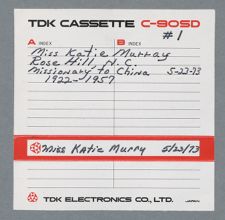

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #8 | |

| Miss Katie Murray | |

| Missionary to China 1922-1957 | |

| May 23, l973 |

Katie Murray:

In 1922, I went to China. I had one year in Peking Language School. It was a wonderful privilege to be in Peking, that old, old city with so many interesting places to visit like the Great Wall and the Emperor's Palace and the Altar of Heaven and all of these things. Of course, we studied five days a week and on Saturday we had the opportunity to see Peking.

The next year I was stationed in Cheng Chow, which is a city about halfway between Peking and Hankow. In Cheng Chow, there was another year of language school but with just one teacher and one pupil. This wasn't as attractive as Peking where there had been lots of different nationalities and students from different areas as well as capable teachers. Then after two years, when language examinations were over, I went out to do my work and discovered I didn't know a thing. The women spoke a different dialect from the one I had learned in the book, so that meant I really had to get to work. But I enjoyed it and tried to pick up their dialect and idioms and so on. It was a pleasure to tell the gospel until I went to my next place of labor in South China and the Communists came. Of my two years there in Kweilin, eleven months were under the Communists. That was from 1948-1950.

My next term of service was in Taiwan, which is known as the Republic of China. In 1949 President Chiang and about a million or two of the mainlanders fled from the mainland of China to Taiwan. I was in Taiwan from 1954 to 1959.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you first arrived in China in 1922, describe how you felt and the life you saw around you that was so different from the United States.

Katie Murray:

I remember very well when I was on the boat and we were nearing the port of Shanghai, I looked out and saw all of these Chinese and I said, "Well, which are the men and which are the women?" I couldn't tell the women from the men because the uneducated women wore pants and the educated men wore a long garment. So I couldn't figure out how things went. To see the men pulling the rickshaws and heavy carts was very strange. Of course in the station just about everything was backwards.

Donald R. Lennon:

How do you mean?

Katie Murray:

Well, in the Bible you start at the back and read toward the front and instead of reading across, you read up and down. In that day, instead of shaking the other person's hand, you shook your own hand. One of the three Methodist men was in our compound one day, and I stuck out my hand to speak to him just like I did at home, and he drew his hand back and shook his own hand. Well, I got the point that I wasn't to shake a man's hand. Those were some of the things that were different. To see the people worshiping idols--that was one of the most heart rending things I saw at first. I saw that first in Peking and I haven't forgotten it. To think of a man made in the image of God falling down before something man had made to worship did something to my heart; it made me want everyone to know the true and living God.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were the idols?

Katie Murray:

The idols would depend on the wealth of the family. It might be a paper stuck up in the living room, where it had a central place. The ancestor worship would be something made of stone--just the names written there, "This is the abode of such and such an ancestor." They worshiped that ancestor primarily during holidays.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the people you were dealing with primarily ancestor worshipers?

Katie Murray:

Yes. All of the Chinese worshiped ancestors. That is one reason the Communists wanted to destroy the idea of worshiping God. They would go to graves and tear them up and tear down things, trying to make these people forget their ancestors. They didn't believe in any God, and they didn't want you worshiping any ancestors or respecting them. Of course, they had their fire gods and gate gods who guarded you as you came into the house. There was a kitchen god, which was just a paper. In the temples there were the great tall Buddhas, made of wood I suppose, and painted over with what looked like gold. I'm sure it wasn't real gold. There were many, many different kinds of gods. You would see trees that were worshiped. I also heard that they had monkey gods--every kind of god that you could imagine.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you think of the people?

Katie Murray:

I loved the people; I think they are wonderful people. I think about how they were able to read and write when our ancestors were roaming as tribe people in Europe. Their civilization is much older. For instance their students really studied, and they put us to shame.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of Chinese customs did you observe?

Katie Murray:

Their marriage customs were different. In some areas they marry very early. In the area where I was--and I want to put that in about everything I say because China is a

very large place and the customs of the different areas vary--they would sometimes make an engagement for their babies; they had middle men to do that. Of course that went out long ago, but it had been a custom. Another custom was bound feet. They followed the fashion of the wife of the emperor long ago, and that was just the style. The "Bible Woman" who was my chaperon had had bound feet, but when she became a Christian she unbound her feet. But her feet never grew to normal size. Single girls had to have a chaperon when they went out. This elderly woman went with me--she served to tell the gospel as well as be my chaperon. We didn't call her a chaperon, but I knew the point.

Donald R. Lennon:

While you were there, there was a move to do away with the binding of women's feet, wasn't there?

Katie Murray:

Yes. That had been going on for many years before I got there, but you would still find out of the way places where they hadn't heeded the law.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was a law?

Katie Murray:

Oh yes. There was a law that they observed, especially girls that went to school. But there were so many girls who didn't go to school. The younger ones didn't have bound feet, but you would see the older ladies with them. The people in South China would say that they never saw any bound feet because they didn't do it there, but in the north they did in many places.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was polygamy practiced in the area you were in?

Katie Murray:

Yes. A man could have as many wives as he could afford. One time, I went to visit a family in which our pastor had said the man had four wives. The man was dead then, but we visited the women. I've heard the Chinese preachers say, "Well, what's the

difference? The Americans just marry them and then divorce." Of course they don't believe in either one, but they were saying what was the difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you notice any problems developing over this?

Katie Murray:

Yes. The people would say, "Well, in the Bible the men had many wives." And one of our women would say, "Well, look at the trouble they had too, and look at the trouble you have in China." Of course we had that problem in our church. I remember we had one man who had been to Bible school, and he did not have any children. His mother wanted grandchildren, and she thought she must have a grandson. So she kept insisting that he take another wife. Finally, he yielded; I don't remember if he was taken off the church roll or not, but I know we didn't count him as a leader any longer.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you deal with people who wanted to join the church and already had several wives?

Katie Murray:

In one case I recall, when the man converted, he saw he was wrong and said he would take his wife back to her home. And that's what he did. In other instances the churches let them stay on. Some of the Baptist churches kept them on and some didn't.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was some degree of popularity for vegetarian diets as opposed to eating meat, wasn't there?

Katie Murray:

Yes. I used to visit the wife of the postmaster who was a fine Christian, and his mother was a vegetarian. She would eat no meat. These vegetarians believed that if you caught a fish, you must let him go back into the water; you must let him live. You couldn't eat any animals; it was not right to kill them. But this woman was converted and she realized that it wasn't by not eating meat that her sins were forgiven, but that it was

through Jesus Christ. She became an ardent Christian--a vegetarian who turned to the Lord.

