| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #175 | |

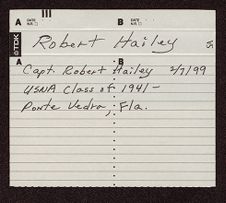

| Capt. Robert Hailey | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| February 7, 1999 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by Don Lennon | |

| Edited and proofed by H.A.I. Sugg and Susan Midgette |

Donald R. Lennon:

Give us a little background on your upbringing, etc.

Robert Hailey:

In 1935, I graduated from Big Spring (Texas) High School in a class of about one hundred. I then went to McMurry College in Abilene, Texas, for one year. It was a Methodist school associated with SMU [Southern Methodist University]. The enrollment was around nine hundred students. During the fall, I worked as a salesperson and general flunky at an upscale men's department store. After Christmas, that job folded, and I started working for an insurance company selling home insurance, farm insurance, and so forth. I had a very pleasant time working there with a wonderful boss, and finished up my year at McMurry. I believe you have a diary for that year.

Donald R. Lennon:

We have the diaries beginning in 1935 and 1936.

Robert Hailey:

Right, so I won't go into much detail. I was in debt by the end of the school year, so I laid out of school and worked for the National Oil Well Supply Company that summer in McCamey, Texas, which was located in the oil field south of Pecos. After a

couple of months I was transferred to my hometown of Big Spring. In fact, I was working for them in both places. I was doing a lot of painting on the outside equipment--oil well rocker arms, etc. But because I was not a very good painter and because I wasn't as attuned to the activities in the warehouse as I should have been, I was fired from that job and replaced by a college graduate from TCU [Texas Christian University]. This was at a bad time of the year. Everybody was looking for a job.

And so, in the process, I just happened to decide that I would go to SMU in Dallas to see if I could find enough work to resume school at SMU. I hitchhiked as far as Colorado City, a little town about forty miles from Big Spring. I needed another ride, so, as long as I was there, I took time to see the congressman who lived in Colorado City, . . . George Mahan, a very fine gentleman. I enjoyed talking to his male secretaries. I had previously requested an appointment to West Point. I could see that it would be a good way to get an education without having to pay for it.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you had been thinking about service academies prior to this time?

Robert Hailey:

Yes, I was in Boy Scouts. I had spent a lot of time in Boy Scouts. I was an Eagle Scout of the Gold Palm. At one of the camps, we had a retired Army captain who had gone to West Point. He had impressed all of us with his routines and his stories. So, on that basis, during the summer I was away from McMurry, I had requested West Point. That's the reason why the people in the congressman's office remembered and knew me.

At any rate, I went on from Colorado City and got another ride as far as Abilene, where I had been in school, and I visited the office where I had previously worked. By chance, my father called that office and got me while I was there. He said that he had heard there was a job in Colorado City that I might be able to get. Well, it sounded

attractive to me, so I went back to Colorado City. The youngest of the secretaries in the office, who was almost my identical age, drove me out to the Shell Pipeline Corporation office, where they wanted a secretary for office work. Well, I knew a little shorthand and I had taken business arithmetic, so I knew a little about business. I got the job, which was a remarkable job at that time. It paid $110.00 a month, which was quite unique in 1936. Perhaps I got the job because I had this secretary with me. I had kind of an endorsement I wouldn't have had otherwise.

While in Colorado City, the senior secretary took it as his own personal goal to get me in one of the academies. There was no appointment available for West Point. When the next year came around, there was an appointment for Annapolis, so I said, “Okay, I'll give it a try.” I got a second alternate.

The secretary told me, “Don't worry. We know the primary alternate. He doesn't want it. He's not going to take it. It's a political thing we've given him. We're not sure about the other one.”

Well, the first alternate didn't qualify. I did qualify. Because I had one year at college, I didn't have to take any exams, but I did have to take a physical in Dallas. The doctor there very strongly indicated that because I had a false tooth, I wouldn't qualify physically. I sent a message to my congressman saying, “It looks like it's not going to work.” The senior secretary came back and said he had contacted the surgeon general and not to worry about it, to come on up.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Naval Academy didn't take people who had a tooth missing?

Robert Hailey:

No. The doctor there was under that impression. He was a military doctor, and I guess he was reading it wrong. At any rate, I did make the trip to Annapolis. They said

nothing about my tooth at all. It was fine. I have a false tooth in the front. So I made it without any problems.

Donald R. Lennon:

You have diaries that cover your Annapolis years, but are there aspects of your life at the Naval Academy that you really didn't get into your diaries? Do you have recollections of that?

Robert Hailey:

I don't know if I expressed it adequately, but I was extremely fortunate that I knew some wonderful people in the Navy. There was a Navy lieutenant commander that came from my hometown. He was very gracious and very generous with his time and helpfulness.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was he an instructor at the Naval Academy at that time?

Robert Hailey:

He had been at the Naval Academy. He happened to be in Washington at the time, but I still saw him periodically. The congressman's secretaries were down quite often. I'd invite them down. I don't believe the congressman made it, but his secretaries were there. Then, at Christmas time, I would stay with them in Washington at the house they had. So it was a wonderful relationship.

Later on, I had contact with a man who was a relative of a family member in Texas where I lived. He was a chief pharmacist's mate who traveled with the President continually. Ed Numbers was his name. He liked coming down. I forget just how we made the connection, but we did. Later on, I got to know and visit him in Washington periodically. It was just a nice relationship. Later on I met the girl in this family that he was related to back in Texas. We had been classmates when I was in elementary school.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't that far from Texas to the coast after all, was it?

Robert Hailey:

Fortunately.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the instruction at the Naval Academy? Do you have any observations on that?

Robert Hailey:

Well, I felt that the instructors were kind of remote. I was not accustomed to that. At a small school, you knew all your instructors; you worked with them, and they helped you out. I had a lot of trouble with math and physics. Jack McCain, incidentally, was the instructor in physics. Quite a character. I later came to know the McCains through my wife. They were very close friends of my wife's parents. Actually, when I had a Scout Troop in Norfolk, his youngest son was one of my Boy Scouts. So we came to know the family well, but at the time, he was a rough, tough, cigar-smoking physics teacher. For the most part, I think, the instructors were very knowledgeable and very good, but of course it was hard to get any help from them.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lot of it was rote memorization, was it not? And you had to teach yourself a lot of it.

