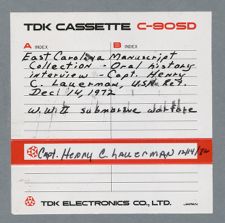

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #40 | |

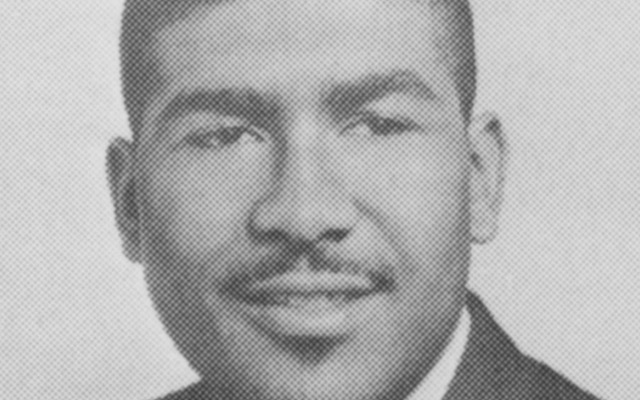

| Commander H. A. I. Sugg USN (Ret.) | |

| February 23, 1977 |

H.A.I. Sugg:

I'll start first with a very brief biographical sketch. If you want any filling-in, then I can do that. I was born in Lone Wolf, Oklahoma. I was born on my grandparents' farm in 1918 while my father was overseas. I understand that he didn't see me until I was about ten months old or something like that. After he came back from the war, he homesteaded out in Idaho. My earliest memories were of the trip out there and being there in that homestead area. I think we went out there when I was about eighteen months old and left when I was about three. Ultimately, I had a younger sister and three younger brothers.

My father had lost a lung in the war and had some severe problems with his chest, but I'm not quite sure what they were. He was in a veterans' hospital for a couple of years while I was young. He had been farming up until that point but afterwards was unable to do so. So, he went to the University of Idaho at Moscow. He took his masters degree in agriculture. That was where I started to school. I skipped the first grade there and took the second, third and fourth. In the meantime, he became principal of a school down in southern Idaho. I went a couple of years there. Then, he became the principal of

the high school at Jerome, Idaho. There I skipped another grade and went to the seventh and eighth grade and high school. I graduated in 1934.

I was always a good student. I learned to read before the age of three and this sort of thing. This was due to the fact that both of my parents were schoolteachers. My mother was teaching school while my father was in the hospital. So, I developed very rapidly academically. I always stood one in my class.

I got interested in the U.S. Military Academy through knowing some family there in Jerome who had some people who had gone there at one time. I applied for an appointment and got one. It turned out that I was six months too young and was not eligible for the Military Academy which had the minimum entering age of seventeen, so I went to college for a year.

I got a scholarship at Linfield College at McMinnville, Oregon. I went there for a year. They had a standard course program for freshman students. Someway or another, I was able to con them out of that. I was able to take the courses I wanted then without going to class. I worked at three different jobs then to pay my way through. I would go in periodically and take examinations. That was how I got through that.

I had only one grade other than an “A.” That was in the PE program where we had to do these silly exercises. I got a “C” on that.

I got to know my professors personally very well. I used to play bridge with my physics professor. I would go to the ball games with my philosophy professor and things like that. That has been one of the major things or events that has had a major influence on me. I was interested in academic things, but I was interested in so many other things

that I really didn't know what I wanted to do. I knew that I was interested in the Military Academy.

The next year I had hoped to go to the Military Academy, but there was no appointment open. The only appointment was one for the Naval Academy by a Congressman from Idaho. I think his name was Coffin. He gave competitive examinations for appointments to the academy. During Christmas vacation at Linfield College, I learned that there was an opening and that they were giving these competitive examinations and that I could take this at the Post Office in Portland, Oregon. This was nearby. So, I figured, “Well, I'll just take that so that I will be prepped up for the next year when there will be an opening at the Military Academy.”

I didn't really prepare for this examination, but I won the damn thing. The next thing I knew, I had a letter appointing me to the United States Naval Academy. Well, not really being sure what I was interested in, except that I was sure that I was interested in the military, I decided to go ahead and take that appointment. I must say that I have been glad ever since. This was especially true after we got into World War II. In the Navy, most of our foxholes had hot and cold running water and things like that.

At any rate, I enjoyed my naval career. I went to the Naval Academy, entering in June of 1935 with the Class of 1939, just after my seventeenth birthday. My eyes went bad and I was given a physical discharge from there at the end of my third year.

I subsequently went to work as an engineering assistant at the United States Naval Engineering Experiment Station at Annapolis. I was young and eager and bushy-tailed and fairly knowledgeable in engineering and math. So obviously, I could get a tremendous amount of experience there and get assignments which were unusual in that I

was put in charge of some major research programs involving Westinghouse and General Electric Corporation, Farrell Birmingham, and consultants like Dr. Den Hertog of MIT who is probably the outstanding authority in the world on machinery noise and vibration. I got to know a lot of these people.

I was also fortunate for coming along at a stage when some new technological innovations and electronic devices and recording equipment were out. We had a contract with a small firm up in Long Island to develop this. I worked with them on developing recording equipment which could analyze sound and the frequency spectrum and so forth. For the first time, we were actually able to record these things and analyze frequencies. That technical breakthrough really was a tremendous help because before that most of this area had been speculative. They knew things were happening, but they couldn't really tell what was the cause. I guess my biggest contribution was to demolish all the previous theories about why a machine was noisy. This was done simply on the basis of data that was gathered aboard ship and various places, and at some of the testing stations at Westinghouse.

About that time, I was interested in sailing. I had always been interested in sailing and a friend of mine had about a fifty-five foot schooner called Harpoon. He was a Russian and was quite a bit older than I. He wanted to go down and see the South Seas. His wife had died. So, I resigned my job at the Naval Engineering Station. This was effective about two or three months later. We figured that he and I could take this schooner and go on down and with a little bit of work here and there, we could go do this thing that both of us wanted to do. This was about the time that the Germans invaded France and the Low Countries in 1940.

As soon as that happened, I decided that the place for me was back in the Navy. Because of my history of eye trouble--even though my eyes had improved until they were completely normal--I couldn't get a certificate from the Bureau of Medicine saying that I was qualified for sea duty. So, I was assigned as an instructor in the Department of Marine Engineering at the Naval Academy. I also was to lecture at the Naval Postgraduate school, which was there at Annapolis, on various aspects of machinery noise and vibration. I taught there for a little over two years. I came back to duty in October of 1940 and was very much interested in going to sea but couldn't get over there because of this medical thing. So, I taught thermodynamics, naval architecture, theory of internal combustion engines and things like that.

I had a lot of extracurricular activities besides girls and the good things which I had were in full measure and they were readily available in that area. That was sort of the last gasp of the golden age of high society. I played bridge and wore a tail coat. I was assistant officer in charge of the boat club because I was the only person who could make the three cylinder Atlas Lanora diesel engines in a couple of dozen of our ketches run.

I ran into a friend who had a large collection of old movie films of the Old Navy. I knew the curator of the Naval Academy Museum there, Captain Baldridge, who had a son a couple years older and another son who was a classmate of mine and I knew the family. I had a big interest in developing the museum and so forth. I mentioned this to them and wound up being the assistant curator to the U.S. Naval Museum in charge of the photographic library. I established it there.

I was also the only junior officer on the admiral's visiting committee which escorted the VIP's around the Naval Academy, because somebody found out that I knew

a great deal about the history of the Naval Academy. I met a great many very delightful people that way including some very senior people. I was there until June of 1942.