Donald R. Lennon:

Would there be any problem with a person being a Christian and still being a vegetarian?

Katie Murray:

No. I don't think there would be any problem. It was a matter of religion for them not to eat meat. They felt they were laying up merits. But then they saw that Jesus Christ died for us and we didn't need to depend on merits for salvation.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had a central base city out of which you worked?

Katie Murray:

Yes. We worked in five counties, and we found that the most successful way to work was to have an evangelistic group of workers--missionaries and Chinese--go into the churches for Bible study. That was really divided in two. There was one who did the preaching and the meetings and another one who did the Bible study. Then we had another group go to un-reached areas. We had those groups when we were at our height. The missionaries decreased because of the wars and all of the troubles and trials that came, and sometimes we didn't have that many groups to get around. But that was the best way we found.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have a special compound?

Katie Murray:

Yes. In that compound there was a hospital, a school, and residences for the missionaries and a number of Chinese. They were made of brick. In our area, it would have cost I don't know how much to build a frame house because lumber was scarce. You didn't see trees there like you do here. The land was under cultivation. They didn't even have all of the hedgerows like we have around here. As I drive around here and see

our fields I think, "Look at all of those hedgerows; how much crop they could grow there."

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the compound belong to the denomination?

Katie Murray:

Yes. The compound belonged to the Southern Baptist Foreign Missions Board. Now we are doing it a little differently. They have houses scattered separately over the cities and not all together. But at that time we had a school, a hospital, missionary residences, and Chinese worker residences.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did there seem to be any resentment toward the Church for separating itself off into a compound rather than being part of the town?

Katie Murray:

I don't know whether there was or not. Bu the missions don't do it that way now; I think they just found it was better to be scattered about. Of course as communism grew, there was an anti-foreign feeling.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you experience this? Was there any overt animosity?

Katie Murray:

I remember one boy who confessed his sins, and one of them was, "I hate that British imperialist." They would confess that they hated us too because we were foreigners. As communism grew, underneath was working this matter of hatred toward people--toward Americans. Of course when the Communists came they blurted out all over the towns: "Hate the Americans! Down with the imperialists!" As it grew, it didn't come out that openly, but it would come out in their confessions. When people confessed their sins, they might come to you and say, "Forgive me for hating you."

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you see any of this before the Communists came in?

Katie Murray:

No. But there was a fear--the idea of "They're foreigners." It's just like here. If a lot of foreigners come in, we are curious about why they are here and what they are going

to do. There was that feeling I think. But they welcomed us. I have heard missionaries of earlier days tell how they had such difficulties in getting into homes or anything. But we would go along the street and they would call out, "Come in, come in." This was in my day, however when the Herrings and Lawtons were there, it was not that way. They were called the "foreign devils." Of course, I've been called a foreign devil too, but it wasn't a general thing; the fear had broken down. They realized that the missionaries were there to help.

Donald R. Lennon:

How far away were the out stations?

Katie Murray:

We went west and we had Tsinyang, Szeshui, and Kungshien on the railway. As to the length of time it would take to get there, that would vary; sometimes you would sit half a day on the railway waiting for a train to come. I remember once we waited and waited and finally went back and decided to get some carts and mules and go that way instead of waiting for the train. In wartime, trains were delayed, and it finally got to the place that the only way to travel was by cart. They learned to make a light little cart with rubber tire wheels, and one man could pull it. You could fix it up and have almost a Pullman. You had to take your bedding along anyway so you could just spread it out; we called it a Pullman.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you travel as much this way as by train?

Katie Murray:

In the latter years we did. But before that the trains were running regularly and we had good service. Cheng Chow was a railway center; we had a railway north, south, east, and west. So it was very convenient. Of course, we had some stations in the mountains where you had about an all-day trip on a donkey. That was for thirty miles.

But it would take about all day on the back of a donkey, going up and down mountains. You would start early in the morning and get there late in the afternoon.

Donald R. Lennon:

How frequently did you visit the stations?

Katie Murray:

That depended. Our plan was to have a summer class for the women, and we would have a spring and a fall meeting. Sometimes I was in a group that got to these, but somebody was supposed to go to these places.

Donald R. Lennon:

Then they didn't have services year round?

Katie Murray:

Yes. There was a preacher there, and in addition they had little out stations for missions from their churches.

I want to tell you about Mihsien during the war. We were there during a raid. We had come there for a meeting from one of their out stations for what we called a big church meeting. We had just been in there a few minutes when the siren sounded. This was the first time a plane had visited this town so the people ran out and I thought, What should I do? I decided to get back against the wall, because somebody had told me that if I were ever in a house during a raid to get next to the wall. So I just moved my seat to the back against the wall. In a moment or two, the bomb had struck the roof of the church and when the clouds had passed away from the dust and everything, there lay one of the deacons wounded terribly bad. A girl was sitting next to me with her arm wounded and others were just dying. About six or seven died from that raid.

The funny part about it was the magistrate came to help us out, and, in a day or two, he sent a messenger asking for me to come to his office. He said, “Now, the people are seeing that you were the spy."

Of course, it was a real joke to think that I would be such a dumb spy to let them bomb the place where I was, but that was the rumor going around. He said, “Well, I think you ought to go back to Cheng Chow." So I did. The man who escorted me to the boundary of that county really laughed about my being called a spy.

Donald R. Lennon:

But this was a serious rumor?

Katie Murray:

Yes. It was circulated that I was a spy. You see, I was a foreigner; they had never had a raid before, and someone had seen a foreigner come in just before that raid. So I was the one. I had already been there for several days before I was sent home, and I had had the wonderful privilege of seeing the people meet outside under a tree on the following Sunday. I was sent home on a Monday. I had worked among the bereaved people for several days and had met with them on Sunday under a tree out by the side of a river, outside of the city walls. To see those bandaged people standing there praising the Lord really touched my heart. They were thanking and praising him, and they decided to have a meeting right away and that they were going to rebuild the church.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were not the ones who were spreading the rumors.

Katie Murray:

No. It was not the Christians; it was just someone--I don't know who. But you see how that might be too; I understand how it might be. It was a real joy to see their courage and their faith under trial.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you arrived it was in the midst of the warlord period; did this continue for some years while you were there?

Katie Murray:

Yes. It did. The warlord period was different as far as foreigners were concerned because the fighting was different. I mean there were not many killed; they just fled. If one army was up against another, they didn't really get into heavy clashes--there were a

few wounded sometimes, but they didn't really do much fighting. We often said that the only thing they did was run when it got close. There were not many people killed, and there was not much devastation. Sometimes as far as our work was concerned with soldiers passing through a town, they might use the church to billet the soldiers, and it might be just when you were planning a meeting. The only thing to do was to let them use it, pray for them, and do whatever you could.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you recall any particular incidents involving the warlords?

