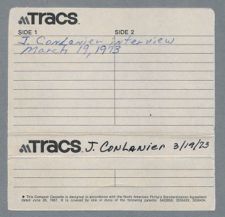

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW # 9 | |

| J. Con Lanier | |

| March 19, 1973 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| [Interview by Donald R. Lennon] |

J. Con Lanier:

I dont know. I'll do it. I have had all the publicity I will ever want. But, Ill go ahead. Where do you want me to start?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, if you will start with just your early background and go from there.

J. Con Lanier:

I am a native of Greenville and graduated from high school here. I graduated from the university. I took up law at Georgetown University and was a practicing lawyer. I also got into the farming business. They appointed me a tobacco specialist to go to Washington and help them form this program. We had no guidepost to start with. We started from scratch. We finally got one drawn up, and it has lasted until now.

Ive covered part of it, but during the Second World War, of course, our foreign markets were closed to tobacco. We usually sold one-third of our tobacco, more or less, abroad. Those markets were shut right down. Through land-lease we loaned them, England especially, money to buy tobacco. They have never paid us back and never will. When the war was over and the Armistice was signed, we had nearly a billion pounds of flue-cured tobacco in the storage which is about with the stabilization, and practically no foreign markets. So we began to think of ways that we could get these markets that we had had before the war back. We had a man go to General Lucian Clay who was then head man in Germany after the Armistice was signed. We wanted to get tobacco

included in the Marshall Plan which gave them money to buy food and clothing. They were putting the final touches to that act. The Agriculture Committee with Harold Cooley as presiding chairman was meeting in one room. They were right in this building in another room with locked doors. It was apparent that unless we got our goods inserted in the bill, we wouldnt sell any tobacco. So, he wrote in there, and he could get in because he was chairman of this committee. So, he went over, and we got it in the bill, and it was passed. That was it. Lucian Clay didnt interpret it that way. He said, “You are not going to get a damn cent for tobacco.” He said that the money had been appropriated for food and clothing.

Then we went to the people in Washington, D.C. Dr. Fitzgerald was handling the money. He and I and Jack Hutson met for lunch over there in one of the clubs. He took the position at first that if you give a man either a pipe full of tobacco or a chew of tobacco after a days work, he will work better and produce more. He finally agreed to this. We argued to and fro for two or three hours. He finally agreed that he would allocate some money first to Germany.

So, with that hold from him, we went to Germany and had them send over a delegation to buy tobacco. We had exhibition of it in a warehouse in Wilson with the samples of tobacco. From that they picked out some tobacco and bought it. They have been buying tobacco ever since then. They started off with two or three million on the first sales, and now we sell sixty million pounds a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it during this period that you made a tour of Europe and visited some eight different countries?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. That was made to implement this. While on this tour, we went to each of these countries. We went to France, Germany, Japan, Uruguay, Italy, and more and paid

the expenses of a delegation to come over here and look things over and buy some tobacco. We paid the expenses of this with some help from the government, and the burley people, and flue-cured organization also had a hand in it. We all got together and put it in enough money to pay the expenses of this delegation. It really worked except in France. Those sons of bitches wanted us to give them some more. The head man in France told us quite bluntly that they were not going to buy anymore of our tobacco. He said they would use what we gave them, but they wouldnt buy any. And they havent. But they only bought very little tobacco. What they get now, they get through smuggling through Switzerland. But from that little start, we have now recovered around approximately all of the markets we had for tobacco. Most of this tobacco is flue-cured which is what were interested in. Frank Snodgrass was the representative, the Executive Secretary of the burley people, and he also went with us.

We also then went to Poland. This was the first Americans to be admitted in there. We set up a cigarette making machine in which you would drop the tobacco in here and it would come out as packaged cigarettes. This was a mechanical thing. This was along the same line as manufacturing automobiles. The government was furnishing them tobacco, and we furnished them machines. We gave those cigarettes away. They are still buying some tobacco now.

One or two years later, we went to Spain and talked it over with the Spanish. Later on they went to this big fair. They have these big fairs and certain countries have their products there and they display them. We went and put up a cigarette making machine in Spain, and made millions of cigarettes and gave them away to get them smoking cigarettes. We had some luck there. They still buy some tobacco. We are also getting paid for this with some money we gave them I suppose, but anyhow we are

getting it. If we hadnt done that, by the time they had recovered, they would have found other markets to buy tobacco, which can be grown in other countries. This tobacco may not be as good as our tobacco, but it is a substitute.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, at the end of World War II when we were not marketing tobacco in these countries, were they just doing without, or were they buying it elsewhere?