Robert Hailey:

Well, I think so and, of course, the idea was that you were on your own. I think that was very evident. The only exception was in the Language Department. I made a mistake. I spoke Spanish . . . I knew Spanish pretty well when I went there, and I had studied a year of French in college. I made the mistake of taking Italian because I wanted to go into another language. Because Italian and Spanish are so close, I kind of got them mixed up from time to time. My Italian teacher understood and was pretty nice about it, but it didn't help my grades much. I should have stayed in Spanish.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's a sure thing there!

Robert Hailey:

I did fine in language, English, and history. It was just that the sciences gave me a little trouble.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know that a lot of class members commented on hazing and their experiences with the upperclassmen. What about that?

Robert Hailey:

It was not unexpected, not unlike some of the hazing I had in college. So perhaps I was just attuned to it, and it didn't bother me too much. I guess I found ways around some of it. I had a couple of good first classmen. George Bourland from Texas was one of them; Al Church was another one. A couple of really fine individuals. I think they eased it over pretty well.

Donald R. Lennon:

How about extracurricular activities?

Robert Hailey:

Well, I'm not much of an athlete. I've tried over the years to be. I was kind of lightweight for football in high school. I tried out for it, and after finding that I could only use castoff equipment, which always failed to protect my knees, and after all the skinned knees I had, I just wasn't able to do too much in high school. I did try out for track. I wasn't very fast. As for baseball, I never could seem to be able to judge those high flies.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sounds like me.

Robert Hailey:

So let's say I never starred in the Academy. I did go out for plebe crew and was able to stay with the crew for the full season, but I was not good enough to go to varsity. I did run cross country. I enjoyed that and did it for several years. I enjoyed working out in the gym. I did a lot of that and a lot of swimming. I was not participating in the battalion sports except with the running. I guess I wasn't really a “radiator squad” because I did try to participate. I did keep busy and active. I enjoyed rope climbing, running, and doing some acrobatics--working on the bars. But I never got into anything very special.

Donald R. Lennon:

Anything else about the Naval Academy years that stands out in your mind that didn't make it into your diaries?

Robert Hailey:

I think the diaries show most of it. I enjoyed the cruises and found some real challenges in them. I enjoyed the people I met . . . and the opportunity to say, “No, I've had enough.”

Friends came by to see me from time to time. One very, very close friend, who has been a friend since about the sixth or seventh grade, was at another school in Abilene. During the summer, he would bring a Bible crew--a crew to sell Bibles--up into the area, so I saw him a couple of summers. We've been very close over the years. It was a great experience just to share with these friends from Washington. Other friends would also drop by from time to time.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you graduated, you were assigned to the INDIANAPOLIS. Were you at Pearl Harbor when . . . ?

Robert Hailey:

No, my ship got under way on Friday.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you just missed it.

Robert Hailey:

We were about 350 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor, anchored off Johnston Island. The particular reason for our trip was to take some of the first Higgins boats ever delivered, landing craft. We had, during the summer, made several attempts to go ashore on some of the islands, using our motor whaleboats. Every time we got them close to the shore, we found that the sand would clog up the circulating water pumps. The motor whaleboats would not work. The Higgins boats were designed for surf work and had well protected propellers and screening for the water pumps.

The INDIANAPOLIS was a heavy cruiser with a vice admiral embarked. For some reason, we were chosen to go to Palmyra Island and do some landing in the heavy surf there. We had some surf experts aboard, civilians who knew Palmyra Island and had experience with making a landing through the surf there. I had the A (Auxiliary) Division and my engineers were responsible for the maintenance and operation of the engines on all boats. This meant that I was very much involved and anxious to insure that the boats would always operate properly. .

Donald R. Lennon:

Describe the Higgins boat.

Robert Hailey:

It's a flat-bottom boat.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wooden construction?

Robert Hailey:

Yes, and it had to have a drop front, the ramp. The main thing, which was important, was that a shallow draft could get up high on the beach. It also had a protectant propeller that was protected in the well and also had protection for the pumps.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a vessel was it?

Robert Hailey:

The first ones we had would carry twenty to thirty people, I think. Later, they developed much larger vessels. We were at anchor and had all of our boats in the water, and some of them were ready to go ashore when the first word came. I have this recorded in my diary, “PEARL HARBOR'S BEEN ATTACKED!” You also have the report on my INDIANAPOLIS experience. So we were told immediately to recall our boats. We got underway and began testing our war allowance anti-aircraft ammunition. It had a time fuse exploder mechanism which was set mechanically. We would put the shells in a rack where a time to explode would be set, then load them into the guns. It

was a very slow and not very accurate process, but even that process was thwarted by their poor performance. In fact, we didn't have any explode in the air like they should.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sounds almost like the torpedo problem.

Robert Hailey:

Absolutely, it was terrible. Of course, we did fire some of the main battery, the eight-inch battery. Our first interest was to stay clear of what might have been the attacking force, wherever they were. We were south and didn't know they were north. We thought they could have been south. At any rate, a couple of days later, we joined up with the LEXINGTON battle group and stayed with them. About a week later, we went into Pearl Harbor and offloaded our old ammunition. We “stripped ship,” which meant that we got rid of practically everything that we didn't need. We got rid of dress uniforms, civilian clothes, record players, sports equipment, etc., putting them in cruise boxes. Mine were ultimately shipped back to my parents in Texas, and they did get there.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you did not keep any of your dress uniforms at all?

Robert Hailey:

We were supposed to get rid of everything that we did not absolutely need. We took down the curtains in the wardroom and any curtains that were around any of the portholes. I had to get special permission to have a radio phonograph so that we could keep some of our records. I was living in a bunkroom. I think we had fourteen officers living in a small bunkroom. There were some exceptions given. Mostly, we had to get rid of anything that was flammable, anything that might possibly cause difficulty, and anything that wasn't necessary. So “stripped ship” was quite an affair. We went to a lot of effort there.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that you offloaded the defective ammunition. Was there still a supply of new ammunition at Pearl despite all that was lost?