Katie Murray:

Well, nothing special I don't think. They didn't make such an impression on me. Of course I realized they were taxing the people to feed their army; that was one thing that was bad. But these soldiers had to be supported. In that time the soldiers really didn't have much training, they didn't know how to fight, and they didn't really look like soldiers.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did they have in the way of arms?

Katie Murray:

They didn't have anything much. I don't know what they had. They had a gun strung on their backs. I can see them going along now with those big guns on their backs. They were like the guns people here hunt with--that's what it looked like, anyway. There was only one warlord who dominated a particular area until someone else came along to push him out. The Japanese did that. All this time there were two forces eyeing China--the Japanese who were just across the way and whose ancestors they say are Chinese. But there had been a great rivalry and ill feeling between the two nations for many, many years because the Japanese were progressive people; they had a small country that was easily ruled; they were literate and progressive. China was such a big, rambling place with many dialects, many different customs and difficult to rule.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any hostility during the warlord period toward foreigners?

Katie Murray:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

Earlier, you mentioned the different types of foreigners who were there in addition to the missionaries.

Katie Murray:

Yes. There were British businessmen who lived in our compound. Then there were the oil people--American Standard Oil--who were Americans. There were Frenchmen with the railway, and there were Italian Catholic missionaries.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have many dealings with the businessmen?

Katie Murray:

Not much. We had a Sunday afternoon service, and they were invited to that. Some of them would come--some of the American Standard Oil people and some of the English.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any tobacconists?

Katie Murray:

No. Not in our town. In some areas there were.

Donald R. Lennon:

You know there were quite a few North Carolinians over there involved in tobacco.

Katie Murray:

Yes. I have met some of them here, but I never met any of them over there. We got acquainted with the Italian Catholic missionaries during the refugee period doing relief work.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the Japanese invasion?

Katie Murray:

Well, that was during 1937 in the north. Our first raid in Cheng Chow was on February 14, 1938; I remember it because it was Valentine's Day. We said that we really got a valentine. There were seventeen planes, and they hit twenty-five spots. They killed quite a number of people and wounded many others. I was sitting in the living room with

my co-worker, Grace Stribling, and two Chinese co-workers; we were planning meetings at the out stations. We heard the planes coming and in a moment bombs were falling. We saw people running around. Some fell on our compound, but there were no bad injuries. One patient at the hospital got a little cut I believe, and windows were shattered and so on. But that was an experience for me because I hadn't known how I would do or feel in a raid. I can't explain the peace and joy that was in my heart unless it was the Lord that put it there. In the morning I had read in my devotions Psalm 63:7, "Under the shadow of His wings will I rejoice." When Miss Stribling and I had our worship together, again we read that psalm and again I was impressed. When that bomb came, I don't know--there was just a peace and a joy in my heart.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you expecting trouble?

Katie Murray:

There had been many threats that it was coming, but it hadn't come and hadn't come so we had no idea it was coming that morning. I thought, "Well, somebody's praying," and pretty soon after I had written home about the raid, I received a letter from my mother. She said that she had read the letter to a friend and this friend said, "Well, I have been praying for Katie that she might be kept under the shadow of His wings." So it was just really wonderful to me to see how there was someone praying that I would be kept under the shadow of His wings and that on that very morning I was directed to read that passage and had especially noticed it and experienced the joy of being under His protective wings.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that the warlords had just continued to seesaw back and forth with their own private encounters until the Japanese invaded and swept them away. Is that correct?

Katie Murray:

Yes. Then of course there came President Chiang who was a strong man by this time. He was really a wonderful president and ruler, and he had done so much to do away with the opium traffic--he really did a wonderful thing in that. He was very severe in his punishment; if you were caught with it, you were killed. I remember being in a chapel one day, and I heard a great commotion on the street. I said, "What's going on?" Everyone rushed to the door to look, and there was a crowd following a man who was being taken to be executed. We asked what he had done and were told that he had been trafficking in opium. So they were just taking him out to execute him. Chiang's rule was that if a person was an addict to give him a chance to be treated, but if he were a dealer he was to be put to death. In that way it was put out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the opium traffic a problem while you were there?

Katie Murray:

Yes. I didn't know anything about the traffickers, but I knew about the people bound by the use of opium. Our teacher, an old Confucius scholar, had been on opium for no telling how many years.

Donald R. Lennon:

The opium dens were still in operation?

Katie Murray:

In our area, I don't know that there were dens, but there were individuals who would get opium and take it. During the revival, there was a mighty turning to God in that period--beginning about 1932--and there were many opium smokers who put their trust in the Lord.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the Japanese air strikes a recurring problem?

Katie Murray:

For a little while it let up, then it would start again, and we learned to have dugouts right by the root of a tree. We first had trenches. Dr. Ayers had been in the war so he knew that was the way it was done then. They were covered over with just a slight

covering of branches and about an inch of dirt--not enough dirt to smother you but enough to keep out the shrapnel. Then we found that a better way was to dig a hole right by a tree, and if a bomb hit, it would likely hit the top of the tree. That happened with our pastor; he was right in a hole at the root of a tree, and a bomb hit the tree branches and he was spared.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the compound damaged by bombs?

Katie Murray:

Yes. The Fielder's house was a bit shaken up but not too much, and they somehow missed our house. Of course we had American flags out, but they didn't seem to do too much good.

Donald R. Lennon:

That may have been more an incentive for them.

Katie Murray:

But I don't think the Japanese wanted us as an enemy right then.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the attitude of the Japanese to the Americans and Chinese?

Katie Murray:

Well, when the Japanese first came in--they came in on a Saturday, and the young women gathered in our house because they had heard about the danger to women. So they came into our house, and we were expecting right then to hear the signal that they had surrendered. Soon the signal came--the blast--and the people said that it meant surrender. My "Bible Women," whom I spoke about earlier, just burst out crying. The women stayed in our house for a number of days. Sunday came and we decided we would have two services--one in our house for the young people, and the older people would go to the church as usual. My co-worker, Miss Stribling, guarded the back fence because the Japanese were just across from us in a school, and they had the reputation of jumping fences. Miss Stribling had had experience with them at Kaifeng; she had been up there to help them when the invasion came there. She was at the back guarding, and I

was in the front guarding. Pretty soon a Japanese soldier jumped over the fence, and there was Miss Stribling. When he saw her, he just bowed and said, "American, American." He didn't know what to do.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that you were guarding the fence; what had you planned to do?

