| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #162 | |

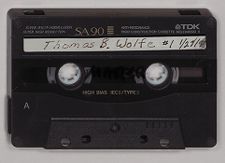

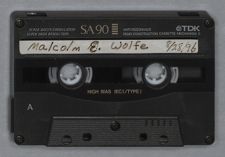

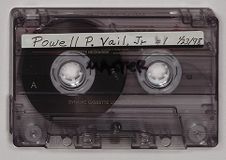

| Commander Thomas B. Wolfe | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| January 23, 1998 | |

| Interview conducted by Don Lennon and Dr. Fred Ragan |

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's go back to your early childhood. You were born in Virginia, I believe, in 1919.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

I was born in Roanoke, Virginia, on July 5, 1919. My family then moved by train, to Big Timber, Montana, in December 1919, before I was six months old. I lived there until 1922. We then moved from Big Timber to Mammoth Hunts Springs in Yellowstone Park in the middle of 1922, and we lived there for three years. We left there in 1925 and moved to White Sulphur Springs, Montana.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now why was your family moving around so much?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

My father was a doctor. He was just a general practitioner and was what they called a park physician. He took care of the medical requirements for the park during that three-year period. I lived in White Sulphur Springs for eight years and got through the eighth grade there. We left there in 1933. My only brother, who was in the class of 1935, is seven years older, and he's living in Columbia, South Carolina, right now. At any rate, Buddy's

departure for the Naval Academy in 1931 created my initial interest in the Naval Academy. I also have a sister who is five years older than I am.

In 1933, my mother decided she wanted to get out of Montana and ended up in a separation from my father who stayed there. My mother took my sister and I to Washington, D.C., and we entered Western High School. I graduated in February of 1937 from Western High School, went to a prep school for a couple of months, and took the exams for the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Which prep school was that?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

That's a good question. I would have to say Columbia for the lack of a proper name, but I don't know what it was. The word Columbia comes to mind, and I'll just guess that's what it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

The reason I asked that, I know there was a prep school there around Washington that a lot of the class members went to before they went to the Academy.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

This was not a large one--it was a very small one--and it was a prep specifically for the Naval Academy. I was prepped in English and math only; because my high school credits went down to the Naval Academy, and they accepted them. So I didn't have to take the five-subject exam; all I had to do was take the English and math. At any rate, I was appointed by Cliff Woodrum, the congressman from Roanoke, Virginia. I don't know what that district number was. He was a family friend and a great supporter of mine, and he gave me a start by that appointment. So I spent four years at the Naval Academy; well actually, three years and eight months, I guess. We graduated early in February of 1941 since somebody knew there was a war coming and wanted to get some of us out.

Donald R. Lennon:

What do you remember about the Academy, the people there, and the curriculum?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

I had a running battle with academics, as most people did, but I had one heck of a good time. I enjoyed my life there. We had good social activities as far as our social life, yet we had pretty tough academics to keep us busy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the harassment in your plebe year from the upperclassmen?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

I had a pretty standard plebe year. I had a couple of run-ins with a couple of people that I didn't think were harassing me--let's say in a legal sense. Basically, I didn't find anything wrong or incorrect about the plebe year that I had. It wasn't easy; it was a tough routine to put up with, particularly in the case of a couple of individuals. If you got an individual who didn't like you, it could make life quite miserable for you, particularly in the dining room. You'd spend most of your time under the table instead of eating. You could leave there quite hungry, if he didn't let you out. I didn't find it incorrect or improper in its conduct and probably agreed with the purpose of it. It probably made a better sailor out of me because of the result; I didn't have any problems with it.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lot of your class members have rather strong recollections of Uncle Beanie.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Oh yes, Uncle Beanie was a great captain. I can remember quite well. I was in a four-man room on the third deck, and it was youngster year. I went next door to check on something with one of my buddies, and who should come in but Uncle Beanie. We all snapped to and sounded off, and he said, "Oh, how are you and everything? "

Then he closed the door, and I said, "Whew, I got away with it that time." And the door opened up again and he said, "Oh by the way, Mr. Wolfe, did you remember to check out with the mate of the deck?" and of course I hadn't. He had an uncanny knack of writing reports on people, and it was in such a delightful friendly manner that nobody ever objected. He was really a remarkable man. I think he's an honorary member of our class.

Donald R. Lennon:

So he is still living then?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

No, I don't think he is.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't think he was.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

No, but I think he made flag officer and made rear admiral. And I think also he credited our class for it. I don't know quite how he gave us credit, but I think his reputation in our class was kind of a known factor among a lot of the higher-ups.

Donald R. Lennon:

I believe one of the class members in fact served under him at a later duty station.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Well, he was a great guy. And the great, stone-face Admiral Wright; he never cracked a smile during his entire tour of duty there, as I recall. We had an interesting gang of naval officers that were working there, and I think they were all pretty carefully selected. They all had navy blue and gold right down their backs, which I think is a proper thing to expose midshipmen to.

I did not excel in any athletics, incidentally, while I was at the Naval Academy. I did not get on a varsity team at any time. I was always working on the lower levels of battalion competitions. We had a going competition among the four battalions, and I was always on the third battalion track team and wrestling team. I had a lot of fun in athletics but never gained any varsity status. You know right offhand, I can't think of any other major events that occurred.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do much sailing in the Chesapeake while you were there?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

A little bit, but I didn't get too involved with sailing in the sense that I was one of the rabid sailors that we had. We had some people I think that still try to live on a sailboat, because they think that's the way of life. I go more for powerboats and that sort of thing. Sailing is just great, but you need a little wind.

