| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

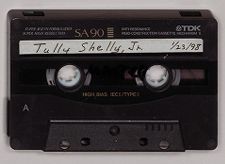

| Tully Shelley, Jr | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| January 23, 1998 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Being a navy junior, I know you were born in California five years after your father graduated from the academy.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

That's right. I never thought of it that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would you tell us something of your background and what it was like to grow up in a navy family?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I was born in San Francisco. I lived there until I was three weeks old. Then we moved to Seattle, I think. Life was sort of back and forth between the West Coast and Washington, DC. I spent early years in Coronado, California. I did not see much of my father because he was in China. He was in the class of 1915.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he ever talk about his period in China? That was an interesting period in China during the 1920s.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

He did not really talk about it. He was exec on the MARBLEHEAD. The only time I ran into that at all was years later, when I was in the MONTPELIER, and one of our coxswains had been on the MARBLEHEAD. I asked him if he had known my father. He said, “ Oh yes! We used to call him 'Old Ironass' cause he made us wear shoes.”

Donald R. Lennon:

The old Navy for sure.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We were in Annapolis when I was ten or eleven. We lived in the Academy's officers' quarters. He was exec of the Modern Languages Department and taught Spanish. One summer, we went to Santander for him to brush up on his Spanish, his Castilian accent. I remember that well because I was around twelve years old, and there was a revolution going on. We knew people on both sides. We watched the revolutionaries burn the library and the yacht club. There was one guy we talked to who was an aristocrat and he showed me inside his coat. He said, “If they knew I had this medal, I would be killed.”

When I got back to Annapolis, I was supposed to go into the eighth grade. They had built a new high school. Because of space available in the new school, they moved part of my class directly to high school; I never had an eighth grade. I started in high school when I was twelve. I had my first pair of long pants when I was a sophomore. Things were different then.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right, they were.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

What I remember from 1932 or 1933 back in Annapolis, was that my uncle who was in the wool business in New York was in very bad shape [financially] just like so many people were during the depression. My father was a lieutenant commander and had to take a twenty percent pay cut, but we were much better off than the civilians at that time.

Then my father was ordered to the RICHMOND, I think it was, which was in Havana. There were several ships there to protect the American interests back in the Batista Days. I think they called that group of ships the Special Services Squadron. That would be 1934.

I went to Annapolis High School for two years. At the beginning of the fall season, they moved the ships from Havana north so the kids could go to school. My father's ship--I think it was still the RICHMOND--went into St. Petersburg, so I went to St. Petersburg High School for my junior year, which was wonderful. It was a great school, easy laid back life. Then he was transferred again. I don't know where he went, but we went to Long Beach. My senior year of high school, I went to the Harvard School in Los Angeles. The Harvard School was an Episcopal military school with an excellent academic rating. Times were slow, so they offered half-price tuition and board to service sons.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, really.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Three of us who were in the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1941 were in Harvard School's Class of 1936: Charlie [Charles W.] Styer, Jack Alford, and me. That was more than ten percent of the class because there were twenty-seven in the graduating class.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you ever have any question as to whether you were going to the Naval Academy or were you mentally programmed that this was your career?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Not at all. I was an only child, and my mother was from Providence. My mother and father had the idea that I should go either to some place like Yale or make my own choice. But as an only child, I had a great desire to be independent, and my idea of being independent was to go to the Naval Academy. Getting into the Naval Academy just seemed like a way to make my own way!

Donald R. Lennon:

I am sure that pleased your father, also.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Yes. He tried to get me an appointment. I remember he wrote to Admiral Byrd. He tried to get recommendations to a senator to get me an appointment but none of that worked. He had been born in Washington, [DC] and had no state affiliation. So I was cast into the presidential stream. I went to Columbian, in Washington, as a bunch of my classmates did. I studied harder than I had ever studied in my life. I can remember that we did nothing but study.

We had all our ancient history on three-by-five cards; you would have Thermopylae on one side, and the other side you would have the dates and any other information. You would do all this stuff on the bus, on the way to school and back. The only recreation I had was shooting baskets in the backyard for an hour a day. But, I stood eighth or ninth out of the fifteen they took that year from the presidential group. There was something like 180 people that took the test. That was my crowning academic achievement.

