| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

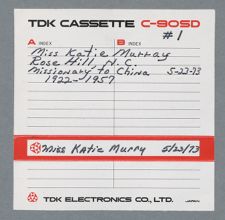

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #5 | |

| Miss Lorena Kelly | |

| May 18, 1972 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Would you like to begin Miss Kelly by telling about your arrival in Africa and the situation there?

Lorena Kelly:

Yes, I can even begin when I left the United States, which was in September of 1935. At that time the Congo was ruled by Belgium and we could serve better if we studied French. Of course, I had studied French in the country, but that's different from learning to speak it, so I went by way of Belgium and spent three and a half months studying French there and left in January of 1936 to continue my journey to the Congo. On February 26, 1936, I arrived at Wembo Nyama. Wembo Nyama is our oldest station. It is our largest station and it was where our work was founded. I was there for about three and a half months studying the Otetela language.

Maybe you would like to know what a station is like? All of our work at that time was in a rural area of Africa and I was working in what we call the Central Congo Conference. That conference is located right in the heart of Africa about equal distance from the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean and about three degrees south of the equator. In fact, I've seen the sun shine clean down in the fireplace as it came down the chimney, which indicates to you how closely overhead the sun really was. On a station,

the general pattern is that we have schools. Of course the church comes first, that's the primary purpose of our being there. It is in the center and whatever else we do is an arm of the church, it is a part of the church itself. So, we always have the church.

There is always a primary school and at Wembo Nyama, we had a primary school and we had a teacher training school. We had a Bible school and a hospital with a school for training assistant nurses. The evangelistic program and the educational program, which was in the Wembo Nyama district, was located in Wembo Nyama at the Wembo Nyama Station. The one at Lodja had been located at Lodja for about twenty years before I left and, in general, it is the same, except they don't have a hospital. They do have a dispensary. In addition, we also have a printing press at Lodja where we print our Sunday School lessons and other materials for our schools and churches throughout the conference.

We also have boarding departments because we have boys and girls who cannot stay at home and we think it's better for them to stay on the station so that they will be free to study. A program is worked out so that they have ample time to study for all types of work. They are under constant supervision of the leaders of the school and of the boarding department. So, on all of our stations we do have a boarding department both for boys and girls. Where there is a Bible school, we have an organization which takes care of the Bible school students and their families. Some of them are single and they would live in the dormitories. Some of them are married and we have little cottages in which they live. That is true of Lodja where our Bible school is now located.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many professional staff members did you have at your station?

Lorena Kelly:

At Lodja we had about eighteen in our high school when I left. I mentioned the primary school at Wembo Nyama, but of course, a number of years have passed and our school has developed into the high school stage, so we had about eighteen members on the staff of the two high schools--the junior high school and the senior high school. We had perhaps two or three in the Bible school, but many members of the staff of the high school also taught in the Bible school. We probably had six or eight working in the print shop, and probably twenty-five or thirty in the rural schools, maybe more.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are these white professionals?

Lorena Kelly:

All of the rural school work is manned by the African people.

Donald R. Lennon:

By the natives?

Lorena Kelly:

Yes, even the supervisor, the inspector, and the state inspector are Africans. In the beginning it was manned by missionaries, but now, in general, all of the administrative work of the church, the schools, and all the work that we are doing out there is under the supervision of the African leadership. Our Bishop is African. All of our district superintendents are African. All of our ministers are African. All of the directors of high schools with only one exception are African people. So we have very few missionaries in comparison to many years ago. But we have many more African leaders in comparison with many years ago and that is the direction in which we want to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are any of these your former students?