Robert Hailey:

Yes. On board we had what was called a war reserve. We weren't supposed to use it. We had ammunition that we used for training purposes that we were sure worked. But the war reserve did not work. We went in and offloaded it immediately, and they did bring in some more effective, good ammunition. Of course, a little later on, less than a year later, we got proximity fuses, which made a big difference. But, initially, we were using the mechanical fuse.

Donald R. Lennon:

And those mechanical fuses with the time sequence set . . . they might go off . . . it was just a simple or, more or less, a calculated guess as to how fast they would reach their target, was it not?

Robert Hailey:

When under attack from enemy aircraft, the range would be determined by range finders, or, later by radar when installed, and this range was sent to the mechanism which set the seconds required for that range. This was automatic when control was from the director. If local control was needed, the range would be estimated and the time would be set by hand. The same was true for the pointer and trainer. If the director was in control, they would match their instruments to the setting transmitted from the director. If in local control, the guns would be controlled by the pointer's sighting on the plane.

Donald R. Lennon:

Still, a lot was left to judgment.

Robert Hailey:

There was a lot left to adequacy of equipment, time lag, and so forth. We were at the mercy of a lot of little inadequacies. We had been at war readiness every time we had gotten under way. We'd darken the ship and quite often we were in Condition II, just to prepare us. We had started this, maybe in March, when I first reported aboard ship. So I think the Pacific Fleet knew that something was coming, and they were doing everything they could to prepare us for it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Except being careful with how they handled their Fleet.

Robert Hailey:

Well, that and knowing something about radar. Had they paid attention to radar, they'd have been fine . . . or at least probably a lot better.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you “stripped ship” and reloaded the ammunition, where did you go?

Robert Hailey:

We started operating again. We made a feint toward one of the islands--I can't remember the name of the island now--down toward the equator. We made a feint down that way. We were going to take the carriers down and make air strikes. Before we got there we thought we were subject to a couple of attacks by submarines. Upon arrival in the area we were advised that the targets we had expected weren't really there, so that was aborted. We came back to Pearl and the next trip we took was down to the Solomons. One other carrier task force did make attacks on the Gilbert Islands during this period.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this early 1942?

Robert Hailey:

This was January thru March of 1943. Our first action occurred when we were headed for a strike against the new Japanese base on Rabaul on New Britain Island. We were north of the Solomon Islands when we were spotted by two four-engine Kawanishi bombers, which were being used as scout planes. These were shot down but were followed later in the day by two waves of nine twin-engine bombers, which we called Betties, which attacked our task force. Their attack was met by our fighters, which disrupted their attack so that only one plane, which crashed near the destroyer PATTERSON, caused limited damage. Another plane tried, unsuccessfully, to make a suicide attack on the carrier but crashed into the water, well clear of the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

That early in the war?

Robert Hailey:

Yes. This plane had been hit, so he was coming down anyway and he was going to do his best to do some damage. We were on the starboard quarter of the LEXINGTON so the plane came directly across our bow. It was fascinating as he came. He was flying about one hundred feet off the water, and you could see the shells from the LEXINGTON practically pouring into it. There were big pieces of fabric flying off the plane. We could see the pilot sitting in his seat there, very erect. It was a very graphic situation. It looked like a solid sheet of flames going into him. The plane just kept going until it was almost, I'd say, within five hundred yards of the carrier and then he dove into the water. It was a very interesting situation.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's a wonder he didn't go after the INDIANAPOLIS, since it was closer.

Robert Hailey:

We were on the quarter . . . I'd say a couple of thousand yards. He did cross our bow relatively close--two thousand yards is close at sea--but the carrier was a big target. That was the target they wanted to hit. We were very fortunate.

Donald R. Lennon:

Take out a lot of planes?

Robert Hailey:

They were able to get him down before then. This was the time Butch O'Hare (of O'Hare Airport in Chicago) was credited with five Betties and became the great hero of the day. After that, the attack on Rabaul was discontinued and we returned to the Coral Sea where we joined another task force for an attack on the Japanese forces landing at Salamau and Lae on New Guinea. Our planes were launched from a point south of Port Moresby and then flew overland to make their attack. They sank a number of transports and other shipping. It was after this attack that the INDIANAPOLIS returned to Pearl Harbor and then went on to Mare Island for the repairs we needed.

Upon completion of repairs and installation of new radar, we then took a division of troops to Melbourne, Australia. We had several of the Matson liners with us, including the MARIPOSA and the LURLINE, along with seven or eight other troopships.

Heavy weather had caused damage to our bow and repairs were expected to be made in Pearl Harbor, but once we had been dry docked it was decided we should go to Mare Island for repairs. Upon completion of repairs, we then escorted a convoy with a division of troops embarked. We had several of the Matson liners among the eight or nine troopships in the convoy. Depth charge racks had been installed on the afterdeck of the ship. We had no sonar, so I don't know what we would have done with the depth charges. If we'd had a submarine attack, we'd have just gone in the general area, guessed at it, and dropped a few depth charges. That is all we could have done. Now, that was interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the heavy cruisers were not equipped with sonar?

Robert Hailey:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

Nothing larger than a destroyer at that time?

Robert Hailey:

Right, at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

And no radar on there either?

Robert Hailey:

Actually, we had radar installed during our first stop in December. We had what we would call a “bed spring,” a huge SV radar, which was a long-range search radar. Actually, it turned out to be one of the best ones ever installed. It would pick up aircraft and land at great ranges, but it wasn't very good for close ranges and bearings. So we did have that radar. Sometime during this period, we got fire-patrol radar. I do not

remember when that was installed. It could have been when we were in San Francisco, or we could have had some of it a little earlier.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you sent to the Aleutians after you dropped off the troops in Australia?

Robert Hailey:

No, we went back to Pearl after a brief stop at Samoa. Interestingly, we had a classmate come aboard. He was in the Marine Corps. He was wearing his captain bars while we were still ensigns. We kind of shook our heads at that routine. Of course, we made jgs a little later on, and, by December of 1942, we were lieutenants. We had a brief stop in Pearl, then went to the Aleutians.

Donald R. Lennon:

And what transpired with the ship in the Aleutians?

Robert Hailey:

I had been transferred from engineering to assistant navigator. It was primarily running in and out of Kodiak, Alaska. We made a stop in Dutch Harbor. We wound up going into Cold Bay, on the Alaskan peninsula, and we just roamed back and forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this before the Japanese hit?