When I started plebe year, my father was in Washington. At the Naval Academy, I roomed initially with Charlie Styer, who had been at Harvard with me. (Jokingly, I sometimes say I graduated from Harvard in 1936). I also met Joe Taussig (another Navy junior), and we did a lot of horsing around in our three man room.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know if you were with Joe Taussig, you did a lot of horsing around.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I think I was a little more serious than those two. Anyway, I guess it was our youngster year that we were all 'unsat' (failing), and they just said, “Okay, we gotta break this room up.” I said, “I'll go over to the 1st Bat and room with Harry Vincent.” I had been playing lacrosse with him and his roommate had bilged out, so that worked out very well.

My main loves at the academy were athletics. I played soccer for four years, not very well, but I was always on the squad. I got my “N star” because I got in the last two minutes of the Army game that we won. The main thing was lacrosse as far as I was concerned. I was one of the high scorers on the plebe team. In youngster year, I remember Dinty Moore, the lacrosse coach, saying, “To be on the varsity, you got to have two of three things: size, speed, and stick-handling ability.” I only had the third. So I was on the B squad, but I did pretty well. I remember his saying “Well, it looks like we are going to see you up on the varsity.” Then I went in and looked at my grades (grades were posted for all to see) and I was unsat [unsatisfactory] in physics which made me ineligible for athletics. That was third class year, but it set me back to the B squad second class year. When we graduated in February of 1941 because of impending war, I missed my first class year of lacrosse. It wasn't very important, but it was important to me at the time. Girls were also important then, too.

I managed to graduate at the top of the bottom quarter, but at least I graduated. They said we could apply for the type of ship we wanted. I thought, The bigger the better! I requested battleship, heavy cruiser, or carrier. I got orders to a destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Bad choice. That's the way the military works.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

There are a couple of anecdotes back at the academy. It was plebe year, Milo Draemel, who was commandant during our first few years, called us in and gave us a talk about what it means to be in the Navy. He likened it to the priesthood almost: “You will have a comfortable life, you are not going to be rich, but you will be serving your country . . . . ” I remember that very well.

Another time, he called me in personally. My father had been passed over for captain the first time around and he said, “This is just one of these things that happens. Apparently, he didn't know the right people on the selection board. Your father is an excellent naval officer. I really think you shouldn't take this too hard because he is certainly deserving.” Well, this was a hell of a thing to say to a young kid. My father was picked up the next time around. I am sure that had an effect on my attitude towards the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have any interesting encounters with Uncle Beany?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Not like Taussig. I remember him, but I don't think of any specific crazy things. I really never got into trouble, I was pretty square. I joined the drum and bugle corps when I was a plebe. My father started it in 1915 or was one of the organizers of it. As I tell people that I graduated from Harvard in 1936, I also tell people that I played before a hundred thousand people, which I did at the Army-Navy game in the bugle corps. That was a pretty good deal, because you carried only a bugle instead of a rifle. I quit that after the first year because I didn't particularly care for the guys that were in that group.

Donald R. Lennon:

No problems with harassment from the upperclassmen that plebe year?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

No. Nothing severe, not too bad. I remember all the memorizing, and getting your tail beat with a broom, but nothing that damaged my psyche or my body.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were assigned to the DRAYTON upon graduation, it was stationed in Pearl Harbor so you spent much of 1941 out in the Pacific.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We went out on the HENDERSON in March of 1941, a whole raft of us. When I went to the DRAYTON, it was in dry dock, so another classmate of mine, Jim Marion, and I just had a big time. He had been captain of the boxing team in our class. He was

in the same destroyer squadron, I guess, so we did a lot of liberties in Honolulu. We would go to the fights and just generally had a good time.

When I went to sea, which was before the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was the roughest I had ever seen the Pacific. I spent a miserable few days getting acclimated, but I never had a problem after that. I started out as an assistant engineering officer. During that period around Pearl Harbor, I spent a tremendous amount of time on an engineering course--drawing sketches of the evaporator system, etc. When I completed that course, I was qualified to be a chief engineer of a destroyer, and that is when they made me the communications officer. Another typical Navy way! The DRAYTON, do you want me to expand any on it?

Donald R. Lennon:

Please.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

L.A. Abercrombie was the skipper of the DRAYTON at the time. I have a tendency to do more anecdotal than I do facts.