Well let's see, I left there on February 7, and reported to my first ship the USS HERBERT. She was a destroyer and her side number was 160; she was in Key West, Florida. I reported on board about the first of March of 1941. There was a division of five destroyers, which were rotating two and three weeks at one stop. We rotated through the island chain there. We'd go to Key West, and then we'd go over to San Juan and have our gunnery phase over there. We would go on down and be off of Martinique for night patrol; at that point we were spending the days in a little island just to the south of Martinique. The French had, as I recall, one carrier, a couple of cruisers, and a half dozen destroyers in there. We weren't too sure what their intentions were.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now were these the Vichy French?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, Vichy French, they were French. At that point in time, you didn't know which side of French life they were going to be on. They checked the positions daily by aircraft, and at nighttime we would patrol off the entrance. We had a destroyer off the entrance there just to be sure nobody slipped out during the night. We were on good terms with the French patrol boat. They would pass us back and forth and we would wave our hellos in the middle of the night.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you were still a little suspect.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

They were still suspect. They had their patrol boat off the entrance at night, and so did we. Yet, we were on good terms with them. There was a concern over what those ships were going to do, and where they were going to end up.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't expecting any German submarines in the islands though?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

No, not at that time. That was the summer of 1941. In September we stopped that rotation, and the HERBERT proceeded up to Norfolk. We went into the yard, and they

pulled our four-inch guns off and put three-inch fifties on there, which were supposed to be a surface and anti-aircraft gun. The yard period got us in pretty good shape. A few radiators we had taken out of the ship were reinstalled and they sent us up north. We went up into the North Atlantic. In fact, we were on our way to Boston to join an escort group when on December seventh the Japs moved in on Hawaii in Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just out of curiosity, you said you were moving some radiators, what were the radiators used for?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

They warmed the spaces down below.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you said you removed them before?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

We had removed quite a few. We were down in the tropics, and it was so hot. These radiators were hard to clean and had been in the way.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they had been removed previously.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

For some reason or another, a radiator would just disappear out of the crew's compartment. Nobody would ever notice it until we were heading north. That was when we realized, "Holy smoke, we're going to need this in the North Atlantic." It was just part of the yard thing that there were a lot of questions asked about where were the radiators at that time, and of course nobody knew.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they refitted the ship with radiators?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, we got some radiators put in. We had left New York heading for Boston actually, when December seventh landed on that Sunday. We were given orders at that point to proceed immediately at maximum speed to New York--the idea being that the Germans might be running one-way missions into the New York area. They had the capability with their bombers to make a one-way trip, and that's what they were worried

about. So we fired up a couple extra boilers and were doing our maximum speed, as they say it in New York. We were doing this for about an hour when we got another message: Cancel that, turn around, and go on back into Boston. Somebody had a reconsideration of the possibility plus the consideration that the good ship HERBERT had newly installed three-inch guns that had never been fired, and we wouldn't serve as a very great deterrent.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, I was wondering how good that anti-aircraft capability would work.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

You look back on it now, and you kind of laugh at it. That was our capability, and we were going to protect New York with the good ship HERBERT.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I imagine there was pandemonium in the command and in the upper levels of command.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

That shook up a lot of people. I'm sure the number of orders that went out and were canceled were quite a few at that point in life. But we turned on around and went into Boston, at normal speed. We joined our escort group there and started our convoy duty. Our escort group with five ships and one new destroyer went up to Argentia on the western coast of Newfoundland. That was our base, and that's where we topped off our fuel. Then we pulled out of there, came down off Halifax, and picked up the convoy from the Canadians. Then we dropped the convoy off the English coast, went into Iceland to refuel, and waited for our returning convoy. I went for two round trips.

Donald R. Lennon:

And this was in the dead of winter, too, wasn't it?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

This is starting in mid-December, and that's just the time the Germans joined the program. The German operation off our East Coast sent four submarines over here to start on the first of January. They were such good pickings those submarine skippers couldn't wait, so they started dropping ships off our East Coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

Along the North Carolina coast they were really . . . .

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Oh, they did terrible damage, and it was all nicely suppressed in the news. We lost more ships and more men in our civilian side of life there, in commercial shipping off our coast. The losses far exceeded anything that had occurred at Pearl Harbor. It was a serious situation. It took us to the fall of 1942 before we really started convoying on our coast, and started having some kind of air protection and all the things that should have occurred a lot earlier; but we did lose an awful lot.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know the North Carolina coast was known as torpedo alley.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Operation Drumbeat is the name of the book. It's a very good book. If you read that book, you get a great insight on what was going on our East Coast. We had a couple of things happen.

I was in the HERBERT, what we called a short-legged boat, and we had around 85,000 gallons of bunker fuel, as I recall, for the boilers. During my second round trip up there, on the way back, we hit a really bad storm. The convoy got dispersed as a result of this, and the last night, when we were supposedly with the convoy, we were hanging in there on the leeward side of a great big tanker. We were just trying to conserve fuel as best as we could. The next morning we started picking up a little visibility as the seas eased off a touch, and we said, "So long," to the tanker. There wasn't another ship in sight; we had five destroyers and about thirty-five ships up to that storm. Anyway, we made it into the southern tip of Newfoundland. There was a little bay at the southern tip, and we came in there on the last breath of steam, so to speak, and dropped the hook. We had enough fuel to give us about twelve hours of auxiliary steaming, where the only thing we'd keep running

were the lights and heat--no turbines turning on. The next morning, we let all kinds of anchor chain out, because we weren't able to move and didn't want to drag anchor.

I recall that this destroyer came in and tried to anchor--fall back and beat alongside of us, but he was dragging anchor. It was a little too windy for him to get into position for them to give us standard fuel hose. We carried quite a few sections of fuel hose between the two of us; we could have transferred regular bunker fuel if we had had it. It ended up that he pulled up ahead, anchored well ahead of us, and dropped back on his anchor chain to the point where he could connect up with our hose lines.

The new destroyers carried about ten thousand gallons of diesel oil; so this was great. We got the fire hoses hooked up, and he transferred to us several thousand gallons of diesel, which worked just fine. I remember my chief water tender, the man concerned with these things, really was very pleased because the diesel was going to clean out all of his sludged up lines here and there. Running that nice light diesel oil through there made him really happy. So, we got our fuel on board and then went on up about sixty to eighty miles, not too far up the West Coast, to where Argentia is.