Robert Hailey:

We tried to anticipate. We had heard that they were going to land in Kodiak. That's one of the reasons we were up there with the task force; to prevent any intrusion of the Dutch Harbor or further east. We spent the first part of our time in and out of Kodiak.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this late 1942?

Robert Hailey:

This was mid-1942. In late July we headed for Kiska, one of the two islands occupied by the Japanese, for a bombardment, but a fog kept us from being able to approach the island. It was August 7 that we were able to conduct the bombardment. We had good visibility and had our planes over Kiska to try to observe our fall of shot. Unfortunately, their fighter aircraft prevented our planes from observing the target, and we lost one of our planes and its crew.

In September, we escorted a motley group of ships carrying supplies and troops to Adak, where a forward base was established. During this time we were primarily just west of Adak, right on the International Dateline; we were steaming back and forth across that everyday.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why do you call them a “motley” convoy?

Robert Hailey:

Because they had used fishing boats, schooners, and anything that was floating. There were not many Navy ships or cargo ships of any kind available. They just used a strange aggregate of ships to carry supplies and troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, at least it was summer. It was the best time of year to be up there rather than the winter, when the weather was impossible.

Robert Hailey:

Well, we were up there in the winter, too. Those were pretty brutal times.

In the meantime, we had one incident where a man fell overboard. I think I recorded this in the diary. We were steaming about two thousand yards to the stern of one of the ships. They were having a drill of some kind and he misstepped and fell overboard. All we had to do was slow, drop our ladder over the side, stop, steam up to him, and pick him up. It took maybe five to eight minutes. He had on a life jacket and heavy, foul weather clothing. It was amazing how, just in that brief time, his hands were actually bleeding from the cold. His skin had split, especially in between the fingers, and he probably wouldn't have survived another ten minutes in the water.

Donald R. Lennon:

And this was during the warm weather?

Robert Hailey:

Well, the water was not warm.

Donald R. Lennon:

The water never gets warm up there.

Robert Hailey:

It was about twenty-eight degrees.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this the incident that you received the Navy Marine Corp medal for?

Robert Hailey:

No, that was later. But we had interesting times during the occupation of Adak. I think I recorded the account of one of our observers ashore on the island of Amchitka, which was near Adak. During the preceding day, the Japanese had a couple of float planes try to come out and observe us. There were no friendly fighters to send after them, but we would fire at them to drive them away. Amchitka had no anti-aircraft defenses at this time, so the Japanese plane would drop bombs and strafe our forces. One of their bombs killed a soldier and our observer was among the observers who were attending the funeral services. About the time they were ready to drop the coffin in the grave, all of a sudden this little plane jumped out of the clouds. Our observer said that was the first time he had ever been to a funeral where all the mourners were in the grave and the body was out of the grave!

At any rate, we did get involved, and had a couple of opportunities to bombard Kiska, and that was it.

We had aboard a very interesting man who was our pilot, an Alaskan pilot, and “Squeaky” Anderson was his name. He owned a fishery up in the area. Squeaky Anderson was great. He used dry humor. Nothing seemed to faze him. We'd be in heavy, heavy fog, and going in for a bombardment, and he'd say, “Go on in, it'll be all right. The fog will lift soon.” Sure enough, he'd be right if we'd just listen to him. One day he was up on the bridge and said, “Yeah, I think the wind to be about thirty-five knots.”

And I said, “Now, Squeaky, how on earth do you know the wind is thirty-five knots?”

He replied, “I know. I open my mouth, and snow blows in my mouth and out my 'arse,' so I know it's thirty-five knots.” Squeaky was full of stories. He later charged the beach during several landings down in the south and moved up. Later on he was beach master for several landings in the South Pacific. I don't recall which ones, because I wasn't involved in those. In March we returned to Mare Island for an overhaul.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would this be March 1943?

Robert Hailey:

1943, of course.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now in your diaries, the ones we have, I believe there is a break starting in November of 1942. Did you not keep diaries in 1943 or the rest of the war?

Robert Hailey:

I'm not quite sure why I broke it. Maybe it had just gotten so routine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Unless I'm mistaken, they run from 1935 to November 1942, and then they pick up again around 1949.

Robert Hailey:

Well, it was just kind of routine up there. We would be steaming, just a normal steaming, back and forth and back and forth, and did not see any action and had periods of bad weather. There was a little bit of interest here and there. In the meantime, I was the assistant navigator for a lengthy period of time. Then around November or December, I was transferred to gunnery and was in charge of turret number two, which was the high turret of our three 8-inch gun turrets. This gave me a new watch routine. I had more time to write, but as gunnery officer I was kept pretty busy with watches. We would have to sleep in our turret every other night and, I'll tell you, that turret would have ice on the interior.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the middle of the winter, the turret must not have been a very comfortable place to sleep.

Robert Hailey:

It wasn't, although they had heaters in the area where the guns were, and the people who slept in there were fairly comfortable. I had a small heater, but it couldn't do much good because I had all the exterior bulkheads, which had ice form on them. So I'd be bundled up pretty heavily. We had a little small kind of a calculator. With this thing we could generate problems and make solutions if we had to for local control. So we would concentrate our time working with our control deep down in the heart of the ship, or else with one of the sky controls. We would generate problems and see who could come up with a solution the quickest.

Donald R. Lennon:

The weather never got so bad that the guns or the turrets froze or anything?

Robert Hailey:

No, we kept them all functioning. We had one very bad storm in the Gulf of Alaska, where a destroyer had its main mast unseated. It started to flop back and forth. We were very worried about that. That ship could have turned over and had further problems. We sustained some damage to our bow again. We had a very weak bow. That's why we went back in March to the shipyard at Mare Island for overhaul. I was able to get Evelyn there to marry her at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, okay, that's when you came back.

Robert Hailey:

March 1943.

So that's the second time that the INDIANAPOLIS had been in for overhaul and repairs.]

Well, the first was emergency repairs. It wasn't a full overhaul. This was the first full overhaul we'd had, so it gave us some extra time there. It was during this time that the SALT LAKE CITY got involved with the task force up off the Komandorsky Islands and that area. We would have been involved if we had been there.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was early in 1943?