Lorena Kelly:

Oh yes, quite a few of them are. I had an interesting experience in Kinshasa a short time before I came home. I was there on Sunday and went to church. I sat down in church by a young man who had come in later. He was a very fine looking young man

who was immaculately dressed with a very gallant manner. I shared the songbook with him throughout the service and I was very impressed with him. After the service we introduced ourselves. He introduced himself to me as one of my former students. Well, I was embarrassed because I couldn't remember him. I suppose I've taught thousands of Congolese and can't always recognize them especially when they're about a thousand miles away from the classroom. He could see that I was embarrassed and in order to convince me that he was one of my students he simply took his Bible he had in his hand and opened it up and showed me my own handwriting on the flyleaf. Since the time I had given him that Bible, he had gone to France and graduated from the University in law and was at the time engaged in the Ministry of the Interior of the Congo government. That gives you an idea of what happens to some of our students. In fact, the first Prime Minister was one of our students.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, by and large most of your officials and your professional people in not only the Congo, but elsewhere in Africa, received much of their training originally in the missionary schools, did they not?

Lorena Kelly:

Yes, that's very true. One of our missionaries who is now working in this country is head of the Specials Department of Southeastern Jurisdiction Conference. Billy Starnes said that every head of state south of the Sahara Desert was a product of the church. That means that missionaries have gone into that continent many years ago and have opened up schools and trained people and today these students have become leaders of their nation in the government, in schools, in business, and every phase of their lives. In our own country of Zaire, formerly the Congo, for many years up until a very short time before independence, the only schools throughout the whole nation were schools

owned and maintained by the church; either the Protestant or Catholic church. Today if you were to ask any leader from the President right on down about his church affiliation, almost without exception, each one would respond by saying I am a Protestant or I am a Catholic; a member of the church. I'd like to add that some have deviated from what they have been taught, but they still are members of the church, they love the church, they respect the Christian religion, they want their children to be trained in Christian teaching. In fact, this new Congo government, which is made up exclusively of Congolese-Zairians, requires that we teach religion every day of the week in the primary schools and twice a week in the high schools. I think that is very indicative of their appreciation for the Christian training they've had and their desire for their children to have a Christian education.

Donald R. Lennon:

You indicated earlier that you were in Belgium for a while studying French before going to the Congo and that French was the official language in the Congo. What of the native dialects?

Lorena Kelly:

In the Congo there are about two hundred dialects and one of those dialects is Otetela, the language that I learned, which I used in all of my work when I first got out there. I continued to use it until I left with village people and primary school children. It was the language which is used in all church services and every contact except in the high school. French was a vehicular language of all the teaching that I did I high school. I used French in all classes except one class, English, which I conducted in English, of course. In a country where there are two hundred languages, it was impossible to think of developing high school and universities in two hundred languages. Since the Belgian people had introduced the French language and had been all over the nation, it was

scattered throughout the nation and people were speaking it everywhere. Therefore, it was accepted as the national language and still is. Even though it's a foreign language, it continues to be the official language of the Congo.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the transitions that took place in Africa during your long stay there?

Lorena Kelly:

I saw a great deal. When our missionaries first got there in 1914 there was no written language and they had to hear the language and figure out a written form from what they heard. Just to let you see what they heard at that time, I'll say John 3:16 for you in Otetela language: [Speaks in the Otetela language]. Well, that's what they listened to and as they listened to it and with whatever help they got, if they had any, they had to pick out the words and work out the grammar and write it down.

Donald R. Lennon:

But there was no written form?

Lorena Kelly:

No written form whatsoever. They had no schools of our kind. They had their schools. They had their form of education. They were intelligent people and they were living according to what wisdom they had. As they became a part of the world and a nation of relationships, it became necessary to also get acquainted with the world and with the word of God. The missionaries opened schools and had to write their textbooks and print their textbooks and so there was a great transformation from a verbal language to a written language. That's one of the main changes because springing from that has come all these others.