Donald R. Lennon:

The anecdotes are what are important.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We were at sea with, I think, the LEXINGTON, but I cannot swear that that is correct, when I got the message of the air raid on Pearl Harbor--“THIS IS NO DRILL! THIS IS NO DRILL!”--which I took to the skipper. That was a memorable moment. Nobody could believe it. We were plane guarding and we went charging off with this carrier, probably in the wrong direction, because we didn't find any Japanese.

Donald R. Lennon:

You did not attempt to come back to Pearl Harbor immediately? You tried to intercept.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We tried to intercept, but communications were not great in those days. We went back into Pearl Harbor a few days later. What a devastating mess; it was hard to believe.

Shortly after that, we were sent on a single mission to escort a freighter to Christmas Island. I remember we were on our way to Christmas Island and it was Christmas Eve when we got a routine submarine contact. I was also torpedo officer. We went through the regular drill on depth charging and that whole thing. And damn, if the submarine didn't surface and sort of shudder and slide back. We could see the net cutters on the bow, and there is no way those guys could have survived. We went on to deliver the ship, and then went back to Pearl Harbor.

On our way into Pearl Harbor, we were attacked by a submarine. Lookouts saw the torpedo wakes, one was broaching and the other wasn't. They went right down both sides of the DRAYTON. That was real excitement. They said, “Stand by to ram!” We tried to get the five-inch guns down, because the guys up on the bow are the ones who actually sighted the submarine. We didn't hit anything. We dropped depth charges. The second round of depth charges didn't go off because we had moved to shallower water than the settings on the depth charges. We assumed that we sunk that submarine, but we probably didn't.

We went into Pearl Harbor, and the captain and the exec went over to Cinc Pac claiming two kills. They came back slightly inebriated, saying, “They gave us credit for one,” which was probably right.

I don't remember the sequence, but we went back to San Francisco at some point. I think maybe before that we put the Marines into Samoa. There were just two ships involved: the SAN FRANCISCO, which would patrol a certain number of miles out, and then the DRAYTON, which would patrol around the island closer in, while the Marines were being landed in Samoa.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were they being offloaded from?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I don't know. LSTs or something. I never saw them. The only thing we saw was one morning, at dawn, somebody said “I've got a target on the port bow!” We started training our guns around and went to general quarters. The officer of the deck said, “That's the SAN FRANCISCO! That's the SAN FRANCISCO! That's the SAN FRANCISCO!” Fortunately, we didn't fire. Later, I found the SAN FRANCISCO had had their guns trained on us, too. That was an incident.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the Marines were not on the DRAYTON or the SAN FRANCISCO? They were on other vessels. You were there to protect them and provide cover.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We didn't see any enemy ships. We were at sea for forty-five days, which I remember well, because we ran out of everything except dehydrated potatoes. We put into Suva. That was our first port after forty-five days at sea. Some of us got liberty. In the middle of the day, I remember going up this hill to some bar. One of the enlisted men said “Here have a drink.” I said, “ No, I am drinking straight scotch.” This was a glass about so tall, and he said “That is straight.” That is the last thing I remember. We staggered back to the ship. I don't want a posthumous court-martial here. Bill Benedict, Class of 1942, and I were sort of arm and arm, going down the dock. I never passed out or anything, I just lost my memory.

We had raided this peanut vendor, and we had all these peanuts stuffed into our shirts. We went on board ship, and I remember I just flopped down on my bunk. It turned out that somebody on the seaplane tender turned us in. They said there were a couple of officers from the ship that were not conducting themselves in a gentlemanly way. Our exec, whose name was King from the Class of 1937 or 1939, told whoever it

was on this seaplane tender that it couldn't have been anybody from our ship, because our people were all back on board by the time this guy said he had seen them.

What it was is that we hadn't changed our clock, which I am sure our exec knew perfectly well. I always thought of him as being a real hard nose, but he saved our skin. I thought much better of him after that. Then at some point, we went back to San Francisco which is when we hit the dock.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you came into San Francisco, who was conning the ship?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Abercrombie, who later wrote a book called 'My Life to the Destroyer'. I have a copy of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he just come in too fast or was it just lack of experience?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Well, it wasn't real bad. It was just a little misjudged. We just nudged it with the bow. To the junior officers it was an incident, but not a big incident. I guess that's when they decided to paint our ship an unusual color, which was a bright blue. It was an experimental camouflage job. Some of the men started calling the ship the “BLUE BEETLE.” Some got “blue beetle” tattoos. Abercrombie, in his book, refers to it as the BLUE BEETLE. Later on, as a civilian, when I had a boat of my own, I named it the BLUE BEETLE.