Robert Hailey:

Yes. We had gotten back there in time for the occupation and bombardment of Attu. Of course, the Japanese had abandoned Kiska by this time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is there anything about the bombardment of Attu that is noteworthy?

Robert Hailey:

Not from our viewpoint. It was very routine.

[END OF TAPE 1, SIDE A]Donald R. Lennon:

And from there?

Robert Hailey:

Well, I had been requesting a transfer to aviation. I had been kind of bored with this business up in the Aleutians. I was unsuccessful in that. My father-in-law was at Mare Island at the same time I was. He was preparing a squadron to go to Pearl Harbor. He later made the first Wolf Pack . . . took the first U.S. Wolf Pack out on patrol. He convinced me that if I tried for submarines, I would be more successful. It was around this time that I decided to apply for submarines, around June or July 1943. I was detached in September of 1943.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the INDIANAPOLIS operate in the Coral Sea while you were on her?

Robert Hailey:

We were there; we were in the Coral Sea. I had indicated around the Solomon Islands; that's the Coral Sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Ok. What about your saving two of your shipmates; when was that?

Robert Hailey:

Well, that was after our ship had completed its overhaul. We were doing a trial run off the Farallon Islands. We were doing a full-speed run, around thirty knots. We took a very limited turn, perhaps a twenty-degree turn. All of a sudden, the waves built

up, washed over our deck, and washed nine of our shipmates overboard. We reversed course and went back as quickly as we could. Some of the men were still in the water, and I went in the water to try to help recover the men. I was trying to get them on one of the propeller guards and the ship was rolling very, very heavily. I had hold of one of the men and ship rolled. And as it rolled, we were twelve or fifteen feet out of the water. I only had hold of him with one hand, and I could not continue to hold him. I regret it. He slipped out of my grasp, and, unfortunately, he was never recovered. He was a second class petty officer; a very outstanding young man. We felt very badly about losing him. We did recover five or six of these men, but some of them were lost. This was the incident; not one I'm very proud of. I didn't accomplish what I wanted to.

Donald R. Lennon:

I suppose, probably, it was a miracle that more men were not lost like that.

Robert Hailey:

That was a unique incident. They thought they were all clear . . . . The wave was just an incredible wave. It came over the bow and over the midsection of the ship and washed right between. They had a group of boats outboard of them. It just funneled right through there and washed them right to the aft deck and through the lifelines. It was amazing. But, the sea is like that. It has unique capabilities.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, it was warm weather. The sea there off California wouldn't have been that cold.

Robert Hailey:

It wasn't necessarily cold. But there were extremely high waves and high winds. It is usually pretty rough in that area. This was a problem. And, of course, when they went over, some of them could have been knocked unconscious and were not in the water when we came back around.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the ship put down a boat or did you just put on a life jacket and jump over?

Robert Hailey:

I didn't have a life jacket on.

Donald R. Lennon:

You just jumped over?

Robert Hailey:

Yes, I was a pretty good swimmer. They put a boat down, but when we first got to the people we had to get lifelines to them and try to help reach them that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was a tragic loss. You were detached from the INDIANAPOLIS in the fall of 1943?

Robert Hailey:

I was detached in September and temporarily assigned to a submarine refit group while waiting for transportation back to the States to start submarine school in January. The ship was going out on a long deployment. I stayed for a couple of weeks with the submarine group. I had experience with the combat information center, with the development of our center on the INDIANAPOLIS, so I knew something about it. I was sent over to teach in the combat information center area, to talk about development of centers, and to help set some up from the ships. So I stayed there until I was sent back to the States.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then your submarine training, and then assignment?

Robert Hailey:

I had three months of training in submarines. There were three classmates at the school with me, and, since we were senior lieutenants, we were all senior to most of the rest of the class. Upon graduation, two of us were chosen to remain in the area to report to training submarines. It was a great disappointment to me, but I did enjoy being with with wife. I reported to the R-16 as executive officer and qualified for submarines aboard before being ordered as executive officer of the R-5.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was it ported?

Robert Hailey:

The R-16 was in New London.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was Mrs. Hailey at the time?

Robert Hailey:

She was with me. We had gotten together as soon as we could and were living in New London.

Donald R. Lennon:

She was already in New London when you got there?

Robert Hailey:

No. I met her in Washington, and we went up to New London. We had a little one-bedroom apartment. It had one cabinet with a hot plate in it. It had a bed right alongside the cabinet, three feet from it. That was all the room we had. If we entertained guests, we would sit on the bed and play cards.

Donald R. Lennon:

Housing during the war period was not plentiful, particularly in military areas.

Robert Hailey:

That's right. At any rate, I went from there to the R-5 and down to Port Everglades, Florida. Of course, my orders all reflect this. In the meantime, we'd had a nice apartment in New London, but Evelyn decided to go back to Washington. Her mother was living in Washington, and, in fact, her father was there at the time. She stayed there for the birth of our first child. When our daughter was born, I got a ride to Washington on a B-26 and had a couple of days to visit.

I went back down to Port Everglades, operating on a daily basis, seeking to find a house in order to bring them down. Just about the time I rented a house and started working to clean up the yard and get the house painted and set to go, the R-5 was ordered to return to New London.

Anyway, just before Christmas, we made the trip back. It was a memorable trip. It was during December, and the water was very rough off Cape Hatteras. We practically flooded our control room. We had run the engines with the air coming through the hatch, and waves were constantly washing over the bridge. So we tried to have one foot on the

hatch, and when a wave would come over, we'd push the hatch down. We didn't want it closed too long or the engine would exhaust all the air in the boat, then we would cease to run, and we'd have to start up again. So quite often we'd open the hatch a little sooner than we should, and water would get down in the control room. So, it was getting pretty badly flooded before we finally got out of that weather. It was rough.

Donald R. Lennon:

Hatteras has done in a few ships.

Robert Hailey:

This was an old boat. It didn't have a lot of freeboard. We were about twelve feet off the water. We had what was called a “bathtub” there, just a round solid shield that held water. Then it had to go out through the deck. We would first get the wave over, then it would be up to our waist until it started to drain out. It was a wet, cold, miserable time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Both in Everglades and in New London, the submarine patrols were primarily routine by that time. The German Navy had . . . .