Then Pearl Harbor occurred. I was sitting listening to the Boston Symphony with my girlfriend when the news came over about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. She was Navy junior and her father was executive officer of the cruiser Northhampton which was stationed in Pearl Harbor. Of course this warranted immediate, direct concern there. We quickly went over to the apartment where her mother was living and told her about that. For the next few days we really didn't know what was happening. We had no news after the war started except that there had been tremendous damage inflicted. As it turned out, the Northhampton escaped damage. As far as that family was concerned then everything was all right.

I wanted to get to sea. I loved the sea and always had since I got introduced to it. So I put in another application to go to sea and got the same kickback because of previous history of eye deficiency. It seems I wasn't qualified for sea duty, even though a large, specially-convened medical board had certified that I was now physically qualified. I talked to the department head, a very senior engineering captain by the name of Tim Keleher, about this.

I said, “Look, I want to go to sea. I've tried everything else. Would you mind if I put in an application once a month for sea duty?”

He said, “Yes, he'd be glad to forward them.” And so he did. This was in December, 1941, and this went on for about four months. Every month I would put in an application for sea duty and it would go around and come back with a little red tag on it saying “not physically qualified by reason of history of previous eye deficiency.”

So, I concocted a scheme. By this time we were having civilian university graduates coming in on the V-12 program. I think there were a bunch of V programs, but, I think it was V-12. These people were putting in about three months at the Naval Academy. They were being commissioned as officers in the reserve in a general duty status.

Now, I was an officer in the reserve, but with a limited duty status. I was presumably not eligible for sea duty. So, I concocted this scheme that I should resign my commission and apply for admission to the V-12 course, request waiver of the requirements for going 90 days since I'd already been to the U.S. Naval Academy, get a commission as a general line officer in the reserve, and then get to sea. I was to try that. That went in and apparently it gave the Bureau of Navigation, which then handled personnel, some pause, because I didn't hear anything for about six weeks. Then I got a letter back saying, “We regret very much that we're not able to do this. However, orders for sea duty follow by separate correspondence.”

They did. the next day I got orders for sea. I was to report to the USS MEADE fitting out in Staten Island.

Since then, I learned the reason why this happened was not because of any change in the higher bureaucrats' hearts, but one of the instructors in the Marine Engineering Department there was a retired officer who had been called back to active duty. He, Red Rule, had become a very close friend of mine and was from the class of 1923 or thereabouts. He was a classmate of Admiral Denfeld who was the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation which made these assignments. I subsequently found out, although he would

never admit it, that Red had talked to Louis Denfeld and this had subsequently been arranged.

At any rate, I went to sea, even though technically according to the Navy Bureau of Medicine I was not physically qualified for sea duty. I reported to the MEADE at Staten Island. I got detached, as a matter of fact, and promoted from ensign to lieutenant junior grade on my birthday, June 17, 1942. I went up to Staten Island and joined the ship up there. It was fitting out; and three or four days later I think, it moved over to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. I was the last one of the officers to report aboard, and all the major positions had been filled. We had about twenty-one or twenty-two officers. Although I was senior to some, they had filled the spots.

Consequently, I was made sort of a expediter, responsible for seeing that things got done. This proved to be an invaluable education in all the aspects of the Navy ships, ship life and navy shipyard life, because I worked with problems in the engineering department, communications, the deck department, gunnery and so forth. Anytime anyone had a problem, I was the guy that was supposed to work it out. I must say that through certain irregular procedures, I very often was able to resolve these problems. Sometimes, this was to the detriment of some of our sister ships.

We went to sea and headed to Guantanamo for our shakedown training. This was about July, 1942. Shortly after we had left New York Harbor about three or four days out, the communications officer suffered a nervous breakdown brought on among other things by the fact that he was a quiet introverted sort of guy. The Captain had been in communications at some time in his past, and he passed himself as an expert which he no longer was. He simply rode the tail of his poor guy until the guy collapsed. So, I got a

call about one o'clock in the morning from the Captain. He said, “As of now, you're the communications officer.”

The communications officer in those days was not only responsible for radio communications, but also for the sonar equipment and the radar. It happened that we had a well qualified warrant electrician who was checked out in electronics technology aboard the ship at that time.

The MEADE was equipped with radar from the very beginning--fire control radar model FD, serial no. about 50, and an early SC air search radar. Nobody knew exactly what to do with them, nor with the sonar equipment, which had mostly evolved as far as technology was concerned from the British. They were far ahead of us. Radar we had worked on and developed it quite well. Even at the time I was at the Naval Academy and teaching there, just before I got orders to sea, it was so secret that we couldn't even get full information on what it was all about. All that we knew was that this was something that would find something out there using electromagnetic waves.

Fortunately, the electrical engineering in one way or another in the Naval Academy was pretty good. I knew the basics and perforce learned very quickly a great deal more than that.

It was a major problem because then as well as now when the first production models come out, they are usually making changes in them so that you don't have a complete instruction book and complete circuit diagrams or anything else. You'll get a complete set of those books, but since the books were developed and printed, they had added some improvements. So, you keep running into things in circuits and so forth that aren't supposed to be there.

We jumped a German submarine on the way down to Guantanamo. There was great confusion. I guess we must have scared him about as much as he did us. At any rate, we parted with apparently no damage done on either side. There was a great deal of noise from breaking china and so forth.

We completed our shakedown training and went back to New York for repairs and refit and whatnot. Just after we got there, we got sudden sealed orders. I was communications officer by this time. Of course I was appointed to get these things, so I got them. There were two envelopes. One said to get underway the next day, and join up with other ships at such-and-such a point, report to the senior officer in command, and proceed as directed in the other envelope which is not to be opened by anyone except the commanding officer personally. So I delivered them to the commanding officer. He opened the other envelope and showed me what it was. He said that I was the communicator and had to be in on it.

These were orders to join the USS WASHINGTON, which was the first of our modern battleships to get out to Guadalcanal. We were to report to Admiral Halsey. So, we joined up. There were three other destroyers; the REID, the BARTON, and the NICHOLAS. Most of the other ships in our squadron had been completed some time before us. The squadron was stationed up in the Aleutians which at that time was the very quiet theater. This was after the initial Japanese invasion. Things had settled down to a stalemate, and we were busy elsewhere. We were just leaving it like that, so this was just a routine type operation.

Guadalcanal was just about to get underway, which was a big and chancy operation. It began just about the time that we came back to New York for our refit. We

proceeded screening the WASHINGTON with the other destroyers and came through the Panama Canal. Instead of turning to the right to head north where our squadron was stationed up in the Aleutians, we changed course slightly to the left, slightly to the south and west which was in the direction of Guadalcanal. Almost immediately about ninety percent of the crew came down seasick, and for very good reasons. Things were tough in that South Pacific Area.

We had, by the way, a ship's doctor who had been an obstetrician up in Rochester, New York. He had a very lucrative practice. So much so that just in past due bills for the first year he was aboard the ship, he received over twenty-five thousand dollars, which was a lot of money in those days. It still isn't bad today. One immediately wonders, “What the hell is an obstetrician doing on a Naval 'Man of War' when there are nothing aboard ship but men?” I was curious about that myself. The reason was very simple. The biggest sorts of casualties aboard ship from enemy fire and bombs and what-have-you were gut wounds. This is where your obstetrician came into play.

Donald R. Lennon:

I bet there were a lot of jokes about this, weren't there?

H.A.I. Sugg:

There were indeed. Anyway, the doctor adapted beautifully at least to the general problems. He didn't adapt to the Navy so well in terms of uniforms and smartness and so forth. He was a marvelous doctor. He was also a fine chaplain, father confessor.