If they had not been educated to the degree to which they were--and they weren't highly educated, we had only twelve college graduates at independence time--but they had a lot of general education and experience. From this beginning came all of these other developments. For instance, they now have a Bible in our Otetela language. They

have the Bible in their own language, both the New and Old Testament. They were finishing the New Testament just when I got there in 1936 and two or three years ago they finished the Old Testament which has recently been published. So that is one transformation. They have the word of God where they can read it in their own language and interpret it from their own hearts and minds as God speaks to them. Whereas in the very beginning days, they had to listen to a missionary read it; it wasn't even written down. That's one thing that makes it possible for them to be the leaders of their church today--the very fact that there is a Bible in their own Otetela language.

Another change was the leadership of the church, which has been transformed almost entirely now from the hands of the missionaries into the hands of the African people. As I have indicated, we have only one missionary who is a director. Let's see, it is actually two that I know of, who are directors of high schools. All the rest of the educational work is in the hands of the African people. All of the evangelistic work is in the hands of the African people. Even our bishop who is the very top leader of this church of one hundred thousand members in Zaire is an African.

The women themselves are taking leadership. They are members of their local organizations and they are officers in the conference-wide organization. The African women are conducting schools for women on stations and out in villages. Even the women--who, at the time we went there were considered very inferior and incapable of learning anything from a book--now stand up before a class and teach boys and girls. In high school, girls often carry off the honors. That's another transformation from the educational work, the evangelistic work, and the Bible, the uplift of women. That probably is one of the greatest changes, because the women now have self respect. The

men have respect for them and the men even do what they can to push the women and the girls forward.

The junior high school for girls, which I organized and directed the last years I was there, was a conference-wide school which had to be voted by the conference. At the time, nearly all of the conference members were men. It is a dramatic illustration of how the attitude of men toward women has changed. In the beginning they kept them down. They weren't considered intelligent enough to learn anything from books and here they were voting in a school exclusively for girls.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are women yet involved in politics in any way?

Lorena Kelly:

In some instances, yes. The Minister of Family Life and Social Affairs in Zaire, when I left, was a woman. There are a number of mayors in the nation. The big metropolitan city of Kinshasa is divided up into what they call, “communes.” I suppose we'd call them zones, I don't know. In a city of two million people they have to have some kind of sectional division, I suppose, and many of those mayors were women. In 1968, I went up to Kisongani to attend a meeting of the Congo Protestant Council and we were welcomed by the mayor, a woman. So in government work, the women are taking leadership. The 24th Assembly of the United Nations had as its president, Mrs. Angie Brooks, from Liberia, Africa. You see, they're coming even into international organizations. That's a tremendous reformation, I suppose you'd call it, or transformation.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the cities, when you first arrived, great metropolitan centers as they are today or is this a burgeoning of recent years?

Lorena Kelly:

The cities were not nearly as large. In 1960 when we gained our independence, our largest city was Leopoldville then, now called Kinshasa. It had a population of about three hundred and fifty thousand. Now they say the population is about two million. So you see, in a little over a decade, how the population has grown. It has grown in other cities as well. The people found out that in the cities is where the action takes place and where the bright lights are, and where they can hopefully have a better life by earning a better salary, and being able to have electricity, and some of the other conveniences of life. They naturally flock to the cities just like people in this country do.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is Africa becoming industrialized?

Lorena Kelly:

It is to a certain extent. Ninety percent of Africa is still rural but when you see these big cities like Kinshasa and Johannesburg with a population of a million people, . . . and beautiful Nairobi, I don't know exactly what its population is, but it's one of the prettiest cities in Africa. There is some industry, of course, the mines are the big things. Some of the richest copper mines in the world are located in Zambia and the Congo. Ninety-six percent of the diamonds of the world come from Africa. Sixty-five percent of the gold comes from Africa. You see the mining is one of the main things.

Donald R. Lennon:

What does the rural population do for a living? Is it farming?