J. Con Lanier:

They were doing without mostly. Of course, they had no money to buy tobacco. The only way they could get any was for us to give it to them. Tobacco was just stacked up over here. Except for England, which were special customers.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didnt know whether they were buying some of their tobacco from Turkey or somewhere like that.

J. Con Lanier:

Well, they cant make a cigarette out of just pure Turkish. But, during the war, they couldnt get tobacco from Turkey or anywhere. They were in dire need for some tobacco. We arranged for them to come back into the market, and anyone was going to buy would have to pay for it. If we had to cut our tobacco down a third on account of this foreign business, we would be in a terrible fix.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right. Well, you said that you set up cigarette factories in Poland and Spain. Was this a normal approach that you used in visiting these countries in opening them to tobacco trade? How did you go about opening the tobacco trade to these countries?

J. Con Lanier:

Normally, the tobacco dealers went around and sold the tobacco to them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right. Well, I know that you commented one time earlier that you had visited most countries at one time or another and tried to open and develop a market.

J. Con Lanier:

Well, at the end of the World War, in 1945 Mr. Hutchison and I went to all the countries practically in Europe telling them the procedure to follow to get some money from the U.S. to buy tobacco. Then they followed that, and we began selling them

tobacco. Take Japan, which was our chief enemy then. We sent a delegation of two men over there right after the war. Now they are our third largest customer in the world. They buy our very best tobacco. They also sell us tobacco today. We kind of swap.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do they grow tobacco in Japan?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. They grow a lot of tobacco in Japan.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didnt realize they had sufficient space.

J. Con Lanier:

They plant it really close together. They normally dont plant enough, and it doesnt make a good cigarette by itself. They have to have ours for the flavor to go with it. But, they do grow a lot of tobacco, and sell a lot of tobacco.

Donald R. Lennon:

In 1933, when you went to Washington, you were classified as a tobacco expert already at that time. When and how did you first become involved in tobacco that led you to be termed as a tobacco expert at that early age?

J. Con Lanier:

Well, I was raised right under the shadow of a warehouse. My county is the largest tobacco county in the world. You naturally get involved in tobacco if you remain around here. I will tell you how it happened. The East Carolina Warehouse Association had an annual meeting in Greenville. They invited me to make a welcoming speech. I was mayor at the time. I went down and made the speech. They all were broke then. Tobacco was then selling for seven cents a pound. I told them the shortcomings, and it seemed that the more pounds they produced the more money they lost. Then, after the speech I left. I went downtown and didnt even stay for their lunch, but I had lunch downtown. I went later to a baseball game. We had a league at that time. While I was gone, Bill Fenner who was an official in the Association got up and said, “Why that young man knows more about tobacco and my business than I do. We ought to have someone in Washington to look after our interest, someone who knows our business.” So

they appointed a delegation and finally said, “Well, will you go to Washington with us?” I told them that I would go with them. So we went up to Washington and talked around and found out that there were three men in the tobacco section. I came home and thought it over and decided not to go. I went down and saw Lindsay Warren, my Congressman, and told him I couldnt take the job. For some reasons which I wont go into, he changed my mind. So I went back to Washington and they put me on. I was fourth man in the department.

A year later they elected me administrator of the Code of Fair Competition among the warehouses. I was administrator of all the warehouses in this country. That ran for a year, and then the Supreme Court said that it was all unconstitutional. So they busted that up, and I went back to practicing law again. It happened that the tobacco association, the Imperial and Export were running the whole show. These little dealers like Ficklen Tobacco Company, and Greenville Tobacco Company didnt have much to say. They got tired of this, and they organized their own tobacco association. I was planning to run for Congress. They called me over to Rocky Mount and told me that they wanted me to form their association. I asked them how long they would give me to make up my mind. They told me I had one day. I said, “All right, I will give you an answer tomorrow.” I went back home and thought it over. I decided that there was a future to it, so I went back the next day and told them I would take the job. So they elected me Executive Secretary and General Council. We started to form an association. It is still running. I worked with them for twenty-five years. Then I got tired and old, and I resigned.

Donald R. Lennon:

You werent involved in tobacco back in the 1920s when the Tri-State Tobacco Cooperative was operating were you?

J. Con Lanier:

No. I was working tobacco on a farm, but I was not in favor of that association, and I didnt join. I didnt put any tobacco in it.