We did some maneuvering with the battleships--the big, old battleships--that were supposedly backing up Midway, but we were so far back it didn't mean anything. I think it was about then that I got my orders to new construction-- the MONTPELIER-- at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. I was a happy decoder of that order.

Before going to the new construction, however, I went to gunnery school in Washington. While I was at gunnery school, I called all the girls that I had known before.

I started going out more with Maggie, and that became the obsession of the moment. When I joined the Fleet, I was twenty years old, so I wasn't even qualified to drink.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were in your prime, though.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Taussig and I were two of the four or five youngest in the class. I think John Thro was the youngest. We were across the river from Philadelphia, and then we went over to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where they would tear everything apart that had already been done at another place and put it back together again.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned throwing the linoleum decking.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

That stuck in my mind. We were out on our shakedown cruise, having to rip up all this linoleum because of the experience they had with linoleum burning at Pearl Harbor. Well, hell this was 1943.

Donald R. Lennon:

Commissioning was September, 1942.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

1942. Yes, I suppose it could be blamed on the backlog of paper work and red tape and everything. But, hell, they knew perfectly well when they put it in that it was flammable and shouldn't be put in. But they had a contract to do it. So when we went up in the Chesapeake Bay, we were all scraping this stuff off and throwing it over the side. It was terrible. Environmentalists wouldn't like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say, now the Chesapeake Bay is floating with fifty-year-old linoleum.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

It made me realize there were some inefficiencies in the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you do? Get down to the bare wood beneath or steel?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Steel. That was inside, it wasn't on the outside deck.

We did gunnery runs and speed trials on the Chesapeake, shakedown cruise. We had this radar gear, which is a significant part of the story really, because we were the first ship with radar control main battery. After training within 15 degrees of the target, we could shift to radar control; it was the first time we had that. Well, it didn't mean anything to our senior officers because they were all out in the Navy Department and did not know what was going on in the war anyway.

By the way, the skipper of the MONTPELIER was Leighton Wood, Class of 1915, a classmate of my father. There were just four of us initially qualified to stand top deck watches: Norm [Norman W.] Ackley, classmate of mine; a fellow named Dean out of the Class of 1940; and a reserve named Bradley, and me. We'd all had experience during the war because we came from other ships. Actually, Ackley had gone down on the LEXINGTON. He was my roommate on board the MONTPELIER.

On the way out, nobody knew what to do with the radar. We had a jg on board who was a radar technician. He kept saying to the gunnery officer, “When are we going to fire some things with this radar control?” The gunnery officer would say, “Well, if we have any remnants.” I mean it was not important to him. Burdick, I think was his name, was so upset he went around mumbling, “Well, if we have any remnants.” We had the newest thing in the Navy!

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say this was the new and improved radar, rather than the old bedspring type.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Oh yes. The bedspring was the SC, and the SG was the surface radar. Finally, they decided maybe we better do something with this radar stuff, so they had a supply officer do a plot of the convoy as we went from Newport through the Panama Canal and

out to the Pacific. He had the sheets of paper, like what today would come off a computer, with these five lines (the ships) and their relative positions in the water. It was utterly useless, but we had to do something.

We got to Noumea, and Admiral Halsey's staff came aboard and they immediately were asking questions about this new radar gear. I guess even the SG was probably fairly new or improved. Everyone was a little bit embarrassed, so my boss, who was the gun boss, said we better find out about what is going on out here. He sent me over to a cruiser, which turned out to be the SAN JUAN. I talked to Vic Delano (a classmate), who was on board, about what was going on out here. He said, “A lot of our fighting is at night and you have got to be on top of everything with the radar. You've got to almost con the ship from the radar center. You better get a combat operation center.” Now, it is called a CIC, but then we called it a COC, combat operation center. He added, “You need to consolidate your radar information so that you can then broadcast it out to the gunnery control and the con and so forth. You've got to get priority on putting in a broadcast system, so that you have speakers at various parts of the ship where you can say that there are planes (bogey gadgets) coming in from such an angle and altitude.”