Lorena Kelly:

Yes, farming. It's very primitive farming. In our area they had no horses, no oxen, no trucks, absolutely nothing but a hoe. The women would take that hoe and dig into the earth and plant their grain and then when the grain was harvested they'd go back--like with rice in our country--and break the heads off with a little knife and put it in a basket that they carried on their backs on or their heads. Then they would carry it to the village. So it's very, very primitive. Now, in some areas where western influence has

come in and where Europeans have introduced modern farming, they do have machinery. But in the rural area in which I lived there was absolutely nothing, not even a wheelbarrow to carry their produce from the fields to the home.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you in Africa at the time of the turmoil of the early 60's?

Lorena Kelly:

Yes. It was June 30, 1960, that they gained their independence. We had a great celebration. Missionaries in Africa together had a big feast and a happy time together and that was typical of what happened throughout the whole nation. We were all so pleased that such a tremendous celebration could take place with such calmness and with such dignity and we were rejoicing over that. However, about eight days later, the whole situation changed. It was about time for our annual conference and we were preparing to go over to Katako Kombe, another station on which this annual conference was to be held. It was about one o'clock on Saturday, before I was to leave on Monday, that I was listening to the radio and I got a station from Elisabethville, as it was then called, now Lubumbashi. I heard in English--on a station that I had never heard before--a voice boom out saying, “This is the British Consul Ambassador. Will all the British subjects go to [a certain place] to evacuate?” And then the Voice of America came on, or vice versa--I don't remember the order in which they came--giving advice to American citizens. That was about twelve hundred or fifteen hundred miles away. While we had missionaries down there, it wasn't an immediate concern right where I was. I was very concerned for them, but it didn't affect what we were doing there at that moment, but before twenty-four hours had passed we were affected.

We were beginning to have to make decisions, too. We had heard how the trouble had started out in various parts of the Congo and that it was coming closer and closer to

us. By that time, I suppose we had heard it was within three hundred miles of where we were, so it was coming very fast. We were discussing it among ourselves on the station of Lodja and we were also discussing it with people on other stations by way of radio transmitter. What shall we do? Shall we go or shall we not go? No decision was made then, but we did go on to Katako Kombe to the conference. I remember somebody said over the radio, “Be sure to bring your sheepskins and some winter clothing, because if we have to evacuate, you'll need those things.” So I took those with me on Monday when I went to Katako Kombe. All the other missionaries came and all of the delegates--the African delegates. We were all there together on the Katako Kombe Station to have our annual conference.

We were very interested in what was developing throughout the nation, because it concerned us so vitally at that moment. We were listening to the radio and it was pouring down rain on the outside. The clouds were black, but these political clouds were even darker. We didn't get any encouraging reports at all. That night we met in the church with the leaders of the conference, and the African leaders and delegates, and discussed at length the question of whether we should leave or not. After much consultation it was decided that we should leave. One of the radio operators, a missionary, got in touch again with Salisbury and the American Embassy people or the consul and made plans for the planes to come up to get us.

That night, some of the missionaries and the African leaders of the church met and we turned over to them practically all of the funds that the Board of Missions had sent out to us for work in the conference and also the responsibility--the leadership--of the conference. Well, they were ready for it. They had mixed emotions, of course.

However, it wasn't a sudden thing for them, because all during these years they had been given responsibility all along and they had been participating in the executive committee and the conferences and they knew the organization and they knew the programs. So while it was a goal towards which we had worked, we had not expected to reach it so dramatically and so suddenly, but it happened that way. We knew that God was with them and that the church work would continue. The next morning while we were waiting for the U.S. Army and Navy planes to come pick us up to take us out, one of the missionaries said to me, “You know, in these short hours our church has grown twenty years.” I think that's true, because we had seen how they accepted the leadership of the church and have continued with it.