Donald R. Lennon:

It only lasted two or three years, and you dont hear a great deal about it. I was wondering who was active in it, or who really pushed it.

J. Con Lanier:

It was only active for two years. A Dago from California was the chief man. There were a lot of farm leaders thought it would get better prices for tobacco. I didnt, and it did not get better prices. Most of the farmers who put their tobacco in it, lost ninety percent of it. Finally, they got a petition from a Judge Meekins to put it in bankruptcy which he did. That killed that. I had no active part in it. I just sold my tobacco in the regular tobacco market.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were opposed to the Flanagan Tobacco Grading Bill of 1935. Could you tell us something about this bill and what the implications were?

J. Con Lanier:

Before the Flanagan Bill the government did not grade any tobacco. They just put it out there and sold it. The Flanagan Bill put government graders on all the markets that wanted them. The tobacco had to bring what the grade of tobacco was averaging, or the government took it in. I was against that. I was wrong on that, because they still grade it now; and they couldnt have this stabilization unless they had the Flanagan Bill. At that time, I thought it was wrong. I thought I should have the privilege to sell like I wanted to. They would put a pile of tobacco out on the floor, and the government man would come by and grade it, for example, B4L. Well lets say the average for B4L was twenty cents. The buyers would come along, and it either had to bring twenty cents or the government would take it. They would put this in storage. Thats how they accumulated so much tobacco.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, did the farmers get paid the twenty cents if the government took it?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. They got paid twenty cents for the tobacco. Of course he kept title to it. It was in the form of a loan, but when they foreclosed it, they agreed.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that that earlier tobacco bill which was the 1933 Tobacco Program was declared unconstitutional.

J. Con Lanier:

All that NRA was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is not just the tobacco program but the entire NRA Program?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. It was in the Forties. When the war broke out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Speaking of World War II, tobacco had a major labor problem during the war, did they not?

J. Con Lanier:

Not too much.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking that perhaps as a result in demands of the war upon all the men being sent overseas that there would be quite a shortage in farm hands and marketing personnel.

J. Con Lanier:

There was a shortage, but we werent raising as much as we are now, and the women and children did a lot of the work. They usually had enough to get by. The wage then was fifty to seventy-five cents an hour.

Donald R. Lennon:

I remember when we were paying that to work in the fields. I worked for that pay myself and it wasnt during World War II. It has been in more recent times.

J. Con Lanier:

I would give you some of the names of the ones that carried the ball in Congress for tobacco. There were some men from the other states that I cant think of their names. I just cut out their names, and it sounds like Im favoring North Carolina. These names of several men all are from North Carolina. But, there were some from Georgia, South Carolina, and many helpful men from Virginia. I feel like this is not fair to name just a few from around this state and not the other because they were very helpful.

Donald R. Lennon:

I understand that at one time there was an experiment up in the mountains of western North Carolina to grow flue-cured tobacco. Do you know anything about that?

J. Con Lanier:

No. I never did understand why you cant or dont grow burley down here and why they dont grow flue-cured up there. I dont know why it is like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the experiment wasnt successful but I have not been able to determine why.

J. Con Lanier:

They grew some Turkish tobacco up in western Carolina. They tried that for two years, and it didnt pay either. Turkish has got the flavor. We import over two hundred million pounds of good Turkish tobacco to go in our cigarettes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine most of our pipe tobacco has quite a bit of Turkish.

J. Con Lanier:

About seven or eight percent of it goes into the cigarettes. Every cigarette that you smoke has this. All the cigarettes, unless it is pure flue-cured cigarettes, has burley tobacco. In England, they wont allow them to mix burley with the flue-cured tobacco. There has been a law against it for over a hundred years. They can use Turkish tobacco and flue-cured tobacco in their cigarettes, but they cant use burley.

Donald R. Lennon:

On the Turkish tobacco experiment where exactly was that located here in North Carolina?

J. Con Lanier:

I dont really remember. It was on a home that was originally owned by a Mr. Garrett. I dont remember exactly where it was located.

Donald R. Lennon:

In 1951, you appeared before the Senate Finance Committee in opposition to an increase in the excise on cigarettes tax. Is there anything in particular that you would like to bring out about that?