I said, “Well, we need to put somebody on this full time and get this done on a priority basis.” He said, “Well, who do you suggest?” I said, “Well, somebody should be relieved of all watches and spend all their time doing this. I guess I am the most experienced.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Anything to get out of watch.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I took that on, not realizing until years later when I became a management consultant, that that was my first consulting assignment. I recruited my radar gang, and

we set up a place in what had been an ammunition locker. I was a lieutenant and the chief engineer was a full commander. I told him that I had to have priority on these work orders and that really upset him. Anyway, it was sort of fun throwing my weight around a little bit to get something specific accomplished.

We got the broadcast system put together. In fact, it was just being tested when we were at the Rennel Island battle (January 29, 1943) and it proved to be timely. In CIC Admiral [A.S.] “Tip” Merrill was standing behind me. He was ComCruDiv 12. He was standing behind me while I was on a SG radar with phones to the SC radar and with my broadcast microphone--doing my thing as we were attacked by many Japanese Betties (torpedo planes). That is the night the CHICAGO was torpedoed. That was our baptism of fire.

Donald R. Lennon:

You earned your keep that night at the radar.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I earned my keep another time. When we went up to Kula Gulf (March 5 or 6, 1943) to do a shore bombardment at night, that was when we really used that new radar setup. There were two or three cruisers and some other destroyers running with us at that time. Anyway, we went into Kula Gulf and we had gotten some intelligence from some PBYs that there might be some Japanese ships in there. Everybody was “itchy finger on the trigger.” I was keeping track of our ships on the SG radar when someone in fire control said, “I've got a target on the port bow!” Thank goodness I was calm because I said, “That is one of our destroyers.” You never know whether you are going to be calm in combat or not. Fortunately, that was another ship we didn't fire on. We went in and did sink a couple of enemy ships in there and we did the shore bombardment. There was

a little pinnacle of outcropping in the harbor that we knew about and we offset the fire control solution from it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, with the radar you were using at that time, you weren't able to really identify what ships were around you.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

You just knew it was a destroyer.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Yes. For me, it was just a blip on the screen and I was just keeping track of what was where. We didn't have any identification. I did get a commendation for that particular action. That was the only action I was in on while I was on the MONTPELIER. There were some other anecdotes, but they were not as significant.

Donald R. Lennon:

Such as.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

There you go! Well, there were incidents that affected my attitude about the Navy. I was in the main battery division aft, which had the catapults for launching seaplanes. The seaplanes were not properly designed and one of them went in and the pilot and radioman were killed. They later determined that these planes (SOC 3s) were under-powered and overloaded. They were replaced by the older SOCs.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, the planes were at fault rather than the catapults?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Oh, yes. I was doing the catapult. All you did was wait for the roll to go up and then shoot them out. There was nothing wrong with the shot, but the pilot couldn't maintain altitude and so he just gradually went down. They went into the water and were killed. We had one other casualty on the MONTPELIER while I was there. One of the enlisted men had some wire cutters and cut into a high-powered line in the turret. It was just a dumb thing to do.

There was another incident that I think is significant. It was when we got a message asking us to send a certain number of people back to new construction. They needed various ratings, like coxswain and so forth. The exec, Commander Koonce, said, “Well, let's see. Who do we want to get rid of?” I said, “You should send your best people back to new construction because you are manning a new ship and these are the guys who are going to train other people.” I don't know if I said that, but that is what I thought.

He said, “Let's see, there is this deadbeat.” I don't remember his name; he was in the brig because he had been caught stealing. He was a seaman first and was about to be knocked down to seaman third. He said, “We will promote him to coxswain and send him back to the States.” I said, “This is the Navy!?”

You can see a little disillusionment creeping in here. That is all I remember about the MONTPELIER.

When I was in Norfolk, I took the physical for flight training. Having become engaged, I was looking, as a lot of others were, for the best way to get back to the States.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the MONTPELIER never took a hit, did it?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not while you were on board.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

No, not while I was on board. There were some bullet hits, probably from attacking planes. I wasn't there that long.

I got my orders back to flight training. I went back to Washington, on leave, and got married July 27, 1943, in a white uniform--not wearing a shirt. I got married and I wasn't wearing a shirt because the white uniform is like that. My best man was “Bud”

Woodson out of the Class of 1942 with whom I played soccer, and the ushers were some other friends out of the Class of 1942. They were the only guys around that I knew.