When we left Norfolk in December of 1941, we only had the exec as watch stander on that bucket. I forget the exec's name, but he stood all the four to eight watches and supposedly navigated during that period of time. Jake Bryan, the gunnery officer, got the next best choice; he got all the eight to twelves. Guess what that left me? I had all twelve to fours. So I stood all the twelve to four watches on the HERBERT starting in December 1941 until mid-March, when I left her in 1942. I was "Twelve to Four McGee."

There were two factors to this thing. First, the skipper we had--his name was W. P. Moet--was a true s.o.b. from way back. He was one of the meanest, orneriest people in this

world that I ever saw. He would sleep on the bridge in his chair. He'd be asleep on the bridge in his chair, all bundled up with various clothes and blankets, and I had the bridge job basically to myself. I look back on those days and wonder how we did it. We didn't have radar then that was worth a damn. If it did run, it didn't give you much of a picture. There was a single line where you got the direction. If the line had a lump on it--a blip of the distance to whatever it is--you had to train the antenna left and right, seeking the highest spot to supposedly get a bearing on this thing. So, what we had was an absolutely useless and no good at all to the officer-of-the-deck.

We wore strictly field glasses. The problem with the field glasses at night was that you kept getting sprayed, and you had to be able to keep your glasses quite dry in order to see through them. We were getting enough spray every now and then, so that it was darn hard to have any visibility at night. Our position was the starboard quarter on the convoy. We'd weave out, then come back in, then weave out, and then we'd come back in. Well, coming back in at night without any visibility, you can't see anything until you are right up close to it. So sometimes you'd come wandering back in there very slowly, converging on the convoy, trying to find one of the ships in the convoy. Looking back on the port quarter there, you would see this bow of a ship coming at you.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was a really dark night.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, it was a really dark night. It was great of fun. I look back on those days and wonder how in the hell did we keep doing that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any problem with icebergs?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

We didn't have any iceberg problems, but we had ice problems. If the wind was right in a stormy condition where you're getting a lot of chop, bouncing around and

splashing, you'd get an icing condition; you'd get ice all over your ship. We had all of our hands chip ice every once and a while. We'd time the roll of the ship, and when the roll would get to a certain point, we would start chipping; because it was starting to get top heavy enough to be serious. It was kind of inconvenient sometimes in the middle of the night to be up trying to chip ice off that ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

It almost seems like that would be futile. What did you use for chipping?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Mostly paint scrapers. A paint scraper was a piece of iron, about an inch-and-a-half wide and came down to a ninety degree at the end. It had about three inches on one end, ninety degrees to the basic handle, and both ends were sharpened. They were used to scrape paint off. They worked great for chipping ice off flat surfaces. Any kind of round surface or any line is awfully hard to chip, but you can crack it like a hammer.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about on the deck itself; it seems like that would be really treacherous to walk on.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

You're on your hands and knees when you're dealing with that. It's just an inconvenient thing to have to go through, let's say. I'm trying to think of something about convoy duty. Let's see, I made some notes . . . .]

The first trip back we were heading from Argentia back into Boston, and the men had already gone out and relieved the deck at the noon hour. Jake Bryan came on down. It was pretty heavy at sea, and we were heading right into it. We were making about ten knots, as I recall, which was just about what you could do. So Jake went down, and the captain was there, and they were talking about whether we could increase speed a little bit. Jake told the captain that we might well go on up to fifteen knots, because he thought it was easing off. So they hit the button--we had voice tubes in those days--and the captain told me

to increase speed to fifteen knots. I said, "Aye aye, sir." I took the enunciators and rang up fifteen knots. As we started to feel the speed increasing, the bow went up and up and up and up, and it came down. We were in perfect synchronization with the ocean at this point. The bow went way up, and then it went way down. We took a nice big wave right up on the bow when she started going down. I was dropping the speed, but that load of water came up on the deck. It lowered all the flat surface of this four-stacker effort built in 1919. It dropped the whole deck up there between four and five inches. What happened was that all the standpipes, which came up for fuel or for measuring tanks, and our deck supports, which were just steel pipes, stayed where they were, so we had holes all around them and our deck just dropped. It brought a good deal of water into the wardroom and into the chiefs' quarters. The chiefs' quarters were just ahead of the wardroom area, and all the chiefs decided to abandon ship. All the officers were in there eating lunch and here came all of the chiefs. Within about thirty seconds, I had half-a-dozen people up there on the bridge with me. That's one way to get a lot of help show up really fast. We just slowed down a little, and we didn't make enough speed from there on.

We were very careful about taking water on the bow from there on, because there was no way we could patch up that bunch of holes. And the funny thing was how pleased some of us were because this would mean that when we went into Chelsea Yard in Boston, we were going to get probably several weeks to repair our ship. Well, sure enough, that was our deal when we went into Chelsea Yard. Those people there were wonderful. They had lots of people on board already working on various jobs. We didn't even get the boiler fires cut down on them until they were on board working on various pumps and what not. Of course we took steam from the yard while we were there, so we didn't have to have a boiler

on often. Those people were wonderful. They worked twenty-four hours a day, and we'd come in there and get three and sometimes four nights alongside the dock, and they would do everything.

This bow situation didn't extend our time at all. They went in there and jacked up all those sections that had dropped. They jacked them up, and they had welders up there. They welded that thing and put patches all over the place, and they made it like new. They fixed that crazy bow situation. In three days it was all set to go along with everything else. We didn't get one lousy day as an extension in New York. Boston was the only place where we could really get clothing, warm clothing. The Navy issue in those days of foul weather clothing wasn't worth the powder to blow it. It was no good. We tried to stand watch in an open bridge and keep our glasses dry. It was absolutely miserable, because it was just plain cold. We had this wind and spray and we would get wet every time. I had two sets of clothing--I'd go down to the No. 1 fire room after watch and change clothes. I was always wet; we always left the bridge wet for some reason.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wet and cold, huh?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Wet and cold. We used to do a lot of shopping in Boston to try and get warm clothing. Hunters had various kinds of jackets and slipover clothing.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking in terms of the old whalers in New Bedford, Gloucester, and places like that; their foul weather gear. This hunting equipment--clothing--obviously wasn't a naval issue. There was no problem with being out of uniform?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Oh no, not as long as we could get warm. We were just trying to have some way of keeping warm. There was never any problem about being out of uniform. We wouldn't be able to wear something like that around the navy yard or anything, but when we were on

watch in the middle of the night in the North Atlantic, they didn't care what we were wearing as long as we were warm, wide awake, and doing our job. That was mostly the story.