J. Con Lanier:

No. Except this. Twenty-three dealers and handlers and buyers of tobacco signed a paper asking me to appear before the Senate Committee in opposition of this tax. The

Treasury was trying to raise this tax from seven cents a pack to ten cents. Every penny raised in excise tax would produce two hundred million in revenue for the government. So there was six hundred million dollars involved in tax that they were trying to put before the House Ways and Means Committee. So, four or five of us testified before House Ways and Means Committee. They then cut it down to eight cents. This was a one cent raise. We agreed to this. You know you sometimes have to compromise. The Treasurer went before the Senate Finance Committee. It had to go there after it left the House. They spent a week with charts and figures and all this trying to get it raised back to ten cents.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was their reasoning behind this? Why did they think that such a heavy tax should be put on cigarettes?

J. Con Lanier:

They just said that they could stand it, and they needed the money.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was supporting that? Was the Truman administration behind it?

J. Con Lanier:

I dont remember if Truman was behind it or not. I dont remember who introduced the bill. But anyhow, it went over to the Senate Committee, and they allowanced the Treasurer a week. They said that they would allow forty minutes to fight it. For some reason they picked me to do the fighting. I went to Senator George. George was interested in this somewhat. I knew him well. I told them that I couldnt do anything in forty minutes to answer that and that I may as well not go. He said, “Mr. Con Lanier, dont worry, I keep the clock.” I stayed on for one hour and forty minutes, and the bill came out at eight cents. I figured that I was instrumental in saving tobacco owners a tax of ten cents which amount in this country, with a ten cent excise tax on tobacco, would have been two dollars a pound. With the eight cents we now have, it amounts to about one dollar and sixty-five cents.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had some contact with Ezra Taft Benson during the Eisenhower administration, who was Secretary of Agriculture. What were your impressions of him? What was his position on tobacco?

J. Con Lanier:

He was dead set against it. I believe he would have liked to have outlawed all of it. He was a Mormon. Every chance he got, he would try to put more tax on tobacco. Tobacco was the only farm product in this country except the wheat, barley and such that goes in liquor that carries any tax. The government gets three times as much tax on a pound of tobacco as a farmer gets to raise it. Of course, we would fight it every chance we would get.

Then, the American Cancer Society which is the great biggest racket in America today, if you would go into it, you would find out, they are fighting it everyday in the newspaper. They spent twelve million dollars a year ago in advertising against tobacco. They did not use this money to find a cure for cancer, but to put it on tobacco. Then, they failed miserably to prove it, but they are still trying. They want to kill tobacco. They are still trying to put more tax on tobacco. Tobacco is the third largest exported product. I think cotton and automobiles and then tobacco come in that order. We also get cash for the tobacco that is exported. That helps balance our trade.

Donald R. Lennon:

In 1956, they were advocating a twenty percent cut in tobacco acreage. You made a speech in February of 1956 and supported a twelve percent cut. Who was demanding twenty percent and just what was behind it?

J. Con Lanier:

I dont remember right now just who it was, but I remember they had a meeting in Rocky Mount. The Congressmen came down there. Thats Harold Cooleys home. They had a hearing down there and got some of the big growers. I opposed the twenty percent cut. They didnt make it. They did cut it ten percent. We had a surplus of

tobacco. We had a billion pounds of tobacco at one time stored in the stabilization program. I cant tell you how many harvests that is. A harvest of tobacco weighs almost a thousand pounds.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of our members of Congress that you have known who did you consider to be the best friend to tobacco, Cooley?

J. Con Lanier:

Well, Cooley was worth more to us than anybody else. I would say that his influence was sometimes awesome. He had the reins of the Agriculture Committee. When it came to one of those bills, he would just put the thing under the blotter there and let it go. The two Congressmen that were most influential in helping us get through the legislation were Vinson from Kentucky first and Lindsay Warren second. There was a Senator who was a Republican from Kentucky, but I forgot his name. Those were the three that helped the most. Vinson was the most forward in helping us. If it hadnt been for him and Mr. Warren, we never would have gotten the bill through in the first place. They were the ones who carried the burden in Congress. The Carnegie Institute was fighting the American Cancer Society on this tobacco thing. They were very helpful in opposing the figures that the American Cancer Society had come out with. You know these are highly technical things that I dont know anything about. I would say that they are very helpful. They have put in a figure, I think of twenty million dollars. This is free. They did this to fight this cancer scare. They just donated this to the organization to refute the lies that the American Cancer society had put out. donation of thirty million dollars a year too. They did not have any check on how to spend it. The salaries were not checked, and what they did with the money was not checked. I had to stay in New York, so I wrote them and asked them to send me the list of the salaries that they paid their organization. I told them what I wanted. I wrote them on the Tobacco

Administration stationary. What they sent me was a blank sheet of paper. It did not even have their name printed on it. I couldnt tell if it was theirs. It listed some salaries, $25,000, $30,000, etc. In Tennessee the legislature there passed a law that no outside organization could collect money in Tennessee unless they filed an annual statement as to what they did with the money. Do you know what the American Cancer Society did rather than do that? They incorporated in the state of Tennessee. I still havent got the figures yet. You can get them either. I could imagine a beautiful home in every state I know of. They spent this money on plush quarters, and limousines, etc.