Our honeymoon consisted of driving to Dallas for primary flight training. We were very lucky and managed to get an apartment, because it was hard to get anything to rent those days. When we first got there, I ran into Jim [James P.] Marion, who I had been a buddy with in the destroyer squadron. He had just washed out of flight training and was drowning his sorrows. I thought to myself, he stood higher in the class than I did. He was a better athlete than I was. What chance do I have of getting through primary?

Later on, I figured that he probably resented having some ensign telling him what to do more than I did. I was willing to have an instructor, who in my class was a Marine, second lieutenant, telling me what to do. Maybe Jim didn't cotton to that, I don't know. Anyway, I struggled through flight training. I would get a down on my first check and then get two ups. Do you want to know how I landed a plane upside down?

Donald R. Lennon:

That sounds interesting.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Well, we practiced shooting circles, which is to go downwind at 500 feet and come around in a coordinated turn and do a full stall into the circle. This was sort of preliminary to carrier landings. It was just one of the things that you practiced. We were flying Steermen (yellow perils) two-wing, open cockpit, wooden prop, single-engine planes. With this maneuver, you get into a stall altitude, then skid a little, and then level out and give it a little power. I had made a perfectly good approach, but when I gave it a little power, the engine conked out and I just hit on the wing and flopped over upside down in the circle.

I remember I had been told some story about someone who had been in a similar position who had undone his safety belt and fallen out and broken his neck. You are upside down and held by your safety belt. I turned off the ignition like I was supposed to do, I braced myself, and undid my seat belt, and got out of the plane. There was nobody else around, but there was an ambulance over on the side of the field because it was a remote practice field.

I put my parachute under my arm and trudged over to this ambulance. I went around to the back and looked in. There were a couple of corpsmen in there reading funny books. I said, “There is a wreck out there!” They said, “Where?! Where!?” I said, “Don't worry about it. I am the victim and what the hell are you guys doing, anyway?” I read them off. How I got away with that incident I don't know. I guess maybe they took me back to the base, I don't remember. We were supposed to go have a physical after something like that happened, but it was after hours and everybody had gone home and nobody said anything, so I just went home.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it do much damage to the plane?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Sure. It wrecked the propeller. I don't know what happened to the plane. I didn't have to account for it.

Donald R. Lennon:

That wasn't your problem, right?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I got through flight training.

Donald R. Lennon:

You got involved with some French Naval trainees while you were down in Jacksonville, didn't you?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

When I got my wings, which was 4-4-44, a memorable date, Maggie was about eight months pregnant. It was a tough time to have to move. So, I looked around and

found a four-month photo school. They took in twenty officers and two hundred enlisted men in each class. I put in for that and I got in. We stayed in Pensacola for another four months. That is where our first daughter was born. The hospital cost thirty-five cents a day.

Robert Taylor was in my flight class at Pensacola. That poor guy. He was having a terrible time with ground school because they kept taking him off for war bond rallies. He and a couple other guys, I think, are the ones who took Maggie to the hospital, because I was busy taking an exam at photo school.

Photo school was a great thing. For the first three months, you learned how to take different kinds of pictures, and aerials and things like that. During the fourth month, you flew the enlisted men up to take these pictures over the side with these hand-held cameras. You would go over some pulp mill in Pensacola and put the SNJs, they were called, up on the wing and the poor guy would be shaking, trying to take a picture.

After that school was over, I got orders to Jacksonville to instruct, because I had chosen PBYs in final squadron. We drove to Jacksonville, got a house, and I started instructing. One anecdote was that we had a bunch of French Naval cadets that were supposed to learn how to do water landings at night across the St. John's River. That was harrowing! I didn't speak French. I just remember that being harrowing because as we made our approach, I would be sitting there with my hand on the yoke, just in case they made a mistake.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think you would have needed to have been able to communicate with them.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I don't know how I communicated. I had to communicate in English, and I guess they knew some English. Anyway, I survived that.

One of the great things that happened during that period was that my father, who was then a captain, came to visit. I said, “How would you like to go for a flight?” So, I took him up in a PBY and had him sit on one side. After we got up and are flying along, I said, “Okay, Dad, you take it.” He said, “Ugh! I don't know how to fly!” You can see there was something psychologically wrong with me, wasn't there? It was great fun to take my father up in the plane.

I forgot to mention the time in Jacksonville when we had to get the planes out because there was a hurricane coming. We had to evacuate the planes, so we went to New Orleans. We left our families in Jacksonville. Maggie has never let me forget that. I showed her a picture of the nightclub in New Orleans we went to where Ina Ray Hutton was playing. We had a good time while the storm was going on.