Well, practically everybody came down seasick. So he had the word passed that all those that were not feeling well should report to sick bay, and they would treat them. When they got there one of the corpsmen was standing by to check the symptoms quickly and say, “Yes, we can do something about that.”

Well, he had a very simple and effective remedy as it turned out. What he did was to use a rather large hypodermic needle and inject a rather large amount of sterile saline solution into one of the buttocks of the sufferer. This caused him such pain and inconvenience that he forgot about the seasickness. Well anyway, he cured most of the crew that way before they realized what had happened, because it took a little while before these symptoms set in.

We went on out with the WASHINGTON. We joined a task force of the South Pacific command--I've forgotten the task force number. There was a carrier and some cruisers, and a squadron of destroyers at sea. I might say that we had detoured enroute, not detoured but stopped dead at Tongatabu. We had a chance for a few hours liberty there. We had to replenish and refuel and so forth so we stopped there. I can still remember that island very well. This was the first one of the Pacific islands that I had ever seen. I have always been very fond of that island ever since--I've been back.

Anyway, we left then and joined the task force at sea and proceeded on some operation immediately. The communications officer has the duty to go over to the flagship via boat and get all the operations orders and the special recognition signals and all this kind of stuff, all of which material was classified “Top Secret.” I came back with a stack of things about eight inches thick, mostly onionskins and thousands of pages of standard operating procedures and whatnot. We were still developing carrier techniques at that time. Nobody knew what had to be done. So I got back with these things and came aboard. The Captain was very eager to find out what I had. I said, “I've got this,” and I showed him this stack.

He said, “Well, what does it say?”

I said, “I haven't had a chance to read them, Captain. I got them on the flagship and I came back in the boat and I haven't even unwrapped the package.”

He said, “I want to know what they say thirty minutes from now.”

Fortunately I had learned very early to be an extremely rapid reader. By this time I had learned enough about my business in communication operations. I knew the standards and what not. I flipped through the messages and got the essentials which were recognition signals so that we could tell us from the Japanese in case we encountered one another at night or in other situations. I also got the essentials of the operations orders. This told us what we were supposed to be doing and where we were going and so forth. I weeded those things out and thirty minutes later I had this information for the skipper. That was enough for him. He didn't want to be bothered with details so I took the rest of the stuff back to my stateroom. I went over it and got the rest of it.

We operated with this carrier task force for a while, then the force put in to Noumea, New Caledonia. We were there briefly and then went back to Guadalcanal.

Since our squadron was up in the Aleutians, we were the only one from our squadron in the South Pacific. We caught a lot of special details because all the other ships there were operating with their division or their squadron commanders. We were the only ship down there as far as I know that was there by itself. We didn't have either a division or squadron commander in the area. They were up in the Aleutians. We got all these special details, many of which proved to be very interesting, sometimes a little scary, and most usually hungry.

One of the things I remember best about that campaign around the time of Guadalcanal was being hungry. We were kept on these stations so much and we had rare

occasions to come into port when we didn't fuel at sea, and we would refuel and get whatever provisions the tanker could spare which usually consisted of rotten cabbage and onions. Fortunately, onions kept well, so we usually had onions. Then we got a few other things and off we'd go again. I can remember one time when we ate everything on board including the hard tack in the lifeboat rations until we got back to shore to replenish our supplies. Things were tough down there. Supplies were not coming through. This was a secondary theater as far as our overall strategy was concerned. We had just minimum supplies and minimum ships to keep it going. A destroyer without a daddy, like ours, just had a tough time competing with some of these others who had a squadron commanders that were high rankers, and more senior officers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well what was the nature of some of the assignments that you were getting?

H.A.I. Sugg:

We were sent out to rendezvous at a particular point with a merchantman, with directions to escort it back to Noumea and wait for further orders. This is off in the direction of the East Indies quite a bit and we had to go pretty far out to rendezvous with this merchantman. We didn't know exactly who it was. All we knew was that we were supposed to be there at such and such a time to rendezvous with the merchantman. It turned out to be a Dutch merchantman that had escaped from the Japanese in their invasion of Southeast Asia and Indonesia. It was a general cargo ship with food supplies and various things like that. Mainly, we needed ships. So, we rendezvoused with him and immediately communicated with them.

As communications officer, I was sent over and spent a very pleasant two-and-a-half weeks as liaison officer aboard this merchantman. They had provisions like you wouldn't believe: beer, distilled spirits and whatnot. The skipper was a jolly Dutchman

who must have weighed close to three hundred pounds, pink, round and jolly. He always wore spotless white shorts, and a white open neck short-sleeved shirt. He was the only one that spoke any English, and he spoke very little. I knew French rather well at that point. I was certified as an interpreter. He knew French, so that was how we communicated. The destroyer was screening the merchantman against submarines. We took her back to Noumea.

Another time later on after we had gone through a couple of battles up there, the Marines got in very desperate straits because of the Japanese air attacks. They needed supplies. General Griffith who was commander of the Marine division there, sent a signal to Admiral Halsey, saying, “I have less than twenty-four hours supply of fuel left. Unless I am re-supplied immediately, I cannot assure that I can hold out against the Japanese attack.”

The Navy down there was doing everything. They flew aviation gasoline up there and planes, anything they had. They sent it up by every conceivable surface means. They put it on destroyers--deck loads of fifty-five-gallon drums of aviation gasoline.

We got the assignment to do that and take a deck load of aviation gas and aviation bombs up to the Marines in Guadalcanal. We left just after the MEREDITH, which was sunk by the Japanese.

There are two things about it. Destroyers of the particular class--the Benson-Livermore class like the USS MEADE, DD 601--are notoriously tender and top-heavy. You get a big deck load, and they really have very little stability. The other thing is that the combination of aviation gasoline and bombs is not the greatest thing to have around in

addition to your own ammunition stocks when the Japanese bombers and submarines start going after you.

Donald R. Lennon:

Especially with the unstable deck load.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes. Just after we left the harbor we got a change of orders that we were to escort a small tanker up to Guadalcanal. This turned out to be a little harbor tanker loaded with about fifteen thousand gallons of aviation gasoline, which was a rather large amount in those days when planes were somewhat more economical than they are now.

My future brother-in-law was commander of one of the Navy aviation squadrons at Guadalcanal at that time. He was Commander William E. Ellis. His carrier had been sunk, so his squadron had been put ashore at Guadalcanal. I didn't know him at that time.

Anyway we picked up the tanker and headed up at a very slow speed because it wouldn't make much speed. We were about a day out of Noumea when we got word that the MEREDITH had been attacked. She was sunk with the loss of nearly all hands. A very close friend of mine got a Congressional Medal of Honor out of that. She had been loaded with the same stuff as we were, and this was just a few hours ahead of us. We also got a very encouraging message from Commander South Pacific saying that they had intercepted Japanese orders to all submarines to concentrate in the approaches to Sea Lark Channel which led to Guadalcanal. It was a channel between Guadalcanal and Tulagi. There were Japanese air attacks several times a day, waves of bombers going on all the time. It was a rather noisy situation. We got up there and we got into Sea Lark Channel. We were under continuous contact with submarines for about twenty-four hours. Our poor little old tanker couldn't do anything to evade. He just plodded steadily ahead and we would get a contact on a submarine, depth charge him and force him down. We didn't

stay to see if we had really done any damage. As soon as we figured we had driven him off for the time being, we would catch up with the tanker and go on. We were under almost continuous contact with submarines for about sixteen hours in the approaches to Sea Lark Channel.

Donald R. Lennon:

None of them tried to torpedo you?

H.A.I. Sugg:

None of them hit. We saw some torpedo wakes, but none of them hit either us or the tanker.