(End of side one)I was second lieutenant in an infantry line outfit, regular army. I went to training camp and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. We went through the mill. Thirty days after we landed in France, we were in the front lines. We got ten rounds of ammunition per man. I had never seen a live grenade and neither had anyone else in our outfit. Here were regulars in the regular Army in the Seventh Division, Thirty-fourth Infantry. This was in the woods up there at the Argonne Forest. On the edge of the Argonne, there was a ridge there. They had that forty-five entrenched in a concrete trench, as far as I could see over on that side of the ridge. We over on this side of the ridge in dugouts. We found it to be our job to attack and capture that ridge. Well, we captured it. We went through a three hour barrage. After we capture the hill, they shot at us from three sides. They hit every ten square feet on the damn hill. I have a shrapnel ball that hit my forty-five automatic here on my hip and went half through it. It hit the steel part of my forty-five. It knocked me down, but didnt scratch me. The other boys who were out putting up some barbed wire and were less fortunate. The next morning we got a counter attack. This was all in the darkness at night, and you couldnt see anything.

I got separated from my platoon which had gone back to take the wounded back. I was over here and the concrete dugout was over here, and the other fellows were over here. There was no one over there on that side but me. I didnt know this. Here came a detail of Germans down a path just like that. When I saw them, they were about six feet away. I picked up a rifle. Im a pretty good shot with a rifle. I killed three of them right there. They couldnt see me. They thought I was in that trench and I was out of it behind a log. There were four unused bullets in this rifle. One of the boys had been hurt and left there. I only had four cartridges of anything. The others went back, and I got with my boys and we held our position. I got a Silver Star for gallantry in action. That represented gallantry in action. I got recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross when I got out of the Army. I havent heard anything from that. I really didnt give a damn anyhow.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you said that you had no hand grenades at all?

J. Con Lanier:

At first when we went there we didnt; but after we captured the hill, we had some that the Germans had left. They had a little hand grenade about the size of an egg. You could throw it, and they really were terrible. They fell around me like corn thrown at chickens. But they never hit me, in fact I never got a scratch. I went to Germany in the Army of Occupation. I stayed up there three or four months in the Military Police. There was a town half way between Colbitz and Mainz. It was a little town called Dietenhofen. All American AWOLs took that town over. The French were afraid to attack this town. Their general got in touch with our division commander, and they asked that he send some Americans up there. So they picked my company out of the whole division and sent us to this town. We were there to pick up the AWOLs. I stayed there three months I reckon. It was a very nice place. We got a hotel room, and we got the boys beds in the

barracks. We put the other crowd back in horse stables and using anything they could get.

We had to cut this thick barbed wire which at its smallest is about as big as your little finger. We had to clip this while going up that hill with the damn Germans shooting down on us. They found out we were attacking them early on morning. I could have reached up, I think, and grabbed a whole handful of bullets the way they were going over my head just like that. As we got up there, we switched around and went down the frank and we just really were reaming them.

Donald R. Lennon:

We frequently hear and see reference to the use of airplanes for observation purposes during that time. Were they of much use to ground troops?

J. Con Lanier:

Not a bit. I only saw one American plane where we were. The Germans went over us with planes that were called Richthofens circus, and they passed over us in the form of a crescent. The Americans went up, and soon they ran back. We didnt bother with them. Of course, they couldnt see us. We were in places underground. We were dug in a hole. In the woods, fighting like Indians was quite a fashion, I will tell you that right now. It was hide and shoot. You know they had built this concrete trench all the way across France. Right where we attacked it was the end of it. They had a small steam engine and a tram road that ran concrete right up there to build it on through when we got there.

Donald R. Lennon:

It hadnt been destroyed by the fighting?

J. Con Lanier:

No, you couldnt destroy that unless you had some very heavy artillery. What it was was a ditch dug four feet deep and about that wide with concrete on both sides of it. It was death trap to me. I wouldnt get in it. If you were in there and they knew where you were, all they had to do was to send a grenade in there; and you would be gone.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no protection at all?