Donald R. Lennon:

Really worrying about your family.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

We got orders to Whidbey Island in Washington, operational. This was the first time we actually went to amphibious planes, PBY-5As. They had wheels; before that it was all water work. It was good flying, but from the Navy point of view, there were a couple of interesting things. One was that I got orders to a squadron that was based in Alaska. I was not too keen about going to Alaska. Somehow, I knew that a classmate of mine was the exec of the squadron in Alaska. He was one of the few people that stood lower in the class than I did, which meant if I went there, I would take over as exec, because that is the way it worked. I communicated this somehow. I said that it didn't make sense for me to go up there and take his job away from him. So, instead of those

orders, I got orders to a squadron in the South Pacific, in Okinawa. This was fine with me.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was right at the end of the war?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

The war ended while we were at Whidbey Island. One anecdote there was that they passed the word that all those officers who were interested in going USN, because most of them were Reserves, were to come to hanger so and so. Those who wanted to apply to get out had to get in a different line. There were two lines and the line applying for USN was much longer than one applying for getting out because the guys never had it so good. They were flying, they had flight pay, and lived in the BOQ. I knew a lot of them, and I could see the good ones going to the getting-out line and the marginal ones going to the stay-in line.

It was at that point that the bomb was dropped, so the war was over before I went to Okinawa. I took over as exec of VPB 53. That was when I learned how well off the SeeBees were because they were next door. They had running water, hot showers, and all that kind of stuff, and we were still in tents with cold water and our helmet to shave in. The guy that was exec of that squadron was a Reserve who was anxious to become USN, so it was pretty important for him to be exec. When I came, I took over as exec because my numbers were senior to his. All he told me when I relieved him was, “Here are the keys to the jeep.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of a short briefing.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

The captain of the squadron sent him up to Yokosuka, where we had a detachment of three planes and put him in charge of that detachment. We did plane

guard duty on all the islands. Shortly after that, we moved our base to Saipan at Kobler Field.

I think the skipper was detached and I was made CO, which is what you live for in the Navy. I was mostly in charge of demobilizing. I had my crew's names up on a board, where things could be moved and changed around because I had to maintain working crews in all these places. At the same time, I had to get guys out, depending on when their points were due.

One anecdote to that was that one of our planes from Japan was flying to Iwo and lost an engine on the way. You could maintain altitude if this happened, but you had to decrease the weight; so they were jettisoning things--machine guns, people's suitcases, and souvenirs. Everything went overboard that wasn't needed. They made it back to Iwo, and when they checked the plane, the only thing that hadn't been thrown over was a little suitcase of seashells that one of the ensigns had collected.

Do I have to tell you about Chichijima? I heard that the Marine garrison at Chichijima, which is a little island near Iwo, was anxious to have an American plane come in there because no one had come in. They wanted to prove that you could get in there. It was a Marine detachment interrogating Japanese prisoners. There was a seaplane ramp there, so I thought, “Why don't we go down there?” I went down and landed in the bay, put my wheels down, and started taxiing up the ramp. There were several Marines playing basketball up on the ramp. I heard this crunch. A bomb had hit the cement underwater and there was a piece sticking up that hit my bow door. We backed off, went around it, and got up on the ramp.

Donald R. Lennon:

One that had not exploded?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I don't know. Maybe it had exploded. The ramp was defective and it tore a hole in the bow doors. This was an anxious time for me because how was I going to get out of there? I wasn't really supposed to be there and I hadn't made any arrangements to go there. I just went. The head of the Marine garrison saw us as heroes because we came to land in his place. They had this great dinner for us, presented us with Samurai swords, and gave the men Japanese rifles. The whole time this is going on, I am saying, “How in the hell am I ever going to get out of this?” He said, “Don't worry about it. We will fix it up.” The Marines riveted a patch where the metal had buckled. We went out and crossed our fingers, because if those bow doors don't close properly, you can get sucked under and there would be an awful mess. We managed to get airborne, and get over to Iwo Jima. Somehow, I got away with that one, too.