Robert Hailey:

We were not patrolling the area at that time. We were used primarily for training destroyers or carrying students from submarine school. We were in New London, taking them out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this also true in Everglades?

Robert Hailey:

When I was advised of the birth of our daughter, I was one hundred feet under water. They sent a telegram to our base saying that my daughter had been born. The telegram was then relayed by radio out to the ship we were operating with, and the ship used sonar to tell me. We were down to the depth of one hundred feet.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now how do you communicate by sonar?

Robert Hailey:

Sonar uses Morse code.

Donald R. Lennon:

I always think of sonar as being for distance. . . .

Robert Hailey:

Fleet submarines had underwater telephones and could communicate underwater by that means.

But we got back up to New London, and, on February 7, I took command of the R-5. We operated out of New London during that time. In September the war was over, and I turned the submarine over to the shipyard. They cut it up for metal. I have in my record, “Received from Lt. R. Hailey, one submarine, good condition.” It's kind of interesting, because my father-in-law also has a receipt for a submarine that he turned over for decommissioning.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was so much being done at that time, not only decommissioning, but, as you said, scrapping of the WWII vessels. What was your feeling, seeing this downscaling of the war machinery?

Robert Hailey:

Well, you must realize that in my case it was a feeling of relief that the war was over. I was delighted to think of going to Fleet submarines, which I did. My orders were to a Fleet submarine, and I knew I'd go to one immediately after leaving. And although it was sad to see the boats being cut up in dry dock . . . and I did observe a couple being dismantled and destroyed . . . but its impact was: “Well, we go on.”

Donald R. Lennon:

The R-Class was pretty much obsolete by this time.

Robert Hailey:

About 1917. They had been laid up alongside the pier in Philadelphia for a long period of time. The old Os and R-boats. An R-boat was special; we had a gun.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why, and this is complete ignorance on my part, did the R-boats not have names assigned to them like other submarines?

Robert Hailey:

They didn't start naming them until they started building a larger Fleet class.

Donald R. Lennon:

So during World War II there were named submarines, but it depended on class?

Robert Hailey:

Originally, submarines did not have names but were designated as A-1, A-2, etc., through the alphabet with O and R boats being built during World War I. The S boats, built after World War I were the last not to have names. When names were given the submarines, they also were given hull numbers representing the number of submarines built. R-5, for example was SS 82. The PIPER, which I commanded later, was given the hull number SS 409.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those were the ones constructed for World War II . . . .

Robert Hailey:

No, these were constructed in the early 1930s. They were the developmental submarines. Early ones were not very good at war patrol. They had troubles. Then they began to build the Fleet submarines, and they were very good. The first ones were not able to go the full depth that the later ones were able to. At the time the war came along, submarines with a test depth of four hundred feet were being built, as opposed to the earlier Fleet submarines with a test depth of three hundred feet.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they using R-boats primarily for training, or were any of them sent into the war zone?

Robert Hailey:

No, they made some war patrols in the Atlantic. They would operate off Bermuda and off our coast for a period of time there. I think two of them even had the chance to fire a couple of torpedoes, but nothing resulted. But still, it was an arduous type of control. At the beginning of the war with Germany, the British were effectively using submarines not unlike our S-boats to patrol off the coast of Britain and in the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

You would think in the North Sea, as problematic as the weather could be, that they would be more difficult, because, as you were talking about, the way the deck was constructed and everything.

Robert Hailey:

They have limited endurance, submerged. They have to surface to charge the batteries. So it is a problem.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, when you left the R-5, you went with the BRILL. Is that correct?

Robert Hailey:

After leaving the R-5, I went to Portsmouth as the prospective executive officer of the SARDA, which was under construction there. Following the commissioning of the SARDA, Chester Nimitz, Jr., was ordered to relieve the excellent commanding officer with whom I had been working for months to commission the SARDA. It was a disappointing situation but Nimitz had his own ideas about who he wanted as an executive officer. Shortly after the commissioning I received orders to the BRILL in Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have that you were on the BRILL in 1946 and 1947.

Robert Hailey:

Yes, I enjoyed that duty very much. I had a great skipper. We had local operations and made a trip up to the Aleutian area to see if we could operate in the vicinity of the ice. They were thinking of sending the ships under the ice and wondered what it would be like operating in that vicinity. We went north of the Bering Strait, toward Cape Lisbourne. We did find that the cool weather was a little bit difficult for us. The cold water meant that we had to use our heaters in the compartments to keep the submarine comfortable, but their use caused the exterior hull, which had inadequate insulation, to sweat badly. Although we had limited air conditioning, it could not be used to remove the moisture in the air, which gave us trouble with battery shorts and with

moisture causing other trouble with various equipment. This condition was of great concern and was one of the major things we learned during this operation. We did get close to the ice but sudden storm warnings and air surveillance indicated that the Bering Straits might be closed as the ice moved toward it. We had to abandon our push northward to avoid being icebound.

Donald R. Lennon:

I am not really claustrophobic, but I think I would be if I did more than walk through a submarine for about half an hour. When you're under the ice like that, was there ever any concern about being blocked in?

Robert Hailey:

You mean with the ice?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Robert Hailey:

Well, that's the reason we had aircraft flying out of Nome, telling us what to expect. We had forewarning of the possibility. That's why we did not get as far north as we had hoped to. We came back out of the Strait a little early. You know you have a very tender bow. The shutters for the torpedo tubes can be damaged by ice. So we didn't want to get caught.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, some of those submarines had awful thin skins anyway, didn't they?

Robert Hailey:

Some of the earlier ones, yes. It is the pressure hull. You can destroy your superstructure very quickly. That never really is very heavily reinforced.

Do you have a twelve o'clock appointment?

Donald R. Lennon:

No, no I don't. I have one at one.

Robert Hailey:

I'm going on and on, it seems like.

Donald R. Lennon:

You're doing great. Other than the experiments in operating under the ice in the Aleutians, what was most of the duty on the BRILL?