Katie Murray:

Well, just be there; that was all we could do. I saw another one get in on my side. I couldn't speak Japanese and he couldn't speak English, but he pointed that he wanted to go in the house opposite me, which was a missionary residence. The Fielders were gone, but I didn't want him to go in; I didn't see any use in it so I just pointed right straight ahead to the gate. I just kept pointing to the gate, and he followed on to the gate and when he got there, he opened it and went out. I was shaking in my boots.

In those days we were called in to take the Chinese out to get their goods. We had our school full of refugees and our house full. You see they respected the Americans, and if they saw an American, they wouldn't beat up the Chinese. So if anyone had to go to his home to pick up some clothes or food, they would come and ask, "Please go with me." One time the pastor came and said, "I want you to go with me to the church. There are some Japanese down there in the basement, and I want you along." They felt that if an American were present, they wouldn't harm them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they make a practice of harming the Chinese without provocation?

Katie Murray:

Yes. They would just beat them. They couldn't talk to them and if they wanted them to do something, the best way was to just beat them up. Those were the days when the Lord's grace was sufficient. You pretended to be brave, but you were shaking in your boots.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Japanese attempt to reduce the influence of the mission?

Katie Murray:

No. They didn't bother that at all. They didn't bother us in anyway. The only time we realized we were in danger from the Japanese was after Pearl Harbor. They stayed in our town for one month and then went away across the Yellow River, which was just fifteen miles north of us. Our Chinese friends who had been in service said that we could get out then or we could get out later with the retreating soldiers because they knew that the Japanese could come any time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was China able to offer any more than a token resistance to the Japanese in your area?

Katie Murray:

That was about all--a token resistance. And they could come back any time they wanted to. The Japanese didn't want to use up their men in guarding something they could have any time they wanted. We chose to stay on and had about three years of wonderful opportunities.

There was famine, too. No food would get in except what was pulled by carts. The railroads were cut, and there was no rain in some areas. Because the railways were cut, grain couldn't be transported so men would pull the grain on those little rubber-tired carts. But it was an awful thing to see.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this an agricultural area?

Katie Murray:

Yes. It was but there was a lack of rain. I never realized before how dependent we were on the Lord for rain for our food.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was food imported into China or was it brought from other areas?

Katie Murray:

Some of it was brought from other areas, and the difficulty was in getting it to us with the Japanese occupying all around us. We were just a little island there. You could

go west on the train as far as Sian in the neighboring province. But the area east of Kaifeng had been captured early, and we could go only about fifteen miles that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Japanese try to prevent food from being brought in?

Katie Murray:

No. You could slip it by somehow, and also people could sometimes get through. They would let you by sometimes, but it was very difficult to go all that round-about way to get anything. It was just very difficult; that was the problem.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened in 1941?

Katie Murray:

The famine grew worse and worse; people were eating bark off the trees. They would take the bark from the trees, dry it in the sun and then grind it up and eat it. In the spring, when you could eat the leaves off the trees, they did that. Of course, we did all of the relief work that was possible. As the war came, there were refugees from the north, and they also came from the south from the area of the breaking of the Yellow River dikes. The fighting in the north had been going on longer.

I remember once there were about two thousand refugees who came into Cheng Chow and just lay in the streets. Dr. Ayers went out with the Chinese pastor and brought them to the church. Of course they couldn't take but a few hundred in the church. The government tried to set up camps for them, and the Christians set up camps. They had funds from the International Relief Committee and the Red Cross. That's when we worked together with the Catholics. They had a rule that you must have a representative from every mission. We had Lutherans, Free Methodists, Episcopalians, Catholics, and Baptists. We worked together on that relief camp. The camp was financed by outside funds--the International Red Cross, the International Relief Committee--but it was

implemented by the missions. They often wanted missions to have the money to see that it got to the right place.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the refugees expect you to provide for them?

Katie Murray:

They were just glad for anyone who could do for them. It was very pathetic; you would see wealthy people from Peking who just had nothing. I remember one old lady, Mrs. Wong. You could tell she was from a well-to-do family, but she was lost; she didn't know where her people were; she was crippled, and it was just pathetic. Sometimes there would be a child, and you didn't know where in the world the parents or any members of their family were. Also, there came a cholera epidemic--trouble upon trouble. Of course they tried to treat them in our hospital. When the going got worse and there were more raids, Dr. Ayers moved the hospital out to the edge of the county. They would come in late in the evenings when they thought the planes wouldn't come.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have the physical facilities to handle very many, did you?

Katie Murray:

No. But Dr. Ayers was a man of initiative, and he put up mat sheds. We don't have them over here, but they have great big mats about six by four or something like that. You can take them out and make a mat shed. He put up a lot of those, but of course that was just a drop in the bucket. The government also tried to take care of the people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there a government functioning at this time?

Katie Murray:

Yes. You had a magistrate; it was primarily local government. You see the state capital was taken over by the Japanese. Also the military people in charge tried to do everything they could.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened after December 7, 1941?

Katie Murray:

When we heard about that [the bombing of Pearl Harbor]--Mr.Ashgraft (?sp) of the Free Methodist Mission came over to tell us. We thought, "What are we going to do?" The Japanese were fifteen miles from us, and they could come anytime they wanted to. Some missionaries left, but we decided to stay on and work as long as we could, and then get out when we could; that's what we did.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you see any change in the attitude of the Japanese soldiers?

Katie Murray:

They had gone, but if they had been there we would have been taken prisoner. You see they were with us only one month, and then they retreated. There wasn't any use in keeping their men there, holding a city they could occupy anytime they wanted to. It was just a ghost town by that time--the stores were gone, the town was filled with refugees, and it was a terrible looking place. I tell you war is an awful thing. As far as our church membership was concerned, it had just cleared out long ago. The people fled north, south, anywhere they could. Some fled to Shanghai and when they got there, there were raids and bombings so some of them came back. But there were so many refugees; there were more than we could take into the church services.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was more of a refugee operation than an organized church?

Katie Murray:

That's right. But a lot of them found the Lord, and sometimes people who were already Christians would come in too. I remember when the people left, we said that we didn't have any Sunday school teachers or anything, but others came in. People were saved, and we had wonderful opportunities. The suffering and troubles made ready hearts to receive the gospel. Maybe they had been trusting in their wealth and riches, and suddenly it was all gone. Or maybe some were cripple or their people were lost and there was such suffering that their hearts were open to the gospel.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long was it before the Japanese came back?

Katie Murray:

They came back in April, 1944.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you continued to function?