I finally got orders back to the States. My orders were to Banana River to learn to fly PBMs. I had already resigned at this time. When I got to Washington, where my in-laws were, I called the Navy Department. I said, “This doesn't make sense for me to go learn to fly another plane, because my resignation is in process.” They said, “Well, you are out of your mind for resigning anyway because you'll just be bored to death sitting behind a desk somewhere.” I said, “Well, that is what I want to do.” I was twenty-five or twenty-six when I resigned. I just thought I should do something different.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you are going to make a move, you need to make it then.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

It was the time to make a move. I wasn't too fond of the peacetime Navy. During wartime, it was great. I talked to Navy Personnel, and said, “If you have anything for me to do at the Navy Department, let me know. I'll be here a week or so.” I got a telephone

call, and they asked me to relieve a full Navy captain at the Coal Mines Administration as the Navy Department liaison officer. I said fine.

Here, I had temporary duty with per diem, flight pay, an office, and a WAVE secretary in the Interior Department. All I had to do was arrange flights for the people on the board. Harvey Collison was Deputy Coal Mine Administrator and Admiral Ben Morrell was in charge. I sat in on board meetings with them and arranged flights for them. I also went to a couple of coal mines.

Donald R. Lennon:

With the war over, the military was still controlling the coal mine operations.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Apparently.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's interesting.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I told them I didn't need a WAVE secretary, so she was reassigned. My other duty was to read the newspaper and cut out any references to the coal mines. This was wonderful duty, because in the meantime, I was interviewing for a civilian job. I talked to Scovill Manufacturing Company up in Waterbury, where a classmate of my father's was the vice president. I talked to Worthington Pump, where my father also knew somebody. I decided to go to Scovill because I could go into the executive training program and learn what it meant to be in business and how to make brass. I got a book on non-ferrous metallurgy and I was studying that while I had this great job in the Interior Department. When my resignation came through, I went up to Waterbury and started my civilian career.

Donald R. Lennon:

The training you received in the Academy, in engineering and other areas, I would imagine served all of you well in civilian pursuits.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

No doubt about it. I was at Scovill for almost five years. During that time I got involved with IBM and learned to put in an IBM system. That is another long story that led me to believe that I shouldn't spend my life at Scovill. I answered an ad in the paper, in the Washington POST, when I was on a poorman's July holiday vacation in Washington, DC. It was a blind ad from McKinsey and Company, a management consulting firm.

They referred me to New York because of my manufacturing experience. I went through many interviews and even had to report to the Psychological Corporation to a Dr. Fear, believe it or not. I got through all that, and was hired at McKinsey's as an associate. At the Academy, we were in a problem-solving environment, which over the years, working for at least forty different companies, helped me successfully handle many different kinds of things.

Donald R. Lennon:

I am envious of you. You spent two years working in London.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

Yes. When I joined McKinsey, I said, “I would really like to go to the Los Angeles or San Francisco office.” In the New York office, the manager said, “Well, you know, it would really be better for you to start in New York, which is the financial hub of the world, and you can just feel the dynamics of it. Then later on, you can transfer.” I think it was fifteen years later that I transferred to London. We were getting more heavily involved with international work, and London needed some experienced people. Actually, I think that it was more like eight because I was elected a director when I was in London. That title is like a senior partner. I worked with British clients there for two years. They wanted me to stay, but many who stayed for more than two years stayed there for life, and I wanted to get back to the States. I retired when I was sixty.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, this has been very interesting. See, you had a lot more to say than you thought you did.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

But, much of that I had never said to anybody.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you think of any other anecdotes that you have not said to anyone?

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

From the Navy?

Donald R. Lennon:

From the Navy.

Tully Shelly, Jr.:

I wasn't in the Navy that long, just five years. Not from the Navy side. For nineteen years as a McKinsey consultant, I worked with maybe forty different corporations, including Philip Morris. At Philip Morris, Joe Cullman was president and he had been on the MONTPELIER with me, so that was an interesting reunion.

At McKinsey, we had introductory training programs, where the new associates would go through three weeks of all kinds of training. They became like classmates. They would be an international group. We had associates with their contacts all over the world. Also, we staffed our assignments from all different offices.

I did a study in Tokyo for a Japanese oil company. I had a Japanese associate on the team, who had been educated in the U.S. We were to assess the economics of building a refinery in New Brunswick, Canada, and then do a joint marketing with a New England company. I had the Japanese associate go study with the New England outfit, while the American associates were studying with the Japanese. We did many things like that that caused us to be all of a similar ilk. It was not unlike the Navy fraternity which has remained even to this day.

[End of Interview]