We got up there about mid-afternoon, and we were under almost continuous bombing attack from then until dark. We were shooting at the airplanes and dropping depth charges on submarines.

It was a very busy time, especially for me, because my battle station was as officer of the deck at general quarters. I was conning the ship. Also, as the communications officer, I was responsible for the radar and the sonar, both of which were crucial in what we were doing in both directions. About 4:30 the sonar went out and about 10 minutes later the damn radar went out. Here I was trying to get the sonar and radar fixed, and we were under continuing attack. It was a very busy few hours, I must say. I managed to do it one way or another. By then we had lost our expert warrant electrician, so I was having to do this work myself.

We finally got to the approaches to the area between Tulagi and Guadalcanal the next morning. We received orders that we were to deliver the tanker to a base south of Henderson Field, which was the major air field supporting the Marines where my future brother-in-law was operating his Navy squadron. We were to deliver this tanker to a bay

somewhat east and a little south of there where there was to be an emergency airfield established.

We left the tanker outside and went into this bay very cautiously and discovered there was nobody there except Japanese. They were very well prepared for such an incursion. We got a very heavy artillery fire from them, which we replied to and managed to avoid any difficulty. We promptly withdrew and radioed up to Henderson to say that we had just taken a look and there was no airfield in this particular bay as yet. We took the tanker up to Tulagi and turned it over to the Captain of the Port there and went on about our business.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you unload your cargo?

H.A.I. Sugg:

We went over just offshore of Henderson Field and off-loaded the aviation gas and bombs there.

Then we got some other assignments which were quite interesting. We worked with PT boats and we worked with the people who have been immortalized by Michener in his Tales of the South Pacific. I know most of the characters in that because we worked with them in that area.

From there we went, I think, to the Aleutians via a brief stop in Pearl Harbor to be refitted with some more up-to-date radar. We spent several months in the Aleutians.

I believe our next operation was the Tarawa operation. We came back from the Aleutians and made a brief stop in Seattle The attack troops were loaded out of New Zealand. I forget if it was Wellington or Auckland, but I think it was Wellington, New Zealand, where we assembled. We went up to Tarawa, and we were designated as a gunfire-support ship. We had done quite a bit of that at Guadalcanal.

After the third Savo battle at Guadalcanal, we were the only American warship left in the area. That was a rather disastrous battle for us. We were the only American warship left there, and it was a rather unnerving situation. We had done a lot of fire support of the Marines on shore while we were there at Guadalcanal.

We did a lot of gunfire support in the Aleutians in the Attu campaign, supporting Army forces. We operated in an area called Murder Bay in Massacre Cove, a very lovely bay.

We operated very close inshore, and it was there I got my only wound in the war from a rifle bullet, a sniper from onshore. We were in that close. It hit me just about the middle of my helmet and knocked me against the bulkhead and I really thought I had had it, because I felt this searing pain in my back. I really thought I'd bought the farm. What had happened, the helmet had deflected the round just enough so it just merely creased my skull. I have a very thick skull, I guess. The round then hit the bulkhead behind me and hit one of the steel supporting members which stopped it and bounced it back and it had dropped down the back of my collar. It was red hot with the force of the impact. Of course it was just a red hot bullet that was dropping down my back, and that was the searing pain in my back. I was directing our gunfire on targets for the Army at that time using a voice communication field radio with the Army artillery. This shook me up a moment, but then I discovered I was still operable so I continued just what I was doing. I never did get down to sick bay and I never got a Purple Heart out of that one. Technically I might have qualified since I was wounded. I guess sometime somebody came by and stuck a band-aid on my head. That seemed to be enough.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you get the bullet that went down your back?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes. I carried that around with me for a couple of years. I also kept the helmet which had been rather badly creased.

Anyway, we did a lot of gunfire support up there. We developed it in real expertise. Here again the technology of ships supporting naval forces was still very new. The notion was old--this goes back to the time of Nelson and before. With the new equipment and the new type of things, we still hadn't developed standards and operating procedures. So, this was very much in the developmental stage. We did so much of it that we developed a very professional outfit.

As a consequence, we were assigned as the destroyer at the line of departure at Tarawa. This was about four thousand yards offshore. This was in easy range of the Japanese. Our job was to cover the waves of landing craft as they went in. We were to do this until the preliminary barrage had been lifted. We also did that in the Marshall Islands, and several other places. We always got this job of being close into shore and covering the first wave. It always reminded me of Mark Twain's comment about the man who is ridden out of town on a rail, “If it weren't for the honor of the thing, I'd rather not.” We managed to do our job even though sometimes it got a little hairy.

I think it was at Tarawa or maybe the Marshalls that after what seemed to be an absolute obliterating bombardment by heavy bombers and naval battleships with sixteen-inch gunfire and whatnot, the initial waves went ashore with hardly any opposition. The next morning a whole host of Japanese artillery batteries within concrete pillboxes came alive. We were supporting a battalion of Marines as they were moving down the island. We were rather close inshore and keeping more or less abreast of the front line so that we could lay down fire ahead of them conveniently. One of these batteries woke up and

started shooting at us. This is not really fair, they should have been shooting at the Marines.

We had a skipper who had a very interesting theory about getting shot at, and that was that the safest thing to do if the enemy shot at you and you were straddled was to close the range, because he wouldn't expect that. He would expect one to go the other way. His theory was to close the range.

So every time we got straddled, we would make a U-turn towards the enemy. We worked up and finally knocked out that pillbox which we subsequently found six-inch guns in, if you can believe that. It had a present range of eight hundred yards. What happened was that we got a lucky shot down into one of the gunports.

Donald R. Lennon:

You could go in that close with a destroyer?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, in these islands, you had deep water right up to the reef. Here the reef was right up next to the shore. So we were right alongside shore; and, at the point that we finally knocked that guy out, we were at a present range of eight hundred yards from him just shooting point blank at each other. I had a ring-side seat then as I always did as officer of the deck at general quarters in conning the ship. The captain would tell me what to do and I'd do it.

We went from there to the Marshalls. We got involved in several scraps with the Japanese shore batteries there in which the captain applied the same techniques until we got ordered off then by the admiral in command.

We fished a bunch of aviators out of the water along there. All in all I think we picked up over a hundred aviators which had been shot down. During some of these pickups, as we did at Guadalcanal and later at Tarawa and in the Marshalls area, we

would have to go very close inshore, practically to the surf to pick these guys up. There we would come under Japanese shore-based artillery fire and small arms fire and the like. So, it was a pretty chancy thing.

They had put a pretty high value on aviators. I never realized this so much until we picked up one that had been shot down over Wotje, which is a rather quiet place to even be shot down. We had been sent up to keep an eye on planes that were being sent in. This guy got shot down and went in about to the surf. We could see him in his life vest and so forth. There was a very heavily defended island nearby, Wotje I believe it was. The captain ordered us in at max speed which was about thirty-five knots. We went dashing in with one of the boats rigged out and ready to go. We got in, and what he was going to do was to go in and drop the boats, and go out on a smoke screen. As soon as the boat had recovered the aviator, we would go back in and pick the boat up. Well, the Japanese fire was so intense that we couldn't get all the way in. So we went back out and made another run. This time we just went all the way in and picked the aviator up over the side of the destroyer. We didn't even put a boat in the water. This was just almost in the edge of the surf there. We got out, and fortunately without any damage. The first thing that so-and-so said when he got on board was, “What's the matter with you yellow bellies that you didn't get me the first time?” I tell you that was one aviator that damn near got thrown overboard by the U.S. Navy. Anyway, we had three hundred men and officers on that ship and we were going in to save this so-and-so. He was the only one, I might say, that ever acted like that, but I can still remember what he looked like.