Katie Murray:

Yes. Until the morning they got in. We still went to our out stations and into our churches. Some of the people at the out stations had not left. Cheng Chow was the city that got the bombing because that was where the railway was and other things that they wanted to get hold of. So some of the other places were not as severely damaged, and the people were not as scattered. So we still continued our meetings and Bible classes in every way that we could with the workers we had. I believe it was early in the morning of April 18, 1944, I had been to the morning prayer meeting at the church and while coming back home I met a man who said, "The Japanese are here." I thought, "What are we going to do?" So immediately we began packing up to get out. He said that he had seen some Japanese, but it had just been the advance one or two. So we got off that day, and we walked about two weeks in the mountains trying to find a place where we thought it would be safe to stop and work. But every time we came to a little town, the magistrate would say, "Go on; the Japanese are coming."

Donald R. Lennon:

So you didn't even try to head for a port?

Katie Murray:

No, you couldn't get to a port then. The only way you could go was west. So we walked about two weeks and finally got to the railway. We found a train and got to Sian. From Sian we got a bus to Chungking. By that time I thought we had found a place to work, but the board said that I was already overdue for a furlough and that I should go home.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were able to communicate with the board?

Katie Murray:

Yes. You see that was free territory in the west. The capital later moved to Chungking, and people from all over China were fleeing to Chungking. In that party there was an Australian friend, Dr. Strother, who had arrived just ten days before the Japanese came. He stayed on and worked there. The board said for me to come home. So I came home by way of India. I flew out of Chungking on an army transport to India. I had to wait there for transportation for I don't know how long, and I finally got an army transport out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is there anything that particularly sticks in your mind about your wanderings in the mountains?

Katie Murray:

Yes. I traveled with about six hundred of the refugee school children and their faculty. For the first of the first few days, Dr. Strother said that we were just doing pastoral visiting because we were staying in the homes of Christians. As I said, there were about five of us in this little party--my Australian friend, Dr. Strother, me, our cook who carried our baggage, and a school boy. Then we got up with the six hundred students and their faculty. The principal would send word ahead that there were so many coming and to please get food ready for us. So when we would get to a place, he would have a place for us to stay and spend the night and there would be food prepared.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were traveling on foot?

Katie Murray:

Yes. That's right, and the little baggage that we had was gradually discarded except the little things that our cook could carry on his shoulder.

Donald R. Lennon:

How was the weather?

Katie Murray:

It was spring weather, and it was nice. But there would be planes going over, and I remember seeing a dead horse. We were with the retreating army, too, and I remember

once in a while meeting up with a soldier struggling along. It was just like they had told us three years earlier--we could leave then or wait and go with the retreating army. So we waited and went out with them. One thing I remember especially was the shoes that I was wearing. I had had them for a number of years; in fact, they were given to me by a friend, so they were second hand to begin with. The sole just got to flopping, and I thought that if we had time to stop I could get a Chinese woman to make me a pair of shoes because they made cloth shoes. But there wasn't any time; the Japanese would catch up with us. So Miss Dado(?), the Australian friend who had a great faith said, "I'm asking the Lord to give you a pair of shoes; He knows our need. The Heavenly Father knoweth what things you have need of." And my need was a pair of shoes. I thought, "Where will I find any shoes on these mountain roads?" One day we stopped at a restaurant, and while we were eating our soup she said to the restaurant manager, "Do you have any shoes here?" I wondered why she would ask for shoes in a food shop. The man said, "Yes. I have one pair." He brought them out, and they just fit me. So our Heavenly Father not only knew my need, but just the size of my foot.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there restaurants operating?

Katie Murray:

Yes. In the mountains there were. But it was just a little food shop, not a big restaurant like you are thinking of. You see, the Japanese hadn't gotten up in the mountains. On that trip one night we were spending the night in the home of a Christian, and we were staying in a room just next to the daughter-in-law. I heard her just crying in the night. I asked her, "What is it; what's the trouble?" She said, "The Japanese are just ten lea from here." That's three and one third miles. So we got up in the middle of the night and started off again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have the six hundred students with you at that time?

Katie Murray:

No. They had gone on, or were behind us--I don't know where they were. The principal lived near us, and when he started out, he said "We'll see you along the way." So we did. He had been a military man, and he knew how to send word ahead that so many people were coming and to have food ready for us. He had done that as an officer so he knew how to manage for this crowd. It was a great help too because when we got to a village, they would have arranged for a home for us to stay in. This was Mr. Lee; he was a wonderful Christian. He had gotten off in the south during his military training, but during the revival he just came back to the Lord with his whole heart. He became principal of this refugee school, and just witnessed for the Lord everyday.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that the Japanese were just three and one half miles behind you; they were not consciously trying to catch up with you, were they?

Katie Murray:

No. They were just moving in that direction. We had heard that the Japanese occupied the cities and not the little mountain areas so our hope had been that we could find somewhere and begin working.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think the Japanese would have bothered you if they had caught up with you?

Katie Murray:

Yes. We would have been under house arrest at least after Pearl Harbor because that is what happened to many of our missionaries. If they were in the territory when the Japanese came in, they were taken prisoner. We had many in Shanghai and other places, and at first they might just put you under house arrest and later something else.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't actually have to face any Japanese after Pearl Harbor, did you?

Katie Murray:

No. I didn't see any Japanese after Pearl Harbor; I kept out of the way. The goodness of the Lord let us walk fast enough to keep ahead of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

You took your leave in 1944. When did you return?

Katie Murray:

I came back here, and then in January of 1947 I went back. A number of missionaries went on an army vessel. I went back to the same town and was there one year.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were your impressions when you returned? Had the town been restored?

Katie Murray:

It hadn't been restored, but the thing that I marveled at was the growth in the Christians. I remember especially Mr. Jong, one of the preachers--how he had grown in faith. Some of them had been receiving at least some support from the mission, and now suddenly they had no support.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the mission operating when you returned?

Katie Murray:

Yes. What I meant was that the mission funds were gone; they couldn't get funds from America. You see some of these preachers had been supported by funds from America. Of course we tried to work on self-support, and some of them were.

Donald R. Lennon:

By 1947 the funds had not been restored?

Katie Murray:

No. I'm talking about how they had grown during that period when they did not have the funds and when they had all of these troubles. You see, they had the Japanese come against them all of those years until the war was over. Then, of course, we went back. Our premises had been occupied by the Japanese, and they had built in these little nitches, Japanese style, and changed things all about. They made changes in our homes; they had adapted them to the Japanese style of living while they stayed there.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you find?

Katie Murray:

I don't remember anything special except the growth of the Christians and how the trouble and sorrow had strengthened their faith.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Chinese situation had changed a great deal by that time with the withdrawal of the Japanese.

Katie Murray:

I think there was a great relaxed feeling that they were gone.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had the Communists come in?