Robert Hailey:

Well, this was our only major operation. I was aboard a little over a year, and this trip took about two months. We left the Aleutians and stopped at Seattle on the way back in order that we could provide services for some ships and aircraft stationed in the area. Weather delayed our return to Pearl Harbor, making us one day late . . . so I returned one day after our first son was born. I always seemed to be gone and miss the birth of our children.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the BRILL duty, other than two months in the Aleutians, was primarily just local operations, training, and that type of thing, with no anticipation of having to meet submarines and hostility at all at that point?

Robert Hailey:

That's right. It was good living. We had just been put in a Quonset hut. It was adequate. It took a while before we could get all the equipment that we needed, because things weren't available at that time. We had a hot plate to cook on and finally got a roaster oven. A shipment came from the States and we were able to get one of those. That was a wonderful thing. We'll just say we enjoyed it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had more space than you did in your other apartment.

Robert Hailey:

Actually, we did.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, where were you between the time when you left the BRILL in 1947 and when you went to the FINBACK in 1949?

Robert Hailey:

I was ordered to the U.S. Naval Disciplinary Barracks in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where I was assigned as the classification and assignment officer. My staff of sixteen trained penologists processed all the prisoners who came there. My staff all had backgrounds in corrections and were correction specialists. Some of them were civilians and some of them were first class petty officers who had been trained as interviewers.

We tried to analyze the strengths of each of the prisoners who came in and put down the information. We got it together so that we had a classification board for each of the prisoners when they finished quarantine. They were in a quarantine period for anywhere from two weeks to thirty days.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of offenses had they been guilty of?

Robert Hailey:

You name it. There were brutal rapes, murderers, stealing trains.

Donald R. Lennon:

And these were all Navy personnel?

Robert Hailey:

Yes, Navy or Marine Corps. One guy stole a train over in Japan. One person we ran across had been in Israel and had provided arms for the Israelis. They paid him about $5,000 to steal some arms out of the armory, load them on a jeep, and run it out the gate. We had a wide variety. We had some very psychotic individuals. One man had been AWOL . . . we had quite a number of those . . . but this one man who had gone AWOL had been in a foxhole, and all his buddies had been killed when a shell hit. He had never gotten over the fact that he had survived out of the five that were in the foxhole. He became very psychotic and went AWOL. We had a psychiatrist, a chaplain, who was part of our staff. They always would interview these people and work with them as well. The Red Cross would go back to their hometown to get some background information, so we would know a great deal about them before I brought them to the classification board.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you're saying that battlefield trauma didn't originate with Vietnam!

Robert Hailey:

Oh, no. That's the way it went. At any rate, it was a very interesting job, but I found it very depressing. I would have to take off periodically. That's when I took up golf. That was depressing, too!

Donald R. Lennon:

You say that they quarantined them for a period. What was the purpose of the quarantine?

Robert Hailey:

Well, the quarantine was to evaluate them. The quarantine merely said, “You're not with the general population until we're ready for you to be.” We had three thousand there when I first arrived. It dropped down to about six hundred by the time I left a couple of years later.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the ones who were guilty of murders and rapes sent on to other prisons?

Robert Hailey:

Originally, we didn't do that, but we started to determine what the post-war situation would be. They determined that they would send all of those people to federal penitentiaries. So, we sent most of them to that type of institution. We recommended about eight percent of the people for restoration of duty: those who seemed to have made good adjustments in the prison and had indicated a desire to go back, and whose offenses were not significant to the extent that they couldn't possibly wipe them off the record. So, we sent a few people back. We sent quite a number to federal penitentiaries. Some of them got out on early release. So, it dropped from three thousand to about six hundred by the time I left.

This explains my continued interest in corrections. I've done a lot of work since I retired. I have gone to jails and helped to establish a group called Citizens Association of Justice in Virginia, which aims to improve the judiciary to some extent, but also to improve, overall, corrections programs. There was no such thing as rehabilitation in prison, really. You can help some, but it is doubtful that you can ever rehabilitate anyone in the prison environment. The judiciary and the alternative programs to imprisonment were the things that I was particularly interested in.

My next orders were to the FINBACK as executive officer. The commanding officer, Jim Green, was an excellent officer to work for and I enjoyed this duty. After a few months I was ordered to take command of the PIPER.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, with the FINBACK and the PIPER and all the submarines during this time, it was primarily training and preparation, was it not?

Robert Hailey:

Well, you will recall, I spent quite a bit of time over in the Mediterranean on the PIPER. You'll find that I was very much involved in helping to train the destroyers that were with me, the Sixth Fleet. And we had several operations that would go on--I say operations--“Fleet exercises.” You'd seek to attack the Fleet, so it was an interesting time. I enjoyed all my duties. Now, you have about all of the information on the PIPER that I can give you.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, that's covered in the ship's logs and in the diaries.

Robert Hailey:

After that, I went to the CINCLANTFLT intelligence staff. I was an intelligence production officer. I had a number of people under me, a good-sized staff. We produced intelligence reports and various supplements for operation orders. I was able to send one officer on a particular cruise. I helped to stimulate a submarine cruise off Murmansk so that we could get information on what it would be like for a submarine operating there during war time. While in command of the PIPER, I was advised that should war occur, I could expect to be sent to the area north of Murmansk for patrol. I could find little information on this area and was glad to be able to encourage COMSUBLANT to send a submarine there to determine operating conditions. I sent one of my Intelligence officers on this patrol, and he wrote an outstanding report. I also was permitted to send two Marine officers to Iceland to collect information we badly needed on that area. I also

became involved in planning for “Escape and Evasion” for aviators who might be shot down on bombing missions. I attended several conferences in Europe on these plans. I enjoyed the wide range of challenges this duty presented.

From there I went to this destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

That brings up an interesting question. Here, you'd had duty early on in heavy cruisers, but you spent most of your career in subs. That's quite a transition to a destroyer, is it not?

Robert Hailey:

Well, you'll notice most of the people stayed in submarines--those who were in subs and made war patrols--and they'd got divisions and squadrons. Since I had not had submarine war patrols, I felt that my time with submarines was pretty well expended by the time I got through with the PIPER. I didn't think I'd probably get a division or a squadron, because I had such good competition. I understood it and felt it was appropriate for those who had that background.

Donald R. Lennon:

And there are not enough submarines to go around?