We picked up one aviator three times. He got shot down three times on various operations and we picked him up. This was in a relatively short space of time. He made

a name for himself and was featured on one of the national magazines, Colliers or something like that. He was always very grateful. He would say, “This is one habit I should get out of.”

We got involved in the Hollandia operation down in New Guinea. I've forgotten the exact time sequence, but we were still operating independently of our squadron. We were then attached to the squadron commanded by Arleigh Burke, “31 Knot” Burke as he was known then. We went in on a high speed run and something happened to one of our boilers. We had all four boilers on the line for maximum speed, and some way or another we blew a tube on one of the boilers.

The engineering officer was Willie Grimball from Charleston, SC, who is now a circuit judge or something like that. He had a law degree when he enlisted and told the Navy he wanted anything but engineering. So they sent him to engineering school, and he made a darn good engineer. He preferred law though and is now back in law. His is a distinguished family from the Charleston area. His father was a judge and I think he has a brother who is a judge in one of the U.S. District Courts down there. But, when this boiler broke down, he was chief engineer officer.

We had to slow down. The skipper had to signal then Captain Burke that we were unable to make the thirty-five knots that we were supposed to make and requested to reduce speed to thirty knots. I can remember after we finally got the thing squared away and we were really going again, Willie Grimball saying, “Well, I think I may go down in history as the guy that reduced 'Thirty-one Knot' Burke to 'Thirty Knot' Burke.”

We were in on the Hollandia operation which was basically an Army operation. Then we were assigned to join some of the task forces that made strikes on the Japanese-

held islands of Palau, and so forth, to the west. We went on then to the Marinas operation, Guam, Saipan, Okinawa, and then the Philippines.

I was detached in May, 1945, in Lingayen Gulf on the western side of Luzon Island in the Philippines. I was to go back as executive officer of a new destroyer in Orange, Texas. The crew was being trained in Norfolk.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you had been on the MEADE all the rest of the time?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes.

I went back there and had a little leave and then took over my crew in Norfolk and trained them. Just about the time I had them fully trained and ready to go, the ship, which was the Brinkley Bass DD887, was delayed a couple of times on its completion date. So I gave my crew all the training I could think of including close-order drills and small arms practice, and soon I ran out of drills to give them. I talked the commander of the base into letting me give them two weeks leave because they were really trained to a “fair thee well,” and the ship wasn't ready. I had one of the finest trained crews here that one could have wanted. I was really looking forward to going to this ship with that crew. So, we had two weeks leave.

I took the occasion to get married and go on my honeymoon. I married a Navy junior, Suzanne Dupuy Decker, who was the daughter of Commander Walter B. Decker, Class of 1906. I had known Suzy when she was a freshman at college. This was before I went to sea. I wrote my sister that I had orders back to Norfolk. She wrote back and said when you get there be sure to look up Suzy. She's grown up and is quite beautiful. I did, and she was, and I married her. We were married on the eleventh of August at the Naval

Academy Chapel with Chaplain Thomas presiding. He was the chaplain when I was a midshipman and he was the Chief of Chaplains in the Navy.

We went to Texas and commissioned the BRINKLEY BASS in Orange, where it was built by Ingalls. I am probably the only person around that has ever personally owned one U.S. destroyer. There was a problem with crews coming down and they had to be quartered. There was just a small number of barracks until they were filled and then they would go aboard ship when the ship was ready for them. This could happen only after the ship had been accepted by the Superintendent of Shipbuilding there for the U.S. Navy. Until then it would belong to the ship builder and he wasn't about to have anybody quartered on his ship because of the liability and so forth.

Well, we got down there and somebody had made a mistake and shipped another crew down right behind us. Our ship wasn't quite ready. We would have been ready in about another week. Here comes this other crew down about forty-eight hours later and there was no place to put them. The question then was what to do with them.

Well, our ship was about ready for the crew to go aboard anyway; so, the Superintendent of Ships, then a Navy captain, asked the builder to let us go aboard and put our crew aboard.

The builder said, “Hell no. Not until you accept the ship.”

The Superintendent of Ships wouldn't accept the ship. They came to a standoff; and, somebody finally came up with the idea that if the ship-building company could transfer custody officially and legally to someone else who would let the Navy put sailors on the ship, that would take care of the problems. Well, they elected me. They came out and said, “How would you like to have a destroyer?”

I said, “Well, what can I say?”

I don't know whether or not I still have it, but I used to have a receipt that I signed for the ship stating: “One U.S. Destroyer,” and the cost. It cost eight million and so many hundred thousand dollars. Those things were cheap back in those days.

So, for about four days, I personally owned that destroyer. Of course, my mortgage was slightly large.

Donald R. Lennon:

What would have happened if something had gone wrong?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, according to the law, I would be legally and personally and financially responsible for the loss. I knew my crew and figured that there wasn't going to be anything like that. Legally I would have been responsible for paying the Navy back eight million bucks. Actually, what happened in a situation like that was that you got a private bill introduced into the Congress which in the absence of culpable negligence and so forth relieved you of this financial responsibility. I really didn't have to look forward to spending the rest of the my life paying off that eight million dollars. For four days, though, I owned that ship. As a matter of fact, I took advantage of that to tell a couple of captains where to get off my ship. This was not the smartest thing to do then, but I surely enjoyed it.

In the meantime while we had been on this two weeks leave, the war ended. So we got back to the Norfolk Naval Base, and I had this beautifully-trained crew and about two-thirds of them had enough points to be discharged immediately. There went two-thirds of my crew. They refilled the numbers, and I started training and got another outfit fairly well-trained. They had sent me people who mostly were almost up to their points

for discharge. They came up and got enough points, and so I lost about another two-thirds of my crew.

I finally got a bunch of raw recruits. I trained them as much as I could. Then we got ordered down to Texas to put the ship in commission. So I went down there and was the only officer other than the commanding officer who had had any experience aboard this type of ship before. The gunnery officer and engineer had been aboard smaller ships, mine sweepers or something like that. None of them had been in action. They were very junior. They were very competent; they just weren't experienced. They usually gave you about twenty-five officers with experience down the line, including a couple or three lieutenant commanders and so on down the line. As it was, we had no one with any experience in this kind of ship and the jobs that they were doing.

First of all we had to go out on a SAR (Search and Rescue) mission out in the Gulf of Mexico without any of our compasses working. Our Gyrocompass was not working. This hadn't been finished yet. Our magnetic compass had not been compensated. So, we didn't really know which way was north. I told the skipper, “I feel I can get us there and get us back one way or another.” So, we went off and did it. We did get back.

In the meantime while we were there in Orange, about thirty percent of our crew came up with enough points to get out. I told the Captain and he agreed with me that we ought to let these guys go before we went down and spent six weeks training in Guantanamo. We sent a message to the Bureau of Personnel requesting a delay until we could replace our personnel with somebody that would be there for a while. They said no. So we went and shook down at Guantanamo. Half of our crew should have been

released on points before we left. This was not the happiest of situations for them. I had done everything that could be done. I finally said, “To hell with the Navy Department.” I called senators and congressmen and talked to them about it, but nothing could be done. I kept the crew informed. I mustered them all after we got underway and said, “Look we've got orders to go to China as soon as we finish this and get refitted. Some of us are going to be out there for a year or more. Some of you guys should have been off. You know what I've done to try and get you off, but you are with us and you can do one of two things: you can either help us train the rest of guys who are going to be here and do a good job of it or you can goof off and we'll have a problem for the rest.”

We made the highest marks every made by a destroyer being shaken down in Guantanamo. In the process I collected myself a nervous breakdown and spent several weeks in bed.