Katie Murray:

Yes. You see the Communists had been working since at least 1922 when I came on the scene--really way before that, but I didn't know about it. But during those first years you would see White Russians, and these Russians had fled from Russia. Many of them would come through our city. At the same time, young Chinese students were going to Russia to imbibe communism. Here were the Russians fleeing from communism, and here were the Chinese students going to Russia and coming back with Communist ideas. So you see the two forces were going. As soon as Russia became communistic, they began reaching out. The idea of the course was Chinese translation, "all under heaven is public." One way was to send people over there to learn and then come back and spread it.

We were ignorant about communism. As missionaries we didn't know anything about it. Sometimes we would say that we didn't know which would be better for China--Japan or communism. We just didn't know, but we knew there were two forces seeking to get control. One of the first things that comes to mind as evidence were the strikes. Another one we later saw was disrespect for those in authority. The Communists really believe in authority when they are in power, but beforehand they use that to try to break down a country. According to the Confucius doctrine, young people have great respect

for their elders in the way they were taught and brought up. But in the schools you would see them shuffling their feet. That's a very minor thing compared to the things that are done today in our schools. But in most of their schools, you would find out after awhile that there were Communist cells in there, and they were working.

Another sign, as I see it now--of course I didn't see it then--was the way they were trying to put the Bible out of the schools. In a mission school, you couldn't even teach the Bible if you were considered a registered school. What we did in our mission, we said that if we couldn't teach the Bible we wouldn't have the school. So we opened up a Bible school. We didn't carry the regular school thing and it wasn't registered.

Another thing was that they were trying every way they could to promote atheism. And another one that I saw after the Communists got in was mass marriages. There they would have certain days when anyone could get married. They could just have a mass ceremony; it was much cheaper; God was not recognized or anything. I was surprised at that. Another thing was the morals going down. I remember in South China there was a wonderful opportunity among students. One of my co-workers, Millie Lovegen, whose specialty was students, would go to the university, and sometimes the girls would invite her to spend the night. Well, she found that the boys would come right in the rooms, just like they do right here today. It just distresses me, and of course she was just shocked to death. But I think it was just decaying morals, and so many things that you can see now that were happening there as communism came in.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were the strikes directed against?

Katie Murray:

I think it didn't matter what it was against, just so they were tearing up things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any that you remember particularly?

Katie Murray:

The railway strike was the one I was thinking about, but that was something so different for China. That disrespect for authority and elders was so different, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did this involve violence?

Katie Murray:

No. Passive; they were not violent like they are here. Americans are much more violent; they were not, but you could recognize the same thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have any problem with your own Christians at the mission going along with the Communists?

Katie Murray:

Before the Communists came, you can look back and see some things that were inspired by them, I think. For instance, they wanted to take over the hospital. Also, one time when we elected deacons, it was surprising and distressing to see how they manipulated trying to be a deacon.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who wanted to take over the hospital?

Katie Murray:

The Chinese doctors. They knew what was going on better than we did, and they knew that it was our property and they wanted to get in on it. I figured when we were going to elect deacons that was the same thing. I was very distressed about it, but still I didn't connect it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the mission--the hospital and everything--controlled and administered by Americans only?

Katie Murray:

It was in the name of the American Southern Baptist Mission. There were Chinese doctors and so on, but we didn't have a board at that time, I guess, because there weren't the right people to put on it. Of course in the church we had deacons, but we had not turned over property. I didn't think about it at that time, but looking back I realize

that they saw and probably had been told what was going to happen--that we would be run out and they might as well get in on the property.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think their idea was to prevent the Communists from getting control--that they could salvage it?

Katie Murray:

It might have been.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you have the overt overrunning by the Communists?

Katie Murray:

I left the day before they got in. I got to Cheng Chow in April of 1947, and I left the next year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you leave due to the Communists coming?

Katie Murray:

I realized they were coming. They said that the last train was pulling out before the Communists came in. There were three missionaries there then. Dr. Yokum decided to stay, but the three girls decided to go. Many of the Chinese there had fled from the Communists in the north into Cheng Chow to work there. The hospital had already moved to South China--Dr. Ayers had already moved.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were without a hospital.

Katie Murray:

Yes. Dr. Yokum remained, but most of the staff had gone south. We three ladies decided that we had seen and heard what had happened in North China, and the Chinese advised us to go where we could work. So we went on the day before the Communists got in. We got a truck and went to Kaifeng and then went from there by plane. It beat walking for two weeks. A Lutheran mission sent in a plane to get us. We flew from Kaifeng to Shanghai and from there to Kweilin. I was there about two years, and for eleven months of that I was under the Communists. It took them a little more than a year to move down. Of course, they had taken Shanghai before that.

The board asked us to go to Shanghai to discuss what we were going to do--whether we were to stay or leave. I was asked to go for our station. We didn't decide, and nobody knew what we were going to do or who was going to do what. As I was getting on the plane to come back, standing there waiting, the Lord seemed to say to me, "Would you stay?" I said, "Yes, Lord. If you want me to stay, I surely will." So that was settled for me. Then some others came in--another doctor and his wife--so five or six of us stayed there when the Communists came. I remember when the sound blasted the surrender, and the Communists were in control. It must have been a cannon or something like it. I remember Mrs. Harrison just fell to the floor; she thought it was an attack or something.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did they do when they came in?

Katie Murray:

They came in very orderly--not like they had been in the north. They had been very cruel in the north--plundering and all kinds of bad things. But here they were well disciplined and orderly. We tried to go on as we had been doing. Of course, there wasn't anybody in town; the people had fled. But that's the way it is when war comes; people flee to the country. In that change of government, people were very afraid. There was looting, plundering, and no telling what. It's bad when there is no government.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you able to continue to function under Communist rule?

Katie Murray:

Well, we were limited. Before they came, the attitude of the Chinese was, "You are very good." After we were under the Communists, the Americans were very bad. That's what we were supposed to be. Of course, in their hearts they felt toward us as they did before, but they were afraid.

I was going to the church one day, and some children were out playing; they called out, "Very good, very good," and held up their thumbs. That's what they had been saying before. There was an elderly many standing nearby, and he said, "Don't you see that policeman there on the corner?" In other words he was telling them that they were saying the wrong thing--to keep their mouths shut.

Our English class fell off; there wasn't anybody studying the English Bible on Sunday morning--maybe one or two at first, but that fell. But we kept on in our preaching missions. Our missionaries didn't go out into the out stations, because you had to get a permit if you went out anywhere. At night you might be inspected as to whom you had in your house. One night at midnight, a crowd of people sent by the Communists came in, and they wanted to go through the house. They were a group of young people; they looked like they were in their twenties. They came in and wanted to see the rooms and went through.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they hostile?

