaul followed by training cruise down in Guantanamo. At that time, Havana was still open to us. I was able to visit Havana, Kingston, Port-au Prince, and various other places on weekends

when we were not training. The deal at that time for destroyers was we worked during the week, but on Friday afternoon we were permitted to go to whatever port the captain selected for a weekend. Port-au-Prince, Haiti was a very convenient port to go to overnight from the training grounds. I made one trip over there. I believe our whole division, however, went into Havana at one time and into Jamaica. We made nice trips out of this training cruise. Whenever possible, I let my crew vote on the liberty part of the CONWAY was cruising alone.

Donald R. Lennon:

I assume that Haiti was much nicer than it is now.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, even then though you could see that it was a very, very poor country. Usually the things you could buy in Haiti were made out of old tin cans or stuff like that along the dock. It was a very, very poor country.

After I finished up my CONWAY duty in twenty-seven months, in 1955, I was ordered to my second Bureau of Ordnance duty. That was as the Bureau of Ordnance technical liaison officer in Pasadena, actually for the West Coast area. There I had occasion to call on the contractors that were doing work for the Bureau of Ordnance, and I provided the Bureau with confidential reports on what I thought the progress was versus what the contractor was telling Washington.

Before I arrived at Pasadena, I had asked to have my engineering officer aboard the CONWAY be my junior officer and assistant at this station; so the Bureau of Naval Personnel was good enough to order him. We made a compatible team. He was a mechanical engineering graduate from Purdue University where I had taken my masters. My assistant and I visited all the contractors, not only Navy, but Air Force and Army as

well where the Navy had some interest in the work they were doing. We just nosed around their contracts, got briefed on where they stood, and drew our own conclusions.

During this tour, we regularly visited the Air Force ballistic missile contractor at Ramo Wooldridge Corporation. As a side note, after my naval career, I went to work for Ramo Wooldridge Corporation, which was then called TRW or Thompson Ramo Wooldridge. This second Bureau duty was a very, very good tour of duty for me. I learned a lot. I don't know how much good it did the Bureau of Ordnance, but for me it was a very, very good period.

After that tour of duty, in 1958, I was ordered to the staff of Commander in Chief Pacific, CINCPAC, a unified command located at Camp Smith, Hawaii. I was assigned to Intelligence: my code was J-21, intelligence plans and policy. In this position, I made a number of trips to the Far East, and I was nominated a couple of times to attend and participate in the SEATO conferences in Bangkok.

In 1961, my twentieth year in the Navy as a commissioned officer, I took a good look at my career. I had made commander in ten years, and I had been a commander for ten years at that time. I had three children to educate, and commanders were paid ten thousand dollars a year in round numbers at that time. Four star Admirals made eighteen thousand. I think that was the top figure at that time, not counting allowances. So I decided to start looking around for a job outside the Navy.

I made a number of contacts with possible employers. It turned out that one of those contacts was one that I made as Bureau of Ordnance technical liaison officer when I was in Pasadena. His name was Charles Bartley, and he had formed a company called Grand Central Rocket, out in Redlands, California, which he sold to Lockheed

Propulsion. But Lockheed didn't restrict him in any way, so Bartley moved to Mesa, Arizona, and started a similar company, Rocket Power, Incorporated. He was not totally competitive with Lockheed who then made large engines at the company in Redlands. Bartley's new company made only small solid rocket engines that catapulted pilots out of military aircraft, as well as cartridge actuated devices, and some small space probes for research work. He made me an offer I couldn't resist and I signed on as the assistant to the president. I liked the work very well and solid rocket were very popular in the military days.

Assisting the president, I was a kind of jack-of-all-trades. I did a lot of things. One period, when the manufacturing department manager left, I became the manufacturing department manager for several months until we could hire another one. At another time, I recruited and hired a quality control manager. Later, I had to find an airport manager for the airport we leased from the city of Mesa, Arizona. Bartley eventually had some misfortunes; he had a heart attack and was forced to sell his company to a Cleveland-based hardware company. I continued on with the new owners for about two years, but finally decided the best thing for me was to move to a new position at TRW in Redondo Beach, California.

TRW at that time was a very large company and employed more than 14,000 people at Redondo Beach, mostly engaged in space projects. I moved into their propulsion division, known as ATD or applied technology division, where 2100 were employed. I became an assistant project manager working on a large CIA satellite project. Our piece of the project designed and made the maneuvering engine for the

satellite. I worked on this project for about two years and then on many other projects in the same division in succeeding years.

The last position I held was manager, project control, applied technology division. TRW had a matrix project system and I or one of my employees worked on most of the space projects won by TRW. These included NASA, Air Force, Navy, and Army projects.

Later, as time went on, the major effort in the applied technology division shifted from liquid propulsion engines for rockets to chemical lasers. Among these laser projects that my group worked on was the Navy's MIRACLE, a part of the so-called “Star Wars” program. It was the first large Navy laser with mega watt capability.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, is that the same technology that they use in medical lasers?

David L. Byrd:

No, it's quite different from that. These were chemical lasers, and usually combust two or more chemicals that provide a very high temperature plasma. They are a natural follow-on to liquid propulsion rocket engines. We used big mirrors, made out of molybdenum that were a yard across, to focus the beam through a three-inch-diameter hole. This was very interesting work. In total I spent fourteen years at TRW. I retired there in 1981 and have been retired ever since. I think that's about all I have to add, unless you have some questions.

Donald R. Lennon:

I asked them as we were going along; all the things as they came to mind, unless you have any other thoughts in retrospect concerning your career.

David L. Byrd:

Well, I have always thought about the ease in which I moved into industry. I had several offers when I put out resumes in 1961. I could have gone to half a dozen places. I always thought that it was primarily due to having a good post graduate education,

having gone to the Navy Post Graduate School, and a masters degree from Purdue in engineering.

Donald R. Lennon:

That engineering background I'm sure was very attractive, too.

David L. Byrd:

Yes, I was never unemployed for a single day. Even after I retired, I got numerous requests to come back to work for a period of time primarily to work on start-up project teams or on new technical proposals. Typically, these were seven-day-a-week, twelve-hour-a-day jobs, and while interesting, they were not compatible with retirement.

I have never regretted the time I spent at the Naval Academy or in post graduate school. It helped me a great deal, I'm sure.

Donald R. Lennon:

It sounds like you had a good combination of sea duty and shore duty in your career.

[End of Interview]