Robert Hailey:

Well, I'm talking about divisions and squadrons now. Besides, I liked the challenge of the destroyers. I had worked with them quite a bit, especially in the Med. I had come to know a lot of the destroyer skippers, and I felt that anti-submarine warfare was the area that I wanted to concentrate on. So, I was delighted to get a destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you were able to see the opposite side of it. There in the Med, you had been trying to outsmart the destroyers.

Robert Hailey:

It was an outstanding opportunity. It turned out that way. Again, you have reports on some of my WALLER experiences. I think you have a pretty good report on that. Again, I felt it a very fine opportunity. Later on, I went to an anti-submarine

defense force. It was with anti-submarine work. I worked with the carriers and with the Fleet air wings and thought the continuity was very good there. Of course, I had, in the meantime, a couple of years down in the ROTC unit in Houston.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think that, having been on submarines, you would have a really first rate perspective for anti-submarine planning.

Robert Hailey:

It meant a great deal. I had operated with nuclear submarines, so that gave me another bit of information that I needed when I got on the destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

A couple of things that I do want you to comment on . . . In 1963, you were in charge of the investigation of the American mission burned in Caracas. What can you tell us about that?

Robert Hailey:

Well, as you know, Che Guavaro was roaming around the area, and Castro was trying his best to create problems wherever he could. I was making periodic trips throughout Latin America at this time. This was, I think, my second or third time in Venezuela. Each time I'd been there, I'd observed some of the problems that were going on. I talked to the mission people and the attachés, and had some understanding of it.

When this “mission burning” occurred, I was sent back to investigate and report to General O'Meara what the circumstances and the facts of the matter were. I didn't exactly please O'Meara because when I went back and investigated, I found that there was a little enclave inside of the overall area controlled by the Venezuelan military. They had guards at the gate, and they were responsible for the security, including anybody who came in. The overall area was supposed to be secure as well, not just this one locale.

Our U.S. military were forbidden to carry weapons. In their building, of course, they had their own security, but it wasn't really tight. They kept things locked and they

had someone on duty. The procedure was that, periodically, fresh food and things from the commissary or from the exchanges would be brought from Panama by plane into Venezuela. They would put it on a truck, bring it in, call all the people to tell them the stuff was there, and the crew would come in and pick up whatever they had requested and whatever was available. But, again, those were the normal conditions. At this particular time, the guards at the gate were overcome by these terrorists. They came in and people weren't expecting them, so they were easily taken. They embarrassed them by making the colonel lower his trousers and take them off. They just wanted to embarrass him. They tried to set fire to the mission. It didn't burn very much, but it created quite a flap, a lot of international information.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the Venezuelan army was not implicated. It was just sloppy?

Robert Hailey:

Yes, they were very sloppy. My finding was the thing that really upset the people. I went through a lot of details on it and found that the requirements were very clearly established by the Army general in Panama, approved by CINCSOUTH, General O'Meara. The security was fully the responsibility of the Venezuelans. The people who were in the mission had no responsibility and could not take certain actions, such as would be required if they carried weapons. The situation had been going on for a period of time. Two weeks before this burning occurred, the Army general and General O'Meara had both been through there and inspected the mission and talked to the people. They had no comments, no objections to what was going on. I considered that full approval on their part. I could not really blame the Army colonel. My findings were that this was a situation that would not call for any administrative action against the colonel or any member of the mission. They had acted as well as they could have, under the

circumstances, and they were not to blame. Of course, the general was, in effect, blamed by the implication. That wasn't exactly the smart thing to do.

I was called up on that, but I did not change anything. Nobody ever took any official action, except to indicate to me there were certain “necessary changes.” It is interesting when you're caught in the middle like that. I had no choice. I couldn't recommend forceful action. Of course, the general disagreed in his endorsement. I don't know what happened after that.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you don't know if there was any disciplinary action?

Robert Hailey:

Oh, I'm sure there was. I'm sure the colonel was relieved. I'm sure he never saw a good billet after that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of like the embassy bombing of more recent times. Then you became CO of the SANDOVAL. There may be some more things you want to comment on with the SANDOVAL, but I would like for you to comment on the allegations of discrimination against blacks, when you corresponded with General Shoup.

Robert Hailey:

I'm at a loss. I don't recall what you're saying.

Donald R. Lennon:

I came across a note where you corresponded with General Shoup, when he was Marine commandant, about a claim that black enlisted men were being discriminated against in the military.

Robert Hailey:

It doesn't even ring a bell right now, but if you've got a letter on that, the letter says it all. This type of allegation just came up again and again. I recall when I was at the disciplinary barracks, and I had two or three congressmen write about one of the Marine lieutenants who had been sent to us. They were just saying everything under the sun about discrimination: “Shouldn't have done this, shouldn't have done that,” but the

court-martial still stood, and everything was as it was. The question on blacks was not unusual.

Donald R. Lennon:

For that particular period, I would think that they were very sensitive to their rights.

Robert Hailey:

Well, if you want to come down to it, I felt a greater problem was the sensitivity of the Marines operating with the Navy. I had more trouble with the Marines aboard ship, including the lieutenant colonel who was in charge of them, than I did with any discrimination. I felt the crew operated very well. But the Marines, they could trash an apartment in nothing flat. We'd get ready to land, have the nets ready to go over the side, and be ready to send them in the boats, when all of a sudden, we would find that they'd taken the fittings holding the nets, they'd taken the bolts out of them and they would have to be replaced before we could do it. They would mess with the closing mechanism on our watertight doors. We'd have to replace that. It was just hard carrying people who had no real mission on board ship. They'd just get bored.

That stands out in my mind far more than . . . I don't recall any particular problem . . . this particular incident you've referred to I just can't remember. I had to send off a lot of letters to parents who said their son was court-martialed and this and that had happened. We'd have to placate them. There was one suicide on board. That was a very difficult letter to write. We had tried to work with this young man; he was quite a loner. The petty officers were aware of his problems and had tried to help him. I actually had to counsel the man on one occasion. We just couldn't be with him all the time. He had a key to a certain area where he had to work, and he used that kind of remote area to hang himself.

[End of Interview]

I would like to identify the men and officers who served with Captain Hailey on the R-5. I believe my father also served on that boat during that same time. Any help you can provide will be greatly appreciated.