We went back to Charleston briefly and then headed out to China. This was the time when demobilization was in full swing, and it was an extremely chaotic process. Ships were tied up all over the world because they didn't have enough people. The Navy, nor the Army for that matter, had not figured the war would be over so soon. They didn't have any effective demobilization plan. They came up with some rules that said when a guy has been in so many months with so many points, you are going to have to let him go.

When we got out to China, there must have been twenty-five ships, cruisers on down, tied up in the Whangpoo River that couldn't get under way because of shortage of personnel. It was really a chaotic situation.

Before we had left Charleston, I took a look around and saw a lot of people there who were careerists. There were a lot of ships there that had been ordered into the

reserve since the war was over, so I took a little check around and found a whole lot of people who were career Navy who would like to go out to China. It had been a real good station before the war. I got permission from the Bureau of Personnel to make exchanges with any of these commanding officers that would be agreeable to it where the men were agreeable.

I put out a bulletin that anybody that had so many months obligated service to check with his commanding officer and to check with me to see if we could arrange a deal. I arranged deals that involved about 25 other ships and I wound up with over 300 well-qualified sailors with at least twelve months obligated service. So we left Charleston with people who had volunteered this time, and we went out in great shape.

We got out to San Diego and things were still tough. We were hearing worse and worse horror stories from China. I figured that the Commander of Destroyers of the Pacific wouldn't be too well cut in with our situation, so I went over to see the personnel officer and gave him a sob story and picked up another 150 recruits. Of course, they had obligated service of eighteen months or longer. We went out with people jammed into every nook and cranny. We were over fifty percent over our complement.

Immediately when we got out there, we started getting orders to transfer three men here, two men there. I knew this would happen; but by the time I left the ship about six months later, we still had enough of a crew that we could still operate. We were about the only ship in Far Eastern waters that could do that.

Consequently, all we did was operate. We picked up pilots. We salvaged merchantmen that had hit reefs. Our home port theoretically was Hong Kong. We never got there. Every time we would head for it, we would get orders to go look for

somebody. It was interesting, but we didn't have liberty. We did get into Shanghai for a while and operated out of there for eight or ten weeks. I got a chance to see a bit of Shanghai, Tsingtau, Taku Bar, and Tientsin. We used to deliver the mail up there.

Then I was transferred to the Navy Line School. That had been altered for reserves because a lot of the reserve officers had not really had adequate training. This was designed to catch up lieutenants, people with good war records, who in the haste of mobilization training had not picked up the usual skills of navigation , gunnery, etc. I was ordered up there even though I had gone to the Naval Academy. I protested, but it didn't do any good. I went up and spent most of my time playing badminton and swimming, trying to get myself physically back into condition. I was down to less than 150 pounds and living on aspirin and coffee and was in pretty bad shape. I improved a little.

I had decided by that time that I wanted to teach, so I resigned. I had been admitted to several schools, including the University of Virginia. I'm a little hazy about this particular thing because this was a very bad period in my life, but I intended to go to Virginia and ultimately go into college teaching. Because of the personnel shortage, the Bureau of Personnel didn't even answer my letter resigning my commission.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you first went on active duty, you were a reserve officer.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I was still a reserve officer, a lieutenant commander. We had the choice of electing to go regular Navy or get out. I decided I wanted to teach. I had enjoyed my two years teaching at the Naval Academy.

They didn't even bother to answer the letter; they just sent me orders to command the CARMICK, a destroyer-mine sweeper out at San Diego, DMS 33. I loved the sea; I

loved ships; and I loved destroyers in particular. I couldn't turn that down. I took command of the CARMICK in June of 1947. I arrived short of crew. They marched about eighty recruits on board the day I was scheduled to leave, and I took off for China. We carried out every mission we were assigned one hundred percent. Everything except main engines broke down on the ship, and we fixed it.

When we got back I had one hell of a fine crew. A lot of people's enlistments were expiring; and the Bureau of Personnel in its infinite wisdom had seen fit to require the commander to personally interview each man that was due for expiration of enlistment, to try to recruit him. My recruiting speech was very simple. These poor guys had been out with me about nine to ten months in the Far East and just worked their tails off. We had gone through typhoons, run between Guam and China, Tsingtao, and Yokosuka, and just gone and gone; but we had a crackerjack operating ship when we got back. We looked smart. When we got back to San Diego about half my crew was due for re-up. I made my recruiting speech. It was very simple. “You stupid bastard, you've been with me for a year or more. You know that you've worked your tail off and gotten damned little liberty, leave and recreation. If you want to sign up for another four like that, I would be glad to have you.”

My re-enlistment rate was forty-nine percent, the highest in the whole damn fleet. The fleet average was less than ten percent. I had the only ship in my squadron of eight ships, when we got back, that was able to operate. The rest were tied up and couldn't operate. Almost everyone had more people on board than I did. I had a ship that operated.

I had applied for Russian language school. While we were in China, we had been sent up to Manchuria, off Port Arthur, to pick up a Marine aviator that had been shot down by Soviet anti-aircraft fire. The Russian shore batteries opened up on us, but did not hit us. A lot of things were going on like that all over the world. The Russians were distinctly hostile. Right then and there I decided who the enemy was so I applied for Russian language school at the Naval Intelligence School. I got back a letter that my credentials were impressive but I was over age. Nobody over thirty was accepted because of the rigorous nature of the school. It was physically too demanding of anyone over thirty. I sent word back saying that I was in pretty good shape and that I was interested. I got orders to interview with the commanding officer of the school. I can't remember his name (maybe Captain Hindmarsh) but he had originated the Navy and Army language training out in Boulder, Colorado. He was a Navy captain and had been up at Harvard.

His theory was what Berlitz later termed the total immersion thing. You were totally immersed in the Russian language, six and one-half days a week, eighteen hours a day for nine months. When you came out of that you spoke the language pretty well. That was the reason for the age limit. I came back, interviewed with the guy and imagined I could hack it. Finally I was accepted.

We rented a house in the Washington area. I carried my wife over there. I had hardly seen her since we were married in 1945 and this was 1948. We had a kitchen table, four chairs, and a bed--that was the sum total of the furniture. It was a two-story, three bedroom, full basement brick house. I put her in with her suitcases and said good-bye. I lived at the BOQ at the Intelligence School for nine months.

After that I was assigned to the Naval Security Agency which is a special communication intelligence sort of thing. After merger of the armed forces security agencies into the Armed Forces Security Agency, I was transferred to Arlington Hall Station where I was assistant head of a very large division of about three hundred officers and civilians.

I happened to have the station duty the morning in June when the North Koreans attacked South Korea. That was Sunday, I believe, and the next day I went down to the Bureau of Personnel to see about getting a ship. They said absolutely not. We would love to have you, but you are frozen in your present job until you are released. As far as we know it will be another year. I did everything I could but this was it because the outfit I was in had a very high priority and I was stuck.

Two days later, the need came up for a special communications project in Japan in connection with the war which was heating up in the meantime. By then President Truman had committed American ground forces about forty-eight hours after it happened. I went to see the Deputy Head of Station, a naval admiral whom I had known over the years, Rosy Mason. I went up to see him and said, “We've just got this requirement in for this special project in Japan and they need it now. They need one qualified officer and a couple of junior officers and some technicians.”

He said, “Well who have we got that can do that?”I said, “We've got two people. One has eight children and his wife is now pregnant with their ninth, and the other one is me, and I'd like to go.”

I said, “If I can't get a damn ship, I'd like to get out close to the war anyway.”

He looked at me for a moment and said, “All right, get going.”