I'll think about something else about the good old HERBERT. Well a couple of other things: I never did see a submarine or a periscope in those two trips up there.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't lose any ships?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

We didn't lose a single ship while we were in our convoy situation. After we got dispersed that time, I think a couple of ships were lost that were actually torpedoed when they were proceeding independently after that storm. The closest call we had was running out of fuel. Incidentally, I should tell you that the short-legged boats were a problem. The old four-stackers were a problem, because they really didn't have enough fuel to do the job they were trying to do. After our incident of just barely getting into Newfoundland, they took No. 1 boiler out of all those short-legged four stackers. The long-legged four-stackers had another 35-40,000 gallons. They had around 120,000 gallons, in the long-legged boats.

Donald R. Lennon:

How much longer were they than the short-legged?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

They were a little bit longer, and I'm not too sure which fuel tanks they had. We had fuel forward and aft, but I'm not sure where their actual fuel was. But the short-legged boats had fuel. We had two fire rooms, No. 1 and 2, with four stacks and with two boilers in each fire room. We had four boilers, so we would take No. 1 boiler out, and they'd pull the stack off too, by the way. They would then put a fuel tank in there where that No. 1 boiler was, and this gave them 98 percent of their speed and enough fuel that they could do some patrolling. The four-stacker was a remarkable piece of equipment and they were still going after all those years in mothballs.

Well anyhow, we were heading south and we had not had our full speed. We had a speed requirement to make full speed, which was a little over thirty knots--about thirty-one knots. It was based on the number of turns that your engines put out. We had to make this number of turns, which gave us the speed of about thirty-one knots, and we had to do it for a four-hour period. Well, the captain decided that this was a great time to do our turns. We were proceeding independently going back, so it was a great time. We fired up all the boilers. Incidentally, I was chief engineer on the good old HERBERT, had been in engineer for all the time I was on her. So, we were making our speed and good gosh, we had a torpedo sighted on the portside. It passed astern of us. Well, they were working on the sound gear, but the sound gear is no use to you at that speed anyhow--not above twenty knots because of water noises. They really couldn't get any results. Actually, fifteen knots was bad, but twenty knots was impossible.

Donald R. Lennon:

If you had been going slower, wouldn't you have been hit?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

The submarine missed the estimate of our speed somehow, and so the torpedo went astern of us. We went into a left hand turn and probably went over him making thirty knots, and he was probably more worried than he should have been. I think we dropped about three depth charges in this turn. We just made a 360 degree turn, dropped about three depth charges on where he might have been, came back on our course, and proceeded right back home. Our sound gear at this point was all torn down.

Donald R. Lennon:

So there was no point in wasting time looking for the submarine?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

They were working on it, but we couldn't stay around and do any good on them. The boss elected to head right on home. So, we kept going. The problem I had was that by making a left turn, the starboard engine rpm was way above what the port engine was able

to do. By making a turn, our outer propeller was able to keep up and provide excess turns, but the portside was not, because it was on the inside of the turn. I spent the next two hours struggling to get the turns out of the port engine so that we would pass our four-hour time trial. This brings up a point. I think it was the battleship WASHINGTON that came out for her speed trials--and I can't remember just where this fits in here--but she came out of Philadelphia for the speed trial. We had two destroyers; I think it was the NOA the on portside, and we were on the starboard side. We had four boilers lit off; I had one and two on stand-by, and three and four were operating. We could do about twenty-four to twenty-five knots on two boilers. The third boiler would bring us up to twenty-eight to twenty-nine knots, and the fourth would give us that thirty to thirty-one. The extra turns there at the top of the speed use a fantastic amount of power. The WASHINGTON at stayed about at fifteen knots for a daylight run, and we stayed with her. She was making about fifteen knots for several hours. We were up on the starboard bow, and then the NOA was up on the port bow. We were making twenty-two to twenty-four knots or something like that, and we were weaving and making a beautiful sight. It was too high of a speed for our sound gear to be of much use, but we were there.

The WASHINGTON said they were going to increase speed; that was all they said. Well, what they didn't tell us was how much. Pretty soon, I was doing all I could do with four boilers. We were staying ahead, but we were not weaving at all. We were just full-bore, doing all we could do. That crazy battleship then goes right on up to about thirty-one knots and holds it for a better part of an hour. All we could do was just barely stay on her bow ahead of her. Well, the poor, old NOA had three boilers on the line and about at the time they started dropping back; you could see them pulling the stack cover over No. 1

boiler. I can remember seeing them pull that stack cover out and firing up that boiler. Well, they dropped astern about five miles before they could start to pick up. So, they were way back astern, and the HERBERT was up there protecting the WASHINGTON for her speed trials. As she went back, they went back in the low 20s all the way back in. But those battleships could do over thirty knots when they opened up all the boilers.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you're going that speed, zigzagging doesn't really have any point anyway, because a submarine couldn't keep up. Could they get in position to torpedo you if you're doing thirty-one knots?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

If you're at that speed, why your chances were that the submarine would have to be in an ideal position ahead of you, to be able to set you up and be able to get a shot. As I understand when they were running those--like the major troop ships--they would actually proceed independently; because they could do more, and they could do higher speeds than any of the escorts. They were safer on their own. It's like the QUEMEE(?); she'll go cruising alone. I had a trip once on her here a few years ago, and that crazy ship just cruises along at twenty-nine knots all day and all night--no trouble. Let's see what else have I got to tell you?