We got into the planes and went on, and there were two more of the planes on just a dirt landing field out there on the plains of Katako Kombe. They took us down to Kamina which was a base still maintained and owned by the Belgians. There they kept us and finally brought in a Globemaster. When everybody who was supposed to go on the Globemaster arrived, we left. It was about nine o'clock at night. This Globemaster was a tremendous thing. I'd never seen one before and I haven't seen one since. It just opens up like the mouth of an alligator. You can drive trucks or automobiles in there, anything you want, so we went in and drove. I guess it was kind of like going into an ark, Noah's ark. We didn't take any trucks with us, but we did fill it up with people. I remember when we started off--I was accustomed to riding only in a two motor plane--it seemed to me we'd never get off of the ground into the air. We kept going and going and going. Finally, we were airborne and went on down to Salisbury.

In Salisbury, we were met by people who knew we were coming, the Rhodesian people. They had committees appointed and they met us at the airport in buses and took us right into a soup kitchen and served us sandwiches and soup. It was cold down there in the winter time and we'd come from tropical Africa. I don't know why, but they took us to another kitchen and served us another meal. I guess the first one was supposed to be the midnight supper and the next one breakfast maybe. They even had clothes that they had gathered up from people and they said, “Now just go right in there and pick up anything you need. Just look all through there and any kind of clothes you need, you get.” They, too, knew we were coming from tropical Africa and that we would not be accustomed to that cold weather and perhaps, wouldn't have any warm clothing.

The next morning our own mission people came and picked us up and we went to some of their stations. Some of the missionaries whose furloughs were already due, went home, and some of us did other things. One of my colleagues and I wrote books and another one supervised the illustration of them. As we wrote them, different ones did different things. I went back to Lodja in 1961. We stayed there a month and everybody had to leave again. I didn't get back until 1965 and then I stayed until 1969.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any actual hostilities in the Central Congo area where you were?

Lorena Kelly:

There were some. There was hostility between sections of our own tribe. In the Lodja area, in the beginning of the development of our work, the African leaders came from Wembo Nyama, because they were trained down there and there was a great revival meeting. That revival meeting stimulated mission-type work and these leaders then went up into the north section, which was in the Lodja section. They were considered foreigners to the local people. They called them “the people of the land.” “Osambala”

was the word they used. When the country got it's independence there was jealousy for fear that some of the outsiders would get the top leadership, you know. They had a war between them. I've forgotten how many people were killed, maybe eighty or two hundred, I've forgotten exactly, but quite a few. Most of them had to leave their homes and go out into the forest and stay out there for a long time. They had a hard, hard time. They lost everything they had and had a hard time coming back. There was strife there and then we found some bitterness when we came back in December of 1960 hoping to stay. That's when we were able to stay on there for about a month.

We went back to Lodja on the 23rd of December and we went to Usumbura having come from Zambia. At Usumbura there were a large number of people from Lodja and they had to put on an extra plane. Well, there were a dozen of us, I suppose, and instead of putting us on a plane that stopped along the way as it came down--it was about a two or three hour flight--they put us on a special plane. When we got to Lodja, the plane stopped and we got out and went on to the mission. The people were there to meet us. In the meantime, the second plane which had stopped along the way, came in. This upset the people. It was a time when everything was very, very tense. The United Nations was in there and there were so many people. The Communist rebels had come in and the local people, who were uninformed, didn't know who were their friends and who were not their friends. Anything that came in that was unusual frightened them very much. When the second plane came in, they were indeed disturbed. The authority to come in was supposed to have been given through Luluabourg, which is three hundred miles away, but the message did not get to Lodja and they did not know that the second

plane was to come. They sent for the security forces in town and they came out there and were very upset.

We had hardly gotten to the mission and had even gotten our baggage out when a car of soldiers drove up and told us to get right back in the car and get our baggage. They were to take everybody back out there who came on the plane. They lined us up in the airport. I believe that was before we went home and called the roll. I guess it was the chief of police who called the roll. When he got to me he smiled and he said, “You are my former teacher.” That was a very welcome smile. Then they said, “Now you can go back to the mission.” Right down about a hundred yards where we had to turn to go towards the mission was a man with a submachine gun in his hand just pointing it right towards us. I said, “Would you please tell that man that we have permission to go?” So we got home all right, but when we did get there, they came for us again. We went back out there and had to wait to be inspected. They wanted to inspect all of our baggage.