Katie Murray:

No. Someone just told them to do it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it harassment?

Katie Murray:

We didn't figure out exactly what it was unless it was just to see if we were harboring anybody in our house, or it might have been to see if we had a radio. I don't exactly know why they came. But one thing we were glad of was they didn't go into the pantry in the back. They looked in the bedrooms and kitchen and all around. But our treasurer had our money in the pantry. Dr. Cauthen had brought us gold nuggets of money. The Nationalist money was no good, so he had brought in gold nuggets that we could sell and have something on which the hospital could go and on which the work

could be carried on for a while. Millie had put that in a little box in the pantry, and we were so grateful when we passed by that pantry door and went on down the steps.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they begin to restrict your conducting services?

Katie Murray:

That continued. One time they had a service in our church, which I went to. A man--I don't know who he was--just got up and preached his doctrine of communism. But we went on; our pastor, Mr. Dean, was a graduate of Southern Seminary in Louisville. He was an excellent man. He had already figured that they might take our church so he had readied little buildings around to serve as chapels. It was my opportunity to go to one of these on certain nights. I was speaking one night in that chapel, and the Communist soldiers stood at the door and listened, but they never stepped inside.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they listening to find out if you were preaching something you shouldn't?

Katie Murray:

I imagine so, but I just went on preaching the gospel like I had always done. That night when I had finished and was talking to people, the soldier stepped inside and began to question me. He said, "Why do you favor the Nationalists?"

I said, "My business is not political; I'm here to tell the gospel."

Again he asked, "Why do you favor Chiang Kai-shek?"

I repeated again, "I'm not here politically; I'm here to tell the gospel."

That went over and over, and the people gathered around to see what this foreigner and the Communist soldier were saying. After awhile we quit, but of course my Chinese co-workers saw it. We went back and the pastor told me that I should not go back for a while. So I stopped going for a while. But then I went back again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you received any instructions from the mission board on how to avoid any commentary concerning the government?

Katie Murray:

No. The board just said for us to stay or come home as the Lord directed us and that they were behind us either way. That's about the only instructions they gave. They expected us to get our wisdom from the Lord. I felt he gave me some wisdom one time. I had to go to the dentist, and just outside this Chinese dentist's door stood a Communist soldier guard. They were just standing out all around and watching out for what was going on. When I came out of the dentist's office, he said to me, "What do you think of us?"

I said, "I think you are very well disciplined." That was the truth and it pleased him.

One time I was going down the street and saw a group of soldiers coming along, and they said, "Oh look; there's a Russian." But someone said I was an American. On another occasion they said the same thing and someone said, "Your courage is great--an American being around here."

Donald R. Lennon:

On the occasion when the Communist got up and conducted his own service, was this during one of your services?

Katie Murray:

No. I never knew how it was arranged, and I don't know who did it. He might have seen the deacons or someone, but I don't know whom he saw. They had arranged a meeting, and I just happened to go. It was a meeting at the church and people just went, I suppose. That was the first I knew about him. He just got up and talked about communism.

I want to tell you another little story. One of the Chinese pastors was having a meeting in a little chapel just after the Communists came in, and some new recruits came to stay in the same room in which he was living. They all just stayed in that same room that night. He talked to them and told them the gospel, and they were interested. Well, it wasn't long before an officer came in, and the pastor started telling him the gospel. The officer said he didn't want to hear it. He said, "I am god; Stalin is god." He had been indoctrinated you see, and the others were just raw recruits who had not been indoctrinated.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have any problem with your own people being indoctrinated?

Katie Murray:

Some of them were. I'll tell you about some of the students at the University of Kwangsi. A number of them believed and were really warm hearted and zealous and had a real experience with the Lord. One of the students was called Benjamin. We gave them foreign names so the Chinese wouldn't know who they were when our letters went through the censor. These boys really had a hard time because they hadn't had much background. Some of them were from Buddhists families and had been Christians just a short time. They told us they had to go to the indoctrination classes. They would get them in groups and indoctrinate them. The students decided not to say anything--to just keep their mouths shut--but they found that wouldn't do. They were told if they didn't say anything that meant they were against them. Some of them worried so much they got sick. So Benjamin came to our hospital. I was visiting there one day and saw him on the bed. He had his Bible, and he said, "I don't understand this. What does it mean?"

I asked him, "What do you mean?"

He said, "It says, 'Servants obey your masters.'" I knew what he meant. The Communists were saying there must be no classes and no servants. I didn't know what to say, but the Lord gave me this, I think.

I said, "You are sick and the doctor has ordered a soft diet, but the servants in the hospital say that it doesn't matter and they bring you a regular diet. What about that?"

He could easily see that the servants had better obey, at least in his case. But he was disturbed about the Bible. He felt that he didn't know whether this was just like any other book or what. He was just worried, and there wasn't any use in arguing. We wouldn't get anywhere telling him that this was the word of God and what he should do was to pray. Sometime later there was a knock on my door and there stood Benjamin with a broad smile on his face.

He said, "Did the Lord ever tell you where to read in the Bible?"

I said that I didn't remember that He had ever told me to read a certain passage.

He said, "Well, He did tell me. He said, 'Read Peter.' I didn't even know that there was a book in the Bible called Peter, but I looked and looked and found Peter. I read Second Peter 1:21 which says 'Prophesy came not in the old time by the will of man, but holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.'" He said, "The Lord showed me that the Bible is different and is the word of God."

He was just so happy, and then he was ready to help another friend whom we called James. James had been a leader in the church but he was influenced by the indoctrination. When he was lax in coming to teach his Sunday school class, I talked to him one day, and I found that he was doubting and didn't know what to believe. He was

being told that religion was an opiate and that missionaries were imperialists and warmongers and so on. He was distressed.

I said, "James, you know God and you know Christ, and you know what sin is."

He said, "Oh no; there's no sin." I knew that he had had a definite experience and had been convicted of a sin, but he was so befuddled that he just didn't know what to believe.

I said, "Why, you know lying, stealing, and hating and all that are sins."

He said, "No, that's not a sin."

You see he had taken in the doctrine that there is no sin, no God, no heaven, or no hell. All we could do for him was to pray. That was in the fall, and by Easter Sunday he was miserable. He decided to get his Communist books and read them for comfort. He did, but he didn't find any comfort. Then he decided to go to church and see if he could find some comfort. So he went to look for his friends, and they had already gone. When they came back from church Benjamin was among them. So James found Benjamin and he got on his knees and prayed to the Lord to forgive him for what he had done, and Benjamin was able to help him. Then he came with a shining face and told us what the Lord had done for him--how far he had gone and how the Lord had forgiven him. He didn't even stay to get his diploma that commencement; he just told someone to take it for him because he was out telling the gospel. He went from there to a seminary in Shanghai; Shanghai was more free from the bondage of communism because it was a port city. He went there for training, and then I heard that he worked for a church for a while. The last I heard he was in Siberia. I don't know where James is today.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he go on his own?