Anyhow, we came into Boston after that second trip. This was in March of 1942; it could have been early March or April. I then got orders to the DAHLGREN. She was in Key West, Florida, and I got "proceed immediately" orders, which made the captain very unhappy. He screamed like mad, and they said, "Go." So I had to. "Proceed" gave you four days plus travel, so I balled down on the train to Miami. I then took the bus from Miami to Key West. The train did not go all the way down to the Keys. I don't think it does today, either. That railroad was washed out in the mid-thirties I think by a hurricane. Anyway, I

reported to the DAHLGREN. Bob Cavanaugh was the skipper, and he had an exec who was, as I recall, a full lieutenant that had been recalled from the reserves. He was what you'd call "an old man" in those days. An old man to me in those days was someone around fifty-five or sixty-five years old. This one had come back on active duty and he was really a great guy. He had glasses and all sorts of problems with his vision. He also had no idea in the world what to do with the deck of a ship or about being the officer-of-the-deck.

So Bob Cavanaugh had lost all of his qualified watch standers, and when I reported on board, he had no qualified watch officers as OD fully qualified for both day and night. He was able to get a little bit of sleep now and then during the day since he had seven or eight ensigns on board; all of them were ninety-day wonders. All of them were great guys, but they had no experience; so, the ship was an experimental engineering plant. The DAHLGREN had a 1,250-pound pressure experimental steam plant with the exact horsepower of the other four stackers that existed. The DAHLGREN's No. 1 fire room was standard with the old two boilers of the four-stacker. They put two high-pressure 450-lb pressure steam boilers in the number two-fire room, increased the length of the fire room a little bit, and put one stack on them. She was a three-stacker. They combined the No. 1 and 2 engine rooms into a single engine room, and she had this extremely high-pressure steam. At that point in time they were, I think, the more or less standardized on about 650 or 625 as far as the high-pressure plants they were building. But this was an experimental job that. Someplace in the mid-thirties, I think, is when she got this experimental plant. It was a very unique plant. You didn't want any steam leaks because a steam leak would burn. Take a broom handle and go over a leak with that thing and the broom handle just cut like a knife, it was just extremely hot. Anyhow, quite a plant! We could go up thirty knots and that rascal

would set thirty knots in cruise and it wasn't any problem; they could run that thing in full power without any difficulty whatsoever. So we could go from point to point quite fast.

What was going on was that the DAHLGREN was assigned to sound school in Key West, and that's where all the sound school training was going on. They had PC boats, a couple old eagle boats, the DAHLGREN, and some converted yachts. They had all kinds of stuff in there, and they must have had a half-a-dozen old submarines. Every morning, they would go out and down. Then they'd cruise around, and the school boats would come and work in different areas to train and practice with sound gear. They were training deck watch officers, prospective commanding officers to do this, and sound operators: It was the sound school for the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this tied to sonar? How did it operate?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes sonar; this was all sonar. But the thing was that at the same time, the Germans were dropping ships all along the coast there. So we spent most of our time going to places after the fact. A ship would sink off the entrance to New Orleans and they would send us over to search the area and find the "said" submarine. The sound equipment on those old destroyers just wasn't the best, and the depth charges we had were not quite right either. We had a three-hundred-foot limit on how we could set depth charges when the war started. We knew that the Germans were something below that; you didn't have to be a whole lot below three hundred feet to be perfectly safe if you were in the German Navy down there. These depth charges going off several hundred feet from you might shake you up a little bit, but it didn't damage you in any sense. So we were trying to figure out ways to delay the firing mechanism based upon the pressure of the water. We tried to put all sorts of wax and gunk into the firing mechanism to delay it, but none of these things worked. The depth changes

would get down to pressures of three hundred feet--which was pretty severe at that point--and they would go off. At any rate, we were spending our time primarily up and down the Florida coast.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you doing any rescues as part of that?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, we picked up survivors several times; however, once again, we had no luck trying to find the doggone submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Around the time you got there, they had probably moved on.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Oh they could have been right within visible distance from us several times, and we wouldn't have known about it. We had all sorts of night possibilities, you know, because of the surface at night. By this time incidentally, there was air surveillance going on along our coast during the daytime so they weren't able to stay on the surface during the daytime and comfortably go on about their business. We had at last received enough air coverage, so they didn't just stay on the surface, but we didn't have any luck.

We spent an awful a lot of time dropping depth charges. I remember one time off of Norfolk we dropped a lot of depth charges on a slow moving target. You have to keep in mind now that the navigation in those days was not all electronically precise; we did a lot of DR [dead-reckoning] work. If we were in the Gulf Stream, for instance, we could find a target and be getting a good response from it. And it would be a sunken ship that we were pinging on. As best as we could, we had figured out that it was a moving target and we would be dropping depth charges on this hulk under the water. We also depth-charged a couple of big airplane tires. These were off of a big bomber of some sort. They were a good five or six feet across. We also had two wheels with inflated aircraft tires on them popped to the surface after one of our runs. Our first thought was that they were escape

buoys from a submarine, but when we came by the next trip and looked at them with our glasses, we found out that those were just plain, old airplane tires.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you depth-charged an airplane that was already sunk.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, we depth-charged an airplane. At least we shook some of the cargo loose; they were very buoyant. I remember we pulled up alongside of the tires and pulled them on board. I remember all of us claiming: “There's my abandon ship right there!” on them. But you have to remember that today they can tell where they are within ten feet at all times just by looking at the dials. In those days we were just playing around with DR [dead-reckoning]. We'd come left to this course for a certain length of time at this speed and we'd decide we ought to have been there. We just dead-reckoned our course where we were, and sometimes we weren't all that close.

I had to have over two years in destroyers before I could go to flight training. I left the DAHLGREN in September--I was on there from March of 1942 until September of 1943--and went to flight training. I reported into Grand Prairie, Texas, which is right outside of Dallas. It's where the big airport is now--Dallas Fort Worth International or something like that. Well, it used to be right there, a little Naval Air Station that flew N2Ss--a biplane single engine training personnel.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you that interested in aircraft or were you just wanting to get off destroyers?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

I had been interested in aviation for some years and always had kind of a hope that I could get into aviation. At graduation that wasn't available to us at that point, so I spent two years in destroyers--in the Fleet really--before I could go. Of course, I ended up two years and eight months or something like that before I got to go. But all I had to do was ride

around on a “tin can” there in the North Atlantic for a while and watch the airplanes fly by, to say, “that's a better duty. That is better duty!”