J. Con Lanier:

None at all. Except in about every two hundred yards, they built a concrete dugout there which was impervious to anything except artillery. I was out in those woods putting up the barbed wire, and as I say, they hit every ten feet square on that hill. One big one came over, and it hit the ground about twenty feet from me. It had been raining and it was wet all around me. It slithered off and went BOOM down the hill. If the thing had exploded where it was supposed to, there wouldnt be a piece of me left.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said you only had ten rounds of ammunition did you not? That must have given you an uneasy feeling when you were first out there.

J. Con Lanier:

Thats when we first let out there. Each man had a clip of five and five in his rifle. If they attacked us, they could have won tremendously. We got some fooled and made the attack.

Donald R. Lennon:

Thats what I was thinking, that had you been attacked while you only had ten rounds, you wouldnt have been very pleasant.

J. Con Lanier:

It would have been too bad. They were third class German troops that we ran into. They told us. For instance, we captured a group of them from behind a tree that had been shot down who were hollering, “Comrade, Comrade.” We didnt shoot them. I shook hands with one fellow. He looked so much like a butcher in my home town, that I thought it was him. We sent them back after capturing them and they were happy; but they gave us hell with their artillery.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you come back from Germany, in 1919?

J. Con Lanier:

I came home in August of 1919. We were scheduled to go back on a troop ship. We were quartered down there in France. We were packed up and marched right down to the railhead to get on the train and go back to Germany. Then we got orders telling us

to go to Le Mans to come home. So we turned around and went back to this village. Then we went down to Le Mans and from there we went to a town near the Atlantic, but I cant recall the name now. But anyhow, it was in the same town we landed in. We went to another lieutenant and I decided to go down and see the town. So we went down and walked around. We went over to an old place in a rock that they said was a prison, but dropped down to the ocean, and they dropped the prisoners in there. We came back and went to a bar and I wanted a beer. A lieutenant who had been in my outfit asked me, “What are you doing here? Your outfit is getting on the boat for American now.” This was Sunday morning. This little town was about two or three miles from the camp. He said, “Yes. Theyre getting on the boat.” I dropped that glass of beer and set out for the camp. I got there and everything was gone. My clothing and everything was gone. One of the other officers had packed it up for me. So I ran back and got down there to the water front as the last damn boat was going out to that ship. I got on it. My friend and I got on it. Boy, that was close.

The turning point of the whole program, I think, it was the greatest part of it. If we hadnt got that, in the meantime, the other countries would have increased their tobacco; and while it was not as good as ours, it was tobacco all right. I think southern Rhodesia grows a lot of tobacco, Germany grows some, Japan grows a lot, and Canada grows a lot. They grow it all around, but we can outgrow them. But it came down that if we couldnt sell the tobacco, and the other countries could get this tobacco, they would. They would keep right on taking this kind of tobacco if they got used to it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Its probably cheaper than that we would use to sell them, was it not?

J. Con Lanier:

Right, it was cheaper than ours.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, we taught a few of those countries how to grow tobacco, did we not?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. We taught them how to grow it, just like a fool.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know one gentleman that was in China teaching the Chinese how to grow tobacco in the interior. From what he says, they grow a type of tobacco there that was very similar to our type of tobacco. He was in China between World War I and 1935.

J. Con Lanier:

Right, China grows a lot of tobacco, and were at one time our second largest customer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think there will be potential in the future for tobacco trade with China as a market again?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. Were about to get where we can sell them some now. We are also making headway with selling to Russia too. Russia was also a very good market for our tobacco. I went to every country in Europe except Russia, and in the Far East except China and India. I never went to those three. I went to the Philippines and Japan.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this trip in the Philippines an attempt in opening the market and encouragement to them to buy more tobacco?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. We went there to tell them what to do to get our tobacco. We would give them a guide of how to go through the channels.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were primarily using American money to buy this tobacco with?

J. Con Lanier:

Thats right. We got a couple of Japanese men to come in. One could speak English, and one of them could not speak a word of English. One of them was a teetotaler, and the other one drank violently. He couldnt get enough. They came down, and I took them around to all the markets in eastern North Carolina. I took them over to the town of Rocky Mount. I took them over to the factories over there. I took them to three or four of these other dealers. One of the negro men there who had been a solider and had been captured by the Japanese recognized one of these fellows. It was all they

could do to keep him from going on this Japanese. I really dont blame him. They were nice though, but they are somewhat foolish people; but I like them better than any group in Europe.