What had caused all of this trouble was that one of the soldiers who was on guard recognized among the passengers, one of his former mates in the army. He was not out and he knew that person was not out, but he was not in uniform, so he knew something was wrong. He was the one who alerted the security forces. They arrested him and I think the woman that was with him, maybe, and they did find a gun and ammunition in his suitcase. That really made them afraid. They arrested the pilot and took him into town and put him under house arrest and I was told later by a member of our church who was the chief of police or assistant police--I think it was chief of police--that twice they started to take him out to the military camp to kill him and each time he wouldn't let them do it. He'd take him back.

They finally got to us and investigated our baggage and let us go back. Then when we got back to the mission they came and got our radio transmitter. This transmitter was what we used to talk with other missionaries and other stations, you know. It was what we used to help us to get out that time by talking down to Rhodesia. We considered it one of the means of security, but they came and took it from us.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were somewhat isolated without it?

Lorena Kelly:

That's right. We were isolated without it. On the second plane, some of the new missionaries came and went down to Wembo Nyama that same day, I believe. By that time, the board was so concerned that they provided a plane for our evacuation and that same day the plane arrived at Wembo Nyama. However, they took the plane, they grounded it. They wouldn't let us use it. So that form of security was take out of our hands. We had expected the next day to go over to Katako Kombe again for Christmas. It was Christmas Eve. We finally got ready and started over there and we got about half way, going through the forest, and some of the men of the forest came out with their jungle knives--"machets," we called them--in their hands and tried to stop us. Well, they didn't stop us, but we went a little farther and some of the officials did stop us and wouldn't let us go on. They made us turn around and go back to a village that was close by to have our baggage inspected and when they came, they took our car keys. So every form of security was taken away from us. The plane was grounded, the transmitter was gone and now they had taken our car keys. So the one main security was God. Of course, He was the security we had. Well, they talked for a while and one man said, “What do you mean? You missionaries come out here to bring us the word of God, the Bible, and here you come out here to bring guns to shoot us.” They had gotten a message that the

missionaries had come on that plane to kill everybody, because of that gun they found in that man's suitcase. That day was the day that the school children were going home and they went all over the country, as they went home, telling everybody that the missionaries had come back to shoot them all, to kill them all. That was a very tense time. We did have to go back. We didn't get to go to Katako Kombe; we had to go back and spend Christmas at Lodja.

Finally, one of our ministers went out to the biggest villages there and explained to them what the situation was and little by little the tenseness eased up a bit and about a week later we started back to Katako Kombe. We got back to that same place and these people came out with their jungle knives again. This time a security officer, one of our church members, with some soldiers led us. He got in a jeep and went in front of us. I believe I was next. We had two cars. I was driving one and Mr. Reid was driving one, Mr. and Mrs. Reid. Then behind us was Mr. Shungu who is now our Bishop. He wasn't then; he was a minister then. His car was filled with soldiers. So we got to that same place and the security people got by. When we came by they tried to stop us but we didn't stop. When Mr. Shungu's car came, the soldiers jumped out and tried to grab the men and they ran into the forest. We went on to tell the security people what had happened back there and they went back, of course, to see about it. They tried their best to get them out of the forest and finally they said, “If you don't come out of the forest, we're gonna take your mothers to jail.” Well, that's something they usually can't stand. They can't stand for you to mistreat their mothers. So all of them came out I think, but one or two, and they, of course, arrested them and put them in jail or maybe took them to Katako Kombe, I don't remember which. Anyway, they arrested them and held them in

custody. We continued our journey and it must have been into another district of the province. When we got to the border, this security man went back. I guess he thought he was out of his territory and he thought we were safe or he wouldn't have let us loose there, I'm sure. So he went back and we went on and Mr. Reid, who had worked in that area years and years, thought from now on 'I'll find friendly people,' but he didn't. All along the way, everybody that we met had that antagonistic attitude toward us.