Donald R. Lennon:

Unless they fall.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes, that's true. But in Grand Prairie, I learned how to fly the little N2Ss. From there I went to Pensacola and I got my wings in April of 1944. I went from there to Lake City, Florida, in April 1944 to the PV-1--that's the multi-engine patrol bomber for operational training in type. I took the course in Lake City, which is six or eight weeks of flying, and then we went up to Beaufort, SC, for the gunnery phases. Some nights I worked up there, because I ranked as a full lieutenant at this point. What they did with the senior people when they came through like that was to keep them as instructors to build up their experience in flight time. I was an instructor then for a year in PVs at Lake City. PV-1 was a good high performance aircraft; I always enjoyed flying them.

After about eight or nine months of instructing, I was approaching my final year. I was due out in August of 1945. I remember very well being here in Jacksonville at the air station and talking with several of the wheels about where I should go. At this point, I was a fairly senior lieutenant. A lot of people at that point and time could see the end of the war coming. The question raised was what part of the Navy should I be in for a professional future. It was agreed that seaplanes were the future of the Navy; we had a jet seaplane being developed by Martin and we were going to take over the strategic bombing responsibility from Curtis LeMay. There will always be a real future for the Navy in seaplanes, because we have so much water and can operate any place in the world. So if someone wanted to go into what the future is, he should go into seaplanes.

I got lined up with the right people and got my orders to seaplanes. I was being detached in August of 1945. The Japs heard I was coming, or else the atomic bomb did some good. The war ended: Kaboom! I was all set to be detached in about two days, and they said, "Wait, cancel everything, hold all orders." After about a week, we got the word to go ahead and carry out our orders. I was then detached there at the end of August after the war was over to go to seaplanes. The training was in Corpus Christi, Texas.

I had been waiting to get married until after the war, so I got married on the way to Corpus Christi. I checked in there, and I was the last crew to go through on their PV training program. The PV was a seaplane, a gull wing. It had a couple of 2,800 engines, 2,400 horsepower. It was the future of the Navy. So in December of 1945, I went to North Island an air station at San Diego. They had the final phases of the training for plane commander designation there. I had night flights, gunnery, and sundry last minute things—requirements--that they couldn't do it at Corpus Christi. It had to be a fleet outfit in the Pacific. I got plane commander in a PV in late February or March of 1946 with the Pacific orders to--ComAirPac in Honolulu--for further assignment to a PBM squadron.

One little thing that happened in San Diego was that my wife had a very dear friend of hers who had married an Army captain. One night, they came to see us, but I had a flight that night. I had to go out and rendezvous with a ship someplace and do some practices doing this and that. So I invited him to come along. He said, “Oh, sure, I'll come along.” About seven o'clock at night in the dark of the night we went out and got in the PBM. Everybody was all set and we took off. I was climbing out by Point Loma, when we had an electrical generator problem. The lights were gone, so we had to shift to the auxiliary power unit and we had to come on back in. I just continued on in a climbing turn and came right

on into the pattern, and landed. They took us back on the beach and gave us another airplane. We'd given my good friend, the captain in the Army, all these emergency procedures. Here's a life raft here above the waste(?) area. If you ever have to go always take a life raft with you. It's a whole lot better in the water if you have a raft instead of just floating around in a May West.

He had not seen what happened to the wheels and he couldn't figure out what happened to them when we got in the water. Well, they were locked on the two sides of the hull. When we tripped them, they were pulled out and away from the plane and pulled back on the beach by the swimmers they had out there in those days. We unlocked them ourselves from the seaplane and then they would just pull them back and away. When we came in, we made a buoy and they hooked on to our tail and set us in position to come up on the ramp. Then they pulled these wheels out and attached them to the hull--the two big side mounts and the mount in the rear. The tail wheel mount was the steering gear; that's the way we steered, with a long pole. So we had him watch on this launch. While we were at the head of the ramp, he stayed at the hatch on the portside, so he could watch that set of wheels to find out what happens.

Well, I taxied up to the head of the ramp. When we're like that, they hook a bowline on the plane to hold us in position from the bow when we come over the side. They have a big heavy tractor at the stern, and he has a heavy wire to the tail. As the plane goes over the lip of the ramp, the tractor is what keeps us from just coasting downhill. Normal procedure is that the tractor comes down slowly, and we taxi on out and get floating. Then they take the wheels off of the seaplane and disconnect the tractor. Next, we disconnect our bowline, and we're free to go. Well this night, what happened was when we got over the lip to go

down the ramp with these main two mounts--we were pretty heavy--we started down, the shackle affair at the tractor broke. That means we were going downhill very fast. We were feeling great, but the poor guy on the wheel--the guy that's steering--he fell down. When he fell down, the steel bar that he's steering with dropped down and turned, so were heading off to the right. We went heading off to the right and over the right edge of the ramp. As we went over the edge, we wiped the bottom right out of the stern of the plane. The left mount hit the water line--right at the water line. But when the right mount went off, we were just in a ramp and going odd into nothing. The plates were wiped right off the bottom of the hull of this plane. So we hit the water, and I said, "Is there any damage aft?"

He said, "Yes."

I said," Are you taking any water?"

He said," Yes, it's coming in the waste hatch."

I said, "Abandon ship."

My Army friend is watching this launch, and he can't figure it out. He's thinking, boy this is sure rough the way they're doing this this time. He's watching that left mount, and he hears, "Abandon ship!" Well, that rascal went aft. He gets into the waste area back there while everybody is abandoning ship. He reaches up, gets himself a life raft, and he goes out the door. He has to submerge a little bit to get out. He gets out of the plane, he pulls the lever, the little handle on the, and he climbs into his life raft.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right at the ramp!

Thomas B. Wolfe:

He's getting people on board his little ship. Everybody up forward is on the bridge. I started to come back and go through the airplane, but when I stepped down off the flight deck, which was elevated in the plane, the water was coming in at my feet. So, I go back

forward and go out the top, above the pilot's seat--we had escape hatches above--and I came up out of there and stepped right into a tender boat that they were using for launching and recovering. They always have this little boat there. I just stepped in there; I didn't even get my feet wet.