On Thursday after the Monday I was told I was frozen in Washington for another year, I was on a plane bound for Japan. I got out there and reported to Com Unit 39, at Yokosuka and set up this special project. As a result of a number of factors, I shortly afterwards took over as executive officer of the Naval communications station com-unit there. It was in the throes of very rapid expansion. We went from about seventy-five people to 750 men and 150 officers in a period of about four months. I presided over that.

I had a number of other duties. I was the Base Duty Officer from 4:30 in the afternoon until 8:00 the next morning every fourth day. Four of us lieutenant commanders were singularly blessed. There were a hundred lieutenant commanders, but four of us did all the base duties. I just reorganized the whole damn base which was very chaotic. I went to the admiral and bypassed every captain on the base and got in a lot of trouble about it, but the thing got squared away.

While I was out there, the Navy decided to combine all the Navy communications activities in Japan which were under separate commands into a single Naval Communications Facility. I was given additional duty orders as the acting executive officer to organize this thing and get it running until a commanding officer and a regular executive officer would be designated. I did that and we had about thirty odd activities with quite a few thousand people and a lot of equipment scattered all over Japan. I organized that and got it operating. Then a senior captain, Wesley Wright, came out and took command and asked for me as his regular executive officer. People in the detail office said I was too junior. They sent a senior (but rather stupid) commander out to be the regular officer of this outfit I had organized and run for some time.

In the meantime, the Navy gave me orders to command a communications station at Recife, Brazil, where we had a big communications station. This was rather unusual because I was a line officer, eleven hundred designator. Up to that time only communication specialists, sixty-five thirty MOS, had commanded those. This was one of the reasons I wanted to get out of the outfit. First of all, as an eleven hundred, I didn't want to switch over to special designator and I couldn't go anywhere as a line officer by the precedent. It was very surprising to get the order to Recife, because I thought I had alienated everybody who had anything to do with good jobs in the outfit.

About the time I was ready to leave Japan, my orders were cancelled, and I was ordered to proceed to the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth. Why I got those orders, I've never known. I was the only Naval student. There were eight Marines and 650 Army personnel. I graduated number seven in the class.

I went from there to the Staff of Commander Amphibious Group Four as the gunnery officer and nuclear weapons officer and an additional duty as a logistics officer. That staff had a very interesting situation because we had no ships under our administrative control. Amphibious Group Two was the administrative amphibious group that had all the amphibious ships under its administration and control. We were purely planning and operational staff. We planned an operation; the ships would be assigned; we would run the operation; but we had no responsibility for administration, which was great. I was there from 1952 to 1954.

In the meantime I had gone through the Naval gunfire officer course at Quantico right after the Army Command General Staff College. There I was a contemporary of the

commanding officer, Lt. Colonel Robert D. Heinls, who was a well-known writer. I had been in the Naval gunfire business as long as he had and knew more about the Naval end of Naval gunfire support than he did. We had some very interesting arguments about that, but we wound up good friends.

I went to the amphibious group staff. We did a lot of experimental operations, some of which included almost the entire Atlantic Fleet. The admiral was assigned to be commander of the largest NATO Naval operation that had ever been conducted at that time call “Weldfast,” which was conducted in 1953 in the Mediterranean. It involved a major amphibious landing in the northeastern part of Greece, up in Macedonia. It involved British, French, Turkish, Greek, Italian, and American ships. I was the gunnery officer and nuclear weapons officer. We were one of the first naval outfits to develop some tentative tactics for use of nuclear weapons in connection with amphibious operations. We had done some exercises involving that. This was the first major NATO exercise which involved simulated tactical use of nuclear weapons on the beachhead. I was also the logistics officer for the staff. We had a small staff. It was really lean, so I had these three major jobs. It was really a problem because the fire support control center which I had, had to do the planning and control all the Naval gunfire and the air support during the landing phase. The nuclear weapons officer had to plan that in conjunction with the Air Force and NATO which was involved as well as our Navy planes. I also was responsible for the logistics support for this whole damn fleet, from the time the operation got underway until it ended.

There were a number of problems. First of all, NATO and the Air Force doctrines simply wouldn't work. They were designed for land warfare and a much slower moving

situation and it simply wouldn't have worked. So I had to go to Paris and fight with the Air Force and NATO people about that in order to get them to modify their operation technique. At that point, the NATO Air Force, which meant the U.S. Air Force, doctrine just hadn't been developed to encompass amphibious operations like we were doing.

This was a major operation with several divisions of troops. We had Greek, United States, and Turkish Marine and Army personnel and we had a tremendous fleet. It was the biggest NATO operation that had ever been run up to that point. There has since been one larger, but this was a very large one.

I talked the Air Force into modifying their operations, especially the procedures for releasing nuclear weapons for use, which was the real stumbling block.

I discovered that the agreements we had with our NATO allies about logistics support did not include for anybody, except the British, provisions that a ship of another country could come alongside and fuel and replenish. We would just send them a bill and they would pay it. This had been made on an ad hoc basis as necessary before, but there were no standing procedures. We had French, Italian, Greek, and Turkish ships that had to be supported. I had to fly around to all those capitals and negotiate agreements so they could replenish from us and we could get paid for whatever they used. This was very interesting. There were no big problems, and I had a lot of fun. I met a lot of nice people and saw a lot of nice places. We got our plan ready.

One interesting aspect of that was my admiral, “Weary” Wilkins, was the brother-in-law of Marine Brigadier General Bobby Hogaboom, who was commander of landing forces. (The general's younger brother was a classmate of mine.) They married two sisters, and there was intense competition between the sisters apparently. This made for

the worst possible situation in planning. Our planning staffs got along fine; but these two guys, when one would propose something, the other one would turn it down automatically. We just about went crazy. We didn't finish the damn plan until after we were underway. Because of the delay, the op plan had to be airlifted around to everybody on account of this rivalry between these brothers-in-law. This rivalry was actually from their wives. They were at the root of the whole thing. Anyway, overall, it was a lot of fun. Naples is a great place. It had its advantages.

Well, once the thing got underway, they were going to have a rehearsal at Cyprus, I believe. I was detached and sent down to Athens as the liaison officer to the Greek National Defense General Staff. Since the exercise was going to be run in the Aegean primarily with landings on Greek territory and one thing or another, this was felt to be worth sending a fairly senior officer. I spent several weeks, delightful weeks in many ways, there working as liaison officer for the Greek National Defense General Staff. It turned out that they didn't really need all the liaison work. I would check in about 9:30 in the morning so as not to disturb their beginning, and they knocked off work about one o'clock. I would depart about ten thirty so that I wouldn't interfere with closing shop. I'd go over to the Grand Britannia or King George across Constitution Square. I would have some Turkish coffee and read one of the French newspapers and so forth.

It could have been a really delightful thing except that my next younger brother, who was a Naval aviator, had crashed in the Mediterranean just a few days before I was sent down there. His body was never found. We were very close. We had been on liberty together, as his carrier and our flagship had both been in Naples. We had gone down to Herculaneum, and gone over to Sorrento and Capri and so forth together. We

came back the night before we got underway for ten days operation after which we were going to meet up at the Hotel Martine and do something up there. But, he crashed on an exercise three or four days later. About a week later, I had to go down to Athens. So, I was not able to take full advantage of that otherwise lovely situation. I did enjoy it. I met a lot of grief before I saw the sights. I didn't do nearly everything that I wanted. I came on back and ran the operation. It went off very well, the whole thing considered.

I came on back and went through another admiral. “Weary” Wilkins was the second admiral that I worked for there. The first one was Savvy Hoffman from the class of '25. “Weary” Wilkins was about the class of '30 or thereabouts. Robert Lord Campbell was the third one that I served under on that staff. All three were very fine admirals, I might say. We did a lot of experimental work developing new techniques for Naval gunfire support and one thing or another like that. We had a really tremendous time.