Talking about these big fairs, every five years, I believe, they had me in Madrid. Madrid thats where we put the other machinery for making cigarettes. There were 700,000 people that came into that fair ground the first day it opened. Everybody in Madrid went to the fair. Madrid had two or three million people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Back until just recent times, most of you tobacco companies and warehouse and processing companies were, many of them particularly in this part of the state, were independent or semi-independent, were they not? I notice today most of them are subsidiaries of the larger companies.

J. Con Lanier:

None of the warehouses are.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking more in particular the processing companies.

J. Con Lanier:

I dont know, but Reynolds, American, Liggett have their own buyers today in the auction sales that are held in the warehouses. The independent companies like the Greenville Tobacco Company, the Ficklen Tobacco Company, Wilson Tobacco Company and Tryon-American Tobacco Company are independent tobacco companies.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now Ficklen is now part of Carolina Leaf, isnt it?

J. Con Lanier:

That is right.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is what I was referring to.

J. Con Lanier:

Debrow Brothers has most of their subsidiaries around. Universal Leaf has more subsidiaries than anyone else.

Donald R. Lennon:

Lets see, the old Person & Garrett Firm is now at part of the Universal Leaf, is it not?

J. Con Lanier:

Well, they were for a long time, but have gone out of business now. That Universal is a money crowd.

Donald R. Lennon:

Back in the early days, here in Greenville, I have seen references to what they called Tobacco Row as being the major warehouse area. Exactly where was that? This was the center for selling tobacco. What part of town was this in?

J. Con Lanier:

That was over the whole town. Some of it was on the river and some on the south side. Warehouses are great big structures. Wilson is the largest market, and they have ten to twelve warehouses; and they are independent of each other. If I have a warehouse and you have a warehouse, and well try to get the farmer to sell in our warehouse for the commission we get and you will too.twelve warehouses there. One of them is the largest warehouse in the world. It has twelve acres of floor space.

Donald R. Lennon:

How do our modern warehouses today vary from the early ones, the earliest ones that you can remember, other than the size of them?

J. Con Lanier:

They operate practically the same way. Right now, they are going to try a new system over in Rocky Mount. I saw that in the paper. But ever since I worked in one, and I worked in one when I was ten years old, the farmer would bring the tobacco and put it on the floor. The buyer would come by and buy it if they liked it. It goes on row after row right on down.

Donald R. Lennon:

So basically, they use the same system even today?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes sir. We had a lot of trouble two to three years ago with lossage of tobacco weight. They would weigh it and put it on the warehouse floor. The ticket on it would say, for example, 100 pounds. When the man bought it, and took it to the factory and weighed it there, it didnt weigh but ninety-four pounds there. That got to be a regular scandal. We finally worked out a system and broke it up. In one way to steal it, the

driver of the truck had a box built under his seat; and on the trip from the warehouse to the factory where he took the tobacco, he would get at handful and put it in his box. Who knows how much he did steal. But at least, they finally caught him. Over in Kentucky, the way they did it there was that the companies bought it and put it on the trucks and carried it to the factories. On his truck, he would drive along that Broadway Street there, and the street would be littered with tobacco. They picked these fellows to be cahoots with them I reckon. But, they would reach over and slap ten to twenty pounds down on this road. Then the kids would run up and pick it up and take it back to the house. Finally, the companies started taking deductions from their pay for the lost tobacco. The warehouse told them that if they didnt get it they would really have a long hassle. I took Mr. Lipscomb, the American man, down there one day and showed him where his tobacco went. There it was laying on the main street. They finally broke that up.

Donald R. Lennon:

When tobacco is sold in the market, just what processing does it go through in its initial stages before it is packed into the hogshead?

J. Con Lanier:

Just in the past two years, the farmer doesnt tie it in bundles; but it is now sold loose leaf. They just had to be tied. Otherwise, it was discounted when it was sold.

Donald R. Lennon:

Doesnt this cause some problems in grading?

J. Con Lanier:

No. The tobacco companies use it all in their cigarettes, the good and the bad. They also use the stems too. It was sold loose leaf in Georgia and Florida but elsewhere, they sold it entirely tied. You would grade it out on the farm. One barn of tobacco would have six or seven grades in it. You would sit in a pack house all fall and grade the tobacco. You would put your green leaves here, and then there would have the good leaves there, and over here, they would have the burnt leaves, and the sandlugs. At least, that was the way it was sold then, but if got to where there was no use of it. When

you pull the tobacco off of the stalk, you take it to the barn, tie it on a stick and put it in the barn and cure it. Thats one time that you put it on a stick. Then they take it down and take it to the pack house and leave it there until they can get to grade it. Well, after doing that, they put it on a stick again and take it to the warehouse. When they get to the warehouse, they take it off the stick again. When it is sold, the buyer will take it to the factory and put it on a stick again. They run it through the drying machine, and they take it off the stick at the end of the drying machine and put it in the hogshead. Its just on and off and on and off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Im familiar with the old time tobacco barns; but these new bulk curers that you see so much now, how do they operate?