Donald R. Lennon:

And he's floating around in a life raft!

Thomas B. Wolfe:

(Laughter). So we accounted for everybody real fast and got back on the beach.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now how many of you were aboard?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Thirteen or fourteen. I had a full crew, plus my friend . . . . At any rate we went back, and I took him back to our apartment. They were staying with us. Of course I was perfectly dry, and he was wringing wet. It looked like he had been swimming. My wife and his wife welcomed us home. My wife knew that something was going on, because she could hear my radio when I was coming back in. She knew that I had had to come back in. She didn't think we had gone out either. She was monitoring our movements and she never heard us go out. However, I think the U.S. Army came through gloriously there; I was very proud of him. We, of course, made him an honorary member of the crew.

In March, I went to Honolulu. I was only there for a day and was assigned to the VPB-28 in the Philippines. We flew out there to the squadron, which at that point in time was moving from Palawan to Cavite. NAS Cavite was just a strip for landing planes, and we had a nice protected cove for our seaplane. We had about a nine-plane squadron PB4Y-2s and nine PBMs in there.

We then moved from Palawan up to Cavite. My wife came out there with the first group of dependents on July 1, 1946, and we spent a little over a year there. It made a good

operating area. We spent our time there doing some patrolling; but the war was all over, and there was no real patrol necessary. However, we just patrolled to fly.

We came back, and then we moved the squadron back to Kaneohe. NAS Kaneohe is on the eastern side of Oahu. It has a beautiful air station, and the Marines have it today. The Marines were sharp enough to pick that up, because it is a real gem. It's a beautiful spot over on the eastern part of Oahu. You have a steady eastern breeze coming in there. It has a beautiful climate, nice and cool.

I had not been there too long when I was shifted to the FASRON 117. This was in 1947. FASRON 117 was a service outfit for taking care of all Fleet squadrons. The reason I was shifted over there was because they needed someone over there for a temporary command.

Tape 2, Side AInterview completed by Dr. Fred RaganThomas B. Wolfe:

As I said, I was in Kanioke Bay, Hawaii, where at that time we had a couple of seaplane squadrons and a landing plane squadron. I ended up moving from the seaplane squadron to the FARSON 117, which as I mentioned was a service outfit for taking care of squadrons. Squadrons can't take care of themselves and we provided certain routine services to them and also took care of the heavy maintenance on the base. I was only there for about a year and left there in the latter part of 1948.

I flew back to the States, incidentally, on one of the Mars boats. At that point in time, we had about a half dozen Mars seaplanes that had established the NATS (Naval Air Transports System) route coming out of San Francisco and going all the way to the Philippines and back.

I don't have any special things about FASRON that I should tell you about.

However, (and I wish I could remember his first name) I did attend a very interesting meeting there one day though. Admiral Johnson reported in out there and took over the wing. I've forgotten what the command was, but he was the number one boss man for that area. He was a wing commander of some sort. He came in and had his first conference with all the different commands there at Kaneohe. At the front table all the commanding officers sat at the table, and he sat at the end of the table. All of the execs sat in chairs around the outside and backed up [their particular] boss if he had some questions; the execs were supposed to have the to answer.

The conference started off, and he said in a sense that he was glad to be there and hoped that he could do his part to carry on the good deeds of his predecessor. Then he said, "I'd like go around the table here and would like to know of any problems that any of you have, which I can take note of. Maybe I can help, and maybe I can't. But tell me about yourselves, about your squadron, and what your problems are." So we started around the table, and the various commands for some strange reason didn't really have any problems. However, they came up with such things like there was a bad parking situation at the Navy exchange, and there were too many cars not parking between the lines, and that we ought to do something about that. There was another report that FASRON hadn't completed the inventory on certain materials and was late getting it in. It continued on around. Then somebody had a complaint about the food, and this and that. Finally, it got all the way around, and he stood up and said, "Now, gentlemen, if we all put our shoulders to the wheel, we can make a problem out of this." Then he walked off. [Laughter.] It changed the whole tone of the weekly command conferences. People walked in, sat down, and there was no

more complaining. It was amazing how that little word or two set everybody straight. It was one of the most educational conferences that I have ever attended, because a lot of those conferences degenerate down to such trivia, that it's absolutely ridiculous.

Fred D. Ragan:

It sounds very much like an academic community.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Yes. He said, "We'll all put our shoulders behind this wheel and, we'll be able to make a problem out of it.” Kaneoke was a wonderful place for duty, by the way, in those days. We had good quarters on the station. Termite Village is where I lived. They had officer and enlisted temporary buildings, but they were built with wood and plaster, and they were called Termite Village. They had some large homes up on top of the hill that were made of stone and had permanent structures which were beautiful quarters for all the commands that were based there. It was a great place for duty, and the climate was terrific.

I left there and went with my family, my wife and new daughter, to Washington for OPNAV duty. OPNAV is incidentally the CNO staff. I was in O & I, and I did almost three years there. I think intelligence duty is always interesting, a little frustrating, but for the first two years I was in a joint air intelligence group with the Air Force, Army, and a British and a Canadian liaison. I didn't do any particular work with them, but they were working there with us. The last part was within what they call the Air Section of O & I itself. As I have said, intelligence is interesting duty, but I'm not too sure what great professional things I learned or anything. Being a gumshoe is not particularly in the right direction as far as sea-going Navy is concerned.

Fred D. Ragan:

Are there any particular stories that you would feel comfortable in relating about the projects that you might have worked on?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Oh, I was working in the intelligence on jet engines. At that point in time, the British had sold the NENE engine to the Soviets, and that was causing a lot of hubbub within some of the intelligence people. There was always that little suspicion of the British, but I never did find out why or for what. But it goes back into the start of World War II when Admiral King, of all people, would not accept British intelligence and British cooperation on the subject of submarines off the East Coast. As I read the story and have understood, he did not believe in being too cozy with the British. I can't put any reasons behind that with any facts or figures. However, I do know that sentiment existed, and it is just an observation that I can make at this point.