We went on to Katako Kombe and spent the night. The next day I was going on to Wembo Nyama with one of the daughters of one of our missionaries. We were going with Mr. Shangu in his car. We were to meet him up in the administrator's office and when we got to the office there was the administrator at his desk and here were these soldiers over here with their guns and here were these missionaries wanting to go on to Wembo Nyama. The soldiers say, “No, we want you to take us back to Lodja.” They had been ordered to wait there for somebody to take them back--somebody else, not us. But no, they wanted to go back. I felt sorry for that administrator. He was a young man and, of course, all this was new to all of them and it was easy to tell where the power was. It was in that gun. He dared not disobey or do anything contrary to their wishes. But again, the Lord came to our rescue. A truck drove up on the outside--a commercial truck--and somebody went out and asked if they could take the soldiers and they said yes. So, that solved the problem.

We went on to Wembo Nyama. On the way down, we stopped at one of our biggest churches and we found that even down there, the message had gotten out that the missionaries had come back to kill everybody. The pastor told us that some of the people had even withdrawn from the church. Well, of course, we had an opportunity to explain

to them what it was all about. Little by little the tension was released a little bit. We went on to Wembo Nyama and I was down there just about a month and went back to Lodja and a week later we were on our way out again. It had just gotten worse all the time.

We left January 23, just exactly a month from the day we came in. I was in Zambia for about a year working on these textbooks. Then I was in Kinshasa for a couple of years doing another type of mission work. My furlough was due in 1963 and I came home. In the meantime, I had been told that I was appointed to this junior high school for girls. I was to organize it and direct it. One missionary said, “If you want anything when you get out here, bring it, because it's not here.” I'd gotten a lot of school supplies and my own things. I had about thirty-five different cases, trunks and so on, and they shipped them. I had nothing but my suitcase and was ready to go about forty-eight hours from then. The word came then on Sunday afternoon; I was to leave on Tuesday morning I believe. On Sunday afternoon some friends came by and said, “Have you seen the Charlotte Observer?” I said, “No.” They had and they told me about the death of Burleigh Law, one of our pilots. Of course, I knew that was at Wembo Nyama and that was something very serious. So Monday morning I had a telephone call from the board saying that I couldn't go back. I stayed a month longer and finally they sent me to Mulingwishi and I taught high school there for a year. In 1965 I got back to Lodja.

While I was down at Mulingwishi they had one of the biggest conferences they've had. They had representatives of the U.S. there, and just a week after they had gone the Communist rebels came in from the Stanleyville area and took over. Five of our couples were still there. Eventually they were persuaded to let their women and children leave.

They kept the men there for two months, I guess. They just told them everything they must do and where they must go and they had a guard with them all the time, in the classroom and everywhere else. From time to time they would get them out and tell them they were going to kill them. One time they had a man, one of our missionaries, up against the wall ready to be shot. And every time they would release them. They didn't know why. Of course, they had their ideas. They thought maybe they were trying to pressure them into giving them more money, because from time to time they would come and ask for money.

Of course, the hospital was there. Among the staff was a doctor and his wife-- well, his wife had gone. There were two doctors, Dr. Hughlett and Dr. Sheffy (?), there. I guess the other three were educational workers. They were interested of course in having the doctors there and having medical care for their soldiers and for other people. That was when Burleigh Law came down there. That was before the women left, I believe. Yes, the women were still there. Burleigh came down from Lodja in a mission plane and he knew they were there and thought maybe they needed some help. The missionaries didn't want him to land, but he said he could not go away and leave them down there in that situation. So he landed and a short time afterwards they shot him. He died within a few hours and was buried. In the meantime the missionaries got out. They had a rough time doing it, but I think they have recovered. That must have been an awful experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm sure it was. I know you were glad you were away.