J. Con Lanier:

I dont knowI dont use them. If you fix your tobacco farm with these new barns and new housing machines, it will cost you forty thousand dollars to get all the equipment. This is just to harvest tobacco. If a man has fifty acres of tobacco or a hundred, he may be able to use this. I cant, and ninety percent of the farmers cant afford to use this.

Donald R. Lennon:

Dont you see this as probably one of the major problems facing the small or medium size tobacco farmer today, the fact that the big producers can afford this expensive picking equipment and curing equipment and everything else that most farmers cant afford.

J. Con Lanier:

Absolutely, this is putting the little farmers out of business every year. Its hard now to get tenants. I happen to be lucky enough with mine. You dont never know when they are all going to quit. They all seem to die when they move to my farm. Some of them stay there for thirty-five years. But on the big farm that farm now, just one family has been there for twenty some odd years. All of them have died except for one boy

twenty four years old, and hes running the farm now. He is liable to move any year or so. Then I dont know or what the hell I would do.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, the early drying system that they used back in the old days, did they use a steam dryer?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. They changed from tying tobacco to selling untied tobacco because now they have threshing machines. If you had a bundle of tobacco, you would have to untie it and throw it in. The way they buy it now, they just dump the whole damn thing in the threshing machines, and it comes out with the stem just as clean as a whistle. It is all torn up in pieces, and they go right ahead and use it in their cigarettes. This is a very economical way of doing this. Then, they take the stems and wet them and roll them into sheets, and they look just like brown paper. They put these into their cigarettes.

Donald R. Lennon:

About the only thing that hasnt changed then is the warehouse procedure, is it not, over the years?

J. Con Lanier:

Thats right. That hasnt changed. If a man comes back after six years of being away, he would know exactly what to do. They sell it the same, they pay off the same. The warehouses own commission is the same in North Carolina. They get ten and a half percent of what it brings, ten cents for the auction fees up to a hundred pounds, and twenty five cents about a hundred pounds and ten cents for weighing. Thats the law in North Carolina.

There was another episode at one of the warehouses. We were figuring on this warehouse code of fair competition. The department sent a bunch of Jews down in the growing areas to look things over, and see if it fits. They went out and mistook barns for warehouses. A barn is usually sixteen by eighteen or twenty. A warehouse usually covers ten or more acres. The code had a license of fifty dollars on each warehouse.

They went back and reported this unfavorably saying that fifty dollars was too much to pay for each one. They were talking about the barns. I said, “Good God almighty!”

Donald R. Lennon:

Im sure they had no conception at all of what tobacco growing was all about did they?

J. Con Lanier:

Not a bit. None of them ever sweated a drop in a tobacco field. Mr. Jerome Frank was the chief lawyer over in the Department of Agriculture. He didnt know a pig from a cow. He got so bad that Chester Davis, who was above him, fired him. I was out in Kentucky then, and it came out in the paper that Chester Davis had fired Jerome Frank. I sent Chester Davis a telegram saying, “Congratulations on the purge.” President Roosevelt wanted him to become a circuit judge up in New York. This Jerome Frank died two or three years afterwards. He was a great big fellow. He was an arrogant son-of-a-bitch if there ever was one.

Its Lee Pressman who managed Wallaces campaign and John Abt, Morteca Ezekiel and, oh yes, Alger Hiss. I went around when I first got up there, and they invited me around to one of thems home where they were living. They had all kind of things. We got to talking, and they had three steps they said they wanted to take. They wanted to take the profit out of business. Then they wanted to take over and run the business. Third, the government would have the business. That is step by step that this damn young twenty year old hand in mind for this government.

Donald R. Lennon:

They wanted to socialize everything?

J. Con Lanier:

Yes. They wanted to take the profit out of business. Men have to turn over everything to the government and then the government will have it. I said, “You cant do that. It would mean youd have to change the whole system.” They said, “Well, lets change the system.” My Lord, those dumb bastards.

Alger Hiss was number two in that delegation. Roosevelts telephone number was number one and his was number two. He was a slick artist.

[End of Interview]