From OP 32, which was the intelligence at that point in O & I, I went to the CORALSEA in 1951 as the navigator. I had just made commander. She was in the Med [Mediterranean] at the time, and so I flew over to the Med and joined her in Naples. I relieved the navigator about a week later and had a great tour on the CORAL SEA. I was really enjoying my life, because it was a big new carrier--the biggest, the newest, and the best there was at that point in time.

I always said that I was responsible for making two new four-star admirals. James S. Russell was the commanding officer when I first reported on board. He was relieved in Norfolk by Bob Peary about eight or ten months later. Both of them made four stars, and that's because of navigators doing their job. If you want to know how you make four stars you have to have the right kind of navigator! (Laughter)

It was interesting to me how those two were very different in the way they handled and maneuvered the ship. Russell was very conservative, and in a sense, rather tentative about controlling the ship. Peary was just the other extreme. He handled it like it was a

destroyer. He didn't mind using power, and he'd go from two-thirds backing to flank speed ahead. He just went for it; he'd use power. We'd come up on a refueling tanker, and the tanker would be making twelve knots. Well, the basic approach to the stern tanker would be at about twenty-five and he'd slow to twenty as he was making his approach. We'd go from twenty knots ahead to back two thirds, which was rather an extreme movement in terms of maneuvering a carrier. He knew when to do that. As he was coming alongside he's back two-thirds, and when we slowed to the proper position, he'd say. “All ahead, twelve knots.” He would give it a turn and bring that ship in there and stop it right on the button. Lines would be going across within seconds, because he'd pull it in there and park it right on the tanker. Anyway, he was a terrific ship handler. It was really amazing what he would do.

The navigator does not fly as part of the air group. He does not fly on and off the aircraft carrier. So what I had to do was get my [flying] time in when we were in port. We carried a couple of SNJs, which are small training aircraft, single engine. The Js would be flown off and put at local airfields when we would come in, and then we would ride the helicopter over to the airfield and get our chance to do our flying to keep our flight time up. I have a great deal of respect for that carrier aviator. Those boys have to be good. On a dark and stormy night, when they launched them, then they would have to come back and land them, too, you know. It's a fantastic experience. The flight and deck crews are handling the hangar deck and the flight deck--they were beyond belief. I mean they just click, click, click. Everybody has a certain job to do, and they are wearing the right color shirt and they know what they have to do. It's fantastic precision work. I was the navigator for about eighteen months on there. We came back to Norfolk and had an overhaul during that period.

Fred D. Ragan:

. . . . Break in Interview

Thomas B. Wolfe:

I left the CORAL SEA in Greece and flew back. Then I flew down to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to take command of VU-10, which is a utility squadron that serviced the training ships that were operating out of Guantanamo Bay. We provided the air services for them; it was a big squadron, and it was a really good job. We were provided beautiful quarters, and I enjoyed the whole shebang for about a year and a half. I wish I'd had more duty like that in the Navy, because it was great.

I went from there to Washington, to what's called the joint war room annex. . . . . That was their war room for control and briefing on the subject of nuclear weapons. We had the full inventory: Army, Navy, Air Force. It was a very highly classified and busy little operation that we had going down there. We had the joint staff plans and the targeting schedules for worldwide use. We had all three services, and we had briefing rooms with had all sorts of charts and maps of the world to work off of in order to brief them, and for them to make up their minds on what they wanted to do. That is what it boiled down to; it was a command post! Thank goodness it never got to be used as any kind of an operating room. We also had our place up at Camp David--in the underground facility up there. We were supposed to be able to pick up there--could start here and move it up there. It was a complicated set of things to do. That's what we were doing in that job, and I was there for almost three years. I went from there to the CORAL SEA.

Fred D. Ragan:

Back to CORAL SEA.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

No. I went from there to Iceland in 1957. That was a year's duty up there on the joint staff. I was the Navy deputy chief of staff. For that job, I had a year without dependents. More or less, I think Iceland is about as far away as one would want to be. I

hate to use the term, but Iceland just happens to be the “asshole of the world.” A lovely spot to stay away from.

I then came back to OPNAV. I came back into 0(?)52, which was the detail office for aviators. I was detailing, writing orders for lieutenant commanders and below, with about five officers working for me in that business. I had that job for a little over a year, when the selection for captain came out. I was in the key job for detailers, a sure-fire captain selectee, but I was not on the list. Well, they couldn't have a passed-over captain in the detail business, because the detail business is where they determine where all the orders are going to be, so I couldn't stay there.

I had to move out, and they put me in the inspector general's office at BuPers. I stayed there for two years until retirement in 1962. I was a guaranteed selectee but didn't do it. To this day, I do not know exactly why. That was kind of a hard blow to take at the time, but then I looked around and realized there were better men than I that had been passed over and lesser men then I that had been selected. So I started feeling that maybe the selection business wasn't all that precise. Who knows?

That's the end of the story.

Then I went to work for a trade association called Printing Industries of America. I worked for them for nine years. Then, fortunately, I got a job with Bechtal Power Corporation in Gaithersburg.

Fred D. Ragan:

Construction?

Thomas B. Wolfe:

It was with an engineering construction firm, and I worked for them for fifteen years actually. I spent the first five years in administration, and then the next ten as an electrical engineer. I retired from there in 1988, and that's about it.

I don't know if it's germane, but my first wife died in 1991. I then married my high school sweetheart from Western in 1994. We moved directly down here to this retirement community at Fleet Landing.

Fred D. Ragan:

Well in the inspector general's office, it really was very exciting.

Thomas B. Wolfe:

Well I traveled around and inspected. We were in the Bureau of Personnel. We were inspecting personnel offices and that's kind of a “yucky” job. You get some interesting travel, but people don't like inspectors. Let's face it. They don't look forward to seeing you. Being in the inspecting general business was a drag although I had duty with some terrific people. I learned an awful lot about the Navy that I didn't know, because I traveled all around and inspected places like Spain, Italy, the West Coast, and all over the Navy facilities.

[End of Interview]