Katie Murray:

No. He was sent there. You know they would just send anybody--a doctor, preacher, or anybody--especially someone they wanted to get rid of as punishment. So I just trust that the Lord has taken care of him somehow.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did the change finally come--when your stay there came to an end?

Katie Murray:

It came to an end in 1950. I was there a little over two years. I had definitely decided that we should leave, but one of the other girls felt she wanted to stay on. Of course, we had to hang together because we didn't want to leave one of our missionaries there alone. So the three of us waited and prayed together. In my mind, however, I felt that the time had come when one of the faithful Chinese Christian women said, "Don't you think it's time to go?" I felt that if the Chinese saw that we wouldn't be any good to them and they couldn't help us, it was time to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you think you were accomplishing anything there for the last few months before you decided to go?

Katie Murray:

Well, I don't know. We couldn't go to the out stations; we couldn't visit in a home. Millie went to a home one day although she really knew that we shouldn't. In a short time there was a Communist there to see what an American was doing visiting a Chinese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the people afraid to have any dealings with you?

Katie Murray:

Yes. They tried to be nice, but we knew that we might involve them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they continue to come to the church?

Katie Murray:

Yes. People would come to the chapel too--unbelievers, too. When people are in trouble, they will come.

Donald R. Lennon:

But they didn't want the Americans coming to visit them?

Katie Murray:

No. They didn't want to get too close to us because they knew they would be accused.

Donald R. Lennon:

But you left voluntarily.

Katie Murray:

Yes. We had to apply for a permit a long time before we left. Soon after I got out, a Chinese friend told me that I had gotten out just in time. I didn't know what she meant, but pretty soon we heard about a missionary who had been killed in Wuchow.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have here a note on your visit to the mountain tribes.

Katie Murray:

I think we were four days on the road: we rode by bus for a few hours and then walked. This was in Kweilin in about 1948 or 1949. We found that a young tribesman had been saved and had gone back to tell the gospel. The way he found the Lord was that he decided to join the military and he went into Kweilin, the capital city, to enlist as a soldier. As he went along the street, he saw a sign that read, "For God so loved the world." So he went into the chapel and found out about the true God. They explained to him about the one true God and Jesus Christ, and he believed. So instead of going to join the army, he went back home to tell them about Jesus Christ and the one true God. He went to the temple and tore down the idols and pulled them out. That caused quite a commotion in the village, and he had to hide because they were going to punish him. He just hid out, and someone would take him food.

Some of the missionaries heard about him and they asked him if he wanted to come into Kweilin to study more about the gospel. He did. He entered Bible school there, and later he went back. When I visited, there were two churches there as a result of his labors and witness. The pitiful part though . . . Where was he? The Communists had come earlier and taken him captive, and he never returned.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any observations about the people or the life there?

Katie Murray:

It's a very difficult area as far as living is concerned. It's way high in the mountains. For vegetables they had ferns.

One day the deacon stuck his head in the door and said, "Do you like dog; could you eat dog for dinner?"

I said, "Yes."

So that day for dinner we had about four big dishes of dog. I looked out the window and tried to imagine it was beef.

Donald R. Lennon:

That wasn't during the famine was it?

Katie Murray:

No. This wasn't during famine times. I realized that the man had found a dog somewhere--maybe it was somebody's pet--but they were far away from any market to get any meat. I guess they considered dog good meat, so I enjoyed it as best I could.

Donald R. Lennon:

You commented that your diaries were hidden in a cave at one time.

Katie Murray:

Yes. During the war our Bible school went to the mountains due to the many raids, and we sent some of the thing that we wanted to keep. They were stored away in a cave. The Christians dug a hole in there and put in the things we wanted to keep. They were not found.

The work in Formosa was begun in 1949. Miss Bertha Smith and a Chinese pastor went over and began to work there after the Communists had taken over North China. There were many, many mainlanders there. There you had at least three different dialects: Mandarin, which the mainlanders speak; Taiwanese, which the people of Taiwan speak; and then there were the Hakka people. Our work was mostly with the

Mandarin. We later started to work among the Hakkas and now we work among the Taiwanese.

My feelings about the importance of working among the Taiwanese was brought to mind when I was speaking in Mandarin one day, and a little Taiwanese girl said, "Could a Taiwanese believe in Jesus?" She was Taiwanese, and here I was speaking in Mandarin to the Mandarin Chinese. But she had been to school, and everyone who went was supposed to know Mandarin and must learn it because it is the official language. But she wanted someone to talk in Taiwanese to her.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you learn any other dialect besides Mandarin?

Katie Murray:

No. One was all I could manage.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you deal much with refugees?

Katie Murray:

No. Not much. After these mainlanders got to Taiwan, they got busy and did something and were not refugees very long. Of course, some of them suffered from malnutrition like one of the girls from the mainland who came to our home. They had nothing, and they couldn't get the necessary food. But in a few years they were on their feet. The progress Taiwan has made is remarkable. You know they haven't had aid from America now in years; they are on their own, and they have factories and are making things. You know you see things with "Made in Taiwan." Economically they are doing well, and as for the gospel, they have been very responsive, too. I have heard now that as they are getting more affluent, they are getting more engrossed in material things and are not as interested in the gospel, which is sad to say, but it looks like it happens everywhere.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have a note here that you had some dealings with mountain people who were headhunters.

Katie Murray:

Yes. We didn't have any work with them, but there were tribes' people there who were headhunters. The Presbyterians had the largest work among them. They were there many, many years ago, and Canadian Presbyterians particularly had labored among that group.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is there anything else you can think of?

Katie Murray:

Nothing except one or two lessons I learned from these things. One is that it makes me very happy to pay my taxes now, because I know what its like when you don't have a government. I was there twice when no one was in charge--there was no authority. In the transition period, when the Chinese surrendered and the Japanese took over, there was a period when people were frightened; anything could have happened with no one in authority. That also occurred when the Communists took over in Kweilin when I was there. It was a bad time because we didn't know if there would be looting, killing, or most anything. So I think how good it is to have a government--someone in authority. So “pay your taxes gladly” is the way I feel.

Another thing is how people turn to God. I think that we in America should not wait until we have real trouble before we turn in humility to God.

[End of Interview]