Lorena Kelly:

Yes, I wouldn't like to have that kind of experience.

We do have medical work which is very well developed I think. We have three hospital buildings. Before independence we had three hospitals actually in operation. Two of the hospitals have been closed, but they maintain a dispensary in each of the buildings. At Wembo Nyama we have a hospital of about two hundred beds and we do maintain the hospital and schools for training boys and girls to be assistant nurses. We have a maternity ward where many, many children are born every year and cared for by the medical people who are there.

In 1969, our last missionary retired--Dr. Hughlett. Just at that time, very dramatically I think, one of our students who had just graduated from the medical school in France came back to take up his [medical career]. Since he had accepted a scholarship from the government, he was obligated to accept an appointment from the government. The government was kind enough to send him back to Wembo Nyama as a resident physician there. But as an employee of the government he had so much administrative work to do that he really wasn't able to give much medical attention to the hospital. Eventually, two doctors from Holland, a man and his wife, came and have been there at Wembo Nyama for some time. On each of our stations and in many of the out-villages, sixteen or eighteen of them I guess, we do have a dispensary and they have to be supervised, too. The only American missionary we have in medical work now in Zaire is a nurse, Dorothy Gilbert. She does most of the supervision of the dispensaries in the out-villages and the doctor and his wife have remained at Wembo Nyama. When this Congolese doctor was there, he, so far as I know, was the only doctor for the whole tribe of three hundred and fifty thousand people. You can see the medical work is in dire need of help. It still is.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was even worse when you arrived in the mid-thirties, was it not?

Lorena Kelly:

When I got there in the mid-1930's we had three doctors. We had a doctor at Wembo Nyama, Minga, and Tunda. Dr. Sheffy was at Wembo Nyama, Dr. Lewis at Tunda, and Dr. Hughlett at Minga. Dr. Lewis died, Dr. Hughlett has retired and Dr. Sheffy came back quite a number of years ago. He's living in Lynchburg now. Medical work is in dire need of help.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is that due to the lack of people who will go?

Lorena Kelly:

There are many things that are involved in it, I think. I don't know whether the board would agree with me or not, but I personally feel that it is basically a lack of interest on the part of the church as a whole to venture out into missionary work at the present time. Another thing, certain people have gotten a little bit disappointed in the way mission funds have been spent. Some of them feel that none of our funds should go through the National Council of Churches in Boston. They've lost some confidence in that, unfortunately. Some of our funds do go through that but for good purposes and with more returns I think than we could use by ourselves. Some of the things that have happened in this country have hurt. Unfortunately, a false rumor got around that the board was giving money to some other "subversive" people, the “Black Power” people. That was not true, but you know when you turn loose a bag of feathers you don't get them all back. This has hurt.

Also, the African people are developing leadership on their own. Some people take the attitude that they should be permitted to do a major part of it. The people in Zaire don't say that. In certain sections of Africa they can't get missionaries in now, but in Zaire you can. I said to Bishop Shungu when I saw him over at the World Methodist

Conference in Denver, Colorado, last year [1971], “Bishop Shungu, do you still need missionaries?” And he said, “If I had fifty I'd take them back with me. I've never needed missionaries as I do now.” So I feel that we who know the need and feel the need so keenly just need to do all we can to make other people realize that the people do need it. Now, when they're trying to develop their own leadership and get their own people educated where they can do their work, for us to say, “Well now, you just go right along and we'll stand back;” I don't think that's right and I don't think that's the way parents do it. As long that they want us, we have an obligation. Now, if they got to the place that they felt that they could do without us and they could carry on the work, that's a different thing. It's what we expect to happen eventually, but until they do feel that way about it, I think we have an obligation to remain faithful to them. That is my feeling.

[End of Interview]