It came time that I was about ready to end my tour. I liked to go to sea on ships. I didn't like shore duty or staff duty. I would always put in on my duty request for the sea or overseas duty. I had had a command which qualified me for a promotion and this sort of thing. I still wanted to get to sea. I kept asking for command of another destroyer. They kept saying no because they had too many other people that needed it.

For some reason or another out of the blue, I got orders to command the ROBERT L. WILSON, DD 847. It had been modified for ASW work and was an ASW destroyer. I got command in 1954 just out of the blue. Of course, I was overjoyed about that. I relieved a good friend of mine, Hy Smith, from the class of '33. I had known him for many years previously. I took command of the WILSON in Taranto, Italy. We were

based in Norfolk, but spent most of the next two years in the Mediterranean in the winters and in the Caribbean in the summers, the same thing that I had been doing on the amphibious staff. Anyway, I had a good ship and some good duty. I had two tours in the Mediterranean, when I was on the amphibious group, and two six-month tours when I had command of the WILSON. I saw a lot of good places around the Mediterranean which I enjoyed very much and got a lot of good training.

A destroyer is a marvelous command. It's big enough to be more or less impressive. It's got a lot of power; it's speedy, slick-looking. It maneuvers and handles sort of like a motor boat, if you know how to do it. It's got that kind of power that you can do it. You can thread a needle with one of the things if you know how to do it. I've threaded a number of needles.

One thing I say, and while I'm not overly humble about all the things that I've done, and I've done a great many things and done a lot of things fairly well, is that I am a very good destroyer skipper. I was in them for I don't know how many years and handled them in all kinds of situations all over the Pacific and Atlantic through typhoons and hurricanes and things like that. I knew my onions about that. I loved it. You get to know your men and officers.

An example of this, on the WILSON, we were ordered to join the task force to take this midshipman cruise one summer. Then Rear Admiral Arleigh Burke was Commander of Destroyers in the Atlantic. He called for commanding officers of the destroyers to come up to Newport where his headquarters was for a conference before we went off. My God, you'd think that the Navy had never run a midshipman cruise before. They had a bunch of people in the Bureau that apparently hadn't been on one, so they

started without looking at the files. They goofed up the whole thing. We had to change and lay the whole thing out after we got underway. I had lunch with the admiral and his chief of staff one day which happened to be the day that he got orders to become the chief of Naval Operations. I was one of the first outside of the Naval officials to know that. He told me during lunch. The Navy really dipped down into fairly junior ranks to pick him up and this caused a lot of consternation among the more senior officers.

We went on this cruise and had a lot of fun with that. I didn't get much sleep because when I started, none of my officers had much if any sea-going training and I had to spend most of my time on the bridge. I trained them damn fast.

We frequently were going alongside of another ship. We had to do a lot of transfers from ship to ship underway, such as getting mail from a cruiser. On Sundays a chaplain would transfer around, and also personnel were transferred from day to day. So, we went alongside ships about three or four times a day. This was a rather ticklish maneuver with which I was very familiar. I was training all my officers to do this. I would let them have the conn to do this. We did it so much, they all qualified including the supply officer.

One of the third class boatswain mates that was stationed on the bridge on the going alongside details, a very smart and very brash youngster, had been watching. His station was always there behind the helmsman. He got to where he could see what was going on. I knew enough and felt confident enough about it that I let the kids go when they would come in, all I would tell them was don't hit the damn guy. If you make a bad approach, come off and do it again. Very rarely did I ever take the conn away from the officer of the deck. I would let her go until the last hair's breadth before collision. Once

or twice I had to do something. This third class boatswain mate was standing there, and he watched this for several weeks. I heard him talking to one of the quartermasters one day while one of the young officers was going alongside and making a mess of this thing. He wasn't endangering anything, so, I was not even out in the wing of the bridge. I was in the pilot house there and sort of watching from there. I heard this boatswain mate talking about this. He says, “God damn-it, you put your helm over.” He was anticipating what the conning officer ought to do in that sort of situation. Whoever it was, the officer messed it up. So, he just pulled off and started around for another turn.

I caught him and said, “Look, you've been getting some coaching from the stands back here. Now, this is no reflection of you at all, but the boatswain mate so-and-so thinks he knows how to do it. I think maybe he does, but I'd rather put it on him. I'll give you another crack at it here. You did all right.”

He said, “Okay.”

I said, “I'll relieve you of the conn.”

I went over to the boatswain mate and said, “Okay, Smith, you have the conn and take this ship alongside.”

He said, “What?”

You know normally, nobody but an officer, and a line officer at that, will conn the ship.

I said, “Take this ship alongside.”

We were going to take off the mail or something.

He said, “You mean that, Captain?”

I said, “I just gave you an order, sailor. Get on with it.”

“Aye, aye sir.”I said, “Turn course so-and-so and do so-and-so. You have the conn.”

That kid came through beautifully. He really had learned an awful lot just watching these things time after time. He came in, and there is a certain element of luck in these sort of things. He lucked out, and came in and made a very nice approach and came alongside and got the mail. He turned away, and I resumed the conn. I turned it back over to the officer and had him take it alongside the next ship. You have never seen anybody quite as proud and happy as that enlisted man. The word really got around about this kid.

Well, I ran out of time for the destroyer command. The tour then was two years maximum. So I called up the Bureau of Personnel. I wanted to go either to sea again, or to get duty on shore in Europe. I had done some preliminary checking and had been promised some job in Yugoslavia as an attaché or something like that. I had orders for an officer to relieve me. I still hadn't had mine. I called up and said, “Hey, where are my orders to Yugoslavia, or where-ever-the-hell it was?” I spoke Russian and so forth, and that qualified me for this job.

They said, “Well, we just reorganized over there, and there are no longer any slots left.”

There was a classmate of mine who was the detail officer up there. He said, “How would you like to go to COMSERVPAC?”

I thought he said COMSERVLANT which was in Norfolk. I had been there for four years and I said, “Aahhhh.”

He said, “What's the matter, don't you like Hawaii?”

I said, “Well, that's better than Norfolk.”

So, I went out as a plans officer for COMSERVPAC in 1956 and was there until 1960. I served under two admirals there, Admiral Solomons first, and then Admiral Campbell who relieved him. Both were very fine officers. As plans officer, I had direct access to the admiral which I used very frequently. I have always been in some ways a boat rocker. I wasn't a boat rocker in the usual connotation. I am lazy and I hate to see things done the hard way. So I usually come up with some new ideas about doing something. I had done that when I was working at the Naval Experiment station. I revised the course in thermodynamics and the text book and a few other things when I was teaching at the Naval Academy. When I was on the MEADE in World War II, I completely revised the ship's organization, battle bills, emergency bills and so forth. Within two years, this had become a standard for the whole fleet. This went on and on. I revised our Naval gunfire doctrine and our nuclear support doctrine. I did this mostly because I am lazy. I hate to do things the hard way.

I got to SERVPAC, and I found some things that I thought needed improving. I proposed a number of changes, many of which were approved. I helped to develop the major war strategy and then subsequently the logistics support doctrine for that strategy. Out of that the detailed requirements were developed for a completely new series of logistic support ships of which the Navy now has thirty or forty.

The first one, SACRAMENTO, which was a combat logistics support ship, was the first one to get to sea in support of carrier task forces off Vietnam, and it got glowing reports. The characteristics of that ship are exactly as I and two other officers wrote them

up. These were two supply corps officers. We sold our boss at SERVPAC on it. We sold the CINCPAC Fleet, and CINCLANT Fleet, and subsequently sold CNO on the work of this project. Since then we have spent several billion dollars building these new ships which are now in service.